Abstract

The symbiosis between scleractinian corals and photosynthetic algae from the family Symbiodiniaceae underpins the health and productivity of tropical coral reef ecosystems. While this photosymbiotic association has been extensively studied in shallow waters (<30 m depth), we do not know how deeper corals, inhabiting large and vastly underexplored mesophotic coral ecosystems, modulate their symbiotic associations to grow in environments that receive less than 1% of surface irradiance. Here we report on the deepest photosymbiotic scleractinian corals collected to date (172 m depth), and use amplicon sequencing to identify the associated symbiotic communities. The corals, identified as Leptoseris hawaiiensis, were confirmed to host Symbiodiniaceae, predominantly of the genus Cladocopium, a single species of endolithic algae from the genus Ostreobium, and diverse communities of prokaryotes. Our results expand the reported depth range of photosynthetic scleractinian corals (0–172 m depth), and provide new insights on their symbiotic associations at the lower depth extremes of tropical coral reefs.

Subject terms: Symbiosis, Microbial ecology

The ecological success of scleractinian corals, the engineers of one of the most productive and diverse ecosystems on Earth, relies on a myriad of symbiotic associations with microorganisms [1]. Among these symbioses, the association between the coral host and unicellular algae from the family Symbiodiniaceae is central to coral health and powers the metabolically expensive process of calcification [2]. The coral host provides limited inorganic nutrients, while Symbiodiniaceae share essential organic compounds derived from their photosynthetic activity [3]. This light-dependent association has mainly been studied in shallow waters (<30 m) because of technical limitations imposed by traditional scientific scuba diving. However, photosynthetic scleractinian corals have been observed in the mesophotic reef slope down to 150–165 m depth [4, 5].

As depth increases, the waveband of solar radiation used by most algae for photosynthesis (from 400–700 nm) becomes attenuated in both intensity and width. Even in clear tropical waters, the irradiance levels below 120 m depth can be less than 1% of surface values, and the light spectrum is shifted toward the blue and blue–green wavelengths (~475 nm) (e.g. [4]). These light limitations pose a major constraint for the productivity of benthic organisms that rely on photosynthetic symbionts [6], including reef-building corals (scleractinians). While the scleractinian coral species Leptoseris hawaiiensis has been reported to occur as deep as 153 m in Hawaii and 165 m at Johnston atoll (reviewed in [4]), no live specimens were collected at these extreme depths. The fact that Symbiodiniaceae have been found at much greater depth in association with Antipatharians (396 m) [7], raises the possibility that they might also be present in scleractinian corals deeper than 165 m. Previous studies have genetically confirmed and identified endosymbiotic Symbiodiniaceae in Leptoseris down to 70 m on the Great Barrier Reef [8] and down to 125 m depth in Hawaii [9–11]. A specific host-Symbiodiniaceae association was reported between deep L. hawaiiensis and a Cladocopium from the ancestral C1 radiation [9–11], which represents a diverse group of Symbiodiniaceae commonly found in association with scleractinians on shallow coral reefs [8, 9, 12, 13]. To better understand how scleractinian corals can survive so far away from their presumed light optimum, it is critical to determine if these deep specimens (1) maintain their association with photosynthetic algae and/or (2) if their survival in the deepest mesophotic coral ecosystems requires a shift in their microbial communities, including Symbiodiniaceae and other microorganisms such as endolithic algae and bacteria.

