ABSTRACT

Aim:

This narrative aims to outline the use of hypnosis in managing dental anxiety in during dental treatment. The PICO used to answer the objectives are (P) dental patients, (I) hypnosis, (C) conventional behaviour management techniques & (O) reduced pain/anxiety.

Materials and Methods:

An electronic search of three databases; PubMed, Scopus and EBSCOhost was conducted using the keywords “hypnosis or hypnotherapy” AND “dentistry or dental” between the year 2000 and 2020. A total of 19 studies were selected based on eligibility. Data extracted were study subject, design of study, parameters used to assess, type of hypnosis script used and the study outcome.

Results:

The studies show that hypnosis is effective in pain management and dental anxiety. It can also be used for improving compliance in patients who are wearing orthodontic appliances (Trakyali et al, 2008) and reducing salivary flow during dental treatment (Satlz et al, 2014).

Conclusion:

Hypnosis has the potential to be a useful tool in the management of children and adults.

KEYWORDS: Dental anxiety, dental pain, hypnosis, hypnotherapy

INTRODUCTION

Dental anxiety refers to an elevated fear of dental procedures, an emotional or physical state which occurs before the encounter with an object or procedure.[1,2] The prevalence of dental anxiety is thought to be between 10% and 20%, but there have been studies which found up to 58% of patients having anxiety toward dental treatment.[1,3] Anxiety is of great concern for dentistry as it is considered an oral health problem, which can result in avoidance of dental treatment and eventually leading to a higher prevalence of untreated dental diseases.[1] This essentially leads to a vicious cycle of dental anxiety that causes delay in visiting the dentist, which in turn worsens the dental problem and the behavior of symptom-driven treatment feeds back into the fear experience.[4] In short, dental anxiety can be detrimental to the patient’s oral health and should be addressed as soon as it is detected.

In the context of dental fear and anxiety, one can never ignore the topic of pain. Although pain has a clear physiological process which is the pain pathway, it also has a strong cognitive component. This means that a person who already has dental anxiety may have an exaggerated pain perception and experience.[5] Similarly, pain has been established as the a reason for dental anxiety and it has the potential to create a negative dental experience.[2]

Conventional nonpharmacological behavior management techniques have been used to manage patients with dental anxiety and improve pain tolerance.[6] Among the vast list of techniques, which ranges from effective communication to protective stabilization, and old but less used technique lies hidden away, which is hypnosis. Although it has been recognized as a useful tool in dentistry, this technique is underused and a reason for this may be the lack of knowledge among dentists about this therapy.[7]

The basis on which hypnotherapy works is getting the patient into an altered state of consciousness, a state whereby the patient is more relaxed and more receptive to suggestions. The response during a hypnosis session is not brought about by the practitioner but it is elicited by the patient’s own will. The definition of suggestion as stated by Heap and Aravind[8] is comprehensive and concise:

“A communication conveyed verbally by the hypnotist, that directs the subject’s imagination is such a way as to elicit intended alterations in sensations, perceptions, feelings, thoughts and behavior.”

People are frequently experiencing hypnosis in their daily lives without even realizing it. Daydreaming is a perfect example of how we are able to be alert to our changing surroundings while being in a state of altered consciousness.[8] In fact, many dentists already practice some form of hypnosis by using the right language and positive reinforcement which we have been taught to do and this is referred to as the “chairside manner.” The intonation and words used when dealing with a patient is capable of providing a relaxed state even without formal hypnotic induction.[9] Hypnosis can be used on its own or as an adjunct to other available behavior management techniques. The use of suggestions makes it suitable for use with nitrous oxide inhalation sedation but there is lack of research and clinical reports in this area.[10]

The opinion regarding the ease of use of hypnosis in various age categories has been conflicting. Gokli et al.[11] suggested that hypnosis is more useful in 4–6 years olds, whereas Wood and Bijoy[12] believe that children under 6 years old are not suitable for this technique due to and maintains that children between 7–14 years stand to benefit the most. This discrepancy in recommendation of appropriate age for clinical hypnosis could be due to the varying mental age staging in children and hence chronological age should not be the sole indicator.[13] Santos et al.[14] highlighted the fact that despite the promising results seen with the use of hypnosis in children, it is still underused.

