Abstract

Endocrine disrupting chemicals pose a threat to health and reproduction. Plasticizers such as phthalates and bisphenols are particularly problematic because they are present in many consumer products and exposure can begin in utero and continue throughout the lifetime of the individual. Evidence suggests that these chemicals can have ancestral and transgenerational effects, making them a huge public health concern for the reproductive health of current and future generations. Studies performed in rodents or using rodent- or human-derived tissues have been critical for understanding the toxic effects of plasticizers on the ovary and their mechanisms of action. This review addresses current in vitro and rodent-based in vivo studies investigating the effects of bisphenols and phthalates on ovarian health, female reproduction, and correlations between human exposure and reproductive pathologies.

Keywords: Ovary, endocrine disruption, plasticizer, steroidogenesis, folliculogenesis

Introduction

Plasticizers are chemicals used in manufacturing to make materials more flexible and elastic. These chemicals are ubiquitous in the environment and can be found in medical supplies and devices, clothing, toys, food packaging, and building materials. Recently, plasticizers such as bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates have emerged as endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDC). EDCs are chemicals or chemical mixtures that interfere with the body’s normal hormone response, often through disrupting endogenous hormone production, interfering with hormone signaling, or increasing metabolism of target hormones. Reproductive tissues, including the ovary, are particularly sensitive to the endocrine disrupting effects of these chemicals. The ovary is the female gonad and serves as the site of follicle development (folliculogenesis) and steroid hormone production (steroidogenesis). These processes are hormonally regulated and highly susceptible to EDC exposure. This review describes recent studies performed using rodent models and isolated human tissues that identified the endocrine disrupting actions of common plasticizers such as bisphenols and phthalates on the ovary and highlight human epidemiological studies exploring their links to reproductive pathologies.

