Many of the traditional studies on bacterial acid tolerance generally focused on improving cell survival under extreme-pH conditions, but cell growth under less harsh acidic conditions is more relevant to industrial applications. Under normal conditions, the general stress response sigma factor RpoS is maintained at low levels in the growth phase through a number of mechanisms.

KEYWORDS: CRISPR/Cas9, acid tolerance, chaperone Hfq, directed evolution, global regulator, small RNA DsrA

ABSTRACT

Acid tolerance of microorganisms is a desirable phenotype for many industrial fermentation applications. In Escherichia coli, the stress response sigma factor RpoS is a promising target for engineering acid-tolerant phenotypes. However, the simple overexpression of RpoS alone is insufficient to confer these phenotypes. In this study, we show that the simultaneous overexpression of the noncoding small RNA (sRNA) DsrA and the sRNA chaperone Hfq, which act as RpoS activators, significantly increased acid tolerance in terms of cell growth under modest acidic pH, as well as cell survival upon extreme acid shock. Directed evolution of the DsrA-Hfq module further improved the acid tolerance, with the best mutants showing a 51 to 72% increase in growth performance at pH 4.5 compared with the starting strain, MG1655. Further analyses found that the improved acid tolerance of these DsrA-Hfq strains coincided with activation of genes associated with proton-consuming acid resistance system 2 (AR2), protein chaperone HdeB, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) removal in the exponential phase. This study illustrated that the fine-tuning of sRNAs and their chaperones can be a novel strategy for improving the acid tolerance of E. coli.

IMPORTANCE Many of the traditional studies on bacterial acid tolerance generally focused on improving cell survival under extreme-pH conditions, but cell growth under less harsh acidic conditions is more relevant to industrial applications. Under normal conditions, the general stress response sigma factor RpoS is maintained at low levels in the growth phase through a number of mechanisms. This study showed that RpoS can be activated prior to the stationary phase via engineering its activators, the sRNA DsrA and the sRNA chaperone Hfq, resulting in significantly improved cell growth at modest acidic pH. This work suggests that the sigma factors and likely other transcription factors can be retuned or retimed by manipulating the respective regulatory sRNAs along with the sufficient supply of the respective sRNA chaperones (i.e., Hfq). This provides a novel avenue for strain engineering of microbes.

INTRODUCTION

Microbes used in industrial bioprocess applications often encounter multiple stresses (e.g., heat, acid, and oxidative and osmotic stresses, as well as toxic compounds) that negatively affect cell growth and productivity. Stress resistance is therefore vitally important to guarantee the productive robustness of the cells (1–3). Among the stresses, acid stress is one of the most concerning, especially in the production processes of organic acids and amino acids (2, 4, 5). In fact, the decline of the pH of the fermentation broth driven by the accumulation of acidic fermentative products or by-products results in the denaturation of essential enzymes and DNA damage, leading to inhibited microbial growth and production (6–8). Although the addition of bases can neutralize the fermentation broth and prevent the diffusion of acids into the cells, it brings other issues, such as increased costs in the downstream process and the generation of large volumes of wastewater (9, 10). Thus, the use of acid-tolerant strains is considered a much more efficient and cost-effective solution for industrial fermentations (11, 12).

Acid resistance (AR) in microorganisms is a complex polygenic trait involving physiological and metabolic changes that cannot be achieved by simply overexpressing a single functional gene (4, 13). Over the years, several genome-wide evolution engineering strategies, such as genome shuffling (14, 15), adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) (16–18), and multiplex automated genome engineering (MAGE) (19), have been used to enhance the acid resistance of bacterial strains. However, these approaches are considered laborious and time intensive, and it is hard to identify the mutations associated with the desired phenotype (10, 20).

A second class of strategies involves the engineering of native, artificial, or exogenous transcriptional regulators—either activators or repressors—which can simultaneously regulate hundreds of genes at the transcriptional level (10, 21–23). A notable example includes the engineering of the global regulator sigma D factor (RpoD) by random insertional-deletional strand exchange mutagenesis (RAISE), which improved cell mass by about 50% at pH 3.62 (10). In our previous work, the directed evolution of the negative global regulator H-NS improved the acid tolerance of Escherichia coli MG1655 under a more modest acid stress (pH 4.5), with a 53% increase in cell mass (22). In this regard, it is worth noting that while most of the earlier studies on bacterial acid tolerance focused on improving cell survival under extreme-pH conditions (e.g., pH 2.5), the focus has more recently shifted to improving cell growth under less harsh acidic conditions, which are more relevant to industrial applications (10, 22, 24).

The stress response sigma factor RpoS, a general regulator of the response to different stresses such as starvation, low temperature, osmotic shock, and acid stress, is a promising target for engineering acid-tolerant phenotypes (25, 26). However, it is often difficult to engineer such phenotypes by simply overexpressing RpoS alone (24, 27), likely because RpoS is tightly regulated at all levels, in particular at the translational and posttranslational levels. Among which, it was found that RpoS is upregulated by three small noncoding RNAs (sRNAs), namely, DsrA, RprA, and ArcZ, which increase rpoS mRNA stability and activate RpoS translation (25, 28). The co-overexpression of these three sRNAs has been shown to significantly increase cell survival in the exponential phase at pH 2.5 (24). Moreover, it has been reported that in order to mediate RpoS activation, these sRNAs require the presence of the chaperone Hfq, which promotes sRNA annealing to the rpoS 5′ untranscribed region (UTR) and protects them from degradation (28–30).

In this work, we found that the overexpression of DsrA alone could significantly improve cell survival at pH 2.5 to an extent comparable to that of co-overexpression of all three sRNAs, but the co-overexpression of Hfq was required for the enhancement of cell growth at pH 4.5. Further directed evolution of DsrA-Hfq conferred upon the mutant strains a significant growth advantage (51 to 72% improvement in terms of cell mass) under moderate acid stress compared to the control. To shed some light on the mechanism behind the improved acid tolerance, we analyzed the transcriptional levels of five key genes (gadE, gadB, ybaS, hdeB, and katE) by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-qPCR), the amounts of ammonia and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) released (which reflect the activation status of acid resistance system 2 [AR2]), the KatE activity (which reflects the activation of reactive oxygen species [ROS] removal), and finally the RpoS protein level (22, 31). This work demonstrates that the engineering of an sRNA like DsrA, together with the sRNA chaperone Hfq, provides a novel avenue for improving the acid tolerance of E. coli.

RESULTS

Influence of DsrA and Hfq on the acid resistance of E. coli.

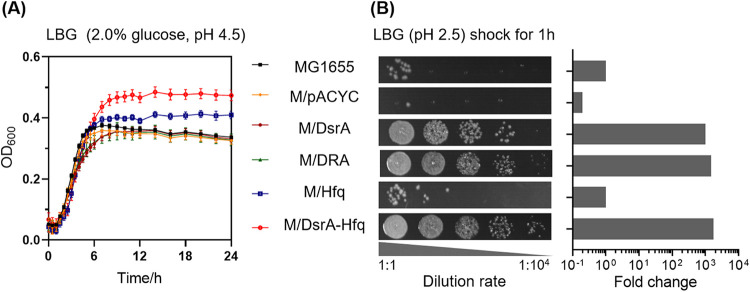

We first analyzed the influence of the three sRNAs DsrA, RprA, and ArcZ on the acid resistance of E. coli by assaying cell growth under moderate acid stress (pH 4.5) and cell survival upon extreme acid shock (pH 2.5), respectively. These three sRNAs were placed under the control of their respective native promoters and cloned into plasmid pACYC184. As shown in Fig. 1B, the overexpression of DsrA alone (strain M/DsrA) could significantly improve cell survival at pH 2.5 by about 1,000-fold compared with strain MG1655, which was similar to the co-overexpression of all the three sRNAs (strain M/DRA). However, as shown in Fig. 1A, neither the overexpression of DsrA alone nor the co-overexpression of all the three sRNAs could improve the cell growth at pH 4.5. When the sRNA chaperone Hfq (also under the native promoter) was coexpressed using the same plasmid, pACYC184, the final optical density at 600 nm (OD600) value for this strain (M/DsrA-Hfq) was 40.5% higher than that of strain MG1655, while the OD increased at a lower level for strain M/Hfq expressing Hfq alone (21.6%). Moreover, in the cell survival assay, an increase of 1,000-fold was observed for M/DsrA-Hfq compared to MG1655, but interestingly M/Hfq showed a negligible change. The result indicated that the coupling of DsrA and its chaperone Hfq (here referred to as the DsrA-Hfq module) could significantly enhance the cell growth under moderate acid stress.

FIG 1.

Cell growth of strains MG1655, M/DsrA, M/DRA, M/Hfq, and M/DsrA-Hfq under moderate acid stress in LBG (pH 4.5) containing 2.0% (wt/vol) glucose (A) and cell survival of these strains upon extreme acid shock (pH 2.5) (B). The images represent serial dilutions of the cultures in 10-fold steps (from left to right, 1:1 to 1:10,000). The fold change was calculated relative to the cell survival observed for strain MG1655.

