Abstract

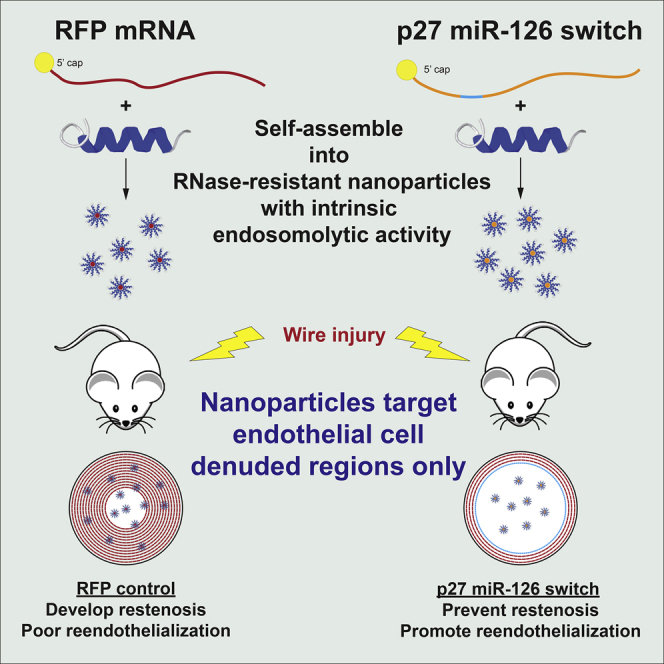

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death and disability worldwide. Effective delivery of cell-selective therapies that target atherosclerotic plaques and neointimal growth while sparing the endothelium remains the Achilles heel of percutaneous interventions. The current study utilizes synthetic microRNA switch therapy that self-assembles to form a compacted, nuclease-resistant nanoparticle <200 nM in size when mixed with cationic amphipathic cell-penetrating peptide (p5RHH). These nanoparticles possess intrinsic endosomolytic activity that requires endosomal acidification. When administered in a femoral artery wire injury mouse model in vivo, the mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles deliver their payload specifically to the regions of endothelial denudation and not to the lungs, liver, kidney, or spleen. Moreover, repeated administration of nanoparticles containing a microRNA switch, consisting of synthetically modified mRNA encoding for the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 that contains one complementary target sequence of the endothelial cell-specific miR-126 at its 5′ UTR, drastically reduced neointima formation after wire injury and allowed for vessel reendothelialization. This cell-selective nanotherapy is a valuable tool that has the potential to advance the fight against neointimal hyperplasia and atherosclerosis.

Keywords: mRNA therapeutics, endosomal escape, nanotherapy, restenosis, atherosclerosis, cardiovascular disease, cell-selective therapy

Graphical abstract

Hana Totary-Jain and colleagues report a highly efficient, peptide-based mRNA delivery platform that specifically targets regions of endothelial damage in blood vessels. These self-assembled nanoparticles delivered a cell-selective therapeutic mRNA that simultaneously prevented restenosis and allowed for vessel healing when administered systemically after arterial injury.

Introduction

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease remains one of the greatest burdens on healthcare worldwide. Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for >13% of all deaths in the United States in 2017.1,2 In patients with acute coronary syndromes, surgical revascularization by coronary artery bypass grafting or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has greatly reduced mortality rates. Over the last several decades PCI has advanced from simple balloon catheters to deployable metal stents and on through multiple generations of drug-eluting stents (DESs). The development of DESs, which provide a sustained local release of antiproliferative agents designed to inhibit restenosis caused by the hyperproliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), has dramatically reduced the need for additional revascularization compared to bare metal stents.3,4 However, the indiscriminate drugs coated on DESs also inhibit the regrowth of endothelium that was damaged during the angioplasty along with the VSMCs. The delayed healing of the endothelium permits the adhesion of platelets and lipid accumulation in the vessel walls, leading to an increased risk of in-stent thrombosis and neoatherosclerosis in the years following implantation, which require patients to undergo prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy.3,4 Antirestenotic therapies that inhibit neointimal growth while sparing the damaged endothelium to promote vessel healing are still unavailable.

We have previously performed a proof-of-principle study in which we uniquely leveraged the endothelial cell-specific microRNA (miRNA) miR-126 to design an adenoviral vector containing target sequences complementary to the mature miR-126-3p strand at the 3′ end of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 (Ad-p27-126TS) to enable overexpression of exogenous p27 selectively in VSMCs and infiltrating immune cells but not in endothelial cells.3,5 This adenoviral vector achieved striking results in a rat carotid artery balloon injury model, inhibiting neointimal hyperplasia and inflammation while simultaneously promoting vessel reendothelialization, reducing hypercoagulability, and restoring the endothelium-dependent vasodilatory response to levels indistinguishable from uninjured controls.5 However, to avoid the serious safety concerns associated with recombinant virus-based therapy, we sought to develop a nonviral alternative using a miRNA switch that utilizes synthetically modified mRNA containing one miR-126 target site at its 5′ UTR.6 As a delivery platform we used a cationic amphipathic cell-penetrating peptide (p5RHH) that has been proven to effectively deliver small interfering RNA (siRNA).7,8

RNA therapeutics are a promising new class of biological drugs that are under active development for a variety of human diseases.9,10 mRNA therapeutics in particular have a variety of potential applications, including protein replacement therapy,11 gene editing,12 and vaccines.13, 14, 15, 16 The use of synthetic mRNA offers advantages over traditional DNA or viral vectors as there is no limit for its length or risk of insertional mutagenesis and cellular division is not required for it to be translated. In addition, we and others have shown that synthetic mRNA can be posttranscriptionally regulated by miRNAs if miRNA complementary sequences are inserted into the 5′ or 3′ UTR.6,17 Designing these miRNA switches to confer cell selectivity or to generate gene circuits is a rapidly growing subject in the field of synthetic biology.18,19 These miRNA switches are a promising technology that would allow for specific inhibition of the VSMCs and inflammatory cells that drive restenosis while sparing the injured endothelium. However, no mRNA delivery platform currently available has been reported to target regions of endothelial cell damage.

Recently, a modified version of the membrane lytic protein melittin with reduced cytolytic activity, named p5RHH, has been shown to rapidly interact with siRNA to form 55 nm particles spontaneously upon mixing. These nanoparticles are taken up by macropinocytosis and traffic through endosomes, where the decreasing pH drives nanoparticle disassembly and releases the payload siRNA.20 The highly concentrated p5RHH within the endosomes induces endosomal lysis and escape of the siRNA into the cytoplasm. Importantly, the concentration of the free p5RHH released in the cytoplasm is insufficient to disturb the plasma membrane, which maintains cell viability.20 These p5RHH-siRNA nanoparticles were recently shown to be effective in reducing JNK2 expression in the plaques of an atherosclerotic mouse model after systemic administration.21

Here, we demonstrate that the p5RHH peptide spontaneously forms highly transfective, nontoxic nanoparticles in the presence of synthetic mRNA. Systemic administration of near-infrared fluorescent protein (niRFP)-encoding mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles in a femoral artery wire injury mouse model produced robust niRFP expression in regions of endothelial denudation, whereas niRFP was not detected in regions of intact endothelium or other organs. Moreover, repeated systemic administration of p5RHH nanoparticles containing cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 miRNA switch that contains one complementary target sequence of the endothelial cell-specific miR-126 at its 5′ UTR significantly reduced restenosis and allowed reendothelialization without inducing toxicity.

Results

Constant p5RHH-to-mRNA ratio yields highest transfection efficiency

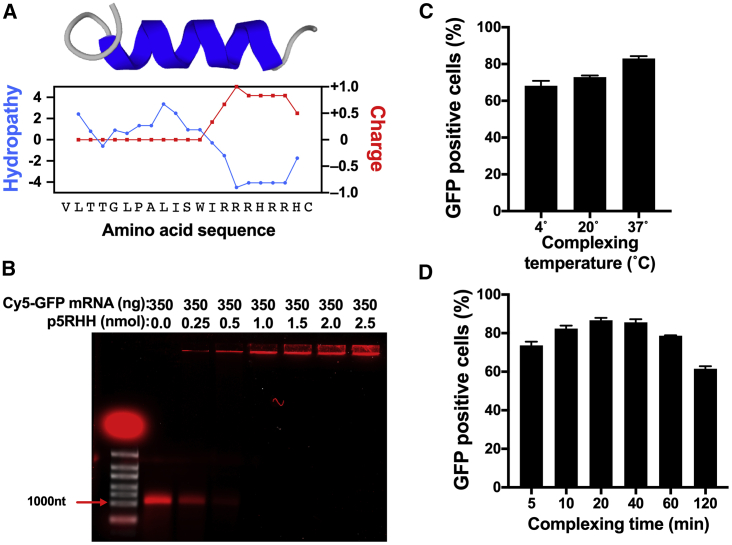

The p5RHH peptide is composed of 21 amino acids, with a hydrophobic segment and a cationic C terminus that contains 5 arginine and 2 histidine residues (Figure 1A). The cationic C terminus of p5RHH enables the peptide to interact electrostatically with the negatively charged backbone of nucleic acids. To examine the interaction of p5RHH with mRNA, a gel retardation assay was performed using 350 ng in-vitro-transcribed Cy5-uridine-labeled green fluorescent protein (GFP)-coding mRNA (to allow for visualization) incubated with increasing amounts (0–2.5 nmol) of p5RHH. Given the positive charge of p5RHH, we anticipated that only free unbound mRNA would migrate when an electric field was applied. As expected, a single band of ∼1,100 nt migrated in the agarose gel when free Cy5-uridine-labeled GFP mRNA was loaded. Incubation of Cy5-labeled GFP mRNA with increasing amounts of p5RHH decreased the free mRNA signal and shifted the Cy5 signal to the loading well, indicating that the Cy5-labeled GFP mRNA was bound to the p5RHH peptide and formed a complex that did not migrate through the agarose gel when the electrical field was applied (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

