Abstract

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are the most common bacterial infections requiring medical attention and a leading justification for antibiotic prescription. Trimethoprim is prescribed empirically for uncomplicated cases. UTIs are primarily caused by extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) and ExPEC strains play a central role in disseminating antimicrobial-resistance genes worldwide. Here, we describe the whole-genome sequences of trimethoprim-resistant ExPEC and/or ExPEC from recurrent UTIs (67 in total) from patients attending a regional Australian hospital from 2006 to 2008. Twenty-three sequence types (STs) were observed, with ST131 predominating (28 %), then ST69 and ST73 (both 7 %). Co-occurrence of trimethoprim-resistance genes with genes conferring resistance to extended-spectrum β-lactams, heavy metals and quaternary ammonium ions was a feature of the ExPEC described here. Seven trimethoprim-resistance genes were identified, most commonly dfrA17 (38 %) and dfrA12 (18 %). An uncommon dfrB4 variant was also observed. Two blaCTX-M variants were identified – blaCTX-M-15 (16 %) and blaCTX-M-14 (10 %). The former was always associated with dfrA12, the latter with dfrA17, and all blaCTX-M genes co-occurred with chromate-resistance gene chrA. Eighteen class 1 integron structures were characterized, and chrA featured in eight structures; dfrA genes featured in seventeen. ST131 H30Rx isolates possessed distinct antimicrobial gene profiles comprising aac(3)-IIa, aac(6)-Ib-cr, aph(3′)-Ia, aadA2, blaCTX-M-15, blaOXA-1 and dfrA12. The most common virulence-associated genes (VAGs) were fimH, fyuA, irp2 and sitA (all 91 %). Virulence profile clustering showed ST131 H30 isolates carried similar VAGs to ST73, ST405, ST550 and ST1193 isolates. The sole ST131 H27 isolate carried molecular predictors of enteroaggregative E. coli /ExPEC hybrid strains (aatA, aggR, fyuA). Seven isolates (10 %) carried VAGs suggesting ColV plasmid carriage. Finally, SNP analysis of serial UTI patients experiencing worsening sequelae demonstrated a high proportion of point mutations in virulence factors.

Keywords: antimicrobial resistance, class 1 integrons, extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli, hospital, ST131, urinary tract infection

Data Summary

The 67 draft genomes from the whole-genome sequencing described here have been submitted to the National Center for Biotechnology Information with the accession numbers SAMN14547713 to SAMN14547779, under BioProject PRJNA623470.

Impact Statement.

Extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) that cause urinary tract infections (UTIs) represent a significant disease burden and contribute greatly to the spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), both in Australia and worldwide. While whole-genome sequencing (WGS) provides the most precise means to track resistance and virulence mechanics, to date genomic analyses on UTI-associated ExPEC within Australian hospitals has been limited, particularly for those hospitals situated in regional and remote areas. In this study, ExPEC isolates were taken from patients suffering from cystitis, pyelonephritis and urosepsis attending a Western New South Wales Hospital between 2006 and 2008. We used WGS to investigate diversity, virulence, class 1 integron and AMR gene carriage, and SNPs that occurred in multiple isolates derived from the same patients. By doing so, we provide a baseline for future studies tracking the evolution of ExPEC AMR and virulence potential in Australian UTI-associated ExPEC populations, and particularly the evolution of ExPEC resistant to first-line UTI treatment. This work adds to the national picture of ExPEC, and additionally provides hospital-specific information that may inform future policy making and practices.

Introduction

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are the most common bacterial infections to require medical attention and incur an estimated economic burden of ~$2 billion per annum (£1.51 billion; $1=£0.76) in the USA alone [1]. In the UK, in 2013–2014, the National Health Service spent £434 million in treating 184 000 patients with unplanned admissions relating to UTIs [2]. In Australia, UTIs caused 69 823 hospitalizations in 2017–2018, resulting in 234 455 inpatient days and treatment costs as high as $AU6400 (£3500) per patient [3, 4]. Additionally, UTIs are the leading rationale behind antibiotic prescription by general practitioners [5].

The most common aetiological agent of UTIs are extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC), responsible for ~75–95 % of cases [6]. Epidemiological studies utilizing multilocus sequence typing (MLST) indicate that certain pandemic sequence types (STs) account for more than 50 % of all ExPEC infections worldwide. These ExPEC lineages are ST131, ST69 (also known as ‘clonal group A’), ST10, ST405, ST38, ST95, ST73 and ST127 [7, 8].

ExPEC can enter the intestinal tract via contact with poultry, companion animals, the environment and through sexual contact [9]. Additionally, travellers are at higher risk of ingesting ExPEC strains [10]. The subsequent introduction of ExPEC into the urinary tract via the urethra can occur due to host behaviours, physiological abnormalities or medical interventions, such as catheterization [6]. After contaminating the urethra, ExPEC can ascend to infect the bladder (cystitis), the kidney (pyelonephritis) or enter the bloodstream (urosepsis) with potentially dire outcomes as ExPEC-associated sepsis has a mortality rate of up to 30 % [11]. Indeed, each year at least 1.7 million adults in the USA develop sepsis, and 1 in 3 patients who die in hospital have sepsis [12, 13].

ExPEC possess an array of virulence-associated genes (VAGs) that enable ascension, colonization and persistence within a hostile and nutrient-deficient environment. These VAGs – commonly located on chromosomal pathogenicity islands (PAIs) or encoded on virulence plasmids – include uroepithelial adhesins, such as P-fimbriae (pap genes), S-fimbriae (sfa genes), F1C-fimbriae (foc genes), and Dr adhesins (dra genes, afa genes), toxins including secreted autotransporter toxin (sat) and cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 (cnf1), capsule (kpsM II), and several iron-acquisition systems, such as aerobactin (iuc genes, iutA), salmochellin (iro genes) and yersiniabactin (ybt genes, irp1, irp2, fyuA) [14, 15]. ExPEC have also been associated with a greater abundance of bacteriocins, toxins that inhibit the growth of other E. coli [16]. These bacteriocins are frequently carried on virulence plasmids, such as ColV plasmids [17]. While no singular VAG can be attributed to ExPEC pathogenesis, a molecular definition of ExPEC has been proposed as being E. coli that contain at least two of the following VAGs: papA and/or papC, sfa/foc, afa/draBC, kpsM II and iutA [18]. Furthermore, the presence of certain VAGs have been associated with specific uro-clinical syndromes, such as P- and S-fimbriae, Dr adhesins, and the invasin ibeA with pyelonephritis [6], and yersiniabactin irp2 and fyuA with sepsis [19]. FyuA is also directly linked to ExPEC biofilm formation in human urine [20], as is the salmochelin receptor iroN [21].

In Australia, severe pyelonephritis and sepsis are typically treated with intravenous gentamicin and amoxicillin, while cystitis is typically treated empirically with either nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim [22]. However, a 5 year study on antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in urinary E. coli from an Australian metropolitan hospital found significant increases in trimethoprim, nitrofurantoin, amoxicillin and gentamicin resistance, as well as significant extended-spectrum β-lactam resistance [23]. ExPEC, particularly ST131 strains, have been central to a worldwide increase in extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing E. coli . The ST131 lineage consists of three major clades, each of which is strongly associated with specific fimH alleles. Strains from clade C typically carry fimH30 and are currently the most prominent subtype identified in human infections [24]. Clade C is further divided into two subclades – C1 and C2. C1 mostly comprises strains with gyrA and parC SNPs conferring fluoroquinolone resistance, designated H30R, while the latter consists of strains with both fluoroquinolone resistance SNPs and carriage of plasmid-associated blaCTX-M genes, designated H30Rx [25–27]. E. coli ST131 first emerged in the literature in the early 2000s and has been linked to a 300 % increase in USA hospital admissions due to ESBL-producing E. coli in the following decade [28, 29]. The global rapid increase in ESBL-producing E. coli has had serious knock-on effects, driving carbapenem prescription and in turn promoting the spread of potentially untreatable carbapenemase-producing E. coli [30].

Like all E. coli , ExPEC have highly flexible genomes and a proclivity to capture and disseminate genes through horizontal gene transfer [31]. Horizontal gene transfer can occur via plasmid conjugation, phage transduction and via small mobile genetic elements (MGEs), such as transposons, insertion sequences (IS) and integrons, allowing for inter- and intra-species movement of genetic information [32]. As observed with the global dissemination of blaCTX-M, a single MGE capture event can have worldwide repercussions [30].

AMR surveillance of ExPEC populations within high selective pressure environments, such as hospitals, could provide meaningful insights and inform future policy making and practices. In addition to the aforementioned 5 year study on AMR within ExPEC isolated in an Australian hospital, a recent Australian government report also stated that E. coli resistances to ESBLs and fluoroquinolones are climbing [4]. While these reports highlight national trends, they tend to focus on hospitals situated in metropolitan areas, while more remote and rural areas get neglected. Furthermore, genomic surveillance of antimicrobial genes (ARGs) and VAGs within Australian hospital E. coli populations is currently limited.

Here, we used whole-genome sequencing (WGS) to characterize 67 ExPEC strains from patients with UTIs collected in a large Western New South Wales (NSW) hospital catering to regional, remote and rural Australian communities. The genomes were typed using Clermont phylogrouping, e-serotyping and MLST, and screened for the presence of ARGs, VAGs, PAIs and plasmid replicons, and several AMR associated class 1 and class 2 integrons found in this collection were characterized. Furthermore, isolates from recurrent infections, including those with a subsequently more severe clinical sequelae, were interrogated for SNPs leading to point mutations.