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated directed evolution of DsrA-Hfq in the genomic context of E. coli.

Considering the potential industrial application, we then integrated the DsrA-Hfq module into the genomic DNA of E. coli MG1655, using the poxB locus via a scarless CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing method to yield wild-type (WT) strain DsrA-Hfq(WT) (32). Cell growth and survival were again assayed under moderate acid stress (pH 4.5) or upon extreme acid shock (pH 2.5), respectively. Under moderate acid stress, the final OD600 value of strain DsrA-Hfq(WT) was 34% higher than that of strain MG1655 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), but lower than the increase observed for strain M/DsrA-Hfq with the plasmid-borne DsrA-Hfq module. Cell survival was increased by approximately 100-fold compared with that of strain MG1655 (Fig. S1), but again was lower than that observed for strain M/DsrA-Hfq. As a control, the cell growth and survival of the ΔpoxB strain were comparable to those of strain MG1655, indicating that the observed performance improvement was specific and not merely caused by the insertion of a new DNA fragment into the poxB locus. These results demonstrated that the integration of a DsrA-Hfq module in a genomic context was successful in enhancing acid tolerance of E. coli in both cell growth and survival.

To further improve the acid tolerance acquired by the introduction of the DsrA-Hfq module in the genomic context, we subsequently fine-tuned this module via directed evolution using a modified process, as reported in our previous study (22) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). First, the library of DsrA-Hfq mutants was constructed by a standard error-prone PCR (epPCR) protocol and inserted into the poxB locus of the genomic DNA via the same CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing process mentioned above (32). For the construction of the DsrA-Hfq mutagenesis library, we compared two schemes: one involving the use of a circular plasmid and the other using a linear DNA fragment as the donor DNA in the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing (33) (Fig. S2). As shown in Table 1, the integration efficiency was 92.8% ± 7.2% for the linear DNA fragment scheme, whereas it was only 21.4% ± 3.6% for the circular plasmid scheme. To cure the two plasmids introduced during the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing (pTargetT and pCas), an isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible single guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting the pMB1 replicon in pTargetT and the temperature-sensitive repA101(Ts) replicon in pCas were used (32). Both plasmids were removed with very high efficiencies (93.2 to 99.6%), which were more than sufficient for the following selection of DsrA-Hfq mutants (Table 1). Subsequently, the strain library was subjected to 10 rounds of selection under pH 4.5, and 200 colonies for each scheme (circular plasmid DNA or linear DNA) were picked for growth analysis under the same moderate-acid-stress condition. As shown in Fig. 2, compared to strain DsrA-Hfq(WT), only 16 colonies (7.8%) showed a higher final OD600 and no colony exhibited a higher maximum growth rate (μmax) for the circular plasmid scheme, whereas the linear DNA fragment scheme resulted in 56 colonies (29.6%) showing a higher final OD600 and 96 colonies (50.8%) showing a higher μmax.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of the efficiencies of integration and plasmid curing obtained by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genomic editing using the circular plasmid and the linear DNA fragment schemes

| Function | Efficiency of integration or curing (%) by scheme |

|

|---|---|---|

| Circular plasmid | Linear DNA fragment | |

| Integration | 21.4 ± 3.6 | 92.8 ± 7.2 |

| Curing of: | ||

| pTargetT | 99.5 ± 0.5 | 93.2 ± 0.8 |

| pCas | 99.5 ± 0.5 | 99.6 ± 0.5 |

FIG 2.

Final OD600 and maximum growth rate (μmax) of the DsrA-Hfq mutant strains after 10 rounds of selection via the circular plasmid scheme (A) and the linear DNA fragment scheme (B). For each scheme, 200 colonies were picked and analyzed.

Evaluation of the acid resistance of DsrA-Hfq mutant strains.

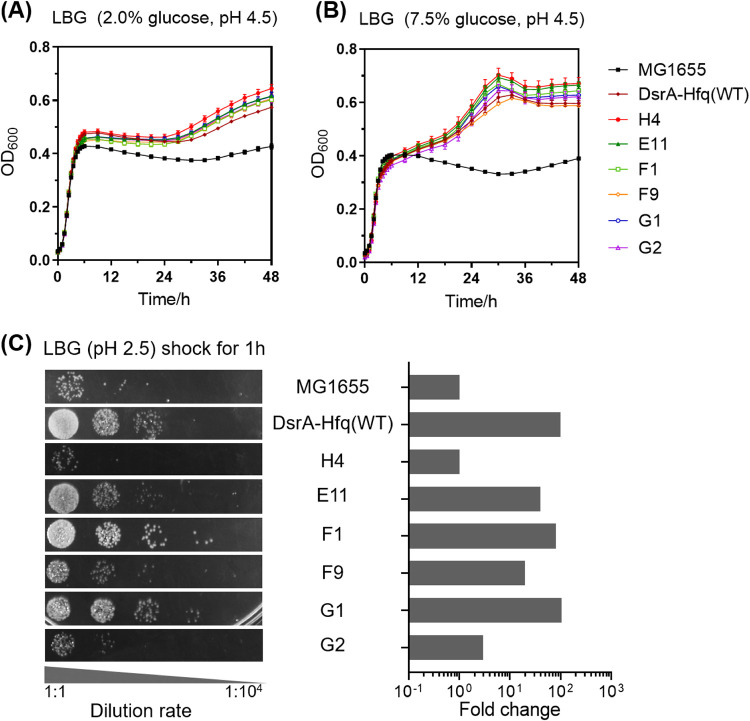

To eliminate the cumulative effects of spontaneous background mutations occurring in the genomic DNA during the 10 rounds of selection, we amplified the 22 DsrA-Hfq mutant sequences from the strains that showed the highest final OD600 and μmax compared with strain DsrA-Hfq(WT), and then we integrated them back into fresh MG1655 cells, individually. After analysis of growth at pH 4.5, the six mutant strains showing the best growth, namely, E11, F1, F9, G1, G2, and H4, were chosen for further characterization (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). As shown in Fig. 3A, the final OD600 of these six mutant strains after 48 h of culture in LBG medium (pH 4.5 lysogeny broth containing 2% [wt/vol] glucose) was enhanced by 41 to 51% compared with that of strain MG1655. The μmax values of the six mutant strains were essentially comparable (1 to 5%) to those of strain MG1655. Moreover, we further evaluated the acid tolerance of the six mutant strains in LBG medium (pH 4.5) containing 7.5% (wt/vol) glucose, given that such high initial glucose concentrations are often employed in industrial fermentation. These six mutant strains showed an even better growth performance (53 to 72% increase) in higher-glucose-concentration medium (Fig. 3B). Among them, H4 showed the highest increase of final OD600 compared with MG1655 and DsrA-Hfq(WT) (72 and 12.6%, respectively). The results indicated that the directed evolution of the DsrA-Hfq module integrated into the E. coli genome can result in an increase in growth performance under moderate acid stress.

FIG 3.

Cell growth of MG1655, DsrA-Hfq(WT), and mutant strains under moderate acid stress in LBG (pH 4.5) containing 2.0% (wt/vol) glucose (A) or 7.5% (wt/vol) glucose (B), as well as cell survival of these strains after extreme acid shock (pH 2.5) (C). The images represent serial dilutions of the cultures in 10-fold steps (from left to right, 1:1 to 1:10,000). The fold change was calculated relative to the cell survival observed for strain MG1655.

As shown in Fig. 3C, the number of surviving cells for mutant strains F1 and G1 under extreme acid stress was approximately 100-fold higher than that of strain MG1655 and comparable to that of DsrA-Hfq(WT), respectively. Mutant strains E11 and F9 showed 20- to 40-fold improvements, and mutant strains G2 and H4 showed no significant changes in the same test (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, H4 was the strain that showed the best growth performance under moderate acid stress, and E11 was the second best. These results suggested that the cell survival under extreme acid stress is not directly related to the cell growth performance under more modest acid conditions (22). Thus, these two best mutant strains in terms of cell growth, H4 and E11, were chosen for the further analysis.

Mutant strains H4 and E11 were then repeatedly transferred into liquid medium for 10 days (∼400 generations) to test the genotype stability and confirm the acid resistance phenotype. The PCR results confirmed the existence of the DsrA-Hfq module in strains H4 and E11 after 10 days of cultivation (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material), and the cell growth remained unchanged (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). These results indicated that both the genotype and phenotype of the DsrA-Hfq mutant strains were stable. We also found that the acid tolerance phenotype of these two mutant strains was stable when the fermentation level was scaled up from the 300-μl Honeycomb microplates (used in the Bioscreen C equipment) to the 500-ml shaking flasks (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Consistent with our previous report (22), the pH value of the fermentation broth remained constant at pH 4.5 ± 0.3 during the whole fermentation period (Fig. S4).