p5RHH spontaneously binds to synthetic mRNA

(A) Amino acid sequence and predicted structure with hydrophobicity and charge density plots for p5RHH. (B) mRNA loading assay of 350 ng of 5% Cy5-uridine labeled GFP mRNA with 5′ cap and polyA tail (~1,100 nt) complexed with the indicated amounts of p5RHH. Cy5 signal is shown in red; ethidium bromide staining is shown in white. (C and D) Flow cytometry of B16F10 cells 24 h after transfection with GFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles complexed for 40 min at the indicated temperature (C) or the indicated time at 37°C (D). Data represent the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments.

To determine the optimal conditions for the highest transfection efficiency, 350 ng of GFP mRNA was mixed with 2 nmol of p5RHH and incubated at 4°, 20°, or 37°C for 40 min or incubated at 37°C for 5, 10, 20, 40, 60, or 120 min before being added to B16F10 cells. After 24 h, the percentage of GFP-positive cells was determined by flow cytometry. An incubation temperature of 37°C and incubation times of 20 and 40 min displayed the highest transfection efficiencies (Figures 1C and 1D). Therefore, these conditions were used in all subsequent experiments.

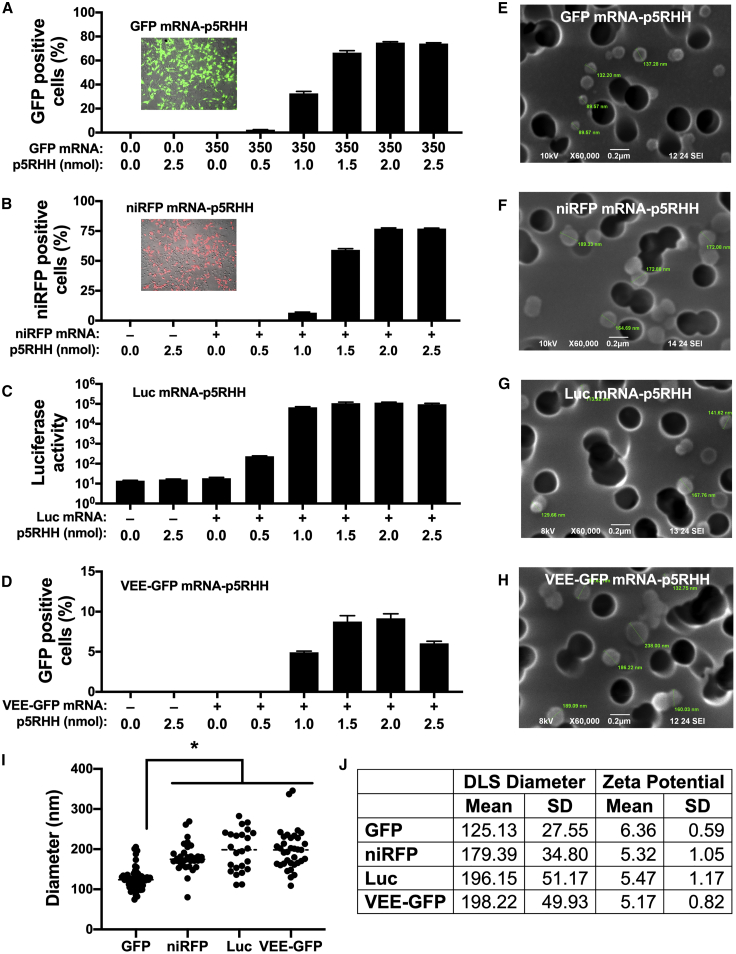

To determine the optimal mRNA-to-p5RHH ratios that result in the highest transfection efficiency, in vitro-transcribed GFP mRNA (350 ng) was incubated with increasing amounts (0–2.5 nmol) of p5RHH and added to B16F10 cells. After 24 h, GFP-positive cells were determined by flow cytometry. Cells transfected with GFP mRNA complexed with increasing amounts of p5RHH resulted in an increased percentage of GFP-positive cells that reached a maximum of 75% at 2 nmol of p5RHH (Figure 2A). We also tested whether the optimal mRNA-to-p5RHH ratios are affected by mRNA length. Therefore, 350 ng of mRNA encoding near-infrared fluorescent protein 670 (niRFP, 936 nt), firefly luciferase (Luc, 1,653 nt), or self-replicating mRNA derived from the Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus expressing GFP (VEE-GFP, 8,600 nt) was incubated with increasing amounts (0–2.5 nmol) of p5RHH. After 24 h, transfection efficiency of niRFP mRNA-p5RHH and VEE-GFP mRNA-p5RHH as well as luciferase activity from Luc mRNA-p5RHH all peaked at the same ratio of 350 ng of mRNA to 2.0 nmol of p5RHH, similar to the 714 nt GFP mRNA-p5RHH (Figures 2A–2D). However, the transfection efficiency of VEE-GFP mRNA-p5RHH was lower than the other nanoparticles (Figure 2D). Therefore, in all subsequent experiments we used a ratio of 350 ng of synthetic mRNA to 2 nmol of p5RHH.

Figure 2.

p5RHH forms nanoparticles with mRNA payloads of various lengths

(A–D) Flow cytometry (A, B, and D) and luciferase assay (C) of B16F10 cells 24 h after treatment with the indicated amount of p5RHH complexed with 350 ng of GFP (A), niRFP (B), Luc (C), or VEE-GFP (D) mRNA. (E–I) Representative scanning electron microscopy images (E–H) accompanied by dot plot of sizes (I) of p5RHH nanoparticles loaded with the indicated mRNA on a polycarbonate membrane with 200 nm pores (dark circles). (J) Nanoparticle size and zeta potential determined by dynamic light scattering. Data represent the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments (A–D). ∗p < 0.05 versus VEE-GFP nanoparticles (I).

mRNA and p5RHH spontaneously form consistent nanoparticle size regardless of mRNA length

To visualize and measure the diameter of each of the different mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles, scanning electron microscopy imaging was performed at the optimized ratio of mRNA to p5RHH (350 ng mRNA:2.0 nmol p5RHH). Strikingly, compact spherical nanoparticles with an average diameter of ≤200 nm were observed for each of the tested mRNAs (Figures 2E–2I). Interestingly, the niRFP, Luc, and VEE-GFP mRNA nanoparticles were of very similar sizes, while the GFP mRNA nanoparticles were significantly smaller (∼125 nm) (Figure 2I). Despite the difference in sizes, the zeta potential measurements of the different mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles showed an effective surface charge of approximately +6 mV for each nanoparticle (Figure 2J). These results demonstrate that the physical characteristics of mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles are consistent even when they are formed with mRNA payloads of varying lengths.

