Abstract

Genomic sequencing, bioinformatics, and initial speciation (e.g., relative abundance) of the commensal microbiome have revolutionized the way we think about the “human” body in health and disease. The interactions between the gut bacteria and the immune system of the host play a key role in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal diseases, including those impacting the esophagus. Although relatively stable, there are a number of factors that may disrupt the delicate balance between the luminal esophageal microbiome (EM) and the host. These changes are thought to be a product of age, diet, antibiotic and other medication use, oral hygiene, smoking, and/or expression of antibiotic products (bacteriocins) by other flora. These effects may lead to persistent dysbiosis which in turn increases the risk of local inflammation, systemic inflammation, and ultimately disease progression. Research has suggested that the etiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease-related esophagitis includes a cytokine-mediated inflammatory component and is, therefore, not merely the result of esophageal mucosal exposure to corrosives (i.e., acid). Emerging evidence also suggests that the EM plays a major role in the pathogenesis of disease by inciting an immunogenic response which ultimately propagates the inflammatory cascade. Here, we discuss the potential role for manipulating the EM as a therapeutic option for treating the root cause of various esophageal disease rather than just providing symptomatic relief (i.e., acid suppression).

Keywords: Microbiome, Gastroesophageal reflux disease, Probiotics, Prebiotics, Bacteriocins, Dysbiosis, Barrett’s esophagus, Esophageal cancer, Esophagitis, Eosinophilic esophagitis

Core Tip: The interactions between the gut bacteria and the immune system of the host play a key role in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal diseases, including those impacting the esophagus. This evidence-based review brings forward the emerging data on the microbial changes related to esophageal disease. Better understanding of these data will lead to mitigation strategies for intervention and innovation.

INTRODUCTION

Investigation of the gut microbiome has progressively changed the understanding of esophageal disease. During the past two decades, 16S rRNA gene sequencing was used to characterize and compare the esophageal microbiomes (EMs) of healthy individuals with those in patients with esophageal diseases including gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), Barrett’s esophagus (BE), esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), and esophageal motility disorders[1,2]. Analyzing the compositional differences between healthy and dysbiotic microbiomes in the esophagus has provided further insight into the pathogenesis of GERD and related sequelae along with other associated pathology (Table 1). In particular, it is noted that the diseased esophagus, relative to healthy controls, is colonized by a bacterial population that is unusually rich in gram-negative species. Furthermore, the aberrant bacteria conform, to a great extent, with pro-inflammatory oral pathogens. This insight into the EM can help guide further investigation into new therapeutic tools that target these mechanisms.

Table 1.

Changes in local flora that occur with particular esophageal disease states

|

Disease states

|

Changes in microbiome

|

| GERD | Non-erosive reflux disease: A shift towards Proteobacteria (Neisseria oralis, Moraxella spp.) and Bacteroidetes (Bacteroides uniformis, Capnocytophaga spp., and Prevotella pallens); A shift away from Fusobacteria (Leptotrichia) and Actinobacteria (Rothia spp.); Increased abundance of Dorea spp. |

| Reflux esophagitis: Decreased Firmicutes (Mogibacterium spp., Streptococcus infantis, Solobacterium moorei) and increased Fusobacteria (Leptotrichia spp.) and Proteobacteria (Marivita spp., Nisaea spp., Mesorhizobium spp.) | |

| Barrett’s esophagus | Increased Fusobacteria, and Proteobacteria (Neisseria spp., and Campylobacter spp.); Decreased alpha diversity as well as Bacteroidetes and Prevotella |

| Esophageal adenocarcinoma | Increased abundance of Proteobacteria and decreased Firmicutes; Relatively unchanged Streptococci abundance |

| Eosinophilic esophagitis | Increased Proteobacteria (Neisseria and Haemophilus) and Corynebacterium; Decrease in Clostridia spp. |

GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

NORMAL GASTROESOPHAGEAL MICROFLORA

Characterizing the ‘normal’ vs ‘abnormal’ esophageal luminal flora

Metagenomic sequencing of the human population revealed that the gastroesophageal (GE) microbiome is predominated roughly in order of prevalence by six major phyla: Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria, and Saccharibacteria[3]. Typically, Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes often predominate-primarily in response to abundance of either Bacteroides or Clostridium spp.[4]. Here, phylum-level classification is an oversimplification that does not account for the diversity that exists in a relatively simple microbiome like that found in the distal esophagus. Considerable variation of both the identity and relative abundance of specific bacteria exists, especially when the taxa are characterized with greater resolution by elucidation of taxa to species or strain-level. In 2009, one group identified two distinct types of GE microbiomes[5]. Comparing the results from individuals with GERD to healthy controls[5], they characterized the control population, which is predominated by gram-positive organisms, Streptococcus spp., as a type I microbiome. The type II microbiome was largely associated with pathological states, such as GERD and BE, and demonstrated a relative increase in abundance of gram-negative anaerobes[5].

Further work delineated the taxa and observed that three distinct clusters of esophageal microbiotas were predominant in biopsies of human esophageal tissue. Each is characterized by their relative abundance of Streptococcus and Prevotella spp.[6]. Cluster 1 is intermediate, with an approximately equal proportion of both genera with an increased presence of Haemophilus and Rothia spp. Cluster 2 consists predominantly of Streptococcus spp. Cluster 3 is primarily represented by Prevotella spp.[6].

In addition to inter-individual variation, the composition of luminal microbiota also varies in the esophagus from the mouth to the stomach both in health and disease. Specifically, the commensal flora of the proximal, mid-, and distal esophagus varies both in makeup, and relative abundance. In a study of 12 patients under routine surveillance for BE, the proximal esophagus was more similar to the oropharynx in that it had higher concentrations of gram-positive organisms than the distal esophagus[7]. Streptococcus spp. were found throughout the entirety of the esophagus, increasing in relative abundance from the proximal to mid-esophagus and markedly decreasing thereafter in the distal esophagus[7]. Gram-negative organisms included Prevotella and Delftia spp., which overall were more concentrated in the distal esophagus[7]. This is not surprising, because the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) “shell” around gram-negative organisms hardens them to variation in pH, bile salt concentration, proteases, and to some extent, temperature[8-15]. This is why most enteric pathogens are gram negative—they can survive the selection and potentially adverse effects related to proximity to gastric contents. It would be thereby expected that the microbiome becomes much less diverse and increasingly enriched in gram-negative species. Diversity is greatest in the region nearest to the source (oronasal cavity) and with mildest conditions, e.g., saliva/mucous, luminal physiological pH, and moderate physiological temperatures[16,17]. It would be expected to see a gradient toward facultative and obligate anaerobes (probably from the subgingival space) in the esophageal lumen distally towards the stomach. Notably, many bacteria also have increased abundance because of the protective nature of sporulation (e.g., Clostridia spp.) within the harsh surrounding environment[18,19]. Accordingly, the underlying GE pathology appears to be associated with alterations in the composition of this gram positive/gram negative continuum and balance[7].

The biomic differences for esophageal disease is notable. Patients with BE had overall higher levels of Streptococcus spp. in tissue biopsies throughout the entirety of the tract compared to those without the disease. While this appears to be in contrast with the gram-positive/gram-negative imbalance discussed previously, this may be an indirect effect of persistent local irritation caused by immunogenic gram-negative species that facilitates bacterial proliferation and the infiltration of underlying tissue with gram-positive bacteria—of which streptococci are a major part. Whether this is a cause of BE metaplasia or a consequence is unknown. Furthermore, the sharper decrease in overall abundance of Streptococcus spp. from mid- to distal-esophagus is greater in individuals with BE compared to those without metaplasia, which suggests that the overall effect on relative composition of Streptococcus spp. is negative despite an increased tissue prevalence[7].

These findings suggest that an increase in relative abundance of gram-negative flora in the distal esophagus leads to a local inflammatory response which negatively impacts the barrier function. This ultimately leads to tissue proliferation of all flora, including commensal Streptococcus spp. The proximal-distal variation in specific flora changes from healthy to diseased states, in conjunction with the previous GE microbiome subtyping, illustrate the pathological potential of dysbiosis. The emerging data may offer insight into new treatment paradigms focused on microbial alteration which could supplement, and even possibly replace, the need for acid suppression in these disease states.

