Abstract

Background

To investigate the indications for high-flow nasal cannula oxygen (HFNC) therapy in patients with hypoxemia during ventilator weaning and to explore the predictors of reintubation when treatment fails.

Methods

Adult patients with hypoxemia weaning from mechanical ventilation were identified from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV) database. The patients were assigned to the treatment group or control group according to whether they were receiving HFNC or non-invasive ventilation (NIV) after extubation. The 28-day mortality and 28-day reintubation rates were compared between the two groups after Propensity score matching (PSM). The predictor for reintubation was formulated according to the risk factors with the XGBoost algorithm. The areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) was calculated for reintubation prediction according to values at 4 h after extubation, which was compared with the ratio of SpO2/FiO2 to respiratory rate (ROX index).

Results

A total of 524,520 medical records were screened, and 801 patients with moderate or severe hypoxemia when undergoing mechanical ventilation weaning were included (100 < PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300 mmHg), including 358 patients who received HFNC therapy after extubation in the treatment group. There were 315 patients with severe hypoxemia (100 < PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 200 mmHg) before extubation, and 190 patients remained in the treatment group with median oxygenation index 166[157,180] mmHg after PSM. There were no significant differences in the 28-day reintubation rate or 28-day mortality between the two groups with moderate or severe hypoxemia (all P > 0.05). Then HR/SpO2 was formulated as a predictor for 48-h reintubation according to the important features predicting weaning failure. According to values at 4 h after extubation, the AUC of HR/SpO2 was 0.657, which was larger than that of ROX index (0.583). When the HR/SpO2 reached 1.2 at 4 h after extubation, the specificity for 48-h reintubation prediction was 93%.

Conclusions

The treatment effect of HFNC therapy is not inferior to that of NIV, even on patients with oxygenation index from 160 to 180 mmHg when weaning from ventilator. HR/SpO2 is more early and accurate in predicting HFNC failure than ROX index.

Keywords: High-flow nasal cannula, Hypoxemia, Ventilator weaning, MIMIC

Background

High-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) treatment can offer continuously higher gas flow with better heat and humidity than conventional oxygen [1]. It is also popular because of its easy application and good tolerability [2]. Several high-quality studies have shown that the treatment effect of HFNC on patients with hypoxemia or patients after surgery is not inferior to that of noninvasive ventilation (NIV) [3, 4]. However, both the indications for HFNC after early extubation in hypoxemic patients and the timing of reintubation when HFNC fails are unclear [5].

This retrospective study was designed based on the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV) database to investigate the indications for HFNC for patients with hypoxemia during ventilator weaning. A machine learning algorithm was used to explore the predictors of reintubation in these patients.

Methods

Patients

The patients were identified in the MIMIC-IV database from 2008 to 2019. The inclusion criteria were as follows: hypoxemia 4 h before extubation (100 < PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300 mmHg); over 18 years old; with or without hypercapnia; and received continuous or intermittent HFNC or NIV after extubation. The exclusion criteria were as follows: tracheotomy; accidental extubation; and received both HFNC and NIV after extubation.

Source of data and ethics approval

This retrospective study was conducted based on a large critical care database named Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV [6]. This database is an updated version of MIMIC-III with pre-existing institutional review board approval. A number of improvements have been made, including simplifying the structure, adding new data elements, and improving the usability of previous data elements. Currently, the MIMIC-IV contains comprehensive and high-quality data of patients admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center between 2008 and 2019 (inclusive). One author (QZ) obtained access to the database and was responsible for data extraction.

Study design

The treatment group received continuous or intermittent HFNC after extubation, and the control group received continuous or intermittent NIV after extubation.

The following data were recorded: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), comorbidities, simplified acute physiology scoring II (SAPS-II) score at ICU admission, duration of mechanical ventilation, reintubation rate, mortality, length of ICU stay, length of hospital stay and duration before reintubation.

Physiological parameters and arterial blood gas (ABG) from 4 h before weaning to 48 h after extubation were collected. Average values for each patient per four hours were assessed, and the median value and interquartile ranges (IQRs) in the two groups were plotted. The 28-day mortality of patients who received reintubation within 48 h after extubation was compared with that of patients who received reintubation 48 h after extubation.

Statistical analysis

Variables with normal distributions are presented as the means (SD) and were compared with independent samples t tests. Nonnormally distributed variables are expressed as medians and IQRs, which were compared with the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables are described as percentages and were compared by using a chi-square test. A Kaplan–Meier curve was drawn to evaluate the time from extubation to reintubation, and a log-rank test was used to compare the differences in times between the two groups.

Above risk factors for reintubation were included for propensity score matching (PSM): age, gender, BMI, SAPS-II, comorbidities, heart rate, respiratory rate, mean blood pressure, pH, PaO2, PaCO2, PaO2/FiO2, SpO2 and ventilation duration before extubation. Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations was used to impute missing values, followed by the development of a multivariate logistic regression model to estimate the patient’s propensity scores for HFNC treatment [7]. One-to-one nearest neighbour matching with a caliper width of 0.1 was applied in the present study [8]. Statistical testing was performed to evaluate the effectiveness of PSM. The duration before reintubation, 28-day mortality, and 48-h and 28-day reintubation rates were compared based on matched data. Additionally, subgroup analyses were separately performed on patients with moderate and severe hypoxemia. PSM was applied to each subgroup, and outcomes were compared based on the matched data.

The risk factors for reintubation were analysed by a machine learning algorithm. The extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) model [9], an advanced ensemble learning algorithm, was developed to predict 48-hour reintubation risk based on the baseline variables. Feature importance was assessed by using the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) values [10]. Features were sorted according to the mean value of absolute SHAP values. Then, predictors were developed manually based on the baseline values of most important features. The areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUCs) of the predictors to predict 48-hour reintubation were calculated and compared with the rapid shallow breathing index (RSBI) and the ratio of SpO2/FiO2 to respiratory rate (ROX index).

