Abstract

BACKGROUND

Surgical resection and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) represent two possible strategy in treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in Milan criteria.

AIM

To evaluate short- and long-term outcome in elderly patients (> 70 years) with HCC in Milan criteria, which underwent liver resection (LR) or RFA.

METHODS

The study included 594 patients with HCC in Milan criteria (429 in LR group and 165 in RFA group) managed in 10 European centers. Statistical analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method before and after propensity score matching (PSM) and Cox regression.

RESULTS

After PSM, we compared 136 patients in the LR group with 136 patients in the RFA group. Overall survival at 1, 3, and 5 years was 91%, 80%, and 76% in the LR group and 97%, 67%, and 41% in the RFA group respectively (P = 0.001). Disease-free survival at 1, 3, and 5 years was 84%, 60% and 44% for the LR group, and 63%, 36%, and 25% for the RFA group (P = 0.001).Postoperative Clavien-Dindo III-IV complications were lower in the RFA group (1% vs 11%, P = 0.001) in association with a shorter length of stay (2 d vs 7 d, P = 0.001).In multivariate analysis, Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score (> 10) [odds ratio (OR) = 1.89], increased value of international normalized ratio (> 1.3) (OR = 1.60), treatment with radiofrequency (OR = 1.46) ,and multiple nodules (OR = 1.19) were independent predictors of a poor overall survival while a high MELD score (> 10) (OR = 1.51) and radiofrequency (OR = 1.37) were independent factors associated with a higher recurrence rate.

CONCLUSION

Despite a longer length of stay and a higher rate of severe postoperative complications, surgery provided better results in long-term oncological outcomes as compared to ablation in elderly patients (> 70 years) with HCC in Milan criteria.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Milan criteria, Radiofrequency ablation, Surgical resection, Elderly patients, Propensity score matching

Core Tip: Surgical resection and radiofrequency ablation represent two possible strategy in treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in Milan criteria. In order to evaluate which of the two therapeutic options can provide better short-term and oncological outcomes, we compared data from 10 European centers before and after propensity score matching. Despite a longer length of stay and a higher rate of severe postoperative complications, surgery provided better results in long-term oncological outcomes as compared to ablation.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common cancer and the third global cause of cancer-related death[1]. The therapeutic strategy for patients with HCC varies considerably, according to the Barcelona clinic liver cancer (BCLC) algorithm[2], from liver transplantation to resection or ablation, passing through a series of options (chemoembolization, systemic supportive therapy, and systemic chemotherapy), based on the stage of neoplasia and patient’s general condition. The best radical treatment is still debated. For patients within Milan criteria, liver transplantation represents the treatment of choice, but unfortunately it is not suitable for all patients due to the scarcity of donors or due to an age limit[3-5].

For patients with very early and early-stage HCC (BCLC 0-A), liver resection (LR) represented the treatment of choice when liver function was well-preserved and when the remnant liver was sufficient. In elderly patients, these conditions were sometimes more precarious and required a more careful evaluation of the risk-benefit ratio in terms of treatment. In fact, the prognostic role of advanced age was not defined in patients with HCC subjected to resection nor was there any mention in official guidelines[6,7].

The aim of our work was to evaluate short-term and long-term outcomes in elderly HCC patients (> 70 years) within Milan criteria, undergoing LR or radiofrequency ablation (RFA).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

A multicentric retrospective study included 594 patients who were managed from January 2009 to January 2019 in the following centers: Centre Hépato-Biliaire Paul Brousse, Villejuif, France; Hôpital Henry Mondor, Créteil, France; Hospital Universitario Reina Sofia, Cordoba, Spain; Hôpitaux Universitaires Genève, Switzerland; Ospedale Niguarda, Milan, Italy; Nouvel Hôpital Civil, Strasbourg, France; Ospedale San Raffaele, Milan, Italy; Ospedale Miulli,Bari, Italy; Policlinico di Modena, Italy; Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, Reims, France).

We included patients who underwent laparoscopic and open LR or RFA in the study. Inclusion criteria: ≥ 70 years old patients, with Child A-B disease, in BCLC 0/A stage, with tumor within Milan criteria (solitary HCC < 5 cm in diameter, or multiple HCC < 3 lesions, each < 3 cm in diameter). Exclusion criteria: patients with tumor beyond Milan criteria, with radiological evidence of major portal/hepatic vein branch invasion, with evidence of extrahepatic disease.

The diagnosis of HCC was based on non-invasive findings [ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging] or histopathology (with biopsy), according to the European Association for Study of Liver (EASL) consensus criteria[2]. The type of treatment was planned in multidisciplinary team discussions including surgeons, hepatologists, oncologists, interventional radiologists, and pathologists.

RFA procedure

RFA was performed using an internally cooled electrode. Depending on tumor size and position, either a single or clustered electrode was used for ablation under ultrasound guidance percutaneously or using a laparoscopic or open approach. The procedure was performed under local anesthesia and intravenous sedation for percutaneous ablation, and under general anesthesia for laparoscopic and open ablations. A control liver ultrasound was performed on the first postoperative day to assess the quality of the ablation in term of necrotic area.

LR procedure

The surgical strategy was tailored based on tumor size, position, and liver function. The type of LR was defined according to the Brisbane classification[8]. Anatomical resection, wedge resection, minor and major resections were performed under general anesthesia, with an open or laparoscopic approach. Minor resection was defined as the resection of two or fewer Couinaud’s liver segments, and major resection was defined as the resection of three or more liver segments. Intraoperative ultrasonography was used routinely. A Pringle’s maneuver was used during hepatectomy to control intraoperative bleeding.

