Abstract

Introduction:

We recently developed an inducible model of dysphagia using intralingual injection of cholera toxin B conjugated to saporin (CTB-SAP) to cause death of hypoglossal neurons. In this study we aimed to evaluate tongue morphology and ultrastructural changes in hypoglossal neurons and nerve fibers in this model.

Methods:

Tissues were collected from 20 rats (10 control and 10 CTB-SAP animals) on day 9 post-injection. Tongues were weighed, measured, and analyzed for microscopic changes using laminin immunohistochemistry. Hypoglossal neurons and axons were examined using transmission electron microscopy.

Results:

The cross-sectional area of myofibers in the posterior genioglossus was decreased in CTB-SAP–injected rats. Degenerative changes were observed in both the cell bodies and distal axons of hypoglossal neurons.

Discussion:

Preliminary results indicate this model may have translational application to a variety of neurodegenerative diseases resulting in tongue dysfunction and associated dysphagia.

Keywords: denervation atrophy, dysphagia, motor neuron death, rodent models, ultrastructural changes

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Upper airway dysfunction in motor neuron diseases is predominantly attributed to degeneration of hypoglossal (XII) lower motor neurons that innervate the tongue, resulting in progressive muscle weakness and atrophy.1–7 As a result, speaking and swallowing become difficult and may lead to avoidance of social interaction, resulting in a diminished quality of life.8,9 Dysphagia, in particular, puts patients at risk of malnutrition, dehydration, and aspiration pneumonia.10–14 Although there are no therapies currently available to prevent or reverse hypoglossal degeneration, there is an emerging role for resistance exercise to preserve upper airway function.15–18 At this time, however, clinical management is predominantly symptom-based and includes diet consistency alteration and postural changes, noninvasive ventilation, and feeding tube placement and ventilator support.10,12,19 Collectively, the consequences of hypoglossal motor neuron degeneration underscore the need for accelerated treatment discovery to improve functional outcomes and quality of life.

We propose that it may be possible to delay the onset of upper airway dysfunction by coercing the surviving motor neurons to increase their output. Surviving neurons have an enhanced ability to exhibit plasticity after motor neuron loss.20–22 It remains unknown whether surviving hypoglossal motor neurons demonstrate this property, but it seems likely they would if there were an appropriate model available for study.

Toward that end, we recently developed an inducible model of hypoglossal motor neuron death.23 Previous rodent studies have shown that intralingual injections can be used to selectively target hypoglossal motor neurons.24–26 Other investigators have used cholera toxin B conjugated to saporin (CTB-SAP) to cause the death of preganglionic sympathetic neurons and phrenic motor neurons, whose axons were exposed to this retrograde tracer (CTB) bound to a ribosome-inactivating protein, saporin (SAP).27–30 We combined these approaches and injected CTB-SAP into the genioglossus of rats to cause deficits in hypoglossal motor neuron survival, hypoglossal motor output, and lick and swallow rates relative to controls,23 which enables comparisons with other motor neuron disease models.31–33 The controlled amount of dying versus spared hypoglossal motor neurons in CTB-SAP–treated rats, and absence of clinical signs unrelated to dysphagia/upper airway dysfunction, highlights the specificity of this model for investigating XII lower motor neuron regenerative strategies in an otherwise neurodegenerative environment.23

The purpose of the current study was to further explore the intralingual CTB-SAP model by examining structural and ultrastructural changes in the tongue, hypoglossal nucleus, and hypoglossal nerve. We hypothesized CTB-SAP rats would develop macroscopic and microscopic tongue atrophy34 and would have evidence of ultrastructural changes in degenerating hypoglossal neurons and axons. For microscopic analysis, we focused on the genioglossus muscle because it is the primary protrusor muscle of the tongue, and tongue protrusion is impaired in CTB-SAP–treated rats.23

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Animals

Adult (3–4 months old) male Sprague-Dawley rats (Envigo Colony 208; Indianapolis, Indiana) were housed in pairs, offered water and a standard pelleted diet ad libitum, and maintained under a standard 12:12 light:dark cycle. All procedures involving animals were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee at the University of Missouri and in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland).

2.2 |. Intralingual injections

All rats were anesthetized with isoflurane and given intralingual injections, as described elsewhere.23 Rats assigned to the CTB-SAP group (n = 10) received 25 μg CTB-SAP (dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]; Advanced Targeting Systems, San Diego, California) to produce hypoglossal motor neuron death, plus extra CTB (25 μg dissolved in doubly distilled water; Calbiochem, Billerica, Massachusetts) to label surviving hypoglossal motor neurons for future analysis. Animals in the control group (n = 10) were given CTB (25 μg) unconjugated to saporin (25 μg, dissolved in PBS; Advanced Targeting Systems).

The technique for administering the injections was also described previously.23 In brief, a nose cone was used to deliver isoflurane anesthesia (2%−3%) to rats placed in a supine position on a custom tilt table. The mouth was held open using a custom string pulley system with a loop placed over the mandibular incisors, and the tongue was gently protruded using fine forceps. Injections were administered via a 26-gauge needle inserted at a 45° angle into the base of the frenulum at the midline. Half of the bolus was delivered while the needle was at maximum depth (8 mm) and the remainder was given after it was retracted halfway (4 mm). The volume, injection site, and time-point were the same as in our previous study,23 as pilot studies using different volumes, injection sites, and time-points resulted in adverse side effects. For consistency, all injections were performed by the same investigator. Rats were then recovered from anesthesia and monitored for adverse reactions. All animals retained the ability to eat and drink adequately, and no additional fluids or medications were required.