All statistical analyses were performed with R (version 3.6.1), and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Propensity score adjusted and matched outcomes

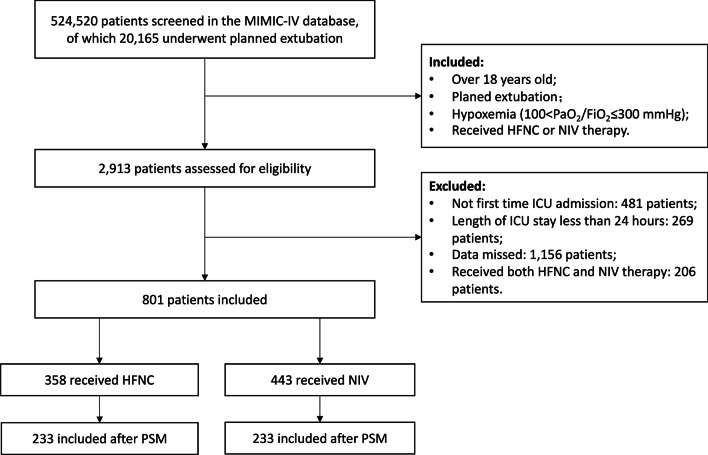

A total of 524520 medical records were screened, including 20165 patients with planned extubation. Finally, 801 patients with moderate and severe hypoxemia when mechanical ventilation weaning was included (100<PaO2/FiO2≤300 mmHg), and 358 patients received HFNC therapy after extubation in the treatment group. There were 233 patients remained in the treatment group with median oxygenation index 209[164,253] mmHg after PSM (Fig. 1). There were no significant differences in age, sex, BMI, SPAS-II score, comorbidities, duration of mechanical ventilation or physiological parameters before weaning between the 2 groups (all P>0.05).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the study

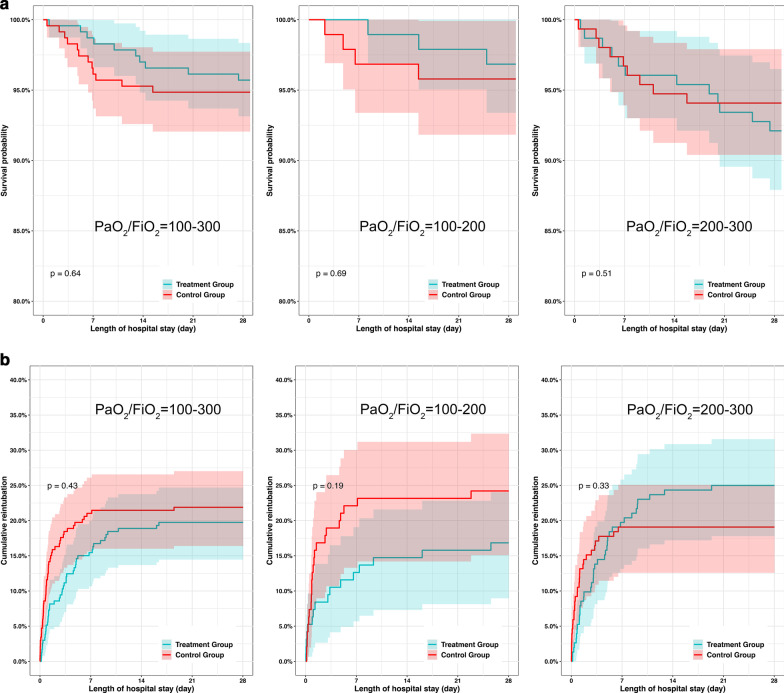

There were no significant differences in the 28-day reintubation rate (4.29% vs. 5.15%, P=0.827) or 28-day mortality (4.29% vs. 5.15%, P=0.827) between the two groups. The 48-hour reintubation rate in the treatment group was lower than that in the control group (8.58% vs. 15.88%, P=0.024).

There were 315 patients with severe hypoxemia (100<PaO2/FiO2≤200 mmHg) before extubation, and 190 patients remained in the treatment group with median oxygenation index 166[157,180] mmHg after PSM. There were no significant differences in the 48-hour reintubation rate, 28-day reintubation rate or 28-day mortality between the 2 groups (all P>0.05).

There were 486 patients with moderate hypoxemia (200<PaO2/FiO2≤300 mmHg) before extubation, and 304 patients remained in the treatment group with median oxygenation index 238[214,267] mmHg after PSM. There were no significant differences in the 48-hour reintubation rate, 28-day reintubation rate or 28-day mortality between the 2 groups (all P>0.05).

Both the length of stay in the ICU and in the hospital in the treatment group were longer than those in the control group (6.36 vs. 4.72 days, P<0.001 and 12.62 vs. 10.93 days, P=0.001). The duration before reintubation in the treatment group was longer than that in the control group (73.28 vs. 21.52 hours, P=0.001) (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

Table 1.

The baseline data and prognosis of patients with hypoxemia of different severities in the two groups after PSM

| 100 < PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300 n = 801 | 100 < PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 200 n = 315 | 200 < PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300 n = 486 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After PSM n = 466 | Treatment group n = 233 | Control group n = 233 | P value | After PSM n = 190 | Treatment group n = 95 | Control group n = 95 | P value | After PSM l n = 304 | Treatment group n = 152 | Control group n = 152 | P | |

| Age, median [Q1, Q3] | 69.38[61.00, 77.59] | 68.74[59.90, 77.81] | 69.80[61.48, 76.32] | 0.850 | 70.06[60.32, 78.09] | 69.91[60.55, 77.58] | 70.80[59.47, 78.50] | 0.638 | 68.09[59.57, 75.49] | 66.79[58.59, 75.85] | 68.71[60.21, 75.22] | 0.391 |

| Male, n (%) | 322(69.10) | 158(67.81) | 164(70.39) | 0.616 | 126(66.32) | 62(65.26) | 64(67.37) | 0.878 | 195(64.14) | 92(60.53) | 103(67.76) | 0.232 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 31.93(6.56) | 32.04(6.60) | 31.81(6.53) | 0.708 | 33.85(6.47) | 33.38(6.34) | 34.34(6.61) | 0.322 | 31.51(7.33) | 31.09(6.93) | 31.94(7.72) | 0.330 |

| Baseline disease | ||||||||||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 316(67.81) | 157(67.38) | 159(68.24) | 0.921 | 123(64.74) | 59(62.11) | 64(67.37) | 0.544 | 188(61.84) | 92(60.53) | 96(63.16) | 0.723 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 88(18.88) | 47(20.17) | 41(17.60) | 0.554 | 30(15.79) | 15(15.79) | 15(15.79) | 1.000 | 57(18.75) | 32(21.05) | 25(16.45) | 0.378 |

| COPD, n (%) | 52(11.16) | 29(12.45) | 23(9.87) | 0.462 | 17(8.95) | 12(12.63) | 5(5.26) | 0.127 | 35(11.51) | 18(11.84) | 17(11.18) | 1.000 |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 133(28.54) | 62(26.61) | 71(30.47) | 0.412 | 51(26.84) | 20(21.05) | 31(32.63) | 0.102 | 79(25.99) | 39(25.66) | 40(26.32) | 1.000 |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 54(11.59) | 28(12.02) | 26(11.16) | 0.885 | 25(13.16) | 11(11.58) | 14(14.74) | 0.668 | 36(11.84) | 19(12.50) | 17(11.18) | 0.859 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 96(20.60) | 51(21.89) | 45(19.31) | 0.567 | 35(18.42) | 15(15.79) | 20(21.05) | 0.454 | 60(19.74) | 33(21.71) | 27(17.76) | 0.471 |

