Abstract

SUMMARY: A 50-year-old woman presented with intermittent headache for the past few years. A paranasal sinus CT scan showed a diffusely calcified lesion at the roof of the sphenoid sinus and sella turcica, with the sellar floor bony cortex involved. Empty sella was noted. MR imaging revealed a soft-tissue lesion with low signal intensity on T1-weighted images, high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, and heterogeneous enhancement on postgadolinium images. Histologic examination revealed an osteoma composed of mature lamellar bone.

Osteoma is the most common bony tumor affecting the cranial meninges, and most frequently involves frontoethmoid areas.1 Patients with meningeal osteoma usually have no symptoms except they occasionally complain of neurologic ones relating to a mass effect due to tumor growth.2 Osteoma in the sphenoid sinus is extremely rare.3 An empty sella is defined as a sella that, regardless of its size and etiology, is completely or partly filled with CSF.4 Empty sella associated with tumor is seldom reported.5 Sphenoid sinus osteoma in the sella associated with empty sella, to our knowledge, has not been reported. We present such a case, a 50-year-old woman, with CT and MR imaging findings.

Case Report

A 50-year-old woman had intermittent headache for the past few years. She had hypertension and had received regular treatment for 5 years. However, elevated blood pressure in past few months was noted. Physical and neurologic examination revealed no abnormal findings. Results of a routine blood test were normal except for mild microcytic anemia.

Plain radiograph of the skull showed an enlarged pituitary fossa and a faint soft-tissue shadow in the sphenoid sinus. MR imaging (1.5T, Horizon LX; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wis) was performed and showed a soft-tissue lesion, measuring 0.8 × 1.7 × 1.9 cm, at the sella turcica floor and the roof of the sphenoid sinus. The pituitary gland was flattened, and the sella fossa was filled with CSF, suggesting empty sella. A postcontrast-enhanced study revealed good and homogeneous enhancement of the tumor. Our initial diagnosis was a pituitary adenoma invading the sellar floor and sphenoid sinus, associated with empty sella. Plain CT scanning (spiral CTi; GE Healthcare) of the paranasal sinus to rule out sinusitis was performed and showed diffuse calcification of the mass and empty sella. The bony cortex of the sellar floor was involved by the tumor (Fig 1A–E). Because of the diffuse calcification detected in the mass, skull base bone tumor in the sella was included in our differential diagnosis before surgery. Findings of hormone studies, including follicle-stimulating hormone, thyroid-stimulating hormone, adrenocorticotrophic hormone, prolactin, and growth hormone, were within normal limits.

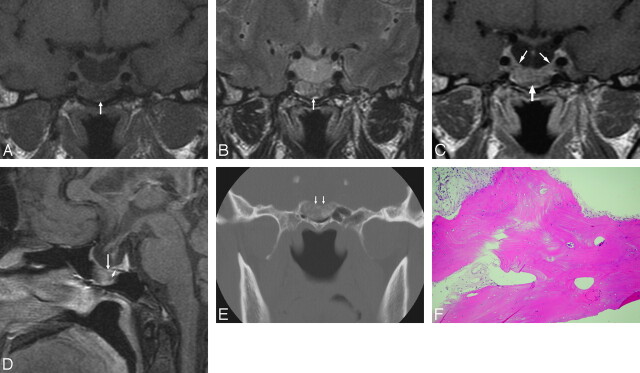

Fig 1.

A 50-year-old woman with a sphenoid sinus osteoma in the sella turcica associated with empty sella. A, Coronal T1-weighted (366.7/13.9 [TR/TE]) image of the sella shows a mass lesion (arrow) with low signal intensity, near the pituitary gland, at the sella turcica floor protruding into the sphenoid sinus. Note the associated empty sella. B, Coronal T2-weighted (3000/105 [TR/TE]) image at the same level shows a high-signal-intensity change of the mass (arrow). C, Postgadolinium coronal T1-weighted (750/9.6 [TR/TE]) image shows heterogeneous and moderate enhancement of the mass (arrow), similar to that of the adjacent normal pituitary gland (thin arrows). D, Postgadolinium sagittal T1-weighted (800/11.7 [TR/TE]) image shows a flattened pituitary gland and the sellar floor mass (arrow) protruding into the sphenoid sinus. The dark line of the sellar floor (arrowhead), indicating the intact bony cortex, cannot be detected between the pituitary gland and the tumor, comparing the adjacent sellar floor with intact bony cortex. E, Coronal CT scan of the sella with a bone window setting shows linear calcification within the sellar floor mass. The cortical line of the sella turcica floor (arrows) is involved. F, Photomicrograph of the specimen obtained from incisional biopsy. The tissue is made up of hyperplastic lamellar bone, compatible with osteoma (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×100).

Transphenoid excisional biopsy of the tumor was performed 9 days later. The tumor was hard in consistency and was removed piece by piece. Histologic examination revealed an osteoma composed of mature lamellar bone.

After surgery, the patient's condition was stable and the headache improved. One week later, follow-up CT scanning showed partial resection of the tumor in the sella turcica. The patient refused further treatment and had clinical follow-up for 6 months.

