Abstract

Background

Type II diabetes mellitus (DM2) is a significant risk factor for cancers, including breast cancer. However, a proper diabetic breast cancer mouse model is not well‐established for treatment strategy design. Additionally, the precise diabetic signaling pathways that regulate cancer growth remain unresolved. In the present study, we established a suitable mouse model and demonstrated the pathogenic role of diabetes on breast cancer progression.

Methods

We successfully generated a transgenic mouse model of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 positive (Her2+ or ERBB2) breast cancer with DM2 by crossing leptin receptor mutant (Leprdb/+) mice with MMTV‐ErbB2/neu) mice. The mouse models were administrated with antidiabetic drugs to assess the impacts of controlling DM2 in affecting tumor growth. Magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging was employed to analyze the tumor metabolism.

Results

Treatment with metformin/rosiglitazone in MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mouse model reduced serum insulin levels, prolonged overall survival, decreased cumulative tumor incidence, and inhibited tumor progression. Anti‐insulin resistance medications also inhibited glycolytic metabolism in tumors in vivo as indicated by the reduced metabolic flux of hyperpolarized 13C pyruvate‐to‐lactate reaction. The tumor cells from MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db transgenic mice treated with metformin had reprogrammed metabolism by reducing levels of both oxygen consumption and lactate production. Metformin decreased the expression of Myc and pyruvate kinase isozyme 2 (PKM2), leading to metabolism reprogramming. Moreover, metformin attenuated the mTOR/AKT signaling pathway and altered adipokine profiles.

Conclusions

MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mouse model was able to recapitulate diabetic HER2+ human breast cancer. Additionally, our results defined the signaling pathways deregulated in HER2+ breast cancer under diabetic condition, which can be intervened by anti‐insulin resistance therapy.

Keywords: diabetes, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, breast cancer, metformin, metabolism

Our results define the signaling pathways deregulated in HER2+ breast cancer under diabetic condition, which can be intervened by anti‐insulin resistance therapy.

Abbreviations

- BC

breast cancer

- DM2

type II diabetes mellitus

- IGF‐1

insulin‐like growth factor 1

- AMPK

AMP‐activated protein kinase

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor gamma

- PTEN

phosphatase and tensin homolog

- Her2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- HER2+

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 positive

- ER/PR

estrogen receptor/progesterone receptor

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- FISH

fluorescence in situ hybridization

- OGTT

oral glucose tolerance test

- ITT

insulin tolerance test

- RT

room temperature

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- ATCC

American Type Culture Collection

- MRSI

magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging

- DNP

dynamic nuclear polarization

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- OCR

oxygen consumption rate

- ECAR

extracellular acidification rate

- PKM2

pyruvate kinase isozyme 2

- qRT‐PCR

quantitative reverse transcription‐PCR

- ELISA

enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay

- CI

confidence interval

- PARP

poly ADP ribose polymerase

- 13C

carbon‐13

- FGF1

fibroblast growth factor 1

- MCP1

monocyte chemoattractant protein‐1

- RAGE

receptor for advanced glycosylation end product

1. BACKGROUND

Up to 15% of breast cancer (BC) patients have type II diabetes mellitus (DM2) [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. Diabetic BC patients have significantly worse overall survival and disease‐specific survival when compared with non‐diabetic BC patients, suggesting an association between DM2 and cancer progression [9]. Several causes are possibly involved in the association of DM2 with BC, including hyperglycemia, insulin signaling, insulin‐like growth factor 1 (IGF‐1) signaling, and regulation of endogenous sex hormones [2]. However, the mechanisms linking DM2 (high levels of glucose, IGF1, and insulin) and BC tumor biology remains largely unknown. Alarmingly, the strategy for clinical prevention/treatment to improve the outcome of diabetic BC patients has not been established. Therefore, it is vital to better understand the molecular basis of impact of DM2 on breast cancer growth and to develop an effective prevention/treatment strategy in the context of DM2. Importantly, characterizing the DM2‐regulated cellular signaling pathways requires an immunocompetent mouse model to study and such a model has not been well‐established for treatment strategy design.

Cancer metabolism is one of the important cancer hallmarks in cancer progression [10]. Thus, finding the therapeutic target for modulating cancer cell metabolism has become an important field in cancer research [11, 12, 13, 14]. DM2 linked with high levels of glucose, IGF1, and insulin is expected to affect cancer metabolism, thereby promoting cancer cell growth but its detailed role in metabolism regulation remains not well characterized.

Previous studies indicated that anti‐insulin resistance medications can regulate important signal molecules. For example, metformin/phenformin activates AMP‐activated protein kinase (AMPK) [15] and inhibits respiratory chain complex I in mitochondria [16, 17]. In addition, rosiglitazone can activate peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) and increase phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) protein levels [18]. It can also negatively regulate AKT, which is one of the key regulators in glycolysis [19]. It is conceivable that controlling DM2‐mediated activity to hinder cancer growth could be a useful strategy [20]. However, the metabolic regulatory signaling pathways and cancer cell growth regulatory activity of these insulin resistance medications reagents remain not well characterized. Also, the large scale of employing these anti‐insulin resistance medications for the clinical trials in breast cancer patients remains an important task and a significant challenge to be tackled.

In this study, we established a mouse breast cancer model with DM2 and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (Her2/ErbB2) overexpression (MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db) by laborious backcrossing. The mouse models were further analyzed for the impacts of DM2 on promoting HER2/ErbB2‐overexpressing breast cancer growth. Anti‐insulin resistance drugs were explored to suppress the cancer growth. Our findings suggested that anti‐insulin resistance treatments could be used as the potential therapeutic methods for DM2 patients with HER2 positive (HER2+) breast cancer. Thus, the MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mouse model becomes a valuable tool to assess functional regulation and screen potential treatments in preclinical settings.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Patients and clinical data review

The retrospective study was conducted under an approved protocol by the Institutional Review Board of Sun Yat‐sen University Cancer Center (Guangzhou, Guangdong, China), in compliance with the institutional guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki principles. A case‐matched control design was used. HER2+ breast cancer patients treated at Sun Yat‐sen University Cancer Center between January 1, 2000 and September 30, 2010 were identified. The inclusion criterion was the patient with pre‐existing DM2 at the time of breast cancer diagnosis. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) male sex; (2) incomplete estrogen receptor/progesterone receptor (ER/PR) characterization; (3) type I diabetes; (4) resolved gestational diabetes; (4) incomplete records. Control non‐diabetic HER2+ breast cancer patients were matched 2:1 to each case by menopausal status, ER/PR status and stage. Cancer stage was defined according to the clinical stage at the time of diagnosis using the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual. From the pathology reports, the HER2+ status was defined as a tumor having a staining intensity of 3+ on immunohistochemistry (IHC) or amplification (>2.2 copies) of the HER2 gene as demonstrated by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). The ER and PR expression were also recorded based on the pathology reports. The diabetes status was determined based on the recorded medical history and was confirmed by antidiabetic pharmacotherapy in both the medical and pharmacy records. Overall survival time was defined as the duration between the date of cancer diagnosis and the date of death. If the patient was not known dead, survival time was censored at the date of last follow‐up during the monitoring period. Antidiabetic measures were classified as (1) insulin or insulin analogues, (2) biguanides, (3) insulin secretagogues (e.g., sulfonylureas and meglitinides), and (4) others.

2.2. Mouse model

MMTV‐ErbB2mice (strain name: Friend leukemia virus B [FVB]‐Tg [MMTV‐ErbB2mice] NK1Mul/J; stock number: 005038) and Leprdb/+ mice (strain name: B6.BKS [D]‐Leprdb /J; stock number: 000697) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine, USA). The MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db double‐transgenic mice were generated by crossing male MMTV‐ErbB2 mice with female Lepr db/+ mice in an FVB genetic background. The strategy for crossing to establish our animal model was necessary because MMTV‐ErbB2 female mice, although fertile, are unable to lactate, and the Leprdb/db mice are infertile. This breeding strategy produced all 3 Lepr genotypes (+/+, +/‐, and ‐/‐). The offspring were maintained with their mothers until age 21 days and then subjected to genotyping. All mouse studies were carried out under a protocol approved by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.3. Genotyping, weight measurement, oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), insulin tolerance test (ITT) and glucose measurement

The mice were tailed at weaning and DNA was extracted from the tail for genotyping using a standard protocol provided by The Jackson Laboratory. The mice were weighed twice each week. The weight data were plotted by genotypes.

