Abstract

DNA methylation abnormality is closely related to tumor occurrence and development. Chemical inhibitors targeting DNA methyltransferase (DNMTis) have been used in treating cancer. However, the impact of DNMTis on antitumor immunity has not been well elucidated. In this study, we show that zebularine (a demethylating agent) treatment of cancer cells led to increased levels of interferon response in a cyclic guanosine monophosphate-AMP (cGAMP) synthase (cGAS)- and stimulator of interferon genes (STING)-dependent manner. This treatment also specifically sensitized the cGAS-STING pathway in response to DNA stimulation. Incorporation of zebularine into genomic DNA caused demethylation and elevated expression of a group of genes, including STING. Without causing DNA damage, zebularine led to accumulation of DNA species in the cytoplasm of treated cells. In syngeneic tumor models, administration of zebularine alone reduced tumor burden and extended mice survival. This effect synergized with cGAMP and immune checkpoint blockade therapy. The efficacy of zebularine was abolished in nude mice and in cGAS−/− or STING−/− mice, indicating its dependency on host immunity. Analysis of tumor cells indicates upregulation of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) following zebularine administration. Zebularine promoted infiltration of CD8 T cells and natural killer (NK) cells into tumor and therefore suppressed tumor growth. This study unveils the role of zebularine in sensitizing the cGAS-STING pathway to promote anti-tumor immunity and provides the foundation for further therapeutic development.

Keywords: DNA methyltransferase, cGAS, STING, cGAMP, zebularine, DNA methylation, cancer immunotherapy, PD-1, epigenetic regulation, DNA sensing

Graphical abstract

Lai et al. demonstrate that zebularine sensitizes the cGAS-STING pathway to enhance anti-tumor immunity, which is associated with demethylation and upregulation of the STING gene. Synergizing with cGAMP, zebularine promotes infiltration of CD8 T cells and NK cells in cancer treatments.

Introduction

As a major part of epigenetic modification, DNA methylation plays a pivotal role in many cellular functions, and its abnormality is closely related to the occurrence, development, and prognosis of cancer.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 DNA methylation is catalyzed by DNA methytransferases (DNMTs).6 DNMT1 is involved in the maintenance of cytosine (C) methylation during DNA replication, while DNMT3 is involved in de novo methylation of the unmethylated site.6,7 DNMTs are overexpressed in many cancer types and are associated with chemotherapy tolerance.8 Two types of DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (DNMTis, also known as demethylating agents), including nucleoside and non-nucleoside DNA methyltransferase inhibitors, have been developed.9,10 Nucleoside DNMTis such as 5-azacytidine (Aza) and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (Dac) have been approved for treating myelodysplastic syndrome, acute myeloid leukemia, and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia by the US Food and Drug Administration.9,11

In a number of clinical trials, DNMTis have been tested as monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy drugs such as carboplatin and cisplatin for treating solid tumors.12, 13, 14, 15 For example, low-dose, multi-day, multi-cycle decitabine administration displayed a significant clinical response and restored the sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs in solid tumors.15 However, the antitumor effects of DNMTis have not been well correlated with their DNA demethylation capabilities.13,15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 Instead, DNMTis have shown multifaceted roles, including alteration of cellular signaling pathways and cell cycle activity, anti-cell proliferation, and altered stem cell function, among others.24 Particularly, DNMTis have been shown to possess the immune regulatory roles in many studies.25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 DNMTis may also be an important regulator of interleukin (IL)-2 immune activation in the treatment of melanoma and renal cell carcinoma patients.31 Immune regulatory signals and genes including interferons (IFNs) and IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) are significantly enhanced by DNMTis in various cancer cells.2,25,27,33, 34, 35, 36 DNMTis are able to affect tumor-associated antigen expression and presentation, which leads to enhanced T cell recognition of tumors.37,38 DNMTi treatment can enhance the inhibitory effects of immune checkpoints.39,40 Therefore, DNMTis may recruit and activate immune cells to kill tumor cells by producing IFNs, enhancing antiviral reaction or other immune regulation mechanisms to reduce tumor burden.41,42

Cyclic guanosine monophosphate-AMP (cGAMP) synthase (cGAS) is a major cytosolic DNA sensor. Once bound to DNA, it catalyzes the production of cGAMP using ATP and guanosine triphosphate (GTP) as substrates. As a high-affinity ligand, cGAMP then binds to stimulator of IFN genes (STING) protein, which in turn activates TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) and IκB kinase (IKK), leading to activation and nuclear translocation of IFN regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), respectively,43, 44, 45 which are essential for induction of cytokines, including IFN, and initiation of adaptive immune responses. Accumulating evidence indicates that the cGAS/STING-mediated DNA sensing pathway is a promising therapeutic target for treating cancers.46 cGAS is indispensable for therapeutic effects of immune checkpoint blockade therapy,47, 48, 49 and STING agonists can promote function of antigen-presenting cells, alter the tumor microenvironment, and induce the production of tumor-specific T cells.50, 51, 52, 53, 54

In this study, we took zebularine as a tool to explore the role of DNMTis in modulating immune functions. In multiple cancer cell lines, zebularine treatment sensitized the cGAS-STING pathway by demethylating the STING promoter and generation of cytoplasmic DNA. Oral administration of zebularine in mice exhibited marked therapeutic effects that synergized with cGAMP in syngeneic tumor models. Importantly, the antitumor effect of zebularine depends on cGAS-STING signaling to recruit CD8+ T cells and natural killer (NK) cells into the tumor microenvironment. This work unveils a novel mechanism of the anti-tumor property of zebularine and provides a foundation for use of DNMTis as immunotherapy drugs.

Results

Zebularine-sensitized cGAS-STING pathway in cancer cells

Alternation of the epigenetic landscape could have complex effects on cellular functions. To investigate the impact of DNMTis on innate immune signaling in cancer cells, we chose zebularine based on its improved bioavailability and toxicity profile over other DNMTis such as Aza and Dac.55,56 When AGS, a human gastric adenocarcinoma cell line, was treated with increasing concentrations of zebularine for 4 days, we observed a low level but reproducible upregulation of IFNβ (Figure 1A) and Cxcl10 (Figure 1B) genes in a dose-dependent manner. The phenomenon repeated itself in B16F10, a mouse melanoma cell line (Figures 1C and 1D). Interestingly, upregulation of type I IFN by zebularine as well as Dac treatment was abolished in AGS STING−/− cells (Figures 1E and 1F); zebularine also failed to induce IFNβ in B16 cells that lack cGAS or STING (Figure 1G), suggesting that its effect relies on the DNA-sensing pathway. We pretreated AGS cells with DMSO or zebularine followed by stimulation with herring testis (HT)-DNA and cGAMP, which activate the cGAS-STING pathway, and poly(I:C), which is a double-stranded RNA surrogate and activates either the Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) or MDA5-MAVS pathway, and then measured IFN responses. Interestingly, pretreatment with zebularine led to enhanced induction of the IFNβ gene by HT-DNA and cGAMP (Figures 1H and 1I), but it had little effect on IFN response induced by poly(I:C) (Figure 1J), indicating that zebularine specifically enhances the DNA-sensing pathway. In B16F10 cells, pretreatment with zebularine enhanced an IFN response to cGAMP (Figure 1K) and HT-DNA (Figure 1L), but not poly(I:C) treatment (Figure 1L). It is noteworthy that zebularine caused upregulation of STING (Figure 1K), which is further addressed later. To visually observe the effect of zebularine on cell response, we used a B16F10 reporter cell line stably expressing GFP under the control of an IFN promoter. Pretreatment with zebularine led to an increased population of GFP+ cells compared to untreated cells upon HT-DNA and cGAMP stimulation, but not poly(I:C) stimulation (Figure 1M). The enhancing effect of zebularine on the DNA-sensing pathway was repeatedly observed in several other cell lines, including SGC-7901, MC38, BJ, and L929 (see Figure S1). Consistent with the above observation, pretreatment with zebularine led to stronger phosphorylation of TBK1 and IRF3 in AGS and B16F10 cells exposed to cGAMP or HT-DNA (Figures 1N and 1O). The expression of STING was upregulated by zebularine whereas cGAS was not affected (Figures 1N and 1O). Taken together, these cellular experiments demonstrated that zebularine can enhance the DNA-sensing pathway in multiple cancer lines.

