Abstract

Aim: This is a cross-national study with the aim to explore the development of children with autism over time in the UK and Greece. The focus of the study was to investigate the differences in language and social skills between children with autism across the two countries who were receiving different types of treatment: speech and language therapy, psychoanalytic/psychodynamic psychotherapy, and occupational therapy.

Study design: A cross-national longitudinal design with a mixed (between-subjects and within-subjects) design.

Participants: A sample of 40 children in total. In the UK, 20 children with autism who had received psychotherapy (n = 10) and speech and language therapy (n = 10) were recruited and monitored post-therapy twice over a two-year period. In Greece, 20 children with autism who received occupational therapy (n = 10) and speech and language therapy (n = 10) were recruited and monitored post-therapy twice over a two-year period.

Results: All children changed significantly over time on all aspects of measurement, demonstrating that children with autism are developing in a very similar way across the two countries. With respect to the effect of the therapy context on the development of children with autism, it was found that there were no differences across intervention contexts at the start of the study, and there were mainly nonsignificant interactions in the rate of change across the differing types of intervention. However, further analysis showed some important differences: speech and language therapy participants presented more widespread change on language scores across the measures; psychotherapy participants showed significant greater increase in imagination and decrease in stereotypical behavior; and occupational therapy participants presented significant reduction of stereotypical behavior.

Conclusions: This study can help professionals who work with children with autism further their understanding of the disorder and how it manifests through time in order to provide appropriate services based on each child’s needs.

Keywords: Childhood autism, speech and language therapy, psychotherapy, occupational therapy, UK, Greece

Introduction

Autism is a neurodevelopmental disorder that affects the quality of relationships, communication and language skills as well as emotional and imaginative development (Waterhouse 2013). According to the National Autistic Society (2010) autism is a lifelong developmental disability. The current diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) include deficits in social communication and interactions, and restricted interests or repetitive behaviors (DSM-5, APA, 2013).

Autism was once thought of as a rare condition (Kanner 1943; DSM-III-R, 1987). According to the most recent ‘Centres for Disease Control and Prevention’ report (Baio 2014) the prevalence of autism (for the period of 2010) is 1 in every 68 births in the United States and almost 1 in 54 boys. Research by Baird et al. (2006) suggests that one in 100 people in the UK has autism and records show that there is an increase in children being diagnosed with autism (Gillberg and Wing 1999; Webb et al. 1997; Wing et al. 1997). Research also shows that the concept of autism is similar, regardless of cultural background or country of study (Gonela 2006). Papageorgiou (2005) suggested cross-cultural similarities of the Restricted and Repetitive Behaviors and Interests domain of autism but there are some studies (Baron-Cohen et al. 2001; Mandy et al. 2014) suggesting that ASD manifests differently across countries and thus there may be some cultural divergence in the presentation of ASD. Nevertheless, in general the prevalence and nature of autism across countries has received limited attention and this perspective is the main focus of the present study. There is also a growing need to consider the role of intervention services in meeting the needs of children with autism and their families and calls for more research to taking into account any differences across types of treatment experience in terms of children’s social, communication and cognitive skills.

There is a great variety of therapeutic approaches, which focus on accommodating or remediating different challenges related to autism. Siegel (1999, p.34) recommends taking a ‘kind of systematic eclecticism’ to creating treatment programs for individuals. This means that various treatment models can be combined and be used throughout the process depending on the child’s progressing needs, strengths and weaknesses.

Following the diagnosis of autism and around the time that parents start to come to terms with their child’s condition, they have to decide what kind of treatment plan they are going to follow. There are various approaches and interventions available and it can be confusing for parents to decide which is the best path to follow due to the variability of treatments offered, and the lack of information about differences across therapies. Children with autism are considered to be very different from each other and the clinical presentation of their symptoms varies along with the outcomes following an intervention (Ben-Itzchak et al. 2014). There are many different treatments provided to children with autism, which are supported by empirical evidence (e.g. Baker-Ericzen et al. 2007; Case-Smith and Bryan 1999; Francke and Geist 2003; Kasari et al. 2006; Linderman and Stewart 1999; Smith et al. 2010; Watling and Dietz 2007). However, studies to date have not considered differences in development between children undertaking different types of therapy. A secondary focus of this study was to explore the progress in children with autism undertaking three different types of treatment: speech and language therapy, psychodynamic psychotherapy, and occupational therapy to investigate whether any differences were evident, especially in areas of development associated with those particular therapies. It should be noted, however, that this aspect of the design was intended to explore intervention context and is not a treatment trial in the traditional sense.

Existing research suggests that speech and language therapy is one of the most commonly used treatments for children with ASD internationally (Green et al. 2006), including in both Greece and the UK (Batten et al. 2006; Stampoltzis et al. 2012). Indeed, speech and language therapy is reported to be the most common treatment for the majority of children across Europe (Salomone et al. 2016). Different speech and language therapy approaches have been developed to promote the communication skills of children with autism. For example, the Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS), a visually based communication system, has been used extensively in children with ASDs and an average effect of PECS has been demonstrated throughout the literature for advancing the communication skills of children with autism (Gordon et al. 2011; Schreibman and Stahmer 2014; Sulzer-Azaroff et al. 2009).

Psychodynamic/psychoanalytic treatment is also sometimes used in the UK for children with autism (Alvarez et al. 1999; Pozzi 2003; Reid et al. 2001) although its efficacy as a treatment has long been questioned (Alvarez 1996; Midgley and Kennedy 2011; Roser 1996). There is no published evidence or information about whether this type of therapy is used in Greece. However, there remains a paucity of rigorous research on the outcomes of a psychodynamically based approach to support children with autism, with the majority of studies being small case studies (Alvarez and Lee 2004; Bromfield 2000; Gould 2011; Hoffman and Rice 2012; Sherkow 2011). The conclusions drawn from these studies suggest that this approach can facilitate positive changes in the development of children with autism, but due to the case study design, and often poor quality outcome measures the ability to generalize this evidence to a wider population is extremely limited. Muratori et al. (2005) highlight the fact that knowledge in the field of psychotherapy is not progressing as much compared to evidence of psychiatric and neurobiological therapies. Furthermore, Muratori et al. (2005) suggest that no serious attempt to study the role of psychotherapy in supporting childhood autism has been carried out.

According to Green et al. (2006), occupational therapy is among the most frequently requested services by parents of children with autism and it is a treatment widely used in Greece (Stampoltzis et al. 2012) but perhaps less so in the UK. Sensory processing difficulties co-occur with other ASD symptoms in more than 80% children (Ben-Sasson et al. 2009). Studies suggest that sensory integration therapy for children with autism can be effective, with strong evidence from a small number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of a positive impact on the overall development of children receiving this type of therapy (Fazlioglu and Baran 2008; Iwanaga et al. 2014; Schaaf et al. 2013). Despite this, a study by Lang et al. (2012) concluded that there is still not enough evidence to support the widespread use of sensory integration therapy. This conclusion is also in line with the findings of a more recent review of sensory processing interventions of children with autism by Case-Smith et al. (2015).

To the authors’ knowledge, there has been no previous cross-national research studies comparing the development of children with autism over time, or that take into account different types of treatment context in two different countries.

The aims of this study were therefore:

To determine whether aspects of childhood autism differ in the UK and Greece.

To investigate the association between therapy context (speech and language therapy, psychoanalytic/psychodynamic psychotherapy, and occupational therapy) and the patterns of developmental change.

