Bacteriophages are the most diverse and abundant biological entities on the Earth and require host bacteria to replicate. Because of this obligate relationship, in addition to the challenging conditions of surrounding environments, phages must integrate information about extrinsic and intrinsic factors when infecting their hosts.

KEYWORDS: quorum sensing, bacteriophage, cell communication, cross talk, arbitrium, lysis-lysogeny, quorum quenching, phage decisions

ABSTRACT

Bacteriophages are the most diverse and abundant biological entities on the Earth and require host bacteria to replicate. Because of this obligate relationship, in addition to the challenging conditions of surrounding environments, phages must integrate information about extrinsic and intrinsic factors when infecting their hosts. This integration helps to determine whether the infection becomes lytic or lysogenic, which likely influences phage spread and long-term survival. Although a variety of environmental and physiological clues are known to modulate lysis-lysogeny decisions, the social interplay among phages and host populations has been overlooked until recently. A growing body of evidence indicates that cell-cell communication in bacteria and, as shown more recently, peptide-based communication among phage populations affect phage-host interactions by controlling phage lysis-lysogeny decisions and phage counterdefensive strategies in bacteria. Here, we explore and discuss the role of signal molecules, as well as quorum-sensing and -quenching factors, that mediate phage-host interactions. Our aim is to provide an overview of population-dependent mechanisms that influence phage replication and to elucidate how social communication may affect the dynamics and evolution of microbial communities, including their implications for phage therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Bacteriophages, or phages, are viruses that infect bacteria and hijack the host cellular machinery to replicate and produce viral particles as offspring. Phages are the most abundant and diverse biological entities on Earth, with an estimated 1031 viral particles (1), and are essential in the context of bacterial ecology and evolution. They affect all ecosystems in numerous ways, such as defining the composition and abundance of bacteria within microbial communities, regulating gene expression and host metabolism, conferring novel functions on the host, facilitating the transfer of genetic material, fostering the recycling of carbon and nutrients, and altering the biology of associated organisms (reviewed in references 2, to ,5). The impact of phages differs greatly depending on the specific infective strategies they employ (4).

Generally, phages are classified according to their life cycles as obligately lytic or temperate. Once lytic phages infect a bacterial cell, they enter into the productive cycle to produce viral particles and release them into the environment through host lysis. In contrast, temperate phages may enter either the lytic or the lysogenic cycle. During the lysogenic cycle, the phage genome integrates into the bacterial chromosome, becoming a “prophage.” There it replicates together with the genome of the bacterial cell until specific signals induce phage activation into the lytic cycle. In nature, variations in life cycles, including pseudolysogeny or chronic infection, have been observed, expanding the repertoire of phage infection strategies (for a review, see reference 6). Pseudolysogeny is a less common state that occurs in response to nutrient deprivation conditions, where the phage genome remains stalled as a nonintegrated and nonreplicated preprophage until nutrients are restored, subsequently triggering the lytic or lysogenic program (7). Chronic infection refers to productive infections in which virions are continuously released without cell lysis by either lytic or temperate phages (6).

Phage commitment is tightly regulated by molecular switches that drive the phage to be lytic or lysogenic. Most of our understanding of the lysis-lysogeny decision has been derived from the temperate phage λ in Escherichia coli, which is governed by regulatory genes expressed at early stages of infection (8). In the λ system, certain conditions, such as a low temperature, increased multiplicity of infection (MOI), reduced cell size, and cell starvation, promote lysogeny (9–12), while lytic development is preferred under permissive conditions that presumably favor a large burst of progeny (13). The molecular basis of this difference depends on the balance of the key factors CII and Q. CII promotes the expression of the CI repressor and an integrase (Int), and Q induces the expression of lysis and morphogenesis genes (14). High levels of CII promote lysogeny through CI, which directly represses lytic genes, while the Int protein integrates the phage DNA into the host genome. Conversely, low levels of CII increase the expression of cro, which is also repressed by CI, leading to a commitment to the lytic pathway and activating the transcription of lytic genes by Q antiterminator activity (15).

Although lysogeny is a highly stable cycle, prophages may reenter the lytic pathway either spontaneously at a low frequency (16) or after exposure to specific stimuli. In phage λ, an SOS response induced by DNA-damaging agents and particular host physiological states can cause a dramatic reduction in the CI concentration, favoring Cro accumulation and therefore driving a commitment to the lytic pathway (17). Other conditions reported to influence lysis-lysogeny decisions in phages include changes in salinity, aeration, nutrients, temperature, or pH (18–20); exposure to antibiotics (21), foreign DNA (22), UV rays (23), hydrogen peroxide (24), or pollutants (25); or bacterial cell density (26), phage concentration (27), or induction/inhibition by other prophages (28, 29).

Many bacteria use diverse quorum-sensing (QS) systems to coordinate their activities in a cell density-dependent manner. QS involves the production of diffusible or secreted signaling molecules that regulate gene expression to modulate several biological processes that contribute to bacterial adaptation, survival, and successful interactions with other organisms (30, 31). On the other hand, QS is negatively regulated by quorum quenching (QQ). QQ interferes with cell communication, which establishes complex social interactions among bacterial populations (32). Recently, it was discovered that phages can communicate with each other to sense viral population densities through arbitrium, a signaling system based on peptide autoinducers that is similar to bacterial QS systems (27). Increasing evidence has revealed that in addition to arbitrium, other QS-QQ networks are exploited by phages to determine their lytic or lysogenic fate (Table 1). In this review, we explore the role of QS-QQ and arbitrium communication systems in phage-host interactions to provide an overview of population-dependent mechanisms that control phage development. Moreover, we discuss how these communication systems may influence the dynamics and evolution of microbial communities, with potential implications for phage therapy.

TABLE 1.

Quorum-based systems modulating different aspects of phage-host interactions

| QS component(s) | Host | Phage(s) | Description and function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterium derived | |||

| Influencing phage production | |||

| AHLs | Soil and groundwater communities | Increase in prophage induction upon AHL supplementation (55) | |

| AHL mixtures | E. coli MG1655 | λ | Prophage induction in response to AHLs mediated by SdiA receptor and RcsA transcriptional factor in an unknown SOS-independent mechanism (55) |

| LasR, RhlR | P. aeruginosa PA14 | D3112, JBD20 | More-efficient phage replication in QS-proficient strains than in ΔlasR ΔrhlR double mutants (131) |

| AI-2 | E. faecalis V583ΔABC | pp1, pp5, pp7 | Promotion of prophage induction by high AI-2 concentrations (100 μM) (60) |

| PQS | P. putida KT2440 | PP1536–PP1584 | Induction of prophage PP1532–PP1584 in the presence of PQS (61) |

| AI-2 | E. coli ATCC 15144 | T1 | Triggering of prophage induction via phage-encoded transcription factor Pir by an unknown mechanism (59) |

| VanO | V. anguillarum 90-11-287 | ϕH20-like prophage p41 | Repression of prophage induction in the ΔvanO mutant, which mimics a high-cell-density QS mode, and in the wild-type strain upon the addition of cell-free conditioned supernatants obtained from high-cell-density cultures (62) |

| PqsD | P. aeruginosa PAO1 | LUZ19 | Required for efficient infection by LUZ19; supplementation with HHQ restored normal LUZ19 infection in pqsD mutants (65) |

| AHLsa | Soil communities | Increase in prophage induction upon AHL supplementation (56) | |

| 3-O-C12-HSL | A. baumannii | Ab105-1ϕ, Ab105-2ϕ | Increase in prophage induction upon AHL supplementation (141) |

| Antiphage mechanisms | |||

| C4-HSL | Serratia sp. strain ATCC 39006 | Activation of CRISPR-Cas in response to AHLs (83) | |

| AHL mixture | P. aeruginosa PA14 | Positive regulation of cas3 gene and increased spacer acquisition upon AHL supplementation (78, 89) | |

| AHL mixture | E. coli K-12 | λ, χ | Reduction in the number of receptors used by phages on the cell surface, causing a reduction in phage adsorption (84) |

| AHL mixture | V. anguillarum PF430-3 | KVP40 | Reduction in the number of KVP40 particles upon supplementation of culture with synthetic AHLs; downregulation of OmpK receptor by QS (98) |

| CAI-1 | V. cholerae | JSF35 | Reduction in phage production in response to CAI-1 by downregulation of LPS O-antigen receptor and upregulation of hemagglutinin protease HAP (85) |

| Conditioned supernatantb | E. coli K38 | P1 | Induction of mazEF-mediated cell death upon P1 prophage activation or upon addition of virulent P1 particles to E. coli cultures (100) |

| NDc | P. aeruginosa PAK-AR2, PAO1 | K5, C11 | Decrease in infection of stationary-phase cells by phages K5 and C11; increase in productive infection of stationary-phase cells upon supplementation with the QS inhibitor penicillic acid (63) |

| Phage derived | |||

| LuxRϕARM81ld | Aeromonas sp. strain ARM81 | ϕARM81ld | Unknown function; identified in metagenome databases; recombinant LuxRϕARM81ld binds to C4-HSL (72) |

| LuxRApop | Aeromonas popoffii | Apop | Unknown function; identified in metagenome databases; recombinant LuxRApop binds to C4-, C6-, and C8-HSL (72) |

