Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Because intravenous (IV) recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) does not always lead to a good outcome in a considerable proportion of patients, combined IV rtPA and rescue endovascular therapy (ET) have been performed in several recent studies. However, rescue therapy after completion of IV rtPA often results in late ineffective recanalization. We examined the efficacy and safety of combined IV rtPA and simultaneous ET as primary rather than rescue therapy for hyperacute middle cerebral artery (MCA) occlusion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS: A total of 29 patients eligible for IV rtPA, who were diagnosed as having MCA (M1 or M2) occlusion within 3 hours of onset, underwent thrombolysis. In the combined group, patients were treated by IV rtPA (0.6 mg/kg for 60 minutes) and simultaneous ET (intra-arterial rtPA, mechanical thrombus disruption with microguidewire, and balloon angioplasty) initiated as soon as possible. In the IV group, patients were treated by IV rtPA only.

RESULTS: The improvement of the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score at 24 hours was 11 ± 4.8 in the combined group versus 5 ± 4.3 in the IV group (P < .001). In the combined group, successful recanalization was observed in 14 (88%) of 16 patients with no symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, and 10 (63%) of 16 patients had favorable outcomes (modified Rankin Scale [mRS] 0, 1) at 3 months.

CONCLUSIONS: Aggressive combined therapy with IV rtPA and simultaneous ET markedly improved the clinical outcome of hyperacute MCA occlusion without significant adverse effect. Additional randomized study is needed to confirm our results.

The principal goal in treating acute ischemic stroke is rapid recanalization of occluded arteries by thrombolysis. Patients transferred to a stroke center within 1 to 2 hours of onset might be fortunate in undergoing thrombolysis by intravenous (IV) recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA), the sole FDA-approved treatment for acute ischemic stroke within 3 hours of onset.1 However, particularly in major arterial occlusions, the rate of early recanalization with IV rtPA is low, approximately 10% of occluded internal carotid arteries and 30% of occluded proximal middle cerebral arteries (MCA).2,3 Accordingly, for more than two thirds of patients with major arterial occlusions, the benefit from IV rtPA is limited mainly because of unsuccessful early recanalization by IV rtPA only.

Endovascular therapy (ET) such as intra-arterial thrombolysis is reported to have higher recanalization rates than IV rtPA, though effectiveness is limited by delayed initiation of treatment and recanalization.4 On the basis of the concept of combining the advantages of IV (quick initiation) and intra-arterial approaches (higher recanalization rate and mechanical aids to recanalization), combination therapy with use of IV rtPA and ET has been demonstrated in several studies in which encouraging results have been reported.5-14 However, in most of the studies, additional ET was performed as a rescue therapy, after the ineffectiveness of 30- or 60-minute-IV rtPA was confirmed by MR imaging, transcranial Doppler, or angiography. Therefore, the initiation of ET was delayed by IV rtPA for 1 to 2 hours. To maximize the chances of a full neurologic recovery, occluded arteries should be recanalized as soon as possible.1,9,14 In this study, we examined the efficacy and safety of combined therapy with IV rtPA and simultaneous ET, not as a rescue therapy, for MCA occlusion within 3 hours of onset.