2.3 |. Tongue morphometry

On day 9 after intralingual injection, 6 rats (3 controls, 3 CTB-SAP) were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and transcardially perfused with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.1 mol/L PBS (pH ~ 7.4). The tongues were collected and immediately prepared for macroscopic morphometric analysis by an investigator blinded to experimental group. The specimen to be analyzed consisted of all the intrinsic muscles of the tongue plus the following extrinsic muscles: genioglossus, geniohyoid, mylohyoid, and anterior digastric. The tongues were weighed and then photographed using a 16-megapixel camera. Images were captured of the dorsal, ventral, and lateral aspects of each tongue. Finally, the tongues were placed in a slide dryer (SD-11–120; Triangle Biomedical Sciences, Durham, North Carolina) at 57°C for 1 week and then reweighed to determine the dry weight.

Fiji software35 was used to measure 10 features of each tongue. Measurements on the dorsal aspect (Figure S1A) included length (total, posterior, anterior), width (posterior, middle, anterior), and area. The total length extended from the circumvallate papilla to the tip of the blade.36,37 The anterior border of the intramolar eminence provided the dividing line between the anterior and posterior regions36,37 and was the point at which the middle width measurement was made. On the lateral aspect (Figure S1B), measurements included area of the intrinsic muscles and area of the combined extrinsic muscles. The only measurement made on the ventral aspect (Figure S1C) was the area of the anterior digastric muscle.

2.4 |. Immunohistochemistry

Ten rats (5 control and 5 CTB-SAP animals) were anesthetized with isoflurane followed by urethane for a separate in vivo neurophysiology study (results not included here), which was also conducted on day 9 post-injection. As soon as those experiments were completed, the rats were perfused, and the tongues were collected, weighed, and photographed as described earlier. However, instead of being placed in the dryer, they were further fixed in 4% PFA for 2 to 3 days. The genioglossus was then isolated and divided into four sections (posterior, middle 1, middle 2, and anterior; Figure 2A), so all fibers of this fan-shaped muscle could be cut in cross-section. The tissue was paraffin processed and embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 10 μm with a microtome (Leica RM 2155; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany), and mounted on positively charged (silane-coated) slides. Three slides from each animal were selected to undergo immunohistochemistry and analysis.

FIGURE 2.