| LuxR (Orf43) | C. tyrobutyricum | ϕCTP1 | Predicted protein harboring LuxR domain (IPR016032, signal transduction response regulator, C-terminal effector) (71) |

| gp33 | Iodobacter spp. | ϕPLPE | Identification of acylhydrolase (74) |

| Qst | P. aeruginosa PAO1 | LUZ19 | Interacts with PqsD, regulating PQS biosynthesis in the host (65) |

| Aqs1 | Pseudomonas | DMS3 | Anti-quorum-sensing protein that inhibits LasR (64) |

| VqmA | Vibrio spp. | VP882 | Upon binding of DPO, phage-encoded VqmA activates transcription of phage-encoded qtip to activate the lytic pathway (26) |

| agrB, agrC, agrD | C. difficile | phiCDHM1 | Agr homologs identified in phage genome; this system lacks the effector AgrA homolog (73) |

| agrB, agrC, agrD | Paenibacillus | Davies, Emery, Abouo | Agr homologs identified in phage genome; this system lacks the effector AgrA homolog (73) |

| LytTR proteins | Pseudomonas spp. | Lu11, vB_PaeS_PMG1, D3 | Phages harbor genes with LytTR protein domain suggesting homology to AgrA, indicating a putative ability to listen to the Agr system (73) |

| Arbitrium peptides | |||

| SAIRGA | B. subtilis strain 168 | phi3T | Promotion of lysogeny depending on phage concentration perceived by arbitrium peptide (27) |

| GMPRGA | B. subtilis BEST7003 | SPbeta phage | Promotion of lysogeny depending on phage concentration perceived by arbitrium peptide (27) |

| EIKPGG | Bacillus cereus RSVF1 | Wbeta | Prophage induction upon 1 μM peptide supplementation (76) |

| MMSEPGGGGW | Bacillus thuringiensis serovar galleriae BGSC:4G5 | Waukesha92-like | Prophage induction upon 1 μM peptide supplementation (76) |

Prophage was induced using each AHL separately: C4-HSL, C6-HSL, 3-O-C6-HSL, C7-HSL, C8-HSL, 3-O-C12-HSL, C14-HSL, 3-O-C14-HSL.

Later identified as EDF.

ND, not determined.

CELL COMMUNICATION IN BACTERIA: AN OVERVIEW

Over the past century, studies have demonstrated that bacteria may communicate with each other to modulate a wide range of social behaviors. They can produce, secrete, detect, and respond to a variety of signaling molecules, also called autoinducers, in the QS system in order to coordinate numerous bacterial processes once a critical cell density is reached (31). QS was discovered in Vibrio fischeri, a marine bacterium that produces N-(3-oxohexanoyl)-l-homoserine lactone (3-O-C6-HSL) for the induction of genes involved in bioluminescence, an important trait for establishing a mutualistic symbiosis with the squid Euprymna scolopes (33). Later, diverse signaling molecules for QS were described, most of which are associated with biological processes in the pathogenic and symbiotic relationships of bacteria with plants and animals (reviewed in references 34 to 36).

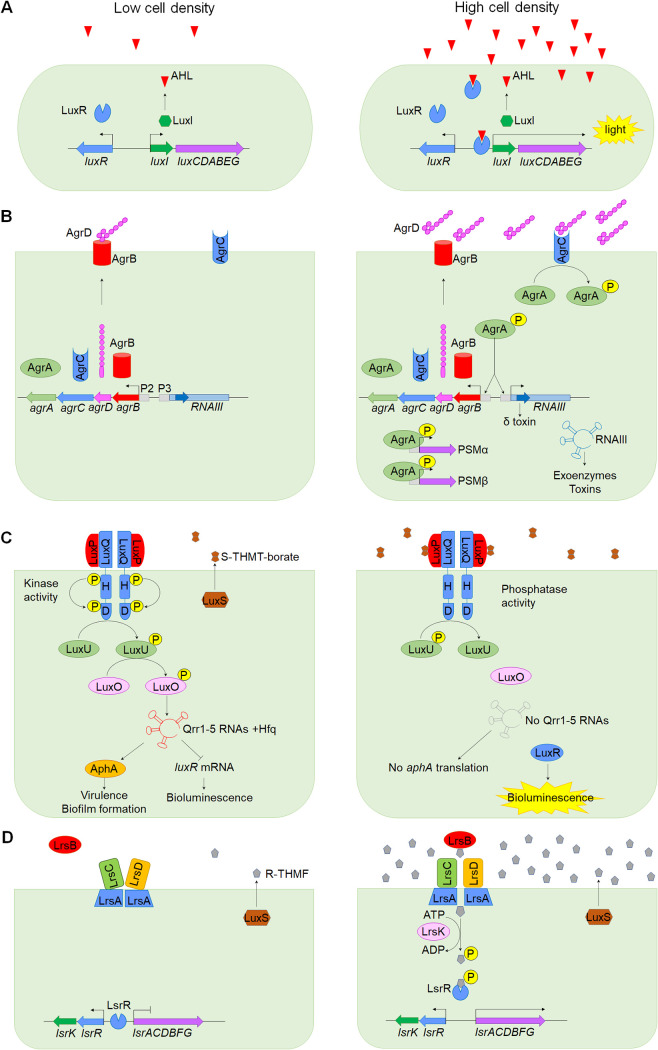

QS signals consist mainly of N-acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs) in Gram-negative bacteria (37), autoinducing oligopeptides (AIPs) in Gram-positive bacteria (38), and furanosyl borate diesters (autoinducer 2 [AI-2]), which are found in both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria and facilitate interspecies communication (39) (Fig. 1). Other classes of signaling molecules, such as cyclic dipeptides, quinolones (Pseudomonas quinolone signal [PQS]), small diffusible signal factors (DSF), cholera autoinducer 1 (CAI-1), 3-hydroxy palmitic acid methyl ester (3OH-PAME), 2-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-thiazole-4-carbaldehyde (IQS), dialkylresorcinols (DAR), photopyrones (PPY), γ-butyrolactone, 3,5-dimethylpyrazin-2-ol (DPO), and AI-3 (pyrazinones), have been described in bacterium-specific QS systems (40–42).

FIG 1.

QS signaling in bacteria. (A) AHL regulation of bioluminescence in V. fischeri. At a low cell density, luxI and luxR are transcribed. LuxI produces 3-O-C6-HSL, which diffuses across the cell membrane and begins to accumulate. At high cell densities, when a threshold concentration of autoinducer is reached, 3-O-C6-HSL binds to LuxR, and this complex activates the transcription of the luxICDABEG operon, sustaining the increased levels of 3-O-C6-HSL and producing bioluminescence. (B) In S. aureus, the AIP signal is produced from the AgrD precursor, which is exported and processed by AgrB. When the AIP concentration is high, AIP binds to the AgrC-AgrA two-component system. AgrC autophosphorylates and transfers the phosphoryl group to AgrA. Phosphorylated AgrA binds to several promoters: the P2 promoter, for autofeedback regulation of the agr system; the P3 promoter, which transcribes the RNAIII sRNA for regulating several genes and the delta-toxin (hld); and the promoters of the PSMα and PSMβ toxins, for activation of their transcription. (C) AI-2 signaling in V. harveyi. LuxS synthesizes DPD, which spontaneously cyclizes, producing S-THMT-borate, a DPD derivative containing boron. At low concentrations of S-THMT-borate, LuxPQ activates its kinase activity, triggering LuxQ autophosphorylation, which starts with phosphate transfers from histidine (H) to aspartic acid (D). Then phosphate is passed on to LuxU and subsequently to LuxO. Phosphorylated LuxO activates the transcription of sRNAs Qrr1 to Qrr5. These sRNAs induce the destabilization of the luxR transcript and promote the translation of aphA, resulting in the repression of bioluminescence and the activation of genes required for virulence and biofilm formation, respectively. Upon S-THMT-borate binding, LuxPQ inhibits its kinase activity and acts as a phosphatase. Then LuxQ dephosphorylates LuxU, disabling the transfer of phosphate to LuxO. Dephosphorylated LuxO is inactive and fails to activate the expression of Qrr sRNAs, resulting in LuxR production and no translation of the aphA transcript. (D) AI-2 signaling in Salmonella. LuxS synthesizes DPD, which cyclizes into (2R,4S)-2-methyl-2,3,3,4-tetrahydroxytetrahydrofuran (R-THMF) in the absence of boron. At high cell densities, AI-2 is imported via the LsrB periplasmic transporter, which functions with the ABC transporter complex (LsrACD). Then AI-2 is phosphorylated by LsrK and bound to LsrR for derepression of the lsr operon.

