Abstract

Members of racial and ethnic minority groups make up nearly 50% of U.S. patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) and face a disproportionate burden of socio-economic challenges (i.e. low income, job insecurity, low educational attainment, housing instability, and communication challenges) compared to non-Hispanic whites. Patients with ESKD who face social challenges often have poor patient-centered and clinical outcomes. These challenges may have a negative impact on quality of care performance measures for dialysis facilities caring for primarily minority and low-income patients. One path towards improving outcomes for this group is to develop culturally tailored interventions that provide individualized support potentially improving patient-centered, clinical, and health system outcomes by addressing social challenges. One such approach is using community-based, culturally and linguistically concordant patient navigators, who can serve as a bridge between the patient and the healthcare system. Evidence points to the effectiveness of patient navigators in provision of cancer care and, to a lesser extent, in caring for people with chronic kidney disease and those who have undergone a kidney transplant. However, little is known about the effectiveness of patient navigators in the care of patients with kidney failure receiving dialysis, who experience a number of remediable social challenges.

Keywords: end-stage kidney disease (ESKD); dialysis; patient-centered care; racial/ethnic minorities; disparities in care; transplant access; culturally concordant care; peer support; transplant waitlisting; health literacy; cultural sensitivity; linguistic barriers, systemic bias; underserved communities; dialysis facility

Introduction

Members of certain racial and ethnic groups (e.g. African Americans, Hispanics, Native Americans and Pacific Islanders) have a disproportionately high incidence rate of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) and make up nearly 50% of the population with this condition.1 They also disproportionately face social challenges that lead to poor patient-centered (i.e. valuable to the patient such as quality of life) and clinical outcomes compared to non-Hispanic white patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) in the United States (US).1–17 Previous studies have documented disparities and highlighted the importance of improving health outcomes for underserved patients with ESKD; however, approaches for improving clinical outcomes, adequately addressing social challenges, and reducing disparities for these patients have been understudied.18

Community-based, culturally and linguistically tailored approaches may help address the social challenges of underserved minority patients with ESKD and may enhance the likelihood of better health outcomes in this high-risk patient population. Patient navigator (PN) programs that focus on helping patients reduce barriers to care have improved health outcomes and reduced health disparities among disadvantaged racial/ethnic minority patients with other chronic health conditions.19,20 Although there is no standard definition for a PN program, PNs are typically lay non-medical individuals who are culturally concordant (i.e. shared ideas, values, customs, and/or experiences such as with ESKD) and/or linguistically concordant with the target community and familiar with community resources.21 Studies of PN programs to increase listing for kidney transplantation and slow the progression of CKD provide insights that can guide navigator interventions. This perspective provides a history of PN programs in kidney disease and explores their potential to improve patient-centered and clinical outcomes among members of racial and ethnic groups with kidney failure receiving dialysis.

What is Patient Navigation?

In a 1989 report, the American Cancer Society (ACS) highlighted poverty as a key factor that contributed to worse cancer outcomes for racial and ethnic minority patients.22 To address this concern, in 1990 the ACS supported the first PN program in Harlem, NY.23 In this program, a community-based strategy was used to select lay people as PNs from the community and establish culturally concordant methods of communication. The objectives of this intervention were to increase cancer education and screening as well as improve timeliness of follow-up for patients with abnormal screening tests.24 The pilot program was divided into three phases. First, the PN received on-the-job training by visiting hospitalized patients with cancer to understand complex barriers to survivorship care and reported these barriers during project staff meetings to discuss possible solutions. Second, the PN met with clinic patients who had abnormal screening tests in an effort to increase follow-up rates. Third, the PN program was expanded from one African American navigator to include a Spanish-speaking Hispanic PN. This PN intervention highlighted previously unrecognized and critical barriers to care for such patient populations, who frequently reported both medical (e.g. inability to obtain medications, high cost of medical care) and non-medical (e.g. barriers relating to transportation, childcare, and release from work) issues. Over time, the PN program in Harlem grew and improved breast cancer screening rates, early diagnosis, and 5-year survival.23

Since then, PN programs have grown as a way of improving outcomes for patients with other conditions. A 2018 systematic review of PN programs for various chronic diseases (e.g. cancer, diabetes, HIV infection, cardiovascular disease, CKD, and dementia) found that common characteristics included the use of lay individuals trained on the job, telephone-based communication, and location of the PN in primary care practices or the community. The review found that PN programs reported a statistically significant improvement in primary outcomes, but most of these were “process” outcomes (i.e. completion of disease screening and adherence to follow-up). Many of the PN programs had a short period of follow-up with uncertain power to demonstrate an impact on clinical and patient-centered outcomes.19 While programs varied widely in terms of intervention activities and in the educational background of the PN, one common element was understanding of social challenges faced by the target community, which helped position the PNs to work with patients to overcome barriers to care.