Endosomal acidification is required for effective mRNA endosomal escape after delivery by mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles

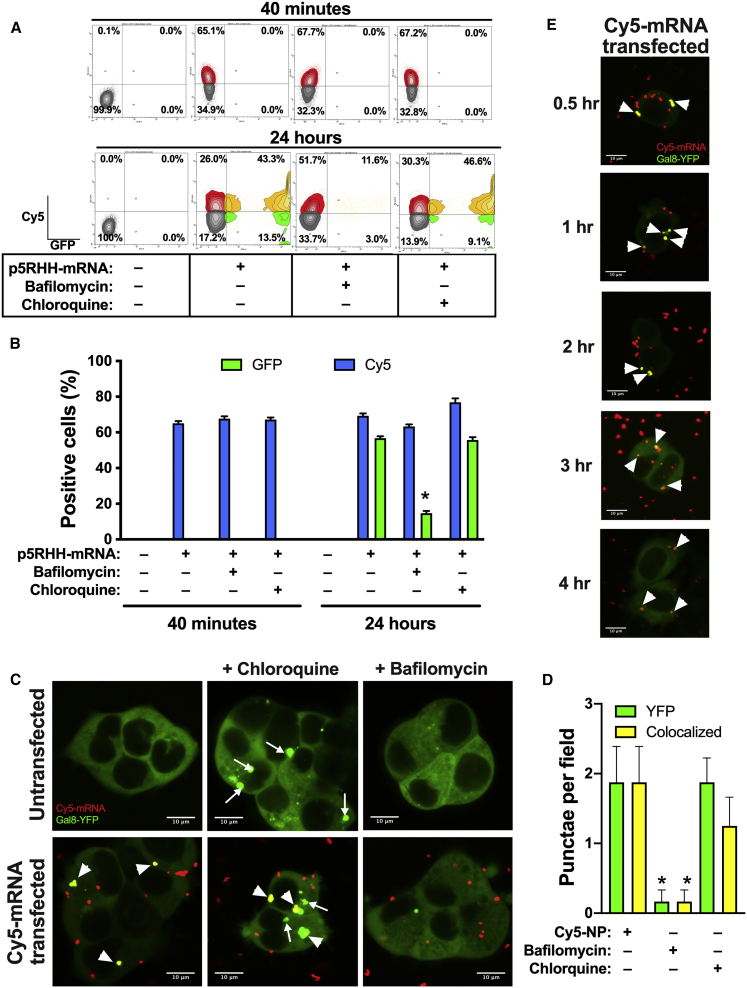

To test whether mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles require endosomal acidification to deliver their payload to the cytoplasm, B16F10 cells were transfected with 5% Cy5-labeled GFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles. Cells were treated with 1 μM bafilomycin, an inhibitor of endosomal acidification, or vehicle control. Particle uptake, measured by percent Cy5-positive cells, and percent GFP-positive cells were determined by flow cytometry at 40 min and 24 h after transfection. While no GFP-positive cells were detected after 40 min of transfection, ∼65% of the cells were Cy5-positive in both bafilomycin-treated and -untreated cells, indicating that bafilomycin does not affect cellular uptake of the nanoparticles (Figures 3A and 3B). After 24 h, 56.7% of the untreated cells were GFP-positive, whereas bafilomycin-treated cells exhibited only 14.6% (p < 0.05), even though the percentage of Cy5-positive cells was still at ∼65% in both groups (Figure 3A and 3B). These data indicate that mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles are rapidly taken up by cells, traffic through the endosomes, and require endosomal acidification to release the mRNA payload into the cytosol to be translated.

Figure 3.

Effective endosomal escape of p5RHH-mRNA nanoparticles

(A and B) Flow cytometry quantification of B16F10 cells at the indicated time point after treatment with 5% Cy5-uridine-labeled GFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles in the presence of 50 μM chloroquine or 1 μM bafilomycin. (C–E) Representative confocal images of untransfected Gal8-YFP HEK293T cells or cells transfected with 5% Cy5-uridine labeled GFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles. Images were captured 60 min after the addition of nanoparticles and/or treated with 50 μM chloroquine or 1 μM bafilomycin for colocalization analysis (C and D) or at the indicated time point after transfection with 5% Cy5-uridine-labeled GFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles (E). Data represent the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments (B) or at least 6 different image fields (D). ∗p < 0.05 versus nanoparticle + vehicle-treated cells (B) or nanoparticle (Cy5-NP)-treated cells (D). Original magnification 120×; scale bars represent 10 μm (C and D). Narrow arrows indicate disrupted endosomes; broad arrowheads indicate colocalization of disrupted endosomes and Cy5-mRNA (C and D).

Next, we tested whether addition of chloroquine, a known endosomolytic agent, enhanced the transfection efficiency by inducing endosomal release of the mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles that may be still trapped in the endosomes. Again, B16F10 cells were transfected with 5% Cy5-uridine-labeled GFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles and treated with vehicle or with 50 μM chloroquine. After 40 min of transfection, cells treated with chloroquine showed no significant difference in the percentage of Cy5-positive cells compared to vehicle-treated cells (67.2% versus 65.1%) and no GFP-positive cells were detected, indicating that chloroquine does not affect cellular uptake of the nanoparticles (Figures 3A and 3B). Importantly, after 24 h, despite the small increase (76.9% versus 69.3%) in Cy5-positive cells, no change in the percentage of GFP-positive cells (56.8% versus 55.7%) was found between chloroquine-treated and -untreated cells (Figures 3A and 3B), indicating complete endosomal escape for GFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles due to their intrinsic endosomolytic activity.

To further confirm the endosomolytic activity of the mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles, we utilized HEK293T cells stably transfected with Galectin-8 (Gal8) fused to yellow fluorescent protein (YFP).22 In these cells, the Gal8-YFP is dispersed throughout the cytosol. However, upon endosomal disruption, such as chloroquine treatment, the Gal8-YFP selectively binds to the exposed glycosylated moieties located on the surface of the inner endosomal membrane, resulting in the concentration of Gal8-YFP in the form of fluorescent punctae (Figure 3C, green dots, narrow arrows). In contrast, treatment with bafilomycin, which inhibits endosomal acidification and does not induce endosomolysis, the Gal8-YFP remains dispersed in the cytosol (Figure 3C). Importantly, Gal8-HEK293T cells transfected with Cy5-labeled niRFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles (Figure 3C, red dots) showed colocalization of the Gal8-YFP and the Cy5-labeled mRNA (Figure 3C, yellow dots, broad arrowheads), even in the absence of chloroquine. These images further confirm the intrinsic endosomal disruption by the mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles (Figures 3C and 3D). Similar colocalization was observed when nanoparticle-transfected cells were also treated with chloroquine, but we also observed formation of YFP-only punctae due to chloroquine-induced disruption of endosomes that did not contain mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles (Figures 3C and 3D). In contrast, cells transfected with the nanoparticle and treated with bafilomycin showed significant reduction in the formation of the Gal8-YFP due to inhibition of the endosomal acidification required for p5RHH’s endosomolytic activity (Figures 3C and 3D). Continued monitoring of the GAL8-YFP HEK293T cells after nanoparticle addition revealed that endosomal escape mediated by p5RHH occurred within 30 min of nanoparticle addition and continued throughout the entire 4-h observational period (Figure 3E).

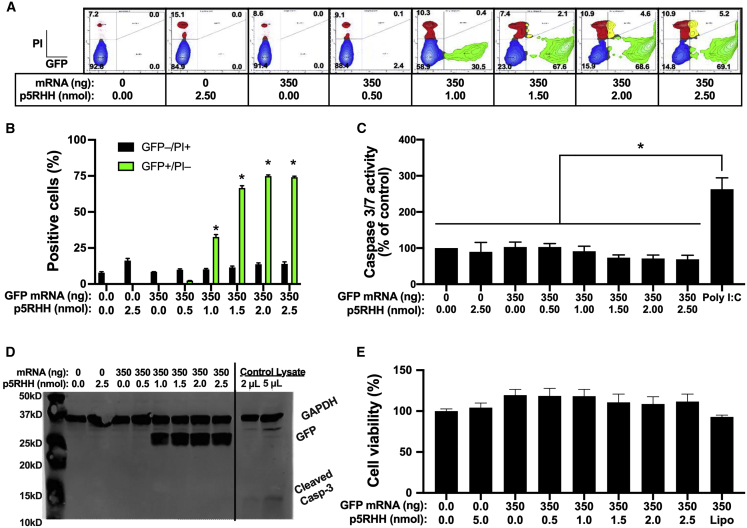

mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles do not induce cytotoxicity

To ensure that the endosomolytic activity of the mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles does not induce apoptosis of the transfected cells, we measured the percentage of propidium iodide (PI)-positive B16F10 cells after transfection with GFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles at various mRNA-to-peptide ratios. After 24 h we observed no significant increase in PI-positive cells at any of the tested ratios (Figures 4A and 4B), indicating that the unbound p5RHH released after endosomolysis does not induce apoptosis. These results were also confirmed via fluorometric assay for caspase 3/7 activity (Figure 4C) and immunoblotting for cleaved caspase 3 (Figure 4D). Furthermore, measurement of cell viability/proliferation with WST-1 showed no detrimental effects of mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticle treatment on B16F10 cells (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles exhibit minimal cytotoxicity

(A–E) B16F10 cells were transfected with GFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles formulated at the indicated ratios. After 24 h cytotoxicity was measured by flow cytometry with propidium iodide (A and B), fluorometric caspase 3/7 activity assay (cells were transfected with 10 nM polyI:C as positive control) (C), immunoblotting for GFP and cleaved caspase 3 (cleaved caspase 3-positive control lysates were run on the same gel as B16F10 lysates) (D), and WST-1 cell viability assay was performed (E). Data represent the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05 versus untransfected control (B, C, and E).

