Abstract

Gut microbes play an important role in regulating brain processes and influence behaviour, cognition and emotional states in humans and rodents. Nevertheless, it is not known how ingestion of beneficial microbes modulates emotional states in piglets and whether it can improve welfare. Here we use an attention bias task to assess the effects of Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC-PTA-6475 and Lactobacillus plantarum L1-6 supplementation early in life on emotional states in 33 piglets compared to 31 placebo supplemented piglets. We hypothesized that Lactobacillus supplementation would reduce vigilance behaviour (head at shoulder height or higher) and attention (head oriented towards the threat) in response to an auditory threat. The results showed that the control group increased vigilance behaviour in response to the threat, but there was no increase in the probiotics group. Despite the increased vigilance, the control group paid less attention to the threat. One explanation may be that control piglets avoided looking in the direction of the threat just because they perceived it as more threatening, but further research is necessary to confirm this. In conclusion, Lactobacillus supplementation may be a suitable tool to reduce anxiety, promote a more appropriate response to a challenge and so improve welfare.

Subject terms: Animal behaviour, Agroecology

Introduction

The intestine contains trillions of microbes that form an ecosystem commonly referred to as the gut microbiota1. A key feature of the gut microbiota is its bidirectional communication with the brain, also called the microbiota-gut-brain axis, through which it can influence fundamental brain processes2. The microbial colonization of the gut starts at birth, and the gut microbiota goes through major developmental changes during the first years of life (the first 5–12 years in humans3,4 and the first 2–6 months in pigs5,6), while the adult microbiota is relatively stable7. It is critical to establish a balanced and diverse gut microbiota early in life to guarantee the normal development of several homeostatic processes, including the immune system, the cardiovascular system, the digestive system and metabolic processes1. However, the early establishment of the gut microbiota is vulnerable to disturbances, such as a suboptimal diet and environment, use of antibiotics and excessive stress8.

The intestinal microbes present early in life play a role in normal brain development9,10. The main pathways of microbiota-gut-brain communication are through the central and enteric nervous systems11,12, the immune system13, the neuro-endocrine system14 and through the production of microbial metabolites15–17. Mice raised without a gut microbiota (germ-free) showed exaggerated corticosterone and ACTH responses to restraint stress compared to normal mice10. Germ-free mice also showed reduced anxiety-like behaviours and increased motor activity9,18. However, the reduced anxiety in germ-free mice could be normalized by restoring the gut microbiota post-weaning19. In humans, there is now substantial evidence that an unbalanced gut microbiota contributes to the development of a range of abnormal behaviours and can be a contributing factor to depression and anxiety disorders8,20,21.

The normal development of the gut microbiota may be compromised in animals raised in indoor environments under strict hygienic conditions, due to a lack of exposure to environmental microbes22,23. Furthermore, intensively reared animals, such as pigs, experience multiple stressors already from an early age (e.g., weaning and separation from the dam, castration, frequent mixing with unfamiliar animals). The combination of strict hygienic conditions, multiple early life stressors and use of antibiotics may pose an increased risk of developing an unbalanced gut microbiota in intensively reared animals8.

One way to promote a healthy gut development is to supplement the diet with probiotics, defined as live microorganisms that confer a health benefit on the host24. For example, supplementing with Lactobacillus strains or other beneficial microbes at weaning in piglets has been shown to prevent health problems associated with weaning25. In other animal species, several Lactobacillus strains are known to influence the behaviour of their host26. Lactobacillus plantarum supplementation has been shown to reduce anxiety- and depression-like behaviours in rodents27–29. Supplementation with Lactobacillus reuteri reduced stress-induced anxiety-like behaviours30 and restored disturbed social behaviour in mice with an unbalanced gut microbiota31. Meta-analyses also suggest that probiotic supplementation in humans can reduce subjective stress levels without altering cortisol levels32 and has antidepressant and anxiolytic effects33. One possible pathway by which Lactobacillus may influence the behaviour of its host is through the production of neurochemicals similar to those produced in vertebrate organisms34. L. reuteri and L. plantarum have been shown to modulate GABAergic and serotonergic signalling pathways in multiple brain regions28,29,35,36.

It is now widely accepted that the emotional state is a main component of animal welfare37. Rodent models and human studies have demonstrated the importance of supporting a normal development of the gut microbiota to promote both physical and mental health20, but research into the microbiota-gut-brain axis in other animal species is limited38. The pig gut microbiome shares more similarities with the human microbiome than does the mouse microbiome39, and therefore the pig is a suitable model to explore the gut-brain axis. In addition, it has already been shown that the emotional state of intensively reared animals is more negative compared to animals living in enriched environments40,41. Therefore, elucidating how gut microbes modulate emotional states in pigs may provide an easily applicable tool to improve the welfare of intensively reared animals, and this may also be relevant for human studies. Because both L. reuteri and L. plantarum have been shown to have a beneficial impact on behaviour27–29,31 and alter GABAergic and serotonergic signalling in rodent models28,29,35,36, they may be suitable to improve welfare in farmed animals.

Even though animals are not able to communicate their emotions verbally, there are cognitive approaches that can provide insight into animal emotions42. One relatively novel approach is to assess changes in attentional processes43. Attentional processes are required for the selection of relevant stimuli for further processing because the cognitive system cannot process all sensory stimuli at once44. The ability to direct attention efficiently towards situations that enhance or threaten survival provides an adaptive advantage, and this allocation of attentional resources is facilitated by the experience of different emotional states.