The Rationale for Patient Navigation in Maintenance Dialysis Patients

Patient navigation is well-suited for maintenance dialysis patients for several important reasons. First, kidney failure disproportionately affects racial and ethnic minorities who also face burdens related to social challenges that altogether increase their risk of progression from CKD to kidney failure and worse ESKD outcomes.3,4,8,25–30 Some of the social challenges are remediable and may be addressed by a PN intervention. Low health literacy, as one example, is more common among low socio-economic status patients with ESKD and is associated with non-adherence to care, which is in turn, a risk factor for increased mortality.9,31,32 For patients that experience low health literacy, a PN could help establish an environment that promotes health literacy by providing individualized education.

Second, persons receiving maintenance dialysis are treated by a healthcare workforce that does not reflect the diversity of the U.S. population.33–35 Diversity in the healthcare workforce improves access to healthcare for underserved patients and improves racial and ethnic minority choice and satisfaction.36–45 While efforts underway to increase diversity in the overall healthcare workforce progress slowly, PN programs in which the PN matches the diversity of the patient population, can serve as a bridge to the healthcare providers at the dialysis facility and can be implemented more immediately. Moreover, the diagnosis of kidney failure is complex, requiring a change in schedule and diet as well as clinical appointments for vascular access and kidney transplantation and having a culturally concordant PN provide emotional and social support can help patients overcome barriers. Third, dialysis facilities that predominantly serve minority and low-income patients tend to have worse performance on quality domains and may be more likely to receive a payment reduction.3,46–49 To promote high-quality patient care in the outpatient dialysis setting, the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) implemented the ESKD Quality Incentive Program, a value-based purchasing model in which payments are linked to performance on quality care measures. In dialysis facilities that serve minority and low-income patients, PNs that are culturally and linguistically concordant may be particularly important to improve both quality and reimbursement. In summary, PNs can enhance the quality of care racial/ethnic minorities receive by providing support with social challenges and by serving as a bridge to the dialysis healthcare providers.

Current State of Science of Patient Navigation in Kidney Disease

To our knowledge, there are six published studies focused on use of PNs with patients with CKD (Table 1). The primary outcomes described include change in eGFR50, kidney transplantation process step completion51,52, increase in potential living kidney donor53, increase wait-listing for kidney transplantation54, and a feasibility study to improve health-related quality of life of dialysis patients.55 The professional experience of the PN varied among the studies. Two employed lay PNs with college degrees50,55 and two employed PNs that were professional social workers.53,54 Culture and language concordance varied across the studies. The PNs in one study received cultural sensitivity training on the target African American community53 and the PNs were culture and/or language concordant in two studies.54,55 Three studies employed PNs who were ‘peers’ (i.e. had prior personal experience with ESKD). In two studies, the PNs were previous transplant recipients51,52,56 and in one study, the PN had previously cared for a family member with ESKD.55 The experiences of peer PNs was further explored by the two studies that employed prior kidney transplant recipients. They found that because of the shared experience with CKD, the PNs felt personal satisfaction in sharing in the success of dialysis patients.56 Trust between the PN and patient was specifically described as critical to study success in three of the PN studies.50,53,55 Altogether, we learn from the CKD PN programs that there is great variation in terms of PN experience and training. Future PN programs could compare the PN characteristics to identify those characteristics that are most meaningful.

Table 1.

Patient Navigation Studies

| Study | Design | Primary Outcome | Participants and Setting | PN Hiring, Training, and Salary | PN interaction with Patient & staff | Results and comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jolly67 Navaneethan50 |

