Abstract

Background

Ovarian abscesses, which occur mostly in sexually active women via recurrent salpingitis, occur rarely in virginal adolescent girls. Here, we present a case of an ovarian abscess in a virginal adolescent girl who was diagnosed and treated by laparoscopy.

Case presentation

A 13-year-old healthy girl presented with fever lasting for a month without abdominal pain. Computed tomography scan and magnetic resonance imaging indicated a right ovarian abscess. Laparoscopic surgery revealed a right ovarian abscess with intact uterus and fallopian tubes. The abscess was caused by Staphylococcus aureus. The patient recovered completely after excision of the abscess, followed by antibiotic treatment.

Conclusions

Ovarian abscess may occur in virginal adolescent girls; Staphylococcus aureus, an uncommon species causing ovarian abscess, may cause the infection.

Keywords: Ovarian abscess, Pelvic inflammatory disease, Staphylococcus aureus, Virginal girl, Case report

Background

Ovarian abscess (OA), a form of tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA), is a complication of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), which most often occurs in sexually active women via recurrent salpingitis [1]. Hence, OA is rare in virginal adolescent girls [2]. Since torsion of the OA, rupture leading to sepsis, and infertility may occur, quick diagnosis and laparoscopic treatment is strongly recommended [1, 2]. Here, we present a case of OA in a virginal adolescent girl who was treated by laparoscopy.

Case presentation

A 13-year-old healthy virginal adolescent girl was referred to the university hospital by a local doctor after she presented with persistent fever (up to 39 °C for a month) without any other symptoms. Laboratory data showed a white blood cell (WBC) count of over 10.0 × 103/µL and a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of approximately 7.0 mg/dL. The patient had been treated with oral amoxicillin and tosufloxacin for 2 weeks based on a suspected bacterial infection; however, the blood cultures performed on the day of referral to the university hospital were negative.

Besides a body temperature of 37.4 °C, physical examination by the pediatric physician in the university hospital revealed no abnormalities. The patient had no history of dental treatment, trauma, or cystitis. Laboratory data showed a WBC count of 8.1 × 103/µL, a hemoglobin level of 11.5 g/dL, a platelet count of 29.5 × 103/µL, and a CRP level of 6.4 mg/dL. Additionally, assays for soluble interleukin-2 receptor and autoantibodies, indicative of malignant lymphoma and collagen disease, respectively, were negative. Serological tests for human immunodeficiency virus and tuberculosis were also negative. The rapid antigen test for group A streptococci and polymerase chain reaction test for coronavirus disease 2019 were also negative.

Trans-abdominal ultrasound showed a pelvic mass measuring 6 cm; therefore, gynecologists were consulted. Menarche had occurred at the age of 12 years. The menstrual cycle was irregular, and the development of breast and pubic hair was in Tanner stage II. The patient had a height of 150 cm and body weight of 35 kg. The patient had no history of sexual activity, sexual abuse, or transvaginal maneuver; therefore, bimanual examination was not applicable to this patient.