Factors affecting the composition of the microbiota

The GE microbiome is shaped by the oral cavity, oropharynx, and stomach due to migration of oral bacteria to the esophagus and reflux of gastric microbiota[20]. Recognizably, this varies considerably from person to person, even in the apparently healthy population. In addition to anatomic location, factors that have been noted to alter the EM composition include age, diet, proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use, oral hygiene, and smoking. Studies of these factors have helped provide a framework for understanding the GE microbiota.

Contrary to the philosophy that, for example, the colon is a discrete microbiome that stands alone, we view the whole of the gastrointestinal tract as a contiguous system separated by “gates” imposed by selection pressure driven by factors related to function (pH, osmolarity, proteases, indigenous flora, etc.). That is, a series of discrete “neighborhoods” connected by means of a tube and the assumption that the oronasal cavity if the sole source of inoculum. Prior to weaning, infants do not have established “gates,” and an evolving colonization with what will ultimately become the adult microbiome takes place until the age of approximately three[21]. Thereafter, barring unnatural perturbation, the gastrointestinal neighborhoods are established, stable, and at equilibrium with the host. Unfortunately, humans are pioneers of the unnatural, and a number of behaviors, many now considered essential, systematically undermine the balance. Recognizably, there may be sequential changes associated with age, medication exposures, diet, hygiene, sleep efficiency, and environmental exposures.

Age: Age has an effect on the GE microbiome, although the full significance has not yet been determined[22-25]. During early life, the human colonic microbiome varies greatly. Analysis of the microbial composition of the human colonic microbiome in patients ranging from newborns to 80 years old, and across three distinct geographic locations (United States, Venezuela, and Malawi) has found that the phylogenetic composition fluctuates dramatically during the first 3 years of life before stabilizing into a more stable adult-like composition, regardless of geographic location[26]. Conceivably, a similar dynamic microbial shift exists for the esophagus given the same multifactorial environmental factors in early life, based on mode of delivery (vaginal birth or cesarean section),the type of dietary feeding (breast or formula feeding), as well as the timing of adult food introduction[27,28].

With aging, humans seem to have a less dramatic, but still notable shift in the GE microbiome. Evaluation of the EM of adults of ages 30 years to 60 years, using 16S rRNA-, 18S rRNA-amplicon sequencing, and shotgun sequencing, has found age to be a significant factor driving microbiome composition. Notably, they indicated a positive correlation with age and the relative abundance of Firmicutes such as some Streptococcus spp., including Streptococcus parasanguinis with increasing age[6]. Furthermore, increasing age was inversely correlated with prevalence of Bacteroidetes including Prevotella melaninogenica[6]. To better place this in the context of our current understanding of the GE microbiome and the previously demonstrated community clusters (Streptococcus predominant, Prevotella predominant, and intermediate predominant), this study showed that regardless of disease state, with increased age, there is a more robust microbiome composition and a higher number of gram-positive (Streptococcus parasanguinis) species and a lower number of gram-negative (Prevotella melaninogenica) species[6]. Thus, age may contribute to the different esophageal microbial community types. Despite this, gram-negative proliferation is associated with progression of esophageal disease at all ages[6]. It may be that age may affect and predict a ‘baseline’ microbiome that is incrementally altered by microbial imbalance.

Notably, there is a degenerative effect of aging on esophageal motor function which may play a role in the differences seen in the GE microbiome of the elderly population as esophageal function naturally deteriorates after the age of 40[29]. The presence of GERD has a significant impact on esophageal contraction wave amplitude but not on peristalsis[30]. Accordingly and hypothetically, the mechanistic and functional changes of the esophagus influence the microbiota as a direct or indirect consequence of the aging process.

Diet: Dietary factors influence the colonic microbiome both as an infant (breast vs formula feeding) and as an adult (affecting the colonic microbiome with short-term macronutrient changes)[31-33]. With specific focus on the GE microbiome, dietary intake has been associated with the development of esophageal diseases such as BE, EAC, and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC)[34,35]. In particular, consumption of leafy and cruciferous vegetables, as well as raw fruits is associated with decreased risk of BE and EAC, while red meat intake is associated with increased risk[35].

In early life, breastfeeding, formula feeding and the introduction of solid foods, play a large role in development of the gastrointestinal microbiome[36]. While more specific investigation is needed to evaluate the specific effects on the EM, it is likely that similarities exist in the progression due to the same factors. Human breast milk is predominantly composed of the microbes Corynebacterium, Ralstonia, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Serratia, Pseudomonas, Propionibacterium, Sphingomonas, and Bradyrhizobiaceae in addition to milk oligosaccharides[37-39].

The impact of breastfeeding on the infant gastrointestinal microbiome was highlighted in two studies that found formula-fed infants to have a lower proportion of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus spp. and a higher proportion of Clostridiales and Proteobacteria when compared with breast-fed infants[40]. Furthermore, formula fed infants have lower microbial diversity after the first year of life when compared to breast-fed infants[41]. Several other epidemiologic studies have suggested breastfeeding to have a protective role against asthma, autism, and type 1 diabetes, while also showing a lower association of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases[37,42]. As stated earlier, the phylogenetic composition fluctuates dramatically during the first 3 years of life before evolving into a more mature and stable adult-like configuration[26]. This shift is likely to allow infants to be better equipped to handle processing of a more robust diet.

In adults, the GE microbiome and the relationship to diet is still under investigation. Our focus here will be on diet and its relationship to esophageal disease as a foundation for possible future studies into the GE microbiome role. There are several difficulties, particularly with confounding and study-design issues, when correlating dietary factors in adults with esophageal disease[34]. Thus, most of the existing literature on diet and BE or EAC is based on case-control studies in which minor to moderate inverse associations have been reported with a diet low in fruits and vegetables (green, leafy, and cruciferous vegetables). It has been theorized that fruits and vegetables, which are high in antioxidants, phytosterols, and other substances, may inhibit carcinogenesis by free-radical reduction or by blocking the formation of N-nitroso compounds in the alimentary and respiratory tract[43,44]. Other case-control studies have shown an association with a diet high in red and processed meats and an increased risk of esophageal cancers, likely due to processed meats being a major source of nitrites and nitrosamines[35,45]. Given the potential for multiple interactions between specific macronutrients, other studies have turned to looking at diet-regimens for easier study design. They found that the Mediterranean diet is inversely associated with both BE and EAC, whereas the “Western diet”, high in meat consumption and low in fruits and vegetables, appears to increase the risk of these diseases[46,47]. Although this relationship between dietary intake of fruits, vegetables, as well as red and processed meats, has been more recently implicated, further evaluation is needed in regard to the interaction of these diets and the GE microbiome composition.

A study specifically looking at the relationship of diet with the GE microbiome evaluated patients with high overall fiber vs high fat intake and found that dietary fiber, but not fat intake was associated with a distinct EM[48]. In particular, increasing fiber intake was significantly associated with increasing relative abundance of Firmicutes, including Streptococcus spp., and decreasing relative abundance of gram-negative bacteria overall[48]. Low fiber intake was associated with increased relative abundance of several gram-negative flora, including Prevotella, Neisseria, and Eikenella spp.[48]. These findings offer a potential dietary therapeutic option for prevention or slowing the progression of esophageal disease by decreasing exposure to a higher abundance of gram-negative influence, and thereby reducing the induction of a gram-negative-LPS induced inflammatory cascade.

PPIs: PPIs are the therapeutic first-line treatment for many esophageal disorders such as GERD, erosive esophagitis, and BE. The main mechanistic action of PPIs is to lower acid production at the level of the stomach by inhibiting the hydrogen-potassium ATPase pump, a transmembrane protein responsible for releasing hydrochloric acid into the stomach lumen. PPIs inhibit acid secretion by binding within this domain, promoting a higher gastric pH, and thus increasing the pH of the refluxate[49].

The use of PPIs has been demonstrated to alter both GE and colonic microbiomes, although the full extent is yet unknown. The clearest defined role is reduction of gastric acid, thereby allowing survival of orally ingested organisms to populate the more distal esophagus. This pH-related microflora change may allow propagation of bacterial species that would otherwise not flourish under more acidic conditions. For example, a significant increase in oral microbiome species such as Rothia dentocariosa, Rothia mucilaginosa, Scardovia spp., and Actinomyces spp. in the gut microbiome has been noted following PPI use[50-52].