| Leukaemia, n (%) | 3(0.64) | 1(0.43) | 2(0.86) | 1.000 | 6(3.16) | 2(2.11) | 4(4.21) | 0.682 | 3(0.99) | 1(0.66) | 2(1.32) | 1.000 |

| Strokes, n (%) | 20(4.29) | 11(4.72) | 9(3.86) | 0.819 | 5(2.63) | 2(2.11) | 3(3.16) | 1.000 | 20(6.58) | 13(8.55) | 7(4.61) | 0.247 |

| Cancer, n (%) | 48(10.30) | 25(10.73) | 23(9.87) | 0.879 | 25(13.16) | 16(16.84) | 9(9.47) | 0.198 | 33(10.86) | 15(9.87) | 18(11.84) | 0.712 |

| Liver disease, n (%) | 32(6.87) | 14(6.01) | 18(7.73) | 0.583 | 12(6.32) | 9(9.47) | 3(3.16) | 0.136 | 32(10.53) | 20(13.16) | 12(7.89) | 0.191 |

| SAPS-II at admission, mean (SD) | 42.99(12.44) | 43.00(12.96) | 42.97(11.92) | 0.979 | 43.17(13.09) | 43.42(13.60) | 42.93(12.62) | 0.795 | 42.61(12.97) | 43.12(13.54) | 42.09(12.39) | 0.491 |

| Duration before extubation, median [Q1,Q3], hours | 20.77[6.89, 65.71] | 22.00[7.32, 73.27] | 19.50[6.12, 48.85] | 0.136 | 21.73[6.68, 57.68] | 24.00[6.73, 68.37] | 20.47[6.76, 47.30] | 0.304 | 19.78[6.91, 81.10] | 21.99[7.24, 108.54] | 18.08[6.35, 46.92] | 0.133 |

| Physiological variables before extubation 4 h | ||||||||||||

| Heart rate, mean (SD) | 83.15(13.84) | 83.74(13.97) | 82.55(13.72) | 0.354 | 82.93(13.39) | 82.72(12.30) | 83.14(14.47) | 0.832 | 83.94(13.47) | 84.72(14.41) | 83.17(12.47) | 0.316 |

| Respiratory rate, mean (SD) | 18.99(3.95) | 19.07(3.90) | 18.91(4.00) | 0.669 | 19.37(3.97) | 19.40(4.06) | 19.35(3.90) | 0.938 | 18.81(3.97) | 18.90(4.09) | 18.73(3.86) | 0.701 |

| Tidal volume, mean (SD) | 487.80(125.50) | 493.81(127.26) | 481.81(123.75) | 0.337 | 504.61(134.40) | 521.13(139.12) | 487.07(127.73) | 0.101 | 487.71(122.32) | 487.63(124.30) | 487.79(120.82) | 0.991 |

| MBP, mean (SD) | 77.51(11.00) | 77.80(11.62) | 77.22(10.35) | 0.570 | 77.91(10.51) | 78.35(10.40) | 77.46(10.65) | 0.562 | 78.46(12.22) | 78.83(13.21) | 78.08(11.16) | 0.591 |

| pH, mean (SD) | 7.40(0.05) | 7.40(0.05) | 7.39(0.05) | 0.366 | 7.40(0.06) | 7.40(0.06) | 7.40(0.05) | 0.358 | 7.39(0.05) | 7.39(0.05) | 7.39(0.05) | 0.812 |

| PaO2, median [Q1, Q3] | 100.00[84.00, 115.00] | 97.75[83.00, 114.00] | 101.50[86.00, 118.00] | 0.208 | 84.42[76.25, 95.00] | 84.50[78.75, 95.00] | 84.33[76.00, 95.25] | 0.924 | 109.00[98.88, 125.63] | 107.00[95.38, 122.56] | 110[100.50, 130.63] | 0.340 |

| PaCO2, mean (SD) | 41.01(6.96) | 40.75(6.57) | 41.26(7.34) | 0.433 | 40.70[6.56] | 40.61[6.12] | 40.79[7.01] | 0.852 | 41.08(6.65) | 40.78(6.98) | 41.37(6.32) | 0.441 |

| SpO2, median [Q1, Q3] | 97.50[95.83, 98.75] | 97.25[95.80, 98.75] | 97.50[96.00, 99.00] | 0.397 | 96.06[94.68, 97.79] | 95.75[94.50, 97.52] | 96.50[94.90, 98.20] | 0.152 | 98.00[96.67, 99.25] | 97.75[96.75, 99.16] | 98.25[96.50, 99.25] | 0.412 |

| PaO2/FiO2, median [Q1,Q3] | 211.79[171.42, 253.23] | 209.00[164.00, 253.62] | 213.00[179.33, 253.06] | 0.253 | 169.46[155.08, 182.83] | 166.67[157.44, 180.60] | 171.33[153.44, 187.56] | 0.283 | 242.00[217.50, 270.23] | 238.46[214.00, 267.34] | 248.04[222.00, 273.98] | 0.209 |

| Reintubation 48 h, n (%) | 57(12.23) | 20(8.58) | 37(15.88) | 0.024 | 24(12.63) | 8(8.42) | 16(16.84) | 0.126 | 37(12.17) | 15(9.87) | 22(14.47) | 0.293 |

| Reintubation 28 days, n (%) | 97(20.82) | 46(19.74) | 51(21.89) | 0.648 | 39(20.53) | 16(16.84) | 23(24.21) | 0.281 | 67(22.04) | 38(25.00) | 29(19.08) | 0.268 |

| Mortality 28 days, n (%) | 22(4.72) | 10(4.29) | 12(5.15) | 0.827 | 7(3.68) | 3(3.16) | 4(4.21) | 1.000 | 21(6.91) | 12(7.89) | 9(5.92) | 0.651 |

| Duration before reintubation, median [Q1, Q3], hours | 28.65[11.57, 90.78] | 73.28[21.63, 124.15] | 21.52[8.84, 56.85] | 0.001 | 25.03[9.04, 113.43] | 52.22[5.96, 163.10] | 21.72[10.88, 66.22] | 0.424 | 38.55[12.12, 111.62] | 73.66[27.39, 133.14] | 19.70[4.62, 40.63] | 0.001 |

| LOS in hospital, median [Q1, Q3] | 11.54[7.18, 17.75] | 12.62[7.65, 20.61] | 10.93[6.83, 15.82] | 0.001 | 11.87[7.65, 16.61] | 12.80[7.79, 19.23] | 11.28[7.48, 15.43] | 0.102 | 12.01[7.02, 19.90] | 14.59[8.68, 25.02] | 10.12[6.22, 16.72] | < 0.001 |

| LOS in ICU, median [Q1, Q3] | 5.55[3.09, 11.14] | 6.36[3.85, 13.59] | 4.72[2.27, 9.70] | < 0.001 | 5.39[3.10, 10.93] | 6.22[3.82, 12.69] | 4.80[2.30, 9.39] | 0.026 | 6.19[3.12, 13.14] | 7.43[4.19, 15.89] | 4.25[2.23, 9.47] | < 0.001 |

Fig. 2.

