Abstract

Background:

The spending on digital healthcare solutions is estimated to reach EUR 232 billion by 2025. Digital healthcare platforms are making transformative changes to conventional healthcare processes which can provide many beneficial improvements for both citizen and government provision to society. These benefits are obvious during pandemics such as Covid-19, when most healthcare services are offered through digital means.

Objective:

The objective of this study is to measure the role of trust and information quality when using digital healthcare platforms. These constructs are integrated with the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) to provide a better understanding of the consumer perspective regarding the use of digital healthcare platforms.

Methods:

Online structured self-administered questionnaire was utilized to collect the data. A sample consisting of 249 respondents participated in the questionnaire. Descriptive analysis was used to characterize the attributes of participants, and other statistical tests were conducted to ensure the reliability and validity of the survey. The model of the study was evaluated using Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) to explain the extent of the relationship among latent variables.

Results:

The study determined that facilitating conditions (t=0.233, p=0.023) and trust (t=0.324, p=0.005) had a significant impact on consumers’ behavioral intention of using such platforms during Covid-19 pandemic.

Conclusion:

This study highlighted the importance of facilitating conditions and trust factors for healthcare consumers of digital healthcare platforms especially during the pandemic time.

Keywords: Digital healthcare platforms, E-health, Consumer Health informatics, Trust, Saudi Arabia

1. BACKGROUND

The rising Covid-19 pandemic has created situations of uncertainty in medical practices and unreliable information which impacted healthcare systems around the world in many ways. The rapidly increasing numbers of confirmed cases and deaths have put healthcare systems under pressure. At the time of publication, there are more than 125 million confirmed cases and more than 2 million deaths due to Covid-19 across more than 213 countries and territories around the world (1). The rapid spread of Covid-19 causes governments to take numerous actions to stop or slow the spread of this contagious disease, such as complete and partial lockdowns, severe travel restrictions, and forced quarantines (2). Many ICT tools and applications have been implemented to control the outbreak so that it remains manageable. The use of digital healthcare solutions requires more informative and up to date quality information with a high degree of trust between the consumers and healthcare service providers, especially with this level of uncertainty around Covid-19.

This study will measure the role of trust and information quality when using digital healthcare platforms. These constructs will be integrated with the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) (3) to provide a better understanding of the consumer perspective regarding the use of digital healthcare platforms. Integrating these constructs with the UTAUT model could provide insight into consumer opinions about digital healthcare platforms. Only a few researchers have addressed these factors together when studying consumer acceptance of digital healthcare solutions (4).

Digital healthcare platforms in this study are defined as collections of applications and technologies used to support the delivery of healthcare services (5). A study estimated the spending on digital healthcare solutions to reach EUR 232 billion by 2025 (6). This paper also deals with the user of digital healthcare platforms as a consumer rather than as a patient for many reasons. First, not all users of digital healthcare platforms are patients, as some of them may simply ask about general health information such as diet, exercise, sleeping patterns, or similar information (7). Second, there is a movement toward empowering the consumer side of healthcare services by allowing consumers to conduct certain healthcare activities that were once the privilege of health professionals (8). A study indicated that three-quarters of its participants expected that the healthcare consumers will be the owner of their health data (6).

Although user acceptance is a mature field in information technology studies (4, 8), most of the studies were conducted in normal situations where there are alternative tools or systems of using information technology solutions. Additionally, for some consumers, this is the first time that they are using such systems, which requires studying their behavioral intention (7).

Saudi Arabia is one of the biggest countries in Asia with a total area of about 2.15 million km2 and a total population of 34.77 million people (9). The healthcare system in the country relies on governmental healthcare services where the Ministry of Health (MoH) is responsible for providing healthcare services free of charge for citizens. There are other governmental bodies and private organizations which provide healthcare services.

Saudi Arabia was selected for this study for many reasons. It has a large geographical area with many rural areas which make the use of digital healthcare services beneficial for the country. The population of the country is young since the majority of Saudi citizens (67%) are young adults (i.e. under 40 years) (10). Saudi Arabia has Mecca and Medina that are special cities for Muslims because it has the two holy mosques and there were about 20 million visitors for the cities during 2019. These reasons make the dealing with the Covid-19 requires special care from the Saudi authorities.