Follow-up

Short-term outcomes included operative time, blood transfusion, complications based on the Clavien-Dindo classification[9], length of hospital stay and mortality within 90 d. Long-term outcomes evaluated rates of overall survival (OS) and disease free survival. Liver function (complete blood count, liver test, and coagulation profile) were assessed on postoperative days 1, 3, and 5. Follow-up was performed with CT-scan and blood tests (including liver function and oncological markers) once every 3 mo during the first year and every 4 mo thereafter. For patients undergoing to RFA, a CT-scan at 1 mo after ablation was performed, in order to assess results of treatment according mRECIST (modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors) criteria[10]. Recurrence treatment included repeat resection, ablation, trans-arterial chemoembolization, liver transplantation, percutaneous ethanol injection, sorafenib chemotherapy, or supportive care according to the EASL-EORTC (European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer) clinical practice guidelines[2].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS 20 software. Continuous variables were compared using an independent sample t-test and Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test and Kruskal-Wallis test respectively. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) and OS curves were constructed using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards model was used in a stepwise manner (entry criterion P = 0.05 and removal criterion P = 0.1) to explore independent prognostic RFS and OS factors. We performed a propensity score matching (PSM) analysis to decrease selection bias by building a matched group of patients to compare perioperative characteristics, short-term and long-term outcomes in resection and ablation groups. Variables entered in our propensity model were co-morbidities, American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) score, Child and MELD scores, number of lesions, and tumor size. We calculated propensity scores by applying these variables to a logistic regression model and calculated C-statistics to evaluate the goodness of fit. One-to-one PSM was performed with a caliper width ranging from the < 0.2 pooled standard deviation of estimated propensity scores. A total of 136 patients out of 429 in the resection group and a total of 136 patients out of 165 in the ablation group were matched for further analyses. The relative prognostic significance of the variables in predicting OS and overall recurrence was established using univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models. All variables with a P value < 0.05 in the univariate analysis were subjected to the multivariate comparison. Results of the multivariate analysis were presented as relative risk with a corresponding 95% confidence interval.

RESULTS

Before PSM

We identified 594 patients within the Milan criteria. A total of 429 patients underwent LR and 165 RFA. Perioperative data are described in Table 1. The RFA group presented more co-morbidities than the LR group (64% vs 33%, P = 0.001). The RFA group also had a higher percentage of patients with ASA score III-IV than the LR group (73% vs 60%, P = 0.001), and a greater MELD score value (8 vs 6, P = 0.001). The LR group was associated with a larger tumor size than the RFA group (30 mm vs 24 mm, P = 0.001). Perioperative and postoperative data are described in Table 2. Operative time was significantly increased in the resection group as compared to the RFA group (205 min vs 25 min, P = 0.0001). Additionally, the perioperative blood transfusion rate was markedly higher in the LR group than in the RFA group (15% vs 8%, P = 0.001).

Table 1.

Preoperative and clinical characteristics of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Milan criteria who underwent surgical resection and radiofrequency ablation

|

Before PSM

|

After PSM

|

|||||

|

RFA (n = 165)

|

Surgery (n = 429)

|

P

value

|

RFA (n = 136)

|

Surgery (n = 136)

|

P

value

|

|

| Male, n (%) | 116 (70) | 319 (74) | 0.35 | 98 (72) | 104 (76) | 0.48 |

| Age (yr) median (range) | 75 (70-89) | 74.9 (70-90) | 0.71 | 75 (70-88) | 74.7 (70-86.1) | 0.56 |

| BMI (kg/cm²) median (range) | 26.7 (19-51) | 26.7 (19-52) | 0.37 | 26.7 (19-51) | 26 (21-41) | 0.85 |

| Co-morbidities > 2, n (%) | 107 (64) | 142 (33) | 0.001 | 83 (61) | 81 (60) | 0.90 |

| Cause of Cirrhosis n (%) | 0.002 | 0.11 | ||||

| Hepatitis C virus | 89 (54) | 217 (50) | 73 (54) | 68 (50) | ||

| Hepatitis B virus | 10 (6) | 80 (19) | 10 (7) | 22 (16) | ||

| Alcohol | 37 (22) | 60 (14) | 31(23) | 23 (17) | ||

| Others | 29 (18) | 72 (17) | 22 (16) | 23 (17) | ||

| ASA score, n (%) | 0.004 | 0.59 | ||||

| I-II | 45 (27) | 172 (40) | 41 (30) | 36 (26) | ||

| III-IV | 120 (73) | 257 (60) | 95 (70) | 100 (74) | ||

| Blood tests median (range) | ||||||

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1 (0.2-2.8) | 0.9 (0.18-4.5) | 0.41 | 1 (0.2-2.8) | 0.8 (0.2-4.5) | 0.02 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.9 (0.5-2.5) | 1 (0.2-2.5) | 0.03 | 0.9 (0.5-2.3) | 0.9 (0.4-2.5) | 0.02 |

| Platelet count × 109/L | 131 (10-856) | 178 (45-900) | 0.00 | 131.5 (10-856) | 155 (47-573) | 0.57 |

| INR | 1.1 (0.9-2.4) | 1.2 (0.6-2.5) | 0.00 | 1.1 (0.9-2.4) | 1.1 (0.8-2.5) | 0.00 |

| Child Pugh, n (%) | 0.52 | 0.87 | ||||

| A | 139 (84) | 370 (86) | 114 (84) | 116 (85) | ||

| B | 26 (16) | 59 (14) | 22 (16) | 20 (15) | ||

| MELD median (range) | 8 (6-18) | 6 (6-17) | 0.00 | 8 (6-18) | 8 (6-17) | 0.05 |

| Tumors number, n (%) | 0.07 | 0.71 | ||||

| Single nodule | 142 (86) | 392 (91) | 117 (86) | 120 (88) | ||

| Multi nodules | 23 (14) | 37 (9) | 19 (14) | 16 (12) | ||

| Tumor size (mm) n (%) | 24 (10-50) | 30 (7-50) | 0.00 | 25 (10-50) | 24.5 (7-50) | 0.9 |

