Abstract

With the rapid development of computer technology, data collection becomes easier, and data object presents more complex. Data analysis method based on machine learning is an important, active, and multi-disciplinarily research field. Support vector machine (SVM) is one of the most powerful and fast classification models. The main challenges SVM faces are the selection of feature subset and the setting of kernel parameters. To improve the performance of SVM, a metaheuristic algorithm is used to optimize them simultaneously. This paper first proposes a novel classification model called IBMO-SVM, which hybridizes an improved barnacle mating optimizer (IBMO) with SVM. Three strategies, including Gaussian mutation, logistic model, and refraction-learning, are used to improve the performance of BMO from different perspectives. Through 23 classical benchmark functions, the impact of control parameters and the effectiveness of introduced strategies are analyzed. The convergence accuracy and stability are the main gains, and exploration and exploitation phases are more properly balanced. We apply IBMO-SVM to 20 real-world datasets, including 4 extremely high-dimensional datasets. Experimental results are compared with 6 state-of-the-art methods in the literature. The final statistical results show that the proposed IBMO-SVM achieves a better performance than the standard BMO-SVM and other compared methods, especially on high-dimensional datasets. In addition, the proposed model also shows significant superiority compared with 4 other classifiers.

Keywords: Barnacles mating optimizer, Feature selection, Support vector machine, Gaussian mutation, Logistic model, Refraction-learning

Introduction

Due to rapid technology advancement, an enormous amount of data is stored in databases. It becomes hard to make decisions for industrial intelligence by analyzing the stored data. Data mining is a process of acquiring information and knowledge from such huge data [1]. Feature selection (FS) is an important preprocessing step in the field of data mining and machine learning [2]. Its purpose is to eliminate the redundant and irrelevant features to compress the original data into a low-dimensional space, reduce the computational complexity, and increase the classification accuracy [3–5]. In essence, the process of FS is to select the optimal feature subset from the original dataset. In other words, it can be regarded as a combinatorial optimization task [6].

FS methods explicitly or implicitly combine some subset search mechanism and subset evaluation mechanism, which can be divided into three categories: filter, wrapper, and embedding [7]. The filter method performs FS on the dataset based on correlation statistics and then trains the learning model. There is no interaction between the process of FS and the process of training the learning model [8]. The wrapper method evaluates the selected feature subset based on the performance of the learning model. In other words, the purpose of the wrapper method is to select the optimal feature subset for a given learning model [9]. Therefore, the wrapper method usually achieves better results than the filter method. However, since the learning model needs to be trained many times in the FS process, the computational overhead of the wrapper method is usually much higher than that of the filter method [10]. For the embedding method, its idea is to embed the FS process into the construction of the learning model. Because of the complexity of the concepts, it is not easy to construct such models. In addition, it is also hard to improve the learning model to get better results [11]. After comparison and consideration, the wrapper-based FS is used in this paper.

In general, learning tasks are divided into two categories: unsupervised learning and supervised learning. The unsupervised learning does not know the label of each training sample (i.e., the class of each training sample) in advance. For supervised learning, the training samples include inputs and outputs (i.e., features and class labels), which results in a better result than unsupervised learning in most cases [12]. The supervised algorithm commonly used includes decision tree (DT) [13], naïve Bayes (NB) [14], k-nearest neighbor (kNN) [15–17], neural networks (NNs) [18, 19], and support vector machine (SVM) [20–22]. Among them, SVM was first formally proposed by Cortes and Vapnik in 1995. Based on the statistical learning theory, SVM minimizes the structural risk to design the learning model. In addition, SVM has been used to solve the various artificial intelligence enabled applications due to excellent learning ability and generalization ability [23], such as face recognition [24], text classification [25], handwriting character recognition [26], and bioinformatics [27]. Although SVM has many advantages, it also has some limitations. For instance, it is sensitive to the initial values of parameters. These parameters include the penalty factor and the kernel parameters. The setting of these parameters can affect the generalization performance of SVM. The details of the SVM classifier will be shown in Sect. 3 of this paper. It is worth noting that the performance of SVM, like many other wrapper methods, also depends on the selected feature subset. The better feature subset can be obtained by an excellent search mechanism, which is crucial to improve the computational efficiency and classification accuracy [28, 29].

The curse of dimensionality (CoD) is the main obstacle to big data classification [30]. If a dataset contains N features, the number of available solutions increases exponentially with the number of features, resulting in 2N solutions being generated and evaluated. This requires high computational cost, making researchers spend too much time to get a result [31]. Traditional dimension reduction methods cannot solve this problem well because of some limitations in hardware. Based on published high-quality papers, a new trend to solve this problem is developed. Researchers introduce metaheuristic algorithms (MAs) to solve the FS problem in classification tasks. MAs do not provide an exact solution but only an estimated result in a feasible time. According to the number of solutions, MAs can be divided into single-point search and population-based methods [32]. The single-point search method describes the search trajectory of a solution in the search space, such as Tabu search and simulated annealing [33]. Meanwhile, the population-based method describes the evolution process of a set of points in the search space, such as swarm intelligence (SI) algorithm and evolutionary algorithm (EA) [34].

So far, many MAs have been proposed. Barnacle mating optimizer (BMO) is a newly proposed bio-inspired EA, originally designed by Sulaiman in 2020 [35]. BMO has the features of fewer parameters and can search promising regions of the search space. However, in the field of machine learning, the no free lunch (NFL) theorem logically proves: there is no algorithm for solving all optimization problems [36]. In other words, it is pointless to discuss which algorithm is better without the specific problem. This is the motivation of this research, as well as the NFL theorem, whereby we use Gaussian mutation, logistic model, and refraction-learning to improve the performance of BMO for the first time. Generally, an improved algorithm can help evaluate the potential features from the pool of features of a given machine learning problem. It can improve the performance and computation speed of the given machine learning models. Or, it is used to resolve the parameters tuning problem with most machine learning models. To realize a simultaneous optimization process, the proposed IBMO finally helps the SVM classifier find the optimal feature subset and parameters at the same time. In terms of experiments, a set of 23 classical benchmark functions are used to verify the impact of control parameters and introduced strategies. In addition, IBMO-SVM is also applied to 20 real-world datasets, including 4 high-dimensional datasets, and compared with other 6 state-of-the-art methods. They are particle swarm optimization (PSO) [37], grasshopper optimization algorithm (GOA) [38], slap swarm algorithm (SSA) [39], Harris hawks optimization (HHO) [40], teaching–learning-based optimization (TLBO) [41], and hypergraph-based genetic algorithm (HG-GA) [42]. The effectiveness and superiority of IBMO-SVM are evaluated by classification accuracy, selection size, fitness value, running time, Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and Friedman’s test. Finally, the experimental results are more comprehensive and convincing through comparison with other 4 classifiers. They are logistic regression (LR), decision tree (DT), feedforward neural network (FNN), and k-nearest neighbor (kNN).

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 presents the previous related works. Section 3 introduces some preliminary knowledge, including a brief overview of BMO and SVM. Section 4 highlights the details of the proposed method. Experiments are implemented, and results are analyzed in Sect. 5. Finally, in Sect. 6, conclusions and future works are given.

Related works

The learning algorithms combining with the machine learning techniques are currently used for classification tasks. Wan et al. proposed a novel manifold learning algorithm based on local structure, namely two-dimensional maximum embedding difference (2DMED). This method directly extracted the optimal projective vectors from 2D image matrices. In addition, it successfully avoided computing inverse matrices by virtue of difference trace. Experimental results showed that 2DMED got better recognition rates on face database and handwriting digital database [43]. Fuzzy 2D discriminant locality preserving projections (F2DDLPP) is a novel combination of 2D discriminant locality preserving projections (2DDLPP) and fuzzy set theory. This method enhanced the discriminant power in mapping into a low-dimensional space. Through comparison and analysis, F2DDLPP can select the most useful features for classification [44]. In 2017, the maximum margin criterion and fuzzy set theory were used to extend the development of locally graph embedding algorithms. It was an effective face recognition technique [45]. For other supervised learning problems, there are also many learning algorithms.

SVM has some parameters to control different aspects of algorithm performance. Generally, there are three basic methods for tuning these parameters. Some researchers try different values to tune these parameters by orthogonal experiments. The manual selection method needs to know the influence of parameters on model capacity in advance. When there are three or fewer parameters, another common method is grid search. This method is very slow due to a large number of parameter combinations. The third method is to use MAs. The parameter search problem can be transformed into an optimization problem. In this case, decision variables are parameters, and the cost of optimization is the fitness value of the fitness function. To build an efficient classification model, FS can help improve the accuracy of the model. Some distinguished lines of researches perform FS and simultaneously consider parameters of SVM. Such examples are presented as follows.

In [37], Huang et al. combined discrete PSO with continuous PSO to simultaneously perform the feature subset selection and SVM parameter setting. Additionally, PSO-SVM was implemented with a distributed parallel architecture to reduce the computational time. A hybrid method based on the GOA was presented by Aljarah et al. [38] to achieve the same goal in 2018. The experimental results revealed that GOA was superior to grid search, PSO, genetic algorithm (GA), multi-verse optimizer (MVO), gray wolf optimizer (GWO), firefly algorithm (FF), bat algorithm (BA), and cuckoo search (CS) on improving the SVM classifier accuracy. In 2020, Al-Zoubi et al. applied the SSA-SVM method to 3 widespread medical cases. Compared with other methods, this model had better performance in accuracy, recall, and precision, and was an effective method to solve popular diagnosis problems [39]. Recently, Houssein et al. have hybridized HHO with SVM and kNN for chemical descriptor selection and compound activities. Compared with competitor methods, HHO-SVM had higher performance. In addition, when the number of iterations increases, HHO-SVM obtained better results than HHO-kNN [40]. Examples of such native MAs which are applied for this optimization field are also GA [46], ant colony algorithm optimization (ACO) [47], teaching–learning-based optimization (TLBO) [41], brain storm optimization (BSO) [48], etc. A hypergraph framework was added to GA (called HG-GA) by Gauthama Raman et al. [42]. By using the hyperclique property of hypergraph to generate the initial population, the search for the optimal solution was accelerated, and trapping at the local optimum was prevented. To deal with an intrusion detection system (IDS), the HG-GA-SVM model was used and compared with GA-SVM, PSO-SVM, BGSA-SVM, random forest, and Bayes net. In terms of classifier accuracy (approximately increase 2%), detection rate, false alarm rate, and runtime, HG-GA-SVM achieved overwhelming performance. Baliarsingh et al. [49] proposed a method known as memetic algorithm-based SVM (M-SVM), which was inspired by embedding social engineering optimizer (SEO) in emperor penguin optimizer (EPO). SEO was considered a local search strategy, and EPO was used as a global optimization framework. The experiment was analyzed from two aspects, including binary-class datasets and multi-class datasets. It is observed from statistical results that the proposed method over other competent methods for gene selection and classification of microarray data. Based on the literature review, it can be found that researchers have never stopped exploring. According to the NFL theorem, it motivated us to propose a novel method to better tackle this problem.

Preliminary knowledge

Barnacle mating optimizer

Barnacles are microorganisms that attach themselves to objects in the water. The long penis is their main feature. Their mating group includes all neighbors and competitors within reach of their penis. Barnacle mating optimizer is inspired by the mating process of barnacles. By simulating three processes (i.e., initialization, selection process, and reproduction), the practical optimization problem is solved. Details are described as follows [35]:

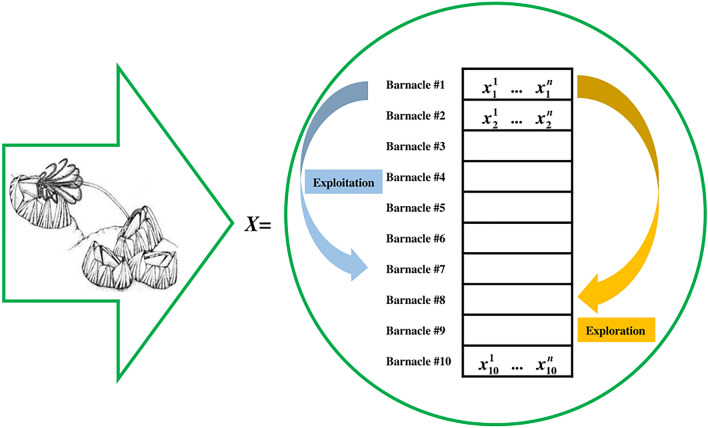

Firstly, it is assumed that the candidate solution is barnacles, where the matrix of the population can be expressed using Eq. (1). The evaluation of the population and sorting process are done to locate the best solution so far at the top of . Then, the parents to be mated are selected by Eqs. (2) and (3).

