Zinc is an essential metal for numerous organisms, from humans to bacteria. The transportome of zinc uptake and efflux systems controls the overall cellular composition and zinc content in a double-feedback loop.

KEYWORDS: MerR, P-type ATPases, Zn

ABSTRACT

In the metallophilic betaproteobacterium Cupriavidus metallidurans, the plasmid-encoded Czc metal homeostasis system adjusts the periplasmic zinc, cobalt, and cadmium concentrations, which influences subsequent uptake of these metals into the cytoplasm. Behind this shield, the PIB2-type ATPase ZntA is responsible for removal of surplus cytoplasmic zinc ions, thereby providing a second level of defense against toxic zinc concentrations. ZntA is the counterpart to the Zur-regulated zinc uptake system ZupT and other import systems; however, the regulator of zntA expression was unknown. The chromid-encoded zntA gene is adjacent to the genes czcI2C2B2′, which are located on the cDNA strand and transcribed from a common promoter region. These genes encode homologs of plasmid pMOL30-encoded Czc components. Candidates for possible regulators of zntA were identified and subsequently tested: CzcI, CzcI2, and the MerR-type gene products of the locus tags Rmet_2302, Rmet_0102, and Rmet_3456. This led to the identification of Rmet_3456 as ZntR, the main regulator of zntA expression. Moreover, both CzcI proteins decreased Czc-mediated metal resistance, possibly to avoid “overexcretion” of periplasmic zinc ions, which could result in zinc starvation due to diminished zinc uptake into the cytoplasm. Rmet_2302 was identified as CadR, the regulator of the cadA gene for an important cadmium-exporting PIB2-type ATPase, which provides another system for removal of cytoplasmic zinc and cadmium. Rmet_0102 was not involved in regulation of the metal resistance systems examined here. Thus, ZntR forms a complex regulatory network with CadR, Zur, and the CzcI proteins. Moreover, these discriminating regulatory proteins assign the efflux systems to their particular function.

IMPORTANCE Zinc is an essential metal for numerous organisms, from humans to bacteria. The transportome of zinc uptake and efflux systems controls the overall cellular composition and zinc content in a double-feedback loop. Zinc starvation mediates, via the Zur regulator, upregulation of the zinc import capacity via the ZIP-type zinc importer ZupT and amplification of zinc storage capacity, which together raise the cellular zinc content again. On the other hand, an increasing zinc content leads to ZntR-mediated upregulation of the zinc efflux system ZntA, which decreases the zinc content. Together, the Zur regulon components and ZntR/ZntA balance the cellular zinc content under both high external zinc concentrations and zinc starvation conditions.

INTRODUCTION

The metallophilic betaproteobacterium Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34 (1, 2) thrives in environments containing mixtures of transition metals, such as auriferous soils and zinc deserts (3–5). It is able to tolerate zinc ion concentrations up to the maximum solubility of Zn(II) hydroxide at neutral pH values of 4.5 mM (6, 7) on solid, noncomplexing growth medium and also mixtures of the cations of the transition metals Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, and Cd, each in a unit ratio up to a concentration of 300 μM (8). At the same time, the numbers per cell of the essential cations of Fe, Zn, Cu, Ni, and Co remain constant, indicating an outstanding capacity for the homeostasis of multiple metal cations by this bacterium. Wild-type C. metallidurans CH34 contains the native plasmids pMOL28 and pMOL30 and a chromid as well as a chromosome. All four replicons have genes involved in zinc homeostasis (1, 9).

The optimal number of zinc atoms per cell is maintained by an interaction of the transportome (Fig. 1) with a network of extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors that control the homeostatic preferences for multiple metals (10) and additionally by cytoplasmic metal-binding and -buffering proteins (2, 11). The latter form a zinc repository composed of metal-binding sites in proteins and reflect the metalloproteome, in particular with regard to the role of ribosomal components and zinc chaperones. The zinc repository is able to accept and immediately bind incoming zinc ions and acts to buffer, discriminate, and deliver zinc (12, 13). The transportome is composed of at least nine divalent cation importers (8, 14–16) and several metal efflux systems, which together preserve the overall composition and concentration of transition metals in a kinetic homeostasis of uptake and efflux processes that leads to a controlled, and low, concentration of mobile zinc in the cytoplasmic metal pool (17, 18).

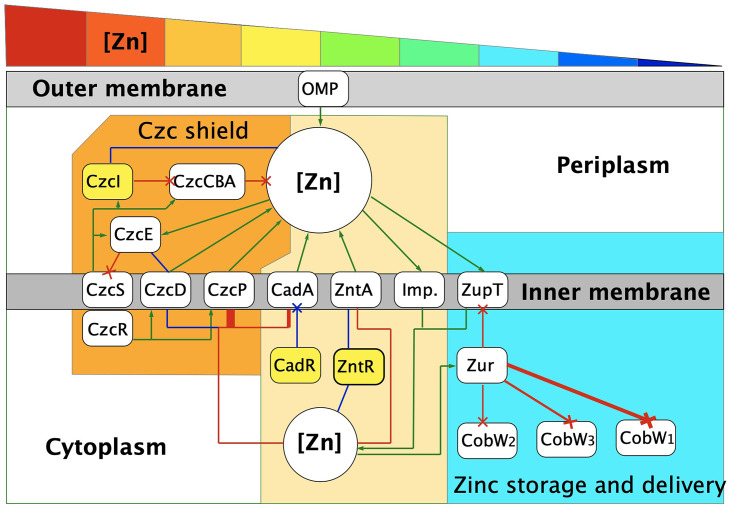

FIG 1.

Regulation of zinc homeostasis in C. metallidurans behind the shield of Czc. A regulatory scheme for zinc homeostasis in C. metallidurans is shown, including the newly identified regulatory functions of ZntR, CadR, and CzcI (yellow). The cellular compartments, including periplasm, cytoplasm, and outer and inner membrane are indicated, and at the top, a rainbow wedge illustrates decreasing external zinc concentrations from very high (lower millimolar [red]) to very low (mid-nanomolar [dark blue]). Red lines mean decreasing/inhibitory effects, green lines indicate increasing/activating effects, and blue indicates both, i.e., activation and repression. At high zinc concentrations, the plasmid-encoded Czc system regulates the periplasmic zinc pool, thereby shielding the cytoplasm. The CzcCBA tripartite efflux “gun” (orange field) efficiently removes surplus zinc from the periplasm, counteracting facilitated diffusion of zinc into the periplasm by outer membrane proteins (OMP). The inner membrane efflux systems CzcD and CzcP export surplus cytoplasmic zinc, feeding these ions into CzcCBA. The main regulator of czc is the two-component regulatory system CzcSR, but there are other regulatory circuits acting upon the system, such as a regulatory chain composed of CzcD and CzcE, and the newly identified quenching effect of CzcI. The components of the Zur regulon act at low zinc concentrations (light blue field), derepressing first the importer ZupT and the zinc chaperone CobW2, followed by CobW3 and last the CobW1 system. Between (tan field), the efflux pumps ZntA and CadA antagonize zinc import into the cytoplasm by ZupT and other importers (Imp.), and expression of these pumps is controlled by the MerR-type regulators ZntR and CadR, respectively. Details and references are in the introduction and in Discussion.

Metal efflux is organized on two levels in C. metallidurans CH34 (Fig. 1), which possesses the plasmid-borne czc resistance determinant on plasmid pMOL30 (19, 20). The first, basic level is mediated by PIB2-type ATPases (TC3.A.2) (21–23) and CDF (TC2.A.4) proteins of the inner membrane. Here, the PIB2-type ATPase ZntA is primarily responsible for zinc export across the inner membrane, with its homolog CadA serving as a second export system, especially for cadmium (24). Both exporters, however, have similar affinities for and transport rates of zinc and cadmium ions (24), leading to the question of how a particular efflux system is assigned to its cellular task. A second, enhanced zinc resistance level is achieved by additional plasmid-encoded exporters of the inner membrane, such as the PIB4-type ATPase CzcP and the CDF protein CzcD, plus export from the periplasm to the outside by the RND-type (TC2.A.6) CzcCBA protein complex (24, 25). Expression of the czc genes is controlled by the periplasmic metal ion concentration via the CzcRS two-component regulatory system (26–29). The Czc system adjusts the periplasmic zinc, cobalt, and cadmium ion concentrations, shielding the cytoplasm against high extracellular metal concentrations. Together with the efflux systems of the inner membrane, the uptake systems thus form a kinetic homeostasis that controls the cytoplasmic metal ion composition and content, which is buffered by the zinc repository (11). While CzcRS is involved in regulation of czc expression, the regulator of zntA expression was unknown.

In non-metal-amended Tris-buffered mineral salts medium (TMM) with 200 nM Zn(II), C. metallidurans contains approximately 70,000 Zn atoms per cell (zinc quota). The number increases to only 120,000 Zn atoms per cell even when 500 to 750 times (100 to 150 μM) more zinc chloride is added to the medium. The number of zinc ions per cell is kept constant by homeostatic systems to avoid toxic effects (30). In the absence of the plasmid-encoded Czc system in the plasmid-free C. metallidurans strain AE104, zinc efflux by ZntA and CadA becomes more important to maintain this number of zinc atoms per cell (24, 31). Without these efflux systems, the respective C. metallidurans mutant cells accumulate approximately 250,000 Zn atoms per cell at lower (micromolar) zinc concentrations in the growth medium and cease growth at higher concentrations, which defines the maximum number of zinc ions tolerated per cell. On the other hand, the minimum number of zinc ions required for survival seems to be around 20,000 per cell (8, 16). Thus, cellular zinc homeostasis keeps the number of cell-bound zinc ions within an order of magnitude at about half of the maximally tolerated value and maintains zinc homeostasis at environmental concentrations that vary between 200 nM to the maximum solubility of zinc hydroxide complexes of 4.5 mM behind a Czc shield (6, 7).

