This cohort study examines the prognosis of older adults undergoing cancer surgery, including cancer, noncancer, and all-cause deaths over 5 years after surgery and to explore prognostic factors associated with cause-specific death.

Key Points

Question

How long do older adults live after receiving surgical treatment for cancer and do they die of cancer or noncancer causes?

Findings

In this population-based cohort study of 82 037 patients 70 years or older, 5 years after resection for cancer, 20% of patients died of cancer and 16% died of other causes. Low-risk cancer types, advancing age, and frailty were associated with death from noncancer causes 3 years after surgery.

Meaning

For older adults selected for cancer surgery, the relative burden of cancer deaths exceeds death from other causes, even in more vulnerable patients.

Abstract

Importance

Cancer care has inherent complexities in older adults, including balancing risks of cancer and noncancer death. A poor understanding of cause-specific outcomes may lead to overtreatment and undertreatment.

Objective

To examine all-cause and cancer-specific death throughout 5 years for older adults after cancer resection.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This population-based cohort study was conducted in Ontario, Canada, using the administrative databases stored at ICES (formerly the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences). All adults 70 years or older who underwent resection for a new diagnosis of cancer between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2017, were included. Patients were followed up until death or censored at date of last contact of December 31, 2018.

Exposures

Cancer resection.

Main Outcome and Measures

Using a competing risks approach, the cumulative incidence of cancer and noncancer death was estimated and stratified by important prognostic factors. Multivariable subdistribution hazard models were fit to explore prognostic factors.

Results

Of 82 037 older adults who underwent surgery (all older than 70 years; 52 119 [63.5%] female), 16 900 of 34 044 deaths (49.6%) were cancer related at a median (interquartile range) follow-up of 46 (23-80) months. At 5 years, estimated cumulative incidence of cancer death (20.7%; 95% CI, 20.4%-21.0%) exceeded noncancer death (16.5%; 95% CI, 16.2%-16.8%) among all patients. However, noncancer deaths exceeded cancer deaths starting at 3 years after surgery in breast, prostate, and melanoma skin cancers, patients older than 85 years, and those with frailty. Cancer type, advancing age, and frailty were independently associated with cause-specific death.

Conclusions and Relevance

At the population level, the relative burden of cancer deaths exceeds noncancer deaths for older adults selected for surgery. No subgroup had a higher burden of noncancer death early after surgery, even in more vulnerable patients. This cause-specific overall prognosis information should be used for patient counseling, to assess patterns of over- or undertreatment in older adults with cancer at the system level, and to guide targets for system-level improvements to refine selection criteria and perioperative care pathways for older adults with cancer.

Introduction

Within a decade, 70% of new cancers will be diagnosed in older adults.1,2,3,4 Heterogenous health statuses and values generate nuances in cancer care with older adults.5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 While cancer is the predominant risk for death for younger patients with cancer, the risk of noncancer death is an important consideration in older adults with more prevalent comorbidities, frailty, decreased underlying life expectancy, and potentially different tumor biology.5,13,14,15,16,17 It is a concern that older adults with cancer may have a high burden of competing risks, and conventional cancer treatment will result in overtreatment.18,19 As such, the risk of cancer and noncancer death must frame cancer treatment choices, but these risks are not known for older adults undergoing surgery.

Poor understanding of the relative risks of cancer and noncancer deaths may lead to over- and undertreatment.18 Undertreated older adults die earlier of cancer, and overtreated older adults are exposed to nonbeneficial intensive treatments and unnecessary treatment-related toxicity with reduced quality of life.20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28 Recognizing this, a joint statement by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer, the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology, and the International Society of Geriatric Oncology recommends reporting cancer and noncancer deaths in conjunction with all-cause death and stratifying results by frailty status.29

For older adults with cancer, cause-specific survival after surgical resection or stratified by frailty status has not been reported to our knowledge, and competing risks are rarely considered.30,31,32,33 Applying prognostic data for younger patients is inadequate. Understanding older adults’ cancer and noncancer prognosis within current cancer care strategies is critical to patient counseling, health care system planning, and research to evaluate patterns of care, selection of treatments, improve cancer care strategies, and develop prognostic models.34,35,36,37,38

Given the concern for competing risks of noncancer death and overtreatment in older adults and the limited cause-specific prognostic data currently available, we aimed to examine the prognosis of older adults undergoing cancer surgery, including cancer, noncancer, and all-cause deaths over 5 years after surgery and to explore prognostic factors associated with cause-specific death. This study was conducted in accordance with recommendations for fundamental prognosis research and geriatric oncology research.29,34

Methods

Study Design and Data Sources

We designed a population-based retrospective cohort study of adults 70 years or older with a new diagnosis of solid malignant neoplasm who underwent resection. We assembled the cohort using linked health administrative databases using unique encoded identifiers for each patient housed at ICES (formerly the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences) for the province of Ontario, Canada. Race/ethnicity are not collected in the ICES data set. The Ontario Cancer Registry includes all patients with a cancer diagnosis in Ontario.39,40 The Registered Persons Database contains vital status and demographic data.41 Data on receipt of health care services is captured in several additional link data sets described in eTable 1 in Supplement 1. The Ontario population has universally accessible publicly funded health care.42 The study was approved by the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre Research Ethics Board (Toronto, Ontario, Canada). This report followed the PROGnosis RESearch Strategy (PROGRESS) and the REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely collected Data (RECORD) statements.34,43 Two caregivers and family members of older adults who underwent major cancer surgery were involved in developing the research question, defining outcomes measures, and interpreting results. Patient consent was not obtained because administrative anonymized data were used.

Study Cohort

We identified individuals 70 years or older with a new diagnosis of oropharyngeal, melanoma, breast, esophageal, gastrointestinal, colorectal, hepatobiliary, pancreatic, genitourinary, gynecologic, and bronchopulmonary cancer between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2017, using International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition codes (eTable 2 in Supplement 1).44 We included patients who underwent resection 90 to 180 days after cancer diagnosis (eTable 2 in Supplement 1).

Individuals were excluded if they had date of death preceding date of diagnosis, had previous cancer diagnosis within 5 years before the index cancer diagnosis, had 2 or more cancer diagnoses recorded on index diagnosis date, were admitted to long-term care prior to surgery, had missing date of death, or follow-up less than 180 days.

