Abstract

Poor teat and udder structure, frequently associated with older cows, impact cow production and health as well as calf morbidity and mortality. However, producer culling, for reasons including age, production, feed availability, and beef markets, creates a bias in teat (TS) and udder scores (US) assessed and submitted to the Canadian Angus Association for genetic evaluations toward improved mammary structure. In addition, due to the infancy of the reporting program, repeated scores are rare. Prior to the adoption of genetic evaluations for TS and US in Canadian Angus cattle, it is imperative to verify that TS and US from young cows are the same traits as TS and US estimated on mature cows. Genetic parameters for TS and US from all cows (n = 4,192) and then from young cows (parities 1 and 2) and from mature cows (parity ≥ 4) were estimated using a single-trait animal model. Genetic correlations for the traits between the two cow age groups were estimated using a two-trait animal model. Estimates of heritability (posterior SD [PSD]) were 0.32 (0.07) and 0.45 (0.07) for young TS and US and 0.27 (0.07) and 0.31 (0.07) for mature TS and US, respectively. Genetic correlation (PSD) between the young and mature traits was 0.87 (0.13) for TS and 0.40 (0.17) for US. Genome-wide association studies were used to further explore the genetic and biological commonalities and differences between the two groups. Although there were no genes in common for the two USs, 12 genes overlapped for TS in the two cow age groups. Interestingly, there were also 23 genes in common between TS and US in mature cows. Based on these findings, it is recommended that producers collect TS and US on their cow herd annually.

Keywords: beef cattle, cow longevity, genetic selection, mature traits

Introduction

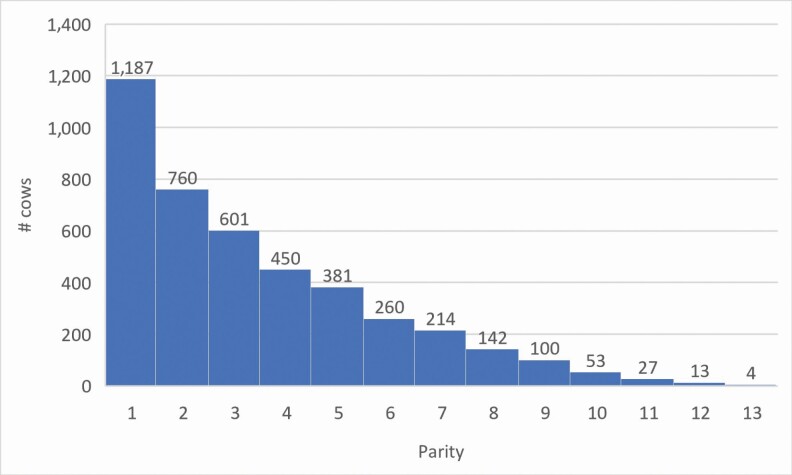

Teat and udder structure are important traits contributing to production efficiencies as well as animal health and welfare in beef operations. They impact longevity (McDermott et al., 1992; Bunter et al., 2013), production (Watts et al., 1986; Beal et al., 1990), and health (DeGroot et al., 2002; Persson Waller et al., 2014) in cows. Subsequently, teat and udder structure also impact calf morbidity and mortality (Frisch, 2010; Bunter et al., z013). Female production and structural traits change with parity (Arthur et al., 1992; Smith et al., 2017). In dairy cattle, milking traits (milk volume, milking speeds, and colostrum concentration) and udder structure are also impacted by parity (Samoré et al., 2010; Morrill et al., 2012; McGee and Earley, 2019). Furthermore, the number of infected and blind mammary quarters increased with parity in beef cows (Paape et al., 2000). To date, teat scores (TSs) and udder scores (USs) are not recorded annually on all Canadian Angus cows. Thus, to assess the repeatability of these traits over a lifetime, we estimated the genetic correlation between young scores and mature scores and investigated using genome-wide association study (GWAS) whether young and mature TS and US were influenced by the same set of genes and molecular pathways. Young cows (parities 1 and 2) and mature cows (parity ≥ 4) were defined based on parity distribution (Figure 1) and producer culling practices, whereby producers cull higher proportions of retained heifers based on production after their second parity. Cows measured for TS and US in their third parity were removed to create a significant distinction between the two cow age groups.

Figure 1.

Parity distribution of Canadian Angus cows scored for teat and udder structure using the BIF (2016) scoring guideline.

Two approaches are routinely utilized for developing genetic evaluations for repeated traits (e.g., across parities), a repeatability model and a correlated trait model. Repeatability models, best used when multiple measures of the same trait are available on the same individuals, assume set genetic correlations, equal variance, and equal environmental correlation between all records for the same individual (Mrode, 2005). In comparison, correlated trait models (multi-trait models), that consider measurements at various ages/parity as separate but correlated traits, assume varying phenotypic and genetic correlations between traits. Traits can either persist throughout productive life, change between stages of production (young vs. mature, for example), or per expression (at every parity, for example). Model appropriateness must be tested for traits expressed recurringly in production lifetimes. For example, in evaluating shell quality in layer chickens, Wolc et al. (2017) demonstrated the value of testing for repeatability, reporting that multi-trait models resulted in a 10% higher accuracy of prediction. There are similar reports for recurring farrowing traits expressed in pigs (Costa et al., 2016). Conversely, in cattle, Burrow (2001) initially treated annual traits of pregnancy and days-to-calving separately for each mating; however, as genetic correlations between the repeated measures were >0.92, these repeated measures could be defined and treated as single traits.

The Canadian Angus genetic evaluation aims to identify cattle, at a young age, with the genetic potential to maintain good TS and US throughout lifetime productivity. Furthermore, successful breeding programs depend on the appropriate models for genetic evaluation. Given the recurring expression of teat and udder structure and the opportunity to collect scores on the same cows annually, the objective of this study was to estimate genetic correlations between TS and US at various stages of production lifetime. To improve genetic and biological understanding of the traits at different parities, we aimed to identify genomic regions and candidate genes explaining variation in them through GWASs.

Materials and Methods

Collection of TS and US was done in accordance with the Canadian Code of Practice for the care and handling of farm animals. All procedures involving cattle were reviewed and approved by the University of Calgary Veterinary Sciences Animal Care Committee (Protocol AC16-0218).