Threat signals pose a risk to the animal’s survival and are therefore attended to immediately and automatically, so taking priority over other signals45. This effect is further enhanced by negative emotional states: anxious people are quicker to detect a threat and will look at a threat for longer than non-anxious people, which is called an attention bias to threat46. Similar attention bias approaches have been developed for animals, in which general vigilance behaviour (i.e., head at shoulder height or higher) and attention directed towards the threat (i.e., the animal looking at the threat) are taken as the main measures of attention47,48. Sheep with pharmacologically-induced anxiety showed increased attention towards a dog (predator threat) and increased vigilance behaviour48. Stressed starlings were more vigilant after hearing a conspecific alarm call49. Pigs with a proactive coping style were more vigilant during a 10 s sudden motion and loud sound stimulus, but no differences in vigilance or attention were found once the threat ended50. However, human and primate studies have also shown that the relationship between threat and attention is not linear, and that an initial increased attention towards a threat may be followed by attentional avoidance51,52. Together, these studies suggest that attention bias to threat is a promising novel indicator of anxiety in animals43,52. Attention bias tasks also have some advantages over more commonly used methods to assess emotions in animals, such as judgement bias, because they require no training and have lower attrition rates43, which makes them more suitable for very young (pre-weaning) animals.

Given the critical role of gut microbes in modulating the emotional state and their potential to improve animal welfare, we aim to assess the effects of Lactobacillus supplementation early in life on attention bias as an indicator of the emotional state in pre-weaning piglets compared to a placebo control group. We did this by comparing the behavioural responses of individual, supplemented and non-supplemented piglets from the same litter, to a threatening auditory stimulus in a novel test arena. We hypothesize that the Lactobacillus supplementation would reduce an anxious emotional state, with supplemented pigs exhibiting reduced attention to a threat and reduced vigilance behaviour following a threat compared to the control group.

Results

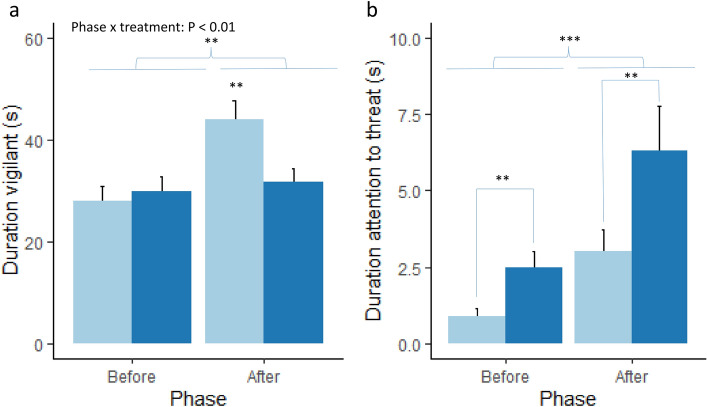

Vigilance behaviour and attention towards the threat

The duration spent vigilant was significantly affected by a phase x treatment interaction (F(1,109.02) = 8.67, p < 0.01, Fig. 1a), with the control piglets increasing the time spent vigilant after the threat while the probiotics supplemented piglets did not (post-hoc Tukey test, p < 0.01). Vigilance behaviour was also affected by a test order effect (F(9,109.28) = 3.6, p < 0.001), with the animals tested as number 6 in the litter being significantly less vigilant compared to animals tested first (p < 0.001) eight, (p < 0.05) and ninth (p < 0.05). Attention to the threat (Fig. 1b) was significantly affected by phase (Kruskal–Wallis χ2 = 12.26, p < 0.001) with attention towards the threat increasing after the threat. Attention to threat was also affected by treatment (χ2 = 7.31, p < 0.01), with the probiotic supplemented piglets paying more attention to the threat.

Figure 1.

Mean ± standard error of the mean (sem) duration of (a) vigilance behaviour and (b) attention towards the threat for the control (light blue bars) and probiotic supplemented (dark blue bars) piglets before and after the threat. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

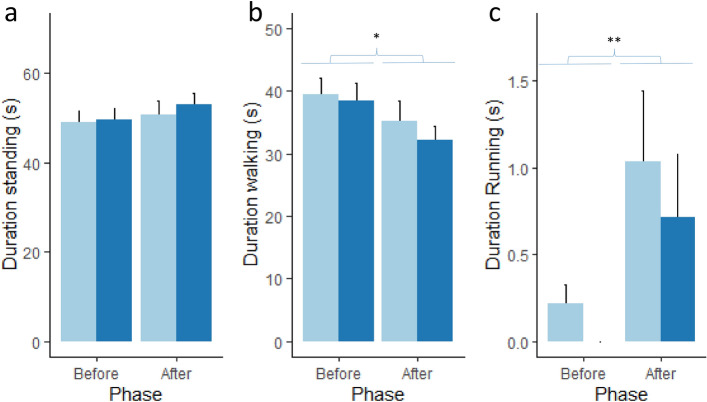

Activity and location

Piglet activity is shown in Fig. 2. Piglets walked (F1,115.97 = 5.6, p < 0.05, Fig. 2b) and ran (χ2 = 7.06 p < 0.01, Fig. 2c) significantly more often after the threat than before the threat. In addition, female piglets (0.93 ± 0.34 s) ran more than male piglets (0.20 ± 0.72 s, χ2 = 4.43, p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Mean ± sem duration of (a) standing behaviour, (b) walking behaviour and c. running behaviour for the control (light blue bars) and probiotic supplemented (dark blue bars) piglets before and after the threat. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