Canonical regulation by AHLs involves an AHL synthase and its corresponding AHL receptor, encoded by luxI and luxR family genes, respectively. Once a critical signal concentration is reached, the AHL binds to its cognate LuxR receptor, and this complex activates the expression of specific target genes (Fig. 1A) (31). In Gram-positive bacteria, the agr system (agrBDCA operon) of Staphylococcus aureus is the prototype, where AIP is produced from the AgrD precursor, which is exported and processed by the transmembrane endopeptidase AgrB (Fig. 1B) (43). At a certain threshold concentration, AIP binds to the AgrC-AgrA two component system, in which AgrC undergoes autophosphorylation and then phosphorylates AgrA. Phosphorylated AgrA binds to the P2 promoter for autofeedback regulation of the agr system and activates the P3 promoter, transcribing RNAIII, a small regulatory RNA that also contains the gene for delta-toxin (hld). RNAIII is critical for the translational regulation of several target genes, including exoenzymes, toxins, and adhesins (43). Moreover, activated AgrA regulates the expression of the phenol-soluble modulin alpha (PSMα) and PSMβ peptides by directly binding to their promoters (44). In addition, AI-2 is synthesized by the LuxS synthase as a precursor, 4,5-hydroxy-2,3-pentanedione (DPD). DPD spontaneously cyclizes, resulting in two AI-2 forms. In the presence of boron, (2S,4S)-2-methyl-2,3,3,4-tetrahydroxytetrahydrofuran-borate (S-THMT-borate) is produced and serves as the active autoinducer in Vibrio spp. (Fig. 1C). However, in the absence of boron, DPD forms (2R,4S)-2-methyl-2,3,3,4-tetrahydroxytetrahydrofuran (R-THMF), which is involved in signaling in enteric bacteria such as Salmonella and E. coli (41, 45) (Fig. 1D). AI-2 is recognized by the LuxPQ periplasmic receptor in Vibrio spp., switching LuxQ into a phosphatase that inactivates downstream LuxU and LuxO, making the latter unable to activate transcription of the quorum-regulatory (Qrr) noncoding small RNAs (sRNAs) involved in luxR repression (41). In Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and E. coli, AI-2 is imported via the LsrB transporter and the ABC transporter complex (LsrACD). Then AI-2 is phosphorylated by LsrK and bound to LsrR to derepress the lsr operon (46).

Alternatively, QQ refers to a plethora of processes that impair QS signaling through the actions of enzymes (QQ enzymes) that degrade signaling molecules and chemical inhibitors (QS inhibitors [QSI]) that inactivate QS elements, all interfering with the synthesis, diffusion, accumulation, perception, and/or transduction of signals (47). QQ enzymes and QSI are produced by a wide range of species of bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes and offer natural mechanisms for clearing or recycling QS signaling molecules or establishing competitive relationships during microbe-microbe and host-microbe interactions involving colonization, biofilm formation, and host defense against infection (47). Most QQ enzymes modify AHLs and are categorized into three classes: lactonases, which open the homoserine lactone ring; acylases (or acylhydrolases), which remove acyl groups; and oxidoreductases, which inactivate AHLs by oxidation or the reduction of acyl chains (32). Additionally, QSI comprise highly structured, diverse compounds usually acting as competitive inhibitors, including phenylethylamides, cyclo-l-proline-l-tyrosine, phenolic derivatives, furanones, lactones, alkaloids, indoles, organosulfur compounds, and others, which are able to disrupt AHL, AI-2, PQS, and AIP signaling pathways (47).

Diverse bacterial cell density processes regulated by QS have been described to date, and the descriptions have been compiled in excellent reviews (34–36). Surprisingly, the relevance of QS signaling goes beyond bacteria, since signaling molecules can be perceived by viruses and eukaryotes in a type of interkingdom communication, including fungi, algae, invertebrates, mammals, and plants (48–52).

QUORUM SIGNALING AND PHAGE DEVELOPMENT

Lysogeny has been commonly suggested to be an adaptive reproductive strategy of phages enabling them to survive under adverse environmental conditions for long periods. The abundance of lysogens can be inversely correlated to primary productivity, since low nutrient conditions may reduce host densities and compromise further viral progeny (4). In agreement with this supposition, spontaneous induction of prophages has been observed under high-cell-density conditions (53, 54), whereas treatment of soil and groundwater samples with AHLs significantly increased viral abundance (55, 56). These findings strongly emphasize that population density may be a critical determinant of phage-host interactions; phages may exploit diverse QS communication systems to link host cell density and phage decisions, providing novel insights into the regulatory mechanisms implicated in the developmental fate of phages.

Leveraging host QS systems.

Phages have evolved elaborate mechanisms that take advantage of existing QS networks in their hosts. One of the first pieces of evidence, provided by Ghosh et al. (55), demonstrated that a cocktail of different synthetic AHLs or AHL-producing strains led to SOS-independent induction of prophage λ in E. coli. Even though it cannot produce AHLs, E. coli can respond to them via the SdiA receptor (57). Interestingly, λ prophage induction was dependent on SdiA and RscA, a positive regulator of exopolysaccharide synthesis known to positively regulate spontaneous SOS-independent λ induction (58), showing that RscA was upregulated via AHL-SdiA (55). Laganenka et al. (59) demonstrated the presence in E. coli ATCC 15144 of prophage T1, which had switched from the lysogenic to the lytic mode in response to the AI-2 provided in cell-free supernatants of E. coli W3110. Further analysis revealed that prophage induction was mediated by the phage-encoded Pir protein (59). Similar findings have been observed in Enterococcus faecalis, Vibrio cholerae, and Pseudomonas spp., in which prophage induction was promoted after exposure to AI-2, DPO, and 2-heptyl-3-hydroxy-4-quinolone (PQS), respectively (26, 60, 61), supporting the general assumption that QS autoinducers evoke prophage induction. Nevertheless, a recent study on Vibrio anguillarum revealed that H20-like prophage p47 is subjected to a QS-repressive mechanism that favors lysogeny over lysis under high-cell-density conditions (62). In this case, the prophage was repressed in a ΔvanO mutant background that mimicked a high-cell-density state, while prophage induction was observed in ΔvanT mutants. VanT and VanO are homologous to the LuxPQ signaling system in Vibrio harveyi, in which VanO (homologous to LuxO) is phosphorylated at low autoinducer concentrations (low cell density) and activates the expression of Qrr sRNAs that destabilize vanT (a luxR homolog) and that activate the translation of aphA, a low-cell-density master regulator. In contrast, under high autoinducer concentrations, VanO is inactivated by dephosphorylation, allowing the repression of AphA synthesis and the accumulation of VanT, which further activates the expression of its target genes (41, 62). In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, supplementation with penicillic acid, a QS inhibitor, increased productive infections of stationary-phase cells by the lytic phages K5 and C11 (63). In addition, phage DSM3 encodes the Aqs1 antiactivator protein to inhibit LasR, which may dampen antiphage defenses in P. aeruginosa (64). These facts highlight the possibility that the prophage response to autoinducers depends largely on the QS network architecture, but undoubtedly, QS plays pivotal roles in phage dynamics, influencing biofilm formation, virulence, colonization, and dispersal of bacterial hosts.

Notably, a recent preprint revealed that functional PqsD, an enzyme involved in PQS biosynthesis, is relevant for the efficient infection of the strictly lytic phage LUZ19 in P. aeruginosa. Moreover, supplementation with 2-heptyl-4(1H)-quinolone (HHQ, a PQS precursor) restored normal LUZ19 infection in the pqsD mutant (65). The PQS system has been associated with antiphage mechanisms intended to reduce burst sizes or prevent productive infection, limiting phage propagation across a host community (66). In this regard, Bru et al. (67) demonstrated that DMS3vir infection activated PQS signaling, which abolished swarming motility and repelled healthy microcolonies, thus serving as a warning signal of impending phage attack. However, phage LUZ19 induced a weaker host-mediated stress response than other Pseudomonas phages (66), likely using PQS signaling to create a favorable environment for productive infection instead of blocking host defense responses (65). In contrast, PT7 coevolution assays demonstrated that PQS signals can increase phage resistance in P. aeruginosa (68). In addition, Davies et al. (69) revealed that phage selection using temperate phages favored mutations in the lasR and mvfR loci, leading to disruption of AHL and PQS signaling, respectively.

Acquisition of QS and QQ homologs.

A few studies have dissected the molecular mechanisms behind the lysis-lysogeny decisions regulated by QS, showing how phages may rewire bacterial metabolism or redirect host processes via phage-encoded QS homologs. In the latter respect, Silpe and Bassler (26) provided a mechanistic view of how phage VP882 can perceive DPO via the phage-encoded VqmA receptor to activate the lytic pathway. In V. cholerae, DPO binds to bacterial VqmA to activate the expression of vqmR, which produces an sRNA that represses genes required for biofilm formation and toxin production (70). Phage VP882 exploits the host-produced DPO by binding to the phage VqmA receptor to induce the expression of the phage qtip gene, whose product interacts with and inactivates CI to derepress lytic genes. Interestingly, the authors demonstrated that the phage VqmA receptor may recognize the vqmR promoter in V. cholerae, but bacterial VqmA cannot bind to the qtip promoter, creating a unidirectional relationship in which prophage VP882 manipulates host QS to decide its reproductive fate (26).