Methods

Design

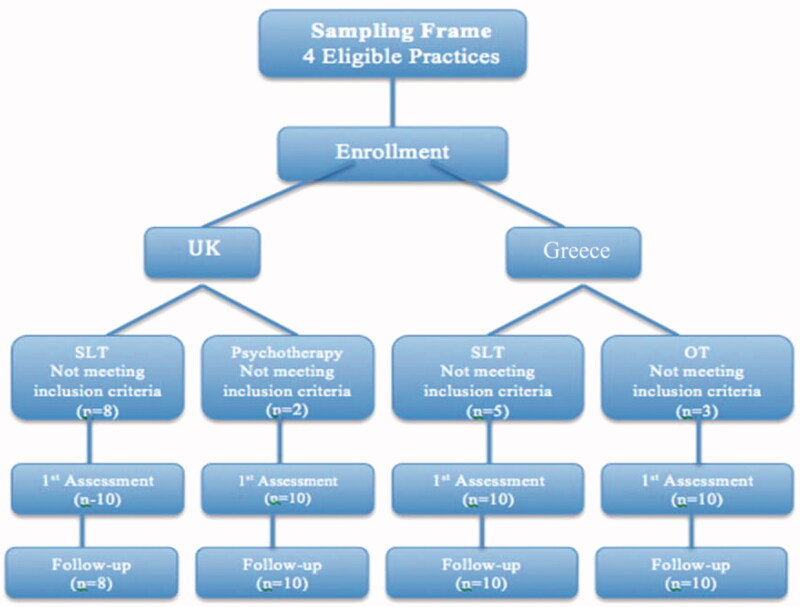

This study has a cross-national longitudinal design (Figure 1) using both between-subjects and within-subjects analysis. The aim of this study was to compare the short term development of two groups of autistic children—Greek and English. The differences in language and social skills development between autistic children were examined across countries in the context of therapeutic experience. To our knowledge there are very few cross-cultural studies, or longitudinal studies past early-years development (e.g. Anderson et al. 2011; Woodman et al. 2015) and the studies that do exist have not taken into consideration the primary intervention context of the children. It should be acknowledged that this study cannot be treated as an intervention study, which would require pre–post measures, random allocation, and intervention fidelity. The present study was also observational and was not intended to be a therapeutic trial. Instead, it was considered important to include the therapy context to investigate any differences occurring between these groups, and to then tentatively discuss the possible reasons for these.

Figure 1.

Study process.

Participant recruitment

The participants were recruited through referrals from three private independent clinics: a private center in Greece that provided both speech and language therapy and occupational therapy; a private psychotherapeutic center in London; and a private speech and language therapy practice in London. The therapists from the three clinics sent out an information letter to the families of children who had recently finished attending their practice to invite them to participate in the research. Some invited participants did not meet the eligibility criteria (see ‘Participant characteristics’ section) and 18 children were excluded: In Greece, 5 children from speech and language therapy (SLT; low nonverbal IQ, n = 4; additional visual impairment, n = 1) and 3 from occupational therapy (OT; no autism diagnosis); in the UK, 8 from SLT (low nonverbal IQ, n = 6; did not meet native language criteria, n = 1; additional epilepsy, n = 1) and 2 from psychotherapy in the UK (did not meet the age criteria). Figure 1 outlines the flow of participants through the study.

Participant characteristics

A total of 40 children were recruited to the study, 20 from Greece and 20 from the UK, aged between 2 and 9 years of age (mean age = 67.9 months; SD = 0.8). There were 36 boys and 4 girls. The UK based children were selected after having completed one of the two types of treatment examined (psychotherapy, n = 10 and speech and language therapy, n = 10). A total of twenty children residing in Greece that had received one of the two treatments examined were also recruited (occupational therapy, n = 10 and speech and language therapy, n = 10). Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of each group of children. This sample size is similar or greater to other studies in this field of research (Charlop-Christy et al. 2002; Hayward et al. 2009; Iwanaga et al. 2014; Moore and Goodson 2003; Sherkow 2011; Vorgraft et al. 2007). The children were monitored approximately 12 months after initial testing on a number of language and social measures (see ‘Assessment measures’ section). Thus they were measured twice in total, with a mean time between assessments of 12.8 months (SD = 1.4).

Table 1.

Participant age and gender characteristics at time 1 by country and intervention context.

| UK |

Greece |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Speech and language therapy | Psychotherapy | Occupational therapy | Speech and language therapy |

| n = 10 | n = 10 | n = 10 | n = 10 |

| 9 male/1 female | 8 male/2 female | 10 male/0 female | 9 male/1 female |

| Mean age = 76.60 months | Mean age = 60.5 months | Mean age = 59.30 months | Mean age = 68.50 months |

| Min = 37 months/max = 108 months | Min = 30 months/max = 102 months | Min = 42 months/max = 76 months | Min = 45 months/max = 98 months |

| (SD = 24.6) | (SD = 27.7) | (SD = 18.0) | (SD = 16.1) |

Therapists in both countries at the clinics participating in the study were asked to identify children who met the following criteria:

diagnosis of autism or autistic symptoms before being involved in any kind of treatment aged from 2.5 to 10 years;

nonverbal cognitive abilities in the normal range (not below an IQ of 70); and

either monolingual or bilingual but with substantial experience (at least 5 years immersion) of English. Also, the therapists in both countries were asked to exclude children:

with concomitant deafness, epilepsy or visual impairment;

receiving another one of the treatments examined intensively; and

receiving medication.

The groups were not significantly different on age (F(3,37) = 1.084, p = 0.36), gender (χ2(3) = 2.165, p = 0.58) or on severity of autism symptoms using the ADOS (χ2(3) = 3.643, p = 0.30). Table 1 shows a breakdown of the numbers in each group at time point one and Table 2 shows a breakdown of the numbers in each group at time point two. At time 2, nearly all of the children participated (38/40), and at this phase the group as a whole had a mean age of 76.8 months (SD = 7.2).

Table 2.

Participant age and gender characteristics at time 2 by country and intervention context.

| UK |

Greece |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Speech and language therapy | Psychotherapy | Occupational therapy | Speech and language therapy |

| n = 8 | n = 10 | n = 10 | n = 10 |

| 7 male/1 female | 8 male/2 female | 10 male/0 female | 9 male/1 female |

| Mean age =85.87 months | Mean age =71.4 months | Mean age =70.6 months | Mean age =79.7 months |

| Min =49 months/max = 119 months | Min =42 months/max = 112 months | Min =53 months/max = 88 months | Min =56 months/max = 110 months |

| (SD =23.6) | (SD =27.58) | (SD =17.28) | (SD =16.8) |

Assessment measures

We selected measures which would comprehensively assess childhood autism and also had previously been used in both the UK and Greece. Specifically, we chose measures that addressed language skill, social communication, restricted interests and general cognitive functioning as these are all areas which have been highlighted in the literature as potential areas of interest in children with autism (Baghdadli et al. 2006; Szatmari et al. 2015).

The following measures were employed.

Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS)

The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule is a semi-structured standardized observation of the child that measures autism symptoms in the following scales: social relatedness, communication, play (imagination), and repetitive/stereotypic behaviors (Lord et al. 2000). Various play situations are facilitated aiming to allow observation of a range of imaginative activities and social-role play (Lord et al. 2000). Another aim of the ADOS is to provide presses that draw out spontaneous behaviors. The schedule consists of four modules and each one is appropriate for children and adults at different developmental and language levels. Each module lasts about 30–45 min and only one is administered to each individual, based on the individual’s developmental and language levels. ADOS items are typically scored on a 3-point scale from 0 (no evidence of abnormality related to autism) to 2 (definite evidence). Some of the items include a code of 3 suggesting severe abnormalities that might interfere with the observation. Throughout the analyses, scores of 3 are converted to 2. Moreover, the scores are compared with an algorithm cut-off score for autism or more broadly defined ASD (Lord et al. 2000). The ADOS was not used as a diagnostic measure but as a tool to assess symptoms.

Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ)

This is a 40-item binary scaled screening instrument for autism to be completed by parents (Rutter et al. 2003). It is a questionnaire checklist that asks parents to rate their children’s behavior in relation to social communication. For example: ‘Has her/his facial expression usually seemed appropriate to the particular situation, as far as you could tell?’, ‘Has he/she ever seemed to be unusually interested in the sight, feel, sound, taste or smell of things or people?’. In nonverbal children 6 items are left out. The points are summed (yes = 1; no = 0) and the cut-off is established as ≥22 for autism and ≥15 for ASD (Oosterling et al. 2010). The SCQ is broadly used to screen for ASDs and has established comparative validity against the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R; Lord et al. 1994).

Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices (RCPM)

This is a child-based measure of nonverbal cognitive ability often used in studies of children with language impairment due to its easy and quick administration, lack of timed tasks, and nonverbal nature (Raven et al. 2003). The RCPM include a series of diagrams or designs with a part missing. Each individual is supposed to choose the correct part to complete the designs among a variety of options printed beneath (Raven et al. 2003). The test consists of 36 matrices divided equally into three sets (A, AB, B). In each matrix, there are six choices. The correct answer is given one score and the wrong is given zero, which means that the raw score on the test ranges between 0 and 36. Ravens Matrices have been used broadly in various settings across countries as a measure of nonverbal intelligence (Kazem et al. 2009). Reliability data was presented in the 1986 Raven manual showing adequate reliability for research purposes and validity evidence extends primarily from correlational studies with other tests (Kamphaus 2005). The test is not timed and standard IQ scores are calculated. Children younger than 5 years of age (n = 5) did not complete this measure.

Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals (CELF IV)

The CELF is a standardized language assessment (Semel et al. 2003). It provides a flexible, multiperspective assessment process for pin-pointing a child’s language and communication strengths and weaknesses. Two subtests were used: Concepts and Following Directions (C&FD) and Formulating Sentences (FS-production). In the Concepts and Following Directions the child points to pictured objects in a particular order in response to oral directions. In the Formulated Sentences the child formulates a sentence about a picture using a targeted word or phrase. Both subtests produce a scaled score. The CELF has showed high correlation rating with similar instruments and its validity has been established through factor analyses, review of literature and analyses of response process (Semel et al. 2003).

Children younger than 5 years of age (n = 5) did not complete this measure.

British Picture Vocabulary Scale II (BPVS II)

This is a child-based measure, which is used as a test of word knowledge or vocabulary comprehension and is brief and easy to administer (Dunn et al. 1997). The child is shown four pictures and needs to point to the picture that represents the word spoken by the researcher. The child being tested needs only to point to a picture and does not have to be able to read, write or speak. It is a test of receptive vocabulary and it is administered individually and provides norm-referenced scores. Raw scores are converted into an age equivalent score in years and months. Also, the scale has good reliability and validity (Glenn and Cunningham 2005).

Procedure

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the School of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee at City University of London. All parents were given a Participant Information Sheet and asked to sign a Participant Consent Form prior to the assessments. The procedures were also explained verbally to the children, in an easy to understand language, and they were given the opportunity to decline the testing at any point. However, they were all willing to cooperate.

Following informed written consent from 40 parents of eligible children, the assessment visits were scheduled. To confirm the stated context of the intervention services, the therapists in both countries were asked to complete a questionnaire regarding their practice.

All measures were completed either by the parents (in the case of questionnaires) or via direct testing with the children by the lead researcher (KP). Nonstandardized Greek versions of all the tests were used for the Greek sample, since the stimuli were mainly single word level and culturally appropriate, and were translated by the first author (a bilingual English-Greek speaker) in discussion with advice from researchers experienced in using nonstandardized Greek versions of the CELF and BPVS (Taxitari et al. 2015; Stavrakaki and Van der Lely 2010). We acknowledge though that an instrument developed and validated on one population does not automatically retain validity in another context or language. Ideally, instruments would have been validated on a Greek sample prior to use, however this was not possible within the scope of this study.

The children from all the different therapy groups were assessed individually in a room in the center where they had therapy and their parents completed the relevant questionnaires in the same room after their children completed the tests. The testing was conducted over two sessions that lasted about an hour each time. During the first session, the ADOS and the SCQ were completed and at the second visit the rest of the tests were administered.

Analysis

For the initial analysis, we compared cross-national development. To do this we held the therapy type constant and only analyzed children receiving SLT in the two countries. Next we analyzed all four groups of children over time to examine the effect of country and intervention context on development in a number of areas. Because of the wide age spread, mixed group × time ANCOVAs were used for both sets of analyses.

Results

The descriptive details of the time 1 and time 2 data by country and therapy type are presented in Table 3. There were no significant differences between groups on any variable at baseline (all p values >0.25). Initially, we compared the progress of children receiving SLT across the UK and Greece to explore cross-cultural differences whilst controlling for therapy type. Second, we analyzed all four therapy groups, to explore whether differences in progress could be identified.

Table 3a.

Mean and SD of scores for participants in Greece at time 1 and time 2.

| Time 1 | SCQ1 | ADOS-Com1 | ADOS-Soc1 | ADOS-Imag1 | ADOS-Ster1 | C&FD1 | FS1 | BPVS1 | Ravens1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLT | 10.80 (SD = 3.39) | 4.00 (SD = 1.33) | 4.70 (SD = 2.21) | 1.20 (SD = .63) | 3.10 (SD = 1.20) | 20.90 (SD = 12.85) | 12.30 (SD = 9.58) | 44.80 (SD = 20.33) | 10.80 (SD = 6.30) |

| OT | 13.5 (SD = 7.40) | 5.20 (SD = 2.04) | 6.40 (SD = 3.89) | 1.50 (SD = 1.35) | 3.70 (SD = 1.90) | 12.70 (SD = 8.69) | 7.40 (SD = 7.76) | 37.00 (SD = 23.92) | 9.70 (SD = 9.27) |

| Time 2 | SCQ2 | ADOS-Com2 | ADOS-Soc2 | ADOS-Imag2 | ADOS-Ster2 | C&FD2 | FS2 | BPVS2 | Ravens2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLT | 11.30 (SD = 4.16) | 3.20 (SD = .789) | 4.00 (SD = 1.94) | 1.00 (SD = .667) | 2.80 (SD = 1.22) | 26.60 (SD = 14.60) | 14.40 (SD = 10.42) | 56.70 (SD = 19.48) | 13.80 (SD = 6.12) |

| OT | 11.60 (SD = 6.25) | 4.70 (SD = 2.71) | 5.60 (SD = 3.62) | 1.40 (SD = 1.43) | 3.00 (SD = 2.00) | 18.80 (SD = 12.56) | 10.50 (SD = 10.27) | 46.10 (SD = 26.66) | 13.80 (SD = 10.22) |

Table 3b.