| < 20 | 49 (30) | 33 (8) | 0.00 | 36 (26) | 28 (21) | 0.31 |

| 20-50 | 116 (70) | 396 (92) | 100 (74) | 108 (79) | ||

| Bilobar tumor, n (%) | 8 (5) | 8 (2) | 0.08 | 6 (4) | 2 (1) | 0.28 |

| Tumor location, n (%) | 0.28 | 0.17 | ||||

| 1 | 2 (1) | 8 (2) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | ||

| 2 | 14 (8) | 41 (10) | 13 (9) | 14 (10) | ||

| 3 | 12 (7) | 42 (10) | 10 (7) | 20 (15) | ||

| 4 | 20 (12) | 53 (12) | 15 (11) | 13 (9) | ||

| 5 | 28 (17) | 63 (15) | 21 (15) | 27 (19) | ||

| 6 | 27 (16) | 87 (20) | 23 (17) | 29 (21) | ||

| 7 | 18 (11) | 60 (14) | 16 (12) | 11 (8) | ||

| 8 | 44 (28) | 75 (17) | 37 (27) | 21 (15) | ||

| Histologically proven, n (%) | 42 (25) | 115 (27) | 0.75 | 36 (26) | 42 (31) | 0.50 |

| Previous treatment, n (%) | 53 (32) | 53 (12) | 0.00 | 42 (31) | 21 (15) | 0.004 |

Continuous variables were compared using an independent sample t-test and Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test and Kruskal-Wallis test respectively. PSM: Propensity score matching; BMI: Body mass index; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; MELD: Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; RFA: Radiofrequency ablation; INR: International normalized ratio.

Table 2.

Clinical and perioperative characteristics of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Milan criteria who underwent surgical resection and radiofrequency ablation

|

Before PSM

|

After PSM

|

|||||

|

RFA (n = 165)

|

Surgery (n = 429)

|

P

value

|

RFA (n = 136)

|

Surgery (n = 136)

|

P

value

|

|

| Operative time (min) median (range) | 25 (5-250) | 205 (55-600) | 0.002 | 25 (5-250) | 190 (55-600) | 0.001 |

| Blood transfusion, n (%) | 13 (8) | 66 (15) | 0.01 | 11(8) | 23 (17) | 0.04 |

| Dindo-Clavien Classification, n (%) | 0.001 | 0.002 | ||||

| I-II | 163 (99) | 378 (91) | 134 (98) | 121 (89) | ||

| III-IV | 2 (1) | 38 (9) | 2 (1) | 15 (11) | ||

| Postoperative complication, n (%) | 0.001 | 0.002 | ||||

| Yes | 31 (19) | 188 (44) | 28 (21) | 75 (55) | ||

| No | 134 (81) | 241 (56) | 108 (79) | 61 (45) | ||

| Type of complication, n (%) | ||||||

| Liver failure | 1 (1) | 35 (8) | 0.002 | 1 (0.7) | 14 (10) | 0.001 |

| Ascites | 3 (2) | 60 (14) | 0.003 | 3 (2) | 17 (12) | 0.002 |

| Biliary leakage | 0 (0) | 9 (2) | 0.064 | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | 0.25 |

| Hemorrhage | 4 (2) | 19 (4) | 0.340 | 3 (2) | 11 (8) | 0.51 |

| Systemic Infection | 4 (2) | 30 (7) | 0.03 | 4 (3) | 14 (10) | 0.03 |

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 0 (0) | 23 (5) | 0.00 | 0 (0) | 8 (6) | 0.007 |

| Wound infection | 2 (1) | 12 (3) | 0.37 | 2 (1) | 7 (5) | 0.17 |

| Portal thrombosis | 1 (1) | 3 (1) | 1.007 | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1) | 1 |

| Pulmonary | 7 (4) | 33 (8) | 0.15 | 6 (4) | 15 (11) | 0.07 |

| Cardiac | 1 (1) | 18 (4) | 0.03 | 1 (0.7) | 8 (6) | 0.03 |

| Renal | 1 (1) | 18 (4) | 0.03 | 1 (0.7) | 6 (4) | 0.12 |

| Reoperation, n (%) | 0 (0) | 7 (2) | 0.19 | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 0.5 |

| Postoperative treatment, n (%) | 3 (2) | 19 (4) | 0.15 | 3 (2) | 10 (7) | 0.08 |

| Length of hospital stay median (range) | 2 (1-23) | 6 (1-203) | 0.00 | 2 (1-23) | 7 (1-203) | 0.00 |

| Mortality 90 d, n (%) | 3 (2) | 13 (3) | 0.001 | 3 (2) | 4 (3) | 1 |

Continuous variables were compared using an independent sample t-test and Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test and Kruskal-Wallis test respectively. PSM: Propensity score matching; RFA: Radiofrequency ablation.

The RFA postoperative course was burdened by a lower rate of serious complications (Clavien-Dindo III-IV) than the LR group (1% vs 9%, P = 0.001). The RFA group had also significantly shorter postoperative hospital stays than the LR group (2 d vs 6 d, P = 0.001).

