Streptomyces roseoflavus Men-myco-93-63 is a biocontrol strain that has been studied in our laboratory for many years and exhibits a good inhibitory effect in many crop diseases. Therefore, the identification of antimicrobial metabolites is necessary and our main objective.

KEYWORDS: Streptomyces roseoflavus Men-myco-93-63, antibiotic, polyene macrolide, antifungal activity, biosynthetic gene cluster

ABSTRACT

A group of polyene macrolides mainly composed of two constituents was isolated from the fermentation broth of Streptomyces roseoflavus Men-myco-93-63, which was isolated from soil where potato scabs were repressed naturally. One of these macrolides was roflamycoin, which was first reported in 1968, and the other was a novel compound named Men-myco-A, which had one methylene unit more than roflamycoin. Together, they were designated RM. This group of antibiotics exhibited broad-spectrum antifungal activities in vitro against 17 plant-pathogenic fungi, with 50% effective concentrations (EC50) of 2.05 to 7.09 μg/ml and 90% effective concentrations (EC90) of 4.32 to 54.45 μg/ml, which indicates their potential use in plant disease control. Furthermore, their biosynthetic gene cluster was identified, and the associated biosynthetic assembly line was proposed based on a module and domain analysis of polyketide synthases (PKSs), supported by findings from gene inactivation experiments.

IMPORTANCE Streptomyces roseoflavus Men-myco-93-63 is a biocontrol strain that has been studied in our laboratory for many years and exhibits a good inhibitory effect in many crop diseases. Therefore, the identification of antimicrobial metabolites is necessary and our main objective. In this work, chemical, bioinformatic, and molecular biological methods were combined to identify the structures and biosynthesis of the active metabolites. This work provides a new alternative agent for the biological control of plant diseases and is helpful for improving both the properties and yield of the antibiotics via genetic engineering.

INTRODUCTION

Plant diseases constitute a substantial threat to agricultural production, and fungal plant diseases are the most widespread and devastating. Due to the extensive and long-term use of chemical fungicides, many plant-pathogenic microbes are rapidly developing resistance, and controlling the associated diseases has become increasingly difficult (1). Thus, there is a pressing need to develop new and more effective fungicides. However, screening novel synthesized compounds with bioactivity is labor-intensive and time-consuming, and ideal achievements have rarely been obtained in recent studies. Thus, the discovery of new antibiotics from natural microorganisms is a direct and effective approach to solve this problem.

The genus Streptomyces is a remarkably rich source of natural products and accounts for two-thirds of commercially available antibiotics (2). Although finding an antibiotic with a new structure is not easy after decades of exploitation, it remains possible due to the richness of microbial resources. Polyene macrolides are bioactive natural products that are mainly synthesized by Streptomycetes and related Actinobacteria. These compounds have been a focus of scientific interest since their discovery in the 1950s, and, thus far, more than 200 members have been discovered (3). Some polyene macrolides, such as amphotericin B (4), nystatin (5), candicidin (6, 7), and natamycin (8), have been used as antifungal drugs or preservative agents. In addition, researchers have revealed the biosynthesis and fungicidal mechanism of polyene macrolides. These products are synthesized from acetate, propionate, and other short-chain fatty acids via the polyketide synthesis pathway, which forms a hydroxylated macrocyclic lactone ring with three to seven conjugated double bonds and usually one or more sugars (9). This special structure accounts for the characteristic physical and chemical properties of these compounds, such as their strong light absorption, photolability, and poor solubility in water (2). The mechanism is still being actively investigated by researchers. Previous studies have shown that the direct bonding of a polyene macrolide to the main fungal sterol (ergosterol) could result in membrane permeabilization and massive loss of small molecules and ions (10–13). Some current studies have implied that, in some cases, the direct interaction between the polyene macrolide and ergosterol causes fungal death (14–16). In summary, the fungicidal action of polyene macrolide antibiotics depends on their affinity for ergosterol in fungal membranes. In addition, resistance to polyene antibiotics is considered exceptionally rare in pharmacotherapy (17, 18). Hence, these compounds have significant potential for agricultural applications in which fungicide resistance is becoming an increasingly serious problem (19).

Some new polyene macrolides have been consistently reported for plant disease control. Tetramycin, one of the effective components of agricultural antibiotic 120, exerts a good inhibitory effect against fungal diseases of vegetables, fruits, and other crops and can also stimulate growth (20). Antifungalmycin 702, isolated from Streptomyces padanus JAU4234, can effectively prevent eight plant pathogens (21). Didehydroroflamycoin (DDHR), produced by S. durmitorensis, inhibits the growth of various plant pathogens in vitro, exhibits its strongest activity against Alternaria alternata, Colletotrichum acutatum, and Penicillium expansum, and protects apple fruits from decay (22). Thailandins A and B, isolated from rhizosphere soil-associated Actinokineospora bangkokensis strain 44EHW, possess antifungal activity against anthracnose fungi and pathogenic yeasts (23).

Men-myco-93-63 is a biocontrol Streptomyces originally isolated from soil in Washington State, where potato scabs are repressed, and is related to S. roseoflavus based on their 16S rRNA gene sequences (24, 25). Based on years of research, this strain and its fermentation broth exhibit a good inhibitory effect against crop diseases such as cotton Verticillium wilt, cucumber powdery mildew, tomato gray mold, and vegetable parasitic nematodes and a significant growth promotion effect (26–28). In this study, we focused on antibiotics produced by S. roseoflavus Men-myco-93-63, particularly their chemical structures and biosynthesis.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

HPLC analysis of crude antibiotic.

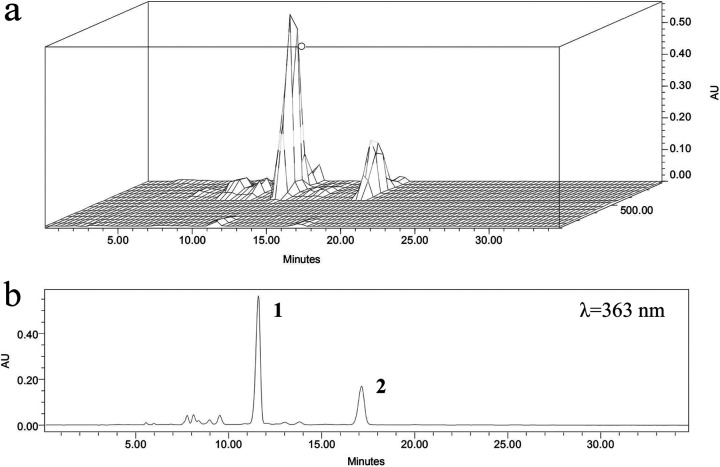

Through bioassay-guided isolation, the crude antibiotic, a yellow powder, was obtained by extraction of the fermentation broth sediment, and its inhibition effect against Verticillium dahliae is shown in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material. The high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) chromatogram (Fig. 1) indicated that the crude antibiotic consisted of two main constituents, which exhibited retention times of 11.60 min and 17.14 min. In the UV-visible absorption spectra (200 nm to 800 nm) (see Fig. S3), both compounds exhibited maximal absorption at 363 nm and a shoulder at approximately 260 nm, which are the typical UV absorption characteristics of oxo-pentaene macrolides (29). In addition, we observed some species at low abundance with retention times of less than 10 min and between 13 and 14 min, and their specific absorption spectra were identical to those of compounds 1 and 2; as a result, these compounds were also hypothesized to be oxo-pentaene macrolides. Thus, it could be assumed that S. roseoflavus Men-myco-93-63 produces a group of pentaene macrolides with antifungal bioactivity.