Before the Covid-19 outbreak, Saudi Arabia introduced several initiatives regarding the implementation of digital healthcare projects. The first national e-government strategy was launched in 2005, and it was updated in 2011 (11). Additionally, the Saudi Vision 2030 framework and the National Transformation Program 2020 initiative emphasized the importance of ICT in healthcare systems. There are many ongoing projects, especially for the Ministry of Health, which is the main healthcare provider in the country. Examples of such projects may include automated and standardized systems of primary healthcare centers and integrated hospital information systems for all MoH hospitals (12). However, this ambitious initiative still requires extra time and effort to be achieved because it requires collaboration among different ministries and agencies in the country. There are many examples demonstrate the ongoing efforts to enhance digital healthcare services in the country, which have resulted in a variety of systems and platforms that have been utilized effectively during the Covid-19 pandemic. These technologies can be summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Categories of digital healthcare platforms used in Saudi Arabia during the Covid-19 outbreak.

| Category | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Virtual Healthcare | Remote interaction between consumers and their healthcare teams using any ICT tools | Seha platform |

| Diagnostic Platforms | Help healthcare consumers to identify the possibility of being infected by the Covid-19 virus | Mawid app |

| E-prescription Systems | Allow physicians to fill prescriptions and transfer them electronically to pharmacies | Wasfaty platform |

| Administrative support platforms | Provide online services for administrative purposes | Seha platform and Mawared app |

| Platforms for disseminating information | Are designed to provide information about Covid-19 to spread public awareness. | Covid19.moh.gov.sa |

| Platforms for Quarantined Patients | Offer information to quarantined and positive individuals or those with suspected cases either in their homes or in quarantine areas | Tataman app |

| Tracing and alerting platforms | Track confirmed cases and then alert the public | Tabaud app |

| Social media platforms | Use social media platforms to communicate with residents of a country | LiveWellMOH |

2. OBJECTIVE

The objective of this study is to measure the role of trust and information quality when using digital healthcare platforms. These constructs are integrated with the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) to provide a better understanding of the consumer perspective regarding the use of digital healthcare platforms.

3. METHODS

3.1. Research framework and hypotheses

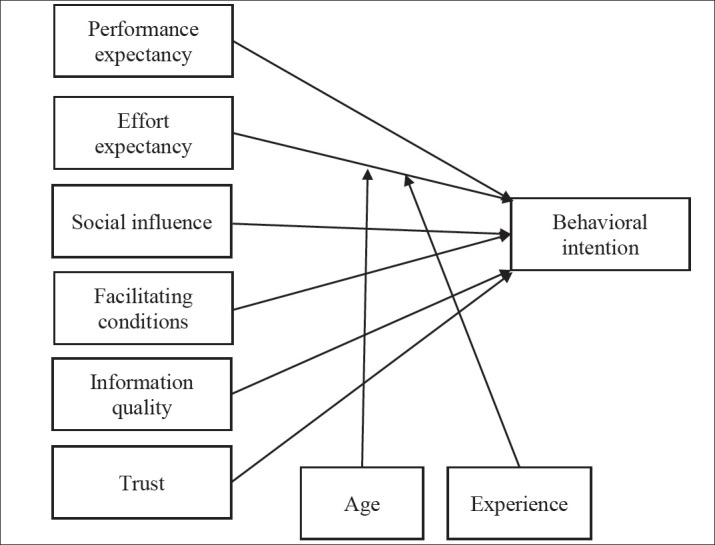

This research aims to develop an understanding of healthcare consumers’ behavioral intentions for using digital healthcare platforms during the Covid-19 pandemic with focus on information quality and trust. The research framework contains the original elements of the UTAUT framework along with information quality and trust elements. The factors in the research framework are:

Effort expectancy

Effort expectancy (EE) is the degree of ease associated with consumer use of a specific technology (3). The possibility that healthcare consumers will use the system is increased if the system is easy to use and it has a user-friendly design (13). Effort expectancy is considered to be a key contributor to behavioral intention related to e-health system use in many studies (8, 14). Many digital healthcare platforms were developed during the Covid-19 pandemic such as track and trace applications however some of them may still require more usability tests. Due to the nature of the pandemic and the urgent need to develop digital healthcare platforms, there was a rush to develop these platforms. So, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 1: Effort expectancy will positively influence behavioral intention for using digital healthcare platforms in Saudi Arabia during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Effort expectancy was found to be moderated by the following factors: experience with using information technologies and age(15) so the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1-a: The influence of effort expectancy on behavioral intention will be moderated by experience.

Hypothesis 1-b: The influence of effort expectancy on behavioral intention will be moderated by age.

