Abstract

Living systems have not only the exemplary capability to fabricate materials (e.g. wood, bone) under ambient conditions but they also consist of living cells that imbue them with properties like growth and self-regeneration. Like a seed that can grow into a sturdy living wood, we wondered: can living cells alone serve as the primary building block to fabricate stiff materials? Here we report the fabrication of stiff living materials (SLMs) produced entirely from microbial cells, without the incorporation of any structural biopolymers (e.g. cellulose, chitin, collagen) or biominerals (e.g. hydroxyapatite, calcium carbonate) that are known to impart stiffness to biological materials. Remarkably, SLMs are also lightweight, strong, resistant to organic solvents and can self-regenerate. This living materials technology can serve as a powerful biomanufacturing platform to design and develop advanced structural and cellular materials in a sustainable manner.

Keywords: living materials, circular material economy, sustainability, self-regeneration, microbial materials, biomanufacturing, cellular materials

Graphical Abstract

Living (Microbial) cells are dynamic soft entities, but we show that they can be self-assembled under ambient conditions to form living materials that are as stiff and strong as various biomaterials and human-made materials. The living materials are resistant to organic solvents and can also be regenerated several times, enabling an advanced biomanufacturing technology and circular material economy.

1. Introduction

Innovation in materials science and technology has been a major driving force for the advancement of human civilization.[1] However, until relatively recently, materials innovations were pursued and implemented without much regard for global sustainability.[2] This must change rapidly in the face of the urgent threats of global warming and potentially irreversible ecological damage. Unlike our linear materials economy, which follows a make-use-dispose model, biology provides a template for a circular materials economy, in which abundant feedstocks are directed by cells into living materials that involve either regeneration or biodegradation at the end of the material’s life cycle. In most cases, these structure-building processes occur at ambient temperature and pressure, without the need for “heat-beat-treat” modalities of materials processing that are a hallmark of synthetic materials.[3–6] In many cases, biology accomplishes this task solely by using living cells and their byproducts as structural building blocks. The ability to adapt this approach to structure building for the purposes of scalable materials fabrication would be of great benefit to the development of more sustainable manufacturing practices.

In the last few decades, living cells have been engineered extensively to produce a wide variety of small molecules, polymers, drugs and fuels.[7] More recently, cells have also been engineered to produce functional materials directly and/or modulate their properties, which has led to the emergence of the new field of engineered living materials (ELMs).[8–14] Early examples of ELMs demonstrated binding to synthetic materials (e.g. stainless steel), templating nanoparticles (e.g. gold) and immobilizing enzymes (e.g. amylase).[15, 16] Additional work has focused on ELMs that function as catalytic surfaces, filtration membranes, under-water adhesives, pressure sensors, conductive films, gut adhesives, etc.[17–30] In spite of rapid progress in the field, it should be noted that there are few examples of ELMs that combine the structure-building capabilities of cells with their other capabilities, like self-regeneration, self-healing, or environmental responsiveness. ELM technologies that can streamline fabrication by relying more on autonomous cellular functions could help advance the field from a fundamental perspective and lead to ELMs compatible with scalable manufacturing techniques. Here we report the fabrication of a new class of ELMs wherein microbial cells serve as the sole structural building block. These materials are not only one of the stiffest known ELMs, but they can also self-regenerate through the action of living cells that remain embedded within the material for more than one month after their fabrication, suggesting that they could fit into a model of a circular material economy (Figure 1A).