Methods

Sample collection and selection criteria for WGS

Urine specimens were collected by clinical staff members of participating health-care centres using a standardized protocol. Semi-quantitative culture was performed on horse blood, MacConkey and chromogenic agars, followed by conventional identification. Isolates were stored in 5 0% (v/v) glycerol in trypticase soy broth at −70 °C.

Phenotypic resistance testing

The isolates were tested for susceptibility to 14 antibiotics as per the disc diffusion method specified by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [33], using Neo-Sensitabs discs (Rosco). The antibiotics tested were (disc content) amikacin (30 µg), amoxicillin–clavulanate (60 µg), ampicillin (25 µg), ceftazidime (30 µg), ceftriaxone (30 µg), cephalothin (30 µg), ciprofloxacin (10 µg), gentamicin (10 µg), imipenem (10 µg), nalidixic acid (30 µg), nitrofurantoin (300 µg), norfloxacin (10 µg), tetracycline (30 µg) and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (5 µg). The double-disc diffusion test was used to detect the production of ESBLs [34].

DNA isolation and WGS

DNA extraction and WGS were performed as described previously [35]. Briefly, DNA was extracted using the ISOLATE II genomic DNA kit (Bioline) and stored at −20 °C. Short-read sequencing was performed using an Illumina HiSeq 2500 v4 sequencer in rapid PE150 mode.

Genome assemblies

Raw reads were used to assemble draft genome sequences via Shovill software using default settings (https://github.com/tseemann/shovill). Assemblies underwent quality control using assembly-stats software (https://github.com/sanger-pathogens/assembly-stats). Assembly statistics for this collection are available in Data S1 (available with the online version of this article).

Phylogenetic analysis

A maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of this collection was reconstructed using iq-tree 2 (http://www.iqtree.org/) [36] and a SNP-based phylogenetic tree was reconstructed using snplord (https://github.com/maxlcummins/pipelord/snplord/tree/master/snplord), an automated pipeline that utilizes snippy (https://github.com/tseemann/snippy), Gubbins [37] (https://github.com/sanger-pathogens/gubbins) and SNP-sites (https://github. com/sanger-pathogens/snp-sites). The SNP-based tree of the entire collection was built using 76.0 % (3 525 942 bp/4 639 675 bp) of the reference genome K12 MG1655 (GCA_000005845.2) and consisted of 35 038 SNPs (141 270 SNPs before recombination filtering). Trimethoprim-sensitive ExPEC isolates ERR434278, ERR434751, ERR434270, ERR434273 and ERR434271 [38], and trimethoprim-sensitive enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) isolates SRR5470250, SRR5024242 and SRR3574247 [39], all representing the major STs in this collection, were added to both the phylogenetic analysis and gene screening as controls. An additional SNP-based ST131 only tree was built using 92.03 % (4 831 235 bp/5 249 449 bp) of reference genome ST131 EC958 (GCA_000285655.3) to identify SNP sites. Recombination filtering reduced 7460 SNPs to 386 SNPs. The ST131 SNP-based tree was reconstructed using iq-tree 2 and a recombination filtered alignment of 478 bp produced by Gubbins. All trees were visualized using the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v4 online-based software [40] (https://itol.embl.de/). The ExPEC pangenome was calculated using Roary v3.11.2 [41] and visualized using Phandango [42]. Clonal samples from serial patients were removed from this analysis (total of 57 isolates used) to prevent deflation of the core genome.

Serial patient SNP analysis

The snplord pipeline was run on isolates originating from a single patient using the isolate with the earliest isolation date as a reference in each instance. SNPs called by this pipeline were checked manually in .gbk files generated by Prokka [43] using SnapGene. Gubbins output was used to determine which SNPs were the result of homologous recombination.

Gene screening

Isolate STs, serogroups and phylogroups were determined in silico using MLST v2.0 [44] (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/MLST/), SerotypeFinder v2.0 [45] (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SerotypeFinder/) and ClermontTyping [46] (http://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk/), respectively. ST131 isolates additionally underwent FimH typing using FimTyper [47] (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/FimTyper/). The ariba read-mapping tool [48] was used the screen for ARGs, plasmid replicons and VAGs using the following reference databases: ResFinder [49] (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ResFinder/), PlasmidFinder [50] (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/PlasmidFinder/) and VirulenceFinder [51] (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/VirulenceFinder/). However, as VirulenceFinder screens for only one papA allele, an additional blastn search was also performed using 14 papA alleles [52]. An additional custom database with AMR-associated ISs, class 1 and 2 integrases, and additional ExPEC-associated VAGs was also utilized and can be accessed at https://github.com/CJREID/custom_DBs. ariba data were processed using a bespoke script accessible at https://github.com/maxlcummins/pipelord/tree/master/aribalord and visualized using the following R packages: ggplot2 v3.3.0 (https://github.com/tidyverse/ggplot2) and ggtree v2.2.1 [53] (https://github.com/YuLab-SMU/ggtree).

To infer ColV plasmid and PAI carriage, short reads from each isolate were mapped to the ColV reference plasmid pCERC4 (KU578032), PAI ICFT073 (AE014075.1, start 3 406 225 bp, end 3 469 205 bp), PAI II536 (AJ494981), PAI III536 (AF301153) and PAI IV526/HPI (high pathogenicity island) using the Burrows–Wheeler Aligner (bwa) v0.7.17 [54] and converted to bam file format using SAMtools v0.1.18 [55]. A bespoke script, available at https://github.com/maxlcummins/pipelord/tree/master/plasmidlord, was used to produce a histogram of read-depth as a function of reference coordinate and clustered based on their Euclidean distances, and used to generate a heatmap.

blastn [56] was used to determine whether integrons characterized in this collection are present in other genomes available in public databases, and associated metadata were pulled from GenBank [56] and Enterobase [57]. Integron B structure comparison was achieved using EasyFig [58]. All gene schematics were generated using SnapGene (www.snapgene.com/).

Statistical analysis

R software v4.0.2 was used for the reconstruction of correlation heat maps and classical (metric) multidimensional scaling (MDS) analysis, using the ggplot2 v3.3.0 (https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/) package for visualization, and the ggcorrplot v0.1.3 (https://github.com/kassambara/ggcorrplot) package for correlation calculation. Two MDS analyses were performed, one for identified virulence genes and one for AMR genes, using the standard R package functions dist and cmdscale in conjunction with a presence/absence matrix (with one for presence and zero for absence).

Results and Discussion

Genomic surveillance using WGS can provide high-resolution data on ARG presence, persistence, evolution and potential for horizontal transfer [59], as well as inform on population diversity and VAG carriage, and provide in-depth analyses of SNP-mediated mutations. Yet to date, genomic analyses on UTI-associated ExPEC within Australian hospitals has been limited. Here, we provide a retrospective WGS study on ExPEC resistant to first-line trimethoprim treatment and/or isolates collected from serial UTIs between 2006 to 2008 from a regional hospital in Western NSW, Australia. We aimed to provide a baseline for future studies tracking the evolution of ExPEC AMR and virulence potential in Australian UTI-associated ExPEC populations by reporting on ARG, VAG and MGE carriage, characterizing 18 class 1 integrons structures identified in this collection and identifying SNPs occurring in recurrent UTI isolates.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

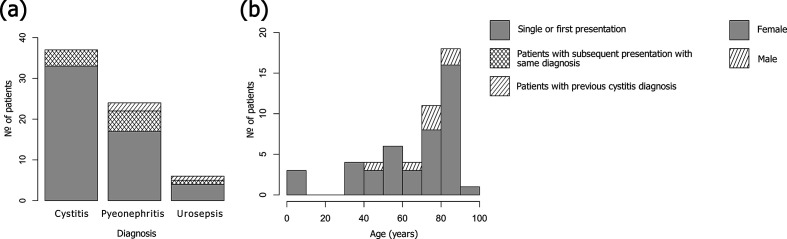

From clinical samples collected between 2006 and 2008, 76 isolates were selected for genome sequencing due to phenotypic trimethoprim resistance and/or originating from a serial UTI patient. After quality-control measures, the final collection comprised 67 E. coli draft genomes (mean contig size of 23 477 bp, with a mean number of contigs of 234) originating from 37 samples taken from patients with cystitis (55 %), 23 samples from patients with pyelonephritis (34 %) and 7 samples from patients with urosepsis (10 %) (Fig. 1a). Recurrent UTIs are common, particularly in women, with 27 % reporting a recurrence within 6 months [53]. In this collection, 12 out of 51 patients were sampled more than once due to multiple, or ongoing, UTIs during the study period.

Fig. 1.

Sample population and clinical characteristics. (a) Diagnoses of patients presenting with UTIs over the study period. For the patients with multiple samples taken for the same diagnosis (cross-hatched stripes): for cystitis, the mean number of days between collections was 126 days; for pyelonephritis, 63 days; and for urosepsis, 68 days. For patients with a previous cystitis diagnosis and subsequent pyelonephritis or urosepsis diagnoses (sloped stripes): the mean length between collections was 174 days, and 181 days for urosepsis (n=1). (b) Age and biological sex of patients. Females are represented by grey, males by shading.

Women are more likely to contract UTIs than men at a ratio of 8:1, and one in three women will experience at least one UTI necessitating antibiotics by age 24 [60]. The risk of UTIs tends to increase with age in both sexes [61]; however, the prevalence of UTIs in women over the age of 65 is double that of the overall population [62]. This collection is reflective of UTI epidemiology with more isolates derived from female patients (44 vs 7; 86 vs 14 %) and with patients’ ages ranging from 13 months to 91 years, the majority (64 %) being above 66 years. The mean age for female patients was 66 years, and 74 years for male patients (Fig. 1b). No patient was identified as pregnant.