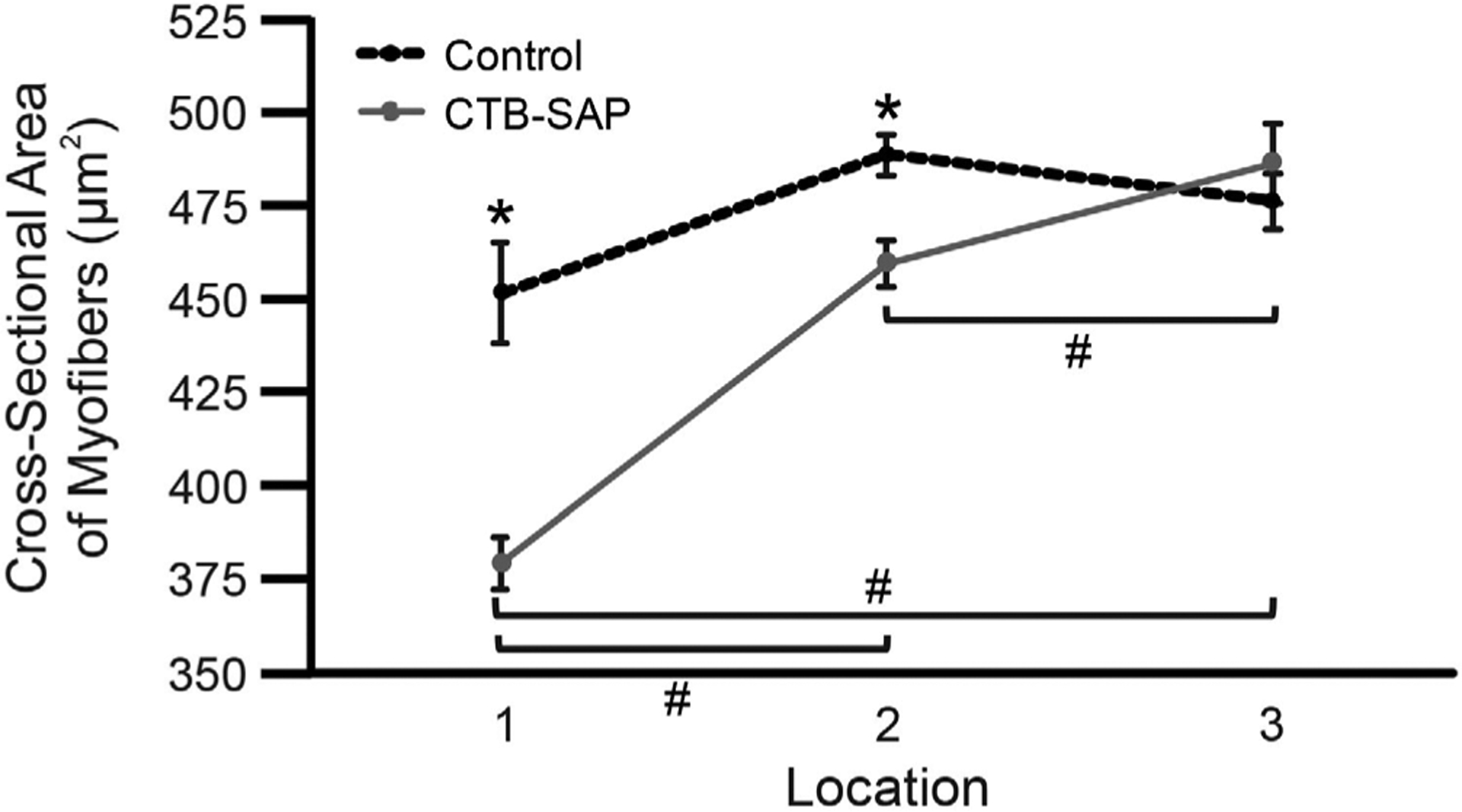

Cross-sectional areas of myofibers in 3 parts of the posterior genioglossus for control and CTB-SAP–treated rats. Line graph depicts the mean ± standard error of the mean for each experimental group and location. A linear mixed effects model fitted to these data indicates significant effects (P < 0.05) for both experimental group and location. Control rats (dotted black line) had larger myofibers than CTB-SAP–treated rats (solid gray line) in locations 1 and 2 (*P < 0.05). For CTB-SAP–treated animals only, there were significant differences in CSAs between all pairs of locations, with fibers in location 3 being the largest and fibers in location 1 being the smallest (#P < 0.05). Abbreviation: CTB-SAP, cholera toxin B conjugated to saporin

An antibody to laminin was chosen to highlight the basement membrane surrounding individual muscle fibers. To increase binding and further enhance contrast, antigen retrieval was conducted by incubating the slides in pepsin (Digest-All 3; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts) at 37°C for 10 minutes. Each slide was immediately rinsed with 1× PBS, fitted with a Shandon coverplate (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and placed in a Shandon Sequenza immunostaining center (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for the remainder of the procedure. The tissue was washed in 1× PBS three times for 5 minutes. To prevent non-specific antibody binding, a blocking solution consisting of 5% normal donkey serum (NDS), 0.1% Triton, and 1× PBS was applied for 1 hour at room temperature. The blocking solution was then replaced with a primary antibody solution and allowed to incubate at 4°C for 16 hours. The primary antibody solution consisted of 5% NDS, 1× PBS, 0.1% Triton, and an anti-laminin antibody (rabbit polyclonal, 1:100; Millipore Sigma, Burlington, Massachusetts). The following day, slides again underwent three 5-minute washes with 1× PBS before being immersed in a secondary antibody solution composed of 5% NDS, 1× PBS, 0.1% Triton, and secondary antibody (donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488, 1:1000; Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon). The tissue was then incubated in the secondary solution for 2 hours in the dark at room temperature before being subjected to a final round of three 5-minute washes in 1× PBS. The slides were then removed from the Sequenza rack. Prolong Gold Anti-fade Reagent (Molecular Probes) was applied to prevent quenching of fluorescence, and slides were coverslipped and allowed to dry flat in the dark before being stored at 4°C. Slides incubated without primary and secondary antibodies served as negative controls.

2.5 |. Histologic analysis