Materials and Methods

Patient Selection

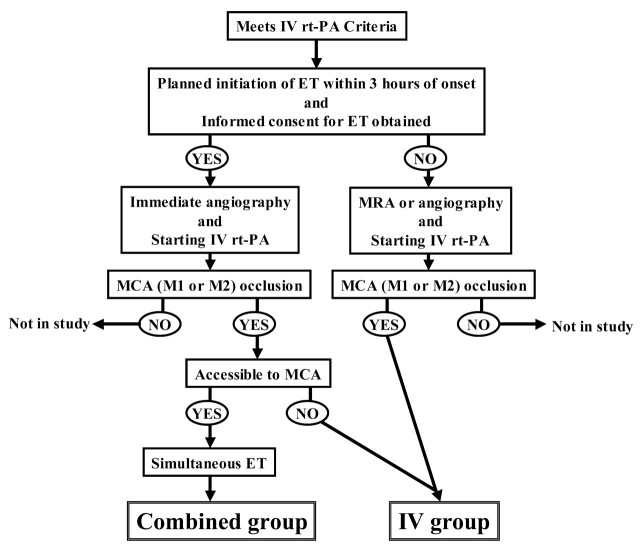

Between October 2005 and June 2006, we prospectively enrolled consecutive patients with acute ischemic stroke who were diagnosed as having acute occlusion of the MCA (M1 or M2) and who underwent thrombolysis within 3 hours of onset. Patients were treated by combined therapy when they met the inclusion criteria for combined therapy (combined group) and were treated with IV rtPA alone when they did not meet these criteria (IV group). The flowchart is shown in Fig 1. The protocol was approved by our institutional committee, and informed consent was obtained from the patients’ families.

Fig 1.

Flowchart of treatment protocol.

The inclusion criteria were 18 years of age or older, presenting within 3 hours after onset of new neurologic signs in the MCA distribution (hemiparesis, aphasia, unilateral spatial neglect, or conjugate deviation to the ischemic side), normal or slight early CT signs (less than one third of the MCA territory) on brain CT scans without evidence of hemorrhage, and MCA (M1 or M2) occlusion diagnosed by angiography or MR angiography. Additional inclusion criteria for combined therapy were planned initiation of ET within 3 hours of onset and obtaining informed consent for combined therapy.

The exclusion criteria corresponded to the Japanese guidelines for IV rtPA,15 based on those of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) rtPA trial1: seizure at onset; rapidly improving neurologic signs at any point before thrombolysis; active bleeding; a history of intracranial hemorrhage; a history of symptomatic ischemic stroke, cerebrospinal surgery, or head trauma within 90 days; a history of gastrointestinal or urinary tract bleeding within 21 days; a history of major surgery within 14 days; diagnosis of neoplasm, aneurysm, Moyamoya desease, or arteriovenous malformation; severe hepatic insufficiency; acute pancreatitis; uncontrolled hypertension defined by systolic blood pressure of more than 185 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure of more than 110 mm Hg despite bolus administration of antihypertensive drugs; baseline international normalized ratio of prothrombin time greater than 1.7; activated partial thromboplastin time more than 1.5 times normal; baseline platelet count less than 100,000/mm3; or glucose concentration of less than 2.7 mmol/L or more than 22.2 mmol/L.

Thrombolytic and Endovascular Therapy

When a patient was considered a candidate for thrombolysis as the result of head CT scan, edaravone, a free radical scavenger approved in Japan,16 was immediately administered. Patients meeting the inclusion criteria for combined therapy underwent immediate cerebral angiography. Just after a 6F sheath was placed into the femoral artery, IV rtPA (alteplase, 0.6 mg/kg, 60-mg maximum) was started, with a 10% loading bolus injection for 1 minute followed by continuous infusion for 60 minutes. The IV dose (0.6 mg/kg) was selected according to the dose in the previous combined study9 and the approved dose of IV rtPA for the Japanese population.15 When a thrombus was identified in the M1 or M2 portion of the MCA, ET was initiated immediately without discontinuing IV rtPA for 60 minutes. After the end-hole microcatheter (Renegade; Boston Scientific, Freemont, Calif) was passed over the microguidewire (Transend EX; Boston Scientific) through the occlusive thrombus, 2 mg of rtPA was manually injected for 2 minutes through the catheter beyond the thrombus. When the catheter was retracted into the thrombus, manual injection of rtPA was added directly into the thrombus as well as to the proximal site of the thrombus. We did not perform intra-arterial rtPA by constant infusion. If recanalization of the M1 portion was not achieved after several applications of intra-arterial rtPA and mechanical thrombus disruption with use of the microguidewire, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) was added. The PTA balloon (Gateway, 2 mm in diameter and 9 mm in length; Boston Scientific) was inflated for 30 or 60 seconds at 4 or 6 atm repeatedly until recanalization was obtained. When distal embolization was observed, intra-arterial rtPA was added. In all cases, the maximum dose of rtPA injected intra-arterially did not exceed 10 mg. ET was terminated if there was achievement of successful recanalization defined in the following section, extravasation of contrast suggesting vessel rupture, or 120 minutes of ET. In the case of patients showing vessel abnormality that made access to MCA difficult, or those who did not meet the inclusion criteria for combined therapy, only IV rtPA (0.6 mg/kg; the approved dose for the Japanese population) was performed in the same manner as for combined therapy. In general, additional anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy was initiated 24 hours after thrombolysis, respectively, for patients with cardioembolic or atherothrombotic stroke without intracranial hemorrhagic transformation/intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH).