Performance expectancy

Performance expectancy (PE) refers to the benefits that are provided to the user due to the usage of certain technologies (15). Digital healthcare platforms can provide many benefits for healthcare consumers, such as understanding of their health status, enabling of self-care, and better management of healthcare activities (8, 16). The use of digital healthcare platforms during the Covid-19 pandemic can enhance the safety of healthcare consumers because it reduces infection rates using digital meeting tools such as Zoom. Many researchers have identified performance expectancy as one of the factors that influence the behavioral intentions of consumers of healthcare (16, 17). Thus, the following hypothesis was introduced:

Hypothesis 2: Performance expectancy will positively influence behavioral intention for using digital healthcare platforms in Saudi Arabia during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Social influence

Social influence (SI) refers to the influence of peers such as family, friends, and partners or media and social media websites (8, 17). This factor is represented as subjective norm in other theoretical frameworks, such as in the extended versions of TAM (3). It indicates that social roles and other beliefs influence the intention of healthcare consumers to use healthcare technologies. Some studies have shown that social influence had an impact on patient intention to use e-health services (17). Social influence can have a strong effect especially in a culture like Saudi Arabi where social ties are strong (18). So, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 3: Social influence will positively influence behavioral intention for using digital healthcare platforms in Saudi Arabia during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Facilitating conditions

Facilitating conditions (FC) cover the availability of resources, knowledge, and support for a particular information system under investigation (15). It also includes compatibility with other technologies that are commonly used by healthcare consumers, such as smartphones (8). The facilitating conditions factor was found to provide an understanding of patients’ perceptions of telehealth services (13,19). So, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 4: Facilitating conditions will positively influence behavioral intention for using digital healthcare platforms in Saudi Arabia during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Information quality

Information quality (IQ) refers to the accuracy, timeliness, and relevance of the information generated by digital healthcare platforms (20). Although having accurate and timely information is important, only a few studies considered the effect of this factor on patient behavioral intention or acceptance of e-health service use (21). Some studies focused on measuring this factor for physicians or healthcare professionals who are using health information systems in hospitals (22). During the Covid-19 pandemic, the information about the infectious disease itself or methods of protection and reducing infection were uncertain which can affect information quality. Thus, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 5: Information quality will positively influence behavioral intention for using digital healthcare platforms in Saudi Arabia during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Trust

Trust (TR) refers to the confidence felt between healthcare consumers and healthcare providers (23). Trust can be measured from a social perspective, which primarily concerns physician–patient relationships (24). It can also be associated with health information and how healthcare providers handle this information (25), which will be considered by the present study. Trust was found in many studies to strongly influence patients’ intention to use digital healthcare platforms (23, 25). During the moment of crisis, trust in provided information of digital healthcare platforms plays a vital role in communicating and acceptance of information from trusted sources (26). So, the following hypothesis was developed:

Hypothesis 6: Trust will positively influence behavioral intention for using digital healthcare platforms in Saudi Arabia during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Figure 1 presents the research model followed during the study.

Figure 1. Research Model.

3.2. Research method

Based on the research model, a questionnaire was developed to study factors identified during the literature review. The questionnaire consists of 34 questions and is divided into 5 parts. The first part acts as a cover letter and a consent form for the questionnaire by providing information about the study and the researcher. The second part is about the use of digital healthcare platforms by participants responding to the questionnaire. This part also includes questions about skills in information technologies to measure the experience level of the participants. The third part contains statements to measure the latent variables of the research model, where a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” is used to assess each construct (See Appendix for more details). The fourth part contains demographic information such as gender, age, and nationality. The fifth part allows the participants to add any comments regarding the study.

This research followed the Moore and Benbasat (27) approach for developing the questionnaire. This approach includes three phases: item construction, questionnaire review, and questionnaire testing.

Regarding item construction, all measurement items were adapted from prior research found in the literature. Then, the questionnaire was evaluated and reviewed by three experienced researchers in health informatics (one professor, one assistant professor, and one health informatics expert with a master’s degree). After assuring the content validity of the questionnaire, a translation from English to Arabic was conducted by the researcher and reviewed by two other experts. Then, the questionnaire was transcribed into an online questionnaire tool and the pilot study was conducted with a small group of users to check timing issues and the usability of the online tool. At each stage, adjustments were made before moving to the next stage. The researcher obtained ethical approval for this research from the Research Ethics Committee at Shaqra University in Saudi Arabia.