Effects of plasticizers on folliculogenesis

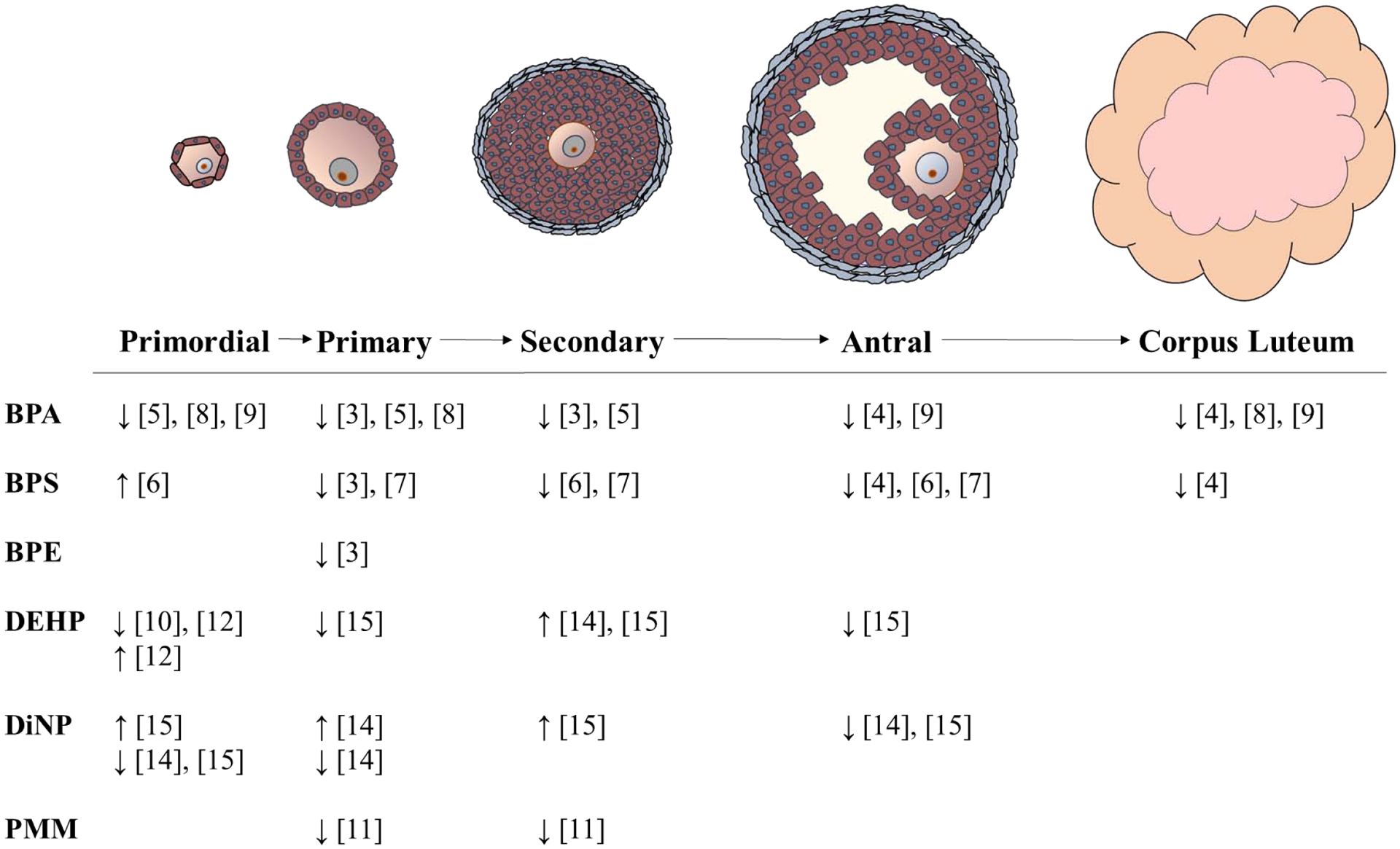

One of the primary functions of the ovary is folliculogenesis. During this process, ovarian follicles undergo a maturation process to prepare for ovulation and release of the oocyte for fertilization [1]. The stages of folliculogenesis are depicted in Figure 1. Females are born with a finite number of immature primordial follicles that mature throughout their reproductive life. Either inhibition or acceleration of folliculogenesis can have profound effects on reproduction. Inhibition of folliculogenesis can prevent the development of pre-ovulatory follicles that will release a viable oocyte upon ovulation [2]. Conversely, accelerated folliculogenesis can lead to faster depletion of ovarian follicles and premature onset of reproductive senescence [2]. Exposure to plasticizers has been linked to shifts in ovarian follicle populations, indicating disruption of folliculogenesis (Table 1). Recent rodent studies demonstrated that perinatal exposure to BPA can disrupt germ cell nest breakdown and decrease primary, secondary, and antral follicle populations, and decrease corpus luteum formation, suggesting that exposure may be preventing immature follicles from undergoing maturation [3–5]. In manufacturing, BPA has been replaced with analogues like bisphenol E (BPE) and bisphenol S (BPS). However, exposure to these new analogues in rodents is associated with shifts in follicle distribution towards early stages of folliculogenesis, similar to BPA, calling into question their viability as safer alternatives to BPA [3, 4, 6]. Other studies have shown that adult bisphenol exposure decreased primordial, primary, and antral follicle populations and decreased the formation of corpora lutea in mice [7, 8]. Further, both perinatal and adult exposures to bisphenols increased atresia and the breakdown and resorption of ovarian follicles in both mice and rats [4, 8, 9].

Figure 1. Effects of bisphenols and phthalates on folliculogenesis.

Current studies demonstrate bisphenols and phthalates can impair folliculogenesis by altering follicle populations. Major findings from these studies are summarized here. ↓ indicate decreased and ↑ indicate increased follicle populations relative to vehicle controls. PMM refers to studies performed with phthalate metabolite mixtures.

Table 1:

Effects of bisphenols and phthalates on folliculogenesis

| Chemical | Model | Exposure | Main Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPA | Mouse | Perinatal Exposure | ||

| 0, 0.5, 20, or 50μg/kg/d administered orally to pregnant females on gestational day (GD) 11-birth, female pups euthanized at PND4 |

|

[3] | ||

| Adult Exposure | ||||

| 0, 12.5, 25, or 50mg/kg intraperitoneal injections for 10 days, beginning at 6 weeks of age, euthanized immediately |

|

[8] | ||

| Rat | Perinatal Exposure | |||

| 25ng/kg/d or 5mg/kg/d subcutaneously PND1–15, euthanized PND105 |

|

[9] | ||

| 0, 2.5, 25, 250, 2500, or 25000μg/kg/day administered by gavage from GD6-PND21, euthanized immediately |

|

[5] | ||

| 0, 0.5, 5, or 50mg/kg o subcutaneously on post-natal day (PND) 1–10, euthanized PND75 |

|

[4] | ||

| Adult Exposure | ||||

| 25ng/kg/d or 5mg/kg/d subcutaneously PND90-PND105, euthanized either PND106 or PND133 |

|

[9] | ||

| BPE | Mouse | Perinatal Exposure | ||

| 0, 0.5, 20, or 50μg/kg/d administered orally to pregnant females on gestational day (GD) 11-birth, female pups euthanized at PND4 |

|

[3] | ||

| BPS | Mouse | Perinatal Exposure | ||

| 0, 0.5, 20, or 50μg/kg/d of either administered orally to pregnant females on gestational day (GD) 11-birth, female pups euthanized at PND4 |

|

[3] | ||

| 0, 2, 10, 50, 100, or 200μg/kg administered orally to pregnant mice 12.5–15.5 days post-coitus F1 and F2 generation females were euthanized PND21 | F1

|

[6] | ||

F2

| ||||

| Adult Exposure | ||||

| 0, 0.004, 0.375, 37.5, or 375ng/ml in drinking water for 4 weeks, beginning at 5 weeks of age, euthanized immediately |

|

[7] | ||

| Rat | Perinatal Exposure | |||

| 0, 0.5, 5, or 50mg/kg subcutaneously on post-natal day (PND) 1–10, euthanized PND75 |

|

[4] | ||

| DBP | Mouse | Adult Exposure | ||

| 0, 10, 100, or 1000μg/kg/d DBP administered orally to 80 day old mice for 30 days, euthanized immediately |

|

[13] | ||

| DEHP | Mouse | Perinatal Exposure | F1

|

[12] |

| 0, 0.02, 0.2, 500, and 750mg/kg/d administered orally to pregnant dams GD11-birth F1, F2, and F3 generation females were euthanized at 12 months | F2

|

|||

F3

| ||||

| 0 or 0.6mg/kg/d intraperitoneal injections PND0–4, euthanized PND5 | Decreased primordial follicles | [10] | ||

| Adult Exposure | ||||

| 0, 0.02, 0.2, 20, or 200mg/kg/d administered orally to 40 day old females for 10 days, euthanized either immediately or 3, 6, or 9 months post-dosing | 3 months post-dosing

|

[14] | ||

6 months post-dosing

| ||||

9 months post-dosing

| ||||

| 0, 0.02, 0.2, 20, or 200mg/kg/d administered orally to 40 day old females for 10 days, euthanized 12, 15, or 18 months post-dosing | 12 months post-dosing

|

[15] | ||

15 months post-dosing

| ||||

18 months post-dosing

| ||||

| DiNP | Mouse | Adult Exposure | 3 months post-dosing

|

[14] |

| 0, 0.02, 0.1, 20, or 200mg/kg/d administered orally to 40 day old females for 10 days, euthanized either immediately or 3, 6, or 9 months post-dosing | 6 months post-dosing

|

|||

9 months post-dosing

| ||||

| 0, 0.02, 0.1, 20, or 200mg/kg/d administered orally to 40 day old females for 10 days, euthanized 12, 15, or 18 months post-dosing | 12 months post-dosing