Figure 1.

Zebularine sensitizes the cGAS-STING pathway in cancer cells

(A–D) Zebularine induces basal levels of type I interferon (IFN) and ISGs in cells. AGS (A and B) and B16F10 (C and D) cells were treated with the indicated doses of zebularine for 4 days, IFNβ and Cxc10 levels were measured by qRT-PCR. (E–G) Zebularine-induced IFNβ was STING-dependent. Wild-type (WT) or Sting−/− AGS cells were exposed to indicated concentrations of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (Dac) (E) or zebularine (F) for 4 days, followed by measurement of IFNβ expression using qRT-PCR. (G) WT, Cgas−/−, and Sting−/− B16F10 cells were exposed to 10 μM zebularine for 4 days, followed by measurement of IFNβ expression using qRT-PCR. (H–J) Zebularine enhances the DNA-sensing pathway in AGS cells. AGS cells pretreated with DMSO or 25 μM zebularine for 4 days were stimulated with HT-DNA for 6 h (H), cGAMP for 4 h (I), or poly(I:C) for 8 h (J), followed by measurement of IFNβ RNA levels using qRT-PCR. (K–M) Zebularine enhances the DNA-sensing pathway in B16 cells. (K) B16F10 cells were pretreated with 10 μM zebularine or left untreated for 4 days and then stimulated with cGAMP for 4 h, followed by measurement of IFNβ RNA levels using qRT-PCR. (L) B16F10 cells were pretreated with 20 μM zebularine or left untreated for 4 days, then stimulated with HT-DNA or poly(I:C), followed by measurement of IFNβ in the media using ELISA after 16 h. (M) B16F10-mCherry-IFNβ promoter-GFP cells untreated or treated with 20 μM zebularine were stimulated with HT-DNA for 6 h, cGAMP for 4 h, or poly(I:C) for 8 h, and GFP-positive cells (representing IFN induction) were quantified using FACS. (N) AGS cells pretreated with 50 μΜ zebularine or buffer control were stimulated with cGAMP for 2 h, and key signaling molecules were detected with immunoblots. (O) B16F10 cells pretreated with 20 μΜ zebularine or buffer control were stimulated with HT-DNA for 3 h, and key signaling molecules were detected with immunoblotting. Error bars represent the standard deviation of at least three independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 by Student’s t test.

Zebularine demethylates the STING gene

The upregulation of STING by zebularine suggests that levels of one or more components of the DNA-sensing pathway might be increased upon zebularine exposure, likely due to epigenetic regulation on gene transcription. To gain further insight into the mechanism, we first tested whether the effect of zebularine is dependent on its action on DNA methylation. In order to be incorporated into genomic DNA (gDNA) and block activity of methyltransferase, nucleoside DNMTis must be phosphorylated by deoxycytidine kinase (DCK).57,58 We therefore deleted DCK in AGS cells (Figures 2A and 2B) and found that zebularine no longer increased expression of STING or the IFNβ gene, nor did it enhance the DNA-sensing pathway that leads to IFNβ production, indicating that the action of zebularine is indeed through alternation of DNA methylation status. To directly evaluate the impact of zebularine on DNA methylation in cells, we performed methylation-sensitive melt curve analysis (MS-MCA) on the promoter of the reprimo (RPRM) gene, a key indicator of genomic methylation in cancer cells.59 Zebularine treatment of AGS cells for increasing durations caused progressive shift of the melting curve toward a lower temperature (Figure 2C), indicating treatment-dependent demethylation. Importantly, this demethylation was abolished when the DCK gene was deleted (Figure 2D), again confirming the previously reported mechanism of action. Since zebularine increased expression of the STING gene, we analyzed the methylation of this gene and its promoter using the bisulfite sequencing technique. We found multiple sites of methylation at the promoter of STING gene in untreated cells, which were demethylated after zebularine treatment (Figure 2E, arrowheads). Interestingly, combination of zebularine and cGAMP treatments led to additional demethylation sites at the STING promoter. Quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and immunoblots also independently confirmed that zebularine increased the STING, but not cGAS, expression at both the mRNA and protein levels (Figures 2F and 2G). In addition, we treated B16 melanoma-bearing mice with zebularine for 15 days, isolated tumor cells, dendritic cells (DCs), and macrophages by magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) technology (Miltenyi Biotec), and measured the STING expression in these cells by quantitative real-time PCR (Figure 2I). Consistent with the observation from in vitro cellular experiments, zebularine enhanced the expression of STING in the tumor cells, DCs, and macrophages (Figure 2I) in mice. We also analyzed the expression of STING in several subtypes of immune cells derived from the spleens of tumor-bearing mice by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (see Figure S5). With the zebularine treatment, the values of MFI (median fluorescence intensity) of STING in lymphocytes, T cells, macrophages, and DCs are significantly higher than in the mock-treated group (Figure 2H). These results suggest that zebularine sensitizes the cGAS-STING pathway by epigenetically upregulating the key player STING.

Figure 2.

Zebularine demethylates the STING gene

(A and B) AGS and AGS-DCK−/− cells were pre-treated with 50 μM zebularine for 6 days and stimulated with DNA for 6 h. Gene expression of STING (A) and IFNβ (B) were analyzed by qRT-PCR. (C) AGS cells were treated with 100 μM zebularine for 1–4 days as indicated, and the methylation of the RPRM promoter region was analyzed by methylation-sensitive melt curve analysis (MS-MCA). U and M are the unmethylated and methylated controls, respectively. (D) AGS and AGS-DCK−/− cells were treated with zebularine or DMSO for 4 days, and the methylation of the RPRM promoter region was analyzed by MS-MCA. (E) Bisulfite sequencing of the STING promoter from AGS cells left untreated, treated with 50 μM zebularine for 4 days, treated with 100 nM cGAMP for 4 hours, or a combination of both. Blue Cs denote methylated CpG sites, which were converted to Ts when they are demethylated upon treatment (arrowheads). (F) Expression levels of cGAS and STING in AGS cells treated with 50 μM zebularine as measured by qRT-PCR. (G) Immunoblot of cGAS and STING in B16 cells treated with 10 μM zebularine. (H) The STING median fluorescence intensities of CD45, CD3, DCs, and macrophages were analyzed by FACS. Please see Figure S5 for the gating strategies. (I) The STING expression of DCs and macrophages, which were isolated from the spleens by magnetic bead sorting, was analyzed by qRT-PCR. Error bars represent the standard deviation of at least three independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by Student’s t test.

Zebularine treatment generates cytoplasmic DNA

The observation that zebularine upregulated expression of IFNβ and ISGs in a cGAS-dependent manner (Figure 1) suggests that it may directly activate cGAS. To test this possibility, we utilized an in vitro assay that directly measures cGAS activity. In this assay, cGAS converts ATP and GTP into cGAMP in the presence of DNA and MgCl2, and therefore its activity can be monitored by quantification of remaining ATP levels with Kinase-Glo.43,60 The presence of zebularine up to 1 mM in the reaction had no effect on the cGAS catalytic activity (data not shown), suggesting that zebularine does not act on cGAS to stimulate its activity. The other possibility is that zebularine in cells generated a factor upstream of cGAS, for which cytoplasmic DNA is a most likely candidate. To directly test this possibility, we exposed AGS cells to zebularine or Ara-C, a compound known to cause genome damage and accumulation of cytoplasmic DNA, and stained them with anti-double stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibody in an immunofluorescence (IF) assay. Zebularine, as well as Ara-C, led to accumulation of DNA in the cytoplasm (Figure 3A). Interestingly, unlike Ara-C, zebularine did not cause DNA damage, as indicated by a phosphorylated (phospho-)H2A immunoblot (Figure 3B). Consistent with the IF data, cytoplasmic DNA can be isolated using conditions that prevented leakage of gDNA and visualized on agarose gel by electrophoresis (Figure 3C). These DNA61, 62, 63 isolates from zebularine-treated cells, but not from control cells, induced IFNβ and ISG15 when transfected to THP1 cells (Figure 3D). To further confirm activation of cGAS in zebularine-treated cells, we devised a bioassay that can detect low concentrations of cGAMP from cell lysates. In this assay, proteins from the cytosol were removed by heating and centrifugation, and supernatants were passed through 30-kDa cutoff filters to further remove large molecules. The resulting filtrates containing cGAMP were quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Figure 3E). These results indicate that zebularine treatment led to generation of cytoplasmic DNA species that subsequently activated the cGAS-STING pathway.