Teat and udder scores

Purebred Canadian Angus producers, from across the nation, scored 4,192 Canadian Angus cows for teat and udder structure within 24 h after calving, in accordance with the Beef Improvement Federation (BIF) scoring guidelines (Table 1). Scores ranged from 1 to 9, with the smallest teats and tightest udders assigned a score of 9, and large, bottle-shaped teats and pendulous udders that have lost support from suspensory ligaments assigned a score of 1 (BIF, 2016). As suggested by the guidelines, all bred females in each herd were scored, recording teat and udder on the weakest quarter of each cow.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of Canadian Angus cows phenotyped for teat and udder structure using the BIF (2016) recommended scoring guideline

| TS US1 | No. of cows | Parity included | Median | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All cows2 | 4,192 | 1 to 13 | 7 | 1 | 9 |

| Young cows3 | 1,947 | 1 to 2 | 7 | 2 | 9 |

| Mature cows4 | 1,644 | 4 to 13 | 6 | 1 | 9 |

1TS, teat score on a 1 to 9 scale; US, udder score on a 1 to 9 scale.

2All cows, cows scored in parity 1 to 13.

3Young cows, cows scored in parity 1 and 2.

4Mature cows, cows scored in parity ≥ 4.

Additional cow information including parity, date of birth, and breed was made available by the Canadian Angus Association (CAA) database. Cows scored for teat and udder structure ranged from parity 1 to 13 (Figure 1). Young teat score (YTS) and young udder score (YUS) were defined as scores from the first or second parity cows (n = 1,947). Mature teat score (MTS) and mature udder score (MUS) were defined as cows scored in their fourth parity or above (n = 1,644). Cows that were scored in their third parity (n = 601) were excluded. Contemporary groups (CG) were defined as herd, year of measure, and calving season (with calving season defined as December to May = 1 and June to November = 2). CG with ≤3 animals and those with no variation were excluded. A total of 113 CG, comprised of 3 to 375 cows, were included. Breed was defined as Black Angus = 1, Red Angus = 2, and Black-Red Angus Cross = 3. Thus, data from a total of 2,863 Black Angus cows, 968 Red Angus cows, and 361 Black-Red Angus cross cows were used. The CAA provided four-generation pedigree information for these cows, consisting of 55,220 animals, including 3,475 dams and 1,315 sires.

Genotypes

A total of 1,856 Canadian Angus cattle were genotyped using the Illumina Bovine SNP50 v3 BeadChip (50K, Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA). Included were 74 pairs of sire–progeny wherein both sire and progeny (scored female) were genotyped, and 477 pairs of dam–progeny wherein both dam and scored progeny were genotyped. Of the 1,947 cows placed in the young cow age group, 511 were genotyped, and of the 1,644 cows placed in the mature cow age group, 863 were genotyped. The Illumina BeadChip contains 48,595 highly polymorphic single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers selected for high minor allele frequency values and uniform genome coverage for Bos taurus cattle, with a mean distance of 37 kb between markers. Quality control was applied to exclude SNPs that had a call rate lower than 0.95, a minimum allele frequency lower than 0.01, were monomorphic, or were deviant from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (χ 2 > 0.05). Cattle were excluded for ≥ 0.10 frequency missing genotypes or parent–progeny Mendelian conflicts (Misztal et al., 2014). After quality control, a total of 1,856 cattle with genotypes comprised of 30,419 effective SNPs remained and were used for further (co)variance component estimates and GWAS analysis.

Data analyses

Genetic parameters were estimated for the following six traits: ALLTS, teat score using teat scores taken on all cows; ALLUS, udder scores using udder scores taken for all cows; YTS, young teat score using teat scores taken on cows in their first and second parity only; YUS, young udder score using udder scores taken on cows in their first and second parity only; MTS, mature teat score using teat scores taken on cows in their fourth or greater parity; and MUS, mature udder score using udder scores taken on cows in their fourth or greater parity (Table 1). In preliminary analyses, factors that significantly affected each of the scores were determined using General Linear Models in SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute, 2015). Factors tested for significance (P-value ≤ 0.05) and subsequently included in the animal model, fitted as fixed effects, were CG, breed, and cow age (y) at calving.

Trait heritability and (co)variance components were estimated using Bayesian inference via Gibbs sampling, specifically GIBBS2F90 and POSTGIBBSF90 software (Misztal et al., 2014). Further, SNP effects were estimated using the POSTGSF90 software. This method combines, simultaneously, all phenotypes from genotyped and non-genotyped cattle, molecular SNP markers, and pedigree information to calculate genomic estimated breeding values (GEBVs) and subsequently converts the GEBVs to SNP marker effects through an iterative process described below. As per Wang et al. (2014), weighted single-step genomic best linear unbiased prediction (ssGBLUP) performs well when working with a data set containing many phenotypes and a relatively small number of genotypes. For each analysis, 700,000 iterations were generated, retaining every 50th sample. The first 200,000 iterations were discarded as standardized fixed burn-in for all analyses. Thus, 10,000 samples were used for (co)variance and genetic parameter estimations.

For each of the six traits, the statistical model used was as follows:

where y is the vector of TS and US observations; β is the vector of fixed effects (CG, breed, and the covariate of cow age at calving); a is the vector of additive genetic effects with the assumption that , where H is the matrix that combines pedigree (A) and genomic information (G) and Va is the covariance matrix of additive effects between traits; e is the vector of residual effects with the assumption that , where I is the identity matrix and Ve is the residual covariance matrix of error terms between traits; and X and Z are incidence matrices relating β and a to y. For multi-trait analysis, the residual covariance was set to zero for YTS–MTS and YUS–MUS as young and mature teat and udder scores were measured on different animals. The inverse of H matrix was constructed, per Aguilar et al. (2010), and can be represented as follows:

where is the numerator relationship matrix of all pedigreed animals, is the inverse of numerator relationship matrix for all genotyped cattle (Aguilar et al., 2010), and is the inverse of the genomic relationship matrix (VanRaden, 2008). The G matrix was built using SNP marker information, in accordance to VanRaden (2008), as follows:

where Z is the incidence matrix containing genotypes (aa = 0, Aa = 1 and AA=2) adjusted for allele frequency, D is a diagonal matrix of weights for SNP markers (initially D = I), and q is a weighting factor. The weighting factor was as in Vitezica et al. (2011), ensuring that the average diagonal in G is close to that of .