|

[15] | ||

15 months post-dosing

| ||||

18 months post-dosing

| ||||

| Phthalate Metabolite Mixture | Mouse | Perinatal Exposure | ||

| 0, 10, 100, or 500x of phthalate metabolite mixture (SELMA study; 33% MBP, 16% MBzP, 21% MEHP, 30% MINP) administered orally to pregnant dams from GD0.5 to birth pups euthanized PND21 and PND90 | PND21

|

[11] | ||

PND90

|

Several rodent-based studies suggest phthalates can disrupt folliculogenesis. Perinatal exposure to phthalates such as di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) or a mixture of phthalate metabolites decreased primordial, primary, and secondary follicle populations in mice [10–12]. Brehm et al. (2018) demonstrated that exposing pregnant dams to DEHP affected follicle populations in the resulting pups (filial generation 1, F1) and altered follicle populations in the subsequent F2 and F3 generations, indicating that DEHP can have transgenerational effects on folliculogenesis [12]. In adult mice, subchronic exposure to DEHP or diisononyl phthalate (DiNP), a DEHP replacement chemical, altered follicle populations throughout the lifetime of the aging mouse, whereas exposure to dibutyl phthalate (DBP) did not appear to impact folliculogenesis [13–15]. Similar to bisphenols, some phthalates have been linked to increased follicular atresia in mice [11, 13].

In addition to changes in follicle populations, plasticizers target the oocyte and disrupt its maturation and communication with other cell types present in the follicle. In mice, exposure to BPA in vitro or BPS exposure in vivo can promote germinal vesicle breakdown and increase the meiotic progression of oocytes, respectively [6, 16]. Additionally, bisphenols can impair communication with granulosa cells through downregulation of the oocyte derived paracrine factors bone morphogenetic protein 15 (Bmp15) and growth/differentiation factor 9 (Gdf9), as well as reducing gap junctional intercellular communication between the cumulus cells and the oocyte [6, 16, 17]. In contrast to bisphenols, exposure to phthalates such as DBP reduces germinal vesicle breakdown and disrupts meiosis in mouse oocytes [18, 19]. Use of estrogen receptor (ESR) antagonists indicates that DBP-induced disruption of meiosis is dependent on ESR1 and ESR2 activation, although it is unclear how DBP is modifying ESR signaling [18]. Altogether, these studies demonstrate that bisphenols and phthalates disrupt the normal progression of folliculogenesis and impair oocyte maturation. These effects can have serious repercussions for fertility.

Effects of plasticizers on follicle health and potential mechanisms of action

In vitro, both bisphenols and phthalates can reduce follicle growth and viability in mouse ovarian follicles, suggesting that the health of the follicle is adversely affected with exposure to these chemicals [17, 20, 21]. However, the mechanisms by which plasticizers affect follicle health and development are not fully understood. Recent studies have identified several cellular processes and molecular targets that are altered with plasticizer exposure. These are discussed below.

Oxidative Stress

Several studies have demonstrated that phthalates and bisphenols induce oxidative stress in mouse ovarian follicles, mouse oocytes, and human granulosa cells [18, 22–24]. Liu et al. (2019) demonstrated that the oxidative stress induced by DEHP exposure was dependent on the induction and activity of an oxidative stress related factor xanthine dehydrogenase (XDH) in the neonatal mouse ovary in vitro. Inhibition of XDH with RNAi rescued the ovary from DEHP-induced oxidative stress [24]. Phthalate- or bisphenol-mediated increases in oxidative stress are often accompanied by altered expression/activity of the antioxidant enzymes superoxide dismutase (SOD1), glutathione peroxidase (GPX1), and catalase (CAT) that work to break down reactive oxygen species (ROS) [23, 24]. This altered expression/activity of antioxidant enzymes often leads to accumulation of ROS and results in DNA damage [18, 22, 24]. Additionally, exposure to phthalates such as DBP can decrease ovarian expression of DNA damage repair genes, including breast cancer 1/2 (Brca1/2), ATM serine/threonine kinase (Atm), and RAD50 double strand break repair protein (Rad50) in mouse antral follicles [13]. These data suggest that phthalate or bisphenol exposed ovaries may not be equipped with the machinery to repair ROS-induced DNA damage.

Cell Death Pathways

Mouse-based studies demonstrate that bisphenol or phthalate exposure can increase apoptosis, or programmed cell death, in vivo and in vitro [8, 18, 19, 22, 24, 25]. Further, exposure to BPA or an environmentally relevant mixture of phthalate metabolites is associated with increases in caspase expression/cleavage and/or shifts in expression of pro- and anti-apoptotic factors in mouse ovaries [8, 20, 22]. Additionally, bisphenols and phthalates can induce autophagy in mouse ovarian tissues [10, 22]. Autophagy is a process by which damaged cellular components are degraded, often leading to cell death [26]. DEHP induces autophagy in the mouse ovary through activation of 5’ AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and downstream factors S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 (SKP2) and coactivator associated arginine methyltransferase 1 (CARM1) [10].

Epigenetic Modifications

Plasticizer exposure has been shown to cause epigenetic modifications. In pregnant mouse dams dosed with BPS, analysis of oocytes isolated from the F1 generation showed decreased histone H3 lysine K4 (H3K4) methylation and increased histone H3 lysine K9 (H3K9) methylation compared to controls [6]. H3K4 methylation is considered a mark of active transcription, whereas H3K9 methylation is associated with transcriptional repression [27]. Another study demonstrated that BPA decreased expression of histone deacetylase 7 (HDAC7) in mouse ovarian follicles and increased global acetylation of H3K9 and histone H4 lysine K12 (H4K12) in isolated oocytes [28]. Rattan et al. (2019) showed that exposing pregnant mouse dams to DEHP increases global DNA methylation in the resulting F1 generation and decreases methylation in the F3 generation, suggesting that plasticizer-induced epigenetic changes are transgenerational [29]. Collectively, these studies suggest that phthalate/bisphenol induced changes in methylation or acetylation could be altering chromatin conformation, resulting in aberrant gene expression.