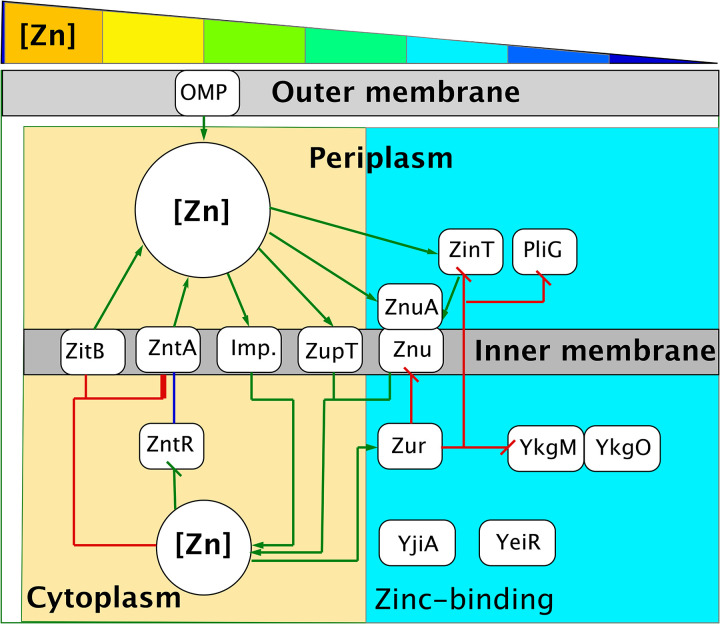

The transition metal transportome of Escherichia coli (Fig. 2) is simpler than that of C. metallidurans (32, 33). There is no Czc shield. As in C. metallidurans, zinc importers with low substrate specificity but a high import rate form the basic supply systems, but E. coli contains a lower number of these proteins than C. metallidurans. Examples of such proteins in E. coli include the metal-phosphate importer PitA (TC2.A.20), the magnesium importer CorA (TC1.A.35), the NRAMP MntH (TC2.A.55), and the ZIP protein ZupT (TC2.A.5) (33–36). The CDF protein ZitB serves as a constitutively expressed counterpart of the importers (37). If the zinc concentration drops below a certain threshold, the Fur-type regulator Zur derepresses synthesis of the ZnuABC importer (38–41) of the ABC family of transport systems (TC3.A.1). On the other hand, when the cytoplasmic zinc concentration exceeds a certain threshold, the MerR-type regulator ZntR induces gene expression and activates production of the PIB2-type ATPase ZntA (42). This system maintains the cytoplasmic zinc content of an E. coli cell at the optimal level (42), which is similar to that of C. metallidurans (8), probably by working together with a flow rate control of the transport systems (43).

FIG 2.

Regulation of zinc homeostasis in E. coli is much simpler. A regulatory scheme for zinc homeostasis in E. coli is shown. The cellular compartments, including periplasm, cytoplasm, and outer and inner membranes, are indicated, and at the top, a rainbow wedge illustrates decreasing external zinc concentrations from high (upper micromolar [orange]) to very low (mid-nanomolar [dark blue]), a smaller spectrum than that of C. metallidurans. Red lines mean decreasing/inhibitory effects, green lines show increasing/activating effects, and blue lines show both, i.e., activation and repression. The plasmid-encoded Czc system is absent, but instead, the Zur-controlled ZnuABC importer is present. There is only one CDF protein, ZitB, and the ZntR-controlled P-type ATPase ZntA. The components of the Zur regulon act at low zinc concentrations (light blue field), derepressing the ZnuABC importer but not ZupT. Two putative CobW-related zinc chaperones, YjiA and YeiR, are probably not under Zur control but are instead under the control of the putative ribosomal proteins YkgMO plus the periplasmic proteins PliG and ZinT (41). Further details and references are in the introduction and in Discussion.

Due to the important contribution of plasmid-borne genes to metal resistance in C. metallidurans wild-type strain CH34, its plasmid-free derivative AE104 exhibits a metal resistance level comparable to that of E. coli (6, 44). In contrast to E. coli, however, a ZnuABC homolog is absent in the metallophilic bacterium, and the Zur homolog of C. metallidurans controls zinc uptake by the ZIP-type zinc importer ZupT (8, 13, 16, 45). Zur-mediated upregulation of zupT increases zinc influx when Zur senses an insufficient cytoplasmic zinc concentration. The counterpart of the ZupT zinc importer is the PIB2-type ATPase ZntA (24), which is present at approximately 400 copies per AE104 cell grown in nonamended medium (12). The E. coli homologous zntA gene is expressed as a monocistronic RNA under the control of the MerR-type regulator ZntR (42, 46). In C. metallidurans, zntA is located as a single gene but is part of a divergon with the genes czcI2C2B2′ on the chromid. These genes encode homologs of the plasmid-encoded czc region. They represent the remains of an ancient zntA<>czcICBA region, which is still present in bacterial strains related to C. metallidurans (47, 48). During evolution of C. metallidurans, a functioning copy of this region appeared in plasmid pMOL30 and further genes were added, such as czcN upstream of czcI and czcDRSE downstream of czcA (26, 27, 49). Subsequently, the original region was interrupted through the activity of mobile elements within the czcB2 gene (50, 51). Both czc2 parts were separated into the gene clusters zntA<>czcI2C2B2′ and czcB2″A2 (or hmuB′A)<>czcS2R2-Rmet_4467 (47, 52), which are separate from each other on the chromid. The function of the czcI gene is still unknown, but it is a conserved part of the czcICBA core operon retained in all members of the Burkholderiaceae that harbor this gene locus (47).

ZntA is the counterpart of ZupT, and Zur controls zupT expression when zinc is at low concentrations. Which regulator is responsible for the upregulation of zntA at increased free zinc concentrations in the cytoplasm remains unresolved. After demonstrating that CzcI2, Rmet_0102, and Rmet_2301 (CadR) are not candidates, we identified in this study an early-branching homolog of the MerR tree (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), Rmet_3456, and reveal this to be ZntR, the regulator of zntA (Fig. 1).

RESULTS

Both CzcI proteins are involved in metal resistance.

The zntA gene is located adjacent to a divergently transcribed region czcI2C2B2′ (12, 15). The zntA and czcI2C2B2′ genes are coregulated by zinc availability (53). Since the plasmid-encoded CzcI has been annotated as a Czc inducer (29), the contribution of the chromid- and plasmid-encoded CzcI proteins to metal resistance was analyzed.

Zinc, cadmium, and cobalt resistance of the plasmid-free C. metallidurans strain AE104 and that of its ΔczcI2 mutant were identical on solid growth medium (Table 1). In liquid culture (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), however, the ΔczcI2 mutant displayed increased resistance to cadmium and cobalt but not to zinc. This indicated that CzcI2 was involved in metal homeostasis but was an unlikely candidate to be a regulator of zntA.

TABLE 1.

MICs for various C. metallidurans mutant strainsa

| Group and strain or mutation | MIC (mM) of: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| ZnCl2 | CdCl2 | CoCl2 | |

| AE104 mutants | |||

| Parent | 0.1 | 0.175 | 0.15 |

| ΔczcI2 | 0.1 | 0.175 | 0.15 |

| AE128 mutants | |||

| Parent | 7.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 |

| ΔczcI | 10.0 | 2.5 | 4.0 |

| ΔczcI2 | 7.0 | 2.0 | 5.0 |

| ΔczcI ΔczcI2 | 10.0 | 2.5 | 4.0 |

| CH34 mutants | |||

| Parent | 7.0 | 2.0 | 5.0 |

| ΔczcI | 10.0 | 2.5 | 6.0 |

| ΔczcI2 | 7.0 | 2.0 | 7.5 |

| ΔczcI ΔczcI2 | 10.0 | 2.5 | 7.5 |

Cells were streaked from a diluted liquid culture onto solid TMM and incubated for 5 days at 30°C. The MIC was the lowest concentration preventing the formation of colonies. Experiments included three biological replicates. Boldface indicates differences from the respective parent strain.

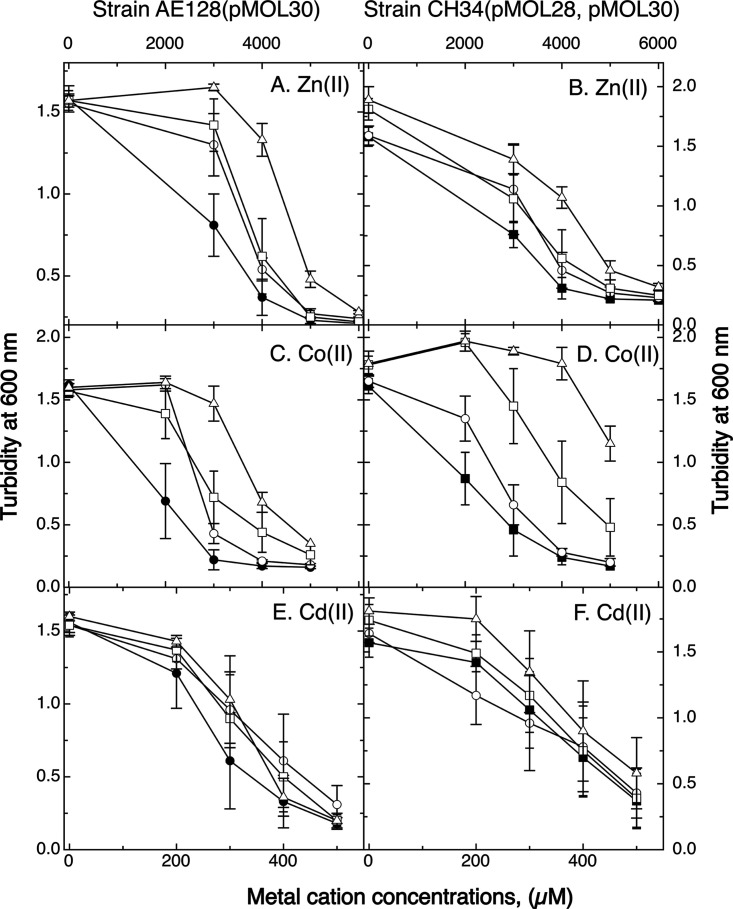

To learn more about the contributions of the CzcI proteins to metal resistance, czcI (Rmet_5983) on pMOL30, the chromid-borne czcI2 (Rmet_4595), or both genes were deleted in wild-type C. metallidurans CH34 and strain AE128. CH34 carries pMOL28 and pMOL30, and strain AE128 has pMOL30 only (6). Deletion of czcI from plasmid pMOL30, but not deletion of czcI2 from the chromid, increased zinc and cadmium resistance on solid medium (Table 1). Zinc and cadmium resistance of the double mutant was comparable to that of the ΔczcI single mutant. In liquid medium (Fig. 3), the double mutant displayed higher resistance to zinc than the parent, with both single mutants being on a similar intermediary level. There was little influence of either deletion on cadmium resistance, which is in agreement with the fact that the RND-driven CzcCBA system is more important for cadmium resistance on solid medium than in liquid culture (6, 24). CzcI decreased the level of zinc and cadmium resistance on solid medium. CzcI2 substituted for CzcI only in liquid medium with respect to zinc resistance.

FIG 3.

Metal resistance of CH34 and AE128 ΔczcI mutant strains. Dose-response of ΔczcI and ΔczcI2 mutants of strains AE128(pMOL30) (A, C, and E) and CH34(pMOL28, pMOL30) (B, D, and F) in the presence of increasing concentrations of zinc (A and B), cobalt (C and D), or cadmium (E and F). Solid symbols, parent strains; open circles, ΔczcI mutants; open squares, ΔczcI2 mutants; open triangles, double mutants. n = 3. Deviations are shown.