Neuroradiologic Evaluation

Recanalization after ET was evaluated by Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) grade.17 In brief, the absence of recanalization was regarded as TIMI grade 0, minimal as grade 1, partial as grade 2, and complete as grade 3. Successful recanalization was defined as achieving TIMI 2 or 3 flow in all M1 and M2 segments.

Outcome Measures

Clinical assessments included the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) scores at baseline and at 24 hours, modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores and mortality at 3 months, the rate of successful recanalization at completion of ET, and symptomatic and asymptomatic ICH (including hemorrhagic infarction, parenchymal hematoma, and subarachnoid hemorrhage) during the first 36 hours after thrombolysis. Although some previous studies regarded mRS 0–2 as a favorable outcome, Higashida et al18 reported that for earlier recanalization studies at less than 3 hours “mRS 0, 1” might be a better outcome measure than “mRS 0–2.” As patients achieving earlier recanalization would be more likely to return to normal or near normal as measured by “mRS 0, 1,” we defined a favorable outcome as “mRS 0, 1.” Symptomatic ICH was defined as that accompanied by neurologic worsening.

Statistical Analysis

All values are expressed as mean ± SD. The Student t test, Fisher exact test, and Wilcoxon signed-rank test were used to analyze differences. A P value of less than .05 was considered significant.

Results

Demographic Data

A total of 29 patients with an age of 72 ± 9.7 years were enrolled. There were 16 patients who were treated with simultaneous combined therapy (combined group) and 13 with IV rtPA only (IV group). The baseline clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Most of the patients were diagnosed as having a cardioembolic stroke. The baseline NIHSS score was slightly higher in the combined compared with the IV group, but the difference did not reach significance (19 ± 2.2 vs 16 ± 5.0; P = .064). There was no significant difference between the 2 groups with regard to the interval from onset to the emergency department and initiation of IV rtPA (Table 2). In the combined group, sites of occlusion diagnosed by angiography were M1 proximal (n = 9), M1 distal (n = 5), and M2 (n = 2).

Table 1:

Baseline clinical characteristics*

| Combined (n = 16) | IV rtPA (n = 13) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, range) | 70 ± 8.8 (53–81) | 76 ± 10.2 (60–91) | .11 |

| Sex (male/female) | 11/5 | 6/7 | .27 |

| Baseline NIHSS score | 19 ± 2.2 | 16 ± 5.0 | .064 |

| Early CT sign | 4 (25%) | 4 (31%) | 1 |

| Lesion side (left/right) | 9/7 | 7/6 | 1 |

| Blood pressure: | |||

| Systolic (mm Hg) | 150 ± 20 | 153 ± 19 | .67 |

| Diastolic (mm Hg) | 83 ± 14 | 82 ± 13 | .86 |

| Blood glucose (mg/dL) | 136 ± 40 | 127 ± 31 | .51 |

| Stroke subtype: | |||

| Cardioembolic | 14 (87%) | 13 (100%) | |

| Atherothrombotic | 2 (13%) | 0 | |

| Lacunar/other | 0 | 0 | |

| Concomitant disease: | |||

| Hypertension | 9 (56%) | 6 (46%) | |

| Dyslipidemia | 3 (19%) | 2 (15%) | |

| Diabetes | 4 (25%) | 2 (15%) | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 13 (81%) | 10 (77%) | |

| Sick sinus syndrome | 0 | 1 (8%) | |

| Coronary heart disease | 2 (13%) | 1 (8%) | |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 1 (6%) | 0 | |

| Valvular heart disease | 1 (6%) | 3 (23%) |

Note:—IV indicates intravenous; rtPA, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

Data expressed as n (%) or mean ± SD.