Detailed analysis of metagenomes and genome databases has led to the identification of novel phage QS genes, such as those encoding LuxR homologs in Clostridium tyrobutyricum phage ϕCTP1 (71) and phages infecting Aeromonas spp. (72), as well as predicted agr systems (agrB, agrC, and agrD) in other phages infecting Paenibacillus species and Clostridium difficile (73). Given that the AgrBCD system lacks the response regulator AgrA, signal transduction is hypothesized to be realized by using AgrA or other effectors in the host. In contrast, other phages infecting Pseudomonas species encoded proteins containing LytTR domains, which may be AgrA homologs that might perceive Agr signals and function as response regulators (73). Strikingly, a phylogenetic analysis of agrB, agrC, and agrD homologs encoded by phiCDHM1 suggested that these genes had a host origin, since they were similar to members of the agr3 locus reported in several Clostridium strains (73), highlighting the role of horizontal gene transfer (HGT) as a plausible mechanism by which phages may acquire QS homologs. In an effort to functionally characterize phage-encoded QS proteins identified in silico, Silpe and Bassler (72) cloned and expressed the recombinant LuxRϕARM81ld and LuxRApop receptors, identified from metagenomes. The expressed LuxR-type receptors were insoluble proteins, as evidenced by the fact that they were only found in the whole-cell lysate; however, they were able to bind to C4-, C6-, and C8-HSL and then become soluble, since they were present in the whole-cell lysate and soluble fractions (72). These findings support the notion that LuxRϕARM81ld and LuxRApop encode functional LuxR receptors that are able to bind to AHLs, although their role in phage biology remains to be addressed.

Finally, a putative acylhydrolase was found in phage ϕPLPEa, infecting Iodobacter spp. (74). This acylhydrolase may be involved in AHL degradation in its host or bacterial neighbors, which we hypothesized may confer competitive advantages on its host and interfere with QS-dependent phenotypes in competitors, but importantly, it might also modulate the lysis-lysogeny decisions of other phages that depend on QS signals, as we explain above.

Arbitrium: an emerging phage-phage communication system.

The novel peptide-based phage communication system termed “arbitrium” was discovered in the phages phi3T and SPbeta, which lytically infect Bacillus subtilis strains and, after several productive infections, promote lysogeny (27). The arbitrium system comprises three elements: aimP encodes a propeptide that is secreted and then processed by extracellular proteases to generate a mature arbitrium peptide (27); aimR encodes a receptor with a predicted tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domain (27), a typical motif found in intracellular peptide receptors of the RRNPP family in QS systems from Gram-positive bacteria (75); and aimX harbors a predicted transcript that produces a peptide and a small noncoding RNA that exerts a negative effect on lysogeny (27). Preliminary findings in phage Wbeta have shown that noncoding AimX RNA negatively regulates the cI gene, which is located on the opposite strand overlapping aimX, through RNA antisense interactions (76).

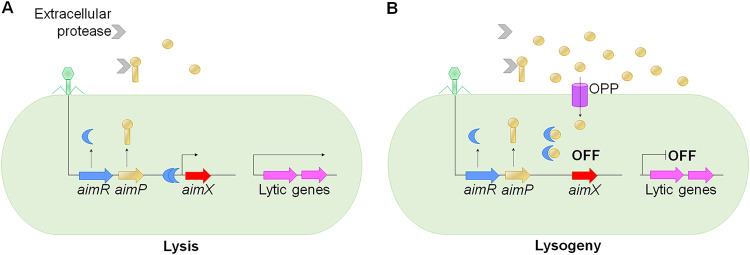

Upon phi3T infection, the phage produces the AimP hexapeptide and AimR receptor (27). However, due to the low AimP concentrations during the initial rounds of replication, the AimR receptor dimerizes and binds upstream of the aimX gene, resulting in the expression of lytic genes (77). After several productive infections, the AimP concentration increases in the growth medium, and AimP is taken up by nearby bacteria through the oligopeptide permease transporter (OPP). Once internalized, AimP binds to the AimR dimer, inducing conformational changes, and finally dissociates into inactive monomers unable to bind to the aimX gene, promoting the shift to a lysogenic life cycle (27) (Fig. 2). In contrast, in SPbeta one AimP molecule binds to each AimR subunit, stabilizing its dimeric state (78, 79). Nevertheless, SPbeta switched into the lysogenic cycle, because the AimP-AimR complex induced a compact conformation that impeded the recognition of aimX operator motifs (80).

FIG 2.

Canonical arbitrium communication system in phages. (A) Upon phi3T infection, the phage activates the transcription of aimP, which encodes a 43-amino-acid propeptide that is secreted and then processed by extracellular proteases, producing a mature 6-amino-acid peptide. In initial replication rounds, when the AimP concentration is low, the AimR receptor dimerizes and binds upstream of the aimX operator activating its transcription, resulting in the expression of lytic genes. (B) After several productive infections, the AimP concentration in the growth medium increases, and AimP is internalized by the oligopeptide permease transporter (OPP). Then AimP binds to the AimR dimer, triggering dissociation into inactive monomers, which cannot bind to the aimX gene, thus promoting the lysogenic life cycle by an unknown mechanism.

Notably, in silico surveys have revealed that arbitrium-like systems may be a common feature that coevolved with phages and conjugative elements that reside in members of Firmicutes. Erez et al. (27) identified 112 AimR homologs in SPbeta group phages, in which aimP and aimX homologs were present at 72% and 15%, respectively, mostly organized in an aimR-aimP-aimX gene cluster. A more-extended search, including bacterial, archaeal, and viral genomes, led to the identification of 1,180 AimR homologs in phages (mainly from the SPbeta and Wbeta groups) and conjugative elements, 96% of which also contained an aimP-like gene (76). Phylogenetic analysis found that AimR homologs clustered into 10 different clades; the peptide sequence and size differed in each clade, and the mature peptide could be as long as 10 amino acids (76), in agreement with previous observations of the RRNPP family of cytoplasmic regulatory receptors (81). Despite previous phylogenetic analysis suggesting that AimR is not related to RRNPP members (81), structural analysis of SPbeta AimR confirmed their functional similarities, leading to the proposal that AimR is a new member of this family and strongly suggesting that arbitrium elements may be acquired from host bacteria by phages using them for establishing their own communication system (80).

The functionality of predicted peptides was demonstrated for the EIKPGG (6 amino acids) and MMSEPGGGGW (10 amino acids) peptides, encoded by the Wbeta and Waukesha92-like phage groups, respectively; lysogeny was triggered upon supplementation with 1 μM peptide (76). Moreover, structural insights revealed that arbitrium peptides contain a conserved C-terminal sequence, while only a few key residues on the AimR binding groove have been characterized with respect to peptide selectivity. This suggests that the AimR receptor may be promiscuous and interact with similar AimP peptides, giving rise to cross talk among closer phages to favor their survival over that of more genetically distant phages (80). Notably, orphan AimR receptors have been identified in some phages and conjugative elements (76), likely indicating that despite their inability to produce a peptide signal, they might be perceived.

A DOUBLE-EDGED SWORD: QS MODULATION OF PHAGE RESISTANCE MECHANISMS

In addition to the emerging evidence of QS participation in social communication during phage development, QS has also been involved in several antiphage protective mechanisms in bacteria, including the activation of CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats)-Cas (CRISPR-associated proteins) systems, the downregulation of cell surface proteins, the upregulation of proteases, and the induction of cell suicide upon phage infection (82–87).

The CRISPR-Cas system can be used to provide adaptive immunity in bacteria through the incorporation of short invader-derived sequences, known as spacers, that are incorporated into the CRISPR array and can be further transcribed and processed by Cas to target complementary invading nucleic acids, triggering their destruction and preventing infection (88). Because the risk of viral predation or HGT increases in high-cell-density populations, some studies have linked CRISPR-Cas systems to QS control. Patterson et al. (83) demonstrated that type I-E, I-F, and III-A CRISPR-Cas systems in Serratia species were upregulated by AHLs in high-cell-density cultures. Interestingly, the activation of a CRISPR-Cas locus was dependent on a derepression mechanism in which the SmaR repressor was released from CRISPR-Cas promoters upon AHL binding (83). Similarly, AHLs positively regulated the cas3 gene and promoted spacer acquisition in P. aeruginosa (82, 89). Collectively, these findings are consistent with previous studies of QS mutants that showed reduced expression of CRISPR-Cas genes (90, 91) and lower interference in ΔlasI ΔrhlI double mutants (89), supporting the notion that QS is a regulator of adaptive immunity. In contrast, Li et al. (92) demonstrated that type I CRISPR-Cas systems can also modulate endogenous QS by targeting the lasR transcript to evade the human host immune system and facilitating P. aeruginosa invasion, indicating a complex regulatory mechanism involving QS and CRISPR-Cas systems. Given the importance of CRISPR-Cas systems in adaptive immunity, phages have coevolved elaborate mechanisms to circumvent bacterial defenses through the synthesis of anti-CRISPR proteins, enabling successful phage infection (93–97).

Remarkably, the abundance of bacterial surface receptors is controlled by QS, providing an additional way to control phage infection. This phenomenon was observed in phage λ and the broad-host-range phage χ infecting E. coli, in which AHLs induced the downregulation of both receptors (84). Moreover, AHLs and CAI-1 promote reductions in the levels of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) O-antigen and OmpK phage receptors on the surfaces of V. anguillarum and V. cholerae cells, respectively (85, 98), and the upregulation of phage-degrading hemagglutinin protease (HAP) (85).