OGTT and ITT were performed as previously described [21, 22]. Briefly, for OGTT, the mice fasted overnight and were given glucose (1 g/kg) via oral gavage. Then, we obtained blood samples from the tail vein for glucose measurement at 15, 30, 60, and 120 minutes post‐glucose treatment. For ITT, mice fasted for 6 h. Insulin (1 U/kg) was intraperitoneally injected and blood was collected from the tail vein for glucose measurement at 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes post‐insulin injection. The blood samples were applied to glucose test strips and measured by a regular glucose meter.

2.4. Mammary gland whole‐mount staining

Mammary gland whole‐mount staining was performed following standard procedures [23]. Briefly, mammary glands were fixed on glass slides with Carnoy's solution (glacial acetic acid: chloroform: ethanol, 1:3:6) overnight at room temperature (RT). The glands were rehydrated prior to overnight staining in aluminum carmine; for that staining, carmine (1 g) and aluminum potassium sulfate (2.5 g) were boiled for 20 min in distilled water, filtered and brought to a final volume of 500 mL. The glands were then stored in 70% ethanol at 4°C overnight. Photographs were taken under an objective lens (4 × magnification) using a digital camera mounted on a Leica MZ12.5 microscope (Leica Instruments, Wetzlar, Germany). The tumor area was quantified using Image‐Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA).

2.5. Antidiabetic drug treatments

For in vivo experiments, 8‐week‐old MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice were treated with metformin or rosiglitazone. Metformin (cat# ALX‐270‐432‐G005; Enzo Life Sciences; Farmindale, NY, USA) was dissolved directly in distilled water (0.5 g/kg/day). Rosiglitazone (cat# 71740; Cayman Chemical; Ann Arbor, MI, USA) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide as a stock solution at 100 mmol/L and added to distilled water (1.5 mg/kg/day). The drug concentrations were within the physiologically relevant levels for diabetic patients. For in vitro studies, metformin was directly dissolved in cell culture medium at the desired concentrations and 100 mmol/L stock rosiglitazone was added to the cell culture medium at the desired concentrations.

2.6. Survival analysis

To assess the effect of diabetes on survival, we compared the survival duration of the MMTV‐ErbB2/Lepr+/+ mice (n = 16) with that of the MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice (n = 12). To assess the effect of anti‐insulin resistance treatments on survival, mice were randomly assigned to different cohorts as they became available by breeding. We compared the survival duration of the MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice treated with metformin (n = 14) or rosiglitazone (n = 14) with that of the untreated MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice (n = 12). All mice were monitored weekly for tumor growth. We used CO2 inhalation as our euthanasia method according to institutional protocol when tumor size reached the standard for euthanasia.

2.7. Histologic staining and mitosis count

After the mice were euthanized, tumor samples were removed, washed in phosphate‐ buffered saline solution, weighed and fixed in 10% modified formalin. After incubation in 70% ethanol overnight, the samples were embedded in paraffin. Paraffin‐embedded sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin according to standard procedures [24, 25] and a certified pathologist counted the mitotic cells under high‐power fields (40 × magnification).

2.8. Cell lines and cell culture

Mouse cancer cell lines were isolated from the MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice and maintained in high‐glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; cat# SH3024301; HyClone; Marlborough, MA, USA) containing 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS; cat# SH30070.03; HyClone; Marlborough, MA, USA . The human HER2+ breast cancer cell lines (BT‐474 and MDA‐MB‐361) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Briefly, cells were maintained in DMEM/high glucose supplemented with 10% FBS and cultured at 37°C in 5% carbon dioxide.

2.9. Magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRSI)

To determine the pyruvate/lactate conversion in mice, we performed MRSI [26]. Briefly, all experiments were performed on a 7 T Biospec small animal MRI scanner (USR70/30, Bruker Biospin MRI, MA) equipped with BGA12 gradients (120 mm inner diameter, Gmax = 400 mT/m). A dual‐tuned 1H/13C birdcage coil with 72‐mm inner diameter (1P T10334, Bruker Biospin MRI, Inc., Ettlingen, Germany) was used for acquiring 1H reference images and performing hyperpolarized 13C dynamic spectroscopy. Axial and coronal slices were prescribed to contain tumors in various locations of mammary fat pads. A slice‐selective pulse acquire 13C sequence (TR/TE = 2000/2.4 ms, 2048 readout points, 4.96 kHz BW, 10 flip angle, 96 repetitions) was initiated prior to ∼10 s the injection of 200 μL of the hyperpolarized [1‐13C] pyruvate solution was performed via tail vein. All experiments were performed on the same mice before and after anti‐insulin resistance treatments were administered.

2.10. 13C polarization process

Samples composed of neat 13C pyruvic acid (26 mg) containing the triarylmethyl free radical OX063 (15 mmol/L; GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) and ProHance (1.5 mmol/L; Bracco Diagnostics, Milan, Italy) were polarized with dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) at 1.4 K using a HyperSense DNP Polarizer (Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK) [26]. Each sample was inserted into a 3.35‐Tesla vertical bore magnet and irradiated for more than 45 min with 94.15 GHz microwave radiation. Each frozen sample was then rapidly dissolved at 180°C in 4‐mL of buffer containing 40 mmol/L Tris, 80 mmol/L sodium hydroxide and 50 mmol/L sodium chloride to produce a final isotonic and neutral solution containing 80 mmol/L hyperpolarized 13C pyruvate.

2.11. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) acquisition

All experiments were performed with a 7 Tesla BioSpec small animal MRI scanner (USR70/30, Bruker Biospin Corp., Billerica, MA, USA) equipped with BGA12 gradients (120‐mm inner diameter, maximal constant gradient strength = 400 mT/m), as previously described [26, 27]. A dual‐tuned 1H/13C birdcage coil with a 72‐mm inner diameter (1P T10334, Bruker Biospin Corp., Billerica, MA, USA) was used to acquire 1H reference images and to perform hyperpolarized13C dynamic spectroscopy. Axial and coronal slices were prescribed to contain tumors in various locations of the mammary fat pads. A slice‐selective pulse to acquire 13C sequence (time to repetition/time to echo = 2000/2.4 ms, 2048 readout points, 4.96 kHz bandwidth, 10 flip angle, 96 repetitions) was initiated approximately 10 seconds prior to injecting the hyperpolarized 13C pyruvate solution (200 μL) into the mouse's tail‐vein.

All MRSI data were processed and analyzed using custom MATLAB (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA) scripts developed in laboratory. For hyperpolarized 13C experiments, apodization was applied by a 15‐Hz exponential window and the data were processed by fast Fourier transformation. The signal intensity from the 13C metabolites was calculated on the basis of the spectral area over the full width at half maximum, the sum of spectra over all repetitions and the total lactate signal normalized by the sum of total pyruvate and lactate signals.

2.12. Measurement of oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR)

To further determine the effect of anti‐insulin resistance treatment on cancer metabolism in vitro, we isolated cancer cells from tumors of the untreated MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice and cultured the cells in a 24‐well microplate (Seahorse Bioscience, Billerica, MA, USA). The OCR and ECAR were measured via a Seahorse XFe24 instrument (Seahorse Bioscience, Bilerica, MA, USA) according to the previously described procedure [27]. Briefly, mouse tumor cells were pretreated with a low concentration of metformin (300 μmol/L) and then seeded in an XF24 microplate 16 h before the experiment. Just before the Seahorse extracellular flux assay, the culture medium was replaced with assay medium (low‐buffered DMEM containing D‐glucose [25 mmol/L], sodium pyruvate [1 mmol/L] and L‐ glutamine [1 mmol/L]) and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. After measuring the baseline OCR and ECAR, we sequentially injected 75 μL of mitochondrial respiratory chain inhibitors into each well to reach the final working 1 × concentrations. After waiting 5 min to equally expose the cancer cells to the chemical inhibitors, we measured the OCRs (pmol/minute/mg) and ECARs (mpH/minute/mg).

2.13. Proliferation assay

Human HER2+ breast cancer cell lines (BT‐474 and MDA‐MB‐361) were split at low density in 100‐mm2 dishes and cultured in DMEM/high glucose medium with 10% FBS overnight. On the second day, the cells were treated with various concentrations of metformin in 10 mL of medium for 3 days. On the fifth day, the cells were treated with various concentrations of metformin in an additional 10 mL of fresh medium for another 3 days. All the supernatants and cells were collected and the cells were counted using a Z1 Coulter Particle Counter (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) [28, 29]. Triplicate samples were collected at each time point.