Table 2:

Interval from onset to treatment*

| Combined (n = 16) | IV rtPA (n = 13) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset | |||

| To emergency department | 52 ± 12 | 47 ± 25 | .50 |

| To CT scan | 60 ± 13 | 57 ± 28 | .67 |

| To IV rtPA | 110 ± 22 | 118 ± 37 | .47 |

| To intra-arterial rtPA | 150 ± 25 | − | |

| To termination of thrombolysis | 213 ± 49 | 178 ± 37 | |

| Delay between IV and intra-arterial | 40 ± 15 | − |

Note:—IV indicates intravenous; rtPA, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator.

Plus-minus values are means ± SD (minutes).

Arterial Recanalization

The mean intervals from onset to intra-arterial rtPA and to termination of ET were 150 ± 25 and 213 ± 49 minutes, respectively (Table 2). The time lag between IV and intra-arterial rtPA was 40 ± 15 minutes, during which arterial occlusions persisted after the initiation of IV rtPA in all of the 16 patients. In the combined group, half of the patients were treated with PTA. The dose of intra-arterial rtPA was 6.3 ± 2.5 mg (range, 1–10 mg). At the end of ET, successful recanalization (TIMI 2, 3) was observed in 14 (88%), half of whom achieved TIMI 3 flow.

Clinical Outcome and Safety

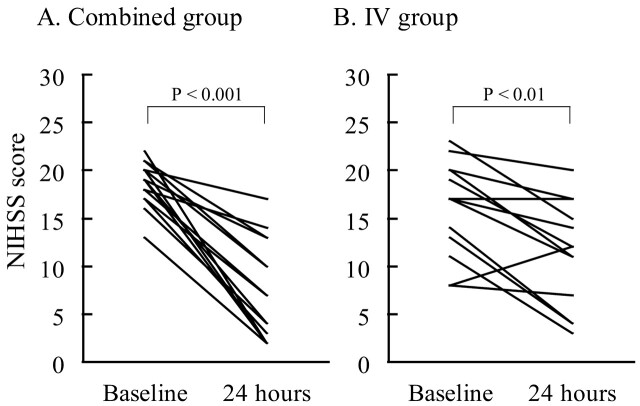

In both groups, significant neurologic improvement was observed at 24 hours (Fig 2). The improvement of NIHSS score at 24 hours was 11 ± 4.8 in the combined group versus 5 ± 4.3 in the IV group (P < .001). The proportion of patients showing favorable outcome (mRS 0, 1) at 3 months was 63% (10 patients) in the combined group versus 15% (2 patients) in the IV group (P < .05). There was no symptomatic ICH at 36 hours in the combined group and 1 in the IV group. There were no other hemorrhagic complications, such as groin or retroperitoneal hematoma, in either group. One patient in the combined group died of congestive heart failure 2.5 months after thrombolysis. Table 3 summarizes the clinical outcomes.

Fig 2.

NIHSS scores at baseline and at 24 hours. In the combined group (A), median scores were 19 and 7, respectively. In the IV group (B), median scores were 17 and 12, respectively.

Table 3:

Clinical outcomes*

| Combined (n = 16) | IV rtPA (n = 13) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Successful recanalization (TIMI 2,3) | 14 (88%) | – | |

| Improvement of NIHSS score (24 hours) | 11 ± 4.8 | 5 ± 4.3 | .0007 |

| Favorable outcome (mRS 0,1) (90 days) | 10 (63%) | 2 (15%) | .022 |

| Symptomatic ICH (36 hours) | 0 | 1 (8%) | |

| Asymptomatic ICH (36 hours) | 1 (6%) | 0 | |

| Mortality (90 days) | 1 (6%) | 0 |

Note:—IV indicates intravenous; rtPA, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction grade; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage.

Data expressed as n (%) or mean ± SD.

