This decision aid is for clinicians for discussion of treatment options for patients living with neuropathic pain. It is derived from our accompanying systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs; e130).1 Effectiveness data were generated from RCTs comparing active treatment to control. The evidence focuses on the proportion of patients achieving a clinically meaningful reduction in pain, generally defined as a 30% or more reduction in pain.

How was this tool was developed?

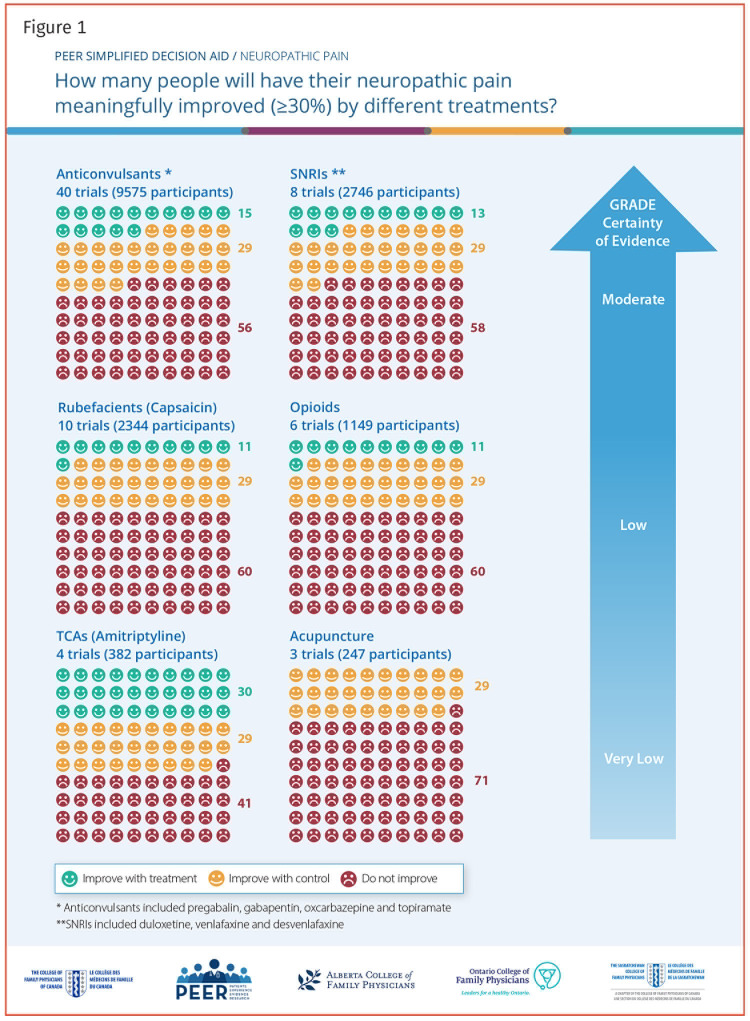

Icon arrays were developed using risk ratio estimates from meta-analyses of patients attaining a clinically meaningful improvement in pain. The control response rate was standardized to 29%, the approximate control response rate averaged for all included studies. The risk ratio for each intervention was applied to the average 29% control rate to attain the estimated benefit of that intervention. Standardizing control rates allows for easier comparison of estimated benefits of differing interventions. The estimates are from placebo-controlled trials and are not direct comparisons, so differences between interventions are approximations with some uncertainty.