Figure 3.

Zebularine promotes the production of cytoplasmic DNA and cGAMP

(A) AGS cells exposed to zebularine (50 and 100 μM) or Ara-C (1 μM) for 4 days were stained with anti-dsDNA antibody (red) and counterstained with DAPI blue). Scale bars represent 20 μm for upper images or 10 μm for lower images. (B) Immunoblot of phospho-H2A using lysates from AGS cells pretreated with indicated compounds. (C) Agarose gel electrophoresis showing cytoplasmic DNA isolate from AGS cells treated with indicated compounds. (D) Cytoplasmic DNA isolate from AGS cells treated with zebularine or control was transfected to THP1 cells followed by measurement of IFNβ and ISG15 expression using qRT-PCR after 6 h. (E) Small molecule extracts from AGS cells treated with zebularine or control were measured by ELISA. Error bars represent the standard deviation of at least three independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by Student’s t test.

Therapeutic effects of zebularine in syngeneic tumor models and its dependency on cGAS-STING signaling

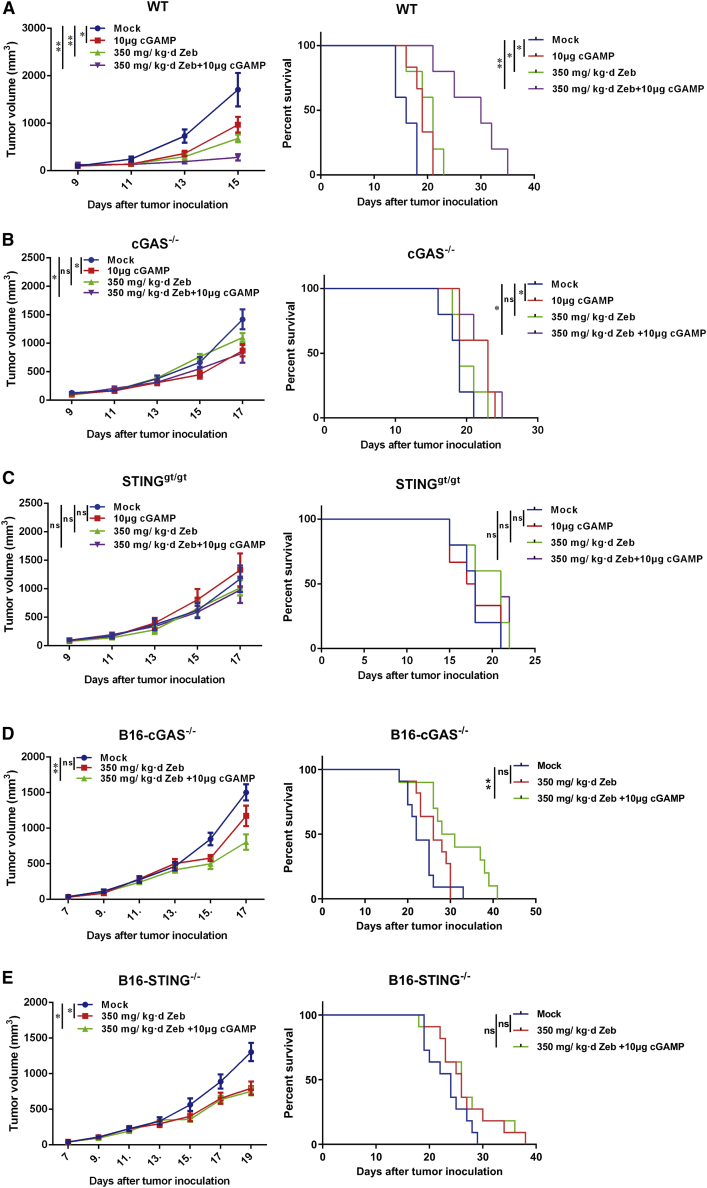

The cGAS-STING pathway is pivotal in immunity against cancer. Injection of cGAMP or its derivatives can promote an immune response to cancer.64 Immune checkpoint blockade therapy also relies on the cGAS-STING pathway. In light of its remarkable impact on the cGAS-STING pathway, we investigated the therapeutic effect of zebularine in syngeneic tumor models. Mice with established B16F10 tumors were given zebularine in their drinking water. Without inducing any observable adverse effect as indicated by the normal indexes of kidney and liver function (see Table S1), zebularine significantly suppressed tumor growth and prolonged survival of mice (Figure 4A). The effect of zebularine is comparable to that of cGAMP treatment, which is known for its therapeutic effect in multiple syngeneic tumor models. When administered together, zebularine and cGAMP further reduced tumor burden and extended survival, showing a synergistic effect. To test the role of the host cGAS-STING pathway, we treated B16F10 tumors implanted on Cgas−/− and Stinggt/gt mice, respectively. Deficiency in either cGAS or STING largely abolished the therapeutic effect of zebularine, while the effect of cGAMP treatment was abolished in Stinggt/gt mice but was still present in Cgas−/− mice (Figures 4B and 4C), consistent with previous reports.47,64 To confirm that the anti-tumor effect of zebularine depends on an intact adaptive immunity, we implanted B16 tumors on nude mice and treated them with zebularine, cGAMP, or a combination of both. Neither treatment showed any effect on tumor growth (see Figures S2A–S2C). The therapeutic effect of zebularine was not limited to B16 tumors, but also in some cancer cells with lower IFNβ expression after induction by HT-DNA. In the Panc02 syngeneic model, which represents highly aggressive pancreatic cancer, zebularine alone markedly suppressed tumor growth and exhibited synergy with cGAMP treatment (see Figure S2D). In the MC38 tumor model, which represents colon carcinoma, zebularine suppressed tumor growth to a similar extent as cGAMP (see Figure S2E), and it exhibited a better effect in extending life than did the latter (see Figure S2F). A combination of the two again further improved mice survival. The therapeutic effect of combining zebularine and cGAMP can be further improved by addition of anti-PD-L1 antibody, an immune checkpoint inhibitor used in clinics. The triple combination led to more robust control of tumor growth and markedly extended survival in the B16F10 model (see Figures S2G and S2H). We stopped drug treatment after more than half of the wild-type mice died on day 16. At this time point, we saw a similar effect from triple combination compared to the cGAMP+zebularine group. However, further statistics on the tumor growth and survival curve showed that triple combination led to more robust control of tumor growth and markedly extended survival in the B16F10 model.

Figure 4.

cGAS-STING-dependent anti-tumor efficacy of zebularine

(A) C57BL/6 mice (n = 5 each group) bearing B16F10 tumors were mock treated or given 10 μg of cGAMP subcutaneously, 350 mg/kg/day zebularine via drinking water, or the combination of both for the indicated days. Tumor growth (left panel) and mouse survival (right panel) were monitored. (B) The same as (A), except Cgas−/− mice (n = 5 each group) were used. (C) The same as (A) and (B), except Stinggt/gt mice (n = 6 each group) were used. (D) C57BL/6 mice (n = 11 each group) bearing B16-Cgas−/− tumors were mock treated or given 350 mg/kg/day zebularine via drinking water alone or in combination with 10 μg of cGAMP injected subcutaneously for the indicated days. Tumor growth (upper panel) and mice survival (lower panel) were monitored. (E) The same as (D), except B16-Sting−/− tumors were used. Tumor growth curves represent mean ± SEM. ∗∗p < 0.01 by two-way ANOVA. In survival curves, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test.

Since zebularine can enhance the DNA-sensing pathway in tumor cell lines, we compared its therapeutic effects among tumors established from wild-type, Cgas−/−, and Sting−/− B16 cells. Interestingly, deletion of cGAS in tumors largely abolished the effect of zebularine on tumor growth and survival of mice (Figure 4D), while deletion of STING markedly reduced its efficacy (Figure 4E). Although zebularine still had a partial inhibitory effect on the growth of STING−/− tumors, its effect on overall survival was greatly diminished, indicating the importance of tumor STING. We reasoned that the effect of zebularine on tumor cells is multifaceted. Zebularine causes accumulation of cytosolic DNA, which activates cGAS to generate cGAMP. Both cytosolic DNA and cGAMP can be eventually taken up by surrounding phagocytes and trigger an immune response. Tumor cells can also generate cytokines following STING activation, further stimulating host immune cells. Therefore, both cGAS and STING in tumors contribute to the efficacy of zebularine, with cGAS to a greater extent. Collectively, these results indicate that the therapeutic efficacy of zebularine depends on the cGAS-STING pathway in both host and tumor cells.