2×2 factorial RCT: 1) usual care; 2) enhanced personal health record only; 3) PN and enhanced personal health record; and 4) PN | ΔeGFR over 2 y | Adult English-speaking pts at CKD clinic. White, Black, Multiracial, and Asian/Pacific Islanders represented. Non-English speakers excluded. | PNs were lay individuals with good interpersonal skills and proficient with computers. Training was structured and included on-the-job shadowing of clinicians, EHR training, and CKD-specific training. Salary was commensurate with experience. No mention of cultural concordance. | PN met with pts every 2–4 wk face-to-face or over the phone during clinic visits. Additional interactions based on pt needs. | No change in eGFR after 2 y follow-up. Lesson learned: Importance of building a trusting relationship with pt to maintain good communication. |

| Sullivan51 | Cluster RCT at dialysis facilities and Tx centers: 1) usual care; and 2) PN. | Tx process steps completed over 2 y | Adult English-speaking Tx candidates on dialysis. Whites, Blacks, and Others represented. Non-English speakers excluded. | Three lay PNs who were kidney Tx recipients. Training included education on kidney Tx process, human subjects protection, medical records abstraction, and motivational interviewing. Salary was the same as a study coordinator. No mention of cultural concordance. | PN met with pts monthly face-to-face during dialysis treatment. Additional interactions based on pt needs. PN shared personal experiences, reviewed the medical record, provided support in completion of Tx steps. PN communicated with Tx staff. | PN group completed twice as many steps in the Tx process compared to controls (3.5 vs 1.6 steps). Limitation: Due to small sample size and short duration, did not assess whether or not participants received a Tx. |

| Marlow53 | Observational study comparing a nephrology practice with a PN program to one without | Increase in potential living kidney donors over 5 y | Adult English-speaking ESKD pts from an academic Tx center. Potential donors were family or friends. Blacks, Whites, and Others represented. Non-English speakers excluded. | Two PNs who were professional social workers. Training included on-the-job shadowing and organ donation-specific education from interdisciplinary clinicians (nurse coordinator, surgeons, and nephrologists). Also received cultural sensitivity training on the African American community. | PN provided education and support to Tx candidates and their potential living donors. Additional interactions based on pt needs. | Tx candidates at nephrology practice with a PN were more likely to have an initial inquiry (OR, 1.21 [1.01–1.44]) and a preliminary screening (OR, 1.27 [1.05–1.54]) of a potential living donor, but no significant differences in evaluated potential living donor (OR, 0.94 [0.61–1.45]). Lesson learned: May be beneficial to measure pt satisfaction with treatment and support. Building trust and providing tailored education were critical components. |

| Basu M54 | RCT comparing usual care and PN | Increase wait-listing for kidney Tx | Adult ESKD Tx candidates; English or non-English speaking. Whites, Blacks, Others, Hispanics, and Non-Hispanics represented. | One PN with a Masters degree in social work who is Black. No description of the PN training. | PN called pts before their first Tx evaluation to conduct an initial assessment. Additional face-to-face and phone meetings until waitlisting decision. PN attended a multidisciplinary selection conference, |

After 500 d, intervention participants were 3.3 times more likely to be successfully waitlisted compared to control participants (75% vs 25%; HR, 3.3 [1.20–9.12]). Lesson learned: Short duration and underpowered. One PN may have been overburdened by pt social challenges. Finding appropriate number of pts per navigator is critical. |

| Sullivan C52 | Cluster RCT comparing: 1) dialysis facilities with a PN; and 2) dialysis facilities without a PN | No. of Tx process Steps completed over 2 y or at study end | Adult Englishspeaking dialysis pts at 40 dialysis facilities and 4 Tx centers | Four PNs who were Tx recipients. Training included a 3-d session on the kidney Tx process, medical records review, motivational interviewing, and human subjects protection. No mention of cultural concordance. | PN met with pts face-to-face monthly during a dialysis treatment. PN interactions with pts and staff similar to prior RCT by same PI.51 Additional interactions based on pt needs. | No difference between the intervention and control group in first visit, wait-listing, deceased donor Tx, and living donor Tx. Limitation: Short duration and underpowered. Many pts were ineligible or declined to participate. PNs supervised from afar, limiting ability to identify and address challenges. |

| Cervantes L55 | Single-arm feasibility trial | Feasibility and acceptability over 2 y | Adult Spanish or English-speaking Hispanic ESKD patients. Hispanics targeted. | One Spanish-speaking Latina PN. The PN had personal experience as a caregiver for ESKD family member. Training included motivational interviewing and navigator fundamentals, on-the-job shadowing of clinicians, EHR, and ESKD-specific training. | PN met with pts every 2–4 wk face-to-face during a dialysis treatment or at home and was available over the phone. Additional interactions based on pt needs. | The intervention was feasible and acceptable. Of 49 eligible pts, 40 (82%) agreed to participate. None withdrew from intervention. Lesson learned: A trusting relationship between PN and pt during consent for study facilitated recruitment and subsequent study visits. |

Values in brackets are 95% confidence intervals.

