Abstract

There is a possible relationship with cerebral ischemic events and neurosarcoidosis. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis in a case of unexplained hydrocephalus, vascular white matter lesions and vasculitis related findings.

Keywords: hydrocephalus, ischemic cerebral events, neurosarcoidosis, sarcoidosis, ventriculoperitoneal shunting

There is a possible relationship with cerebral ischemic events and neurosarcoidosis. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis in a case of unexplained hydrocephalus, vascular white matter lesions and vasculitis related findings.

![]()

1. INTRODUCTION

This is a unique case describing hydrocephalus to be the primary presenting symptom of neurosarcoidosis. A 49‐year‐old woman with previous ischemic cerebral events presented with a gait disorder, urinary incontinence and cognitive impairment. Imaging showed obstructive hydrocephalus, progressive white matter abnormalities and basal leptomeningeal enhancement. Further diagnostics suggested sarcoidosis.

Sarcoidosis is a chronic, granulomatous disease of unknown etiology 1, 2 which mainly affects the respiratory and lymphatic systems. Rarely (5%‐13% of sarcoidosis patients), the central nervous system (CNS) is involved,3 or is the only affected system (1%).4 Although, post‐mortem studies suggest that ante‐mortem diagnosis is only made in 50% of patients with sarcoidosis with nervous system involvement.5 The first report of neurosarcoidosis was published in 1905.6, 7 Cranial nerve deficits are the most common clinical presentation, particularly a facial nerve palsy. Other symptoms include endocrine dysfunction, seizures, encephalopathy, peripheral neuropathy, meningitis, spinal cord dysfunction or myopathy.8 Neurosarcoidosis can present with granulomas at the surface of the brain, preferably at the skullbase , with a perivascular distribution with parenchymal involvement, or even as a tumefactive mass.9

Contrast‐enhanced MRI is the preferred examination when a granulomatous disease is suspected,10, 11 and can be used to monitor the course of the disease. A final diagnosis of sarcoidosis requires histological confirmation of a noncaseating granuloma in radiologically involved tissue.9 The differential diagnosis however is extensive due to the variation in presenting symptoms and affected organs, other pathologies thus need to be ruled out.

We describe a unique case with symptomatic hydrocephalus as the first sign of sarcoidosis. The patient's recent history of ischemic cerebrovascular disease could possibly be attributed to the previous undetected sarcoidosis.

2. CASE PRESENTATION

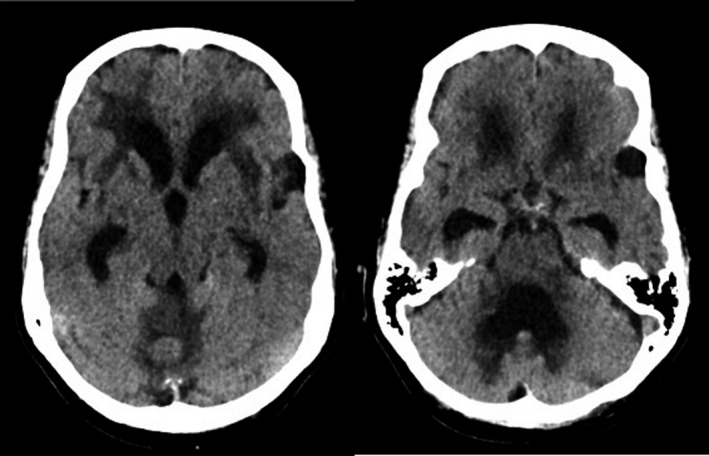

A 49‐year‐old woman was admitted to the neurology department of a teaching hospital with progressive complaints of gait disturbance, urinary incontinence, apathy, bradyphrenia and short‐term memory impairment. Within 5‐6 weeks she became unable to walk. Her medical history revealed hypertension, dyslipidemia, transient ischemic attacks (TIA’s) and a pontine stroke three years earlier. She never fully recovered from her pontine stroke with persistent complaints of cognitive impairment, fatigue and some difficulty walking. Computed tomography (CT) was performed (Figure 1 matter lesions and suspicion of vasculitis related findings) showing quadriventricular hydrocephalus compared to imaging one year earlier, as well as confluent white matter changes, most notably in the deep white matter of both frontal lobes. Repeated lumbar punctures with normal opening pressures (10‐13 mmHg) temporarily improved her clinical condition, which was objectified with a gait analysis and the cognitive complaints and incontinence improved subjectively as well. The cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed a mild lymphocytic pleocytosis (16*10E6/l), with an erythrocyte count of 0, normal glucose (2,2 mmol/l), slightly elevated proteins (0,94 g/l), albumin (655mg/l) and IgG (98 mg/l), intrathecal igG was 0mg/ml, with 5 IgG oligoclonal bands in CSF and 2 in serum. Cell count showed 0% polymorphonuclear cells and 100% mononuclear cells. Infectious and immunologic screening in CSF was negative.