Phylogenetic analysis

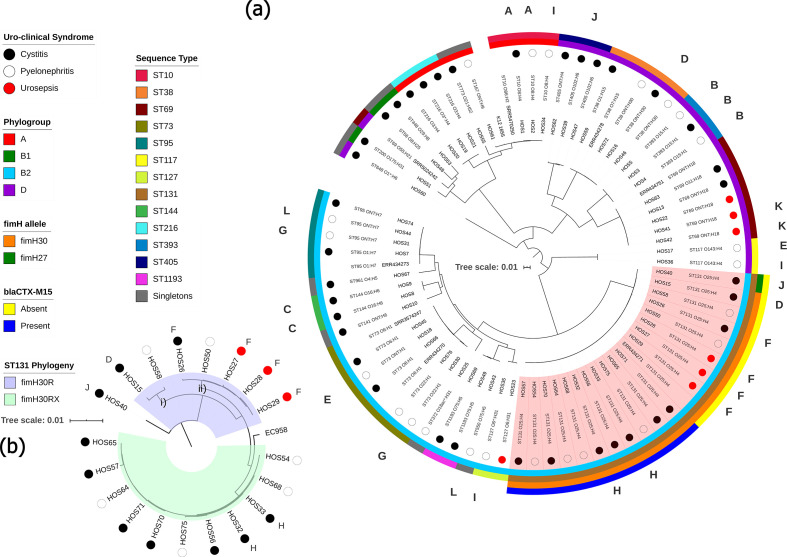

While ExPEC are phylogenetically diverse, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 217 studies flagged a handful of globally dominant STs, the most prominent being ST131 (phylogroup B2), followed by ST69 (D), ST10 (A), ST405 (D), ST38 (D), ST95 (B2), ST648 (D) and ST73 (B2) [7]. Consequently, B2 and D constitute the phylogroups most frequently associated with ExPEC infections. To ascertain the evolutionary relationships between samples in this collection, a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was reconstructed using the complete genome of E. coli strain K12-MG1655 as a reference (Fig. 2a). The tree demonstrates clear clustering based on phylogroup and ST (Fig. 2a). The collection comprised 23 STs, and despite selecting for trimethoprim resistance, the collection followed global trends with ST131 (O25:H4) being the most common (n=19; 28 %), followed by ST69 (ONT:H18 and O11:H18) and ST73 (O22:H1, O25:H1, O6:H1, and ONT:H1) with five isolates each. Isolates from phylogroup B2 were the most prevalent (n=38; 56 %), and the least prevalent were from B1 (n=3; 4 %).

Fig. 2.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees showing genetic relatedness of ExPEC strains. Tree scale bars represent number of substitutions per site of alignment. (a) Mid-point rooted maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree, inferred using iq-tree 2 and K12-MG1655 as a reference, containing the 67 ExPEC isolates sequenced in this study. Coloured circles represent uro-clinical syndrome (black, cystitis; white, pyelonephritis; red, urosepsis). The inner-most ring represents the phylogroup (A, red; B1, green; B2, light blue; D, purple). The next ring represents ST. The two outermost rings apply to ST131 isolates only (marked in red shaded area), the inner ring highlights fimH alleles (orange, fimH30; green, H27) and outer ring shows the presence or absence of bla CTX-M-15 (blue, present; yellow, absent). Letters around the perimeter represent multiple isolates taken from a single patient, one letter per patient. (b) SNP-based phylogenetic tree, inferred using iq-tree 2, resolving ST131 isolates into clades. H30R, blue shaded area; H30Rx, green shaded area. Trimethoprim-susceptible ExPEC isolates ERR434278, ERR434751, ERR434270, ERR434273 and ERR434271, and trimethoprim-susceptible EAEC isolates SRR5470250, SRR5024242 and SRR3574247 were added as controls.

The fact that ST131 isolates, which are associated with ESBL resistance, outnumbered ST69 isolates, which are associated with trimethoprim resistance [63], is reflective of the high number of UTIs caused by ST131, particularly in association with pyelonephritis, within this regional NSW community [64–66]. To resolve the ST131 isolates into clades, we screened for fimH alleles in conjunction with a separate SNP-based phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2b). Only one ST131 isolate, HOS40, carried H27; thus, it belonged to clade B, a clade associated with animal to human transmission [67]. All other ST131 isolates carried H30, thereby belonging to the globally dominant clade C [24]. Of the ST131 H30 isolates, 7 (37 %) were H30R (clade C1) and 11 (61 %) were ESBL blaCTX-M-15-associated H30Rx (clade C2) [25]. SNP analyses showed that the H27 isolate differed from H30 by a mean of 277 SNPs, and that H30R isolates differed from H30Rx by a mean of 93 SNPs. The H30Rx isolates originated from different patients, situated in seven different postcodes (~300 km between the two most distant postcodes), caused either cystitis or pyelonephritis, and were isolated over a period of 569 days. Yet despite these differences, the H30Rx isolates differed by only seven SNPs on average (across 99.6 % of the reference H30Rx HOS54 genome), indicating a persistent clone in this community. Conversely, H30R isolates differed by a mean of 58 SNPs, due to the presence of two distinct branches (Fig. 2b; i and ii), and the SNP difference between H30R and H30Rx branches was 140. The pangenome for this collection consisted of 14 091 genes making up a core genome of 2886 genes and an accessory genome of 11 205 genes, leading to a total pangenome length equal to 11.32 Mb, and can be viewed in Data S2.

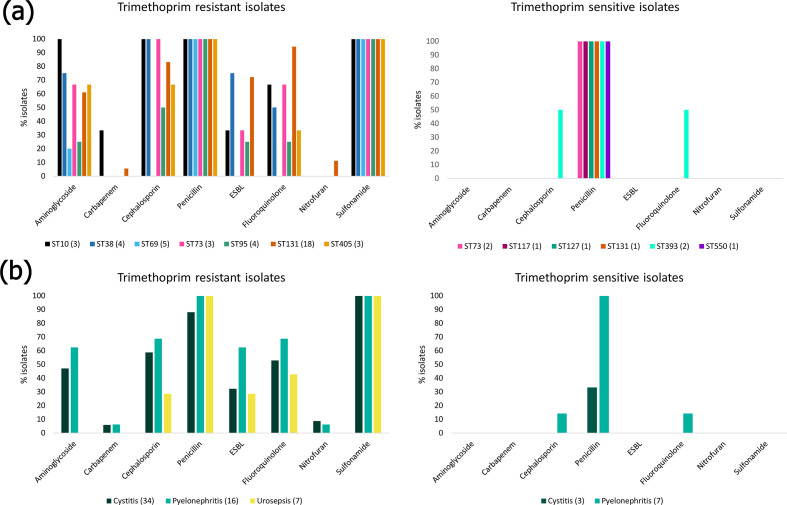

Phenotypic resistance

ExPEC have been a driving force behind a worldwide increase in ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae [68]. Furthermore, ExPEC isolates have been reported as carrying transmittable resistances to carbapenem and colistin [69, 70], both being last-line antibiotics for multidrug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative bacteria. The World Health Organization (WHO) has flagged increasing cases of MDR bacteria worldwide as one of the most serious public-health threats and deemed surveillance as a strategic priority of the Global Action Plan on AMR [71]. Despite trimethoprim remaining a first-line empirical treatment option for UTIs, resistance in uropathogens is increasing worldwide. In Australia, resistance to trimethoprim in E. coli has increased from 16.6 % in 2004 [72] to 31.2 % in 2017 [73]. These figures and trends are similar to those in other developed countries, though lower than in developing countries were trimethoprim resistance in UTI-associated ExPEC ranges from 54 to 82 % [74]. Isolates were tested against 11 antibiotics (Fig. 3). The mean number of antibiotics an isolate was resistant to was five, with two isolates (HOS56 and HOS70, both ST131 H30Rx) being resistant to 10/11 tested (all bar the carbapenem imipenem). The most-common resistance phenotype, aside from trimethoprim and trimethoprim/sulphonamide, was ampicillin (n=50; 75 %). High levels of ampicillin resistance in UTIs have been described worldwide, leading to governing bodies recommending its disuse [4]. The least common phenotypic resistances were to imipenem (n=2; 3 %) and the anaerobic DNA inhibitor nitrofurantoin (n=4; 6 %). This hopeful observation indicated that both a first and a last-line treatment option for UTIs remained largely efficacious, at least in the past, though low levels of nitrofurantoin and imipenem resistance continue to be reported in UTI isolates currently [75, 76]. Antibiotic resistance varied by ST (Fig. 3a) and uro-clinical syndrome. Isolates originating from patients with cystitis and pyelonephritis shared similar phenotypic resistance profiles; however, isolates from urosepsis patients tended to be more sensitive and no isolate was resistant to the aminoglycoside gentamicin, the cephalosporin cefotaxime, nitrofurantoin or imipenem (Fig. 3b). A high co-occurrence (>30 %) of trimethoprim and ESBL resistance was recently reported in the USA [77]. Furthermore, Mulder et al. [78] demonstrated that previous use of extended-spectrum β-lactams in patients with UTIs was significantly associated with trimethoprim resistance. These data are reflective of treatment practices and suggests a step-wise acquisition of resistances to antimicrobials over time, having become resistant to first-line treatment and then increasingly to ESBLs.

Fig. 3.

Phenotypic resistance of ExPEC isolates. (a) Phenotypic resistance profiles by ST. For trimethoprim-resistant isolates, only STs with three or more isolates were included. Full phenotypic resistance profiles can be viewed in Data S3. (b) Resistance phenotypes by uro-clinical syndrome.