2.14. Western blot analysis

The BT‐474 and MDA‐MB‐361 cells were treated with various concentrations of metformin or rosiglitazone for 2 days or 6 days. Standard Western blotting of whole‐cell lysates were performed with antibodies for pyruvate kinase isozyme 2 (PKM2), pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase isoenzyme 1, poly ADP ribose polymerase (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) and Myc (Epitomics, Burlingame, CA, USA), β‐actin (Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used as a loading control. To determine the Myc proteasome‐dependent degradation, we treated BT‐474 cells with metformin for 2 days and 10 μmol/L of MG132 was applied 6 h before sample collection. Cell lysates were subjected to standard Western blotting for Myc. For the Myc ubiquitination assay, BT‐474 cells were treated with MG132 for 6 hours before sample collection as previously described [30, 31]. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti‐ubiquitin antibody and polyubiquitinated Myc was immunoblotted with anti‐Myc antibody. To determine the Myc turnover rate, we added cycloheximide (500 μg/mL) to the culture medium and collected samples at different time points according to the procedure previously described [32]. Myc density was quantified using Image J software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) and plotted with GraphPad Prism (San Diego, CA, USA) for Windows.

2.15. Quantitative reverse transcription‐PCR (qRT‐PCR)

For qRT‐PCR, total RNA was collected from BT‐474 cells using TRIzol reagents (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA,USA) and cDNA was synthesized using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). qRT‐PCR was performed with an iQ‐SYBR Green Supermix (Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and a CFX96 RT‐PCR detection system (Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). 18S rRNA was used for normalization. The Myc primer sequences were as follows: forward primer 5'‐GCTGTAGTAATTCCAGCGAGAGACA‐3' and reverse primer 5'‐CTCTGCACACACGGCTCTTC‐3'. The PKM2 primer sequences were as follows: forward primer 5'‐CGCCCACGTGCCCCCATCATTG‐3' and reverse primer 5'‐ CAGGGGCCTCCAGTCCAGCATTCC‐3'. The 18s rRNA primer sequences were as follows: forward primer 5’‐CGGCGACGACCCATTCGAAC‐3’ and reverse primer 5’‐ GAATCGAACCCTGATTCCCCGTC‐3’.

2.16. Enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Blood samples were taken from groups of MMTV‐ErbB2/Lepr+/+ mice, MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice, metformin‐treated MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice and rosiglitazone‐ treated MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice. Serum samples were collected in BD Microtainer tubes with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (cat# 365973, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and were frozen at ‐80°C. An ELISA was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (rat/mouse insulin 96‐well plate assay, cat# EZRMI‐13K, EMD Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). Briefly, we thawed the mouse serum samples on ice and added 10 μL of sample to each well of the plate. Then, we added 80 μL of detection antibody to each well. The plate was covered with plate sealer and incubated at RT for 2 h on an orbital microtiter plate shaker. After washing the plate with wash buffer, we added 100 μL of enzyme solution to each well and incubated the plate at RT for 30 min on the plate shaker. After washing the plate again with wash buffer, we added 100 μL of substrate solution to each well and incubated the plate on the shaker for 20 min. Then, we added 100 μL of stop solution to each well and measured the absorbance at 450 nm and 590 nm using ELISA plate reader.

2.17. Multiplex assay

Tumor samples were isolated from the MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice treated with metformin or rosiglitazone and from those in the control group and were stored at ‐80°C. Fresh tumor lysates were prepared on the assay day and a multiplex assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (11‐Plex AKT/mTOR Panel‐Phosphoprotein, cat# 48‐611, EMD Millipore) or as previously described [22].

Briefly, tumor lysates were diluted 1:1 with MILLIPLEXMAP assay buffer 2. We added bead suspension and diluted lysates and incubated the assay plate overnight at 4°C on a plate shaker that was protected from light. On the second day, after washing the plate with wash buffer, we added biotinylated reporter to each well and incubated the plate for 1 h at RT on a plate shaker that was protected from light. After removing the reporter via vacuum filtration, we added MILLIPLEXMAP streptavidin‐phycoerythrin to each well and incubated the plate for 15 min at RT on the plate shaker, which was protected from light. Without removing the streptavidin‐phycoerythrin, we added MILLIPLEXMAP amplification buffer to each well; the plate was incubated for 15 min at RT on the plate shaker and was protected from light. Finally, the buffer was removed via vacuum filtration and the beads in each well were suspended using MILLIPLEXMAP assay buffer 2. The plate was read using a Luminex 200 analyzer (Austin, TX, USA).

2.18. Adipokine array analysis

Serum samples were prepared as previously described for the ELISA. An adipokine array assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (mouse adipokine array, cat# ARY013, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Briefly, membranes were blocked for 1 h on a rocking platform. Three serum samples from each group of mice were premixed together and a detection antibody cocktail was added to serum samples following 1 h of incubation at RT. After removing the blocking solution, we added the sample‐antibody mixtures to the membranes and incubated the membranes overnight at 4°C on a rocking platform. After washing the membranes with wash buffer, we incubated the membranes with streptavidin‐horseradish peroxidase solution for 30 min and subjected them to x‐ray film exposure.

2.19. Statistical analysis

The log‐rank test was used to determine the statistical significance of differences in survival duration. Kaplan‐Meier survival curve were used. An unpaired t test with Welch's correction was performed when comparing 2 groups. One‐way analysis of variance or Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test were performed when comparing 3 or more groups. All tests were performed using GraphPad Prism version 6.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Results are expressed as means ± 95% confidence interval (CI). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

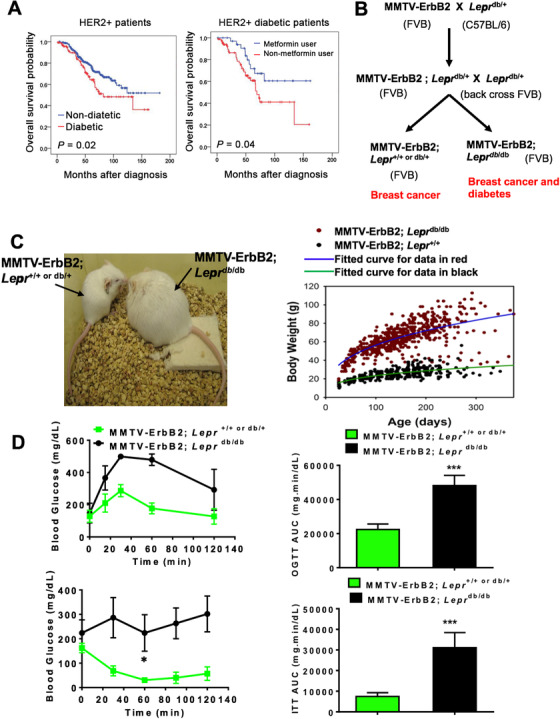

3.1. Diabetes is associated with poor overall survival of HER2+ breast cancer

To investigate the impact of diabetes on breast cancer, we conducted a case‐matched control study of Chinese HER2+ breast cancer patients treated at the Sun Yat‐sen University Cancer Center (Guangzhou, Guangdong, China) between January 1, 2000 and September 30, 2010. We found that out of 1511 HER2+ patients, there were 112 (7.4%) cases with pre‐existing DM2 at the time of breast cancer diagnosis. A total of 98 (87.5%) cases with DM2 who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria constituted the cohort for review. Controls from the non‐diabetic HER2+ breast cancer patients were matched to each case. Kaplan‐Meier analysis of overall survival showed that the Chinese HER2+ breast cancer patients with pre‐existing DM2 had a shorter survival (75th percentile = 53.7 months) than non‐diabetic patients (75th percentile = 75.4 months; log rank test; P = 0.02; Figure 1A left panel). We further classified them into 2 groups based on whether they received metformin treatment at the time of cancer diagnosis. Kaplan‐Meier analysis of overall survival of these 2 groups showed that the diabetic patients who received metformin at the time of cancer diagnosis had significantly longer overall survival than those who did not receive metformin (log rank test; P = 0.04; Figure 1A right panel). Therefore, the association of DM2 with poor HER2+ breast cancer survival was observed in our cohort study.

FIGURE 1.

Type II diabetes (DM2) promotes HER2+ breast cancer. A. Pre‐existing DM2 is associated with shorter overall survival than non‐diabetic HER2+ breast cancer patients in a case‐match control comparison (left). Metformin use at the time of cancer diagnosis is associated with longer overall survival in diabetic HER2+ breast cancer patients (right). B. Scheme of mouse breeding. MMTV‐ErbB2mice (FVB background) were crossed with Leprdb/+ mice (CB57 BL/6 background). Leprdb/+ mice (CB57 BL/6) were back crossed with FVB background mice several generations to obtain the pure FVB background for generating MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db in a FVB background. Genotyping was performed and mice that carried the MMTV‐ErbB2gene were collected for further study. C. Generated MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice (FVB) manifested the expected phenotype with increased bodyweight. Mouse body weight change for the MMTV‐ErbB2/Lepr+/+ mice versus the MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice. D. Oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTTs) and Insulin tolerance tests (ITTs) were performed on MMTV‐ErbB2/Lepr+/+ mice (n = 6) and MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice (n = 5). Values are means ± 95% confidence interval (CI); ***, P <0.05. The area under the curve was analyzed to show statistical significance.