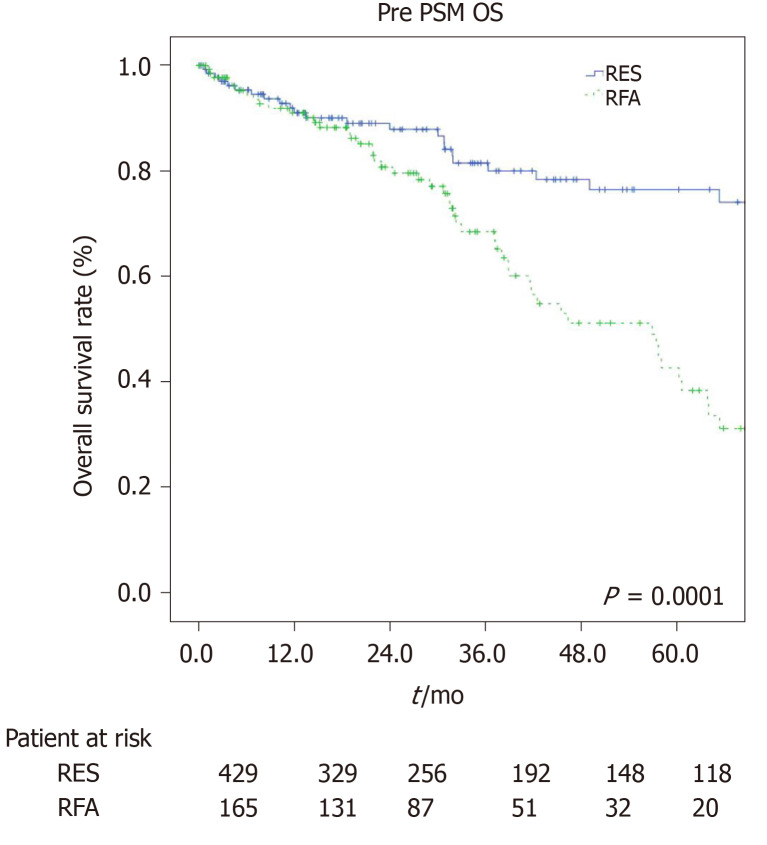

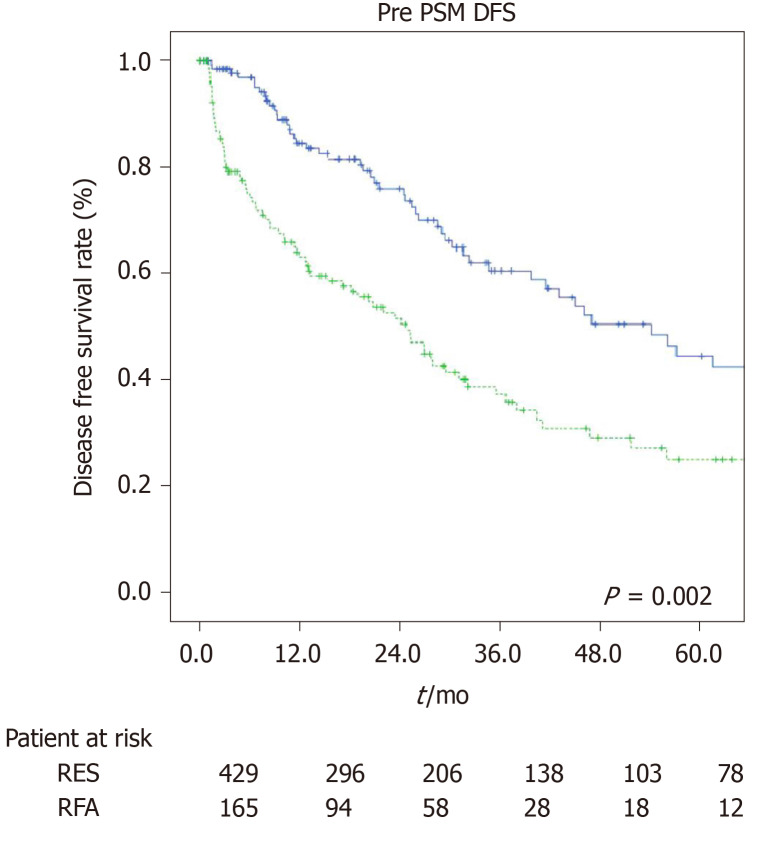

The estimated 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates were 91.9%, 84%, and 75.5% for the LR group and 92%, 66.4%, and 37.8% for the RFA group (P = 0.001, Figure 1). The estimated 1-, 3-, and 5-year disease-free survival rates were 85.7%, 63.7%, and 50.3% for the LR group, and 66.7%, 37.8%, and 27.7% for the RFA group (P = 0.001, Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Survival curves (Kaplan-Meier method) of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Milan criteria who underwent surgical resection and radiofrequency ablation before propensity score matching. Overall survival curves were constructed using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Overall survival significantly differs between the two groups. PSM: Propensity score matching; OS: Overall survival; RES: Resection; RFA: Radiofrequency ablation.

Figure 2.

Tumor recurrence curves (Kaplan-Meier method) of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Milan criteria who underwent surgical resection and radiofrequency ablation before propensity score matching. Recurrence-free survival curves were constructed using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence significantly differs between the two groups. PSM: Propensity score matching; DFS: Disease-free survival; RES: Resection; RFA: Radiofrequency ablation.