Mean and SD of scores for participants in UK at time 1 and time 2.

| Time 1 | SCQ1 | ADOS-Com1 | ADOS-Soc1 | ADOS-Imag1 | ADOS-Ster1 | C&FD1 | FS1 | BPVS1 | Raven1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSYCH | 13.40 (SD = 8.05) | 5.90 (SD = 3.57) | 7.30 (SD = 3.95) | 1.60 (SD = 1.27) | 3.40 (SD = 1.96) | 13.50 (SD = 18.24) | 10.20 (SD = 15.36) | 41.00 (SD = 30.17) | 11.70 (SD = 11.33) |

| SLT | 13.63 (SD = 4.90) | 5.88 (SD = 1.89) | 7.38 (SD = 3.34) | 2.25 (SD = 1.17) | 2.63 (SD = 2.00) | 15.88 (SD = 9.78) | 6.50 (SD = 8.94) | 39.50 (SD = 22.86) | 11.88 (SD = 8.17) |

| Time 2 | SCQ2 | ADOS-Com2 | ADOS-Soc2 | ADOS-Imag2 | ADOS-Ster2 | C&FD2 | FS2 | BPVS2 | Raven2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSYCH | 11.80 (SD = 7.18) | 4.80 (SD = 35.2) | 5.70 (SD = 3.06) | 0.70 (SD = 0.68) | 2.30 (SD = 1.70) | 17.80 (SD = 18.67) | 13.70 (SD = 17.28) | 49.60 (SD = 31.28) | 14.60 (SD = 13.14) |

| SLT | 10.50 (SD = 3.82) | 4.13 (SD = 1.13) | 5.50 (SD = 3.02) | 1.75 (SD = 0.71) | 2.13 (SD = 1.64) | 22.50 (SD = 8.86) | 11.50 (SD = 11.36) | 55.00 (SD = 20.29) | 18.13 (SD = 8.10) |

SCQ: Social Communication Questionnaire; ADOS-Com: Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Communication; Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Social Relatedness; ADOS-Imag: Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Imagination; ADOS-Ster: Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Repetitive/Stereotypic Behaviors; C&FD: Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-Concepts and Following Directions; FS: Concepts and Following Directions-Formulating Sentences; BPVS: British Picture Vocabulary Scale II; Raven: Raven’s Coloured Progressive Matrices.

Comparison of Greek children and English children receiving SLT after adjusting for age

Mixed 2 (country of SLT group) × 2 (time) ANCOVAs were completed on the various outcome measures. Based on the results, for five of the assessments, the ADOS-Social, the ADOS-Imagination, the ADOS-Stereotypical, the Concepts and Following Directions (CELF) and the Formulated Sentences (CELF) the change over time stopped being significant when age at recruitment was considered suggesting that for these skills the age of the child makes a difference to rate of development. Overall it can be seen in Table 4 that children with autism who received SLT are developing in a very similar way across the two countries. Only the ADOS-Social and the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) showed a significant interaction effect. Examination of the data showed that the SLT group from the UK seems to improve faster in the area of social skills compared to the SLT group from Greece. There were also main effects of group for ADOS-Communication scale and for the ADOS-Imagination scale. The children from the SLT group from Greece had lower scores in both assessment measures. All descriptive data can be seen in Table 3.

Table 4.

Statistical results from time × country ANCOVAs (adjusting for age).

| Measure | Time | Group | Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Communication Questionnaire | F(1,15) = 0.362, p = 0.556 | F(1,15) = 0.613, p = 0.446 | F(1,15) = 6.137, p = 0.020, = 0.290 |

| ADOS-Communication | F(1,15) = 4.092, p = 0.061 | F(1,15) = 9.728, p = 0.007 | F(1,15) = 3.447, p = 0.083 |

| ADOS-Social | F(1,15) = 0.024, p = 0.880 | F(1,15) = 3.208, p = 0.093 | F(1,15) = 5.493, p = 0.033, = 0.268 |

| ADOS-Imagination | F(1,15) = 0.749, p = 0.400 | F(1,15) = 6.269, p = 0.024 | F(1,15) = 1.137, p = 0.303 |

| ADOS-Stereotypical behavior | F(1,15) = 0.003, p = 0.957 | F(1,15) = 0.528, p = 0.479 | F(1,15) = 0.178, p = 0.679 |

| Concepts and Following Directions (CELF) | F(1,15) = 1.484, p = 0.242 | F(1,15) = 2.656, p = 0.124 | F(1,15) = 0.155, p = 0.700 |

| Formulated Sentences (CELF) | F(1,15) = 0.071, p = 0.793 | F(1,15) = 3.498, p = 0.081 | F(1,15) = 1.127, p = 0.305 |

| British Picture Vocabulary Scale II | F(1,15) = 5.452, p = 0.034 | F(1,15) = 1.550, p = 0.232 | F(1,15) = 0.973, p = 0.340 |

| Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices | F(1,15) = 9.010, p = 0.009 | F(1,15) = 0.193, p = 0.667 | F(1,15) = 3.481, p = 0.082 |

The effect of country and intervention context on development over time after adjusting for age