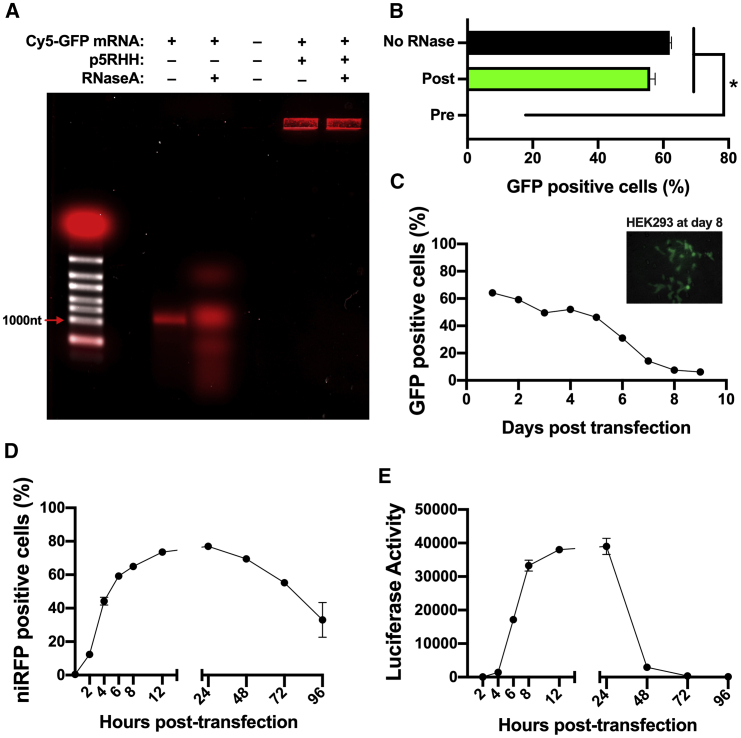

mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles protect the mRNA from degradation by RNase

Successful in vivo delivery of mRNA therapeutics requires stable nanoparticles that can protect the synthetic mRNA from degradation. To test whether mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles protect their payload from degradation, we treated Cy5-labeled GFP mRNA-p5RHH or free Cy5-labeled GFP mRNA with RNase A or with vehicle control for 20 min at 37°C before analyzing the resulting products by gel electrophoresis. Free mRNA exhibited extensive degradation by RNase A, whereas the mRNA complexed with p5RHH showed no mRNA degradation (Figure 5A). B16F10 cells transfected with GFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles treated with RNase A showed a percentage of GFP-positive cells similar to the untreated nanoparticles after 24 h (Figure 5B). However, pretreatment of the GFP mRNA with RNase A before formation of the nanoparticles abolished GFP expression (Figure 5B). These results indicate that mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles may withstand serum endonucleases, which is critical for in vivo delivery of mRNA therapeutics.

Figure 5.

mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles prevent degradation by RNase

(A) Gel electrophoresis of unbound and p5RHH-complexed Cy5-labeled GFP mRNA with or without treatment with 0.25 μg of RNase A after nanoparticle formation. (B) Flow cytometry of B16F10 cells 24 h after transfection with GFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles untreated or treated with RNase A before or after nanoparticle formation. (C–E) Flow cytometry (C and D) and luciferase assay (E) of B16F10 cells at the indicated time point after treatment with GFP (C), niRFP (D), or luciferase (E) mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles. Data represent the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05 versus no RNase treatment (B).

mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles produce prolonged protein expression

Another important consideration for the use of mRNA therapeutics is the duration of protein expression. Therefore, we tested GFP expression over time in B16F10 cells transfected with GFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles and found that ∼65% of cells were GFP-positive by flow cytometry 24 h after transfection. The percentage of GFP-positive cells gradually decreased, but 6% of cells remained GFP-positive even 9 days after transfection (Figure 5C). Similarly, Ad-HEK293 cells transfected with GFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles also exhibited GFP-positive cells 8 days after transfection (Figure 5C, inset). We also tested the protein expression at shorter time points in B16F10 cells transfected with niRFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles. We observed a rapid increase in the first 24 h, peaking at 24 h with 77% niRFP-positive cells, and could still detect niRFP in 33% of cells after 4 days (Figure 5D). However, when B16F10 cells were transfected with Luc mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles, luciferase activity peaked between 12 and 24 h and rapidly decreased thereafter (Figure 5E). Therefore, while mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles rapidly induce protein expression, the durability of the expression is largely determined by the stability of the expressed protein itself.

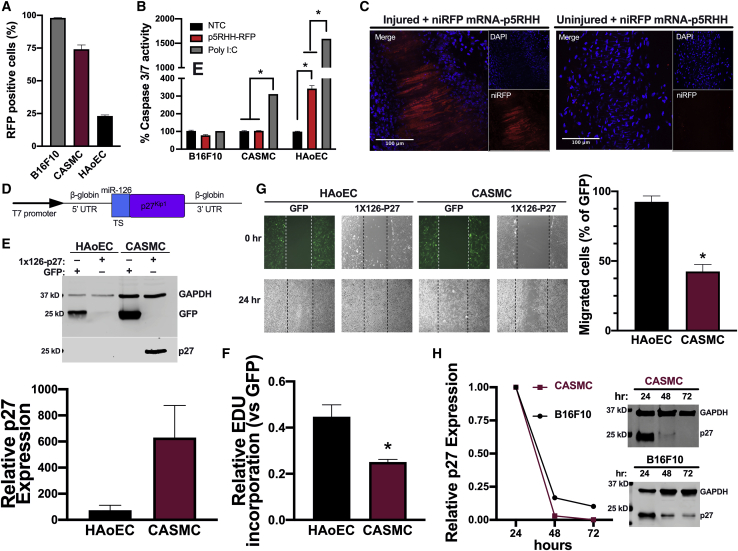

mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles exclusively target regions with disrupted endothelium

Because our goal is to use these mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles to prevent restenosis in vivo, we first verified the transfection efficacy of the mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticle in primary human coronary artery smooth muscle cells (CASMCs) and aortic endothelial cells (HAoECs). Using the same niRFP mRNA-to-p5RHH ratio, optimized in B16F10 cells, resulted in 74% and 23% transfection efficiency in CASMCs and HAoECs respectively but in B16F10 cells showed 98% RFP-positive cells (Figure 6A). However, when the activation of caspase 3/7 was examined, CASMCs showed no increase in caspase 3/7 activity, similar to B16F10, whereas HAoECs exhibited a 3-fold increase compared to untransfected controls (Figure 6B). To test the efficacy of mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles in vivo, we used a femoral artery wire injury mouse model that is widely used to study postangioplasty restenosis. The left femoral artery of C57BL6/J mice was subjected to wire injury and received one intravenous injection of niRFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles immediately after the surgeries. After 6, 12, 24, and 48 h, whole mount confocal images of the left injured and the collateral uninjured femoral arteries were performed. The expression of niRFP was clearly observed only after 48 h in the wire-injured artery but not in the contralateral uninjured artery of the same niRFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticle-treated mice (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

p27-miRNA switch-p5RHH nanoparticles allow for selective inhibition of CASMC growth and migration

(A and B) B16F10 cells, CASMCs, and HAoECs were transfected with niRFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles, and transfection efficiency (A) and caspase 3/7 activation (B) were measured after 24 h. (C) Representative confocal images from whole mounts of wire-injured and contralateral control femoral arteries collected 48 h after a single injection of niRFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles (n = 3). Scale bars represent 100 μm. (D) Schematic of the 1x126-p27-miRNA switch construct indicating the miR-126 target site (TS). (E–G) HAoECs and CASMCs were transfected with GFP mRNA or p27-miRNA switch using Lipofectamine 2000. After 24 h GFP and p27 protein expression was assayed by immunoblotting of cell lysates (E), cell proliferation by EdU incorporation assay (F), and cell migration by scratch wound assay (G) 24 h after transfection (E and F) or 24 h after the scratch wound (G). (H) Representative immunoblots and quantification of GFP expression normalized to GAPDH in CASMCs and B16F10 cells transfected with 1x126-p27-miRNA switch-p5RHH nanoparticles for the indicated time. Data represent mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05 for the indicated comparisons (B) or versus HAoECs (F and G).