EHR, electronic health record; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; HR, hazard ratio; OR, odds ratio; PI, principal investigator; Tx, transplantation

Core Qualities for ESKD Patient Navigation Programs

Personal Characteristics of the Patient Navigator

Since the first PN program, PNs have generally mirrored the demographics and language of the target communities they serve and, by extension, may be more familiar with the target community’s values, struggles, and the availability of resources.23,57 Language congruence could enhance communication, particularly for Latinos, who make up nearly 17% of the US community with ESKD and are most often primarily Spanish speakers.1,2 A linguistically concordant PN could also improve ESKD-related education and promote personalized relationships between the patient and his/her healthcare providers because the PN can provide in-person language interpretation during dialysis treatment visits.

Having personal experience with ESKD (either as a primary caregiver or personally as a kidney transplant recipient) has also been shown to be valuable in ESKD navigators.51,52,55 In a study that assessed the quality of life needs and preferences of Latino patients with ESKD, patients described that during times of distress, an important source of support was connecting with other patients who have experience with ESKD and many hoped such peer support relationships could be formalized when they start dialysis.58 A PN with personal experience with ESKD could provide that formalized peer support.

PNs who are both culturally and linguistically concordant with patients may not be available in all settings. In addition to skills and experience, the PN model, from development to the growing evidence base, has traditionally prioritized cultural concordance above other demographic characteristics (i.e. gender, age, or socioeconomic concordance). The model was developed to address health disparities based on race and ethnicity. While racial/ethnic disparities are due in part to socioeconomic disadvantage, systemic racism and bias remains a barrier to health equity.59–61 Therefore, we advocate for a PN model that emphasizes cultural concordance and/or cultural humility (i.e. a humble and self-reflective attitude toward individuals of other cultures that encourages one to address their own cultural biases and learn about others cultures) as well as linguistic concordance. One cancer study assessed the importance of PN race and language concordance on time to diagnostic resolution of cervical and breast cancer screening abnormalities. It found that Black, Hispanic, and Asian women paired with a race-concordant navigator had timelier resolution of screening abnormalities compared to women within the same racial group with race-discordant navigators. They also found that patient-navigator language concordance (especially among Spanish-speakers) was associated with timelier resolution of cervical cancer screening abnormalities.62 Additionally, a systematic review of PN programs for racial/ethnic minorities with cancer and limited English proficiency highlighted PN race and language concordance as important aspects of successful programs.63

Hiring and Training

The PN may be a lay individual with good communication skills. Among published CKD PN studies, there was variation in education (college degree versus Masters degree in social work) and training (basic navigator fundamentals, on-the-job training, and online educational modules). Some health care systems and dialysis centers have proposed nurse navigators as opposed to the lay navigator model. To some extent, the scope of practice and clinical needs may dictate the best skill set required for the navigator role. We advocate for the lay navigator model for addressing social challenges in underserved populations for several important reasons. An important aspect of the lay PN is their ability to develop a trusting relationship facilitated by the shared experience in the community and at similar education levels. A power dynamic that could influence this relationship is avoided by having a language-concordant lay PN who may share a similar cultural background as the patients they work with. Additionally, based on our prior research involving underserved Hispanic patients, patients expressed the desire for a peer mentor who could provide them with support around advance care planning conversations as well as emotional support in the continuum of their illness.55,58 Based on our group’s experience with a PN intervention at an ESKD facility, important components of training are: 1) skills to identify community resources and tailor health education to patient; 2) behavioral training (e.g. motivational interviewing and patient activation) through online PN programs; 3) ESKD-specific education provided on-the-job by shadowing various interdisciplinary providers at the dialysis facility (e.g. social worker, nurse, registered dietician, patient care technician) and by reading ESKD educational topics in websites such as those from the National Kidney Disease Education Program and the National Kidney Foundation; and 4) electronic health record or data computer system training so that patient interactions can be documented.

Healthcare Delivery Setting

Placing PNs at the outpatient dialysis facility and encouraging the PN to meet with patients during a dialysis treatment session allows for meaningful use of the patient’s otherwise unoccupied time. Ideally, patient interactions will be face-to-face and at the patient’s preferred site (e.g. dialysis chairside, home for patients on peritoneal dialysis, or during a clinic visit). Placing PNs at the dialysis facility also integrates the PN into the dialysis healthcare team and promotes communication between the healthcare team and the patients because the PN can provide language interpretation. Additionally, the PN could participate in monthly interdisciplinary team meetings and provide insight into the patient’s home situation.