Survival curve and cumulative reintubation curve of patients with different severities of hypoxemia after PSM. a Survival curve of patients with different severities of hypoxemia after PSM. b Cumulative reintubation curve of patients with different severities of hypoxemia after PSM

The 28-day mortality of patients with reintubation 48 hours after extubation was not higher than that within 48 hours in either the treatment group or the control group (23.08% vs. 10.00%, P=0.206 and 19.23% vs. 12.73%, P=0.509) (Table 2).

Table 2.

The baseline data and prognosis of patients who received reintubation within 48 h of and 48 h after extubation in the two groups

| Treatment group n = 358 | Control group n = 443 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All reintubations n = 79 | Within 48 h n = 40 | 48 h after n = 39 | P value | All reintubations n = 81 | Within 48 h n = 55 | 48 h after n = 26 | P value | |

| Age, median[Q1, Q3] | 67.68[57.02, 78.00] | 64.47[49.57, 77.97] | 68.83[62.52, 77.59] | 0.202 | 71.82[62.27, 78.93] | 71.52[60.69, 78.69] | 73.40[64.81, 78.74] | 0.485 |

| Male, n (%) | 59(74.68) | 31(77.50) | 28(71.79) | 0.746 | 48(59.26) | 29(52.73) | 19(73.08) | 0.134 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 29.65(5.87) | 28.99(5.72) | 30.38(6.02) | 0.314 | 32.60(9.00) | 31.12(8.34) | 35.67(9.71) | 0.051 |

| Baseline disease | ||||||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 41(51.90) | 18(45.00) | 23(58.97) | 0.309 | 54(66.67) | 33(60.00) | 21(80.77) | 0.110 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 12(15.19) | 7(17.50) | 5(12.82) | 0.790 | 13(16.05) | 7(12.73) | 6(23.08) | 0.331 |

| COPD, n (%) | 5(6.33) | 3(7.50) | 2(5.13) | 1.000 | 9(11.11) | 5(9.09) | 4(15.38) | 0.458 |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 23(29.11) | 10(25.00) | 13(33.33) | 0.570 | 29(35.80) | 17(30.91) | 12(46.15) | 0.277 |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 6(7.59) | 4(10.00) | 2(5.13) | 0.675 | 14(17.28) | 9(16.36) | 5(19.23) | 0.760 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 17(21.52) | 5(12.50) | 12(30.77) | 0.089 | 21(25.93) | 10(18.18) | 11(42.31) | 0.041 |

| Leukaemia, n (%) | 1(1.27) | 0 | 1(2.56) | 0.494 | 2(2.47) | 1(1.82) | 1(3.85) | 0.542 |

| Strokes, n (%) | 8(10.13) | 1(2.50) | 7(17.95) | 0.029 | 6(7.41) | 4(7.27) | 2(7.69) | 1.000 |

| Cancer, n (%) | 10(12.66) | 6(15.00) | 4(10.26) | 0.737 | 16(19.75) | 9(16.36) | 7(26.92) | 0.415 |

| Liver disease, n (%) | 12(15.19) | 7(17.50) | 5(12.82) | 0.790 | 14(17.28) | 8(14.55) | 6(23.08) | 0.360 |

| SAPS-II at admission, mean (SD) | 44.32(13.08) | 43.30(10.86) | 45.36(15.09) | 0.490 | 47.20(13.72) | 46.73(13.48) | 48.19(14.45) | 0.665 |

| Duration before extubation, median [Q1,Q3], hours | 61.50[20.33, 125.27] | 53.92[15.14, 110.82] | 67.35[22.86, 138.07] | 0.364 | 38.90[20.25, 131.67] | 40.83[23.53, 128.29] | 28.46[17.63, 127.40] | 0.413 |

| Physiological variables before extubation 4 h | ||||||||

| Heart rate, mean (SD) | 87.28(15.55) | 89.67(16.07) | 84.84(14.80) | 0.168 | 86.00(16.39) | 87.03(14.03) | 83.81(20.67) | 0.476 |

| Respiratory rate, mean (SD) | 19.10(4.67) | 19.41(4.09) | 18.78(5.23) | 0.556 | 19.73(4.17) | 19.70(4.42) | 19.79(3.64) | 0.920 |

| Tidal volume, mean (SD) | 534.45(132.46) | 527.92(146.70) | 539.43(122.28) | 0.734 | 454.31(111.36) | 448.81(112.36) | 466.35(110.87) | 0.553 |

| MBP, mean (SD) | 79.62(12.93) | 81.10(13.91) | 78.10(11.82) | 0.304 | 77.45(10.11) | 77.61(10.55) | 77.13(9.31) | 0.836 |

| pH, mean (SD) | 7.41(0.07) | 7.39(0.07) | 7.42(0.06) | 0.068 | 7.39(0.05) | 7.39(0.06) | 7.38(0.05) | 0.831 |

| PaO2, median [Q1, Q3] | 91.00[82.00, 107.00] | 89.25[83.50, 104.62] | 95.50[81.17, 110.50] | 0.444 | 96.00[87.00, 108.00] | 95.00[85.75, 106.25] | 98.25[89.54, 115.00] | 0.347 |

| PaCO2, mean (SD) | 39.76(6.76) | 39.52(6.60) | 40.01(6.99) | 0.751 | 44.79(10.47) | 45.58(11.74) | 43.10(7.01) | 0.240 |

| SpO2, median [Q1, Q3] | 97.00[95.54, 98.69] | 96.50[95.00, 98.29] | 97.25[96.38, 98.88] | 0.088 | 97.25[95.50, 98.60] | 97.80[95.75, 98.78] | 96.50[95.56, 97.93] | 0.172 |

| PaO2/FiO2, median [Q1,Q3] | 209.00[175.50, 248.62] | 208.00[170.00, 229.86] | 217.50[189.75, 254.30] | 0.233 | 220.00[187.50, 252.52] | 213.00[186.50, 254.32] | 221.88[192.12, 249.65] | 0.712 |

| Mortality 28 days, n (%) | 13(16.46) | 4(10.00) | 9(23.08) | 0.206 | 12(14.81) | 7(12.73) | 5(19.23) | 0.509 |