Effects of plasticizers on steroidogenesis

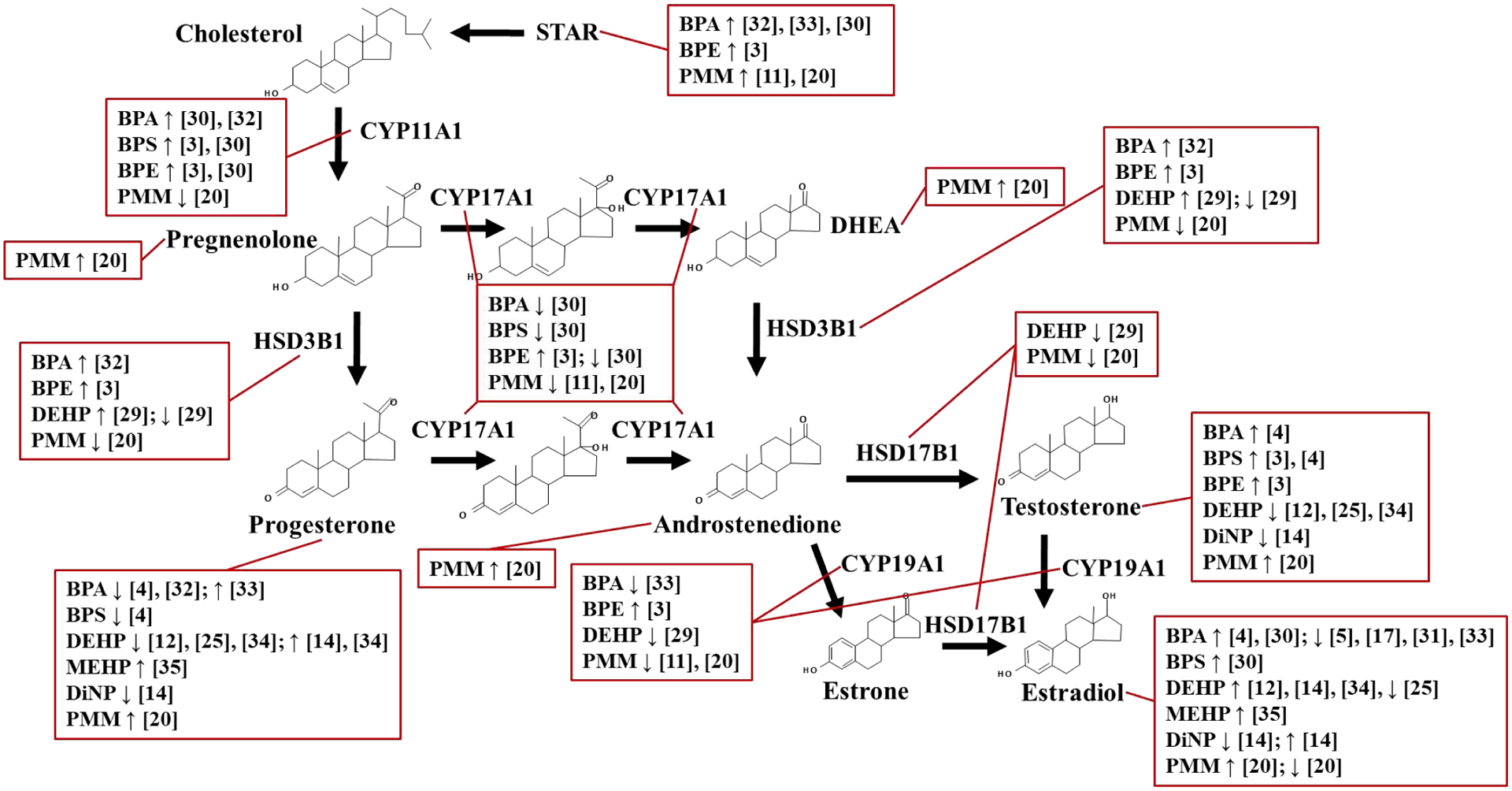

The ovary is the primary source of progestins, estrogens, and androgens that are critical for maintaining reproductive health and fertility. These sex steroid hormones are produced by the concerted actions of steroidogenic enzymes located in the theca and granulosa cells of the ovarian follicle [1]. These steroidogenic enzymes and the hormones they produce are depicted in Figure 2. The process of steroidogenesis is highly susceptible to the endocrine disrupting actions of plasticizers (Table 2). In rodents, gestational/neonatal exposure to BPA, as well as its replacement chemicals BPE and BPS can disrupt steroidogenesis by increasing testosterone production and dysregulating expression of steroidogenic enzymes, including steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (Star) and cytochrome P450 family 17 subfamily A member 1 (Cyp17a1) [3, 4]. Furthermore, gestational exposure to bisphenols can have transgenerational effects, leading to increased circulating estradiol levels and altered expression of steroidogenic enzymes cytochrome P450 family 11 subfamily A member 1 (Cyp11a1), and Cyp17a1 in F3 female mice [30]. Similarly, adult exposure to BPA decreases estradiol production in mice [31].

Figure 2. Effects of bisphenols and phthalates on steroidogenesis.

Current studies demonstrate bisphenols and phthalates can alter steroidogenesis by dysregulating expression of steroidogenic enzymes and altering steroid hormone production. Major findings from these studies are summarized here. ↓ indicate decreased and ↑ indicate increased gene/protein expression or hormone production relative to vehicle controls. PMM refers to studies performed with phthalate metabolite mixtures.