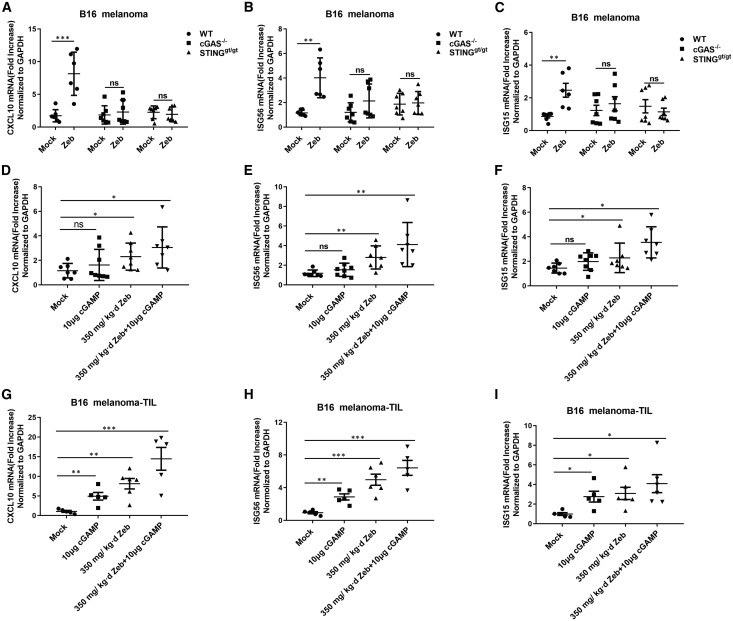

Zebularine promotes T cell and NK cell responses

We have shown that exposure to zebularine led to the higher basal levels of ISGs and enhanced IFN response to DNA and cGAMP in cultured tumor cell lines (Figure 1; see Figure S1). In this study, to gain insight into how zebularine promotes antitumor activity, we treated mice bearing B16 tumors with zebularine for 15−17 days and measured cytokine production in the tumor body. Consistent with observations in cell lines, zebularine treatment led to upregulation of ISGs, including ISG56, CXCL10, and ISG15 (Figures 5A–5C), in tumors. Furthermore, this upregulation was largely diminished when cGAS or STING was deleted from mice, suggesting that most cytokines were contributed by host cells. To find out to what degree tumor cells and host cells each contributed to cytokine production, we separated tumor cells (Figures 5D–5F) and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) (Figures 5G–5I) following treatments and measured cytokines again. While in both tumor cells and TILs zebularine caused increased expression of ISGs and led to stronger responses to cGAMP treatment, the effects were much more evident in TILs than in tumor cells, again suggesting that larger portions of cytokines originated from TILs. Kinetics studies indicate that the expression levels of ISGs peaked at 12 h after cGAMP injection, and slowly decreased after 24 h (see Figures S6A and S6B).

Figure 5.

Zebularine induces ISGs in tumors

(A–C) RNA levels of indicated ISGs from B16 tumors on WT, Cgas−/−, or Stinggt/gt mice mock treated or treated with zebularine for 17 days (n > 5 for each group). (D–F) RNA levels of indicated ISGs from purified B16 tumor cells (devoid of immune cells) from mice mock treated or treated with cGAMP, zebularine, or the combination of both (n = 7 for each group). (G–I) RNA levels of indicated ISGs in tumor-infiltrating leukocytes (TILs) from mice mock-treated or treated with cGAMP, zebularine, or the combination of both (n > 5 for each group). Error bars represent the standard deviation of at least three independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by Student’s t test.

Cancer immunotherapies aim to promote the host immunity using checkpoint inhibitors or STING agonists. CD8 T cells seem to be pivotal in both scenarios. To understand how T cells contribute to the therapeutics of zebularine, we analyzed the composition of TILs enriched from tumors that were treated with zebularine and/or cGAMP. Both zebularine and cGAMP led to a marked CD8 T cell increase in tumors; combined treatment further increased the percentage of CD8 T cells. Importantly, the enhanced CD8 T cell response was abolished in mice lacking either cGAS or STING (Figures 6A–6C). In contrast, CD4 T cells were only marginally increased following zebularine and cGAMP treatments (Figures 6D and 6E). These cGAS-STING-dependent mobilizations of CD8 T cells response are consistent with other reports.53,54

Figure 6.

Zebularine increases tumor-infiltrating T cells

B16F10 tumors were implanted onto WT, Cgas−/−, or Stinggt/gt mice, which were subsequently mock treated or treated with cGAMP, zebularine, or the combination of both for 17 days (n = 4 for each group). TILs were isolated for T cell analysis by FACS. (A–C) Tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells (defined as CD45+, CD3+, CD8+) from WT (A), Cgas−/−(B), and Stinggt/gt (C) mice. (D–F) Tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T cells (defined as CD45+, CD3+, CD4+) from WT (D), Cgas−/−(E), and Stinggt/gt (F) mice. Error bars represent the standard deviation of at least three independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by Student’s t test.

NK cells are cytotoxic innate lymphocytes that can directly kill tumor cells with low or no expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I. Our FACS analyses indicate that zebularine treatment significantly increased the numbers of NK cells (CD45+, CD3−, NK1.1+) in tumors, which was further increased after combining with cGAMP treatment (Figure 7). Elevation of the NK cell population was abolished in Cgas−/− and Sting−/− mice, again underscoring the role of the host DNA-sensing pathway in recruitment of immune cells. In addition, T cells enriched from zebularine-treated C57BL/6 mice had an advanced therapeutic effect for adoptive treatment in the nude mice tumor mode, suggesting an important role of T cells in mediating the anti-tumor effect (see Figure S2I).

Figure 7.

Zebularine increases the numbers of NK cells in tumor

(A) Growth curves of B16F10 melanoma in C57BL/6 mice (n = 3 each group) mock treated or treated with indicated doses of cGAMP, zebularine, or both for 17 days. (B) Populations of NK cells in tumors from mice in (A) as analyzed with FACS. (C–E) Growth curves of B16F10 melanoma in WT (C), Cgas−/− (D), and Stinggt/gt (E) mice (n = 5 each group) treated with zebularine or mock treated for 18 days. (F) Populations of NK cells in tumors from mice in (C)–(E) as analyzed with FACS. Tumor growth curves represent mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 by two-way ANOVA. In (B) and (F), error bars represent the standard deviation of at least three independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by Student’s t test.

Discussion

Drugs targeting epigenetic regulation, including DNMTis, have been used as chemotherapy in the treatment of cancer for a long time. Although their immunomodulatory effect has emerged in recent years, how they activate the adaptive immune system to fight malignancies is not well understood. In this work, we first found that zebularine, one of the DNMTis with improved bioavailability and tolerability, caused systemic changes in tumor cells, including accumulation of DNA species in cytoplasm and sensitization of the cGAS-STING pathway, which was associated with demethylation and upregulation of genes, including STING. In a cGAS-STING-dependent manner, zebularine exhibited therapeutic effects in multiple syngeneic tumor models. Synergizing with cGAMP and immune checkpoint blockade antibodies, zebularine facilitated tumor infiltration of CD8 T cells and NK cells. Type I IFNs are well known for their immunomodulatory activity, particularly immunosurveillance which is critical for its anti-cancer activities.65,66 IFNs are vital for activating innate and adaptive immunity such as increasing cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity, enhancing the generation of T helper cells, activating NK cells,67,68 and inducing macrophage activity.69 As shown in the previous study by Chiappinelli et al.,36 DNMTis play a role in inducing type I IFNs by activating dsRNA sensors, which sensitizes cancer patients’ responses to immunotherapy.13 As a DNMTi, zebularine might act differently by targeting DNA signaling pathways while still resulting in the induction of type I IFNs, thus contributing to enhanced anti-tumor effects.