The initial plan was to sample all parts of the genioglossus (posterior, middle, and anterior), but that had to be adjusted once the tissue was sectioned and stained because large areas of degeneration/regeneration were present in all tongues sampled. This damage was observed in both control and CTB-SAP rats, so we believe it was caused by the injections themselves rather than an effect of the toxin. For this reason, every attempt was made to avoid these areas (predominantly midline) and select areas where fibers appeared to be relatively normal and healthy (generally more lateral). We focused our efforts on the posterior genioglossus because this is the largest section and the region most directly involved in tongue protrusion.38

Analysis was conducted on photomicrographs obtained using the 20× lens of an epifluorescence microscope (Leica DM 4000) and imaging software (Leica Application Suite version 4.3). A total of six images were captured for each rat: one each from the left and right genioglossus from each of three slides. The investigator was blinded to experimental group and was careful to image different regions of the tissue on each of the three slides from a given animal.

Fiji software35 was used to perform automated measurements of cross-sectional area (CSA) on muscle fibers. Each image was converted to 8-bit resolution and thresholded (between 15 and 35) to allow the fibers to be recognized and outlined by the software. To avoid including blood vessels and other structures, analysis was limited to fibers with CSAs between 75 and 2500 μm2 and a circularity greater than 0.3.39

2.6 |. Transmission electron microscopy imaging of hypoglossal nucleus and nerve

Four rats (2 controls and 2 CTB-SAP) were prepared for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging. Instead of 4% PFA, 2% PFA/2% glutaraldehyde in 100-mmol/L sodium cacodylate buffer was used for perfusion and tissue storage. The medulla and the distal end of the left hypoglossal nerve (~5 mm) were collected, stored in PFA/glutaraldehyde, and delivered to the Electron Microscopy Core Facility at the University of Missouri for TEM processing. We only examined the left hypoglossal nerve because our previous research showed that hypoglossal motor neuron death is symmetric after intralingual CTB-SAP injection.23 Samples were sectioned into 85-nm cross-sections using an ultramicrotome, and images were acquired with a TEM microscope (JEM 1400; JEOL, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) at 80 kV using a CCD camera (Ultrascan 1000; Gatan, Inc, Pleasanton, California).

2.7 |. Statistical analysis

Macroscopic tongue measurements (weight, area, length, and width) for control and CTB-SAP rats had a normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk) with equal variance (Brown-Forsythe), except for a few parameters with minor outliers (Grubb test). These data were analyzed both by excluding the outliers to perform a t test and by including the outliers and performing a Mann-Whitney U test. The results were the same either way; therefore, all data are included here to illustrate the full range. These analyses were completed using SigmaPlot version 14.0 (Systat Software, Inc, San Jose, California), and differences between groups were considered significant at P < 0.05 (two-tailed test). All values are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) as calculated with outliers included.