Discussion

Although the efficacy of IV rtPA within 3 hours and intra-arterial recombinant pro-urokinase (proUK) within 6 hours of onset was proved, thrombolysis does not always lead to good outcomes in a considerable proportion of patients.1,4 In the NINDS study, IV rtPA within 3 hours of onset significantly improved the clinical outcome compared with placebo. However, despite inclusion of patients with lacunar infarction with slight neurologic deficits, only 39% of the patients treated with IV rtPA had recovered without any symptoms or significant disability (mRS 0, 1) at 3 months, mainly because of a low recanalization rate of major arterial occlusions.1 In the Prolyse in Acute Cerebral Thromboembolism II trial, although 66% of the patients treated with intra-arterial proUK within 6 hours of onset had partial or complete recanalization of MCA occlusion, only 26% have recovered to the level of mRS 0, 1, mainly because of a delay in initiating treatment and achieving recanalization.4 Median time to initiation of intra-arterial proUK was 5.3 hours, and initiation within 3 hours was achieved in only 1 patient. At the time of recanalization, probably 6 to 8 hours after onset, extensive irreversible ischemic change in the brain tissue would have already occurred. As early recanalization within 5 hours of onset is a powerful predictor of favorable outcome in carotid territory ischemic stroke, the initiation of recanalization therapy within 3 hours is desirable.9,19-21 A retrospective study22 demonstrated that intra-arterial rtPA initiated within 3 hours of onset led to successful recanalization in 75% and mRS 0, 1 at 3 months in 50% of the patients with major arterial occlusions. There is a possibility that intra-arterial therapy is superior to IV therapy in cases of major arterial occlusions eligible for standard IV rtPA therapy.

Some pilot studies have demonstrated that the combination of IV rtPA and ET is feasible and safe.5-12 However, in most of the studies, additional intra-arterial therapy was performed as rescue therapy after the ineffectiveness of 30- or 60-minute IV thrombolysis was confirmed by MR imaging, transcranial Doppler, or angiography. Because our strategy is a combination of IV rtPA and intentional simultaneous ET as primary, not rescue, therapy, our study is essentially different from those performed previously. We thought that waiting until certifying whether recanalization by IV rtPA was successful or not might waste precious time for rescuing ischemic penumbra. Therefore, we initiated ET as soon as possible during IV rtPA with the aim of earlier recanalization within 5 hours after onset, a powerful predictor of good outcome in carotid territory ischemic stroke. As a result, the mean delay between IV and intra-arterial rtPA was 40 minutes and the mean time from onset to intra-arterial rtPA was 2.5 hours, which were both much shorter than those previously reported, approximately 1.5 to 2 hours and 3.5 to 5 hours, respectively (Table 4). In our combined group, favorable rates of successful early recanalization (88%) and mRS 0, 1 at 3 months (63%) were achieved. In previous studies of combined therapy, the rate of mRS 0, 1 was less than 50% (range, 25%–50%) for cases of MCA occlusion, despite quick initiation of IV rtPA within 2 to 2.5 hours of onset and a high recanalization (TIMI 2, 3) rate by rescue therapy (range, 50%–100%).5,6,9,10 This might be because recanalization by rescue ET was usually achieved more than 5 hours after onset.

Table 4:

Interval to treatment and clinical outcome compared with previous studies

| Treatment | Occlusion Site | No. Patients (Treated†/Enrolled) | Intervals (min) |

mRS 0, 1 (90 days) (%) | sICH (36 hours) (%) | Mortality (90 days) (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Onset to IV | Onset to ET | IV to ET | |||||||

| Current series | IV + IA (+ PTA) | M1, M2 | 16/29 | 110 | 150 | 40 | 63 | 0 | 6 |

| NINDS Part 2 (1995)1 | IV | us | 168 | 119 | − | − | 39 | 6.4 | 17 |

| PROACT II (1999)4 | IA | M1, M2 | 108/121 | − | 318 | − | 26 | 10 | 25 |

| Ernst et al (2000)6 | IV + rescue IA | I, M, A | 16/20 | 122 | 210 | 88 | 38‡ | 5 | 13‡ |

| IMS–I (2004)9 | IV + rescue IA | I, M, A, V, B | 62/80 | 136 | 217 | 81 | 29‡ | 6.3 | 14‡ |

| Lee et al (2004)10 | IV + rescue IA (+ abciximab IV) | I, M, P, B | 16/30 | 135 | (230*) | (95*) | 50‡ | 0 | 0‡ |

| Multi MERCI (2006)14 | IV + rescue thrombectomy (+ IA) | I, M, V, B | 30/111 | na | 216 | na | (33§) | 6.7 | 27 |