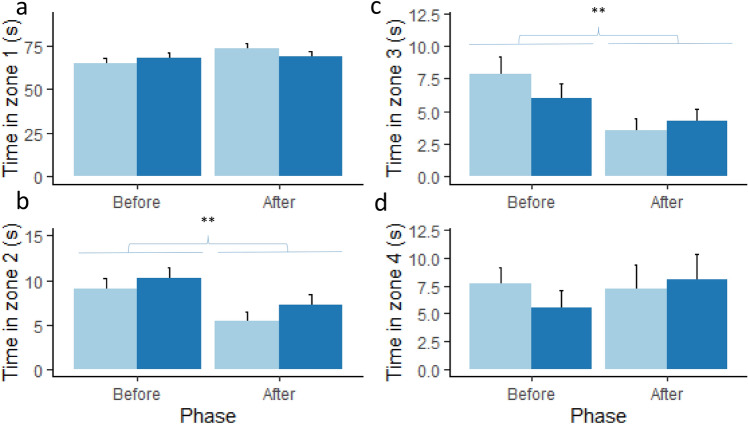

The time spent in the different zones was not affected by treatment (Fig. 3). Piglets reduced the time spent in zone 2 (χ2 = 10.04, p < 0.01, Fig. 3b) and 3 (χ2 = 8.24, p < 0.01, Fig. 3c) after the threat. In addition, male piglets (71.6 ± 2.0 s) spent more time in zone 1 than female piglets (64.8 ± 2.3 s, χ2 = 5.51, p < 0.05), there were no differences between the sexes for the other zones.

Figure 3.

Mean ± sem duration of time spent in (a) Zone 1 (area near conspecifics), (b) Zone 2 (middle area), (c) Zone 3 (middle area) and (d) zone 4 (area with substrate and toys) for the control (light blue bars) and probiotic supplemented (dark blue bars) piglets before and after the threat. **p < 0.01.

General behavioural indicators

Other behaviours were also assessed and the statistical parameters are presented in Table 1. There were neither phase nor treatment differences for interacting with the toys, time spent rooting, conspecific directed behaviours or the latency to first contact with the toys. Exploring significantly reduced after the threat (p < 0.001) and there was a near-significant tendency for a phase by treatment interaction (p = 0.05), with a larger reduction in exploring behaviours in the control piglets after the threat. Females tended to explore (27.9 ± 2 s) more than males (21.1 ± 1.6, F1,56.6 = 3.7, p = 0.06).

Table 1.

Mean ± sem behavioural variables during the two different phases of the attention bias test.

| Variable | Before | After | Treatment | Phase | Treatment × phase | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probiotics | Control | Probiotics | Control | Test value | p value | Test value | p value | Test value | p value | |

| Latency to first reach toys (s) | – | – | 100.5 ± 12.8 | 92.0 ± 13.0 | F = 0.108 | 0.74 | – | – | – | – |

| Time interacting with toys (s) | 3.3 ± 0.8 | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 4.3 ± 1.1 | 4.6 ± 1.4 | χ2 = 0.96 | 0.33 | χ2 = 0.40 | 0.52 | – | – |

| Time spent rooting (s) | 0.61 ± 0.5 | 0.45 ± 0.2 | 0.29 ± 0.22 | 0.55 ± 0.27 | χ2 = 0.62 | 0.43 | χ2 = 0.04 | 0.84 | – | – |

| Time spent exploring (s) | 28.4 ± 2.3 | 28.4 ± 2.3 | 23.5 ± 3.0 | 15.9 ± 2.1 | F = 1.65 | 0.2 | F = 25.66 | < 0.001 | F = 3.9 | 0.05 |

| Conspecific directed behaviours (s) | 24.3 ± 2.5 | 26.9 ± 2.5 | 25.9 ± 2.7 | 32.9 ± 3.4 | F = 1.9 | 0.17 | F = 2.0 | 0.15 | F = 0.67 | 0.41 |

Discussion

Our results provide the first evidence that Lactobacillus supplementation alters anxiety-like states in piglets. An increase in vigilance behaviour in response to an auditory threat was prevented by Lactobacillus, and this anxiolytic effect is in agreement with other studies in rodents and humans20,26. Lactobacillus administered early in life may therefore be a suitable tool to improve the welfare of intensively farmed pigs. It is already common to supplement with Lactobacillus or other beneficial microbes around weaning to prevent health problems and increase production in pigs25, but our results suggest that there may be a benefit beyond production and health. However, we only assessed attention bias once at 4 weeks of age (pre-weaning) and further studies are necessary to determine any long-term effects.

According to our hypothesis, Lactobacillus supplementation prevented an increase in vigilance behaviour following a threat. The Lactobacillus and control groups displayed similar levels of vigilance behaviour before the threat, suggesting that the increase in vigilance behaviour in the control group was a direct response to the threat, rather than a more general response. We also detected a test order effect on vigilance behaviour, with animals tested as number six being significantly less vigilant than animals tested first or as number eight or nine in the litter. The reason for this is not clear, and this test order effect was not detected for any other variable. We may speculate that it may be due to the stronger reaction of the conspecifics to the first threat sound, which may have influenced the first test piglet. However, this does not explain the higher vigilance behaviour in pigs tested at number eight and nine in the litter when the conspecifics should have been habituated to the sound. Nevertheless, we had distributed the supplemented and control piglets evenly throughout the testing day, and the treatment of the piglet tested first in the litter was as balanced as possible across the litters. Therefore, despite the test order effect, we could still detect a significant phase by treatment interaction on vigilance behaviour.

Although attention towards the threat was relatively low (less than 10 s compared to around 40 s48–70 s47 in previous studies in sheep), it increased after the threat in both groups as predicted. However, the lower attention towards the threat in the control group was not according to our prediction and seems counter-intuitive given the increased vigilance behaviour. Paying attention to a threat is adaptive and allows the animal to respond to the threat appropriately45. However, attention away from threat stimuli in anxious individuals has also been reported in other studies53. Monkeys that had undergone a stressful procedure were more likely to redirect their gaze away from an aggressive monkey face, suggesting a disengagement of attention to threat in stressed animals52. Anxious humans also showed attentional avoidance of threatening pictures54,55. Therefore, our results may fit the vigilance-avoidance model of attention that has been described in humans53,56. This vigilance-avoidance model postulates that anxious people show an increased initial orienting towards a threat, followed by attentional avoidance of it. The attentional avoidance of threatening information may be a way to self-regulate the emotional state57 and may play a role in maintaining fear, because it does not allow for habituation to threat stimuli55,58. Therefore, a possible explanation for our results could be that the control pigs avoided looking at the threat because they perceived it as more threatening than the supplemented pigs, and consequently did not see there was no actual threat present. They then increased their general vigilance behaviour to be able to respond to a potential threat.