There was substantial inter- and intra-animal variability that had to be considered for the histologic analysis (see statistical data in the Supporting Information online). In addition, the fiber CSA data were not normally distributed, and there were statistically significant differences among the means for images taken from the same rat. When we investigated this further, we noticed that images taken from the “top” part of the posterior section (as it was oriented on the slide and labeled number 1 on Figure S2) appeared to have smaller fibers than those taken from the middle or bottom. To determine whether this was true, we assigned each image from the posterior genioglossus to one of three locations (1 = top, 2 = middle, 3 = bottom; Figure S2) before performing additional analyses. Because measurements were taken from the same animal in multiple locations, and to account for any inherent variability between the rats, a mixed effects model (which included group and location as fixed effects, and the group × location interaction term) with a random intercept for each rat was fitted (see statistical data in the Supporting Information online). These statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4.1 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, North Carolina), and differences between groups were considered significant at P < 0.05 (two-tailed test).

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Macroscopic atrophy undetectable on day 9 after intralingual CTB-SAP injection

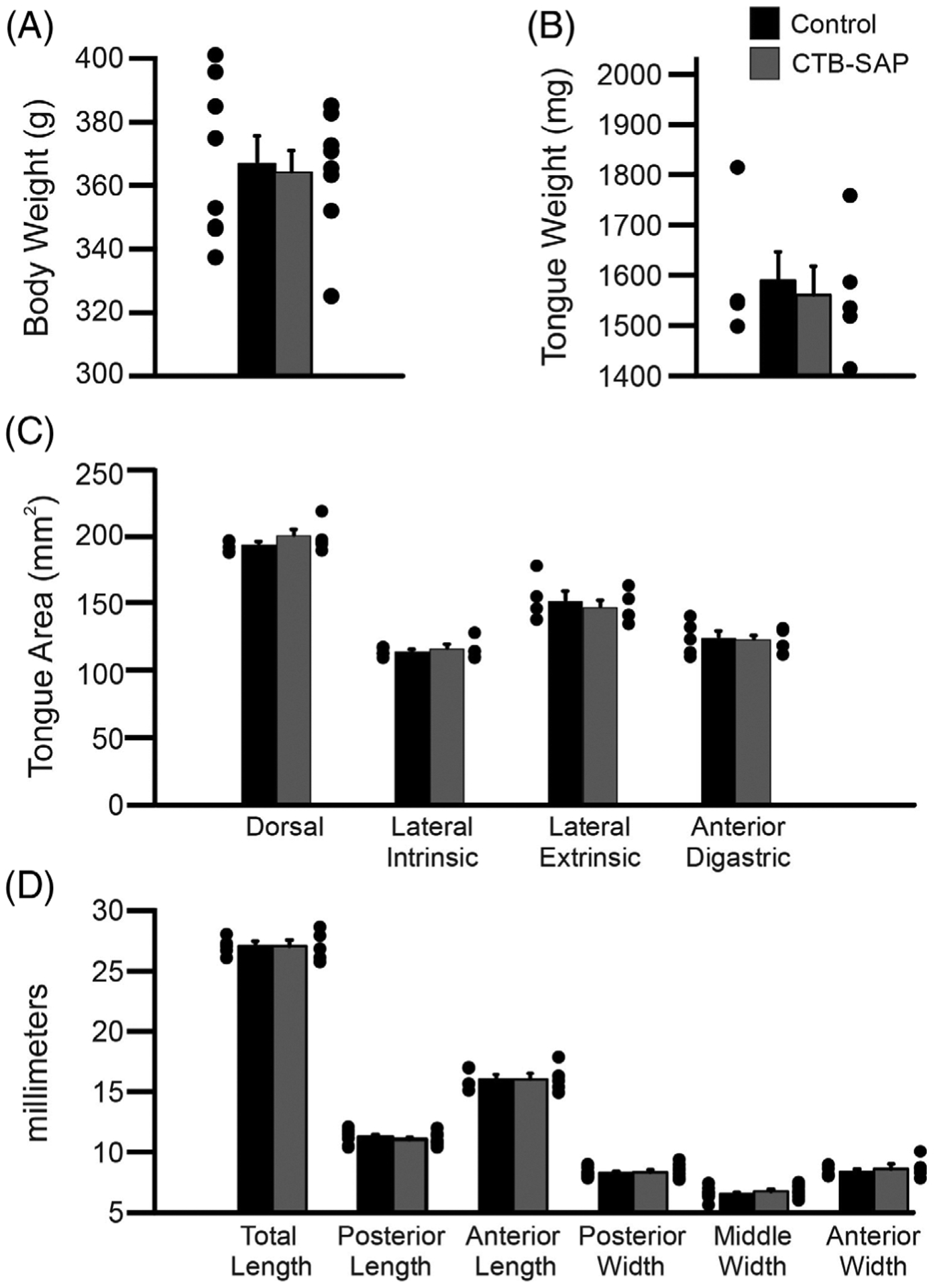

There was no significant difference in body weight between control and CTB-SAP–treated rats (367 ± 9 vs 364 ± 7 g; P > 0.05; Figure 1A). There was also no significant difference in tongue weight, either wet (1589 ± 57 vs 1561 ± 57 mg; P > 0.05; Figure 1B) or dry (317 ± 8 vs 335 ± 7 mg; P > 0.05; data not shown). Multiple measurements were made on the dorsal, lateral, and ventral aspects of the tongue, but none showed significant differences between control and CTB-SAP–treated rats. Measurements on the dorsal aspect included the following: area (194 ± 2 vs 201 ± 5 mm2; P > 0.05; Figure 1C); total length (27.1 ± 0.3 vs 27.0 ± 0.5 mm; P > 0.05; Figure 1D); posterior length (11.3 ± 0.2 vs 11.0 ± 0.2 mm; P > 0.05; Figure 1D); anterior length (16.0 ± 0.4 vs 16.0 ± 0.5 mm; P > 0.05; Figure 1D); posterior width (8.3 ± 0.1 vs 8.3 ± 0.2 mm; P > 0.05; Figure 1D); middle width (6.5 ± 0.2 vs 6.7 ± 0.2 mm; P > 0.05; Figure 1D); and anterior width (8.4 ± 0.2 vs 8.6 ± 0.4 mm; P > 0.05; Figure 1D). The lateral measurements consisted of the intrinsic muscle area (114 ± 2 vs 116 ± 3 mm2; P > 0.05; Figure 1C) and extrinsic muscle area (152 ± 7 vs 148 ± 5 mm2; P > 0.05; Figure 1C). The only measure on the ventral aspect was the anterior digastric area (125 ± 6 vs 123 ± 4 mm2; P > 0.05; Figure 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Macroscopic tongue measurements in control and CTB-SAP–treated rats. There was no significant difference (P > 0.05) in size of control (black bars) and CTB-SAP–treated rats (gray bars) for any of the macroscopic measurements analyzed, including: body weight (A), tongue weight (B), tongue area (C), and tongue length and width (D). Data show mean ± standard error of the mean plus dot plots for individual data points. Abbreviation: CTB-SAP, cholera toxin B conjugated to saporin

3.2 |. CSA of myofibers in posterior genioglossus decreased in intralingual CTB-SAP–treated rats, especially in more anterior fibers

Figure S2 shows a typical example of laminin-stained tissue from a control rat and CTB-SAP–treated rat. The overall findings are depicted graphically in Figure 2, which illustrates the mean CSA of myofibers in 3 parts of the posterior genioglossus. The linear mixed effects model indicates significant effects of both experimental group (P < 0.05) and location (P < 0.05). Generally, controls had larger myofibers than CTB-SAP–treated animals, and fibers in the more posterior part of the muscle were larger than those in the more anterior part, but there was also a significant group × location interaction effect (P < 0.05).