Due to the limitation of obtaining human cancer samples for further analysis and performing experiments to monitor the tumor progression under the impact of DM2, we set up a mouse model that develops breast cancer under the influence of DM2 for cancer study. To establish a diabetic breast cancer mouse model for treatment strategy design, we generated a diabetic HER2+ breast cancer mouse model as shown in Figure 1B by breeding mutant Leprdb/+ mice (C57 BL/6 background) with transgenic MMTV‐ErbB2mice FVB background. Leprdb/+ C57 BL/6 background mice were laboriously backcrossed with FVB mice several generations to obtain Leprdb/+ with FVB genetic background and we finally obtained the MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice with FVB background. Due to the genetic impact from Lepr, the MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice weighed significantly more than their control MMTV‐ErbB2/Lepr+/+ littermates (Figure 1C). This over weighted situation also leads to type II diabetes mellitus (Figure 1D). MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice indeed manifested DM2 after carrying the transgenes, as validated via OGTT and ITT (Figure 1D). The above data indicated that we successfully established an ErbB2+ breast cancer animal model of type II diabetes in FVB genetic background.

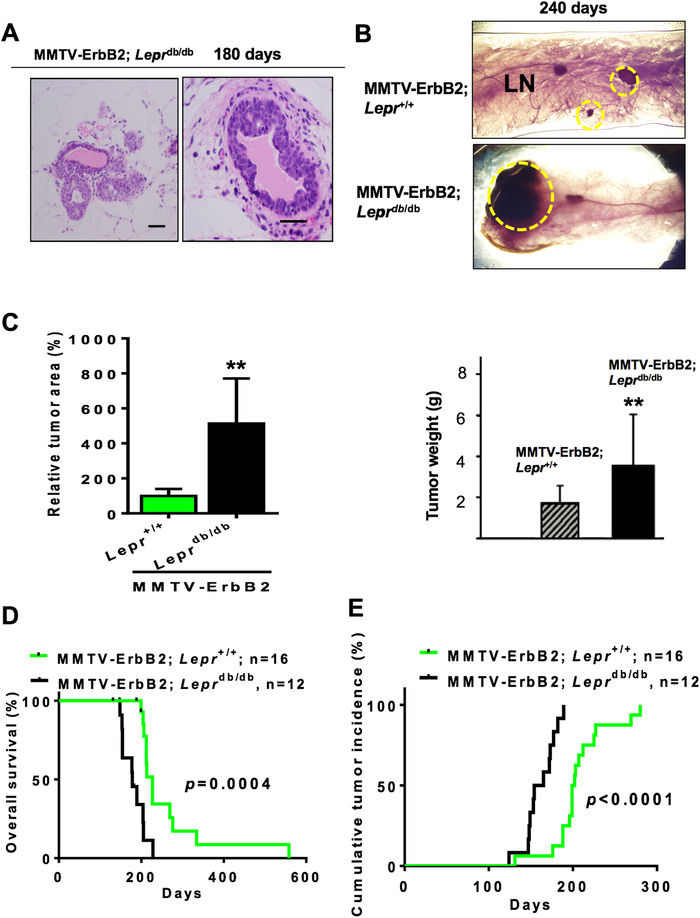

3.2. Early tumor onset and poor cancer survival rate in diabetic ErbB2+ breast cancer mouse model

We found that MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice at 180 days developed carcinoma while the MMTV‐ErbB2/Lepr+/+ mice did not (Figure 2A). We dissected paired mice of the same age (240 days) and isolated the mammary glands for whole‐mount staining (Figure 2B) and found that the tumor volume in representative mammary glands and tumor weight was significantly greater in the MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice than in the MMTV‐ErbB2/Lepr+/+ mice at the end point (Figure 2C). Importantly, the MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice died at a significantly younger age than the MMTV‐ErbB2/Lepr+/+ mice (P = 0.0004; Figure 2D). The median survival durations for the MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db and the MMTV‐ErbB2/Lepr+/+ mice were 5.9 months and 7.6 months, respectively. Tumor incidence was also dramatically more in the MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice than in the MMTV‐ErbB2/Lepr+/+ mice (P < 0.0001; Figure 2E). Thus, the effect of diabetes has impact on early onset of breast cancer progression and leads to bigger tumor volume and a worse outcome in the diabetic Her2+ breast cancer mouse model.

FIGURE 2.

Diabetes condition accelerates the growth rate of ErbB2 cancer. A. Representative images of tumor growth of MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice at age of 180 days. Scale bar, 100 μm. B. Representative mammary whole‐mount staining for the indicated mice. The tumor areas are circled in yellow. LN, lymph node. Scale bar, 1mm. C. Quantitative analysis of the yellow circled pictures in (B) were taken under a dissection microscope (30 × ), and the relative tumor area was quantified by Image‐Pro software. Values are means ± 95% CI. Mouse number: MMTV‐ErbB2/Lepr+/+ (n = 13); MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db (n = 12). Quantification of tumor weight from tumors of indicated mouse model at age of 240 days. **, P < 0.01. D. Overall survival duration and (E) cumulative tumor incidence for the MMTV‐ Her2/Lepr+/+ mice (n = 16) versus the MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice (n = 12).

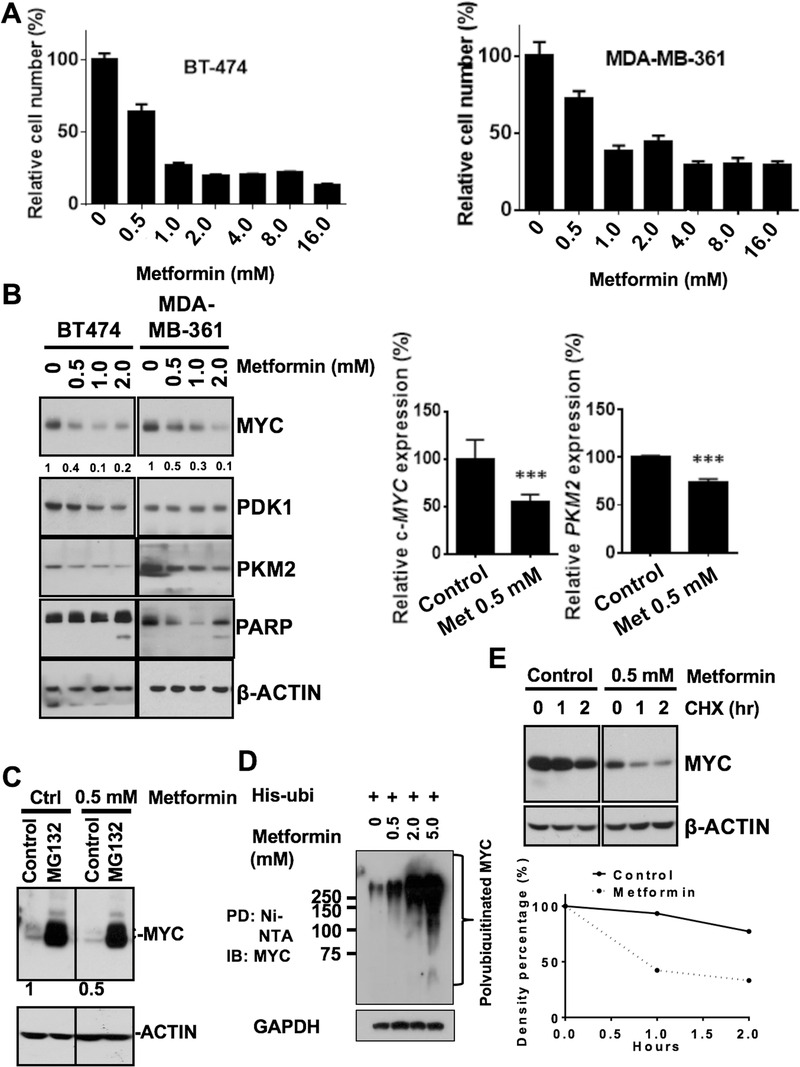

3.3. Metformin inhibits proliferation and induces ubiquitin‐mediated Myc degradation in human HER2+ breast cancer cell lines