In the distal esophagus, the effect of PPIs may be more likely to be due to microbial related inflammatory changes, whereas previously attributed to direct acid contact mucosal injury. A study of patients with non-erosive reflux disease (NERD), erosive GERD, and BE compared PPI use vs no use within each respective group and found no change in α diversity or β diversity between PPI and non-PPI users of each group was reported, but composition of specific bacteria taxa at the phylum level was noted[53]. In particular, PPI use was associated with an increase in Firmicutes and Proteobacteria in BE, and a decrease in Bacteroidetes in NERD and reflux esophagitis (RE)[53]. In another study, biopsies taken before and after 8 wk of PPI treatment (lansoprazole 30 mg twice daily) revealed a significant decrease in the gram-negative Comamonadaceae spp. and increased gram-positive Clostridia (Clostridiaceae and Lachnospiraceae spp.) and Actinomycetales (Micrococcaceae and Actinomycetaceae spp.)[54].

These studies offer evidence that PPI use may have effects beyond that of acid suppression. This supports a possible mechanistic role for PPIs altering the GE microbiome, favoring gram-positive bacteria that prefer environments with higher pH. This effect would reduce induction of the Toll-like-receptor (TLR)/inflammatory cascade by gram-negative LPS producing bacteria.

Although their association with GERD is unknown, acid-producing bacteria are found in the esophagus and oral cavity. The use of PPIs may directly target the proton pumps (P-type ATPase enzymes) of these bacteria (notably Streptococcus pneumoniae and Helicobacter pylori)[55]. Further studies are warranted to determine if these bacteria are a causal factor of GERD by directly producing acid, which are in turn inhibited by PPIs. In addition, PPI use may indirectly change the natural bacterial flora in non-gastric tissues that express H+/K+-ATPases by shutting down proton pumps[55,56].

PPIs may also reduce inflammation apart from direct acid suppression. In esophageal squamous epithelial cells, omeprazole has been shown to inhibit interleukin (IL)-8 expression by blocking the nuclear translocation of a nuclear factor-kappa beta (NF-kB) subunit and the binding of AP-1 subunits to the IL-8 promoter[56]. IL-8 is an inflammatory mediator that has been implicated in the GERD, BE, and EAC pathways. Increased expression of LPS from gram-negative bacteria, and subsequent activation of the TLR-4-NF-κB pathway are associated with expression of downstream mediators such as IL-8 and cyclooxygenase (COX)-2[57]. The levels of both are directly correlated with transition from metaplasia to dysplasia in BE[57]. Thus, if PPI therapy has an effect on IL-8 expression by blocking NF-kb and AP-1, there may be a role for therapeutic use outside of direct acid suppression.

Oral hygiene: Oral hygiene is thought to play a vital role in the GE microbiome. Bacteria found in the oral cavity can migrate distally via deglutition[20]. The role of oral microbiota in colonizing the esophagus, and becoming part of the commensal GE microbiota, remains uncertain.

Maintained oral hygiene is associated with a higher proportion of gram-positive cocci and rods, mostly comprised of Streptococcus spp., which contrasts with those with poor oral hygiene showing shifts to a higher proportion of anaerobic gram-negative bacteria such as Prevotella spp.[58]. The oral microbiome shift to a more gram-negative dominant flora may have distal effects of LPS-inducing TLRs and activation of an inflammatory cascade in the esophagus as described previously. It is also unclear whether antibiotic mouthwashes damage an otherwise healthy microbiome. Further research is needed to better define the relationship between oral hygiene and the GE microbiome.

One recent population-based, case-control study reported that poor oral health was associated with an increased risk of ESCC[59]. More specifically, they found that tooth loss was associated with a moderately significant increased risk of esophageal cancer and that brushing once per day or less was associated with an 80% increased risk of developing ESCC in this population. They propose that tooth brushing influences the balance of microorganisms by directly removing plaque, food residue, and carcinogenic products of tobacco and alcohol. Accordingly, this affects the levels of inflammation and/or production of the carcinogenic by-products of nitrosamines and acetaldehyde. While this is currently theoretical, given the proximity of the oral cavity to the distal esophagus, it is reasonable that oral hygiene would have downstream effects on the GE microbiome and esophageal disease as well as perhaps on intestinal microbial mediated disease as well.

Smoking: Up to 20% of United States adults use a tobacco product, and tobacco’s effect on the GE microbiome is uncertain[60]. Esophageal balloon procured cytology found that current smoking was associated with an increase in both α and β diversity of the esophagus[61]. It is suspected that the increase is due to smoking-related immunosuppression, permitting novel bacteria to colonize the upper gastrointestinal tract[61]. The study also found two anaerobic bacteria, Dialister invisus and Megasphaera micronuciformis, are more commonly detected in current smokers[61]. Increased α and β diversity after smoking exposure may also be a result of biofilm formation[62]. There is some evidence that cigarette smoking induces staphylococcal biofilm formation in an oxidant-dependent manner by increasing fibronectin binding protein-A. This leads to increased binding of staphylococci to fibronectin and increased adherence to human cells[62].

Smoking exposure can affect a wide range of human physiologic processes by inducing a proinflammatory state, increasing cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8 all while decreasing anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10[63]. Further investigation into the EM and its relationship to smoking and the development of disease are needed.

Bacteriocins

Bacteriocins are ribosomal derived peptides produced by microorganisms colonizing the gastrointestinal tract that are thought to inhibit competitive flora, thereby out-competing other pathogens. Additionally, in humans, bacteriocins are thought to maintain barrier function, partake in immune modulation, have direct antimicrobial activity, and also exhibit anti-neoplastic activity[64]. Bacteriocins’ diverse functional role is reflected in their wide-ranging bactericidal properties, amino acid sequence and peptide structures, bacteriocin operon type, and different molecular weights and charges[65,66].

In a normal, healthy individual, the gut-blood barrier is responsible for maintaining homeostasis between the bloodstream and the gastrointestinal tract, which ultimately regulates water and nutrient absorption[67]. Along with a growing interest of the GE microbiome and its relationship with the intestinal barrier, recent in vitro studies have reported that the size and properties of bacteriocins allow them to cross this gut-blood barrier[64,68]. The size and charge contribute to bacteriocin movement across membranes and barriers and account for the large role in different physiologic mechanisms[64].

The bacteriocins in the gastrointestinal tract also have specific, potent antimicrobial properties[69,70]. This antibacterial property makes it essential in maintaining and affecting the composition of the local microbiome. The anti-neoplastic role of bacteriocins is still an area warranting further investigation. In vitro studies evaluating the effect of nisin have shown that bacteriocin may trigger apoptosis in head, neck, and squamous cell carcinoma, effectively reducing the size of tumor xenografts[71,72].

Defensins

Defensins are small host-derived polypeptide molecules of host-origin that play a role in innate immunity with both direct and indirect bactericidal effects. They serve a similar purpose to bacteriocins, but are eukaryote derived[73]. Human defensins are typically classified into α-defensins, which are mainly neutrophil-derived, and β-defensins, which are mainly epithelial cell-derived. Defensin expression is typically inducible through cellular exposure to bacterial products such as LPS or cytokines, which include TNF and IL-1[73]. Binding of defensins can lead to direct bacterial cell membrane disruption. The positive charge of some defensins is attracted to the negative components of bacterial capsules, leading to oligomerization and pore formation[74]. Alternately, defensin binding can stimulate recruitment of the adaptive immune response[73].

Defensins have been demonstrated to play a role in normal gut-microbe interactions. Loss of human β-defensin (hBD) 1 and hBD3 is associated with progression of EoE, and this may be a result of unmitigated microbe-immune interactions[75]. Uncontrolled defensin production may also negatively impact gut health. The production of hBD5 by metaplastic Paneth cells, can lead to a loss of E-cadherin, and thus inhibit cell adhesion[76]. This loss of structural integrity has been associated with progression of BE[76].