We also assessed the systemic distribution of the niRFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles at both the RNA and protein levels in the kidney, liver, lung, and spleen at 6, 12, 24, and 48 h after injection. niRFP mRNA could be detected by RT-PCR in the spleen up to 24 h, whereas the liver and the lungs showed weak signal at 6 and 12 h after nanoparticle injection. By 48 h, the niRFP mRNA was no longer detectable in either organ (Figure S1). Despite the detection of the niRFP mRNA in the spleen, we were unable to visualize niRFP protein expression by confocal imaging in any of the organs at any time point (Figure S2). To further confirm the lack of protein expression in the different organs, we injected C57BL6/J mice intravenously with GFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles and assessed GFP expression after 48 h. Immunoblotting of brain, heart, lung, muscle, pancreas, liver, spleen, kidney, and bladder lysates exhibited no GFP expression in any of these organs (Figure S3). We also performed two intravenous injections of a C57BL6/J mouse with Luc mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles over two consecutive days and found no detectable luciferase activity in the lungs, liver, kidney, or spleen (Figure S4). Taken together, these results highlight the ability of mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles to deliver mRNA therapeutics specifically to endothelial cell denuded regions and avoid off-target expression in typical depot organs.

p27-miRNA switch selectively inhibits smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration while protecting endothelial cells

To selectively inhibit restenosis while protecting the endothelium, we constructed a p27-miRNA switch by adding one copy of the 22-nt sequence fully complementary to the mature miRNA-126-3p at the 5′ UTR of mouse p27 mRNA (Figure 6D). This design of the p27-miRNA switch will selectively inhibit exogenous p27 overexpression in endothelial cells that endogenously express high levels of miR-126-3p but not in CASMCs that do not express miR-126-3p (Figure S5). To confirm the ability of the p27-miRNA switch to selectively overexpress exogenous p27 and inhibit growth of cells lacking endogenous miR-126-3p, we transfected CASMCs and HAoECs with the p27-miRNA switch. We used Lipofectamine 2000 to deliver the p27-miRNA switch in these experiments to ensure that the lower transfection rate of HAoECs with mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles would not confound our analysis of the p27-miRNA switch activity. Immunoblotting for p27 showed ∼600-fold increase in expression in CASMCs compared to HAoECs (Figure 6E). The cell-selective overexpression of p27 in CASMCs led to a significant decrease in both proliferation (Figure 6F; Figure S6) and migration (Figure 6G) compared to HAoECs.

To determine the duration of p27 protein expression we transfected CASMCs and B16F10 cells with the p27-miRNA switch-p5RHH nanoparticles and found that, although levels of p27 decreased dramatically, it was still detected 48 h after transfection in both cell types and was undetectable by 72 h in CASMCs (Figure 6H).

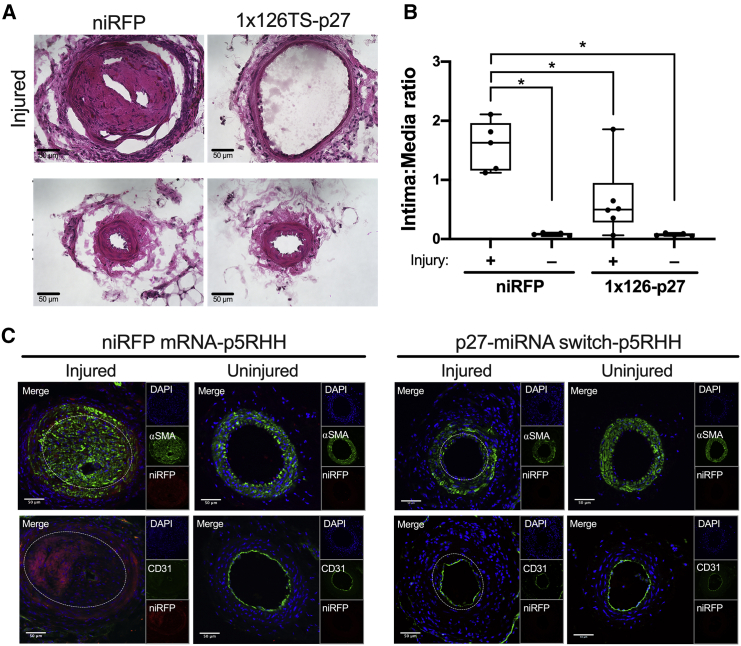

p27-miRNA switch-p5RHH nanoparticle inhibits neointimal formation and enables vessel healing

Based on the promising results we observed from the p27-miRNA switch-p5RHH nanoparticle that precisely delivers the synthetic miRNA switch to CASMCs and to the endothelial cell denuded regions, we sought to test its therapeutic potential in a wire injury mouse model. Therefore, beginning on the day after the wire injury of the left femoral artery, mice received retroorbital injections every 3 days for 2 weeks (total of 5 doses) of p5RHH complexed with the p27-miRNA switch or control niRFP mRNA, while the contralateral femoral artery was used as an uninjured control. After 2 weeks, injured femoral arteries of mice treated with niRFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles developed large alpha smooth muscle actin (αSMA)-positive and niRFP-positive neointima with significant increase in the intima-to-media (I/M) area ratio compared to the contralateral uninjured femoral arteries (Figures 7A–7C). Strikingly, in the animals treated with p27-miRNA switch-p5RHH nanoparticles, there was a significant reduction in the I/M area ratio and complete CD31-positive endothelial cell coverage compared to the injured vessels treated with niRFP mRNA-p5RHH (Figures 7A–7C). These results indicate that p27-miRNA switch-p5RHH nanoparticles can selectively inhibit neointimal hyperplasia without impairing regrowth of the injured endothelium.

Figure 7.

p27-miRNA switch-p5RHH nanoparticles selectively inhibit restenosis and allow vessel healing

(A–C) Representative H&E-stained sections (A), intima-to-media area ratios (B), and representative immunofluorescence confocal images showing endothelial cell coverage (CD31) and α smooth muscle cell actin (αSMA) (C) of uninjured control and wire-injured femoral arteries of mice treated with niRFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles (n = 5) or p27-miRNA switch-p5RHH nanoparticles (n = 6) every 72 h for 2 weeks after injury. Data represent mean ± SEM. Images were captured at 40× magnification, and scale bars represent 50 μm. White dashed lines in injured vessels indicate media-intima border (C). ∗p < 0.01 versus uninjured arteries (B).

To ensure the safety of our nanoparticles after repeated dosing, we assayed liver and kidney function and observed no adverse alterations in serum chemistry from either the p27-miRNA switch-p5RHH or the niRFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles compared to naive controls (Table S1). We also performed RT-PCR and fluorescence microscopy imaging to test whether niRFP transcripts and protein were present in the liver, lungs, kidneys, and spleens of the mice treated with niRFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles every 3 days for 2 weeks after wire injury but did not observe any niRFP mRNA or protein expression (Figures S7 and S8). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the p5RHH nanoparticle can effectively deliver therapeutic p27-miRNA switch to inhibit restenosis and accelerate vessel healing without inducing off-target expression or toxicity.

Discussion

Synthetic mRNA therapeutics hold great promise for the treatment of a myriad of diseases. Despite substantial advances in the production of the synthetic mRNA, the limitations of existing delivery platforms severely hinder its clinical development. The present study demonstrates that p5RHH peptides in the presence of mRNA spontaneously form compact nanoparticles across a range of mRNA sizes. These nanoparticles are highly RNase resistant and readily taken up by the cells, and they efficiently and safely release the mRNA from the endosomes to be translated. Systemic delivery of a therapeutic p27-miRNA switch effectively reduced neointima formation in a wire injury mouse model and allowed vessel reendothelialization.

The membrane lytic protein melittin has been reported to promote endosomal escape and efficient release of DNA into the cytoplasm after covalent attachment to polyethylenimine.23 Attempts to limit the inherent activity of melittin to endosomes by adding pH-sensitive protecting groups to mask melittin’s pore forming activity at neutral pH, which then could be removed upon endosomal acidification, displayed promising results.24 However, this strategy ultimately proved to produce unacceptable levels of toxicity, prompting the termination of the clinical trial for hepatitis B treatment that used coadministration of the pH-sensitive melittin and an antiviral siRNA (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02452528).

In contrast, p5RHH is an N-terminal truncation of melittin that retains a 13 aa hydrophobic core combined with a modified cationic C terminus composed of five arginine and two histidine residues. Unlike melittin, the p5RHH peptide is capable of spontaneously forming nanoparticles with negatively charged siRNA through a combination of electrostatic interactions and strong hydrogen bonding that can be disrupted by pH-dependent protonation of imidazole groups of the histidine residues.25 The resulting nanoparticles remain stable in circulation as a polyplex and exhibit minimal toxicity, as the p5RHH is not freed until the nanoparticle is disassembled in the low-pH environment of the endosome.7 In analogous fashion, the p5RHH rapidly interacts with mRNA molecules of different sizes to self-assemble nanoparticles with high transfection efficiency and minimal cytotoxicity. Despite the 50-fold difference in GFP mRNA to siRNA length or even 400-fold difference in the case of the VEE-GFP mRNA, the optimal charge ratio of p5RHH and synthetic mRNA (+10:−1) was similar to that previously reported for p5RHH and siRNA (+12:−1),7 because the mass-to-charge ratio of nucleic acids is essentially constant. Therefore, the optimal charge ratio of 350 ng of synthetic mRNA to 2 nmol of p5RHH could be scaled up or down to deliver a wide range of RNAs. It should be noted, however, that the use of constant charge ratio dictates that as the length of the payload RNA increases there must be a proportional decrease in the number of RNAs per nanoparticle or decrease in the number of nanoparticles formed. These differences could account for the reduced transfection efficiency we observed when using the self-replicating VEE-GFP mRNA. In addition, our VEE-GFP mRNA was in vitro transcribed with unmodified nucleotides because the commonly used modifications reduce the efficacy of the reverse transcription, a step necessary for the self-replication of the mRNA and the transcription of the GFP mRNA from the subgenomic promoter.