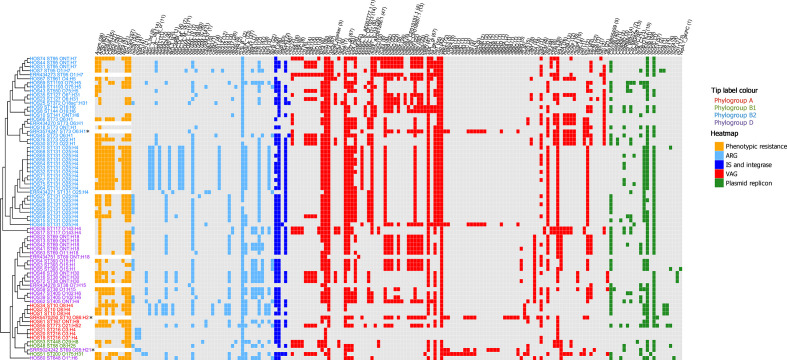

Genetic screening

This collection was screened for ARGs, ISs associated with AMR, class 1 and 2 integrases (intI1, intI2), heavy-metal-resistance genes, VAGs and plasmid replicons using ariba (Fig. 4). A full list of identified genes and associated metadata for each isolate is available in Data S3.

Fig. 4.

Genotypic profile of 73 ExPEC isolates. Tip label colour corresponds to phylogroups (red, A; green, B1; teal, B2; purple, D). The adjacent heatmap represents phenotypic resistances and intact genes present in each isolate (orange, phenotypic resistance; light blue, ARG; dark blue, IS and class 1 and 2 integrase (intI1, intI2); red, VAG; green, plasmid replicon). Along the top of the heatmap, the numbers in brackets after gene names represent the total number of isolates with trait present). Trimethoprim-susceptible ExPEC isolates ERR434278, ERR434751, ERR434270, ERR434273 and ERR434271 and trimethoprim-susceptible EAEC isolates SRR5470250, SRR5024242 and SRR3574247 (marked by asterisks) from other studies were added as controls. The tree on the left side is the maximum-likelihood tree seen in Fig. 2 (reference K12 MG1655 omitted) presented in cladogram form.

ARGs

AMR in uropathogens complicates the treatment of UTIs. An advantage of WGS in AMR surveillance is the level of detail and precision gleaned from identifying specific ARG alleles, and co-resistances not tested on standard antibiotic panels, including disinfectant and heavy-metal-resistance genes [59]. Here, we identified a total of 40 ARGs (Fig. 4), with the majority of isolates (n=56; 84 %) carrying at least three ARGs.

The most common mechanism for acquiring trimethoprim resistance is through the acquisition of dfr genes [79]. There are currently more than 40 identified dfr variants [80]. These are often associated with MGEs, such as plasmids and transposons, and are almost exclusively observed as resistance gene cassettes within the variable regions of class 1 and 2 integrons in human [81], animal [35, 82, 83] and environmental [84] E. coli isolates, resulting in their rapid spread. Seven trimethoprim-resistance genes were identified in this collection, the most common being dfrA17 (n=26; 38 %), followed by dfrA12 (n=12; 18 %). Several ESBL genes were also detected, the most common being of the bla CTX-M type (n=18, 26 %). bla CTX-M progenitor genes are thought to have originated from the chromosomes of soil bacteria [85] and their subsequent capture by predominately IncF family plasmids has led to their global dissemination in both clinical and non-clinical settings [30]. IncF family replicons were the most prevalent replicons detected in this collection, the foremost being IncFIB (n=53; 79 %), followed by IncFII (n=51; 76 %). Additionally, IncFIA replicons were detected in 30 isolates (44 %). While bla CTX-M ESBLs comprise a heterogeneous family of enzymes, the bla CTX-M-15 and bla CTX-M-14 variants are currently most prevalent worldwide and are strongly associated with ST131 [30], though other STs have also contributed to their spread [86]. In this historic collection, blaCTX-M-15 (n=11; 16 %) and bla CTX-M-14 (n=7; 10 %) were the only two bla CTX-M variants identified. All bla CTX-M-15 genes were carried solely by ST131 H30Rx isolates (Fig. 2a). Conversely, the blaCTX- M-14 genes were present in four ST38 isolates, the sole examples of ST648 and ST773 and an H30R ST131 isolate. UTI isolates carrying bla CTX-M genes have previously been noted exhibiting high co-resistance to trimethoprim [77]. In this collection, all isolates carrying bla CTX-M-15 also carried dfrA12, and all isolates carrying blaCTX-M-14 co-occurred with dfrA17. Three additional ESBL genes were identified, bla OXA-10 , bla TEM-214 [87] and bla TEM-57 [88], occurring in one ST95 isolate, one ST131 H30R isolate and one ST448 isolate, respectively.

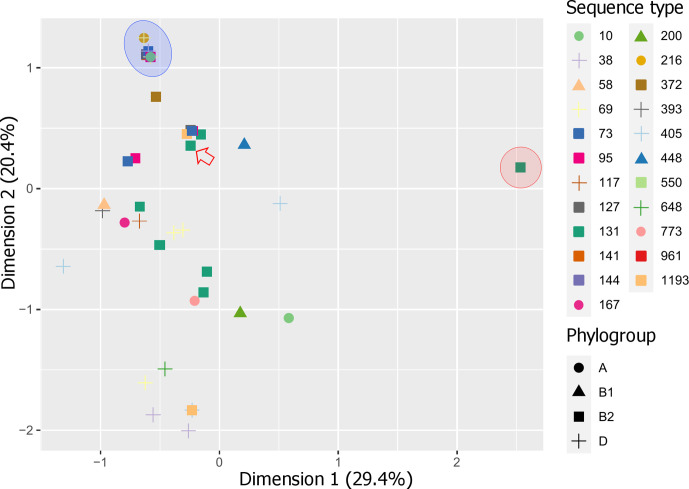

In addition to trimethoprim- and ESBL-resistance genes, other common ARGs identified were β-lactamase gene bla TEM-1B (n=49; 73 %), sulphonamide-resistance gene sul1 (n=46; 69 %), aminoglycoside-resistance gene aadA5 (n=25; 37 %), tetracycline-resistance gene tetA (n=22; 30 %) and macrolide-resistance gene mphA (n=31; 46 %). Fluoroquinolone-resistance genes aac(6)-Ib-cr (n=11; 16 %) and qepA1 (n=1; ST448) were also detected. Isolates belonging to phylogroup D contained the most ARGs on average (nine per isolate), consistent with reports stating that an MDR profile in ExPEC is most associated with this phylogroup [89–91]. However, three ST10 isolates of phylogroup A carried the highest number of ARGs overall (n=14). An MDS analysis demonstrated that ST131 H30Rx isolates possessed the most distinct ARG profiles (Fig. 5, red area), which could be attributed to the strong correlation of aac(3)-IIa, aac(6)-Ib-cr, aph(3′)-Ia, aadA2, bla CTX-M-15, bla OXA-1 and dfrA12 in this ST and clade (Data S4). Notably, all the trimethoprim-sensitive ExPEC and EAEC isolates used as controls in this study clustered together with four trimethoprim-sensitive isolates from this collection (Fig. 5, blue area), with the exception of one control ExPEC ST131 isolate (Fig. 5, red arrow).

Fig. 5.

MDS analysis of ARGs detected in the ExPEC collection. Red area, ST131 H30Rx cluster (11 isolates share the same coordinate); blue area, trimethoprim-sensitive control isolates clustered with four trimethoprim-sensitive isolates from this collection, with the exception of one control ST131 isolate (red arrow). The percentage of total explained variation for each dimension is indicated in parentheses after each axis label.

Heavy-metal- and detergent/disinfectant-resistance genes are often carried by the same MGEs harbouring ARGs, sparking concern and growing evidence that selective pressures induced by their extensive use in industry, agriculture and health-care facilities, as well as via contamination, can co-select for AMR [92–94]. The hospital wherein our isolates originated caters for a catchment area significantly associated with agriculture, including food animals (bovine, sheep, pig and poultry), and various crops, such as fruits and nuts [95]. Thus, the isolates were screened, and two detergent-resistance genes – qacEΔ1 (n=47; 70 %) and qacH (n=3; 4 %) – conferring resistance to quaternary ammonium compounds, and six heavy-metal-resistance genes were identified. All isolates carried zntA, which confers resistance to zinc, lead and cadmium. We also identified chrA (n=32; 48 %), corresponding to chromium resistance, and merA (n=16; 24 %), which confers mercury resistance. Silver- and copper-resistance genes silA and pcoA were present in only three isolates (4 %; all ST216) and tellurium-resistance gene terA was observed in a single ST200. Heavy-metal-resistance genes, including zntA, merA, pcoA and chrA, are known to be significantly associated with detergent resistance genes, and sul, tet, blaTEM, blaSHV and blaCTX variants [93]. Furthermore, chromium resistance has been positively correlated with relative blaCTX-M and bla OXA gene abundance [96]. Here, 100 % of isolates carrying blaCTX-M genes also carried chrA, and 91 % of isolates with blaOXA also harboured chrA.

Class 1 and 2 integrons

The presence of class 1 or 2 integrons is considered a reliable proxy for an MDR genotype [97]. Class 1 integrons are more prevalent than class 2 integrons [97] and typically contain two conserved regions – 5′-CS and 3′-CS – flanking a variable gene cassette. The intI1 integrase gene, responsible for capturing, removing and rearranging genes within the variable cassette, is located in the 5′-CS region. The 3′-CS region typically contains a truncated but functional qacEΔ1 gene fused to a sul1 gene [98]. Class 1 and 2 integrons are mobilized and spread by MGEs, such as transposons and conjugative plasmids. Additionally, the insertion element IS26 is renowned for its ability to capture and assemble ARGs in complex resistance regions [32] and alter the structure of class 1 integrons [35, 98]. Here, IS26 was identified in 63 (94 %) isolates, including all 45 (67 %) that carried intI1.