Patient Navigation Outcomes

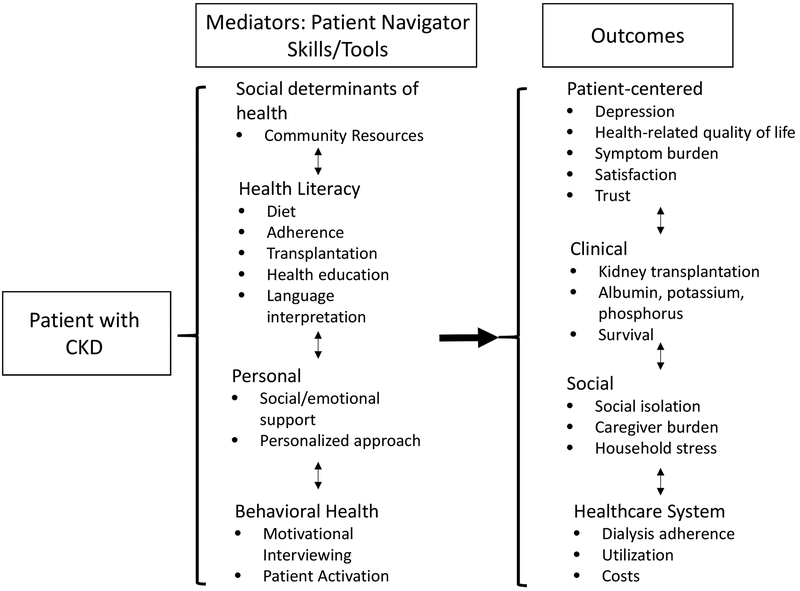

In the dialysis facility setting, an empathetic and well-trained lay PN who is culturally and linguistically concordant could provide support with social challenges and improve patient-centered, clinical, and healthcare system outcomes (Figure 1). From the first patient interaction, the goal of the PN could be to establish a trusting relationship with the patient. The PN could then develop an action plan based on an initial assessment of patient’s barriers to care and healthcare goals. The support and frequency of meetings provided by the PN could be individualized and tailored to meet the patient’s needs as well as the healthcare provider’s concerns. For example, if healthcare providers report that a patient’s phosphorus or potassium levels are high, the PN could provide insight on the culprit social challenges (e.g. food instability, cost of medications, or other competing priorities) leading to non-adherence. The PN can brainstorm with the healthcare team and provide social support as well as provide support with health literacy and language interpretation during meetings with the healthcare team.

Figure 1.

Patient Navigation Outcomes

If on the other hand, the patient reported feeling depressed, the PN could help the social worker complete a screening depression measure and then use motivational interviewing and patient activation skills to connect the patient to mental health care. The PN could be integrated into the dialysis facility healthcare team and during interdisciplinary team meetings, report on the social challenges and barriers to care and explore solutions.

Outlook for Future Patient Navigator Programs

Aligning Outcomes with CMS measures

In addition to the interpersonal and behavioral impact of PN programs, the activities of PNs could align more directly with the patient-centered and clinical outcome measures in the CMS ESRD Quality Incentive Program to improve reimbursement for kidney care in dialysis facilities serving minority and low socio-economic status (SES) patients. For example, the PN can use motivational interviewing and provide support with social challenges (e.g. transportation, cost of medications, education) to improve patient adherence to dialysis, diet, and medication, thereby improving clinical measures. Future research should investigate the effectiveness of PNs in improving these outcomes.

Impact on Dialysis Facility Staffing

CMS requires that each dialysis facility have a Masters-level social worker focused on addressing social challenges and improving patient mental health well-being. Social workers, however, may be constrained in providing mental health support at minority and low SES-serving dialysis facilities if they must focus on addressing social concerns. Having a PN focus on patient’s social challenges, may allow the social worker to more effectively use their education and training to provide mental health support. Collaboration between a PN who provides support in addressing social challenges and a social worker that provides support with mental health well-being could have a synergistic effect on patient centered (i.e. health-related quality of life, symptoms, depression, satisfaction with care) and clinical (i.e. dialysis adherence, hospitalization) outcomes. Additionally, a PN may be a stable person that provides in-person language interpretation for healthcare staff during dialysis session face-to-face PN visits. This would reduce the need for separate in-person language interpreters and promote individualized and personalized relationships between healthcare staff and dialysis patients.