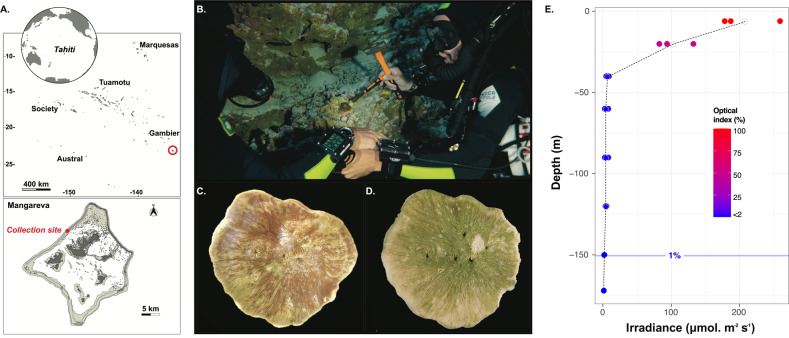

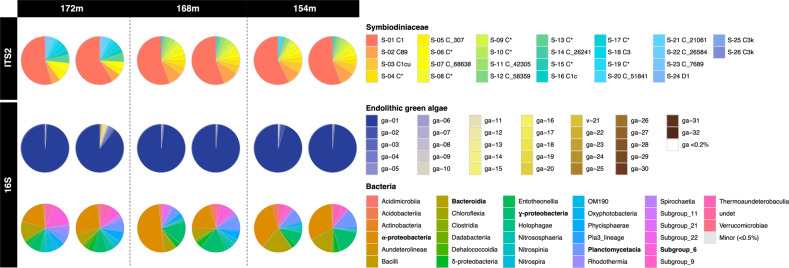

Here we report on the observation and collection of the deepest scleractinian corals in association with Symbiodiniaceae and other photosymbionts. Technical divers using closed-circuit rebreathers recovered three L. hawaiiensis colonies from the Gambier archipelago (French Polynesia, Fig. 1A) at 154, 168, and 172 m depth (n = 2 subsamples for each depth; Fig. 1B–D). Irradiance measured at 120 m depth was <2% of that recorded at 6 m depth and irradiance at 172 m was predicted to be <1% (Fig.1E and S1). ITS2 sequencing revealed Symbiodiniaceae presence in all three lower mesophotic colonies sampled, with nearly all of the retrieved amplicon sequence variants (ASVs; with most of these representing intragenomic sequence variants) classified as Cladocopium (Fig. 2). The most common ITS2 ASV representative sequence associated with these Leptoseris hosts (S-01, Fig. 2 and S2; 50–57% of total ASVs in each sample) was C1 (GeoSymbio and SymPortal databases; see supplementary methods). This represents one of the most common groups of Symbiodiniaceae, and it has previously been reported in Leptoseris [9, 10, 14], as well as other host species at depths ranging from the surface to 125 m [8, 10, 11, 13–15]. As a complementary approach, ITS2 profiles predicted by SymPortal were used as proxy for Symbiodiniaceae genotypes ([16]; see supplementary methods and data files S1–S4). These predicted ITS2 profiles were largely consistent among replicates but confirmed a different profile for the colony at 172 m depth compared to those at 154 and 168 m depth (Fig. S2). Nonetheless, the Symbiodiniaceae communities shared three ASVs that exactly matched C89 (S-02: 5% at 172 m vs. 17–19% at 154–168 m) and two different C variants (both S-05 and S-07: 7% at 172 m vs. ~2% at 154–168 m) in public databases (Fig. S3; GeoSymbio, SymPortal or Genbank). Of the 26 ASVs identified across all samples, one sequence originated from Durusdinium (S-24 D1 with GeoSymbio and SymPortal databases). This sequence is found in multiple heat-tolerant Durusdinium species including the enigmatic, cosmopolitan [17], host generalist D. trenchii [18]. However, whether or not the Symbiodiniaceae sampled here is D. trenchii or indeed thermally tolerant cannot be confirmed without further genetic and phenotypic data. Low abundance ASVs were observed at all three depths (172 m: 8 ASVs, 154 and 168 m: 10 ASVs, Fig. S3), including nine ASV sequences (Fig. 2) that have not been reported previously in the GeoSymbio [13] and SymPortal (access date: 2020-05-19_07-23-40) [16] databases (Fig. S3). Comparison of the overall Symbiodiniaceae SymPortal predicted ITS2 profiles (Fig. S2) did not confidently identify matches with previously encountered profiles (predominantly from shallow reef environments), indicating that they might be specific to this species and/or mesophotic environment. Given the extreme paucity of light at these depths, we hypothesize that lower mesophotic L. hawaiiensis may use different strategies to photoacclimate. Morphologically, the coral species were characterized by a thin flat skeleton (Fig. 1B–D), which is optimal for light harvesting and reducing skeletal carbonate deposition [19]. Leptoseris hawaiiensis has also been shown to display depth-associated physiological specialization and trophic plasticity (acquiring energy from different food sources) [9], and an unusual light-harvesting system, which enlarges the spectrum of wavelengths for photosynthesis by transforming the short, blue-shifted wavelength with their autofluorescent pigments [19].

Fig. 1. Sampling location of the deepest photosymbiotic scleractinian coral recorded to date.

