Abstract

Introduction

Dementia family caregiving may span more than a decade and places many family care partners (CPs) at risk for poor bereavement outcomes; estimates of complicated grief in bereaved dementia family CPs range from 10% to 20%. We adapted our efficacious complicated grief group therapy intervention for bereaved dementia caregivers for soon‐to‐be bereaved dementia CPs at risk for complicated grief to facilitate healthy death preparedness and eventual bereavement—pre‐loss group therapy (PLGT).

Methods

In this Stage IB pilot intervention study, we implemented and evaluated PLGT in three psychotherapy group cohorts with family CPs at‐risk for complicated grief whose person living with dementia (PLWD) had a life expectancy of 6 months or less and resided in a nursing home. PLGT is a 10‐session multi‐modal psychotherapy administered by social workers.

Results

Participants in PLGT realized significant improvement in their pre‐loss grief and in reported preparedness for the death of their family member, and participants evidenced lowered pre‐loss grief severity and improvement, as measured by facilitators. Participants also realized significant improvement in meaning making, particularly as a sense of peace and a reduction of loneliness.

Discussion

The process and treatment elements of the PLGT intervention affirm the value of specialized care for those dementia family CPs at risk for complicated grief, as the PLGT groups demonstrated a steady progression toward improvement collectively and individually. PLGT participants realized statistical and clinical improvement across pre‐loss grief measures suggesting that their risk for complicated grief risk was mitigated, and they were better prepared for the death of their PLWD.

Keywords: complicated grief, dementia family care partner, group psychotherapy, nursing home

1. BACKGROUND

Comprehensive family dementia caregiver support should include appropriate preparation for the death of the person living with dementia (PLWD). While most people navigate the loss of a family member to dementia with coping skills, social supports, and time, 10% to 20% of grievers experience a state of prolonged, ineffective mourning known as complicated grief. 1 , 2 Unlike normal grief, complicated grief is characterized by unabated maladaptive thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that obstruct adjustment. The REACH 3 and CASCADE 4 studies reported complicated grief in bereaved caregivers and called for treatment and prevention strategies to mitigate poor bereavement outcomes.

Dementia caregiving requires ongoing adjustment within the family care partner–PLWD dyad, particularly as the care partner (CP) prepares for the loss of this significant relationship. 5 , 6 An inability to accommodate relationship change and the eventual death of the PLWD predicts ineffective post‐death integration of grief. 7 , 8 , 9 Other known complicated grief risk factors in dementia caregivers include positive view of the caregiving role, perceived gratifying communication with the PLWD, high expressed affection by the CP, and high perceived caregiving burden. 10 Dementia caregiving is also associated with depression and anxiety, known risk factors for complicated grief. 11 Nursing home admission also contributes to risk for poor bereavement in high‐risk dementia CPs; those who cared for their PLWD at home evidence still higher risk upon nursing home placement. 12

A recent systematic review indicated that lack of preparedness and pre‐loss experiences are most predictive of poor bereavement outcomes and advocated for targeted support to caregivers who are at risk of adverse bereavement outcomes. 13 Our earlier work assessing family caregivers in the final months before the death of their PLWD revealed those caregivers who experienced the family member's decline as traumatic, who strongly expressed concern for loss of the caregiver role, who reported unavailable support, and exhibited difficulties anticipating a new life reported inadequate death preparation and difficulty making meaning of the illness and death. 14 While meeting the educational needs of most family CPs, caregiver support groups, such as those provided by the Alzheimer's Association, are insufficient to prepare for the death of the PLWD in CPs at risk for complicated grief. Complicated grief requires psychotherapeutic intervention and persons with complicated grief are known to have suboptimal response to groups that are merely psychoeducational and supportive. 15 , 16

The purpose of this study was to develop, implement, and evaluate a theoretically grounded group psychotherapy intervention to attenuate the risk of complicated grief and facilitate constructive, healthy grief in family CPs of PLWD who are at risk for complicated grief.

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT

Systematic review: The authors reviewed the literature regarding prevalence of risk for complicated grief in family care partners (CPs) of persons living with dementia (PLWD), including our own national survey of family CPs awaiting death of their PLWD. We also reviewed the literature on behavioral interventions to address complicated grief in this population, with relevant citations.

Interpretation: We developed, implemented, and evaluated pre‐loss group therapy (PLGT) in three nursing homes with dementia family CPs at risk for complicated grief. Our findings indicate that PLGT reduced risk for complicated grief and improved CPs’ preparedness for the death of their PLWD.

Future directions: This study is the first known application of proven therapeutic strategies to address complicated grief applied to high‐risk dementia CPs prior to PLWD death to mitigate complicated grief. If proven to be effective in larger studies, PLGT will be delivered to active CPs of living persons with dementia at risk for complicated grief in nursing homes and hospices.

2. PRIOR INTERVENTION RESEARCH

A systematic review and companion paper outlining the review protocol by Wilson et al. was published “to synthesize the existing evidence regarding the impact of psychosocial interventions to assist adjustment to grief, pre‐ and post‐bereavement, for family carers of people with dementia.” 17 , 18 The protocol outlined criteria that included caregivers of PLWD who were more than 65 years old and encompassed interventions including support, counseling, education, workshops, and self‐care but excluded medication interventions. This systematic review identified three studies for final inclusion—each used pre‐loss interventions to support caregivers with the grief in the death of a PLWD. Findings indicated caregivers are typically unprepared for pre‐loss experiences and are at higher risk for poor bereavement outcomes, and recommend the development of support interventions for caregivers who are at risk of adverse bereavement. The review concluded that minimal research had been done regarding non‐medical interventions to minimize complicated grief in dementia caregivers.