Apart from the limitation of use in patients who are too young or are unable to understand the hypnosis scripts, this therapy will only work with patients who are hypnotizable. An estimated 80% of the population are hypnotizable and thus would be a good modality to pursue.[7]

Where research regarding the effects of hypnotherapy is concerned, the parameters most commonly assessed are pain and anxiety. The normal reaction to pain occurs through the nervous communication and cognitive channels and hypnosis creates a communication barrier, which cuts off the recognition of pain and in turn creating a state of relaxation.[15] Anxiety is also of great interest to dentists as an anxious patient requires more time on the dental chair and increases the cost of treatment. The paper by Al-Namankany et al.[16] shares the extensive list of dental anxiety scales, which are suitable for children. Although we are unable to single out any one technique as the gold standard for assessing anxiety, there are a number of methods which have been tested for reliability and validity and are suitable for research use. Common scales for observer reporting are Behavior Profile Rating Scale, Houpt Categorical Rating Scale, Global Rating Scale and Venham Anxiety and Behavior Rating Scales. Self-reported scales include Facial Image Scale, Venham Picture Test, Dental Anxiety Scale and Modified Child Dental Anxiety Scale. Bio-feedback parameters which are useful in measuring pain and anxiety are heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation level.[16]

It is therefore important to establish the current trend in research involving hypnosis in dentistry and identify the common tools used to measure the outcome so that we can better plan future research in this field. The objectives of the literature search were based on the PICO statement as per the following: patient population (patients attending dental treatment), intervention (hypnosis), comparator (other behavior guidance techniques), and outcomes (reduced pain/anxiety). The authors also sought to determine the common type of hypnotic scripts used and the common parameters used to assess the effectiveness of hypnosis in dental treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PRISMA guideline was adhered to for the literature search of this review.[17] Search engines used were primarily PubMed, EBSCOhost, and SCOPUS. The keywords used were “hypnosis or hypnotherapy” AND “dentistry or dental.” Studies included in this review are cohort studies, cross-sectional, case-control and randomized control studies. Only literatures in the English language were included and the time frame was set between January 2000 to January 2020. Reference lists from eligible studies were examined for additional references.

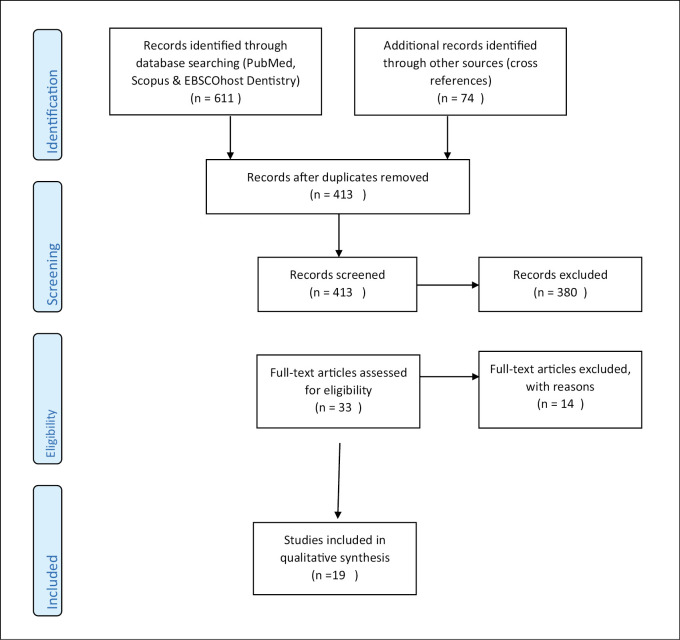

This review looks at the current trend in research pertaining to the use of hypnosis in dentistry and the common tools used to measure the results. The initial search generated 611 titles from three databases which are PubMed, Scopus, and EBSCOhost Dentistry. A cross-reference of references from obtained paper generated another 74 titles. After removal of duplicates, 413 titles remained and were scrutinized. A total of 380 articles were removed from the list as they were either not in the English language or were not clinical studies but reviews instead. Further screening left us with 33 articles for consideration. From this list, another 14 articles were excluded with reason. The final review included 19 articles [Figure 1]. Data extracted were study subject, design of study, parameters used to assess, type of hypnosis script used and the study outcome.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of literature inclusion according to PRISMA guidelines[17]

DISCUSSION

The studies included in this review were clinical trials, case controls, and cohort studies [Table 1]. The selected studies were conducted within a range of 20 years from January 2000 to January 2020. The studies showed a variety of cases where the use of hypnosis has proven effective. Hypnosis has been used for the following purposes:

Table 1.