To investigate whether controlling the diabetic situation can regulate tumorigenesis, we assessed the effect of anti‐insulin resistance treatments in repressing cancer progression. We treated human HER2+ breast cancer cells (BT‐474 and MDA‐MB‐361 cells cultured under high glucose conditions) with anti‐insulin resistance medicine metformin. We found that metformin efficiently inhibited cell proliferation (1‐way analysis of variance, P < 0.001) at a dose of 0.5 mmol/L (Figure 3A). We therefore investigated the targets of metformin treatment in human HER2+ breast cancer cell lines. Western blot results showed that metformin caused poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) cleavage and suppressed Myc expression (Figure 3B left panel). Metformin also suppressed the expression of PKM2, the key Myc‐controlled enzyme for pyruvate/lactate conversion. We also performed qRT‐PCR in cells to determine the mRNA expression level of Myc and its downstream targets in human HER2+ breast cancer cells. Our data indicated that both Myc and PKM2 were downregulated at the transcriptional level in cells treated with 0.5 mmol/L metformin (P < 0.0001; Figure 3B right panel). At the same time we performed a proteasome inhibition assay and found that metformin‐mediated Myc downregulation could be rescued when treated with MG132, suggesting that metformin could suppress Myc expression through proteasome‐dependent degradation pathway (Figure 3C). We then performed an ubiquitination assay and found that metformin increased the poly‐ubiquitination of Myc in a dose‐dependent manner (Figure 3D), confirming that metformin mediated Myc degradation through an ubiquitin‐mediated proteasome degradation pathway. Consistently, the metformin‐treated cells had a higher Myc protein turnover rate than the control cells (Figure 3E). These results validate that Myc and PKM2 are part of the functional targets of metformin in HER2+ cancer.

FIGURE 3.

Metformin‐mediated HER2+ human breast cancer cell growth inhibition and Myc degradation. A. BT‐474 and MDA‐MB‐361 cell proliferation after 6 days of metformin treatment at various concentrations. One‐way analysis of variance, P <0.001. B. Western blot analysis of key metabolic protein expression and PARP cleavage after 6 days of metformin treatment. C. Metformin‐mediated Myc downregulation in the presence of MG132. The BT‐474 cells were pretreated with metformin for 2 days and cell lysates were collected after 6 h of MG132 treatment. Myc protein levels were detected by western blot. D. Metformin affects Myc ubiquitination. BT‐474 cells were treated with MG132 for 6 h before harvesting. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (PD) with anti‐ubiquitin antibody and polyubiquitinated Myc was immunoblotted (IB) with anti‐Myc antibody. The highly ubiquitinated Myc on the gel was indicated. E. Metformin reduces Myc turnover rate. BT‐474 cells were pretreated with metformin for 2 days and cell lysates were collected after cycloheximide (CHX) treatment at various time points. Myc protein level was detected by western blot (upper panel). Quantitative analysis for Myc protein expression level was summarized in lower panel. Density was set as 100% at the zero time point in each group.

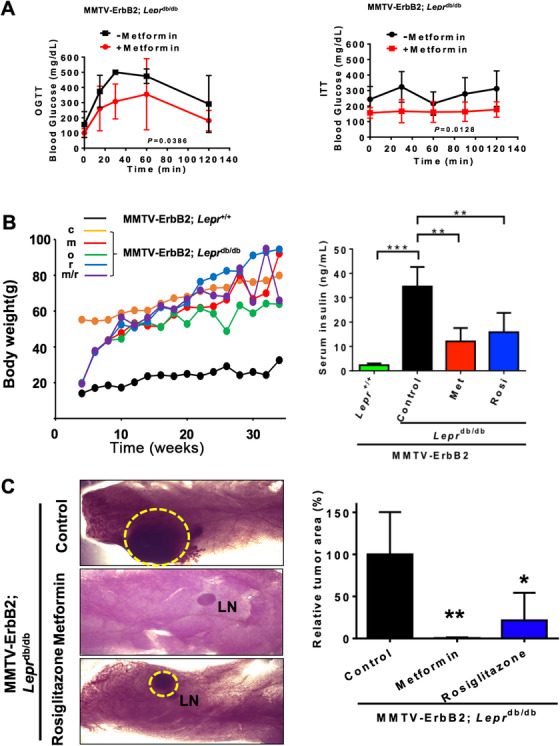

3.4. Metformin improves insulin tolerance and decelerates the tumor onset in the diabetic ErbB2+ breast cancer mouse model

Based on the role of metformin in inhibiting the growth of HER2+ breast cancer, we set to investigate the effect of metformin in MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice model. We first performed the OGTT and ITT and found that diabetic condition of MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice was improved after metformin treatment (Figure 4A). While the body weight of MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice changes slightly by metformin/rosiglitazone treatment (Figure 4B left panel), the serum insulin level was dramatically improved after the metformin/rosiglitazone treatment, as indicated by ELISA analysis for serum insulin levels (Figure 4B right panel). The insulin level was 15 times higher in the MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice than in the MMTV‐ErbB2/Lepr+/+ mice (P < 0.001) and was dramatically lower in the mice treated with metformin or rosiglitazone (P < 0.01; Figure 4B right panel). We then studied the impact of metformin/rosiglitazone treatment on the tumorigenesis in MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice. The MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice were assigned to 1 of 3 groups: treatment with metformin, rosiglitazone or no treatment. We isolated the mammary glands from mice of similar ages for whole‐mount staining. Whole‐mount staining showed that anti‐insulin resistance treatments decelerate tumor progression in the mammary glands and significantly reduced the tumor size (P < 0.0001; Figure 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Anti‐insulin resistant treatments inhibit cancer progression in MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice. A. Metformin improved type II diabetes in the MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db diabetic HER2+ breast cancer mouse model. OGTT and ITT were performed on the MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice (n = 4) before and after 2 weeks of metformin treatment. B. Mouse body weight change for the MMTV‐ErbB2/Lepr+/+ mice versus the MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice under the anti‐insulin resistant treatments. c, untreated control; m, metformin; o, orlistat; r, rosiglitazone; m/r, metformin+rosiglitazone. ELISA analysis for serum insulin levels from mice from the 2 treatment groups and untreated controls. Lepr+/+, MMTV‐ErbB2/Lepr+/+ mice (n = 10); Control, untreated MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice (n = 12); Met, metformin‐treated MMTV‐Her2/Leprdb/db mice (n = 10); Rosi, rosiglitazone‐treated MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice (n = 16). Values are displayed as means ± 95% CI. C. Representative mammary whole‐mount staining for the MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice from the 3 treatment groups: control (n = 12), treated with metformin (n = 6) and treated with rosiglitazone (n = 6). The tumor areas are circled in yellow (left panel). LN, lymph node. Quantitative bar graph represents the tumor size from C (right panel). Values are means ± 95% CI. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

3.5. Anti‐insulin resistance medications reduce cancer metabolism in vivo

To determine whether anti‐insulin resistance treatments would change the metabolic process in the MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice, we performed MRSI to monitor the dynamic flux of pyruvate into lactate, which is the end product of aerobic glycolysis and an important signature for cancer metabolism. Using hyperpolarized technology, we injected the substrate carbon‐13 (13C) pyruvate into the MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice and traced the 13C signal to lactate in vivo. We performed MRI before the substrate 13C pyruvate injection to locate the tumor area. Metabolic flux of pyruvate‐to‐lactate reaction is lower in MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice (metformin/rosiglitazone treated) when compared with vehicle treated mice, as assayed by 13C‐pyruvate‐based MRSI (Supplementary Figure S1A). By quantitation, metformin treatment for 2 weeks yielded about an 80% reduction in pyruvate/lactate conversion (Supplementary Figure S1B), and 2 days of rosiglitazone treatment yielded about a 50% reduction (Supplementary Figure S1B). These data indicated that anti‐insulin resistance treatments reduced pyruvate/lactate conversion and altered cancer metabolism in vivo.

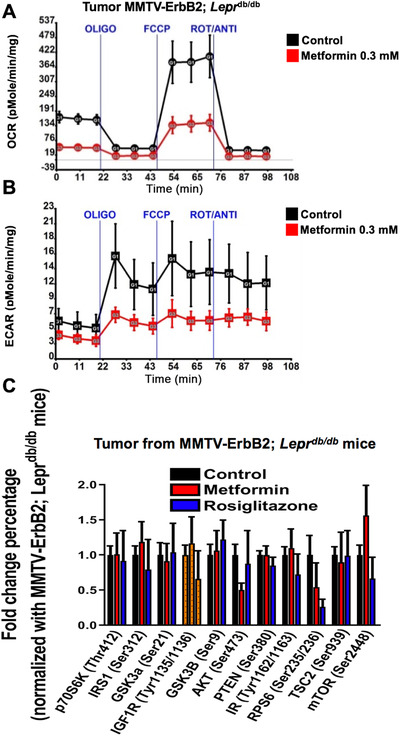

3.6. Metformin reduces mitochondrial respiration capacity and glycolysis

To further evaluate the effect of metformin on cancer metabolism, we isolated cancer cells from the primary tumors of the MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice and measured the OCR and the ECAR. The mean OCR was lower in cells treated with metformin (0.3 mmol/L) than in untreated cells (Figure 5A), indicating that the mitochondrial respiration capacity was reduced. The metformin‐treated cells also had decreased ECARs, indicating that lactate production was attenuated and confirmed that metformin reduced glycolysis (Figure 5B), as we observed in MRSI metabolic flux of pyruvate‐to‐lactate experiment in vivo. These data suggest that metformin changed the cancer metabolism by reducing mitochondrial respiration and impacting on both anaerobic and aerobic glycolysis. As mTOR/AKT signaling is involved in cancer metabolism deregulation, we then examined the possible deregulation in MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice tumors after the treatment of metformin/rosiglitazone. We found that metformin/rosiglitazone medications can abrogate the activation of the mTOR/AKT signaling pathway in the mouse tumors as shown by the reduced phosphorylation of AKT‐S473 and RPS6‐S235/S236 (Figure 5C).