A Map of the Gambier archipelago, French Polynesia. Pictures of Leptoseris hawaiiensis collected at 172 m depth in the Gambier archipelago (B) during the in situ sampling (screenshot of video © UTP III), (C) after reaching the surface and (D) after bleaching for taxonomic identification with the green color indicating the presence of endolithic algae. E Variation of the optical index of irradiance (in PAR) along the coral reef depth gradient from 6 to 120 m depth (predictions for 150 and 172 m depths) at Mangareva. For each depth, the three values represent a mean value for 3 days of measurements recorded every 5 min with a PAR logger (DEFI2-L Advantech) at three different time periods of the day (9 h30–10 h00, 12 h30–13 h00 and 15 h30–16 h00).

Fig. 2. Microbial communities harbored by the three deep colonies.

Composition of the microbial community in Leptoseris hawaiiensis collected at 172, 168, and 154 m. At each depth, two subsamples were analyzed for each colony. The ITS2 marker shows the relative proportion of different Symbiodiniaceae ASVs (with GeoSymbio and SymPortal v.2020-05-19_07-23-40 affiliations). The 16S rDNA marker shows the relative proportions of different ASVs for endolithic algae chloroplast composition and bacteria classes. Asterisk represents sequences with no exact match in the SymPortal database for Symbiodiniaceae.

To identify other microorganisms associated with our lower mesophotic scleractinian colonies, we targeted the 16S rRNA gene (V4–V5 region; see supplementary methods). Sequencing data revealed the presence of green algal chloroplast sequences belonging to the genus Ostreobium (Fig. 2). This endolithic alga was abundant in the deep coral colonies as suggested by the marked green color observed below the living tissues (Fig. 1C) and within the skeleton after removing the soft tissues in bleach (Fig. 1D). We identified a single Ostreobium species (ASV ga-01), belonging to clade 2, that was dominant in all the colonies (Fig. 2 and S4), and has been previously reported across the depth gradient in scleractinian corals and octocorals worldwide [20, 21]. The nature of the interaction between corals and Ostreobium has been debated. Evidence supports a mutualistic association under extreme conditions such as coral stress (inducing bleaching) [22] or drastically reduced light exposure [23]. Under the low light conditions of the deep mesophotic fore reef slope, Ostreobium might complement Symbiodiniaceae’s function by providing photosynthates to the host. These endolithic algae are adapted to photosynthesize in near-darkness with increased numbers of light-harvesting xanthophyll pigments that can use shorter wavelengths compared to other green algae and optimize light capture (e.g. [24]).

Bacteria associated with the lower mesophotic scleractinian colonies had an observed richness ranging from 106 to 211 ASVs per sample (Fig. S5). These bacteria mainly belonged to the classes Alpha- (19-49%) and Gamma-proteobacteria (8–17%), Bacteroidia (6–20%) and subgroup-6 of Acidobacteria (1–17%) (Fig. 2), which are known to associate with corals [25]. In total, we detected 843 different bacterial ASVs, among which 67–89% were unique to one colony or even unique to one subsample (Fig. S6 and Table S1). Our data suggest that the coral hosts displayed individual microbial signatures with some common ASVs shared between subsamples of the same colony (Fig. S6). However, this result might have been affected by the low-sequencing depth of the microbiome following the removal of the Ostreobium reads. Our results corroborate previous reports describing the high intra-specific variability of coral-associated bacterial communities at different spatial scales (e.g. [25, 26]), which might be driven by biological traits, such as the age [27] or diets of the colonies [28].

This study reports a new depth record for scleractinian corals associated with symbiotic algae at 172 m. Similar to conspecifics previously sampled in mesophotic environments between 115 and 125 m depth [10], the deepest L. hawaiiensis reported here associated with symbiotic-microalgae belonging to the highly diverse C1 lineage. The deep colonies were also characterized by the presence and abundance of a single species of endolithic alga from the genus Ostreobium (clade 2). These filamentous green algae adapted to thrive in extreme low light conditions [24] might highly contribute to the survival of L. hawaiiensis at depth through photosynthates translocation [29]. In addition, bacterial communities were diverse, with intraspecific differences in community composition. Our findings provide new insights into the symbioses of scleractinian corals at depth, through the conservation of their associated photosymbiotic algae, raising important questions about the nature and mechanisms involved in the interactions between host and Symbiodiniaceae and/or Ostreobium (e.g. evolutionary theory of symbiosis [30]). Future studies should establish the contribution of photosynthetic symbionts to the energy budget of mesophotic corals. Understanding the biology of ecosystem engineers, such as tropical reef corals, living at the edge of their habitat range is important to determine the plasticity of these organisms and their ability to withstand environmental pressure.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the divers of the Under The Pole (UTP) Team: GB, JL, GL who performed the extreme CCR deep dive to 172 m depth to collect the specimens for this study. In addition, we are grateful to all UTP III Expedition crew who greatly contributed to the success of the one-year-long mesophotic expedition. We also thank West N for assistance with the BIO2MAR platform. We acknowledge del Campo J for constructive discussions on Ostreobium phylogeny and sharing his updated 16S-sequences database. We are also grateful for constructive reviews from Hume B and one anonymous referee. This research was funded by the ANR DEEPHOPE (ANRAAPG 2017 #168722), the Délégation à la Recherche DEEPCORAL, the CNRS DEEPREEF and the IFRECOR. MM was supported by NSF OCE 1442206. The technical dives for coral sampling were funded through the Under The Pole Expedition III.