FIG 1.

HPLC chromatogram of crude antibiotic. (a) 3D plot (200 to 800 nm). (b) 2D plot at λ = 363 nm. Compound 1, roflamycoin; compound 2, Men-myco-A.

Antimicrobial activity of the crude antibiotic.

A toxicity test showed that the crude antibiotic exhibited a strong antifungal effect against 17 plant pathogens across 10 genera, with 50% effective concentrations (EC50) ranging from 2.05 to 7.09 μg/ml and 90% effective concentrations (EC90) ranging from 4.32 to 54.45 μg/ml (Table 1). Based on these values, the crude antibiotic was almost comparable to the positive control natamycin and even showed a better antifungal effect against some pathogens, such as Rhizoctonia cerealis, Fusarium graminearum, and Botryosphaeria berengeriana. The two compounds 1 and 2 showed equivalent antifungal activity against 5 plant pathogens, with MIC values of 20 to 40 μg/ml, and exhibited a higher level of inhibition against F. graminearum and B. berengeriana than natamycin (Table 2). The results indicated that the core polyene macrolide skeleton was the key for the activity, and the minor oxo-pentaene macrolide components probably had antifungal activity as well. Therefore, the crude antibiotic mixture has the potential to be developed as an agricultural fungicide.

TABLE 1.

Toxicity of the crude antibiotic against 17 plant-pathogenic fungi

| No. | Plant disease | Pathogen | EC50 and EC90 values (μg/ml) for: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RM |

Natamycin |

|||||

| EC50 | EC90 | EC50 | EC90 | |||

| 1 | Wheat sharp eyespot | Rhizoctonia cerealis | 2.05 | 7.44 | 6.18 | 27.17 |

| 2 | Wheat scab | Fusarium graminearum | 2.14 | 4.32 | 2.50 | 12.42 |

| 3 | Apple and pear fruit ring rot | Botryosphaeria berengeriana | 2.21 | 6.67 | 4.27 | 12.38 |

| 4 | Wheat common rot | Bipolaris sorokiniana | 2.49 | 19.87 | 1.62 | 3.59 |

| 5 | Potato early blight | Alternaria soari | 3.27 | 32.56 | 2.81 | 8.03 |

| 6 | Apple and pear Valsa canker | Valsa ceratosperma | 3.37 | 7.06 | 5.81 | 22.68 |

| 7 | Pear black spot | Alternaria alternate | 4.16 | 16.06 | 2.76 | 7.45 |

| 8 | Potato mole | Rhizoctonia solani | 4.24 | 26.87 | 0.50 | 5.20 |

| 9 | Cotton Fusarium wilt | Fusarium oxysporum | 4.43 | 14.27 | 4.61 | 14.44 |

| 10 | Apple Alternaria blotch | Alternaria brassicae | 4.51 | 14.88 | 3.22 | 12.62 |

| 11 | Celery Septoria leaf spot | Septoria apiicola | 4.73 | 24.93 | 3.69 | 13.59 |

| 12 | Tomato early blight | Alternaria solani | 5.72 | 23.13 | 2.97 | 10.63 |

| 13 | Cotton Verticillium wilt | Verticillium dahliae | 5.80 | 22.01 | 12.45 | 32.44 |

| 14 | Crucifers Alternaria leaf spot | Alternaria oleracea | 5.95 | 16.60 | 3.46 | 12.54 |

| 15 | Cotton pink smut | Cephalothecium roseum | 6.79 | 16.11 | 2.25 | 6.31 |

| 16 | Chrysanthemum root rot | Fusarium solani | 6.89 | 54.45 | 3.04 | 23.35 |

| 17 | Grape gray mold | Botrytis cinerea | 7.09 | 22.48 | 2.29 | 14.91 |

TABLE 2.

MICs of roflamycoin and Men-myco-A against 5 plant pathogens

| No. | Pathogen | MIC (μg/ml) of: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roflamycoin | Men-myco-A | Natamycin | ||

| 1 | Fusarium graminearum | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| 2 | Botryosphaeria berengeriana | 20 | 20 | 40 |

| 3 | Bipolaris sorokiniana | 40 | 40 | 10 |

| 4 | Cephalothecium roseum | 40 | 40 | 20 |

| 5 | Alternaria alternate | 40 | 40 | 20 |

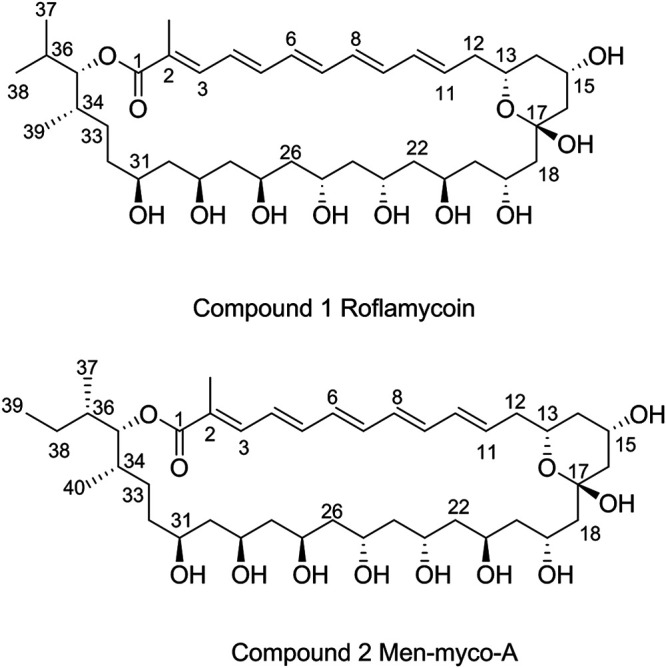

Structural elucidation of two purified compounds.