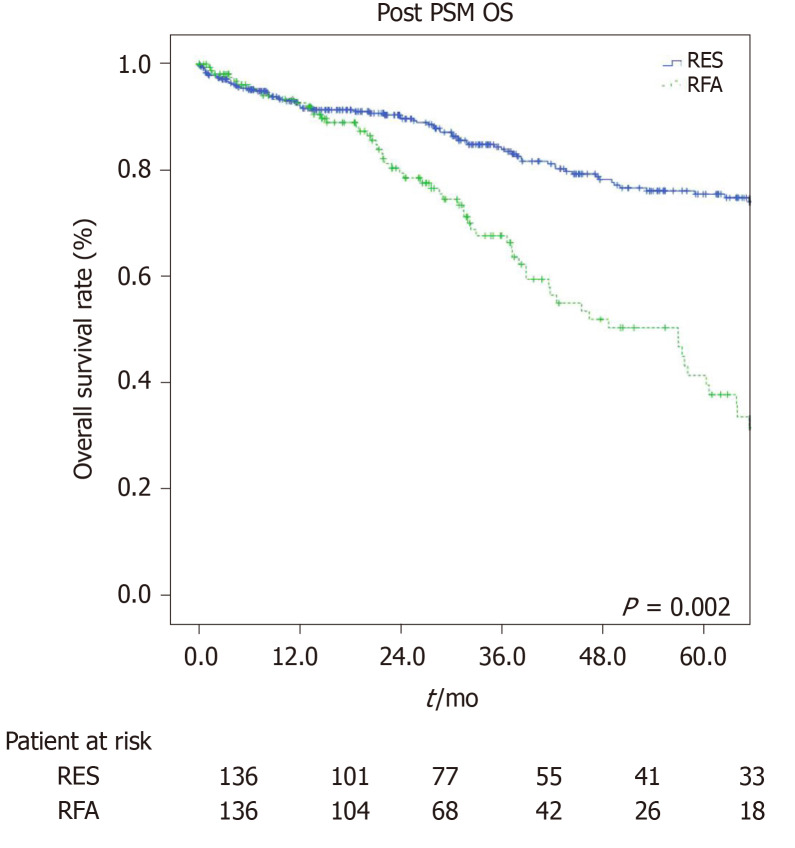

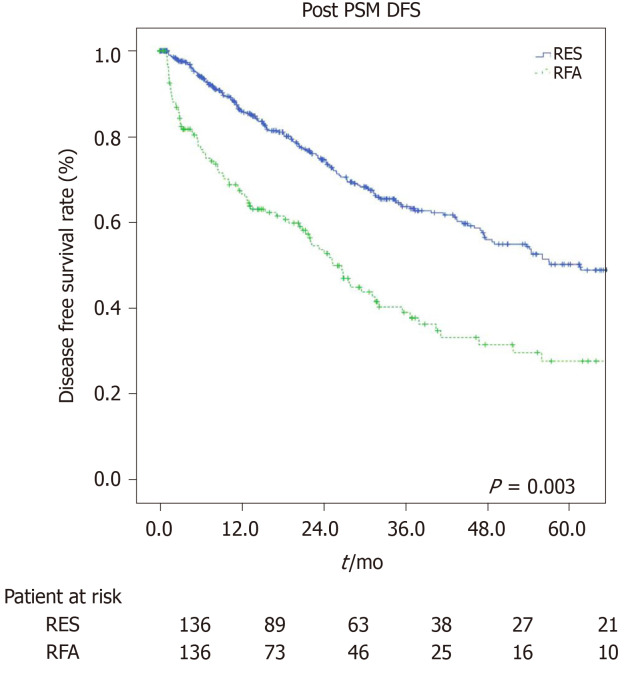

After PSM

After matching, we obtained a comparable population for both groups (Table 1). The variables included in the PSM are comorbidities, ASA and MELD score, tumor size and number of lesions. The use of these parameters for the PSM allowed us to obtain two samples to be compared more homogeneous, and therefore to have short- and long-term results between the two groups less burdened by other variables, although the number of patients in the two groups are smaller after pairing Perioperative and postoperative results are described in Table 2. The postoperative course of the RFA group was burdened by a lower rate of serious complications (Clavien-Dindo III-IV) as compared to the LR group (1% vs 11%, P = 0.001). The RFA group had also significantly shorter postoperative hospital stays than the LR group (2 d vs 7 d, P = 0.001). Operative time was significantly increased in the LR group as compared to the RFA group (median range: 190 min vs 25 min, P = 0.001). In addition, the perioperative blood transfusion rate was markedly higher in the LR group than in the RFA group (17% vs 8%, P = 0.001).

The estimated 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates were 91%, 80.2%, and 76.6% for the LR group and 97.7%, 68.9%, and 40.8% for the RFA group (P = 0.001, Figure 3) respectively. The estimated 1-, 3-, and 5-year disease-free survival rates were 84.5%, 60.6%, and 44.4% for the LR group, and 63.2%, 35.7%, and 25.1% for the RFA group (P = 0.001, Figure 4) respectively.

Figure 3.

Survival curves (Kaplan-Meier method) of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Milan criteria who underwent surgical resection and radiofrequency ablation after propensity score matching. Overall survival curves were constructed using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. After propensity score matching, survival remained significantly different. PSM: Propensity score matching; OS: Overall survival; RES: Resection; RFA: Radiofrequency ablation.

Figure 4.

Tumor recurrence curves (Kaplan-Meier method) of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Milan criteria who underwent surgical resection and radiofrequency ablation after propensity score matching. Recurrence-free survival curves were constructed using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. After propensity score matching, recurrence remained significantly different. PSM: Propensity score matching; DFS: Disease-free survival; RES: Resection; RFA: Radiofrequency ablation.

Multivariate analysis

We evaluated factors influencing overall and disease-free survival using univariate and multivariate analyses. Multivariate analyses (Table 3) showed that the therapeutic choice of radiofrequency [hazard ratio: 1.46; (1.1-1.79), P = 0.001], international normalized ratio > 1.3 mg/dL [hazard ratio 1.60, (1.03-2.49), P = 0 03], and MELD score > 10 [1.89, (1.21-2.92), P = 0.005] were independent risk factors for OS. Concerning the rate of recurrence (Table 4), radiofrequency [1.37 (1.17-1.60), P = 0.0001] and MELD score > 10 [1.51, (1.04-2.17) P = 0.0001] were both considered poor prognostic factors.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate models for survival

|

Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

|

|

|

P

value

|

RR (95%CI)

|

P value

|

|

| RFA | 0.001 | 1.46 (1.1-1.79) | 0.001 |

| Age ≤ 75 yr | 0.63 | ||

| Male | 0.001 | ||

| Co-morbidity ≥ 2 | 0.001 | ||

| BMI < 24 | 0.001 | ||

| ASA score III-IV | 0.07 | ||

| TBil (mg/dL > 2) | 0.001 | ||

| Crea (mg/dL > 1) | 0.57 | ||

| PLT (U/μL > 150 × 10³) | 0.001 | ||

| INR (> 1.3) | 0.001 | 1.60 (1.03-2.49) | 0.03 |

| Tumor size < 3 cm | 0.001 | ||

| Multiple nodule | 0.001 | 1.19 (1.08-4.17) | 0.03 |

| Child Pugh A | 0.001 | ||

| MELD > 10 | 0.007 | 1.89 (1.21-2.92) | 0.005 |

The relative prognostic significance of the variables in predicting overall survival and overall recurrence was established using univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models. Radiofrequency ablation, international normalized ratio > 1.3 mg/dL, and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score >10 were independent risk factors for overall survival. RFA: Radiofrequency ablation; INR: International normalized ratio; MELD: Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; RR: Relative risk; CI: Confidence interval; BMI: Body mass index; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; PLT: Platelets; TBil: Total bilirubin; Crea: Creatinine.