The population for this study was comprised of healthcare consumers from various regions in Saudi Arabia. Due to time constraints for conducting the research during the Covid-19 pandemic, the researcher selected the convenience sampling technique because of its popularity in information technology research and its practicality (28, 29). The researcher allowed only participants who use digital healthcare platforms to answer questions related to platform usage. The researcher also used social media websites, especially the accounts related to healthcare and health informatics, to publish the questionnaire to improve participant representativeness (28). This practice can also decrease some of the concerns of the convenience sampling technique (30).

4. RESULTS

A total of 249 respondents voluntarily chose to answer the survey during the period May 30 through July 31, 2020. Of these, 122 respondents (about 49%) had used digital healthcare platforms in Saudi Arabia during the Covid-19 pandemic. Although the respondents who did not use the platforms were excluded from the empirical analyses, they were asked to clarify their reasons for not using the platforms to provide useful information for the study.

4.1. Sample characteristics

The demographic distribution of the respondents is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Sample characteristics of the questionnaire respondents. *Only for participants who reported the use of digital healthcare platforms during Covid-19 pandemic.

| Characteristic | Total Respondents | Participants who reported the use of digital healthcare platforms | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percent | Frequency | Percent | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 173 | 69% | 84 | 69% |

| Female | 76 | 31% | 38 | 31% |

| Total | 249 | 100% | 122 | 100% |

| Nationality | ||||

| Saudi | 235 | 94% | 115 | 94% |

| Non-Saudi | 14 | 6% | 7 | 6% |

| Total | 249 | 100% | 122 | 100% |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–29 | 50 | 20.10% | 16 | 13.1% |

| 30–39 | 114 | 45.80% | 66 | 54.1% |

| 40–49 | 61 | 24.50% | 35 | 28.7% |

| 50–59 | 18 | 7.20% | 4 | 3.3% |

| 60–69 | 5 | 2.00% | 1 | 0.8% |

| 70 or older | 1 | 0.40% | - | - |

| Total | 249 | 100% | 122 | 100% |

| Area of residence in Saudi Arabia | ||||

| Central Province | 144 | 58% | 72 | 59% |

| Western Province | 56 | 23% | 22 | 18% |

| Eastern Province | 22 | 9% | 13 | 10.7% |

| Southern Province | 16 | 6% | 12 | 9.8% |

| Northern Province | 11 | 4% | 3 | 2.5% |

| Total | 249 | 100% | 122 | 100% |

| IT usage experience* | ||||

| Low | 2 | 2% | ||

| Medium | 71 | 58% | ||

| High | 49 | 40% | ||

| Total | 122 | 100% | ||

4.2. Use of digital healthcare platforms

The respondents were asked about their current usage of digital healthcare platforms during the Covid-19 pandemic.While about 122 (49%) of the respondents used digital healthcare platforms in Saudi Arabia during the Covid-19 pandemic, approximately half did not use any digital healthcare platform. Seventy respondents had used the Mawid app, which makes it the most used digital healthcare platform during Covid-19, followed by Seha - about 64 participants mentioned that they had used the platform. While 21 respondents had used other digital platforms (from other governmental healthcare providers) during the pandemic, only 12 participants had used digital platforms provided by private healthcare providers. Few respondents reported using other platforms such as the Rest Assured (Tataman) app (12 individuals). Additional platforms included the Saudi Red Crescent Authority platform (11 respondents) and standalone digital platforms such as Cura, Tatbib, and Nala (2 respondents).

The respondents had heard about the digital healthcare platforms through different methods. Online social networks (i.e., Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat) ranked first, as 85 respondents selected them, followed by text messages from healthcare providers (51 respondents), from TV broadcasts, newspapers, or other media (24 respondents), from parents, friends, relatives, colleagues, etc. (33 respondents) and finally from other sources such as posters or leaflets inside healthcare provider buildings (16 respondents).

The main reasons for not using digital healthcare platforms during the Covid-19 pandemic are that the respondents did not need them (72%), the respondents did not know about them (17%), and the respondents did not know how to use them (4%).