Features and predictors of HFNC failure

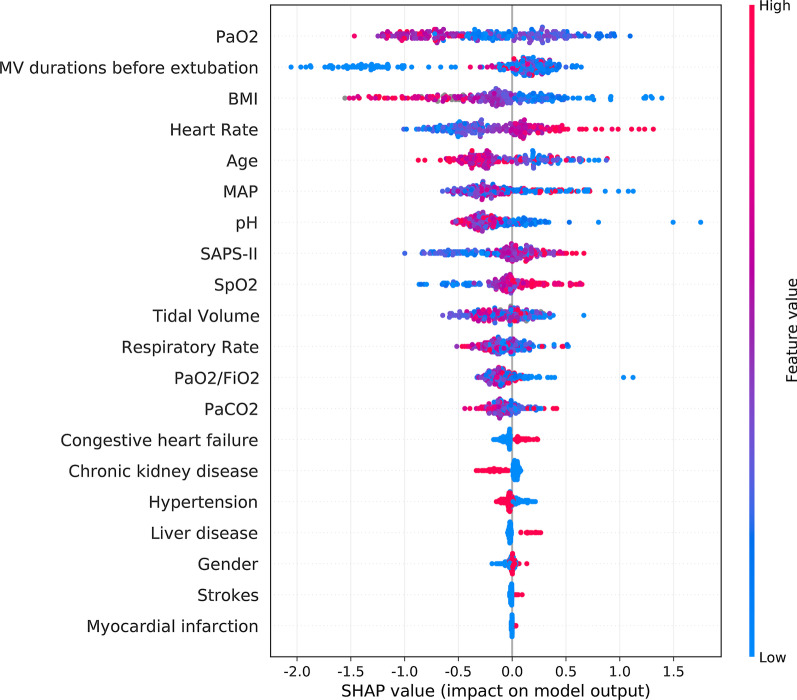

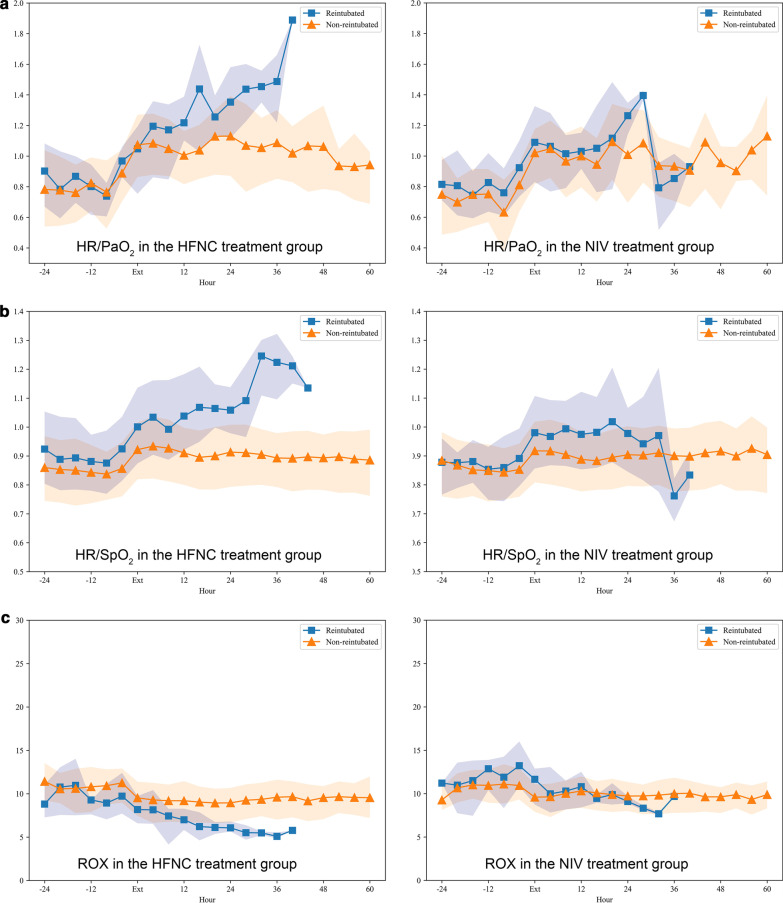

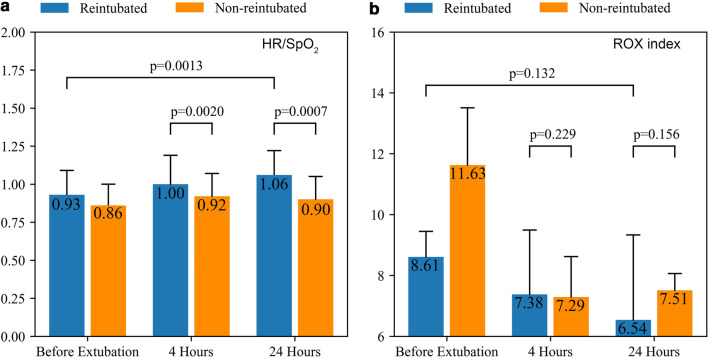

The important features predicting weaning failure were PaO2, duration before extubation, heart rate, BMI, age, mean blood pressure, pH, SAPS-II, SpO2, tidal volume and respiratory rate (Fig. 3). Thus HR/PaO2 and HR/SpO2 were calculated manually based on the above important features. There was a significant difference of HR/SpO2 at 4 hours after extubation between patients weaning failed and successfully (1.00 vs. 0.92, P< 0.05), and no significant difference of ROX index at the same time (7.38 vs. 7.29, P>0.05). HR/SpO2 increased more than 10% compared to baseline data in patients with failed HFNC treatment at 24 hours after extubation (1.06 vs.0.93 , P< 0.05) while there was no significant change in the ROX index at the same time (6.54 vs. 8.61, P>0.05) (Table 3 and Fig. 4-5).

Fig. 3.

Important features of the machine learning XGBoost model in reintubation prediction

Table 3.