Type of hypnosis used in dental treatment and the parameters used to measure it

| Author, year | Subjects | Design of study | Parameters measured | Hypnosis used | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghoneim et al. (2000)[18] | n = 60Age: 18–35 years | Controlled trial. Surgical removal of third molar under LA. Hypnosis vs. nonhypnosis groups | 1. Speilberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory2. Nausea3. Pain | Favorite place of relaxation, direct suggestions to alleviate pain, control bleeding. Recorded script. | Recorded hypnosis successful in reducing anxiety but a side effect of vomiting was noted among the subjects. |

| Moore et al. (2002)[19] | n = 206Age: 19–65 years | Controlled trial. Assessment of anxiety when undergoing restorative treatment in 4 groups (hypnosis, group therapy, systematic desensitization and control) | 1. Dental anxiety score2. Dental fear survey3. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory4. Modified Geer Fear Score | Reframing negative thoughts, Dissociation, project anxiety on wall and try to get to the other side. Recorded script. | Intervention groups were better dental attenders and showed reduced anxiety. Hypnosis showed most attrition of patients |

| Abrahamsen et al. (2008)[22] | n = 41Mean age = 56 ± 1.9 years | Controlled trial. Assessment of pain in patients with persistent idiopathic orofacial pain (PIOP) | 1. VAS pain score2. McGill pain questionnaire 3. Use of analgesics4. Perceived pain area5. Sleep quality6. SF36 QOL questionnaire7. Coping strategy questionnaire | Progressive muscle relaxation, pain suggestions, ego strengthening, guided imagery, dissociation and reframing | Use of hypnosis as an adjunct to weak analgesics effectively reduces pain in patient with PIOP |

| Trakyali et al. (2008)[29] | n = 30Age : below 12 years | Total time headgear worn assessed between two groups (motivation with hypnosis vs. regular motivation) | Total number of hours headgear worn calculated using timing headgear | Not mentioned | Hypnosis is an effective method for improving orthodontic patient cooperation |

| Abrahamsen et al. (2009)[23] | n = 43Mean age: 38.6 ± 10.8 years | Controlled trial. Assessment of temperomandibular disorder (TMD) related pain in 2 groups (hypnosis vs. simple relaxation) | 1. Pain score 2. McGill pain3. Pain on palpation of TMD 4. Symptom check list (SCL-60)5. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) | Progressive relaxation, guided imaginary instructions. Recorded script. | Significant reduction of pain in hypnosis group |

| Eitner et al. (2010)[30] | n = 102Mean age = 41.3 years | Controlled trial. Management of hypersensitivity In 4 groups (fluoride therapy, desensitizer, hypnosis & control group) | 1. VAS pain score2. Satisfaction questionnaire | Focus of attention, progressive muscle relaxation, remove pain from particular area. | Overall all three interventions were better than control but no significant differences between the 3 groups. Immediate effect more obvious in desensitizer and hypnosis groups |

| Mackey (2010)[36] | n = 91Age: 18–25 years | Randomized control trial. Third molar removal done under 2 conditions (iv sedation with hypnosis vs. iv sedation with music) | 1. Anesthetic drug amount required2. VAS for pain intensity3. Amount of post-op analgesics required | Hypnosis script not described. Type of music also not stated. Recorded script. | Hypnosis as adjunct to IV causes: |

| i. Reduced amount of intraoperative propofol | |||||

| ii. Reduced post operative pain | |||||

| iii. Reduced amount of postoperative analgesics | |||||

| Wannemueller et al. (2011)[24] | n = 137 Age : not specified | Controlled trial. Anxiety levels in patients undergoing dental treatment under 4 different behavior guidance techniques (CBT, individualized hypnosis, standard recorded hypnosis, general anesthesia) | 1. Hierarchical Anxiety Questionnaire2. Dental anxiety scale3. Dental cognition questionnaire4. Revised Iowa dental control index5. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory6. Subjective rating by patient | Not mentioned. Both recorded and face to face hypnosis used. | 1. CBT more effective than individualized hypnosis2. Individualized hypnosis better than standard recording |