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

where is the number of barnacle population, is the number of control variables, and and represent the parents to be mated.

Since there are no specific equations to derive the reproduction process of barnacles, BMO emphasizes the genotype frequencies of parents to produce the offspring based on the Hardy–Weinberg principle [50, 51]. It is worth highlighting that the length of their penises () plays an important role in determining the exploitation and exploration processes. Assuming , it can be seen from Fig. 1 that barnacle #1 can only mate with one of the barnacles #2-#7. If the selection of barnacles to be mated is within the range of of barnacle, the exploitation process is occurred. Equation (4) is proposed to produce new variables of offspring from barnacle parents.

| 4 |

where is the normally distributed random number between [0, 1], , and represent the variables of and barnacles that have been selected in Eqs. (2) and (3). and represent the genotype frequencies of and barnacles in the new offspring.

Fig. 1.

Selection of mating process of BMO [35] (image of barnacles adopted from [52])

If barnacle #1 selects barnacle #8, it is over the limit. Thus, the normal mating process does not occur. At this time, the offspring is produced by the sperm cast process. In BMO, the sperm cast is regarded as the exploration process, which is expressed as follows.

| 5 |

where is the random number between [0, 1].

It can be seen from Eq. (5) that the new offspring is produced by barnacle since it obtains the sperms that are released into the water by other barnacles elsewhere. During the iteration, the position of the barnacle is updated according to Eq. (4) or Eq. (5). Finally, the BMO can be defined to approximate the global optimum for optimization problems.

Support vector machine

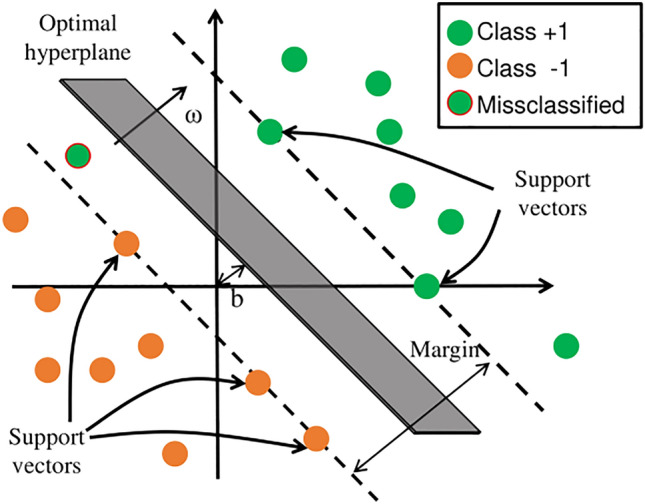

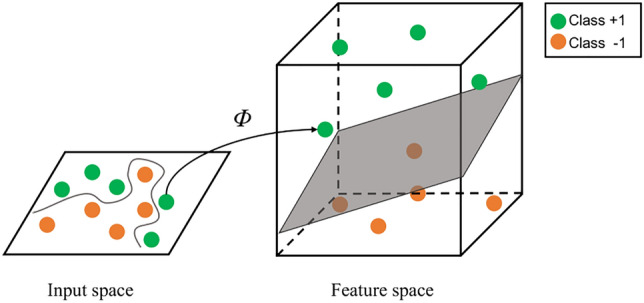

For linear separable problems, the core idea of SVM is to find an optimal hyperplane that maximizes the margin between two classes. In this case, the generalization ability of the model is the strongest, and the classification result is the most robust. Some concepts in SVM are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Linear classification based on SVM

If the given data set is , the hyperplane is:

| 6 |

Further, the maximizing margin is equivalent to minimizing . Introducing the slack variable , represents that there are a small number of outliers. The penalty factor is one of the critical parameters that represent the tolerance to outliers. The standard SVM model is as follows:

| 7 |

where is the inertia weight, and is a constant.

For the nonlinear case, SVM maps the data in the input space to the high-dimensional feature space. This idea is vividly shown in Fig. 3. The inner product of feature vectors needs to be calculated in nonlinear transformation. To avoid this obstacle, the kernel function is introduced to express the result of the inner product. In this case, the SVM model can be transformed into the following dual problem:

| 8 |

where represents the Lagrange multiplier.

Fig. 3.

Nonlinear classification based on SVM

In this paper, a widely applicable radial basis function (RBF) kernel is adopted, whose expression is:

| 9 |

where represents the width of the RBF kernel.

The penalty factor and kernel parameter directly affect the generalization ability and complexity of SVM.

Application of proposed IBMO for FS and SVM optimization

In this section, the proposed model followed to use IBMO for FS and SVM optimization is described in detail. Firstly, two equation issues are addressed, including the representation of the solution and the definition of the fitness function. Secondly, the improvement ideas of IBMO are elaborated. In addition, the pseudocode and flowchart of IBMO are also presented. Finally, the flowchart of the proposed application model is given.

Two equation issues

Representation of the solution

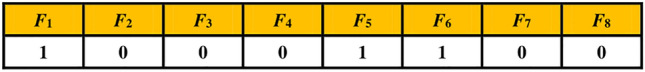

In FS tasks, the solution is represented in binary form. Each variable is limited between [0, 1]. If the value is within (0.5, 1], it is mapped to bit "1." Bit "1" means the corresponding feature is reserved. If the value is within [0, 0.5], it is mapped to bit "0." Bit "0" means the corresponding feature is rejected. As shown in Fig. 4, the solution contains 8 variables (i.e., 8 features). The 1st, 5th, and 6th features are selected.

Fig. 4.

A sample solution with 8 variables

In this paper, the first two variables of the solution are defined as the penalty factor and kernel parameter . Other variables correspond to the selected features. In other words, each solution has variables in Eq. (1). After redefinition, each new solution, as shown in Eq. (10), has variables.

| 10 |

Definition of the fitness function

In this paper, a fitness function is required to evaluate the solution. FS is a multi-objective optimization problem, which needs to achieve fewer selected features and higher classification accuracy. To balance the relationship between the two, the fitness function in Eq. (11) is defined as follows:

| 11 |

where is the error rate of the SVM classifier, is the number of selected features, is the total number of original features, and are two parameters corresponding to the impact of classification performance and feature size, and .

Description of IBMO

Strategy 1: Gaussian mutation

A well-designed optimizer should make full use of and generalize random operators in the early phase. In this way, the diversity of the population can be enhanced, and solutions can deeply explore each region of the feature space. At the same time, the tail of the Gaussian distribution is narrow, so the mutation has a higher probability to generate a new solution in the vicinity of the original position. Hence, the search process utilizes smaller steps to search each position in the solution space. The Gaussian density function is defined as follows [53]:

| 12 |

where represents expected value, represents the variance. Assuming , this equation is reduced to the generated random variable. The mutant position of barnacles can be expressed by Eq. (13).

| 13 |

where corresponds to the Gaussian step vector created by Eq. (12), is the Gaussian random value between [0,1].

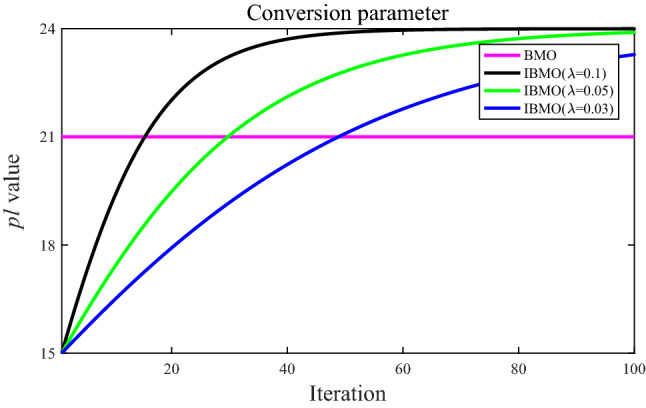

Strategy 2: conversion parameter based on logistic model

The well-organized optimizer should achieve a high level of exploration at the beginning of the search and more exploitation in the last phase. In BMO, the value of plays an important role in determining the exploitation and exploration processes. The original paper concluded through experiments that when the value of is small, too many exploration processes occurred. Instead, too much exploitation occurred. It is suggested that the selection of can be set between 50% and 70% of the total population size. In the original paper, the value of is set to a constant.

We bring out a mathematical model to change the value of so that it can be adjusted dynamically with the lapse of iteration. Thus, the logistic model is finally adopted, and its mathematical expression is [54]:

| 14 |

where and represent and the maximum and minimum values of , respectively, represents the number of iteration, and represents the initial decay rate. Using the method of variable separation to solve Eq. (14), Eq. (15) is obtained.

| 15 |

It can be seen from Eq. (15) that the conversion parameter when t = 0; while , . The influence of the conversion parameter on the optimization process is analyzed as follows. As mentioned above, a high level of exploration is required in the early phase, and a small value of can help the exploration process occur. Therefore, when t = 0, . As the search progresses, the exploitation phase is normally performed after the exploration phase. When the number of iterations increases, the value of also increases according to Eq. (15). A larger value of is beneficial to the exploitation process. By dynamic conversion parameter, a reasonable and fine balance between the exploration and exploitation is achieved.

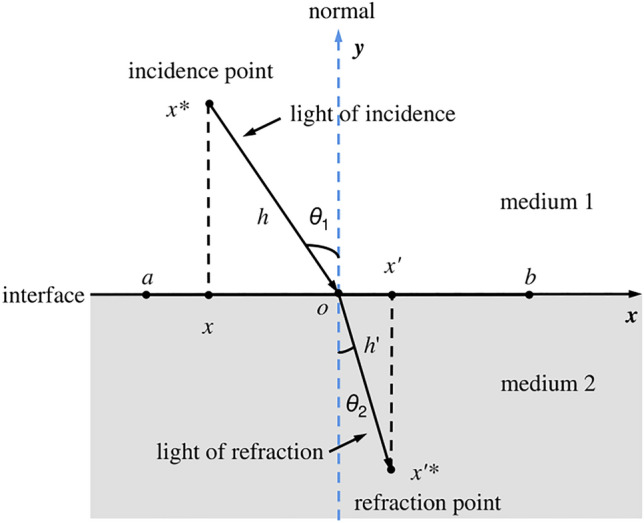

Strategy 3: refraction-learning

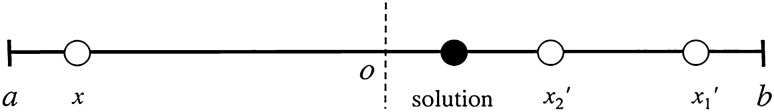

In Fig. 5, some concepts about refraction are noted [55]. . is the center point of . The refraction index is calculated by Eq. (16).

| 16 |

Fig. 5.

Refraction-learning process in one-dimensional space [55]

Let the rate , Eq. (16) can be transformed into the following form:

| 17 |

where represents the upper bound and represents the lower bound.

is called the opposite solution of based on refraction-learning. Generally, Eq. (17) can be extended to n-dimensional space.

| 18 |

where represents the jth dimension of upper bound, represents the jth dimension of the lower bound. and are the jth dimension of and , respectively.

More exploitation are often required in the last phase. But there is the possibility of trapping in the local optimum. In the last phase of BMO, the refraction-learning strategy is introduced to overcome this drawback. The global optimal solution is carried out refraction-learning strategy to generate the opposite solution by Eq. (18). Then, they will be evaluated and updated.