Transcriptional analysis of five key genes in the DsrA-Hfq mutant strains.

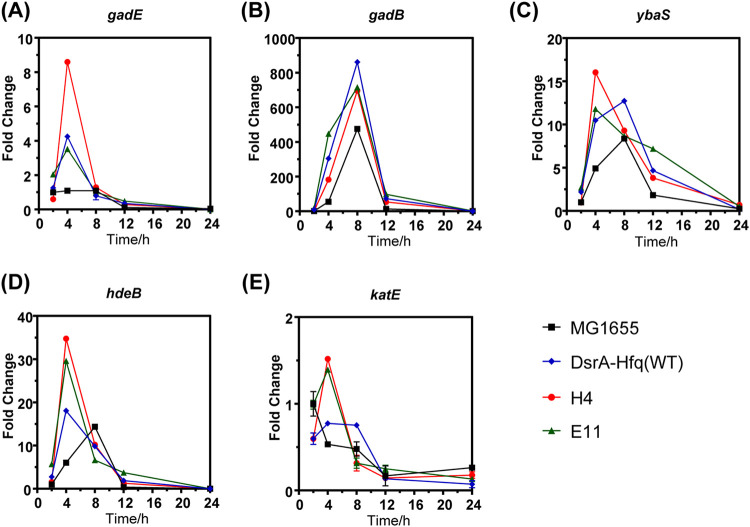

To explore how the DsrA-Hfq mutant strains acquired acid tolerance, we analyzed the activation of the AR2 system, protein chaperone HdeB, and the removal of intracellular ROS (22, 31). First, we determined the transcriptional changes of the five key genes (i.e., gadE, gadB, ybaS, hdeB, and katE) that are known to significantly contribute to acid resistance in E. coli by RT-qPCR (22, 31). Proteins GadE, GadB, and YbaS are the main components of the AR2 system (34, 35), HdeB as a periplasmic chaperone protects proteins in the periplasmic space under acid stress (22, 36), and katE encodes catalase II, which is involved in the removal of intracellular ROS (37, 38). As shown in Fig. 4, the highest transcription levels of the five genes all occurred in the exponential phase for all the strains, but relative to strain MG1655, the peak arrived earlier for ybaS and hdeB (4 versus 8 h in MG1655), at the same time for gadE (4 h) and gadB (8 h), and later for katE (4 versus 2 h in MG1655) in the two mutant strains. The same tendency was observed for strain DsrA-Hfq(WT) compared with MG1655, except that the highest transcription level of ybaS occurred at the same time. These results suggested that the effects of the engineering of DsrA-Hfq manifested mostly in the exponential phase (2 to ∼8 h), and these changes likely provided protection from acid stress during cell growth.

FIG 4.

Transcriptional analysis of expression of genes gadE (A), gadB (B), ybaS (C), hdeB (D), and katE (E) in MG1655, DsrA-Hfq(WT), and mutant strains via RT-qPCR. The fold change was calculated relative to the transcription level of each gene observed for strain MG1655 at 2 h of incubation.

In terms of magnitude, compared to MG1655, the highest transcriptional levels of the five genes (gadE, gadB, ybaS, hdeB, and katE) were 7.9-, 1.4-, 3.3-, 5.8-, and 2.8-fold for mutant strain H4, 3.2-, 1.5-, 3.4-, 4.9-, and 2.6-fold for mutant strain E11, and 3.9-, 1.8-, 2.1-, 3.0-, and 1.5-fold for DsrA-Hfq(WT) (Fig. 4). Mutant strain H4 had the highest levels of transcription of gadE, ybaS, hdeB, and katE compared with the other three strains.

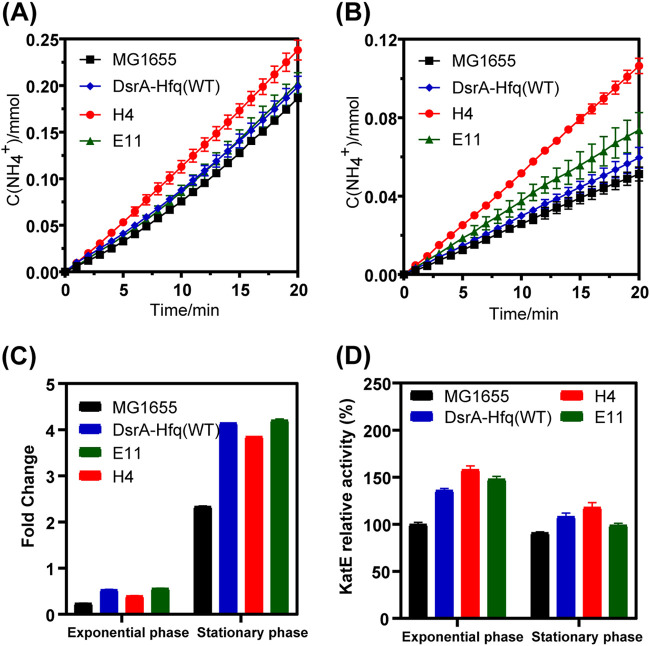

Determination of the key enzymes’ activities in the DsrA-Hfq mutant strains.

We then analyzed the activities of GadB, YbaS, and KatE by examining the release of ammonia, the release of GABA, and the removal of ROS, respectively. As shown in Fig. 5A to C, all of the strains with DsrA-Hfq integrated in their genomes released ammonia and GABA at a higher rate than strain MG1655 in both the exponential phase and stationary phase. In particular, the rates of ammonia release for strains H4, E11, and DsrA-Hfq(WT) were 28, 9, and 7% higher in the exponential phase and 107, 44, and 16% higher in the stationary phase than those of strain MG1655 (Fig. 5A and B), respectively. The rate of ammonia release for mutant strain H4 was higher than those of strain DsrA-Hfq(WT) and mutant strain E11 in both the exponential phase and stationary phase. The rates of GABA release for strains H4, E11, and DsrA-Hfq(WT) were 68, 137, and 124% higher in the exponential phase and 65, 80, and 77% higher in the stationary phase than those of strain MG1655 (Fig. 5C), respectively. The GABA release rate for mutant strain H4 was lower than those of DsrA-Hfq(WT) and mutant strain E11 in the exponential phase, while the rates were comparable in the stationary phase. These results demonstrated the involvement of the AR2 system in the improved acid tolerance shown by the strains bearing the DsrA-Hfq module.

FIG 5.

The release of ammonia in the exponential phase (A) and in the stationary phase (B), the release of GABA in the exponential phase and in the stationary phase (C), and the relative activity of KatE (D) for the MG1655, DsrA-Hfq(WT), and mutant strains. The relative activity of KatE was calculated relative to the KatE activity observed for strain MG1655 in the exponential phase at 4 h. Error bars indicate the standard error from three biological replicates. GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid.

As shown in Fig. 5D, compared with strain MG1655, the KatE activities in strains H4, E11, and DsrA-Hfq(WT) were 37, 49, and 58% higher in the exponential phase and 18, 9, and 30% higher in the stationary phase, respectively. Timely removal of the ROS is critical in the acid tolerance of E. coli, as the increase of ROS will negatively affect the cell metabolism and growth (37). These results of the enzyme activities of GadB, YbaS, and KatE were consistent with their transcriptional levels as described above.

Analysis of RpoS levels in the DsrA-Hfq mutant strains.

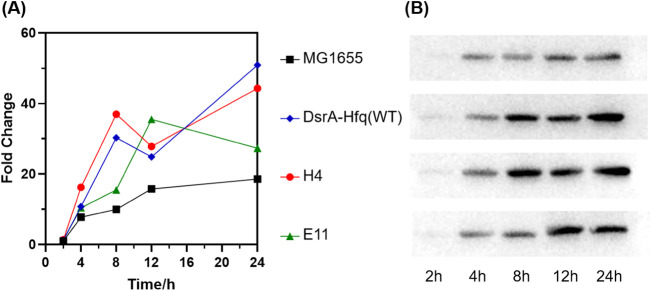

Finally, we carried out Western blotting to determine RpoS levels in strain MG1655 and the DsrA-Hfq strains (H4, E11, or WT) under moderate acid stress. As shown in Fig. 6, the overexpression of the DsrA-Hfq module (H4, or E11, or WT) indeed activated RpoS expression in the exponential phase, and that trend continued into the stationary phase, presumably thereby upregulating the related AR systems (24, 26, 30). Specifically, the protein expression levels of RpoS in strains H4, E11, and DsrA-Hfq(WT) were 37 to 271%, 19 to 55%, and 22 to 204% higher in the exponential phase (2 to 8 h) and 77 to 139%, 47 to 125%, and 58 to 174% higher in the stationary phase (12 to 24 h) than those of strain MG1655, respectively.

FIG 6.

Protein levels of RpoS for the wild-type strains MG1655 and DsrA-Hfq(WT) and mutant strains H4 and E11, presented as fold change (A) and Western blotting results (B). The fold change was calculated relative to the density of the RpoS band observed for strain MG1655 at 2 h.