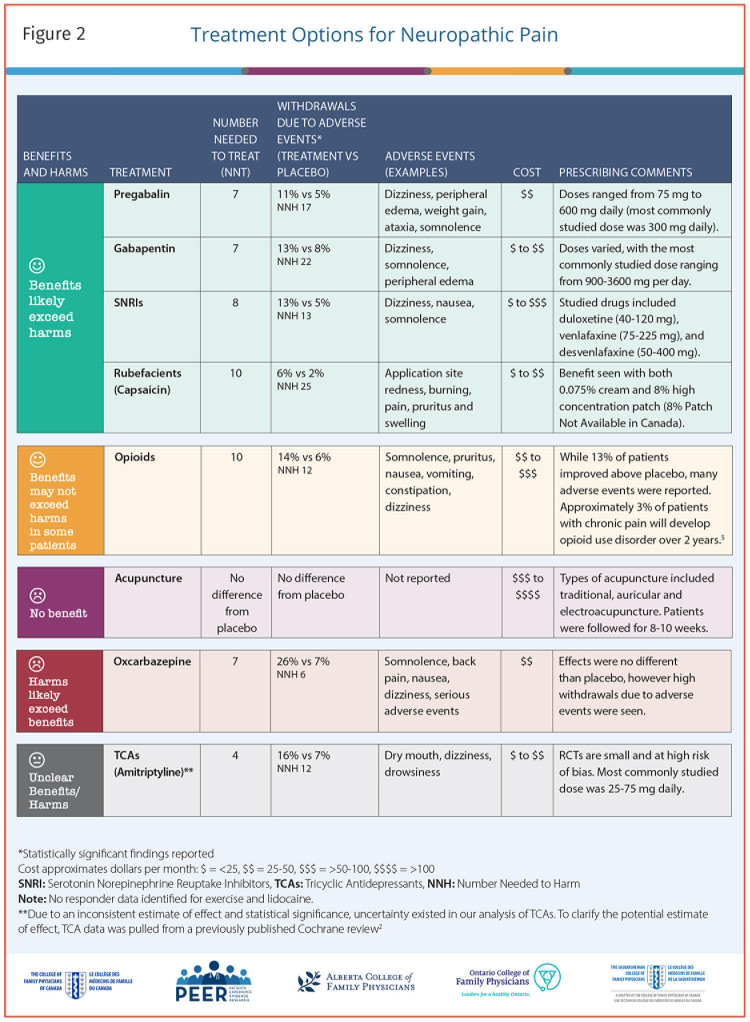

Our systematic review identified the best available evidence for most interventions.1 For anticonvulsant medications, we included evidence for gabapentin, pregabalin, oxcarbazepine, and topiramate, with 90% of the studies examining gabapentin or pregabalin. All 4 anticonvulsant medications demonstrated similar efficacy; more adverse events were seen with oxcarbazepine and topiramate. For serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, we included duloxetine, venlafaxine, and desvenlafaxine, with 75% of the literature focused on duloxetine. Efficacy and adverse events were similar, regardless of the drug. To improve quality, we excluded partially reported crossover trials. This worked for other therapies, but in the case of tricyclic antidepressants, it left only 2 very low-quality RCTs with conflicting results. For clarity, we used a recent systematic review of tricyclic antidepressants2 and meta-analyzed responder data, including partially reported crossover trials (meta-analysis available from authors on request). We did not identify any relevant RCTs for exercise or topical lidocaine.

The decision aid

The tool is a 1-page summary (2-sided) of estimated effectiveness of treatment options for neuropathic pain; a printable version is available from CFPlus.* Accompanying the icon array (Figure 1)3 is a blue arrow that indicates the level of evidence associated with each of the listed interventions, based on the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) working group criteria,3 which reflects confidence in risk ratio estimates. Figure 21,2,4 includes classification of therapies by benefits and harms, withdrawals due to adverse events, typical adverse events, prescribing considerations, and estimated costs.

Figure 1.

PEER SIMPLIFIED DECISION AID / NEUROPATHIC PAIN

How many people will have their neuropathic pain meaningfully improved (≥30%) by different treatments?

Figure 2.

Treatment Options for Neuropathic Pain

We did not report on cannabinoids for neuropathic pain, as we have done so before.5 While this previous icon array does address neuropathic pain, it includes other types of neuropathic pain not included in this analysis, so effect estimates are not directly comparable. The tool is not a guideline, and the evidence was not assessed by an independent guideline committee. Information presented here will be combined with similar systematic reviews and tools on other types of chronic pain to inform future guideline development.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Competing interests

None declared

Easy-to-print versions of Figures 1 and 2 are available at www.cfp.ca. Go to the full text of the article online and click on the CFPlus tab.

This article is eligible for Mainpro+ certified Self-Learning credits. To earn credits, go to www.cfp.ca and click on the Mainpro+ link.

This article has been peer reviewed.

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro de mai 2021 à la page e111.

References

- 1.Falk J, Thomas B, Kirkwood J, Korownyk CS, Lindblad AJ, Ton J, et al. . PEER systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Management of neuropathic pain in primary care. Can Fam Physician 2021;67:e130-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore RA, Derry S, Aldington D, Cole P, Wiffen PJ.. Amitriptyline for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;(7):CD008242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A, editors. GRADE handbook: introduction to GRADE handbook. GRADE Working Group; 2013. Available from: guidelinedevelopment.org/handbook. Accessed 2021 Mar 26. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moe S, Allan GM.. What is the incidence of iatrogenic opioid use disorder? Tools for Practice #240. Edmonton, AB: Alberta College of Family Physicians; 2019. Available from: https://gomainpro.ca/wp-content/uploads/tools-for-practice/1563807207_incidenceoudtfp240fv.pdf. Accessed 2021 Mar 26. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allan GM, Ramji J, Perry D, Ton J, Beahm NP, Crisp N, et al. . Simplified guideline for prescribing medical cannabinoids in primary care. Can Fam Physician 2018;64:111-20 (Eng), e64-75 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.