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to investigate the impact of gut-brain axis modification on emotional states in pigs. The pig gut microbiome shares more similarities with the human microbiome than does the mouse microbiome39, and therefore the pig is a suitable model to investigate the gut-brain axis. Our results showed that Lactobacillus supplementation reduced attention bias towards threat, and future research exploring the therapeutic value of Lactobacillus supplementation on reducing anxiety in humans may therefore be warranted.

The Lactobacillus supplemented piglets paid more attention to the threat, and this difference already existed before the threat. It is likely that the piglets were paying attention to the observer standing quietly next to the arena (and next to the computer that played-back the threat sound) in the period before the threat. In future studies it would be better if the threat sound came from a different location than the observer, so that attention to the threat and to the observer can be determined independently. Alternatively, the Lactobacillus group may have been more attentive to their surroundings in general, but this would need further investigation.

Accurate measures of attention are difficult to record in freely moving animals. We used the direction of the head as a measure of what the animals were looking at—as an indirect indication of attention to threat—but it is likely that we have missed more subtle changes in attention. In humans, eye tracking is commonly used to demonstrate precisely how fast, where and for how long attention is focused59, but such technologies have not yet been developed for pigs and would also require some level of restraint. However, what a person is looking at is in most cases also the main focus of attention44, and therefore looking towards the threat should have been a reasonable proxy for attention towards the threat. Pigs do not only rely on vision to navigate their environment60, and auditory and olfactory cues61 are also important. Other more subtle measures of attention, such as automated measurement of the orientation of the ears, could potentially also be used in addition to the head orientation in future studies.

The threat used in this study was a recording of an aggressive dog bark that was most likely unfamiliar to the piglets, because piglets were raised indoors and had never seen a dog. Although we cannot rule out that they may have heard dogs barking outside. Wolves are a natural predator of wild boar, and mostly predate on their piglets62, so we reasoned that an aggressive dog bark may trigger a fear response in piglets separated from their mother. However, the novelty of the sound may also have contributed to the observed fear responses. We included a pre-threat and a post-threat period in the attention bias task, in order to separate more general ‘baseline’ behaviours from behavioural responses to a threat, which was an improvement from previously used tasks47,50,63. We observed several changes in behaviour between the two different phases. Piglets ran more after the threat, and because increased activity can be interpreted as a sign of fear64, this suggests that our threat stimulus indeed induced fear. Females ran more than males across both phases, suggesting that females were either more fearful in general or more active.

Piglets spent less time in the middle of the arena after the threat, potentially because being further away from the conspecifics elicited more fear65. However, we did not observe any effect of the Lactobacillus on the time spent in the area closest to the conspecifics nor on conspecific directed behaviours between the phases. Males spent more time close to the conspecific than females. The reason for this is not clear, but it could be that males were more fearful, which is in contradiction with the lower activity in males (see above). Alternatively, they could have had had a stronger social motivation than females, although we did not observe any sex differences in conspecific directed behaviours. The piglets spent very little time rooting in the straw area or interacting with the toys and we did not see a difference between the phases. Both the arena and the toys were unfamiliar to the piglets and the toys were on the opposite side from the conspecifics, and piglets may have been too fearful to interact with the substrate and toys. General exploration behaviours (exploration not directed to the substrate or toys) decreased after the threat, especially in the control group. Exploration is a normal and natural behaviour for pigs, and free-range pigs spent a large proportion of their time exploring, rooting and foraging66. The larger decrease in exploration behaviour in the control group can probably be explained by their increased vigilance behaviour, and may be indicative of increased fear or anxiety. Females also tended to explore more than males. Previous studies have also shown that 4-week old female piglets spent more time exploring a novel object than males, which the authors suggested was due to faster brain development in females at this age67. Other individual factors such as personality traits and state anxiety can also influence fear responses68, and it would be interesting to investigate such individual traits on attention bias to threat in future studies.

Within each litter, five piglets were assigned to receive the Lactobacillus supplementation and five other piglets received a control treatment. In this way, we could control at least some of the effects attributable to the sow and pen environments, and made it easier for the experimenters to be blind to the treatments. However, this is also means that there could have been some cross-contamination of the Lactobacillus strains from the supplemented to the control piglets, that may have diminished some of the differences between the treatments.

In conclusion, this study provides the first evidence that Lactobacillus supplementation early in life prevents an increase in vigilance behaviour following a threat in pre-weaning piglets. The control group increased vigilance behaviours in response to the threat but nevertheless reduced orienting in the direction of the threat. One explanation may be that the control piglets avoided looking in the direction of the threat just because they perceived it as more threatening, but further research would be necessary to confirm this. This study provides a good base for further development of Lactobacillus supplementation as a tool to promote a more appropriate response to a challenge and improve animal welfare in intensively reared animals.

Methods

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The study was approved by the Uppsala animal ethics committee (document numbers C105416/16 and 5.8.18/01998/2018) and complied with the ARRIVE guidelines69.