Using the procedure described in Materials and Methods, compounds 1 and 2 were obtained and analyzed by HPLC, which revealed purities of over 97.15% and 96.05% at 363 nm, respectively (Fig. S4). Based on the high-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry peaks at m/z 783.4534 [M+HCOOH-H]− (negative ion) and m/z 775.4601 [M+Na]+ (positive ion) (Fig. S5 and S6), the molecular weights of the two compounds were calculated to be 738.4364 and 752.4703, and their formulas were established as C40H66O12 and C41H68O12, respectively. The two compounds had identical UV-visible spectra and very similar one-dimensional (1D) and 2D nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra (Fig. S7 to S18), which indicated that they are structurally similar in terms of having a conjugated polyene moiety. Finally, the structures of the two purified compounds were determined using mass spectrometry, extensive NMR spectroscopy (see the supplemental material), and bioinformatic analysis (described below). Compound 1 was found to be roflamycoin (30, 31), compound 2 was a novel compound with a different side chain at C-35, named Men-myco-A, and the combination of these two compounds was designated RM (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Chemical structures of the compounds 1 and 2.

Complete genome sequencing identified the RM biosynthetic gene cluster.

To identify the gene cluster of RM, the whole genome of S. roseoflavus Men-myco-93-63 was sequenced by PacBio RSII, and one contig was obtained. The genome consisted of only one linear chromosome, with a size of 8,856,609 bp and a GC content of 72%. A total of 7,692 genes were predicted by GeneMarkS (http://topaz.gatech.edu/). An anti-SMASH analysis suggested that a total of 23 biosynthetic gene clusters, including 1,434 genes, could produce 38 secondary metabolites, including polyketides (PKs), nonribosomal peptides (NRPs), butyrolactone, thiopeptides, bacteriocins, terpenes, and other compounds. Only cluster 36, located in orf7375-7449, was predicted to produce a compound structurally similar to RM (Fig. S19). Therefore, this gene cluster was chosen as the candidate.

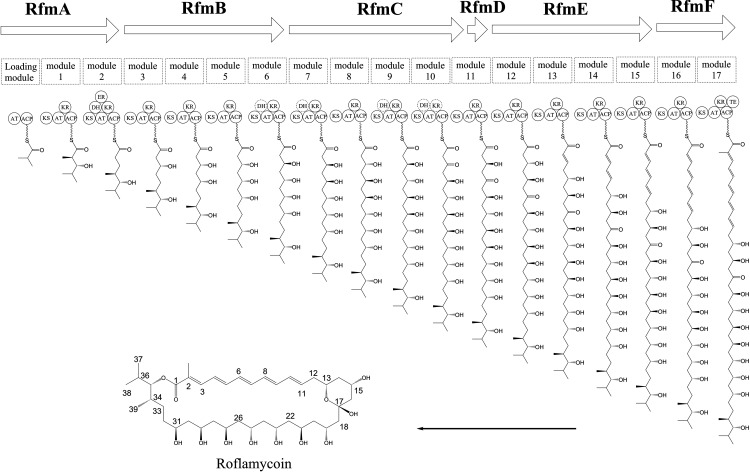

An analysis of polyketide synthase (PKS) genes in cluster 36 using the SBSPKS web server revealed six type I PKS genes totaling 88,946 bp, located in genome positions 8422031 to 8510977, and these were designated rfm genes (Fig. 3). The rfmA gene encoded a loading module and extension modules 1 and 2; the rfmB gene encoded extension modules 3 to 6; the rfmC and rfmD genes encoded extension modules 7 to 11; the rfmE gene encoded extension modules 12 to 15; the rfmF gene encoded extension modules 16 and 17; and a thioesterase domain was responsible for the dissociation of the polyketide chain from the PKSs. These genes were well aligned with the order of RM biosynthesis.

FIG 3.

Proposed biosynthetic pathway of roflamycoin. The dotted circles indicate inactivity. AT, acyl transferase; ACP, acyl carrier protein; KS, ketosynthase; DH, dehydratase; KR, ketoreductase; ER, enoyl reductase; TE, thioesterase.