Class 1 and 2 integron loci are often rich in repetitive sequences, posing challenges to assembling complete structures using short-read sequencing data. Despite this limitation, we resolved 18 class 1 integron structures, including ARGs and MGEs found downstream of the typical 3′-CS region (Fig. 6a) and 1 class 2 integron (Fig. 6b). blastn and GenBank were used to determine whether these integrons had been previously deposited into public databases (Table 1). In general, the integrons from this collection are also found in ExPEC-associated STs, most commonly ST131 and ST617 [of ST10 clonal complex (CC)]. They are most frequently seen on IncF plasmids of varying plasmid multilocus sequence types (pMLSTs), in a range of hosts, including humans, dogs and gulls, and from a range of geographical locations, including Europe, Asia, North America and Australia (Table 1). The most common genes located in the variable gene cassette were dfrA17 and aadA5 (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6.

Class 1 and class 2 integron structures. (a) Class 1 (a–r) and class 2 integrons structures identified in this collection. ST131 H30R i and ii refer to the two H30R subclades resolved by the SNP-based phylogeny presented in Fig. 2(b). (b) EasyFig comparison of integron b and the chromosome-associated integron structure from Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain SP4527.

Table 1.

Summary of blast hits to integrons found in this collection

Rows in bold indicate integrons with no 100% matches. The closest integron match is provided

|

Integron |

Accession no. |

Coverage; Identity |

Integron location |

Inc group (pMLST) |

Isolation date |

Species (ST)/ [STs from this collection] |

Host |

Host disease |

Host location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

a |

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

I1 (CC-3) |

2013 |

E. coli (na)/[ST10] |

Chicken |

na |

Belgium |

|

|

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

F (F-:A18:B-) |

2016 |

E. coli (ST617) |

Human |

na |

Germany |

||

|

b |

93 %; 100 % |

Chromosome |

– |

2016 |

P. aeruginosa (ST357)/[ST95] |

Human |

Sepsis |

India |

|

|

c |

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

F (F2:A-:B1) |

2010 |

E. coli (ST58)/[ST58, ST117, ST141] |

Cow |

Mastitis |

France |

|

|

d |

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

F (F29:A-:B10) |

2014 |

E. coli (ST69)/[ST69] |

Human |

Sepsis |

USA |

|

|

e |

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

F (F31:A4:B1) |

2018 |

E. coli (ST410)/[ST131, ST200] |

Dog |

Cellulitis |

Portugal |

|

|

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

F (F36:A1:B20) |

2008 |

E. coli (ST131) |

Human |

na |

Sweden |

||

|

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

F (F2:A1:B-) |

2014 |

E. coli (na) |

Human |

Healthy |

UK |

||

|

f |

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

F (F1:A6:B20) |

2007 |

E. coli (ST131)/[ST10, ST405, ST648, ST1193] |

Human |

na |

Israel |

|

|

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

F (F1:A6:B20) |

2015 |

E. coli (ST131) |

Dog |

na |

Israel |

||

|

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

F (F1:A6:B20) |

2015 |

E. coli (ST131) |

Human |

na |

Israel |

||

|

g |

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

F (F1:A6:B20) |

2007 |

E. coli (ST131)/[ST38] |

Human |

na |

Israel |

|

|

h |

84 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

N (A2:N5:J-) |

na |

E. coli (ST617)/[ST127] |

na |

na |

na |

|

|

i |

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

F (F2:A1:B-) |

na |

E. coli (ST131)/[ST131] |

Human |

na |

USA |

|

|

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

F (F2:A1:B1) |

2015 |

E. coli (ST131) |

Yak |

na |

China |

||

|

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

F (F2:A1:B1) |

2015 |

E. coli (ST131) |

Yak |

na |

China |

||

|

j |

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

F (F51:A-:B10) |

2010 |

E. coli (ST95)/[ST73, ST95, ST550] |

Human |

Sepsis |

Australia |

|

|

k* |

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

F (F22:A1:B20) |

2009 |

E. coli (ST131)/[ST131, ST405] |

Human |

Post UTI |

Sweden |

|

|

100 %; 100% |

Contig |

– |

2013 |

E. coli (na) |

Environment |

na |

India |

||

|

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

F (F73:A-:B-) |

2000 |

E. coli (ST73) |

Human |

na |

USA |

||

|

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

F (F2:A-:B-) |

2008 |

E. coli (ST95) |

Human |

Sepsis |

USA |

||

|

l |

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

F (F29:A-:B10) |

2014 |

E. coli (ST69)/[ST69] |

Human |

Sepsis |

USA |

|

|

m |

100 %; 100 % |

Chromosome |

– |

2015 |

E. coli (ST38)/[ST38] |

Gull |

na |

Turkey |

|

|

100 %; 100 % |

Chromosome |

– |

2014 |

E. coli (ST38) |

Mollusc |

na |

Norway |

||

|

100 %; 100 % |

Chromosome |

– |

2016 |

E. coli (ST38) |

Gull |

na |

USA |

||

|

n |

97 %; 99.97 % |

Chromosome |

– |

2015 |

E. coli (ST359)/[ST1193] |

Human |

Healthy |

Netherlands |

|

|

o |

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

F (F2:A1:B-) |

2013 |

E. coli (ST131)/[ST773] |

Human |

na |

USA |

|

|

p |

100 %; 100% |

Plasmid |

F (F36:A4:B-) |

2018 |

E. coli (ST617)/[ST167] |

Dog |

na |

USA |

|

|

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

F (F33:A4:B-) |

na |

E. coli (na) |

na |

na |

China |

||

|

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

F (F36:A4:B-) |

2013 |

E. coli (ST617) |

Human |

na |

China |

||

|

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

F (F36:A4:B-) |

na |

E. coli (ST617) |

na |

na |

na |

||

|

100 %; 100 % |

Plasmid |

F (F36:A4:B-) |

2013 |

E. coli (ST617) |

Human |

UTI |

China |

||

|

q |

100 %; 99 % |

Plasmid |

F (F48:A1-:B49) |

2009 |

E. coli (na)/[ST405] |

Human |

UTI |

Sweden |

|

|

r |

100 %; 99 % |

Plasmid |

F (F36:A-:B32) |

2007 |

E. coli (ST131)/[ST448] |

Human |

UTI |

USA |

na, Not Applicable.

*Only 100% matches from E. coli are shown.

Integron k was the most common structure in this collection, present in 12 isolates (from ST131 and ST405), and carried dfrA12 (trimethoprim), aadA2 (aminoglycoside), qacEΔ1 (quaternary ammonium compounds), sul1 (sulphonamide) and mphA (macrolide) resistance genes. The same integron was described in an ST131 H30Rx isolate taken from a French patient a year after contracting pyelonephritis while travelling in Nepal [99]. The integron k structure also carried the aforementioned chromium resistance gene chrA, which in turn was also present in seven other integron structures (d, e, f, g, l, m and r). Class 1 integrons are often translocated via mercury-resistance transposons carrying genes of the mer operon [81], and such transposons were present in integrons i, j and n structures. Integrons n and r also carried a recently characterized dfrB4 gene conferring high-level resistance to trimethoprim. Both isolates that carry these integrons (ST1193 and ST448) predate the first report of this gene in a clinical sample (UTI) in 2017 [100]. Additionally, integron r carried an uncommon plasmid-mediated fluoroquinolone-resistance gene, qepA. Integron b was the only structure to carry an ESBL gene (blaOXA-10) and carried additional genotypic resistance genes for trimethoprim (dfrA15), chloramphenicol (cmlA1), aminoglycosides (aadA1) and sulphonamides (sul1). An identical structure to integron b could not be found in public databases; however, a similar structure was observed chromosomally in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain SP4527 (ST357) isolated from a patient with bacteraemia in India, in 2016 (Fig. 6b). Integron c consists of a short dfrA5-IS26 configuration that has been detected in, and is identical to, E. coli strains sourced from cattle located on several NSW properties [98, 101], and in commensal E. coli from Australian pigs [35]. Furthermore, the signature has been used to track ColV plasmids carrying a complex resistance locus in patients with UTI and urosepsis in Australia in E. coli ST58 [102, 103]. These studies highlight how plasmids that play an important role in carrying intestinal pathogenic E. coli virulence genes [101] and extraintestinal pathogenic virulence gene cargo [102, 103] can be tracked by the presence of this unique signatures. Moreover, it shows that transposon belonging to the Tn3 family of mercury-resistance transposons can mobilize complex resistance loci on diverse plasmid backbones. Integron l has been described within a larger salmonella genomic island 1 (SGI1) structure in Proteus mirabilis [104]. The integron a structure carried the sole example of a sul3 gene, which has been associated with Australian E. coli isolates from pig farms [35, 83]. This integron, found in our ST10 isolates, also uniquely carried dfrA16, blaCARB-2 and qacH. Integron a has been located on IncFIA and IncI plasmids in CC10 (ST617) E. coli isolates originating from both human clinical samples from Germany and the USA, a broiler chicken sample from Belgium (Table 1), as well as farmed red deer from Spain [105]. Incidentally, the patients from whom these isolates originated resided in proximity to two red deer farms. Lastly, the class 2 integrase intI2 gene was identified in one ST372 and one ST73 isolate (Fig. 6b). The intI2 from this class of integron is inactive, impeding its ability to modify gene cassettes. Thus, class 2 integron cassettes are highly conserved [97]. The dfrA1-sat2-aadA1 cassette found in this collection represents the most common array, and is particularly prevalent in UTI-associated Proteus species [106].