Changes in physiological parameters in patients with successful or failed weaning in the HFNC treatment group

| Failed n = 40 | Successful n = 318 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 h before extubation | 4 h after extubation | 8–12 h later | 20–24 h later | 36–40 h | 4 h before reintubation | 4 h before extubation | 4 h after extubation | 8–12 h later | 20–24 h later | 36–40 h | |

| Heart rate, mean (SD) | †89.67(16.07) | †94.62 (17.57) | †94.26 (18.59) | *†99.78 (14.64) | *†115.05 (9.92) | *99.18 (18.88) | 83.01(13.42) | *87.65 (14.48) | *87.93 (14.79) | *85.33 (14.28) | 85.01 (14.56) |

| Respiratory rate, mean (SD) | 19.41(4.09) | *†22.83 (4.29) | *22.64 (5.31) | *†24.40 (5.69) | 26.88 (8.09) | *24.47 (4.81) | 19.31(4.29) | *21.21 (4.75) | *21.29 (4.80) | *21.00 (4.58) | *21.02 (4.91) |

| Tidal volume, mean (SD) | 527.92(146.70) | – | – | – | – | – | 504.81(126.12) | – | 515.93 (132.49) | – | – |

| MBP, mean (SD) | 81.10(13.91) | 80.82 (15.61) | 83.41 (14.24) | 81.46 (14.29) | 81.91 (12.14) | *83.97 (14.58) | 78.34(11.79) | 79.95 (12.62) | 79.32 (14.04) | 79.18 (12.32) | 78.93 (11.57) |

| pH, mean (SD) | 7.39(0.07) | 7.37 (0.12) | 7.40 (0.08) | 7.36 (0.10) | 7.42 (0.08) | 7.38 (0.10) | 7.40(0.06) | 7.41 (0.07) | 7.42 (0.06) | *7.43 (0.06) | *7.45 (0.06) |

| PaO2, median [Q1, Q3] | 89.25[83.50, 104.62] | 91.50 [74.38,119.00] | *75.50 [64.50,95.00] | *81.00 [72.50,82.75] | 75.50 [68.75,82.25] | *76.75 [66.75,98.50] | 92.50[80.00, 110.00] | *83.00 [71.00,99.00] | *81.00 [71.00,97.00] | *78.00 [69.50,87.00] | *79.00 [68.75,104.50] |

| PaCO2, mean (SD) | 39.52(6.60) | 41.78 (7.62) | 39.61 (6.56) | 39.00 (9.94) | 47.50 (4.95) | 40.09 (9.12) | 40.00(6.83) | 39.65 (7.36) | *37.82 (6.83) | *37.72 (8.68) | 37.76 (8.35) |

| SpO2, median [Q1, Q3] | 96.50[95.00, 98.29] | *95.12 [93.94,95.88] | *95.38 [93.44,96.43] | *94.25 [93.66,95.62] | 95.00 [94.50,96.25] | *93.27 [91.69,95.29] | 97.00[95.00, 98.50] | *95.00 [93.75,96.59] | *95.00 [93.50,96.50] | *95.00 [93.75,96.50] | *95.25 [93.55,96.94] |

| PaO2/FiO2, median [Q1,Q3] | 208.00[170.00, 229.88] | *151.61 [133.75,171.50] | *129.00 [100.83,130.00] | *95.30 [85.99,111.55] | *†75.50 [68.75,82.25] | *98.84 [79.38,147.03] | 201.29[163.20, 238.35] | *137.75 [102.12,175.50] | *126.08 [100.08,171.39] | *126.00 [90.31,171.00] | *133.53 [110.00,171.08] |

| ROX Index | †8.61 [7.57,9.45] | 7.38 [5.27,9.49] | 6.95 [5.25,8.75] | 6.54 [4.82,9.33] | 5.32 [3.93, 8.12] | *3.54 (0.43) | 11.63 [9.22,13.51] | *7.29 [6.33,8.62] | *7.97 [7.08,9.01] | 7.51 [6.97,8.06] | 12.24 [9.55,14.94] |

| RSBI | 40.35[30.71, 54.80] | – | – | – | – | *49.88 [40.31,55.09] | 39.22[29.87, 50.51] | – | – | – | – |

| HR/PaO2 | †0.97(0.22) | 1.05 (0.37) | 1.17 (0.34) | *1.25 (0.27) | 1.64 (0.49) | *1.25 (0.45) | 0.89(0.27) | *1.07 (0.33) | *1.05 (0.32) | *1.13 (0.58) | *1.09 (0.35) |

| HR/SpO2 | †0.93(0.16) | †1.00 (0.19) | 0.99 (0.19) | *†1.06 (0.16) | *†1.22 (0.10) | *1.06 (0.20) | 0.86(0.14) | *0.92 (0.15) | *0.93 (0.16) | *0.90 (0.15) | *0.89 (0.15) |

†P < 0.05 versus value of patients with successful weaning, *P < 0.05 vs value at baseline

Fig. 4.

Changes in HR/PaO2, HR/SpO2 and the ROX index in patients who received reintubation within 48 h in the two groups. a HR/PaO2; b HR/SpO2; and c the ROX index

Fig. 5.

Values of HR/SpO2 and the ROX index at 4 and 24 h after extubation in two groups. a HR/SpO2; and b the ROX index

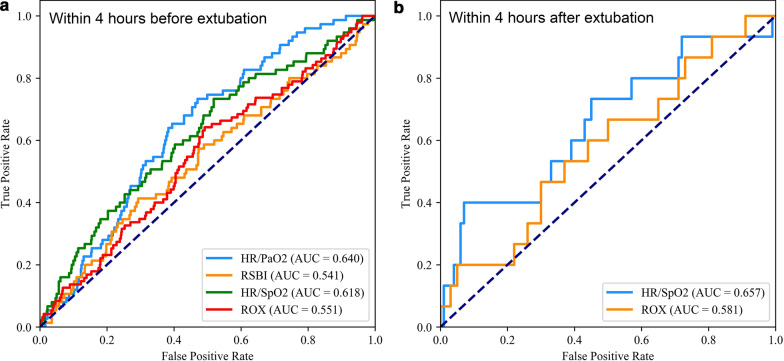

According to values at 4 hours before extubation, the AUCs of HR/PaO2 and HR/SpO2 were 0.640 and 0.618 for predicting 48-hour reintubation, respectively, which were larger than that of RSBI (AUC=0.541) and ROX index (AUC=0.551). According to values at 4 hours after extubation, the AUC of HR/SpO2 were 0.657 for predicting 48-hour reintubation, which were larger than that of ROX index (AUC=0.583). The specificity reached 93% when the cut-off point of HR/SpO2 was 1.20 at 4 hours after extubation (Table 4 and Fig. 6).

Table 4.