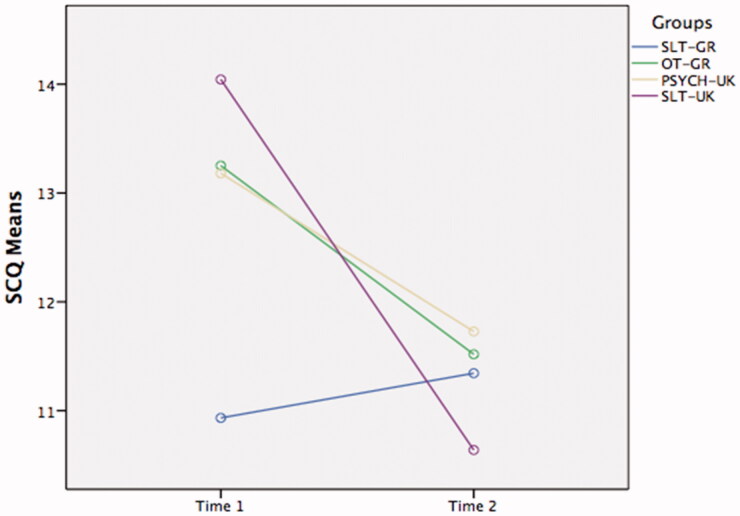

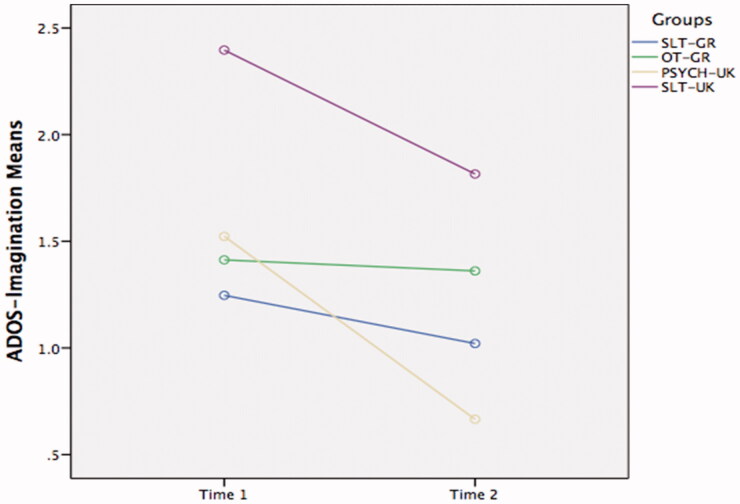

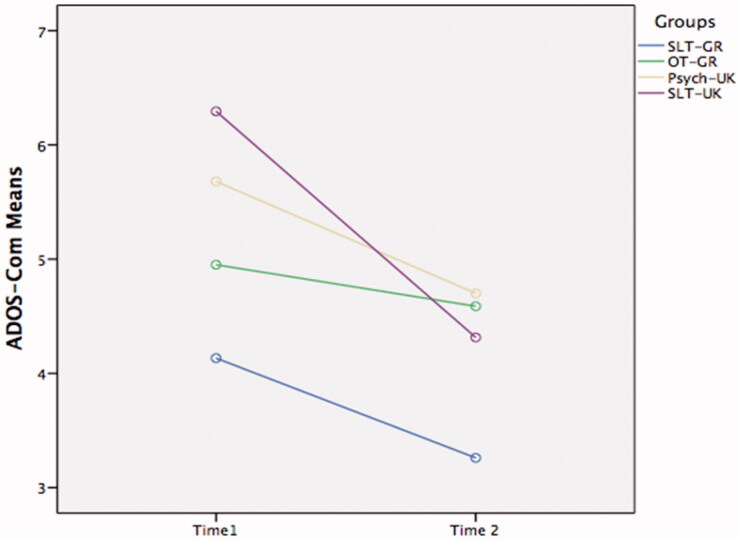

A series of 4 × 2 (group × time) ANCOVAs were performed to identify whether intervention context was associated with change over time. See Table 5 for means and SDs. The four groups were those identified in methods—SLT in UK; psychotherapy in UK; SLT in Greece; and OT in Greece. All measures showed change over time except for the ADOS-Social, the Concepts and Following Directions (CELF), the Formulated Sentences (CELF), and the Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices and none showed a main effect of group. Overall therefore, children with autism are developing in a very similar way across all groups. However, the SCQ (Figure 2), the ADOS-Imagination (Figure 3), and the ADOS-Communication (Figure 4) showed a significant interaction effect (see details in Table 5). The SLT group in the UK seemed to improve faster in the social communication area than other groups; the psychotherapy group in the UK improved faster in the area of imagination and Figure 4 suggests that the OT group in Greece showed the slowest improvement in the area of communication. All descriptive data can be seen in Table 3. Although the overall interaction for stereotypical behavior was not significant, it may be worth noting that only the groups receiving OT (t(9) = 2.689, p = 0.025) and psychotherapy (t(9) = 3.161, p = 0.012) made significant improvement in this area.

Table 5.

Statistical results from time × group ANCOVAs (adjusting for age).

| Measure | Time | Group | Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Communication Questionnaire | F(3,33) = 5.775, p = 0.022 | F(3,33) = 0.112, p = 0.953 | F(3,33) = 3.280, p = 0.033, = 0.230 |

| ADOS-Communication | F(3,33) = 20.049, p < 0.001 | F(3,33) = 1.017, p = 0.398 | F(3,33) = 3.400, p = 0.029, = 0.236 |

| ADOS-Social | F(3,33) = 3.641, p = 0.065 | F(3,33) = 0.945, p = 0.430 | F(3,33) = 2.251, p = 0.101 |

| ADOS-Imagination | F(3,33) = 8.313, p = 0.007 | F(3,33) = 1.862, p = 0.155 | F(3,33) = 3.432, p = 0.028, = 0.238 |

| ADOS-Stereotypical behavior | F(3,33) = 6.213, p = 0.018 | F(3,33) = 0.435, p = 0.730 | F(3,33) = 1.122, p = 0.354 |

| Concepts and Following Directions (CELF) | F(3,33) = 3.957, p = 0.055 | F(3,33) = 1.012, p = 0.400 | F(3,33) = 0.465, p = 0.709 |

| Formulated Sentences (CELF) | F(3,33) = 0.240, p = 0.627 | F(3,33) = 1.676, p = 0.191 | F(3,33) = 0.249, p = 0.861 |

| British Picture Vocabulary Scale II | F(3,33) = 11.578, p = 0.002 | F(3,33) = 0.970, p = 0.418 | F(3,33) = 1.668, p = 0.193 |

| Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices | F(3,33) = 1.444, p = 0.238 | F(3,33) = 0.657, p = 0.584 | F(3,33) = 0.658, p = 0.584 |

Figure 2.

SCQ scores for groups over time.

Figure 3.

ADOS-Imagination scores for groups over time.

Figure 4.

ADOS-Communication scores for groups over time.

Discussion

In this study, all children changed significantly over time on most aspects of measurement and it appears that children with autism are developing in a very similar way across the two countries. Similarly, no differences between the children in the UK and Greece were found, either at the start of the study, or in the rates of change in skills over time. With respect to the effect of the therapy context on the development of children with autism, it was found that there were no differences across groups at the beginning of the study and there were mainly nonsignificant interactions in the rate of change across the differing types of intervention. However, further analysis showed some important differences which warrant further investigation. Namely, speech and language therapy participants (at least in the UK) presented with more change on social communication scores across the measures; while psychotherapy participants showed significant greater increase in imagination. Although the interaction was not significant, occupational therapy participants presented as having a significant reduction of stereotypical behavior (whilst there was no significant change for SLT groups). Thus, this study provides preliminary evidence that regardless of country or type of intervention, children with autism make change in real terms over time. Nevertheless, certain types of therapy context might be particularly well suited to specific areas of progress.

The findings from the current study support those of previous studies (Charman et al. 2005; Kelley et al. 2010; McGovern and Sigman 2005; Seltzer et al. 2004; Sutera et al. 2007), suggesting that autism symptoms do change over time. This is positive for parents as well as therapists and educators working with this group. However no previous studies have explored whether this progress is similar when children from different countries are compared. Our study indicates that not only abilities as measured at recruitment are similar, but also that change is paralleled across Greece and the UK. This is a somewhat reassuring finding indicating perhaps that standard diagnostic tools such as the DSM guidelines are enabling equivalence across different parts of Europe. However, overall, the children in the UK seem to have improved faster in the areas of social skill and imagination compared to the children in Greece.

As noted in the introduction, the choice of interventions facing parents with autism is large and many have been shown to have positive results (Baker-Ericzen et al. 2007; Case-Smith and Bryan 1999; Francke and Geist 2003; Kasari et al. 2006; Linderman and Stewart 1999; Smith et al. 2010; Watling and Dietz 2007). It is important to highlight again that the current study considered therapeutic experience as an additional aspect that may associate with development, rather than addressing therapy efficacy. As such, we acknowledge that children were not randomized to therapy types and that no causal conclusions can be made. Indeed, participant families had chosen their own intervention, and these choices are likely made on a number of different factors such as parental concern about particular aspects of difficulty. As a result, parents may also work on this aspect of development more with their children at home after therapy has finished. Nevertheless, we believe that it is important to acknowledge the different treatment pathways explicitly as we have done here, rather than ignore this factor. In addition, it is worth pointing out that at the point of recruitment, there were no significant differences in the child characteristics measured. It may also be that the generally positive changes in the current study are attributable to the ‘generalized therapeutic attention’ that each family received and this might explain why, in the main, therapy context did not seem to affect targeted change. Most children with autism will probably make some progress in the early stages of an approach regardless the type of treatment provided (Jordan et al. 1998). As discussed by Jordan et al. (1998) there is a need for therapists to assess the criteria that might lead to the decision on whether a specific intervention is likely to be more appropriate for particular children. The current study adds to the existing knowledge base since it explores potential progress differences between children with similar profiles but who have experienced different therapy contexts.

In addition, it should be noted that all types of intervention included the use of verbal mediation and that even the one to one interaction that the children had with a therapist might have boosted communication regardless of the type of treatment that followed. Indeed, Hébert et al. (2014) investigated the role of occupational therapy for the promotion of communication in children with autism and highlighted the importance of occupational therapy in promoting early communication skills. Furthermore, therapist questionnaires completed in the current study suggested that the SLT service in the UK might offer a wider range of techniques and strategies with respect to children’s social/behavioral skills compared to the one in Greece. This might explain why the children that had SLT in the UK improved more in their communication skills. However, it is important to note that whilst we gathered information about therapy content, this was to inform our general understanding of the therapy context and not to assess treatment fidelity.