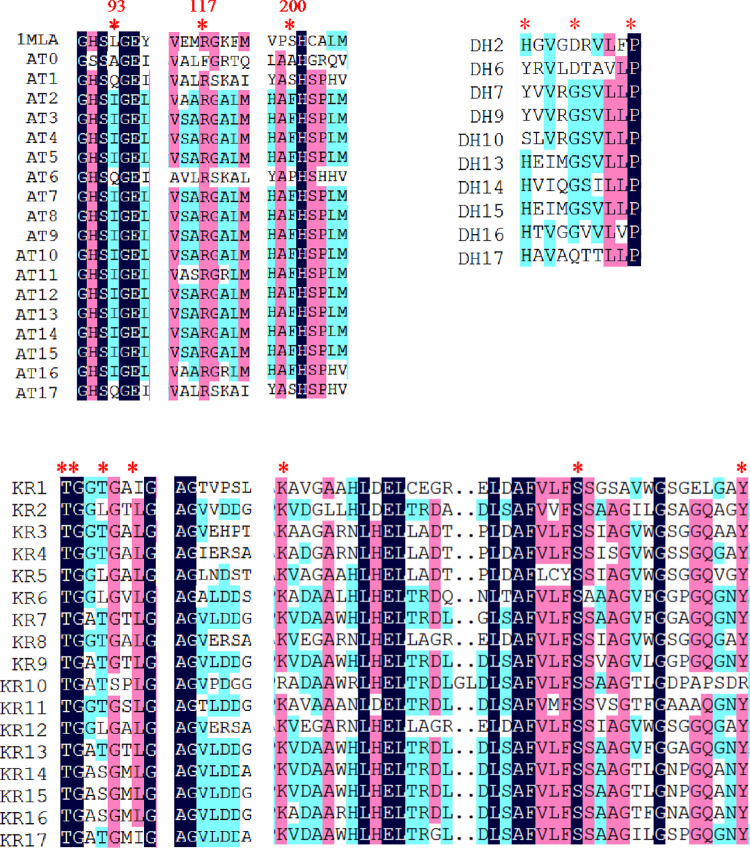

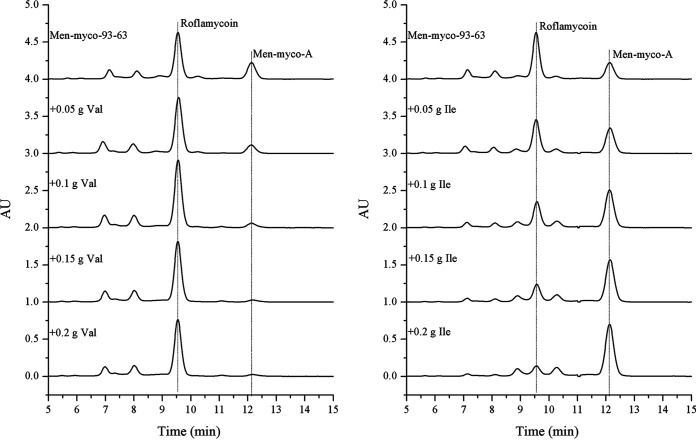

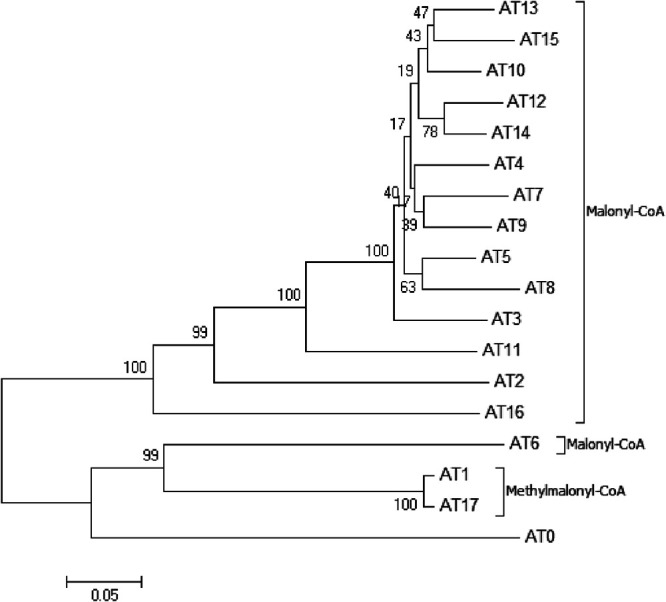

The functions of all the domains were deduced based on sequence homology alignment (Fig. 4). The substrate specificity of the acyltransferase (AT) domains was predicted by a comparison of key residues to published data (32) and phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 5). AT2 to AT16 were predicted to recognize malonyl-coenzyme A (CoA) as a substrate, whereas AT1 and AT17 were predicted to be specific for methylmalonyl-CoA. Nevertheless, the function of AT0 could not be predicted based on its key residues. According to the structures of RM, we speculated that the key amino acid residues Ala93 and Ala200 were related to a steric hindrance effect that facilitated the accommodation of isobutyryl-CoA or 2-methylbutyryl-CoA as relatively large substrates. Precursor addition experiments revealed that the addition of l-valine and l-isoleucine (whose metabolic intermediates were isobutyryl-CoA and 2-methylbutyryl-CoA, respectively) increased the yields of compound 1 and compound 2, which further proved that isobutyryl-CoA and 2-methylbutyryl-CoA were the starting substrates for RM synthesis (Fig. 6). It is generally believed that all AT domains would fail to accept 2-R methylmalonyl-CoA as a substrate unless Gly200 is present (32); thus, the substrates of AT0, AT1, and AT17 were expected to have an S-configuration, which resulted in the S-configuration at C-36 and C-34. All the KS domains contained the conserved motif CHH, which is responsible for decarboxylative condensation (33). All the acyl carrier protein (ACP) domains displayed the LGxDS motif, where Ser is essential for 4′-phosphopantetheinylation (P-Pant) attachment (34). All the KR domains, except for KR10, featured the conserved NADP(H) cofactor binding motif TGxxGxxG and the catalytic triad KSY (35), whereas in KR10, these motifs were replaced by TGxxSxxG and RSR, respectively, which resulted in loss of activity. This finding explained the formation of the keto group at the C-17 position and the subsequent formation of a hemiketal with C-13 hydroxyl. Further analysis showed that KR1, KR3-5, KR8, and KR12 could be classified as A-type with a Trp residue for catalyzing the formation of the S-configuration at C-35, C-31, C-29, C-27, and C-21 and the R-configuration at C-13, respectively, whereas KR6-7, KR9, KR11, and KR13-17 belonged to the B-type with a conserved LDD motif for generating the R-configuration at C-25, C-23, and C-19 and the S-configuration at C-15, respectively (36). The only remaining unknown stereochemical center, C-17, could not be defined with the present data. The stereochemistry of C-17 was likely determined by spontaneous cyclization during biosynthesis. The bioinformatic analysis showed that all the other stereochemical centers of compounds 1 and 2 were consistent with roflamycoin, which suggested that they formed the same stereostructure in natural products, with C-17 being in the S-configuration. The conserved dehydratase (DH) motif was HxxxGxxxxP, where the basic His residue could eliminate the proton of the polyketone chain C-2 to result in dehydration (37). Multiple-sequence alignments showed that this His residue was replaced by Tyr or Ser in DH6, DH7, DH9, and DH10; thus, these mutations were inactive. In addition, the analysis revealed that Gly was replaced in DH2 and DH17, but the RM chemical structures showed that these were still active. Therefore, this should be a catalytically active center, and although Gly is conserved, mutations in this center do not necessarily affect DH activity. Only one enoyl reductase (ER) domain was identified in module 2 with the conserved motif LxHxxxGGVGxxAxxxA, and this domain was responsible for the reduction of double bonds between C-32 and C-33 (38).

FIG 4.

Alignment of active-site sequences of AT, DH, and KR domains from RM PKSs. Only the regions containing the proposed active sites are shown. The active-site residues are marked with asterisks. The residue numbers shown in the first row of the AT alignment correspond to the positions in the E. coli FAS acyltransferase (FabD) crystal structure (PDB entry 1MLA). Arg117, which is conserved in all malonate- and methylmalonate-specific AT domains (AT1 to AT17), is the nonpolar amino acid Phe in AT0, which is specific for monocarboxylic substrates. The presence of Gln93 and Ser200 in AT1 and AT17 indicates that their substrate is methylmalonate, whereas Ile93 and Phe200 in AT2 to AT5 and AT7 to AT16 indicate that their substrate is malonate. In AT6, Gln93 indicates that its substrate is methylmalonate, whereas Pro200 indicates that its substrate is malonate; however, considering that position 200 is more selective in terms of amino acid occurrence than position 93, the substrate should be malonate, which also corresponds to the real chemical structure. The unique Ala93 and Ala200 residues in AT0 were not predicted from the key residue comparison.

FIG 5.

Phylogenetic analysis of RfmA-F AT domains. The percentages of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1,000 replicates) are shown next to the branches.

FIG 6.

HPLC analysis of the fermentation products from Men-myco-93-63 after the addition of l-valine (left) and l-isoleucine (right) into each 100-ml fermentation.

The entire assembly line for RM synthesis was the following (Fig. 5): with isobutyryl-CoA (if the final product was roflamycoin) or 2-methylbutyryl-CoA (if the final product was Men-myco-A) as the substrate, AT transfers the acyl moiety of the substrates to the ACP, which corresponds to isopropyl or 2-methyl-butyl at the C-35 position, and then transfers the product to the adjacent extension module to serve as the starting unit. The specific extensions with units of malonyl-CoA or methylmalonyl-CoA catalyzed by ATs consist of consecutive Claisen condensations that extend the polyketone chain. The full-length polyketide intermediate is then offloaded and cyclized by the dedicated RfmF-TE domain, and, subsequently, the hydroxy group at C-13 and the ketone group at C-17 form a six-membered hemiketal ring structure to generate RM.