Measurement of the mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticle size and surface charge revealed compact spherical structures that were ≤200 nm in diameter with a +6 mV zeta potential for all of the tested mRNAs. Because the cell membrane is a negatively charged surface, the nanoparticles’ positive surface charge may increase cellular uptake by endocytosis.26 In addition, the small magnitude of the surface charge may minimize opsonization by serum proteins and clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system, thereby avoiding sequestration in the liver and spleen.

Trafficking of synthetic mRNAs from endosomes into the cytoplasm represents a major rate-limiting step for many delivery approaches, with typical endosomal escape efficiencies of ∼1–2%.27 The present study demonstrates that the endosomal escape of mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles is highly efficient, since inducing endosomolysis with chloroquine did not potentiate transfection. We also show that the intrinsic endosomolytic activity of mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles requires endosomal acidification to release the mRNA into the cytosol, where it can be rapidly translated into protein. Indeed, we observed that mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles achieved endosomal escape within 30 min and produced detectable reporter expression in <2 h in vitro.

The present study also demonstrated that mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles exhibit minimal cytotoxicity, although a slight increase in caspase 3/7 activity was seen in HAoECs. The reduced membrane lytic activity of p5RHH compared to melittin is largely due to the N-terminal truncation28 and prevents it from disrupting membranes outside the high concentrations achieved in the endosomes.7,20 After endosomolysis, the concentration of the free p5RHH is diluted in the comparatively large volume of the cytosol, thereby preventing disruption of the plasma membrane. Another key requirement for an effective in vivo mRNA delivery platform is the ability to prevent degradation of the synthetic mRNA by extracellular endonucleases. The present study demonstrated that mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles provided protection from RNase A degradation. Moreover, the transfection efficiency of mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles was also unaffected by RNase A treatment, which is a promising stability attribute for in vivo applications.

Recent advances in the design of nonviral delivery systems for synthetic mRNA have been reported for selective targeting to specific organs.29,30 However, most of these reports highlight selectivity that is restricted among liver, lung, or spleen. This study and previous work with p5RHH-siRNA nanoparticles have demonstrated passive permeation and prolonged residence only in regions of disrupted endothelial cell barriers but minimal uptake in liver, lung, or spleen.20,21 The restriction of the mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles to damaged vasculature confers an additional level of safety for systemic administration, as tissues with intact endothelial barrier function will not accumulate particles. To that point, we did not observe niRFP expression in uninjured femoral arteries; nor did we detect any expression in the typical depot organs of mice after treatment with niRFP, GFP, or Luc mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles.

In contrast, the robust expression of niRFP in regions of endothelial denudation following treatment with niRFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles was a promising sign that these nanoparticles could be used to specifically target endothelial cell damaged regions.

Our previous success using localized infection of a p27 switch via adenoviral vectors5 served as an excellent proof of principle; however, a nonviral vector was needed to advance this therapy toward clinical use. When p27-miRNA switch-p5RHH nanoparticles were delivered just 5 times in the 2 weeks following wire injury, we saw a striking reduction in neointima formation. Importantly, the inclusion of a single complementary target sequence for the endothelial cell-specific miR-126-3p allowed for simultaneous regrowth of the denuded endothelium. The selectivity of the miRNA switch synergizes with the preferential uptake of mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles by vascular smooth muscle cells compared to endothelial cells to confer an exceptional degree of cell-selective activity that is highly desirable for clinical application, as the complications associated with the current drug-eluting stents are largely associated with delayed endothelial regrowth. Importantly, we did not observe any adverse reactions or outcomes in the mice treated with our nanoparticles.

The fact that mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles do not enter organs across a healthy endothelial cell barrier and specifically localize to regions of damaged endothelium makes it an ideal platform to deliver synthetic mRNA therapeutics for cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, the specificity of our nanoparticles for regions of damaged endothelium ensures that this effective therapy is delivered to the areas that still require treatment, while adjacent, intact regions are unaffected. These properties, together with the simplicity of mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticle formation, endow our mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles with significant advantages in both preclinical and clinical applications for cardiovascular disease.

Materials and methods

mRNA template construction and in vitro transcription

GFP constructs for the generation of in vitro transcription were designed as previously described6 using the pLL3.7 plasmid, a gift from Luk Parijs (Addgene, plasmid #11795). The 3′ UTR of human β-globin (132 bp) was amplified using HeLa genomic DNA as template with forward and reverse primer oligonucleotides #1 and #2 (Table S2). The β-globin 3′ UTR PCR product and the pLL3.7 plasmid were then EcoRI digested and ligated together to complete the construct. niRFP constructs were constructed in a similar manner by using forward and reverse primer oligonucleotides #3 and #4 to clone the β-globin 3′ UTR, followed by XbaI digestion and ligation of the PCR product into the piRFP-N plasmid, a gift from Vladislav Verkhusha (Addgene, plasmid #45457). Firefly Luc constructs were created by PCRing the luciferase coding sequence out of pGL2 Basic (Promega) with forward and reverse primer oligonucleotides #5 and #6. The Luc PCR product and the pLL3.7 plasmid with the β-globin 3′ UTR were digested with XbaI and NheI, removing GFP from the pLL3.7 plasmid. The Luc coding sequences was then ligated into the pLL3.7 to form the final construct. The β-globin 3′ UTR was added to the 3′ end of GFP in T7-VEE-GFP, a gift from Steven Dowdy (Addgene, plasmid #58977), after PCR with primers #7 and #8 by double digestion with XbaI and NotI. The coding sequence of mouse p27 was cloned from B16F10 cell cDNA with primers #9 and #10, double digested with XbaI and BamHI, and inserted into digested pLL3.7 plasmid.

For in vitro transcription, templates were generated by PCR using forward primers #11, #12, or #13 (containing a T7 promoter, 5′ UTR of human β-globin and the first ∼20 bases of GFP, niRFP, or Luc, respectively) and reverse primer #14 (starting at the end of the human β-globin 3′ UTR). VEE-GFP template was generated by linearizing the pT7-VEE-GFP-β-globin plasmid with MluI. Because of the size of the 5′ insert, templates for in vitro transcription of p27 miRNA switches were constructed by sequential PCR reactions. In the first reaction, primers #14 and #15 were used to add the miR-126-3p complementary target sequence and a portion of the β-globin 5′ UTR before the p27 coding sequence (CCDS8653.1). After size selection by gel electrophoresis, the first PCR products were extended in a second PCR using primers #14 and #16, which added the remainder of the β-globin 5′ UTR and the T7 promoter.

In vitro transcription of GFP, RFP, and Luc mRNA, in which uridine was replaced with pseudouridine (TriLink Biotechnologies, #N-1019) to reduce the innate immune response,31,32 was performed per the manufacturer’s protocol with the HiScribe T7 High Yield RNA synthesis kit (NEB) followed by ammonium acetate precipitation as previously described.6,33 Cy-5 labeled GFP mRNA was generated by in vitro transcription with 95% pseudouridine and 5% Cy-5 uridine (GE Lifesciences, # PA55026). VEE mRNA was in vitro transcribed without any modified nucleotides because they can interfere with the self-replicating mechanism. The p27 miRNA switch was in vitro transcribed with complete 100% replacement of uridine with N1-methylpseudouridine (TriLink Biotechnologies, #N-1081), as it has been demonstrated that this nucleotide modification enhances sensitivity and translation of miRNA switches.6,17 The RNA was then capped using the ScriptCap m7G Capping System (CellScript) and poly A tailed using the A-Plus Poly(A) Polymerase Tailing Kit (CellScript). The addition of >100 nt poly(A) tail was confirmed by gel electrophoresis. The mRNA was precipitated with 1× volume of 5 M ammonium acetate, resuspended in DNase/RNase-free water, quantified by spectrophotometry, and stored at −80°C until use.

Preparation of p5RHH

p5RHH peptides were synthesized by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ, USA), dissolved at 20 mM in DNase-, RNase-, and protease-free water, and stored at −80°C until use.

Formation and characterization of p5RHH-mRNA nanoparticles

The synthetic mRNA and p5RHH peptides were diluted to 70 ng/μL and 400 μM, respectively, in DNase/RNase-free water. The mRNA and p5RHH were then combined at a 1-to-1 volume ratio in 8 volumes of OptiMEM (Gibco) and mixed briefly. The solution was incubated at 37°C for 40 min prior to use. To visualize p5RHH and mRNA binding a gel shift assay was performed on Cy5-labeled GFP mRNA complexed with increasing amounts of p5RHH. The resulting products were visualized by gel electrophoresis on an RNase-free 1% agarose gel.

To determine the size of the mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles, a 30 μL volume of mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticle solution was pipetted onto a 200 nm polycarbonate track-etched membrane, air-dried, sputter coated with gold/palladium, and imaged with a JSM6490 Scanning Electron Microscope (JEOL).

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurement of mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticle size and zeta potential was performed with a NanoBrook 90Plus (Brookhaven Instruments).