Table 2:

Effects of bisphenols and phthalates on steroidogenesis

| Chemical | Model | Exposure | Main Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPA | Mouse | Perinatal Exposure | ||

| 0, 0.5, 20, or 5μg/kg/d administered orally to pregnant females GD11-birth; euthanized at 3, 6, or 9 months |

|

[3] | ||

| 0, 0.5, 20, or 50μg/kg/d administered orally to pregnant females GD11-birth F3 females were euthanized at 3, 6, or 9 months of age | 3 month

|

[30] | ||

6 months

| ||||

9 months

| ||||

| Adult Exposure | ||||

| 0, 5, 50, or 500μg/kg/d administered to 6 week old mice for 28 days; euthanized immediately |

|

[31] | ||

| In Vitro Exposure | ||||

| Preantral follicles cultured in vitro with 0, 4.5, or 45μM for 8, or 10 days |

|

[17] | ||

| Rat | Perinatal Exposure | |||

| 0, 2.5, 25, 250, 2500, or 25000μg/kg/day administered by gavage from GD6-1 year, euthanized immediately |

|

[5] | ||

| 0, 0.5, 5, or 50mg/kg subcutaneously PND 1–10, euthanized PND75 |

|

[4] | ||

| In Vitro Exposure | ||||

| Granulosa cells cultured in vitro with 0, 0.1, 1, 10, 50, or 100μM for 24–48 hours |

|

[32] | ||

| Human | In Vitro Exposure | |||

| Cumulus granulosa cells cultured in vitro with 0, 0.000001, 0.001, 1, or 100μM BPA for 48 hours |

|

[33] | ||

| BPE | Mouse | Perinatal Exposure | ||

| 0, 0.5, 20, or 50μg/kg/d administered orally to pregnant females GD11-birth; euthanized at 3, 6, or 9 months | 3 months

|

[3] | ||

6 months

| ||||

9 months

| ||||

| 0, 0.5, 20, or 50μg/kg/d administered orally to pregnant females GD11-birth F3 females were euthanized at 3, 6, or 9 months of age | 3 month

|

[30] | ||

6 months

| ||||

9 months

| ||||

| BPS | Mouse | Perinatal Exposure | ||

| 0, 0.5, 20, or 50μg/kg/d administered orally to pregnant females GD11-birth; euthanized at 3, 6, or 9 months | 3 months

|

[3] | ||

6 months

| ||||

9 months

| ||||

| 0, 0.5, 20, or 50μg/kg/d administered orally to pregnant females GD11-birth F3 females were euthanized at 3, 6, or 9 months of age | 3 month

|

[30] | ||

6 months

| ||||

9 months

| ||||

| Rat | Perinatal Exposure | |||

| 0, 0.5, 5, or 50mg/kg subcutaneously PND1–10, euthanized PND75 |

|

[4] | ||

| DEHP | Mouse | Perinatal Exposure | ||

| 0, 0.02, 0.2, 200, 500, or 750mg/kg/day administered orally to pregnant mice GD10.5-birth F1, F2, and F3 females were euthanized on PND8, 21, or 60 | F1

|

[34] | ||

F2

| ||||

F3

| ||||

| 0, 0.02, 0.2, 500, or 750mg/kg/day administered orally to pregnant mice GD10.5-birth F1, F2, and F3 females were euthanized on PND21 | F1

|

[29] | ||

F2

| ||||

F3

| ||||

| 0, 0.02, 0.2, 500, and 750mg/kg/d administered orally to pregnant dams GD11-birth F1, F2, and F3 generation females were euthanized at 12 months | F1

|

[12] | ||

F2

| ||||

F3

| ||||

| Adult Exposure | [14] | |||

| 0, 0.02, 0.2, 20, or 200mg/kg/d administered orally to 40 day old females for 10 days, euthanized either immediately or 3, 6, or 9 months post-dosing | Immediate

|

|||

3 months post-dosing

| ||||

6 months post-dosing

| ||||

9 months post-dosing

| ||||

| Rat | Adult Exposure | |||

| 0, 300, 1000, or 3000mg/kg/d administered orally to adult rats for 4 weeks; euthanized immediately |

|

[25] | ||

| DiNP | Mouse | Adult Exposure | ||

| 0, 0.02, 0.1, 20, or 200mg/kg/d administered orally to 40 day old females for 10 days, euthanized either immediately or 3, 6, or 9 months post-dosing | Immediate

|

[14] | ||

3 months post-dosing

| ||||

6 months post-dosing

| ||||

9 months post-dosing

| ||||

| MEHP | Rat | In Vitro Exposure | ||

| Granulosa cells cultured in vitro with 0, 25, 50, 100, or 200μM for 24 hours |

|

[35] | ||

| Phthalate Metabolite Mixture | Mouse | Perinatal Exposure | ||

| 0, 10, 100, or 500x of phthalate metabolite mixture (SELMA study; 33% MBP, 16% MBzP, 21% MEHP, 30% MINP) administered orally to pregnant dams from GD0.5 to birth pups euthanized PND21 and PND90 | PND21

|

[11] | ||

PND90

| ||||

| In Vitro Exposure | ||||

| Antral follicles cultured in vitro with 0, 0.065, 0.65, 6.5, 65, or 325μg/ml of a phthalate metabolite mixture (36.7% MEP, 19.4% MEHP, 15.3% MBP, 10.2% MiBP, 10.2% MiNP, and 8.2% MBzP) for 24 or 96 hours | 24 hours hormone levels

|

[20] | ||

24 hours steroidogenic enzyme expression

| ||||

96 hours hormone levels

| ||||

96 hours steroidogenic enzyme expression

|

In vitro, BPA exposure can affect steroidogenesis by decreasing estradiol production in cultured mouse preantral follicles [17]. In primary rat granulosa cells, BPA decreased levels of progesterone and increased expression of Star, and these effects were partially reversed by co-treatment with cholesterol, suggesting that BPA may be impairing steroidogenesis by disrupting cholesterol homeostasis [32]. In contrast, BPA exposure increased progesterone in human cumulus granulosa cells [33]. This was accompanied by increased Star expression that was dependent on peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma (PPARG), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) activity [33]. These data suggest that the effects of BPA on steroidogenesis may be species specific.

