Abstract

Objectives:

To compare changes in upper airway volume after maxillary expansion with bone- and tooth-borne appliances in adolescents and to evaluate the dentoskeletal effects of each expansion modality.

Materials and Methods:

This retrospective study included 36 adolescents who had bilateral maxillary crossbite and received bone-borne maxillary expansion (average age: 14.7 years) or tooth-borne maxillary expansion (average age: 14.4 years). Subjects had two cone beam computed tomography images acquired, one before expansion (T1) and a second after a 3-month retention period (T2). Images were oriented, and three-dimensional airway volume and dentoskeletal expansion were measured. Analysis of variance was used to test for differences between the two expansion methods for pretreatment, posttreatment, and prepost changes. Paired t-tests were used to test for significance of prepost changes within each method.

Results:

Both groups showed significant increase only in nasal cavity and nasopharynx volume (P < .05), but not oropharynx and maxillary sinus volumes. Intermolar and maxillary width increased significantly in both groups (P < .05); however, the buccal inclination of maxillary molars increased significantly only in the tooth-borne group (P < .05). There was no significant difference between tooth- and bone-borne expansion groups, except for the significantly larger increase in buccal inclination of the maxillary right first molar after tooth-borne expansion.

Conclusions:

In adolescents, both tooth- and bone-borne RME resulted in an increase in nasal cavity and nasopharynx volume, as well as expansion in maxillary intermolar and skeletal widths. However, only tooth-borne expanders caused significant buccal tipping of maxillary molars.

Keywords: Airway, Tooth-borne expansion, Bone-borne expansion

INTRODUCTION

Rapid maxillary expansion (RME) is routinely used in the orthodontic treatment of patients with transverse maxillary deficiency, dental crowding, and/or a mandibular functional shift. A common form of RME uses tooth-borne expanders with bands on molars and sometimes first premolars. Transverse expansion is achieved through skeletal expansion, ie, opening of midpalatal sutures with separation of maxillary halves and dentoalveolar expansion, which can include buccal tipping of teeth and alveolar bending.1 Tooth-borne expansion appliances produce varying amounts of dental and skeletal expansion. Skeletal expansion is about half or less of the total amount of resulting expansion in adolescent patients.1,2 As the midpalatal sutures undergo maturation and fusion from childhood to late adolescence and adulthood, the amount of skeletal expansion with conventional RME and its long-term stability decreases.3,4 Failure of RME to open the suture is associated with unwanted dentoalveolar side effects, such as pain, severe buccal tipping and extrusion of teeth, gingival recession, buccal cortex fenestration, and root resorption.5

Bone-borne RME (or miniscrew assisted RME) was recently proposed to minimize the unwanted dentoalveolar effects of RME and produce greater skeletal changes.6,7 In the bone-borne RME, palatal miniscrews are used as anchorage to transfer the expansion force directly to the skeletal structures.8 In two groups of late adolescent patients, Lin et al.7 reported significantly greater skeletal expansion, less buccal tipping of first molars, and less buccal dehiscence following the bone-borne RME than expansion with tooth-borne RME using a hyrax appliance.

Studies showed that heavy forces generated by expanders could impact the craniofacial structures beyond the midpalatal suture.9,10 Following RME, high levels of stress were observed in surrounding structures, such as the zygomaticomaxillary, zygomaticotemporal, and frontomaxillary sutures, frontal process of the maxilla, and external wall of the orbits.9 Widening of nasal apertures, separation of the nasal floor, and displacement of the lateral nasal walls were also reported to be associated with sensation of pressure in the maxillary, nasal, or orbital areas.10–13 A study by Garrett et al.14 showed that the average increase in nasal width following tooth-borne expansion with a hyrax was only 37% of the total appliance expansion.

Due to the potential differences between the bone- and tooth-borne expanders, greater changes in airway volume may be anticipated with utilization of miniscrews.15,16 The aim of the current study was to measure and compare the changes in airway volume of the nasal cavity, maxillary sinuses, and pharynx after use of bone- or tooth-borne expansion appliances. The secondary purpose was to evaluate the dentoskeletal effects of each expansion modality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Indiana University–Purdue University (IRB protocol number: 1708606623). This retrospective study included adolescent subjects who completed their orthodontic treatment at the same orthodontic clinic (University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada). Patients were randomly assigned to either one of the two expanders (bone-anchored or tooth-anchored). The inclusion criteria for the study included: individuals between 11 and 15 years of age with no history of orthodontic treatment, temporomandibular joint disorder, adenoidectomy or tonsillectomy, periodontal diseases, systemic diseases, craniofacial anomalies, and no active caries. All subjects had a bilateral maxillary crossbite and received bone-borne RME or tooth-borne RME as part of their comprehensive orthodontic treatment. The randomization of assigning the treatment group resulted in the two groups having no significant differences in their initial conditions.