SNP effects and weights for weighted single-step GWAS (WssGWAS) were calculated as follows, in accordance to Wang et al. (2012):

Let D = I in the first iteration.

Calculate G = ZDZ′q.

Calculate the GEBV using ssGBLUP for the entire dataset.

GEBV were converted to estimates of SNP effects (û): where , where is the GEBV of genotyped animals.

The weight of individual SNPs was calculated as , where i is the ith SNP marker.

The SNP weights were normalized to keep the total genetic variance (GV) constant:

was calculated.

7. End, or loop to step 2

SNP effects were calculated, as presented by Wang et al. (2012), using the above described iterative process (steps 2 to 6) thrice over in order to increase and reduce the weight of consecutive SNPs (SNP window) with large and small effects, respectively. Thus, the SNP weights were updated at each iteration to reconstruct the G matrix and reestimate the SNP effects. The percentage of total GV explained by the i-th set of consecutive SNPs (i-th SNP window), which contained 20 consecutive nonoverlapping SNP markers, was calculated as follows:

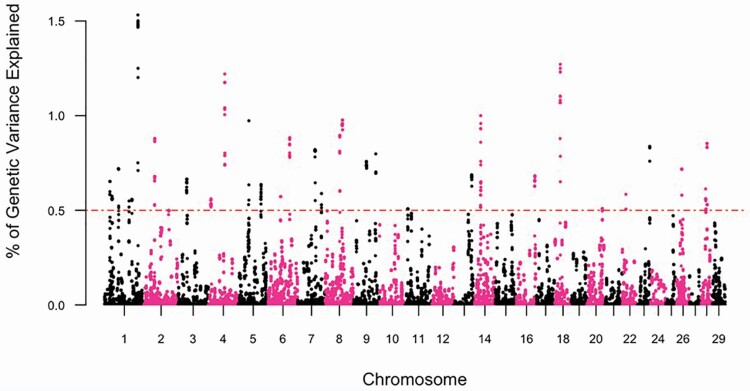

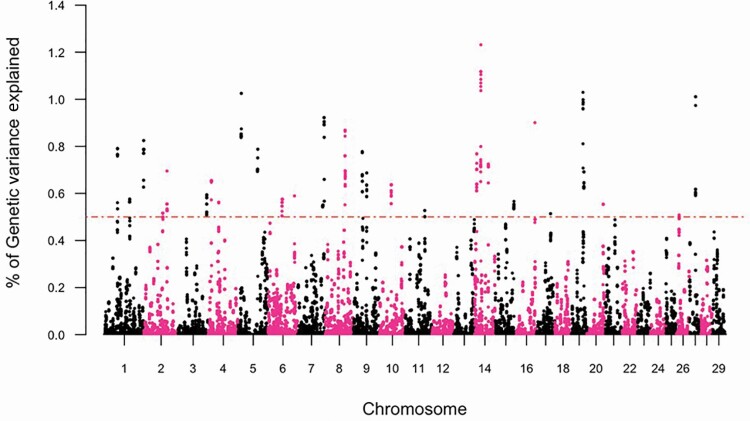

where is the genetic value of the i-th SNP window (that consists of 20 continuous SNPs); is the additive GV; is the vector of gene content of the j-th SNP for all individuals; and is the effect of the j-th SNP within the i-th window. Genomic windows of 20 consecutive SNPs that explained more than 0.5% of the total GV observed in TS and US for mature and young Canadian Angus cows were used to identify candidate genes. Chromosomal distribution was visualized by creating Manhattan plots for MTS, MUS, YTS, and YUS using R 3.6.2 package “ggplot2” as per (Wickham, 2009).

Gene annotation and enrichment analyses

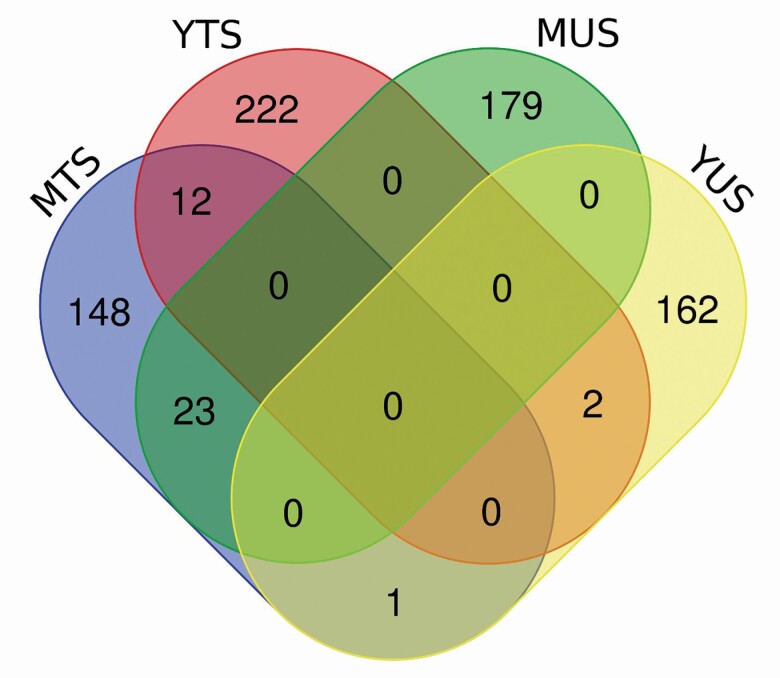

Identification of annotated protein-coding genes within or in genomic proximity to each window was performed by referencing B. taurus genome ARS-UCD1.2 assembly through the Ensembl Biomart Martview application (http://www.ensembl.org). Commonalities between traits were identified (Figure 2). Furthermore, gene ontology, functional enrichment, and pathway mapping of the genes identified within the genomic windows of significance for the traits were performed using a web-based bioinformatics application for functional analyses of genes and interactive building of biological pathways Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA; Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, CA; http://www.ingenuity.com).

Figure 2.