FIGURE 1.

Transverse CT images without contrast show triventricular hydrocephalus, with extensive white matter changes in both frontal lobes, external capsule and around the fourth ventricle

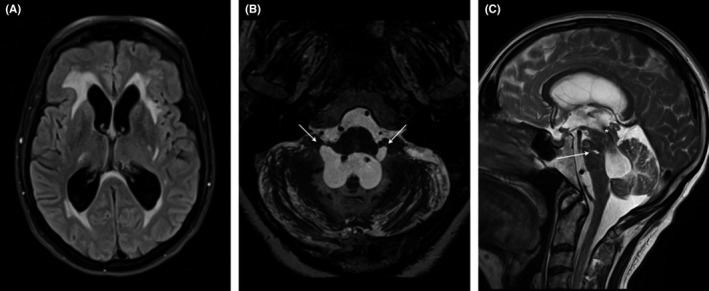

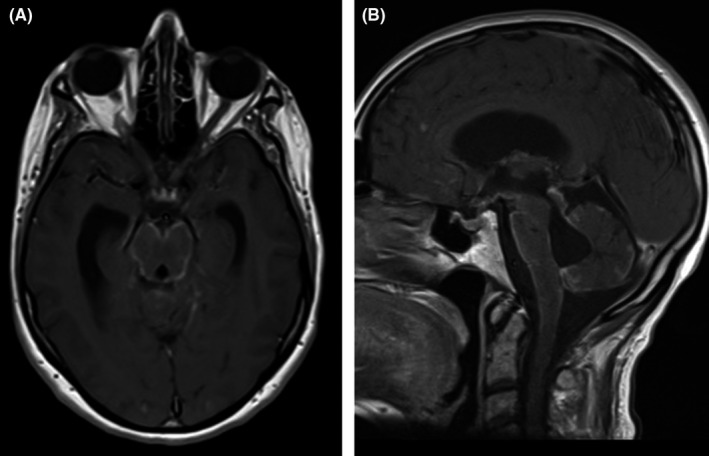

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain confirmed the hydrocephalus and frontal white matter changes, but also showed progressive white matter changes in the other lobes, basal nuclei and cerebellum compared to earlier imaging. On sagittal imaging, CSF pulsation artifacts could be appreciated in the Sylvian aqueduct, but not in the foramen magnum or around the median or lateral apertures of the fourth ventricle. Together with dilatation of the fourth ventricle and ‘ballooning’ of both lateral apertures, this suggested an obstruction of the fourth ventricle CSF outflow (Figure 2). Contrast‐enhanced MRI was performed later, showing linear and patchy enhancement within the posterior cranial fossa and basal regions of the brain (Figure 3). The patient was referred to the neurosurgery department for ventriculoperitoneal shunt (VPS) placement. Intracranial pressure appeared to be slightly elevated during surgery, although not measured.

FIGURE 2.

MRI. Transverse FLAIR A, shows dilatation of both lateral ventricles and extensive white matter changes, in which the vascular white matter lesions coalesce with the periventricular fluid accumulation due to hydrocephalus. 1mm maximum intensity projection (MIP) of high resolution T2 weighted sequence B, illustrates the ‘ballooning’ of the lateral foramina of Luschka (arrows). Sagittal T2‐weighted image C, shows dilatation of the fourth ventricle, with a prominent flow artifact over the cerebral aquaduct (*). Arrow points to a lacune in the pons

FIGURE 3.

Transverse A, and sagittal B, contrast‐enhanced T1 weighted images show a pattern of basal leptomeningeal enhancement in the posterior fossa and basal portions of the brain