Table 3. Measurements and confirmatory factor analysis of the instrument.

| Constructs | Items | Cronbach’s Alpha | Factor Loading | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EE | EE1 | 0.916 | 0.859 | 78% |

| EE2 | 0.882 | |||

| EE3 | 0.915 | |||

| PE | PE1 | 0.876 | 0.836 | 70% |

| PE2 | 0.755 | |||

| PE3 | 0.919 | |||

| SI | SI1 | 0.746 | 0.630 | 52% |

| SI2 | 0.810 | |||

| SI3 | 0.704 | |||

| FC | FC1 | 0.809 | 0.877 | 60% |

| FC2 | 0.561 | |||

| FC3 | 0.844 | |||

| IQ | IQ1 | 0.834 | 0.902 | 72% |

| IQ2 | 0.793 | |||

| TR | TR1 | 0.827 | 0.811 | 62% |

| TR2 | 0.738 | |||

| TR3 | 0.807 | |||

| BI | BI1 | 0.942 | 0.931 | 85% |

| BI2 | 0.960 | |||

| BI3 | 0.864 |

4.3. Survey reliability and validity

The internal reliability, discriminant validity, and convergent validity of the questionnaire were evaluated during the assessment of the measurement model. The Cronbach’s alpha test was conducted on the items of each construct to test for internal consistency, where an acceptable value is greater than 0.6 (31). Table 5 shows the measurements and confirmatory factor analysis for the survey.

The thresholds of the measurements used during data analysis are as follows: factor loading above 0.5 and average variance extracted (AVE) more than 50% of the variance. Except for one item from construct SI (which was deleted), all of the values met the selected criteria, demonstrating the good construct validity of the instrument (32).

Table 4. PLS analysis results (structural model). * p < .05.

| Path | Standardized Path Coefficient | t-value | Significance | Result of Hypothesis Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EE -> Bl | 0.040 | 0.363 | 0.717 | H1: Not supported |

| Experience -> EE | -0.015 | 0.167 | 0.867 | H1-a: Not supported |

| Age-> EE | -0.103 | 1.268 | 0.205 | H1-b: Not supported |

| PE -> BI | 0.194 | 1.323 | 0.186 | H2: Not supported |

| SI -> BI | 0.096 | 1.233 | 0.218 | H3: Not supported |

| FC-> BI | 0.233 | 2.285 | 0.023* | H4: Supported |

| IQ-> BI | 0.009 | 0.072 | 0.942 | H5: Not supported |

| TR-> BI | 0.324 | 2.783 | 0.005* | H6: Supported |

4.4. The structural model and hypothesis testing

Structural equation modeling was used to analyze the research model presented in Figure 1. The partial least squares (PLS) technique with a bootstrapping procedure using 500 re-samples of the original 122 cases was implemented to perform the structural model evaluation, conducted with SmartPLS 3.0 (33). The structural model fitness was evaluated using the Normal Fit Index (NFI ≥ 0.8) and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR ≤ 0.05) (34). Table 6 presents the results of the analysis and the hypotheses tests. The research model was also tested for how well it explained the association between constructs, demonstrating acceptable performance in explaining the variability in the outcome variables with r2=0.696 for behavior intention to use.

5. DISCUSSION

This study aims to develop an understating of healthcare consumers’ behavioral intentions for using digital healthcare platforms during the Covid-19 pandemic. The results of this study indicate that healthcare consumers generally exhibited strong intention to use the digital healthcare platforms during and after Covid-19 (mean = 4.27 out of 5). This finding is supported by other research that indicated that patients intend to accept the use of digital healthcare systems (24, 35).

The findings also showed that effort expectancy did not have a strong influence on the intention to use digital healthcare platforms in Saudi Arabia during this pandemic. This finding is different from those of other studies in the literature (8, 14, 36). However, it is supported by selected studies that indicated that effort expectancy had no direct significant effect on intention to use an electronic medical record (EMR) system (36). A possible explanation for this finding refers to the possibility that the platforms offered a friendly user design (13). The results did not indicate that age and experience moderate the impacts of effort expectancy on behavioral intention. These findings are consistent with other studies in the literature (37). An additional explanation for the overall finding is based on the backgrounds of the study respondents, as most had experience in using computers and smartphones and the majority were young adults (40 years old or less). Another justification may relate to the widespread use of social media among Saudi people, which helps them to be familiar with such platforms (37, 38).

Performance expectancy in this study did not show a significant impact on the intention to use digital healthcare platforms in Saudi Arabia. Although this finding is similar to the finding of Koivumäki et al. (8), this is not the case with other studies, which reported the performance expectancy factor as among the most important determinants of intention to use healthcare digital platforms (17, 35, 39).

Although some studies showed that social influence had an impact on patient intention to use e-health services (17), the findings of this study did not indicate that, as supported by other studies (8, 35). A possible reason for this finding may be the existing awareness of healthcare consumers in Saudi Arabia who are using the digital healthcare platforms to manage their healthcare activities during the paramedic (40).