Outcomes Measures

Our outcome was death following surgery, and cause-specific death was classified as cancer death or noncancer death. Time to death was calculated from date of surgery to date of death. Cancer death was defined as International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes 140-239 and noncancer death as other codes in the Ontario Registrar General database (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). The primary cause of death was defined as the antecedent cause of death when available or the immediate cause of death when antecedent causes were not captured. High agreement in cause of death has been reported between the Ontario Registrar General and clinical follow-up in a prospective cohort of cancer patients.45 Participants were followed up until date of death, date of last clinical contact, or December 31, 2018, allowing for an opportunity of a minimum of 12 months of follow-up for each patient.

Covariates

Covariates are detailed in eTable 3 in Supplement 1. We quantified comorbidity burden using the Adjusted Clinical Groups system with a cutoff of 10 indicating high burden.46,47,48 We used a consensus classification of high and low surgical procedure intensity (eTable 4 in Supplement 1).49 We identified receipt of perioperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy within 180 days before or after surgery using claims data. We identified preoperative frailty using the Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Groups frailty marker.50 This frailty marker uses 12 clusters of frailty-defining diagnoses within important geriatric domains and has been externally validated against Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment and the Vulnerable Elders Survey.51,52,53 We determined rural residency using the rurality index of Ontario based on postal codes of primary residences.54 We captured socioeconomic status using the Material Deprivation Index, a composite index of ability to afford goods and activities, categorized into quintiles.55,56,57

Statistical Analysis

Using time to death, we estimated the cumulative incidence of death throughout 5 years after cancer surgery using the cumulative incidence function for all-cause death and for cancer death treating noncancer death as a competing risk. We reported cumulative incidence as percentages with 95% CIs at 1-, 3-, and 5-year points. Five years was selected as a conventional time horizon in cancer care; however, given that for older adults shorter times may be relevant, we also provide survival curves and estimates reported at shorter intervals. Cumulative incidence was reported for the entire cohort overall and further stratified by cancer type, age groups, and preoperative frailty status.

To explore the association of potential prognostic factors on the relative incidence of cancer and noncancer death, we fit multivariable subdistribution hazard models for cancer and noncancer death.58,59 We selected potential prognostic factors a priori based on clinical relevance and literature review including age, sex, cancer type, material deprivation quintile, rural residence, time of diagnosis, receipt of perioperative therapy, and preoperative frailty.60,61 To assess if the association of frailty cancer and noncancer death with outcomes differed by age, we included an interaction term between age and frailty status. We reported the subdistribution hazard ratios with 95% CI.

Data were missing for rural residency in 632 patients (0.8%) and material deprivation in 514 patients (0.6%). As such, we performed a complete-case analysis for multivariable analysis. Statistical significance was set at P ≤ .05. All analyses were conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 (SAS Institute). Data were analyzed from October to December 2019.

Results

We identified 82 037 older adults undergoing surgical resection for cancer (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1). Characteristics of included patients are presented in Table 1 and stratified by cancer type in eTable 5 in Supplement 1. The most common cancer types were breast cancer (22 811 patients [27.8%]) and gastrointestinal cancer (32 036 patients [39.1%]). Of 34 044 deaths, 49.6% (n = 16 900) were cancer related, with a median (interquartile range) follow-up of 46 (23-80) months. Postoperative mortality within 90 days of surgery accounted for 11.2% (n = 3831) of deaths.

Table 1. Characteristics of Included Patients.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Total No. | 82 037 |

| Age category, y | |

| 70-74 | 31 110 (37.9) |

| 75-79 | 23 439 (28.6) |

| 80-84 | 16 708 (20.4) |

| ≥85 | 10 780 (13.1) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 52 119 (63.5) |

| Male | 29 918 (36.4) |

| Residence | |

| Rural | 8380 (10.2) |

| Urban | 73 025 (89.0) |

| Missing | 632 (0.8) |

| Comorbidity burden | |

| High (ADG ≥10) | 26 563 (32.4) |

| Low (ADG <10) | 55 474 (67.6) |

| Material deprivation quintile | |

| First (highest) | 14 954 (18.2) |

| Second | 16 719 (20.4) |

| Third | 16 162 (19.7) |

| Fourth | 16 708 (20.4) |

| Fifth (lowest) | 17 216 (21.0) |

| Missing | 278 (0.3) |

| Preoperative frailty | |

| Yes | 6443 (7.9) |

| No | 75 594 (92.1) |

| Cancer type | |

| Breast | 22 811 (27.8) |

| Bronchopulmonary | 7429 (9.0) |

| Gastrointestinal | 32 036 (39.1) |

| Genitourinary | 8483 (10.3) |

| Gynecologic | 6658 (8.1) |

| Oropharyngeal | 867 (1.1) |

| Melanoma | 3753 (4.6) |

| Intensity of surgical procedure | |

| High | 48 812 (59.5) |

| Low | 33 225 (40.5) |

| Time of diagnosis | |

| 2007-2011 | 36 344 (44.3) |

| 2012-2017 | 45 693 (55.7) |

| Perioperative therapy | |

| Yes | 55 491 (67.6) |

| No | 26 546 (32.4) |

Abbreviation: ADG, aggregated diagnosis groups.