Under The Pole Consortium

G. Bardout9, E. Périé-Bardout9, E. Marivint9, G. Lagarrigue9, J. Leblond9, F. Gazzola9, S. Pujolle9, N. Mollon9, A. Mittau9, J. Fauchet9, N. Paulme9, R. Pete9, K. Peyrusse9, A. Ferucci9, A. Magnan9, M. Horlaville9, C. Breton9, M. Gouin9, T. Markocic9, I. Jubert9, P. Herrmann9.

Author contributions

All authors conceived and designed this study; LH and HR coordinated the study; HR, GP-R, MP, UTP III consortium and LH collected field data; MP identified coral species; HR carried out analysis and graphics and drafted the manuscript; HR, PG, MM, JBR, PB, and LH wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript and gave their approval to submit.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Members of the Under The Pole Consortium are listed below Acknowledgements.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Héloïse Rouzé, Email: heloise.rouze@gmail.com.

Under The Pole Consortium:

G. Bardout, E. Périé-Bardout, E. Marivint, G. Lagarrigue, J. Leblond, F. Gazzola, S. Pujolle, N. Mollon, A. Mittau, J. Fauchet, N. Paulme, R. Pete, K. Peyrusse, A. Ferucci, A. Magnan, M. Horlaville, C. Breton, M. Gouin, T. Markocic, I. Jubert, and P. Herrmann