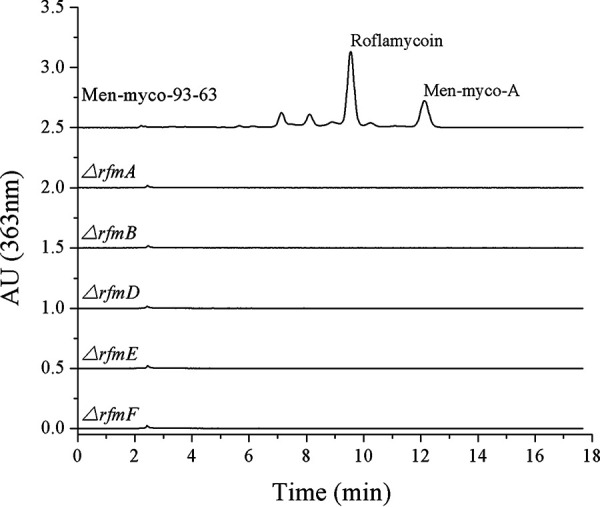

Confirmation of the function of the rfm gene cluster by gene replacement.

To determine whether this locus is indeed involved in RM biosynthesis, gene inactivation was performed. By homologous recombination and double crossover, 166 bp of the rfmA gene was replaced with a kanamycin resistance gene to obtain a gene-disrupted mutant. For amplification and verification, primers were designed to target outside the homology arms. The product size of the mutant strain was 2,548 bp, whereas the product size of the wild-type strain was 1,657 bp (Fig. S20). As expected, metabolite analysis by HPLC confirmed the absence of RM and the minor oxo-pentaene macrolide components described above in the culture broth of the mutant strain (Fig. 7). Additionally, the gene inactivation of rfmB, rfmD, rfmE, and rfmF yielded the same result (Fig. 7 and Fig. S21 to S24). These gene inactivation experiments support the finding that the rfm genes encoding the PKS enzymes are needed for oxo-pentaene macrolide complex biosynthesis.

FIG 7.

HPLC analysis of the fermentation products from Menmyco-93-63 and its ΔrfmA, ΔrfmB, ΔrfmD, ΔrfmE, and ΔrfmF gene inactivation mutants.

In summary, we isolated and identified active antifungal metabolites of S. roseoflavus Men-myco-93-63, which has been widely used for the biological control of plant diseases, and obtained a group of oxo-pentaene macrolide antibiotics that exhibit a good inhibitory effect against plant-pathogenic fungi. Their chemical structures were identified through a combination of spectrum and bioinformatic analyses. Their core skeleton was roflamycoin, which was originally isolated from mycelia of S. roseoflavus JA 5068 in 1968 (30, 31); two roflamycoin derivatives, DDHR (39) and PNG5003 (40), were isolated in 2011 and 2014, and all three compounds showed good antifungal activity. The flat structure and absolute configuration of roflamycoin were determined in 1981 and 1994, respectively (41, 42), and the total synthesis of roflamycoin was reported in 1997 (43), but the biosynthetic pathway for roflamycoin has not been elucidated to date. In our study, the biosynthetic pathway of RM was proposed based on a bioinformatics analysis and supported by findings from gene inactivation experiments. This study lays the foundation for the application of antibiotics in the future.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, chemicals, reagents, and culture conditions.

S. roseoflavus Men-myco-93-63 was deposited at the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC) with strain number 1471. Seventeen plant pathogens, Escherichia coli ET12567/pUZ8002 (44), and the plasmids pKC1139 (45) and pHB003 were maintained in our laboratory. E. coli DH5α was purchased from TIANGEN Biotech Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China).

PrimeSTAR Max premix (2×), T4 DNA ligase, restriction enzyme, MiniBEST agarose gel DNA extraction kit ver. 4.0, and MiniBEST plasmid purification kit ver. 4.0 (TaKaRa Biomedical Technology [Beijing] Co., Ltd.) were used in this study. The chromatography reagents were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), and other common biochemicals and chemicals were purchased from commercial sources.

E. coli strains, including DH5α and ET12567/pUZ8002, were cultivated at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) liquid medium or on LB agar. S. roseoflavus Men-myco-93-63 and its derivatives were cultured at 30°C in TSBY (5 g/liter yeast extract, 30 g/liter tryptic soy broth, and 103 g/liter sucrose) for DNA extraction and in MS (20 g/liter soybean meal, 20 g/liter mannitol, and 18 g/liter agar, pH 8.0) for conjugation. For fermentation, a spore suspension of S. roseoflavus Men-myco-93-63 preserved at −20°C in 20% glycerol was activated on potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium (200 g/liter potato, 20 g/liter glucose, and 18 g/liter agar) for 5 days. A PDA plate (diameter of 9 cm) with S. roseoflavus on it was then divided into eight equal sections, and each section was inoculated into 100 ml of fermentation medium (24 g/liter glucose, 8 g/liter soluble starch, 15 g/liter peanut cake powder, 8 g/liter corn paste, 4 g/liter NaCl, 3 g/liter CaCO3, and 0.2 g/liter KH2PO4) in a 500-ml Erlenmeyer flask. The fermentation mixture was incubated on a rotary shaker at 30°C and 200 rpm for 5 days. When necessary, the medium was supplemented with apramycin (50 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml), and/or kanamycin (100 μg/ml).

Extraction, HPLC detection, separation, and structural identification.

One liter of fermentation culture was centrifuged at 4,500 × g for 20 min, and the precipitate was collected. Three volumes of acetone were added, and the sample was then processed with ultrasonication for 10 min. After filtration using filter paper, the extracted solution was evaporated to dryness using a rotary evaporator at 50°C, and the resulting powder was washed with ethyl acetate. A yellow powder with a mass of approximately 0.7 g was obtained, and its biological activity against Verticillium dahliae was determined. The yellow powder was dissolved in methanol and analyzed using a Waters 600/2996 series HPLC instrument (column, Kromasil 100A, C18, 5 μm, 4.6 by 250 mm; mobile phase, water-acetonitrile (55:45); flow rate, 1 ml/min; detector, photodiode array, 200 nm to 800 nm).

The yellow powder dissolved in methanol was purified by preparative HPLC with a Waters 1525/2996 instrument (column, Waters XBridge Prep, C18, 5 μm, OBD, 19 by 150 mm; mobile phase, water-acetonitrile [55:45]; flow rate, 10 ml/min; detection wavelength, 363 nm). The mobile phase was then subjected to rotary evaporation to remove most of the acetonitrile, to vacuum freeze-drying to obtain pure solids (the whole process was conducted in the dark), and then to high-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry using a Waters ACQUITY TQD instrument and 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopy (COSY, HSQC, HMBC, and NOESY) using a Bruker AVANCE III instrument at 600 MHz to elucidate their structures.