Single and double deletions of the czcI genes increased cobalt resistance on solid medium (Table 1) and in liquid culture (Fig. 3). The difference in cobalt resistance between the parent and double mutant strains (Fig. 3C and D) was greater than the differences in zinc resistance (Fig. 3A and B). In strain CH34, czcI2 contributed more than czcI. To analyze if CzcI2 interferes with CzcCBA, the czcCBAD′ fragment from plasmid pDNA130 (20) was cloned into plasmid pBBR1-MCS2 in the opposite orientation to the lacZp promoter to reduce the high-level constitutive expression of czcCBAD′ from an unknown promoter (17). The resulting plasmid pECD1092 was transferred into strain AE104 and its ΔczcI2 mutant (Fig. S3). The presence of plasmid pECD1092 increased zinc, cadmium, and cobalt resistance in both strains. In the ΔczcI2 mutant strain, zinc and cobalt resistance mediated by pECD1092 increased more than in the parent. This was not the case for cadmium resistance. This indicated that the CzcI proteins may decrease activity of the CzcCBA transenvelope efflux system, possibly to diminish excessive export of the essential periplasmic transition metals Co and Zn, which might lead to metal starvation (Fig. 1). In comparison, the CzcI proteins have a stronger impact on cobalt than on zinc homeostasis.

Influence of the CzcI proteins on expression of zntA and cadA.

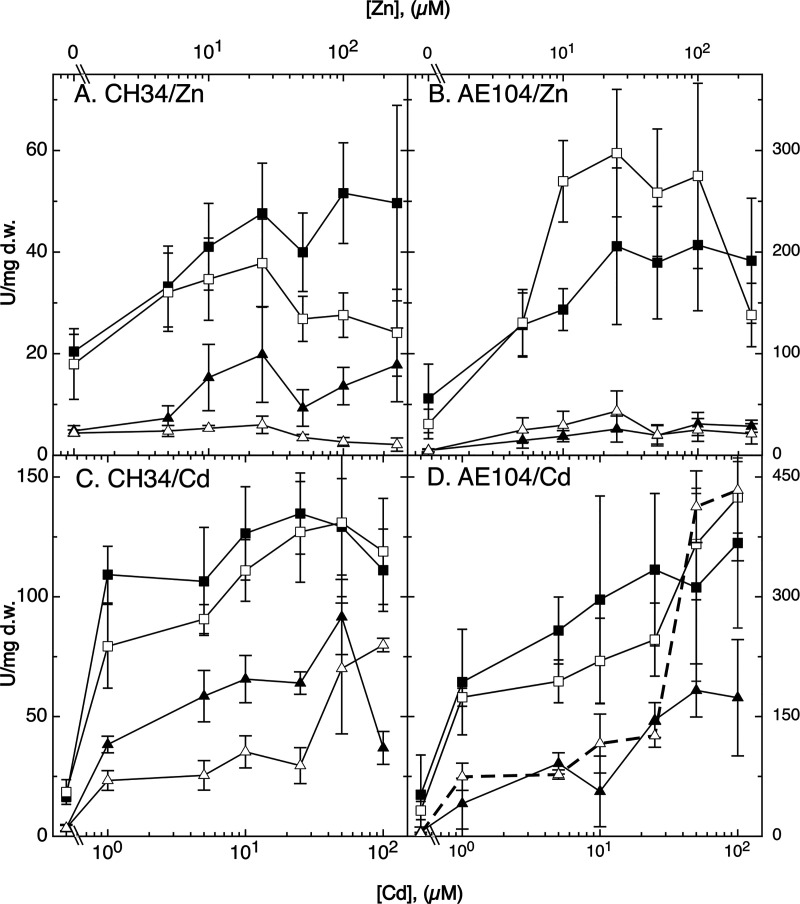

lacZ reporter gene fusions were inserted downstream of the genes encoding the efflux systems ZntA and CadA and the zinc importer ZupT in C. metallidurans strain CH34, its ΔczcI ΔczcI2 double mutant, the plasmid-free strain AE104, and the AE104 ΔczcI2 single mutant. Strain AE104 does not contain a native plasmid (pMOL28 or pMOL30); therefore, there is no czcI gene, so that a double mutant could not be constructed. In the presence of the czcI gene or genes (Fig. 4), (i) zntA and cadA were more strongly upregulated in strain AE104 lacking the czc system than in wild-type CH34; (ii) zntA-lacZ was more strongly expressed than cadA-lacZ; and (iii) while zntA was upregulated by cadmium and by zinc, cadA was more strongly upregulated by cadmium. The presence of Czc shielded the cytoplasm against surplus zinc and cadmium ions, while ZntA was the primary cytoplasmic efflux pump for both ions, and CadA served as an additional cadmium efflux pump and back-up zinc exporter. Results with other bacterial strain combinations similar to those obtained in these positive-control experiments were published before (24, 31).

FIG 4.

Influence of czcI alleles on metal-dependent upregulation of a zntA-lacZ and a cadA-lacZ reporter gene fusion. Derivatives of wild-type strain CH34 (A and C) and its plasmid-free derivative AE104 (B and D) were incubated in the presence of increasing zinc (A and B) and cadmium (C and D) concentrations, and the β-galactosidase activity was determined in units per milligram (dry mass) by the cuvette method. All panels show zntA-lacZ (closed squares) and cadA-lacZ (closed triangles) in the parent strain CH34 or AE104. Open symbols indicate the zntA-lacZ (squares) or cadA-lacZ fusion (triangles) in the CH34 ΔczcI ΔczcI2 double mutant or the AE104 ΔczcI2 single mutant. Strain AE104 does not contain a plasmid, and therefore no czcI gene is present. n = 3. Deviations are shown. In panel D, ΔczcI2 cadA-lacZ is shown with a dashed line for better visibility.

The absence of the CzcI proteins ameliorated zinc-dependent upregulation of zntA and cadA in strain CH34 (Fig. 4A) but not in strain AE104 (Fig. 4B). In strain AE104, CzcI2 influenced zinc-dependent upregulation of zntA-lacZ, but the difference in expression with and without CzcI2 was not significant for most points due to large standard deviations (Fig. 4B). In agreement with a possible role as a Czc “quencher,” loss of CzcI proteins may result in increased Czc activity, decreased import of zinc and cadmium ions into the cytoplasm, and consequently reduced upregulation of zntA and cadA.

The influence of the CzcI proteins on cadmium-dependent upregulation of zntA in strains CH34 and AE104 was not significant (Fig. 4C and D). Upregulation of cadA-lacZ in CH34 was again ameliorated by the presence of Czc but only at concentrations below 50 μM cadmium chloride (Fig. 4C). In strain AE104, CzcI2 had no effect on cadmium-dependent upregulation of cadA-lacZ up to 50 μM CdCl2, but interestingly, above this concentration (thick dashed line in Fig. 4D), cadA-lacZ was more strongly upregulated by cadmium in the ΔczcI2 mutant than in its parent. Other RND-type metal ion efflux systems which are not plasmid encoded may operate at a low level of activity in C. metallidurans (25, 54). Assuming that CzcI2 is also able to decrease the activity of these putative Czc paralogs, higher activity of the Czc paralogs due to a missing CzcI2 should result in a lower metal ion concentration in the periplasm, a lower rate of import into the cytoplasm, and upregulation of additional import systems to compensate for this lower import rate, as seen in mutants with multiple deletions in metal uptake systems (14, 15). This would lead to a lower selectivity of metal import, increased uptake of cadmium, and consequently upregulation of cadA.

Using zntA-lacZ and zupT-lacZ reporter fusions, the influence of both CzcI proteins on regulation of the zinc efflux systems and the zinc uptake system, respectively, under EDTA-induced metal starvation conditions was also tested (Fig. S4). In both tested strain backgrounds, CH34 and AE104, increasing EDTA concentrations resulted in downregulation of zntA and Zur-dependent upregulation of zupT, as expected (13, 45). No difference between the presence and absence of CzcI2 could be observed in strain AE104, while in CH34 the presence of the CzcI proteins led to a slight upregulation of zupT. This indicated that both CzcI proteins influenced metal homeostasis in C. metallidurans. They are involved in, but not required for, zinc- or cadmium-dependent upregulation of zntA or cadA (Fig. 4), possibly, but not exclusively, by interfering with the activity of the Czc system. Consequently, the periplasmic CzcI2 protein is not a transcriptional regulator of zntA expression. Since CzcI2 interferes with plasmid pBBR1-MCS2-encoded czcCBAD′ in the absence of the additional genes carried on the native plasmid pMOL30, CzcI2 also seems not to interact with other periplasmic Czc proteins such as CzcE or CzcJ or the histidine sensor kinase CzcS (24, 27). Instead, the CzcI proteins may interact directly with the CzcCBA and/or other RND-driven efflux complexes.

CadR (Rmet_2302) may regulate cadA but not zntA.

In E. coli, the MerR-type regulator ZntR regulates expression of zntA (42, 55, 56). In addition to the MerR mercury resistance regulators MerR1 to Mer4 (Rmet_2321, Rmet_5990, Rmet_6171, and Rmet_6344) and Rmet_0102 (annotated as SoxR2), ZntR from E. coli has two close homologs in C. metallidurans, PbrR and Rmet_2302 (Fig. S1). PbrR is part of the plasmid-encoded (pMOL30) lead resistance operon and regulates expression of the PIB2-type ATPase PbrA (57, 58). Since a zntA-lacZ fusion is also upregulated by zinc and cadmium in the plasmid-free strain AE104 (31), PbrR cannot be the main regulator of zntA, leaving Rmet_2302 as the candidate most closely related to ZntR from E. coli (Fig. S1). Rmet_2302 is located divergently with respect to the cadAC operon (10), encoding the PIB2-type ATPase CadA and the prolipoprotein signal peptidase-like (59) protein CadC, which contains a putative metal-binding motif HviDyiDfHiHgwH (metal-binding His and Asp residues are in capitals; other amino acids are in lowercase). Consequently, the rmet_2302 gene was deleted in strain AE104, and metal resistance was determined. Deletion of rmet_2302 did not decrease zinc resistance but increased cadmium resistance 1.8-fold, whereas cobalt resistance was unaffected (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

IC50s for various mutant strains of C. metallidurans strain AE104a

| Strain or mutation | IC50 (μM) of: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| ZnCl2 | CdCl2 | CoCl2 | |

| Parent | 70 ± 3 | 76 ± 3 | 123 ± 32 |

| ΔcadR | 63 ± 6 | 136 ± 8 | 130 ± 23 |

| ΔzntR | 43 ± 4 | 35 ± 6 | 134 ± 20 |

Dose-response curves were performed with the ΔcadR (ΔRmet_2302) and ΔzntR (ΔRmet_3456) mutants. n = 3 for all experiments. Values are means and deviations. Boldface indicates significant differences (D > 1). The experiments were performed with 5% inoculated main culture, and the optical density was measured after 24 h.