FIGURE 5.

Anti‐insulin resistant treatments reduce cancer metabolic rate. A‐B. OCR (A) and ECAR (B) were measured in tumor cells treated with metformin and untreated controls. Tumor cells were harvested from the untreated MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice and seeded into a 96‐well plate for Seahorse analysis. Values are means ± standard deviation. OLIGO, oligomycin; FCCP, carbonyl cyanide‐p‐trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone; ROT/ANTI, rotenone and antimycin A. C. Multiplex analysis for the mTOR/AKT signaling pathway in the tumors harvested from untreated MMTV‐Her2/Leprdb/db mice (n = 12, control) and those treated with metformin (n = 6) or rosiglitazone (n = 6). Values are means ± standard deviation.

3.7. Metformin/rosiglitazone changes the adipokine profiles of tumors, suppresses high mitotic counts, and increases poor survival in MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice

Because DM2 is a severe metabolic disease and increases body weight and adipose tissue, we investigated and found that the adipokine profile changed in MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice (Supplementary Figure S2A). We found that drug treatments reversed the effect of DM2 on the expression levels of adiponectin [33], fibroblast growth factor 1 (FGF1) [34, 35], monocyte chemoattractant protein‐1 (MCP1) [36], and receptor for advanced glycosylation end products (RAGE) [37] (Supplementary Figure S2B). These changes in adipokines induced by anti‐insulin resistance treatments may block the promoting effect of diabetes and obesity on HER2+ breast cancer progression. These findings highlight the complexity of the DM2‐mediated cancer promoting process in vivo and support the emerging paradigm that physiological conditions of DM2 such as adipokine production are subjected to regulation at various levels via the act of metformin/rosiglitazone.

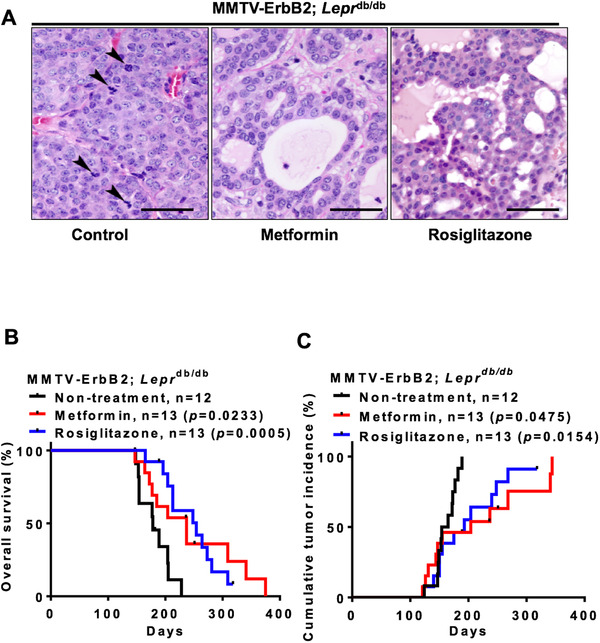

Histologic analysis results showed that the tumor samples from MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice were poorly differentiated, with solid growth patterns, high nuclear grades and high mitotic counts. Compared with the control samples, the tumor samples from the metformin/rosiglitazone treatment groups were moderately differentiated, with glandular formation, and lower mitotic counts (Figure 6A). Importantly, treatment with metformin or rosiglitazone prolonged overall survival (Figure 6B) and reduced tumor incidence (Figure 6C) in the MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mouse model. Therefore, anti‐insulin resistance medications can improve survival in diabetic ‐ErbB2‐expressing mouse breast cancer model, recapitulating the observation in human HER2‐overexpressing cohort.

FIGURE 6.

Anti‐insulin resistant medications elevate cancer survival rate in MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice. A. Tumor samples were harvested from the 3 treatment groups (Metformin, Rosiglitazone, and Control) and paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Pictures were taken under 40 × magnification and were analyzed by a pathologist. Arrows indicate mitosis. Scale bar: 100 μm. B. Overall survival duration for the untreated MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice (n = 12; Control) and for those treated with metformin (n = 13) or rosiglitazone (n = 13). C. Cumulative tumor incidence rate for the MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice in the 3 treatment groups (Metformin, Rosiglitazone, and Control).

4. DISCUSSION

DM2 has been implicated in a wide variety of cancers, including breast cancer. Here, we demonstrated that DM2 promotes the progression of HER2+ breast cancer and this aggressiveness is attenuated by metformin and rosiglitazone. Significantly, we successfully established the first transgenic mouse model with diabetes, obesity and breast cancer, and confirmed that these mice's survival duration was shorter than that of the control mice. Furthermore, we demonstrated that metformin and rosiglitazone significantly prolonged overall survival and altered the metabolic status of HER2+ breast cancer in the mouse model. Our results provide insights into the potential therapeutic value of anti‐insulin resistance medications for treating diabetic HER2+ breast cancer patients.

Previous studies have tried to establish diabetic breast cancer model, but failed to establish a significant one. Cleary et al. [38] and Zheng et al. [39] crossed MMTV‐TGF‐α mice or MMTV‐Wnt‐1 mice with Leprdb/+ mice and maintain the mice in a C57BL/6 genetic background to investigate the contribution of diabetes (due to leptin receptor deficiency) in promoting cancer growth. However, they have made a wrong turn by performing the experiment in a C57BL/6 genetic background by backcrossing MMTV transgenic mice (FVB) back to C57BL/6 genetic background. They concluded that the leptin receptor deficiency suppressed the development of mammary tumors rather than promoting cancer growth. Thus, diabetic breast cancer model was not established. This is a misleading conclusion as the C57BL/6 genetic background of the MMTV‐TGF‐α mice or MMTV‐Wnt‐1 mice becomes resistant to tumor progression in mouse models. This type of animal model experiment needs to be performed in FVB background. MMTV‐TGF‐α/Leprdb/db mice or MMTV‐Wnt‐1/Leprdb/db mice in a C57BL/6 genetic background is resistant to cancer growth, thus is doomed for inconclusive results. In our transgenic mouse model, we performed our studies in a tumor‐prone FVB genetic background instead of a tumor‐resistant C57BL/6 genetic background and proved that DM2 promoted HER2+ breast cancer progression. The MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db experiment was established for Her2+ breast cancer and the breeding has taken a long time to achieve for this precious model. To our knowledge, we are the first group to successfully generate hyperinsulinemic, hyperglycemic and obese MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice model in FVB background. We established this mouse model to determine the mechanism by which anti‐insulin resistance agents suppress Her2+ breast cancer progression. It is clear there is a limitation of obtaining human cancer samples for monitoring the tumor development under the impact of DM2; therefore, setting up an animal mouse model that develops breast cancer under the influence of DM2 is critical for cancer treatment strategy design/prevention studies.