Subsequently, Meichsner et al. initiated analysis of cognitive‐behavioral therapy with grief‐focused content for clients who were family caregivers reporting “grief and loss” as therapy goals but who had not been clinically evaluated for risk of complicated grief. 19

3. METHOD

3.1. Intervention development: translating complicated grief group therapy into pre‐loss group therapy

In our previous research, we developed complicated grief group therapy as a group‐therapy adaptation of Shear's complicated grief therapy for individual psychotherapy, the only treatment for complicated grief with established effectiveness. 20 , 21 Group interventions bring the additional benefits of shared experience, reduction of social isolation, and cost savings to the care of persons with complicated grief. We administered complicated grief group therapy to bereaved dementia family CPs in a randomized controlled trial and demonstrated statistically and clinically significant improvement across grief measures. We evaluated detailed narratives and the individual progress of grief change in participants to identify complicated grief group therapy treatment elements with potential to attenuate complicated grief if applied to high‐risk family dementia CPs prior to the death of their PLWD. 22

As we developed complicated grief group therapy, two theoretical frameworks contributed to our understanding of complicated grief and our conceptualization of grief change. First, current understanding of complicated grief is informed by the Dual‐Process Theory. 23 , 24 This highly substantiated model of grief adjustment consists of three components: loss‐orientation (LO) coping, restoration‐orientation (RO) coping, and oscillation between the two. LO coping encompasses thoughts and emotions about the lost relationship. RO coping describes life adjustments the griever needs to face. Oscillation is a cognitive and emotional overlapping of LO and RO coping whereby the bereaved confronts the loss, alternating with periods of setting aside thoughts of the loss but facing the changed life. 25 , 26 Known complicated grief risk factors contribute to ineffective LO or RO coping. We suggest that complicated grief group therapy restored constructive grief through carefully designed intervention elements that facilitated LO and RO coping and mitigated the effect of risk factors. Second, Meaning Reconstruction Theory, developed by Neimeyer and Park, 27 , 28 , 29 contributes an explanatory model of mourning: meaning‐making. Meaning‐making refers to the capability of grievers to accept the loss, realize growth, and reorganize personal identity in the context of loss. 30 Considerable research has supported meaning‐making as a mediator in both complicated grief and constructive grief. 31 , 32 , 33 Our prior research on the process of complicated grief group therapy incorporated Meaning Reconstruction Theory to measure the engagement of the LO and RO targets. We investigated the progression of therapeutic change in complicated grief group therapy participants 22 , 34 using the Meaning of Loss Codebook, 35 a coding system that operationalizes the meanings grievers ascribe to the death. Neimeyer's research group has since validated the Grief and Meaning Reconstruction Inventory (GMRI), which detects change in meaning‐making. 36

We adapted the complicated grief group therapy intervention for complicated grief in bereaved dementia caregivers for soon‐to‐be bereaved dementia caregivers at risk for complicated grief to facilitate healthy death preparedness and eventual bereavement—pre‐loss group therapy (PLGT). We used empirically validated procedures for developing psychosocial intervention manuals 37 , 38 and created PLGT participant manuals and facilitator manuals. This positioned our progress in the National Institute on Aging Stage Model for Behavioral Intervention Development as a Stage IB investigation‐feasibility and pilot testing of an adapted existing intervention, with Stage III preliminary evaluation in community setting with community‐based providers. 39

PLGT is 10 weeks in duration with 120‐minute sessions. Intervention elements focus on the relationship between the family CP and their PLWD, how memories of life together and illness are interpreted, and strategies for creating a life without the PLWD. PLGT treatment elements include psychoeducation, motivational interviewing, cognitive‐behavioral techniques, prolonged‐exposure techniques, memory work, mindfulness, self‐care, and meaning‐reconstruction activities. Additionally, participants invite a supportive other of their choosing to attend three of the sessions. Intervention activities in later sessions are designed to optimize meaning‐making of the relationship, of caregiving, and the integration of memories of the PLWD (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Brief summary of pre‐loss group therapy sessions

| Session | Activity | Theoretical approach | Therapeutic approach | Treatment goals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Psychoeducation The story of your family member—the story of the illness |

Joining Dementia education |

Normalize caregiving stress Increase socialization/reduce isolation |

|

|

You as a caregiver The story of what is coming (1st) |

Loss‐oriented coping | Exposure therapy | Situational anticipation | |

| Mindfulness education & meditation practice | Mindfulness‐based stress reduction (MBSR) | Mindfulness | Self‐care skills | |

| Explanation of homework, distress scoring | Distress tolerance/emotion regulation | Learn self‐monitoring | ||

| 2 | Check in You as a caregiver‐ and homework review |

Joining Gain Support |

Personal accountability | |

|

Developing goals Preparedness goals & self‐care goals |

Restoration‐Oriented coping | Motivational interviewing |

Preparedness Self‐care |

|

| Meditation practice | MBSR | Mindfulness | Self‐care skills | |

| 3 | Check in You as a caregiver‐and homework review‐group feedback |

Joining Gain Support |

Personal accountability | |

| Supportive Other visit #1 | Increase socialization/reduce isolation | |||

| Working with emotions/thoughts/body sensations | Loss‐oriented & restoration‐ oriented coping |

CBT Relationship‐framing |

||

| Integrated grief discussion | Psychoeducation |

Situational anticipation Preparedness |

||

| Preparedness & self‐care goals for next session | Restoration‐oriented coping | Motivational interviewing |