Reporter gene fusions zntA-lacZ and cadA-lacZ were constructed in the Δrmet_2302 deletion mutant, and regulation by zinc or cadmium was analyzed (Table 3). Moreover, rmet_2302 was cloned into the vector pBBR1-MSC3 (60), and the resulting plasmid, along with the empty vector as a control, was conjugated into the Δrmet_2302 deletion strain. The basic expression level of cadA-lacZ in TMM-grown cells was 19-fold lower than that of zntA-lacZ, corresponding to about 80 CadA and 400 ZntA copies per cell under these conditions (12) in the parent strain AE104. Since both fusions yielded similar maximum reporter activities of >200 U/mg when fully upregulated, cadA-lacZ was obviously more strongly repressed in TMM-grown cells than zntA-lacZ. The zntA-lacZ fusion was upregulated to a higher level in the presence of 200 μM Zn(II) than the cadA-lacZ fusion, but both fusions reached similar expression levels of about 200 U/mg in the presence of 50 μM Cd(II). Zinc was the main effector of zntA expression, while cadmium influenced expression of both genes.

TABLE 3.

β-Galactosidase activity of zntA- and cadA-lacZ fusionsa

| Fusion and strain or mutation | β-Galactosidase activity (U/mg [dry mass]) in TMM with: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| No addition | 200 μM Zn(II) | 50 μM Cd(II) | |

| Φ(cadA-lacZ) | |||

| AE104 | 1.23 ± 1.33 (1.00) | 24.3 ± 5.9 (19.8) | 259.8 ± 31.4 (211) |

| ΔcadR | 211.0 ± 37.4 (172) | 225.8 ± 48.7 (184) | 231.1 ± 23.7 (188) |

| ΔcadR vc | 193.5 ± 42.9 (157) | 245.3 ± 78.4 (199) | 200.8 ± 27.9 (163) |

| ΔcadR +cadR | 226.0 ± 50.5 (184) | 199.4 ± 53.7 (162) | 210.7 ± 29.5 (171) |

| ΔcadR +zntR | 227.7 ± 50.5 (185) | 180.7 ± 47.0 (147) | 201.3 ± 38.4 (164) |

| ΔzntR | 11.0 ± 4.5 (8.90) | 149.5 ± 21.4 (122) | 249.7 ± 70.2 (203) |

| ΔzntR vc | 9.8 ± 6.2 (7.97) | 79.1 ± 34.5 (64.3) | 235.0 ± 28.5 (191) |

| ΔzntR +zntR | 9.9 ± 8.2 (8.05) | 70.6 ± 33.0 (57.4) | 234.0 ± 47.7 (190) |

| ΔzntR +cadR | 6.4 ± 3.8 (5.20) | 107.9 ± 34.8 (87.9) | 240.1 ± 30.8 (195) |

| Φ(zntA-lacZ) | |||

| AE104 | 23.0 ± 8.4 (1.00) | 182.5 ± 44.1 (7.93) | 211.1 ± 16.6 (9.18) |

| ΔzntR | 0.1 ± 0.00 (0.01) | 0.5 ± 1.10 (0.02) | 8.5 ± 4.20 (0.37) |

| ΔzntR vc | 0.1 ± 0.00 (0.01) | 0.1 ± 0.00 (0.01) | 6.0 ± 4.80 (0.26) |

| ΔzntR +zntR | 14.2 ± 11.5 (0.62) | 57.8 ± 17.4 (2.51) | 51.5 ± 17.9 (2.24) |

| ΔzntR +cadR | 0.1 ± 0.10 (0.01) | 0.1 ± 0.10 (0.01) | 10.2 ± 5.50 (0.44) |

| ΔcadR | 2.2 ± 4.0 (0.10) | 170.8 ± 60.0 (7.43) | 171.5 ± 33.8 (7.46) |

| ΔcadR vc | 0.2 ± 0.1 (0.01) | 103.0 ± 45.1 (4.48) | 105.5 ± 43.9 (4.59) |

| ΔcadR +zntR | 0.2±.0.1 (0.01) | 93.5 ± 34.1 (4.07) | 143.2 ± 60.7 (6.23) |

| ΔcadR +cadR | 0.2 ± 0.1 (0.01) | 81.0 ± 16.9 (3.52) | 164.1 ± 56.5 (7.13) |

β-Galactosidase activity was determined by the 96-well plate method of the strains containing a cadA-lacZ or a zntA-lacZ fusion. vc, strain complemented in trans with a vector control; +zntR or +cadR, the same vector containing zntR (Rmet_3456) or cadR (Rmet_2302), respectively. Values are means and deviations from ≥3 experiments. Values in parentheses are the ratios of the respective value compared to parent strain AE104 without additions. Growth in the presence of 100 μM Co(II) had an effect only once, a 2.81-fold up-regulation from 0.05 ± 0.02 to 0.14 ± 0.02 U/mg in the ΔzntR strain. All other cobalt data did not yield any indication of a cobalt-dependent regulation and are not shown.

Deletion of rmet_2302 resulted in a constitutive expression level of the cadA-lacZ fusion of about 200 U/mg (Table 3). Expression of rmet_2302 in trans did not restore regulated expression of cadA-lacZ. Although the reason for this result could not be explained at this point, the lack of cadA regulation in Δrmet_2302 and the proximity of rmet_2302 to the cadA gene made it probable that Rmet_2302 is CadR.

When the metal content of the ΔcadR mutant was compared to that of the parent strain AE104 (Table 4), there was no difference between TMM-grown cells. When 1 μM Cd(II) was added, the cobalt content of the cells decreased in both strains by a factor of about 3, probably due to competitive inhibition of metal uptake. Under these conditions, ΔcadR cells contained 35,000 ± 2,400 Cd atoms per cell, 80% of the cadmium content of cells of the parent strain AE104, 44,000 ± 3,100 Cd atoms per cell (Table 4). This decreased cellular cadmium level corresponded to the increased expression level of cadA in ΔcadR cells (Table 3), indicating that the high-level expression of cadA-lacZ in the ΔcadR mutant was not an artifact resulting from the lacZ reporter fusion.

TABLE 4.

Metal content of AE104 and derivate strainsa

| Metal (atoms/cell) | Metal content (atoms/cell) in: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AE104 |

ΔzntR mutant |

ΔcadR mutant |

||||

| No addition | 1 μM Cd | No addition | 1 μM Cd | No addition | 1 μM Cd | |

| 106 × Mg | 14 ± 1.4 | 13 ± 1.2 | 12 ± 1.3 | 12 ± 0.8 | 14 ± 1.4 | 13 ± 1.8 |

| 103 × Fe | 910 ± 33 | 860 ± 62 | 910 ± 68 | 900 ± 77 | 910 ± 67 | 910 ± 110 |

| 103 × Zn | 70 ± 17 | 61 ± 7.7 | 65 ± 8.8 | 62 ± 6.2 | 67 ± 8.8 | 63 ± 6.1 |

| 103 × Co | 23 ± 6.3 | 8 ± 2.8 | 25 ± 5.4 | 7 ± 2.3 | 25 ± 5.4 | 4 ± 0.08 |

| 1 × Cd | 91 ± 27 | 44,000 ± 3,100 | 111 ± 8.4 | 57,000 ± 5,300 | 78 ± 15 | 35,000 ± 2,400 |

The cells from the precultures were diluted 100-fold into fresh TMM and incubated with shaking until the turbidity of the exponentially growing cells reached 100 Klett units. CdCl2 (1 μM) was added or not, and incubation was continued until the turbidity reached 150 Klett units. The AE104 parent, ΔcadR (ΔRmet_2302), and ΔzntR (ΔRmet_3456) cells were harvested by centrifugation, and the cellular metal content was determined by ICP-MS. Values are means and deviations for ≥3 experiments.

In the absence of cadR, zntA-lacZ could be upregulated by zinc and cadmium to a level similar to that of the parent strain (Table 3). Consequently, CadR was not required for regulation of zntA expression.

Rmet_0102 as a representative member of the MerR outgroup does not regulate zntA.

This left Rmet_0102 (Fig. S1) as a ZntREc-related MerR-type regulator with unknown function. Deletion of the gene did not influence zinc, cadmium, or oxidative stress resistance investigated with paraquat (Fig. S5) but increased cobalt resistance (Fig. S5C). Rmet_0102 was generated in E. coli and purified as a C-terminally streptavidin (Strep)-tagged protein. In electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) (Fig. S6), 50 pmol of recombinant Rmet_0102 protein clearly shifted its own but not the zntA promoter (zntAp). Since the tag did not inhibit the ability to bind its own promoter, this demonstrated that zntAp does not harbor a specific binding site for the recombinant Rmet_0102 protein. This protein is therefore not the regulator of zntA.

Rmet_3456 is ZntR.

Rmet_3456 is most closely related to a cluster of MerR-type proteins containing ZntR, MerR, CueR, and SoxR homologs (Fig. S1). Deletion of its gene decreased zinc and cadmium resistance of strain AE104 (Table 2).

Fusions of the lacZ reporter gene upstream of the zntA or the cadA gene were constructed in strain AE104 and the Δrmet_3456 deletion strain. Moreover, rmet_3456 was cloned into the vector pBBR1-MSC3 (60), and the resulting plasmid, along with the empty vector as a control, were conjugated into the Δrmet_3456 deletion strain.

Deletion of rmet_3456 abolished zinc-dependent upregulation of zntA-lacZ, and this effect could be complemented in trans with rmet_3456 but not cadR (Table 3). Rmet_3456 was thus renamed ZntR. Deletion of zntR led to a higher basic expression level of cadA-lacZ in the TMM-grown mutant than in parent cells, since zntA was not expressed and CadA had to substitute for ZntA. Despite this higher basic expression level, deletion of zntR did not influence zinc- or cadmium-dependent upregulation of cadA-lacZ. In contrast, deletion of cadR did not influence zinc- or cadmium-dependent upregulation of zntA-lacZ; thus, CadR should be primarily assigned to cadA, as ZntR can be to zntA (Table 3). Nevertheless, zntA-lacZ was upregulated by cadmium (but not zinc) to a level of 6 to 8 U/mg in the ΔzntR strain (Table 3), indicating the possibility of some cross talk, such that CadR may activate expression of zntA-lacZ to some degree, but only in the absence of ZntR.

The ΔzntR strain contained 30% more Cd atoms per cell than the parent strain when both strains were cultivated in the presence of 1 μM Cd(II) (Table 4). The presence of cadmium resulted in a strong upregulation of zntA and of cadA expression in AE104 parent cells (Table 3). Both genes were also upregulated in ΔzntA cells and cadA-lacZ expression reached the same specific β-galactosidase activity of about 250 U/mg as in the parent strain, but the activity of the zntA-lacZ expression was much lower in the mutant (8.5 U/mg) than the parent (211 U/mg). The sum of both specific activities of cadA-lacZ and zntA-lacZ was thus 471 U/mg in cadmium-induced parent cells but only 258 U/mg in the ΔzntR mutant, representing 55% of the parent level. This decreased total efflux power in the ΔzntR strain resulted in a higher cellular cadmium content, indicating that both P-type ATPases, ZntA and CadA, were needed for efficient removal of cadmium, even at a low concentration of 1 μM.