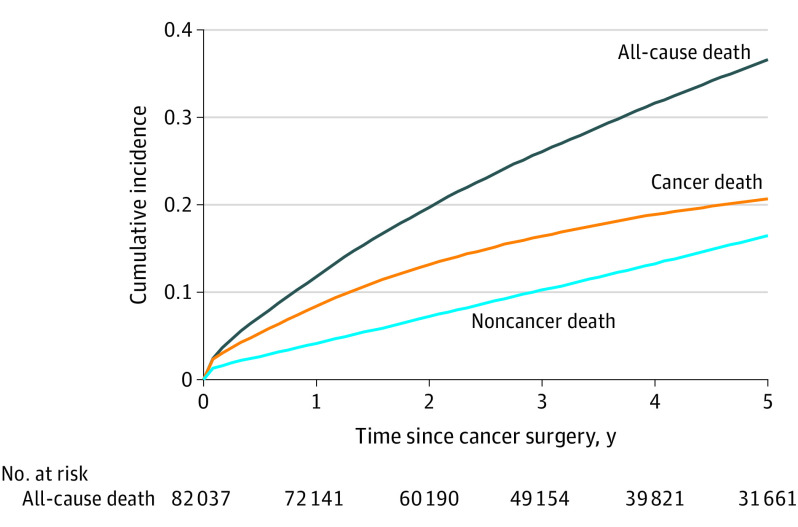

The cumulative incidence of death for the whole cohort is displayed in Figure 1. Throughout 5 years, the cumulative incidence of death from cancer was greater than death from noncancer causes. Estimated cumulative incidence of cancer death was 8.2% (95% CI, 8.4%-8.6%) at 1 year, 16.4% (95% CI, 16.2%-16.7%) at 3 years, and 20.7% (95% CI, 20.4%-21.0%) at 5 years after surgery. Estimated cumulative incidence of noncancer death was 5.3% (95% CI, 5.1%-5.5%) at 1 year, 11.9% (95% CI, 11.6%-12.2%) at 3 years, and 18.1% (95% CI, 17.8%-18.5%) at 5 years.

Figure 1. Cumulative Incidence of Cancer, Noncancer, and All-Cause Death for the Whole Cohort.

Across cancer types, the cumulative incidence of all-cause death varied from 22.0% (95% CI, 21.4%-22.6%) to 50.8% (95% CI, 47.2%-54.4%) at 5 years (eFigure 2 and eTable 6 in Supplement 1). Differences in the incidence of death between cancer types were driven mostly by cancer deaths. The lowest 5-year cumulative incidence of cancer death occurred in breast cancer at 9.1% (95% CI, 8.6%-9.5%) and the highest in oropharyngeal cancers at 29.1% (95% CI, 25.9%-32.3%). The incidence of death from cancer was greater than death from noncancer causes across most cancer types. The only exceptions were breast cancer and melanoma for which noncancer deaths were higher than cancer deaths by 5 years. Across gastrointestinal cancers, the cumulative incidence of noncancer death was similar; however, cancer deaths varied, with highest cumulative incidence in in hepato-pancreatico-biliary and esophageal cancers (eFigure 3 in Supplement 1). Across genitourinary cancers, bladder cancer had the greatest cumulative incidence of cancer death (eFigure 4 in Supplement 1).

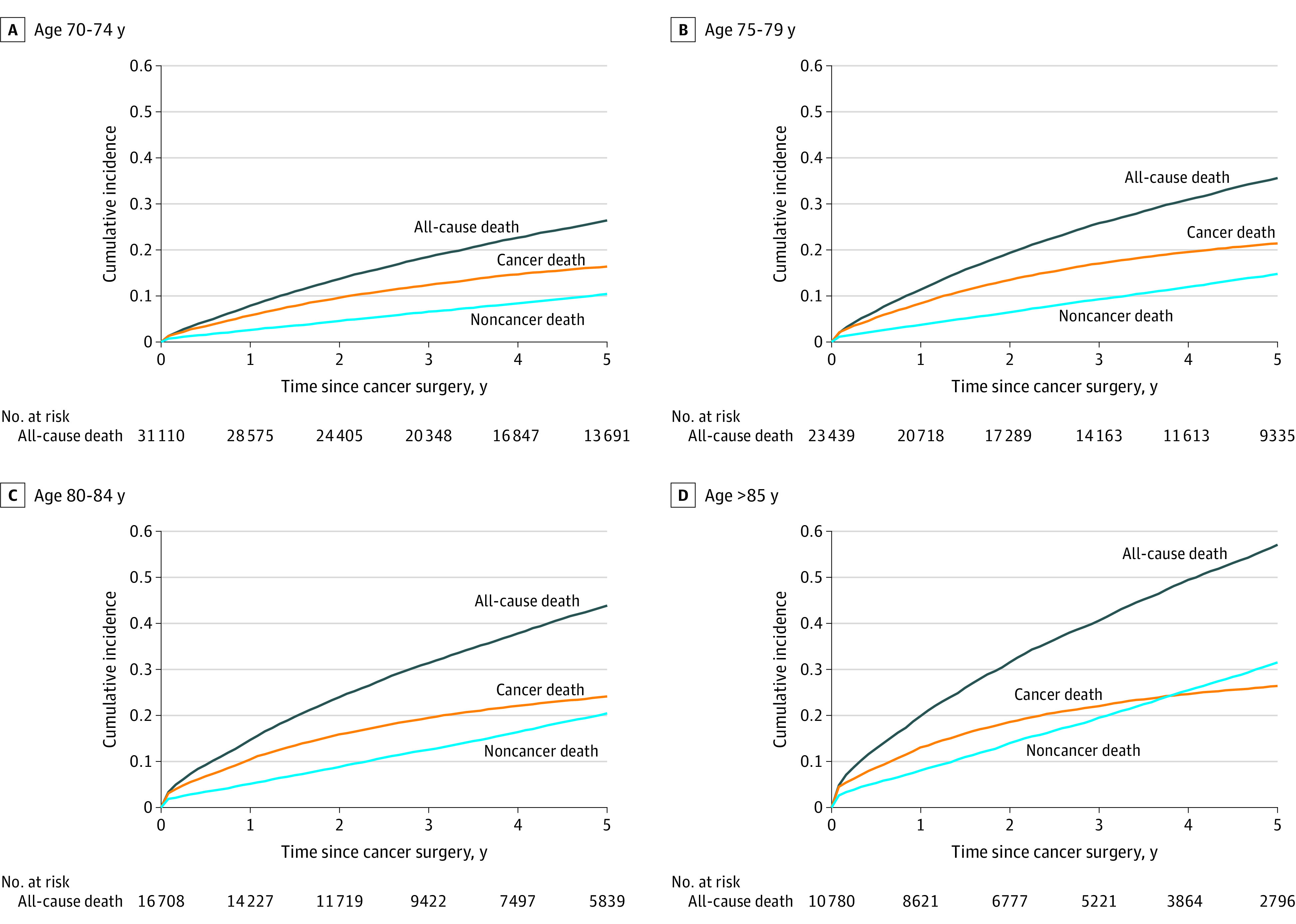

When stratified by age group, the cumulative incidence of all-cause death increased with advancing age, from 26.4% (95% CI, 25.8%-26.9%) to 57.0% (95% CI, 56.0%-58.1%) at 5 years (Figure 2; eTable 6 in Supplement 1), mostly owing to increases in noncancer deaths as patients got older. Only in patients 85 years and older did the incidence of death from noncancer causes became greater death from cancer throughout the 5 years after surgery.