Cell culture, transfection, and toxicity

B16F10 (ATCC #CRL-6475), AD-HEK293 (Stratagene, #240085), and Gal8-YFP HEK293T cells, a gift from Dr. Craig Duvall,22 were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS. Primary human CASMCs (Lonza, #CC-2583) were cultured in VascuLife SMC Media (Lifeline Cell Technology #LL-0014). Primary HAoECs were isolated as previously described33 from a viable heart provided by LifeLink Foundation after material transfer agreement (MTA) approval for the transfer of nontransplantable organs for research at the University of South Florida. All cells were maintained in subconfluent densities to allow cell division throughout the course of the experiments. Cells were plated in 48-well plates at 15,000 cells/well or in 8-well chamber slides at 8,000 cells/well on the day prior to transfection. Cells were transfected by replacing the cell culture medium with the mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticle solution or Lipofectamine 2000 supplemented with fresh culture medium to a final volume of 100 μL per well. Bafilomycin (1 μM) and chloroquine (50 μM) were added to the transfection media before addition to the wells. mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticle uptake and transfection efficiency were determined with a FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences) after trypsinization and washing with PBS.

To assess cytotoxicity, PI was added to the resuspended cells 1 min prior to analysis by flow cytometry. Caspase 3/7 activity was measured with the Caspase-Glo 3/7 Assay (Promega, #G8090) on a Cytation 3 plate reader (BioTek) 24 h after transfection, per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantification of endosomal escape

Endosomal disruption by Cy5-labeled niRFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles was visualized by confocal microscopy in Gal8-YFP HEK293T cells. Images were captured at 0, 30, or 60 min after addition of nanoparticles to cells grown overnight in 8-chambered glass slides (Thermo Scientific, #154534). Colocalization of Gal8-YFP punctae and Cy5-fluorescent nanoparticles was performed in Fiji/ImageJ using the ComDet plugin (https://imagej.net/Spots_colocalization_(ComDet)). To overcome the wide cell-to-cell variability in background cytoplasmic YFP signal, YFP punctae were manually masked prior to colocalization analysis with ComDet.

Proliferation, migration, and luciferase assay

For analysis of proliferation, 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) (Abcam, ab219801) was added to cells 4 h before collection. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and immunolabeled before flow cytometry per the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell viability was assayed 24 h after transfection with a WST-1 assay (Sigma-Aldrich, #5015944001) on a Cytation 3 plate reader (BioTek) per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell migration was measured with a scratch wound assay 24 h after transfection. Images were taken immediately after wounding and 24 h later, and the number of cells that migrated into the wound after 24 h was counted. To analyze the activity of our p27-miRNA switch, the results of these assays were normalized to GFP mRNA-transfected controls.

Luciferase activity was measured 24 h after transfection with Luc mRNA-p5RHH. Cells were rinsed with PBS prior to lysis with Cell Culture Lysis Reagent (Promega, #E1531). Luminescence was measured with a Cytation 3 plate reader (BioTek) using luciferase assay substrate (Promega, #E1500) per the manufacturer’s protocol.

Animal care and use

All experiments involving the use of mice were approved by the IACUC of the University of South Florida. C57BL6/J mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and housed in the USF Health Comparative Medicine Vivarium on a 12-h light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water.

Femoral artery wire injury mouse model and treatment

Femoral artery wire injuries were performed on C57BL6/J mice as previously described.34 Briefly, an EV3 X-celerator-10 exchange hydrophilic guidewire was inserted into the left femoral artery below the level of the knee and advanced to the branching of the abdominal aorta 10 times. The artery was then ligated just above the insertion site. The following day the mice were injected intravenously with 200 μL of mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles formed by mixing 40 nmol of p5RHH with 7 μg of either control niRFP mRNA or 1x126TS-p27-miRNA switch for 40 min at 37°C. The mice were treated every 3 days thereafter with the same dose of mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles for 2 weeks, a total of 5 doses. Animals were euthanized 15 days after surgery by CO2 asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation. The same concentrations of p5RHH and mRNA were used for the treatment of uninjured mice with GFP mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles or Luc mRNA-p5RHH nanoparticles.

Tissue processing

Mice were perfused with PBS after euthanasia, and the animals’ liver, spleen, kidneys, and lungs were collected. The injured and contralateral uninjured femoral arteries were collected as a single intact piece from the aortic arch through to below the insertion site of the guide wire. Organs and vessels were fixed overnight in 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA), followed by an overnight immersion in a cryoprotective 30% sucrose solution as previously described.5 The organs and vessels were then mounted in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound and cryosectioned at 10 μm thickness. The injured and uninjured femoral arteries were separated and the remaining aorta divided into 1 cm pieces prior to mounting in a single block to facilitate downstream analysis. Slides were stored at −80°C until use.

Tissues collected for mRNA analysis were snap frozen after collection and stored in liquid nitrogen until used. Tissues were homogenized, and total RNA was extracted with the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). cDNA was prepared by using oligo-d(t) (NEB) and M-MulV reverse transcriptase (NEB) as previously described.35 niRFP transcript level was assayed by SYBR RT-PCR using primers #17 and #18. Beta actin, measured using primers #19 and #20, was used as a loading control.

Tissues collected for protein expression analysis were snap frozen after collection and stored in liquid nitrogen until used. Tissues were homogenized, and proteins were extracted using ice cold Lysis Buffer, as previously described.36

Quantification of intima-to-media ratios

Four sections that spanned the entire length of the femoral arteries of each mouse (n = 5 for niRFP mRNA-p5RHH treated and n = 6 for p27-miRNA switch-p5RHH treated) were subjected to hematoxylin and eosin staining. Images of the injured and contralateral uninjured femoral arteries were captured with a Keyence BZ-X800 microscope at 40× magnification. Images were then analyzed by 2 blinded researchers. The intimal area was calculated as the lumen area minus the area between the internal elastic lamina and the lumen of the vessel, whereas the media area was calculated as the area between the adventitia and the internal elastic lamina. The ratio of the intima to media areas for each of the injured and uninjured vessels was averaged across 5 cross-sections taken along the length of the femoral artery of each animal.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting assays were performed as previously described.35 Briefly, proteins were extracted from cell or tissue lysates and subjected to size fractionation by SDS-PAGE. After transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane, proteins of interest were probed overnight at 4°C using antibodies against glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; rabbit monoclonal; 1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology #2118, RRID:AB_561053); GFP (rabbit polyclonal; 1:1,000; Thermo Fisher #A-6455, RRID:AB_221570); p27 (rabbit polyclonal; 1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology #2552, RRID:AB_10693314); or cleaved caspase 3 (Asp175) (rabbit polyclonal; 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology #9661, RRID:AB_2341188), followed by IRDye 680 donkey anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (1:5,000; LI-COR #926-68073, RRID:AB_10954442). Blots were imaged with the Odyssey CLx Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences) and quantified with Image Studio software (LI-COR Biosciences). Cleaved caspase 3 control cell extracts were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (#9662). GAPDH was used as a loading control.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Frozen tissue sections were dried for 2 h prior to processing. Sections used for immunolabeling were fixed in ice-cold acetone for 3 min. After blocking with 3% (w/v) bovine serum albumin and 2% normal goat serum for 30 min at room temperature, primary antibodies against CD31 (rat monoclonal; 1:100; BD Biosciences #550274, RRID:AB_393571) and Cy3-αSMA (mouse monoclonal; 1:1,000; Millipore Sigma # C6198, RRID:AB_476856) were used to probe sections overnight at 4°C, followed by Alexa Fluor 568 anti-rat IgG secondary antibody (goat polyclonal; 1:1,000; Thermo Fisher #A-11077, RRID:AB_141874). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (3 μM) during secondary antibody incubation before coverslips were mounted with Prolong Diamond Antifade Mountant (Thermo Fisher). Tissue sections were then examined with a FluoView FV1200 inverted laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus).

Statistics

Data was analyzed with Student’s t test, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test using GraphPad Prism 7.0 software. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of at least 3 independent experiments unless stated otherwise.

Data availability

Data generated in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 HL128411 to H.T.J., and the p5RHH synthesis work was supported by R01 DK102691, AR067491, and HL073646 to S.A.W.