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate models for recurrence

|

Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

|

|

|

P

value

|

RR (95%CI)

|

P

value

|

|

| RFA | 0.001 | 1.37 (1.17-1.60) | 0.0001 |

| Age ≤ 75 yr | 0.28 | ||

| Male | 0.91 | ||

| Co-morbidity ≥ 2 | 0.01 | ||

| BMI < 24 | 0.61 | ||

| ASA score III-IV | 0.61 | ||

| Bilirubin (mg/dL > 2) | 0.37 | ||

| Creatinine (mg/dL > 1) | 0.62 | ||

| PLT (U/μL > 150 × 10³) | 0.001 | ||

| INR (> 1.3) | 0.02 | ||

| Tumor size < 3 cm | 0.001 | ||

| Multiple nodule | 0.07 | ||

| Child Pugh A | 0.26 | ||

| MELD > 10 | 0.01 | 1.51 (1.04-2.17) | 0.03 |

The relative prognostic significance of the variables in predicting overall survival and overall recurrence was established using univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models. Radiofrequency ablation and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score > 10 were considered poor prognostic factors. RFA: Radiofrequency ablation; INR: International normalized ratio; MELD: Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; RR: Relative risk; CI: Confidence interval; BMI: Body mass index; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; PLT: Platelets.

DISCUSSION

This study suggested that surgical treatment provided better results in terms of long-term oncological outcomes (OS and disease-free survival) as compared to ablative treatment (RFA) in elderly HCC patients (> 70 years) within the Milan criteria, despite a longer and more complicated postoperative course.

Increased life expectancy, ageing, and the accumulation of chronic pathologies, such as obesity, diabetes, and some inadequate living habits (excess alcohol and smoking) led to the establishment of conditions of oxidative stress and inflammation which seemed to be the substratum favouring the onset of HCC, despite the reduction in the incidence rate of HBV and HCV-related liver disease, especially in Western countries[11].

For this reason, our study aimed to examine a part of the population still growing today, that of the elderly, (≥ 70 years), and namely patients within Milan criteria unsuitable for liver transplantation due to a reached limit of age and who should be managed either with RFA or LR. We analyzed short-term outcomes, namely perioperative characteristics (operative time, postoperative complications, length of hospital stay, and mortality within 90 d), as well as long-term outcomes, namely oncological results (OS and disease-free survival). LR was the treatment of choice in patients with very early and early-stage HCC, with a well-preserved liver function and sufficient residual liver volume. Radiofrequency was indicated in patients who were not candidates to surgery, and who presented with higher rates of local disease control and OS than other local ablative therapies[2,12,13] inducing a tumor necrosis, which guarantees a valid control of margin[14]. Microwave ablation is an alternative procedure, equally based on induction tumor destruction with heat generation, but with a different mechanism, and which seems to show promising performances although in treatment of HCC of 3-5 cm size, adjacent to vessels or gallbladder[15].

The most effective therapeutic strategy in the very early and early stages of HCC was still a matter for debate.

Radiofrequency made use of less invasiveness, thereby presenting a shorter hospital stay, fewer costs, a lower rate of major complications, as shown in multiple randomized clinical trials and meta-analyses[16-20]. On the other hand, LR provided better oncological outcomes in terms of local disease control[17,19,21] and in long-term OS[17,22,23], as reported in randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses, also and above all, considering the characteristics of HCC which presented a tendency to micro-dissemination in portal and hepatic veins and to the generation of micro-metastases around the lesion[24,25].

Recent studies have shown that this therapeutic algorithm can also be extended to elderly patients[26-29]. Old age represented an important risk factor concerning postoperative morbidity and mortality, especially in association with major surgical procedures, but thanks to the evolution of surgical techniques and an increasingly careful postoperative management, it was possible to extend the resective treatment even to the most advanced age groups. According to these findings, our data also showed a shorter postoperative course in patients undergoing RFA, in terms of major postoperative complications (Clavien-Dindo III-IV) (1% vs 9%, P = 0.001), length of hospital stay (median range: 2 d vs 6 d, P = 0.001), and also mortality rate within 90 d (0% vs 3%, P = 0.02).

Directly related to the type of procedure, data regarding operative time (median range: 25 min vs 205 min, P = 0.001) and percentage of perioperative blood transfusions (8% vs 15%, P = 0.001) highlighted the lower invasiveness of the ablative strategy. Although there were studies which showed overlapping[30] or even more satisfactory[31] results in the long-term outcomes of RFA managed patients, our work resulted in a clear superiority in patients managed with LR with a 1-, 3-, 5-year OS of 91.9%, 84%, and 75.5% as compared to 92%, 66.4%, and 37.8% for the RFA group (P = 0.001), and a 1-, 3-, and 5-year disease-free survival rate of 85.7%, 63.7%, and 50.3% for the LR group, and 66.7%, 37.8%, and 27.7% for the RFA group (P = 0.001).

To prevent any potential selection bias, we applied a PSM. Once co-morbidities, ASA and MELD score, tumor number, and tumor size of both groups had become balanced, we confirmed that LR provided better OS and disease-free survival than RFA treatment in elderly HCC patients with Milan criteria. On the other hand, the percentage of postoperative complications and blood transfusions, operative time, and length of hospital stay were also higher in the resection group even after PSM while the mortality value within 90 d was no longer significant. These data put emphasis on how important it was not only for the preoperative assessment of patients, which allowed us to choose a targeted and tailored therapeutic strategy, but also for the preoperative preparation of patients, which was related to the chosen procedure and made them less susceptible to any events secondary to the treatment itself, especially in elderly patients.

Elderly patients were often considered a high risk group for major surgery regarding the higher incidence of co-morbidities. In the past, this assumption seemed to have been a limit in the evaluation of the therapeutic choice. As a result, this category of patients was often undertreated, and this attitude may have distorted the previous results in terms of overall and recurrent survival.