Predicting power of HFNC failure by HR/PaO2, HR/SpO2, RSBI and the ROX index at 4 h before and after extubation

| AUC (95% CI) | P | Cutoff value | Youden Index | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 h before extubation | ||||||||

| HR/PaO2 | 0.640 [0.584, 0.694] | P < 0.01 | 0.829 | 0.263 | 0.733 | 0.530 | 0.159 | 0.943 |

| HR/SpO2 | 0.618 [0.551, 0.683] | P < 0.01 | 0.830 | 0.215 | 0.733 | 0.481 | 0.146 | 0.937 |

| RSBI | 0.541 [0.467, 0.607] | P < 0.01 | 48.4 | 0.120 | 0.413 | 0.707 | 0.146 | 0.909 |

| ROX index | 0.551 [0.488, 0.610] | P < 0.01 | 0.107 | 0.168 | 0.640 | 0.528 | 0.141 | 0.924 |

| 4 h after extubation | ||||||||

| HR/SpO2 | 0.657 [0.571, 0.724] | P < 0.01 | 1.203 | 0.330 | 0.400 | 0.930 | 0.462 | 0.911 |

| ROX index | 0.583 [0.519, 0.629] | P < 0.01 | 6.376 | 0.020 | 0.800 | 0.220 | 0.133 | 0.880 |

Fig. 6.

The ROC curves of HR/PaO2, HR/SpO2, the ROX index, and RSBI for 48-h reintubation prediction in the HFNC treatment group. a The ROC curves within 4 h before extubation; b the ROC curves within 4 h after extubation

Discussion

In our study, more than 500,000 medical records from 2008 to 2019 were selected from MIMIC-IV, and 801 patients with moderate to severe hypoxemia during mechanical ventilation weaning who received HFNC or NIV therapy were finally included. There were no significant differences in primary outcomes, including the 28-day reintubation rate and 28-day mortality, between the HFNC treatment group and the control group after PSM. Consistent results were confirmed in patients with moderate and severe hypoxemia. HFNCs can provide constant airflow and oxygen concentration with a small amount of positive end-expiratory pressure [11–13]. Therefore, the therapeutic effect of HFNC is better than that of conventional oxygen, including nasal catheters and facemasks [5, 14, 15]. Most research designs in recent years have been noninferior studies of HFNC and NIV, but the specific indication of hypoxemia is not clear. HFNC is noninferior to NIV for preventing postextubation respiratory failure in patients at high risk of reintubation or resolving acute respiratory failure in patients who receive cardiothoracic surgery. As the better tolerance with HFNC and a higher airway pressure delivered by NIV, combined treatment may be a better clinical option. Thille reported that the combined treatment could reduce the reintubation rate within 7 days compared to the use of HFNC alone [16]. In these studies, the mean oxygenation index of those patients with moderate hypoxemia was nearly 200 mmHg [3, 4]. Our study found that the effect of HFNC therapy was not inferior to that of NIV, even for severely hypoxemic patients with median oxygenation index of 170 mmHg.

The reintubation rate for ICU patients weaning from mechanical ventilation is approximately 10% [17], but it can reach 20% in patients at high risk when HFNC fails, and the timing of reintubation is mostly concentrated within 48 h after weaning [3, 4], which is consistent with our results. Therefore, patients who received reintubation within 48 h were regarded as having treatment failure in the HFNC treatment group, and we tried to predict reintubation within 48 h after extubation [18].

The longer length of ICU stay followed a longer duration before reintubation with the use of HFNC compared with NIV, which is in contrast to previous findings [5]. However, the mortality of patients who received reintubation within 48 h was not higher than that of patients who received reintubation 48 h after extubation in the HFNC group. In contrast to our findings, a previous study found that delayed intubation in patients with hypoxemia who received HFNC therapy might increase mortality [19]. The different results may be caused by different experimental designs and cohort sample sizes.

Although RSBI is routinely used as a clinical predictor of extubation failure, the threshold value for RSBI less than 105 had poor predictability for weaning success when measured at baseline during the spontaneous breathing trial, and it can be significantly affected by the level of ventilator support [20–22]. Moreover, the tidal volume is not routinely monitored after weaning. In patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, the respiratory rate was a predictor of intubation under standard oxygen but not under high-flow nasal cannula oxygen or noninvasive ventilation [23]. Studies have shown that effective therapy for HFNC can decrease the work of breathing and reduce the respiratory rate of patients [24, 25]. Therefore, we think that the RSBI composed of tidal volume and respiratory rate is not a good predictor for reintubation with HFNC failure. ROX index is defined as the ratio of SpO2/FiO2 to respiratory rate [26], which needs further verification as a predictor of HFNC failure. At present, a simple and clear predictor for whether patients need early reintubation after weaning is still needed, and the timing of switching to invasive ventilator therapy is also not clear when HFNC fails [27, 28].

Respiratory work and oxygen consumption could be reduced with effective HFNC therapy. According to stroke volume × heart rate = cardiac output, heart rate decreased with cardiac output decreasing. And respiratory rate also decreased with less respiratory work. As feature importance was obtained by machine learning algorithm, we could infer that heart rate may be a more important and sensitive risk factor than respiratory rate. SpO2/FiO2 is a more accurate parameter to reflect oxygenation status than SpO2 according to basic physiology. But a predictor with two variables are obviously more simple and practical than the predictor with three variables. So we collected the two most important variables heart and SpO2 to form the predictor HR/SpO2 instead of the ratio of HR to SpO2/FiO2. Therefore, we propose to use HR/PaO2 or HR/SpO2 as predictors of reintubation.

As serial measurements of the RSBI and ROX index could more accurately predict successful weaning from mechanical ventilators [20, 29], we also observed the dynamic changes in these two indexes during extubation. The AUCs of HR/SpO2 according to values at 4 h before and after extubation to predict reintubation were larger than those of ROX index. The HR/SpO2 of patients with failed HFNC treatment was higher than that of patients with successful HFNC treatment within 4 h after weaning, but there was no significant difference of ROX index at the same time. Both HR/SpO2 and ROX index changed more than 10% compared to baseline data in patients with failed HFNC treatment at 24 h. The specificity of predicting HFNC treatment failure reached 93% when the threshold value of HR/SpO2 was 1.20 at 4 h after extubation, which was larger than that of ROX index. Therefore, HR/SpO2 may be a more sensitive and accurate predictor than ROX index for reintubation when HFNC treatment fails.

Limitations

Our study is a retrospective study based on the MIMIC-IV database. The daily time of HFNC and NIV treatment in the treatment group and the control group was not extracted, which would have an impact on the treatment effect. Although most of high risk factors for reintubation were included and matched in the propensity score, there were few high risk factors not included because data missed in this retrospective study. Although the sample size was not small and propensity score matching ensured low heterogeneity in the included patients, the results of this study need to be verified by multicentre, large-sample prospective studies.