Facilitating conditions were found in this study to influence the behavioral intention for using digital healthcare platforms in Saudi Arabia during the Covid-19 pandemic. This finding is in line with those of other studies in the literature such as (35), (19), and (13). This result was expected because consumers with better facilitation conditions - such as fast and reliable Internet access - will have a higher behavioral intention to use the digital platforms (15). The compatibility with mobile phone technologies is also considered as a reason for this finding because it allows healthcare consumers to use the digital healthcare platforms at any time and from anywhere (8).

The study findings indicate that information quality has no effect on behavioral intention for using digital healthcare platforms in Saudi Arabia during the Covid-19 pandemic. This finding is consistent with other studies that showed no evidence of the impact of information quality on behavioral intention for using e-health services (21). A possible explanation for this finding relates to the ability to use the digital healthcare platforms, as a user’s knowledge about using the platforms can affect information and prescriptions produced by the system (41). However, this finding may require extra investigation to provide insight regarding the impact of information quality on behavioral intention for using e-health services and the actual usage of such services.

Trust was found to have an influence on behavioral intention for using digital healthcare platforms in Saudi Arabia during the Covid-19 pandemic. This finding is in agreement with the findings of other studies (25, 42), which indicate the importance of considering trust issues when developing digital healthcare platforms, especially in a situation where they are the preferable way of providing healthcare services.

6. CONCLUSION

The utilization of health informatics tools during pandemics could be useful for healthcare consumers and healthcare organizations and can reduce the pressure on healthcare systems. During the Covid-19 pandemic, many health IT solutions were created to assist the healthcare systems. This paper described solutions developed specifically in Saudi Arabia and around the world in general. The paper also developed an understanding of healthcare consumers’ behavioral intention for using digital healthcare platforms during the Covid-19 pandemic. The results indicate that both facilitating conditions and trust have a significant impact on the intention to use digital healthcare platforms in Saudi Arabia. The findings of this study provide important information for healthcare leaders, indicating that they should pay special attention to using integrated healthcare tools and also to providing the required resources for healthcare consumers to use digital healthcare services. The study additionally showed that trust and privacy issues should always be considered when developing digital healthcare solutions. Future work arising from the study may include a comparison between using digital healthcare solutions during pandemics and during normal times.

Acknowledgment:

The author would like to thank the experts who evaluated and reviewed the questionnaire.

Appendix.

| Constructor | Items | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Level of experience | Low (I do not use a computer or other electronic devices) Medium ( I use basic applications i.e., MS-Office, e-mail or web browsing, online social networks). High ( I deal with hardware maintenance and use specialist software such as databases and networking programs). |

(43) |

| Effort expectancy (EE) | EE1: digital healthcare platforms are easy to use | (44), (8) |

| EE2: Interaction with digital healthcare platforms is clear | (44), (45) | |

| EE3: Learning how to use digital healthcare platforms is easy for me. | (8) | |

| Performance Expectancy (PE) | PE1: The digital healthcare platforms help me to monitor my health. | (16) |

| PE2: Using digital healthcare platforms support critical aspects of my health. | (16) | |

| PE3: Using digital healthcare platforms will enhance my effectiveness in managing my health. | (8) | |

| Social Influence | SI2: I have learned about the importance of these platforms from media such as TV. | (45) |

| SI3: People who are important to me think that I should use digital healthcare platforms. | (45) | |

| SI4: People who influence my behavior think that I should use digital healthcare platforms. | (15) | |

| Facilitating Conditions | FC1. I have the resources necessary to use digital healthcare platforms. | (15) |

| FC2. I have the knowledge necessary to use digital healthcare platforms. | (8) | |

| FC3: I would be able to use the digital healthcare platforms at any time, from anywhere. | (20) | |

| Information Quality | IQ1: The information generated by the digital healthcare platforms is correct | (20) |

| IQ3: The digital healthcare platforms generate information in a timely manner. | (46) | |

| Trust | TR1: During COVID 19 pandemic, I believe that digital healthcare platforms are trustworthy. | (20) |

| TR2: During COVID 19 pandemic, I trust the way digital healthcare platforms deal with my personal information. | (20) | |

| TR3: I trust the information output of the digital healthcare platforms. | (45) | |

| Behavioral intention | BI1. I intend to use digital healthcare platforms. | (45) |

| BI2. I plan to continue to use digital healthcare platforms frequently. | (45) | |

| BI3. I intend to use digital healthcare platforms in the next months. | (45) |

Authors contribution:

Authors was involved in all steps of preparation of this article including final proofreading.