When the ΔzntR mutant was complemented in trans with zntR, the basic activity of zntA-lacZ was 60% of the parent cell level (Table 3) and reached 32% of the respective parent cell level in the presence of 200 μM Zn(II) and 24% in the presence of Cd(II). In the mutant cells, ZntR may not have reached protein levels comparable to those of the parent cells, for instance by lower expression of zntR in trans, transfer into inclusion bodies, or enhanced degradation. A similar but more pronounced problem with CadR may explain the negative complementation result with cadR in trans (Table 3).

ZntR binds specifically to the zntAp promoter.

ZntR was recombinantly produced in E. coli as a protein carrying an N-terminal Strep tag and purified (Fig. S7), while expression of cadR in E. coli always yielded CadR-containing inclusion bodies (M. Herzberg, unpublished data). The purified ZntR protein contained 0.43 ± 0 (n = 3) Zn atoms/polypeptide (inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry [ICP-MS] determination), or 1 Zn atom per dimer, and was designated holo-ZntR. Holo-ZntR was treated with EDTA and desalted, resulting in 0.14 ± 0 (n = 3) Zn atoms/polypeptide (ICP-MS determination). This form of the protein was designated apo-ZntR.

Both ZntR proteins were used in a mobility shift assay with three different fragments of the zntAp promoter region (Fig. 5; Fig. S8), corresponding to 367 bp directly upstream of zntA (fragment 1), 246 bp downstream of the zntA start codon (fragment 2, serving as a negative control), and fragment 3, which contains both regions (Fig. S8, top).

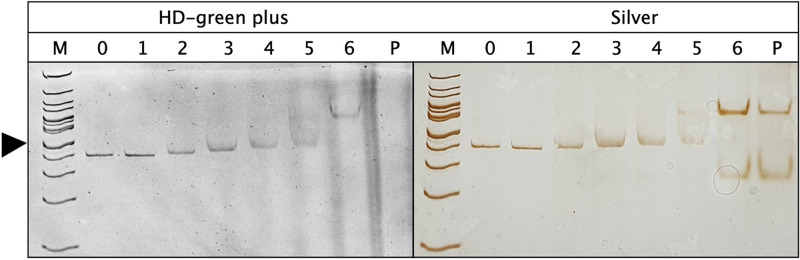

FIG 5.

EMSA comparing the binding of ZntR to the zntAp promoter region. The reaction volume of 15 μl contained 400 fmol of DNA fragment 1 (Fig. S8) of the zntAp promoter region plus a 10-fold (lane 1, 4 pmol)-, 125-fold (lane 2, 50 pmol)-, 250-fold (lane 3, 100 pmol)-, 375-fold (lane 4, 150 pmol)-, 500-fold (lane 5, 200 pmol)-, or 1,000-fold (lane 6, 400 pmol)-larger amount of holo-ZntR, no protein (lane 0), or only 200 pmol protein (lane P). The reaction mixture was applied to a 10% (wt/vol) native polyacrylamide gel and stained with HDGreen Plus, which stains the DNA only, or silver, which stains DNA and protein. Lane M, DNA size marker (100-bp ruler). The 500-bp position is labeled with an arrowhead. One of three representative gels with identical results is shown. Figure S8 shows results of another experiment, an experiment with apo-ZntR, the position of the DNA fragments, experiments with all three DNA fragments in the zntAp region with one fragment serving as a control, and an experiment with the cadAp DNA region.

Holo-ZntR formed two bands visible in the silver-stained gel (Fig. 5), probably corresponding to the ZntR monomer and dimer. While holo-ZntR was not able to bind DNA fragment 1 upstream of zntA at a 10-fold ratio of ZntR to DNA, the DNA band started to shift at a 125-fold ratio and continued to shift with increasing ratio (Fig. 5) until the shift was complete at a ratio of 1,000. This DNA-ZntR complex migrated at the same position as the ZntR dimer (Fig. 5) and started to appear at a 375-fold ratio. Probably, the fully shifted form represents a ZntR dimer, with the discrete band of the slightly shifted form being a monomer bound to the DNA fragment. Apo-ZntR was also able to form the fully shifted form (Fig. S8), but the slightly shifted bands at the 125- and 250-fold ratios were smears in the case of apo-ZntR, whereas they were discrete bands in the case of holo-ZntR. DNA fragment 2 downstream of the start codon of zntA was not shifted by holo-ZntR or by apo-ZntR (Fig. S8). In the case of DNA fragment 3, which contained the regions of DNA fragments 1 and 2, again, the discrete band of the slightly shifted form was visible at the 125-fold ratio in case of holo-ZntR, whereas apo-ZntR yielded a smear. The fully shifted form of the bound dimer was again visible at a ratio of 1,000 with holo-ZntR and apo-ZntR.

ZntR bound to the zntAp promoter region, probably as a dimer, in the absence and presence of zinc. A slightly shifted protein-DNA complex appearing at low protein-DNA ratios may represent a bound monomer.

Holo-ZntR did not bind to cadAp (Fig. S8), but apo-ZntR yielded a slightly shifted form, which may represent a monomer bound to the DNA. A fully shifted form of the dimer was visible neither with apo- nor with holo-ZntR. The cadA-lacZ reporter fusion (Table 3) and EMSA data (Fig. S8) did not clearly indicate at this stage if ZntR may be able to influence transcription initiation from cadAp in the absence of CadR.

Inverse and feedback control of expression of zupT and zntA.

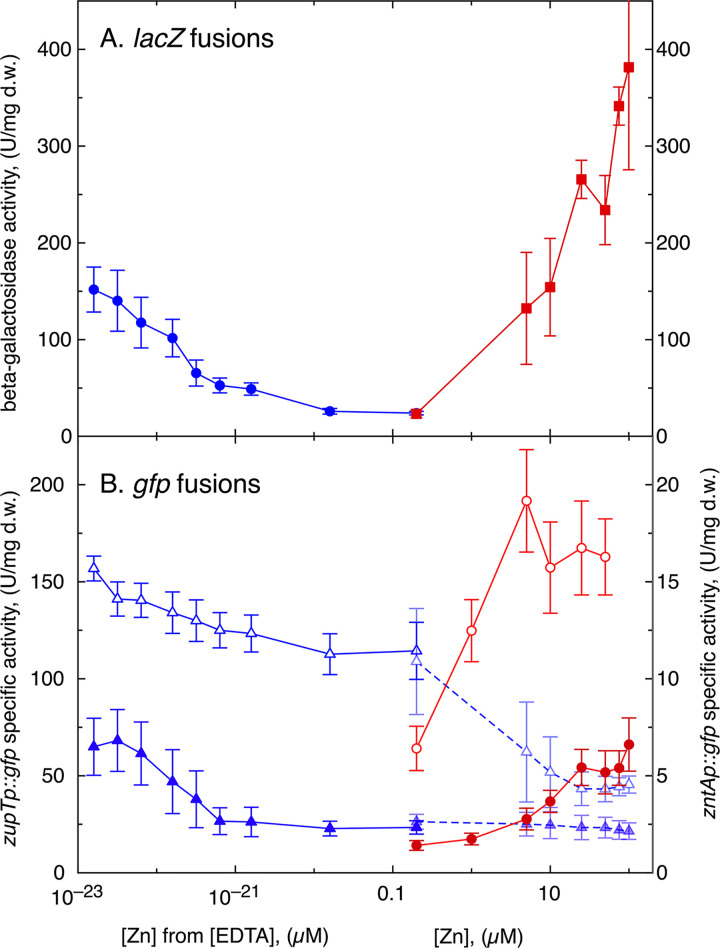

The promoters zupTp and zntAp were cloned into plasmid pBB1-MCS2 (60) upstream of a promoterless gfp gene, and the resulting constructs were transferred into C. metallidurans strain AE104 and its ΔzupT, Δe4 (ΔzntA ΔcadA ΔdmeF ΔfieF) (lacking known zinc efflux systems), Δe4 ΔzupT, and Δzur derivatives. These strains were incubated in the presence of increasing EDTA or zinc chloride concentrations, and the reporter activity was measured (Fig. S9). The activities of the zupTp::gfp fusion in strain AE104 and the ΔzupT mutant were also compared in more detail to that of a Φ(zupT-lacZ) fusion in AE104 under conditions of decreasing zinc availability (Fig. 6), which was calculated from the total zinc content of the medium of 200 nM (12) and the formation constant of Zn-EDTA complexes at pH 7 (61). Likewise, the reporter activities under increasing zinc concentrations of the zntAp::gfp fusion in strain AE104 and the Δe4 mutant (AE104 ΔzntA ΔcadA ΔdmeF ΔfieF) were compared to that of a corresponding Φ(zntA-lacZ) fusion in strain AE104 (Fig. 6). Both lacZ fusions were located downstream of the respective open reading frame, leaving the upstream gene intact. This demonstrated a similar increase of zupTp activity with decreasing zinc availability of the Φ(zupT-lacZ) fusion on the chromosome and the zupTp::gfp fusion in trans on a plasmid (Fig. 6). Moreover, a similar increase in zntAp activity was observed under both conditions but with increasing zinc concentrations. In TMM without added zinc or EDTA, which contains 200 nM zinc (12), the zupT-lacZ and zntA-lacZ fusions had nearly the same activity (Fig. 6). Upregulation of zupT and of zntA expression showed an inverse relationship with respect to zinc availability and started from a similar expression level of both genes when the cells were incubated in TMM without additions, which corresponds to 200 nM zinc (12).

FIG 6.

Inverse regulation of expression of zupT and zntA. (A) Fusions of zupT or zntA, which leave the respective gene intact, with the lacZ gene were constructed in C. metallidurans strain AE104. The Φ(zupT-lacZ) strain (circles) was incubated in the presence of increasing EDTA concentrations, the β-galactosidase activity determined and plotted against the “free” zinc concentration calculated by the formula [Zn]free = [Zn]total/(1 + K1[EDTA]) using a log10(K1app) value of 13.1 (61) and a [Zn]total value of 200 nM (12). The Φ(zntA-lacZ) strain (squares) was incubated in the presence of increasing zinc concentrations, and the result was plotted against the concentration of added zinc chloride. (B) To demonstrate the feedback loop in regulation of zupT and zntA, the promoter region of both genes was cloned upstream of a promoterless gfp gene on plasmid pBBR1-MCS2. The zupT::gfp fusion plasmid was transferred into strain AE104 (solid triangles) and its ΔzupT mutant (open triangles), the zntA::gfp fusion plasmid was transferred into strain AE104 (solid circles) and the Δe4 (ΔzntA ΔcadA ΔdmeF ΔfieF) mutant (open circles), and the specific fluorescence activity was measured. zupT::gfp activity is shown on the left axis, and zntA::gfp activity is on the right axis. The zupT::gfp activity with increasing zinc concentrations is shown with a dashed line and symbols with decreased opacity. A minimal of three biological replicates were performed, and standard deviations are shown.