Venn diagram of genes identified within 20 consecutive SNP windows explaining more than 0.5% variance for TS and US in young and mature Canadian Angus cows.

Results and Discussion

Descriptive statistics

Least square means of TS and US (Table 2) were significantly (unpaired Student’s t-test, P-value > 0.05) lower for mature cows (parity ≥ 4) than young cows (parities 1 and 2). This was consistent with observations by Arthur et al. (1992) who reported the greatest incidence of poor udder structure in cows ≥ 6 yr (typically parity 4 and older). As well, Bunter et al. (2013) reported that poorly supported udders and large bottle-shaped teats were more frequently observed in cows of higher parity, and thus the authors concluded that both TS and US deteriorate with parity.

Table 2.

Least square means of TS and US in Canadian Angus cows

| ALL1 | Young2 | Mature3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LSM4 TS (mean error) | 6.52 (1.02) | 6.90 (0.91) | 6.10 (1.08) |

| LSM US (mean error) | 6.53 (1.06) | 7.08 (0.92) | 5.84 (1.16) |

1All, cows scored in parity 1 to 13.

2Young, cows scored in parity 1 and 2.

3Mature, cows scored in parity ≥ 4.

4LSM, least square means.

Estimation of variance components

Estimates of additive GV, variance due to environment, and heritability are presented in Table 3. Estimates of heritability ranged from 0.27 to 0.45, indicating opportunities to select for improved TS and US, and were consistent with previous estimates; Bradford et al. (2015) estimated a similar heritability for US (0.28, SE = 0.01) and for TS (0.32, SE = 0.01) using teat and udder records from American Hereford cows scored according to the BIF scoring guideline. Similarly, MacNeil and Mott (2006) estimated an US heritability for the Line 1 Hereford population at Fort Keogh Livestock and Range Research Laboratory, Miles City, MT, of 0.23 (0.05). It is noteworthy that estimates of heritability of TS and US in young cows were higher than estimates of heritability of TS and US in mature cows.

Table 3.

Estimates of genetic parameters for TS and US in Canadian Angus cows, ALL, young (parities 1 and 2), and mature (parity 4+)

| ALLTS1 | ALLUS2 | YTS | YUS | MTS | MUS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| σ 2a ± PSD2 | 0.36 (0.04) | 0.39 (0.05) | 0.29 (0.06) | 0.40 (0.07) | 0.34 (0.09) | 0.43 (0.11) |

| σ 2e ± PSD2 | 0.76 (0.04) | 0.78 (0.04) | 0.63 (0.06) | 0.49 (0.06) | 0.92 (0.08) | 0.95 (0.09) |

| h 2 ± PSD2 | 0.32 (0.03) | 0.33 (0.04) | 0.32 (0.07) | 0.45 (0.07) | 0.27 (0.07) | 0.31 (0.07) |

1ALLTS, teat score using all cows (parity 1 to 13).

2ALLUS, udder score using all cows (parity 1 to 13).

The estimate of genotypic correlation between MTS and YTS (Table 4) was high at 0.87 (0.13) whereas that between MUS and YUS was lower yet moderate at 0.40 (0.17). US may be more susceptible to environmental influences compared with TS as parity increases. It is also possible that the scale of change in US is larger and, therefore, more perceptible to producers. While the reported estimates may be inflated due to the relatively small number of TS and US available at this time, the genetic correlations found for the traits between the two cow age groups here suggest that scores obtained for young cows will promote genetic progress for TS and US and thus cow longevity. However, based on the estimates of variance parameters (Table 3), we inferred that multi-trait models may result in more accurate genetic evaluation, and continued collection of TS and US in subsequent parities would be of value.

Table 4.

Estimates of genetic correlations between TS and US in young Canadian Angus cows (parities 1 to 2) and mature Canadian Angus cows (parity 4+)