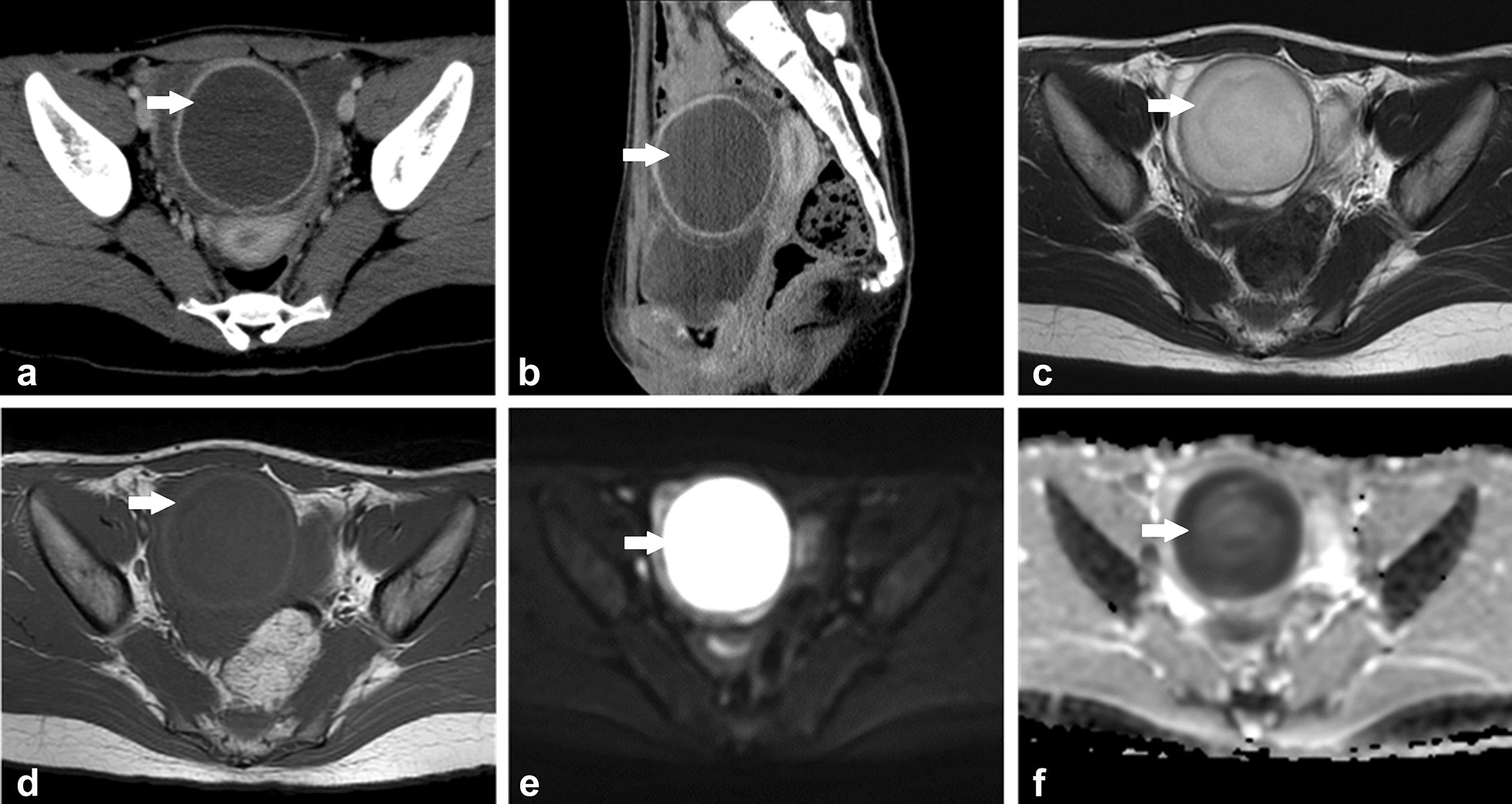

Computed tomography (CT) scan was performed initially to evaluate the blood supply into the ovarian tumor and evaluate for other sources of fever. The scan revealed a unilateral and unilocular ovarian mass with a thick, uniform, enhancing wall. Additionally, the fluid in the mass was dense. These observations suggested the presence of OA (Fig. 1a, b). Pyosalpinx was not confirmed. CT scan revealed no other possible origin of fever. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed intermediate signal intensity on T2-weighted images, low signal intensity on T1-weighted images, high signal intensity on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), and the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) indicated low diffusion. These observations also indicated the presence of OA (Fig. 1c–f).