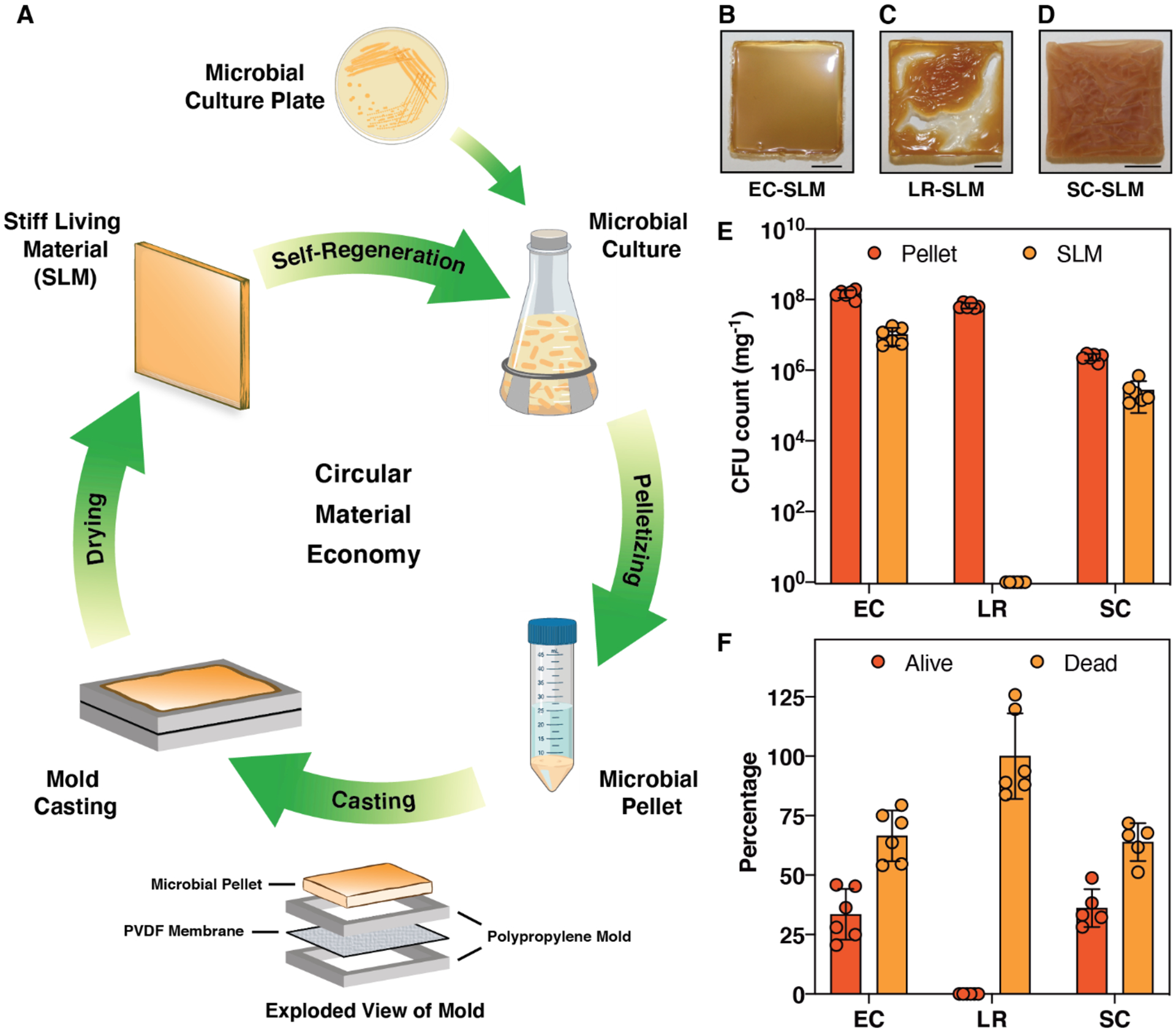

Figure 1.

Fabrication of stiff living materials (SLMs). (A) Schematic shows the various stages involved in the fabrication and life cycle of SLMs produced solely from microbial cells. PVDF-Polyvinylidene fluoride. Optical images of SLM fabricated at 25 °C and 40±5 % relative humidity by air-drying for 24 h from (B) Escherichia coli (EC); (C) Lactobacillus rhamnosus (LR) and (D) Saccharomyces cerevisiae (SC). Scale bar 0.5 cm. (E) Colony forming unit (CFU) analysis of SLMs and their microbial pellet precursors. (F) Percentage of live and dead cells estimated from the SLMs with respect to their pellet (dry weight corrected). n=6. Bars represent mean values, and the error bars are standard deviation.

2. Evolution and fabrication of SLMs

Many published examples of ELMs take the form of soft materials in the form of biofilms, semi-solids or hydrogels. In these examples, cells were either combined with synthetic polymers or biopolymers to create composites, or they were designed/selected to produce a specific extra-cellular matrix (e.g. curli fibers, cellulose).[15–30] In our recent work, we have shown that this approach can be used to fabricate macroscopic stiff (2–4 GPa) thin films by exploiting the stiff structural characteristics of curli fibers.[31] In contrast to the above approaches, we wondered whether living cells alone, without any extracellular matrix, could serve as the primary building block in ELM fabrication and thereby incorporate aspects of self-regeneration. In order to explore this possibility, we started with a strain of Escherichia coli (PQN4), derived from an MC4100 lineage of laboratory strains, that is known not to produce any extracellular matrix components such as curli fibers, fimbriae, flagella or cellulose.[15] After culturing for 24 h in lysogeny broth, the E. coli cells were pelleted and washed with deionized water to remove the spent media (Figure S1). The resulting pellet, when drop-cast onto a glass slide and allowed to dry under ambient conditions, resulted in a brittle, transparent living material that fragmented during the drying process (Figure S2A). However, upon seeing the potential for higher quality materials to be made with this basic approach, we iteratively refined the fabrication protocol in order to obtain increasingly robust prototypes (Figure S2, Table S1). We found that increasing the amount of wet biomass starting material and using a mold could slightly decrease the fragmentation of the SLM. Although this led to a material with a glossy top surface (Figure S2F), the bottom surface (Figure S2G) of the material had patches of cells that were not dried effectively, inhibiting the formation of a cohesive material. We reasoned that the non-porous glass substrate was inhibiting effective drying on the bottom surface of the SLM.

Applying a similar drop casting protocol on porous substrates like copper or stainless-steel mesh led to more uniformly dried materials with less fragmentation but left an imprint on the bottom surface of the SLM (Figure S2K). Further attempts to use polymeric porous substrates either led to strong adhesion that prevented the removal of the SLM (e.g. nylon), or SLMs with curved architectures (e.g. PTFE-coated stainless steel), presumably due to different drying rates on the top and bottom surfaces. We then reasoned that a combination of vacuum suction and a substrate with balanced adhesion strength could lead to flat, cohesive materials that could be removed from the substrate and be self-standing. Accordingly, we applied the drying protocol to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane that is typically used to bind proteins in western blots. By drop casting the E. coli cell pellet on a PVDF membrane mounted on a Millipore SNAP i.d. Mini Blot Holder connected to low vacuum suction, we were able to achieve a flat, mostly cohesive material, though some fragments still formed (Figure S2U,V). Counterintuitively, the same setup in the absence of suction led to fragmentation-free, flat SLMs. Although the adhesion of the SLM to the PVDF membrane prevented it from being removed manually, we found that the membrane could be removed by applying a small amount of dimethylformamide (DMF), which is known to solubilize PVDF. We also tried using higher temperatures (50/75/100 °C) to speed up SLM formation, but this led to samples with extensive cracks and discoloration or charring (Figure S2N–T).