In contrast, other studies have revealed that bacteria may trigger their own cell death through toxin-antitoxin (TA) modules upon phage infection, which has been reported for the three types of TA systems (type I, hok/sok; type II, mazEF; type III, toxinIN) (99–101). TA modules are part of abortive infection (Abi) systems, in which a phage enters successfully but its development fails, thereby preventing phage spreading and protecting the bacterial population (102). In the case of type II, Hazan and Engelberg-Kulka (100) showed that the mazEF TA module induced cell death upon prophage P1 induction by thermal activation or in the presence of virulent P1 particles in E. coli cultures. Later, Kolodkin-Gal et al. (86) identified the extracellular death factor (EDF), a signaling linear pentapeptide, that is required for mazEF-mediated cell death in a cell density-dependent manner. Supporting these findings, peptides related to EDF, which induces mazEF-dependent cell death in E. coli, have been reported in B. subtilis and P. aeruginosa, revealing a distinct family of QS peptides able to induce altruistic suicide or kill neighboring bacteria (87). Notably, other QS signals have not been reported in connection with the modulation of TA systems to date.

BIOLOGICAL IMPLICATIONS

Phage-host dynamics in natural environments.

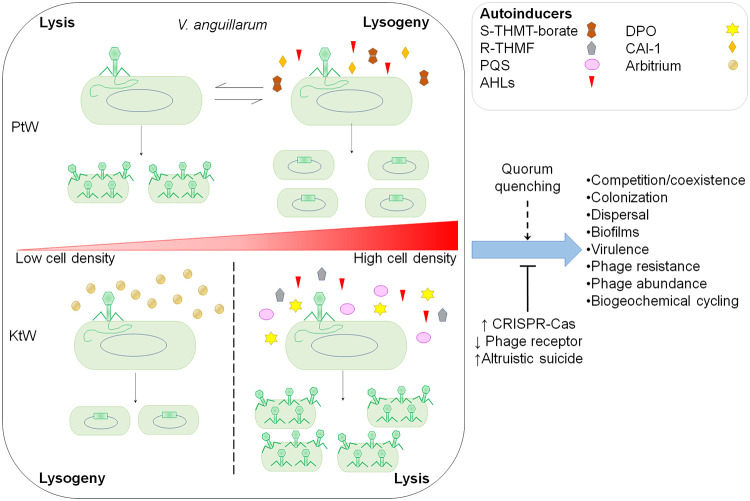

Studies on marine environments and soils estimate that lysogeny is more common under conditions of lower productivity and reduced cell host abundance, while lysis predominates under more favorable conditions (55, 103). Accordingly, the predominance of lysogeny has explained the lower virus-to-microorganism ratio (VMR) observed in environments supporting the Kill-the-Winner (KtW) model, which explains that lysis is predominant when bacterial populations reach high cell densities (104), in accord with the rationale that QS may be a determinant for shifting from a lysogenic to a lytic fate when the host population increases (55, 60). Nevertheless, studies across marine environments and desert soils have demonstrated that the VMR exhibited substantial variations from the typical 10:1 ratio with regard to phage and microbial abundances; they have shown nonlinearity in the VMR under different spatiotemporal conditions (105, 106) and revealed lower VMRs at increasing microbial densities, a temperate phage dynamic that cannot be explained by the KtW model. These observations have been clarified by recent insights regarding a QS-mediated repressive mechanism (62), supporting the Piggyback-the-Winner (PtW) model, which predicts that the lysogeny pathway is favored for microorganisms in high abundance (107). According to the PtW model, phages integrate into host genomes at high cell densities to reduce phage predation and protect the host from infection by closely related phages via superinfection exclusion, which may be important in spatially structured microbial communities for niche invasion (Fig. 3) (108).

FIG 3.

Impact of the QS and QQ networks on the modulation of phage-host interactions. QS signaling is a determinant for phage development in response to host cell density, in which the outcome depends largely on the autoinducers used for phages and the host QS architecture. Thereby, QS-repressive mechanisms, such as the signaling pathways transduced by VanO in V. anguillarum, may promote lytic development at a low cell density, providing evidence for the Piggyback-the-Winner (PtW) model. Notably, VanO integrates the perception of AHL, AI-2 (S-THMT-borate), and CAI-1 signals by VanN (LuxN), VanPQ (LuxPQ), and CqsS, respectively, which might result in promoting lysogeny at high cell densities (62). Other autoinducers, such as AHLs, AI-2 (R-THMF), PQS, and DPO, appear to be important for conducting lytic development at high cell densities, whereas arbitrium-based communication in phages promotes lysogeny after several rounds of productive infections, helping to protect the host at low cell densities from phage predation, both contributing to the Kill-the-Winner (KtW) model. Thus, QS might constrain certain phage-host interactions as a result of a long coevolutionary arms race between specific phage-bacterium pairs, as is the case for arbitrium, which is found only in Firmicutes. From another perspective, antiphage strategies induced by QS and QQ factors encoded by phages might restrict the lysis-lysogeny decisions of phages harbored by specific bacterial groups, impacting several ecological and evolutive aspects of microbial communities.

In a similar manner, arbitrium-like systems can control phage populations by perceiving the abundance of lysogens, presumably to avoid superinfection of lysogens infected with the same phage, or can manipulate the behavior of genetically related phages within the microbial community (76). It has been suggested that QS may act in a taxon-specific manner, because QS signals may affect a subset of phages infecting closely related hosts within complex communities (109). The latter supposition is supported by a recent study showing that eight different AHLs triggered prophage induction in soil microbial communities, leading to specific changes in bacterial composition that depend on the type of AHL used for induction (56). These findings highlight the fact that the responsiveness of phages to QS is widespread in nature, playing important roles in defining community composition and in resource redistribution upon the lysis of bacteria of certain taxa (110). Thus, understanding the interplay between phage and host signaling networks is important for determining the biological outcomes of phage-host dynamics in natural environments in terms of colonization, biofilm formation, competition, and reproduction, among other biological processes.

Predation and competition.

A growing body of evidence supports the possibility that phages “listen” to QS signals produced by the host or neighboring cells affecting competition, one of the main driving forces that determines the structure of ecological communities. Phages may promote microbial diversity through reduction of the competitiveness of dominant species or specific strains, mediating coexistence in microbial communities (111). For example, the commensal bacteria Curvibacter spp. and Duganella spp. coexist in the metazoan Hydra vulgaris to protect it against fungal infections (112). In coculture, Curvibacter spp. modulated the growth rate of the dominant Duganella spp. by its own prophage, which infected Duganella spp. in the lytic mode (113). Other temperate phages confer competitive advantages on bacteria through lysogeny, which is critical for the persistence of rare hosts within the community, because it allows them to spread in abundant susceptible populations (69, 114). Interestingly, H. vulgaris can chemically modify the AHLs produced by Curvibacter through oxidoreductase activity modifying 3-O-C12-HSL into 3-OH-C12-HSL, which enables host colonization (115). Because modified AHL induces a specific transcriptional response, it might also modulate prophage induction to provide additional competitive advantages for successful colonization. In a general context, phage composition might also be shaped through arbitrium systems, in which a signal-producing phage may interfere with, or manipulate the propagation of, closely related phages that perceive the signal, indirectly affecting the composition of susceptible bacterial hosts.

Biofilms are formed by complex microbial communities embedded in an extracellular matrix that allows them to adhere to surfaces, which commonly facilitates colonization and the spread of bacteria, largely affecting mutualistic and parasitic symbiosis with other bacteria and multicellular organisms (116). Phages may affect biofilms in two ways: they may degrade biofilms via phage-encoded depolymerases and other lytic enzymes (117), or they may facilitate biofilm formation through prophage induction, which favors the release of bacterial components such as environmental DNA (eDNA) to strengthen the biofilm matrix (118), a process that occurs mostly in high-cell-density populations. Tan et al. (62) discovered a QS-repressive mechanism in V. anguillarum, where biofilm development was enhanced upon prophage induction in a low-cell-density locked state using ΔvanT mutants, supporting the role of prophages in biofilm formation and progression but at low cell densities (119), giving a new perspective on noncanonical QS regulation to enhance host fitness.

Under other circumstances, the abundance of bacteria can be controlled by QQ, in which QS signaling interference confers competitive advantages on QQ producers by inactivating enzymes or inhibitory compounds (32). For example, Variovorax paradoxus degrades AHLs through lactonase activity and uses them as a carbon source, inhibiting QS-dependent neighboring bacteria (120). In addition, the red alga Delisea pulchra produces halogenated furanones to mimic AHLs and promote AHL receptor degradation so as to regulate bacterial composition on algal thalli (121). This process may be essential for phages as well, since some of them encode acylhydrolases (74) and QS negative regulators (64), highlighting the critical role of antagonizing QS, although the functional implications are not fully understood.

Changes in bacterial metabolism.