Demonstrating efficacy and cost-effectiveness

PN programs for patients with ESKD and social challenges have results that are promising yet large, multicenter studies with longer duration of patient follow-up are needed to test the effectiveness of a PN program to improve clinical outcomes, quality of care, and reduce health inequities.64 Only four of previously published PN CKD programs were RCTs and three of the four were underpowered. Additionally, a cost-effectiveness analysis of the PN program from both a societal and healthcare sector perspective would inform CMS of potential cost savings at each dialysis facility.

Potential Challenges Facing Patient Navigator Programs

Taking a PN program to scale in a dialysis organization may pose various challenges. If patients in the organization are linguistically and culturally diverse, hiring decisions will need to balance the goal of attaining cultural and linguistic concordance with other considerations such as experience with ESKD, prior experience, and communication skills. In two studies of PN perspectives on the ideal patient-PN relationship qualities, PNs reported that demonstrating respect and sensitivity for a patient’s culture was the most important.65,66 Thus, hiring culturally and linguistically concordant PNs is ideal but when not feasible, communication and culture-specific training is highly recommended. A second challenge is in standardizing training for a large number of PNs if brought to scale; however, the development of standardized training courses and manuals would provide a systematic approach. Finally, the costs of adding a PN to a dialysis facility may be a barrier, but should be weighed against improvements in adherence that have the potential to improve both patient outcomes and reimbursements for the dialysis facility.

Conclusion

Patient navigator programs have the potential to improve patient-centered and clinical outcomes in a way that is culturally and linguistically concordant among underserved and minority patients with ESKD. Given the growing number of minority patients with ESKD, it is imperative that rigorously-evaluated interventions that reduce health disparities among patients with ESKD nationwide be conducted and more broadly implemented.

Acknowledgments

Support: Dr. Cervantes is funded by the National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) K23DK117018 Award. Dr. Cervantes also received support from the University of Colorado, School of Medicine. The funders had no role in defining the content of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests. Peer Review: Received _______ in response to an invitation from the journal. Evaluated by 2 external peer reviewers, with direct editorial input from an Associate Editor and a Deputy Editor. Accepted in revised form June 15, 2019.