| Facco et al. (2011)[32] | n = 31 Mean age: 28 ± 4.6 years | Controlled trial. Pain threshold measured 3 time (before, during and after hypnosis) | Pain threshold measured using electric pulp tester | Focus of attention, progressive muscle relaxation, arm levitation | Hypnosis increased pain threshold |

| Eitner et al. (2011)[20] | n = 82 Age: 19–80 | Controlled trial. Anxiety and physiological changes measured for patients undergoing implant surgery (use of audio pillow with hypnosis and music vs. pillow without any hypnosis or music) | 1. Blood pressure2. Heart rate3. Capillary oxygen partial pressure4. AZI questionnaire (modified CDAS in German) | Dissociation, favorite place of relaxation, 'internal guard' | Hypnosis and music group had intraoperatively lower blood pressure and heart rate. Patients in this intervention group also felt more comfortable during surgery |

| (mean = 50.7 years) | |||||

| Huet et al. (2011)[25] | n = 29 children Age: 7–12 years | Controlled trial. Anxiety and pain assessed patients receiving local anesthesia in 2 groups (LA only vs. LA and hypnosis | 1. Modified Yale preoperative anxiety scale2. Modified objective pain score | Customized scripts based on patient's interest | Reduced anxiety by 50% in hypnosis group as compared to control group |

| Abdeshahi et al. (2013)[21] | n = 24Age > 18 years (mean = 24.1 ± 2.7 years) | Case control. Removal of third molar done using two protocols (surgery with LA vs. surgery with hypnosis) | 1. VAS pain score2. Speilberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory3. Hemorrhage assessment postoperatively | Chiasson's technique, Fix gaze on one point, glove anesthesia | Patients have less pain and bleeding when removal of third molar done under hypnosis |

| Satzl et al. (2014)[26] | n = 31Age: 18–63 years | Randomized control trial. Salivary flow rate assessed when hypnosis given via two methods (direct suggestion vs. indirect suggestion) | Unstimulated salivary flow rate | Direct suggestion: Focus on breathing relax and reduce saliva production | Both direct and indirect hypnosis techniques reduce salivation |

| Indirect suggestion: | |||||

| Script relating to dry season and desert | |||||

| Glaesmer et al. (2015)[27] | n = 102 Age > 18 years | Controlled trial. Anxiety and attitude assessed before, during and after permanent tooth extraction done (LA only vs. LA and hypnosis) | 1. VAS to assess anxiety (3 stages)2. Questionnaire assessing attitude toward hypnosis | Reference to a positive experience in the past, sound manipulation, dissociation, suggestions about reduced pain and increased bloodflow. Recorded script. | Significantly less anxiety in hypnosis group only during treatment, no significant difference before and after extraction |

| Wolf et al. (2016)[31] | n = 37 Age: 21–54 | Randomized control trial. Stimulation of dentin-pulp complex with and without hypnosis | 1. Pain threshold (vitality scanner)2. VAS pain score3. Hemodynamic parameters | Favorite place of relaxation, glove anesthesia (protective hand), dissociation, inner resource. Self hypnosis | Significant reduction in pain intensity and significant increase in pain threshold in hypnosis group |

| (mean age = 27.7 ±7.85) | |||||

| Oberoi et al. (2016)[28] | n = 200Age: 6–16 years (mean = 9.8 years) | Controlled trial. Anxiety assessed during inferior dental nerve block (LA only vs. LA and hypnosis) | 1. Pulse rate2. Oxygen saturation | Arm levitation, progressive muscle relaxation | Hypnosis lowers heart rate and decreases resistance toward treatment |

| Wolf et al. (2016)[33] | n = 34Age: 21–54 years (mean = 27.8 ± 7.97 years) | Randomized control trial. Pain threshold assessed in two groups (LA only vs. hypnosis) | VAS pain score | Favorite place of relaxation, automatic responding protective hand, dissociation | Hypnosis reduced anxiety, pain and bleeding |

| Vitality scanner | |||||

| Hemodynamic parameters | |||||

| Ramírez-Carrasco et al. (2017)[34] | n = 40Age: 5–9 years | Randomized control trial. Both groups have headphones but only experimental group listens to taped hypnosis. Both groups have conventional BMT | 1. FLACC2. Heart rate3. Skin conductance | Progressive muscle relaxation with “garden with fountain.” Ideomotor signal. Recorded script | 1. No significant difference in FLACC2. Difference of 5 beats per minute for heart rate3. No significant difference in skin conductance |