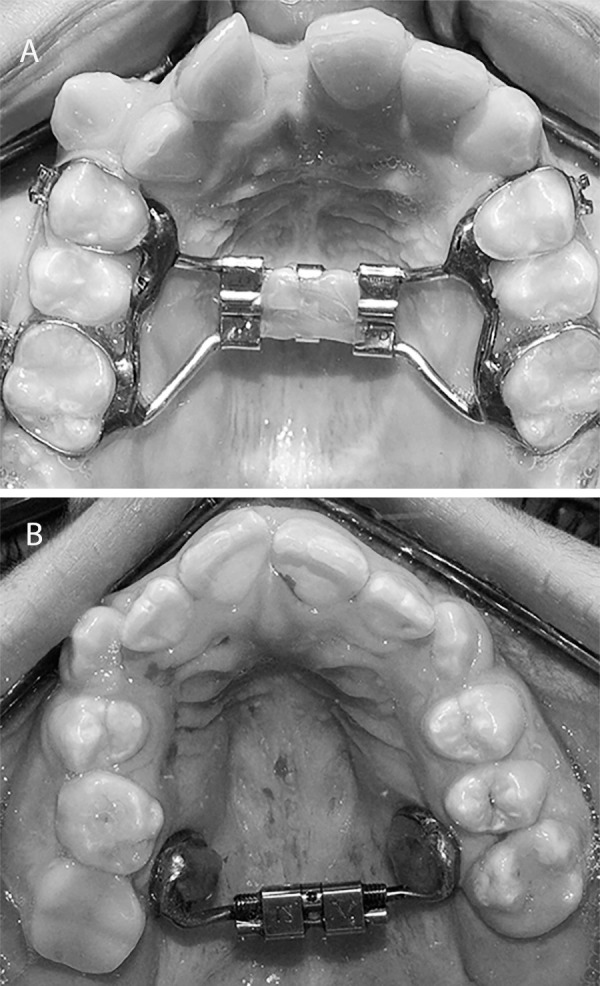

The tooth-borne expander design included a hyrax appliance with bands on the permanent first molars and first premolars (Figure 1A). If permanent first premolars were not erupted, bands were placed on deciduous first molars. In the bone-borne RME group, two miniscrews (length: 12 mm; diameter: 1.5 mm; Straumann GBR System, Andover, MA) were placed in the palate between the permanent first molars and second premolar and were connected with a jackscrew (Palex II Extra-Mini Expander, Summit Orthodontic Services, Munroe Falls, OH; Figure 1B). The activation rate per jackscrew turn (0.25 mm/turn) was the same in the tooth-borne expander and bone-borne expander groups. Patients in both groups were asked to turn the expander screw two turns per day for a total of 0.5 mm/d. The expansion continued until the mesiopalatal cusps of the maxillary first permanent molars were in contact with the buccal cusps of mandibular first permanent molars.

Figure 1.

Maxillary expanders used in the study. (A) Tooth-borne rapid maxillary expander. (B) Bone-borne rapid maxillary expander.

All subjects had two low-dose cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) scans acquired, one before the expansion (T1) and one after a 3-month retention period (T2). All patients were scanned with the iCAT CBCT Unit (Imaging Sciences International, Hartfield, PA) and the same setting protocol: 0.3 voxel, 8.9 seconds, large field of view at 120 kV and 20 mA.

Initially, 40 subjects (20 subjects in the bone-borne and 20 subjects in the tooth-borne expansion groups) were included in the study; however, three subjects (one in the bone-borne and two in the tooth-borne group) were excluded due to motion artifact in the CBCT images. In addition, one subject was excluded from the bone-borne group since the subject showed excessive opacification of the maxillary sinuses and nasal cavity in the T2 CBCT image. As a result, 18 subjects (10 females: eight males; average age: 14.4 ± 1.3 years) who received tooth-borne RME, and 18 subjects (12 females: six males; average age: 14.7 ± 1.4 years) who received bone-borne RME were included in the final analyses.

Dolphin Imaging Software, version 11.0 (Dolphin Imaging, Chatsworth, CA), was used for image analyses. Analysis was performed using the same computer monitor and light settings (24-in. monitor; Dell, Round Rock, TX; 1920 × 1200 pixels). The investigators (G.K. and A.G.) traced and analyzed 10 randomly selected study images independently to determine the inter-rater reliability. In addition, the primary investigator (G.K.) repeated the same measures after 2 weeks to determine the intra-examiner reliability. A minimum intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.8 was necessary before the analyses of the remaining CBCT images were permitted.