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography scan shows a unilateral and unilocular ovarian mass with dense fluid and a thick, uniform, enhancing wall in a transverse section image (a) and a sagittal image (b). Magnetic resonance imaging shows a right ovarian mass with intermediate signal intensity on T2-weighted image (c), low signal intensity on T1-weighted image (d), high signal intensity on diffusion-weighted image (e), and low diffusion, indicated by the apparent diffusion coefficient (f). The white arrow shows the abscess

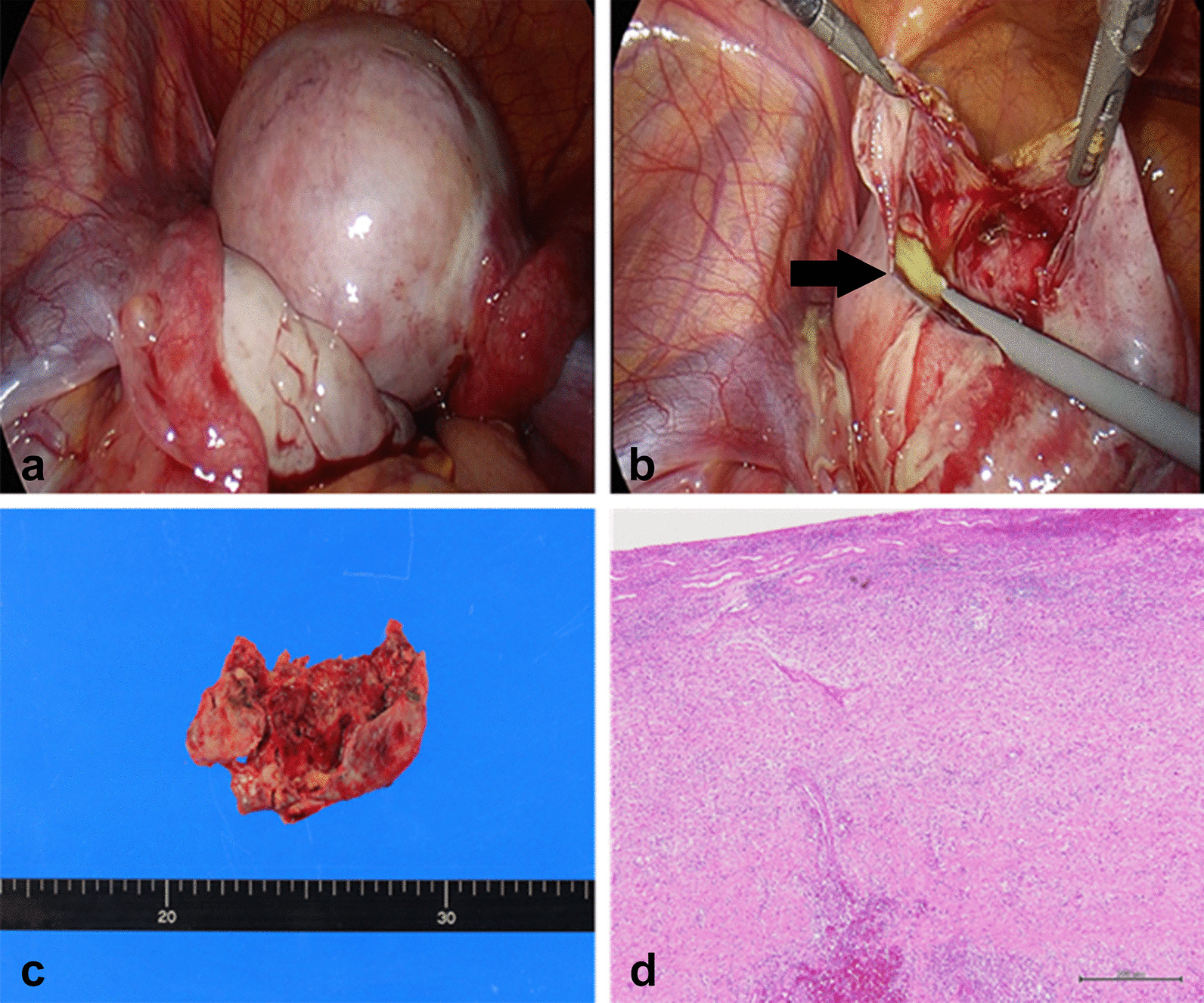

Taking into consideration the risk of ovarian torsion and acute sepsis due to persistent fever, laparoscopic surgery, involving four incisions to insert four ports, was performed for confirmation and excision of the abscess. Laparoscopy revealed a right ovary, swollen by 5 cm, with an intact fallopian tube (Fig. 2a); an intact left ovary with intact fallopian tube; and a small amount of ascites. Puncturing of the swollen right ovary revealed internal pus, which confirmed the diagnosis of OA. The pus was collected for bacterial culture and the abscess was excised without any substantial compromise to the ovary (Fig. 2b, c). We performed pelvic washing. The postoperative laboratory data 3 days after surgery showed a CRP level of 13.8 mg/dL. The patient received intravenous cefmetazole for 5 days at a dose of 2 g/day to prevent recurrence of the infection. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged 6 days after surgery; the CRP level on the day of discharge was 4.12 mg/dL. The bacterial culture of the abscess showed the presence of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. Oral cefaclor at a dose of 900 mg/day was continued for 14 days after intravenous cefmetazole. The histological findings revealed granulation tissue with neutrophilic infiltration, suggesting abscess formation in the ovary, without indication of basal ovarian tumor (Fig. 2d). Malignancy was not observed. Finally, CRP level was within the normal range, and MRI performed 1 month after surgery showed no recurrence of OA.

Fig. 2.

Laparoscopy shows the right ovarian abscess with intact fallopian tube and intact left ovary with intact fallopian tube before excision (a) and during excision (b, c). The black arrow shows the abscess. The histological findings revealed granulation tissue with neutrophilic infiltration, suggesting abscess formation in ovary, without indication of basal ovarian tumor (scale bar: 500 µm) (d)