With the emergent role of QS as a determinant in phage fate, questions have been raised about the extent of prophages in bacterial physiology. Phages provide accessory genes, associated mainly with changes in pathogen virulence, to their hosts (122). Interestingly, studies have revealed that prophages can suppress host metabolic genes through phage-encoded repressors, enabling bacteria to survive in unfavorable environments (123), or can manipulate host transcription via phage promoters controlling host genes upon integration (124). In agreement with these studies, it is plausible that phages may reprogram host metabolism and gene expression through phage-encoded QS regulators to enhance productive infections, as in the case of Aqs1 (64) or VqmA (26), but may also modulate pathogenicity traits, since many of these are QS regulated. Furthermore, phage-encoded QQ enzymes can function as modulators of signaling molecules in complex natural communities, ultimately influencing diverse interspecies interactions and social processes, as seen previously with biofilms in granular sludge models (125). In addition, phages also inactivate clinically important traits through insertional mutagenesis, which has been reported for motility and QS genes in P. aeruginosa (69).

Horizontal gene transfer.

Phages play pivotal roles in mediating HGT between strains and bacterial species by transduction, conferring accessory functions (126). In this respect, AI-2 has been shown to mediate pp5 induction in E. faecalis, enhancing phage transduction in an avirulent probiotic strain and thus giving rise to virulent phenotypes (60). This is a particular problem during phage therapy, since phages might convert avirulent strains into virulent strains, spreading pathogenicity traits among indigenous microbiota, which may worsen infections caused by signal producers, leading to undesirable outcomes of phage-based treatments. Nevertheless, the impact of phages goes beyond the potential transduction-mediated gene transfer among bacteria. Studies have documented that diverse mobile elements use QS circuits or encode genes similar to arbitrium-like systems to control HGT, as in the case of Ti plasmid conjugation mediated by AHLs (127) and the peptide-repressed conjugation of the integrative-conjugative element ICEBs1 (128) and plasmid pLS20 in B. subtilis (129). Furthermore, AimR receptors can potentially be promiscuous and bind to similar AimP peptides—a scenario supported by structural studies on AimR (80) and the finding that some shorter versions of the 10-amino-acid arbitrium peptide can still induce lysogeny (76)—opening the possibility for interactions with closely related phages. Hence, the potential cross talk mediated by phage-encoded QS regulators or arbitrium elements can influence HGT of plasmids, mobile elements, or other phages harbored by the same host or neighboring bacteria. In contrast, HGT has been pivotal for the acquisition of QS and QQ homologs by phages, giving them the opportunity to listen, interfere with, or respond to conversations harbored by bacteria and phage populations, shaping the coevolution of host-parasite interactions.

Coevolutionary implications.

The paradoxical roles of QS in phage development have led to new questions about the contribution of interactive effects of QS-mediated processes and the final outcomes in the context of complex communities. Although CRISPR-Cas systems activate adaptive immunity against phages, a recent study has suggested that CRISPR-Cas pressure may also contribute to accelerating phage evolution by promoting the accumulation of resistant phage mutants (130). In addition, phages may impose a driving selective pressure to keep functional QS systems in bacteria. Saucedo-Mora et al. (131) showed that lysogenic phages D3112 and JBD30 selected preferentially QS-proficient P. aeruginosa strains rather than QS mutants (lasR rhlR mutants) in competition experiments, increasing the virulence of their hosts for Galleria mellonella infection. Contrasting observations were made for the temperate phage ϕ4, which integrates into motility and QS-related genes in P. aeruginosa and selects QS-deficient populations during chronic infections (69), suggesting that while QS proficiency is required for early host colonization and infection, further pathogen genetic diversification favors cheater populations lacking QS systems so as to reduce fitness costs in the long term (132).

Other coevolutionary studies revealed that the lytic PT7 phage reduced P. aeruginosa growth to a greater extent than the lasR mutant (133) but that evolved P. aeruginosa populations grew better in the presence of the ancestral lytic phages PT7 and 14/1, implying that the development of phage resistance was likely mediated by the activation of the PQS system in the short term (68). Nevertheless, P. aeruginosa developed lower resistance rates for ancestral and coevolved phage PT7 in the presence of competitors, in contrast with the higher levels observed in lasR mutants (68). These results imply that although QS may favor the development of phage resistance, the contribution of competition and possible additional pressures can change phage-bacterium interactions due to the pleiotropic cost of adaptation. However, the extent of this outcome depends largely on nutrient conditions, the composition of competitors, the host strain and genotype, and the contribution of phages to virulent phenotypes during infection (68). Moreover, these evolutionary studies have been conducted in P. aeruginosa, underlining the need to evaluate coevolution dynamics in other bacterial models with distinct QS genetic backgrounds in the future, including the effects of individual or more phages, resembling different environmental contexts.

Taken together, these results may have relevant implications for phage therapy. The fact that phages have a tendency to select QS-proficient bacteria might result in the emergence of more-virulent strains in clinical and natural niches, since many virulence factors are regulated by QS (131). Similarly, the potential transduction of virulence elements in a QS-dependent manner can convert avirulent strains into virulent strains (60). Finally, the impact of lysogenic phages contributing to virulent phenotypes, as in the case of P. aeruginosa, has not been considered (69). Overall, these possibilities may lead to inconsistent or unexpected phage therapy outcomes. Interestingly, coevolutionary studies using evolved bacterial systems have shown that microbial competitors reduced the rate of phage resistance and the focal pathogen densities (133), which may benefit phage therapy by exerting indirect effects on the pathogen through a polymicrobial community. However, these assumptions should be considered carefully, since these effects might be specific to the genetic composition of a community and to a stage of infection, highlighting the importance of coevolutionary studies in polymicrobial contexts.

Finally, the presence of arbitrium elements may be undesirable for phage therapy, because arbitrium-harboring phages, plasmids, and other mobile elements carry toxins and virulence factors (76), which may impose a risk for horizontal transfer of deleterious elements among bacteria during therapeutic applications. Hence, understanding phage-host interactions governed by QS and their relative contributions in the context of coevolutionary scenarios is crucial for explaining phage-host dynamics in natural environments, as well as for the design of tailored treatments based on phages and for improvement of the long-term efficiency of phage therapy in eradicateing bacterial pathogens.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Despite significant progress in recognizing the critical role of QS signaling in phage-bacterium interactions and evolution, the study of the biological significance of QS is still in its infancy, because the characterization of only a few phage-bacterium pairs has been completed. Nonetheless, because several QS and QQ factors have been identified in phage genomes in silico, the increasing availability of genomic sequences in databases will be pivotal for the prediction of potential phage-bacterium interactions that may be experimentally tested, providing novel insights into the determinants of phage development. The best example of this research was provided by Silpe and Bassler (26), who used genomic databases to search for DPO-binding proteins similar to VqmA in V. cholerae and identified a VqmA homolog sequence in the VP882 prophage, the first step to describing a novel mechanism used by phages to enhance their replication in the presence of high levels of autoinducers.

This emerging field has led to new questions about whether other distinct QS signals can be used by phages to infect specific bacterial groups harboring these systems, whether phages have acquired other related QS/QQ homologs to subvert host communication to their own benefit, or whether they harbor additional communication systems such as arbitrium. In addition, in complex bacteria in which more than one autoinducer regulates several cellular processes (for example, P. aeruginosa and Vibrio spp.), it remains to be determined when a signaling molecule functions as a negative or a positive regulator of phage replication, when this occurs under specific conditions, and whether both mechanisms are simultaneously activated as opposite and/or competitive processes, considering that the predominant mechanism will define the final outcome. Unveiling novel mechanisms governed by QS will have implications for understanding the relative importance of QS as a driver of ecological and evolutionary processes in complex ecosystems modulated by phage-host coevolution (134), which is proposed as an agent of fluctuating selection for maintaining the diversity of microbial populations (135).

From a therapeutic perspective, a deeper understanding of the impact of QS signaling in regulating parasitic relationships may allow for the manipulation of the phage-host microenvironment to encourage specific outcomes. These findings will be essential for the design of tailored phage therapies, establishing additional criteria for selection to avoid phages possessing harmful features (e.g., arbitrium elements or pathogenicity traits) or exerting selective pressures favoring QS-proficient and virulent strains, as well as for testing combinations with other therapies. The latter will be achieved based on the microbial composition of an infection. In this context, coevolutionary studies of polymicrobial communities will be useful for the prediction of potential outcomes in phage therapy or for proving the effectiveness and safety of combined therapies with anti-QS compounds, as suggested for the treatment of bacterial infections (136, 137). Moreover, it will be necessary to unravel the QS mechanisms driving phage resistance in order to make phage therapy more effective in the long term. Simultaneously, the assessment of phage cocktails will be relevant for determining whether phage mixtures reduce the selection of more-virulent QS-proficient strains or prevent phage resistance, as suggested previously (138). This may explain, at least in part, the phenomenon of phage adaptation, which refers to a common practice applied to commercial cocktails used in clinical settings that are intended to overcome bacterial resistance and increase the efficacy of phages against emergent pathogens (139, 140), a practice that may also be exploited for phage therapy design.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

C.V. is supported by Cátedras CONACYT research project 784, “Functional Genomics of Organisms for Food and Agriculture to Mexico.”