Recent studies have demonstrated endocrine disrupting effects of phthalates on steroidogenesis. Gestational exposure to DEHP in mice can alter steroidogenesis in multiple generations, leading to increased estradiol and decreased testosterone levels in the F1 generation, and decreased progesterone levels in the F2 generation [12, 34]. Additionally, gestational DEHP exposure can induce transgenerational changes in the ovarian expression of steroidogenic enzymes, including hydroxysteroid 3-beta dehydrogenase 1 (Hsd3b1), hydroxysteroid 17-beta dehydrogenase 1 (Hsd17b1), cytochrome P450 family 19 subfamily A member 1 (Cyp19a1), and cytochrome P450 family 1 subfamily B member 1 (Cyp1b1) [29]. Repouskou et al., (2019) reported that gestational exposure to a mixture of epidemiologically defined phthalate metabolites did not alter circulating estradiol, but it decreased expression of steroidogenic enzymes Cyp19a1 and Cyp17a1 at 21 and 90 days post exposure in mice, respectively [11]. Adult exposure to DEHP or the DEHP replacement chemical DiNP altered levels of estradiol, progesterone, and testosterone compared to control mice and these altered hormone levels persisted up to 9 months post exposure [14].

In vitro, mouse antral follicles exposed to an environmentally relevant mixture of phthalate metabolites containing monoethyl phthalate (MEP), mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP), monobutyl phthalate (MBP), monoisobutyl phthalate (MiBP), monoisononyl phthalate (MiNP), and monobenzyl phthalate (MBzP) secreted lower concentrations of estradiol and higher concentrations of progesterone and testosterone than vehicle exposed follicles [20]. These changes in hormone levels were coupled with increased expression of Star and cytochrome P450 family 1 subfamily A member 1 (Cyp1a1) and decreased expression of Cyp19a1 compared to control [20]. In contrast, MEHP exposure in vitro increased both estradiol and progesterone production in primary rat granulosa cells compared to control [35]. This difference in estradiol response could be due to the net effect of multiple phthalates in the former study, a lack of theca-granulosa communication in the latter study, and/or potential inter-species differences existing between mice and rats [20, 35].

Effects of plasticizers on reproductive outcomes

Current data indicate that bisphenols and phthalates can affect different parameters of female reproduction and fertility. In mice, gestational exposure to BPA, BPE, or BPS accelerated the onset of puberty, disrupted estrous cyclicity, reduced pregnancy rate, and reduced the number of mouse pups born compared to controls [3]. In contrast, neonatal exposure to either BPA or BPS delayed onset of puberty in rats [4]. The differences observed in these studies could be attributed to different windows of exposure (gestational vs. neonatal) or inter-species differences between mice and rats in response to toxicants [3, 4]. Transgenerational studies show that exposing pregnant mouse dams to BPA, BPE, or BPS can impact the reproductive function of F3 generation females, by accelerating the onset of puberty, disrupting the estrous cycle, and reducing pregnancy rate [30]. Similarly, gestational exposure to DEHP can exert transgenerational effects by altering estrous cyclicity in the F1 and F3 generations in mice [12]. In adults, exposure to DEHP (in mice and rats) or DiNP (in mice) has been shown to alter estrous cyclicity [15, 25, 36]. These changes in cyclicity, along with reduced fertility, can persist long after termination of DEHP or DiNP exposure [15, 36].

Correlation between plasticizer exposure and reproductive pathology in humans

Recent studies suggest links between plasticizer exposure and known reproductive pathologies in human populations. Indeed, epidemiological studies support a link between phthalate exposure and the occurrence of infertility. Detectable levels of phthalate metabolites (MEHP, MBP, MEP, and MBzP) were measured in the follicular fluid of women undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF) [37, 38]. Moreover, higher concentrations of metabolites like mono-methyl phthalate (MMP), MEP, and MEHP were correlated with lower concentrations of steroid hormones in the follicular fluid of these women [38]. Recent data demonstrate that mouse ovarian follicles can metabolize parent phthalates into their monoester metabolites [39]. Elevated levels of phthalate metabolites in follicular fluid may be due to local metabolism within the ovary. Other studies have detected higher levels of BPA, MiBP, and MBP in follicular fluid, urine, and serum, respectively, from women presenting with diminished ovarian reserve compared to samples from fertile women [31, 40, 41].

Interestingly, recent rodent studies have shown increased incidence of ovarian cyst formation upon exposure to plasticizers [10, 12, 42, 43]. Cystic ovaries, along with chronic anovulation and hyperandrogenism, are classic features of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) [44]. Elevated levels of BPA in urine and serum and DEHP in follicular fluid were detected in samples from women with PCOS compared to women without PCOS [45–48]. BPA positively correlated with higher testosterone and free androgen index (measure of testosterone relative to sex hormone binding globulin) in women with PCOS [47]. Hyperinsulinemia and peripheral insulin resistance are also observed in a subset of women diagnosed with PCOS [44]. Elevated urinary BPA was positively associated with serum insulin levels and incidence of insulin resistance [45]. Together, these observations suggest that plasticizer exposure could be a contributing factor in the etiology of PCOS and subfertility/infertility.

Conclusions

It is well established that plasticizers are endocrine disrupting chemicals with deleterious effects on ovarian health. Current studies document changes in follicle populations signifying impaired folliculogenesis and dysregulation of steroid hormone production following bisphenol or phthalate exposure (Figures 1 and 2, respectively). Based on these studies, it is critical to assess the continued use of phthalates and bisphenols in consumer products because they exhibit clear ovotoxicity, their effects can persist long after termination of exposure, they can impact multiple generations with one window of exposure, and they may play a role in the development of reproductive diseases like PCOS.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants T32 ES007326, R01 ES030206, and R01 ES028661.