It has been well recognized that the cGAS-STING pathway is essential for generating anti-tumor immunity.64,70,71 cGAMP activates STING in phagocytes including macrophages and induces type I IFN production to trigger immune responses.72, 73, 74 Debris from dead tumor cells can be taken up by DCs or macrophages. Tumor-originated DNA activates the cGAS-STING pathway, leading to production of cytokines, recruitment of more immune cells, and maturation of antigen-presenting cells, which trigger a CD8 T cell response. Tumor-derived cGAMP is also a critical player in promoting the immune response, especially activating NK cells.75 Immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as anti-PD-L1 antibody, can unleash the power of CD8 T cells, which is otherwise counteracted by tumor cells. However, their therapeutic efficacy relies on the presence of the cGAS-STING pathway.47 Additionally, the lower level of STING expression has been shown to be associated with poor prognosis in cancer patients.76,77 In the present study, we found that the therapeutic effect of zebularine also depends on cGAS and STING from both tumor cells and host cells, indicating it has a complex impact in the tumor microenvironment. In tumor cells, zebularine, through its epigenetic effects, causes upregulation of STING mRNA and protein levels, and therefore leads to sensitization of the DNA-sensing pathway. At the same time, zebularine also caused accumulation of DNA of unknown identity (discussed below) in the cytoplasm. These two effects together may lead to generation of cGAMP in tumor cells and cytokine production, as confirmed by qRT-PCR results (Figures 5D–5F). Tumor-derived cGAMP can be transferred to host macrophages or DCs through gap junctions or phagocytosis, and therefore initiate the anti-tumor immune response.72, 73, 74 The impact of zebularine on the cGAS-STING pathway in host immune cells may not be as apparent as in tumor cells, since this pathway is usually quite robust in DCs and macrophages. However, DNA and cGAMP from tumor cells can be taken up by antigen-presenting cells and promote a series of immune responses, including production of cytokines and antigen presentation. Therefore, the intact cGAS-STING pathway in tumor is also essential for the therapeutic effect of zebularine (Figure 4).

There have been reports that other two nucleotide DNMTis, Aza and Dac, can cause cells to generate RNA species termed “viral mimicry” that engage the RIG-I-Mda5-MAVS pathway.34,36 In contrast, zebularine-induced upregulation of IFN and ISGs does not depend on MAVS (see Figure S3). Instead, we observed accumulation of cytoplasmic DNA upon prolonged zebularine treatment (Figure 3). The identity of cytoplasmic DNA remains an interesting question. Unlike Ara-C, which is also a nucleotide analog, zebularine does not cause DNA damage (Figure 3); therefore, cytoplasmic DNA in zebularine-exposed cells is not likely derived from genome instability. In an effort to distinguish whether cytosolic DNA originated from mitochondria, we failed to detect any PCR signal using primers specific for mtDNA. The other possibility is that cytoplasmic DNA is derived from endogenous retroelements through reverse transcription. Unlike Ara-c, zebularine cannot increase the expression of LINE1 (ORF1, ORF2, and the 5′ UTR) but increased the expression of endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) (see Figures S4A and S4B). In addition, zebularine and decitabine promote ERV mRNA expression in a STING-dependent manner (see Figures S4C and S4D). Therefore, our data favor ERV-derived DNA as the origin of cytosolic DNAs upon zebularine exposure. There is evidence that genetic deletion of Trex1, a DNA exonuclease that keeps cytoplasm clear of DNA, led to accumulation of DNA species that originated from retroelements.78 These DNA species can trigger an unwanted immune response and lead to autoimmune disorders. It is likely that generation of DNA from retroelements is constantly happening and is balanced by the activity of DNases such as Trex1 and DNase II. The reasons why cells have to self-counteract is not clear, but it is possible that this is a mechanism through which cells keep a tonic level of IFN response, and therefore they have advantages in fending off microbial invasions. In cancer cells, transcription of many genes, including retroelements, might be shut off by epigenetic modifications. This is likely a result of co-evolution of tumor and the immune system, as loss of tonic IFN action renders tumor cells less visible to immune surveillance.79,80 By reversing DNA methylation, zebularine promotes generation of cytoplasmic DNA from retroelements, as well as upregulation of key components of the DNA-sensing pathway such as STING, therefore restoring visibility of cancer cells by the immune system. Our current study unveils a novel therapeutic aspect of DNMTi drugs, which sensitize the cGAS-STING pathway to enhance anti-tumor immunity, and provide guidance for improving treatment regimes in the clinical settings.

Materials and methods

Mouse strains

Animal experiments were carried out with mice on the C57BL/6J background and BALB/cAJcl background. C57BL/6J and BALB/cAJcl nude mice at 6 weeks of age were purchased from Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co. (Shanghai, China). C57BL/6J-Tmem173gt/J and B6(C)-Mb21d1tm1d(EUCOMM)Hmgu/J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). In addition, we also knocked out cGAS and STING genes in the C57BL/6J background by CRISPR-Cas9 technology. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals approved by the Fujian Provincial Office for Managing Laboratory Animals and was guided by the Fujian Normal University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cell lines and culture conditions

SGC-7901, B16F10, THP1, THP1, and BJ cells were cultured in 5% CO2 and in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 media containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), L929 cells, and RAW26.7 cells were cultured in 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% FBS. AGS was cultured in 5% CO2 in DMEM-F12 containing 10% FBS. The media and FBS were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). The cell lines were obtained from the Shanghai Institute of Digestive Surgery (Shanghai, China).

AGS-STING−/−, AGS-DCK−/−, l929-Mavs−/−, B16F10-cGAS−/−, and B16F10-STING−/− cells were generated using CRISPR-Cas9 technology (see below for details). B16F10-luciferase cells were acquired by infection with lentivirus-expressing luciferase (Ubi-MCS-firefly-luciferase-IRES-puromycin). The lentivirus was kindly provided by the Fujian Cancer Hospital (Fuzhou, Fujian, China). All cell lines tested negative for mycoplasma contamination.

gDNA isolation and bisulfite sequencing analyses

gDNA was extracted by using a TaKaRa MiniBEST universal gDNA extraction kit v5.0 (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). DNA was bisulfite converted and purified using an EpiTect Plus bisulfite conversion kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The above bisulfite-treated DNA was subjected to PCR. The STING primer pair used for PCR was as follows: 5′-GTATTTTGGGAGGTTAAGGTAAATG-3′ (forward) and 5′-AATTATAAAAATAAACCACTACACCC-3′ (reverse). The PCR products were purified by a TaKaRa MiniBEST agarose gel DNA extraction kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) and then inserted into a pGEM-T easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Ten recombinant DNA clones were selected from each sample and sequenced (BioSune Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). The sequencing results were aligned with the STING gene reference sequence (NCBI: NC_000005.10) for determining cytosine methylation sites using BioEdit software, where the cytosines are highlighted in blue in the alignment results (Figure 2E).

MS-MCA

MS-MCA was performed as previously described.59 The RPRM primer pair used for PCR was as follows: 5′-GTTTTAGAAGAGTTTAGTTGTTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTACTATTAACCAAAAACAAAC-3′ (reverse). Briefly, two control plasmids containing the wild-type and fully C→T converted RPRM promoter sequences, designated as SU and SM, were used to generate the unmethylated and fully methylated melt curve peaks, respectively. The sample DNAs were treated with bisulfite and subjected to real-time PCR by using SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Tli RNase H Plus) (TaKaRa, Dalian, China), and the conditions were as follows: for the amplification stage, 95°C for 30 s and 95°C for 5 s, 56°C for 15 s, 72°C for 30 s for 40 cycles; for the melt curve stage, 95°C for 15 s and 72°C–88°C with a 0.1°C increment per cycle. The melt curve was generated and used to determine the methylation status of each sample.

RNA isolation and real-time RT-PCR

The total RNA was extracted from samples by TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The mRNA expression levels were quantified by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. The reverse transcription reaction was performed using 1 μg of total RNA with a PrimeScript RT reagent kit plus gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). The quantitative real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Tli RNase H Plus) (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) at 95°C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. The primers used for PCR are shown in Table S2. PCR was performed on an ABI Q6 Fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and the changes in expression were calculated by using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene knockout

The gRNA oligonucleotides, with sequences for their respective target genes listed in Table S3, were annealed and cloned into the vector pX459. To delete target genes, AGS and B16F10 cells were transfected with pX459 plasmids carrying the corresponding gRNAs using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) reagents, and selected with 1 μg/mL puromycin for 2 days. Cells were then transferred into fresh medium without puromycin and seeded at super-low density to allow colony formation from single cells. Colonies were then picked and expanded for gene knockout (KO) validation by sequencing of the target genomic region, immunoblot, and ELISA (see the following).