Similar to bacteriocins, modification of defensin expression or structure may provide a therapeutic venue for alteration of the commensal microbiome. Chimeric variants of defensins have been explored as possible antimicrobial agents, but this potential treatment modality is still in early stages of exploration, and further work is needed to evaluate their therapeutic safety and efficacy[77].

MECHANISMS OF DYSBIOSIS

Initial paradigms for dysbiosis

Dysbiosis is a term that encompasses a change in the composition of commensal microbiome relative to that found in healthy individuals[78]. When distinguishing the biome of a normal healthy esophagus to dysbiotic disease states such as GERD, EE, BE, or EAC, it is evident that dysbiosis may precede inflammation. Thus, the composition of the microbiota may play a large role in the downstream events[79]. Gram-negative bacterial products activate TLRs that are present on the esophageal endothelial cells causing an inflammatory cascade which leads to downstream LES relaxation[79]. Prevotella, which are found in greater abundance in the dysbiotic distal esophagus, have been shown to be a key producer of LPS that contributes to TLR activation[6]. The activation results in chemokine-induced production of nitric oxide and COX-2, which may promote LES relaxation and decrease gastric emptying[80].

DYSBIOSIS IN DISEASE STATES

GERD

GERD is an inflammatory disease state that is most commonly caused by inappropriate transient relaxation or secondly, by a chronically decreased tonicity of the lower esophageal sphincter[81]. It is further classified into two large phenotypes: RE and NERD, as determined by endoscopy. Additionally, there is a category of uninvestigated GERD wherein treatment is initiated without direction from an endoscopic evaluation[82].

Inflammatory pathogenesis of GERD: Classically, GERD has been described as the result of reflux of gastric acid and/or duodenal bile salts, causing direct chemical mediated mucosal injury and inflammation[83]. The majority of patients that present with clinical symptoms of GERD have no endoscopic evidence of reflux, suggesting alternative pathophysiologic pathways. An animal study demonstrated that RE does not develop as a chemical injury starting at the epithelial surface but rather, begins with a submucosal infiltration by lymphocytes that later progresses upward to the epithelial surface[84]. Subsequent work analyzed human esophageal squamous cell lines exposed to acidified bile salts and found evidence that reflux did not directly damage the mucosal esophagus, but instead stimulated epithelial cells and led to subepithelial cytokine-mediated and retrograde directed mucosal damage of the tissue[85].

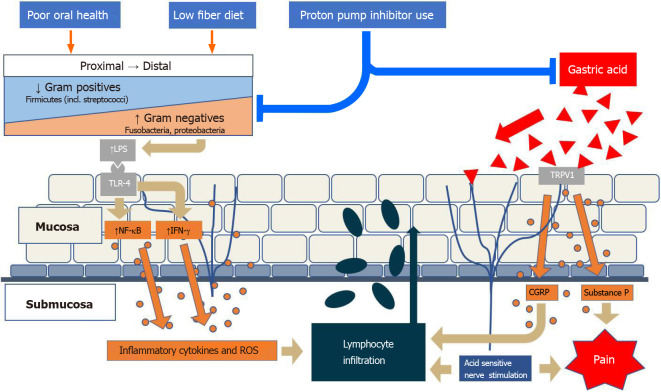

Acid exposure is believed to contribute to mucosal expression of inflammatory markers, including IL-8, as well as several other chemokines, that promote local migration of leukocytes, mainly neutrophils[85]. This is done through activation of transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 on epithelial cells and neurons, which results in calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and substance P expression[86]. Both CGRP and neutrophil activation initiate a cascade of cytokine expression, leading to local submucosal inflammation as well as hydrogen peroxide production as well as further immune cell, including lymphocytic proliferation into the mucosa (Figure 1). Peroxide-mediated smooth muscle relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter further contributes to reflux[87].

Figure 1.

Environmental factors alter the local esophageal microbiome, which normally has a gram-positive to gram-negative gradient, towards increased proportion of gram-negatives. Activation of Toll-like-receptor-4 by gram-negative lipopolysaccharide leads towards an inflammatory cascade that results in lymphocyte infiltration. In addition, gastric acid activates transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 on local nerve fibers and results in calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P expression, which contributes to the local inflammatory response as well as pain. LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; TLR: Toll-like-receptor; NF-κB: nuclear factor-kappa beta; IFN: Interferon; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; TRPV1: Transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1; CGRP: Calcitonin gene-related peptide.

Role of the microbiome in GERD: Gram-negative bacterial products, mainly LPS, bind to TLR-4, which stimulates IL-18 production, and initiates a cascade of IL and TNF production. This leads to downstream effects including lower esophageal sphincter relaxation as well as decreased gastric motility[1].

It has been theorized that the bacterial biofilm may be involved in the pathogenesis of GERD[88]. Biofilm is an organized community of microbes that produce protective factors and adhesion molecules which enhance the survival of the local microbial community. Biofilm has been implicated in the pathogenesis of a variety of disease states elsewhere in the gastrointestinal tract, notably in the oral cavity and colon, while the extent of contribution to esophageal disease is still unclear[89-91].

Compositional variation in the localized microbiome may help explain the mechanistic and clinical difference between the two phenotypes of GERD. A recent study found distinct microbiota in patients with NERD when compared with controls and RE subjects. The NERD microbiota composition shifted towards Proteobacteria (Neisseria oralis and Moraxella spp.) and Bacteroidetes (Bacteroides uniformis, Capnocytophaga spp., and Prevotella pallens), and away from Fusobacteria (Leptotrichia) and Actinobacteria (Rothia)[53]. Several Firmicutes genera were reduced in NERD (Peptococcus and Moryella). An increased abundance of Dorea spp., however, resulted in an overall higher Firmicutes composition compared with controls[53]. The same study speculated that the increase in sulfate-reducing Proteobacteria spp. and Bacteroidetes spp. along with hydrogen producing Dorea spp. is associated with a mechanistic role in visceral hypersensitivity present in NERD[53]. Alternatively, patients with RE have a decrease in Firmicutes (Mogibacterium spp., Streptococcus infantis, Solobacterium moorei) and increase in gram-negative Fusobacteria (Leptotrichia spp.) and Proteobacteria (Marivita, Neisseria, and Mesorhizobium spp.)[53].

The compositional changes in esophageal flora can also occur as a response to environmental factors. High-fat diet has been heavily associated with localized mucosal inflammatory changes in murine models[92]. It is theorized that alterations in the luminal microenvironment seen with high-fat diet leads to increased gut-epithelial interactions and drives progression of the inflammatory response. In addition, these dietary changes have been demonstrated to contribute to colonic increased colonic Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio, which is associated with obesity and an inflammatory response characterized by expression of chemokine IL-8[92]. Other dietary factors, including consumption of insoluble carbohydrates, can contribute to reflux through effect on gastric and esophageal tone. Colonic bacterial metabolism of carbohydrates into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) is associated with increase in peptide YY and oxyntomodulin, which inhibit gastric motility and LES function[93].

BE

BE is a disease state characterized by stratified squamous to columnar metaplasia of the distal esophageal epithelium, and is typically associated with longstanding GERD[94,95]. The incidence of BE has increased since the mid-20th century, which is thought to be related to population-level changes in EM composition following the introduction of antibiotics[96]. The activation of the LPS-TLR4-NF-κB pathway through dysbiotic changes may contribute to inflammation and malignant transformation[3].

Inflammatory pathogenesis of BE: The inflammatory-mediated model of reflux-related inflammation seen in GERD is also present in BE[97]. There are, however, several specific dysbiotic changes that contribute to inflammatory mediated metaplasia as well. Murine models of BE demonstrated localized cytokine expression, especially in the distal esophagus, which can lead to an inflammatory response in gastric stem cells, ultimately promoting columnar epithelial formation[98]. Additionally, the same pro-inflammatory response associated with LPS and TLR-4 binding may be more notable in the distal esophagus with increased gram negative presence, and specifically contributes to metaplastic transformation[80].

Pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1b, has been shown to be highly expressed in BE. The precursor for IL-1b necessitates proteolytic cleavage by caspase-1[98]. Caspase-1 also allows apoptosis of cells which can elicit further inflammation[99]. The functional role of caspase-1 is activated by inflammasomes which contain pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs). The PRR captures particular pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) from microbes and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) from injured cells[100]. Once the PRR recognizes a certain PAMP or DAMP, a large complex of inflammasomes activates caspase-1 which initiates the inflammatory response pathway. One study demonstrated that LPS in Barrett’s epithelial cells was shown to prime and activate NOD-like receptor protein 3 inflammasomes and caused a cascade of pro-inflammatory responses and induced apoptosis[101]. These data suggest that BE is perpetuated through a chronic inflammatory response from localized cytokine release which is initiated at the molecular level of the microbiome and related mucosal cell responses.

Role of the microbiome in BE: Patients with BE have been found to have both similarities and distinct features in EM profile when compared to those with GERD[102]. Using the original clustering model, Type I to Type II microbiome transition likely contributes to local inflammation[103,104]. More recently, it has been demonstrated that specific flora plays a contributing role in its pathogenesis. Fusobacteria, Neisseria spp., and Campylobacter spp. have been linked to BE when compared to controls[105]. Additionally, comparison of metaplastic tissue to adjacent normal areas demonstrates decreased α diversity and decreased prevalence of Bacteroidetes including Prevotella spp.[106]. Distinct compositional differences in specific phyla occur along the NERD, BE, and EAC pathway. While Proteobacteria are massively over-represented in NERD (Bacteroidetes to a lesser extent), microbiota in in BE and RE demonstrate increase in Fusobacteria and Proteobacteria. The transition to the EAC microbiome demonstrates an increase in Firmicutes, which are decreased in NERD and BE[53]. This increase may mirror the increase in Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio that is seen in obesity and colorectal adenocarcinoma, as impaired fermentation by Bacteroidetes spp. of fiber to anti-inflammatory SCFAs may contribute to the local inflammatory cascade.

EAC

Inflammatory pathogenesis: The pathogenesis of EAC has been attributed to a combination of genetic predisposition as well as environmental factors[107]. The majority of cases are associated with environmental triggers such as smoking, obesity, and GERD/BE[108]. The incidence of EAC in BE has been clearly established, albeit more recent data suggests lower rates, more in the range of 0.1-0.2%[109].

Role of the microbiome in EAC: All stages in the GERD-BE-EAC pathway have commonalities in composition of local flora. The change from type I to type II EM is generally associated with the initiation of reflux-associated inflammatory processes that are present in GERD and BE, and persist in EAC. The subsequent activation of the LPS-TLR4 cascade leads to NF-kB activation, which further increases COX-2 production[3]. COX-2 elevation is associated with the progression of BE to high-grade dysplasia[80]. More recent data, however, has identified specific floral changes in relative abundance that are associated with the progression from BE high-grade dysplasia and EAC. Patients with dysplastic disease have increased abundance of Proteobacteria and decreased Firmicutes[110]. Notably, Streptococcus spp. abundance is reportedly unchanged between non-dysplastic BE and high-grade dysplasia/EAC, suggesting that variation in Streptococcus spp. may not play a role in carcinogenesis[110].

The composition of the EM in EAC is closely linked to that of the oral cavity, with aboral movement of flora being theorized as one mechanism for compositional changes[111]. Specifically, oral flora such as Treponema denticola, Streptococcus mitis, and Streptococcus anginosus are associated with esophageal carcinogenesis[112]. While the overall abundance of Streptococci appears unchanged in between non-dysplastic BE and EAC, it is possible that individual species may have varied abundance.

In addition to pathogenic linkage between the oral and esophageal flora, compositional changes that are associated with decreased adenocarcinoma risk are also shared. Notably, the abundance of Bifidobacteria spp., Bacteroides spp., Fusobacteria spp., Veillonella spp., Lactobacillus spp., and Staphylococcus spp. is associated with adenocarcinoma risk[88,106]. Leptotrichia spp. have been demonstrated to be a specific genus linked to EAC. In addition, reduction in some species, including Neisseria and Streptococcus pneumoniae decreased risk of progression to cancer[113,114].

ESCC

Inflammatory pathogenesis: ESCC is more common than EAC in regions such as Asia and South America[115]. Classically, ESCC has been associated with environmental exposures, including tobacco, alcohol, and hot-drink consumption, as well as genetic predisposition[116]. Other risk factors, such as poor oral health, have been linked to esophageal squamous dysplasia, a precursor for ESCC[117]. Exposure to various environmental triggers may directly stimulate epithelial expression of inflammatory markers, or may indirectly lead to proinflammatory state through changes in the microbiome[118].

Role of the microbiome in ESCC: Evaluation of microbiomes of patient’s with ESCC demonstrates specific changes when compared to healthy controls, notably increased in proportion of Actinomyces spp. and Atopobium spp., and decrease in Fusobacterium spp., and Porphyromonas spp.[118]. Generally, there is also a decrease in bacterial diversity, and increase in interpersonal compositional variation, suggestive that the dysbiotic state is not stable[118,119]. As with EAC, there is a close association with oral cavity disease/dysbiosis and ESCC. Decrease diversity of oral flora is associated with ESCC, as aboral movement of microbes likely disrupts the normal esophageal microbial composition and contributes to dysbiosis[119].

Specific environmental agents may directly contribute to dysbiosis through nutrient availability. Tobacco smoking is associated with many oral microbiome changes that have some overlap with dysbiosis in ESCC. Particularly, increases in flora within phylum Actinobacteria and genera Atopobium and Prevotella, and decreases in Fusobacteria spp. have been reported[120]. Alcohol consumption may negatively affect epithelial barrier function that normally modulates epithelium-microbe interaction[121]. It may additionally contribute to local dysbiosis through metabolism by local flora into toxic metabolites such as acetaldehyde. Alcohol consumption is associated with colonic microbial changes that are reversible with probiotics, suggesting plasticity of the microbiome[122]. A combination of dysbiosis and epithelial dysfunction may contribute to endotoxemia and systemic inflammatory response[123], which may play a role in carcinogenesis.

Microbiome changes may also play a prognostic role in ESCC. Increases in phyla Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Spirochaetes, and decrease in Proteobacteria are associated with lymph node spread, with Streptococcus spp. and Prevotella spp. being specifically indicated[124].

EoE

Inflammatory pathogenesis: EoE is a chronic immune mediated disease of the esophagus characterized by marked eosinophilic infiltration in response to T helper type 2 (Th2) cells[125]. Factors such as genetics, environment, allergens, and microbiome have been identified as triggers of the chronic disease[126]. Several genes have been identified as contributors to EoE, which include thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), calpain 14 (CAPN14), EMSY, LRRC32, STAT6, and ANKRD27[126]. Among the identified genes, TSLP appears to be the major contributor as it is activated by epithelial cells and induces Th2 differentiation[127]. Different allergens also induce an inflammatory cascade which increases inflammatory markers such as IL-5 and IL-13, which introduce a potential inflammatory path of EoE[126]. In addition to the genetics and environmental exposure, the microbiome of the esophagus has recently emerged as a potentially key mediator in the pathogenesis of EoE.

Role of the microbiome: Analysis of the microbiome in EoE has reported an increase of proteobacteria, specifically Neisseria spp. and Corynebacterium spp., in children with active EoE[128]. This study, in conjunction with the evidence of altered gut microbiome with infantile antibiotic use and Cesarean section delivery, further supports that dysbiosis in the human microbiome has a role in EoE[129,130]. Analysis by an esophageal string test to evaluate the microbiome of children and adults with active EoE found a greater abundance of Haemophilus spp. in active EoE[131]. Notably, there was also a decrease in specific taxa of Clostridia that had been observed in patients with active EoE[132]. In antibiotic treated mice, the addition of Clostridia-containing microbiota prevents sensitization to a specific food allergen. Induction of IL-22 by RAR-related orphan receptor innate lymphoid cells and T cells in the intestinal lamina propria are proposed as the mechanism of blocking sensitization to a food allergen[133]. The recent evidence suggests that the EM may be involved in the pathogenesis of EoE, and may represent new treatment approaches.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THERAPY

As previously discussed with modification of other environmental exposures, additional therapeutic options such as prebiotics, probiotics, and antibiotics have been investigated to reduce dysbiosis by directly or indirectly improving the gram-positive to gram-negative ratio for esophageal diseases. Although there is increasing evidence of altering dysbiosis utilizing these therapies in other gastrointestinal diseases, further research is needed in specific esophageal diseases.