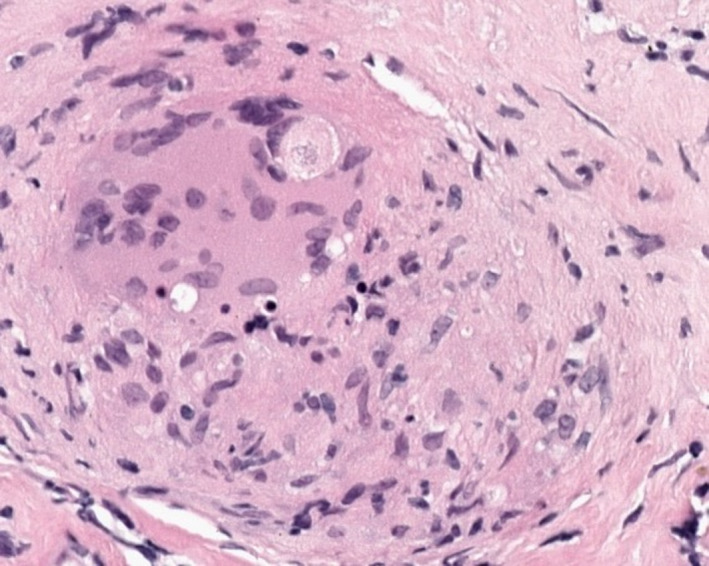

Analysis of peroperative obtained CSF showed no malignant cells; a fluorescence‐activated cell sorting (FACS) ‐analysis could not be performed due to the low cell count. Due to the differential diagnosis of leptomeningeal metastases, basal leptomeningitis (including granulomatous disease), vasculitis, lymphoma, auto‐immune or paraneoplastic pathologies, a PET‐CT was performed. The PET‐CT showed supraclavicular, mediastinal and parailliacal lymphadenopathy. An ultrasound‐guided puncture was performed in the supraclavicular lymph node. Histological examination showed a granulomatous disease with a strong preference for sarcoidosis (Figure 4). This was confirmed by a second puncture of one of the PET‐positive lymph nodes. Both a Mantoux test and a PCR for Mycobacterium tuberculosis proved negative and tuberculosis was thus excluded.

FIGURE 4.

Histology of lymph node biopsy showing a noncaseating granuloma

3. DISCUSSION

Sarcoidosis is a multi‐systemic disease, characterized by cellular immunity activity with formation of noncaseating granuloma in various organ systems. Diagnosis of sarcoidosis is often a complex, time‐consuming trajectory due to the variety of clinical presentations and the fact that laboratory blood and CSF examination is frequently unspecific. As seen in our patient; mononuclear inflammatory cells, elevated protein and occasionally low glucose. Three criteria are required to diagnose sarcoidosis: clinical and matching radiologic manifestations, a histological prove of a noncaseating granuloma and the exclusion of alternative diseases. The Neurosarcoidosis Consortium Consensus Group has developed a diagnostic criterion for neurosarcoidosis.3, 9 Cranial and peripheral neuropathies are the major presenting symptoms, together with myopathy, seizures, gait disorders and cognitive decline. In 1%‐7% the vestibulocochlear nerve is affected.12, 13 In the present case, involvement of VIIIth cranial nerve could be suspected due to her unsteadiness with walking.

Neurosarcoidosis in the basal leptomeninges appears as thickening and enhancement (either focal, multifocal or diffuse) on gadolinium‐enhanced T1‐weighted MRI. It is usually indistinguishable from the pattern seen in tuberculous meningitis or CNS lymphoma,8 which both may have a similar clinical presentation. Therefore, a histological diagnosis of the radiological aberrant tissue is necessary. In tuberculous meningitis, the basal leptomeningeal involvement is known to be due to extension and/ or rupture of a Rich focus (subpial or subependymal focus) to the subarachnoid spaces and ventricular system, which causes enhancement of the exudate.14 A similar mechanism in neurosarcoidosis has not been described.

Parenchymal involvement often follows a perivascular spread, with T2/FLAIR hyperintense white matter changes and / or perivascular enhancement.15 The progressive T2 hyperintensities in the deep white matter, observed in our patient, should be interpreted as parenchymal involvement.

The question remains whether the ischemic strokes and progressive vascular white matter changes in our patient, as a consequence of small‐vessel disease, can be attributed to neurosarcoidosis. Although rarely, it has been reported that neurosarcoidosis can cause arterial and venous ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes or TIA’s due to granulomatous inflammation of intracranial blood vessels.15 This has mainly been described in medium and small vessels, literature of large vessel involvement is scarce and is thought to be due to compression by granuloma's rather than granulomatous inflammation or vasculitis 1516.

There is still some uncertainty about the underlying pathophysiological mechanism of stroke‐like symptoms in patients with sarcoidosis. A retrospective study evaluated patients with sarcoidosis‐related strokes and concluded that a stroke was the first presenting symptom in 40% of the patients.16 In about 92% of neurosarcoidosis patients presenting with stroke, sarcoidosis appeared to be present in other non‐nervous systems after additional examination. The authors suggest that the granulomatous invasion of the blood vessel walls is the mechanism behind sarcoidosis‐related cerebrovascular events rather than sarcoidosis‐related vasculitis. It is thought that vasculitis due to sarcoidosis is more commonly resulting in a slowly progressive encephalopathy than an ischemic stroke.17 A mortality rate of 23% is reported in sarcoidosis patients presenting with stroke.16

Due to the three‐year time interval between stroke and diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis, it remains debatable whether this could have been a first warning sign of neurosarcoidosis in our patient.