Sequence alignment and mutation analysis of the mutants.

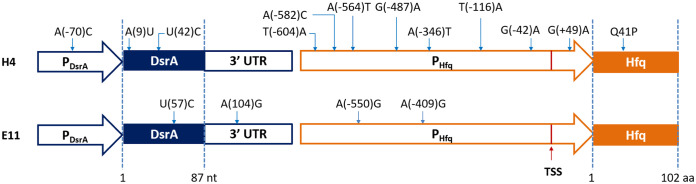

The 22 DsrA-Hfq mutants were sequenced and aligned with the wild type (WT) to identify the mutations (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). All 22 of these mutants were unique, and they had a total of 95 mutations. The mutations were analyzed in detail for the mutants H4 and E11, which had the best growth profiles under moderate acid stress (Fig. 7). There were 12 mutations for H4 and 4 mutations for E11. The mutations in the promoter region might affect the expression level of DsrA and Hfq, and the mutations in the 3′ UTR region of DsrA might affect its RNA maturation. For the mutations in gene coding regions, in mutant H4, mutation A(9)U is located in the first stem-loop (SL1) region of DsrA, which is the rpoS mRNA binding domain, and hence might change its rpoS activation efficiency (39, 40). The other mutation, U(42)C, is located in the SL2 region of DsrA, which is the hns mRNA binding region; therefore, this mutation might change its hns mRNA binding efficiency (39, 40). The sole amino acid mutation, Q41P, in Hfq is located in the Sm fold domain (amino acid residues 7 to 66), which reportedly affects its binding affinity for the U-rich region of DsrA and its ATPase activity (30, 41). In mutant E11, there was only one mutation in the gene coding region, U(57)C, which is also located in the hns mRNA binding region SL2 (39, 40). Taken together, these mutations in the gene coding regions likely affect the interactions between DsrA and Hfq and between DsrA and rpoS and hns mRNAs.

FIG 7.

Summary of the mutations for DsrA-Hfq mutants (H4 and E11). TSS, transcription start site; aa, amino acid residues.

We attempted to dissect the effects of these mutations, and to this end, we analyzed the effects of mutations in the two promoter regions of mutant strains H4 and E11. Among them, only mutant H4 had a mutation in the dsrA promoter region, while both of them had mutations in the hfq promoter region (Fig. 7). We first tried RT-qPCR on the dsrA promoter but failed to detect significant signal. Subsequently, the expression levels of dsrA in DsrA-Hfq(WT) and H4 were analyzed by using mCherry as a reporter (42). The expression level of hfq was analyzed by the standard RT-qPCR. For dsrA, as shown in Fig. S5A in the supplemental material, compared with the wild-type promoter in strain DsrA-Hfq(WT), the mutation in the promoter region in H4 led to a slight increase in terms of mCherry fluorescence/OD600 in both the exponential phase (6 to 8%) and the stationary phase (12 to 14%) (Fig. S5A). For hfq, as shown in Fig. S5B, compared with the wild-type promoter in strain DsrA-Hfq(WT), the mutations in the promoter region of H4 or E11 resulted in a 0.8- or 0.2-fold higher transcription in the exponential phase and 0.4- or 0.2-fold higher transcription in the stationary phase, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that the engineering of DsrA-Hfq, an AR module consisting of a RpoS activator sRNA (DsrA) and its chaperone (Hfq), via plasmid or genomic integration can improve the cell growth and survival of E. coli under acid stress. Thus, this study provides a new strategy for efficiently enhancing acid resistance performance in terms of growth advantage. Under moderate acid stress, the mutant that grew the best, H4, grew comparably to the previously reported strain 3-36, which harbors a plasmid-borne hns mutant (51 versus 53% improvement over the reference strain MG1655) (22), and strain AcM1, which harbors a plasmid-borne crp mutant (52% improvement) (21). Additionally, the engineering of DsrA-Hfq in a genomic context has an advantage in that both the genotype and phenotype of the engineered strains are stable, which is preferred for industrial applications (43).

CRISPR/Cas9 has been applied for genome engineering and reprogramming in E. coli with high efficiency (32, 33). Based on this, CRISPR-enabled trackable genome engineering (CREATE) and its derived approaches were developed for direct enzyme engineering in the genomic context of E. coli (44, 45). In this study, we replaced the region-specific mutagenesis strategy used in CREATE approaches with epPCR products for the entire DsrA and Hfq cassette. We also found that linear DNA fragments were more efficiently recombined than circular plasmids as donor DNA, which is consistent with earlier reports (46, 47). One of the reasons for this observation is that the overexpression of the λRed proteins Exo, Beta, and Gam, which are essential for an efficient homologous recombination in E. coli, preferentially promotes homologous recombination between a linear DNA and the chromosome (48, 49).

RpoS is strongly regulated at the transcriptional, translational, and posttranslational levels (25, 28). Under normal conditions, the expression of RpoS in the growth phase is maintained at low levels through a number of mechanisms: i.e., the rpoS mRNA is rapidly digested by RNase E, its ribosome-binding site is blocked by its 5′ UTR, and RpoS is captured by RssB and subsequently degraded by ClpXP ATP-dependent protease (25, 28). On the other hand, three sRNAs (DsrA, ArcZ, and RprA) can interact with the rpoS mRNA in the presence of Hfq, which stabilize its secondary structure and promote its translation (27, 41, 50). DsrA also downregulates H-NS, which in turn upregulates the expression of IraD and IraM (defined as antiadaptors) and then inhibits RpoS proteolysis (51, 52). Given that the overexpression of DsrA with or without the other two sRNAs, ArcZ and RprA, was found to improve cell survival under extreme acid shock conditions but not cell growth (24), the growth advantage in acidified medium observed in this study for the strains harboring DsrA-Hfq and mutants likely derives mostly from the overexpression of Hfq. Hfq is a chaperone not just for DsrA, but for a variety of other sRNAs, tRNAs, rRNAs, and even DNA molecules (53–56). Hfq not only impacts the RpoS level but also presumably promotes protein synthesis by activating ribosome biogenesis (53, 56) and possibly influences the nucleoid structure dynamic and DNA replication (54, 55). We speculate that the engineering of sRNAs and sRNA chaperones together would be a promising strategy for developing stress tolerance phenotypes. In addition to DsrA, ArcZ, and RprA, it has been recognized that several other sRNAs can potentially enhance bacterial responses to various stresses (40, 57–59). For example, MicF is related to osmotic stress tolerance (60), GadY regulates acid stress tolerance (24, 58), and both of them are Hfq dependent. These and other Hfq-dependent sRNAs will be further exploited in future studies.

Finally, we found that the activation of the AR2 system, protein chaperone HdeB, and ROS removal mechanisms during the exponential growth phase were the main contributors to the observed acid tolerance of the engineered DsrA-Hfq strains, consistent with previous reports (13, 22). Therefore, direct retiming and retuning via synthetic biology approaches for the expression of these important factors at appropriate stages of fermentation might also be useful for strain engineering for acid tolerance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and materials.

The bacterial strains in this study are listed in Table 2. The ΔpoxB strain was constructed by employing pCas and pTargetT-ΔpoxB. Strain DsrA-Hfq(WT) was constructed by employing pCas and pTargetT-ΔpoxB-DsrA-Hfq. E. coli DH5α, used for the vector construction, was cultured in lysogeny broth (LB). The antibiotics used for selections of E. coli were 50 μg/ml kanamycin and/or 50 μg/ml spectinomycin.

TABLE 2.

E. coli strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype or description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| MG1655 | Wild-type strain | Lab collection |

| M/DsrA | MG1655/pACYC184-DsrA | This study |

| M/DRA | MG1655/pACYC184-DsrA-RprA-ArcZ | This study |

| M/Hfq | MG1655/pACYC184-Hfq | This study |

| M/DsrA-Hfq | MG1655/pACYC184-DsrA-Hfq | This study |

| M/PdsrA-mCherry | MG1655/pACYC184-PdsrA-mCherry | This study |

| M/PdsrA(H4)-mCherry | MG1655/pACYC184-PdsrA(H4)-mCherry | This study |

| ΔpoxB | MG1655 ΔpoxB | This study |

| DsrA-Hfq(WT) | MG1655 poxB::DsrA-Hfq (wild type) | This study |

| H4 | MG1655 poxB::DsrA-Hfq (H4) | This study |

| E11 | MG1655 poxB::DsrA-Hfq (E11) | This study |

| F1 | MG1655 poxB::DsrA-Hfq (F1) | This study |

| F9 | MG1655 poxB::DsrA-Hfq (F9) | This study |

| G1 | MG1655 poxB::DsrA-Hfq (G1) | This study |

| G2 | MG1655 poxB::DsrA-Hfq (G2) | This study |

The restriction enzymes Q5 DNA polymerase and T4 DNA ligase were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA, USA). LA Taq DNA polymerase was purchased from TaKaRa Biotechnology (Dalian, China). Oligonucleotide synthesis and sequence analysis were performed by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). The kits for DNA purification, gel recovery, genomic DNA extraction, and plasmid miniprep were purchased from Zymo Research (Orange County, CA, USA) or Tiangen (Beijing, China). All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Shanghai, China) or Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China).