| Park et al. (2019)[35] | n = 63Age: 30–59 years | Randomized control trial. Patients undergoing periodontal treatment were assessed for anxiety and physiological changes in two groups (hypnosis vs. oral health education) | 1. Dental anxiety score2. Depression questionnaire3. Saliva cortisol level4. Blood pressure5. Pulse rate | Progressive muscle relaxation | Hypnosis reduced anxiety, depression symptom, blood pressure, pulse rate and salivary cortisol level |

i. As an adjunct anxiolytic agent for minor oral surgery[18,19,20,21]

ii. Reduce the intensity of pain in orofacial and temporomandibular pain[22,23]

iv. Increase compliance of wearing orthodontic headgear[29]

vii. Reduce salivary flow during dental treatment[26]

There were 4 studies that specifically looked at the use of hypnosis in the pediatric age group of below 16 years of age.[25,28,29,34] Three of these studies assessed the effects of hypnosis on anxiety during administration of local anesthetic,[25,28,34] whereas the remaining study in children looked at compliance of wearing a headgear.[29] Anxious patients made up the bulk of the subject population and their level of anxiety was determined using anxiety scales. Patients with severe phobia were excluded from the studies.[18,19,21,24,25,35]

The delivery of hypnotic scripts were done using face to face sessions (63%),[21,22,24,25,26,28,29,30,31,32,33,35] audio CD (32%)[18,19,23,26,32,36] and audio pillow.[20] Majority of the studies included a progressive muscle relaxation (42%)[19,22,23,28,30,32,34,35] in their hypnosis script. This procedure involves the suggestion of “relaxing,” “limbs becoming heavy” beginning from either the head to toes or the reverse.[1] It is wise to establish a “safe place” or “favorite place of relaxation” while in trance so that the patient feels comfortable throughout the session. Five of the studies in this review included “favourite place of relaxation” in the script.[18,20,31,33,34] Three studies did not mention the techniques used for hypnosis.[24,29,36] Dissociation was another technique which was seen in a number of the studies.[19,22,31,33] Three studies used a glove anesthesia technique or “protective hand” to create a pain-free zone, which enables the operator to either to do a dental procedure without local anesthetic or increase the patient’s pain threshold.[21,31,33] A combination of techniques were used in most of the studies. Only one study used customized scripts based on patient’s interest and this was done in children aged between 7 and 12 years.[25]

Pain scores in the form of visual analog scales (VAS)[18,21,22,23,25,30,31,33,36] and McGill pain questionnaires[22,23] are useful self-reporting tools, whereas pain is quantitatively measured using electric pulp tester,[32] vitality scanner[31,33] and by the amount of analgesics required[22,30] during and after treatment. A numerical rating pain scale is a verbal scale using numbers to indicate intensity of pain between 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain). It can be done either face to face or via telephone or video call interview.[37] The face, legs, activity, crying, and consolability (FLACC) is based on observations by an operator and has values between 0 (relaxed) and 10 (severe pain).[38]

Anxiety was assessed in nine of the studies and the most popular tools were Speilberger State-Trait anxiety inventory (26.3%),[18,19,21,24] and dental anxiety score (15.8%).[19,24,27] Other tools used included modified Geer Fear Score,[19] revised Iowa dental control index,[24] and modified Yale preoperative anxiety scale.[25]

Clinical research on the use of hypnosis in dentistry is mainly focused on pain and anxiety. However, Trakyali et al.[29] show us that hypnosis can also be used to increase motivation in wearing orthodontic appliance and Satzl et al.[26] showed that it could be used to control salivary flow during dental treatment. All the studies which assessed pain and anxiety showed favorable effects of hypnosis. However, Ghoneim et al.[18] reported vomiting as a side effect among patients undergoing surgical removal of third molar under local anesthesia and hypnosis. The authors were unable to explain why an increase in postoperative vomiting was noted. This effect was not reported in any of the other studies which are included in this paper. Hypnosis is also shown to effective in managing tooth hypersensitivity.[30]

Although hypnosis is known to help with gag reflex cases, available literatures are limited to case reports. More research needs to be conducted in this area as hypnosis may have the potential of being a useful, inexpensive, and safe tool for carrying out dental treatment in patients with severe gag reflex. Similarly, the use of hypnosis for increasing motivation for maintenance of good oral hygiene should be investigated as this would be a beneficial tool for prevention of oral diseases.