Metformin is a biguanide and it improves insulin resistance by yet unclear mechanisms but may involve activation of AMPK, inhibition of respiratory chain complex 1 [40, 41] and activation of G6PDH [42]. Rosiglitazone is a thiazolidinedione which activates PPAR‐γ receptors to improve insulin resistance [43]. It also causes a significant redistribution of fat away from viscera and liver with a concomitant increase in insulin sensitivity. We investigated how metformin or rosiglitazone can improve the overall survival of our diabetic breast cancer mouse model. Our study showed that metformin causes Myc downregulation both transcriptionally and post‐transcriptionally. In terms of post‐transcriptional regulation, metformin enhanced ubiquitin‐mediated Myc degradation. While the detailed mechanistic regulation remains to be determined, Myc downregulation explains why PKM2 [44], a Myc transcriptional target [27], is also downregulated. Given that Myc is involved in cancer metabolic reprogramming, we then focused on the Myc‐PKM2 axis in metabolic flux. We used a hyperpolarized 13C pyruvate tracer to accurately measure the real time metabolic flux of pyruvate‐to‐lactate reaction by MRSI. The application of 13C‐pyruvate‐based MRSI can accurately visualize tumors and their difference between the tumors of MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db (metformin/ rosiglitazone treated) and vehicle treated mice, and the chemical fate of the hyperpolarized 13C pyruvate was monitored [45, 46]. Our data showed that metformin mediated Myc‐PKM2 axis change is reflected in reduced metabolic flux change. This advanced tumor imaging method is sensitive, safe, non‐invasive and non‐radioactive [47, 48], and is able to provide deep insight into glycolytic regulation during tumorigenesis in real time. We previously employed this technology to investigate the growth inhibitory role of 14‐3‐3 σ, a negative regulator of glycolysis, and thereby demonstrated the induction of 14‐3‐3 σ in diminishing pyruvate‐to‐lactate flux [27]. In conclusion, targeting the Myc‐PKM2 axis may be an alternative therapeutic strategy for cancer intervention in cancers with DM2.

The Warburg effect is an important factor in cancer cell metabolism [19, 49] and one of the hallmarks of cancer [10, 50]. Regardless of whether oxygen is present, cancer cells tend to undergo aerobic glycolysis and convert most glucose to lactate instead of moving into the tricarboxylic acid cycle. To confirm our in vivo observation, we isolated cancer cells from the primary tumor sites of MMTV‐ErbB2/Leprdb/db mice and monitored the effect of metformin. As a well‐known mitochondrial complex I inhibitor [17], metformin at clinically relevant concentration efficiently suppressed oxygen consumption in the cancer cells in a sea horse experiment, indicating that the mitochondrial respiratory chain reaction was repressed. At the same time, we observed that lactate production decreased after the cancer cells were treated with metformin, consistent with our MRSI finding in terms of metabolic flux change. It is conceivable that metformin reduces the activation of AKT and mTOR and causes Myc downregulation, which in turn affects multiple key components in the glycolytic pathway [51]. Indeed, we identified adipokines that were upregulated under diabetic conditions and found that adiponectin, FGF‐1, MCP‐1 and RAGE were significantly downregulated by anti‐insulin resistance treatments. These 4 adipokines may serve as, as yet unknown, cancer regulators in HER2+ breast cancer progression. This finding indicates that anti‐insulin resistance treatments at clinically relevant concentrations not only alter cancer cell metabolism but also render the microenvironment unfavorable for tumor progression in our diabetic HER2+ breast cancer mouse model.

Significantly, our retrospective cohort study on HER2+ breast cancer patients who were on metformin have significantly longer overall survival than those who were not metformin user, is consistent with the observation of a recent phase III clinical randomized trial ALTTO evaluating the combination of adjuvant trastuzumab (anti‐HER2 antibody)/lapatinib and metformin use [52, 53]. It shows that metformin use improves the prognosis of HER2+ breast cancer patients with DM2. Our animal experiments and retrospective cohort studies recapitulate some of these clinical managements, suggesting the usefulness of our animal model. In addition to metformin, we expect that a similar clinical trial using rosiglitazone will possibly achieve the similar clinical outcome.

In summary, our animal model enabled experimental DM2 recapitulation, functional assessment and mechanistic elucidation to show that DM2 facilitated ErbB2+ breast tumor growth by hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia, resulting in stabilizing Myc/increasing mTOR activity and instigating cancer metabolic reprogramming, such as ECAR, OCR and adipokine profile changes (Figure 7). Clearly, the observed effect of anti‐insulin resistance treatments in hindering metabolic reprogramming process plus downregulating systemic insulin levels and altering adipokine profiles in our studies is important for future rational cancer therapy. Thus, the results from this study may provide insights into new clinical management of HER2+ breast cancer patients with DM2 to improve survival of this subgroup of breast cancer patients. Our results established a mouse model to recapitulate HER2+ breast cancer in the presence of diabetic condition. DM2 increases the stabilization of Myc and elevates mTOR activity to establish metabolic reprogramming. Importantly, anti‐insulin treatment is effective in correcting these metabolic reprogramming processes. Future rational cancer therapy for HER2+ breast cancer patients with DM2 can be strategically designed for better treatment.

FIGURE 7.

Metformin antagonizes diabetic HER2+ breast cancer signaling in regulating metabolic reprogramming. The model shows the metformin's inhibitory effect on diabetic and HER2 signaling pathways in regulating metabolism to decelerate breast cancer growth.

DECLARATIONS

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

All mouse studies were carried out under a protocol approved by the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The retrospective study was conducted in an approved protocol by the Institutional Review Board of Sun Yat‐sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou, People's Republic of China.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

P.C.C. and R.Z. performed the experiments and supervised this study. P.C.C. and R.Z. performed and analyzed the animal experiments. P.C.C performed and designed the cell proliferation assay and biochemistry experiments. H.C.C performed the ubiquitination assay. P.C.C. performed and analyzed the OCR and ECAR measurement. Samples for pathological assays and multiplex assays were collected by P.C.C. and R.Z. and the experiments were performed and analyzed by P.C.C., R.Z., H.H.C., E.F.M., G.V.T., F.Z., L.P., J.L., Y.S., Y.W., and H.W.; J.A.B. coordinated the MRI acquisition metabolism project; S.C.Y. and M.H.L. designed the research project and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Not applicable.

Chou P‐C, Choi HH, Huang Y, et al. Impact of diabetes on promoting the growth of breast cancer. Cancer Commun. 2021;41:414–431. 10.1002/cac2.12147

Contributor Information

Ruiying Zhao, Email: Ruiying.zhao@uth.tmc.edu.

Sai‐Ching Jim Yeung, Email: syeung@mdanderson.org.