This study had some limitations. First of all, because of its retrospective nature, there was a possibility of unavoidable selection bias. In addition, only 25.4% of patients undergoing RFA had a biopsy, although they had received a radiological diagnosis according to guidelines. Third, the surgical procedures adopted were very different, from anatomical to non-anatomical ones. In addition to this, there was the multicentric nature of the study which could be a determining factor in further bias in selection and evaluation criteria.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our work reached similar results to the ones of several recent studies which had it that LR guaranteed better outcomes in terms of overall and disease-free survival than RFA in elderly HCC patients within Milan criteria, and so it was mandatory to outline the best therapeutic strategy without foreclosures, rather respecting the parameters of patient selection and tailored treatment. LR should be considered for patients with a better liver function and a longer life expectancy, in order to balance the postoperative risk of treatment with benefits in long-term overall and disease-free survival.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Surgical resection and radiofrequency ablation represent two alternative treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma.

Research motivation

Evaluation between surgery and radiofrequency ablation in elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma within Milan criteria.

Research objectives

To evaluate short- and long-term outcome in elderly patients (> 70 years) with HCC in Milan criteria, which underwent liver resection (LR) or radiofrequency ablation.

Research methods

Analysis of results from multicentric data about overall and disease-free survival linked to the two strategy.

Research results

Our data before and after propensity score matching show a better overall survival and disease-free survival at 1, 3, and 5 years in patient who underwent LR compared to ablation group.

Research conclusions

This retrospective multicenter study shows that LR provides better overall and disease-free survival despite a higher rate of post-operative complications and longer hospital stay when compared with ablation in elderly patients.

Research perspectives

With data from this retrospective multicenter study, a purpose of multicenter randomized controlled trials should be considered.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of “F. Miulli” General Regional Hospital.

Informed consent statement: Patients were not required to give informed consent to the study because the analysis used anonymous clinical data that were obtained after each patient agreed to treatment by written consent.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors are aware of the content of the manuscript and have no conflict of interest.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: February 1, 2021

First decision: February 27, 2021

Article in press: April 21, 2021

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chen Z, Liao R, Zheng L S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

Contributor Information

Maria Conticchio, Departement of Emergency and Trasplantation of Organs, General Surgery Unit “M. Rubino”, Policlinico di Bari, Bari 70124, Italy.

Riccardo Inchingolo, Interventional Radiology Unit, "F. Miulli" General Regional Hospital, Acquaviva delle Fonti 70021, Italy. riccardoin@hotmail.it.

Antonella Delvecchio, Department of Emergency and Organ Transplantation, General Surgery Unit “M. Rubino”, University of Bari, Ceglie Messapica 70124, Italy.

Letizia Laera, Department of Oncology, "F. Miulli" General Regional Hospital, Acquaviva delle Fonti 70021, Italy.

Francesca Ratti, Department of Surgery, Univ Vita Salute San Raffaele, Milan 20132, Italy.

Maximiliano Gelli, Department of Visceral and Oncological Surgery, Gustave Roussy Cancer Campus Grand Paris, Villejuif 94800, France.

Ferdinando Anelli, Unit of Oncologic and Pancreatic Surgery, Hospital University Reina Sofía, Cordoba 14004, Spain.

Alexis Laurent, Department of Digestive and Hepatobiliary Surgery, Henri Mondor University Hospital, Creteil 94000, France.

Giulio Vitali, Department of Surgery, University of Geneva Hospitals, Geneva 44041, Switzerland.

Paolo Magistri, Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Surgery and Liver Transplantation Unit, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Modena 41124, Italy.

Giacomo Assirati, Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Surgery and Liver Transplantation Unit, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Modena 41124, Italy.

Emanuele Felli, Institut de Recherche Contre les Cancers de l'Appareil Digestif, Strasbourg 67000, France.

Taiga Wakabayashi, Department of Surgery, Keio University School of Medicine, Shinjuku-ku 160-8582, Japan.

Patrick Pessaux, Hepato-Biliary and Pancreatic Surgical Unit, Nouvel Hôpital Civil, Strasbourg cedex 67091, France.

Tullio Piardi, Department of Hepatobiliary, Pancreatic and Digestive Surgery, University Hospital Robert Debré of Reims, Reims 51100, France; Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery Unit, General Surgery Departement, Troyes Hospital, Troyes Zip or Postal Code, France; University of Champagne - Ardenne, Reims 51100, France.

Fabrizio di Benedetto, Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Surgery and Liver Transplantation Unit, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Modena 41124, Italy.

Nicola de'Angelis, Unit of Minimally Invasive and Robotic Digestive Surgery, "F. Miulli" General Regional Hospital, Acquaviva delle Fonti 70021, Italy.

Javier Briceño, Department of General and Digestive Surgery, Reina Sofia University Hospital, Cordoba 14004, Spain.

Antonio Rampoldi, Interventional Radiology Unit, Niguarda Hospital, Milan 20132, Italy.

Renè Adam, Department of Surgery, Hopital Paul Brousse, Villejuif 94800, France.

Daniel Cherqui, Hepatobiliary Center, Hopital Paul Brousse, Villejuif 94800, France.

Luca Antonio Aldrighetti, Unit of Hepato-Pancreatic-Biliary Surgery, Univ Vita Salute San Raffaele, Milan 20132, Italy.

Riccardo Memeo, Unit of Hepato-Pancreatic-Biliary Surgery, "F. Miulli" General Regional Hospital, Acquaviva delle Fonti 70021, Italy.