Figure 2. Cumulative Incidence of Cancer, Noncancer, and All-Cause Death by Age Group.

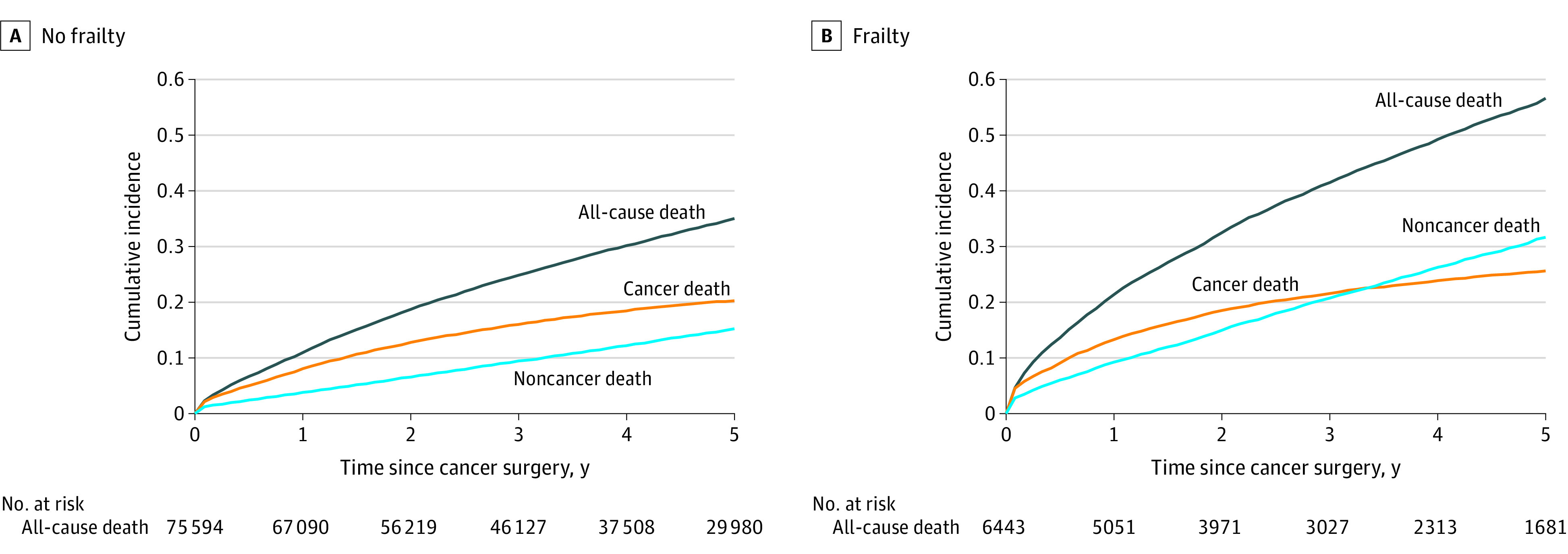

Preoperative frailty also was associated with the risk of death and patterns in cause of death. The cumulative incidence of all-cause death at 5 years was 34.9% (95% CI, 34.9%-35.3%) for those without frailty and 56.6% (95% CI, 55.2%-58.0%) for those with frailty (Figure 3; eTable 6 in Supplement 1). In patients with preoperative frailty, the incidence of death from noncancer causes became greater than death from cancer starting 3 years after surgery.

Figure 3. Cumulative Incidence of Cancer, Noncancer, and All-Cause Death by Frailty Status.

Preoperative patient and disease factors associated with the cumulative incidence of cancer deaths and of noncancer deaths were examined in separate multivariable subdistribution hazard models (Table 2). Advancing age was associated with cumulative incidence of cancer death for individuals aged 75 to 79 years (subdistribution hazard ratio, 1.33 [95% CI, 1.28-1.38]) to individuals 85 years and older (subdistribution hazard ratio, 2.06 [95% CI, 1.96-2.16]), compared with those aged 70 to 74 years). A similar association was observed in noncancer deaths but with greater magnitude of the effect estimates than for cancer death. Preoperative frailty was associated with increased cumulative incidence of both cancer and noncancer death. The magnitude of the association between frailty and noncancer death increased with age (interaction P < .001), and there was no frailty-age interaction observed for cancer death (interaction P = .09). Perioperative therapy was associated with increased cumulative incidence of cancer death and decreased incidence of noncancer death. Compared with breast cancer, all cancer types were strongly associated with an increased cumulative incidence of cancer death with subdistribution hazard ratios ranging from 2.34 (95% CI, 2.14-2.57) for melanoma to 4.69 (95% CI, 4.40-5.01) for bronchopulmonary cancers; this was not consistently observed for noncancer deaths.

Table 2. Multivariable Subdistribution Hazards Models for Cancer Death and Noncancer Death.

| Characteristic | Subdistribution, hazard ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer death | Noncancer death | |

| Age, y | ||

| 70-74 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 75-79 | 1.33 (1.28-1.38) | 1.45 (1.39-1.52) |

| 80-84 | 1.66 (1.59-1.73) | 2.00 (1.92-2.09) |

| ≥85 | 2.06 (1.96-2.16) | 3.02 (2.89-3.17) |

| Preoperative frailty | ||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 1.27 (1.21-1.34) | 1.64 (1.57-1.72) |

| Age-preoperative frailty interaction (frailty vs no frailty by age category), y | ||

| 70-74 | 1.43 (1.28-1.62) | 1.98 (1.76-2.22) |

| 75-79 | 1.33 (1.20-1.47) | 1.75 (1.59-1.92) |

| 80-84 | 1.21 (1.09-1.34) | 1.63 (1.50-1.77) |

| ≥85 | 1.20 (1.08-1.33) | 1.46 (1.35-1.59) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Female | 0.90 (0.87-0.93) | 0.79 (0.76-0.82) |