In the current study there was some indication that the stereotypic behaviors of the children in the occupational therapy group were reduced over the year. This could be attributed to the attention that occupational therapists pay on decreasing stereotypic behaviors by using various sensory-based treatment techniques (Ayres 1979). Linderman and Stewart (1999) and Watling and Dietz (2007) also reported progress in social interaction in children receiving occupational therapy and Makrygianni and Reed (2010) found that Greek intervention programs were helpful in improving stereotypic behaviors, which affect learning processes. Further research in this area could shed light to the changes on this autistic feature.

It is of particular interest that there was a significant reduction of stereotypic behaviors in the children from the psychotherapy and occupational therapy groups (which appeared to drive the significant main effect of time, despite the interaction being nonsignificant). Stereotypic behavior is included as one of the diagnostic criteria for autism (DSM-5) and it has been defined as ‘repetitive and apparently purposeless body movements (e.g. body rocking) body part movements (e.g. hand flapping, head rolling) or use of the body to generate object movements (e.g. plate spinning, string twirling)’ (Lewis and Bodfish 1998, p.82). Therefore, this behavior can affect the development of various skills and could be socially stigmatizing. Other authors have highlighted our limited knowledge on effective intervention for repetitive behaviors (Leekam et al. 2011; Turner 1999). According to Leekam et al. (2011), the available evidence has ‘made it difficult to discern distinct, reliable patterns of increases or decreases in RRBs across time’ (p. 23). Most previous studies reporting on the intervention context have been single case studies (see Patterson et al. 2010 for a review) so the change over time seen in all of our treated groups is encouraging and requires further investigation.

This study provides important new evidence regarding the outcomes of psychodynamic/psychoanalytic psychotherapy for children with autism, with few previous studies that have evaluated the effectiveness of psychoanalytic/psychodynamic psychotherapy in everyday clinical settings and difficult-to-treat populations, like children with autism (Emmelkamp et al. 2014). The results of this study provide a more rigorous understanding of the impact of psychotherapy in comparison to other therapy contexts and demonstrate how a psychodynamically based approach can facilitate change when treating children with autism. This study suggests that psychodynamic treatment can be of value in helping children with autism to advance their imagination, and their vocabulary; their ability to interpret, recall and execute commands; their social communication skills and that it may help to reduce their stereotypic behaviors to at least the same degree as other therapy contexts. These results are in accordance with the findings by Bromfield (2000) who demonstrated the therapeutic benefits of psychodynamic play when treating children with autism and those of Shuttleworth (1999) who suggested that psychoanalytic psychotherapy can help children with autism develop. However, to the authors’ knowledge this is the first study to use group data to show statistical change in a group receiving only psychotherapy.

The current findings provide particularly useful evidence for parents and healthcare professionals in Greece who work in the field of autism where this type of therapy is not currently widespread.

Strengths and limitations

One aspect this study did not address is the role of parents in the therapy which is also of relevance. As discussed by Carter et al. (2011), children with autism tend to benefit from an intervention when their parents are included in the treatment and they work all together. Such parent involvement could be the substantial element for the success of the group of children that received psychotherapy. It is imperative, when planning an intervention for families of children with autism, to view the whole family as members of a system who influence each other in order to provide the most appropriate care to the child and the rest of the family (Hanson and Lynch 2013). Future studies exploring the different aspects of interventions, e.g. parental involvement, are needed in order to recognize which elements of treatment are important for successful outcomes.

A limitation of this study was its moderate sample size. With an even larger sample, subtler differences might have been revealed between the groups regarding change. Nevertheless, this study is one of the largest cross-national studies on this topic and goes some way to highlighting different therapy contexts. The fact that children’s skills naturally change over a year should also be considered, as it will have affected the results along with the associated gains from therapies during that period. In addition, the issue of dosage of intervention over the intervention period was not controlled for in this study and the number of therapy sessions made available to the children may influence the effectiveness of that intervention.

Missing data can be a methodological challenge in longitudinal studies. In this study, only two families were not retained at time 2, however, it would have been preferable to have kept all participants in the study. Moreover, the fact that only private practices were included in the current study might limit the generalizability of the results. This study was only focused on the private sector in order to reflect the therapy choice that the parents made for their children, since in the public sector that choice is not always parent-led. Also, the inclusion of private practices made it easier to recruit children who were not receiving additional therapy-types and made the groups across countries more homogenous by limiting the effects of social disadvantage.

There are challenges when collecting and analyzing data from countries with different sociocultural contexts and languages, particularly the issue of translation and adaptation of an instrument (Geisinger 1994). However, in this study the dual cultural/linguistic background of the researcher assisted in minimizing this potential problem. Personal communication and advice from researchers experienced in using nonstandardized Greek versions of the assessment measures was considered important, and the tasks completed in the current study were based on previous Greek adaptations by Stavrakaki and Van der Lely (2010) and following advice from Stravrakaki and Kambanaros (personal communication). Despite this, measures that are normed for Greek children would be useful in research of this kind, and need developing.

Future research

In the future, it would be advantageous to conduct a prospective study in which children with autism are randomized to intervention groups, as it is acknowledged that the present study explores the intervention context, rather than evaluating the effectiveness of therapy directly. Also, it would be interesting to assess a group receiving no intervention, but for ethical reasons, this would be unlikely in the countries considered here.

Additionally, a year might not be enough for a child with autism to change significantly, so it could be more useful to follow up the children every year for a longer period in order to have more robust findings. A longer follow-up period with additional assessment points would have provided a more accurate depiction of long-term effects of the different treatments. Future studies could also make private vs public healthcare comparisons and could focus on the elements of specific service use. According to Cuvo and Vallelunga (2007) the diversity in the clinical picture of autism leads to a greater need for individualized interventions and the heterogeneity found across ASD symptoms makes every intervention practice more of a challenge (Fountain et al. 2012).

Conclusion

To the authors’ knowledge this study is one of the largest cross-national studies on this topic of childhood autism. In this research study, all children changed significantly over time on most measures. Based on the assessments of the children living in Greece and the UK, children with autism develop in a very similar way across the two countries. No group differences were found in children’s profiles either at the beginning of the study, or in the rates of change in skills. The fact that in the majority the children are similar between the two countries supports the notion of autism being diagnosed in similar ways across countries (Sipes et al. 2011) and suggests cross-cultural validity of the disorder. Additionally, the children assessed showed progress in their communication and social skills after receiving therapy, regardless of the type of intervention they had received. These results lead us to believe that regardless of the type of therapy that the children received, their skills advanced during the 12 months that they were followed up. In light of the findings from the current study, it seems that autism symptoms do change over time.

With respect to the effect of the therapy context on the development of children with autism, it was found that there were only a few differences in change across intervention contexts, but that those that exist might provide important information for therapy choice. The diversity in the symptoms of children with autism has led to a vast amount of treatment options provided by different services across different settings. Consequently, the choice for parents has become even more difficult. The current study has provided reassuring findings to parents of children with autism as all treatments examined were associated with positive changes in development, and only a few differences in change across intervention contexts were discovered. The pressure to choose the ‘right’ therapy often reported by parents of children with autism may therefore be reduced by the results of this study.

Further research exploring the individual characteristics of children with autism is needed in order to determine what treatment or combination of treatments work for each child. In addition, there is a need to focus on the recognition of essential treatment elements in order to identify what makes each therapy successful. Nonetheless, the present study raises awareness of other types of therapy that are available in terms of intervention, especially in contrast to behavioral techniques.