Reference

- 1.Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC, et al. US Renal Data System 2018 Annual Data Report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;73(3)(suppl 1):A7–A8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fischer MJ, Go AS, Lora CM, et al. CKD in Hispanics: Baseline characteristics from the CRIC (Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort) and Hispanic-CRIC Studies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(2):214–227. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodriguez RA, Sen S, Mehta K, Moody-Ayers S, Bacchetti P, O’Hare AM. Geography matters: relationships among urban residential segregation, dialysis facilities, and patient outcomes. Annals of internal medicine. 2007;146(7):493–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crews DC, Charles RF, Evans MK, Zonderman AB, Powe NR. Poverty, race, and CKD in a racially and socioeconomically diverse urban population. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(6):992–1000. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ricardo AC, Roy JA, Tao K, et al. Influence of Nephrologist Care on Management and Outcomes in Adults with Chronic Kidney Disease. Journal of general internal medicine. 2016;31(1):22–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arce CM, Mitani AA, Goldstein BA, Winkelmayer WC. Hispanic ethnicity and vascular access use in patients initiating hemodialysis in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(2):289–296. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08370811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kausz AT, Obrador GT, Arora P, Ruthazer R, Levey AS, Pereira BJ. Late initiation of dialysis among women and ethnic minorities in the United States. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2000;11(12):2351–2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jurkovitz CT, Li S, Norris KC, et al. Association between lack of health insurance and risk of death and ESRD: results from the Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP). Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(4 Suppl 2):S24–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green JA, Mor MK, Shields AM, et al. Associations of health literacy with dialysis adherence and health resource utilization in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62(1):73–80. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.1012.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavanaugh KL, Wingard RL, Hakim RM, et al. Low health literacy associates with increased mortality in ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(11):1979–1985. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009111163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraser SD, Roderick PJ, Casey M, Taal MW, Yuen HM, Nutbeam D. Prevalence and associations of limited health literacy in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(1):129–137. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lora CM, Gordon EJ, Sharp LK, Fischer MJ, Gerber BS, Lash JP. Progression of CKD in Hispanics: potential roles of health literacy, acculturation, and social support. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(2):282–290. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehrotra R, Soohoo M, Rivara MB, et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Use of and Outcomes with Home Dialysis in the United States. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2016;27(7):2123–2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norris K, Nissenson AR. Race, gender, and socioeconomic disparities in CKD in the United States. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2008;19(7):1261–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norris KC, Williams SF, Rhee CM, et al. Hemodialysis Disparities in African Americans: The Deeply Integrated Concept of Race in the Social Fabric of Our Society. Seminars in dialysis. 2017;30(3):213–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hood CM, Gennuso KP, Swain GR, Catlin BB. County Health Rankings: Relationships Between Determinant Factors and Health Outcomes. American journal of preventive medicine. 2016;50(2):129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradley EH, Elkins BR, Herrin J, Elbel B. Health and social services expenditures: associations with health outcomes. BMJ quality & safety. 2011;20(10):826–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tuttle KR, Tuot DS, Corbett CL, Setter SM, Powe NR. Type 2 translational research for CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(10):1829–1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McBrien KA, Ivers N, Barnieh L, et al. Patient navigators for people with chronic disease: A systematic review. PloS one. 2018;13(2):e0191980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roland KB, Milliken EL, Rohan EA, et al. Use of Community Health Workers and Patient Navigators to Improve Cancer Outcomes Among Patients Served by Federally Qualified Health Centers: A Systematic Literature Review. Health equity. 2017;1(1):61–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paskett ED, Harrop JP, Wells KJ. Patient navigation: an update on the state of the science. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2011;61(4):237–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Cancer Society. Cancer and the Poor: A Report to the Nation. Findings of Regional Hearings Conducted by teh American Cancer Society. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society;1989. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freeman HP. Patient navigation: a community centered approach to reducing cancer mortality. Journal of cancer education : the official journal of the American Association for Cancer Education. 2006;21(1 Suppl):S11–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freeman HP, Muth BJ, Kerner JF. Expanding access to cancer screening and clinical follow-up among the medically underserved. Cancer Pract. 1995;3(1):19–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crews DC, Gutierrez OM, Fedewa SA, et al. Low income, community poverty and risk of end stage renal disease. BMC Nephrol. 2014;15:192.(doi): 10.1186/1471-2369-1115-1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young BA, Katz R, Boulware LE, et al. Risk Factors for Rapid Kidney Function Decline Among African Americans: The Jackson Heart Study (JHS). Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68(2):229–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johns TS, Estrella MM, Crews DC, et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic status, race, and mortality in young adult dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(11):2649–2657. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013111207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Volkova N, McClellan W, Klein M, et al. Neighborhood poverty and racial differences in ESRD incidence. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2008;19(2):356–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tarver-Carr ME, Powe NR, Eberhardt MS, et al. Excess risk of chronic kidney disease among African-American versus white subjects in the United States: a population-based study of potential explanatory factors. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2002;13(9):2363–2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crews DC, Kuczmarski MF, Grubbs V, et al. Effect of food insecurity on chronic kidney disease in lower-income Americans. Am J Nephrol. 2014;39(1):27–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green JA, Mor MK, Shields AM, et al. Prevalence and demographic and clinical associations of health literacy in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(6):1354–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kimmel PL, Peterson RA, Weihs KL, et al. Psychosocial factors, behavioral compliance and survival in urban hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 1998;54(1):245–254. doi: 210.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.United State Census Bureau. QuickFacts. United States. Table. . 2018; https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045218. Accessed January 29, 2019.

- 34.United States Census Bureau: Hispanic Heritage Month. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/visualizations/2018/comm/hispanic-fff-2018.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2019.

- 35.Association of American Medical Colleges. Table A-8 Applicants to U.S. Medical Schools by Selected Combinations of Race/Ethnicity and Sex, 2015–16 through 2018–2019. https://www.aamc.org/download/321472/data/factstablea8.pdf. Accessed January 23, 2019, 2019.