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Rural | 1.02 (0.97-1.07) | 1.06 (1.01-1.11) |

| Material deprivation | ||

| First (highest) | 1.13 (1.08-1.19) | 1.18 (1.13-1.24) |

| Second | 1.09 (1.04-1.14) | 1.09 (1.04-1.15) |

| Third | 1.06 (1.01-1.11) | 1.06 (1.01-1.11) |

| Fourth | 1.02 (0.98-1.07) | 1.05 (1.01-1.11) |

| Fifth (lowest) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Preoperative frailty | ||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 1.27 (1.21-1.34) | 1.64 (1.57-1.72) |

| Cancer type | ||

| Breast | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Bronchopulmonary | 4.69 (4.40-5.01) | 1.23 (1.16-1.31) |

| Gastrointestinal | 3.67 (3.48-3.87) | 0.99 (0.95-1.04) |

| Genitourinary | 2.76 (2.56-2.98) | 0.86 (0.80-0.92) |

| Gynecologic | 3.01 (2.82-3.21) | 0.99 (0.93-1.05) |

| Oropharyngeal | 3.88 (3.39-4.43) | 1.21 (1.05-1.39) |

| Melanoma | 2.34 (2.14-2.57) | 0.96 (0.89-1.04) |

| Time of diagnosis | ||

| 2007-2011 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 2012-2017 | 0.47 (0.45-0.48) | 1.49 (1.45-1.54) |

| Perioperative therapy | ||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 1.77 (1.71-1.84) | 0.83 (0.81-0.87) |

Discussion

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to describe the population-level overall prognosis of older adults after cancer surgery including an analysis of cancer and noncancer deaths. At 5 years, older adults selected for surgery had a 37% cumulative incidence of all-cause death, 21% of cancer deaths, and 16% of noncancer deaths. The relative burden of cancer compared with noncancer deaths varied by cancer type, age group, and preoperative frailty status. Noncancer deaths became greater than cancer deaths only in patients who underwent a surgical procedure for breast cancer or melanoma, who were 85 years and older, and with preoperative frailty.

This study contributes important new insight into cancer- and noncancer-specific death.31,32,62 A systematic review identified only 1 study reporting cause-specific end points using a competing risks approach in geriatric oncology.18 Another study reanalyzed data from a clinical trial of adjuvant endocrine therapy in breast cancer to evaluate cause-specific death.63,64 Most population-based studies have not reported outcomes for older adults, not reported cause-specific death, or not used a competing risks approach.31,32,33,60,61,65,66,67,68,69,70,71 The few studies using a competing risks approach were focused only on breast cancer, did not focus on cancer surgery, and did not address preoperative frailty status, which is a key concept in older adults care.30,72,73 Our study addresses these gaps in the literature by reporting on long-term survival outcomes for older adults undergoing cancer surgery stratified by cancer type, age, and preoperative frailty status and accounting for competing risks to avoid overestimation of the risk of cancer death in older adults.13,18,58,59 Previously, overall prognostic estimates for patients, clinicians, and health care systems planning were only available by applying data from younger patients.

Our results indicate that the incidence of death from cancer was greater than death from noncancer causes overall. Thus, even with cancer surgery, cancer remains the major driver of death, and there is no evidence of overtreatment. In certain circumstances, cancer death did not exceed noncancer death such as with breast, melanoma, and prostate cancers. If treated with surgery, patients with those cancers are less likely to die of cancer than from other causes. This difference can be related to lower-intensity surgery, highly effective cancer treatment, favorable cancer biology, low noncancer life expectancy, or a combination of these factors. Similarly, the risk of noncancer death was greater in patients 85 years and older and in those with preoperative frailty but only starting at 3 years after surgery. This suggests that cancer surgery is not overtreatment in older adults selected for surgery, even in vulnerable subgroups because cancer death still represents an immediate greater threat of mortality. This is important information considering observed patterns of undertreatment in older adults.23,24,25,26,28 It is important to personalize estimates of noncancer death to avoid foregoing surgery in those who would benefit; lack of cancer treatment would further increase the risk of early cancer-specific death.74,75,76

Our data can be directly used to provide overall prognosis estimates specific to older adult populations with cancer, and this can be balanced against underlying life expectancy estimates without cancer using tools such as ePrognosis.77 These data can be combined with geriatric-specific care processes, such as integrated geriatric oncology pathways, comprehensive geriatric assessment, prehabilitation, and geriatric comanagement, which are still rare within surgical cancer care, to further support decision-making, mitigate risks, and support cancer treatment, particularly those at higher risk.74,78,79,80,81,82,83,84

Limitations and Strengths

There are study limitations. Because of the retrospective design and administrative data sources, the data used were not specifically collected for the purposes of the research question. In particular, our results must be interpreted in the context of patients selected for surgical treatment. For example, only 8% of our cohort had preoperative frailty compared with 10% to 20% in the general older adult population, pointing toward the expected selection bias for cancer surgery.85,86,87 We could not decipher the rationale for not undergoing a surgical procedure using administrative data, nor could we determine if surgery was offered to some patients but declined. Because comparisons with older adults without cancer, older adults with cancer not having surgery, or younger surgery patients with cancer bear selection bias and are not informative for decision-making in the individual older adults selected for cancer surgery, such comparative analyses were not undertaken. We focused on describing overall prognosis of patients treated with surgery rather than an assessment of the causal effect of surgery compared with no surgery. Although high agreement is documented between our registries and primary sources in cause of death ascertainment, prevalent comorbidities could affect the accuracy of the listed cause of death on death certificates and lead to misclassification, even more so if misclassification is related to age.45 This would lead to overestimating noncancer deaths; therefore the observations of patterns of cancer vs noncancer deaths would remain and the conclusions would stand. Finally, cancer stage information is not reliably available in our databases, so we cannot comment on cause-specific mortality by stage. Despite these limitations, our results provide important knowledge regarding the burden of cancer- and noncancer-related deaths, which demonstrates that cancer surgery is not overtreatment for older adults currently selected for surgery and highlight the importance of considering multiple patient-centered factors for individualized decision-making and need to avoid de-escalation of care and risk of undertreatment in older adults.