In the absence of zupT, the zupTp::gfp activity was 5 times higher in TMM without addition than in the presence of zupT (Fig. 6B; Fig. S9A). Even though at least 9 additional transport systems exist that may be able to import zinc ions into the cell, these systems could not completely replace ZupT under “normal” (no added zinc) or zinc starvation conditions (14, 15). Interference of the zinc chaperone CobW3 with some of these other uptake systems is responsible for this effect (62). Adding zinc to ΔzupT cells with the zupTp::gfp fusion resulted in a downregulation of the reporter activity but not to the level observed for the same fusion in the AE104 parent (Fig. 6B). The other zinc import systems were now able to substitute for ZupT more effectively, yet not completely, even at 100 μM Zn(II).

The zupTp::gfp activity in the ΔzupT strain was even higher than that in a Δzur strain (Fig. S9A). Since deletion of zur results in a constitutively high-level expression of the genes in the Zur regulon (13, 62), the increased expression of zupTp::gfp in the ΔzupT mutant compared to the Δzur mutant indicated the presence of another, currently unknown regulatory circuit for zupT expression in the Δzur mutant. The zupTp::gfp activity in the Δe4 quadruple efflux mutant, which is not known to have a zinc efflux system, was similar to that of the AE104 parent strain under conditions of zinc deprivation, but zupTp::gfp activity was also elevated in the Δe4 ΔzupTp mutant at low zinc concentrations (Fig. S9). Even in the absence of zinc efflux systems, a missing ZupT could not be fully replaced by the remaining zinc uptake systems at zinc concentrations below 100 μM.

The zntAp::gfp activity was also upregulated in the Δe4 strain (Fig. 6). Activity increased strongly even at only 200 nM Zn(II) (Fig. S9B). The additional ΔzupT deletion in the Δe4 mutant had no effect on the zntAp::gfp activity, but introduction of the ΔzupT deletion into strain AE104 resulted in an elevated level of the zntAp::gfp activity up to 20 μM Zn(II) (Fig. S9B, inset), with the level in the Δzur strain being between these two (Fig. S9B). The absence of ZupT led to an imbalanced zinc import by the other uptake systems (14–16), and this situation had to be corrected by an elevated ZntA production.

A strong feedback control thus exists in the order cytoplasmic zinc > Zur > zupT expression > increased zinc import and cytoplasmic zinc > ZntR > zntA expression > increased zinc export in the absence of the Czc system, similar to what occurs in E. coli (Fig. 2). This control circuit appears central to the maintenance of cellular zinc homeostasis. Since zupT and zntA were expressed at a similar level in TMM-grown cells without any addition, a kinetic homeostasis of zinc uptake and export processes operates even in these cells cultivated without added metals, and the equilibrium was maintained by altering the expression levels of zupT and zntA when the external zinc concentration decreased or increased, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Zinc homeostasis behind the shield of the Czc system.

The zinc and cadmium efflux systems ZntA and CadA, and the Zur regulon components as their counterpart, act behind the shield of the plasmid-encoded Czc system in C. metallidurans wild-type strain CH34. This system mediates a high resistance level to zinc, cobalt, and cadmium (6, 19, 20, 63) and comprises several components. As a whole, Czc allows C. metallidurans to survive in metal-rich environments, such as auriferous soils or zinc deserts (3, 64, 65). The central component of the czcNICBADRSE gene cluster is the transenvelope protein complex CzcCBA with the powerful RND-HME pump, which exports surplus metals from the periplasm outside the cell (24). The CDF protein CzcD and the PIB4-type ATPase CzcP export mobile zinc ions (18) from the cytoplasm to the periplasm for further export by CzcCBA (24). CzcD, the two-component regulatory system CzcRS, and the periplasmic proteins CzcI, CzcE, and CzcJ support CzcCBA and are involved in regulation of czc gene expression (24, 27, 29, 49, 66). CzcI seems to quench activity of the CzcCBA efflux pump (Table 1; Fig. 3), assigning a role to this protein. The Czc system interacts with the ZntR/ZntA and CadR/CadA systems and the Zur regulon components, comprising the zinc importer ZupT and the zinc-binding GTPases CobW1, CobW2, and CobW3 (13, 62). With this multicomponent, multiple-metal resistance and homeostasis system (Fig. 1), which is much more complicated than that of E. coli (Fig. 2), C. metallidurans is able to thrive in its metal-rich environments.

High zinc concentrations.

The CzcI proteins encoded by pMOL30 and the chromid seem to be part of a regulatory network that synchronizes the enormous efflux power of the CzcCBA pumps with the demands of zinc and cobalt homeostasis (Fig. 1). Several factors are part of the periplasmic zinc homeostasis network: (i) the two-component system CzcRS, which mediates control of the promoters czcPp and czcNp by periplasmic metal cations (29); (ii) the CzcI proteins; (iii) CzcD, which is required to pass inducing metals to the periplasm (29, 49, 66); (iv) the periplasmic proteins CzcE (27) and perhaps CzcJ; (v) metal-binding sites in the membrane-fusion adapter protein CzcB, which may be involved in flux control of CzcCBA (25, 67, 68); and (vi) another metal-binding site adjacent to the cytoplasmic face of the proton channel of CzcA, which might also be involved in flux control by cytoplasmic zinc ions (69). With this strongly controlled large efflux power, Czc is able to mediate zinc resistance of C. metallidurans up to the maximum solubility of Zn(II) hydroxide complexes at neutral pH values (6, 7) of 4.5 mM. Auriferous soil can reach zinc contents corresponding to 1.4 mM in the presence of high concentrations of other transition metals (65), so that this efflux power seems to be needed for survival of C. metallidurans in its ecological niche. On the other hand, the bacterium is also able to maintain zinc homeostasis when only 200 nM zinc is present in the growth medium. This represents a homeostatic control over more than 4 orders of magnitude for zinc. Because CzcCBA also exports Co(II), the CzcI proteins might be required to decrease Czc-mediated “overpumping” of cobalt. Such a process would result in a decreased periplasmic cobalt concentration and consequently reduced import of the essential trace ion Co(II) into the cytoplasm.

Medium zinc concentrations.

The plasmid-free C. metallidurans strain AE104 is able to survive without the Czc system at zinc concentrations up to the upper micromolar range (6). Expression of the zntA efflux pump is upregulated when 200 nM to 100 μM zinc is present in the medium (Fig. 4 and 6). The cells fill up their zinc content during this concentration range from 70,000 to 120,000 Zn atoms/cell, while expression of zntA and other efflux systems maintains the zinc content at this level. Without the efflux systems, the cells contain more than 250,000 Zn atoms per cell at low-micromolar zinc concentrations, and cell toxicity stops growth (12).

ZntA and its paralog CadA are both PIB2-type ATPases, which transport zinc and cadmium with similar affinity and transport rates (24), indicating a substrate range including both metal cations. These two PIB2-type ATPases are assigned to their respective function by their MerR-type regulators ZntR and CadR. In this way, ZntA is present primarily at medium zinc concentrations (Fig. 6; Table 3), while CadA is additionally needed at medium cadmium concentrations (Tables 3 and 4). Export of the essential element zinc by CadA and ZntA should not be dangerous for the cells in the presence of high cadmium concentrations, because the high intracellular cadmium concentrations (Table 4) should competitively inhibit unwanted export of zinc. Moreover, the zinc repository and zinc chaperones sequester the essential metal, additionally preventing its export (12, 13, 62). In this way, the zinc homeostatic system at medium zinc concentrations mediated by ZntR/ZntA and the Zur regulon components is uncoupled from removal of the toxic-only cadmium ion, which is controlled by CadR/CadA. Nevertheless, the possibility of some cross talk between CadR/zntAp and ZntR/cadAp allows the possibility at the same time that ZntA and CadA may functionally substitute for each other, as has indeed been shown (24, 31).

These data assign clear roles in metal resistance to CadR (Rmet_2302) and ZntR (Rmet_3456). When the phylogenetic tree at the starting point of the investigation (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) was reassessed with other sequences of MerR-type proteins, but without the outlying MlrA and YcgE sequences (Fig. S10), ZntR, CadR, and PbrR from C. metallidurans clustered more closely together than before and displayed a typical CX34CX8/9C G/S metal-binding motif of zinc-cadmium-lead MerR-type regulatory proteins.

The structure of the PbrR dimer with bound lead ions (PDB code 5PGE) (Fig. S11) shows the metal bound by Cys78 of one protomer and Cys113/Cys122 of the other second protomer (70). CadR is very similar to PbrR in structure and primary sequence, but ZntR is different (Fig. S10 and S11). ZntR contains an additional C-terminal extension with the sequence CECHPRH, representing a zinc finger-like zinc-binding domain. It can be hypothesized at this stage that this particular motif is responsible for the zinc-specific upregulation of zntA by ZntR as a counterpart of the Zur-dependent upregulation of its regulon.

The phenotype of the ΔcadR mutant strain, constitutive expression of cadA, is unusual for a MerR-type regulator. ZntR from E. coli mediates zinc-responsive regulation of zntA and binds to a 20-bp spacer region between the −35 and −10 sites in the zntAp promoter. Binding of zinc to promoter-bound ZntR leads to a change in DNA conformation, which reduces the distance between the −35 and −10 sites and allows transcription initiation, as in other promoters regulated by MerR-type regulators (42, 56, 71). In C. metallidurans, preliminary transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq) data (D. H. Nies, unpublished data) indicate a σ70-dependent promoter upstream of cadA with 20 bp between the identified −35 and −10 sites. This cadAp promoter should be under the control of a MerR-type regulator and should not lead to high-level constitutive expression of cadA in a ΔcadR strain, because the −35 and the −10 sites are too far away from each other to allow efficient transcription initiation. Moreover, this transcriptional start site is 9 bp downstream of the AUG start codon of cadA, but a shorter version of the CadA protein that results from translation initiation at a start codon downstream of this transcriptional start site was not able to mediate cadmium resistance in E. coli (24). Further experiments are needed to resolve this enigmatic situation.

Low zinc concentrations.

In E. coli (Fig. 2), Zur acts on the expression for the Zn-importing ABC system znuABC, while ZntR acts on the respective zntA homolog (38, 39, 41, 42, 55, 56, 72). The zinc concentration window between 50% upregulation of znuABC and 50% upregulation of zntA is very narrow. While znuABC seems to be completely repressed when zntA is upregulated by 50%, zntA is completely repressed when znuABC is upregulated by half (55), while zupT is constitutively expressed in E. coli (35). In contrast (Fig. 1), Zur controls the gene for the ZIP protein ZupT in C. metallidurans, and two more PIB2-type ATPases exist, CadR-controlled CadA and PbrR-controlled PbrA (73), which are in addition to ZntR-controlled ZntA. The genes zupT and zntA were expressed at the same low level in cells grown in TMM containing only 200 nM zinc (Fig. 6). The cytoplasmic zinc content is constantly being adjusted by a kinetic homeostasis of export and import reactions, which is buffered by the zinc repository (12). Decreasing zinc efflux power at decreasing zinc concentrations and increasing zinc efflux power at increasing zinc concentrations in the medium by Zur and ZntR is used to maintain this equilibrium (Fig. 6). ZupT-mediated zinc import is always needed, even when the remaining zinc uptake systems manage to import sufficient zinc (14, 15), because zinc imported by ZupT is more efficiently allocated to zinc-dependent proteins, such as the RpoC subunit of the RNA polymerase (16). Figure 6B clearly shows the importance of ZupT compared to all other zinc uptake systems, highlighted by the strong Zur-dependent transcription of the zupTp::gfp fusion in the ΔzupT mutant cell: without ZupT, the cytoplasm does not contain sufficient mobile zinc to bind to Zur and repress this promoter. When CzcCBA keeps the periplasmic zinc concentration low, only ZupT is able to import sufficient amounts of zinc into the cytoplasm, explaining why there is a strong and rapid selection for czc-free mutants of a ΔzupT strain (16).