| Genetic correlation | |

|---|---|

| MTS YTS (PSD) | 0.87 (0.13) |

| MUS YUS (PSD) | 0.40 (0.17) |

Genome-wide association studies

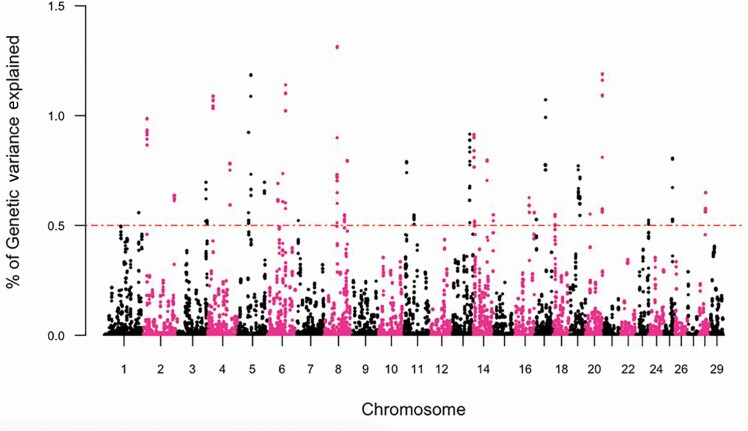

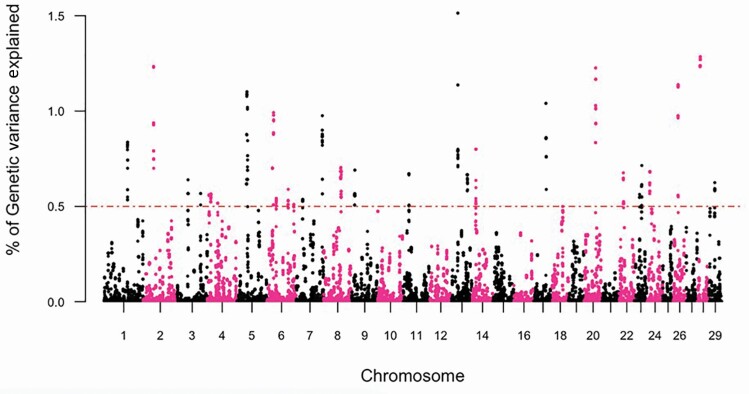

The GWAS, and subsequent gene enrichment and network analysis, was used to further explore trait differences and commonalities between the two cow age groups. There were no major loci (explaining more than 5% GV) identified suggesting that the traits are essentially polygenic. However, using WssGWAS, 36 and 30 genomic windows of 20 consecutive SNPs, which explained more than 0.5% GV for YTS and YUS, were identified. For TS and US in mature cows, 31 and 32 genomic windows explained more than 0.5% GV (Table 5). In total, these windows explained 21.66% to 27.42% of the GV observed in YTS, YUS, MTS, and MUS. Manhattan plots were used for each trait (Figures 3–6) to illustrate chromosome location and the percentage of GV explained by each SNP window. However, as noted above, these estimates may be inflated due to the relatively limited size of the data. Genomic windows on chromosomes BTA4, 5, 6, 8, 17, and 20 explained more than 1% GV for YTS. Furthermore, windows on BTA1, 4, and 18 explained more than 1% GV for MTS. In addition, windows on BTA2, 5, 14, 19, and 27 explained more than 1% GV for YUS. Finally, windows on BTA2, 5, 13, 17, 20, 26, and 28 explained more than 1% GV for MUS. Chromosome number and start and end coordinates were used for gene annotation of protein-coding genes within genomic windows that explained more than 0.5% of GV. In total, 165 to 237 genes were identified within the genomic windows using the B. taurus genome ARS-UCD1.2 assembly in the Ensembl Biomart Martview for reference (Table 5). The number of genes identified in common for the four traits is shown in Figure 2. A total of 12 genes were common for TS in young and mature cows, and no genes were found to be common for US in young and mature cows. Two genes were in common between TS and US in young cows and 23 genes were common for TS and US in mature cows. Despite genetic correlations of 0.87 (0.13) and 0.40 (0.17) for TS and US between the two age groups of cows, relatively few common SNP windows, and thus annotated genes, were identified in the present study using WssGWAS. Estimates of genetic correlation can be driven by common genes or by genes inherited together; thus, the estimates of genetic correlation for TS, and particularly US, may be driven by genetic regions that are closely linked. It is also possible that the high proportion of genetic variation explained by the WssGWAS results is an overestimation due to the relatively limited size of this study. This may be resolved as the quantity and quality of data increase. A greater density of SNP markers may also improve this aspect of the analysis and may show more regions in common between the traits.

Table 5.

Number of genomic windows of 20 consecutive SNPs found to explain more an 0.5% variance for TS and US in young and mature Canadian Angus cows, the total amount of variance explained by the windows, and gene annotation of protein-coding genes

| YTS | YUS | MTS | MUS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of SNP windows1 explaining > 0.5% variance | 36 | 30 | 31 | 32 |

| Number of genes identified2 within genomic windows1 | 237 | 165 | 184 | 202 |

| Total % variance explained by SNP windows1 | 27.42% | 21.66% | 24.07% | 25.57% |

1SNP windows with 20 consecutive SNPs.

2Using Ensembl (www.ensembl.org/) ARS-UCD1.2 reference.

Figure 3.

Manhattan plot depicting the percent variance explained by 20 consecutive SNP windows in TS within young (parities 1 and 2) Canadian Angus cows.

Figure 6.

Manhattan plot depicting the percent variance explained by 20 consecutive SNP windows in US within mature (parity ≥ 4) Canadian Angus cows.

Figure 4.

Manhattan plot depicting the percent variance explained by 20 consecutive SNP windows in TS within mature (parity ≥ 4) Canadian Angus cows.

Figure 5.

Manhattan plot depicting the percent variance explained by 20 consecutive SNP windows in US within young (parities 1 and 2) Canadian Angus cows.

Gene annotation and enrichment studies

In order to gain further insights into the underlying biology and genetic architecture of the traits in the two cow age groups, gene annotation and enrichment were performed. Chromosome number and start and end coordinates for each window that explained more than 1.0% of GV in YTS, YUS, MTS, and MUS, respectively, are presented in Tables 6–9 (Supplementary Tables S1–S4 depict the same information but for all windows that explained more than 0.5% GV in the traits). The tables also list protein-coding genes identified in each window using the B. taurus genome ARS-UCD1.2 assembly in the Ensembl Biomart Martview for reference. Biological network and pathway analysis performed using IPA provided information for discussion of the different genetic contributions toward the traits in the two groups of cows (Figure 2).

Table 6.

Chromosome, start and end coordinates, percentage variance explained, and annotated protein-coding genes within for 20 SNP consecutive genomic windows found to be associated with TS in young (parities 1 and 2) Canadian Angus cows

| SNP window2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr1 | Start, bp | End, bp | Var3 | Annotated genes |

| 8 | 51,375,774 | 52,189,823 | 1.31 | PCSK5 |

| 20 | 67,952,434 | 68,768,871 | 1.19 | DEPDC1B |

| 5 | 53,259,627 | 54,421,524 | 1.19 | LRRC10, CCT2, FRS2, YEATS4, LYZ1, LYSB, LYZ2, and LYZ3 |

| 6 | 72,614,036 | 73,770,751 | 1.14 | ADGRA3 and GBA3 |

| 4 | 21,671,524 | 22,675,392 | 1.09 | ETV1 and DGKB |

| 17 | 41,712,693 | 42,506,929 | 1.07 | ARFIP1 and FBXW7 |

1Chr, chromosome number.

2Windows with 20 consecutive SNPs based on ARS-UCD1.2.

3Var, percentage of additive GV explained by each SNP window.

Table 9.

Chromosome, start and end coordinates, percentage variance explained, and annotated protein-coding genes within for 20 SNP consecutive genomic windows found to be associated with US in mature Canadian Angus cows

| SNP window2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr1 | Start, bp | End, bp | Var3 | Annotated genes |

| 13 | 25,323,926 | 26,176,809 | 1.514 | KIAA1217, ARHGAP21, ENKUR, THNSL1, and GPR158 |

| 28 | 11,234,652 | 12,623,710 | 1.285 | |

| 2 | 41,050,502 | 41,713,970 | 1.234 | KCNJ3 and GALNT13 |

| 20 | 46,271,539 | 47,139,491 | 1.226 | CDH9 |

| 26 | 19,479,245 | 20,420,930 | 1.138 | PYROXD2, HPS1, HPSE2, CNNM1, and GOT1 |

| 5 | 39,886,350 | 40,517,551 | 1.101 | CNTN1 and LRRK2 |

| 17 | 47,953,494 | 49,434,995 | 1.040 | TMEM132D, GLT1D1, SLC15A4, and TMEM132C |

| 5 | 41,937,245 | 42,874,271 | 1.019 | CPNE8 and PTPRR |

1Chr, chromosome number.