Prebiotics

Supplements which increase the concentration of beneficial flora have been investigated. Lactobacillus spp., which are found in the esophagus, metabolize maltosyl-isomaltooligosaccharides (MIMO), thereby enhancing the populations of favorable gram-positive organisms. Daily ingestion of MIMO has been reported to improve or eliminate symptoms in chronic GERD patients[134]. An expanded comprehensive evaluation of this promising approach is needed. A tolerability study is underway (NCT04491734), and a comprehensive multicenter randomized placebo-controlled study will begin in early 2021. Sugarcane flour has also been evaluated as a prebiotic with some benefit seen on one study[135]. The proposed mechanism for benefit is slower fermentation and thus greater luminal availability compared to traditional fiber-containing products[135].

Probiotics

Probiotics add bacterial strains as dietary supplementation, attempting to improve the gut flora composition to a preferential state. Probiotics containing Lactobacilli spp. and Bifidobacteria spp. have been evaluated and demonstrated relief of GERD symptoms[136-140]. However, long term effects and histological benefit have not been studied, and more recent guidelines have suggested no evidence based recommendation for routine use[141]. Further investigation is needed to evaluate potential efficacy of probiotics in esophageal diseases.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics are a potential therapeutic option for direct modification of the EM, and are widely used in the treatment of gastrointestinal infectious diseases. Antibiotics with focused intraluminal bioavailability have been used in treating small-intestinal bacterial overgrowth, hepatic encephalopathy, and Clostridium difficile infections[142-144]. There is, however, no evidence of the effectiveness of antibiotic use for esophageal dysbiosis in GERD, BE, or EAC.

Bacteriocins

Bacteriocins facilitate competition between local and foreign microbes, direct microbial properties, have potential for crossing the gut-blood barrier, and have antineoplastic properties[64]. Bacteriocin-based drug therapy, whether in the form of targeted drug therapy via encapsulation or attachment of bacteriocins to macromolecules, metals, or polymer-based nanoparticles, remains an area of ongoing investigation[145].

CONCLUSION

The EM plays a major role in the pathogenesis of esophageal disease. Various factors can affect the composition of the commensal flora, which may lead to dysbiosis and ultimately result in esophageal diseases. The dysbiosis likely contributes to a pro-inflammatory, cytokine-mediated state that starts in the submucosa. The pathogenic consequence, affecting the esophageal mucosa, has previously been attributed to caustic acid mucosal injury, but now appears to be multifactorial, with the EM playing a major role. Specific flora has been more recently identified that may play a pathogenic role in this process. Several potential methods for therapeutic alteration of microbiome exist, including prebiotics, probiotics, antibiotics, and bacteriocin based therapies. The prebiotic treatment data is particularly promising as directed EM modification for effective disease treatment.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interests or financial disclosures relevant to this manuscript.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: February 2, 2021

First decision: February 27, 2021

Article in press: April 14, 2021

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Haruma K, Urabe M S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

Contributor Information

Steve M D'Souza, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA 23502, United States.

Kevin Houston, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA 23502, United States.

Lauren Keenan, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA 23502, United States.

Byung Soo Yoo, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA 23502, United States.

Parth J Parekh, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA 23502, United States.

David A Johnson, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA 23502, United States. dajevms@aol.com.