This paper highlights the various hypnosis techniques which were used in the clinical studies. It is evident that there remain many scripts and methods which are yet to be studied with regard to its effectiveness in reducing anxiety and pain in dental treatment. The suitability of specific scripts for different age groups also deserves attention and more clinical studies.

The limitations encountered in this review are the inability to review papers which were not in the English language. Although the authors are proficient in Malay and Hindi, no relevant papers were found in these languages.

CONCLUSION

Hypnosis has the potential to be a useful tool in the management of children and adults. The current trend in research related to hypnosis leans toward the use of pre-recorded hypnotic scripts for the management of anxious patients. The use of hypnosis also has the potential to reduce postoperative pain in dental treatment involving surgery. More clinical research should be conducted to study the effectiveness of various techniques and scripts used for patients.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT AND SPONSORSHIP

Nil.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Not applicable.

ETHICAL POLICY AND INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD STATEMENT

Not applicable.

PATIENT DECLARATION OF CONSENT

Not applicable.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Not applicable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Not applicable.

REFERENCES

- 1.Seligman LD, Hovey JD, Chacon K, Ollendick TH. Dental anxiety: An understudied problem in youth. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;55:25–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armfield JM, Heaton LJ. Management of fear and anxiety in the dental clinic: A review. Aust Dent J. 2013;58:390–407; quiz 531. doi: 10.1111/adj.12118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White AM, Giblin L, Boyd LD. The prevalence of dental anxiety in dental practice settings. J Dent Hyg. 2017;91:30–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armfield JM, Stewart JF, Spencer AJ. The vicious cycle of dental fear: Exploring the interplay between oral health, service utilization and dental fear. BMC Oral Health. 2007;7:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Wijk AJ, Makkes PC. Highly anxious dental patients report more pain during dental injections. Br Dent J. 2008;205:142–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.AAPD. [Last accessed on 2020 May 20]. Behaviour Guidance for the Pediatric Dental Patient. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry 2015. Available from: https://www.aapd.org/globalassets/media/policies_guidelines/bp_behavguide.pdf .