Conclusion.

This study illustrates the central role of ZntA in regulating cellular zinc homeostasis in C. metallidurans. It acts together with the Czc shield and reveals the complex and interwoven nature of the zinc-dependent control of the MerR-regulated efflux and the Zur-controlled zinc uptake, storage, and delivery systems (Fig. 1). This network is also used for cadmium resistance due to the higher affinity (24) of the inner membrane efflux systems CadA and ZntA for cadmium than for zinc ions. These finely tuned systems allow the cells to cope with a broad range of zinc concentrations, ranging from nearly no available zinc to excessively high zinc concentrations. At increasing zinc concentrations, zntA expression is controlled by the activator ZntR, followed by upregulation of cadA by CadR. At even higher levels, upregulation of czc leads to increased export of cytoplasmic zinc by CzcP and CzcD, followed by further export to the outside by CzcCBA. Finally, at the highest concentrations, C. metallidurans may be able to precipitate zinc carbonate by a reaction catalyzed by an unknown plasmid-encoded factor (8, 17, 74).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Plasmids and C. metallidurans strains (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) used in this study were all derivatives of the wild-type strain CH34 and the plasmid-free strain AE104, which lacks pMOL28 and pMOL30 (6). Tris-buffered mineral salts medium (6) containing 2 g sodium gluconate/liter (TMM) was used to cultivate these strains aerobically with shaking at 30°C. Analytical-grade salts of heavy metal chlorides were used to prepare 1 M stock solutions, which were sterilized by filtration. Solid Tris-buffered medium contained 20 g agar/liter.

MIC.

The MIC was determined in triplicate as the lowest concentration inhibiting bacterial growth on solid TMM. A preculture was incubated at 30°C and 250 rpm for 30 h and then diluted 1:20 into fresh medium, and incubation was continued for 24 h at 30°C and 250 rpm. This 24-h culture was diluted 1:100 into fresh medium and used for streaking onto plates containing different concentration of the respective metal salts. The plates were incubated at 30°C for 5 days, and cell growth was monitored.

Dose-response growth curves in tubes.

Growth curves for C. metallidurans were conducted in TMM. A preculture was incubated at 30°C and 250 rpm for 30 h, diluted 1:20 in fresh medium, incubated for 24 h at 30°C and 250 rpm, and then diluted in parallel 1:10 into fresh medium containing increasing metal concentrations. Cells were cultivated for 20 h at 30°C and 250 rpm, and the optical density was determined at 600 nm. To calculate the IC50 (50% inhibitory concentration, i.e., metal concentration that led to turbidity reduction by half) and the corresponding b value (measure of the slope of the sigmoidal dose-response curve), the data were adapted to the formula OD(c) = OD0/{1 + exp[(c − IC50)/b]}, which is a Hill-type equation introduced by Pace and Scholtz (75) and later simplified (76). OD(c) is the optical density (turbidity) at metal concentration c, and OD0 reflects no added metal.

Dose-response growth curves in 96-well plates were also conducted in TMM.

A preculture was incubated at 30°C and 200 rpm up to early stationary phase, then diluted 1:20 into fresh medium, and incubated for 24 h at 30°C and 200 rpm. Overnight cultures were used to inoculate parallel cultures with increasing metal concentrations in 96-well plates (Greiner). Cells were cultivated for 24 h at 30°C and 1,300 rpm in a neoLab DTS-2 shaker (neoLab, Heidelberg, Germany), and the optical density was determined at 600 nm in a Tecan Infinite 200 Pro reader (Tecan Group Ltd., Männedorf, Switzerland).

β-Galactosidase assay and lacZ reporter constructions.

The lacZ reporter gene was inserted downstream of several target genes to construct reporter operon fusions. This was done by single-crossover recombination in C. metallidurans strains. A 300- to 400-bp PCR product of the 3′-end region of the respective target gene was amplified from total DNA of strain CH34, and the resulting fragments were cloned into plasmid pECD794 (pLO2-lacZ) (24). The respective operon fusion cassettes were inserted into the open reading frame of the target gene by conjugation and single-crossover recombination. C. metallidurans cells with a lacZ reporter gene fusion were cultivated as a preculture in TMM containing 1 g liter−1 kanamycin at 30°C and 250 rpm for 30 h, diluted 20-fold into fresh medium, incubated with shaking at 30°C for 24 h, diluted 50-fold into fresh medium, and incubated with shaking at 30°C until a cell density of 100 Klett units was reached. This culture was distributed into sterile 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-One, Frickenhausen, Germany). After addition of metal salts, incubation in the 96-well plates was continued for 3 h at 30°C in a neoLab DTS-2 shaker (neoLab Migge Laborbedarf, Heidelberg, Germany). The turbidity at 600 nm was determined in a Tecan Infinite 200 Pro reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland), and the cells were sedimented by centrifugation at 4°C for 30 min at 4,500 × g. The supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellets were frozen at −20°C.

For the enzyme assay, the pellet was suspended in 190 μl Z buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.5 M β-mercaptoethanol), and 10 μl permeabilization buffer was added (6.9 mM CTAB [cetyltrimethylammonium bromide], 12 mM sodium deoxycholate). The suspension was incubated with shaking at 30°C, and 20 μl ONPG solution (13.3 mM ortho-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside in Z buffer without β-mercaptoethanol) was added. Incubation was continued with shaking in a neoLab DTS-2 shaker at 30°C until the yellow color of o-nitrophenol was clearly visible and stopped by addition of 50 μl 1 M Na2CO3. The extinction at 420 nm and 550 nm was measured in a Tecan Infinite 200 Pro reader. The activity was determined as described previously (66) with a factor of 315.8 μM, calculated from the path length of the 96-well plate and the extinction coefficient of o-nitrophenol: activity = 315.8 μM × [E420 − (1.75 × E550)]/reaction time; specific activity is activity divided by the cellular dry mass (66).

The activities of the cadA-lacZ and zntA-lacZ fusions were calculated from the time-dependent increase in the extension at 420 nm. After incubation in the presence of the respective metal concentrations in 96-well plates, the cells were harvested and suspended as described above. After incubation for 5 min at 30°C, the ONPG solution was added by an injector (Tecan Spark). The plates were incubated with shaking at 30°C, and the extinction at 420 nm was measured at intervals of 1 min for 10 min. Subsequently, the slope of this increase was determined and used to calculate the activity (in units) as 342 μM multiplied by the slope (per minute). The value of 342 μM resulted from the path length of the 96-well plates and the extinction coefficient of o-nitrophenol as described above. The specific activity was the quotient of activity and cell mass (66).

Fluorescence assay and gfp reporter plasmid constructions (53).

C. metallidurans cells with a gfp reporter gene promoter fusion plasmid were cultivated as precultures in TMM containing 1 g liter−1 kanamycin at 30°C and 250 rpm overnight to reach the early stationary phase of growth, diluted to 5% in a second preculture at 30°C and 250 rpm for 24 h, then diluted to 2% in fresh medium, and incubated with shaking at 30°C. At a cell density of 100 Klett units, metal salts or EDTA was added to different final concentrations, and cells were incubated with shaking for 18 h at 30°C and 1,300 rpm in a neoLab DTS-2 shaker (neoLab, Heidelberg, Germany).

The specific GFP fluorescence was calculated in nanomoles per microgram (dry weight) by using an extinction coefficient (EGFP) at 488 nm of 42,000 liters mol−1 cm−1, using the depth of the well as layer thickness of the well and ratio of culture volume to the volume of the reaction mixture. Measurement of the emission wavelength at 518 nm was performed according to excitation at 488 nm and optical density at 600 nm using a Tecan Infinite 200 reader (Tecan Group Ltd., Männedorf, Switzerland). The dry weight per volume was calculated from the turbidity measurements, using a calibration curve.

The gfp reporter gene was amplified (primers GFP13 KpnI [5′-AAAGGTACCATACATATGGCTAGCAAAG-3′] and GFP13 NsiI [5′-TTAATGCATAGTGCTCGAATTCATTATTT-3′]) from the source plasmid pMUTIN-GFP+ (77) and inserted into pBBR1-MSC2 (60) after digestion (NsiI/KpnI) to construct the reporter plasmid. A 100- to 150-bp PCR product of the promoter region of the target genes was amplified from total DNA of strain CH34 or AE104 (primers zupTp HindIII [5′-AAAAAGCTTCTGCGCTGGCCGCTTCTTC-3′], zupTp KpnI [5′-AAAGGTACCCGATTAACGCAACAATGTTGC-3′], zntAp KpnI [5′-GGTACCTGATTCTTGTTCCCTGCCATTG-3′], and zntAp SpeI [5′-ACTAGTGCCCAGGCGAACTGGAG-3′]), and the resulting fragments were cloned after digestion (KpnI and SpeI) into plasmid pBBR1-MSC2Φgfp+. The zupT promoter region had been subcloned in pGEM T-Easy (Promega) prior to this step, and the resulting plasmids were named pBBR1-MCS2 Ω(zupTpromoter+::gfp+) and pBBR1-MCS2 Ω(zntApromoter+::gfp+).

Genetic techniques.

Standard molecular genetic techniques were used (19, 78). For conjugative gene transfer, overnight cultures of donor strain E. coli S17/1 (79) and of the C. metallidurans recipient strains grown at 30°C in Tris-buffered medium were mixed (1:1) and plated onto nutrient broth agar. After 2 days, the bacteria were suspended in TMM, diluted, and plated onto selective media as previously described (19).

Primer sequences are provided in Table S1. Plasmid pECD1002, a derivate of plasmid pCM184 (80), was used to construct deletion mutants. These plasmids harbor a kanamycin resistance cassette flanked by loxP recognition sites. Plasmid pECD1002 additionally carries alterations of 5 bp at each loxP site. Using these mutant lox sequences, multiple gene deletions within the same genome are possible without interference by secondary recombination events (81, 82). Fragments of 300 bp upstream and downstream of the target gene were amplified by PCR, cloned into the vector pGEM T-Easy (Promega), sequenced, and further cloned into plasmid pECD1002. The resulting plasmids were used in a double-crossover recombination in C. metallidurans strains to replace the respective target gene with the kanamycin resistance cassette, which was subsequently also deleted by transient introduction of the cre expression plasmid pCM157 (80). Cre recombinase is a site-specific recombinase from the phage P1 that catalyzes the in vivo excision of the kanamycin resistance cassette at the loxP recognition sites. The correct deletions of the respective transporter genes were verified by Southern DNA-DNA hybridization. For construction of multiple deletion strains, these steps were repeated. The resulting mutants carried a small open reading frame instead of the wild-type gene to prevent polar effects.