References

- 1.D’Souza SM, Cundra LB, Yoo BS, Parekh PJ, Johnson DA. Microbiome and Gastroesophageal Disease: Pathogenesis and Implications for Therapy. Ann Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;4:20–33. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corning B, Copland AP, Frye JW. The Esophageal Microbiome in Health and Disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2018;20:39. doi: 10.1007/s11894-018-0642-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lv J, Guo L, Liu JJ, Zhao HP, Zhang J, Wang JH. Alteration of the esophageal microbiota in Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:2149–2161. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i18.2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rinninella E, Raoul P, Cintoni M, Franceschi F, Miggiano GAD, Gasbarrini A, Mele MC. What is the Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition? Microorganisms. 2019;7 doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7010014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang L, Lu X, Nossa CW, Francois F, Peek RM, Pei Z. Inflammation and intestinal metaplasia of the distal esophagus are associated with alterations in the microbiome. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:588–597. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deshpande NP, Riordan SM, Castaño-Rodríguez N, Wilkins MR, Kaakoush NO. Signatures within the esophageal microbiome are associated with host genetics, age, and disease. Microbiome. 2018;6:227. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0611-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okereke I, Hamilton C, Reep G, Krill T, Booth A, Ghouri Y, Jala V, Andersen C, Pyles R. Microflora composition in the gastrointestinal tract in patients with Barrett's esophagus. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11:S1581–S1587. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2019.06.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y, Powell DA, Shaffer SA, Rasko DA, Pelletier MR, Leszyk JD, Scott AJ, Masoudi A, Goodlett DR, Wang X, Raetz CR, Ernst RK. LPS remodeling is an evolved survival strategy for bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:8716–8721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202908109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Audia JP, Webb CC, Foster JW. Breaking through the acid barrier: an orchestrated response to proton stress by enteric bacteria. Int J Med Microbiol. 2001;291:97–106. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lund P, Tramonti A, De Biase D. Coping with low pH: molecular strategies in neutralophilic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2014;38:1091–1125. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Begley M, Gahan CG, Hill C. The interaction between bacteria and bile. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2005;29:625–651. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown AD, Turner HP. Membrane stability and salt tolerance in gram-negative bacteria. Nature. 1963;199:301–302. doi: 10.1038/199301a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CHRISTIAN JH, WALTHO JA. The sodium and potassium content of non-halophilic bacteria in relation to salt tolerance. J Gen Microbiol. 1961;25:97–102. doi: 10.1099/00221287-25-1-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joo HS, Fu CI, Otto M. Bacterial strategies of resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2016;371 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breijyeh Z, Jubeh B, Karaman R. Resistance of Gram-Negative Bacteria to Current Antibacterial Agents and Approaches to Resolve It. Molecules. 2020;25 doi: 10.3390/molecules25061340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong L, Yin J, Zhao J, Ma SR, Wang HR, Wang M, Chen W, Wei WQ. Microbial Similarity and Preference for Specific Sites in Healthy Oral Cavity and Esophagus. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1603. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwab F, Gastmeier P, Meyer E. The warmer the weather, the more gram-negative bacteria - impact of temperature on clinical isolates in intensive care units. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tetz G, Tetz V. Introducing the sporobiota and sporobiome. Gut Pathog. 2017;9:38. doi: 10.1186/s13099-017-0187-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicholson WL, Munakata N, Horneck G, Melosh HJ, Setlow P. Resistance of Bacillus endospores to extreme terrestrial and extraterrestrial environments. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:548–572. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.3.548-572.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bassis CM, Erb-Downward JR, Dickson RP, Freeman CM, Schmidt TM, Young VB, Beck JM, Curtis JL, Huffnagle GB. Analysis of the upper respiratory tract microbiotas as the source of the lung and gastric microbiotas in healthy individuals. mBio. 2015;6:e00037. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00037-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanaka M, Nakayama J. Development of the gut microbiota in infancy and its impact on health in later life. Allergol Int. 2017;66:515–522. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Claesson MJ, Cusack S, O'Sullivan O, Greene-Diniz R, de Weerd H, Flannery E, Marchesi JR, Falush D, Dinan T, Fitzgerald G, Stanton C, van Sinderen D, O'Connor M, Harnedy N, O'Connor K, Henry C, O'Mahony D, Fitzgerald AP, Shanahan F, Twomey C, Hill C, Ross RP, O'Toole PW. Composition, variability, and temporal stability of the intestinal microbiota of the elderly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108 Suppl 1:4586–4591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000097107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feres M, Teles F, Teles R, Figueiredo LC, Faveri M. The subgingival periodontal microbiota of the aging mouth. Periodontol 2000. 2016;72:30–53. doi: 10.1111/prd.12136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Odamaki T, Kato K, Sugahara H, Hashikura N, Takahashi S, Xiao JZ, Abe F, Osawa R. Age-related changes in gut microbiota composition from newborn to centenarian: a cross-sectional study. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16:90. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0708-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conlon MA, Bird AR. The impact of diet and lifestyle on gut microbiota and human health. Nutrients. 2014;7:17–44. doi: 10.3390/nu7010017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Baldassano RN, Anokhin AP, Heath AC, Warner B, Reeder J, Kuczynski J, Caporaso JG, Lozupone CA, Lauber C, Clemente JC, Knights D, Knight R, Gordon JI. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 2012;486:222–227. doi: 10.1038/nature11053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dominguez-Bello MG, Costello EK, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Fierer N, Knight R. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:11971–11975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002601107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holgerson PL, Vestman NR, Claesson R, Ohman C, Domellöf M, Tanner AC, Hernell O, Johansson I. Oral microbial profile discriminates breast-fed from formula-fed infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:127–136. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31826f2bc6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gregersen H, Pedersen J, Drewes AM. Deterioration of muscle function in the human esophagus with age. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:3065–3070. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0278-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gutschow CA, Leers JM, Schröder W, Prenzel KL, Fuchs H, Bollschweiler E, Bludau M, Hölscher AH. Effect of aging on esophageal motility in patients with and without GERD. Ger Med Sci. 2011;9:Doc22. doi: 10.3205/000145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshioka H, Iseki K, Fujita K. Development and differences of intestinal flora in the neonatal period in breast-fed and bottle-fed infants. Pediatrics. 1983;72:317–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Le Huërou-Luron I, Blat S, Boudry G. Breast- v. formula-feeding: impacts on the digestive tract and immediate and long-term health effects. Nutr Res Rev. 2010;23:23–36. doi: 10.1017/S0954422410000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, Ling AV, Devlin AS, Varma Y, Fischbach MA, Biddinger SB, Dutton RJ, Turnbaugh PJ. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505:559–563. doi: 10.1038/nature12820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dawsey SM, Fagundes RB, Jacobson BC, Kresty LA, Mallery SR, Paski S, van den Brandt PA. Diet and esophageal disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1325:127–137. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kubo A, Corley DA, Jensen CD, Kaur R. Dietary factors and the risks of oesophageal adenocarcinoma and Barrett's oesophagus. Nutr Res Rev. 2010;23:230–246. doi: 10.1017/S0954422410000132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dong TS, Gupta A. Influence of Early Life, Diet, and the Environment on the Microbiome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:231–242. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.08.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pannaraj PS, Li F, Cerini C, Bender JM, Yang S, Rollie A, Adisetiyo H, Zabih S, Lincez PJ, Bittinger K, Bailey A, Bushman FD, Sleasman JW, Aldrovandi GM. Association Between Breast Milk Bacterial Communities and Establishment and Development of the Infant Gut Microbiome. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:647–654. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rudloff S, Kunz C. Milk oligosaccharides and metabolism in infants. Adv Nutr. 2012;3:398S–405S. doi: 10.3945/an.111.001594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim SY, Yi DY. Analysis of the human breast milk microbiome and bacterial extracellular vesicles in healthy mothers. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52:1288–1297. doi: 10.1038/s12276-020-0470-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bezirtzoglou E, Tsiotsias A, Welling GW. Microbiota profile in feces of breast- and formula-fed newborns by using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) Anaerobe. 2011;17:478–482. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bokulich NA, Chung J, Battaglia T, Henderson N, Jay M, Li H, D Lieber A, Wu F, Perez-Perez GI, Chen Y, Schweizer W, Zheng X, Contreras M, Dominguez-Bello MG, Blaser MJ. Antibiotics, birth mode, and diet shape microbiome maturation during early life. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:343ra82. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad7121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brugman S, Visser JT, Hillebrands JL, Bos NA, Rozing J. Prolonged exclusive breastfeeding reduces autoimmune diabetes incidence and increases regulatory T-cell frequency in bio-breeding diabetes-prone rats. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2009;25:380–387. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steinmetz KA, Potter JD. Vegetables, fruit, and cancer. II. Mechanisms. Cancer Causes Control. 1991;2:427–442. doi: 10.1007/BF00054304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mirvish SS, Wallcave L, Eagen M, Shubik P. Ascorbate-nitrite reaction: possible means of blocking the formation of carcinogenic N-nitroso compounds. Science. 1972;177:65–68. doi: 10.1126/science.177.4043.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jakszyn P, Gonzalez CA. Nitrosamine and related food intake and gastric and oesophageal cancer risk: a systematic review of the epidemiological evidence. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4296–4303. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i27.4296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen H, Ward MH, Graubard BI, Heineman EF, Markin RM, Potischman NA, Russell RM, Weisenburger DD, Tucker KL. Dietary patterns and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and distal stomach. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:137–144. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kubo A, Levin TR, Block G, Rumore GJ, Quesenberry CP Jr, Buffler P, Corley DA. Dietary patterns and the risk of Barrett's esophagus. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:839–846. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nobel YR, Snider EJ, Compres G, Freedberg DE, Khiabanian H, Lightdale CJ, Toussaint NC, Abrams JA. Increasing Dietary Fiber Intake Is Associated with a Distinct Esophageal Microbiome. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2018;9:199. doi: 10.1038/s41424-018-0067-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Katelaris PH. Proton pump inhibitors. Med J Aust. 1998;169:208–211. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1998.tb140224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Imhann F, Bonder MJ, Vich Vila A, Fu J, Mujagic Z, Vork L, Tigchelaar EF, Jankipersadsing SA, Cenit MC, Harmsen HJ, Dijkstra G, Franke L, Xavier RJ, Jonkers D, Wijmenga C, Weersma RK, Zhernakova A. Proton pump inhibitors affect the gut microbiome. Gut. 2016;65:740–748. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jackson MA, Goodrich JK, Maxan ME, Freedberg DE, Abrams JA, Poole AC, Sutter JL, Welter D, Ley RE, Bell JT, Spector TD, Steves CJ. Proton pump inhibitors alter the composition of the gut microbiota. Gut. 2016;65:749–756. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Macke L, Schulz C, Koletzko L, Malfertheiner P. Systematic review: the effects of proton pump inhibitors on the microbiome of the digestive tract-evidence from next-generation sequencing studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:505–526. doi: 10.1111/apt.15604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou J, Shrestha P, Qiu Z, Harman DG, Teoh WC, Al-Sohaily S, Liem H, Turner I, Ho V. Distinct Microbiota Dysbiosis in Patients with Non-Erosive Reflux Disease and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. J Clin Med. 2020;9 doi: 10.3390/jcm9072162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amir I, Konikoff FM, Oppenheim M, Gophna U, Half EE. Gastric microbiota is altered in oesophagitis and Barrett's oesophagus and further modified by proton pump inhibitors. Environ Microbiol. 2014;16:2905–2914. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vesper BJ, Jawdi A, Altman KW, Haines GK 3rd, Tao L, Radosevich JA. The effect of proton pump inhibitors on the human microbiota. Curr Drug Metab. 2009;10:84–89. doi: 10.2174/138920009787048392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huo X, Zhang X, Yu C, Zhang Q, Cheng E, Wang DH, Pham TH, Spechler SJ, Souza RF. In oesophageal squamous cells exposed to acidic bile salt medium, omeprazole inhibits IL-8 expression through effects on nuclear factor-κB and activator protein-1. Gut. 2014;63:1042–1052. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Konturek PC, Nikiforuk A, Kania J, Raithel M, Hahn EG, Mühldorfer S. Activation of NFkappaB represents the central event in the neoplastic progression associated with Barrett's esophagus: a possible link to the inflammation and overexpression of COX-2, PPARgamma and growth factors. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:1075–1083. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000037790.11724.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Socransky SS, Haffajee AD. Periodontal microbial ecology. Periodontol 2000. 2005;38:135–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen X, Yuan Z, Lu M, Zhang Y, Jin L, Ye W. Poor oral health is associated with an increased risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma - a population-based case-control study in China. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:626–635. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang TW, Asman K, Gentzke AS, Cullen KA, Holder-Hayes E, Reyes-Guzman C, Jamal A, Neff L, King BA. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults - United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1225–1232. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6744a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vogtmann E, Flores R, Yu G, Freedman ND, Shi J, Gail MH, Dye BA, Wang GQ, Klepac-Ceraj V, Paster BJ, Wei WQ, Guo HQ, Dawsey SM, Qiao YL, Abnet CC. Association between tobacco use and the upper gastrointestinal microbiome among Chinese men. Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26:581–588. doi: 10.1007/s10552-015-0535-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kulkarni R, Antala S, Wang A, Amaral FE, Rampersaud R, Larussa SJ, Planet PJ, Ratner AJ. Cigarette smoke increases Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation via oxidative stress. Infect Immun. 2012;80:3804–3811. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00689-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arnson Y, Shoenfeld Y, Amital H. Effects of tobacco smoke on immunity, inflammation and autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 2010;34:J258–J265. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dicks LMT, Dreyer L, Smith C, van Staden AD. A Review: The Fate of Bacteriocins in the Human Gastro-Intestinal Tract: Do They Cross the Gut-Blood Barrier? Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2297. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kumariya R, Garsa AK, Rajput YS, Sood SK, Akhtar N, Patel S. Bacteriocins: Classification, synthesis, mechanism of action and resistance development in food spoilage causing bacteria. Microb Pathog. 2019;128:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mathiesen G, Huehne K, Kroeckel L, Axelsson L, Eijsink VG. Characterization of a new bacteriocin operon in sakacin P-producing Lactobacillus sakei, showing strong translational coupling between the bacteriocin and immunity genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:3565–3574. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.7.3565-3574.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kelly JR, Kennedy PJ, Cryan JF, Dinan TG, Clarke G, Hyland NP. Breaking down the barriers: the gut microbiome, intestinal permeability and stress-related psychiatric disorders. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:392. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Spadoni I, Zagato E, Bertocchi A, Paolinelli R, Hot E, Di Sabatino A, Caprioli F, Bottiglieri L, Oldani A, Viale G, Penna G, Dejana E, Rescigno M. A gut-vascular barrier controls the systemic dissemination of bacteria. Science. 2015;350:830–834. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Okuda K, Zendo T, Sugimoto S, Iwase T, Tajima A, Yamada S, Sonomoto K, Mizunoe Y. Effects of bacteriocins on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus biofilm. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:5572–5579. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00888-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Corr SC, Li Y, Riedel CU, O'Toole PW, Hill C, Gahan CG. Bacteriocin production as a mechanism for the antiinfective activity of Lactobacillus salivarius UCC118. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7617–7621. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700440104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Joo NE, Ritchie K, Kamarajan P, Miao D, Kapila YL. Nisin, an apoptogenic bacteriocin and food preservative, attenuates HNSCC tumorigenesis via CHAC1. Cancer Med. 2012;1:295–305. doi: 10.1002/cam4.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kamarajan P, Hayami T, Matte B, Liu Y, Danciu T, Ramamoorthy A, Worden F, Kapila S, Kapila Y. Nisin ZP, a Bacteriocin and Food Preservative, Inhibits Head and Neck Cancer Tumorigenesis and Prolongs Survival. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Machado LR, Ottolini B. An evolutionary history of defensins: a role for copy number variation in maximizing host innate and adaptive immune responses. Front Immunol. 2015;6:115. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Raschig J, Mailänder-Sánchez D, Berscheid A, Berger J, Strömstedt AA, Courth LF, Malek NP, Brötz-Oesterhelt H, Wehkamp J. Ubiquitously expressed Human Beta Defensin 1 (hBD1) forms bacteria-entrapping nets in a redox dependent mode of action. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006261. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schroeder S, Robinson ZD, Masterson JC, Hosford L, Moore W, Pan Z, Harris R, Souza RF, Spechler SJ, Fillon SA, Furuta GT. Esophageal human β-defensin expression in eosinophilic esophagitis. Pediatr Res. 2013;73:647–654. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nomura Y, Tanabe H, Moriichi K, Igawa S, Ando K, Ueno N, Kashima S, Tominaga M, Goto T, Inaba Y, Ito T, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Fujiya M, Kohgo Y. Reduction of E-cadherin by human defensin-5 in esophageal squamous cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;439:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jung S, Mysliwy J, Spudy B, Lorenzen I, Reiss K, Gelhaus C, Podschun R, Leippe M, Grötzinger J. Human beta-defensin 2 and beta-defensin 3 chimeric peptides reveal the structural basis of the pathogen specificity of their parent molecules. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:954–960. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00872-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Petersen C, Round JL. Defining dysbiosis and its influence on host immunity and disease. Cell Microbiol. 2014;16:1024–1033. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ajayi TA, Cantrell S, Spann A, Garman KS. Barrett's esophagus and esophageal cancer: Links to microbes and the microbiome. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14:e1007384. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yang L, Francois F, Pei Z. Molecular pathways: pathogenesis and clinical implications of microbiome alteration in esophagitis and Barrett esophagus. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2138–2144. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Orlando RC. The integrity of the esophageal mucosa. Balance between offensive and defensive mechanisms. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:873–882. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hershcovici T, Fass R. Nonerosive Reflux Disease (NERD) - An Update. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;16:8–21. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2010.16.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Winkelstein A. Peptic esophagitis. J Am Med Assoc . 1935;104:906–909. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dunbar KB, Agoston AT, Odze RD, Huo X, Pham TH, Cipher DJ, Castell DO, Genta RM, Souza RF, Spechler SJ. Association of Acute Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease With Esophageal Histologic Changes. JAMA. 2016;315:2104–2112. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Souza RF, Huo X, Mittal V, Schuler CM, Carmack SW, Zhang HY, Zhang X, Yu C, Hormi-Carver K, Genta RM, Spechler SJ. Gastroesophageal reflux might cause esophagitis through a cytokine-mediated mechanism rather than caustic acid injury. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1776–1784. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ustaoglu A, Nguyen A, Spechler S, Sifrim D, Souza R, Woodland P. Mucosal pathogenesis in gastro-esophageal reflux disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32:e14022. doi: 10.1111/nmo.14022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cheng L, Harnett KM, Cao W, Liu F, Behar J, Fiocchi C, Biancani P. Hydrogen peroxide reduces lower esophageal sphincter tone in human esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1675–1685. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Blackett KL, Siddhi SS, Cleary S, Steed H, Miller MH, Macfarlane S, Macfarlane GT, Dillon JF. Oesophageal bacterial biofilm changes in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, Barrett's and oesophageal carcinoma: association or causality? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:1084–1092. doi: 10.1111/apt.12317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Marsh PD. Dental plaque as a biofilm and a microbial community - implications for health and disease. BMC Oral Health. 2006;6 Suppl 1:S14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-6-S1-S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dejea CM, Fathi P, Craig JM, Boleij A, Taddese R, Geis AL, Wu X, DeStefano Shields CE, Hechenbleikner EM, Huso DL, Anders RA, Giardiello FM, Wick EC, Wang H, Wu S, Pardoll DM, Housseau F, Sears CL. Patients with familial adenomatous polyposis harbor colonic biofilms containing tumorigenic bacteria. Science. 2018;359:592–597. doi: 10.1126/science.aah3648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.D’Souza SM, Levitan O, Tieu AH. Bio-Geographic Variation of Colonic Biome and Biofilm Consequences on Disease: An Update for Clinicians. World J Gastroenterol Hepatol Endosc Research . 2020;1:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Münch NS, Fang HY, Ingermann J, Maurer HC, Anand A, Kellner V, Sahm V, Wiethaler M, Baumeister T, Wein F, Einwächter H, Bolze F, Klingenspor M, Haller D, Kavanagh M, Lysaght J, Friedman R, Dannenberg AJ, Pollak M, Holt PR, Muthupalani S, Fox JG, Whary MT, Lee Y, Ren TY, Elliot R, Fitzgerald R, Steiger K, Schmid RM, Wang TC, Quante M. High-Fat Diet Accelerates Carcinogenesis in a Mouse Model of Barrett's Esophagus via Interleukin 8 and Alterations to the Gut Microbiome. Gastroenterology 2019; 157: 492-506. :e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ropert A, Cherbut C, Rozé C, Le Quellec A, Holst JJ, Fu-Cheng X, Bruley des Varannes S, Galmiche JP. Colonic fermentation and proximal gastric tone in humans. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:289–296. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8690193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]