Preparedness Self‐care |

|

| Meditation | MBSR | Mindfulness | Self‐care skills | |

| 4 | Check in You as a caregiver‐and homework review‐group feedback |

Joining Gain Support |

Personal accountability | |

| The story of what is coming (2nd)‐group feedback | Loss‐oriented coping | Exposure therapy | Situational anticipation | |

| Pleasant memory worksheet and pictures | Meaning reconstruction‐memory work | Meaning‐making | Integrated memory of PLWD | |

| Working with emotions/thoughts/body sensations | Loss‐oriented & restoration‐oriented coping |

CBT Relationship‐framing |

||

| Preparedness & self‐care goals for next session | Restoration‐oriented coping | Motivational interviewing |

Preparedness Self‐care |

|

| Meditation | MBSR | Mindfulness | Self‐care skills | |

| 5 | Check in You as a caregiver‐and homework review‐group feedback |

Joining Gain Support |

Personal accountability | |

| The story of what is coming (3)‐group feedback | Loss‐oriented coping | Exposure therapy | Situational anticipation | |

| Working with emotions/thoughts/body sensations | Loss‐oriented & restoration‐oriented coping |

CBT Relationship‐framing |

||

| Preparedness & self‐care goals for next session | Restoration‐oriented coping | Motivational interviewing |

Preparedness Self‐care |

|

| Meditation | MBSR | Mindfulness | Self‐care skills | |

| 6 | Check in You as a caregiver‐and homework review‐group feedback |

Joining Gain Support |

Personal accountability | |

| Imaginal conversation for ½ of group‐group feedback | Exposure therapy | |||

| Working with emotions/thoughts/body sensations |

CBT Relationship‐framing |

|||

| Preparedness & self‐care goals for next session | Restoration‐oriented coping | Motivational interviewing |

Preparedness Self‐care |

|

| Meditation | MBSR | Mindfulness | Self‐care skills | |

| 7 | Check in You as a caregiver‐and homework review/review of imaginal conversations completed |

Joining Gain Support |

Personal accountability | |

| Imaginal conversation for 2nd ½ of group‐group feedback | Exposure therapy | |||

| Working with emotions/thoughts/body sensations | Loss‐oriented & Restoration‐oriented coping |

CBT Relationship‐framing |

||

| Preparedness & self‐care goals for next session | Restoration‐oriented coping | Motivational interviewing |

Preparedness Self‐care |

|

| Meditation | MBSR | Mindfulness | Self‐care skills | |

| 8 | Check in You as a caregiver‐and homework review/review of imaginal conversations completed |

Joining Gain support |

Personal accountability | |

| Supportive Other visit #2 | Increase socialization/reduce isolation | |||

| Difficult memories work sheet and pictures | Meaning reconstruction‐memory work | Meaning‐making | Integrated memory of PLWD | |

| Education on integrated memory | ||||

| Preparedness & self‐care goals for next session | Restoration‐oriented coping | Motivational interviewing |

Preparedness Self‐care |

|

| Meditation | MBSR | Mindfulness | Self‐care skills | |

| 9 | Check in You as a caregiver‐and homework review‐group feedback |

Joining Gain Support |

Personal accountability | |

| The story of what is coming (4) [emphasis‐how you want to look back on it] group feedback | Loss‐oriented coping | Exposure therapy | Situational anticipation | |

| Integrated memories work sheet and pictures | Meaning reconstruction‐memory work | Meaning‐making | Integrated memory of PLWD | |

| Preparedness & self‐care goals for next session | Restoration‐oriented coping | Motivational interviewing |

Preparedness Self‐care |

|

| Meditation | MBSR | Mindfulness | Self‐care skills | |

| 10 | Check in You as a caregiver‐and homework review‐group feedback |

Joining Gain Support |

Personal accountability | |

| Bringing the memory of the PLWD forward in your life | Meaning reconstruction‐memory work | Meaning‐making | Integrated memory of PLWD | |

| Participant accomplishments and preparedness | Affirmation |

Affirmation of preparedness Self‐care |

||

| Preparedness & self‐care goals for the future | Restoration‐Oriented coping | Motivational interviewing |

Preparedness Self‐care |

|

| Supportive Other visit #3 | Increase socialization/reduce isolation | |||

| Meditation | MBSR | Mindfulness | Self‐care skills |

Abbreviation: PLWD, person living with dementia.

3.2. Setting

Three nursing homes were selected for inclusion in this study, one veterans’ home, one for‐profit facility, and one not‐for‐profit facility with a majority of residents funded by Medicaid. All facilities were highly rated on Medicare.gov and were located in a metropolitan location in the western United States.

3.3. Participants

Participants were family CPs at risk for complicated grief with a family member diagnosed with dementia having a life expectancy of less than 6 months who resided in one of the facilities included in this study. We focused on family CPs with PLWD residents nearing death as they were temporally closer to their grief/death preparedness experience, permitting timely post‐death follow‐up. Residents may or may not be enrolled in hospice care. Because palliative care and hospice care are underused for residents with dementia in long‐term care, 40 and because even meticulous hospice care does not include group support for family CPs, we determined that hospice participation would not likely impact our study.

3.4. Recruitment

Facility leadership (medical director, social worker, and director of nursing) identified potential family caregiver participants based on these inclusion criteria: (1) resident diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease or related disorder, (2) life expectancy as positive response to, “Would you be surprised if this resident died in the next 6 months?,” and (3) family CP proximity to facility permitting participation. Potential PLGT participants received an invitation phone call from the study research assistant. Interested individuals were invited to a pre‐screening interview with the research assistant in person at the facility. Those who met the final inclusion criteria, (4) minimum score of 4 on pre‐loss version of the Brief Grief Questionnaire 41 (p‐BGQ), and (5) positive scores on four of nine risk factors (low health status, depression, anxiety, perceived burden, non‐acceptance, multiple losses, life stressors, lack of available social supports, self‐reported insufficient knowledge of illness) qualified. The research assistant reviewed the informed consent document, and those who consented were enrolled in PLGT. Supportive others completed a separate consent document.