Animals and housing

In total, 64 piglets participated in the experiment. The study was conducted at the experimental facilities of the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (Lövsta) that houses specific pathogen free sows. Sows were moved to the farrowing unit 1 week before expected farrowing and stayed with their piglets until weaning at 35 days of age. The farrowing pens’ design and size complied with the European animal welfare legislation (Council Directive 2008/120/EC)70. The farrowing pens (3.35 × 2.0 m) consisted of a concrete floor lying and feeding area (2.1 m × 2. 0 m), a slatted dung area (1.25 m × 2.0 m), as well as a heated corner that was only accessible to the piglets. Sows were given 15–20 kg of chopped straw two days prior to the expected farrowing date. An additional small amount of straw (0.5–1 kg/day) was given daily as enrichment after the pens were manually cleaned. Sows were fed a standard commercial dry feed for lactating sows by an automatic feeding system (Table 1). The first 10 days, sows were fed twice per day and after that three times a day until weaning. An ad libitum creep feed dispenser was accessible to the piglets from two weeks of age and contained a standard piglet creep feed (Table 2). Water was available ad libitum from two drinking nipples. Piglets were weighed (birth weight for control piglet 1.71 ± 0.07 kg and supplemented 1.67 ± 0.08 kg) and ear-tattooed with an individual number within 1 day after birth, and received an ear-tag with their individual number at 5 days of age. A 1 mL intramuscular injection of an iron supplement (Uniferon, 200 mg/mL) was given at 5 days and two weeks of age.

Table 2.

Dietary content for sows and piglets.

| Dietary content | Amount | |

|---|---|---|

| Sow | Piglets | |

| Energy (MJ/kg) | 13 | 14.4 |

| NE, MJ | 9.9 | 10.8 |

| Water % | 12.3 | 11.1 |

| Protein (g/kg) | 166 | 285 |

| Fat (g/kg) | 58 | 105 |

| Crude fiber (g/kg) | 49 | 25 |

| Ash (g/kg) | 50 | 85 |

| Sodium (g/kg) | 2 | 3 |

| Potassium (g/kg) | 9 | 17 |

| Lysine (g/kg) | 8 | 17 |

| Metione (g/kg) | 3 | 6 |

| Vitamin A (IE/kg) | 8000 | 16,000 |

| Vitamin D3 (IE/kg) | 1600 | 3320 |

| Vitamin E (IE/kg) | 150 | 400 |

| Selenium (mg/kg) | 0.4 | 0.8 |

Experimental design and treatments

Seven sows without any clinical symptoms of disease and their litters were selected directly after birth to participate in the experiment. From each litter, 10 piglets without any clinical symptoms of disease were selected for the experiment. Of these, five piglets were allocated to receive an oral supplement of Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC-PTA-6475 (8 × 107 ± 3 × 107 cfu/dose) and Lactobacillus plantarum L1-6 (2 × 109 ± 5 × 107 cfu/dose) three times a week, from 3 days of age until weaning at 35 days of age. The remaining five piglets received a control supplement (same media as the supplemented group, but without the Lactobacillus) which was administered in the same way as the probiotics supplement. The allocation of the piglets to the two different groups was balanced for weight and sex and much as possible. One researcher (JD) had the responsibility for the preparation of the probiotic and control supplements. The staff at the farm received the supplements labelled with different markings and they provided the supplements to the pigs. None of the farm staff nor the researcher JD were involved in the performance of the attention bias test. At 26.6 ± 0.7 days of age, 31 control piglets (11 females and 20 males) and 33 supplemented piglets (14 females and 19 males) were exposed to one attention bias test in which their behavioural reactions towards and unfamiliar dog bark sound were assessed.

Preparation of the bacterial strains

Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC-PTA-6475 and Lactobacillus plantarum L1-6, (kindly provided by Stefan Roos, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences) were cultured separately in MRS broth (Oxoid Ltd, Basingstoke, England) over night. The microbial cells from the fresh cultures were pelleted by centrifugation at 5000 g for 10 min at 4℃. The supernatants were discarded, the cell pellets re-suspended in saline solution and were again pelleted by centrifugation at 5000 g for 10 min. After discarding the supernatants, the cell pellets were dissolved in a water solution containing 10% sucrose and 1% ascorbic acid. The solutions were homogenized, dispensed in 100 µl aliquots and were stored at -80℃ until use. The levels of bacteria in the prepared bacterial solutions were assessed by plate counting, using MRS agar (Oxoid Ltd).

Supplementation to pigs

At each supplementation, an aliquot of each bacterial strain (each 100 µl) was thawed and mixed with 20 µl caramel colour and 80 µl water. The solution was supplemented to the piglet via a 1 ml syringe. The control pigs were supplemented with the same amount of caramel colour, water and sucrose solution, but without any bacteria.