Gene insertions.

For reporter operon fusions, lacZ was inserted downstream of several targets. This was done without interrupting any open reading frame downstream of the target genes to prevent polar effects. The 300- to 400-bp 3′ ends of the respective target genes were amplified by PCR from total DNA of strain AE104, and the resulting fragments were cloned into plasmid pECD794 (pLO2-lacZ) (83). The respective operon fusion cassettes were inserted into the open reading frame of the target gene by single-crossover recombination.

Purification of Strep-tagged proteins.

The rmet_0102 and rmet_0345 genes were amplified by PCR using genomic DNA from strain AE104 as the template with primers listed in Table S1. Amplified DNA fragments were cloned into vector pASK-IBA3+ or 7+. E. coli strain BL21-pLysS (Promega) transformed with the specific plasmid was cultivated in LB medium with shaking at 37°C until an optical density of 0.8 at 600 nm was attained. Expression was induced by adding 200 μg anhydrotetracycline (AHT) per liter, and incubation was continued for 3 h at 30°C or 37°C.

Cells were harvested by centrifugation and disrupted by ultrasonication. After low-speed centrifugation to remove cell debris, the recombinant proteins were purified using a Strep-tactin affinity chromatography column according to the manufacturer’s protocol (IBA GmbH). The recombinant protein was concentrated by using Vivaspin 20 columns (10,000 molecular weight cutoff [MWCO]; polyethersulfone [PES] membrane; Sartorius Stedim Biotech, Göttingen, Germany). Buffer exchanges were performed by dialysis (ZellusTrans V Serie, 10,000 MWCO; Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) overnight against a 100-fold volume of protein solution with the new buffer or using a PD-10 column (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany). The protein concentration was determined by using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) or by using the NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (extinction coefficient for ZntR-Nstrep [ε280] = 11,960 M−1 cm−1; Rmet_0102-Cstrep ε280 = 11,460 M−1 cm−1; both were calculated using the ProtParam tool of the ExPASy server [http://web.expasy.org/protparam/]). Protein quality was analyzed using a 12.5% (wt/vol) SDS gel stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (84) or by silver staining (85). Fixation was performed in 50% (vol/vol) acetone, 1.25% (wt/vol) trichloroacetic acid, and 0.01% (vol/vol) formaldehyde for at least 1 h. Gels were washed for 1 min in 50% (vol/vol) ethanol and sensitized with 1.6 mM Na2S2O3 for 2 min, and impregnation with 11.77 mM AgNO3 and 0.185% (vol/vol) formaldehyde for 20 min followed. Developing solution contained 0.026% (vol/vol) formaldehyde, 0.566 M Na2CO3, and 63.25 μM Na2S2O3. Reactions were stopped with 50% (vol/vol) methanol and 12% (vol/vol) acetic acid.

EMSA.

Gel retardation assays were performed as described previously (27) with modifications. PCR products together with purified recombinant proteins were used. Approximately 0.2 pmol of the rmet_0102, cadAp, and zntAp promoter fragment and various concentrations of the recombinant proteins were used for each assay. The DNA-protein complex was formed at 30°C for 40 min in 30 μl binding buffer (50 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.8], 5% glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]). The reaction mixtures were cooled on ice and applied to a 10% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide (PAA) gel with a running buffer containing 1× native buffer (100 mM Tris, 100 mM glycine; pH 8.6). The gel was run at 4°C and 60 V for 1 to 2 h, stained with HDGreen Plus (Intas, Göttingen, Germany) or silver, dried, and densitometrically scanned.

ICP-MS.

For ICP-MS analysis, HNO3 (trace metal grade; Normatom/ProLabo) was added to the samples to a final concentration of 67% (wt/vol), and the mixture was mineralized at 70°C for 2 h. Samples were diluted to a final concentration of 2% (wt/vol) nitric acid and 0.1 mg/ml of Strep-Zur. Indium and germanium were added as internal standards at a final concentration of 10 ppb each. Elemental analysis was performed via ICP-MS using a Cetac ASX-560 sampler (Teledyne, Cetac Technologies, Omaha, NE), a MicroFlow PFA-200 nebulizer (Elemental Scientific, Mainz, Germany), and an ICAP-TQ ICP-MS instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) operating with a collision cell and flow rates of 4.8 ml min−1 of He/H2 (93%/7%), with an Ar carrier flow rate of 0.76 liter min−1 and an Ar makeup flow rate of 15 liters min−1. An external calibration curve was recorded with ICP-multielement standard solution XVI (Merck) in 2% (vol/vol) nitric acid. The sample was introduced via a peristaltic pump and analyzed for its metal content. For blank measurement and quality/quantity thresholds, calculations based on DIN32645 TMM were used. The results were calculated from the parts-per-billion data as moles of metal per mole of protein or per cell, as described elsewhere (8).

Statistics.

Student’s t test was used, but in most cases the distance (D) value, D, has been used several times previously for such analyses (15, 53, 86). It is a simple, more useful value than Student’s t test because nonintersecting deviation bars of two values (D > 1) for three repeats always means a statistically relevant (≥95%) difference provided that the deviations are within a similar range. At an n value of 4, significance is ≥97.5%, at an n value of 5, it is ≥99% (significant), and at an n value of 8, it is ≥99.9% (highly significant).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for this work was provided by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Ni262/19).

We thank Grit Schleuder for skillful technical assistance and Gary Sawers for critically reading the manuscript. Frank Hille and Robert Klassen performed the zupT-lacZ and zntA-lacZ measurements shown in Fig. 5A as part of their lab rotation; Gregoire Henry performed the zntA-gfp measurements.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Janssen PJ, Van Houdt R, Moors H, Monsieurs P, Morin N, Michaux A, Benotmane MA, Leys N, Vallaeys T, Lapidus A, Monchy S, Medigue C, Taghavi S, McCorkle S, Dunn J, van der Lelie D, Mergeay M. 2010. The complete genome sequence of Cupriavidus metallidurans strain CH34, a master survivalist in harsh and anthropogenic environments. PLoS One 5:e10433. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nies DH. 2016. The biological chemistry of the transition metal “transportome” of Cupriavidus metallidurans. Metallomics 8:481–507. 10.1039/c5mt00320b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diels L, Mergeay M. 1990. DNA probe-mediated detection of resistant bacteria from soils highy polluted by heavy metals. Appl Environ Microbiol 56:1485–1491. 10.1128/AEM.56.5.1485-1491.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goris J, De Vos P, Coenye T, Hoste B, Janssens D, Brim H, Diels L, Mergeay M, Kersters K, Vandamme P. 2001. Classification of metal-resistant bacteria from industrial biotopes as Ralstonia campinensis sp. nov., Ralstonia metallidurans sp. nov. and Ralstonia basilensis Steinle et al. 1998 emend. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 51:1773–1782. 10.1099/00207713-51-5-1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reith F, Rogers SL, McPhail DC, Webb D. 2006. Biomineralization of gold: biofilms on bacterioform gold. Science 313:233–236. 10.1126/science.1125878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mergeay M, Nies D, Schlegel HG, Gerits J, Charles P, van Gijsegem F. 1985. Alcaligenes eutrophus CH34 is a facultative chemolithotroph with plasmid-bound resistance to heavy metals. J Bacteriol 162:328–334. 10.1128/JB.162.1.328-334.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weast RC. 1984. CRC handbook of chemistry and physics, 64th ed. CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirsten A, Herzberg M, Voigt A, Seravalli J, Grass G, Scherer J, Nies DH. 2011. Contributions of five secondary metal uptake systems to metal homeostasis of Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34. J Bacteriol 193:4652–4663. 10.1128/JB.05293-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dicenzo GC, Finan TM. 2017. The divided bacterial genome: structure, function, and evolution. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 81:e00019-17. 10.1128/MMBR.00019-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Große C, Poehlein A, Blank K, Schwarzenberger C, Schleuder G, Herzberg M, Nies DH. 2019. The third pillar of metal homeostasis in Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34: preferences are controlled by extracytoplasmic functions sigma factors. Metallomics 11:291–316. 10.1039/c8mt00299a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colvin RA, Holmes WR, Fontaine CP, Maret W. 2010. Cytosolic zinc buffering and muffling: their role in intracellular zinc homeostasis. Metallomics 2:306–317. 10.1039/b926662c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herzberg M, Dobritzsch D, Helm S, Baginsky S, Nies DH. 2014. The zinc repository of Cupriavidus metallidurans. Metallomics 6:2157–2165. 10.1039/c4mt00171k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bütof L, Schmidt-Vogler C, Herzberg M, Große C, Nies DH. 2017. The components of the unique Zur regulon of Cupriavidus metallidurans mediate cytoplasmic zinc handling. J Bacteriol 199:e00372-17. 10.1128/JB.00372-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herzberg M, Bauer L, Kirsten A, Nies DH. 2016. Interplay between seven secondary metal transport systems is required for full metal resistance of Cupriavidus metallidurans. Metallomics 8:313–326. 10.1039/C5MT00295H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Große C, Herzberg M, Schüttau M, Wiesemann N, Hause G, Nies DH. 2016. Characterization of the Δ7 mutant of Cupriavidus metallidurans with deletions of seven secondary metal uptake systems. mSystems 1:e00004-16. 10.1128/mSystems.00004-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herzberg M, Bauer L, Nies DH. 2014. Deletion of the zupT gene for a zinc importer influences zinc pools in Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34. Metallomics 6:421–436. 10.1039/c3mt00267e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Legatzki A, Franke S, Lucke S, Hoffmann T, Anton A, Neumann D, Nies DH. 2003. First step towards a quantitative model describing Czc-mediated heavy metal resistance in Ralstonia metallidurans. Biodegradation 14:153–168. 10.1023/a:1024043306888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krężel A, Maret W. 2016. The biological inorganic chemistry of zinc ions. Arch Biochem Biophys 611:3–19. 10.1016/j.abb.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nies D, Mergeay M, Friedrich B, Schlegel HG. 1987. Cloning of plasmid genes encoding resistance to cadmium, zinc, and cobalt in Alcaligenes eutrophus CH34. J Bacteriol 169:4865–4868. 10.1128/jb.169.10.4865-4868.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nies DH, Nies A, Chu L, Silver S. 1989. Expression and nucleotide sequence of a plasmid-determined divalent cation efflux system from Alcaligenes eutrophus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 86:7351–7355. 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Busch W, Saier MHJ. 2002. The transporter classification (TC) system. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 37:287–337. 10.1080/10409230290771528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saier MHJ, Tran CV, Barabote RD. 2006. TCDB: the Transporter Classification Database for membrane transport protein analyses and information. Nucleic Acids Res 34:D181–D186. 10.1093/nar/gkj001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]