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Financial support and sponsorship:

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Worldometers. COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic [Internet] 2020. [2020 May 28]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

- 2.Schwartz J, King CC, Yen MY. Protecting health care workers during the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak-lessons from Taiwan’s SARS response. Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2020;10 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Venkatesh V, Morris MG, Davis GB, Davis FD. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Quarterly. 2003;27(3):425–478. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rahimi B, Nadri H, Afshar HL, Timpka T. A systematic review of the technology acceptance model in health informatics. Applied Clinical Informatics. 2018;9(3):604–634. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1668091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ITU. Digital Health Platform Handbook: Building a Digital Information Infrastructure (Infostructure) for Health [Internet] 2017. Available from: https://ehna.acfee.org/c67802a7d4b3dc8914700842bf6776402b8d343c.pdf.

- 6.Hosseini M, Kaltenbach T, Kleipaß U, Neumann K, Rong O. Future of Health - The rise of healthcare platforms. 2020.

- 7.Kim J, Park HA. Development of a health information technology acceptance model using consumers’ health behavior intention. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2012;14(5):1–14. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koivumäki T, Pekkarinen S, Lappi M, Vaïsänen J, Juntunen J, Pikkarainen M. Consumer adoption of future mydata-based preventive ehealth services: An acceptance model and survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2017;19(12):1–15. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elsheikh AH, Saba AI, Elaziz MA, Lu S, Shanmugan S, Muthuramalingam T, et al. Deep learning-based forecasting model for COVID-19 outbreak in Saudi Arabia. Process Safety and Environmental Protection [Internet] 2021;149(November 2020):223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.psep.2020.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.General Authority for Statistics. Demography Survey [Internet] 2016. Available from: https://www.stats.gov.sa/sites/default/files/en-demographic-research-2016_2.pdf.

- 11.Alharbi F. Holistic approach framework for cloud computing strategic decision - making in healthcare sector (haf - ccs) [Internet] 2017. Available from: http://eprints.staffs.ac.uk/3973/

- 12.MoH. National E- Health Strategy [Internet] 2020. [2020 May 31]. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/nehs/Pages/Ehealth.aspx.

- 13.Cranen K, Veld RHI T, Ijzerman M, Vollenbroek-Hutten M. Change of patients’ perceptions of telemedicine after brief use. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2011;17(7):530–535. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2010.0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tavares J, Oliveira T. Electronic Health Record Patient Portal Adoption by Health Care Consumers: An Acceptance Model and Survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research [Internet] 2016 Mar 2;18(3):e49. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5069. Available from: http://www.jmir.org/2016/3/e49/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venkatesh V, Thong JYL, Xu X. Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. MIS Quarterly. 2012;36(1):157–178. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson EV, Lankton NK. Modeling patients’ acceptance of provider-delivered E-health. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2004;11(4):241–248. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albar AM, Hoque MR. Patient Acceptance of e-Health Services in Saudi Arabia: An Integrative Perspective. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2019;25(9):847–852. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2018.0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aldraehim M, Edwards S. Cultural impact on e-service use in Saudi Arabia: the need for interaction with other humans. [2014 Jun 11];International Journal of of Advanced Computer Science [Internet] 2013 3(10):655–662. Available from: http://eprints.qut.edu.au/59939/ [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cimperman M, Makovec Brenčič M, Trkman P. Analyzing older users’ home telehealth services acceptance behavior - applying an Extended UTAUT model. International Journal of Medical Informatics [Internet] 2016 Jun;90:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.03.002. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1386505616300338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ojo AI. Validation of the delone and mclean information systems success model. Healthcare Informatics Research. 2017;23(1):60–66. doi: 10.4258/hir.2017.23.1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou M, Zhao L, Kong N, Campy KS, Qu S, Wang S. Factors influencing behavior intentions to telehealth by Chinese elderly: An extended TAM model. International Journal of Medical Informatics [Internet] 2019;126(2):118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu CH, Hsiao JL, Chen RF. Factors determining nurse acceptance of hospital information systems. CIN - Computers Informatics Nursing. 2012;30(5):257–264. doi: 10.1097/NCN.0b013e318224b4cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoque MR, Bao Y, Sorwar G. Investigating factors influencing the adoption of e-Health in developing countries: A patient’s perspective. Informatics for Health and Social Care [Internet] 2017 Jan 2;42(1):1–17. doi: 10.3109/17538157.2015.1075541. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3109/17538157.2015.1075541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu CF, Tsai YC, Jang FL. Patients’ acceptance towards a web-based personal health record system: An empirical study in Taiwan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2013;10(10):5191–208. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10105191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Misra SC, Bisui S, Singh A. A study on the role of trust factor in adopting personalised medicine. Behaviour and Information Technology [Internet] 2019;0(0):1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saechang O, Yu J, Li Y. Public Trust and Policy Compliance during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Professional Trust. Healthcare [Internet] 2021 Feb 2;9(2):151. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9020151. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/9/2/151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore G, Benbasat I. Development of an instrument to measure the perceptions of adopting an information technology innovation. [2015 Feb 16];Information systems research [Internet] 1991 2(3):192–222. Available from: http://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/abs/10.1287/isre.2.3.192. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Isaías P, Pífano S, Miranda P. Isaías P, editor. Subject Recommended Samples. Information Systems Research and Exploring Social Artifacts: Approaches and Methodologies. IGI Global. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sylvia L, Jason A, Aldraehim M, Edwards SLS, Watson J, Chan T. Cultural impact on e-service use in Saudi Arabia: the need for interaction with other humans. International Journal of … [Internet] 2013;3(3):655–662. Available from: http://eprints.qut.edu.au/59939/ [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mellinger CD, Hanson TA. Routledge; 2016. Quantitative Research Methods in Translation and Interpreting Studies. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gliem JA, Gliem RR. Calculating, Interpreting, and Reporting Cronbach’s Alpha Reliability Coefficient for Likert-Type Scales. 2003 Midwest Research to Practice Conference in Adult, Continuing, and Community Education; 2003. pp. 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams B, Brown T, Onsman A. Exploratory factor analysis : A five-step guide for novices. Journal of Emergency Primary Health Care (JEPHC) 2012;8(3):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ringle CM, Wende S, Will A. SmartPLS 3.0 [Internet] 2015. Available from: http://www.smartpls.com.