The population-based design of this study is a strength that allowed for a real-world assessment of the prognosis of older adults undergoing cancer surgery. These data represent outcomes within a universal health care system avoiding bias by insurance status–limited access. We used high-quality linked administrative databases and definitions with known accuracy and reliability including comprehensive availability of cause of death, limited missing data, and measurement error. This allowed for an accurate assessment of system-level cancer care performance regarding postoperative cancer and noncancer deaths.

Conclusions

In this study, we reported novel cause-specific death throughout 5 years after cancer surgery in older adults accounting for competing risks. Overall, the incidence of death from cancer exceeded that from noncancer causes. In a few subgroups, the incidence of noncancer death was greater: breast, prostate, and melanoma skin cancer; patients 85 years and older; or preoperative frailty after 3 years. For most patients, cancer surgery should not be avoided due to concern about overtreatment related to competing risks resulting in noncancer death. Clinicians and patients can directly use this knowledge about the association of surgery for cancer with outcomes in shared decision-making, including data stratified by cancer type, age, and frailty. For patients with a higher risk of noncancer death (breast, melanoma skin, and prostate cancers; age >85 years; and frailty) further interventions should be considered to mitigate risks of noncancer death, such as integrated geriatric oncology pathways, comprehensive geriatric assessment, prehabilitation, and geriatric comanagement. Future work should focus on integrating quality of life and functional outcomes with cause-specific death information to support comprehensive patient counseling and using the current findings to assist in building prognostic models for more individualized risk prediction.

eTable 1. Data Sources

eTable 2. Cohort Identification Strategy

eTable 3. Covariate Definitions

eTable 4. Surgical Procedure Intensity

eTable 5. Characteristics of Study Cohort by Cancer Type

eTable 6. Cumulative Incidence at 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year Timepoints

eFigure 1. Cohort Selection Flowchart

eFigure 2. Cumulative Incidence of Cancer, Non-Cancer, and All-Cause Death by Cancer Type

eFigure 3. Cumulative Incidence of Cancer, Non-Cancer, and All-Cause Death Stratified by Gastrointestinal Cancer Subtypes

eFigure 4. Cumulative Incidence of Cancer, Non-Cancer, and All-Cause Death Stratified by Genitourinary Cancer Subtypes

Nonauthor Collaborators. Members of the Recovery After Surgical Therapy for Older Adults Research–Cancer (RESTORE-Cancer) Group

References

- 1.Balducci L, Ershler WB. Cancer and ageing: a nexus at several levels. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(8):655-662. doi: 10.1038/nrc1675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gloeckler Ries LA, Reichman ME, Lewis DR, Hankey BF, Edwards BK. Cancer survival and incidence from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. Oncologist. 2003;8(6):541-552. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.8-6-541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards BK, Howe HL, Ries LAG, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973-1999, featuring implications of age and aging on U.S. cancer burden. Cancer. 2002;94(10):2766-2792. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, Hortobagyi GN, Buchholz TA. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(17):2758-2765. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yourman LC, Lee SJ, Schonberg MA, Widera EW, Smith AK. Prognostic indices for older adults: a systematic review. JAMA. 2012;307(2):182-192. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, Coltman CA Jr, Albain KS. Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(27):2061-2067. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912303412706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talarico L, Chen G, Pazdur R. Enrollment of elderly patients in clinical trials for cancer drug registration: a 7-year experience by the US Food and Drug Administration. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(22):4626-4631. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yellen SB, Cella DF, Leslie WT. Age and clinical decision making in oncology patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86(23):1766-1770. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.23.1766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hurria A, Mohile SG, Dale W. Research priorities in geriatric oncology: addressing the needs of an aging population. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10(2):286-288. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scher KS, Hurria A. Under-representation of older adults in cancer registration trials: known problem, little progress. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(17):2036-2038. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.6727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hurria A, Dale W, Mooney M, et al. ; Cancer and Aging Research Group . Designing therapeutic clinical trials for older and frail adults with cancer: U13 conference recommendations. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(24):2587-2594. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.55.0418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurria A, Levit LA, Dale W, et al. ; American Society of Clinical Oncology . Improving the evidence base for treating older adults with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology statement. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(32):3826-3833. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berry SD, Ngo L, Samelson EJ, Kiel DP. Competing risk of death: an important consideration in studies of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):783-787. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02767.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pallis AG, Ring A, Fortpied C, et al. ; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Elderly Task Force . EORTC workshop on clinical trial methodology in older individuals with a diagnosis of solid tumors. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(8):1922-1926. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: an approach for clinicians . Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: an approach for clinicians: American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(10):E1-E25. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04188.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farmer C, Fenu E, O’Flynn N, Guthrie B. Clinical assessment and management of multimorbidity: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2016;354:i4843. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams GR, Mackenzie A, Magnuson A, et al. Comorbidity in older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(4):249-257. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2015.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burdett N, Vincent AD, O’Callaghan M, Kichenadasse G. Competing risks in older patients with cancer: a systematic review of geriatric oncology trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(8):825-830. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DuMontier C, Loh KP, Bain PA, et al. Defining undertreatment and overtreatment in older adults with cancer: a scoping literature review. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(22):2558-2569. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yancik R, Wesley MN, Ries LAG, Havlik RJ, Edwards BK, Yates JW. Effect of age and comorbidity in postmenopausal breast cancer patients aged 55 years and older. JAMA. 2001;285(7):885-892. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.7.885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Angarita FA, Chesney T, Elser C, Mulligan AM, McCready DR, Escallon J. Treatment patterns of elderly breast cancer patients at two Canadian cancer centres. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(5):625-634. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bastiaannet E, Liefers GJ, de Craen AJM, et al. Breast cancer in elderly compared to younger patients in the Netherlands: stage at diagnosis, treatment and survival in 127,805 unselected patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;124(3):801-807. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0898-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bouchardy C, Rapiti E, Fioretta G, et al. Undertreatment strongly decreases prognosis of breast cancer in elderly women. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(19):3580-3587. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Owusu C, Lash TL, Silliman RA. Effect of undertreatment on the disparity in age-related breast cancer-specific survival among older women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;102(2):227-236. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9321-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Camilon PR, Stokes WA, Nguyen SA, Lentsch EJ. Are the elderly with oropharyngeal carcinoma undertreated? Laryngoscope. 2014;124(9):2057-2063. doi: 10.1002/lary.24660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foster JA, Salinas GD, Mansell D, Williamson JC, Casebeer LL. How does older age influence oncologists’ cancer management? Oncologist. 2010;15(6):584-592. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lemmens VE, van Halteren AH, Janssen-Heijnen MLG, Vreugdenhil G, Repelaer van Driel OJ, Coebergh JWW. Adjuvant treatment for elderly patients with stage III colon cancer in the southern Netherlands is affected by socioeconomic status, gender, and comorbidity. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(5):767-772. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walter J, Tufman A, Holle R, Schwarzkopf L. “Age matters”—German claims data indicate disparities in lung cancer care between elderly and young patients. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0217434. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wildiers H, Mauer M, Pallis A, et al. End points and trial design in geriatric oncology research: a joint European Organisation For Research And Treatment Of Cancer—Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology—International Society Of Geriatric Oncology position article. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(29):3711-3718. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.6125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Land LH, Dalton SO, Jensen M-B, Ewertz M. Impact of comorbidity on mortality: a cohort study of 62,591 Danish women diagnosed with early breast cancer, 1990-2008. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131(3):1013-1020. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1819-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jørgensen TL, Hallas J, Friis S, Herrstedt J. Comorbidity in elderly cancer patients in relation to overall and cancer-specific mortality. Br J Cancer. 2012;106(7):1353-1360. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Angelis R, Sant M, Coleman MP, et al. ; EUROCARE-5 Working Group . Cancer survival in Europe 1999-2007 by country and age: results of EUROCARE—5-a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(1):23-34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70546-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vercelli M, Capocaccia R, Quaglia A, Casella C, Puppo A, Coebergh JW; The EUROCARE Working Group . Relative survival in elderly European cancer patients: evidence for health care inequalities. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2000;35(3):161-179. doi: 10.1016/S1040-8428(00)00075-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hemingway H, Croft P, Perel P, et al. ; PROGRESS Group . Prognosis research strategy (PROGRESS) 1: a framework for researching clinical outcomes. BMJ. 2013;346:e5595. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamel MB, Henderson WG, Khuri SF, Daley J. Surgical outcomes for patients aged 80 and older: morbidity and mortality from major noncardiac surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(3):424-429. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53159.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seib CD, Rochefort H, Chomsky-Higgins K, et al. Association of patient frailty with increased morbidity after common ambulatory general surgery operations. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(2):160-168. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.4007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robinson TN, Walston JD, Brummel NE, et al. Frailty for surgeons: review of a National Institute on Aging conference on frailty for specialists. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221(6):1083-1092. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.08.428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suskind AM, Finlayson E. A call for frailty screening in the preoperative setting. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(3):240-241. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McLaughlin JR, Kreiger N, Marrett LD, Holowaty EJ. Cancer incidence registration and trends in Ontario. Eur J Cancer. 1991;27(11):1520-1524. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(91)90041-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robles SC, Marrett LD, Clarke EA, Risch HA. An application of capture-recapture methods to the estimation of completeness of cancer registration. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41(5):495-501. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90052-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iron K, Zagorski BM, Sykora K, Manuel DG. Living and Dying in Ontario: An Opportunity to Improve Health Information. Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES). 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Government of Canada . Canada Health Act. Accessed May 25, 2019. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-system/canada-health-care-system-medicare/canada-health-act.html