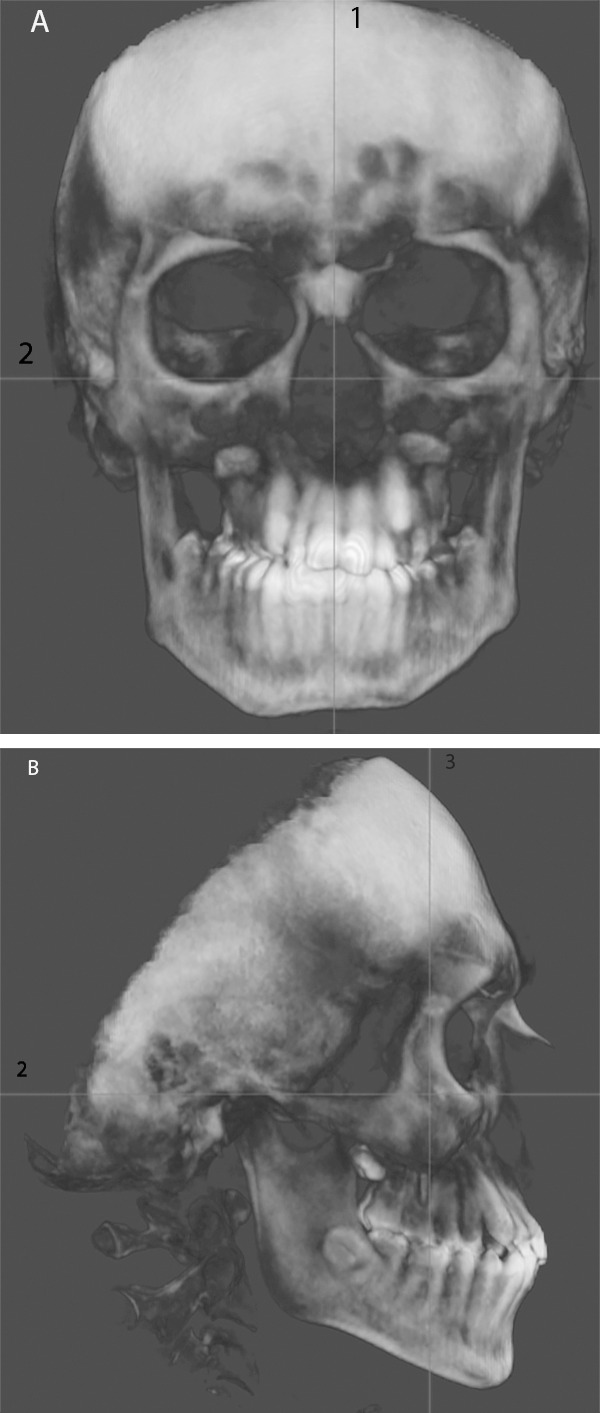

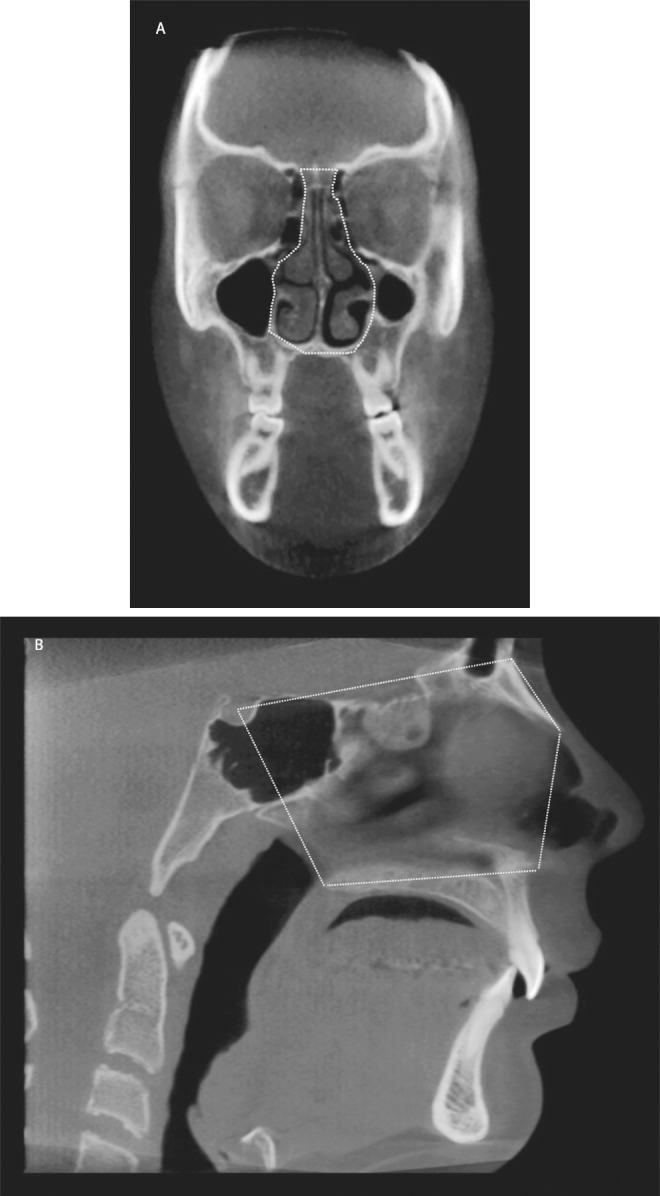

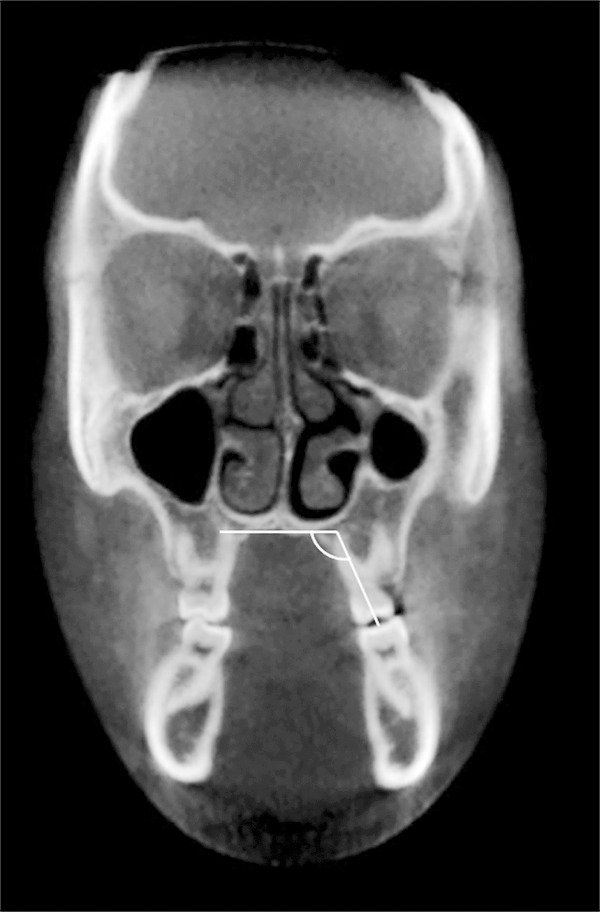

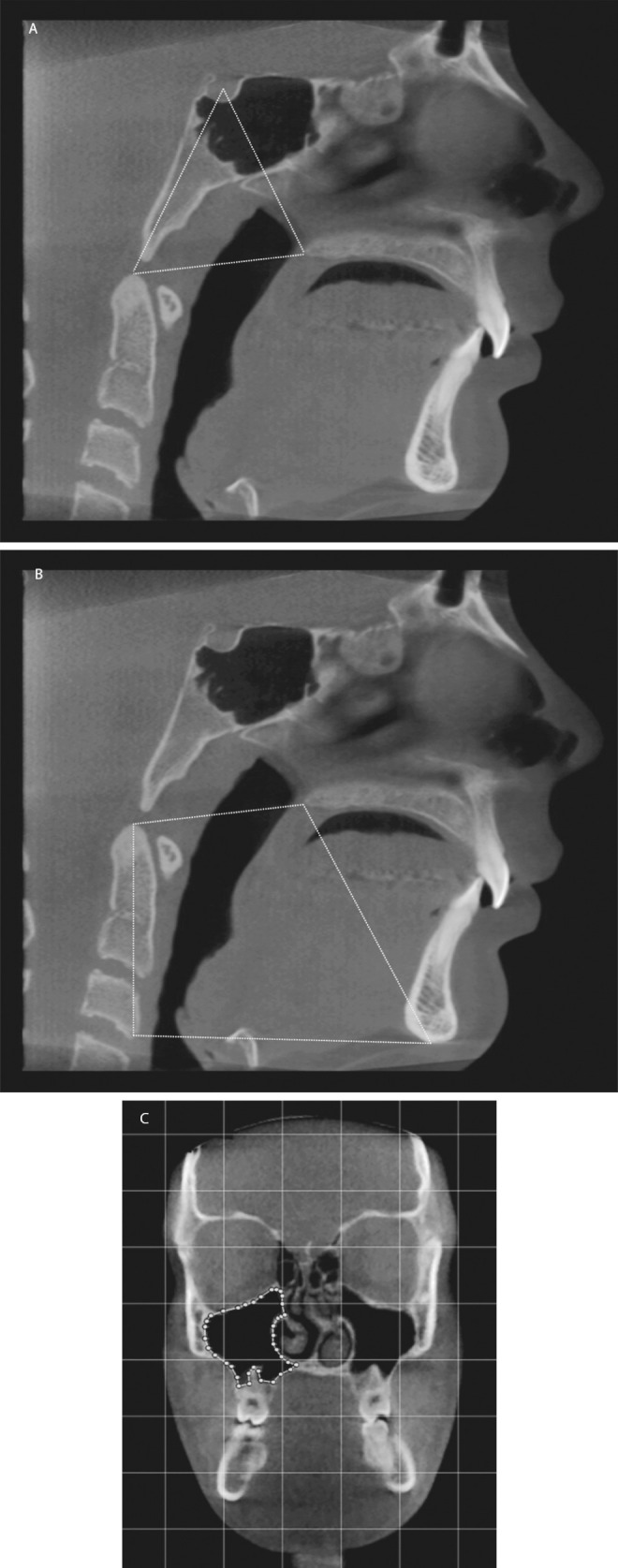

Prior to the identification of landmarks, all CBCT images were oriented based on the skeletal midline, Frankfort horizontal plane, and the line passing through the deepest point of the lateral surface of the zygomatic bones (Figure 2). Three-dimensional (3D) airway volumetric and soft-tissue landmarks were previously established by Smith and colleagues.17 A detailed description of these landmarks and volumetric and dentoskeletal expansion measurements are shown in Table 1 and Figures 3–6.

Figure 2.

Image orientation: images were oriented based on (1) the skeletal midline, (2) Frankfort horizontal plane, and (3) the line passing through the furcation of maxillary right first molar. (A) Frontal view. (B) Sagittal view.

Table 1.

Definition of Airway and Dentoskeletal Parameters

| Parameter |

Definition |

| Nasal cavity, mm3 | The airway space bound by lines connecting the anterior nasal spine (ANS) to the tip of the nasal bone, the tip of the nasal bone to nasion (N), N to sella (S), and S to posterior nasal spine (PNS, Figure 3) |

| Nasopharynx, mm3 | The airway space bound by lines connecting PNS to S, S to the tip of odontoid process, the tip of odontoid process to PNS (Figure 4A) |