Author contributions

H.T.J. conceived the idea. J.H.L., J.V., and H.T.J. designed the research, performed the experiments, and analyzed the data. R.B. performed the experiments. J.H.L. and H.T.J. wrote the paper. S.A.W. and H.P. provided conceptual and practical advice on experimental plans, contributed reagents and reviewed all data. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

S.A.W. holds a patent on the p5RHH RNA delivery (US9987371B2) and reports equity in Trasir Therapeutics (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.01.032.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Heron M. Deaths: Leading Causes for 2017. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 2019;68:1–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjamin E.J., Muntner P., Alonso A., Bittencourt M.S., Callaway C.W., Carson A.P., Chamberlain A.M., Chang A.R., Cheng S., Das S.R., American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139:e56–e528. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canfield J., Totary-Jain H. 40 Years of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: History and Future Directions. J. Pers. Med. 2018;8:E33. doi: 10.3390/jpm8040033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stone G.W., Moses J.W., Ellis S.G., Schofer J., Dawkins K.D., Morice M.C., Colombo A., Schampaert E., Grube E., Kirtane A.J. Safety and efficacy of sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting coronary stents. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;356:998–1008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santulli G., Wronska A., Uryu K., Diacovo T.G., Gao M., Marx S.O., Kitajewski J., Chilton J.M., Akat K.M., Tuschl T. A selective microRNA-based strategy inhibits restenosis while preserving endothelial function. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124:4102–4114. doi: 10.1172/JCI76069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lockhart J., Canfield J., Mong E.F., VanWye J., Totary-Jain H. Nucleotide Modification Alters MicroRNA-Dependent Silencing of MicroRNA Switches. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2019;14:339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2018.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hou K.K., Pan H., Lanza G.M., Wickline S.A. Melittin derived peptides for nanoparticle based siRNA transfection. Biomaterials. 2013;34:3110–3119. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mills K.A., Quinn J.M., Roach S.T., Palisoul M., Nguyen M., Noia H., Guo L., Fazal J., Mutch D.G., Wickline S.A. p5RHH nanoparticle-mediated delivery of AXL siRNA inhibits metastasis of ovarian and uterine cancer cells in mouse xenografts. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:4762. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41122-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weng Y.H., Li C.H., Yang T.R., Hu B., Zhang M.J., Guo S., Xiao H.H., Liang X.J., Huang Y.Y. The challenge and prospect of mRNA therapeutics landscape. Biotechnol Adv. 2020;40:107534. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2020.107534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karikó K. In vitro-Transcribed mRNA Therapeutics: Out of the Shadows and Into the Spotlight. Mol. Ther. 2019;27:691–692. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramaswamy S., Tonnu N., Tachikawa K., Limphong P., Vega J.B., Karmali P.P., Chivukula P., Verma I.M. Systemic delivery of factor IX messenger RNA for protein replacement therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E1941–E1950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1619653114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashimoto M., Takemoto T. Electroporation enables the efficient mRNA delivery into the mouse zygotes and facilitates CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:11315. doi: 10.1038/srep11315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pardi N., Hogan M.J., Pelc R.S., Muramatsu H., Andersen H., DeMaso C.R., Dowd K.A., Sutherland L.L., Scearce R.M., Parks R. Zika virus protection by a single low-dose nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccination. Nature. 2017;543:248–251. doi: 10.1038/nature21428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richner J.M., Himansu S., Dowd K.A., Butler S.L., Salazar V., Fox J.M., Julander J.G., Tang W.W., Shresta S., Pierson T.C. Modified mRNA Vaccines Protect against Zika Virus Infection. Cell. 2017;168:1114–1125.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schnee M., Vogel A.B., Voss D., Petsch B., Baumhof P., Kramps T., Stitz L. An mRNA Vaccine Encoding Rabies Virus Glycoprotein Induces Protection against Lethal Infection in Mice and Correlates of Protection in Adult and Newborn Pigs. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016;10:e0004746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jopling C.L., Yi M., Lancaster A.M., Lemon S.M., Sarnow P. Modulation of hepatitis C virus RNA abundance by a liver-specific MicroRNA. Science. 2005;309:1577–1581. doi: 10.1126/science.1113329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parr C.J.C., Wada S., Kotake K., Kameda S., Matsuura S., Sakashita S., Park S., Sugiyama H., Kuang Y., Saito H. N 1-Methylpseudouridine substitution enhances the performance of synthetic mRNA switches in cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:e35. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitada T., DiAndreth B., Teague B., Weiss R. Programming gene and engineered-cell therapies with synthetic biology. Science. 2018;359:eaad1067. doi: 10.1126/science.aad1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wroblewska L., Kitada T., Endo K., Siciliano V., Stillo B., Saito H., Weiss R. Mammalian synthetic circuits with RNA binding proteins for RNA-only delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:839–841. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hou K.K., Pan H., Ratner L., Schlesinger P.H., Wickline S.A. Mechanisms of nanoparticle-mediated siRNA transfection by melittin-derived peptides. ACS Nano. 2013;7:8605–8615. doi: 10.1021/nn403311c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan H., Palekar R.U., Hou K.K., Bacon J., Yan H., Springer L.E., Akk A., Yang L., Miller M.J., Pham C.T. Anti-JNK2 peptide-siRNA nanostructures improve plaque endothelium and reduce thrombotic risk in atherosclerotic mice. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2018;13:5187–5205. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S168556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kilchrist K.V., Dimobi S.C., Jackson M.A., Evans B.C., Werfel T.A., Dailing E.A., Bedingfield S.K., Kelly I.B., Duvall C.L. Gal8 Visualization of Endosome Disruption Predicts Carrier-Mediated Biologic Drug Intracellular Bioavailability. ACS Nano. 2019;13:1136–1152. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b05482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogris M., Carlisle R.C., Bettinger T., Seymour L.W. Melittin enables efficient vesicular escape and enhanced nuclear access of nonviral gene delivery vectors. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:47550–47555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108331200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rozema D.B., Ekena K., Lewis D.L., Loomis A.G., Wolff J.A. Endosomolysis by masking of a membrane-active agent (EMMA) for cytoplasmic release of macromolecules. Bioconjug. Chem. 2003;14:51–57. doi: 10.1021/bc0255945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chou S.T., Hom K., Zhang D., Leng Q., Tricoli L.J., Hustedt J.M., Lee A., Shapiro M.J., Seog J., Kahn J.D., Mixson A.J. Enhanced silencing and stabilization of siRNA polyplexes by histidine-mediated hydrogen bonds. Biomaterials. 2014;35:846–855. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arvizo R.R., Miranda O.R., Thompson M.A., Pabelick C.M., Bhattacharya R., Robertson J.D., Rotello V.M., Prakash Y.S., Mukherjee P. Effect of nanoparticle surface charge at the plasma membrane and beyond. Nano Lett. 2010;10:2543–2548. doi: 10.1021/nl101140t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilleron J., Querbes W., Zeigerer A., Borodovsky A., Marsico G., Schubert U., Manygoats K., Seifert S., Andree C., Stöter M. Image-based analysis of lipid nanoparticle-mediated siRNA delivery, intracellular trafficking and endosomal escape. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:638–646. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan H., Myerson J.W., Ivashyna O., Soman N.R., Marsh J.N., Hood J.L., Lanza G.M., Schlesinger P.H., Wickline S.A. Lipid membrane editing with peptide cargo linkers in cells and synthetic nanostructures. FASEB J. 2010;24:2928–2937. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-153130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schrom E., Huber M., Aneja M., Dohmen C., Emrich D., Geiger J., Hasenpusch G., Herrmann-Janson A., Kretzschmann V., Mykhailyk O. Translation of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 upon Liver- and Lung-Targeted Delivery of Optimized Chemically Modified mRNA. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2017;7:350–365. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng Q., Wei T., Farbiak L., Johnson L.T., Dilliard S.A., Siegwart D.J. Selective organ targeting (SORT) nanoparticles for tissue-specific mRNA delivery and CRISPR-Cas gene editing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020;15:313–320. doi: 10.1038/s41565-020-0669-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karikó K., Muramatsu H., Welsh F.A., Ludwig J., Kato H., Akira S., Weissman D. Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA yields superior nonimmunogenic vector with increased translational capacity and biological stability. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:1833–1840. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sahin U., Karikó K., Türeci Ö. mRNA-based therapeutics--developing a new class of drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014;13:759–780. doi: 10.1038/nrd4278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Totary-Jain H., Naveh-Many T., Riahi Y., Kaiser N., Eckel J., Sasson S. Calreticulin destabilizes glucose transporter-1 mRNA in vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells under high-glucose conditions. Circ. Res. 2005;97:1001–1008. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000189260.46084.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shan J., Nguyen T.B., Totary-Jain H., Dansky H., Marx S.O., Marks A.R. Leptin-enhanced neointimal hyperplasia is reduced by mTOR and PI3K inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:19006–19011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809743105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mong E.F., Akat K.M., Canfield J., Lockhart J., VanWye J., Matar A., Tsibris J.C.M., Wu J.K., Tuschl T., Totary-Jain H. Modulation of LIN28B/Let-7 Signaling by Propranolol Contributes to Infantile Hemangioma Involution. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018;38:1321–1332. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.310908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Canfield J., Arlier S., Mong E.F., Lockhart J., VanWye J., Guzeloglu-Kayisli O., Schatz F., Magness R.R., Lockwood C.J., Tsibris J.C.M. Decreased LIN28B in preeclampsia impairs human trophoblast differentiation and migration (vol 33, pg 2759, 2019) FASEB J. 2019;33:6683. doi: 10.1096/fj.201801163R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data generated in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.