Plasmid construction.

The plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 3. The DNA sequences of the primers used in this study are listed in Table 4, the homologous DNA fragments and genes used in this study are listed in Table S4 in the supplemental material, and the gene products are listed in Table S5 in the supplemental material. The gRNAs used in this study were designed by the online CRISPR RGEN Tools (www.rgenome.net). The “N20” sequence for the target poxB was AATTGGCAGCGGCTATTTCC (where “N20” represents the 20-bp complementary region and “N” represents any nucleotide).

TABLE 3.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| pACYC184-DsrA | p15A PdsrA-dsrA Cmr | This study |

| pACYC184-DRA | p15A PdsrA-dsrA PrprA-rprA ParcZ-arcZ Cmr | This study |

| pACYC184-Hfq | p15A Phfq-hfq-Cmr Cmr | This study |

| pACYC184-DsrA-Hfq | p15A PdsrA-dsrA Phfq-hfq Cmr | This study |

| pACYC184-PdsrA-mCherry | p15A PdsrA-mCherry Cmr | This study |

| pACYC184-PdsrA(H4)-mCherry | p15A PdsrA(H4)-mCherry Cmr | This study |

| pTargetF-cadA | pMB1 sgRNA-cadA Sper | Gift of Sheng Yang (32) |

| pCas | repA101(Ts) Pcas-cas9 ParaB-Red lacIq Ptrc-sgRNA-pMB1 Kanr | Gift of Sheng Yang (32) |

| pTargetF-ΔpoxB | pMB1 sgRNA-poxB Sper | This study |

| pTargetT-ΔpoxB | pMB1 sgRNA-poxB homologous fragment of poxB Sper | This study |

| pTargetT-ΔpoxB-DsrA-Hfq | pMB1 sgRNA-poxB homologous fragment of poxB-DsrA-Hfq Sper | This study |

TABLE 4.

Primers used in this study

| Primer name | Sequence (5′→3′)a | Description |

|---|---|---|

| PoxB-N20(poxB)-F | CTAGTAATTGGCAGCGGCTATTTCCGTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGCAAGTTAAAATA | Replace sgRNA target poxB |

| PoxB-N20(poxB)-R | GGAAATAGCCGCTGCCAATTACTAGTATTATACCTAGGACTGAGCTAGCTGTC | |

| poxB-X1-F | GAATTCTCTAGAGTCGACTCTGAAATTCACCAAACTGCAACCGGCACGA | Upstream homologous fragment of poxB |

| poxB-X1-R | CGCCGACCAGTGCCATATCGGTTAAATAGCCCGATGAAAGGAATATCA | |

| poxB-X2-F | CATCGGGCTATTTAACCGATATGGCACTGGTCGGCGATATCAAGTCGAC | Downstream homologous fragment of poxB |

| poxB-X2-R | GCTAGCCATAAAAAGCTTGGTTAAACGAACCTAACAGGCGACGCTTG | |

| HindIII-AatII-DsrA-for | TATCTCAAGCTTGACGTCCATAGTCGCGCAGTACTCCT | dsrA cassette |

| DsrA-rev | TATCTAGTCGACCATACATGGCGTGAATTGGCGGAT | |

| DR-DsrA-rev | TACTACCAGCTGACATACATGGCGTGAATTGGCGGAT | Overlap of dsrA, rprA, and ArcZ cassette |

| DR-RprA-for | CACGCCATGTATGTCAGCTGGTAGTACCTGTCGCAAA | |

| RA-RprA-rev | AGCGGATGCTGACGGCTTGAAGAGAGTCACAGT | |

| RA-ArcZ-for | CTCTCTTCAAGCCGTCAGCATCCGCTCAGAATTACGCCAAT | |

| Pnat-Hfq-F | AGCTTGACGTCGGATCCCACTGTTAGTGGG | hfq cassette |

| Hfq-R | TGCCTCTCGAGCGTGTAAAAAAACAGCCCGA | |

| PstI-DsrA-Hfq-F | GCTATTTAACCGCTGCAGCATAGTCGCGCAGTACTCCTCTTACC | DsrA-Hfq module |

| NotI-DsrA-Hfq-R | TTTGATGCCTGCGGCCGCCGTGTAAAAAAACAGCCCGAAACCT | |

| pACYC-PdsrA-F | CCGCTTATTATCACTTATTCAGGCGTAGCAC | pACYC-PdsrA fragment |

| pACYC-PdsrA-R | GATCCTTTCTCCTCTTTAATGAATTGCATCACCTTATCCGCAATTTTTTTCG | |

| mCherry-F | ATTAAAGAGGAGAAAGGATCCATGGTTTCTAAAGGTGAAGAAGACAAC | mCherry gene fragment |

| mCherry-R | TTCGCAACGTTCAAATCCGCTCCCGGCGGATTTGTCCTACTCAGGAG | |

| pACYC-TrrnB-F | GGAGCGGATTTGAACGTTGCGAA | pACYC-TrrnB fragment |

| pACYC-TrrnB-R | CGCCTGAATAAGTGATAATAAGCGGATGA | |

| PdsrA(H4)-R | CGCCATATGAATGATTAACGCTACTTAGGAATAGAAATGTGAC | Introduction of mutation into dsrA promotera |

| pACYC-F | GTAGCGTTAATCATTCATATGGCGAAT | |

| epPCR-F1 | AAAACTGCAGCATAGTCGCGCAGTACTC | epPCR of DsrA-Hfq module for circular plasmid scheme |

| epPCR-R1 | ATAGTTTAGCGGCCGCCGTGTAAAAAAACA | |

| epPCR-F2 | TCTGAAATTCACCAAACTGCAAC | epPCR of DsrA-Hfq module flanked by poxB homologous fragments for linear DNA fragment scheme |

| epPCR-R2 | GGTTAAACGAACCTAACAGGCGACG | |

| 16S-qPCR-F | TAAACTGGAGGAAGGTGGGGA | RT-qPCR of 16S rRNA genes |

| 16S-qPCR-R | TCATGGAGTCGAGTTGCAGAC | |

| gadE-qPCR-F | CTGGAGAAATTAGATGCCG | RT-qPCR of gadE |

| gadE-qPCR-R | GGGGCAAGTGTTTACCATA | |

| gadB-qPCR-F | GCATAAATTCGCCCGCTACTG | RT-qPCR of gadB |

| gadB-qPCR-R | AGCGGTTGTGGGAACTCATAG | |

| ybaS-qPCR-F | CTCAGTTATCGCCTTAGAGT | RT-qPCR of ybaS |

| ybaS-qPCR-R | GGATATGTAAAATTCGCTGCC | |

| hdeB-qPCR-F | GTCACTGGTGAACGCACAATC | RT-qPCR of hdeB |

| hdeB-qPCR-R | TCTTCATGCAGCATCCACCAT | |

| katE-qPCR-F | GCATCGCCGACGATCAAA | RT-qPCR of katE |

| katE-qPCR-R | GCATGAACAATACGTTCCG | |

| dsrA-qPCR-F | CACATCAGATTTCCTGGTGTAACG | RT-qPCR of dsrA |

| darA-qPCR-F | GGGGTCGGGATGAAACTTGC | |

| hfq-qPCR-F | CTGCAAGGGCAAATCGAGT | RT-qPCR of hfq |

| hfq-qPCR-F | GCGTTGTTACTGTGATGAGA | |

| Gs-poxB X1-F | CGATGTGCGGGTGATCTACAAC | To confirm genotype stability |

| Gs-poxB X2-R | GCCACCAGCTTTCATCTCCAT |

The boldface letter in the sequence indicates the mutation site. The underlined letters indicate the restriction enzyme recognition sites.