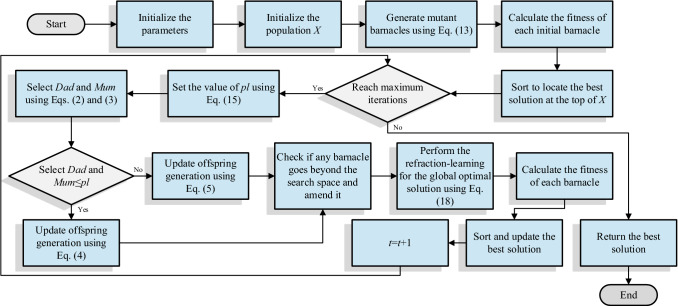

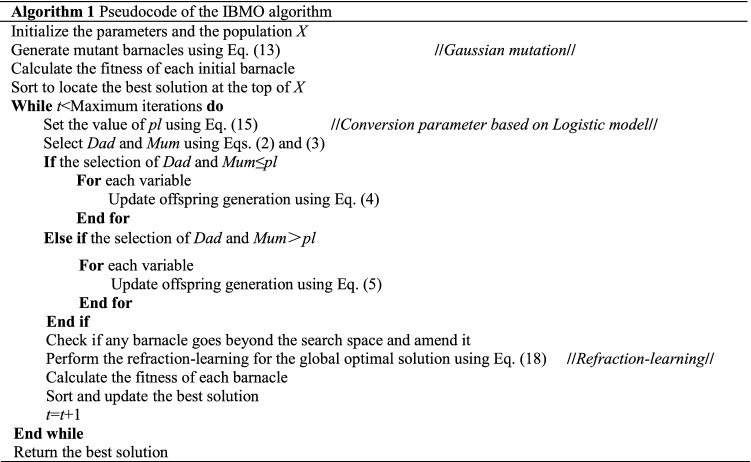

Additional details on IBMO

The native BMO has some drawbacks such as low search accuracy and easy to trapped in the local optimum. In this paper, three strategies are introduced to improve the performance of the algorithm. Firstly, Gaussian mutation is applied to initial barnacles to enhance the diversity of the population. Secondly, the logistic model is adopted to realize the dynamic conversion of the important parameter , so as to achieve a fine balance between exploration and exploitation. Finally, the global optimal solution is carried out the refraction-learning strategy to generate the opposite solution. By evaluating and updating them, the algorithm has a higher probability of escaping the local optimum. These strategies are considered from different levels of the algorithm. A more detailed analysis has also been mentioned above. The pseudocode of IBMO is described in Algorithm 1. The intuitive and detailed process of IBMO is shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Flowchart of the IBMO algorithm

Computational complexity analysis of IBMO

The computational complexity of IBMO is mainly related to dimension (D), population size (N), maximum iteration times (T), and cost of fitness function (F). To sum up, the computational complexity analysis focuses on four components: initialization, fitness evaluation, sorting, and barnacle updating. Note that the computational complexity of initialization is , fitness evaluation is , sorting is , and barnacle updating is . Hence, the overall computational complexity of IBMO can be expressed as follows:

| 19 |

| 20 |

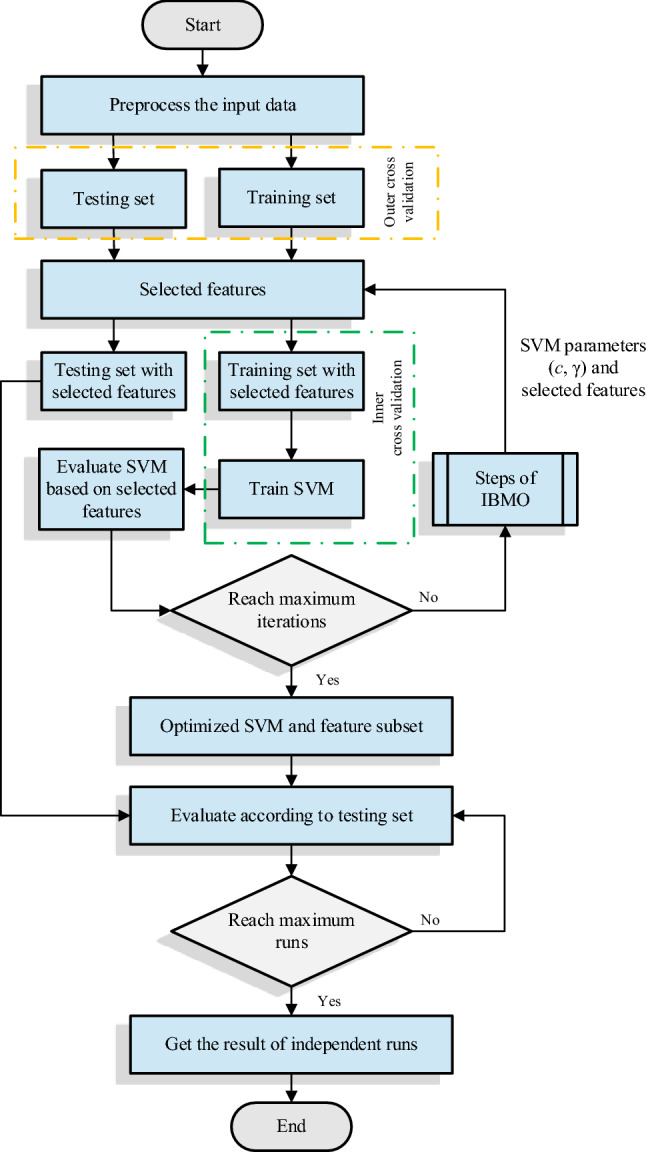

IBMO for FS and SVM optimization

The proposed method commences by dividing the preprocessed dataset into training and testing sets. After that, the most optimal model is achieved by using tenfold cross-validation. IBMO starts executing the random vector generated by Eq. (10). Then, SVM begins its training process by running the training set with selected features. During this phase, the inner cross-validation is carried out to produce a more robust model and avoid over fitting. IBMO will receive the fitness function value at the end of the training process. All the previous steps are repeated until the termination criterion (i.e., the maximum number of iterations) is met. Finally, the proposed method reports the optimal individual. The final selected individuals are applied to the testing phase. Figure 7 shows the framework of the proposed method.

Fig. 7.

Flowchart of the IBMO application model

Experimental design and results

Preparatory works

To validate the efficiency of the proposed method, 20 standard datasets from UCI are utilized [56]. Table 1 reports the details of the selected datasets, such as the number of features, instances, and classes. As can be seen, some datasets are considered high-dimensional datasets because they have thousands of features. It will make our work more challenging and generate more comprehensive results. Before using the datasets, it is essential to preprocess them. This process is divided into two steps. Firstly, all the features are converted into numeric form. For example, in the Hepatitis dataset, males and females can be converted into 0 and 1, respectively. Then, the min–max normalization is used to scale the features to [0, 1]. In this way, the effect of numeric magnitude on feature weights can be alleviated. Equation (21) is provided.

| 21 |

where represents the normalized feature, and and are the minimum and maximum values of the targeted feature , respectively.

Table 1.

Description of datasets

| # | Dataset | No. of features | No. of instances | No. of classes | Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Iris | 4 | 150 | 3 | Low dimensionality |

| 2 | Tic-tac-toe | 9 | 958 | 2 | Low dimensionality |

| 3 | Breast Cancer | 9 | 699 | 2 | Low dimensionality |

| 4 | ILPD | 10 | 583 | 2 | Low dimensionality |

| 5 | Wine | 13 | 178 | 3 | Low dimensionality |

| 6 | Congressional VR | 16 | 435 | 2 | Low dimensionality |

| 7 | Zoo | 16 | 101 | 7 | Low dimensionality |

| 8 | Lymphography | 18 | 148 | 4 | Low dimensionality |

| 9 | Hepatitis | 19 | 155 | 2 | Low dimensionality |

| 10 | Parkinsons | 22 | 195 | 2 | Low dimensionality |

| 11 | Flags | 30 | 194 | 8 | Low dimensionality |

| 12 | Dermatology | 34 | 366 | 6 | Low dimensionality |

| 13 | Ionosphere | 34 | 351 | 2 | Low dimensionality |

| 14 | Soybean small | 35 | 47 | 4 | Low dimensionality |

| 15 | Lung cancer | 56 | 32 | 3 | Low dimensionality |

| 16 | Sonar | 60 | 208 | 2 | Low dimensionality |

| 17 | Gastrointestinal lesions | 698 | 76 | 3 | High dimensionality |

| 18 | DBWorld e-mails | 4702 | 64 | 2 | High dimensionality |

| 19 | Arcene | 10,000 | 900 | 2 | High dimensionality |

| 20 | Amazon reviews | 10,000 | 1500 | 50 | High dimensionality |

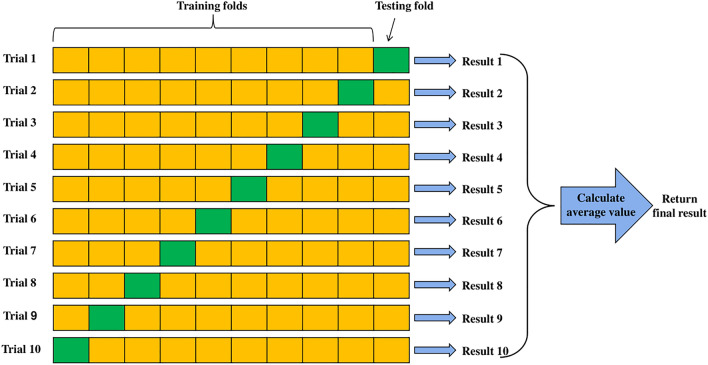

LIBSVM is used for the SVM classifier [57]. Tenfold cross-validation is used to obtain unbiased classification results. This method divides each dataset into ten equal parts. Nine folds are used for training and the rest of one fold for testing. Then, this process is repeated ten times to ensure that each part is used as the testing set. Figure 8 shows the diagram of tenfold cross-validation for a single run.

Fig. 8.

Diagram of tenfold cross-validation

The proposed method is compared with 6 state-of-the-art methods, including PSO [37], GOA [38], SSA [39], HHO [40], TLBO [41], and HG-GA [42], based on some evaluation metrics. The maximum of iterations for all algorithms is 100, and the population size is 30. We follow the same parameters in the original papers. The parameter settings of algorithms are shown in Table 2. Moreover, the parameter in the fitness function is set to 0.99, the parameter is set to 0.01 according to domain-specific knowledge [58, 59]. In the same experimental conditions, the fairness of comparison is guaranteed. Table 3 shows these details. To prevent the random nature of the test results, each experiment is run 10 times independently.

Table 2.

Parameter settings of algorithms

| Reference | Algorithm | Parameters | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| [37] | PSO | Inertia weight wmax | 0.95 |

| Inertia weight wmin | 0.05 | ||

| Learning factors c1 and c2 | 2 | ||

| Velocity vmax | + 200 | ||

| Velocity vmin | −200 | ||

| [38] | GOA | Parameter cmin | 0.00001 |

| Parameter cmax | 1 | ||

| [39] | SSA | Control parameter c1 | [2,e−16] |

| Random parameters c2, c3 | (0,1) | ||

| [40] | HHO | Initial energy E0 | (−1,1) |

| Jump strength J | (0,2) | ||

| Escape probability r | 0.5 | ||

| Random parameters r1, r2, r3, r4 | [0,1] | ||

| [41] | TLBO | Teaching factor TF | 1 |

| Random number r | [0,1] | ||

| [42] | HG-GA | Crossover rate | 0.8 |

| Mutation rate | 0.02 | ||

| Weight for detection rate DW | 0.80 | ||

| Weight for false alarm rate FAW | 0.05 | ||

| Weight for feature subset size FW | 0.15 | ||

| BMO | Penis length pl | 70% population size |

Table 3.

Details of experimental conditions

| Name | Settings |

|---|---|

| Hardware | |

| CPU | Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-4210U processor |

| Frequency | 1.70 GHz |

| RAM | 4 GB |

| Hard drive | 500 GB |

| Software | |

| Operating system | Windows 10 (64 bits) |

| Language | MATLAB R2016b |

Evaluation metric

Classification accuracy this metric evaluates the accurate of the classifier in predicting the right class using selected feature subsets.

Selection size this metric evaluates the size of the optimal feature subset obtained by the search algorithm.

Fitness value this metric combines the above two factors as the fitness function in FS optimization problems.

Running time this metric reflects the execution speed of the method.

P-value this metric is used to detect significant differences between two methods based on two nonparametric statistical tests (i.e., Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Friedman’s test).

Simulation results and discussions

Impact of control parameters

As discussed in Sect. 4.2, the conversion parameter strategy based on the logistic model allows IBMO to smoothly transit between exploration and exploitation. The refraction-learning strategy is more effective to enhance exploitation during the evolution. However, some control parameters are crucial to improve the performance of the algorithm. The purpose of this subsection is to analyze the sensitivity of these control parameters and to provide the theoretical basis for the following experiments.

In Eq. (15), the parameter controls the changing trend of the value. For intuitive comparison, Fig. 9 shows the fixed value in BMO and different values in IBMO with . In BMO, the original paper suggests that the value is set to 70% of the population size. In IBMO, the and values are set to 50% and 80% of the population size, respectively. To investigate the sensitivity of the parameter , 23 classical benchmark functions from Tables 4, 5, 6 are implemented to evaluate the performance of IBMO with different . Table 7 summarizes the average fitness values of IBMO using different for 23 functions. Table 7 shows that there is no regular increase or decrease in the average as the changes. IBMO with can get better results except for function F8. This is because the conversion parameter strategy based on the logistic model with makes IBMO more effective in the transition between global and local terms.