Since change occurred in all therapy contexts in this study, our results could assist in creating a combined treatment plan that will provide desired outcomes. A multidisciplinary approach might be able to bridge the gap between clinical services, families and research. This highlights the importance of collaboration between professionals of different clinical backgrounds and promotes interprofessional practice in order to provide the most effective course of treatment. It calls upon professions to exchange knowledge, and to combine their expertise to plan and provide coordinated services for better developmental outcomes for children with autism.

References

- Alvarez, A. 1996. Addressing the element of deficit in children with autism: Psychotherapy which is both psychoanalytically and developmentally informed. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 1, 525–537. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, A., Reid, S. and Hodges, S. 1999. Autism and play: The work of the Tavistock autism workshop. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 15, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, A. and Lee, A. 2004. Early forms of relatedness in autism: A longitudinal clinical and quantitative single-case study. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 9, 499–518 [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, D. K., Maye, M. P. and Lord, C. 2011. Changes in maladaptive behaviors from midchildhood to young adulthood in autism spectrum disorder. American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 116, 381–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayres, A. J. 1979. Sensory integration and the child. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Baghdadli, A., Picot, M. C., Michelon, C., Bodet, J., Pernon, E., Burstezjn, C., Hochmann, J., Lazartigues, A., Pry, R. and Aussilloux, C. 2006. What happens to children with PDD when they grow up? Prospective follow-up of 219 children from preschool age to mid-childhood. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 115, 403–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baio, J. 2014. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years-autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites. United States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Surveillance Summaries 63, 1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird, G., Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., Meldrum D. and Charman, T. 2006. Prevalence of disorders of the autism spectrum in a population cohort of children in South Thames: The Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP). Lancet, 368, 210–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Ericzen, M. J., Stahmer, A. C. and Burns, A. 2007. Child demographics associated with outcomes in a community-based pivotal response training program. Journal of Positive Behavioral Interventions, 9, 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen, S., Weelwright, S., Skinner, R., Martin, J. and Clubley, E. 2001. The Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31, 5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batten, A., Corbett, C., Rosenblatt, M., Withers, L. and Yuille, R. 2006. Make school make sense: Autism and education: The reality for families today. London: National Autistic Society. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Itzchak, E., Watson, L. R. and Zachor, D. A. 2014. Cognitive ability is associated with different outcome trajectories in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism Developmental Disorders, 44, 2221–2229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Sasson, A., Carter, A. S. and Briggs-Gowan, M. J. 2009. Sensory over-responsivity in elementary school: Prevalence and social-emotional correlates. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 705–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromfield, R. 2000. It's the tortoise race: Long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy with a high functioning autistic adolescent. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 20, 732–745. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, A., Messinger, D., Stone, W., Celimli, S., Nahmias, A. and Yoder, P. 2011. A randomized controlled trial of Hanen's “More Than Words” in toddlers with early autism symptoms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 741–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case-Smith, J. and Bryan, T. 1999. The effects of occupational therapy with sensory integration emphasis on preschool-age children with autism. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 53, 489–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case-Smith, J., Weaver, L. L. and Fristad, M. A. 2015. A systematic review of sensory processing interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 19, 133–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlop-Christy, M. H., Carpenter, M., Le, L., LeBlanc, L. A. and Kellet, K. 2002. Using the Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) with children with autism: Assessment of PECS acquisition, speech, social-communicative behaviour, and problem behaviour. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 35, 213–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charman, T., Taylor, E., Drew, A., Cockerill, H., Brown, J. and Baird, G. 2005. Outcome at 7 years of children diagnosed with autism at age 2: Predictive validity of assessments conducted at 2 and 3 years of age and pattern of symptom change over time. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 500–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuvo, A. J. and Vallelunga, L. R. 2007. A transactional systems model of autism services. The Behavior Analyst, 30, 161–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, L. M., Dunn, L. M., Whetton, C. and Burley, J. 1997. The British Picture Vocabulary Scale. 2nd ed. Windsor: NFER-Nelson. [Google Scholar]

- Emmelkamp, P. M. G., David, D., Beckers, T. O. M., Muris, P., Cuijpers, P., Lutz, W., Andersson, G., Araya, R., Banos Rivera, R. M., Barkham, M. and Berking, M. 2014. Advancing psychotherapy and evidence-based psychological interventions. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 23, 58–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazlioglu, Y. and Baran, G. 2008. A sensory integration therapy program on sensory problems for children with autism. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 106, 415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fountain, C., Winter, A. S., Bearman, P. S. 2012. Six developmental trajectories characterize children with autism. Pediatrics, 129, 1112–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francke, J. and Geist, E. 2003. The effects of teaching play strategies on social interaction for a child with autism: A case study. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 18, 125–140. [Google Scholar]

- Geisinger, K. F. 1994. Cross-cultural normative assessment: Translation and adaptation issues influencing the normative interpretation of assessment instruments. Psychological Assessment, 6, 304–312. [Google Scholar]

- Gillberg, C. and Wing, L. 1999, Autism: Not an extremely rare disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 99, 399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn, S. and Cunningham, C. 2005. Performance of young people with downs syndrome on the Leiter-R and the British Picture Vocabulary Scales. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49, 239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonela, L. 2006. Autism: Riddle and reality. Athens: Oddysey. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, K., McElduff, F. and Wade, A., 2011. A communication based intervention for non-verbal children with autism. What changes? Whom benefits? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79, 447–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould, K. 2011. Fantasy play as the conduit for change in the treatment of a six-year-old boy with Asperger’s syndrome. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 31, 240–251. [Google Scholar]

- Green, V. A., Pituch, K. A., Itchon, J., Choi, A., O’Reilly, M. and Sigafoos, J. 2006. Internet survey of treatments used by parents of children with autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 27, 70–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, M. J. and Lynch, E. W. 2013. Understanding families: Supportive approaches to diversity, disability and risk. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Paul Brookes Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward, D., Eikeseth, S., Gale, C. and Morgan, S. 2009. Assessing progress during treatment for young children with autism receiving intensive behavioural interventions. Autism, 13, 613–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hébert, M. L. J., Kehayia, E., Prelock, P. A., Wood-Dauphinee, S. and Snider, L. 2014. Does occupational therapy play a role for communication in children with autism spectrum disorders? International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16, 594–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, L. and Rice, T. 2012. Psychodynamic considerations in the treatment of a young person with autistic spectrum disorder: A case report. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 11, 67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Iwanaga, R., Honda, S., Nakane, H., Tanaka, K., Toeda, H. and Tanaka, G. 2014. Pilot study: Efficacy of sensory integration therapy for Japanese children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Occupational Therapy International, 21, 4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, R., Jones, G. and Murray, D. 1998. Educational interventions for children with autism: A literature review of recent and current research. London: DfEE. [Google Scholar]

- Kamphaus, R. 2005. Clinical assessment of child and adolescent intelligence. New York, NY: Springer Science and Business Media, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Kanner, L. 1943. Autistic disturbance of affective contact. Nervous Child, 2, 217–250. [Google Scholar]