Note:—M indicates middle cerebral artery (MCA); M1, M1 segment of MCA; M2, M2 segment of MCA; I, internal carotid artery; A, anterior cerebral artery; P, posterior cerebral artery; V, vertebral artery; B, basilar artery; ET, endovascular therapy; sICH, symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage; us, unspecified; na, not available; PTA, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty; NINDS, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; PROACT, Prolyse in Acute Cerebral Thromboembolism; IMS, Interventional Management of Stroke; MERCI, Mechanical Embolus Removal in Cerebral Ischemia; IV, intravenous; IA, intra-arterial; mRS, modified Rankin Scale.

Interval to angiography.

No. of patients treated by combined therapy.

Percentage in cases of MCA (M1 or M2) occlusion treated with combined therapy.

Percentage of mRS 0–2.

Recently, the Interventional Management of Stroke (IMS) II study has demonstrated that the combination of IV rtPA and intended intra-arterial rtPA via the EKOS sonography-activated microinfusion catheter (EKOS, Bothell, Wash) was feasible and safe.23 In this study, intra-arterial rtPA was performed by constant infusion for up to 2 hours after initial single injection, not repeated manual injection, from the proximal portion of the thrombus. In addition, mechanical thrombus disruption with use of the EKOS catheter or PTA balloon was prohibited. The recanalization rate at 1 hour after initiation of intra-arterial rtPA via the EKOS catheter was less than 50% (45.5%) though 73% at the end of the procedure. Taking time from initiation of intra-arterial rtPA to recanalization may be why the rate of mRS 0, 1 was 33% in the IMS II study compared with 63% in our combined group.

With use of our strategy, it is possible that an unnecessary intra-arterial procedure may be performed on patients who would have improved by IV rtPA alone. However, in view of the low rate of early recanalization by IV rtPA,2,3 which was not evident in any patients in our combined group at 40 minutes after initiation of IV rtPA, as well as the risk for a poor outcome such as severe disability or death if early recanalization is not obtained, ET, which is relatively safe when performed by trained interventional neuroradiologists, might be beneficial to patients with major arterial occlusions. Because such expertise as intra-arterial thrombolysis is not always available in most community hospitals, clinical studies of ET as a rescue therapy after IV rtPA initiated in such hospitals are also very important.6,9,24 However, for patients with major arterial occlusions who are transferred to stroke centers within 1 to 2 hours after onset, more aggressive therapy such as combined IV rtPA and simultaneous ET initiated as soon as possible may lead to a better clinical outcome.

The great advantage of combined therapy compared with ET alone is that treatment can begin much more quickly. As the result of systemic administration of rtPA, which accelerates clot lysis, the thrombus may be dissolved and disrupted more rapidly and easily by ET. Lewandowski et al5 demonstrated that combined therapy provided a better recanalization rate than intra-arterial therapy alone. In addition, it is likely that IV rtPA promotes lysis of thrombus fragments that embolize into distal vessels.25 Furthermore, combined therapy may suppress reocclusion of recanalized vessels, which was observed in 34% of the patients with MCA occlusion treated by IV rtPA alone.26 In our study, there was no reocclusion accompanied by neurologic worsening after terminating combined therapy.