VAGs

ExPEC employ a range of VAGs that enable ascension, colonization and persistence within the urinary tract. Like ARGs, many VAGs are also carried on MGEs, including plasmids as well as chromosomally situated PAIs [15]. Thus, the virulence potential of ExPEC strains is constantly evolving and tracking VAGs improves understanding of ExPEC pathogenesis. Using the VirulenceFinder database, a total of 84 VAGs were identified in this collection, with the number of VAGs per isolate spanning from 2 to 36, with a mean of 20 and a median of 19.

To combat the iron-scarcity encountered in the urinary tract, ExPEC have acquired a number of siderophore and ferrous iron uptake systems to scavenge Fe3+ and Fe2+, which are vital for growth, persistence and establishing full virulence [15]. ExPEC-associated iron-acquisition systems include yersiniabactin (ybt, irp, fyuA), salmochelin (iro), aerobactin (iuc, iut), ferric citrate transport system (fec) and the Sit ferrous iron utilization system (sit). In this study, the most common iron-acquisition genes were fyuA, irp2 and sitA (all n=61, 91 %), followed by iucD and fecA (both n=45; 67 %). The high carriage of fyuA is consistent with previous reports tracking VAGs in ExPEC [14, 107, 108]. While there are contradicting reports regarding fyuA and mortality [107, 109, 110], immunization with FyuA has been shown to protect against pyelonephritis in mice [111].

Several adhesins and fimbriae demonstrate specificity for binding uroepithelium. Of these, the type 1 fimbriae and P-fimbriae are most prevalent in UTI-associated ExPEC [15]. Type 1 fimbriae bind uroepithelial associated α-d-mannosylated proteins via fimbrial adhesin H (fimH). Thus, the fimH gene plays a pivotal role in ExPEC urothelial adhesion [15]. P-fimbriae (pap genes) bind α-d-galactopyranosol(1–4)-β-d-galactopyranoside-containing receptors found in the upper urinary tract and, therefore, have been associated with pyelonephritis [112]. Here, the most common adhesins identified were fimH (n=61; 91 %), papB (n=47; 70 %) and papI (n=45; 67 %). However, other P-fimbriae operon genes were less common, such as papC, papD, papJ and papK (each n=20; 30 %), papF (n=21; 31 %), papH and papG (both n=19; 28 %), and papA (n=17; 25 %).

In addition to factors facilitating adhesion and growth, ExPEC express toxins contributing to host tissue damage, as well as immune evasion molecules [113]. Regarding toxins, several serine protease autotransporters of Enterobacteriaceae (SPATE) genes were identified including sat (secreted autotransporter toxin) (n=39; 58 %), which has been shown to compromise gap junctions in uroepithelium [112], vat (n=18; 27 %) and pic (n=8, 12 %). Enterotoxins senB (n=21; 31 %) and astA (n=4; 6 %) were also observed. Regarding immune evasion, VAGs encoding increased serum survival protein (iss), VirB5-like protein TraT (traT) and outer-membrane protein T (ompT) where identified in 52 (78 %), 50 (75 %) and 5 (7 %) isolates, respectively.

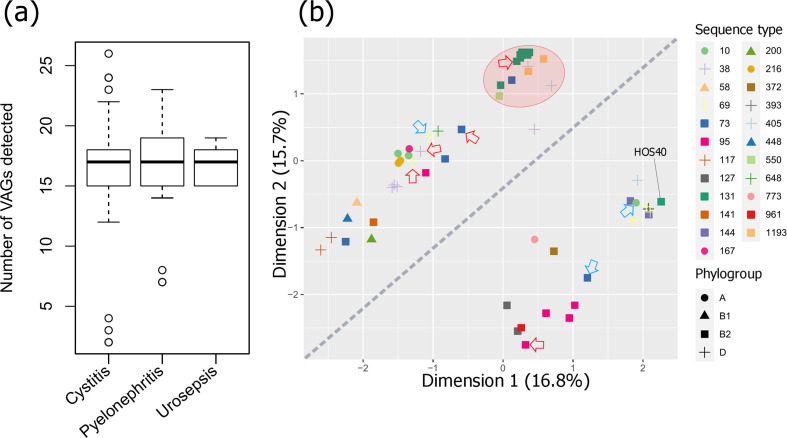

Despite studies reporting various VAGs linked to pyelonephritis and sepsis [15, 114, 115], we found no single gene nor plasmid replicon strongly associated with a particular pathology (correlation heat map in Data S5), nor was there a significant difference between the number of VAGs present and uro-clinical syndrome (Fig. 7a). The discrepancy with the literature may have arisen due to sampling based on trimethoprim resistance and/or the relatively small sample size, limiting statistical power. Nevertheless, an MDS analysis showed some clustering of STs based on virulence profiles (Fig. 7b). Notably, isolates formed two distinct diagonal groups, which could be attributed to the distribution of pap genes with papC, papD, papJ and papK present in all isolates within the distal group and absent in all isolates in the top group. Other pap genes were also more prevalent in the bottom group including papGII (0 % top, 78 % bottom), papGIII (0, 17 %), papH (0, 96 %), papE (4%, 0 %) and papF (4, 96 %). Also of note was that the ST131 H30 isolates clustered with two emerging pathogen STs, ST405 [116] and ST1193 [117], as well an ST550 isolate [same CC as ST1193 – CC14] and one ST73 isolate that deviated from other ST73 isolates (Fig. 7b, red area). The ST131 H30 isolates fell under virotype C [afa operon (−), iroN (−), ibeA (−), sat (+)], which is the most represented ST131 virotype internationally and associated with a higher frequency of infection [118]. The other isolates within this cluster could also be categorized as virotype C. The only ST131 H27 isolate did not cluster with its ST and carried the molecular predictors of EAEC/ExPEC hybrid strains (aatA, aggR, fyuA), as did one ST200 isolate. The EAEC isolates sourced from outside this collection (Fig. 7b, blue arrows) all deviated from ExPEC isolates of the same ST; however, they did not form a separate cluster and each carried ExPEC-associated genes including fyuA (Fig. 4). These EAEC isolates were not previously described as hybrid strains and originated from cases of diarrhoeal disease in England [40]. However, hybrid EAEC/ExPEC strains are known to cause UTI outbreaks [119, 120]. EAEC strains carry most of their virulence cargo on plasmids and are renowned for prolific biofilm formation [121]. Indeed, EAEC/ExPEC hybrid strains have shown significantly higher levels of biofilm formation, as well as enhanced adhesion to uroepithelium cells, compared to non-hybrids [122].

Fig. 7.

Statistical analysis of VAGs detected in the ExPEC collection. (a) Box plot of uro-clinical syndrome versus the number of VAGs. Genes in operons cvaABC(i), eitABCD, papABCDEFGHIJK, aafABCD, aggABCDR and mchBCF were counted as one if at least one gene was present. (b) MDS analysis on detected VAGs. Additional ExPEC isolates sourced from outside this collection are indicated by red arrows, additional EAEC isolates are indicated by blue arrows. The diagonal line splits isolates into a pap gene rich group (below the line) and a pap gene poor group (above the line). The red area highlights the ST131 H30 isolates cluster with two emerging pathogen STs, ST405, ST1193, as well an ST550 isolate and one ST73 isolate. The percentage of total explained variation for each dimension is indicated in parentheses after each axis label.

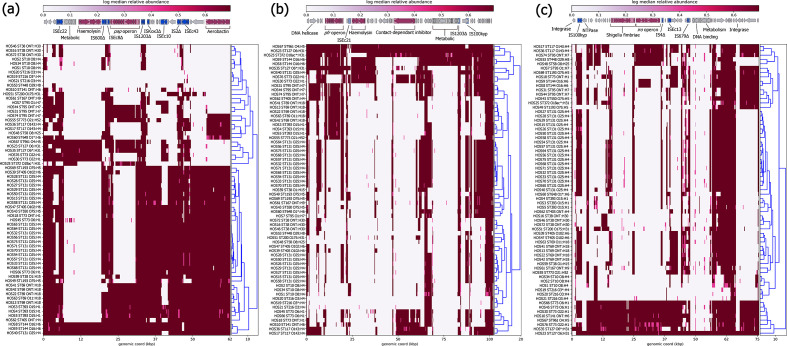

PAIs

The PAI marker genes malX and usp were seen in 44 (66 %) and 38 (57 %) isolates, respectively. The acquisition of PAIs via horizontal transfer can vastly contribute to the evolution of E. coli pathogens as they contain potent combinations of VAGs, including the aforementioned P-fimbriae, salmochelin, aerobactin and yersiniabactin operons, as well as shigella-fimbriae (S-fimbriae, sfa) and haemolysin toxin (hly) operons [123, 124]. As such, to indicate the presence of ExPEC-associated PAIs, we used short-reads derived from each isolate mapped to reference sequences PAI ICFT073, PAI II536 and PAI III536. PAI IV536 [also known as high pathogenicity island (HPI)] was also screened for; however, possibly due to allelic differences, the read-depth was relatively lower for this PAI (Data S6) so blast was used in conjunction with assembled draft genomes to indicate its presence. While all isolates had at least partial hits to genes and gene clusters within PAI ICFT073, PAI II536 and PAI III536, most demonstrated extensive deletions of regions, and few had near intact examples (Fig. 8). The most represented VAG operon was aerobactin in PAI ICFT073 and the least were S-fimbriae in PAI III536. However, PAI IV536 – which consists of the yersiniabactin operon (ybt genes, irp1, irp2, fyuA; total 11 genes), a P4-like integrase and an uncharacterized protein YeeI nestled between tRNA-Ser and tRNA-Asn – was identified over >95 % length at >98 % identity in 58 isolates (Data S7). In addition to being a potent siderophore system, yersiniabactin can protect against copper toxicity, redox-based phagocytosis and is a prerequisite for sepsis in some E. coli strains [19].

Fig. 8.