3.5. Participant assessment

Participants were assessed by the research assistant on demographic information, the pre‐loss Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG‐r), 42 the preparedness question, 3 self‐reported health status, 43 anxiety (Generalized Anxiety Disorders [GAD‐2] scale 44 ), depression (Patient Health Questionnaire 45 [PHQ‐2]), the Inventory of Stressful Life Events Scale 46 (ISLES‐sf), and the GMRI. 47 The grief measures selected for this study, the BGQ and ICG‐r, are well‐validated, reliable measures that we adapted for pre‐loss assessment in our earlier national survey of dementia family CPs. We were particularly interested in discerning change in participants’ ability to navigate the stress of caregiving and selected the ISLES, as is it focused on the relational grief stress. Meaning‐making, as assessed by the GMRI, includes five domains: continuing bonds, personal growth, sense of peace, emptiness and meaninglessness, and valuing life. Meaning‐making is theoretically and clinically considered a later element of growth in grief. We wanted to explore the process of meaning‐making as participants were preparing for the death of their PLWD. Participant progress was assessed weekly by PLGT facilitators using the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale 48 to provide data triangulation across self‐report measures, clinician assessment, and participant narrative comments. Participants were reassessed after the final PLGT session by the research assistant.

As this was a pilot intervention evaluation, the principal investigator and co‐investigators served as PLGT group facilitators. Each of the three PLGT treatment cohorts was co‐facilitated by two of the three investigators. The investigators are PhD research scientists and licensed clinical social workers, each having more than 30 years of clinical experience and high qualifications in grief therapy. While introducing potential for bias, we minimized bias through prebrief and debrief at each session. We anticipated that many of the PLWD residents would die over the course of the study, either during or after the 10‐session PLGT group. An a priori therapeutic decision was made to allow participants to continue in PLGT if their PLWD died during the course of therapy, and to offer alternative care if desired by the participant. The three PLGT cohorts were conducted successively.

3.6. Treatment fidelity

To ensure PLGT facilitator competence, adherence, and quality of implementation, the three facilitators had weekly peer supervision sessions. In addition, two randomly selected sessions of each 10‐week group (six total sessions over the study) were audiotaped and evaluated for treatment fidelity using Mignogna et al.’s audit and feedback tool, 49 , 50 commonly used in clinical intervention implementation trials to assess manual adherence and clinical skills. Audio recordings were evaluated by an independent clinician evaluator familiar with complicated grief therapies, but unaffiliated with the study.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Sample

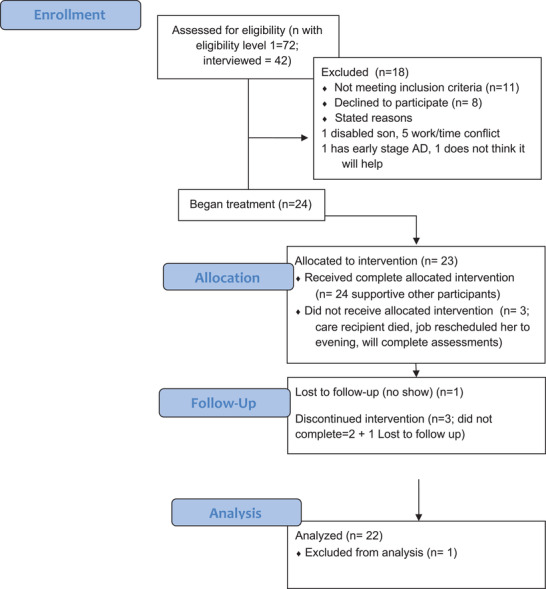

Sample recruitment, allocation, and retention are presented in Figure 1. As expected, many of the family CPs interviewed did not meet the risk threshold for expected poor bereavement. Yet, a sufficient pool was identified to justify a group therapy approach in each of the facilities. A sample of 25 family CPs were enrolled as PLGT participants. The sample had an average age of 67 years, was mostly White and female, and included 48% adult child CPs and 32% spouse CPs. The majority of participants endorsed multiple prior losses (96%) and additional life stressors (95.8%), and burden was endorsed as experienced “nearly always” by more than half of participants and “quite frequently” by another 29.2% (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

CONSORT flow diagram of participants in pre‐loss group therapy

TABLE 2.

Demographics pre‐loss group therapy

| n = 25 (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Mean ± SD | 67.0±12.7 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 3 (12.0) |

| Female | 22 (88.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 21 (87.5) |