2Windows with 20 consecutive SNPs based on ARS-UCD1.2.

3Var, percentage of additive GV explained by each SNP window.

Table 7.

Chromosome, start and end coordinates, percentage variance explained, and annotated protein-coding genes within for 20 SNP consecutive genomic windows found to be associated with TS in mature Canadian Angus cows

| SNP window2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr1 | Start, bp | End, bp | Var3 | Annotated genes |

| 1 | 133,734,123 | 134,475,334 | 1.53 | EPHB1 |

| 18 | 21,817,413 | 22,652,288 | 1.27 | RBL2, AKTIP, RPGRIP1L, FTO, and IRX3 |

| 4 | 65,712,709 | 66,424,351 | 1.22 | GARS1, GGCT, NOD1, ZNRF2, MTURN, PLEKHA8, FKBP14, SCRN1, and WIPF3 |

| 14 | 24,484,165 | 25,215,941 | 1.00 | UBXN2B, CYP7A1, SDCBP, NSMAF, and TOX |

1Chr, chromosome number.

2Windows with 20 consecutive SNPs based on ARS-UCD1.2.

3Var, percentage of additive GV explained by each SNP window.

Table 8.

Chromosome, start and end coordinates, percentage variance explained, and annotated protein-coding genes within for 20 SNP consecutive genomic windows found to be associated with US in young (parities 1 and 2) Canadian Angus cows

| SNP window2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr1 | Start, bp | End, bp | Var3 | Annotated genes |

| 14 | 25,082,860 | 25,744,989 | 1.23 | TOX |

| 19 | 47,360,374 | 48,382,910 | 1.03 | TANC2, CYB561, ACE, KCNH6, DCAF7, TACO1, MAP3K3, LIMD2, and STRADA |

| 5 | 12,337,088 | 13,892,317 | 1.03 | TMTC2 |

| 27 | 24,152,004 | 25,059,442 | 1.01 | LONRF1, PRAG1, CLDN23, and MFHAS1 |

1Chr, chromosome number.

2Windows with 20 consecutive SNPs based on ARS-UCD1.2.

3Var, percentage of additive GV explained by each SNP window.

Genes identified for TS in young Canadian Angus cows were primarily linked to pathways involved in cell morphology, embryonic development, organ development, and tissue development. For US in young cows, primary pathways identified were cell-to-cell signaling, hematological system development, cellular growth and development, and organ morphology. Inspection of these pathways suggested that the biological architecture of these traits is centered around growth and development. Conversely, pathways linked to genes identified for TS and US in mature cows include not only cellular and organ development but also tissue development, inflammatory response, lipid metabolism, nervous system development and function, and reproductive system development and function.

A primary objective of this study was to elucidate biological and genetic similarities and differences between TS and US in young and mature Canadian Angus cows. Based on WssGWAS results, there were significant underlying differences between the traits in the two age strata. Pathway analysis results from this study suggested that there were inherent differences in TS and US between young and mature cows. Pathways associated with organ growth and development seemed to be more pertinent to the traits in young females. Teat and udder development begins early in gestation, through puberty and the first two parturitions at least. The observed shift of primary pathways associated with TS and US in mature cattle to molecular transport and lipid metabolism may again be expected as it reflects a greater importance of milk production and functionality of the mammary gland in older cows. Further network analysis identified processes that support the maintenance of the gland both structurally and immunologically. This is consistent with previous reports of poor TS and US being associated with increased parity.