Mapping of short-reads indicating the presence of ExPEC-associated PAIs. Clustering of rows is based on the similarity between isolate PAI coverage profiles. (a) Schematic and heatmap for PAI ICFT072 coverage. (b) Schematic and heatmap for PAI II536 coverage. (c) Schematic and heatmap for PAI III536coverage. Trees alongside the heatmaps were reconstructed by hierarchical clustering using Euclidean agglomeration method.

ColV plasmid markers

ColV plasmids are considered a defining feature of APEC (avian pathogenic E. coli ) [125]; however, they have also been associated with human ExPEC strains [102, 126]. While the expression of colicin V may benefit ExPEC strains by reducing competition for nutrients [127], ColV plasmids are intriguing in that they share high sequence homology to PAIs, and it is theorized that they and other plasmids and phages are the progenitors of ExPEC-associated PAIs [123]. As ColV plasmids are heterogeneous in their VAGs and pMLST, Liu et al. [67] defined ColV plasmids as having at least one gene from four or more of the following: (i) cvaABC and cvi (ColV operon); (ii) sitABCD (ferrous iron utilization system); (iii) hlyF (regulator of outer membrane vesicle biogenesis) and ompT; (iv) iucABCD and iutA (aerobactin operon); (v) iroBCDEN (salmochelin operon); and (vi) etsABC (novel ABC transport system). In this study, ariba gene screening identified seven isolates (10 %) meeting this criterion – HOS66 (ST73, cystitis), HOS45 (ST73, cystitis), HOS74 (ST95, cystitis), HOS17 (ST117, pyelonephritis), HOS36 (ST117, pyelonephritis), HOS48 (ST58, cystitis) and HOS53 (ST448, cystitis). Three of these isolates (HOS17, HOS36 and HOS48) also carried the aforementioned integron c (dfrA5-IS26) that is used to track ColV plasmids containing complex AMR regions. Future long-read sequencing studies are needed to provide deeper insight into these initial observations (plasmid short-read mapping is provided in Data S8).

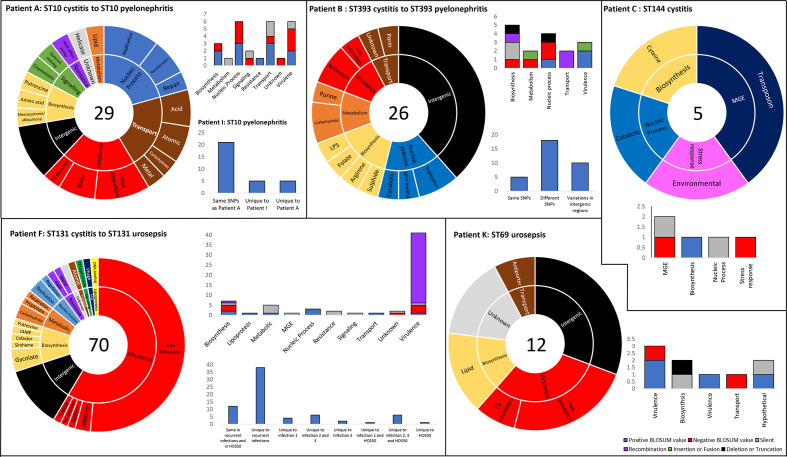

SNP analysis of serial patient isolates

Phenotypic diversification via adaptive evolution is driven by horizontal gene transfer and by mutation [128]. A single SNP-mediated point mutation can lead to an amino acid replacement with significant adaptive effects, as witnessed in single amino acid replacements in parC/E and gyrA genes causing fluoroquinolone resistance [24, 25], and in fimH, which increases binding to uroepithelium and biofilm formation [129]. Such adaptive mutations can increase bacterial fitness and provide rapid adaption to niche-specific conditions [128]. ExPEC are exposed to a variety of niches in addition to their primary reservoir, the intestinal tract, and as a result may be under greater selective pressure for adaptive mutations. Indeed, UTI-associated ExPEC are known to have significantly higher mutation rates compared to other E. coli pathotypes [130]. While studies have been conducted comparing SNP-mediated point mutations in UTI and faecal isolates [131], relatively little is known about the SNPs that occur in recurrent UTIs, particularly when subsequently more serious sequelae occur. In this study, 13 patients had more than one presentation of symptomatic UTI during the study period (indicated by letters in Fig. 2). Six patients had subsequent UTIs caused by the same ST, and seven patients had different STs. Here, we focus on the patients who had multiple infections with the same ST (Fig. 9), and on SNP-mediated mutations with a higher probability of inducing functional changes as predicted by the BLOSUM62 substitution matrix [132]. A catalogue of all SNPs can be viewed in Data S9.

Fig. 9.

Serial patient isolates – SNP distribution and consequence to amino acid sequence. Each panel represents a UTI patient from whom multiple isolates of the same ST were derived. Sunburst graphs represent the distribution of SNPs within functional groups. The number in the centre represents the total number of unique SNPs (accumulative if more than one recurrent infection occurred). Stacked column graphs represent the consequence of SNPs to protein sequence. Color legend for the stacked columns located bottom right corner. Unstacked column graphs represent the distribution of specific SNPs in recurrent infections from the same patient, and in the case of patient A and F, two different patients.

Patient A was a 37-year-old female who in the first instance presented with cystitis with an ST10 isolate (HOS1) as the causative agent and then pyelonephritis (HOS2; ST10) 63 days later. The ST10 isolates had a difference of 29 SNPs, with most occurring in genes involved in DNA processing, transport and virulence (Fig. 9). However, mutations with negative BLOSUM62 scores (indicating a higher probability that the original function is not conserved) occurred most frequently in VAGs and DNA processing. Potentially increasing the significance of the observed mutations, another patient, a 69-year-old male living in the same postcode, presented with pyelonephritis 16 days after patient A’s second presentation. The causative agent was also an ST10 (HOS34), which shared 71 % (n=24) of the same SNPs found in HOS2. Both HOS2 and HOS34 had the same SNPs causing non-synonymous amino acid substitutions with negative BLOSUM scores in the following genes: irp1 (D2717A), ybtS (P184A), astA (G103V), aroC (G152E), rnhB (R98L), hrpB (G644E), traC (G644W), lsrA (E296G) and recC (S794C). Interestingly, recC was previously shown to be under positive selective pressure for adaptive mutations [130]. Though not present in HOS34, HOS2 possessed a SNP causing A432D (negative BLOSUM62 score) in DNA-repair protein Mfd (mutation-frequency-decline). Mfd promotes mutagenesis and accelerates AMR development to multiple antibiotic classes [133]. Fascinatingly, point mutations produce Mfd variants that express greater activity than wild-type [134].

Patient B was a 21-year-old-female who first presented with cystitis (HOS3) then pyelonephritis 284 days later (HOS4, 13 SNP difference), then pyelonephritis again 128 days later (HOS5, 19 SNP difference from HOS3). The causative agent in each episode was ST393; however, unlike the high percentage of conserved SNPs in ST10 pyelonephritis isolates, HOS4 and HOS5 ST393 only shared 23 % of all SNPs against the HOS3 reference, possibly due to the longer period between isolations, and only shared two negative BLOSUM62 score amino acid substitutions in chromosome partition protein MukF (F401V and T394H). Most SNPs occurred in intergenic regions, which may be significant as these regions often contain riboswitches, promoters, terminators and regulator binding sites, and SNPs can cause significant phenotypic changes [135].

Patient C was a 64-year-old female with cystitis and two samples were taken on the same day. Both isolates (HOS8 and HOS9) were ST144 and differed by five SNPs. While no SNPs occurred in VAGs (Fig. 9), two mutations with potential for functional change were identified in transposase TnpB (G11R) and environmental stress protein Ves (G7R). Conversely, in patient H, a 67-year-old male who presented with cystitis (HOS33; ST131 H30Rx) and then cystitis again a week later (HOS34; ST131 H30Rx), the two causative agents were indistinguishable.

Patient F was a 72-year-old female with cystitis followed by urosepsis 181 days later (HOS26; ST131 H30R; 53 SNPs or 20 SNPs without recombination), followed by urosepsis 101 days later (HOS27; ST131 H30R; 61 or 27 SNPs) and then a subsequent sample was taken 3 days later (HOS28; ST131 H30R; 62 or 26 SNPs). The vast majority of SNPs were a result of recombination, which is 50–100 times more likely to occur than mutations [136], and occurred in aerobactin biosynthesis protein iucC and iron transport system genes sitABC. However, three point mutations with potential change to function were identified in all urosepsis isolates: R18L in capsule protein KpsM, R268L in molybdoenzyme biosynthesis protein MoeA and M58R in molybdoenzyme chaperon protein YcdY. Intriguingly, HOS50 (also ST131 H30R), originating from a 50-year-old patient presenting with pyelonephritis 21 days prior to patient F’s initial presentation, also possessed these three precise amino acid substitutions produced by the same SNPs. These identical substitutions may be indicative of a shared source, particularly as both patients resided in the same postcode, or may be examples of pathoadaptive mutations that increase fitness in the upper urinary tract. However, no recombination events were detected in HOS50.

Lastly, patient K was a 2-year-old female who presented with urosepsis (HOS41; ST69) and subsequent urosepsis 100 days later (HOS42; ST69; 13 SNPs). Similar to isolates derived from patient B, most SNPs occurred within intergenic regions (Fig. 9); however, R133L in yersiniabactin protein ybtT and R337S in K+/H+ antiporter CvrA may have incurred functional changes. Future characterization of all these SNP-mediated mutations is required to ascertain any functional changes.

Supplementary Data

Funding information

This work was funded by the Australian Centre for Genomic Epidemiological Microbiology (Ausgem), a collaborative partnership between the NSW Department of Primary Industries and the University of Technology Sydney.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Max L. Cummins from the University of Technology Sydney for his bioinformatic pipelines and assistance in their use.