| Oropharynx, mm3 | The airway space bound by lines connecting PNS to the tip of odontoid process, the tip of odontoid process to the most anterior-inferior point of cervical vertebra 3 (CV3), the most anterior–inferior point of CV3 to menton (Figure 4B) |

| Maxillary sinus, mm3 | The maxillary sinus on the coronal section passing through the maxillary right first molar furcation (Figure 4C) |

| External maxillary width, mm | The line connecting the depth of concavity of the lateral walls of maxillary sinuses on the coronal section passing through the maxillary right first molar furcation (Figure 5A) |

| Palatal width, mm | The line connecting the junctions of the hard palate and lingual alveolar bone on the coronal section passing through the maxillary right first molar furcation (Figure 5A) |

| Intermolar width at the first molar central fossa level, mm | The line connecting the central fossae of the right and left maxillary first molars on the coronal section passing through the maxillary right first molar furcation (Figure 5B) |

| Intermolar width at the first molar palatal apex level, mm | The line connecting the apices of the right and left maxillary first molars on the coronal section passing through the maxillary right first molar furcation (Figure 5B) |

| Buccal inclination of maxillary first molar, degree | The angle formed between the line connecting the palatal apex and central fossa of maxillary first molar and the line tangent to the lower border of hard palate (Figure 6) |

Figure 3.