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41396-020-00857-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Blackall LL, Wilson B, Van Oppen MJH. Coral—the world’s most diverse symbiotic ecosystem. Mol Ecol. 2015;24:5330–5347. doi: 10.1111/mec.13400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pearse V, Muscatine L. Role of symbiotic algae (zooxanthellae) in coral calcification. Biol Bull. 1971;141:350–363. doi: 10.2307/1540123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muscatine L, Porter JW. Reef corals: mutualistic symbioses adapted to nutrient-poor environments. Bioscience. 1977;27:454–460. doi: 10.2307/1297526. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahng SE, Garcia-Sais JR, Spalding HL, Brokovich E, Wagner D, Weil E, et al. Community ecology of mesophotic coral reef ecosystems. Coral Reefs. 2010;29:255–275. doi: 10.1007/s00338-010-0593-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maragos JE, Jokiel PL. Reef corals of Johnston Atoll: one of the world’s most isolated reefs. Coral Reefs. 1986;4:141–150. doi: 10.1007/BF00427935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gattuso JP, Gentili B, Duarte CM, Kleypas JA, Middelburg JJ, Antoine D. Light availability in the coastal ocean: Impact on the distribution of benthic photosynthetic organisms and their contribution to primary production. Biogeosciences. 2006;3:489–513. doi: 10.5194/bg-3-489-2006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagner D, Pochon X, Irwin L, Toonen RJ, Gates RD. Azooxanthellate? Most Hawaiian black corals contain Symbiodinium. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2011;278:1323–1328. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bongaerts P, Sampayo EM, Bridge TCL, Ridgway T, Vermeulen F, Englebert N, et al. Symbiodinium diversity in mesophotic coral communities on the Great Barrier Reef: a first assessment. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2011;439:117–126. doi: 10.3354/meps09315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Padilla-Gamiño JL, Roth MS, Rodrigues LJ, Bradley CJ, Bidigare RR, Gates RD, et al. Ecophysiology of mesophotic reef-building corals in Hawai’i is influenced by symbiont–host associations, photoacclimatization, trophic plasticity, and adaptation. Limnol Oceanogr. 2019;64:1980–1995. doi: 10.1002/lno.11164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pochon X, Forsman Z, Spalding H, Padilla-Gamiño J, Smith C, Gates R. Depth specialization in mesophotic corals (Leptoseris spp.) and associated algal symbionts in Hawaii. R Soc Open Sci. 2015;2:140351. doi: 10.1098/rsos.140351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan YL, Pochon X, Fisher MA, Wagner D, Concepcion GT, Kahng SE, et al. Generalist dinoflagellate endosymbionts and host genotype diversity detected from mesophotic (67–100 m depths) coral Leptoseris. BMC Ecol. 2009;9:21. doi: 10.1186/1472-6785-9-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thornhill DJ, Lewis AM, Wham DC, Lajeunesse TC. Host-specialist lineages dominate the adaptive radiation of reef coral endosymbionts. Evolution. 2014;68:352–367. doi: 10.1111/evo.12270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franklin EC, Stat M, Pochon X, Putnam HM, Gates RD. GeoSymbio: a hybrid, cloud-based web application of global geospatial bioinformatics and ecoinformatics for Symbiodinium-host symbioses. Mol Ecol Resour. 2012;12:369–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2011.03081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ziegler M, Roder CM, Büchel C, Voolstra CR. Mesophotic coral depth acclimatization is a function of host-specific symbiont physiology. Front Mar Sci. 2015;2:4. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2015.00004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Polinski JM, Voss JD. Evidence of photoacclimatization at mesophotic depths in the coral-Symbiodinium symbiosis at Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary and McGrail Bank. Coral Reefs. 2018;37:779–789. doi: 10.1007/s00338-018-1701-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hume BCC, Smith EG, Ziegler M, Warrington HJM, Burt JA, LaJeunesse TC, et al. SymPortal: a novel analytical framework and platform for coral algal symbiont next-generation sequencing ITS2 profiling. Mol Ecol Resour. 2019;19:1063–1080. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.13004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pettay D, Wham D, Smith R, Iglesias-Prieto R, LaJeunesse T. Microbial invasion of the Caribbean by an Indo-Pacific coral zooxanthella. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:1–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502283112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LaJeunesse TC, Wham DC, Pettay DT, Parkinson JE, Keshavmurthy S, Chen CA. Ecologically differentiated stress-tolerant endosymbionts in the dinoflagellate genus Symbiodinium (Dinophyceae) clade D are different species. Phycologia. 2014;53:305–319. doi: 10.2216/13-186.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fricke H, Vareschi E, Schlichter D. Photoecology of the coral Leptoseris fragilis in the Red Sea twilight zone (an experimental study by submersible) Oecologia. 1987;73:371–381. doi: 10.1007/BF00385253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonzalez-Zapata FL, Gómez-Osorio S, Sánchez JA. Conspicuous endolithic algal associations in a mesophotic reef-building coral. Coral Reefs. 2018;37:705–709. doi: 10.1007/s00338-018-1695-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Del Campo J, Pombert JF, Šlapeta J, Larkum A, Keeling PJ. The ‘other’ coral symbiont: Ostreobium diversity and distribution. ISME J. 2017;11:296–299. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fine M, Loya Y. Endolithic algae: an alternative source of photoassimilates during coral bleaching. Proc R Soc B. 2002;269:1205–1210. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halldal P. Photosynthetic capacities and photosynthetic action spectra of endozoic algae of the massive coral Favia. Biol Bull. 1968;134:411–424. doi: 10.2307/1539860. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fork D, Larkum A. Light harvesting in the green alga Ostreobiumsp., a coral symbiont adapted to extreme shade. Mar Biol. 1989;103:381–385. doi: 10.1007/BF00397273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hernandez-Agreda A, Gates RD, Ainsworth TD. Defining the core microbiome in corals’ microbial soup. Trends Microbiol. 2017;25:125–140. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rohwer F, Seguritan V, Azam F, Knowlton N. Diversity and distribution of coral-associated bacteria. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2002;243:1–10. doi: 10.3354/meps243001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams AD, Brown BE, Putchim L, Sweet MJ. Age-related shifts in bacterial diversity in a reef coral. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galand PE, Remize M, Meistertzheim AL, Pruski AM, Peru E, Suhrhoff TJ, et al. Diet shapes cold-water corals bacterial communities. Environ Microbiol. 2020;22:354–368. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schlichter D, Zscharnack B, Krisch H. Transfer of photoassimilates from endolithic algae to coral tissue. Naturwissenschaften. 1995;82:561–564. doi: 10.1007/BF01140246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lesser MP, Stat M, Gates RD. The endosymbiotic dinoflagellates (Symbiodinium sp.) of corals are parasites and mutualists. Coral Reefs. 2013;32:603–611. doi: 10.1007/s00338-013-1051-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.