- 43.Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. ; RECORD Working Committee . The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12(10):e1001885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lundebjerg NE, Trucil DE, Hammond EC, Applegate WB. When it comes to older adults, language matters: Journal of the American Geriatrics Society adopts modified American Medical Association style. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(7):1386-1388. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brenner DR, Tammemägi MC, Bull SB, Pinnaduwaje D, Andrulis IL. Using cancer registry data: agreement in cause-of-death data between the Ontario Cancer Registry and a longitudinal study of breast cancer patients. Chronic Dis Can. 2009;30(1):16-19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weiner JP, Starfield BH, Steinwachs DM, Mumford LM. Development and application of a population-oriented measure of ambulatory care case-mix. Med Care. 1991;29(5):452-472. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199105000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Starfield B, Weiner J, Mumford L, Steinwachs D. Ambulatory care groups: a categorization of diagnoses for research and management. Health Serv Res. 1991;26(1):53-74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reid RJ, MacWilliam L, Verhulst L, Roos N, Atkinson M. Performance of the ACG case-mix system in two Canadian provinces. Med Care. 2001;39(1):86-99. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200101000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schwarze ML, Barnato AE, Rathouz PJ, et al. Development of a list of high-risk operations for patients 65 years and older. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(4):325-331. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lieberman R, Abrams C, Weiner J. Development and Evaluation of the Johns Hopkins University Risk Adjustment Models for Medicare+ Choice Plan Payment. Johns Hopkins University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 51.McIsaac DI, Bryson GL, van Walraven C. Association of frailty and 1-year postoperative mortality following major elective noncardiac surgery: a population-based cohort study. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(6):538-545. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.5085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neuman HB, Weiss JM, Leverson G, et al. Predictors of short-term postoperative survival after elective colectomy in colon cancer patients ≥ 80 years of age. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(5):1427-1435. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2721-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sternberg SA, Bentur N, Abrams C, et al. Identifying frail older people using predictive modeling. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(10):e392-e397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kralj B. Measuring “rurality” for purposes of health-care planning: an empirical measure for Ontario. Ont Med Review. 2000;67:33-52. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alter DA, Naylor CD, Austin P, Tu JV. Effects of socioeconomic status on access to invasive cardiac procedures and on mortality after acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(18):1359-1367. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910283411806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wilkins R. Use of postal codes and addresses in the analysis of health data. Health Rep. 1993;5(2):157-177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Canadian Institute for Health Information . Measuring health inequalities: a toolkit. Accessed March 30, 2021. https://www.cihi.ca/en/measuring-health-inequalities-a-toolkit [Google Scholar]