Boundaries of nasal cavity. (A) Frontal view. (B) Sagittal view.

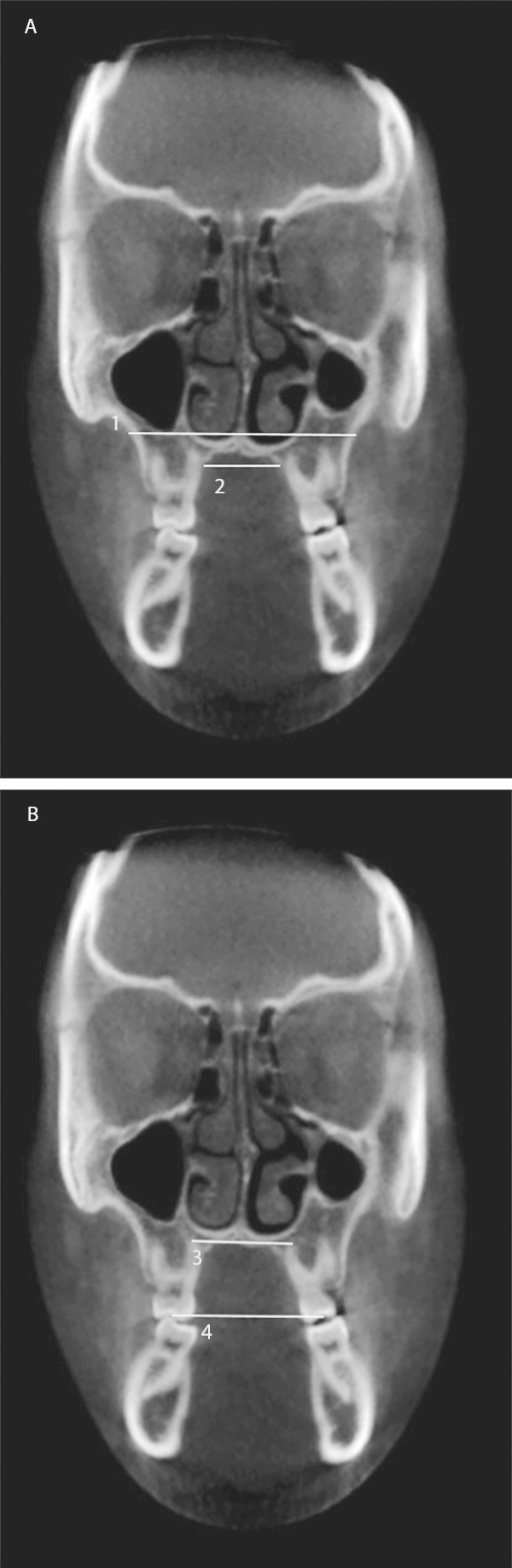

Figure 6.

Buccal inclination of the maxillary left first molar: The angle formed between the line connecting the palatal apex and central fossa of the maxillary first molar and the line tangent to the lower border of the hard palate.

Figure 4.

Boundaries of airway spaces. (A) Nasopharynx. (B) Oropharynx. (C) Right maxillary sinus.

Figure 5.

(A) Skeletal expansion measured at the level of maxillary first molars: (1) External maxillary width, (2) Palatal width. (B) Intermolar width measured at the level of: (3) Palatal root apices, (4) Central fossae of maxillary first molars.

Statistical Analysis

Based on a previous study,17 with a sample size of 20 subjects per treatment group and a significance level of 0.05, this analysis had 80% power to ascertain a 3660 mm3 difference within each group for the prepost change in nasal cavity volume, a 5046 mm3 difference between groups, and a correlation coefficient of 0.58.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for differences between methods for pretreatment and posttreatment. Paired t-tests were also used to test for significant changes pre- and post- intervention within each method. Additionally, ANOVA was used to test for differences between methods for the changes. A 5% significance level was used for all the tests.

RESULTS

The intra-rater and inter-rater reliability for all the measurements was high, with intraclass correlation coefficients above 0.80.

Pre- and Post-expansion Comparison Within Each RME Group

In the tooth-borne expansion group, significant volume increases (P < .05) occurred in the nasal cavity (12.5%) and nasopharynx (21.8%). In the bone-borne expansion group, the nasal cavity and nasopharynx volume significantly increased (P < .05) by 16.1% and 20.0%, respectively. In addition, the external maxillary width, palatal width, as well as the maxillary intermolar width, measured at the central fossa and apex of first molars increased significantly in both expansion groups (P < .05). The buccal inclination of maxillary first molars increased significantly only in the tooth-borne expansion group (P < .05, Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Airway and Dentoskeletal Expansion Parameters Pre- and Post-Tooth-Borne RME

| Sample Size, N |

Pre-RME (T1), Mean (SD) |

Post-RME (T2), Mean (SD) |

Change (T2–T1), Mean (SD) |

Change (T2–T1), % |

P Value* |

|

| Nasal cavity volume, mm3 | 18 | 14860 (3109) | 16726 (3041) | 1866 (425) | 12.5 | .0004 |