This study did not require ethics approval by the institutional review board at Fukushima Medical University. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and her mother for the publication of the report.

Discussion and conclusions

The present case demonstrates that OA can occur in a healthy virginal adolescent girl. Literature review (up to 2019) identified 18 cases of virginal girls and women with TOA or OA (Table 1) [2–7], which suggests that OA occurs rarely in virginal girls. The cause of TOA in this patient group is often unclear; however, virginal girls have been speculated to have comorbidities, such as vaginal voiding causing ascending infection, gastrointestinal tract translocation, congenital genitourinary anomalies, previous pelvic surgery, and bacteremia from skin wounds, which predispose them to TOA [1, 2]. Physicians should therefore consider the possibility of TOA in virginal girls presenting with fever.

Table 1.

Review of the tubo-ovarian abscess cases reported to date in virginal girls and women.

(Revised from Cho et al. [2])

| Case No. | Authors | Year of case publication | Age (years) | Symptoms | Preoperative diagnosis | Postoperative diagnosis | Surgical procedure | Concomitant events as possible causal factors | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Teng et al. | 1996 | 47 | Abdominal pain, fever | TOA or peri-appendiceal abscess | TOA | Hysterectomy, BSO, appendectomy | Bacteremia after cat scratch | Pasteurella multocida |

| 2 | Moore et al. | 1999 | 15 | Abdominal pain, fever | Pelvic mass | TOA | LSO | Recurrent UTI | Escherichia coli |

| 3 | Leong and Bowditch | 2001 | 23 | Abdominal pain | Ovarian tumor | TOA | Laparoscopic RSO | Unknown | Negative |

| 4 | Fumino et al. | 2002 | 13 | Abdominal pain, fever | TOA | TOA | LSO | Vaginoplasty for cloacal anomaly | Not mentioned |

| 5 | Dogan et al. | 2004 | 19 | Abdominal pain | Ovarian tumor | TOA | Wedge resection of ovary | Ascending infection from the lower genital tract | Escherichia coli, etc |

| 6 | Arda et al. | 2004 | 15 | Abdominal pain, fever | TOA | TOA | Laparoscopic abscess drainage | Concomitant UTI | Escherichia coli |