An optimized fabrication of the SLM involved firmly sandwiching the PVDF membrane between two polypropylene molds, then casting the E. coli cell pellet on top of the membrane and drying under ambient conditions (25 °C and 40±5 % relative humidity) for 24 h (Figure S3). This yielded a fragmentation-free glossy flat SLM of 0.4–1.2 mm thickness (Figure 1B). Given that the precursor material to the SLM consisted solely of live E. coli cells (EC-SLM), we were curious about how the fabrication protocol affected cell viability. Remarkably, one milligram of EC-SLM was found to have 1.0±0.5 *107 colony forming units (CFUs), while its precursor (i.e. the wet cell pellet) had a CFU count of 1.5±0.04 *108 mg−1 (Figure 1E). We then employed the same protocols to the Gram-positive bacterium Lactobacillus rhamnosus and the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae to investigate whether other microbes can also form SLMs in a similar manner. Interestingly, L. rhamnosus resulted in a SLM (LR-SLM) with a wrinkled top surface, while the SLM from S. cerevisiae (SC-SLM) had extensive cracks and a non-glossy texture (Figure 1C,D and Figure S4,5). CFU analysis revealed that SC-SLM had 2.7±0.2 *105 mg−1, but no cells were found to be alive in the LR-SLM (Figure 1E). Since a large fraction of the wet weight of the cell pellets was water, we normalized the CFU counts for all three SLMs to the dry mass of the cell pellets (Figure S6,7) and found that 33.5%, 0% and 36.1% of the original cells were alive in EC-SLM, LR-SLM and SC-SLM, respectively (Figure 1F). Thus, we have demonstrated the very first examples of living bulk materials fabricated entirely from viable microbial cells. Further, in order to probe whether biomass from lysed cells could produce materials with similar qualitative properties, we used E. coli cells that had been lysed by exposure to 70% ethanol. After drying, these materials were not able to maintain a cohesive structure and as expected no living cells were recoverable by CFU analysis (Figure S8).