- 58.Austin PC, Lee DS, Fine JP. Introduction to the analysis of survival data in the presence of competing risks. Circulation. 2016;133(6):601-609. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Putter H, Fiocco M, Geskus RB. Tutorial in biostatistics: competing risks and multi-state models. Stat Med. 2007;26(11):2389-2430. doi: 10.1002/sim.2712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Galvin A, Delva F, Helmer C, et al. Sociodemographic, socioeconomic, and clinical determinants of survival in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the literature focused on the elderly. J Geriatr Oncol. 2018;9(1):6-14. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2017.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jiang M, Foebel AD, Kuja-Halkola R, et al. Frailty index as a predictor of all-cause and cause-specific mortality in a Swedish population-based cohort. Aging (Albany NY). 2017;9(12):2629-2646. doi: 10.18632/aging.101352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Niu X, Roche LM, Pawlish KS, Henry KA. Cancer survival disparities by health insurance status. Cancer Med. 2013;2(3):403-411. doi: 10.1002/cam4.84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van de Water W, Markopoulos C, van de Velde CJH, et al. Association between age at diagnosis and disease-specific mortality among postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. JAMA. 2012;307(6):590-597. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Derks MGM, Bastiaannet E, van de Water W, et al. Impact of age on breast cancer mortality and competing causes of death at 10 years follow-up in the adjuvant TEAM trial. Eur J Cancer. 2018;99:1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dasgupta P, Aitken JF, Pyke C, Baade PD. Competing mortality risks among women aged 50-79 years when diagnosed with invasive breast cancer, Queensland, 1997-2012. Breast. 2018;41:113-119. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2018.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Massa ST, Cass LM, Challapalli S, et al. Demographic predictors of head and neck cancer survival differ in the elderly. Laryngoscope. 2019;129(1):146-153. doi: 10.1002/lary.27289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(6):1374-1403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kimmick GG, Li X, Fleming ST, et al. ; Written on behalf of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention National Program of Cancer Registry Patterns of Care Study Group . Risk of cancer death by comorbidity severity and use of adjuvant chemotherapy among women with locoregional breast cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2018;9(3):214-220. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2017.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Johansson ALV, Trewin CB, Hjerkind KV, Ellingjord-Dale M, Johannesen TB, Ursin G. Breast cancer-specific survival by clinical subtype after 7 years follow-up of young and elderly women in a nationwide cohort. Int J Cancer. 2019;144(6):1251-1261. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li G, Tian ML, Bing YT, et al. Clinicopathological features and prognosis factors for survival in elderly patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor: A STROBE-compliant article. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(11):e14576. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000014576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Quinn BA, Deng X, Colton A, Bandyopadhyay D, Carter J, Fields EC. Increasing age predicts poor cervical cancer prognosis with subsequent effect on treatment and overall survival. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;99(2 suppl):E308. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.06.1338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ward SE, Richards PD, Morgan JL, et al. Omission of surgery in older women with early breast cancer has an adverse impact on breast cancer-specific survival. Br J Surg. 2018;105(11):1454-1463. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fu J, Wu L, Jiang M, et al. Real-world impact of non-breast cancer-specific death on overall survival in resectable breast cancer. Cancer. 2017;123(13):2432-2443. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ghignone F, van Leeuwen BL, Montroni I, et al. ; International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) Surgical Task Force . The assessment and management of older cancer patients: a SIOG surgical task force survey on surgeons’ attitudes. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42(2):297-302. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Saur NM, Montroni I, Ghignone F, Ugolini G, Audisio RA. Attitudes of surgeons toward elderly cancer patients: a survey from the SIOG Surgical Task Force. Visc Med. 2017;33(4):262-266. doi: 10.1159/000477641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chesney TR, Pang G, Ahmed N. Caring for older surgical patients: contemporary attitudes, knowledge, practices, and needs of general surgeons and residents. Ann Surg. 2018;268(1):77-8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.ePrognosis. COVID-19 prognosis information: what would you like to do? Accessed January 6, 2018. https://eprognosis.ucsf.edu/index.php

- 78.Wildiers H, Heeren P, Puts M, et al. International Society of Geriatric Oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(24):2595-2603. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mohile SG, Dale W, Somerfield MR, et al. Practical assessment and management of vulnerabilities in older patients receiving chemotherapy: ASCO guideline for geriatric oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(22):2326-2347. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.8687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shahrokni A, Kim SJ, Bosl GJ, Korc-Grodzicki B. How we care for an older patient with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(2):95-102. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.017608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mohanty S, Rosenthal RA, Russell MM, Neuman MD, Ko CY, Esnaola NF. Optimal perioperative management of the geriatric patient: a best practices guideline from the American College of Surgeons NSQIP and the American Geriatrics Society. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222(5):930-947. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kristjansson SR, Spies C, Veering BTH, et al. Perioperative care of the elderly oncology patient: a report from the SIOG task force on the perioperative care of older patients with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2012;3(2):147-162. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2012.01.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shahrokni A, Tin AL, Sarraf S, et al. Association of geriatric comanagement and 90-day postoperative mortality among patients aged 75 years and older with cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e209265-e209265. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.9265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sacks GD, Dawes AJ, Ettner SL, et al. Surgeon perception of risk and benefit in the decision to operate. Ann Surg. 2016;264(6):896-903. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, Oude Voshaar RC. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(8):1487-1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04054.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Song X, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Prevalence and 10-year outcomes of frailty in older adults in relation to deficit accumulation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):681-687. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02764.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Handforth C, Clegg A, Young C, et al. The prevalence and outcomes of frailty in older cancer patients: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(6):1091-1101. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Data Sources

eTable 2. Cohort Identification Strategy

eTable 3. Covariate Definitions

eTable 4. Surgical Procedure Intensity

eTable 5. Characteristics of Study Cohort by Cancer Type

eTable 6. Cumulative Incidence at 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year Timepoints

eFigure 1. Cohort Selection Flowchart

eFigure 2. Cumulative Incidence of Cancer, Non-Cancer, and All-Cause Death by Cancer Type

eFigure 3. Cumulative Incidence of Cancer, Non-Cancer, and All-Cause Death Stratified by Gastrointestinal Cancer Subtypes

eFigure 4. Cumulative Incidence of Cancer, Non-Cancer, and All-Cause Death Stratified by Genitourinary Cancer Subtypes

Nonauthor Collaborators. Members of the Recovery After Surgical Therapy for Older Adults Research–Cancer (RESTORE-Cancer) Group