Fig. 9.

Comparison of the control parameter

Table 4.

Unimodal benchmark functions

| F | Description | Dim | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 30 | [−100,100] | 0 | |

| F2 | 30 | [−10,10] | 0 | |

| F3 | 30 | [−100,100] | 0 | |

| F4 | 30 | [−100,100] | 0 | |

| F5 | 30 | [−30,30] | 0 | |

| F6 | 30 | [−100,100] | 0 | |

| F7 | 30 | [−1.28,1.28] | 0 |

Table 5.

Multimodal benchmark functions

| F | Description | Dim | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F8 | 30 | [−500,500] | −418.9829 × Dim | |

| F9 | 30 | [−5.12,5.12] | 0 | |

| F10 | 30 | [−32,32] | 0 | |

| F11 | 30 | [−600,600] | 0 | |

| F12 | 30 | [−50,50] | 0 | |

| F13 | 30 | [−50,50] | 0 |

Table 6.

Fixed-dimension multimodal benchmark functions

Table 7.

Average fitness values of IBMO using different λ

| F | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 |

| F2 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 |

| F3 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 |

| F4 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 |

| F5 | 2.82E + 01 | 2.60E + 01 | 2.82E + 01 |

| F6 | 2.14E−02 | 1.77E-03 | 2.09E-02 |

| F7 | 4.87E−03 | 5.92E−04 | 6.26E−04 |

| F8 | −6.81E + 03 | −6.97E + 03 | −7.48E + 03 |

| F9 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 |

| F10 | 2.80E−18 | 1.67E−21 | 9.04E−19 |

| F11 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 |

| F12 | 9.54E−02 | 9.13E−02 | 9.79E−02 |

| F13 | 2.98E−02 | 2.98E−02 | 7.00E−02 |

| F14 | 1.27E + 00 | 1.00E + 00 | 1.27E + 00 |

| F15 | 3.79E−04 | 3.44E−04 | 3.75E−04 |

| F16 | −1.03E + 00 | −1.03E + 00 | −1.03E + 00 |

| F17 | 3.98E−01 | 3.98E−01 | 3.98E−01 |

| F18 | 3.00E + 00 | 3.00E + 00 | 3.00E + 00 |

| F19 | −3.00E−01 | −2.29E + 00 | −1.16E + 00 |

| F20 | −3.28E + 00 | −3.31E + 00 | −3.30E + 00 |

| F21 | −6.06E + 00 | −9.01E + 00 | −5.96E + 00 |

| F22 | −9.03E + 00 | −1.01E + 01 | −8.09E + 00 |

| F23 | −8.13E + 00 | −8.21E + 00 | −8.00E + 00 |

In Eq. (18), the refraction index and the rate affect the position of the opposite solution in the search space. The refraction index is studied using 4 different values (). The rate is also set to the same values (). Different types of functions are tested to find the optimal combination of parameters and . Table 8 gives the results of average fitness values. As can be inferred from Table 8, IBMO with and obtains relatively weak results. Some similar results are obtained by other cases. Figure 10 is used to explain the impact of parameter combinations on the refraction-learning strategy. The current solution, the opposite solution, and the optimal solution are shown in Fig. 10. When and , Eq. (18) can be simplified to , and the opposite solution corresponding to the current solution is . By tuning parameters and , the opposite solution can be closer to the optimal solution. The proper combination of parameters increases the probability of escaping the local optimum. In addition, the larger and values result in unchanged in the performance of the algorithm. We finally use the values of 100 and 1000 for and , respectively.

Table 8.

Average fitness values of IBMO using different combinations of η and k

| F | η = 1, k = 1 | η = 1, k = 10 or η = 10, k = 1 | η = 10, k = 10 | η = 10, k = 100 or η = 100, k = 10 | η = 100, k = 100 | η = 100, k = 1000 or η = 1000, k = 100 | η = 1000, k = 1000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 5.99E−40 | 7.93E−199 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 |

| F2 | 7.37E−26 | 1.28E−99 | 8.72E−199 | 1.11E−296 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 |

| F3 | 1.72E−38 | 4.88E−199 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 |

| F4 | 2.15E−23 | 3.77E−100 | 2.03E−198 | 6.74E−298 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 |

| F5 | 2.83E + 01 | 2.79E + 01 | 2.83E + 01 | 2.84E + 01 | 2.80E + 01 | 2.60E + 01 | 2.85E + 01 |

| F6 | 1.56E + 00 | 2.00E + 00 | 1.45E + 00 | 1.78E + 00 | 1.76E + 00 | 1.77E−03 | 2.39E + 00 |

| F7 | 6.82E−04 | 3.75E−03 | 6.93E−04 | 1.29E−03 | 1.26E−03 | 5.92E−04 | 1.14E−03 |

| F8 | −7.27E + 03 | −6.95E + 03 | −6.59E + 03 | −6.90E + 03 | −6.95E + 03 | −6.97E + 03 | −6.56E + 03 |

| F9 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 |

| F10 | 8.88E−16 | 8.88E−16 | 8.88E−16 | 8.88E−16 | 8.88E−16 | 1.67E−21 | 8.88E−16 |

| F11 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 |

| F12 | 1.29E−01 | 1.03E−01 | 1.66E−01 | 1.10E−01 | 1.09E−01 | 9.13E−02 | 8.80E−02 |

| F13 | 2.98E + 00 | 2.97E + 00 | 2.97E + 00 | 2.98E + 00 | 2.97E + 00 | 2.98E−02 | 2.97E + 00 |

| F14 | 2.98E + 00 | 2.98E + 00 | 1.27E + 01 | 9.98E−01 | 1.08E + 01 | 1.00E + 00 | 9.98E−01 |

| F15 | 7.75E−04 | 6.04E−04 | 5.23E−04 | 7.52E−04 | 4.03E−04 | 3.44E−04 | 8.00E−04 |

| F16 | −1.03E + 00 | −1.03E + 00 | −1.03E + 00 | −1.03E + 00 | −1.03E + 00 | −1.03E + 00 | −1.03E + 00 |

| F17 | 3.98E−01 | 3.98E−01 | 3.98E−01 | 3.98E−01 | 3.98E−01 | 3.98E−01 | 3.98E−01 |

| F18 | 3.00E + 00 | 3.00E + 00 | 3.00E + 00 | 3.00E + 00 | 3.00E + 00 | 3.00E + 00 | 3.00E + 00 |

| F19 | −2.12E + 00 | −2.20E + 00 | −2.81E + 00 | −1.67E + 00 | −2.85E + 00 | −2.29E + 00 | −1.77E + 00 |

| F20 | −3.30E + 00 | −3.32E + 00 | −3.20E + 00 | −3.20E + 00 | −3.20E + 00 | −3.31E + 00 | −3.32E + 00 |

| F21 | −5.06E + 00 | −5.06E + 00 | −5.06E + 00 | −5.06E + 00 | −5.06E + 00 | −9.01E + 00 | −5.06E + 00 |

| F22 | −5.09E + 00 | −5.09E + 00 | −5.09E + 00 | −5.09E + 00 | −5.09E + 00 | −1.01E + 01 | −5.09E + 00 |

| F23 | −5.13E + 00 | −5.13E + 00 | −5.13E + 00 | −5.13E + 00 | −5.13E + 00 | −8.21E + 00 | −5.13E + 00 |

Fig. 10.

Comparison of the control parameters and

Impact of three strategies

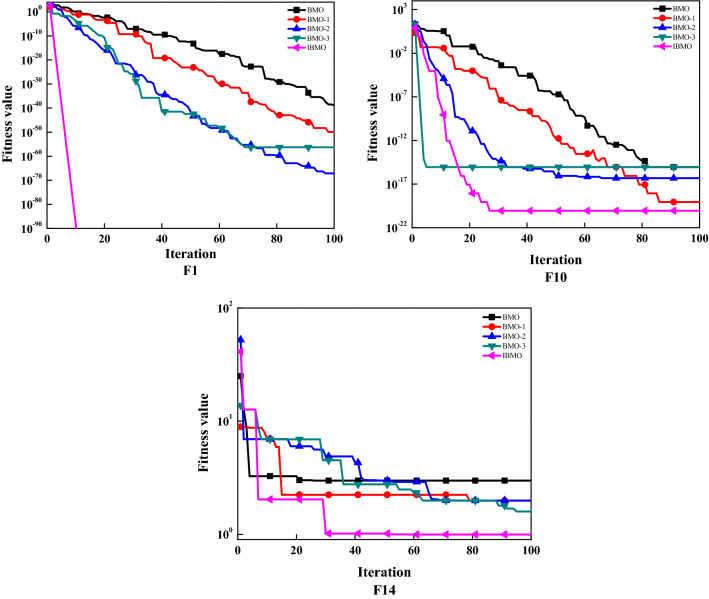

The purpose of this subsection is to study the impact of each improvement strategy. Five different types of algorithms are shown in Table 9. If the corresponding strategy is used in BMO, it is represented by "1." Otherwise it is represented by "0." 23 classical benchmark functions are implemented to evaluate performance. We report the average (avg) and standard deviation (std) of fitness values in Table 10. The best results are displayed in bold. By referring to Table 10, it can be found that IBMO’s avg and std are the smallest in most cases. BMO-1, BMO-2, and BMO-3 are also smaller than the native BMO. These promising results show that each strategy can improve the performance of the native algorithm, and the combination effect is better. Convergence accuracy and stability are the main gains. To visualize the data, Fig. 11 shows the trend of fitness values of F1, F10, and F14. In Sect. 4.2, the gain effect of each strategy has been analyzed and elaborated. Now, it is further confirmed by the convergence curve. To sum up, IBMO can achieve excellent performance on almost all benchmark functions, which can be concluded that the results are not accidental, and the improvement is significant.

Table 9.

Various BMOs with three strategies

| # | Algorithm | Gaussian mutation | Conversion parameter | Refraction-learning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BMO | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | BMO–1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | BMO–2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | BMO–3 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 5 | IBMO | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Table 10.

Results of fitness values of various BMOs

| F | BMO | BMO-1 | BMO-2 | BMO-3 | IBMO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | Avg | 1.12E-36 | 1.16E−37 | 1.00E−56 | 2.07E−49 | 0.00E + 00 |

| Std | 3.37E−36 | 2.24E−37 | 2.69E−56 | 7.84E−49 | 0.00E + 00 | |

| F2 | Avg | 9.33E−21 | 7.75E−22 | 3.17E−46 | 3.50E−30 | 0.00E + 00 |

| Std | 2.77E−20 | 1.55E−21 | 1.16E−46 | 7.21E−30 | 0.00E + 00 | |

| F3 | Avg | 1.00E−28 | 1.00E−34 | 1.90E−57 | 2.48E−53 | 0.00E + 00 |

| Std | 3.01E−28 | 2.75E−34 | 4.89E−57 | 9.68E−53 | 0.00E + 00 | |

| F4 | Avg | 8.18E−19 | 2.75E−19 | 1.04E−28 | 6.41E−27 | 0.00E + 00 |

| Std | 2.31E−18 | 7.43E−19 | 2.97E−28 | 1.58E−27 | 0.00E + 00 | |

| F5 | Avg | 2.84E + 01 | 2.82E + 01 | 2.83E + 01 | 2.74E + 01 | 2.60E + 01 |

| Std | 1.89E−01 | 3.04E−01 | 1.62E−01 | 2.83E−01 | 1.50E−01 | |

| F6 | Avg | 7.18E−02 | 2.23E−03 | 2.06E−03 | 2.28E−02 | 1.77E−03 |

| Std | 3.39E−01 | 3.05E−01 | 2.62E−01 | 3.47E−01 | 1.36E−01 | |

| F7 | Avg | 2.47E−03 | 1.18E−03 | 9.16E−04 | 1.40E−03 | 5.92E−04 |

| Std | 2.62E−03 | 1.04E−03 | 6.98E−04 | 9.19E−04 | 3.91E−04 | |

| F8 | Avg | −6.39E + 03 | −6.71E + 03 | −6.45E + 03 | −6.86E + 03 | −6.97E + 03 |