Author contributions

D. L. contributor roles: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software, validation, visualization. C. J. R. contributor roles: formal analysis, methodology, software. T. K. contributor roles: data curation, resources. V. M. J. contributor roles: investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation, writing – original draft. S. P. D. contributor roles: conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, supervision. All authors had a role in writing – review and editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest

Ethical statement

The project was approved by Charles Sturt University and Sydney West Area Health Service research ethics committees. Since clinical information for patients with UTIs was provided anonymously by clinicians, patient consent was not required.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AMR, antimicrobial resistance; ARG, antimicrobial gene; CC, clonal complex; EAEC, enteroaggregative Escherichia coli; ESBL, extended-spectrum β-lactamase; ExPEC, extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli; IS, insertion sequence; MDR, multidrug resistant; MDS, multidimensional scaling; MGE, mobile genetic element; MLST, multilocus sequence typing; NSW, New South Wales; PAI, pathogenicity island; ST, sequence type; UTI, urinary tract infection; VAG, virulence-associated gene; WGS, whole-genome sequencing.

All supporting data, code and protocols have been provided within the article or through supplementary data files. Nine supplementary data items are available with the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Simmering JE, Tang F, Cavanaugh JE, Polgreen LA, Polgreen PM. The increase in hospitalizations for urinary tract infections and the associated costs in the United States, 1998–2011. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofw281. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofw281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medical Technology Group Admissions of Failure: the Truth About Unplanned NHS Admissions in England ( https://mtg.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Admissions-of-Failure-2015.pdf) London: Medical Technology Group; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care Atlas 2017 - 1. Chronic Disease and Infection: Potentially Preventable Hospitalisations (www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/healthcare-variation/atlas-2017/atlas-2017-1-chronic-disease-and-infection-potentially-preventable-hospitalisations) Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care AURA 2019: Third Australian Report on Antimicrobial Use and Resistance in Human Health (www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/aura-2019-third-australian-report-antimicrobial-use-and-resistance-human-health) Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abbo LM, Hooton TM. Antimicrobial stewardship and urinary tract infections. Antibiotics. 2014;3:174–192. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics3020174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foxman B, Brown P. Epidemiology of urinary tract infections: transmission and risk factors, incidence, and costs. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:227–241. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(03)00005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manges AR, Geum HM, Guo A, Edens TJ, Fibke CD, et al. Global extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) lineages. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;32:e00135-18. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00135-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamaji R, Rubin J, Thys E, Friedman CR, Riley LW. Persistent pandemic lineages of uropathogenic Escherichia coli in a college community from 1999 to 2017. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56:e01834-17. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01834-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manges AR, Johnson JR. Reservoirs of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli . Microbiol Spectr. 2015;3:UTI-0006-2012. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.UTI-0006-2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kantele A, Lääveri T, Mero S, Häkkinen IMK, Kirveskari J, et al. Despite predominance of uropathogenic/extraintestinal pathotypes among travel-acquired extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli, the most commonly associated clinical manifestation is travelers' diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70:210–218. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russo TA, Johnson JR. Medical and economic impact of extraintestinal infections due to Escherichia coli: focus on an increasingly important endemic problem. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:449–456. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(03)00049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Epstein L, Dantes R, Magill S, Fiore A. Varying estimates of sepsis mortality using death certificates and administrative codes — United States, 1999–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:342–345. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6513a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhee C, Dantes R, Epstein L, Murphy DJ, Seymour CW, et al. Incidence and trends of sepsis in US hospitals using clinical vs claims data, 2009-2014. JAMA. 2017;318:1241–1249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daga AP, Koga VL, Soncini JGM, de Matos CM, Perugini MRE, et al. Escherichia coli bloodstream infections in patients at a university hospital: virulence factors and clinical characteristics. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2019;9:191. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dale AP, Woodford N. Extra-intestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC): disease, carriage and clones. J Infect. 2015;71:615–626. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Micenková L, Bosák J, Vrba M, Ševčíková A, Šmajs D. Human extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli strains differ in prevalence of virulence factors, phylogroups, and bacteriocin determinants. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16:218. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0835-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson TJ, Nolan LK. Pathogenomics of the virulence plasmids of Escherichia coli . MMBR. 2009;73:750–774. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00015-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peirano G, Mulvey GL, Armstrong GD, Pitout JDD. Virulence potential and adherence properties of Escherichia coli that produce CTX-M and NDM β-lactamases. J Med Microbiol. 2013;62:525–530. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.048983-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson JR, Magistro G, Clabots C, Porter S, Manges A, et al. Contribution of yersiniabactin to the virulence of an Escherichia coli sequence type 69 (“clonal group A”) cystitis isolate in murine models of urinary tract infection and sepsis. Microb Pathog. 2018;120:128–131. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hancock V, Ferrières L, Klemm P. The ferric yersiniabactin uptake receptor FyuA is required for efficient biofilm formation by urinary tract infectious Escherichia coli in human urine. Microbiology. 2008;154:167–175. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/011981-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magistro G, Hoffmann C, Schubert S. The salmochelin receptor IroN itself, but not salmochelin-mediated iron uptake promotes biofilm formation in extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) Int J Med Microbiol. 2015;305:435–445. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alam M, Bastakoti B. Therapeutic guidelines: antibiotic, version 15. Aust Prescr. 2015;38:137. doi: 10.18773/austprescr.2015.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fasugba O, Mitchell BG, Mnatzaganian G, Das A, Collignon P, et al. Five-year antimicrobial resistance patterns of urinary Escherichia coli at an Australian tertiary hospital: time series analyses of prevalence data. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0164306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicolas-Chanoine M-H, Bertrand X, Madec J-Y. Escherichia coli ST131, an intriguing clonal group. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:543–574. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00125-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Price LB, Johnson JR, Aziz M, Clabots C, Johnston B, et al. The epidemic of extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli ST131 is driven by a single highly pathogenic subclone, H30-Rx. mBio. 2013;4:e00377-13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00377-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paltansing S, Kraakman MEM, Ras JMC, Wessels E, Bernards AT. Characterization of fluoroquinolone and cephalosporin resistance mechanisms in Enterobacteriaceae isolated in a Dutch teaching hospital reveals the presence of an Escherichia coli ST131 clone with a specific mutation in parE. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:40–45. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson JR, Tchesnokova V, Johnston B, Clabots C, Roberts PL, et al. Abrupt emergence of a single dominant multidrug-resistant strain of Escherichia coli . J Infect Dis. 2013;207:919–928. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poolman JT, Wacker M. Extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli, a common human pathogen: challenges for vaccine development and progress in the field. J Infect Dis. 2016;213:6–13. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF. Secular trends in gram-negative resistance among urinary tract infection hospitalizations in the United States, 2000–2009. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:940–946. doi: 10.1086/671740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bevan ER, Jones AM, Hawkey PM. Global epidemiology of CTX-M β-lactamases: temporal and geographical shifts in genotype. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72:2145–2155. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bajaj P, Singh NS, Virdi JS. Escherichia coli β-lactamases: what really matters. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:417. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Partridge SR, Kwong SM, Firth N, Jensen SO. Mobile genetic elements associated with antimicrobial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2018;31:e00088-17. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00088-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard, M02-A10. 10th edn. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reid CJ, Wyrsch ER, Chowdhury PR, Zingali T, Liu M, et al. Porcine commensal Escherichia coli: a reservoir for class 1 integrons associated with IS26. Microb Genom. 2017;3:mgen.0.000143. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minh BQ, Schmidt HA, Chernomor O, Schrempf D, Woodhams MD, et al. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol Biol Evol. 2020;37:1530–1534. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msaa015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Croucher NJ, Page AJ, Connor TR, Delaney AJ, Keane JA, et al. Rapid phylogenetic analysis of large samples of recombinant bacterial whole genome sequences using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kallonen T, Brodrick HJ, Harris SR, Corander J, Brown NM, et al. Systematic longitudinal survey of invasive Escherichia coli in England demonstrates a stable population structure only transiently disturbed by the emergence of ST131. Genome Res. 2017;27:1437–1449. doi: 10.1101/gr.216606.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nascimento V, Day MR, Doumith M, Hopkins KL, Woodford N, et al. Comparison of phenotypic and WGS-derived antimicrobial resistance profiles of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli isolated from cases of diarrhoeal disease in England, 2015–16. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72:3288–3297. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v4: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W256–W259. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Page AJ, Cummins CA, Hunt M, Wong VK, Reuter S, et al. Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3691–3693. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hadfield J, Croucher NJ, Goater RJ, Abudahab K, Aanensen DM, et al. Phandango: an interactive viewer for bacterial population genomics. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:292–293. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Larsen MV, Cosentino S, Rasmussen S, Friis C, Hasman H, et al. Multilocus sequence typing of total-genome-sequenced bacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:1355–1361. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06094-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Joensen KG, Tetzschner AMM, Iguchi A, Aarestrup FM, Scheutz F. Rapid and easy in silico serotyping of Escherichia coli isolates by use of whole-genome sequencing data. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:2410–2426. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00008-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clermont O, Christenson JK, Denamur E, Gordon DM. The Clermont Escherichia coli phylo-typing method revisited: improvement of specificity and detection of new phylo-groups. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2013;5:58–65. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, et al. blast+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hunt M, Mather AE, Sánchez-Busó L, Page AJ, Parkhill J, et al. ARIBA: rapid antimicrobial resistance genotyping directly from sequencing reads. Microb Genom. 2017;3:mgen.0.000131. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zankari E, Hasman H, Cosentino S, Vestergaard M, Rasmussen S, et al. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:2640–2644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]