For convenient detection of the antibiotic compounds, 1 ml of fermentation broth was directly mixed with 5 ml of methanol, and the mixture was subjected to ultrasonication for 3 min and then to HPLC analysis using an injection volume of 20 μl and a Waters 600/2996 series HPLC instrument (column, Kromasil 100A, C18, 5 μm, 4.6 by 250 mm; mobile phase, water-methanol [17:83]; flow rate, 1 ml/min; detector, UV detection at 363 nm).

Antimicrobial activity assay.

The antifungal activity was tested based on the mycelium growth rate and the inhibition zone method. For assessment of the mycelium growth rate, antibiotics were dissolved in methanol and then diluted with sterile water using the 2× method to give a range of concentrations from 40 to 1.25 μg/ml. Ten milliliters of antibiotic solution (the same solvent without antibiotics was used as the control) and 90 ml of sterile PDA medium were uniformly mixed and poured into three culture dishes (9 cm in diameter). After solidification of the mixed medium, a 7-mm mycelium block was placed on the center. The culture plates were cultivated at 28°C in the dark for several days to allow fungal growth. The colony diameters were measured when the control fungal colony reached approximately the plate edge. Toxicity regression equations (y = a + bx) were used with the probit (converted from the inhibition ratio) as y and the logarithm of concentration as x, and EC50 and EC90 values were then calculated. The lowest concentration of antibiotics that completely inhibited fungal growth was considered the MIC (46). For the inhibition zone method (used for bioassay-guided isolation), a spore suspension of the pathogenic fungus Verticillium dahliae was coated uniformly on PDA. A sterile Oxford cup with 150 μl of antibiotic solution was placed on the middle of the plate. The pathogen was then allowed to grow at 28°C in the dark until it could be observed with the naked eye. All experiments were repeated at least three times.

DNA manipulation and bioinformatic analysis.

All DNA manipulations were performed according to standard procedures or the manufacturer’s instructions (47). Plasmid extractions and DNA purification were conducted using commercial kits (TaKaRa Biotech, Dalian, China). Both primer synthesis (Table 3) and DNA sequencing were performed at Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). High-quality genomic DNA was extracted using a modified genomic DNA extraction protocol for Streptomyces (48). Genomic DNA sequencing and data analysis were performed by Novogen Biotech Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Open reading frames (ORFs) in gene cluster assignments and their proposed functions were determined using FramePlot4.0beta (49). Sequence comparisons and database searches were conducted using the BLAST algorithm (50). Domain analysis was accomplished with the SBSPKS web server (51). Additional sequence alignments were conducted using DNAMAN software.

TABLE 3.

Primer pairs used for gene inactivationa

| Gene | Primer name | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| rfmA | rfmA-UF | TAGATATCGCTCGGCACAGACGGAGAAC |

| rfmA-UR | atccccgggtaccgaGGCGTAGTAGGCGGTGAG | |

| rfmA-Km-F | cgcctactacgccTCGGTACCCGGGGATCCG | |

| rfmA-Km-R | gccaggtgggagtTGCAGGTCGACTCTAGAGATGC | |

| rfmA-DF | gagtcgacctgcaACTCCCACCTGGCGTCCTC | |

| rfmA-DR | TAGAATTCCGCCCAGTGTCTCCAGTTC | |

| rfmA-CF | ACGAACGGACCACCGACACC | |

| rfmA-CR | GCCGAGGAGAACACGACGAA | |

| rfmB | rfmB-UF | TAGATATCCCAGCAGTCCGTCATCAACCA |

| rfmB-UR | ccccgggtaccgaATCGAGTGACCGGCCAGCAC | |

| rfmB-Km-F | cggtcactcgatTCGGTACCCGGGGATCCG | |

| rfmB-Km-R | gccgggatacctTGCAGGTCGACTCTAGAGATGC | |

| rfmB-DF | gagtcgacctgcaAGGTATCCCGGCTCAAGGTCAG | |

| rfmB-DR | TAGAATTCACAGCGGTGCGTCCATGTCG | |

| rfmB-CF | TGCATCTGGCGATGGTGGC | |

| rfmB-CR | CGACTGCTCGAATCCGGTGA | |

| rfmD | rfmD-UF | TAGATATCCACCTCGTGTCGCACCCT |

| rfmD-UR | ccccgggtaccgaAGTTCATCCGCCAGCTCAC | |

| rfmD-Km-F | ggcggatgaactTCGGTACCCGGGGATCCG | |

| rfmD-Km-R | aggtgacgcggtTGCAGGTCGACTCTAGAGATGC | |

| rfmD-DF | gagtcgacctgcaACCGCGTCACCTGGCAAC | |

| rfmD-DR | TAGAATTCGCCGGACACGGAGGAGAAC | |

| rfmD-CF | CGGTTCGCCGTGTCGTCCTT | |

| rfmD-CR | CGGGTTCTGTGCGGTTGTGC | |

| rfmE | rfmE-UF | TAGATATCTGCGGGAGATGCTGTTCGG |

| rfmE-UR | ccccgggtaccgaGTGTCACCAAGGCTGGAGTGGA | |

| rfmE-Km-F | ccttggtgacacTCGGTACCCGGGGATCCG | |

| rfmE-Km-R | tcgtcgccgccgTGCAGGTCGACTCTAGAGATGC | |

| rfmE-DF | gagtcgacctgcaCGGCGGCGACGAGATGTT | |

| rfmE-DR | TAGAATTCGCCTCAAGGGCCTCACGATC | |

| rfmE-CF | GGCTGGCTTTCCTGTTCTCGG | |

| rfmE-CR | CGGTCACTGTGGTGGTCTTGC | |

| rfmF | rfmF-UF | TAGATATCGTGGCTCGGCTCGGTGAAGT |

| rfmF-UR | ccccgggtaccgaTGGCTGACCCGCAGATAGCG | |

| rfmF-Km-F | gcgggtcagccaTCGGTACCCGGGGATCCG | |

| rfmF-Km-R | tgggtcacgcccTGCAGGTCGACTCTAGAGATGC | |

| rfmF-DF | gagtcgacctgcaGGGCGTGACCCACTTCCTG | |

| rfmF-DR | TAGAATTCGGCCTGATCCGCGTCCAGT | |

| rfmF-CF | CCGCGTGTCGTACACCTTCG | |

| rfmF-CR | GAACACCGCCTCCCAGTCCA |

The underlined letters represent the restriction sites of EcoRV and EcoRI. The letters in lowercase are reverse complement sequences for overlap extension PCR.

Gene inactivation.