Biographies

Josefina León-Félix completed her postgraduate studies at the Department of Infectomics and Molecular Pathogenesis, Center for Research and Advanced Studies, National Polytechnical Institute, Mexico (CINVESTAV-IPN), in May 2004 and immediately afterwards joined the Research Center in Food and Development (CIAD) as a research professor in molecular biology and genomics, where she currently holds the position of group head professor on food biotechnology issues. She has focused mainly on the study of bacteriophages as agents of biological control and phage therapy for 16 years. This is a topic that she is passionate about, because it contributes significantly to addressing the global problem of antimicrobial resistance, as well as contributing to the improvement of human, plant, and animal health and to the production of healthy and safe food.

Claudia Villicaña received her bachelor’s degree in marine biology at the Autonomic University of Baja California Sur (UABCS) in 2004 and her master’s degree in 2007 after studying quorum sensing in marine bacteria at the Northwestern Center for Biological Research (CIBNOR). In 2013, she earned her Ph.D. in biochemical sciences working with Drosophila at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, where she acquired experience in molecular biology and genetics. Afterwards, she worked at CIBNOR and the Autonomous University of Yucatan as a researcher involved in projects concerning plant molecular biology and stem cells. In 2017, she joined the Research Center in Food and Development (CIAD) as an associate research professor in the Molecular Biology and Genomics Laboratory. Currently, she is focused on the isolation and characterization of phages, their potential for phage therapy, and the cloning and characterization of phage-encoded lytic enzymes and depolymerases as alternatives for the treatment of bacterial infections.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hendrix RW, Smith MCM, Burns RN, Ford ME, Hatfull GF. 1999. Evolutionary relationships among diverse bacteriophages and prophages: all the world’s a phage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:2192–2197. 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuhrman JA. 1999. Marine viruses and their biogeochemical and ecological effects. Nature 399:541–548. 10.1038/21119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shikuma NJ, Pilhofer M, Weiss GL, Hadfield MG, Jensen GJ, Newman DK. 2014. Marine tubeworm metamorphosis induced by arrays of bacterial phage tail-like structures. Science 343:529–533. 10.1126/science.1246794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howard-Varona C, Hargreaves KR, Abedon ST, Sullivan MB. 2017. Lysogeny in nature: mechanisms, impact and ecology of temperate phages. ISME J 11:1511–1520. 10.1038/ismej.2017.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weitz JS, Wilhelm SW. 2012. Ocean viruses and their effects on microbial communities and biogeochemical cycles. F1000 Biol Rep 4:17. 10.3410/B4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hobbs Z, Abedon ST. 2016. Diversity of phage infection types and associated terminology: the problem with ‘lytic or lysogenic.’ FEMS Microbiol Lett 363:fnw047. 10.1093/femsle/fnw047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Łoś M, Węgrzyn G. 2012. Pseudolysogeny. Adv Virus Res 82:339–349. 10.1016/B978-0-12-394621-8.00019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ptashne M. 2004. A genetic switch: phage lambda revisited, 3rd ed, vol 3. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kourilsky P. 1973. Lysogenization by bacteriophage lambda. I. Multiple infection and the lysogenic response. Mol Gen Genet 122:183–195. 10.1007/BF00435190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kourilsky P. 1974. Lysogenization by bacteriophage lambda-II: identification of genes involved in the multiplicity dependent processes. Biochimie 56:1511–1516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yen KM, Gussin GN. 1980. Kinetics of bacteriophage lambda repressor synthesis directed by the PRE promoter: influence of temperature, multiplicity of infection, and mutation of PRM or the cro gene. Mol Gen Genet 179:409–419. 10.1007/BF00425472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.St-Pierre F, Endy D. 2008. Determination of cell fate selection during phage lambda infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:20705–20710. 10.1073/pnas.0808831105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Court DL, Oppenheim AB, Adhya SL. 2007. A new look at bacteriophage lambda genetic networks. J Bacteriol 189:298–304. 10.1128/JB.01215-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shao Q, Trinh JT, Zeng L. 2019. High-resolution studies of lysis-lysogeny decision-making in bacteriophage lambda. J Biol Chem 294:3343–3349. 10.1074/jbc.TM118.003209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Semsey S, Campion C, Mohamed A, Svenningsen SL. 2015. How long can bacteriophage λ change its mind? Bacteriophage 5:e1012930. 10.1080/21597081.2015.1012930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Czyz A, Los M, Wrobel B, Wegrzyn G. 2001. Inhibition of spontaneous induction of lambdoid prophages in Escherichia coli cultures: simple procedures with possible biotechnological applications. BMC Biotechnol 1:1. 10.1186/1472-6750-1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casjens SR, Hendrix RW. 2015. Bacteriophage lambda: early pioneer and still relevant. Virology 479–480:310–330. 10.1016/j.virol.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williamson SJ, Paul JH. 2006. Environmental factors that influence the transition from lysogenic to lytic existence in the phiHSIC/Listonella pelagia marine phage-host system. Microb Ecol 52:217–225. 10.1007/s00248-006-9113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Binnenkade L, Teichmann L, Thormann KM. 2014. Iron triggers λSo prophage induction and release of extracellular DNA in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:5304–5316. 10.1128/AEM.01480-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lunde M, Aastveit AH, Blatny JM, Nes IF. 2005. Effects of diverse environmental conditions on ϕLC3 prophage stability in Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:721–727. 10.1128/AEM.71.2.721-727.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goerke C, Köller J, Wolz C. 2006. Ciprofloxacin and trimethoprim cause phage induction and virulence modulation in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:171–177. 10.1128/AAC.50.1.171-177.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Setlow JK, Boling ME, Allison DP, Beattie KL. 1973. Relationship between prophage induction and transformation in Haemophilus influenzae. J Bacteriol 115:153–161. 10.1128/JB.115.1.153-161.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ennis DG, Fisher B, Edmiston S, Mount DW. 1985. Dual role for Escherichia coli RecA protein in SOS mutagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 82:3325–3329. 10.1073/pnas.82.10.3325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banks DJ, Lei B, Musser JM. 2003. Prophage induction and expression of prophage-encoded virulence factors in group A Streptococcus serotype M3 strain MGAS315. Infect Immun 71:7079–7086. 10.1128/iai.71.12.7079-7086.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cochran PK, Kellogg CA, Paul JH. 1998. Prophage induction of indigenous marine lysogenic bacteria by environmental pollutants. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 164:125–133. 10.3354/meps164125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silpe JE, Bassler BL. 2019. A host-produced quorum-sensing autoinducer controls a phage lysis-lysogeny decision. Cell 176:268–280. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erez Z, Steinberger-Levy I, Shamir M, Doron S, Stokar-Avihail A, Peleg Y, Melamed S, Leavitt A, Savidor A, Albeck S, Amitai G, Sorek R. 2017. Communication between viruses guides lysis-lysogeny decisions. Nature 541:488–493. 10.1038/nature21049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christie GE, Dokland T. 2012. Pirates of the Caudovirales. Virology 434:210–221. 10.1016/j.virol.2012.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matos RC, Lapaque N, Rigottier-Gois L, Debarbieux L, Meylheuc T, Gonzalez-Zorn B, Repoila F, Lopes MDF, Serror P. 2013. Enterococcus faecalis prophage dynamics and contributions to pathogenic traits. PLoS Genet 9:e1003539. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams P. 2007. Quorum sensing, communication and cross-kingdom signalling in the bacterial world. Microbiology (Reading) 153:3923–3938. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/012856-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abisado RG, Benomar S, Klaus JR, Dandekar AA, Chandler JR. 2018. Bacterial quorum sensing and microbial community interactions. mBio 9:e02331-17. 10.1128/mBio.02331-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LaSarre B, Federle MJ. 2013. Exploiting quorum sensing to confuse bacterial pathogens. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 77:73–111. 10.1128/MMBR.00046-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eberhard A, Burlingame AL, Eberhard C, Kenyon GL, Nealson KH, Oppenheimer NJ. 1981. Structural identification of autoinducer of Photobacterium fischeri luciferase. Biochemistry 20:2444–2449. 10.1021/bi00512a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Castillo-Juárez I, Maeda T, Mandujano-Tinoco EA, Tomás M, Pérez-Eretza B, García-Contreras SJ, Wood TK, García-Contreras R. 2015. Role of quorum sensing in bacterial infections. World J Clin Cases 3:575–598. 10.12998/wjcc.v3.i7.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanchez-Contreras M, Bauer WD, Gao M, Robinson JB, Allan Downie J. 2007. Quorum-sensing regulation in rhizobia and its role in symbiotic interactions with legumes. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 362:1149–1163. 10.1098/rstb.2007.2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Helman Y, Chernin L. 2015. Silencing the mob: disrupting quorum sensing as a means to fight plant disease. Mol Plant Pathol 16:316–329. 10.1111/mpp.12180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fuqua C, Parsek MR, Greenberg EP. 2001. Regulation of gene expression by cell-to-cell communication: acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing. Annu Rev Genet 35:439–468. 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.090913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kleerebezem M, Quadri LE, Kuipers OP, de Vos WM. 1997. Quorum sensing by peptide pheromones and two-component signal-transduction systems in Gram-positive bacteria. Mol Microbiol 24:895–904. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4251782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen X, Schauder S, Potier N, Van Dorsselaer A, Pelczer I, Bassler BL, Hughson FM. 2002. Structural identification of a bacterial quorum-sensing signal containing boron. Nature 415:545–549. 10.1038/415545a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flavier AB, Clough SJ, Schell MA, Denny TP. 1997. Identification of 3-hydroxypalmitic acid methyl ester as a novel autoregulator controlling virulence in Ralstonia solanacearum. Mol Microbiol 26:251–259. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5661945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Papenfort K, Bassler BL. 2016. Quorum sensing signal-response systems in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 14:576–588. 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim CS, Gatsios A, Cuesta S, Lam YC, Wei Z, Chen H, Russell RM, Shine EE, Wang R, Wyche TP, Piizzi G, Flavell RA, Palm NW, Sperandio V, Crawford JM. 2020. Characterization of autoinducer-3 structure and biosynthesis in E. coli. ACS Cent Sci 6:197–206. 10.1021/acscentsci.9b01076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Le KY, Otto M. 2015. Quorum-sensing regulation in staphylococci—an overview. Front Microbiol 6:1174. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Queck SY, Jameson-Lee M, Villaruz AE, Bach THL, Khan BA, Sturdevant DE, Ricklefs SM, Li M, Otto M. 2008. RNAIII-independent target gene control by the agr quorum-sensing system: insight into the evolution of virulence regulation in Staphyloccocus aureus. Mol Cell 32:150–158. 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller ST, Xavier KB, Campagna SR, Taga ME, Semmelhack MF, Bassler BL, Hughson FM. 2004. Salmonella typhimurium recognizes a chemically distinct form of the bacterial quorum-sensing signal AI-2. Mol Cell 15:677–687. 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Federle MJ. 2009. Autoinducer-2-based chemical communication in bacteria: complexities of interspecies signaling. Contrib Microbiol 16:18–32. 10.1159/000219371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grandclément C, Tannières M, Moréra S, Dessaux Y, Faure D. 2016. Quorum quenching: role in nature and applied developments. FEMS Microbiol Rev 40:86–116. 10.1093/femsre/fuv038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hogan DA, Vik A, Kolter R. 2004. A Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing molecule influences Candida albicans morphology. Mol Microbiol 54:1212–1223. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tait K, Joint I, Daykin M, Milton DL, Williams P, Cámara M. 2005. Disruption of quorum sensing in seawater abolishes attraction of zoospores of the green alga Ulva to bacterial biofilms. Environ Microbiol 7:229–240. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tait K, Havenhand J. 2013. Investigating a possible role for the bacterial signal molecules N-acylhomoserine lactones in Balanus improvisus cyprid settlement. Mol Ecol 22:2588–2602. 10.1111/mec.12273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith RS, Fedyk ER, Springer TA, Mukaida N, Iglewski BH, Phipps RP. 2001. IL-8 production in human lung fibroblasts and epithelial cells activated by the Pseudomonas autoinducer N-3-oxododecanoyl homoserine lactone is transcriptionally regulated by NF-κB and activator protein-2. J Immunol 167:366–374. 10.4049/jimmunol.167.1.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mathesius U, Mulders S, Gao M, Teplitski M, Caetano-Anolles G, Rolfe BG, Bauer WD. 2003. Extensive and specific responses of a eukaryote to bacterial quorum-sensing signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:1444–1449. 10.1073/pnas.262672599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ranquet C, Toussaint A, de Jong H, Maenhaut-Michel G, Geiselmann J. 2005. Control of bacteriophage mu lysogenic repression. J Mol Biol 353:186–195. 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clark ME, He Q, He Z, Huang KH, Alm EJ, Wan XF, Hazen TC, Arkin AP, Wall JD, Zhou JZ, Fields MW. 2006. Temporal transcriptomic analysis as Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough transitions into stationary phase during electron donor depletion. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:5578–5588. 10.1128/AEM.00284-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ghosh D, Roy K, Williamson KE, Srinivasiah S, Wommack KE, Radosevich M. 2009. Acyl-homoserine lactones can induce virus production in lysogenic bacteria: an alternative paradigm for prophage induction. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:7142–7152. 10.1128/AEM.00950-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liang X, Wagner RE, Li B, Zhang N, Radosevich M. 2020. Quorum sensing signals alter in vitro soil virus abundance and bacterial community composition. Front Microbiol 11:1287. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van Houdt R, Aertsen A, Moons P, Vanoirbeek K, Michiels CW. 2006. N-Acyl-l-homoserine lactone signal interception by Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett 256:83–89. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rozanov DV, D’Ari R, Sineoky SP. 1998. RecA-independent pathways of lambdoid prophage induction in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 180:6306–6315. 10.1128/JB.180.23.6306-6315.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Laganenka L, Sander T, Lagonenko A, Chen Y, Link H, Sourjik V. 2019. Quorum sensing and metabolic state of the host control lysogeny-lysis switch of bacteriophage T1. mBio 10:e01884-19. 10.1128/mBio.01884-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rossmann FS, Racek T, Wobser D, Puchalka J, Rabener EM, Reiger M, Hendrickx APA, Diederich AK, Jung K, Klein C, Huebner J. 2015. Phage mediated dispersal of biofilm and distribution of bacterial virulence genes is induced by quorum sensing. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004653. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fernández-Piñar R, Cámara M, Dubern JF, Ramos JL, Espinosa-Urgel M. 2011. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa quinolone quorum sensing signal alters the multicellular behaviour of Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Res Microbiol 162:773–781. 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tan D, Hansen MF, de Carvalho LN, Røder HL, Burmølle M, Middelboe M, Svenningsen SL. 2020. High cell densities favor lysogeny: induction of an H20 prophage is repressed by quorum sensing and enhances biofilm formation in Vibrio anguillarum. ISME J 14:1731–1742. 10.1038/s41396-020-0641-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qin X, Sun Q, Yang B, Pan X, He Y, Yang H. 2017. Quorum sensing influences phage infection efficiency via affecting cell population and physiological state. J Basic Microbiol 57:162–170. 10.1002/jobm.201600510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shah M, Taylor V, Bona D, Tsao Y, Stanley SY, Elardo S, McCallum M, Bondy-Denomy J, Howell PL, Nodwell J, Davidson AR, Moraes T, Maxwell KL. 2020. A phage-encoded anti-activator inhibits quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. SSRN https://ssrn.com/abstract=3544401. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Hendrix H, Kogadeeva M, Zimmermann M, Sauer U, De Smet J, Muchez L, Lissens M, Staes I, Voet M, Wagemans J, Ceyssens PJ, Noben JP, Aertsen A, Lavigne R. 2019. Host metabolic reprogramming of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by phage-based quorum sensing modulation. bioRxiv 10.1101/577908. [DOI]