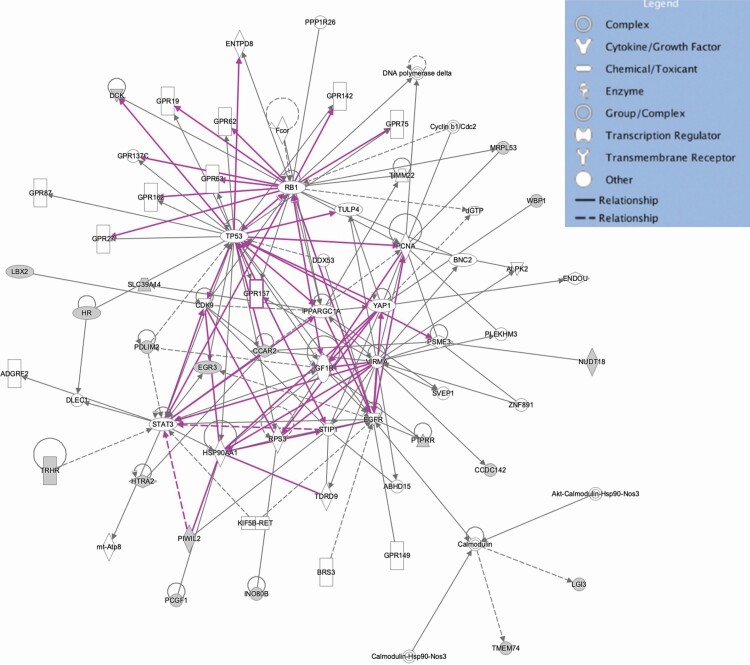

However, within this study, there were also some commonalities between the two cow age groups. The 12 genes in common for TS in both young and mature cows (INO80B, LBX2, TLX2, LOXL3, MOGS, HTRA2, WBP1, AUP1, DQX1, PCGF1, MRPL53, and CCDC142) were linked primarily to tissue and organ morphology. For example, LBX2 regulates cell proliferation and has been linked with the development of muscle fibers and muscle morphology. Also, vascular modeling is imperative for the development of healthy mammary glands. It was, therefore, interesting that INO80B that encodes a subunit of an adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-dependent chromatin remodeling complex that has a role in ATPase activity was thought to induce growth and cell cycle arrest and has previously been linked to defective coronary vascularization in mice (Rhee et al., 2018). Two overlapping gene networks linked to these common genes are shown in Figure 7. Several of the 12 genes common to TS in young and mature cows have also been associated with mammary health and function in cattle. For example, INO80B was reported to be associated with milk yield in Holstein-Friesian cows (Carvalheira et al., 2014) and TLX2 was also associated with milk traits. A mannosyl-oligosaccharide glucosidase is encoded by MOGS. In humans, defects in this gene are a cause of hypotonia and generalized edema and may be relevant to the maintenance of mammary structure. The product of HTRA2 is involved in intrinsic apoptotic signaling pathways in response to DNA damage and may be a critical response to mammary exposure to extreme temperatures. Finally, the product of DQX1 was also reported to be associated with lactation persistency in Canadian Holstein cattle (Do et al., 2017). Using fine mapping, Schulman et al. (2009) reported an association between AUP1 and mastitis resistance in three Nordic dairy breeds. It was noteworthy, that despite common networks and biological pathways, no genomic regions, and thus specific genes, were identified in common for US between the two age groups of cows, despite a moderate genetic correlation. Although the primary source of genetic correlation between related traits or repeated records for the same trait is pleiotropy, GWAS results from this study suggested that TS and US in young cows were driven by distinct genomic regions and biological pathways.

Figure 7.

Overlapping schematic of two biological pathways of cellular function and maintenance and cellular growth and proliferation linked to the 12 genes identified in common for TS in both young and mature Canadian Angus cows.

Only two genes (TRHR and TMEM74) were identified as common between YTS and YUS. TRHR encodes for a thyrotropin-releasing hormone receptor involved with thyroid hormone secretion and related metabolic pathways, and TMEM74, encoding transmembrane protein 74, is involved in endothelial function. These genes were in relatively strong linkage disequalibrium on BTA28. In contrast, the WssGWAS results suggested that as cows mature there was an increasing common genetic influence on TS and US, as 23 genes were identified as common to both MTS and MUS. Pathways linked to these 23 genes included those involved in connective tissue disorders, inflammatory disease, cardiovascular system development, and reproductive system development and function. It is, therefore, likely that maintenance of good TS and US as cows mature was dependent on some of the same pathways involved in the massive remodeling that occurs during each lactation as well as environmental stressors, such as suckling, mastitis, and injury. Tissue morphology and repair may be vital to maintain good TS and US throughout the productive lifetime of a cow. Bradford et al. (2015) reported repeatability estimates of 0.44 (0.01) for TS and 0.47 (0.01) for US in American Hereford cattle and suggested that producers should continue evaluating these traits repeatedly. This is supported by the GWAS results, gene enrichment, and pathway analysis from this study that suggest distinct genetic and biological mechanisms drive these traits in young and mature cows.

Conclusions

Genetic selection for improved TS and US presents an opportunity to improve production efficiencies and animal health and wellness and decrease antibiotic use as related to udder health. Mammary traits, expressed annually and/or per lactation and when following best practice, are typically assessed at calving. As the Canadian Angus database for TS and US on cows grows, it is important to validate the use of repeated traits models for the genetic evaluation of these traits. In particular, TS and US for young cows are more frequent than data from mature cows as the latter are culled at a higher rate. Estimated genetic correlations for TS and US between the two cow age groups suggest that producers should be encouraged to score mammary structure annually throughout the production lifetime of each cow. Thus, using recorded scores from both cow age groups in multi-trait models that account for genetic correlations between the traits will add accuracy to the evaluation of the TS and US in Canadian Angus cattle and, therefore, expedite genetic improvement for these traits. Additional submissions of TS and US for Canadian Angus cows will allow for further exploration of the underlying genetics and biological pathways driving the traits within this population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The financial support for this study was received from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, the Alberta Livestock and Meat Agency (now Alberta Agriculture and Forestry), and the Canadian Angus Association (CAA). This study would not have been possible without the cooperation of Canadian Angus producers and genetic evaluation expertise from the Canadian Beef Breeds Council, Calgary, Alberta.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CG

contemporary groups

- GEBV

genomically enhanced estimated breeding value

- GV

genetic variance

- IPA

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis

- MTS

mature teat score (on cows in parity ≥ 4)

- MUS

mature udder score (on cows in parity ≥ 4)

- PSD

posterior SD

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- ssGBLUP

single step genomic best linear unbiased prediction

- TS

teat score

- US

udder score

- WssGWAS

weighted single step genome-wide association study

- YTS

young teat score (on cows in parity 1 to 2)

- YUS

young udder score (on cows in parity 1 to 2)

Conflict of interest statement

All authors confirm that there were no actual or potential conflicts of interest that may affect their ability to objectively present or review research or data.

Literature Cited

- Aguilar, I., Misztal I., Johnson D. L., Legarra A., Tsuruta S., and Lawlor R. J.. . 2010. Hot Topic: A unified approach to utilize phenotypic, full pedigree, and genomic information for genetic evaluation of Holstein final score. J. Dairy Sci. 93:743–752. doi: 10.3168/jds.2009-2730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur, P. F., Makarechian M., Berg R. T., and Weingardt R.. . 1992. Reasons for disposal of cows in a purebred Hereford and two multibreed synthetic groups under range conditions. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 72:751–758. doi: 10.4141/cjas92-087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal, W., Notter D., and Akers R.. . 1990. Techniques for estimation of milk yield in beef cows and relationships of milk yield to calf weight and postpartum reproduction. J. Anim. Sci. 68: 937–943. doi: 10.2527/1990.684937x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beef Improvement Federation . BIF. 2016. Guidelines for uniform beef improvement programs. 9th ed. Available from http://www.beefimprovement.org, accessed January 15, 2015.