Briefly, the dsrA, rprA, arcZ, and hfq genes and their native promoters were PCR amplified from E. coli MG1655 genomic DNA. The mCherry gene was synthetized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). pACYC184-DsrA was constructed by inserting the dsrA cassette after double digestion with HindIII and SalI. The dsrA, rprA, and arcZ cassettes were assembled together using overlap PCR, and then the assembled DNA product was double digested by AatII and SalI and inserted into pACYC184-DsrA to generate pACYC184-DRA. The dsrA cassette was replaced by the hfq cassette to generate pACYC184-Hfq. The dsrA and hfq cassettes were assembled together using overlap PCR, and then the assembled DNA product was digested by AatII and SalI and inserted into pACYC184-DsrA to generate pACYC184-DsrA-Hfq. pTargetF-poxB was constructed by replacing the N20 of gRNA in pTargetF-cadA with the N20 of the target poxB. Plasmid pTargetT-ΔpoxB was constructed by inserting the upstream and downstream homologous fragments of poxB, which were amplified from E. coli MG1655 genomic DNA, into pTargetF-poxB for deletion of poxB. Plasmid pTargetT-ΔpoxB-DsrA-Hfq was constructed by inserting the DsrA-Hfq module into pTargetT-ΔpoxB and used for integration of the DsrA-Hfq module into the poxB locus. The DsrA-Hfq module was amplified from plasmid pACYC184-DsrA-Hfq by using primers PstI-DsrA-Hfq-F and NotI-DsrA-Hfq-R (61). Plasmid pACYC184-PdsrA-mCherry was constructed by assembling three DNA fragments, the mCherry gene, pACYC-PdsrA, and pACYC-TrrnB. pACYC-PdsrA and pACYC-TrrnB were amplified from plasmid pACYC184-DsrA-Hfq. A Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence (CAATTCATTAAAGAGGAGAAAGGATCC) was introduced into the upstream portion of the mCherry gene. To construct plasmid pACYC184-PdsrA(H4)-mCherry, mutation A(−70)C was introduced into plasmid pACYC184-PdsrA-mCherry using primer PdsrA(H4)-R. Gene fragment assembly was conducted according to the Gibson assembly method (62).

Library construction and CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing.

The random mutagenesis of DsrA-Hfq module was performed by standard epPCR (63). For the circular plasmid scheme, the DsrA-Hfq module was subjected to epPCR using pTargetT-ΔpoxB-DsrA-Hfq with primers epPCR-F1 and epPCR-R1. After purification and digestion by PstI and NotI, the epPCR product was inserted into plasmid pTargetT-ΔpoxB-DsrA-Hfq to replace the wild-type DsrA-Hfq module. The ligation product was then transformed into E. coli MG1655 competent cells. Cells were incubated overnight at 37°C on LB plates containing 50 μg/ml spectinomycin and then scraped off to extract the plasmid and create the mutation library. The library size was 105, with a suitable mutation rate controlled at 3 mutations per dsrA-hfq cassette, or 2 mutations per kb by adjusting the concentration of Mn2+. Two micrograms of DsrA-Hfq mutation library was transformed by electroporation into E. coli MG1655 competent cells harboring pCas and then integrated into the genomic DNA at the poxB locus (32). Cells were incubated overnight at 30°C on LB plates containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin and 50 μg/ml spectinomycin to create a DsrA-Hfq mutant strain library with around 105 colonies.

For the linear DNA fragment scheme, the DsrA-Hfq module was subjected to epPCR using pTargetT-ΔpoxB-DsrA-Hfq with primers epPCR-F2 and epPCR-R2, which resulted in the production of the DsrA-Hfq module flanked by the poxB homologous fragments. The mutation rate of the epPCR product, representing the mutation library, was controlled at 3 mutations per dsrA-hfq cassette, or 2 mutations per kb by adjusting the concentration of Mn2+. Then, 400 ng epPCR product was cotransformed by electroporation together with 100 ng pTargetF-ΔpoxB into E. coli MG1655 competent cells harboring pCas and was integrated into the genomic DNA at the poxB locus (32). Cells were incubated overnight at 30°C on LB plates containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin and 50 μg/ml spectinomycin to create a DsrA-Hfq mutant strain library with around 105 colonies.

Plasmid curing.

Plasmid curing was done by following a previously reported method (32). Briefly, the pTargetT series plasmids were cured first by inoculating the cells in LB medium containing kanamycin (50 mg/liter) and 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Then the colonies were confirmed as cured by determining their sensitivity to spectinomycin (50 mg/liter). Afterwards, the pTargetT-cured cells were incubated overnight at 37°C for curing of the temperature-sensitive pCas. Then the colonies were confirmed as cured by determining their sensitivity to kanamycin (50 mg/liter).

Library selection.

The mutants obtained with each scheme were selected by culturing the cells under moderate acid stress for 10 rounds. For each round, 200-μl aliquots from 10 cultures of the library with initial OD600 of 0.05 were separately inoculated into 10 ml LBG medium (LB supplemented with 2% [wt/vol] glucose) acidified by HCl to pH 4.5 and cultivated at 37°C at 250 rpm for 16 h. This procedure was repeated for 10 rounds, then 200 clones were isolated from the population of the last round, and their growth curves were monitored by an automated turbidimeter (Bioscreen C; Oy Growth Curves Ab, Ltd., Helsinki, Finland). The cultures were incubated with shaking in 100-well Honeycomb microplates at 37°C and 1,000 rpm. The DsrA-Hfq mutants were amplified from the strains that showed the highest final OD600 and μmax compared with strain DsrA-Hfq(WT) and integrated into fresh E. coli MG1655 competent cells for further confirmation.

Cell growth and survival assays.

The cell growth and survival assays were performed as detailed in our previous report (22). Briefly, for the cell growth assay, the overnight cultures were diluted to an initial OD600 of 0.05 in 300 μl LBG medium (pH 4.5) with 2% (wt/vol) glucose or 7.5% (wt/vol) glucose. Then the cultures were incubated at 37°C at 1,000 rpm in 100-well Honeycomb microplates, and their OD600 was monitored for 48 h using an automated turbidimeter (Bioscreen C; Oy Growth Curves Ab Ltd., Helsinki, Finland). For analysis of the cell growth of the mutant strains in the 500-ml shaking flask, the overnight cultures were diluted 1:10 with 150 ml LBG medium (pH 4.5) and grown at 37°C at 250 rpm in the incubator shaker. Samples were taken periodically to measure OD600 and pH.

For the cell survival assay, the overnight cell cultures were diluted to an initial OD600 of 0.05 in fresh LBG medium (pH 4.5) and grown at 37°C and 250 rpm to the exponential phase to an OD600 of 0.5 to 0.6. The cultures were diluted with fresh LBG medium of pH 4.5 to an OD600 of 0.5 and then diluted 1:10 with LBG medium (pH 2.5) in 96-well microplates and incubated for 1 h at 37°C and 1,000 rpm. The cultures before and after acid shock were serially diluted, plated on LB plates, incubated at 37°C overnight, and then photographed.

Transcriptional-level analysis of gadE, gadB, ybaS, hdeB, katE, and hfq by RT-qPCR.

The total RNAs of wild-type strains MG1655 and DsrA-Hfq(WT) and mutant strains H4 and E11 were extracted from 2 OD units of overnight-cultured cells grown in LBG medium (pH 4.5, containing 2% [wt/vol] glucose) for 2, 4, 8, 12, or 24 h by using the TRIzol reagent kit (Invitrogen, CA, USA). Then the reverse transcription was performed by using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RT-qPCR assays were performed on an Applied Biosystems 7500 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) to quantitatively compare the gene transcriptional levels of gadE, gadB, ybaS, hdeB, katE, and hfq (with primers listed in Table 3). The housekeeping 16S rRNA gene was used as a control. The transcriptional levels were determined using the comparative threshold cycle number (2−△△CT) method (64). Three technical replicates of each gene and three biological replicates of each strain were analyzed to allow for statistical analysis. The transcriptional level of hfq at 4 h (exponential phase) or 24 h (stationary phase) was used to analyze the effect of the mutations in the hfq promoter on the expression level of hfq.

Ammonia and GABA release assays.

The ammonia and GABA release assays were performed as detailed in our previous report (22). Briefly, for the ammonia release assay, cells grown in LBG medium (pH 4.5) were harvested in the exponential phase at an OD600 of 0.5 to 0.6 or in the stationary phase at an OD600 of 2.0 to 3.0. The pellets were washed twice with citrate buffer (25 mM, pH 4.5) and then resuspended to 1 OD600 unit/ml with 20 ml citrate buffer (25 mM, pH 4.5) supplemented with 10 mM l-glutamine. The concentration of ammonium ions was continuously measured at 25°C using a SevenCompac S220 electrochemical analytical meter (Mettler-Toledo AG, Schwerzenbach, Switzerland). For the cell growth assay, cells grown in LBG medium (pH 4.5) were harvested in the exponential phase at an OD600 of 0.5 to 0.6 or in the stationary phase at an OD600 of 2.0 to 3.0. The pellets were washed twice with citrate buffer (25 mM, pH 4.5) and then resuspended to 4 OD600 units/ml with 1 ml citrate buffer (25 mM, pH 4.5) supplemented with 10 mM l-glutamate. After 1 h of incubation at 37°C, the cultures were centrifuged and the supernatants were filtered for the analysis of GABA concentration. The concentration of GABA was measured as previously described (65, 66).

Determination of KatE activity.

The cell extracts for the strains MG1655, DsrA-Hfq(WT), H4, and E11 in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) were obtained by sonication of 1 ml of 5 OD600 units of cultured cells grown in LBG medium (pH 4.5, containing 2% [wt/vol] glucose) for 4 h (exponential phase) or 24 h (stationary phase). The KatE activity was measured spectrophotometrically by monitoring the decrease in absorbance at 240 nm due to decomposition of H2O2 in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) at 25°C as described previously (67), using a microplate reader (Tecan Infinite; Tecan, Zurich, Switzerland).