| Nasopharynx volume, mm3 | 18 | 3760 (1630) | 4580 (1819) | 820 (275) | 21.8 | .0083 |

| Oropharynx volume, mm3 | 18 | 11746 (4269) | 12297 (3660) | 551 (620) | 0.5 | .3869 |

| Right maxillary sinus volume, mm3 | 17 | 13004 (3926) | 13739 (3759) | 734 (400) | 5.6 | .0845 |

| Left maxillary sinus volume, mm3 | 17 | 12369 (4039) | 13184 (3821) | 578 (297) | 4.7 | .0695 |

| Intermolar width at the first molar central fossa level, mm | 18 | 43.5 (3.3) | 48.0 (3.1) | 4.5 (0.4) | 10.3 | <.0001 |

| Intermolar width at the first molar palatal apex level, mm | 18 | 30.5 (4.5) | 33.4 (4.1) | 3.0 (0.5) | 9.8 | <.0001 |

| External maxillary width, mm | 18 | 63.3 (3.5) | 65.5 (3.5) | 2.2 (0.4) | 3.5 | <.0001 |

| Palatal width, mm | 18 | 22.9 (4.1) | 24.4 (3.4) | 1.5 (0.4) | 6.5 | .0011 |

| Maxillary right first molar buccal inclination** | 18 | 108.8 (4.3) | 111.6 (4.1) | 3.0 (0.7) | 2.8 | .0005 |

| Maxillary left first molar buccal inclination** | 18 | 110.3 (5.0) | 112.6 (5.0) | 2.3 (0.7) | 2.1 | .0039 |

Significant at P value < .05; ** Measurements for parameter are shown in degrees.

Table 3.

Airway and Dentoskeletal Expansion Parameters Pre- and Post-Bone-Borne RME

| Sample Size, N |

Pre-RME (T1), Mean (SD) |

Post-RME (T2), Mean (SD) |

Change (T2–T1), Mean (SD) |

Change (T2–T1), % |

P Value* |

|

| Nasal cavity volume, mm3 | 18 | 15241 (3959) | 17690 (3993) | 2449 (605) | 16.1 | .0008 |

| Nasopharynx volume, mm3 | 18 | 3530 (1616) | 4237 (1739) | 708 (159) | 20.0 | .0004 |

| Oropharynx volume, mm3 | 18 | 11045 (2186) | 11329 (2642) | 284 (386) | 2.6 | .4722 |

| Right maxillary sinus volume, mm3 | 18 | 13406 (4399) | 13695 (4090) | 289 (302) | 2.1 | .3517 |

| Left maxillary sinus volume, mm3 | 18 | 13539 (4449) | 14242 (4125) | 703 (377) | 5.2 | .0795 |

| Intermolar width at the first molar central fossa level, mm | 18 | 42.5 (2.7) | 45.6 (5) | 3.1 (1.2) | 7.3 | .0194 |

| Intermolar width at the first molar palatal apex level, mm | 18 | 29.1 (4.1) | 32.7 (6.4) | 4.0 (1.4) | 13.8 | .0116 |

| External maxillary width, mm | 18 | 63.0 (3.6) | 64.7 (3.3) | 1.7(0.4) | 2.7 | .0001 |

| Palatal width, mm | 18 | 21.7 (2.7) | 23.9 (3.2) | 2.2 (0.3) | 10.1 | <.0001 |

| Maxillary right first molar buccal inclination** | 18 | 110.4 (8.1) | 111.5 (6.5) | 0.4 (0.9) | 0.4 | .6378 |

| Maxillary left first molar buccal inclination** | 18 | 112.3 (5.8) | 113.9 (7.0) | 1.4 (0.7) | 1.2 | .0590 |

Significant at P value < .05; ** measurements for parameter are shown in degrees.

Pre- and Post-expansion Comparison Between RME Groups

Comparison of pretreatment, posttreatment and prepost changes between the tooth-borne and bone-borne expansion groups showed no significant difference (P > .05), except for a significantly larger increase in buccal inclination of maxillary right first molar after tooth-borne expansion (P < .05, Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of Changes in Airway and Dentoskeletal Parameters Between Tooth-Borne and Bone-Borne RME Groups

| T2–T1 |

P Value* |

||

| Tooth- borne |

Bone- borne |

||

| Nasal cavity volume, mm3 | 1866 | 2449 | .4419 |

| Nasopharynx volume, mm3 | 820 | 708 | .7414 |

| Oropharynx volume, mm3 | 551 | 284 | .6611 |

| Right maxillary sinus volume, mm3 | 734 | 289 | .4068 |

| Left maxillary sinus volume, mm3 | 578 | 703 | .7193 |

| Intermolar width at the first molar central fossa level, mm | 4.5 | 3.1 | .3241 |

| Intermolar width at the first molar palatal apex level, mm | 3.0 | 4.0 | .4618 |

| External maxillary width, mm | 2.2 | 1.7 | .3493 |

| Palatal width, mm | 1.5 | 2.2 | .0840 |

| Maxillary right first molar buccal inclination** | 3 | 0.4 | .0446 |

| Maxillary left first molar buccal inclination** | 2.3 | 1.4 | .3671 |

Significant at P value < .05; ** measurements for parameter are shown in degrees.