- 36.Komaromy M, Grumbach K, Drake M, et al. The role of black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care for underserved populations. The New England journal of medicine. 1996;334(20):1305–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marrast LM, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, Bor DH, McCormick D. Minority physicians’ role in the care of underserved patients: diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing health disparities. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(2):289–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garcia JA, Paterniti DA, Romano PS, Kravitz RL. Patient preferences for physician characteristics in university-based primary care clinics. Ethnicity & disease. 2003;13(2):259–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saha S, Taggart SH, Komaromy M, Bindman AB. Do patients choose physicians of their own race? Health affairs (Project Hope). 2000;19(4):76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.LaVeist TA, Nickerson KJ, Bowie JV. Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among African American and white cardiac patients. Medical care research and review : MCRR. 2000;57 Suppl 1:146–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? Journal of health and social behavior. 2002;43(3):296–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, et al. Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. Jama. 1999;282(6):583–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dunlap JL, Jaramillo JD, Koppolu R, Wright R, Mendoza F, Bruzoni M. The effects of language concordant care on patient satisfaction and clinical understanding for Hispanic pediatric surgery patients. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2015;50(9):1586–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ngo-Metzger Q, Sorkin DH, Phillips RS, et al. Providing high-quality care for limited English proficient patients: the importance of language concordance and interpreter use. Journal of general internal medicine. 2007;22 Suppl 2:324–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eskes C, Salisbury H, Johannsson M, Chene Y. Patient satisfaction with language--concordant care. The journal of physician assistant education : the official journal of the Physician Assistant Education Association. 2013;24(3):14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hall YN, Xu P, Chertow GM, Himmelfarb J. Characteristics and performance of minority-serving dialysis facilities. Health services research. 2014;49(3):971–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Almachraki F, Tuffli M, Lee P, et al. Socioeconomic Status of Counties Where Dialysis Clinics Are Located Is an Important Factor in Comparing Dialysis Providers. Population health management. 2016;19(1):70–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saunders MR, Lee H, Chin MH. Early winners and losers in dialysis center pay for-performance. BMC health services research. 2017;17(1):816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saunders MR, Chin MH. Variation in dialysis quality measures by facility, neighborhood, and region. Medical care. 2013;51(5):413–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Navaneethan SD, Jolly SE, Schold JD, et al. Pragmatic Randomized, Controlled Trial of Patient Navigators and Enhanced Personal Health Records in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(9):1418–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sullivan C, Leon JB, Sayre SS, et al. Impact of navigators on completion of steps in the kidney transplant process: a randomized, controlled trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(10):1639–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sullivan CM, Barnswell KV, Greenway K, et al. Impact of Navigators on First Visit to a Transplant Center, Waitlisting, and Kidney Transplantation: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(10):1550–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marlow NM, Kazley AS, Chavin KD, Simpson KN, Balliet W, Baliga PK. A patient navigator and education program for increasing potential living donors: a comparative observational study. Clin Transplant. 2016;30(5):619–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Basu M, Petgrave-Nelson L, Smith KD, et al. Transplant Center Patient Navigator and Access to Transplantation among High-Risk Population: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(4):620–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cervantes L, Chonchol M, Hasnain-Wynia R, et al. Peer Navigator Intervention for Latinos on Hemodialysis: A Single-Arm Clinical Trial. Journal of palliative medicine. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sullivan C, Dolata J, Barnswell KV, et al. Experiences of Kidney Transplant Recipients as Patient Navigators. Transplantation proceedings. 2018;50(10):3346–3350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vargas RB, Ryan GW, Jackson CA, Rodriguez R, Freeman HP. Characteristics of the original patient navigation programs to reduce disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. Cancer. 2008;113(2):426–433. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cervantes L, Jones J, Linas S, Fischer S. Qualitative Interviews Exploring Palliative Care Perspectives of Latinos on Dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(5):788–798. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10260916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Feagin J, Bennefield Z. Systemic racism and U.S. health care. Social science & medicine (1982). 2014;103:7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shavers VL, Shavers BS. Racism and health inequity among Americans. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2006;98(3):386–396. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Racism and Health I: Pathways and Scientific Evidence. The American behavioral scientist. 2013;57(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Charlot M, Santana MC, Chen CA, et al. Impact of patient and navigator race and language concordance on care after cancer screening abnormalities. Cancer. 2015;121(9):1477–1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Genoff MC, Zaballa A, Gany F, et al. Navigating Language Barriers: A Systematic Review of Patient Navigators’ Impact on Cancer Screening for Limited English Proficient Patients. Journal of general internal medicine. 2016;31(4):426–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Patzer RE, Larsen CP. Patient Navigators in Transplantation - where do we go from here? Transplantation. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Phillips S, Nonzee N, Tom L, et al. Patient navigators’ reflections on the navigator-patient relationship. Journal of cancer education : the official journal of the American Association for Cancer Education. 2014;29(2):337–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Phillips S, Villalobos AVK, Crawbuck GSN, Pratt-Chapman ML. In their own words: patient navigator roles in culturally sensitive cancer care. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2019;27(5):1655–1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jolly SE, Navaneethan SD, Schold JD, et al. Development of a chronic kidney disease patient navigator program. BMC nephrology. 2015;16:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]