Two homologous arms were separately amplified from Men-myco-93-63 genomic DNA with the primer pairs rfmA-UF/R and rfmA-DF/R (Table 3). A kanamycin resistance gene (neo) was amplified from pHB003 with the primer pair rfmA-Km-F/R. The three above-described amplicons were assembled to yield an rfmA-specific disruption cassette by overlap extension PCR. After EcoRV and EcoRI digestion, the resultant PCR product was cloned into pKC1139 via T4 ligase to generate pKO7392. The delivery of the plasmid into Men-myco-93-63 was then mediated by E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002, and conjugants were selected with a 1-ml overlay of sterile water containing 0.5 mg of apramycin and 1 mg of nalidixic acid after 18 h of coculture at 30°C on an MS plate supplemented with 10 mM MgCl2. Conjugal transfer was performed according to a previously described method (52). The desired double-crossover recombinants, i.e., kanamycin-resistant and apramycin-sensitive strains, were selected after two rounds of cultivation at 37°C on PDA plates for plasmid elimination and then confirmed by PCR using the primer pair rfmA-CF/R, which binds outside the region of recombination. The rfmB, rfmD, rfmE, and rfmF genes were inactivated using the same approach.

Data availability.

The complete genome sequence of Streptomyces roseoflavus Men-myco-93-63 and the sequence of the rfm biosynthetic gene cluster have been deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers CP065959 and MT968841, respectively. Plasmids pK07392, pK07393, pK07395, pK07396, and pK07397 have been deposited into GenBank under the accession numbers MW659889, MW659890, MW659891, MW659892, and MW659893, respectively.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the National Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31972316), the Modern Agricultural Industry Technology System Innovation Team Project of Hebei Province (grant no. HBCT2018060204), and the National Key R&D Program of China (grant no. 2017YFD0200900).