Western blot analysis and ELISA

The cells with the various treatments were washed with ice-cold PBS, harvested by gentle scraping, and lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) cell lysis buffer. The samples were separated by electrophoresis on 10% tricine-SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes for hybridization with the corresponding primary antibodies, followed by IRDye 800CW or 680 LT secondary antibodies (1:1,000) and visualized by an Odyssey CLx western blot detection system (Westburg, Leusden, the Netherlands). The expression of GAPDH was used as the endogenous control. The level of IFNβ production was measured by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s instructions accompanying a mouse IFNβ bioluminescent ELISA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and the level of cGAMP production was measured by ELISA using a 2′3′-cGAMP ELISA kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Confocal microscopy

The AGS cells were treated with DMSO, Ara-C, zebularine, and DAC for 4 days. The immunofluorescent images were taken by using an inverted LSM 780/Axio Imager confocal microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Fluorophores were sequentially excited at 488 nm to prevent cross-excitation. The images were collected, and raw data were quantified with ZEN120 imaging software.

Assay for cGAS activity and inhibition

For each reaction, a 60-μL mixture containing 20 mM Tris-Cl, 5 mM MgCl2 (pH 7.5), 0.01 mg/mL HT-DNA, 100 μM ATP, 100 μM GTP, 30 nM recombinant mouse cGAS protein, and different concentrations of zebularine was incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The reaction was stopped by heating at 95°C for 5 min, and 40 μL of Kinase-Glo (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was added. Luminescence was measured to calculate the consumption of ATP.

Tumor inoculation, treatment, and measurement

B16F10 melanoma tumor cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS. 1 × 106 B16 cells in 100 μL of PBS were subcutaneously injected into the right shoulder of female mice to establish tumors. At 7 days after tumor cell inoculation, the mice were treated with zebularine alone, cGAMP alone, or the combination of both. 2′3′-cGAMP was obtained from The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, and zebularine was synthesized in our Laboratory. A final concentration of 2.5 mg/mL zebularine was added to drinking water for 10 days until the mice were collected for conducting further experiments. A total of 100 μL of 2′3′-cGAMP in PBS at the indicated concentrations was injected into the site next to tumor. cGAMP treatment was repeated three times with 4-day intervals. Tumors were measured with a Vernier caliper, and the tumor sizes were calculated using the following formula: π/6 × length × width × height.

TIL separation and staining

For analyses of TILs, the mice were inoculated with B16F10 melanoma cells to establish tumors and treated with zebularine or cGAMP alone or both, as described above, followed by harvesting of the tumors on day 17. Tumors were minced and filtered through a 100-μm strainer to obtain single-cell suspensions. Red blood cells were further lysed with red blood cell (RBC) lysis buffer. After pelleting, cells were resuspended in 11 mL of 40% Percoll (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) in RPMI and overlaid onto 3.5 mL of 70% Percoll in a 15-mL conical tube. After centrifugation at 800 × g for 30 min, lymphocytes were collected from the gradient interface, washed with 10 mL of cold RPMI 1640, and resuspended. The lymphocytes were stained with a mixture of antibodies, including anti-mouse CD45.2-allophycocyanin (APC)-Cy7 (BD Biosciences), anti-mouse CD3-Brilliant Violet 421 (BV421) (BD Biosciences), anti-mouse CD4-peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP)-Cy5.5 (BD Biosciences), anti-mouse CD8-APC (BD Biosciences), or the other mixture of antibodies, including CD45.2-APC-Cy7 (BD Biosciences), anti-mouse CD3-BV421 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), anti-mouse NK1.1-APC (BD Biosciences), and anti-mouse CD11b-BB515 (BD Biosciences); these antibodies were either obtained from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA) or BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA). Stained cells were analyzed by BD FACSymphony (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA), and the FACS data were analyzed using the software that comes with the instrument.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were done by either the Student’s t test or two-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc test. The statistical analysis for survival curves was done by a log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. All experiments were done at least three times independently. Findings were considered significantly different when p <0.05.

Acknowledgments

This worik was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, China (grant no. 2017J01621); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31741079); the Fujian Provincial Health and Education Alliance Funds (WKJ-FJ-28); the Innovative Research Teams Program II of Fujian Normal University in China (IRTL1703); the Fujian Key Laboratories Funds; and by the Fujian Provincial Lingjun Scholarship to Q.C.. We thank the members of the Chen and Dr. Sun laboratories for technical assistance and helpful discussions.