Conclusions

The treatment effect of HFNC therapy is not inferior to that of NIV, even on patients with oxygenation index from 160 to 180 mmHg when weaning from ventilator. HR/SpO2 is more early and accurate in predicting HFNC failure than ROX index within 48 h after extubation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for the MIMIC project.

Abbreviations

- HFNC

High-flow nasal cannula

- NIV

Noninvasive ventilation

- MIMIC-IV

The medical information mart for intensive care IV

- ICUs

Intensive care units

- BMI

Body mass index

- SAPS-II

The simplified acute physiology scoring II

- ABG

Arterial blood gas

- IQR

Interquartile range

- PSM

Propensity score matching

- XGBoost

The extreme gradient boosting

- SHAP

The Shapley additive explanations

- AUC

The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- RSBI

The rapid shallow breathing index

- ROX index

The ratio of SpO2/FiO2 to respiratory rate

Authors' contributions

TL and QZ contributed equally to this work. TL and BD conceptualized the research aims, planned the analyses, and guided the literature review. QZ extracted the data from the MIMIC-IV database. TL, QZ and BD participated in data analysis and interpretation. TL wrote the first draft of the paper and the other authors provided comments and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the MIMIC-IV repository, https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/0.4/.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The establishment of this database was approved by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Cambridge, MA) and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (Boston, MA), and consent was obtained for the original data collection. Therefore, the ethical approval statement and the need for informed consent were waived for this manuscript.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Taotao Liu and Qinyu Zhao have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

References

- 1.Nishimura M. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy in adults. J Intensive Care. 2015;3:15. doi: 10.1186/s40560-015-0084-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lenglet H, Sztrymf B, Leroy C, Brun P, Dreyfuss D, Ricard JD. Humidified high flow nasal oxygen during respiratory failure in the emergency department: feasibility and efficacy. Respir Care. 2012;57(11):1873–78. 10.4187/respcare.01575. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Hernandez G, Vaquero, Colinas L, et al. Effect of postextubation high-flow nasal cannula vs noninvasive ventilation on reintubation and postextubation respiratory failure in high-risk patients a randomized clinical trial supplemental content. JAMA J Am Med Assoc 2016;316. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Stéphan F, Barrucand B, Petit P, et al. High-flow nasal oxygen vs noninvasive positive airway pressure in hypoxemic patients after cardiothoracic surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313:2331–2339. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.5213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Granton D, Chaudhuri D, Wang D, et al. High-flow nasal cannula compared with conventional oxygen therapy or noninvasive ventilation immediately postextubation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:e1129–e1136. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson A, Bulgarelli L, Pollard T, Horng S, Celi LA, Mark R. MIMIC-IV (version 0.4). PhysioNet 2020.

- 7.Zhao Q-Y, Luo J-C, Su Y, Zhang Y-J, Tu G-W, Luo Z. Propensity score matching with R: conventional methods and new features. Ann Transl Med 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Leite W. Practical propensity score methods using R2016.

- 9.Chen T, Guestrin C. XGBoost: a scalable tree boosting system. In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining. San Francisco, California, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2016:785–94.

- 10.Lundberg SM, Erion G, Chen H, et al. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat Mach Intell. 2020;2:56–67. doi: 10.1038/s42256-019-0138-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Groves N, Tobin A. High flow nasal oxygen generates positive airway pressure in adult volunteers. Aust Crit Care. 2007;20:126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parke R, McGuinness S, Eccleston M. Nasal high-flow therapy delivers low level positive airway pressure. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:886–890. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chikata Y, Onodera M, Oto J, Nishimura M. FIO2 in an adult model simulating high-flow nasal cannula therapy. Respir Care. 2017;62:193–198. doi: 10.4187/respcare.04963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernández G, Vaquero C, González P, et al. Effect of postextubation high-flow nasal cannula vs conventional oxygen therapy on reintubation in low-risk patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:1354–1361. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y, Huang D, Ni Y, Liang Z. High-flow nasal cannula vs conventional oxygen therapy for postcardiothoracic surgery. Respir Care 2020:respcare.07595. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Thille AW, Muller G, Gacouin A, et al. Effect of postextubation high-flow nasal oxygen with noninvasive ventilation vs high-flow nasal oxygen alone on reintubation among patients at high risk of extubation failure: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322:1465–1475. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.14901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miltiades AN, Gershengorn HB, Hua M, Kramer AA, Li G, Wunsch H. Cumulative probability and time to reintubation in US ICUs. Crit Care Med 2017;45:835–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Beduneau G, Pham T, Schortgen F, et al. Epidemiology of weaning outcome according to a new definition. The WIND Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;195. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Kang BJ, Koh Y, Lim C-M, et al. Failure of high-flow nasal cannula therapy may delay intubation and increase mortality. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:623–632. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3693-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krieger BP, Isber J, Breitenbucher A, Throop G, Ershowsky P. Serial measurements of the rapid-shallow-breathing index as a predictor of weaning outcome in elderly medical patients. Chest. 1997;112:1029–1034. doi: 10.1378/chest.112.4.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel K, Ganatra K, Bates J, Young M. Variation in the rapid shallow breathing index associated with common measurement techniques and conditions. Respir Care. 2009;54:1462–1466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frutos-Vivar F, Ferguson ND, Esteban A, et al. Risk factors for extubation failure in patients following a successful spontaneous breathing trial. Chest. 2006;130:1664–1671. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.6.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frat JP, Ragot S, Coudroy R, et al. Predictors of intubation in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure treated with a noninvasive oxygenation strategy. Crit Care Med. 2017;46:1. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corley A, Caruana LR, Barnett AG, Tronstad O, Fraser JF. Oxygen delivery through high-flow nasal cannulae increase end-expiratory lung volume and reduce respiratory rate in post-cardiac surgical patients. Br J Anaesth. 2011;107:998–1004. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagstaff TAJ, Soni N. Performance of six types of oxygen delivery devices at varying respiratory rates*. Anaesthesia. 2007;62:492–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roca O, Caralt B, Messika J, et al. An index combining respiratory rate and oxygenation to predict outcome of nasal high flow therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018;199. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.McConville JF, Kress JP. Weaning patients from the ventilator. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2233–2239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1203367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saugel B, Rakette P, Hapfelmeier A, et al. Prediction of extubation failure in medical intensive care unit patients. J Crit Care. 2012;27:571–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spinelli E, Roca O, Mauri T. Dynamic assessment of the ROX index during nasal high flow for early identification of non-responders. J Crit Care. 2020;58:130–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2019.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the MIMIC-IV repository, https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/0.4/.