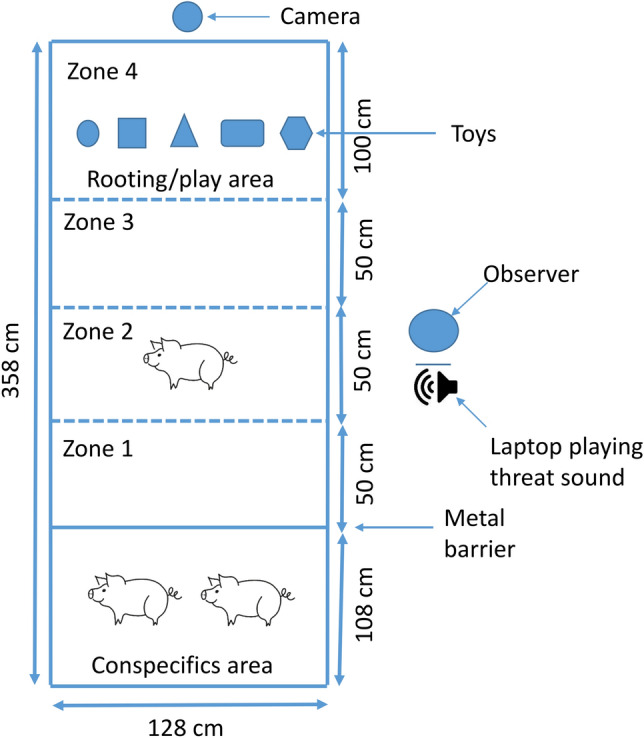

Attention bias test

The experimenters conducting the attention bias test were blind to the treatment of the piglets. An unfamiliar arena (Fig. 4) located in a different room (an empty pig stall) was used to assess attention bias. The arena consisted of three separate areas, a rooting and playing area bedded with straw and five different types of dog toys (placed from left to right: Ball, Hol-ee ball, Tire, Rope and Rope with rubber ring), a middle part (slatted metal floor) and a straw-bedded conspecifics area that was visible but not accessible to the test piglet. Two piglets (1 male and 1 female) from the same litter but not part of the experimental treatments were located in the conspecifics area in order to reduce isolation stress for the testing piglets. Thirty minutes before the start of the test, the conspecifics were habituated to the novel environment and stayed until all the piglets of the same litter had been tested. We observed that the conspecifics were either very calm or sleeping within 30 min of moving to the test arena, so it was assumed that 30 min was sufficient habituation. The gate separating the conspecifics area was made of metal bars that allowed visual, auditory and physical contact. The order in which the piglets within a litter were tested was random but balanced for treatment to ensure an even distribution of the treatments throughout the testing period (i.e., if the first tested piglet was a control, the second was a supplemented, the third was a control, etc.). In addition, four litters started with a randomly selected control piglet and three with a randomly selected supplemented piglet to control for any potential effects of being the first tested piglet. Random numbers were generated using the standard = RAND() function in Microsoft Excel.

Figure 4.

Attention bias arena. Pig vector from https://pixabay.com/vectors/pig-piglet-no-background-animal-2660356/.

The attention bias test was divided into two phases: a 90 s ‘before’ phase and a 90 s ‘after’ threat phase. The after phase started with a 15 s playback ‘threat’ sound of an aggressive dog bark. The piglets were raised indoors and had never seen a dog, and therefore this sound was most likely unfamiliar. Before the start of the test, the test piglet was gently lifted from its pen and placed into a trolley with straw and taken to the test arena. At time 0, it was placed in zone 2 (Fig. 4). It was then left to explore the arena for 90 s (before threat phase). At 90 s, the threat sound was played back from a computer located next to zone 2 and the piglet was left inside the arena for an additional 90 s (after threat phase). We did not control the piglet’s location in the arena when we played the threat sound, because if we had done that then we would not have been able to give the sound at the same exact time for each piglet.

The behaviours and locations described in the ethogram in Table 3, and the latency to the first time touching, or interacting with the toys were later analysed using the mangold interact software for behavioural analysis (Mangold International GmbH, Arnstorf, Germany) from video recordings by three different observer blind to the treatments. The agreement between observers was high (Kappa statistics between ranged between 0.77 and 1).

Table 3.

Ethogram with behaviours scored during the attention bias test.

| Behaviour (duration) | Definition |

|---|---|

| Standing | All four hooves are on the pen floor with limbs extended and without more than 1 step within 1 s |

| Walking | The piglet takes at least 2 steps within 1 s |

| Running | A fast paced movement involving all four legs |

| Vigilant | The head positioned at shoulder height or higher |

| Attention to threat | The head oriented towards the direction of the threat |

| Exploring | Sniffing or licking the floors, walls or pen fixtures |

| Interacting with toys | Touching, sniffing or manipulating toys |

| Conspecifics directed behaviours | Sniffing or licking the gate or positioning the snout between the bars |

| Rooting | Snout movement along the floor in the straw in area 3 |

| Location | Time spent in zone 1, 2, 3 and 4 |

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using R (version 4.0.2) and R studio (version 1.4.1093)71. Not all periods were exactly 90 s for all animals (mean ± se were 95 ± 0.68 s for period 1 and 84 ± 0.70 s for period 2), and therefore a correction was applied to account for this (corrected variable = variable / actual period duration * 90 s). Normality and homoscedasticity assumptions were visually checked using QQ plots (LMERConvenienceFunctions package72). Variables that were not normally distributed were square root transformed and then it was checked if they met the assumptions of normality (variables: vigilance behaviour, exploring). However, the variable ‘exploring’ still did not meet normality assumptions, and therefore two observations with residuals greater than 2.5 were excluded from analysis, after which normality assumptions were met. In case data transformation was not sufficient and there were no clear outliers, a non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test was used (variables: time spent in zones 1, 2, 3 and 4, interacting with toys, attention to threat) and the p-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons where necessary (time spent in the different zones). The duration of the variables described in Table 2 were initially analysed by linear mixed models (packages lme473 and lmerTest74) with treatment, sex, phase and test order (and their interactions) as fixed effects and litter as a random effect. Non-significant terms and interactions were dropped in the final model. Post-hoc Tukey tests were performed with the package emmeans75. The data presented in Figs. 1, 2 and 3 was plotted using the package ggplot2 in R76.