Author contributions

Q.C. and J. Lai conceptualized and designed research; J. Lai, Y.F., S.T., S.H., X.L., L.L., X.Z., H.W., S.L., J.Z., J. Liang, Q.L., Y.Z., and J.F. performed the experiments; J. Lai, Y.F., L.D., J.Q., and R.B. established the TIL extraction method and performed flow cytometry analyses; H.Z. and Z.L. were responsible for bioinformatics analyses; D.L. synthesized zebularine; S.X. and S.C. made knockout cells and mice; and Q.C. and J. Lai analyzed data and wrote the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.02.005.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Egger G., Liang G., Aparicio A., Jones P.A. Epigenetics in human disease and prospects for epigenetic therapy. Nature. 2004;429:457–463. doi: 10.1038/nature02625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glasspool R.M., Teodoridis J.M., Brown R. Epigenetics as a mechanism driving polygenic clinical drug resistance. Br. J. Cancer. 2006;94:1087–1092. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones P.A., Baylin S.B. The epigenomics of cancer. Cell. 2007;128:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Sousa E Melo F., Colak S., Buikhuisen J., Koster J., Cameron K., de Jong J.H., Tuynman J.B., Prasetyanti P.R., Fessler E., van den Bergh S.P. Methylation of cancer-stem-cell-associated Wnt target genes predicts poor prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:476–485. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones P.A. Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012;13:484–492. doi: 10.1038/nrg3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goll M.G., Bestor T.H. Eukaryotic cytosine methyltransferases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005;74:481–514. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.010904.153721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jia D., Jurkowska R.Z., Zhang X., Jeltsch A., Cheng X. Structure of Dnmt3a bound to Dnmt3L suggests a model for de novo DNA methylation. Nature. 2007;449:248–251. doi: 10.1038/nature06146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Segura-Pacheco B., Perez-Cardenas E., Taja-Chayeb L., Chavez-Blanco A., Revilla-Vazquez A., Benitez-Bribiesca L., Duenas-González A. Global DNA hypermethylation-associated cancer chemotherapy resistance and its reversion with the demethylating agent hydralazine. J. Transl. Med. 2006;4:32. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-4-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gore S.D., Jones C., Kirkpatrick P. Decitabine. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006;5:891–892. doi: 10.1038/nrd2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ewald B., Sampath D., Plunkett W. Nucleoside analogs: molecular mechanisms signaling cell death. Oncogene. 2008;27:6522–6537. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Issa J.P.J., Kantarjian H.M., Kirkpatrick P. Azacitidine. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005;4:275–276. doi: 10.1038/nrd1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soengas M.S., Capodieci P., Polsky D., Mora J., Esteller M., Opitz-Araya X., McCombie R., Herman J.G., Gerald W.L., Lazebnik Y.A. Inactivation of the apoptosis effector Apaf-1 in malignant melanoma. Nature. 2001;409:207–211. doi: 10.1038/35051606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qiu Y.Y., Mirkin B.L., Dwivedi R.S. Inhibition of DNA methyltransferase reverses cisplatin induced drug resistance in murine neuroblastoma cells. Cancer Detect. Prev. 2005;29:456–463. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scartozzi M., Bearzi I., Mandolesi A., Giampieri R., Faloppi L., Galizia E., Loupakis F., Zaniboni A., Zorzi F., Biscotti T. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene promoter methylation and cetuximab treatment in colorectal cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer. 2011;104:1786–1790. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu L., Chen L., Wu X., Li X., Song Y., Mei Q., Nie J., Han W. Low-dose DNA-demethylating agent enhances the chemosensitivity of cancer cells by targeting cancer stem cells via the upregulation of microRNA-497. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2016;142:1431–1439. doi: 10.1007/s00432-016-2157-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linnekamp J.F., Butter R., Spijker R., Medema J.P., van Laarhoven H.W.M. Clinical and biological effects of demethylating agents on solid tumours—a systematic review. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2017;54:10–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juergens R.A., Wrangle J., Vendetti F.P., Murphy S.C., Zhao M., Coleman B., Sebree R., Rodgers K., Hooker C.M., Franco N. Combination epigenetic therapy has efficacy in patients with refractory advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:598–607. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fandy T.E., Herman J.G., Kerns P., Jiemjit A., Sugar E.A., Choi S.-H., Yang A.S., Aucott T., Dauses T., Odchimar-Reissig R. Early epigenetic changes and DNA damage do not predict clinical response in an overlapping schedule of 5-azacytidine and entinostat in patients with myeloid malignancies. Blood. 2009;114:2764–2773. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-203547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matei D., Fang F., Shen C., Schilder J., Arnold A., Zeng Y., Berry W.A., Huang T., Nephew K.P. Epigenetic resensitization to platinum in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2197–2205. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang X., Han H., De Carvalho D.D., Lay F.D., Jones P.A., Liang G. Gene body methylation can alter gene expression and is a therapeutic target in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:577–590. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahuja N., Easwaran H., Baylin S.B. Harnessing the potential of epigenetic therapy to target solid tumors. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124:56–63. doi: 10.1172/JCI69736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fang F., Balch C., Schilder J., Breen T., Zhang S., Shen C., Li L., Kulesavage C., Snyder A.J., Nephew K.P., Matei D.E. A phase 1 and pharmacodynamic study of decitabine in combination with carboplatin in patients with recurrent, platinum-resistant, epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:4043–4053. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Treppendahl M.B., Kristensen L.S., Grønbæk K. Predicting response to epigenetic therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124:47–55. doi: 10.1172/JCI69737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baylin S.B., Jones P.A. A decade of exploring the cancer epigenome—biological and translational implications. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2011;11:726–734. doi: 10.1038/nrc3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wrangle J., Wang W., Koch A., Easwaran H., Mohammad H.P., Vendetti F., Vancriekinge W., Demeyer T., Du Z., Parsana P. Alterations of immune response of non-small cell lung cancer with azacytidine. Oncotarget. 2013;4:2067–2079. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramakrishnan S., Hu Q., Krishnan N., Wang D., Smit E., Granger V., Rak M., Attwood K., Johnson C., Morrison C. Decitabine, a DNA-demethylating agent, promotes differentiation via NOTCH1 signaling and alters immune-related pathways in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:3217. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0024-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li H., Chiappinelli K.B., Guzzetta A.A., Easwaran H., Yen R.W.C., Vatapalli R., Topper M.J., Luo J., Connolly R.M., Azad N.S. Immune regulation by low doses of the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor 5-azacitidine in common human epithelial cancers. Oncotarget. 2014;5:587–598. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karpf A.R., Peterson P.W., Rawlins J.T., Dalley B.K., Yang Q., Albertsen H., Jones D.A. Inhibition of DNA methyltransferase stimulates the expression of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1, 2, and 3 genes in colon tumor cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:14007–14012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fan H., Lu X., Wang X., Liu Y., Guo B., Zhang Y., Zhang W., Nie J., Feng K., Chen M. Low-dose decitabine-based chemoimmunotherapy for patients with refractory advanced solid tumors: a phase I/II report. J. Immunol. Res. 2014;2014:371087. doi: 10.1155/2014/371087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plimack E.R., Desai J.R., Issa J.P., Jelinek J., Sharma P., Vence L.M., Bassett R.L., Ilagan J.L., Papadopoulos N.E., Hwu W.-J. A phase I study of decitabine with pegylated interferon α-2b in advanced melanoma: impact on DNA methylation and lymphocyte populations. Invest. New Drugs. 2014;32:969–975. doi: 10.1007/s10637-014-0115-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gollob J.A., Sciambi C.J., Peterson B.L., Richmond T., Thoreson M., Moran K., Dressman H.K., Jelinek J., Issa J.-P.J. Phase I trial of sequential low-dose 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine plus high-dose intravenous bolus interleukin-2 in patients with melanoma or renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006;12:4619–4627. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klar A.S., Gopinadh J., Kleber S., Wadle A., Renner C. Treatment with 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine induces expression of NY-ESO-1 and facilitates cytotoxic T lymphocyte-mediated tumor cell killing. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0139221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo N., Nixon M.J., Gonzalez-Ericsson P.I., Sanchez V., Opalenik S.R., Li H., Zahnow C.A., Nickels M.L., Liu F., Tantawy M.N. DNA methyltransferase inhibition upregulates MHC-I to potentiate cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses in breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:248. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02630-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roulois D., Loo Yau H., Singhania R., Wang Y., Danesh A., Shen S.Y., Han H., Liang G., Jones P.A., Pugh T.J. DNA-demethylating agents target colorectal cancer cells by inducing viral mimicry by endogenous transcripts. Cell. 2015;162:961–973. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peng D., Kryczek I., Nagarsheth N., Zhao L., Wei S., Wang W., Sun Y., Zhao E., Vatan L., Szeliga W. Epigenetic silencing of TH1-type chemokines shapes tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nature. 2015;527:249–253. doi: 10.1038/nature15520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chiappinelli K.B., Strissel P.L., Desrichard A., Li H., Henke C., Akman B., Hein A., Rote N.S., Cope L.M., Snyder A. Inhibiting DNA methylation causes an interferon response in cancer via dsRNA including endogenous retroviruses. Cell. 2017;169:361. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richardson B. Effect of an inhibitor of DNA methylation on T cells. II. 5-Azacytidine induces self-reactivity in antigen-specific T4+ cells. Hum. Immunol. 1986;17:456–470. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(86)90304-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cornacchia E., Golbus J., Maybaum J., Strahler J., Hanash S., Richardson B. Hydralazine and procainamide inhibit T cell DNA methylation and induce autoreactivity. J. Immunol. 1988;140:2197–2200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Youngblood B., Oestreich K.J., Ha S.-J., Duraiswamy J., Akondy R.S., West E.E., Wei Z., Lu P., Austin J.W., Riley J.L. Chronic virus infection enforces demethylation of the locus that encodes PD-1 in antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. Immunity. 