| 7 | Hartmann et al. | 2009 | 16 | Abdominal pain, fever | Inflammation of the ovary | TOA | Laparoscopy for diagnosis | Crohn’s disease | Bacteroides uniformis, etc |

| 8 | Hartmann et al. | 2009 | 12 | Abdominal pain, fever | Large dominant ovarian cyst | TOA | Laparoscopy for diagnosis | Recurrent UTI | Escherichia coli |

| 9 | Gensheimer et al. | 2010 | 20 | Abdominal pain, fever | Complex hemorrhagic cyst | TOA | RSO, small bowel resection, appendectomy | Genitourinary or gastrointestinal spread | Abiotrophia spp., etc |

| 10 | Ashrafganjooei et al. | 2011 | 24 | Abdominal pain, fever | Necrotic pelvic tumor or pelvic abscess | TOA | TAH, RSO | Unknown | Mixed organisms |

| 11 | Tuncer et al. | 2012 | 30 | Abdominal pain, fever | TOA | TOA | Percutaneous drainage | Sigmoid diverticulitis | Escherichia coli, etc |

| 12 | Sakar et al. | 2012 | 13 | Abdominal pain, menstrual disorder | Ovarian tumor | TOA | Left salpingectomy | Ascending infection from the lower genital tract | Not mentioned |

| 13 | Simpson-Camp et al. | 2012 | 14 | Abdominal pain, fever | Borderline mucinous tumor | TOA | Laparotomy for diagnosis | Ascending infection from the lower genital tract | Streptococcus viridans |

| 14 | Goodwin et al. | 2013 | 13 | Abdominal pain | Bowel compromise | TOA | Abscess drainage | Bacterial bowel translocation | Escherichia coli |

| 15 | Cho et al. | 2017 | 21 | Abdominal pain, fever | Hemorrhagic corpus luteal cyst | OA | Abscess drainage, appendectomy | Unknown | Negative |

| 16 | Alsahabi et al. | 2017 | 19 | Abdominal pain, fever | Tubo-ovarian malignant tumor | TOA | Percutaneous drainage | Unknown | Escherichia coli, etc |

| 17 | Stortini et al. | 2017 | 14 | Acute urinary retention | TOA | TOA | Percutaneous drainage | Obstructive lesions in the genital tract due to labial agglutination | Streptococcus anginosus, etc |

| 18 | Mills et al. | 2018 | 13 | Abdominal pain, fever | TOA | TOA | Laparoscopic abscess drainage | Bacterial translocation secondary to chronic appendicitis | Streptococcus constellatus |

| 19 |

Murata et al. (present case) |

2021 | 13 | Fever | OA | OA | Laparoscopic abscess resection | Unknown | Staphylococcus aureus |

BSO bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, LSO left salpingo-oophorectomy, OA ovarian abscess, RSO right salpingo-oophorectomy, TAH total abdominal hysterectomy, TOA tubo-ovarian abscess, UTI urinary tract infection

Quick diagnosis of OA is desired because it increases the risk of torsion and sepsis. When OA is suspected, quick treatment is required to prevent adverse outcomes [1, 2]. In the present case, laparoscopic surgery was selected due to an increased risk of torsion and sepsis; the fever had persisted despite antibiotics treatment for two weeks. However, the rarity and uncommon clinical symptoms of OA in virginal girls may lead to misdiagnosis (Table 1). CT scan and MRI may help in the preoperative diagnosis of OA in virginal adolescent girls. The majority of TOA cases have been reported to be unilateral (73%) and multilocular (89%) with the presence of dense fluid (95%); a thick, uniform, enhancing wall (95%); thickening of the mesosalpinx (91%); pelvic fat infiltration (91%); thickening of the uterosacral ligaments (64%); and pyosalpinx (50%) [8]. Additionally, TOA has been reported to show low or intermediate signal intensity on T2-weighted images, high signal intensity on DWI, and low diffusion on ADC in MRI [9]. Notably, MRI with DWI has been reported to have higher accuracy than CT scan and MRI without DWI [9]. Therefore, physicians should evaluate CT scan and MRI for preoperative diagnosis of an ovarian mass in virginal girls, as was done in the present case.