Abbreviations

- AMPK

5’ AMP-activated protein kinase

- ATM

ATM serine/threonine kinase

- BPA

bisphenol A

- BPE

bisphenol E

- BPS

bisphenol S

- BMP15

bone morphogenetic protein 15

- BRCA1/2

breast cancer 1/2

- CAT

catalase

- CARM1

coactivator associated arginine methyltransferase 1

- CYP1A1

cytochrome P450 family 1 subfamily A member 1

- CYP1B1

cytochrome P450 family 1 subfamily B member 1

- CYP11A1

cytochrome P450 family 11 subfamily A member 1

- CYP17A1

cytochrome P450 family 17 subfamily A member 1

- CYP19A1

cytochrome P450 family 19 subfamily A member 1

- DHEA

dehydroepiandrosterone

- DBP

dibutyl phthalate

- DEHP

di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate

- DiNP

diisononyl phthalate

- EDC

endocrine disrupting chemicals

- F#

filial generation

- GD

gestational day

- GPX1

glutathione peroxidase

- GDF9

growth/differentiation factor 9

- HDAC7

histone deacetylase 7

- H3K4

histone H3 lysine K4

- H3K9

histone H3 lysine K9

- H4K12

histone H4 lysine K12

- HSD3B1

hydroxysteroid 3-beta dehydrogenase 1

- HSD17B1

hydroxysteroid 17-beta dehydrogenase 1

- MBP

monobutyl phthalate

- MBzP

monobenzyl phthalate

- MEP

monoethyl phthalate

- MEHP

mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate

- MiBP

monoisobutyl phthalate

- MiNP

monoisononyl phthalate

- MMP

mono-methyl phthalate

- PCOS

polycystic ovarian syndrome

- PND

post-natal day

- RAD50

RAD50 double strand break repair

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SOD1

superoxide dismutase

- SKP2

S-phase kinase-associated protein 2

- STAR

steroidogenic acute regulatory protein

- XDH

xanthine dehydrogenase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have nothing to declare.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Damdimopoulou P, Chiang C, and Flaws JA, Retinoic acid signaling in ovarian folliculogenesis and steroidogenesis. Reprod Toxicol, 2019. 87: p. 32–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hannon PR and Flaws JA, The effects of phthalates on the ovary. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2015. 6: p. 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi M, et al. , Prenatal Exposure to Bisphenol A Analogues on Female Reproductive Functions in Mice. Toxicol Sci, 2019. 168(2): p. 561–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study showed gestational exposure to BPA, BPE, or BPS disrupts folliculogenesis, alters production of steroid hormones and expression of steroidogenic enzymes, and negatively impacts fertility later in life. This study provides insight into the consequences of in utero exposure to bisphenols and how they manifest during the reproductive phase of an individual’s life.

- 4.Ahsan N, et al. , Comparative effects of Bisphenol S and Bisphenol A on the development of female reproductive system in rats; a neonatal exposure study. Chemosphere, 2018. 197: p. 336–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heindel JJ, et al. , Data integration, analysis, and interpretation of eight academic CLARITY-BPA studies. Reprod Toxicol, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang MY, et al. , Maternal Bisphenol S exposure affects the reproductive capacity of F1 and F2 offspring in mice. Environ Pollut, 2020. 267: p. 115382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nevoral J, et al. , Long-term exposure to very low doses of bisphenol S affects female reproduction. Reproduction, 2018. 156(1): p. 47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu X, et al. , Effects of bisphenol A on ovarian follicular development and female germline stem cells. Arch Toxicol, 2018. 92(4): p. 1581–1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.López-Rodríguez D, et al. , Persistent vs Transient Alteration of Folliculogenesis and Estrous Cycle After Neonatal vs Adult Exposure to Bisphenol A. Endocrinology, 2019. 160(11): p. 2558–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, et al. , Foetal-neonatal exposure of Di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate disrupts ovarian development in mice by inducing autophagy. J Hazard Mater, 2018. 358: p. 101–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Repouskou A, et al. , Gestational exposure to an epidemiologically defined mixture of phthalates leads to gonadal dysfunction in mouse offspring of both sexes. Sci Rep, 2019. 9(1): p. 6424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brehm E, et al. , Prenatal Exposure to Di(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate Causes Long-Term Transgenerational Effects on Female Reproduction in Mice. Endocrinology, 2018. 159(2): p. 795–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu X and Craig ZR, Environmentally relevant exposure to dibutyl phthalate disrupts DNA damage repair gene expression in the mouse ovary†. Biol Reprod, 2019. 101(4): p. 854–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiang C, et al. , Exposure to di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate and diisononyl phthalate during adulthood disrupts hormones and ovarian folliculogenesis throughout the prime reproductive life of the mouse. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2020. 393: p. 114952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiang C, et al. , Late-life consequences of short-term exposure to di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate and diisononyl phthalate during adulthood in female mice. Reprod Toxicol, 2020. 93: p. 28–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study showed that short-term exposure to DEHP and DiNP during adulthood can impaired folliculogenesis and altered steroidogenesis up to 9 months after termination of exposure. These findings demonstrate that even brief exposure to phthalates like DEHP or DiNP can have long lasting effects on ovarian function.