- 66.Blasdel BG, Ceyssens P-J, Chevallereau A, Debarbieux L, Lavigne R. 2018. Comparative transcriptomics reveals a conserved bacterial adaptive phage response (BAPR) to viral predation. bioRxiv 10.1101/248849. [DOI]

- 67.Bru JL, Rawson B, Trinh C, Whiteson K, Høyland-Kroghsbo NM, Siryaporn A. 2019. PQS produced by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa stress response repels swarms away from bacteriophage and antibiotics. J Bacteriol 201:e00383-19. 10.1128/JB.00383-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moreau P, Diggle SP, Friman VP. 2017. Bacterial cell-to-cell signaling promotes the evolution of resistance to parasitic bacteriophages. Ecol Evol 7:1936–1941. 10.1002/ece3.2818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Davies EV, James CE, Williams D, O’Brien S, Fothergill JL, Haldenby S, Paterson S, Winstanley C, Brockhurst MA. 2016. Temperate phages both mediate and drive adaptive evolution in pathogen biofilms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:8266–8271. 10.1073/pnas.1520056113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Papenfort K, Silpe JE, Schramma KR, Cong JP, Seyedsayamdost MR, Bassler BL. 2017. A Vibrio cholerae autoinducer-receptor pair that controls biofilm formation. Nat Chem Biol 13:551–557. 10.1038/nchembio.2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mayer MJ, Payne J, Gasson MJ, Narbad A. 2010. Genomic sequence and characterization of the virulent bacteriophage phiCTP1 from Clostridium tyrobutyricum and heterologous expression of its endolysin. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:5415–5422. 10.1128/AEM.00989-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Silpe JE, Bassler BL. 2019. Phage-encoded LuxR-type receptors responsive to host-produced bacterial quorum-sensing autoinducers. mBio 10:e00638-19. 10.1128/mBio.00638-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hargreaves KR, Kropinski AM, Clokie MR. 2014. What does the talking? Quorum sensing signalling genes discovered in a bacteriophage genome. PLoS One 9:e85131. 10.1371/journal.pone.0085131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Leblanc C, Caumont-Sarcos A, Comeau AM, Krisch HM. 2009. Isolation and genomic characterization of the first phage infecting Iodobacteria: ϕPLPE, a myovirus having a novel set of features. Environ Microbiol Rep 1:499–509. 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Perez-Pascual D, Monnet V, Gardan R. 2016. Bacterial cell-cell communication in the host via RRNPP peptide-binding regulators. Front Microbiol 7:706. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]