Mong‐Hong Lee, Email: limh33@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lipscombe LL, Goodwin PJ, Zinman B, McLaughlin JR, Hux JE. Diabetes mellitus and breast cancer: a retrospective population‐based cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;98(3):349‐56. 10.1007/s10549-006-9172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jiralerspong S, Kim ES, Dong W, Feng L, Hortobagyi GN, Giordano SH. Obesity, diabetes, and survival outcomes in a large cohort of early‐stage breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(10):2506‐14. 10.1093/annonc/mdt224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Peairs KS, Barone BB, Snyder CF, Yeh HC, Stein KB, Derr RL, et al. Diabetes mellitus and breast cancer outcomes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(1):40‐6. 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Erickson K, Patterson RE, Flatt SW, Natarajan L, Parker BA, Heath DD, et al. Clinically defined type 2 diabetes mellitus and prognosis in early‐stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(1):54‐60. 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schott S, Schneeweiss A, Sohn C. Breast cancer and diabetes mellitus. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2010;118(10):673‐7. 10.1055/s-0030-1254116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Srokowski TP, Fang S, Hortobagyi GN, Giordano SH. Impact of diabetes mellitus on complications and outcomes of adjuvant chemotherapy in older patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(13):2170‐6. 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.5935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wolf I, Sadetzki S, Catane R, Karasik A, Kaufman B. Diabetes mellitus and breast cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(2):103‐11. 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)01736-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Narayan KM, Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, Sorensen SW, Williamson DF. Lifetime risk for diabetes mellitus in the United States. JAMA. 2003;290(14):1884‐90. 10.1001/jama.290.14.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. He X, Esteva FJ, Ensor J, Hortobagyi GN, Lee MH, Yeung SC. Metformin and thiazolidinediones are associated with improved breast cancer‐specific survival of diabetic women with HER2+ breast cancer. Annals of oncology. 2012;23(7):1771‐80. 10.1093/annonc/mdr534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646‐74. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kroemer G, Pouyssegur J. Tumor cell metabolism: cancer's Achilles' heel. Cancer cell. 2008;13(6):472‐82. 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cairns RA, Harris IS, Mak TW. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(2):85‐95. 10.1038/nrc2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Koppenol WH, Bounds PL, Dang CV. Otto Warburg's contributions to current concepts of cancer metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(5):325‐37. 10.1038/nrc3038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schulze A, Harris AL. How cancer metabolism is tuned for proliferation and vulnerable to disruption. Nature. 2012;491(7424):364‐73. 10.1038/nature11706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shaw RJ, Lamia KA, Vasquez D, Koo SH, Bardeesy N, Depinho RA, et al. The kinase LKB1 mediates glucose homeostasis in liver and therapeutic effects of metformin. Science. 2005;310(5754):1642‐6. 10.1126/science.1120781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. El‐Mir MY, Nogueira V, Fontaine E, Averet N, Rigoulet M, Leverve X. Dimethylbiguanide inhibits cell respiration via an indirect effect targeted on the respiratory chain complex I. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275(1):223‐8. 10.1074/jbc.275.1.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Owen MR, Doran E, Halestrap AP. Evidence that metformin exerts its anti‐diabetic effects through inhibition of complex 1 of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Biochem J. 2000;348 Pt 3:607‐14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cao LQ, Chen XL, Wang Q, Huang XH, Zhen MC, Zhang LJ, et al. Upregulation of PTEN involved in rosiglitazone‐induced apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2007;28(6):879‐87. 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324(5930):1029‐33. 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. He XX, Tu SM, Lee MH, Yeung SJ. Thiazolidinediones and metformin associated with improved survival of diabetic prostate cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(12):2640‐5. 10.1093/annonc/mdr020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dezaki K, Hosoda H, Kakei M, Hashiguchi S, Watanabe M, Kangawa K, et al. Endogenous ghrelin in pancreatic islets restricts insulin release by attenuating Ca2+ signaling in beta‐cells: implication in the glycemic control in rodents. Diabetes. 2004;53(12):3142‐51. 10.2337/diabetes.53.12.3142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fuentes‐Mattei E, Velazquez‐Torres G, Phan L, Zhang F, Chou PC, Shin JH, et al. Effects of obesity on transcriptomic changes and cancer hallmarks in estrogen receptor‐positive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(7). 10.1093/jnci/dju158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Plante I, Stewart MK, Laird DW. Evaluation of mammary gland development and function in mouse models. Journal of Visualized Experiments : JoVE. 2011(53). 10.3791/2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhao R, Yeung SC, Chen J, Iwakuma T, Su CH, Chen B, et al. Subunit 6 of the COP9 signalosome promotes tumorigenesis in mice through stabilization of MDM2 and is upregulated in human cancers. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(3):851‐65. 10.1172/JCI44111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Choi HH, Zou S, Wu JL, Wang H, Phan L, Li K, et al. EGF Relays Signals to COP1 and Facilitates FOXO4 Degradation to Promote Tumorigenesis. Advanced science. 2020;7(20):2000681. 10.1002/advs.202000681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bankson JA, Walker CM, Ramirez MS, Stefan W, Fuentes D, Merritt ME, et al. Kinetic Modeling and Constrained Reconstruction of Hyperpolarized [1‐13C]‐Pyruvate Offers Improved Metabolic Imaging of Tumors. Cancer research. 2015;75(22):4708‐17. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Phan L, Chou PC, Velazquez‐Torres G, Samudio I, Parreno K, Huang Y, et al. The cell cycle regulator 14‐3‐3sigma opposes and reverses cancer metabolic reprogramming. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7530. 10.1038/ncomms8530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Laronga C, Yang HY, Neal C, Lee MH. Association of the cyclin‐dependent kinases and 14‐3‐3 sigma negatively regulates cell cycle progression. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(30):23106‐12. 10.1074/jbc.M905616199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li K, Wu JL, Qin B, Fan Z, Tang Q, Lu W, et al. ILF3 is a substrate of SPOP for regulating serine biosynthesis in colorectal cancer. Cell research. 2020;30(2):163‐78. 10.1038/s41422-019-0257-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen J, Shin JH, Zhao R, Phan L, Wang H, Xue Y, et al. CSN6 drives carcinogenesis by positively regulating Myc stability. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5384. 10.1038/ncomms6384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fang L, Lu W, Choi HH, Yeung SC, Tung JY, Hsiao CD, et al. ERK2‐Dependent Phosphorylation of CSN6 Is Critical in Colorectal Cancer Development. Cancer Cell. 2015;28(2):183‐97. 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gully CP, Velazquez‐Torres G, Shin JH, Fuentes‐Mattei E, Wang E, Carlock C, et al. Aurora B kinase phosphorylates and instigates degradation of p53. PNAS. 2012;109(24):E1513‐22. 10.1073/pnas.1110287109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Duggan C, Irwin ML, Xiao L, Henderson KD, Smith AW, Baumgartner RN, et al. Associations of insulin resistance and adiponectin with mortality in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(1):32‐9. 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.4473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gasser E, Moutos CP, Downes M, Evans RM. FGF1 ‐ a new weapon to control type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13(10):599‐609. 10.1038/nrendo.2017.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Perry RJ, Lee S, Ma L, Zhang D, Schlessinger J, Shulman GI. FGF1 and FGF19 reverse diabetes by suppression of the hypothalamic‐pituitary‐adrenal axis. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6980. 10.1038/ncomms7980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yoshimura T. The production of monocyte chemoattractant protein‐1 (MCP‐1)/CCL2 in tumor microenvironments. Cytokine. 2017;98:71‐8. 10.1016/j.cyto.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ahmad S, Khan H, Siddiqui Z, Khan MY, Rehman S, Shahab U, et al. AGEs, RAGEs and s‐RAGE; friend or foe for cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2018;49:44‐55. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cleary MP, Juneja SC, Phillips FC, Hu X, Grande JP, Maihle NJ. Leptin receptor‐deficient MMTV‐TGF‐alpha/Lepr(db)Lepr(db) female mice do not develop oncogene‐induced mammary tumors. Exp Biol Med. 2004;229(2):182‐93. 10.1177/153537020422900207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zheng Q, Dunlap SM, Zhu J, Downs‐Kelly E, Rich J, Hursting SD, et al. Leptin deficiency suppresses MMTV‐Wnt‐1 mammary tumor growth in obese mice and abrogates tumor initiating cell survival. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2011;18(4):491‐503. 10.1530/ERC-11-0102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Feng YH, Velazquez‐Torres G, Gully C, Chen J, Lee MH, Yeung SC. The impact of type 2 diabetes and antidiabetic drugs on cancer cell growth. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15(4):825‐36. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01083.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wheaton WW, Weinberg SE, Hamanaka RB, Soberanes S, Sullivan LB, Anso E, et al. Metformin inhibits mitochondrial complex I of cancer cells to reduce tumorigenesis. eLife. 2014;3:e02242. 10.7554/eLife.02242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Leverve XM, Guigas B, Detaille D, Batandier C, Koceir EA, Chauvin C, et al. Mitochondrial metabolism and type‐2 diabetes: a specific target of metformin. Diabetes Metab. 2003;29(4 Pt 2):6S88‐94. 10.1016/s1262-3636(03)72792-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fenner MH, Elstner E. Peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor‐gamma ligands for the treatment of breast cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;14(6):557‐68. 10.1517/13543784.14.6.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Warner SL, Carpenter KJ, Bearss DJ. Activators of PKM2 in cancer metabolism. Future Medicinal Chemistry. 2014;6(10):1167‐78. 10.4155/fmc.14.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Park I, Larson PE, Zierhut ML, Hu S, Bok R, Ozawa T, et al. Hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance metabolic imaging: application to brain tumors. Neuro‐oncol. 2010;12(2):133‐44. 10.1093/neuonc/nop043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tessem MB, Swanson MG, Keshari KR, Albers MJ, Joun D, Tabatabai ZL, et al. Evaluation of lactate and alanine as metabolic biomarkers of prostate cancer using 1H HR‐MAS spectroscopy of biopsy tissues. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60(3):510‐6. 10.1002/mrm.21694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hu S, Balakrishnan A, Bok RA, Anderton B, Larson PE, Nelson SJ, et al. 13C‐pyruvate imaging reveals alterations in glycolysis that precede c‐Myc‐induced tumor formation and regression. Cell Metab. 2011;14(1):131‐42. 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gallagher FA, Kettunen MI, Day SE, Hu DE, Karlsson M, Gisselsson A, et al. Detection of tumor glutamate metabolism in vivo using (13)C magnetic resonance spectroscopy and hyperpolarized [1‐(13)C]glutamate. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2011;66(1):18‐23. 10.1002/mrm.22851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123(3191):309‐14. 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yeung SJ, Pan J, Lee MH. Roles of p53, MYC and HIF‐1 in regulating glycolysis ‐ the seventh hallmark of cancer. Cellular and molecular life sciences. 2008;65(24):3981‐99. 10.1007/s00018-008-8224-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Miller DM, Thomas SD, Islam A, Muench D, Sedoris K. c‐Myc and cancer metabolism. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(20):5546‐53. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bradley CA. Diabetes: Metformin in breast cancer. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13(5):251. 10.1038/nrendo.2017.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sonnenblick A, Agbor‐Tarh D, Bradbury I, Di Cosimo S, Azim HA, Jr ., Fumagalli D, et al. Impact of Diabetes, Insulin, and Metformin Use on the Outcome of Patients With Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2‐Positive Primary Breast Cancer: Analysis From the ALTTO Phase III Randomized Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(13):1421‐9. 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.7722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.