In thrombolytic therapy, one of the major concerns is ICH, with which several of the following factors were associated: severe neurologic deficits, increasing age, high glucose level, and prolonged time to recanalization.2,3,27-29 However, early recanalization and use of IV rtPA before ET are reported not to be risk factors for ICH.2,11,14,27 The reason why the rate of ICH in our combined group was lower, 0% for symptomatic and 6% (1 patient) for asymptomatic ICH, than that in the previous studies may be as follows: early recanalization was achieved within 5 hours of onset when the disruption of the blood-brain barrier was minimal, the restricted upper dose of intra-arterial rtPA was less than half the dose used in previous studies of combined therapy, early additional mechanical disruption by PTA balloon, and the use of free radical scavenger.

Because reperfusion to irreversible ischemic brain tissue with low residual cerebral blood flow (rCBF) often leads to ICH,29 measurement of rCBF is important in the selection of patients for thrombolysis. However, as the reversibility of ischemic brain is determined by the intensity and duration of ischemia,30 we thought that 2 to 3 hours after onset is within the therapeutic time window even if rCBF is as low as 10 to 20 mL/100 g/minute and that evaluation of rCBF is not always necessary during such a hyperacute phase. Considering the benefits of earlier recanalization, we consider that recanalizing occluded arteries without triage can be more beneficial than performing an additional imaging study, which can cause a significant time delay. Actually, there was no increase in the rate of ICH in our combined group without triage by rCBF. Although we always encounter clinical dilemmas regarding time-consuming versus time-saving procedures, imaging-guided triage may be truly needed for patients within 3 to 9 hours of stroke onset as reported previously.28

Our study had several limitations. The number of subjects was small and the control group was biased. The IV rtPA–only group simply represented patients excluded from combined therapy, and another control group treated by ET without IV rtPA would also be desirable to confirm these results. In the IV rtPA–only group, the rate of favorable outcome (15%) was much lower than that of rtPA–treated subjects in the NINDS study (39%).1 This might be because mean age and baseline NIHSS scores of our IV rtPA–only group were higher than those of rtPA–treated subjects in the NINDS study. However, as the outcome assessment was not blinded, it is possible that this affected the outcomes. Furthermore, combined therapy in our study was heterogeneous, including subjects treated with or without PTA. It is also possible that our results were influenced by the neuroprotective effect of free radical scavengers as reported previously.16,31 In addition, more studies are needed to determine which technique of ET is best and which thrombolytic agent is best. However, we consider it most important to recanalize the occluded arteries as soon as possible, regardless of treatment technique.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that simultaneous treatment with IV rtPA and ET started within 3 hours of onset markedly improved the clinical outcome for MCA occlusion without significant adverse effect. Although additional randomized studies are needed to confirm these results, aggressive combined therapy as the first choice of treatment may lead to a favorable clinical outcome for patients with hyperacute major arterial occlusion.