To the best of our knowledge, the present case is the first case of an OA caused by S. aureus in a virginal girl (Table 1). PID, including TOA, is commonly caused by ascending genital infections (Escherichia coli and Enterococcus spp) [2]. However, the patient in the present case was sexually inactive, and OA was caused by S. aureus, which has been rarely known to cause TOA. To date, only two cases of TOA caused by S. aureus in non-virginal adult women have been reported; one was an acute TOA after intrauterine device insertion and the other was after tubal ligation [10]. In the present case, since the fallopian tubes were intact and the patient had no episode of transvaginal maneuver, the source of the infection could have been via the bloodstream. S. aureus is one of the most common gram-positive bacteria responsible for sepsis. Moreover, the patient had no history of dental treatment, trauma, or compromised immune system; therefore, no alternative source of infection was identified. The present case suggests that physicians should consider the possibility of uncommon bacterial species as the causative agents for OA among virginal girls and that these species may cause infection from an unknown origin via the bloodstream.

In conclusion, OA may occur in virginal adolescent girls. S. aureus, a rare species causing OA, may be the underlying cause of infection via the bloodstream. Physicians should consider the possibility of OA among virginal girls and should carefully evaluate for underlying causes, including the bacterial species and the possible source of bacterial infection.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ADC

Apparent diffusion coefficient

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CT

Computed tomography

- DWI

Diffusion-weighted imaging

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- OA

Ovarian abscess

- PID

Pelvic inflammatory disease

- TOA

Tubo-ovarian abscess

- WBC

White blood cell

Authors' contributions

TM contributed to the Patient management, Data collection, and Manuscript writing. YE, SF, AO, SS, TW, TT, and KF contributed to the Patient management and Manuscript editing. YK contributed to the Histological analysis and Manuscript editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work did not receive any specific grant from the funding agencies.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article, as this is a case report.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study did not require ethical approval by the institutional review board at Fukushima Medical University.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and her mother for the publication of the report.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hakim J, Childress KJ, Hernandez AM, Bercaw-Pratt JL. Tubo-ovarian abscesses in nonsexually active adolescent females: a large case series. J Adolesc Health. 2019;65:303–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cho H-W, Koo Y-J, Min K-J, Hong J-H, Lee J-K. Pelvic inflammatory disease in virgin women with tubo-ovarian abscess: a single-center experience and literature review. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017;30:203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartmann KA, Lerand SJ, Jay MS. Tubo-ovarian abscess in virginal adolescents: exposure of the underlying etiology. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22:e13–e16. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodwin K, Fleming N, Dumont T. Tubo-ovarian abscess in virginal adolescent females: a case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:e99–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alsahabi JA, Aldakhil LO, Alobaid AS. Tubo-ovarian abscess in non sexually active adolescents. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2017;29:20150051. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Stortini B, Dural O, Kielly M, Fleming N. Tubo-ovarian abscess in a virginal adolescent with labial agglutination due to Lichen sclerosus. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017;30:646–648. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mills D, Sharon B, Schneider K. Streptococcus constellatus tubo-ovarian abscess in a non-sexually active adolescent female. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34:e100–e101. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiller N, Sella T, Lev-Sagi A, Fields S, Lieberman S. Computed tomographic features of tuboovarian abscess. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:203–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan H, Wang T-T, Ren G, Fu H-L, Wu X-R, Chu C-T, et al. Characterization of tubo-ovarian abscess mimicking adnexal masses: Comparison between contrast-enhanced CT, 18F-FDG PET/CT and MRI. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;57:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2017.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singhal SR, Chaudhry P, Singhal SK. Staphylococcus tubo-ovarian abscess after tubal ligation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;91:79–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article, as this is a case report.