Hydrocephalus is described to emerge in the course of neurosarcoidosis in 5 to 12% of affected individuals.4 Usually, this is a communicating hydrocephalus as a consequence of a decrease in CSF resorption due to leptomeningeal involvement. Though, CSF outflow obstruction caused by involvement of the basal leptomeninges in the inflammatory process and consequent adhesions, loculations in the ventricular system or infiltration of the choroid plexus can also lead to hydrocephalus.8, 18

Scarce literature is available on the treatment of neurosarcoidosis and is mainly based on expert opinion and small retrospective studies. Typically, initial treatment consists of corticosteroids, although the exact mechanism is still unknown. It is hypothesized that the benefit is due to the anti‐inflammatory and immune‐modulating effects.11, 19 The benefit of this treatment varies widely from substantial improvement to no improvement at all. As a second step, a steroid‐sparing or second‐line agent, like Methotrexate (MTX) or mycophenolate can be considered. When the need for immunosuppressive treatment is chronic, upfront start of combination therapy of both corticosteroids and a steroid‐sparing or second‐line agent can be preferred. Further treatment options include TNF‐alpha inhibitors such as infliximab, although treatment is expensive and poses a higher risk for infections and other toxicities.9, 19

4. CONCLUSION

The present unique case illustrates a rare presentation of sarcoidosis, with symptoms related to obstruction hydrocephalus. We discuss the possible relationship with a previous episode of multiple cerebral ischemic events and neurosarcoidosis. The causes of hydrocephalus are most frequently a combination of CSF obstruction and disturbed resorption mechanisms due to basal meningeal granulomatous and inflammatory adhesions. Neurosarcoidosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis in a case of unexplained hydrocephalus, vascular white matter lesions and suspicion of vasculitis related findings.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

VS, EY: data collection and drafting of the manuscript. WH, RH: radiologic data collection, images and description, critically revising manuscript. WV: pathologic data collection, images and description. LA, RM, RP, OS: critically revising manuscript.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

Ethics approval was not required for this study.

PATIENT CONSENT

The patient has consented to the submission of the case report for submission to the journal.t

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are thankful to the patient for cooperating in the writing of this manuscript. Published with written consent of the patient.

Schuermans VNE, Yeung E, Henneman WJP, et al. Neurosarcoidosis with hydrocephalus as a first presenting sign; case report. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9:e03776. 10.1002/ccr3.3776

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author VS. The data are not publicly available to protect the privacy of the patient.

REFERENCES

- 1.Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(21):2153‐2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lower EE, Broderick JP, Brott TG, Baughman RP. Diagnosis and management of neurological sarcoidosis. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(16):1864‐1868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stern BJ, Krumholz A, Johns C, Scott P, Nissim J. Sarcoidosis and its neurological manifestations. Arch Neurol. 1985;42(9):909‐917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith JK, Matheus MG, Castillo M. Imaging manifestations of neurosarcoidosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182(2):289‐295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoitsma E, Faber CG, Drent M, Sharma OP. Neurosarcoidosis: a clinical dilemma. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3(7):397‐407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burns TM. Neurosarcoidosis. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(8):1166‐1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colover J. Sarcoidosis with involvement of the nervous system. Brain. 1948;71(4):451‐475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ginat DT, Dhillon G, Almast J. Magnetic resonance imaging of neurosarcoidosis. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2011;1:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stern BJ, Royal W 3rd, Gelfand JM, et al. Definition and Consensus Diagnostic Criteria for Neurosarcoidosis: From the Neurosarcoidosis Consortium Consensus Group. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(12):1546‐1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zajicek JP, Scolding NJ, Foster O, et al. Central nervous system sarcoidosis–diagnosis and management. QJM. 1999;92(2):103‐117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lacomis D. Neurosarcoidosis. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2011;9(3):429‐436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yacoub HA, Al‐Qudah ZASN. Cranial neuropathies in sarcoidosis. World J Ophthalmol. 2015;5(1):16‐22. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krumholz A, Stern BJ, Stern EG. Clinical implications of seizures in neurosarcoidosis. Arch Neurol. 1991;48(8):842‐844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knapen SE, P. Goswani KMAV. Uw Diagnose? Tijdschr Neurol Neurochir. 2019;120(4):161‐163. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bathla G, Singh AK, Policeni B, Agarwal A, Case B. Imaging of neurosarcoidosis: common, uncommon, and rare. Clin Radiol. 2016;71(1):96‐106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jachiet V, Lhote R, Rufat P, et al. Clinical, imaging, and histological presentations and outcomes of stroke related to sarcoidosis. J Neurol. 2018;265(10):2333‐2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown MM, Thompson AJ, Wedzicha JA, Swash M. Sarcoidosis presenting with stroke. Stroke. 1989;20(3):400‐405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hesselmann V, Wedekind C, Terstegge K, et al. An isolated fourth ventricle in neurosarcoidosis: MRI findings. Eur Radiol. 2002;12(Suppl 3):S1‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voortman M, Fritz D, J.M. Vogels O, et al. Clinical Manifestations of Neurosarcoidosis in the Netherlands. J Neurol Neurosci. 2019;10(2):292. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author VS. The data are not publicly available to protect the privacy of the patient.