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lucas JA, Hawkins NJ, Fraaije BA. 2015. The evolution of fungicide resistance. Adv Appl Microbiol 90:29–92. 10.1016/bs.aambs.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bentley SD, Chater KF, Cerdeno-Tarraga AM, Challis GL, Thomson NR, James KD, Harris DE, Quail MA, Kieser H, Harper D, Bateman A, Brown S, Chandra G, Chen CW, Collins M, Cronin A, Fraser A, Goble A, Hidalgo J, Hornsby T, Howarth S, Huang CH, Kieser T, Larke L, Murphy L, Oliver K, O'Neil S, Rabbinowitsch E, Rajandream MA, Rutherford K, Rutter S, Seeger K, Saunders D, Sharp S, Squares R, Squares S, Taylor K, Warren T, Wietzorrek A, Woodward J, Barrell BG, Parkhill J, Hopwood DA. 2002. Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Nature 417:141–147. 10.1038/417141a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Letek M, Mateos LM, Gil JA. 2014. Genetic analysis and manipulation of polyene antibiotic gene clusters as a way to produce more effective antifungal compounds, p 177–214. In Antimicrobial compounds. Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caffrey P, Lynch S, Flood E, Finnan S, Oliynyk M. 2001. Amphotericin biosynthesis in Streptomyces nodosus: deductions from analysis of polyketide synthase and late genes. Chem Biol 8:713–723. 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brautaset T, Sekurova ON, Sletta H, Ellingsen TE, StrŁm AR, Valla S, Zotchev SB. 2000. Biosynthesis of the polyene antifungal antibiotic nystatin in Streptomyces noursei ATCC 11455: analysis of the gene cluster and deduction of the biosynthetic pathway. Chem Biol 7:395–403. 10.1016/S1074-5521(00)00120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campelo AB, Gil JA. 2002. The candicidin gene cluster from Streptomyces griseus IMRU 3570. Microbiology 148:51–59. 10.1099/00221287-148-1-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen S, Huang X, Zhou X, Bai L, He J, Jeong KJ, Lee SY, Deng Z. 2003. Organizational and mutational analysis of a complete FR-008/candicidin gene cluster encoding a structurally related polyene complex. Chem Biol 10:1065–1076. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aparicio JF, Colina AJ, Ceballos E, Martín JF. 1999. The biosynthetic gene cluster for the 26-membered ring polyene macrolide pimaricin. A new polyketide synthase organization encoded by two subclusters separated by functionalization genes. J Biol Chem 274:10133–10139. 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulks MH, Nair MG, Putnam AR. 1990. In vitro antibacterial activity of faeriefungin, a new broad-spectrum polyene macrolide antibiotic. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 34:1762–1765. 10.1128/aac.34.9.1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bittman R. 1978. Sterol-polyene antibiotic complexation: probe of membrane structure. Lipids 13:686–691. 10.1007/BF02533746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolard J. 1986. How do the polyene macrolide antibiotics affect the cellular membrane properties? Biochim Biophys Acta 864:257–304. 10.1016/0304-4157(86)90002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chudzik B, Koselski M, Czuryło A, Trębacz K, Gagoś M. 2015. A new look at the antibiotic amphotericin B effect on Candida albicans plasma membrane permeability and cell viability functions. Eur Biophys J 44:77–90. 10.1007/s00249-014-1003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samedova AA, Tagi-Zade TP, Kasumov KM. 2018. Dependence of ion channel properties formed by polyene antibiotics molecules on the lactone ring structure. Russ J Bioorg Chem 44:337–345. 10.1134/S1068162018030135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Te Welscher YM, ten Napel HH, Balagué MM, Souza CM, Riezman H, de Kruijff B, Breukink E. 2008. Natamycin blocks fungal growth by binding specifically to ergosterol without permeabilizing the membrane. J Biol Chem 283:6393–6401. 10.1074/jbc.M707821200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Te WY, van Leeuwen MR, de Kruijff B, Dijksterhuis J, Breukink E. 2012. Polyene antibiotic that inhibits membrane transport proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:11156–11159. 10.1073/pnas.1203375109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gray KC, Palacios DS, Dailey I, Endo MM, Uno BE, Wilcock BC, Burke MD. 2012. Amphotericin primarily kills yeast by simply binding ergosterol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:2234–2239. 10.1073/pnas.1117280109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monk BC, Goffeau A. 2008. Outwitting multidrug resistance to antifungals. Science 321:367–369. 10.1126/science.1159746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanafani ZA, Perfect JR. 2008. Resistance to antifungal agents: mechanisms and clinical impact. Clin Infect Dis 46:120–128. 10.1086/524071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawkins NJ, Fraaije BA. 2018. Fitness penalties in the evolution of fungicide resistance. Annu Rev Phytopathol 56:339–360. 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080417-050012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao B, Yao F, Zheng X, Cui D, Shao Y, Zhu C, Deng Z, You D. 2012. Genome mining of the biosynthetic gene cluster of the polyene macrolide antibiotic tetramycin and characterization of a P450 monooxygenase involved in the hydroxylation of the tetramycin B polyol segment. Chembiochem 13:2234–2242. 10.1002/cbic.201200402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiong Z, Zhang Z, Li J, Wei S, Tu G. 2012. Characterization of Streptomyces padanus JAU4234, a producer of actinomycin X2, fungichromin, and a new polyene macrolide antibiotic. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:589–592. 10.1128/AEM.06561-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milisavljevic M, Zivkovic S, Pekmezovic M, Stankovic N, Vojnovic S, Vasiljevic B, Senerovic L. 2015. Control of human and plant fungal pathogens using pentaene macrolide 32, 33-didehydroroflamycoin. J Appl Microbiol 118:1426–1434. 10.1111/jam.12811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Intra B, Greule A, Bechthold A, Euanorasetr J, Paululat T, Panbangred W. 2016. Thailandins A and B, new polyene macrolactone compounds isolated from Actinokineospora bangkokensis strain 44EHWT, possessing antifungal activity against anthracnose fungi and pathogenic yeasts. J Agric Food Chem 64:5171–5179. 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b01119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu DQ. 1992. Biological control of Streptomyces scabies and other plant pathogens. Ph.D. thesis. University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, MN. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu ZL. 2003. Taxonomic identification of a biocontrol agent Streptomyces roseoflavus sp. Men-myco-93–63 against Verticillium dahliae and characterization of its chitinase genes. Ph.D. thesis. Hebei Agricultural University, Hebei, China. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu DQ, Yang WX, Qi BS, Wang CH. 1999. Effect of Men-myco-93–63 and its fermentation liquid on the growth of Verticillium dahliae strains of cotton. J Agric Univ Hebei 22:79–82. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo JH, Meng QF, Li YN, Yang WX, Zhang T, Zhou K, Liu DQ. 2007. Effect of the fermentation broth of Streptomyces roseoflavus Men-myco-93–63 on the resistance of cucumber powdery mildew. Acta Agricultural Boreali-Sinica 22:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qiao DN, Zhang YJ, Li HY, Shen FY, Li ZZ, Liu DQ, Li YN. 2014. Control efficacy of Streptomyces roseoflavus on root-knot nematode and its influence on soil microbiota. China Vegetables 9:30–36. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rychnovsky SD. 1995. Oxo polyene macrolide antibiotics. Chem Rev 95:2021–2040. 10.1021/cr00038a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schlegel R, Thrum H. 1968. Flavomycoin, a new antifungal polyene antibiotic. Experientia 24:11–12. 10.1007/BF02136760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schlegel R, Thrum H. 1971. A new polyene antibiotic, flavomycoin: structural investigations. J Antibiot 24:360–367. 10.7164/antibiotics.24.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yadav G, Gokhale RS, Mohanty D. 2003. Computational approach for prediction of domain organization and substrate specifcity of modular polyketide synthases. J Mol Biol 328:335–363. 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li W, Ju J, Rajski SR, Osada H, Shen B. 2008. Characterization of the tautomycin biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces spiroverticillatus unveiling new insights into dialkylmaleic anhydride and polyketide biosynthesis. J Biol Chem 283:28607–28617. 10.1074/jbc.M804279200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Staunton J, Weissman KJ. 2001. Polyketide biosynthesis: a millennium review. Nat Prod Rep 18:380–416. 10.1039/a909079g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reid R, Piagentini M, Rodriguez E, Ashley G, Viswanathan N, Carney J, Santi DV, Hutchinson CR, McDaniel R. 2003. A model of structure and catalysis for ketoreductase domains in modular polyketide synthases. Biochemistry 42:72–79. 10.1021/bi0268706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caffrey P. 2003. Conserved amino acid residues correlating with ketoreductase stereospecificity in modular polyketide synthases. Chembiochem 4:654–657. 10.1002/cbic.200300581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Debra JB, Jesus C, Stephen FH, Peter FL. 1992. 6-Deoxyerythronolide-B synthase 2 from Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Eur J Biochem 204:39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kakavas SJ, Katz L, Stassi D. 1997. Identification and characterization of the niddamycin polyketide synthase genes from Streptomyces caelestis. J Bacteriol 179:7515–7522. 10.1128/jb.179.23.7515-7522.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stodůlková E, Kuzma M, Hench IB, Cerný J, Králová J, Novák P, Chudíčková M, Savic M, Djokic L, Vasiljevic B, Flieger M. 2011. New polyene macrolide family produced by submerged culture of Streptomyces durmitorensis. J Antibiot 64:717–722. 10.1038/ja.2011.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vartak A, Mutalik V, Parab RR, Shanbhag P, Bhave S, Mishra PD, Mahajan GB. 2014. Isolation of a new broad spectrum antifungal polyene from Streptomyces sp. MTCC 5680. Lett Appl Microbiol 58:591–596. 10.1111/lam.12229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schlegel R, Thrum H, Zielinski J, Borowski E. 1981. The structure of roflamycoin, a new polyene macrolide antifungal antibiotic. J Antibiot 34:122–123. 10.7164/antibiotics.34.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rychnovsky SD, Griesgraber G, Schlegel R. 1995. Stereochemical determination of roflamycoin: 13C acetonide analysis and synthetic correlation. J Am Chem Soc 117:197–210. 10.1021/ja00106a024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rychnovsky SD, Khire UR, Yang G. 1997. Total synthesis of the polyene macrolide roflamycoin. J Am Chem Soc 119:2058–2059. 10.1021/ja963800b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6640–6645. 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bierman M, Logan R, O'Brien K, Seno ET, Rao RN, Schoner BE. 1992. Plasmid cloning vectors for the conjugal transfer of DNA from Escherichia coli to Streptomyces spp. Gene 116:43–49. 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90627-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang YF, Wei SJ, Zhang ZP, Zhan TH, Tu GQ. 2012. Antifungalmycin, an antifungal macrolide from Streptomyces padanus 702. Nat Prod Bioprospect 2:41–45. 10.1007/s13659-011-0037-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tripathi G, Rawal SK. 1998. Simple and efficient protocol for isolation of high molecular weight DNA from Streptomyces aureofaciens. Biotechnol Tech 12:629–631. 10.1023/A:1008836214495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ishikawa J, Hotta K. 1999. FramePlot: a new implementation of the Frame analysis for predicting protein-coding regions in bacterial DNA with a high G+C content. FEMS Microbiol Lett 174:251–253. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McGinnis S, Madden TL. 2004. BLAST: at the core of a powerful and diverse set of sequence analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res 32:W20–W25. 10.1093/nar/gkh435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anand S, Prasad MVR, Yadav G, Kumar N, Shehara J, Ansari MZ, Mohanty D. 2010. SBSPKS: structure based sequence analysis of polyketide synthases. Nucleic Acids Res 38:W487–W496. 10.1093/nar/gkq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kieser T, Bibb MJ, Buttner MJ, Chater KF, Hopwood DA. 2000. Practical streptomyces genetics, vol 291. John Innes Foundation, Norwich, CT. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The complete genome sequence of Streptomyces roseoflavus Men-myco-93-63 and the sequence of the rfm biosynthetic gene cluster have been deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers CP065959 and MT968841, respectively. Plasmids pK07392, pK07393, pK07395, pK07396, and pK07397 have been deposited into GenBank under the accession numbers MW659889, MW659890, MW659891, MW659892, and MW659893, respectively.