- 7.Allison N. Hypnosis in modern dentistry: Challenging misconceptions. Facul Dent J. 2015;6:172–5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heap M, Aravind KK. Hartland’s Medical and Dental Hypnosis. 4th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2002. pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrick JM. Cultivating a chaiside manner: Dental hypnosis patient management psychology, the origins of behavioral dentistry in America, 1890–1910. J Behav Sci. 2013;49:235–58. doi: 10.1002/jhbs.21605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barber J, Donaldson D, Ramras S, Allen GD. The relationship between nitrous oxide conscious sedation and the hypnotic state. J Am Dent Assoc. 1979;99:624–6. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1979.0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gokli MA, Wood AJ, Mourino AP, Farrington FH, Bes AM. Hypnosis as an adjunct to the administration of local anaesthetic in pediatric patients. ASDC J Dent Child. 1994;61:272–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wood C, Bijoy A. Hypnosis and pain in children. J Pain Sympt. 2008;35:437–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peretz B, Bercovich R, Blumer S. Using elements of hypnosis prior to or during pediatric dental treatment. Pediatr Dent. 2013;35:33–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santos SA, Gleiser R, Ardenghi TM. Hypnosis in the control of pain and anxiety in paediatric dentistry: A literature review. GGO, Rev Gauch Odontol. 2019;67:e20190033. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bryant RA, Moulds ML, Nixon RDV, Mastrodomenico J, Felmingham K, Hopwood S. Hypnotherapy and cognitive behaviour therapy of acute stress disorder: A 3 year follow up. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:1331–5. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Namankany A, de Souza M, Ashley P. Evidence-based dentistry: Analysis of dental anxiety scales for children. Br Dent J. 2012;212:219–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghoneim MM, Block RI, Sarasin DS, Davis CS, Marchman N. Tape recorded hypnosis instructions as adjuvant in the care of patients scheduled for third molar surgery. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:64–8. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200001000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore R, Broadsgaard I, Abrahamsen R. A 3-year comparison of dental anxiety treatment outcomes: Hypnosis, group therapy and individual desensitization vs no specialist treatment. Eur J Oral Sci. 2002;110:287–95. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2002.21234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eitner S, Sokol B, Wichmann M, Bauer J, Engels D. Clinical use of a novel audio pillow with recorded hypnotherapy instructions and music for anxiolysis during dental implant surgery: A prospective study. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2011;59:180–97. doi: 10.1080/00207144.2011.546196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdeshahi SK, Hashemipour MA, Mesgarzadeh V, Payam AS, Monfared AH. Effect of hypnosis on induction of local anaesthesia, pain perception, control of haemorrhage and anxiety during extraction of third molars: A case–control study. J Cran Maxillofac Surg. 2013;41:310–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abrahamsen R, Baad-Hansen L, Svensson P. Hypnosis in the management of persistent idiopathic orofacial pain–clinical and psychosocial findings. Pain. 2008;136:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abrahamsen R, Zachariae R, Svensson P. Effect of hypnosis on oral function and psychological factors in temporomandibular disorders patients. J Oral Rehabil. 2009;36:556–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2009.01974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wannemueller A, Joehren P, Haug S, Hatting M, Elsesser K, Sartory G. A practice-based comparison of brief cognitive behavioural treatment, two kinds of hypnosis and general anaesthesia in dental phobia. Psychother Psychosom. 2011;80:159–65. doi: 10.1159/000320977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huet A, Lucas-Polomeni MM, Robert JC, Sixou JL, Wodey E. Hypnosis and dental anesthesia in children: A prospective controlled study. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2011;59:424–40. doi: 10.1080/00207144.2011.594740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Satzl M, Schmierer A, Zeman F, Schmalz G, Loew T. Significant variation in salivation by short-term suggestive intervention: A randomized controlled cross-over clinical study. Head Face Med. 2014;10:49. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-10-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glaesmer H, Geupel H, Haak R. A controlled trial on the effect of hypnosis on dental anxiety in tooth removal patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:1112–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oberoi J, Panda A, Garg I. Effect of hypnosis during administration of local anesthesia in six- to 16-year-old children. Pediatr Dent. 2016;38:112–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trakyali G, Sayinsu K, Müezzinoğlu AE, Arun T. Conscious hypnosis as a method for patient motivation in cervical headgear wear: A pilot study. Eur J Orthod. 2008;30:147–52. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjm120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eitner S, Bittner C, Wichmann M, Nickenig HJ, Sokol B. Comparison of conventional therapies for dentin hypersensitivity versus medical hypnosis. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2010;58:457–75. doi: 10.1080/00207144.2010.499350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolf TG, Wolf D, Below D, d’Hoedt B, Willershausen B, Daubländer M. Effectiveness of self-hypnosis on the relief of experimental dental pain: A randomized trial. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2016;64:187–99. doi: 10.1080/00207144.2016.1131587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Facco E, Casiglia E, Masiero S, Tikhonoff V, Giacomello M, Zanette G. Effects of hypnotic focused analgesia on dental pain threshold. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2011;59:454–68. doi: 10.1080/00207144.2011.594749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolf TG, Wolf D, Callaway A, Below D, d’Hoedt B, Willershausen B, et al. Hypnosis and local anesthesia for dental pain relief—alternative or adjunct therapy? A randomized, clinical-experimental crossover study. Int J Clin Exp Hypnos. 2016;64:391–403. doi: 10.1080/00207144.2016.1209033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramírez-Carrasco A, Butrón-Téllez Girón C, Sanchez-Armass O, Pierdant-Pérez M. Effectiveness of hypnosis in combination with conventional techniques of behavior management in anxiety/pain reduction during dental anesthetic infiltration. Pain Res Manage. 2017;2017:1–5. doi: 10.1155/2017/1434015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park ES, Yim HW, Lee KS. Progressive muscle relaxation therapy to relieve dental anxiety: A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Oral Sci. 2019;127:45–51. doi: 10.1111/eos.12585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mackey EF. Effects of hypnosis as an adjunct to intravenous sedation for third molar extraction: A randomized, blind, controlled study. Int J Clin Exp Hypnos. 2009;58:21–38. doi: 10.1080/00207140903310782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Breivik H, Borchgrevink PC, Allen SM, Rosseland LA, Romundstad L, Hals EK, et al. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:17–24. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crellin DJ, Harrison D, Santamaria N, Babl FE. Systematic review of the face, legs, activity, cry and consolability scale for assessing pain in infants and children: Is it reliable, valid, and feasible for use? Pain. 2015;156:2132–51. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.