References

- 1.Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1581–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.del Zoppo GJ, Poeck K, Pessin MS, et al. Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator in acute thrombotic and embolic stroke. Ann Neurol 1992;32:78–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolpert SM, Bruckmann H, Greenlee R, et al. Neuroradiologic evaluation of patients with acute stroke treated with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator. The rt-PA Acute Stroke Study Group. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1993;14:3–13 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furlan A, Higashida R, Wechsler L, et al. Intra-arterial prourokinase for acute ischemic stroke. The PROACT II study: a randomized controlled trial. Prolyse in Acute Cerebral Thromboembolism. JAMA 1999;282:2003–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewandowski CA, Frankel M, Tomsick TA, et al. Combined intravenous and intra-arterial r-TPA versus intra-arterial therapy of acute ischemic stroke: Emergency Management of Stroke (EMS) Bridging Trial. Stroke 1999;30:2598–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ernst R, Pancioli A, Tomsick T, et al. Combined intravenous and intra-arterial recombinant tissue plasminogen activator in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2000;31:2552–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill MD, Barber PA, Demchuk AM, et al. Acute intravenous–intra-arterial revascularization therapy for severe ischemic stroke. Stroke 2002;33:279–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suarez JI, Zaidat OO, Sunshine JL, et al. Endovascular administration after intravenous infusion of thrombolytic agents for the treatment of patients with acute ischemic strokes. Neurosurgery 2002;50:251–59; discussion 259–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.IMS Study Investigators. Combined intravenous and intra-arterial recanalization for acute ischemic stroke: the Interventional Management of Stroke Study. Stroke 2004;35:904–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee KY, Kim DI, Kim SH, et al. Sequential combination of intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator and intra-arterial urokinase in acute ischemic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004;25:1470–75 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zaidat OO, Suarez JI, Sunshine JL, et al. Thrombolytic therapy of acute ischemic stroke: correlation of angiographic recanalization with clinical outcome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005;26:880–84 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sekoranja L, Loulidi J, Yilmaz H, et al. Intravenous versus combined (intravenous and intra-arterial) thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke: a transcranial color-coded duplex sonography–guided pilot study. Stroke 2006;37:1805–09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noser EA, Shaltoni HM, Hall CE, et al. Aggressive mechanical clot disruption: a safe adjunct to thrombolytic therapy in acute stroke? Stroke 2005;36:292–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith WS. Safety of mechanical thrombectomy and intravenous tissue plasminogen activator in acute ischemic stroke. Results of the multi Mechanical Embolus Removal in Cerebral Ischemia (MERCI) trial, part I. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006;27:1177–82 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamaguchi T, Mori E, Minematsu K, et al. Alteplase at 0.6 mg/kg for acute ischemic stroke within 3 hours of onset: Japan Alteplase Clinical trial (j-ACT). Stroke 2006;37:1810–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edaravone Acute Infarction Study Group. Effect of a novel free radical scavenger, edaravone (MCI-186), on acute brain infarction. Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study at multicenters. Cerebrovasc Dis 2003;15:222–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) trial. Phase I findings. TIMI Study Group. N Engl J Med 1985;312:932–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higashida RT, Furlan AJ, Roberts H, et al. Trial design and reporting standards for intra-arterial cerebral thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2003;34:e109–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sasaki O, Takeuchi S, Koike T, et al. Fibrinolytic therapy for acute embolic stroke: Intravenous, intracarotid, and intra-arterial local approaches. Neurosurgery 1995;36:246–52; discussion 252–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Labiche LA, Al-Senani F, Wojner AW, et al. Is the benefit of early recanalization sustained at 3 months? A prospective cohort study. Stroke 2003;34:695–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Molina CA, Alexandrov AV, Demchuk AM, et al. Improving the predictive accuracy of recanalization on stroke outcome in patients treated with tissue plasminogen activator. Stroke 2004;35:151–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bourekas EC, Slivka AP, Shah R, et al. Intraarterial thrombolytic therapy within 3 hours of the onset of stroke. Neurosurgery 2004;54:39–44; discussion 44–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Interventional Management of Stroke (IMS) II study. Stroke 2007;38:2127–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rymer MM, Thurtchley D, Summers D, et al. Expanded modes of tissue plasminogen activator delivery in a comprehensive stroke center increases regional acute stroke interventions. Stroke 2003;34:e58–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoneyama T, Nakano S, Kawano H, et al. Combined direct percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and low-dose native tissue plasminogen activator therapy for acute embolic middle cerebral artery trunk occlusion. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2002;23:277–81 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alexandrov AV, Grotta JC. Arterial reocclusion in stroke patients treated with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator. Neurology 2002;59:862–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kidwell CS, Saver JL, Carneado J, et al. Predictors of hemorrhagic transformation in patients receiving intra-arterial thrombolysis. Stroke 2002;33:717–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hacke W, Albers G, Al-Rawi Y, et al. The desmoteplase in acute ischemic stroke trial (DIAS): A phase II MRI-based 9-hour window acute stroke thrombolysis trial with intravenous desmoteplase. Stroke 2005;36:66–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta R, Yonas H, Gebel J, et al. Reduced pretreatment ipsilateral middle cerebral artery cerebral blood flow is predictive of symptomatic hemorrhage post-intra-arterial thrombolysis in patients with middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke 2006;37:2526–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones TH, Morawetz RB, Crowell RM, et al. Thresholds of focal cerebral ischemia in awake monkeys. J Neurosurg 1981;54:773–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lees KR, Zivin JA, Ashwood T, et al. Nxy-059 for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2006;354:588–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]