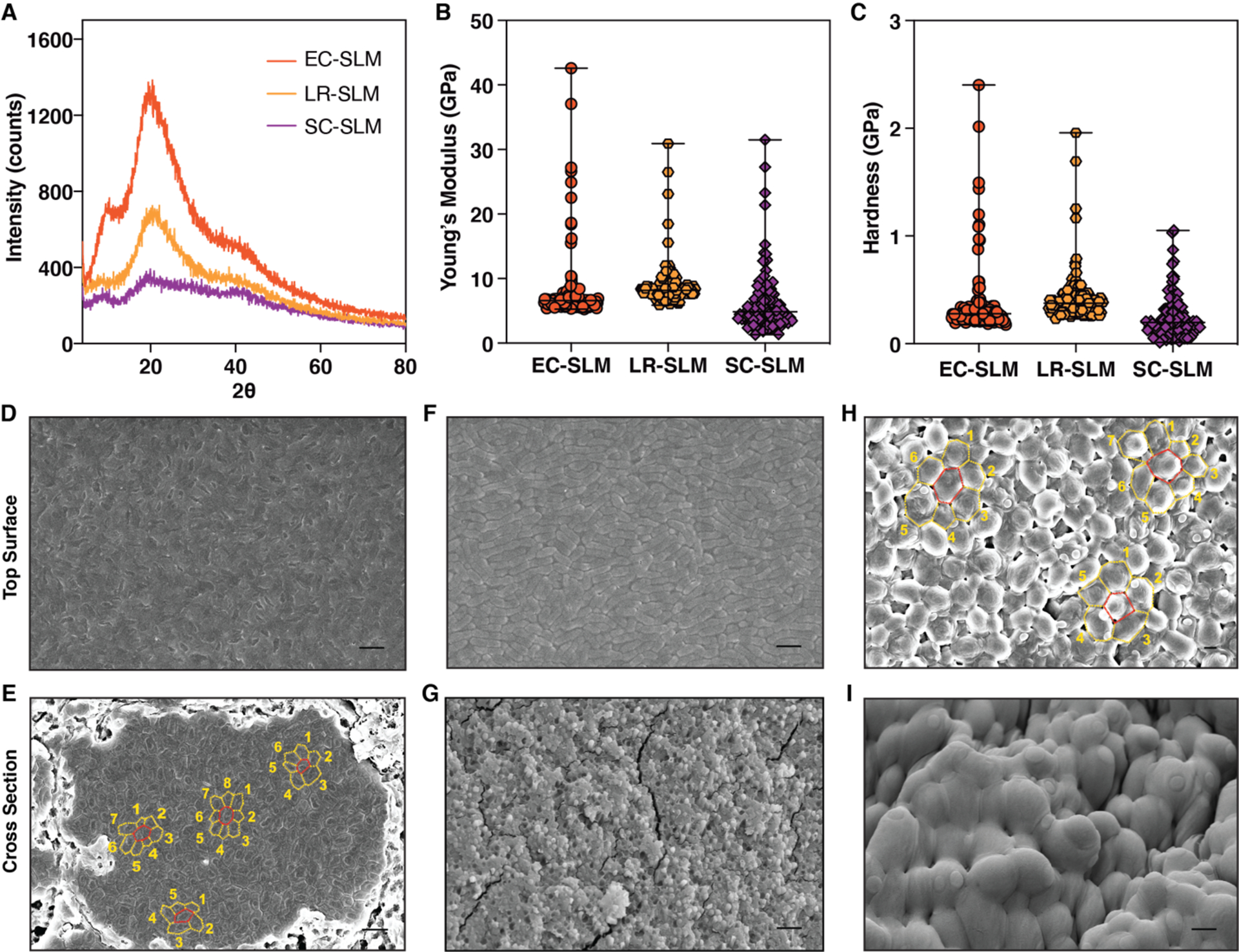

3. Physical characteristics of SLMs

Given the highly heterogeneous molecular composition of SLMs, we sought to understand their structure with a range of analytical techniques. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis of SLMs indicated that both EC-SLM and LR-SLM have a main diffraction peak corresponding to a d-spacing value of 0.44 nm, while EC-SLM has two additional peaks at 0.88 nm and 0.23 nm (Figure 2A). Although it is difficult to assign the identity of these peaks, the spectra do establish that SLMs are amorphous materials. Thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) showed a slightly negative slope below 100 °C that is likely due to water loss, followed by degradation above 130 °C (Figure S9). Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis of EC-SLM showed a glass-transition-like second-order transition (50–60 °C) during the first cycle of the heating curve (Figure S10). However, the successive heat-cool cycles did not reveal the presence of such transitions, suggesting the probable role of water acting as a plasticizer. Similar features were also observed in DSC traces of LR-SLM and SC-SLM (Figure S11). EC-SLM appeared to be somewhat transparent by qualitative observation, but the absorption spectrum showed less than 10% transparency, across the visible range (Figure S13). Based on the cell viability experiments showing that only ~35% of the cells in EC-SLM were alive after the fabrication protocol, we reasoned that the remaining cells likely lysed during the drying process, releasing their periplasmic and cytosolic contents. This mixture, containing nucleic acids, lipids, and proteins assembles into an amorphous network, with residual water serving as a plasticizer.

Figure 2.

Physical and structural characteristics of SLMs. (A) X-ray diffraction spectra of SLMs of various microbial composition. (B) Young’s modulus and (C) Hardness of SLMs obtained from nanoindentation (n≥125). The graphs show median and the range. Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) images of EC-SLM (D,E); LR-SLM (F,G) and SC-SLM (H,I). (D,F,H) Top surface of SLM. (E,G,I) Cross-section of SLM. Scale bar 2 μm. (E,H) show the planar packing density, η (number of neighboring cells within the same plane).

4. Mechanical characteristics of SLMs

The mechanical properties of the SLMs were investigated by nanoindentation, as it uses small loads that are suitable for biomaterials and can probe heterogeneity in microscopic dimensions.[32, 33] SLMs were indented (n≥125) with a Berkovich diamond tip to obtain the continuous load, P, versus depth of penetration, h, curves. Nanoindentation experiments showed smooth P-h curves, which were analyzed using the Oliver-Pharr method to extract Young’s modulus, E, and hardness, H, of the SLMs (Figure S14). EC-SLM was found to have E ranging from 5 to 42 GPa, while their H were about 0.2 to 2.4 GPa (Figure 2B,C). LR-SLM and SC-SLM also showed stiffness and hardness values in a similar range as EC-SLM (Figure 2B,C). The mechanical characteristics of SLMs were consistent across different samples, while the slightly wider distribution of stiffness could be attributed to the heterogeneous components and their packing (Figure S15). Interestingly, the SLM obtained from lysed E. coli (70% ethanol treatment) also exhibited similar E and H values, which further supports that cellular components can self-assemble, albeit heterogeneously, to form stiff materials (Figure S16).

5. Morphological characteristics of SLMs

In order to understand how the structure of SLM materials, formed exclusively from microbial cells, was able to remain stiff while preserving cell viability, we turned to electron microscopy. Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) imaging of the top surface of EC-SLM revealed a dense matrix of E. coli cells which all appear to be ruptured (Figure 2D). But from CFU analysis, we know that E. coli cells are alive in EC-SLM, prompting us to investigate the core of the material. Cross-sectional imaging of EC-SLM showed a fascinating ordering of cells into tightly packed domains amidst loosely bound cells (Figure 2E and Figure S17). Each domain can comprise of anywhere between 3 to nearly 500 cells, spanning up to a width of 30 μm. It should be noted that E. coli is a rod-shaped cell but, in these domains, transforms to a polygonal prism with a planar packing density (η, number of neighboring cells within the same plane) of predominantly 6, although 5, 7 and 8 are also observed (Figure 2E). We speculate that the cells in the loosely bound regions have greater survivability compared to the tightly packed domains. Contrastingly, the top surface of LR-SLM was found to have an array of L. rhamnosus cells, whose rod-shaped structure appeared to be intact (Figure 2F and Figure S18). It is difficult to ascertain the η of L. rhamnosus due to their known inherent tendency to form chains. The cross-sectional images of LR-SLM revealed that the cells were lysed to form an amorphous heterogenous solid (Figure 2G). These FESEM images of LR-SLM provide additional evidence for the lack of CFU in the samples (Figure 1E,F). In contrast, SC-SLM was found to form a close packing of spherical shaped S. cerevisiae cells with η of 5, 6 and 7 (Figure 2H and Figure S19). Interestingly, the cross section of SC-SLM showed that S. cerevisiae cells were packed less densely at the core but formed tightly compressed layers both on the top and bottom surfaces (Figure 2I and Figure S19). Thus, it appears that lysis of S. cerevisiae cells forms a hard-protective shell on the outer surface and thereby enables cells at the core to survive to a greater extent.