Data sharing statement

No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69:182–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cherqui D, Laurent A, Mocellin N, Tayar C, Luciani A, Van Nhieu JT, Decaens T, Hurtova M, Memeo R, Mallat A, Duvoux C. Liver resection for transplantable hepatocellular carcinoma: long-term survival and role of secondary liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 2009;250:738–746. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bd582b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sogawa H, Shrager B, Jibara G, Tabrizian P, Roayaie S, Schwartz M. Resection or transplant-listing for solitary hepatitis C-associated hepatocellular carcinoma: an intention-to-treat analysis. HPB (Oxford) 2013;15:134–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00548.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spolverato G, Vitale A, Ejaz A, Kim Y, Maithel SK, Cosgrove DP, Pawlik TM. The relative net health benefit of liver resection, ablation, and transplantation for early hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg. 2015;39:1474–1484. doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-2987-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tandon P, Garcia-Tsao G. Prognostic indicators in hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of 72 studies. Liver Int. 2009;29:502–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01957.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao LY, Huo RR, Xiang X, Torzilli G, Zheng MH, Yang T, Liang XM, Huang X, Tang PL, Xiang BD, Li LQ, You XM, Zhong JH. Hepatic resection for elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of more than 17,000 patients. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;12:1059–1068. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2018.1517045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Terminology Committee of the International Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association Strasberg SM. Belghiti J, Clavien P-A, Gadzijev E, Garden JO, Lau WY, Makuuchi M, Strong RW. The Brisbane 2000 Terminology of Liver Anatomy and Resections. HPB. 2000;2:333–339. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Llovet JM, Lencioni R. mRECIST for HCC: Performance and novel refinements. J Hepatol. 2020;72:288–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrick JL, Florio AA, Znaor A, Ruggieri D, Laversanne M, Alvarez CS, Ferlay J, Valery PC, Bray F, McGlynn KA. International trends in hepatocellular carcinoma incidence, 1978-2012. Int J Cancer. 2020;147:317–330. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lau WY, Leung TW, Yu SC, Ho SK. Percutaneous local ablative therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a review and look into the future. Ann Surg. 2003;237:171–179. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000048443.71734.BF. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruix J, Sherman M American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020–1022. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ng KK, Lam CM, Poon RT, Ai V, Tso WK, Fan ST. Thermal ablative therapy for malignant liver tumors: a critical appraisal. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:616–629. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.02991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu J, Yu XL, Han ZY, Cheng ZG, Liu FY, Zhai HY, Mu MJ, Liu YM, Liang P. Percutaneous cooled-probe microwave vs radiofrequency ablation in early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2017;66:1172–1173. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Livraghi T, Meloni F, Di Stasi M, Rolle E, Solbiati L, Tinelli C, Rossi S. Sustained complete response and complications rates after radiofrequency ablation of very early hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: Is resection still the treatment of choice? Hepatology. 2008;47:82–89. doi: 10.1002/hep.21933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang J, Yan L, Cheng Z, Wu H, Du L, Wang J, Xu Y, Zeng Y. A randomized trial comparing radiofrequency ablation and surgical resection for HCC conforming to the Milan criteria. Ann Surg. 2010;252:903–912. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181efc656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feng K, Yan J, Li X, Xia F, Ma K, Wang S, Bie P, Dong J. A randomized controlled trial of radiofrequency ablation and surgical resection in the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;57:794–802. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Luo Q, Li Y, Deng S, Wei S, Li X. Radiofrequency ablation vs hepatic resection for small hepatocellular carcinomas: a meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9:e84484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fang Y, Chen W, Liang X, Li D, Lou H, Chen R, Wang K, Pan H. Comparison of long-term effectiveness and complications of radiofrequency ablation with hepatectomy for small hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:193–200. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu XL, Liu XD, Liang M, Luo BM. Radiofrequency Ablation vs Hepatic Resection for Small Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials with Meta-Analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis. Radiology. 2018;287:461–472. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017162756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ueno S, Sakoda M, Kubo F, Hiwatashi K, Tateno T, Baba Y, Hasegawa S, Tsubouchi H Kagoshima Liver Cancer Study Group. Surgical resection vs radiofrequency ablation for small hepatocellular carcinomas within the Milan criteria. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:359–366. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yun WK, Choi MS, Choi D, Rhim HC, Joh JW, Kim KH, Jang TH, Lee JH, Koh KC, Paik SW, Yoo BC. Superior long-term outcomes after surgery in child-pugh class a patients with single small hepatocellular carcinoma compared to radiofrequency ablation. Hepatol Int. 2011;5:722–729. doi: 10.1007/s12072-010-9237-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi M, Zhang CQ, Zhang YQ, Liang XM, Li JQ. Micrometastases of solitary hepatocellular carcinoma and appropriate resection margin. World J Surg. 2004;28:376–381. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-7308-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sasaki A, Kai S, Iwashita Y, Hirano S, Ohta M, Kitano S. Microsatellite distribution and indication for locoregional therapy in small hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103:299–306. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oweira H, Petrausch U, Helbling D, Schmidt J, Mannhart M, Mehrabi A, Schöb O, Giryes A, Abdel-Rahman O. Early stage hepatocellular carcinoma in the elderly: A SEER database analysis. J Geriatr Oncol. 2017;8:277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim KC, Chow PK, Allen JC, Siddiqui FJ, Chan ES, Tan SB. Systematic review of outcomes of liver resection for early hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1622–1629. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kishida N, Hibi T, Itano O, Okabayashi K, Shinoda M, Kitago M, Abe Y, Yagi H, Kitagawa Y. Validation of hepatectomy for elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:3094–3101. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4350-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pompili M, Saviano A, de Matthaeis N, Cucchetti A, Ardito F, Federico B, Brunello F, Pinna AD, Giorgio A, Giulini SM, De Sio I, Torzilli G, Fornari F, Capussotti L, Guglielmi A, Piscaglia F, Aldrighetti L, Caturelli E, Calise F, Nuzzo G, Rapaccini GL, Giuliante F. Long-term effectiveness of resection and radiofrequency ablation for single hepatocellular carcinoma ≤3 cm. Results of a multicenter Italian survey. J Hepatol. 2013;59:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen MS, Li JQ, Zheng Y, Guo RP, Liang HH, Zhang YQ, Lin XJ, Lau WY. A prospective randomized trial comparing percutaneous local ablative therapy and partial hepatectomy for small hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2006;243:321–328. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000201480.65519.b8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peng ZW, Lin XJ, Zhang YJ, Liang HH, Guo RP, Shi M, Chen MS. Radiofrequency ablation vs hepatic resection for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinomas 2 cm or smaller: a retrospective comparative study. Radiology. 2012;262:1022–1033. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No additional data are available.