Author contributions

E.V. wrote the manuscript text. E.V. performed the statistical analysis and prepared the figures and tables. All authors have designed the experiment. All authors have critically reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Swedish Research Council Formas (grant number 2015-00630) and Stiftelsen Lantbruksforskning (grant number O-17-20-971). Open access funding provided by the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. No funding bodies had any role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed for the current study are available in the Open Science Framework repository: (https://osf.io/c9bfk/?view_only=328805b477ab4b2f95d956739fda87c9).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Clarke G, et al. Minireview: gut microbiota: the neglected endocrine organ. Mol. Endocrinol. 2014;28:1221–1238. doi: 10.1210/me.2014-1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cryan JF, O'Mahony SM. The microbiome-gut-brain axis: from bowel to behavior. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2011;23:187–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hollister EB, et al. Structure and function of the healthy pre-adolescent pediatric gut microbiome. Microbiome. 2015;3:36. doi: 10.1186/s40168-015-0101-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng J, et al. Discordant temporal development of bacterial phyla and the emergence of core in the fecal microbiota of young children. ISME J. 2016;10:1002–1014. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim MY, Song E-J, Kang KS, Nam Y-D. Age-related compositional and functional changes in micro-pig gut microbiome. GeroScience. 2019;41:935–944. doi: 10.1007/s11357-019-00121-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim J, Nguyen SG, Guevarra RB, Lee I, Unno T. Analysis of swine fecal microbiota at various growth stages. Arch. Microbiol. 2015;197:753–759. doi: 10.1007/s00203-015-1108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faith JJ, et al. The long-term stability of the human gut microbiota. Science. 2013;341:1237439. doi: 10.1126/science.1237439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Weerth C. Do bacteria shape our development? Crosstalk between intestinal microbiota and HPA axis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017;83:458–471. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heijtz RD, et al. Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:3047–3052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010529108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sudo N, et al. Postnatal microbial colonization programs the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system for stress response in mice. J. Physiol. 2004;558:263–275. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.063388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rutsch A, Kantsjö JB, Ronchi F. The gut-brain axis: how microbiota and host inflammasome influence brain physiology and pathology. Front. Immunol. 2020 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.604179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bravo JA, et al. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:16050–16055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102999108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamada N, Seo S-U, Chen GY, Núñez G. Role of the gut microbiota in immunity and inflammatory disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013;13:321–335. doi: 10.1038/nri3430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Regulation of the stress response by the gut microbiota: implications for psychoneuroendocrinology. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:1369–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koh A, De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Bäckhed F. From Dietary fiber to host physiology: short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell. 2016;165:1332–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker A, Fonseca S, Carding SR. Gut microbes and metabolites as modulators of blood-brain barrier integrity and brain health. Gut Microb. 2020;11:135–157. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2019.1638722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silva YP, Bernardi A, Frozza RL. The role of short-chain fatty acids from gut microbiota in gut-brain communication. Front. Endocrinol. 2020 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neufeld KM, Kang N, Bienenstock J, Foster JA. Reduced anxiety-like behavior and central neurochemical change in germ-free mice. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2011;23:255–e119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clarke G, et al. The microbiome-gut-brain axis during early life regulates the hippocampal serotonergic system in a sex-dependent manner. Mol. Psychiatry. 2013;18:666–673. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foster JA, McVeyNeufeld K-A. Gut–brain axis: how the microbiome influences anxiety and depression. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36:305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Mahony SM, et al. Early life stress alters behavior, immunity, and microbiota in rats: implications for irritable bowel syndrome and psychiatric illnesses. Biol. Psychiatry. 2009;65:263–267. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidt B, et al. Establishment of normal gut microbiota is compromised under excessive hygiene conditions. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28284. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mulder IE, et al. Environmentally-acquired bacteria influence microbial diversity and natural innate immune responses at gut surfaces. BMC Biol. 2009;7:79. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-7-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quigley EMM. Probiotics in functional gastrointestinal disorders: what are the facts? Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2008;8:704–708. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dowarah R, Verma AK, Agarwal N. The use of Lactobacillus as an alternative of antibiotic growth promoters in pigs: a review. Anim. Nutr. 2017;3:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cussotto S, Sandhu KV, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. The neuroendocrinology of the microbiota-gut-brain axis: a behavioural perspective. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2018;51:80–101. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2018.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barros-Santos T, et al. Effects of chronic treatment with new strains of Lactobacillus plantarum on cognitive, anxiety- and depressive-like behaviors in male mice. PLoS ONE. 2020 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu W-H, et al. Alteration of behavior and monoamine levels attributable to Lactobacillus plantarum PS128 in germ-free mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2016;298:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis DJ, et al. Lactobacillus plantarum attenuates anxiety-related behavior and protects against stress-induced dysbiosis in adult zebrafish. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:33726. doi: 10.1038/srep33726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jang HM, Lee KE, Kim DH. The preventive and curative effects of Lactobacillus reuteri NK33 and bifidobacterium adolescentis NK98 on immobilization stress-induced anxiety/depression and colitis in mice. Nutrients. 2019 doi: 10.3390/nu11040819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buffington SA, et al. Microbial reconstitution reverses maternal diet-induced social and synaptic deficits in offspring. Cell. 2016;165:1762–1775. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang N, et al. Efficacy of probiotics on stress in healthy volunteers: a systematic review and meta-analysis based on randomized controlled trials. Brain Behav. 2020;10:e01699. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu RT, Walsh RFL, Sheehan AE. Prebiotics and probiotics for depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019;102:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyte M. Microbial endocrinology: host-microbiota neuroendocrine interactions influencing brain and behavior. Gut Microb. 2014;5:381–389. doi: 10.4161/gmic.28682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tabouy L, et al. Dysbiosis of microbiome and probiotic treatment in a genetic model of autism spectrum disorders. Brain Behav. Immun. 2018;73:310–319. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mao J-H, et al. Genetic and metabolic links between the murine microbiome and memory. Microbiome. 2020;8:53. doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00817-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mendl M, Burman OHP, Paul ES. An integrative and functional framework for the study of animal emotion and mood. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2010;277:2895–2904. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.0303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kraimi N, et al. Influence of the microbiota-gut-brain axis on behavior and welfare in farm animals: a review. Physiol. Behav. 2019;210:112658. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2019.112658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiao L, et al. A reference gene catalogue of the pig gut microbiome. Nat. Microbiol. 2016;1:16161. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Douglas C, Bateson M, Walsh C, Bédué A, Edwards SA. Environmental enrichment induces optimistic cognitive biases in pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2012;139:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2012.02.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brydges NM, Leach M, Nicol K, Wright R, Bateson M. Environmental enrichment induces optimistic cognitive bias in rats. Anim. Behav. 2011;81:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2010.09.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paul ES, Harding EJ, Mendl M. Measuring emotional processes in animals: the utility of a cognitive approach. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2005;29:469–491. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crump A, Arnott G, Bethell E. Affect-driven attention biases as animal welfare indicators: review and methods. Animals. 2018;8:136. doi: 10.3390/ani8080136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hutton SB. Cognitive control of saccadic eye movements. Brain Cogn. 2008;68:327–340. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dolan RJ, Vuilleumier P. Amygdala automaticity in emotional processing. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2003;985:348–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bar-Haim Y, Lamy D, Pergamin L, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van Ijzendoorn MH. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: a meta-analytic study. Psychol. Bull. 2007;133:1–24. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verbeek E, Colditz I, Blache D, Lee C. Chronic stress influences attentional and judgement bias and the activity of the HPA axis in sheep. PLoS ONE. 2019 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee C, Verbeek E, Doyle R, Bateson M. Attention bias to threat indicates anxiety differences in sheep. Biol. Lett. 2016 doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2015.0977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brilot BO, Bateson M. Water bathing alters threat perception in starlings. Biol. Lett. 2012;8:379–381. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2011.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luo L, Reimert I, de Haas EN, Kemp B, Bolhuis JE. Effects of early and later life environmental enrichment and personality on attention bias in pigs (Sus scrofa domesticus) Anim. Cogn. 2019;22:959–972. doi: 10.1007/s10071-019-01287-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bögels SM, Mansell W. Attention processes in the maintenance and treatment of social phobia: hypervigilance, avoidance and self-focused attention. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2004;24:827–856. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bethell EJ, Holmes A, MacLarnon A, Semple S. Evidence that emotion mediates social attention in Rhesus Macaques. PLoS ONE. 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cisler JM, Koster EHW. Mechanisms of attentional biases towards threat in anxiety disorders: an integrative review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010;30:203–216. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koster EHW, Crombez G, Verschuere B, Van Damme S, Wiersema JR. Components of attentional bias to threat in high trait anxiety: facilitated engagement, impaired disengagement, and attentional avoidance. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006;44:1757–1771. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mogg K, Bradley B, Miles F, Dixon R. Brief report time course of attentional bias for threat scenes: testing the vigilance-avoidance hypothesis. Cogn. Emot. 2004;18:689–700. doi: 10.1080/02699930341000158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mogg K, Bradley BP. A cognitive-motivational analysis of anxiety. Behav. Res. Ther. 1998;36:809–848. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ellenbogen MA, Schwartzman AE, Stewart J, Walker CD. Stress and selective attention: the interplay of mood, cortisol levels, and emotional information processing. Psychophysiology. 2002;39:723–732. doi: 10.1017/s0048577202010739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koster EHW, Verschuere B, Crombez G, Van Damme S. Time-course of attention for threatening pictures in high and low trait anxiety. Behav. Res. Ther. 2005;43:1087–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Richards HJ, Benson V, Donnelly N, Hadwin JA. Exploring the function of selective attention and hypervigilance for threat in anxiety. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2014;34:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McLeman MA, Mendl M, Jones RB, White R, Wathes CM. Discrimination of conspecifics by juvenile domestic pigs, Sus scrofa. Anim. Behav. 2005;70:451–461. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2004.11.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kristensen HH, Jones RB, Schofield CP, White RP, Wathes CM. The use of olfactory and other cues for social recognition by juvenile pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2001;72:321–333. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1591(00)00209-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nores C, Llaneza L, Álvarez Á. Wild boar "Sus scrofa" mortality by hunting and wolf "Canis lupus" predation: an example in northern Spain. Wildlife Biol. 2008;14:44–51. doi: 10.2981/0909-6396(2008)14[44:WBSSMB]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Verbeek E, Ferguson D, Lee C. Are hungry sheep more pessimistic? The effects of food restriction on cognitive bias and the involvement of ghrelin in its regulation. Physiol. Behav. 2014;123:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Forkman B, Boissy A, Meunier-Salaün MC, Canali E, Jones RB. A critical review of fear tests used on cattle, pigs, sheep, poultry and horses. Physiol. Behav. 2007;92:340–374. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ruis MAW, et al. Adaptation to social isolation: acute and long-term stress responses of growing gilts with different coping characteristics. Physiol. Behav. 2001;73:541–551. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(01)00548-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stolba A, Wood-Gush DGM. The behaviour of pigs in a semi-natural environment. Anim. Prod. 1989;48:419–425. doi: 10.1017/S0003356100040411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fleming SA, Dilger RN. Young pigs exhibit differential exploratory behavior during novelty preference tasks in response to age, sex, and delay. Behav. Brain Res. 2017;321:50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bethell EJ, Cassidy LC, Brockhausen RR, Pfefferle D. Toward a standardized test of fearful temperament in primates: a sensitive alternative to the human intruder task for laboratory-housed Rhesus Macaques (Macaca mulatta) Front. Psychol. 2019 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.du Sert NP, et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLOS Biol. 2020;18:e3000410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.European Union. Council Directive 2008/120/EC of 18 December 2008 laying down minimum standards for the protection of pigs. Off. J. Eur. Union (2018).

- 71.R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. R Core Team; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tremblay, A. & Ransijn, J. LMERConvenienceFunctions: Model Selection and Post-Hoc Analysis for (G)LMER Models. R package version 3.0. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=LMERConvenienceFunctions (2020).

- 73.Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. 67, 48. 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 (2015).

- 74.Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B. & Christensen, R. H. B. lmerTest Package: tests in linear mixed effects models. 82, 26. 10.18637/jss.v082.i13 (2017).

- 75.Russell, L. Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. R package version 1.5.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans (2020).

- 76.Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org (2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed for the current study are available in the Open Science Framework repository: (https://osf.io/c9bfk/?view_only=328805b477ab4b2f95d956739fda87c9).