6. Self-regeneration of SLMs

We then exploited the living cells embedded in the SLMs to develop a protocol for self-regeneration. When a small fragment (5–10 mg) of EC-SLM was introduced into selective media, the SLM started to disperse and the embedded cells started proliferating to form a turbid culture. After 24 h of culture, the cells were pelleted and cast onto the mold as per the same fabrication protocol described above in order to create the second generation (Gen II) EC-SLM fabricated from a fragment of the first generation (Gen I) EC-SLM (Figure 3A). The process could be repeated again to form a Gen III EC-SLM. Both Gen II and Gen III EC-SLMs were found to have a CFU count of around 107 mg−1, which is almost same as that of Gen I (Figure 3B). Moreover, nanoindentation studies showed that E (5–41 GPa) and H (0.2–2.5 GPa) of the Gen II and Gen III EC-SLMs were also similar to that of the Gen I sample (Figure 3C,D). CFU analysis of EC-SLM samples stored on the benchtop over time revealed that the value decreased to ~104 mg−1 on day 15 and 21 mg−1 on day 30 (Figure 3E). We calculated an exponential cell death rate of 0.43 per day.

Figure 3.

Self-regeneration and time-dependent cell viability of EC-SLM. (A) Optical images of first (Gen I), second (Gen II) and third (Gen III) generations of EC-SLM. A small fragment (dotted rectangle) of Gen I was cultured, pelletized and air-dried to produce the Gen II, which in turn resulted in Gen III. Scale bar 0.5 cm. (B) CFU count of Gen II and Gen III of EC-SLM. n=6. The graph shows mean values, and the error bars are standard deviation. (C) Young’s modulus and (D) Hardness of Gen II and Gen III EC-SLMs measured by nanoindentation (n≥125). The graphs show median and the range. (E) Time dependent CFU analysis of EC-SLM. n=6. The graph shows mean values, and the error bars are standard deviation.

7. Robustness of SLMs

In the process of optimizing our SLM fabrication protocol, we observed that the SLM does not appear to be affected by the DMF used to remove the PVDF membrane. We also noticed that EC-SLM did not disperse even when submerged in DMF. Intrigued by this observation, we submerged EC-SLM in a range of solvents with varying properties - hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, acetonitrile, absolute ethanol, methanol, DMF and deionized water (Figure S20). EC-SLM dispersed only in water and was completely stable in all of the other solvents, whose polarity index spans the entire spectrum. After 24 h of submersion in the various solvents, we subjected the samples to CFU analysis and were surprised to find values >106 mg−1 in all solvents except chloroform and methanol, which led to complete cell death (Figure 4A). When we repeated the solvent submersion and CFU analysis with the wet E. coli cell pellet, we found that the cells died completely in all the solvents, except for hexane and deionized water (Figure S21). The result with hexane may perhaps be explained by its complete lack of miscibility with water and lower density, allowing it to rest on top of the cell pellet. In contrast, EC-SLM was stable in both water-miscible and -immiscible organic solvents (Figure 4B) and showed no significant weight loss (Figure 4C) after 24 hours of incubation in various solvents, suggesting that the densely packed surface layer of the SLM, consisting of lysed cells, exhibits a protective effect on the cells embedded in the core. We also tested the robustness of EC-SLM by incubating it at 100 °C for 1 h and found a mean CFU count of over 700 mg−1 (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Solvent and temperature resistance of EC-SLM. (A) CFU count of EC-SLM and E. coli pellet after 24 h submersion in various solvents. CFU count of pellets were corrected for their dry weights. Hex: hexane; CHCl3: chloroform; EtOAc: ethyl acetate; ACN: acetonitrile, EtOH: absolute ethanol; MeOH: methanol; DMF: dimethylformamide. (B) Chart shows miscibility and immiscibility of organic solvents in water. (C) Normalized weights of EC-SLMs before and after 24 h submersion in solvents. (D) CFU count of EC-SLM and E. coli pellet after incubation at 100 °C for 1 h. n=6. The bar graphs represent mean values, and the error bars are standard deviation.