- 34.Hooper D, Coughlan J, Mullen MR. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods. 2008;6(1):53–60. [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Veer AJE, Peeters JM, Brabers AEM, Schellevis FG, Rademakers JJDJM, Francke AL. Determinants of the intention to use e-health by community dwelling older people. BMC Health Services Research. 2015;15(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0765-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shiferaw KB, Mehari EA. Modeling predictors of acceptance and use of electronic medical record system in a resource limited setting: Using modified UTAUT model. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked [Internet] 2019 Apr 17;:100182. doi: 10.1016/j.imu.2019.100182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kasim HA. Factors Affecting Knowledge Sharing Using Virtual Platforms - A Validation of Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) International Journal of Managing Public Sector Information and Communication Technologies. 2015;6(2):01–19. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davis FD, Bagozzi RP, Warshaw PR. Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation to Use Computers in the Workplace1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology [Internet] 1992 Jul;22(14):1111–1132. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1992.tb00945.x. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chao CM. Factors determining the behavioral intention to use mobile learning: An application and extension of the UTAUT model. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019;10(July):1–14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Free C, Phillips G, Galli L, Watson L, Felix L, Edwards P, et al. The effectiveness of mobile-health technology-based health behaviour change or disease management interventions for health care consumers: a systematic review. [2014 Jul 10];PLoS medicine [Internet] 2013 Jan;10(1):e1001362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yusof MM, Kuljis J, Papazafeiropoulou A, Stergioulas LK. An evaluation framework for Health Information Systems: human, organization and technology-fit factors (HOT-fit) [2014 May 7];International Journal of medical informatics [Internet] 2008 Jun;77(6):386–398. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoque MR, Bao Y, Sorwar G. Investigating factors influencing the adoption of e-Health in developing countries: A patient’s perspective. Informatics for Health and Social Care [Internet] 2017 Jan 2;42(1):1–17. doi: 10.3109/17538157.2015.1075541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Almuayqil S, Atkins AS, Sharp B. Ranking of E-Health Barriers Faced by Saudi Arabian Citizens , Healthcare Professionals and IT Specialists in Saudi Arabia. Health. 2016;8:1004–1013. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Venkatesh V, Thong JYL, Xu X. Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology: A synthesis and the road ahead. Journal of the Association for Information Systems. 2016;17(5):328–376. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tavares J, Oliveira T. Electronic Health Record Portal Adoption: A cross country analysis. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2017;17(1):1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12911-017-0482-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khan I, Xitong G, Ahmad Z, Shahzad F. Investigating Factors Impelling the Adoption of e-Health: A Perspective of African Expats in China. SAGE Open. 2019;9(3) [Google Scholar]