3.3 |. Intralingual CTB-SAP caused degeneration in hypoglossal nucleus and nerve

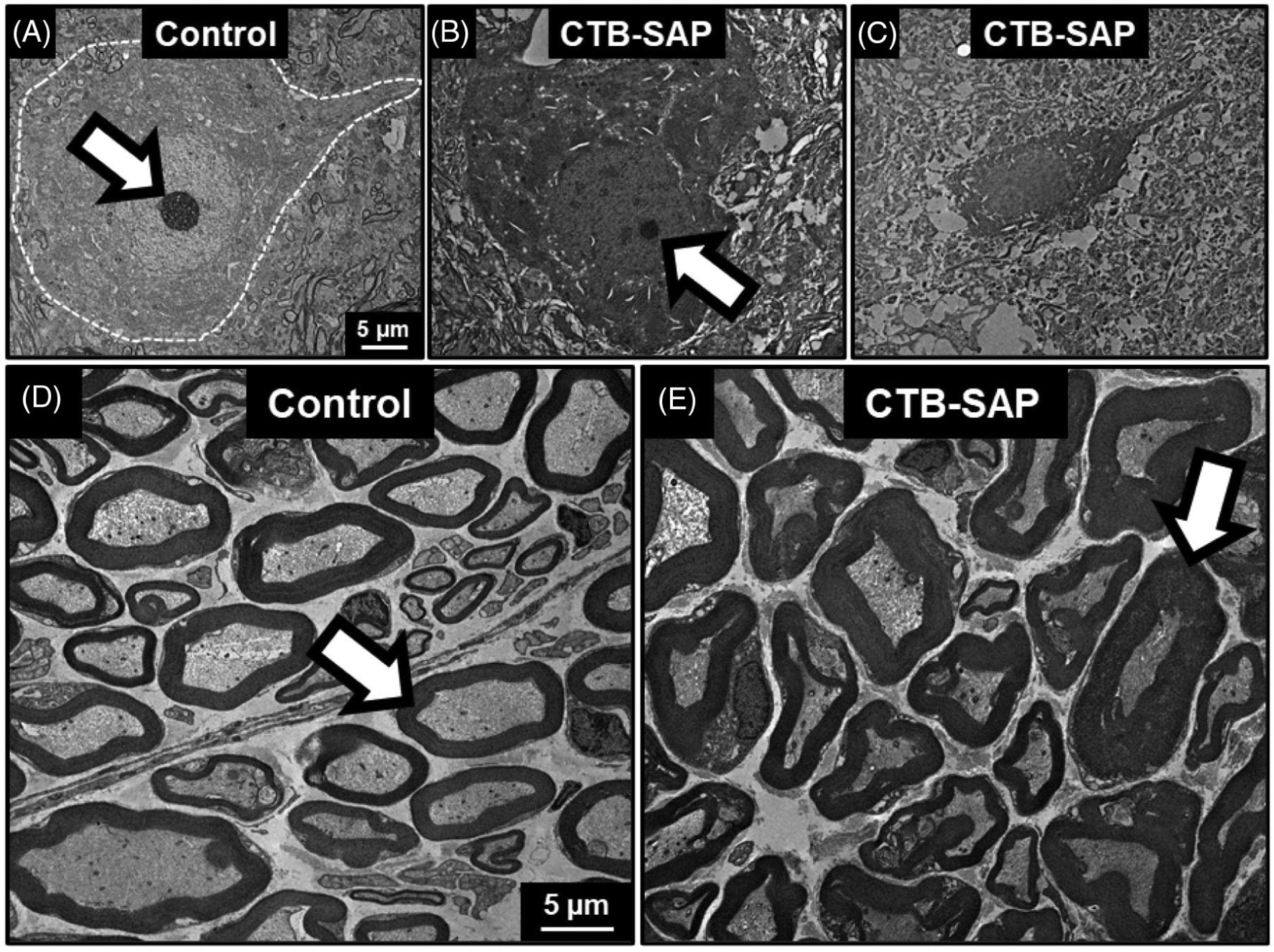

In this study, we used TEM to further describe degenerative changes after intralingual CTB-SAP (Figure 3). Unlike control animals (Figure 3A), the CTB-SAP rats (Figure 3B,C) showed many dead/dying neurons with small nucleoli, decreased cell size, increased nucleus: cytoplasm ratio, and indistinct cell borders. Corresponding changes were noted in the distal hypoglossal nerve. In the control rat (Figure 3D), normal axons were enveloped in compact layers of myelin. However, in the CTB-SAP rat (Figure 3E), the axons appeared smaller and more irregularly shaped, and the myelin sheaths appeared thicker and more loosely woven.

FIGURE 3.

Ultrastructural changes in hypoglossal neurons and the hypoglossal nerve after intralingual CTB-SAP. Representative TEM images from the hypoglossal nucleus (A-C) and distal hypoglossal nerve (D,E) of a control (A,D) and CTB-SAP–treated rat (B,C,E). A, Normal motor neuron from a control rat is outlined in white. The white arrow indicates the nucleolus. B,C, Hypoglossal neurons in CTB-SAP–injected rats show progressive signs of degeneration including loss of the nucleolus (white arrow), decreased overall size, and increased nucleus:cytoplasm ratio. D, Nerve from the control rat consists of normal axons surrounded by compact myelin sheaths (white arrows). E, In the image from the CTB-SAP–treated rat, the axons appear smaller and are surrounded by thickened, irregular myelin sheaths, which are consistent with degeneration. Abbreviations: CTB-SAP, cholera toxin B conjugated to saporin; TEM, transmission electron microscopy

4 |. DISCUSSION

In this study we found evidence of microscopic, but not macroscopic, tongue atrophy on day 9 after intralingual injection with CTB-SAP. Specifically, the mean CSA of genioglossus myofibers was significantly decreased in CTB-SAP–treated rats. However, there was also a significant interaction between the effects of experimental group and location within the genioglossus, so additional studies will be needed to fully unravel the contribution of each. In addition, we used TEM to document ultrastructural evidence of degeneration in the hypoglossal neurons and in axons of the hypoglossal nerve, which is consistent with our previous report showing that hypoglossal motor neuron counts were decreased by ~60% on day 9 after intralingual CTB-SAP.23

4.1 |. Denervation atrophy of the tongue

Numerous investigations have been conducted to characterize limb muscle atrophy after denervation.34,40 However, detailed analysis of tongue atrophy after hypoglossal denervation is lacking. The clinical relevance of hypoglossal denervation extends beyond neurodegenerative/neurologic diseases to include neoplasia,41 radiation therapy,42 surgical trauma,43 and intentional surgical rerouting.44 A recent literature search revealed only four animal studies that examined tongue atrophy after hypoglossal denervation. In two of the studies the authors measured macroscopic morphometrics 3 and 6 months after unilateral transection and found decreases of ~15% (pigs)45 and ~55% (dogs),46 respectively. A third study investigated myofiber diameter after partial denervation and showed a 10% decrease in fiber size after 2 months (sheep).47 Tang and Suwa48 followed changes in rat tongues that occurred between 3 days and 66 weeks after unilateral transection, but they relied on qualitative descriptions rather than quantitative measurements. They did note that intrinsic muscle fibers “had partly disappeared” by 1 week after transection, which is similar to the time frame of our study.

Given the paucity of information available about the acute stages of tongue atrophy, we believe this and future studies using our intralingual CTB-SAP model will provide a valuable contribution to the literature. In addition, we have added some novel metrics to be used in macroscopic tongue analysis. The aforementioned studies used a variety of techniques, but all of them focused on the intrinsic muscles. Our tongue weights included four extrinsic tongue muscles, but were not separated from each other in order to keep the dorsal, lateral, and ventral aspects of the tongue intact. These included the genioglossus and geniohyoid, which are also innervated by the hypoglossal nerve and are important for tongue protrusion and its associated hyoid elevation, respectively.49 In addition, we included the mylohyoid and anterior belly of the digastric. These suprahyoid muscles are innervated by trigeminal rather than hypoglossal motor neurons, but their action (hyoid elevation and jaw opening) is tightly coordinated with tongue function.49 The measurements we obtained from the dorsal aspect of the tongue have previously been used by others,36,37,50 but our lateral and ventral aspect measurements are new. In addition, the lateral measurement of the extrinsic muscles may permit detection of changes in the volume of intermuscular fat and fascia secondary to neuromuscular pathology. Finally, some diseases with hypoglossal degeneration, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also impact the trigeminal nerve.51 In these cases, assessing the suprahyoid muscles may provide additional evidence of neuromuscular pathology contributing to dysphagia.