Discussion

Osteoma is not common in the skull base. Sekhar et al6 reported a surgical series of 49 tumors of the cranial base without mentioning osteoma. Derome and Visot7 reported 124 skull base tumors in the anterior fossa and ethmoid-sphenoid area, and only 3 cases were osteomas. Previous authors have reported that the frontoethmoidal region was the most common site of osteoma, followed by the ethmoidal and maxillary sinuses.8,9 Sphenoid sinus osteoma is extremely rare,3 and skull base osteomas are rarely symptomatic. Their most common clinical presentations are, in decreasing order, headache, invasion and deformity of the orbit, pneumocephalus with possible rhinorrhea and meningitis, and, rarely, abscess formation.1 In this case, a sphenoid sinus osteoma was located on the sellar floor with sella turcica cortex involvement. The tumor was initially diagnosed incorrectly as an invasive pituitary adenoma by its particular location and nonspecific signal-intensity change on MR imaging.

Awareness of primary bony tumors in the skull base may help in arriving at a correct diagnosis. Osteoma could be composed of cancellous bone or more commonly of cortical bone.1 It is an uncommon slow-growing tumor in the skull base and is commonly asymptomatic. Osteochondroma usually presents as a pedunculated mass, most commonly in the tongue, head, or neck. It is a tumor with admixtures of bone and cartilage. Osteosarcomas in the head and neck occur most frequently in the second and third decades of life. These tumors generally present as localized painless expanding masses and more often occur in the maxilla than in the mandible. Histologically, osteosarcoma gives a picture of a sarcomatous stroma giving rise to osteoid, and the stromal cells display varying degrees of anaplasia, with variable pleomorphism as well.10 Ossifying fibroma is a gradually expansile well-marginated fibro-osseous lesion most commonly seen in jaw bones. Cranial occurrence of this tumor is extremely rare but has been reported in the sella turcica.11 Ossifying fibroma contains a uniformly cellular fibrous spindle cell growth arranged in a whorled or matted pattern with varying degrees of lamellar bone formation in various stages of maturation. Capsule formation is an important feature to differentiate this from fibrous dysplasia and reactive bone formation.

In the present case, enlargement of the sella turcica on plain film was actually caused by the empty sella, not by the tumor. An empty sella is seldom associated with a tumor. Only a few cases of pituitary adenoma associated with empty sella have been reported before.5 The invasive character of pituitary adenomas might effect the destruction of the sellar floor, and then the tumor grows into the sphenoid sinus through the bone defect.5 A pre-existing empty sella having downward intrasellar pressure leads the tumor growing toward a relatively nonresistant extrasellar area.5 We believe that the osteoma of our patient arose from the sellar floor because of evidence of sellar cortex involvement, and it grew only downward into the sphenoid sinus because of the same downward intrasellar pressure of empty sella that has been reported previously.

Plain x-rays can help in the diagnosis of osteoma in the paranasal sinus.7 CT is important for characterizing and determining the extent of the tumor.2 Osteoma is exhibited as a well-defined high-attenuation mass, with attenuation values similar to those of the normal bone.2 MR imaging can be helpful for detecting adjacent dural or soft-tissue involvement. Tumor compression of surrounding tissues can be well delineated on 3 orthogonal images and, therefore, provides a good evaluation of the skull base, including the sellar area.

In this case, the osteoma was not radiopaque enough to be detected on plain films. Its rare location and nonspecific signal-intensity change on MR imaging led to an incorrect diagnosis. We suggest a combination of MR imaging and coronal CT for patients with suspected pituitary gland tumor with adjacent bone invasion, to rule out the possibility of a skull base bone tumor, such as osteoma.

References

- 1.Haddad FS, Haddad GF, Zaatari G. Cranial osteomas: their classification and management—report on a giant osteoma and review of the literature. Surg Neurol 1997;48:143–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maiuri F, Iaconetta G, Giamundo A, et al. Fronto-ethmoidal and orbital osteomas with intracranial extension: report of two cases. J Neurosurg Sci 1996;40:65–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strek P, Zagoliski O, Wywial A, et al. Osteoma or the sphenoid sinus. B-ENT 2005;1:39–41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bjerre P. The empty sella. Acta Neurol Scand 1990;82:1–25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hori E, Akai T, Kurimoto M, et al. Growth hormone-secreting pituitary adenoma confined to the sphenoid sinus associated with a normal-sized empty sella. J Clin Neurosci 2002;9:196–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sekhar LM, Nanda A, Sen CN, et al. The extended frontal approach to tumors of the anterior, middle, and posterior skull base. J Neurosurg 1992;76:198–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Derome PJ, Visot A. Osseous lesions of the anterior and middle base. In: Sekhar LN, Janecka IP, eds. Surgery of the Cranial Base Tumors. New York: Raven Press;1993. :809–17

- 8.Kosary IZ, Schacked I, Farine I. Use of surgical laser in the removal of an osteoma of the skull. Surg Neurol 1977;8:151–53 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corriero G, Maiuri F, Giamundo A, et al. Giant osteoma of the cranial vault with acromegaly and hydrocephalus: a case report. J Neurosurg Sci 1985;29:331–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rice DH, Batsakis JG. Dental and bone. In: Rice DH, Batsakis JG, eds. Surgical Pathology of the Head and Neck. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2000. :116–19

- 11.Sharma V, Newton G. Ossifying fibroma of the sella turcica. J Korean Med Sci 1992;7:58–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]