- Bradford, H. L., Moser D. W., Minick Bormann J., and Weaber R. L.. . 2015. Estimation of genetic parameters for udder traits in Hereford cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 93:2663–2668. doi: 10.2527/jas.2014-8858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunter, K. L., Johnston D. J., Wolcott M., and Fordyce G.. . 2013. Factors associated with calf mortality in tropically adapted beef breeds managed in extensive Australian production systems. Anim. Prod. Sci. 54:25–36. doi: 10.1071/AN12421 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burrow, H. M. 2001. Variances and covariances between productive and adaptive traits and temperament in a composite breed of tropical beef cattle. Livest. Prod. Sci. 70:213–233. doi: 10.1016/S0301-6226(01)00178-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalheira J, Salem MMI, Thompson G, Chen SY, Beja-Pereira A. 2014. Genome-wide association study for milk and protein yields in Portuguese Holstein cattle. Proceedings of the 10th World Congress of Genetics Applied to Livestock Production Genome-Wide Association Study for Milk and Protein Yields in Portuguese Holstein Cattle; August 17 to 22, 2014; Champaign (IL): American Society of Animal Science. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, E. V., Ventura H. T., Figueiredo E. A. P., Silva F. F. e., Gioria L. S., Godinho R. M., M. D. V. de Resende, Lopes P. S.. . 2016. Multi-trait and repeatability models for genetic evaluation of litter traits in pigs considering different farrowings. Rev. Bras. de Saude e Prod. Anim. 17:666– 676. doi: 10.1590/s1519-99402016000400010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeGroot, B. J., Keown J. F., Van Vleck L. D., and Marotz E. L.. . 2002. Genetic parameters and responses of linear type, yield traits, and somatic cell scores to divergent selection for predicted transmitting ability for type in Holsteins. J. Dairy Sci. 85:1578–1585. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(02)74227-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do, D. N., Bissonnette N., Lacasse P., Miglior F., Sargolzaei M., Zhao X., and Ibeagha-Awemu E. M.. . 2017. Genome-wide association analysis and pathways enrichment for lactation persistency in Canadian Holstein cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 100:1955–1970. doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-11910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch, J. E. 2010. The use of teat-size measurements or calf weaning weight as an aid to selection against teat defects in cattle. Anim. Sci. J. 35:127–133. doi: 10.1017/S0003356100000891 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil, M. D., and Mott T. B.. . 2006. Genetic analysis of gain from birth to weaning, milk production, and udder conformation in Line 1 Hereford cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 84:1639–1645. doi: 10.2527/jas.2005-697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, J. J., Allen O. B., and Martin S. W.. . 1992. Culling practices of Ontario cow-calf producers. Can. J. Vet. Res. 56:56–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee, M., and Earley B.. . 2019. Review: Passive immunity in beef-suckler calves. Animal 13:810–825. doi: 10.1017/S1751731118003026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misztal, I., Tsuruta S., Lourenco D., Aguilar I., Legarra A., and Vitezica Z.. . 2014. Manual for BLUPF90 family of programs. Available from http://nce.ads.uga.edu/wiki/lib/exe/fetch.php?media=blupf90_all1.pdf. Accessed May 1, 2016.

- Morrill, K. M., Conrad E., Lago A., Campbell J., Quigley J., and Tyler H.. . 2012. Nationwide evaluation of quality and composition of colostrum on dairy farms in the United States. J. Dairy Sci. 95:3997–4005. doi: 10.3168/jds.2011-5174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrode, R. 2005. Linear models for the prediction of animal breeding values. Wallingford (UK): CABI. [Google Scholar]

- Paape, M. J., Duenas M. I., Wettemann R. P., and Douglass L. W.. . 2000. Effects of intramammary infection and parity on calf weaning weight and milk quality in beef cows. J. Anim. Sci. 78:2508–2514. doi: 10.2527/2000.78102508x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson Waller, K., Persson Y., Nyman A.-K., and Stengärde L.. . 2014. Udder health in beef cows and its association with calf growth. Acta Vet. Scand. 56–64:9. doi: 10.1186/1751-0147-56-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee, S., Chung J. I., King D. A., D′amato G., Paik D. T., Duan A., Chang A., Nagelberg D., Sharma B., Jeong Y., . et al. 2018. Endothelial deletion of Ino80 disrupts coronary angiogenesis and causes congenital heart disease. Nat. Commun. 9:368. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02796-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samoré, A. B., Rizzi R., Rossoni A., and Bagnato A.. . 2010. Genetic parameters for functional longevity, type traits, somatic cell scores, milk flow and production in the Italian Brown Swiss. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 9:e28. doi: 10.4081/ijas.2010.e28 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute . 2015. Base SAS 9.4 Procedures guide. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Schulman, N. F., Sahana G., Iso-Touru T., Lund M. S., Andersson-Eklund L., Viitala S. M., Värv S., Viinalass H., and Vilkki J. H.. . 2009. Fine mapping of quantitative trait loci for mastitis resistance on bovine chromosome 11. Anim. Genet. 40:509–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2009.01872.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T., Glenn C. D., White R. C., and White W. E.. . 2017. Evaluation of udder and teat scores in beef cattle and the relationship to calf performance. J. Anim. Sci. 95(supplement1):2. doi: 10.2527/ssasas2017.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- VanRaden, P. M. 2008. Efficient methods to compute genomic predictions. J. Dairy Sci. 91:4414–4423. doi: 10.3168/jds.2007-0980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitezica, Z. G., Aguilar I., Misztal I., and Legarra A.. . 2011. Bias in genomic predictions for populations under selection. Genet. Res. (Camb). 93:357–366. doi: 10.1017/S001667231100022X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H., Misztal I., Aguilar I., Legarra A., Fernando R. L., Vitezica Z., Okimoto R., Wing T., Hawken R., and Muir W. M.. . 2014. Genome-wide association mapping including phenotypes from relatives without genotypes in a single-step (ssGWAS) for 6-week body weight in broiler chickens. Front. Genet. 5:134. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H., Misztal I., Aguilar I., Legarra A., and Muir W. M.. . 2012. Genome-wide association mapping including phenotypes from relatives without genotypes. Genet. Res. (Camb). 94:73–83. doi: 10.1017/S0016672312000274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts, J. L., Pankey J. W., Oliver W. M., Nickerson S. C., and Lazarus A. W.. . 1986. Prevalence and effects of intramammary infection in beef cows. J. Anim. Sci. 62:16–20. doi: 10.2527/jas1986.62116x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. 2009. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York (NY): Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Wolc, A., Arango J., Settar P., O′Sullivan N. P., and Dekkers J. C.. . 2017. Repeatability vs. multiple-trait models to evaluate shell dynamic stiffness for layer chickens. J. Anim. Sci. 95:9–15. doi: 10.2527/jas.2016.0618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.