4.2 |. Further studies necessary to fully characterize changes in tongue myofiber size detected in intralingual CTB-SAP model

The genioglossus is complex and contains a horizontal and oblique compartment, where the oblique can be subdivided into posterior (fibers protrude the tongue), middle (fibers depress the tongue body), and anterior sections (fibers curl the tongue tip downward).38 Due to these varied functions, the fiber type and average size of myofibers are also different for each part of the muscle.52,53 We focused on the posterior section as these fibers are most directly responsible for protrusion.38 It has been reported that the average size of myofibers is largest in the posterior part and smallest in the anterior,53 but we found that to be true even within the posterior section. Perhaps this should have been expected. Although it is convenient to discuss the oblique fibers as three different categories, it seems more likely that they exist on a continuum, with gradual transitions in fiber size, type, and function.

In conclusion, we found that intralingual CTB-SAP causes detectable tongue atrophy within 9 days of injection, but only at the microscopic level. Although we have not yet documented an actual loss of tongue strength, the decrease in CSA of genioglossus myofibers and previously reported deficits in lick rate23 suggest it is likely present. We also found evidence of degeneration in both the hypoglossal neurons and nerve fibers. Together, these data are consistent with our previous evidence demonstrating neurodegeneration and dysphagia after intralingual CTB-SAP.23 This provides further support for our hypothesis that intralingual CTB-SAP will be a useful model for studying dysphagia and testing potential therapies for patients with compromised tongue function.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank DeAna Grant of the University of Missouri’s Electron Microscopy Core for her expertise in processing and obtaining the TEM images. We also thank Dr Henok Woldu for developing the statistical model to analyze the tongue fiber data.

Funding information

Mizzou Alumni Association, Grant/Award Number: Richard Wallace Faculty Incentive grant; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Grant/Award Number: HL119606 and HL153612; University of Missouri, Grant/Award Numbers: Excellence in Electron Microscopy grant, Phi Zeta Research grant; University of Missouri College of Veterinary Medicine Committee on Research; University of Missouri Research Board

Abbreviations:

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- CSA

cross-sectional area

- CTB

cholera toxin B

- CTB-SAP

cholera toxin B conjugated to saporin

- NDS

normal donkey serum

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- SAP

saporin

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

ETHICAL PUBLICATION STATEMENT

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bruijn LI, Miller TM, Cleveland DW. Unraveling the mechanisms involved in motor neuron degeneration in ALS. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:723–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonzalez de Aguilar JL, Echaniz-Laguna A, Fergani A, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: all roads lead to Rome. J Neurochem. 2007;101:1153–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ravits J, Appel S, Baloh RH, et al. Deciphering amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: what phenotype, neuropathology and genetics are telling us about pathogenesis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2013;14(Suppl 1):5–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner MR, Hardiman O, Benatar M, et al. Controversies and priorities in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:310–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, Munsat TL, World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Motor Neuron Diseases. El Escorial revisited: revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2000;1: 293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell JD, Borasio GD. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet. 2007; 369:2031–2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waito AA, Valenzano TJ, Peladeau-Pigeon M, Steele CM. Trends in research literature describing dysphagia in motor neuron diseases (MND): a scoping review. Dysphagia. 2017;32:734–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.da Costa FA, Mourao LF. Dysarthria and dysphagia in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with spinal onset: a study of quality of life related to swallowing. Neurorehabilitation. 2015;36:127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paris G, Martinaud O, Petit A, et al. Oropharyngeal dysphagia in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis alters quality of life. J Oral Rehabil. 2013; 40:199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuhnlein P, Gdynia HJ, Sperfeld AD, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of bulbar symptoms in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2008;4:366–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hadjikoutis S, Wiles CM. Respiratory complications related to bulbar dysfunction in motor neuron disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001;103: 207–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strand EA, Miller RM, Yorkston KM, Hillel AD. Management of oral-pharyngeal dysphagia symptoms in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Dysphagia. 1996;11:129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurian KM, Forbes RB, Colville S, Swingler RJ. Cause of death and clinical grading criteria in a cohort of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis cases undergoing autopsy from the Scottish Motor Neurone Disease Register. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:84–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corcia P, Pradat PF, Salachas F, et al. Causes of death in a postmortem series of ALS patients. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2008;9: 59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plowman EK. Is there a role for exercise in the management of bulbar dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis? J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2015;58:1151–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plowman EK, Tabor-Gray L, Rosado KM, et al. Impact of expiratory strength training in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: results of a randomized, sham-controlled trial. Muscle Nerve. 2019;59:40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Plowman EK, Watts SA, Tabor L, et al. Impact of expiratory strength training in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 2016;54: 48–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robison R, Tabor-Gray LC, Wymer JP, Plowman EK. Combined respiratory training in an individual with C9orf72 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018;5:1134–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller RG, Jackson CE, Kasarskis EJ, et al. Practice parameter update: the care of the patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: drug, nutritional, and respiratory therapies (an evidence-based review): report of the quality standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2009;73:1218–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nichols NL, Gowing G, Satriotomo I, et al. Intermittent hypoxia and stem cell implants preserve breathing capacity in a rodent model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187: 535–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nichols NL, Johnson RA, Satriotomo I, Mitchell GS. Neither serotonin nor adenosine-dependent mechanisms preserve ventilatory capacity in ALS rats. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2014;197:19–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nichols NL, Craig TA, Tanner MA. Phrenic long-term facilitation following intrapleural CTB-SAP-induced respiratory motor neuron death. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2018;256:43–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lind LA, Murphy ER, Lever TE, Nichols NL. Hypoglossal motor neuron death via Intralingual CTB-saporin (CTB-SAP) injections mimic aspects of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) related to dysphagia. Neuroscience. 2018;390:303–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee KZ, Qiu K, Sandhu MS, et al. Hypoglossal neuropathology and respiratory activity in Pompe mice. Front Physiol. 2011;2:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El Mallah MK, Falk DJ, Lane MA, et al. Retrograde gene delivery to hypoglossal motoneurons using adeno-associated virus serotype 9. Hum Gene Ther Methods. 2012;23:148–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aldes LD. Subcompartmental organization of the ventral (protrusor) compartment in the hypoglossal nucleus of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1995;353:89–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lujan HL, Palani G, Peduzzi JD, DiCarlo SE. Targeted ablation of mesenteric projecting sympathetic neurons reduces the hemodynamic response to pain in conscious, spinal cord-transected rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R1358–R1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Llewellyn-Smith IJ, Martin CL, Arnolda LF, Minson JB. Retrogradely transported CTB-saporin kills sympathetic preganglionic neurons. NeuroReport. 1999;10:307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Llewellyn-Smith IJ, Martin CL, Arnolda LF, Minson JB. Tracer-toxins: cholera toxin B-saporin as a model. J Neurosci Methods. 2000;103: 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nichols NL, Vinit S, Bauernschmidt L, Mitchell GS. Respiratory function after selective respiratory motor neuron death from intrapleural CTB–saporin injections. Exp Neurol. 2015;267:18–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lever TE, Gorsek A, Cox KT, et al. An animal model of oral dysphagia in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Dysphagia. 2009;24: 180–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lever TE, Simon E, Cox KT, et al. A mouse model of pharyngeal dysphagia in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Dysphagia. 2010;25:112–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lever TE, Braun SM, Brooks RT, et al. Adapting human videofluoro-scopic swallow study methods to detect and characterize dysphagia in murine disease models. J Vis Exp. 2015;97:52319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carlson BM. The biology of long-term denervated skeletal muscle. Eur J Transl Myol. 2014;24:3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9: 676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reiner DJ, Jan TA, Boughter JD, et al. Genetic analysis of tongue size and taste papillae number and size in recombinant inbred strains of mice. Chem Senses. 2008;33:693–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salas M, Rubio L, Torrero C, Carreon M, Regalado M. Effects of perinatal undernutrition on the circumvallate papilla of developing Wistar rats. Acta Histochem. 2016;118:581–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanders I, Mu L. A three-dimensional atlas of human tongue muscles. Anat Rec (Hoboken). 2013;296:1102–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kletzien H, Hare AJ, Leverson G, Connor NP. Age-related effect of cell death on fiber morphology and number in tongue muscle. Muscle Nerve. 2018;57:E29–E37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Midrio M The denervated muscle: facts and hypotheses. A historical review. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2006;98:1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Russo CP, Smoker WR, Weissman JL. MR appearance of trigeminal and hypoglossal motor denervation. Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:1375–1383. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.King AD, Ahuja A, Leung SF, Chan YL, Lam WW, Metreweli C. MR features of the denervated tongue in radiation induced neuropathy. Br J Radiol. 1999;72:349–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murakami R, Baba Y, Nishimura R, et al. CT and MR findings of denervated tongue after radical neck dissection. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:747–750. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Samii M, Alimohamadi M, Khouzani RK, Rashid MR, Gerganov V. Comparison of direct side-to-end and end-to-end hypoglossal-facial anastomosis for facial nerve repair. World Neurosurg. 2015;84: 368–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Licup AT, Arkia H, Mabel A, Cohen-Kerem R, Forte V. Partial neurolysis of the hypoglossal nerve for selective lingual atrophy in a porcine model. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2006;115:857–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chambers KJ, Anthony DC, Randolph GW, Hartnick CJ, Stopa EG, Song PC. Atrophy of the tongue following complete versus partial hypoglossal nerve transection in a canine model. Laryngoscope. 2016; 126:2689–2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Plowman EK, Bijangi-Vishehsaraei K, Halum S, et al. Autologous myoblasts attenuate atrophy and improve tongue force in a denervated tongue model: a pilot study. Laryngoscope. 2014;124: E20–E26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tang CS, Suwa F. Changes in histological structure and microvasculature of the rat tongue after transection of the hypoglossal nerve. Okajimas Folia Anat Jpn. 1994;71:183–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McLoon LK, Andrade FH. Craniofacial Muscles: A New Framework for Understanding the Effector Side of Craniofacial Muscle Control. New York: Springer; 2013:viii. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Osman KL, Kohlberg S, Mok A, et al. Optimizing the translational value of mouse models of ALS for dysphagia therapeutic discovery. Dysphagia. 2020;35:343–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.DePaul R, Abbs JH, Caligiuri M, Gracco VL, Brooks BR. Hypoglossal, trigeminal, and facial motoneuron involvement in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 1988;38:281–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Volz LM, Mann LB, Russell JA, Jackson MA, Leverson GE, Connor NP. Biochemistry of anterior, medial, and posterior genioglossus muscle in the rat. Dysphagia. 2007;22:210–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saigusa H, Niimi S, Yamashita K, Gotoh T, Kumada M. Morphological and histochemical studies of the genioglossus muscle. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110:779–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.