- 16.Acuña-Hernández DG, et al. , Bisphenol A alters oocyte maturation by prematurely closing gap junctions in the cumulus cell-oocyte complex. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2018. 344: p. 13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X, et al. , Interfering effects of bisphenol A on in vitro growth of preantral follicles and maturation of oocyes. Clin Chim Acta, 2018. 485: p. 119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tu Z, et al. , Dibutyl phthalate exposure disrupts the progression of meiotic prophase I by interfering with homologous recombination in fetal mouse oocytes. Environ Pollut, 2019. 252(Pt A): p. 388–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li FP, et al. , Di(n-butyl) phthalate exposure impairs meiotic competence and development of mouse oocyte. Environ Pollut, 2019. 246: p. 597–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meling DD, et al. , The effects of a phthalate metabolite mixture on antral follicle growth and sex steroid synthesis in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2020. 388: p. 114875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rasmussen LM, et al. , Effects of in vitro exposure to dibutyl phthalate, mono-butyl phthalate, and acetyl tributyl citrate on ovarian antral follicle growth and viability. Biol Reprod, 2017. 96(5): p. 1105–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jia Z, et al. , Fluorene-9-bisphenol exposure induces cytotoxicity in mouse oocytes and causes ovarian damage. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf, 2019. 180: p. 168–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang M, et al. , Bisphenol A and its analogues bisphenol S, bisphenol F and bisphenol AF induce oxidative stress and biomacromolecular damage in human granulosa KGN cells. Chemosphere, 2020. 253: p. 126707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu JC, et al. , Identification of oxidative stress-related Xdh gene as a di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP) target and the use of melatonin to alleviate the DEHP-induced impairments in newborn mouse ovaries. J Pineal Res, 2019. 67(1): p. e12577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study showed that in neonatal ovaries, DEHP induced ROS accumulation and apoptosis, which were mediated by upregulation of the oxidative stress related gene XDH. This study provides insight into the mechanims of action of DEHP in the ovary.

- 25.Li N, et al. , Role of the 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase signalling pathway in di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate-induced ovarian dysfunction: An in vivo study. Sci Total Environ, 2020. 712: p. 134406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Y and Levine B, Autosis and autophagic cell death: the dark side of autophagy. Cell Death Differ, 2015. 22(3): p. 367–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hyun K, et al. , Writing, erasing and reading histone lysine methylations. Exp Mol Med, 2017. 49(4): p. e324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu B, et al. , Bisphenol A deteriorates egg quality through HDAC7 suppression. Oncotarget, 2017. 8(54): p. 92359–92365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rattan S, et al. , Prenatal and ancestral exposure to di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate alters gene expression and DNA methylation in mouse ovaries. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2019. 379: p. 114629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study showed that gestational exposure to DEHP has transgenerational effects on steroidogenesis, cell cycle regulation, and cell signaling. Additionally, DEHP altered global DNA methylation in multiple generations. This study provides insight into the epigenetic effects of DEHP exposure in multiple generations.

- 30.Shi M, et al. , Prenatal Exposure to Bisphenol A, E, and S Induces Transgenerational Effects on Female Reproductive Functions in Mice. Toxicol Sci, 2019. 170(2): p. 320–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao Y, et al. , The correlation between exposure to BPA and the decrease of the ovarian reserve. Int J Clin Exp Pathol, 2018. 11(7): p. 3375–3382. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Samardzija D, et al. , Bisphenol A decreases progesterone synthesis by disrupting cholesterol homeostasis in rat granulosa cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 2018. 461: p. 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pogrmic-Majkic K, et al. , BPA activates EGFR and ERK1/2 through PPARγ to increase expression of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein in human cumulus granulosa cells. Chemosphere, 2019. 229: p. 60–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study demonstrated that BPA altered steriodogenesis in primary human granulosa cells by increasing progesterone levels and expression of STAR and decreasing estradiol levels and expression of CYP19A1. BPA alters STAR expression through a mechanism involving EGFR and PPARG activation and ERK1/2 phosphorylation. This work provides insight into the mechanism of action of BPA in the ovary.

- 34.Rattan S, et al. , Prenatal exposure to di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate disrupts ovarian function in a transgenerational manner in female mice. Biol Reprod, 2018. 98(1): p. 130–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li N, et al. , Effect of mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP) on proliferation of and steroid hormone synthesis in rat ovarian granulosa cells in vitro. J Cell Physiol, 2018. 233(4): p. 3629–3637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chiang C and Flaws JA, Subchronic Exposure to Di(2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate and Diisononyl Phthalate During Adulthood Has Immediate and Long-Term Reproductive Consequences in Female Mice. Toxicol Sci, 2019. 168(2): p. 620–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuan XQ, et al. , Phthalate metabolites and biomarkers of oxidative stress in the follicular fluid of women undergoing in vitro fertilization. Sci Total Environ, 2020. 738: p. 139834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Du Y, et al. , Follicular fluid concentrations of phthalate metabolites are associated with altered intrafollicular reproductive hormones in women undergoing in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril, 2019. 111(5): p. 953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warner GR, et al. , Ovarian Metabolism of an Environmentally Relevant Phthalate Mixture. Toxicol Sci, 2019. 169(1): p. 246–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao M, et al. , Urinary levels of phthalate metabolites in women associated with risk of premature ovarian failure and reproductive hormones. Chemosphere, 2020. 242: p. 125206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Özel Ş, et al. , Serum levels of phthalates and bisphenol-A in patients with primary ovarian insufficiency. Gynecol Endocrinol, 2019. 35(4): p. 364–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dabeer S, et al. , Transgenerational effect of parental obesity and chronic parental bisphenol A exposure on hormonal profile and reproductive organs of preadolescent Wistar rats of F1 generation: A one-generation study. Hum Exp Toxicol, 2020. 39(1): p. 59–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou C, Gao L, and Flaws JA, Exposure to an Environmentally Relevant Phthalate Mixture Causes Transgenerational Effects on Female Reproduction in Mice. Endocrinology, 2017. 158(6): p. 1739–1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neven ACH, et al. , A Summary on Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Diagnostic Criteria, Prevalence, Clinical Manifestations, and Management According to the Latest International Guidelines. Semin Reprod Med, 2018. 36(1): p. 5–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Milanović M, et al. , Can environmental pollutant bisphenol A increase metabolic risk in polycystic ovary syndrome? Clin Chim Acta, 2020. 507: p. 257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akgül S, et al. , Bisphenol A and phthalate levels in adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol, 2019. 35(12): p. 1084–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Konieczna A, et al. , Serum bisphenol A concentrations correlate with serum testosterone levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Reprod Toxicol, 2018. 82: p. 32–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jin Y, et al. , The effects of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate exposure in women with polycystic ovary syndrome undergoing in vitro fertilization. J Int Med Res, 2019. 47(12): p. 6278–6293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]