| Black | 0 (0) |

| Latino/Hispanic | 2 (8.3) |

| Native American/Pacific Islander | 0 (0) |

| Other | 1 (4.0) |

| Missing | 1 |

| Prepare for death | |

| Not at all | 3 (14.3) |

| Somewhat | 10 (47.6) |

| Very much | 8 (38.1) |

| Missing | 4 |

| Relation to care recipient | |

| Spouse | 8 (32.0) |

| Child | 12 (48.0) |

| Sibling | 2 (8.0) |

| Parent | 0 (0) |

| Grandchild | 0 (0) |

| Grandparent | 0 (0) |

| Other | 3 (12.0) |

| Previous losses | |

| Yes | 24 (96.0) |

| No | 1 (4.0) |

| Additional stress | |

| Yes | 23 (95.8) |

| No | 1 (4.2) |

| Missing | 1 |

| Health comparison | |

| Poor | 0 (0) |

| Fair | 6 (24.0) |

| Good | 7 (28.0) |

| Very good | 8 (32.0) |

| Excellent | 4 (16.0) |

| Burden | |

| Never | 2 (8.3) |

| Rarely | 1 (4.2) |

| Sometimes | 1 (4.2) |

| Quite frequently | 7 (29.2) |

| Nearly always | 13 (54.2) |

| Missing | 1 |

| Therapy | |

| Yes | 5 (23.8) |

| No | 16 (76.2) |

| Missing | 4 |

| Medication for mood | |

| Yes | 10 (43.5) |

| No | 13 (56.5) |

| Missing | 2 |

| Depression history | |

| Yes | 14 (58.3) |

| No | 10 (41.7) |

| Missing | 1 |

| Medication abuse hHistory | |

| Yes | 1 (4.5) |

| No | 21 (95.5) |

| Missing | 3 |

| Self‐harm | |

| Yes | 10 (43.5) |

| No | 13 (56.5) |

| Missing | 2 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

4.2. Intervention findings

Intervention participation for the 10 PLGT sessions attended varied from 0 to 10 with M = 7.4, standard deviation (SD) = 3.1, and Mdn = 9 sessions. Importantly, 18 of the 25 participants attended eight or more sessions. Participants were assessed prior to the intervention (N = 25) and at the end of the study (N = 22). Paired Wilcoxon signed‐rank tests were used to examine changes in scores on the p‐BGQ, p‐ICG, ISLES, GMRI, and the depression and anxiety scales. We also assessed change in GMRI subscales to discern particular elements of change in meaning‐making. Table 3 displays the median values, Z statistics, and P statistics. All tests showed a decrease in scores at the end of study with statistically significant results at P < .05 for the GMRI subscales of peace and emptiness, GMRI total, BQG total, ICG total, and PHQ. Notably, mean change in pre‐loss grief, as measured by both the BGQ and the ICG, yielded scores below the threshold for risk of complicated grief. Participant depression scores were significantly lower, and anxiety scores approached significance, though PLGT does not directly target depression or anxiety symptoms. Mean change scores on the ISLES, which captures the stress of caregiving, also approached significance. The change in GMRI scores was significant, with achieving a sense of peace in the situation, and a reduced perception of emptiness and loneliness most impacted.

TABLE 3.

Pre–posttest change in outcome measures

| GMRI BONDS | GMRI GROWTH | GMRI PEACE | GMRI EMPTY | GMRI LIFE | GMRI TOTAL | BGQ | ICG | PHQ‐2 | GAD | ISLES | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z | −0.285 | −1.437 | −2.107 | −3.779 | −0.978 | −2.78 | −3.939 | −3.979 | −2.056 | −1.853 | −1.726 |

| Asymp. Sig. (two‐tailed) | 0.78 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| Pre median | 33 | 26 | 20 | 19 | 16 | 114 | 5 | 22 | 2 | 2 | 21 |

| Post median | 32 | 26 | 21 | 22.5 | 16 | 115.5 | 3 | 12 | 1.5 | 1 | 24 |

| Pre mean | 31.25 | 25.88 | 19.88 | 19.64 | 16.16 | 112.81 | 5.08 | 24.19 | 2.64 | 2.24 | 22.44 |

| Post mean | 31.32 | 25.95 | 20.95 | 22.65 | 15.58 | 116.46 | 2.68 | 14.41 | 1.50 | 1.45 | 23.77 |

| Pre SD | 4.21 | 4.53 | 2.32 | 3.95 | 2.34 | 9.19 | 1.85 | 9.37 | 1.58 | 1.79 | 5.08 |

| Post SD | 3.81 | 4.11 | 2.06 | 4.58 | 2.71 | 7.74 | 1.39 | 7.73 | 1.71 | 1.41 | 4.70 |

Abbreviation: BGQ, Brief Grief Questionnaire; GAD, Generalized Anxiety Disorders; GMRI, Grief and Meaning Reconstruction Inventory; ICG, Inventory of Complicated Grief; ISLES, Inventory of Stressful Life Events Scale; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; SD, standard deviation.