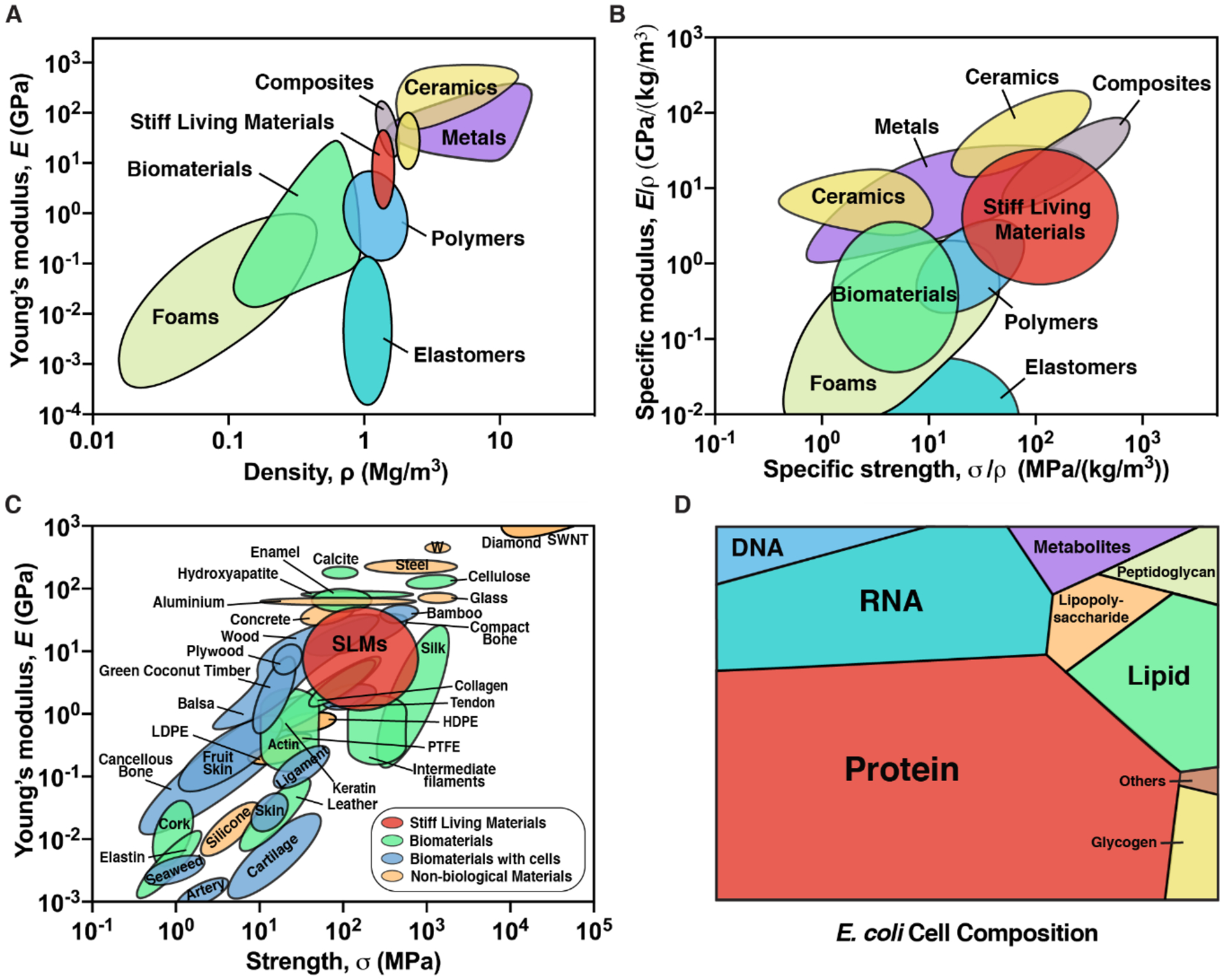

8. Mechanical landscape of SLMs

Based on our nanoindentation studies, it is evident that SLMs are remarkably stiff and hard for a material composed purely of microbial biomass. To put these properties into perspective, we provide a comparison of the mechanical properties of SLMs to other biomaterials and various types of human-made materials – metals, polymers, composites, ceramics, elastomers and foams. An Ashby plot of E versus density (ρ) shows that SLMs are stiffer than most biomaterials and polymers, and more comparable to composites (Figure 5A).[34] We also obtained the yield strength, σy (estimated using the relation σy = H/3) of SLMs, which was found to be about 60–800 MPa.[34, 35] In Figure 5B, we show the Ashby plot of specific modulus (E/ρ) and specific strength (σy/ρ), which indicates that the specific properties of SLMs are comparable to metals and ceramics, due to their low density.[36] Further, we provide specific examples of materials that are categorized into biomaterials (e.g. silk, collagen, cellulose etc.), biomaterials with cells (e.g. wood, skin, ligament etc.), non-biological materials (e.g. steel, glass, concrete, plastics etc.) and SLMs in an Ashby plot of E and strength, σ, in Figure 5C.[36, 37] Notably, the stiffness and strength of SLMs are comparable or superior to actin, balsa, cancellous bone, skin and plastics, amongst others, and they are comparable to robust structural materials such as silk, collagen, wood and concrete.

Figure 5.

Mechanical and compositional landscape of SLMs. Ashby plot of (A) Young’s modulus verses density, (B) Specific modulus verses specific strength and (C) Young’s modulus verses strength, for various classes of materials and SLMs. SWNT: Single-wall carbon nanotube; LDPE: low density polyethylene; HDPE: high density polyethylene, PTFE: polytetrafluoroethylene. Adapted with permission.[36] Adapted with permission.[37] (D) Voronoi tree diagram shows the relative amounts of the components present in the dry E. coli cell. Adapted with permission.[38]

9. Discussion

A living cell is a heterogenous mixture of proteins, nucleic acids, sugars etc. and to comprehend their contributions to SLM composition, we have presented a Voronoi tree diagram that shows the relative abundance of various components of a dry E. coli cell (Figure 5D, Table S2).[38] Although it is difficult to ascertain the role of each of these cellular components in the formation of SLMs, the ability to do so from three cell types that vary widely in their anatomy and composition suggests that some of the observed properties of SLMs (e.g. stiffness, hardness, cohesiveness) may arise from a mixture of many different biomolecules. Other examples of stiff structural materials, like wood and bone, are composed of cells embedded in extracellular matrix components (e.g. cellulose, lignin, collagen, hydroxyapatite) with precise molecular compositions and self-assembly mechanisms that have been optimized over millions of years of evolution to exhibit mechanical robustness and other functional material properties. Given this, it is noteworthy that even non-specific mixtures of biomolecules derived from microbial cells can create rigid materials that rival their naturally occurring counterparts in terms of stiffness and hardness. The inability of ethanol treated E. coli cells (wherein ethanol disrupts the lipid membrane and denatures the proteins) to form a cohesive fragmentation-free SLM highlights that cellular integrity is essential and also suggests that active cellular processes that may play an important role in the formation of SLMs.