| Std | 1.05E + 03 | 4.48E + 02 | 5.34E + 02 | 6.99E + 02 | 4.24E + 02 | |

| F9 | Avg | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 |

| Std | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | |

| F10 | Avg | 8.88E−16 | 8.73E−20 | 4.25E−17 | 2.68E−16 | 1.67E−21 |

| Std | 3.98E−31 | 1.00E−33 | 2.81E−35 | 9.77E−36 | 3.02E−37 | |

| F11 | Avg | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 |

| Std | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | |

| F12 | Avg | 1.21E−01 | 1.16E−01 | 9.83E−02 | 1.42E−01 | 9.13E−02 |

| Std | 3.34E−02 | 3.13E−02 | 2.87E−02 | 5.35E−02 | 2.20E−02 | |

| F13 | Avg | 2.83E−01 | 2.75E−01 | 6.98E−02 | 3.90E−01 | 2.98E−02 |

| Std | 4.21E−01 | 4.30E−01 | 1.82E−03 | 1.91E−03 | 1.13E−03 | |

| F14 | Avg | 2.29E + 00 | 1.53E + 00 | 1.99E + 00 | 1.59E + 00 | 1.00E + 00 |

| Std | 1.33E + 00 | 4.69E + 00 | 4.99E + 00 | 3.31E + 00 | 3.53E−01 | |

| F15 | Avg | 7.13E−03 | 8.29E−04 | 3.81E−04 | 8.53E−04 | 3.44E−04 |

| Std | 1.53E−03 | 1.95E−04 | 1.27E−04 | 1.87E−04 | 5.12E−05 | |

| F16 | Avg | −1.03E + 00 | −1.03E + 00 | −1.03E + 00 | −1.03E + 00 | −1.03E + 00 |

| Std | 7.96E−19 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | |

| F17 | Avg | 3.98E−01 | 3.98E−01 | 3.98E−01 | 3.98E−01 | 3.98E−01 |

| Std | 2.06E−17 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | |

| F18 | Avg | 3.00E + 00 | 3.00E + 00 | 3.00E + 00 | 3.00E + 00 | 3.00E + 00 |

| Std | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | 0.00E + 00 | |

| F19 | Avg | −3.00E−01 | −1.28E + 00 | −3.00E−01 | −3.00E−01 | −2.29E + 00 |

| Std | 1.69E−16 | 1.04E−02 | 5.04E−18 | 9.01E−16 | 6.69E−20 | |

| F20 | Avg | −3.23E + 00 | −3.29E + 00 | −3.29E + 00 | −3.27E + 00 | −3.31E + 00 |

| Std | 6.82E−02 | 5.06E−02 | 5.45E−02 | 5.82E−02 | 4.67E−02 | |

| F21 | Avg | −5.57E + 00 | −5.99E + 00 | −7.06E + 00 | −6.06E + 00 | −9.01E + 00 |

| Std | 2.50E + 00 | 1.53E + 00 | 1.73E + 00 | 1.21E + 00 | 1.08E + 00 | |

| F22 | Avg | −6.15E + 00 | −7.09E + 00 | −9.02E + 00 | −6.19E + 00 | −1.01E + 01 |

| Std | 2.13E + 00 | 2.01E + 00 | 3.00E + 00 | 2.13E + 00 | 1.96E + 00 | |

| F23 | Avg | −6.21E + 00 | −7.73E + 00 | −8.13E + 00 | −6.94E + 00 | −8.21E + 00 |

| Std | 2.16E + 00 | 1.70E + 00 | 3.03E + 00 | 2.43E + 00 | 2.16E + 00 |

Fig. 11.

Convergence curves of various BMOs on F1, F10, and F14

Results on low-dimensional datasets

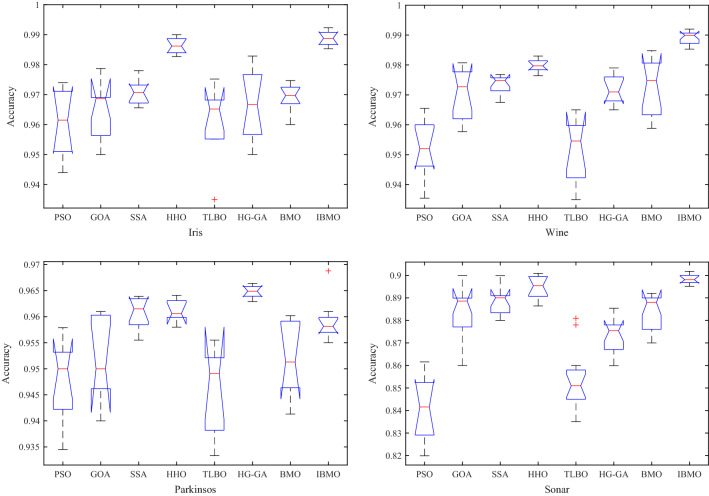

Sixteen low-dimensional datasets are used in this subsection to compare the performance of the proposed IBMO-SVM with novel compared algorithms. The quantitative and qualitative analyses are as follows. Table 11 shows the average and standard deviation of classification accuracy. Inspecting the results in this table, it can be observed that IBMO-SVM performs better than others. In terms of average, IBMO obtains the highest results on 68.75% of the datasets, while SSA, HHO, and HG-GA can outperform IBMO on 12.5%, 12.5%, and 6.25% of the datasets, respectively. In terms of standard deviation, IBMO-SVM obtains the smallest results on 62.5% of the datasets. Both optimizers obtain the same std value on one dataset (i.e., ILPD). Figure 12 exhibits the results of box charts of eight algorithms on Iris, Wine, Parkinsons, and Sonar. In these figures, it can be seen that IBMO can achieve higher and more centralized data, and no many outliers. The metric of classification accuracy proves the stability of IBMO and the capability to search the promising regions in the search space.

Table 11.

Comparison each algorithm based on classification accuracy

| Dataset | PSO | GOA | SSA | HHO | TLBO | HG-GA | BMO | IBMO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iris | Avg | 0.9640 | 0.9687 | 0.9722 | 0.9867 | 0.9652 | 0.9667 | 0.9707 | 0.9893 |

| Std | 0.0294 | 0.0129 | 0.0027 | 0.0014 | 0.0253 | 0.0158 | 0.0080 | 0.0012 | |

| Tic-tac-toe | Avg | 0.8954 | 0.9083 | 0.9106 | 0.9209 | 0.8998 | 0.9005 | 0.9010 | 0.9317 |

| Std | 0.0073 | 0.0051 | 0.0042 | 0.0027 | 0.0065 | 0.0045 | 0.0033 | 0.0019 | |

| Breast Cancer | Avg | 0.9561 | 0.9649 | 0.9690 | 0.9831 | 0.9575 | 0.9617 | 0.9578 | 0.9790 |

| Std | 0.0125 | 0.0010 | 0.0009 | 0.0003 | 0.0102 | 0.0044 | 0.0014 | 0.0005 | |

| ILPD | Avg | 0.7218 | 0.7372 | 0.7386 | 0.7413 | 0.7358 | 0.7338 | 0.7386 | 0.7458 |

| Std | 0.0045 | 0.0025 | 0.0023 | 0.0017 | 0.0038 | 0.0009 | 0.0028 | 0.0009 | |

| Wine | Avg | 0.9555 | 0.9777 | 0.9748 | 0.9794 | 0.9596 | 0.9710 | 0.9748 | 0.9899 |

| Std | 0.1169 | 0.1099 | 0.1005 | 0.0090 | 0.1109 | 0.0798 | 0.1048 | 0.0053 | |

| Congressional VR | Avg | 0.9733 | 0.9733 | 0.9707 | 0.9784 | 0.9690 | 0.9698 | 0.9733 | 0.9741 |

| Std | 0.0050 | 0.0017 | 0.0017 | 0.0012 | 0.0047 | 0.0039 | 0.0024 | 0.0015 | |

| Zoo | Avg | 0.9327 | 0.9584 | 0.9723 | 0.9861 | 0.9465 | 0.9525 | 0.9644 | 0.9892 |

| Std | 0.0290 | 0.0146 | 0.0074 | 0.0068 | 0.0179 | 0.0094 | 0.0101 | 0.0044 | |

| Lymphography | Avg | 0.7757 | 0.8054 | 0.8189 | 0.8297 | 0.7797 | 0.8027 | 0.8157 | 0.8324 |

| Std | 0.0359 | 0.0066 | 0.0051 | 0.0027 | 0.0150 | 0.0146 | 0.0060 | 0.0019 | |

| Hepatitis | Avg | 0.8625 | 0.8791 | 0.8800 | 0.8811 | 0.8708 | 0.8736 | 0.8795 | 0.8832 |

| Std | 0.0232 | 0.0168 | 0.0099 | 0.0082 | 0.0215 | 0.0170 | 0.0100 | 0.0061 | |

| Parkinsons | Avg | 0.9437 | 0.9597 | 0.9605 | 0.9621 | 0.9482 | 0.9649 | 0.9513 | 0.9579 |

| Std | 0.0390 | 0.0126 | 0.0077 | 0.0038 | 0.0205 | 0.0029 | 0.0141 | 0.0105 | |

| Flags | Avg | 0.6686 | 0.6689 | 0.6841 | 0.6948 | 0.6680 | 0.6742 | 0.6730 | 0.6959 |

| Std | 0.0787 | 0.0188 | 0.0378 | 0.0154 | 0.0436 | 0.0200 | 0.0241 | 0.0056 | |

| Dermatology | Avg | 0.9291 | 0.9542 | 0.9883 | 0.9855 | 0.9399 | 0.9497 | 0.9574 | 0.9643 |

| Std | 0.0480 | 0.0158 | 0.0392 | 0.0011 | 0.0308 | 0.0143 | 0.0242 | 0.0055 | |

| Ionosphere | Avg | 0.9288 | 0.9344 | 0.9612 | 0.9429 | 0.9299 | 0.9362 | 0.9371 | 0.9558 |

| Std | 0.1178 | 0.0777 | 0.0073 | 0.0400 | 0.0834 | 0.0827 | 0.0539 | 0.0228 | |

| Soybean small | Avg | 0.9749 | 0.9891 | 0.9957 | 0.9980 | 0.9857 | 0.9866 | 0.9900 | 0.9996 |

| Std | 0.1392 | 0.0073 | 0.0051 | 0.0027 | 0.0085 | 0.0081 | 0.0049 | 0.0025 | |

| Lung cancer | Avg | 0.5438 | 0.5687 | 0.5838 | 0.6184 | 0.5575 | 0.5550 | 0.6313 | 0.6688 |

| Std | 0.0750 | 0.0500 | 0.0276 | 0.0306 | 0.0606 | 0.0480 | 0.0419 | 0.0250 | |

| Sonar | Avg | 0.8416 | 0.8886 | 0.8900 | 0.8904 | 0.8510 | 0.8754 | 0.8898 | 0.8981 |

| Std | 0.1140 | 0.0671 | 0.0559 | 0.0496 | 0.0887 | 0.0736 | 0.0524 | 0.0024 | |

Fig. 12.

Box charts of each algorithm on Iris, Wine, Parkinsons, and Sonar

The number of selected features is another important metric for wrapper FS methods. Table 12 shows a comparison for the average number of selected features on all datasets. Further analyzing reported results, IBMO can select the most significant features on 11 out of 16 datasets. But for the Breast Cancer dataset, our method also ranks the second. Based on the results obtained, it can be observed that IBMO significantly outperforms others in minimizing the number of selected features.

Table 12.