DISCUSSION

This retrospective analysis assessed the airway and dentoskeletal changes associated with both tooth- and bone-borne expansion using 3D CBCT analysis. In this study, there was no significant difference in airway volume and dentoskeletal variables between the tooth- and bone-borne groups prior to expansion, indicating the homogeneity of study subjects between the two groups.

Both tooth- and bone-borne expansion groups showed significant increases in intermolar width, palatal width, and external maxillary width. However, significant buccal tipping of molars was observed only in the tooth-borne expansion group. Lin et al.7 compared dentoalveolar and skeletal effects of a bone-borne expander (C-expander) to those of a tooth-borne expander in a group of adolescent patients. Similar to this study, they found more buccal tipping of maxillary molars in the tooth-borne group. However, they found higher skeletal expansion, measured at the maxillary suture, as well as maxillary width, measured at the nasal floor and palatal vault level. Given that subjects in the present study were younger than those in the Lin et al. study (14 years vs 17 years), it is reasonable to expect more comparable skeletal expansion in the tooth- and bone-borne expansion groups in the present study. A similar study by Lagravere et al.18 also found no significant difference in dental and skeletal expansion at the maxillary first molar between the adolescents who received tooth- and bone-borne expansion. The change in the buccal inclination of the right maxillary first molar was significantly higher after tooth-borne RME than bone-borne RME (3° vs 0.4°, respectively), but the difference in the buccal inclination of the left maxillary first molar was not significantly different between the two groups (2.3° vs 1.4°, respectively).

Both bone- and tooth-borne expansion groups showed significant increases in the nasal cavity and nasopharynx volumes, but no significant changes in oropharynx volume after expansion. Increases in nasal cavity and nasopharynx volumes after hyrax expansion in adolescents have been shown by previous studies that used 3D images,17,19–21 as well as two-dimensional measurements.22,23 Kim et al.24 evaluated airway volume changes after miniscrew-assisted rapid maxillary expansion in young adults using CBCT images. They demonstrated that the volume, as well as the anterior and middle cross-sectional area of nasal cavity, increased significantly after expansion and that the increase was retained at a 1-year follow-up visit. However, unlike the current study, observed changes in nasopharynx volume were not significant. The disagreement could be due to differences in the definition of nasopharynx between the two studies. The space, which was defined separately as the oropharynx in the present study, was included as part of the nasopharynx in Kim's study.24

Although the average increase in the volume of the nasal cavity was higher after bone-borne expansion than tooth-borne expansion (16.1% vs 12.5%), the difference was not statistically significant. This agreed with another finding of the current study: the skeletal expansion was not statistically different between the two groups. Previous studies have shown conflicting results in this regard. Kabalan et al.16 compared nasal airway changes in adolescents receiving miniscrew-based expanders vs tooth-borne expander using CBCT and acoustic rhinometry analyses. However, in their study, CBCT images were only used to assess linear measures in the nasal cavity and not for 3D assessment of airway volume changes. The results were highly variable and did not show any specific trends between the two experimental groups. In addition, Kabalan's study did not assess airway volume changes of the pharynx. In a randomized controlled trial, Bazargani et al.15 compared the effects of tooth-bone-borne (hybrid) and tooth-borne RMEs on nasal airflow and resistance using rhinomanometry examination after decongestion. They concluded that tooth-bone-borne RME resulted in higher nasal airflow and lower nasal resistance than tooth-borne RME in children. Differences in appliance design, airway measurement technique, and use of decongestant make the comparison between studies difficult.

Comparison of pretreatment, posttreatment and prepost changes between the tooth- and bone-borne expansion groups showed no significant differences except for a significantly larger increase in buccal inclination of the maxillary right first molar after tooth-borne expansion. This could be explained by the fact that tooth-borne expanders cause a range of dentoalveolar effects that is typically accompanied by tipping of the maxillary first molars and bending of the alveolar bone.

Children with maxillary constriction and high palatal vault were reported to be at higher risk of sleep-disordered breathing.25,26 Several studies showed significant improvement in symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing in children who received rapid maxillary expansion.27,28 A recent systematic review evaluated the effect of tooth-borne RME on treatment of patients with obstructive sleep apnea.29 The results of the meta-analysis showed that RME was an effective tool for normalization of apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) and improvement of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children. The present study demonstrated that both bone- and tooth-borne expanders appeared to be viable options for increasing the volume of the nasal cavity, as well as the nasopharynx. Nevertheless, caution should be exercised when considering these findings as sleep respiratory parameters were not evaluated in the present study. Future studies are warranted to compare the impact of the two expansion modalities on respiratory pattern and signs and symptoms of children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome.

CONCLUSIONS

Both tooth- and bone-borne rapid maxillary expanders significantly increased the volume of the nasal cavity and nasopharynx, as well as maxillary dental and skeletal width.

Only the tooth-borne expander group showed significant buccal tipping of maxillary molars.

No statistically significant difference was observed in nasal cavity or nasopharynx volume changes between the two expansion groups.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank George Eckert and Surya Sruthi Bhamidipalli for their invaluable support with the planning and execution of the study's statistics.