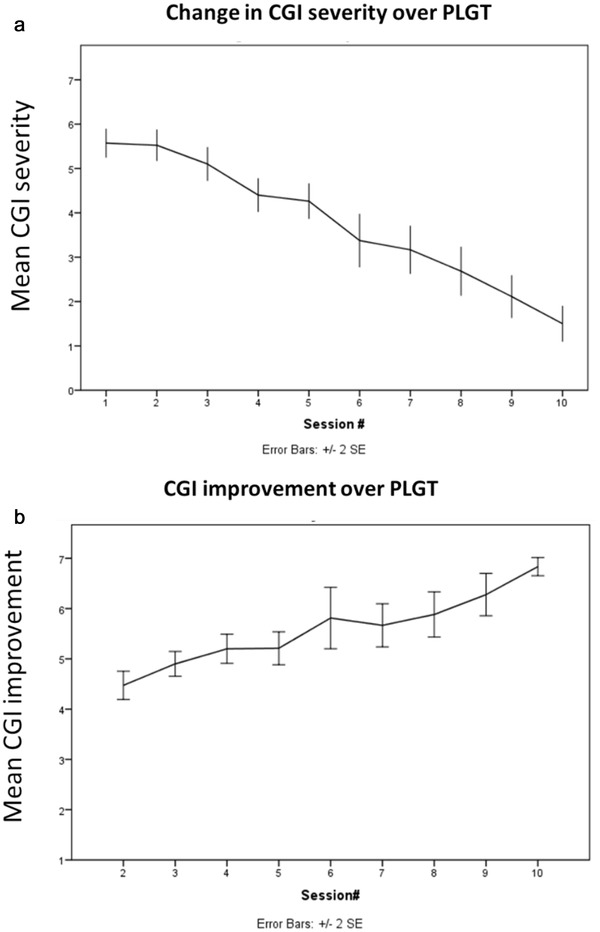

Figure 2 displays the pre‐loss grief severity and pre‐loss grief improvement as assessed by group facilitators on the CGI over the course of the 10 sessions of PLGT. Over time, there was a trend toward decrease in grief severity. A mixed‐effects model examining change over time in the PLGT sample found a significant decrease in CGI severity t (167.9) = –25.92, P < .001, time = –0.47 (standard error [SE] = 0.019). Wilcoxon rank‐sum test found similar results with improvement from comparison of first session (Mdn = 6) and tenth session (Mdn = 1), Z = –3.449, P < .001, r = 0.70. For CGI pre‐loss grief improvement, a 4 represents “no improvement”; therefore, at each session, there is an observed trend for individuals to continue improvement from week to week. For grief improvement, at session 2 (N = 19), four individuals had no improvement and eight had some improvement; at session 5 (N = 19), one individual was minimally worse and eighteen were either minimally or much improved; and by session 10 (N = 18), three were much improved and fifteen were very much improved. The pattern of change throughout PLGT mirrors that of our complicated grief group therapy studies.

FIGURE 2.

Change in clinician‐assessed grief improvement over PLGT. CGI, Clinical Global Impression scale; PLGT, pre‐loss group therapy

An independent clinician assessed facilitator treatment fidelity. Across the three PLGT groups, the three facilitators were scored at 94% mean adherence to the treatment protocol and scored at 7.8 (scale 0–8, with 0 = very poor and 8 = very good/excellent on eight skills domains) on clinical skills.

We invited post‐PLGT comments from participants in exit interviews with the research assistant. Participants were highly satisfied and appreciative of the group, despite considerable reported apprehension as the therapy began. The prevailing comment was that participants felt that PLGT prepared them for the final phases of the illness and for the death, in those participants whose PLWD has died. Most felt challenged by the initial telling of “The story of what is coming” and felt dread of the death of their PLWD, but several noted that the successive rehearsals were both practical and calming as they cognitively and emotionally anticipated the end of their family member's life. Participants appreciated the motivation to address preparedness goals and self‐care goals and commented on the benefits of closing each session with meditation. Participants were uniformly apprehensive, even avoidant of the imaginal conversation with their PLWD, yet, in exit interviews, most viewed this treatment element as the transformative moment of therapy. Several participants commented that the therapy and the support of facilitators and peers helped reduce guilt, both the guilt of visiting the nursing home every day and the guilt of feeling one was not visiting enough. One participant felt that the therapy was “too structured.” Participants also made constructive suggestions for the PLGT participant manual, which will be incorporated into the Stage III version.

Of note, we are awaiting final post‐death grief measures for the participants in these three pilot groups; as of this writing, 10 PLWD remain in the final stages of their dementia.

5. DISCUSSION

We developed PLGT as a theoretically grounded, multi‐element, manualized group psychotherapy intervention tailored to treat the unique risk for complicated grief known to exist in 10% to 20% of dementia family CPs nearing the death of their PLWD. We successfully identified and enrolled participants in three PLGT groups in three nursing homes and experienced a very low rate of attrition. The groups were well attended, and participants found the therapy acceptable, satisfying, and challenging. All completers endorsed appreciation and perceived improvement in preparedness for the death of their PLWD.

Participants in PLGT realized significant improvement in their pre‐loss grief. On the BGQ and ICG‐r, PLGT completers had scores upon end of treatment that, had they scored at that level at pretest, would have disqualified them for study enrollment. This clinical significance suggests that PLGT participants were effectively treated for pre‐loss complicated grief risk. The process and activities of the PLGT intervention affirm the value of specialized care for those dementia CPs at risk for complicated grief, as the PLGT groups demonstrated a steady progression toward improvement collectively and individually. It is important to note that this risk reduction does not mean that the PLGT participants in our study will not grieve, nor that they will not experience the distress of acute grief upon death of their PLWD; 15 rather, it suggests that they will be better equipped to experience their grief with equanimity and progress toward a sense of completion in their caregiver role.

5.1. Clinical utility

The lives of many PLWD conclude in nursing homes and, while many dementia family CPs experience burden relief upon nursing home placement, for many others, this is a profoundly distressing phase of caregiving. PLGT is efficacious and suitable for delivery in nursing homes by nursing home social workers, who are already connected to family CPs individually and in group settings such as family councils and dementia support groups. PLGT may also have application in hospice, and in community practice settings using the existing social work workforce. Given the prevalence of complicated grief risk in dementia family CPs as their PLWD near death in nursing homes, it is essential to apply and evaluate preventive strategies that assist in preparation for eventual bereavement of family CPs; and to train appropriate clinicians to provide targeted PLGT.

5.2. Study strengths and limitations

This study included evidence‐based procedures for intervention development and manualization and is now a Stage III behavioral intervention, according to the National Institutes of Health stage model. 50 The primary limitation of the study is sample size, and the lack of a control condition. The study has threats to external validity, as it is uncertain how generalizable the study findings will be to the general population of family CPs at risk for complicated grief who have not experienced the nursing home. It is possible that persons willing to participate in group therapy already have lower levels of social isolation and/or are more comfortable using social support available in groups than nonparticipants. This study sample did not reflect the diversity of dementia family CPs across the United States, and treatment response may not be generalizable to ethnic and racial groups with different needs and caregiving patterns. This research is appropriately viewed as a pilot study of the PLGT intervention.