Comparison each algorithm based on the average number of selected features

| Dataset | PSO | GOA | SSA | HHO | TLBO | HG-GA | BMO | IBMO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iris | 2.22 | 1.61 | 1.47 | 1.20 | 2.07 | 1.88 | 1.56 | 1.10 |

| Tic-tac-toe | 6.21 | 5.77 | 5.45 | 4.81 | 5.95 | 5.60 | 5.07 | 4.66 |

| Breast Cancer | 5.98 | 4.24 | 4.02 | 3.50 | 5.67 | 5.01 | 3.93 | 3.70 |

| ILPD | 6.20 | 4.82 | 4.66 | 4.44 | 5.79 | 5.02 | 5.33 | 4.40 |

| Wine | 8.36 | 6.34 | 5.99 | 5.88 | 8.21 | 8.63 | 6.22 | 5.60 |

| Congressional VR | 7.90 | 5.53 | 5.31 | 4.70 | 8.23 | 6.42 | 5.48 | 5.20 |

| Zoo | 9.74 | 6.06 | 5.60 | 5.56 | 11.80 | 8.64 | 6.01 | 5.40 |

| Lymphography | 11.40 | 7.86 | 7.22 | 6.74 | 11.05 | 8.98 | 6.96 | 6.43 |

| Hepatitis | 9.80 | 7.55 | 7.02 | 6.87 | 8.44 | 6.04 | 7.31 | 5.89 |

| Parkinsons | 12.20 | 9.00 | 8.89 | 8.61 | 16.86 | 8.22 | 11.61 | 9.17 |

| Flags | 18.47 | 11.60 | 10.20 | 9.62 | 15.67 | 13.00 | 12.60 | 9.09 |

| Dermatology | 15.60 | 12.42 | 8.49 | 10.66 | 21.28 | 13.60 | 10.82 | 9.40 |

| Ionosphere | 17.20 | 11.60 | 7.60 | 9.42 | 15.31 | 14.20 | 10.82 | 8.80 |

| Soybean small | 22.06 | 13.88 | 13.07 | 12.00 | 19.86 | 16.64 | 13.60 | 10.09 |

| Lung cancer | 28.00 | 24.80 | 22.09 | 21.40 | 26.81 | 24.64 | 25.33 | 18.65 |

| Sonar | 30.86 | 24.00 | 24.42 | 21.81 | 29.48 | 26.44 | 23.41 | 20.04 |

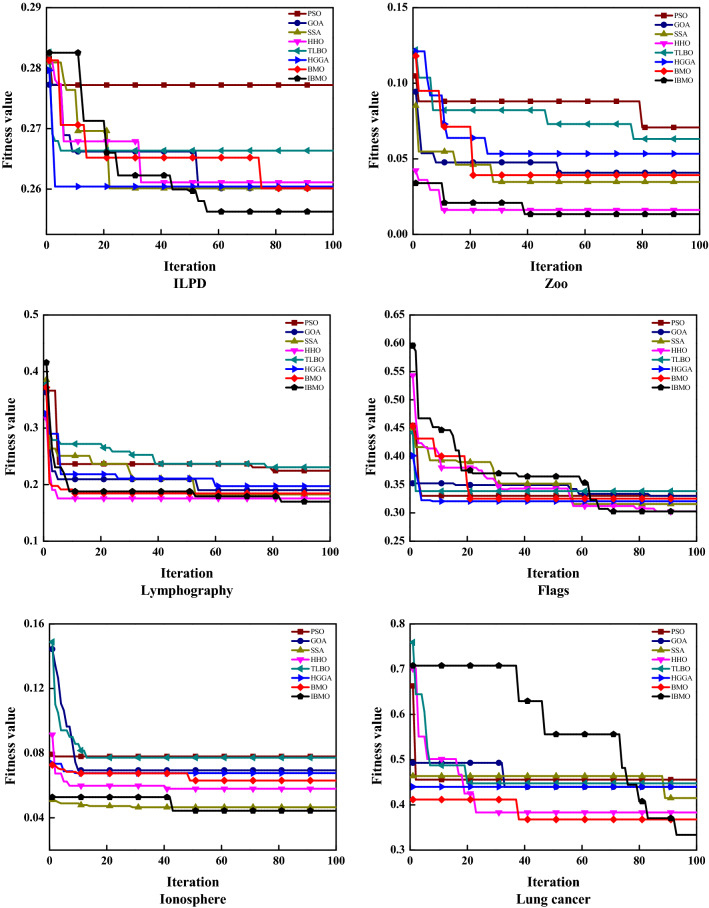

The fitness function involves two metrics: classification accuracy and feature selection ratio. Table 13 presents the best, worst, avg, and std of fitness values of eight algorithms. IBMO contributes to the best fitness values on 56.25% of the datasets, the lowest avg values on 68.75% of the datasets, and the lowest std values on 75% of the datasets. Thus, IBMO perceives the most consistent results. Figure 13 compares the convergence behavior of different algorithms. As can be seen from Fig. 13, IBMO provides the lowest position curves compared with other state-of-the-art algorithms, and occasionally escapes from the local optimum to continue searching effective spaces. Overall, IBMO-SVM shows the best convergence behavior on real-world datasets. This also indicates the substantial impact of the proposed improvements on the native BMO.

Table 13.

Comparison each algorithm based on fitness values

| Dataset | PSO | GOA | SSA | HHO | TLBO | HG-GA | BMO | IBMO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iris | Best | 0.0387 | 0.0214 | 0.0307 | 0.0152 | 0.0282 | 0.0237 | 0.0180 | 0.0114 |

| Worst | 0.0519 | 0.0519 | 0.0453 | 0.0232 | 0.0332 | 0.0319 | 0.0353 | 0.0253 | |

| Avg | 0.0493 | 0.0349 | 0.0340 | 0.0177 | 0.0312 | 0.0303 | 0.0318 | 0.0192 | |

| Std | 0.0116 | 0.0093 | 0.0053 | 0.0019 | 0.0069 | 0.0040 | 0.0033 | 0.0016 | |

| Tic-tac-toe | Best | 0.0970 | 0.0955 | 0.0909 | 0.0533 | 0.1010 | 0.1009 | 0.0998 | 0.0686 |

| Worst | 0.1223 | 0.1101 | 0.1034 | 0.1009 | 0.2100 | 0.1134 | 0.1102 | 0.0809 | |

| Avg | 0.1174 | 0.0972 | 0.0934 | 0.0837 | 0.1050 | 0.1096 | 0.1025 | 0.0700 | |

| Std | 0.0753 | 0.0050 | 0.0046 | 0.0031 | 0.0056 | 0.0040 | 0.0039 | 0.0011 | |

| Breast Cancer | Best | 0.0589 | 0.0320 | 0.0301 | 0.0186 | 0.0445 | 0.0428 | 0.0428 | 0.0188 |

| Worst | 0.0489 | 0.0444 | 0.0408 | 0.0262 | 0.0490 | 0.0512 | 0.0457 | 0.0248 | |

| Avg | 0.0533 | 0.0395 | 0.0328 | 0.0228 | 0.0468 | 0.0445 | 0.0440 | 0.0228 | |

| Std | 0.0033 | 0.0016 | 0.0014 | 0.0011 | 0.0025 | 0.0019 | 0.0018 | 0.0010 | |

| ILPD | Best | 0.2780 | 0.2601 | 0.2601 | 0.2619 | 0.2591 | 0.2577 | 0.2601 | 0.2580 |

| Worst | 0.2858 | 0.2652 | 0.2646 | 0.2687 | 0.2816 | 0.2679 | 0.2638 | 0.2604 | |

| Avg | 0.2816 | 0.2624 | 0.2612 | 0.2639 | 0.2659 | 0.2625 | 0.2618 | 0.2595 | |

| Std | 0.0028 | 0.0024 | 0.0020 | 0.0025 | 0.0045 | 0.0032 | 0.0017 | 0.0010 | |

| Wine | Best | 0.0312 | 0.0184 | 0.0199 | 0.0167 | 0.0328 | 0.0191 | 0.0183 | 0.0099 |

| Worst | 0.0605 | 0.0431 | 0.0412 | 0.0287 | 0.0469 | 0.0457 | 0.0476 | 0.0201 | |

| Avg | 0.0525 | 0.0270 | 0.0271 | 0.0269 | 0.0439 | 0.0376 | 0.0276 | 0.0119 | |

| Std | 0.1152 | 0.0508 | 0.0320 | 0.0144 | 0.0985 | 0.0745 | 0.0245 | 0.0098 | |

| Congressional VR | Best | 0.0315 | 0.0281 | 0.0275 | 0.0196 | 0.0330 | 0.0287 | 0.0281 | 0.0196 |

| Worst | 0.0461 | 0.0324 | 0.0336 | 0.0324 | 0.0380 | 0.0349 | 0.0324 | 0.0281 | |

| Avg | 0.0383 | 0.0295 | 0.0319 | 0.0290 | 0.0364 | 0.0308 | 0.0292 | 0.0241 | |

| Std | 0.0058 | 0.0015 | 0.0024 | 0.0015 | 0.0049 | 0.0021 | 0.0036 | 0.0017 | |

| Zoo | Best | 0.0430 | 0.0232 | 0.0244 | 0.0138 | 0.0596 | 0.0363 | 0.0334 | 0.0127 |

| Worst | 0.1214 | 0.0532 | 0.0428 | 0.0300 | 0.0694 | 0.0572 | 0.0534 | 0.0140 | |

| Avg | 0.0708 | 0.0408 | 0.0347 | 0.0162 | 0.0673 | 0.0506 | 0.0392 | 0.0136 | |

| Std | 0.0287 | 0.0144 | 0.0068 | 0.0084 | 0.0039 | 0.0079 | 0.0104 | 0.0009 | |

| Lymphography | Best | 0.1767 | 0.1901 | 0.1812 | 0.1620 | 0.2239 | 0.1768 | 0.1700 | 0.1572 |

| Worst | 0.2776 | 0.2046 | 0.1940 | 0.1905 | 0.2300 | 0.2180 | 0.1968 | 0.1767 | |

| Avg | 0.2217 | 0.1982 | 0.1862 | 0.1766 | 0.2269 | 0.2054 | 0.1823 | 0.1689 | |

| Std | 0.0356 | 0.0067 | 0.0046 | 0.0117 | 0.0020 | 0.0151 | 0.0088 | 0.0074 | |

| Hepatitis | Best | 0.1174 | 0.1060 | 0.1016 | 0.0950 | 0.1346 | 0.0985 | 0.1216 | 0.0816 |

| Worst | 0.1572 | 0.1488 | 0.1414 | 0.1430 | 0.1377 | 0.1572 | 0.1340 | 0.1469 | |

| Avg | 0.1412 | 0.1237 | 0.1224 | 0.1203 | 0.1355 | 0.1298 | 0.1268 | 0.1179 | |

| Std | 0.0241 | 0.0189 | 0.0172 | 0.0144 | 0.0223 | 0.0211 | 0.0166 | 0.0120 | |

| Parkinsons | Best | 0.0570 | 0.0312 | 0.0337 | 0.0338 | 0.0523 | 0.0312 | 0.0359 | 0.0370 |

| Worst | 0.0996 | 0.0662 | 0.0562 | 0.0432 | 0.0616 | 0.0493 | 0.0655 | 0.0610 | |

| Avg | 0.0678 | 0.0459 | 0.0425 | 0.0414 | 0.0581 | 0.0396 | 0.0521 | 0.0490 | |

| Std | 0.0103 | 0.0079 | 0.0040 | 0.0032 | 0.0097 | 0.0030 | 0.0038 | 0.0036 | |

| Flags | Best | 0.3221 | 0.2982 | 0.2635 | 0.2807 | 0.3277 | 0.3132 | 0.3002 | 0.2621 |

| Worst | 0.4895 | 0.3543 | 0.3600 | 0.3247 | 0.3398 | 0.3507 | 0.3323 | 0.3120 | |

| Avg | 0.3303 | 0.3301 | 0.3156 | 0.3025 | 0.3385 | 0.3205 | 0.3254 | 0.3025 | |

| Std | 0.0786 | 0.0189 | 0.0163 | 0.0077 | 0.0373 | 0.0176 | 0.0038 | 0.0022 | |

| Dermatology | Best | 0.0293 | 0.0196 | 0.0084 | 0.0111 | 0.0567 | 0.0278 | 0.0305 | 0.0238 |

| Worst | 0.0800 | 0.0672 | 0.0455 | 0.0177 | 0.0757 | 0.0803 | 0.0881 | 0.0418 | |

| Avg | 0.0748 | 0.0465 | 0.0140 | 0.0156 | 0.0691 | 0.0500 | 0.0440 | 0.0372 | |

| Std | 0.0469 | 0.0180 | 0.0392 | 0.0199 | 0.0494 | 0.0238 | 0.0206 | 0.0159 | |

| Ionosphere | Best | 0.0638 | 0.0585 | 0.0392 | 0.0438 | 0.0467 | 0.0399 | 0.0404 | 0.0349 |

| Worst | 0.1500 | 0.1151 | 0.1029 | 0.0754 | 0.1005 | 0.0824 | 0.0913 | 0.0648 | |

| Avg | 0.0780 | 0.0694 | 0.0465 | 0.0580 | 0.0772 | 0.0677 | 0.0631 | 0.0444 | |

| Std | 0.0987 | 0.0821 | 0.0770 | 0.0555 | 0.0924 | 0.0798 | 0.0817 | 0.0349 | |

| Soybean small | Best | 0.0243 | 0.0036 | 0.0034 | 0.0021 | 0.0157 | 0.0129 | 0.0129 | 0.0034 |

| Worst | 0.3029 | 0.0277 | 0.0245 | 0.0070 | 0.0191 | 0.0345 | 0.0149 | 0.0051 | |

| Avg | 0.0384 | 0.0148 | 0.0082 | 0.0051 | 0.0174 | 0.0179 | 0.0139 | 0.0042 | |

| Std | 0.0030 | 0.0018 | 0.0013 | 0.0018 | 0.0042 | 0.0021 | 0.0007 | 0.0006 | |

| Lung cancer | Best | 0.3070 | 0.4292 | 0.3893 | 0.3263 | 0.4192 | 0.3902 | 0.3292 | 0.1504 |

| Worst | 0.4941 | 0.4404 | 0.4839 | 0.4842 | 0.4809 | 0.4532 | 0.3941 | 0.3906 | |

| Avg | 0.4557 | 0.4398 | 0.4151 | 0.3834 | 0.4477 | 0.4400 | 0.3679 | 0.3336 | |

| Std | 0.0743 | 0.0400 | 0.0314 | 0.0388 | 0.0608 | 0.0354 | 0.0974 | 0.0309 | |

| Sonar | Best | 0.0948 | 0.0532 | 0.0471 | 0.0432 | 0.0757 | 0.0697 | 0.0823 | 0.0384 |

| Worst | 0.2070 | 0.1857 | 0.2154 | 0.1416 | 0.1704 | 0.1543 | 0.1600 | 0.1352 | |

| Avg | 0.1659 | 0.1102 | 0.1125 | 0.1139 | 0.1576 | 0.1299 | 0.1134 | 0.1029 | |

| Std | 0.0883 | 0.0774 | 0.0628 | 0.0116 | 0.0830 | 0.0592 | 0.0422 | 0.0113 | |

Fig. 13.