REFERENCES

- 1.Garrett BJ, Caruso JM, Rungcharassaeng K, Farrage JR, Kim JS, Taylor GD. Skeletal effects to the maxilla after rapid maxillary expansion assessed with cone-beam computed tomography. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;134:8.e1–8.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghoneima A, Abdel-Fattah E, Eraso F, Fardo D, Kula K, Hartsfield J. Skeletal and dental changes after rapid maxillary expansion: a computed tomography study. Aust Orthod J. 2010;26:141–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angelieri F, Cevidanes LH, Franchi L, Goncalves JR, Benavides E, McNamara JA., Jr Midpalatal suture maturation: classification method for individual assessment before rapid maxillary expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2013;144:759–769. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baccetti T, Franchi L, Cameron CG, McNamara JA., Jr Treatment timing for rapid maxillary expansion. Angle Orthod. 2001;71:343–350. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2001)071<0343:TTFRME>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suri L, Taneja P. Surgically assisted rapid palatal expansion: a literature review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;133:290–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee KJ, Park YC, Park JY, Hwang WS. Miniscrew-assisted nonsurgical palatal expansion before orthognathic surgery for a patient with severe mandibular prognathism. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:830–839. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin L, Ahn HW, Kim SJ, Moon SC, Kim SH, Nelson G. Tooth-borne vs bone-borne rapid maxillary expanders in late adolescence. Angle Orthod. 2015;85:253–262. doi: 10.2319/030514-156.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mosleh MI, Kaddah MA, Abd ElSayed FA, ElSayed HS. Comparison of transverse changes during maxillary expansion with 4-point bone-borne and tooth-borne maxillary expanders. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2015;148:599–607. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2015.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jafari A, Shetty KS, Kumar M. Study of stress distribution and displacement of various craniofacial structures following application of transverse orthopedic forces–a three-dimensional FEM study. Angle Orthod. 2003;73:12–20. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2003)073<0012:SOSDAD>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghoneima A, Abdel-Fattah E, Hartsfield J, El-Bedwehi A, Kamel A, Kula K. Effects of rapid maxillary expansion on the cranial and circummaxillary sutures. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;140:510–519. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2010.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oliveira De Felippe NL, Da Silveira AC, Viana G, Kusnoto B, Smith B, Evans CA. Relationship between rapid maxillary expansion and nasal cavity size and airway resistance: short- and long-term effects. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;134:370–382. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haas AJ. Palatal expansion: just the beginning of dentofacial orthopedics. Am J Orthod. 1970;57:219–255. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(70)90241-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung C-H, Font B. Skeletal and dental changes in the sagittal, vertical, and transverse dimensions after rapid palatal expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004;126:569–575. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garrett BJ, Caruso JM, Rungcharassaeng K, Farrage JR, Kim JS, Taylor GD. Skeletal effects to the maxilla after rapid maxillary expansion assessed with cone-beam computed tomography. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;134:8.e1–8.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bazargani F, Magnuson A, Ludwig B. Effects on nasal airflow and resistance using two different RME appliances: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Orthod. 2018;40:281–284. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjx081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kabalan O, Gordon J, Heo G, Lagravère MO. Nasal airway changes in bone-borne and tooth-borne rapid maxillary expansion treatments. Int Orthod. 2015;13:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ortho.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith T, Ghoneima A, Stewart K, et al. Three-dimensional computed tomography analysis of airway volume changes after rapid maxillary expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2012;141:618–626. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lagravere MO, Carey J, Heo G, Toogood RW, Major PW. Transverse, vertical, and anteroposterior changes from bone-anchored maxillary expansion vs traditional rapid maxillary expansion: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:304.e301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.09.016. discussion 304–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haralambidis A, Ari-Demirkaya A, Acar A, Kucukkeles N, Ates M, Ozkaya S. Morphologic changes of the nasal cavity induced by rapid maxillary expansion: a study on 3-dimensional computed tomography models. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;136:815–821. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El H, Palomo JM. Three-dimensional evaluation of upper airway following rapid maxillary expansion: a CBCT study. Angle Orthod. 2014;84:265–273. doi: 10.2319/012313-71.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao Y, Nguyen M, Gohl E, Mah JK, Sameshima G, Enciso R. Oropharyngeal airway changes after rapid palatal expansion evaluated with cone-beam computed tomography. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:S71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basciftci FA, Mutlu N, Karaman AI, Malkoc S, Kucukkolbasi H. Does the timing and method of rapid maxillary expansion have an effect on the changes in nasal dimensions? Angle Orthod. 2002;72:118–123. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2002)072<0118:DTTAMO>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ceroni Compadretti G, Tasca I, Alessandri-Bonetti G, Peri S, D'Addario A. Acoustic rhinometric measurements in children undergoing rapid maxillary expansion. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim SY, Park YC, Lee KJ, et al. Assessment of changes in the nasal airway after nonsurgical miniscrew-assisted rapid maxillary expansion in young adults. Angle Orthod. 2018;88:435–441. doi: 10.2319/092917-656.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katyal V, Pamula Y, Daynes CN, et al. Craniofacial and upper airway morphology in pediatric sleep-disordered breathing and changes in quality of life with rapid maxillary expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2013;144:860–871. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Souki BQ, Pimenta GB, Souki MQ, Franco LP, Becker HM, Pinto JA. Prevalence of malocclusion among mouth breathing children: do expectations meet reality? Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:767–773. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Villa MP, Malagola C, Pagani J, et al. Rapid maxillary expansion in children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: 12-month follow-up. Sleep Med. 2007;8:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miano S, Rizzoli A, Evangelisti M, et al. NREM sleep instability changes following rapid maxillary expansion in children with obstructive apnea sleep syndrome. Sleep Med. 2009;10:471–478. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vale F, Albergaria M, Carrilho E, et al. Efficacy of rapid maxillary expansion in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2017;17:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]