Analysis of the RpoS protein expression level by Western blotting.

The cell extracts for the wild-type strains MG1655 and DsrA-Hfq(WT) and mutant strains H4 and E11 were obtained by sonication of 1 ml of 5 OD600 units of cultured cells grown in LBG medium (pH 4.5, containing 2% [wt/vol] glucose) for 2, 4, 8, 12, or 24 h. Samples were then suspended in SDS loading buffer, normalized against the OD600, isolated using a 12% Bis-Tris gel, and finally transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Invitrogen, USA). Membranes were probed with a 1:5,000 dilution of anti-RpoS antibody (Abcam, England). Images were obtained with a ChemiDoc MP imaging system (Bio-Rad), and the grayscale image was analyzed by ImageJ.

The effect of dsrA promoter mutation on the expression level.

mCherry fluorescent protein was used as a reporter to analyze the effect of dsrA promoter mutation on the expression level of DsrA. The strains M/PdsrA-mCherry and M/PdsrA(H4)-mCherry were incubated in LBG medium (pH 4.5) and grown at 37°C and 1,000 rpm in microplates. The OD600 and mCherry fluorescence were monitored in an Infinite 200 PRO microplate reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). The excitation and emission wavelengths used for mCherry fluorescence detection were 588 and 625 nm, respectively.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFA0901000), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2018A030313985), National Natural Science Foundation of China (21808068), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, SCUT (D2190890).

We are grateful to Sheng Yang (Key Laboratory of Synthetic Biology, CAS Center for Excellence in Molecular Plant Sciences, Institute of Plant Physiology and Ecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China) for kindly providing us with plasmids pCas and pTargetF-cadA. We also thank Marco Pistolozzi (School of Biology and Biological Engineering, South China University of Technology, China) for manuscript revision.