Convergence curves of each algorithm on ILPD, Zoo, Lymphography, Flags, Ionosphere, and Lung cancer

Running time metric indicates the execution speed of an algorithm. The average running time (in second) is given in Table 14. Taking Zoo dataset as an example, the running time is sorted as follows: TLBO > SSA > GOA > BMO > IBMO > PSO > HG-GA > HHO. Table 14 shows that for almost all datasets, the running time by the proposed method is ranked in the middle of the eight algorithms. In addition, the running time of IBMO is slightly higher than that of BMO. We have analyzed the time complexity in Sect. 4.2.5, and the combination of three strategies leads to these slight changes. To improve the overall performance of BMO, it cannot guarantee to obtain all optimal parameters on all cases. So the running time of IBMO is acceptable.

Table 14.

Comparison each algorithm based on average running time (in second)

| Dataset | PSO | GOA | SSA | HHO | TLBO | HG-GA | BMO | IBMO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iris | 31.01 | 28.93 | 29.78 | 42.34 | 28.17 | 29.66 | 25.90 | 26.15 |

| Tic-tac-toe | 711.36 | 406.69 | 407.40 | 1022.54 | 403.51 | 983.22 | 403.58 | 444.54 |

| Breast Cancer | 213.47 | 144.99 | 155.78 | 335.95 | 162.98 | 225.40 | 140.00 | 158.36 |

| ILPD | 240.68 | 208.91 | 217.87 | 474.93 | 196.91 | 237.18 | 225.72 | 228.19 |

| Wine | 37.44 | 37.40 | 37.39 | 60.76 | 35.77 | 49.12 | 36.49 | 37.20 |

| Congressional VR | 44.16 | 22.76 | 22.94 | 66.87 | 21.67 | 37.35 | 22.32 | 24.18 |

| Zoo | 31.29 | 27.67 | 27.45 | 56.04 | 26.07 | 41.84 | 27.82 | 29.88 |

| Lymphography | 39.76 | 34.33 | 36.38 | 65.61 | 35.19 | 42.75 | 35.92 | 37.63 |

| Hepatitis | 7.87 | 7.50 | 7.44 | 21.66 | 6.75 | 14.13 | 7.06 | 7.25 |

| Parkinsons | 37.19 | 28.46 | 29.11 | 65.44 | 27.65 | 40.70 | 27.03 | 27.45 |

| Flags | 117.67 | 90.44 | 103.11 | 175.02 | 100.69 | 128.24 | 103.00 | 113.70 |

| Dermatology | 266.10 | 206.43 | 214.18 | 270.56 | 211.24 | 260.53 | 233.82 | 237.77 |

| Ionosphere | 156.76 | 129.17 | 137.96 | 204.64 | 130.31 | 171.01 | 127.21 | 128.16 |

| Soybean small | 10.78 | 10.63 | 10.80 | 23.47 | 9.69 | 20.56 | 9.71 | 10.03 |

| Lung cancer | 6.39 | 6.17 | 6.41 | 16.58 | 5.81 | 11.93 | 5.79 | 6.11 |

| Sonar | 80.47 | 74.53 | 74.62 | 134.37 | 66.45 | 113.75 | 68.66 | 73.77 |

To detect significant differences between proposed IBMO-SVM versus compared algorithms, we apply a statistical test based on the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The null hypothesis represents the statement of no difference, whereas the alternative hypothesis represents the presence of significant differences. A p-value represents the probability of observing given results at the 0.05 significance level. The p-value less than 0.05 represents a strong evidence against [60, 61]. Table 15 exhibits the results, where the p-value greater than 0.05 is bold. According to this table, the superiority of IBMO-SVM is statistically significant on most the datasets because most of the p-values are less than 0.05. On the whole, it is observed from the above study that the overall performance of IBMO-SVM is better than other compared algorithms for all evaluation metrics on the low-dimensional datasets.

Table 15.

P-values of the IBMO with compared algorithms

| Dataset | PSO | GOA | SSA | HHO | TLBO | HG-GA | BMO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iris | 6.35E-09 | 7.48E-11 | 9.38E-10 | 2.71E-13 | 4.60E-08 | 2.07E-11 | 6.43E-10 |

| Tic-tac-toe | 1.58E-12 | 5.46E-13 | 7.20E-13 | 3.18E-14 | 1.67E-10 | 9.85E-11 | 2.04E-09 |

| Breast Cancer | 1.94E-04 | 8.25E-07 | 4.71E-08 | 1.80E-09 | 6.28E-03 | 5.37E-06 | 4.01E-05 |

| ILPD | 1.35E-07 | 1.35E-06 | 1.28E-03 | 1.99E-11 | 3.31E-08 | 4.81E-02 | 4.27E-08 |

| Wine | 9.03E-13 | 7.64E-12 | 1.85E-13 | 5.50E-05 | 2.85E-04 | 9.00E-07 | 3.81E-09 |

| Congressional VR | 1.75E-02 | 5.98E-03 | 2.43E-03 | 7.43E-06 | 8.65E-02 | 1.29E-04 | 6.75E-06 |

| Zoo | 1.15E-05 | 2.47E-09 | 3.18E-09 | 8.63E-12 | 7.00E-04 | 2.24E-08 | 8.15E-08 |

| Lymphography | 3.16E-04 | 1.73E-06 | 2.00E-06 | 3.89E-09 | 1.55E-03 | 2.27E-07 | 5.24E-01 |

| Hepatitis | 1.43E-11 | 5.98E-11 | 6.72E-12 | 3.62E-13 | 5.19E-11 | 7.80E-10 | 2.22E-11 |

| Parkinsons | 6.64E-06 | 2.11E-07 | 3.75E-07 | 9.14E-09 | 7.53E-06 | 1.40E-06 | 7.08E-08 |

| Flags | 4.66E-03 | 3.12E-03 | 9.81E-01 | 1.11E-01 | 2.60E-03 | 2.84E-04 | 4.17E-01 |

| Dermatology | 1.00E-09 | 2.39E-13 | 6.71E-08 | 4.95E-14 | 7.81E-10 | 5.42E-12 | 4.35E-10 |

| Ionosphere | 2.71E-04 | 4.27E-05 | 4.16E-02 | 1.32E-11 | 1.03E-08 | 3.12E-09 | 2.39E-06 |

| Soybean small | 8.70E-03 | 5.34E-06 | 6.30E-05 | 2.03E-05 | 9.12E-02 | 3.56E-04 | 2.50E-05 |

| Lung cancer | 1.12E-10 | 1.07E-11 | 6.11E-11 | 7.02E-14 | 1.02E-08 | 2.67E-14 | 1.34E-10 |

| Sonar | 5.18E-14 | 9.72E-07 | 4.35E-08 | 6.87E-02 | 1.54E-11 | 8.43E-10 | 6.79E-08 |

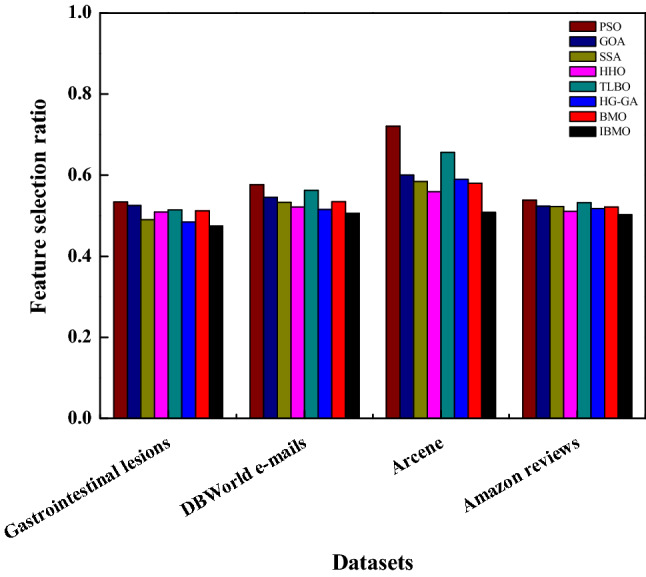

Results on high-dimensional datasets

After analyzing the above results, four high-dimensional datasets are implemented to further evaluate the overall performance of the proposed algorithm. It is a challenging task that can make the experiments more comprehensive and the results more convincing.

For high-dimensional datasets, the dimension of feature vectors is often larger than the capacity of available training samples. In the classification task, it often leads to the curse of dimensionality or empty space phenomenon [30]. Only a few of the thousands of features are important. Many classification methods with good performance become poor or even fail on testing high-dimensional datasets. This is the motivation and design purpose of this subsection. Further, the brief description of four high-dimensional datasets is shown in Table 16.

Table 16.

Description of four high-dimensional datasets [56]

| Dataset | Brief description |

|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal lesions | This dataset contains the features extracted from a database of colonoscopic videos showing gastrointestinal lesions. There are features vectors for 76 lesions, and there are 3 types of lesions: hyperplasic, adenoma, and serrated adenoma |

| DBWorld e-mails | This dataset contains 64 e-mails from DBWorld newsletter. We use them to train different algorithms in order to classify between "announces of conferences" and "everything else" |

| Arcene | Arcene is obtained by merging three mass spectrometry datasets. The original features show the abundance of proteins in human sera having a given mass value. Based on these features, cancer patients and healthy patients should be separated |

| Amazon reviews | This dataset is derived from the reviews in Amazon Commerce Website for authorship identification. It identifies 50 of the most active users. The number of reviews collected for each author is 30 |

Table 17 compares the average and standard deviation of classification accuracy based on four high-dimensional datasets. Figure 14 also shows the feature selection ratio. Observing the results in Table 17 and Fig. 14, it can be seen that IBMO is far superior to other competitors in dealing with high-dimensional datasets. Taking the Gastrointestinal lesions dataset as an example, the accuracy of IBMO is improved by 3.59% based on the native algorithm. Compared with PSO, IBMO is no less than 10% higher. Analyzing the number of features, for the Arcene dataset, the feature selection ratio of IBMO is 0.51 and is ranked first. Generally, HHO is also a good FS method with strong competitiveness. The fitness function is a comprehensive measure of the above two metrics. These results are shown in Table 18. It is not hard to see that the results are consistent and significant, and IBMO is still the champion algorithm.

Table 17.

Comparison each algorithm based on classification accuracy on high-dimensional datasets

| Dataset | PSO | GOA | SSA | HHO | TLBO | HG-GA | BMO | IBMO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal lesions | avg | 0.7651 | 0.8454 | 0.8500 | 0.8588 | 0.7840 | 0.8364 | 0.8409 | 0.8768 |

| std | 0.2334 | 0.1567 | 0.1200 | 0.0829 | 0.1431 | 0.1007 | 0.0955 | 0.0493 | |

| DBWorld e-mails | avg | 0.9275 | 0.9608 | 0.9677 | 0.9731 | 0.9483 | 0.9500 | 0.9625 | 0.9822 |

| std | 0.0040 | 0.0035 | 0.0087 | 0.0030 | 0.0051 | 0.0024 | 0.0037 | 0.0009 | |

| Arcene | avg | 0.8756 | 0.8830 | 0.9181 | 0.9044 | 0.8711 | 0.8814 | 0.8904 | 0.9429 |

| std | 0.0194 | 0.0188 | 0.0162 | 0.0093 | 0.0190 | 0.0175 | 0.0160 | 0.0080 | |

| Amazon reviews | avg | 0.6977 | 0.7632 | 0.7862 | 0.8008 | 0.7415 | 0.7717 | 0.7813 | 0.8164 |

| std | 0.1091 | 0.0800 | 0.0978 | 0.0646 | 0.1104 | 0.0593 | 0.0709 | 0.0138 | |

Fig. 14.