5.3. Next steps in PLGT research

This study reports participant change in pre‐loss grief risk at the conclusion of the intervention. We are evaluating post‐death grief, and obtaining PLGT participant feedback to further refine the intervention. We are evaluating PLGT clinician training of nursing home social workers and evaluating their implementation of PLGT. We will modify the PLGT manuals for facilitators and participants and prepare for a larger pragmatic trial of PLGT. This pragmatic trial will be conducted using a stepped‐wedge design to generate a wait‐list control condition to further evaluate clinical efficacy of PLGT, and examine the feasibility and acceptability of both PLGT training of nursing home social workers, and participant adoption and adherence. If proven to be effective in attenuating poor bereavement outcomes in larger studies, PLGT could be translated into comprehensive caregiver support programs and delivered to active CPs of PLWD at risk for complicated grief in nursing homes, hospices, and through community‐based programs.

6. CONCLUSION

Dementia family caregiving may span more than a decade and places many family CPs at risk for poor bereavement outcomes. Complicated grief remains underrecognized, underdiagnosed, and undertreated in this population. Few efforts to address the prevention of complicated grief have been identified. This study is the first known application of proven therapeutic strategies to address complicated grief applied to high‐risk dementia CPs prior to PLWD death to mitigate complicated grief. PLGT brings the additional advantages of group therapy, addressing the social isolation common among long‐term family CPs. The results of this study support prior research recommending specialized preventative treatment for dementia family CPs at risk for complicated grief upon death of their PLWD.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was funded by the Alzheimer's Association grant # AARG‐17‐503706.

University of Utah Institutional Review Board approval IRB_00099770.

Supiano KP, Andersen T, Luptak M, Beynon C, Iacob E, Levitt SE Pre‐loss group therapy for dementia family care partners at risk for complicated grief. Alzheimer's Dement. 2021;7:e12167. 10.1002/trc2.12167

REFERENCES

- 1. Kersting A, Brahler E, Glaesmer H, Wagner B. Prevalences of complicated grief in a representative population‐based sample. J Affect Disord. 2011;131:339‐343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Middleton W, Burnett P, Raphael B, Martinek N. The bereavement response: a cluster analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;169(2):167‐171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hebert RS, Dang Q, Schulz R. Preparedness for the death of a loved one and mental health in bereaved caregivers of patients with dementia: findings from the REACH study. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(3):683‐693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Jones RN, Prigerson H, Volicer L, Teno JM. Advanced dementia research in the nursing home: the CASCADE study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20(3):166‐175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Noyes BB, Hill RD, Hicken BL, et al. Review: the role of grief in dementia caregiving. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2010;25(9):9‐17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lewis ML, Hepburn K, Narayan S, Kirk LN. Relationship matters in dementia caregiving. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2005;20(6):341‐347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Piiparinen R, Whitlatch CJ. Existential loss as a determinant to well‐being in the dementia caregiving dyad: a conceptual model. Dementia. 2011;10(2):185‐201. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sanders S, Corely CS. Are they grieving? A qualitative analysis examining grief in caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer's Disease. Soc Work Health Care. 2003;37(3):35‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Holland JM, Futtermans A, Thompson LW, Moran C, Gallagher‐Thompson D. Difficulties accepting the loss of a spouse: a precursor for intensified grieving among widowed older adults. Death Stud. 2013;37:126‐144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schulz R, Boerner K, Shear K, Zhang S, Gitlin LN. Predictors of complicated grief among dementia caregivers: a prospective study of bereavement. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:650‐658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barry LC, Kasl SV, Prigerson HG. Psychiatric disorders among bereaved persons: the role of perceived circumstances of death and preparedness for death. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10(4):447‐457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Givens JL, Prigerson HG, Kiely DK, Shaffer ML, Mitchell SL. Grief among family members of nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19(6):543‐550. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31820dcbe0. PMID: 21606897; PMCID: PMC3101368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nielsen MK, Neergaard MA, Jensen AB, Bro F, Guildin M. Do we need to change our understanding of anticipatory grief in caregivers? A systematic review of caregiver studies during end‐of‐life caregiving and bereavement. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;44:75‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Supiano KP, Luptak M, Andersen T, Beynon C, Iacob E, Wong B. If we knew then what we know now: the preparedness experience of pre‐loss and post‐loss dementia caregivers. Death Stud. 2020:1‐12. 10.1080/07481187.2020.1731014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Simon NM. Increasing support for the treatment of complicated grief in adults of all ages. J Am Med Assoc. 2015;313(21):2172‐2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Crunk AE, Burke LA, Robinson EM. Complicated grief: an evolving theoretical landscape. J Couns Dev. 2017;95(2):226‐233. 10.1002/jcad.12134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wilson S, Toye C, Aoun S, Slatyer S, Moyle W, Beattie E. Effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in reducing grief experienced by family carers of people with dementia: a systematic review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016;14(6):30‐41. 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-002485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wilson S, Toye C, Aoun S, Slatyer S, Moyle W, Beattie E. Effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in reducing grief experienced by family carers of people with dementia: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2017;15(3):809‐839. 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Meichsner F, Köhler S, Wilz G. Moving through predeath grief: psychological support for family caregivers of people with dementia. Dementia. 2019;18(7‐8):2474‐2493. 10.1177/1471301217748504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shear K, Frank E, Houck PR. Treatment of complicated grief: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2601‐2608. 10.1001/jama.293.21.2601. PMID: 15928281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shear MK, Reynolds CF 3rd, Simon NM, et al. Optimizing treatment of complicated grief: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(7):685‐694. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0892. PMID: 27276373; PMCID: PMC5735848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Supiano KP, Haynes LB, Pond V. The process of change in complicated grief group therapy for bereaved dementia caregivers: an evaluation using the Meaning Loss Codebook. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2017;60(2):155‐169. 10.1080/01634372.2016.1274930. PMID: 28051926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stroebe M, Schut H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: rationale and description. Death Stud. 1999;23(3):197‐224. 10.1080/074811899201046. PMID: 10848151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stroebe MS. Models of coping with bereavement. In: Stroebe M, Hansson, W, Stroebe, W, Schut, H, eds. Handbook of Bereavement Research: Consequences, Coping & Care. Washington, D. C.: American Psychological Association; 2001:375‐403.H. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shear MK. Exploring the role of experiential avoidance from the perspective of attachment theory and the dual process model. Omega. 2010;61(4):357‐369. 10.2190/OM.61.4.f.. PMID: 21058614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shear MK. Complicated grief treatment: the theory, practice and outcomes. Bereave Care. 2010;29(3):10‐14. 10.1080/02682621.2010.522373. PMID: 21852889; PMCID: PMC3156458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Neimeyer RA. Meaning Reconstruction and the Experience of Loss. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001a. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Neimeyer RA. Searching for the meaning of meaning: grief therapy and the process of reconstruction. Death Stud. 2000;24(6):541‐558. 10.1080/07481180050121480. PMID: 11503667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Park CL. Making sense of the meaning literature: an integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychol Bull. 2010;136(2):257‐301. 10.1037/a0018301. PMID: 20192563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hibberd R. Meaning reconstruction in bereavement: sense and significance. Death Stud. 2013;37(7):670‐692. 10.1080/07481187.2012.692453. PMID: 24520967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Coleman RA, Neimeyer RA. Measuring meaning: searching for and making sense of spousal loss in late‐life. Death Stud. 2010;34(9):804‐834.PMID: 24482851; PMCID: PMC3910232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Burke LA, Clark KA, Ali KS, Gibson BW, Smigelsky MA, Neimeyer RA. Risk factors for anticipatory grief in family members of terminally ill veterans receiving palliative care services. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2015;11(3‐4):244‐266. 10.1080/15524256.2015.1110071. PMID: 26654060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Burke LA, Neimeyer RA, Bottomley JS, Smigelsky MA, (2017). Prospective risk factors for intense grief in family members of veterans who died of terminal illness. Illness, Crisis & Loss, pre‐publication online: March 28, 2017 10.1177/1054137317699580 [DOI]