Indeed, many microbes have developed molecular, structural, metabolic and physiological adaptations to keep them alive under low-water conditions (i.e. xerotolerance).[39–41] Some of these xerotolerance mechanisms (e.g. production of trehalose, extracellular polymeric substances, hydrophilins etc.) may contribute to SLM material properties, and will be investigated in future studies. Although dried microbes have been widely used (e.g. dry baker’s yeast) for a very long time and mechanisms of microbial xerotolerance have been studied for decades, these studies were usually carried out in small volumes (e.g. microliters of microbial culture) and focused on either deciphering the mechanisms of xerotolerance or enhancing the survivability of microbes.[41, 42] Other research on microbial desiccation has focused on maximizing their long-term viability during storage, for example when probiotics are combined with emulsifiers and other additives prior to lyophilization.[43] In spite of all the fundamental knowledge and technological advancements around microbial drying processes, to the best of our knowledge, dried microbes have not been investigated as building blocks for macroscopic structural materials, as we demonstrate here.

Although the feasibility of SLM formation using various cell types suggests the potential broad applicability of the approach, it is also interesting to note the differences in SLM appearance and material properties arising from the different microbes. For example, one could speculate that the outer membrane lipids of the gram negative E. coli could contribute to the glossy appearance of the EC-SLM compared to the LR-SLM, derived from the gram positive L. rhamnosus, which lacks the outer membrane.[44] The reported values of E of E. coli cell vary over a very broad range of 0.05 – 220 MPa, which strongly depends on the measuring technique and the cell membrane composition.[45] In comparison, the eukaryotic S. cerevisiae has a more complex cellular architecture with an inner cell wall comprised of chitin and glucan and an outer cell wall that consists of heavily glycosylated mannoproteins.[46] The ability of S. cerevisiae to modify its cell wall, dependent on external stresses and its better desiccation resistance compared to the bacteria in this study could also have contributed to the opaque appearance and different material properties of SC-SLM. Interestingly, a recent report described the glass-like properties of bacterial cytoplasm, suggesting that the cytoplasmic composition could also contribute to the formation of a cohesive and glossy EC-SLM.[47]

The high stability of SLMs even when fully immersed in organic solvents suggests near-term applications as a biodegradable alternative to the conventional plastics currently used in laboratory environments when working with such solvents. Other applications could involve specialized packaging applications where water resistance is non-essential or in space exploration, where microbes have been identified as critical foundries for materials fabrication and structure building. Of course, the water dispersibility of SLMs currently limits their use in aqueous environments or as replacements for conventional plastics in many applications. Future work will explore the use of engineered cells producing artificial extracellular matrices as a way to enhance water resistance and moldability of SLMs in order to address these challenges.

10. Conclusions

Creating materials that incorporate microbes is a growing sub-field within synthetic biology and biomanufacturing. Most previous endeavors have accomplished this by either combining cells with exogenously supplied polymeric scaffolds or by engineering the cells to produce specific ECM components. Here we simplify this process to the extreme by using only living cells as a precursor to the material of interest and employ only drying under ambient conditions to achieve rigid, cohesive materials. We have shown SLM fabrication to be compatible with several industrially relevant workhorse microbes, which could position it as a powerful biomanufacturing strategy that overcomes the inherent inefficiencies involving the separation of cells from their products. Given that the cells used in this work were not engineered in any way, the potential for using synthetic biology techniques to further enhance and tailor material properties is genuinely exciting. The incorporation of renewable feedstocks to fuel microbial growth could also position this approach as a promising manufacturing paradigm that is in line with a circular materials economy model.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Authors thank Prof. Ju Li and Dr. Antoni Sanchez-Ferrer for helpful discussions. National Science Foundation 2026 Idea machine (Big Ideas) for stimulation and support. Work was performed in part at the Center for Nanoscale Systems at Harvard. Funding: National Institutes of Health (1R01DK110770-01A1), the National Science Foundation (DMR 2004875) and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University. Author contributions: A.M.-B. conceived the project, designed, and performed all experiments. A.M.D.-T. contributed to SLM fabrication, CFU and solvent resistance studies. All authors discussed and analyzed data. A.M.-B. and N.S.J. wrote the manuscript. Competing interests: A.M.-B., A.M.D.-T. and N.S.J. are inventors on a patent application.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Avinash Manjula-Basavanna, Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, Harvard University, Boston, MA 02115, USA; Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Northeastern University, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Anna M. Duraj-Thatte, Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, Harvard University, Boston, MA 02115, USA Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Northeastern University, Boston, MA 02115, USA; Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA.

Neel S. Joshi, Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, Harvard University, Boston, MA 02115, USA Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Northeastern University, Boston, MA 02115, USA; Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA.

References

- [1].Sass SL, The Substance of Civilization: Materials and Human History from the Stone Age to the Age of Silicon, Arcade Publishing, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ellen MacArthur Foundation and McKinsey & Company, Toward the Circular Economy, 2013.