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patnaik R. 2008. Engineering complex phenotypes in industrial strains. Biotechnol Prog 24:38–47. 10.1021/bp0701214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Y, Tang H, Lin Z, Xu P. 2015. Mechanisms of acid tolerance in bacteria and prospects in biotechnology and bioremediation. Biotechnol Adv 33:1484–1492. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandberg TE, Salazar MJ, Weng LL, Palsson BO, Feist AM. 2019. The emergence of adaptive laboratory evolution as an efficient tool for biological discovery and industrial biotechnology. Metab Eng 56:1–16. 10.1016/j.ymben.2019.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin Z, Zhang Y, Wang J. 2013. Engineering of transcriptional regulators enhances microbial stress tolerance. Biotechnol Adv 31:986–991. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hashimoto S. 2017. Discovery and history of amino acid fermentation. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol 159:15–34. 10.1007/10_2016_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warnecke T, Gill RT. 2005. Organic acid toxicity, tolerance, and production in Escherichia coli biorefining applications. Microb Cell Fact 4:25. 10.1186/1475-2859-4-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roe AJ, McLaggan D, Davidson I, O'Byrne C, Booth IR. 1998. Perturbation of anion balance during inhibition of growth of Escherichia coli by weak acids. J Bacteriol 180:767–772. 10.1128/JB.180.4.767-772.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mills TY, Sandoval NR, Gill RT. 2009. Cellulosic hydrolysate toxicity and tolerance mechanisms in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Biofuels 2:26. 10.1186/1754-6834-2-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y, Nielsen J. 2016. Biobased organic acids production by metabolically engineered microorganisms. Curr Opin Biotechnol 37:165–172. 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao X, Jiang L, Zhu L, Xu Q, Xu X, Huang H. 2016. Tailoring of global transcription sigma D factor by random mutagenesis to improve Escherichia coli tolerance towards low-pHs. J Biotechnol 224:55–63. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dragosits M, Mozhayskiy V, Quinones-Soto S, Park J, Tagkopoulos I. 2013. Evolutionary potential, cross-stress behavior and the genetic basis of acquired stress resistance in Escherichia coli. Mol Syst Biol 9:643. 10.1038/msb.2012.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mukhopadhyay A. 2015. Tolerance engineering in bacteria for the production of advanced biofuels and chemicals. Trends Microbiol 23:498–508. 10.1016/j.tim.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guan N, Liu L. 2020. Microbial response to acid stress: mechanisms and applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 104:51–65. 10.1007/s00253-019-10226-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patnaik R, Louie S, Gavrilovic V, Perry K, Stemmer WPC, Ryan CM, del Cardayré S. 2002. Genome shuffling of Lactobacillus for improved acid tolerance. Nat Biotechnol 20:707–712. 10.1038/nbt0702-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang WT, Wu B, Qin H, Liu PT, Qin Y, Duan GW, Hu GQ, He MX. 2019. Genome shuffling enhances stress tolerance of Zymomonas mobilis to two inhibitors. Biotechnol Biofuels 12:12. 10.1186/s13068-019-1631-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harden MM, He A, Creamer K, Clark MW, Hamdallah I, Martinez KA, II, Kresslein RL, Bush SP, Slonczewski JL. 2015. Acid-adapted strains of Escherichia coli K-12 obtained by experimental evolution. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:1932–1941. 10.1128/AEM.03494-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He A, Penix SR, Basting PJ, Griffith JM, Creamer KE, Camperchioli D, Clark MW, Gonzales AS, Chavez Erazo JS, George NS, Bhagwat AA, Slonczewski JL. 2017. Acid evolution of Escherichia coli K-12 eliminates amino acid decarboxylases and reregulates catabolism. Appl Environ Microbiol 83:e00442-17. 10.1128/AEM.00442-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mundhada H, Seoane JM, Schneider K, Koza A, Christensen HB, Klein T, Phaneuf PV, Herrgard M, Feist AM, Nielsen AT. 2017. Increased production of L-serine in Escherichia coli through adaptive laboratory evolution. Metab Eng 39:141–150. 10.1016/j.ymben.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Si T, Chao R, Min Y, Wu Y, Ren W, Zhao H. 2017. Automated multiplex genome-scale engineering in yeast. Nat Commun 8:15187. 10.1038/ncomms15187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernandez-Cabezon L, Cros A, Nikel PI. 2019. Evolutionary approaches for engineering industrially relevant phenotypes in bacterial cell factories. Biotechnol J 14:e1800439. 10.1002/biot.201800439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basak S, Geng H, Jiang R. 2014. Rewiring global regulator cAMP receptor protein (CRP) to improve E. coli tolerance towards low pH. J Biotechnol 173:68–75. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao X, Yang X, Li J, Zhang Y, Chen P, Lin Z. 2018. Engineered global regulator H-NS improves the acid tolerance of E. coli. Microb Cell Fact 17:118. 10.1186/s12934-018-0966-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen T, Wang J, Yang R, Li J, Lin M, Lin Z. 2011. Laboratory-evolved mutants of an exogenous global regulator, IrrE from Deinococcus radiodurans, enhance stress tolerances of Escherichia coli. PLoS One 6:e16228. 10.1371/journal.pone.0016228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaida SM, Al-Hinai MA, Indurthi DC, Nicolaou SA, Papoutsakis ET. 2013. Synthetic tolerance: three noncoding small RNAs, DsrA, ArcZ and RprA, acting supra-additively against acid stress. Nucleic Acids Res 41:8726–8737. 10.1093/nar/gkt651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Battesti A, Majdalani N, Gottesman S. 2011. The RpoS-mediated general stress response in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Microbiol 65:189–213. 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong GT, Bonocora RP, Schep AN, Beeler SM, Fong AJL, Shull LM, Batachari LE, Dillon M, Evans C, Becker CJ, Bush EC, Hardin J, Wade JT, Stoebel DM. 2017. Genome-wide transcriptional response to varying RpoS levels in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol 199:e00755-16. 10.1128/JB.00755-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soper TJ, Doxzen K, Woodson SA. 2011. Major role for mRNA binding and restructuring in sRNA recruitment by Hfq. RNA 17:1544–1550. 10.1261/rna.2767211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gottesman S. 2019. Trouble is coming: signaling pathways that regulate general stress responses in bacteria. J Biol Chem 294:11685–11700. 10.1074/jbc.REV119.005593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murina VN, Nikulin AD. 2015. Bacterial small regulatory RNAs and Hfq protein. Biochemistry (Mosc) 80:1647–1654. 10.1134/S0006297915130027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang W, Wang L, Wu J, Gong Q, Shi Y. 2013. Hfq-bridged ternary complex is important for translation activation of rpoS by DsrA. Nucleic Acids Res 41:5938–5948. 10.1093/nar/gkt276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanjee U, Houry WA. 2013. Mechanisms of acid resistance in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Microbiol 67:65–81. 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang Y, Chen B, Duan C, Sun B, Yang J, Yang S. 2015. Multigene editing in the Escherichia coli genome via the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:2506–2514. 10.1128/AEM.04023-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feng X, Zhao D, Zhang X, Ding X, Bi C. 2018. CRISPR/Cas9 assisted multiplex genome editing technique in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol J 13:e1700604. 10.1002/biot.201700604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seo SW, Kim D, O'Brien EJ, Szubin R, Palsson BO. 2015. Decoding genome-wide GadEWX-transcriptional regulatory networks reveals multifaceted cellular responses to acid stress in Escherichia coli. Nat Commun 6:7970. 10.1038/ncomms8970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aquino P, Honda B, Jaini S, Lyubetskaya A, Hosur K, Chiu JG, Ekladious I, Hu D, Jin L, Sayeg MK, Stettner AI, Wang J, Wong BG, Wong WS, Alexander SL, Ba C, Bensussen SI, Bernstein DB, Braff D, Cha S, Cheng DI, Cho JH, Chou K, Chuang J, Gastler DE, Grasso DJ, Greifenberger JS, Guo C, Hawes AK, Israni DV, Jain SR, Kim J, Lei J, Li H, Li D, Li Q, Mancuso CP, Mao N, Masud SF, Meisel CL, Mi J, Nykyforchyn CS, Park M, Peterson HM, Ramirez AK, Reynolds DS, Rim NG, Saffie JC, Su H, Su WR. et al. 2017. Coordinated regulation of acid resistance in Escherichia coli. BMC Syst Biol 11:1. 10.1186/s12918-016-0376-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dahl J-U, Koldewey P, Salmon L, Horowitz S, Bardwell JCA, Jakob U. 2015. HdeB functions as an acid-protective chaperone in bacteria. J Biol Chem 290:65–75. 10.1074/jbc.M114.612986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu C, Chen J, Wang Y, Wang L, Guo X, Chen N, Zheng P, Sun J, Ma Y. 2019. Enhancing 5-aminolevulinic acid tolerance and production by engineering the antioxidant defense system of Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Bioeng 116:2018–2028. 10.1002/bit.26981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iwase T, Okai C, Kamata Y, Tajima A, Mizunoe Y. 2018. A straightforward assay for measuring glycogen levels and RpoS. J Microbiol Methods 145:93–97. 10.1016/j.mimet.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hwang W, Arluison V, Hohng S. 2011. Dynamic competition of DsrA and rpoS fragments for the proximal binding site of Hfq as a means for efficient annealing. Nucleic Acids Res 39:5131–5139. 10.1093/nar/gkr075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu P, Liu X, Yang L, Sun Y, Gong Q, Wu J, Shi Y. 2017. The important conformational plasticity of DsrA sRNA for adapting multiple target regulation. Nucleic Acids Res 45:9625–9639. 10.1093/nar/gkx570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santiago-Frangos A, Kavita K, Schu DJ, Gottesman S, Woodson SA. 2016. C-terminal domain of the RNA chaperone Hfq drives sRNA competition and release of target RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:E6089–E6096. 10.1073/pnas.1613053113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Botman D, de Groot DH, Schmidt P, Goedhart J, Teusink B. 2019. In vivo characterisation of fluorescent proteins in budding yeast. Sci Rep 9:2234. 10.1038/s41598-019-38913-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rugbjerg P, Sommer MOA. 2019. Overcoming genetic heterogeneity in industrial fermentations. Nat Biotechnol 37:869–876. 10.1038/s41587-019-0171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garst AD, Bassalo MC, Pines G, Lynch SA, Halweg-Edwards AL, Liu R, Liang L, Wang Z, Zeitoun R, Alexander WG, Gill RT. 2017. Genome-wide mapping of mutations at single-nucleotide resolution for protein, metabolic and genome engineering. Nat Biotechnol 35:48–55. 10.1038/nbt.3718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu R, Liang L, Garst AD, Choudhury A, Sanchez I Nogue V, Beckham GT, Gill RT. 2018. Directed combinatorial mutagenesis of Escherichia coli for complex phenotype engineering. Metab Eng 47:10–20. 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bassalo MC, Garst AD, Halweg-Edwards AL, Grau WC, Domaille DW, Mutalik VK, Arkin AP, Gill RT. 2016. Rapid and efficient one-step metabolic pathway integration in E. coli. ACS Synth Biol 5:561–568. 10.1021/acssynbio.5b00187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang K, Fredens J, Brunner SF, Kim SH, Chia T, Chin JW. 2016. Defining synonymous codon compression schemes by genome recoding. Nature 539:59–64. 10.1038/nature20124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fu J, Bian X, Hu S, Wang H, Huang F, Seibert PM, Plaza A, Xia L, Müller R, Stewart AF, Zhang Y. 2012. Full-length RecE enhances linear-linear homologous recombination and facilitates direct cloning for bioprospecting. Nat Biotechnol 30:440–446. 10.1038/nbt.2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pyne ME, Moo-Young M, Chung DA, Chou CP. 2015. Coupling the CRISPR/Cas9 system with lambda red recombineering enables simplified chromosomal gene replacement in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:5103–5114. 10.1128/AEM.01248-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sledjeski DD, Whitman C, Zhang AX. 2001. Hfq is necessary for regulation by the untranslated RNA DsrA. J Bacteriol 183:1997–2005. 10.1128/JB.183.6.1997-2005.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Battesti A, Tsegaye YM, Packer DG, Majdalani N, Gottesman S. 2012. H-NS regulation of IraD and IraM antiadaptors for control of RpoS degradation. J Bacteriol 194:2470–2478. 10.1128/JB.00132-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lalaouna D, Masse E. 2016. The spectrum of activity of the small RNA DsrA: not so narrow after all. Curr Genet 62:261–264. 10.1007/s00294-015-0533-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sharma IM, Korman A, Woodson SA. 2018. The Hfq chaperone helps the ribosome mature. EMBO J 37:e99616. 10.15252/embj.201899616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Malabirade A, Partouche D, El Hamoui O, Turbant F, Geinguenaud F, Recouvreux P, Bizien T, Busi F, Wien F, Arluison V. 2018. Revised role for Hfq bacterial regulator on DNA topology. Sci Rep 8:16792. 10.1038/s41598-018-35060-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cech GM, Szalewska-Pałasz A, Kubiak K, Malabirade A, Grange W, Arluison V, Węgrzyn G. 2016. The Escherichia coli Hfq protein: an unattended DNA-transactions regulator. Front Mol Biosci 3:36. 10.3389/fmolb.2016.00036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dos Santos RF, Arraiano CM, Andrade JM. 2019. New molecular interactions broaden the functions of the RNA chaperone Hfq. Curr Genet 65:1313–1319. 10.1007/s00294-019-00990-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hu G, Hu T, Zhan Y, Lu W, Lin M, Huang Y, Yan Y. 2019. NfiS, a species-specific regulatory noncoding RNA of Pseudomonas stutzeri, enhances oxidative stress tolerance in Escherichia coli. AMB Express 9:156. 10.1186/s13568-019-0881-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Negrete A, Shiloach J. 2015. Constitutive expression of the sRNA GadY decreases acetate production and improves E. coli growth. Microb Cell Fact 14:148. 10.1186/s12934-015-0334-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aiso T, Kamiya S, Yonezawa H, Gamou S. 2014. Overexpression of an antisense RNA, ArrS, increases the acid resistance of Escherichia coli. Microbiology (Reading) 160:954–961. 10.1099/mic.0.075994-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Delihas N, Forst S. 2001. MicF: an antisense RNA gene involved in response of Escherichia coli to global stress factors. J Mol Biol 313:1–12. 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lin Z, Chen P, Chen B, Hao X, Tong Y, Yang X, Zhang Y, Li J, Gao X. August 2018. Acid resistance expression cassette and application in organic acid fermentation thereof. Chinese patent CN201811007774.1.

- 62.Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang R-Y, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, III, Smith HO. 2009. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods 6:343–345. 10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Joo H, Lin ZL, Arnold FH. 1999. Laboratory evolution of peroxide-mediated cytochrome P450 hydroxylation. Nature 399:670–673. 10.1038/21395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Trapnell C, Hendrickson DG, Sauvageau M, Goff L, Rinn JL, Pachter L. 2013. Differential analysis of gene regulation at transcript resolution with RNA-seq. Nat Biotechnol 31:46–53. 10.1038/nbt.2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tsukatani T, Higuchi T, Matsumoto K. 2005. Enzyme-based microtiter plate assay for γ-aminobutyric acid: application to the screening of γ-aminobutyric acid-producing lactic acid bacteria. Anal Chim Acta 540:293–297. 10.1016/j.aca.2005.03.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.O'Byrne CP, Feehily C, Ham R, Karatzas KA. 2011. A modified rapid enzymatic microtiter plate assay for the quantification of intracellular gamma-aminobutyric acid and succinate semialdehyde in bacterial cells. J Microbiol Methods 84:137–139. 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Beers RF, Jr, Sizer IW. 1952. A spectrophotometric method for measuring the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide by catalase. J Biol Chem 195:133–140. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)50881-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.