2011;35:400–412. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stone M.L., Chiappinelli K.B., Li H., Murphy L.M., Travers M.E., Topper M.J., Mathios D., Lim M., Shih I.-M., Wang T.-L. Epigenetic therapy activates type I interferon signaling in murine ovarian cancer to reduce immunosuppression and tumor burden. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E10981–E10990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1712514114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang L., Amoozgar Z., Huang J., Saleh M.H., Xing D., Orsulic S., Goldberg M.S. Decitabine enhances lymphocyte migration and function and synergizes with CTLA-4 blockade in a murine ovarian cancer model. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2015;3:1030–1041. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mazzone R., Zwergel C., Mai A., Valente S. Epi-drugs in combination with immunotherapy: a new avenue to improve anticancer efficacy. Clin. Epigenetics. 2017;9:59. doi: 10.1186/s13148-017-0358-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu J., Sun L., Chen X., Du F., Shi H., Chen C., Chen Z.J. Cyclic GMP-AMP is an endogenous second messenger in innate immune signaling by cytosolic DNA. Science. 2013;339:826–830. doi: 10.1126/science.1229963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun L., Wu J., Du F., Chen X., Chen Z.J. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science. 2013;339:786–791. doi: 10.1126/science.1232458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen Q., Sun L., Chen Z.J. Regulation and function of the cGAS-STING pathway of cytosolic DNA sensing. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17:1142–1149. doi: 10.1038/ni.3558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ablasser A., Chen Z.J. cGAS in action: expanding roles in immunity and inflammation. Science. 2019;363:eaat8657. doi: 10.1126/science.aat8657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang H., Hu S., Chen X., Shi H., Chen C., Sun L., Chen Z.J. cGAS is essential for the antitumor effect of immune checkpoint blockade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:1637–1642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1621363114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chabanon R.M., Muirhead G., Krastev D.B., Adam J., Morel D., Garrido M., Lamb A., Hénon C., Dorvault N., Rouanne M. PARP inhibition enhances tumor cell-intrinsic immunity in ERCC1-deficient non-small cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 2019;129:1211–1228. doi: 10.1172/JCI123319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sen T., Rodriguez B.L., Chen L., Corte C.M.D., Morikawa N., Fujimoto J., Cristea S., Nguyen T., Diao L., Li L. Targeting DNA damage response promotes antitumor immunity through STING-mediated T-cell activation in small cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2019;9:646–661. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu X., Pu Y., Cron K., Deng L., Kline J., Frazier W.A., Xu H., Peng H., Fu Y.-X., Xu M.M. CD47 blockade triggers T cell-mediated destruction of immunogenic tumors. Nat. Med. 2015;21:1209–1215. doi: 10.1038/nm.3931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Corrales L., Glickman L.H., McWhirter S.M., Kanne D.B., Sivick K.E., Katibah G.E., Woo S.-R., Lemmens E., Banda T., Leong J.J. Direct activation of STING in the tumor microenvironment leads to potent and systemic tumor regression and immunity. Cell Rep. 2015;11:1018–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Demaria O., De Gassart A., Coso S., Gestermann N., Di Domizio J., Flatz L., Gaide O., Michielin O., Hwu P., Petrova T.V. STING activation of tumor endothelial cells initiates spontaneous and therapeutic antitumor immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:15408–15413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512832112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woo S.-R., Fuertes M.B., Corrales L., Spranger S., Furdyna M.J., Leung M.Y., Duggan R., Wang Y., Barber G.N., Fitzgerald K.A. STING-dependent cytosolic DNA sensing mediates innate immune recognition of immunogenic tumors. Immunity. 2014;41:830–842. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Deng L., Liang H., Xu M., Yang X., Burnette B., Arina A., Li X.-D., Mauceri H., Beckett M., Darga T. STING-dependent cytosolic DNA sensing promotes radiation-induced type I interferon-dependent antitumor immunity in immunogenic tumors. Immunity. 2014;41:843–852. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cheng J.C., Weisenberger D.J., Gonzales F.A., Liang G., Xu G.-L., Hu Y.-G., Marquez V.E., Jones P.A. Continuous zebularine treatment effectively sustains demethylation in human bladder cancer cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:1270–1278. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.1270-1278.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakamura K., Nakabayashi K., Htet Aung K., Aizawa K., Hori N., Yamauchi J., Hata K., Tanoue A. DNA methyltransferase inhibitor zebularine induces human cholangiocarcinoma cell death through alteration of DNA methylation status. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0120545. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Geutjes E.J., Tian S., Roepman P., Bernards R. Deoxycytidine kinase is overexpressed in poor outcome breast cancer and determines responsiveness to nucleoside analogs. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012;131:809–818. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1477-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tang K., Zhang Z., Bai Z., Ma X., Guo W., Wang Y. Enhancement of gemcitabine sensitivity in pancreatic cancer by co-regulation of dCK and p8 expression. Oncol. Rep. 2011;25:963–970. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang H., Zheng Y., Lai J., Luo Q., Ke H., Chen Q. Methylation-sensitive melt curve analysis of the reprimo gene methylation in gastric cancer. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0168635. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Latif R., Lau Z., Cheung P., Felsenfeld D.P., Davies T.F. The “TSH receptor glo assay”—a high-throughput detection system for thyroid stimulation. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2016;7:3. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2016.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Crasta K., Ganem N.J., Dagher R., Lantermann A.B., Ivanova E.V., Pan Y., Nezi L., Protopopov A., Chowdhury D., Pellman D. DNA breaks and chromosome pulverization from errors in mitosis. Nature. 2012;482:53–58. doi: 10.1038/nature10802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang H., Wang H., Ren J., Chen Q., Chen Z.J. cGAS is essential for cellular senescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E4612–E4620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1705499114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mackenzie K.J., Carroll P., Martin C.A., Murina O., Fluteau A., Simpson D.J., Olova N., Sutcliffe H., Rainger J.K., Leitch A. cGAS surveillance of micronuclei links genome instability to innate immunity. Nature. 2017;548:461–465. doi: 10.1038/nature23449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yum S., Li M., Frankel A.E., Chen Z.J. Roles of the cGAS-STING pathway in cancer immunosurveillance and immunotherapy. Annu. Rev. Cancer Biol. 2019;3:323–344. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dunn G.P., Bruce A.T., Sheehan K.C., Shankaran V., Uppaluri R., Bui J.D., Diamond M.S., Koebel C.M., Arthur C., White J.M., Schreiber R.D. A critical function for type I interferons in cancer immunoediting. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:722–729. doi: 10.1038/ni1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moschos S., Varanasi S., Kirkwood J.M. Interferons in the treatment of solid tumors. Cancer Treat. Res. 2005;126:207–241. doi: 10.1007/0-387-24361-5_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xu H.C., Grusdat M., Pandyra A.A., Polz R., Huang J., Sharma P., Deenen R., Köhrer K., Rahbar R., Diefenbach A. Type I interferon protects antiviral CD8+ T cells from NK cell cytotoxicity. Immunity. 2014;40:949–960. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Crouse J., Bedenikovic G., Wiesel M., Ibberson M., Xenarios I., Von Laer D., Kalinke U., Vivier E., Jonjic S., Oxenius A. Type I interferons protect T cells against NK cell attack mediated by the activating receptor NCR1. Immunity. 2014;40:961–973. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Novikov A., Cardone M., Thompson R., Shenderov K., Kirschman K.D., Mayer-Barber K.D., Myers T.G., Rabin R.L., Trinchieri G., Sher A., Feng C.G. Mycobacterium tuberculosis triggers host type I IFN signaling to regulate IL-1β production in human macrophages. J. Immunol. 2011;187:2540–2547. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bose D. cGAS/STING pathway in cancer: Jekyll and Hyde story of cancer immune response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:2456. doi: 10.3390/ijms18112456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ng K.W., Marshall E.A., Bell J.C., Lam W.L. cGAS–STING and cancer: dichotomous roles in tumor immunity and development. Trends Immunol. 2018;39:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2017.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ahn J., Xia T., Rabasa Capote A., Betancourt D., Barber G.N. Extrinsic phagocyte-dependent STING signaling dictates the immunogenicity of dying cells. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:862–873.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schadt L., Sparano C., Schweiger N.A., Silina K., Cecconi V., Lucchiari G., Yagita H., Guggisberg E., Saba S., Nascakova Z. Cancer-cell-intrinsic cGAS expression mediates tumor immunogenicity. Cell Rep. 2019;29:1236–1248.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pépin G., De Nardo D., Rootes C.L., Ullah T.R., Al-Asmari S.S., Balka K.R., Li H.M., Quinn K.M., Moghaddas F., Chappaz S. Connexin-dependent transfer of cGAMP to phagocytes modulates antiviral responses. MBio. 2020;11:e03187-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.03187-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Marcus A., Mao A.J., Lensink-Vasan M., Wang L., Vance R.E., Raulet D.H. Tumor-derived cGAMP triggers a STING-mediated interferon response in non-tumor cells to activate the NK cell response. Immunity. 2018;49:754–763.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Song S., Peng P., Tang Z., Zhao J., Wu W., Li H., Shao M., Li L., Yang C., Duan F. Decreased expression of STING predicts poor prognosis in patients with gastric cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:39858. doi: 10.1038/srep39858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bu Y., Liu F., Jia Q.-A., Yu S.-N. Decreased expression of TMEM173 predicts poor prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0165681. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stetson D.B., Ko J.S., Heidmann T., Medzhitov R. Trex1 prevents cell-intrinsic initiation of autoimmunity. Cell. 2008;134:587–598. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Xia T., Konno H., Ahn J., Barber G.N. Deregulation of STING signaling in colorectal carcinoma constrains DNA damage responses and correlates with tumorigenesis. Cell Rep. 2016;14:282–297. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sokolowska O., Nowis D. STING signaling in cancer cells: important or not? Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. (Warsz.) 2018;66:125–132. doi: 10.1007/s00005-017-0481-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.