- [3].Benyus JM, Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature, Harper Perennial, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wegst UG, Bai H, Saiz E, Tomsia AP, Ritchie RO, Nat. Mater 2015, 14, 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Meyers MA, McKittrick J, Chen PY, Science 2013, 339, 773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Omenetto FG, Kaplan DL, Science 2010, 329, 528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Khalil AS, Collins JJ, Nat. Rev. Genet 2010, 11, 367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Nguyen PQ, Courchesne ND, Duraj-Thatte A, Praveschotinunt P, Joshi NS, Adv. Mater 2018, 30, e1704847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chen AY, Zhong C, Lu TK, ACS Synth. Biol 2015, 4, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gilbert C, Ellis T, ACS Synth. Biol 2019, 8, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].C Tang T, An B, Huang Y, Vasikaran S, Wang Y, Jiang X, Lu TK, Zhong C, Nat. Rev. Mater, 10.1038/s41578-020-00265-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Srubar WV III, Trends Biotechnol, 10.1016/j.tibtech.2020.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Rivera-Tarazona LK, Campbell ZT, Ware TH, Soft Matter, 10.1039/D0SM01905D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Service RF, Science 2020, 367, 841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Nguyen PQ, Botyanszki Z, Tay PK, Joshi NS, Nat. Commun 2014, 5, 4945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chen AY, Deng Z, Billings AN, Seker UO, Lu MY, Citorik RJ, Zakeri B, Lu TK, Nat. Mater 2014, 13, 515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Duraj-Thatte AM, Courchesne ND, Praveschotinunt P, Rutledge J, Lee Y, Karp JM, Joshi NS, Adv. Mater 2019, 31, e1901826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Praveschotinunt P, Duraj-Thatte AM, Gelfat I, Bahl F, Chou DB, Joshi NS, Nat. Commun 2019, 10, 5580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Manjula-Basavanna A. Tay PKR, Joshi NS, Green Chem 2018, 20, 3512. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Botyanszki Z, Tay PK, Nguyen PQ, Nussbaumer MG, Joshi NS, Biotechnol. Bioeng 2015, 112, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Courchesne N-MD, DeBenedictis EP, Tresback J, Kim JJ, Duraj-Thatte A, Zanuy D, Keten S, Joshi NS, Nanotechnology 2018, 29, 454002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Seker UO, Chen AY, Citorik RJ, Lu TK, ACS Synth. Biol 2017, 6, 266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Jensen HM, Albers AE, Malley KR, Londer YY, Cohen BE, Helms BA, Weigele P, Groves JT, Ajo-Franklin CM, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2010, 107, 19213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Charrier M, Li D, Mann VR, Yun L, Jani S, Rad B, Cohen BE, Ashby PD, Ryan KR, Ajo-Franklin CM, ACS Synth. Biol 2019, 8, 181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zhong C, Gurry T, Cheng AA, Downey J, Deng Z, Stultz CM, Lu TK, Nat. Nanotechnol 2014, 9, 858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Cao Y, Feng Y, Ryser MD, Zhu K, Herschlag G, Cao C, Marusak K, Zauscher S, You L, Nat. Biotechnol 2017, 35, 1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Gonzalez LM, Mukhitov N, Voigt CA, Nat. Chem. Biol 2020, 16, 126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Huang J, Liu S, Zhang C, Wang X, Pu J, Ba F, Xue S, Ye H, Zhao T, Li K, Wang Y, Zhang J, Wang L, Fan C, Lu TK, Zhong C, Nat. Chem. Biol 2019, 15, 34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Liu X, Yuk H, Lin S, Parada GA, Tang TC, Tham E, de la Fuente-Nunez C, Lu TK, Zhao X, Adv. Mater 2018, 30, 1704821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Liu X, Tang TC, Tham E, Yuk H, Lin S, Lu TK, Zhao X, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2017, 114, 2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Duraj-Thatte AM, Manjula-Basavanna A, Courchesne N-MD, Cannici GI, Sánchez-Ferrer A, Frank BP, van ‘t Hag L, Cotts SK, Fairbrother DH, Mezzenga R, Joshi NS, Nat. Chem. Biol (In press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Varughese S, Kiran MS, Ramamurty U, Desiraju GR, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2013, 52, 2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Jang J-I, Ramamurty U, CrystEngComm 2014, 16, 12. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Avinash MB, Raut D, Mishra MK, Ramamurty U, Govindaraju T, Sci. Rep 2015, 5, 16070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zhang P, Li SX, Zhang ZF, Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 529, 62. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ashby MF, Materials Selection in Mechanical Design, Butterworth-Heinemann, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Knowles TP, Buehler MJ, Nat. Nanotechnol 2011, 6, 469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Milo R, Phillips R, Orme N, Cell biology by the numbers, Garland Science, New York, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- [39].Wharton DA, Life at the limits : organisms in extreme environments, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK; New York, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lebre PH, De Maayer P, Cowan DA, Nat. Rev. Microbiol 2017, 15, 285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Potts M, Microbiol. Rev 1994, 58, 755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Reed G, Nagodawithana TW, Yeast technology, Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Potts M, Slaughter SM, Hunneke FU, Garst JF, Helm RF, Integr. Comp. Biol 2005, 45, 800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Auer GK, Weibel DB, Biochemistry 2017, 56, 3710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Tuson HH, Auer GK, Renner LD, Hasebe M, Tropini C, Salick M, Crone WC, Gopinathan A, Huang KC, Weibel DB, Mol. Microbiol, 2012, 84, 874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Klis FM, Mol P, Hellingwerf K, Brul S, FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 2002, 26, 239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Parry BR, Surovtsev IV, Cabeen MT, O’Hern CS, Dufresne ER, Jacobs-Wagner C, Cell, 2014, 156, 183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.