Comparison each algorithm based on feature selection ratio on high-dimensional datasets

Table 18.

Comparison each algorithm based on fitness values on high-dimensional datasets

| Dataset | PSO | GOA | SSA | HHO | TLBO | HG-GA | BMO | IBMO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal lesions | avg | 0.2374 | 0.1553 | 0.1532 | 0.1479 | 0.2093 | 0.1669 | 0.1631 | 0.1270 |

| std | 0.2205 | 0.0576 | 0.0330 | 0.0150 | 0.1444 | 0.0463 | 0.0297 | 0.0066 | |

| DBWorld e-mails | avg | 0.0752 | 0.0418 | 0.0344 | 0.0320 | 0.0569 | 0.0545 | 0.0427 | 0.0232 |

| std | 0.0207 | 0.0075 | 0.0046 | 0.0029 | 0.0100 | 0.0057 | 0.0064 | 0.0028 | |

| Arcene | avg | 0.1310 | 0.1217 | 0.0871 | 0.1006 | 0.1342 | 0.1230 | 0.1145 | 0.0624 |

| std | 0.0784 | 0.0625 | 0.0500 | 0.0178 | 0.0502 | 0.0441 | 0.0479 | 0.0226 | |

| Amazon reviews | avg | 0.3104 | 0.2399 | 0.2162 | 0.2031 | 0.2627 | 0.2318 | 0.2220 | 0.1879 |

| std | 0.0105 | 0.0082 | 0.0079 | 0.0077 | 0.0146 | 0.0093 | 0.0088 | 0.0060 | |

Friedman’s test is a nonparametric statistical inference technique. It involves first ranking the data and then testing to see whether () samples are significantly different. Equation (22) is used to compute the Friedman statistic for samples with m sample size. represents the rank obtained. follows distribution with degrees of freedom . When , the null hypothesis can be rejected at 0.05 significance level [61].

| 22 |

Using the data obtained above as input, Table 19 provides the results of additional statistics structure, and Table 20 shows the ranking obtained by Friedman’s test. When the degree of freedom is 7 and the significance level is 0.05, the critical value of the test statistic is 14.067. The calculated Chi-square statistic is greater than 14.067, so the null hypothesis can be rejected. Moreover, small p-values cast doubt on the validity of . In terms of the ranking obtained, IBMO has obtained the highest ranking and always shows excellent performance.

Table 19.

Results of additional statistics structure

| Dataset | Chi-square | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal lesions | 29.53 | 1.1562E-04 |

| DBWorld e-mails | 27.80 | 2.3902E-04 |

| Arcene | 30.87 | 6.5795E-05 |

| Amazon reviews | 30.67 | 7.1619E-05 |

Table 20.

Results of ranking values based on Friedman’s test

| Dataset | PSO | GOA | SSA | HHO | TLBO | HG-GA | BMO | IBMO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal lesions | 8.0 | 5.6 | 3.6 | 2.4 | 6.6 | 4.6 | 4.2 | 1.0 |

| DBWorld e-mails | 7.6 | 5.2 | 4.2 | 2.4 | 7.0 | 4.0 | 4.6 | 1.0 |

| Arcene | 7.6 | 5.8 | 3.4 | 2.2 | 7.2 | 5.0 | 3.6 | 1.2 |

| Amazon reviews | 7.6 | 5.4 | 4.0 | 2.2 | 7.4 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 1.0 |

Comparison with other classifiers

To comprehensively verify the effectiveness, the proposed model is further compared with 4 other classifiers, including logistic regression (LR) [62], decision tree (DT) [13], feedforward neural network (FNN) [18], and k-nearest neighbor (kNN) [16]. To achieve a fair comparison, IBMO is also used for other classifiers with default parameter values to find feature subsets. k = 5 for kNN is used in this work. For each method, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity are used to evaluate the performance. The sensitivity can describe the proportion of the identified positive classes to all positive classes, so it is also called the true positive rate. The sensitivity can present the proportion of the identified negative classes to all negative classes, so it is also called the true negative rate. They are defined in Eqs. (23) and (24), respectively.

| 23 |

| 24 |

where represents the true positive, represents the false negative, represents the true negative, and represents the false positive.

Tables 21, 22, 23 report experimental results based on 10 binary-class datasets. Regarding accuracy, our proposed method accomplishes the higher results on all datasets in comparison with 4 other classifiers. In terms of sensitivity, our proposed method accomplishes the higher results on 70% of the datasets. On the Ionosphere dataset, even that our proposed method does not achieve better than kNN, but it ranks second. While looking at the specificity, our proposed method outperforms others on 90% of the datasets and achieves the best results with 1.000 of sensitivity on the DBWorld e-mails dataset. To sum up, our proposed method proves highly competitive results, and can more accurately identify positives and negatives.

Table 21.

Comparison each classifier based on average accuracy on bi-class datasets

| Dataset | LR | DT | FNN | kNN | Our |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tic-tac-toe | 0.7098 | 0.8225 | 0.8935 | 0.8594 | 0.9317 |

| Breast Cancer | 0.9585 | 0.9471 | 0.9628 | 0.9571 | 0.9790 |

| ILPD | 0.5575 | 0.6449 | 0.7135 | 0.6690 | 0.7458 |

| Congressional VR | 0.9306 | 0.9569 | 0.9698 | 0.9310 | 0.9741 |

| Hepatitis | 0.8461 | 0.8375 | 0.8750 | 0.8500 | 0.8832 |

| Parkinsons | 0.8236 | 0.8808 | 0.8513 | 0.8923 | 0.9579 |

| Ionosphere | 0.8815 | 0.8932 | 0.9218 | 0.9347 | 0.9558 |

| Sonar | 0.6875 | 0.7403 | 0.7596 | 0.8173 | 0.8981 |

| DBWorld e-mails | 0.9414 | 0.9473 | 0.9725 | 0.9786 | 0.9822 |

| Arcene | 0.9134 | 0.9100 | 0.9240 | 0.9367 | 0.9429 |

Table 22.

Comparison each classifier based on average sensitivity on bi-class datasets

| Dataset | LR | DT | FNN | kNN | Our |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tic-tac-toe | 0.9776 | 0.8898 | 1.0000 | 0.9784 | 1.0000 |

| Breast Cancer | 0.9520 | 0.9563 | 0.9738 | 0.9651 | 0.9821 |

| ILPD | 0.4014 | 0.7692 | 1.0000 | 0.8053 | 0.8712 |

| Congressional VR | 0.9777 | 0.9630 | 0.9907 | 0.9896 | 1.0000 |

| Hepatitis | 0.5898 | 0.6154 | 0.6385 | 0.6615 | 0.7607 |

| Parkinsons | 0.7292 | 0.7708 | 0.8717 | 0.8958 | 0.9250 |

| Ionosphere | 0.7637 | 0.8888 | 0.9013 | 1.0000 | 0.9548 |

| Sonar | 0.8041 | 0.7320 | 0.7113 | 0.7526 | 0.8650 |

| DBWorld e-mails | 0.8401 | 0.8903 | 0.9167 | 0.9539 | 0.9875 |

| Arcene | 0.7313 | 0.7934 | 0.8026 | 0.8452 | 0.8905 |

Table 23.

Comparison each classifier based on average specificity on bi-class datasets

| Dataset | LR | DT | FNN | kNN | Our |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tic-tac-toe | 0.7048 | 0.6958 | 0.7211 | 0.7350 | 0.7546 |

| Breast Cancer | 0.9363 | 0.9295 | 0.9497 | 0.9419 | 0.9710 |

| ILPD | 0.9461 | 0.3353 | 0.4545 | 0.3293 | 0.5455 |

| Congressional VR | 0.8400 | 0.8613 | 0.9261 | 0.9032 | 0.9535 |

| Hepatitis | 0.8724 | 0.8806 | 0.9403 | 0.9254 | 0.9699 |

| Parkinsons | 0.9327 | 0.9320 | 0.9728 | 0.9456 | 0.9921 |

| Ionosphere | 0.7967 | 0.8174 | 0.9384 | 0.9603 | 0.9767 |

| Sonar | 0.7855 | 0.7477 | 0.8018 | 0.8738 | 0.8800 |

| DBWorld e-mails | 0.8833 | 0.9132 | 0.9367 | 0.9876 | 1.0000 |

| Arcene | 0.7955 | 0.8089 | 0.8499 | 0.8656 | 0.9076 |

Conclusions and future works

This paper proposes a novel classification model using IBMO for FS and parameter setting in SVM. The Gaussian mutation strategy is used to enhance population diversity. The conversion parameter strategy based on the logistic model is used to achieve a fine balance between exploration and exploitation. The refraction-learning strategy helps the algorithm escape the local optimum. Thus, different strategies are designed at different evolution phases. To verify the impact of control parameters and introduced strategies, some experiments are done on 23 classical benchmark functions. In addition, the proposed method is compared with 6 state-of-the-art methods such as PSO, GOA, SSA, HHO, TLBO, and HG-GA based on 20 datasets where 4 datasets are high-dimensional. The comparisons and extensive results reveal that IBMO-SVM outperforms other wrapper methods using different evaluation metrics. According to accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity, the proposed IBMO-SVM achieves superiority over the competitor classifiers.

Different directions for future work are suggested. Other real-world datasets can be further tested, such as the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dataset. IBMO can also be explored in other optimization domains. Internet of Things, computer vision, and cloud computing are all the focus.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Sanming University introduces high-level talents to start scientific research funding support project (20YG14), Guiding science and technology projects in Sanming City (2020-G-61), Educational research projects of young and middle-aged teachers in Fujian Province (JAT200618), Scientific research and development fund of Sanming University (B202009).

Biographies

Heming Jia

received the Ph.D. degree in system engineering from Harbin Engineering University, China, in 2012. He is currently a professor in Sanming University. His research interests include nonlinear control theory and application, swarm optimization algorithm, image segmentation, and feature selection.

Kangjian Sun

was born in Jinzhou, China, in 1996. He received the B. E. degree from Northeast Forestry University, China, in 2019. He is currently pursuing the M. E. degree in control engineering from Northeast Forestry University. His research interests include swarm intelligence optimization, image segmentation, and feature selection.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Han JKM, Pei J (2012) Data Preprocessing. In: Han J. Kamber M, Pei J (eds) Data Mining: Concepts and Techniques, 3rd edn. Morgan Kaufmann, California, pp 83–124

- 2.Mafarja MM, Mirjalili S. Hybrid whale optimization algorithm with simulated annealing for feature selection. Neurocomputing. 2017;260:302–312. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2017.04.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mafarja M, Aljarah I, Faris H, Hammouri AI, Al-Zoubi AM, Mirjalili S. Binary grasshopper optimization algorithm approaches for feature selection problems. Expert Syst Appl. 2019;117:267–286. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2018.09.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gu S, Cheng R, Jin Y. Feature selection for high-dimensional classification using a competitive swarm optimizer. Soft Comput. 2018;22:811–822. doi: 10.1007/s00500-016-2385-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rejer I. Genetic algorithm with aggressive mutation for feature selection in BCI feature space. Pattern Anal Applic. 2015;18:485–492. doi: 10.1007/s10044-014-0425-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang X, Mei C, Chen D, Li J. Feature selection in mixed data: A method using a novel fuzzy rough set-based information entropy. Pattern Recognit. 2016;56:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.patcog.2016.02.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu H, Yu L. Toward integrating feature selection algorithms for classification and clustering. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2005;17(4):491–502. doi: 10.1109/TKDE.2005.66. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen K, Zhou F, Yuan X. Hybrid particle swarm optimization with spiral-shaped mechanism for feature selection. Expert Syst Appl. 2019;128:140–156. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2019.03.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Unler A, Murat A, Chinnam RB. mr2PSO: a maximum relevance minimum redundancy feature selection method based on swarm intelligence for support vector machine classification. Inf Sci. 2011;181(20):4625–4641. doi: 10.1016/j.ins.2010.05.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gheyas IA, Smith LS. Feature subset selection in large dimensionality domains. Pattern Recognit. 2010;43(1):5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.patcog.2009.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]