- 34. Supiano KP, Haynes LB, Pond V. The transformation of meaning in complicated grief group therapy for suicide survivors: treatment process analysis using the Meaning of Loss Codebook. Death Stud. 2017;41(9):553‐561. 10.1080/07481187.2017.1320339. PMID: 28426330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gillies J, Neimeyer RA, Milman E. The meaning of loss codebook: construction of a system for analyzing meanings made in bereavement. Death Stud. 2014;38(1‐5):207‐216. 10.1080/07481187.2013.829367. PMID: 24524583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gillies JM, Neimeyer RA, Milman E. The Grief and Meaning Reconstruction Inventory (GMRI): initial validation of a new measure. Death Stud. 2015;39(1‐5):61‐74. 10.1080/07481187.2014.907089. PMID: 25140919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Carroll KM, Rousanville BJ. Efficacy and effectiveness in developing treatment manuals. In: Nezu AM, Nezu CM, eds. Evidence‐Based Outcome Research: A Practical Guide to Conducting Randomized Controlled Trials for Psychosocial Interventions. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008:219‐244. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gitlin LM, Czaja SJSInLMG, Czaja SJ. Behavioral Intervention Research: Designing, Evaluating and Implementing. New York: Springer; 2016:105‐117. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Onken LS, Carroll KM, Shoham V, Cuthbert BN, Riddle M. Reenvisioning clinical science: unifying the discipline to improve the public health. Clin Psychol Sci. 2014;2(1):22‐34. 10.1177/216770261349793239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mitchell SL. Advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2533‐2540. 10.1056/NEJMcp1412652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shear K, Essock S. Brief Grief Questionnaire. University of Pittsburgh; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK. Inventory of complicated grief: a scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Res. 1995;59(1‐2):65‐79.PMID: 8771222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Idler EL, Kasl SV. Self‐ratings of health: do they also predict change in functional ability?. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1995;50(6):S344‐353.PMID: 7583813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, Lowe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(5):317‐325.PMID: 17339617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire‐2: validity of a two‐item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284‐1292. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000093487.78664.3c. PMID: 14583691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Holland JM, Currier JM, Neimeyer RA. Validation of the integration of stressful life experiences scale‐short form in a bereaved sample. Death Stud. 2014;38(1‐5):234‐238. 10.1080/07481187.2013.829369. PMID: 24524586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gillies JM, Neimeyer RA, Milman E. The grief and meaning reconstruction inventory (GMRI): initial validation of a new measure. Death Stud. 2015;39(1‐5):61‐74. 10.1080/07481187.2014.907089. PMID: 25140919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Guy W. Clinical Global Impressions: ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, Revised. National Institute of Mental Health; 1976. Unpublished CGI Scale‐assessment. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mignogna J, Hundt NE, Kauth MR, et al. Implementing brief cognitive behavioral therapy in primary care: a pilot study. Transl Behav Med. 2014;4(2):175‐183. 10.1007/s13142-013-0248-6. PMID: 24904701; PMCID: PMC4041920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cully JA, Mignogna J, Stanley MA, Malik A, Zeno D, Willcockson I. Development and pilot testing of a standardized training program for a patient‐mentoring intervention to increase adherence to outpatient HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2012;26(3):165‐172.PMID: 22248331; PMCID: PMC3326443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]