- Kasari, C., Freeman, S. and Paparella, T. 2006. Joint attention and symbolic play in young children with autism: A randomized controlled intervention study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 611–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazem, A. M., Al-Zubaidi, A. S., Alkharusi, H. A., Yousif, Y. H., Alsarmi, A. M., Al-Bulushi, S. S., Aljamali, F. A., Al-Mashhdany, S., Al-Busaidi, O. B., Al-Fori, S. M. and Alshammary, B. M. 2009. A normative study of the Raven Coloured Progressive Matrices Test for Omani children aged 5 through 11 years. Malaysian Journal of Education, 34, 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, E., Naigles, L. and Fein, D. 2010. An in-depth examination of optimal outcome children with a history of autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4, 526–538. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, R., O’Reilly, M., Healy, O., Rispoli, M., Lydon, H., Streusand, W., Davis, T., Kang, S., Sigafoos, J., Lancioni, G. and Didden, R. 2012. Sensory integration therapy for autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6, 1004–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Leekam, S. R., Prior, M. R. and Uljarevic, M. 2011. Restricted and repetitive behaviors in autism spectrum disorders: A review of research in the last decade. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 562–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, M. H. and Bodfish, J. W. 1998. Repetitive behavior disorders in autism. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 4, 80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Linderman, T. M. and Stewart, K. B. 1999. Sensory integrative-based occupational therapy and functional outcomes in young children with pervasive developmental disorders: A single subject study. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 53, 207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord, C., Rutter, M. and LeCouteur, A. 1994. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24, 659–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord, C., Risi, S., Lambrecht, L., Cook, E. H., Leventhal, B. L., DiLavore, P. C., Pickles, A. and Rutter, M. 2000. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule—Generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30, 205–223 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makrygianni, M. K. and Reed, P. 2010. Factors impacting on the outcomes of Greek intervention programmes for children with autistic spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4, 697–708. [Google Scholar]

- Mandy, W., Charman, T., Puura, K. and Skuse, D. 2014. Investigating the cross-cultural validity of DSM-5 autism spectrum disorder: Evidence from Finnish and UK samples. Autism, 18, 45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern, C. W. and Sigman, M. 2005. Continuity and change from early childhood to adolescence in autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midgley, N. and Kennedy, E. 2011. Psychodynamic psychotherapy for children and adolescents: A critical review of the evidence base. Journal of Child Psychotherapy, 37, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, V. and Goodson, S. 2003. How well does early diagnosis of autism stand the test of time? Follow-up study of children assessed for autism at age 2 and development of an early diagnostic service. Autism, 7, 47–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muratori, F., Salvadori, F., D'Arcangelo, G., Viglione, V. and Picchi, L. 2005. Childhood psychopathological antecedents in early onset schizophrenia. European Psychiatry, 20, 309–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Autistic Society , 2010. What is autism? Available at: http://www.nas.org.uk/ [Accessed October, 2016].

- Oosterling, I., Rommelse, N., De Jonge, M., Van der Gaag, R., Swinkels, S., Roos, S., Visser, J. and Buitelaar, J. 2010. How useful is the SCQ in toddlers at risk for autism spectrum disorder? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51, 1260–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou, V. 2005. International perspectives: Greece. In: Volkmar F. R., Paul R., Klin A. and Cohen D., eds. Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders. New Jersey: Wiley, pp.1215–1218. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, S., Smith V. and Jelen M. 2010. Behavioural intervention practices for stereotypic and repetitive behaviour in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 52, 318–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozzi, M. E. 2003. The use of observation in the psychoanalytic treatment of a 12-year-old boy with Asperger's syndrome. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 84, 1333–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven, J., Raven, J. C. and Court, J. H. 2003. Manual for Raven's Progressive Matrices and Vocabulary Scales. Section 1: General overview. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, S., Alvarez, A. and Lee, A. 2001. The Tavistock autism workshop approach. In: Richer J. and Coates S., eds. Autism—The search for coherence. London: Jessica Kingsley, pp.182–192. [Google Scholar]

- Roser, K. 1996. A review of psychoanalytic theory and treatment of childhood autism. Psychoanalytic Review, 83, 325–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, M., Bailey, A. and Lord, C. 2003. Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Salomone, E., Beranová, S., Bonnet-Brilhault, F., Lauritsen, M. B., Budisteanu, M., Buitelaar, J., Canal-Bedia, R., Felhosi, G., Fletcher-Watson, S., Freitag, C. and Fuentes, J. 2016. Use of early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorder across Europe. Autism, 20, 233–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaaf, R. C., Benevides, T., Mailloux, Z., Faller, P., Hunt, J., van Hooydonk, E., Freeman, R., Leiby, B., Sendecki, J. and Kelly, D. 2013. An intervention for sensory difficulties in children with autism: A randomized trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 1493–1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreibman, L. and Stahmer, A. C. 2014. A randomized trial comparison of the effects of verbal and pictorial naturalistic communication strategies on spoken language for young children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 1244–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer, M. M., Shattuck, P. and Abbeduto, L. 2004. Trajectory of development in adolescents and adults with autism. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 10, 234–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semel, E., Wiig, E. and Secord, W. 2003. Clinical evaluation of language fundamentals-4 (CELF-4). San Antonio, TX: PsychCorp. [Google Scholar]

- Sherkow, S. P. 2011. The dyadic psychoanalytic treatment of a toddler with autism spectrum disorder. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 31, 252–275. [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth, A. 1999. Finding new clinical pathways in the changing world of district child psychotherapy. Journal of Child Psychotherapy, 25, 29–49. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, D. J. 1999. The developing mind. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sipes, M., Matson, J. L., Worley, J. A. and Kozlowski, A. M. 2011. Gender differences in symptoms of autism spectrum disorders in toddlers. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5, 1465–1470. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, I., Koegel, R., Koegel, L., Openden, D., Fossum, K. and Bryson, S. 2010. Effectiveness of a novel community-based early intervention model for children with autistic spectrum disorder. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 115, 504–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stampoltzis, A., Papatrecha, V., Polychronopoulou, S. and Mavronas, D. 2012. Developmental, familial and educational characteristics of a sample of children with autism spectrum disorders in Greece. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar]

- Stavrakaki, S. and Van der Lely, H. 2010. Production and comprehension of pronouns by Greek children with specific language impairment. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 28, 189–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer-Azaroff, B., Hoffman, A. O., Horton, C. B., Bondy, A. and Frost, L. 2009. The Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS): What do the data say? Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24, 89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Sutera, S., Pandey, J., Esser, E., Rosenthal, M., Wilson, L., Barton, M.Green, J., Hodgson Robins, D., Dumont-Mathieu, T. and Fein, D. 2007. Predictors of optimal outcome in toddlers diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 98–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szatmari, P., Georgiades, S., Duku, E., Bennett, T. A., Bryson, S., Fombonne, E., Mirenda, P., Roberts, W., Smith, I. M., Vaillancourt, T., Volden, J., Waddell, C., Zwaigenbaum, L., Elsabbagh, M. and Thompson, A. 2015. Developmental trajectories of symptom severity and adaptive functioning in an inception cohort of preschool children with autism spectrum disorder. JAMA Psychiatry, 72, 276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taxitari, L., Kambanaros, M. and Grohmann, K. K. 2015. A Cypriot Greek adaptation of the CDI: Early production of translation equivalents in a bi(dia)lectal context. Journal of Greek Linguistics, 15, 122–145. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, M. A. 1999. Annotation: Repetitive behavior in autism: A review of psychological research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40, 839–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorgraft, Y., Faberstein, I., Spiegel, R. and Apter, A. 2007. Retrospective evaluation of an intensive method of treatment for children with pervasive developmental disorder. Autism, 11: 413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse, L. 2013. Rethinking autism: Variation and complexity. London: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Watling, R. L. and Dietz, J. 2007. Immediate effect of Ayres’s sensory integration-based occupational therapy intervention on children with autism spectrum disorders. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61, 574–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb, E. V., Lobo S., Hervas, A., Scourfield J. and Fraser, W. I. 1997. The changing prevalence of autistic disorder in a Welsh health district. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 39, 150–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing, L. 1997. The autistic spectrum. Lancet, 350, 1761–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodman, A. C., Smith, L. E., Greenberg, J. S. and Mailick, M. R. 2015. Change in autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors in adolescence and adulthood: The role of positive family processes. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45, 111–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]