Abstract

Dynamic RNA modifications have been a burgeoning area in the last decade since the concept of “RNA epigenetics” was proposed [1]. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most abundant mRNA modification in eukaryotic cells. It can be installed by “writers”, removed by “erasers”, recognized by “readers”, and dynamically regulate the fate of methylated RNA. Until recently, the roles of reversible RNA methylation in chromatin and transcriptional regulation were not adequately studied. We discuss the new discoveries and insights into the chromatin and transcriptional regulation by m6A through two pathways: i) effects of m6A on mRNAs encoding histone modifiers and transcriptional factors; ii) m6A regulation of chromatin-associated regulatory RNAs. Additionally, we provide an outlook on how the transcriptional regulation by RNA m6A could add an additional critical layer to transcriptional regulation.

N6-methyladenosine (m6A)

m6A is the most prevalent and well-characterized internal mRNA modification in higher eukaryotes [2]. Besides mRNA, m6A has been shown to widely exist in ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs), small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs) [3••].

“Writers”, “erasers”, and “readers”, which respectively deposit, remove, and recognize the m6A on RNA, are collectively known as m6A effectors [3••]. A large portion of mRNA m6A is installed co-transcriptionally by a methyltransferase complex (MTC) composed of the core methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3) and methyltransferase-like 14 (METTL14) [4–6]. MTC is associated with additional subunits, including Wilms tumor 1-associating protein (WTAP) [4], Vir like m6A methyltransferase associated (VIRMA) [7], zinc finger CCCH-type containing 13 (ZC3H13) [8], and RNA binding motif protein 15/15B (RBM15/15B) [9]. More recently, methyltransferase-like 16 (METTL16) [10,11], methyltransferase-like 5 (METTL5) [12], and Zinc finger CCHC-type-containing 4 (ZCCHC4) [13] have been identified as m6A methyltransferases that can install internal m6A on RNA species possessing certain structures, such as small nucleolar RNAs, pre-mRNAs, and rRNA. Fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) [14,15] and AlkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5) [16] are the only two known demethylases that can actively remove the m6A on RNA.

m6A can be preferentially “read” via three mechanisms: i) m6A directly recruits readers such as the YTH domain family proteins and the associated regulatory machinery [17–19]; ii) m6A repels certain RNA binding proteins (RBPs) that prefer unmodified A over m6A [20]; iii) m6A changes the secondary structures to alter protein-RNA interactions [21]. Numerous m6A readers have been reported that include YTHDF1–3 [18,19,22], YTHDC1–2 [23–26], insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding proteins (IGF2BPs) [27], heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (HNRNPs) [21,28–30], Fragile X mental retardation 1 (FMR1) [31,32], and proline rich coiled-coil 2A (Prrc2a) [33]. The list of potential m6A readers is still growing.

In parallel to the well-known reversible epigenetic modifications of histone and DNA, studies have demonstrated the dynamic regulatory roles of m6A on mRNA in response to development signaling and environmental stimulation and stresses. m6A impacts the fate of modified RNA in many aspects, including pre-mRNA processing, nuclear export, stability, translation, and RNA-protein granule formation [3••], thereby leading to profound impacts on mammalian development and human diseases [34,35••]. m6A on mRNA is enriched around the stop codon and in 3’ UTRs; functions of these m6A marks on mRNA can be context-dependent (see review [3••]). For instance, 5’ UTR m6A is linked to cap-independent translation; while 3’ UTR m6A can mediate cap-dependent translation. As for m6A readers, IGF2BPs can bind to m6A at both CDS region and 3’ UTR; whereas YTHDF2 and YTHDF1 preferentially bind m6A at CDS and 3’ UTR, respectively. A systematic profiling of the binding sites of m6A effectors and the altered m6A sites by each effector can help understand the mRNA region-specific m6A function and regulation. Site-specific m6A modulation could further establish functional importance of the specific m6A sites on mRNA [36].

The functional studies during the past decade mainly focused on how m6A plays regulatory roles in gene expression at the post-transcriptional level. However, there have been emerging studies in recent years which also revealed critical roles of RNA m6A methylation on chromatin regulation. RNA m6A can modulate transcription and chromatin state (Figure 1). The currently known pathways are: i) mRNA m6A impacts translation and stability of the methylated transcripts that encode histone modifiers, transcriptional factors, or key proteins in transcription regulation; ii) m6A directly regulates the cellular fate of critical nuclear RNAs, especially chromatin-associated regulatory RNAs (carRNAs). In this review, we summarize these recent advances in our understanding of how m6A functions in transcriptional regulation, highlight the novel mechanisms by which m6A affects transcription and chromatin structure, and the key questions that remain to be investigated in the future.

Figure 1.

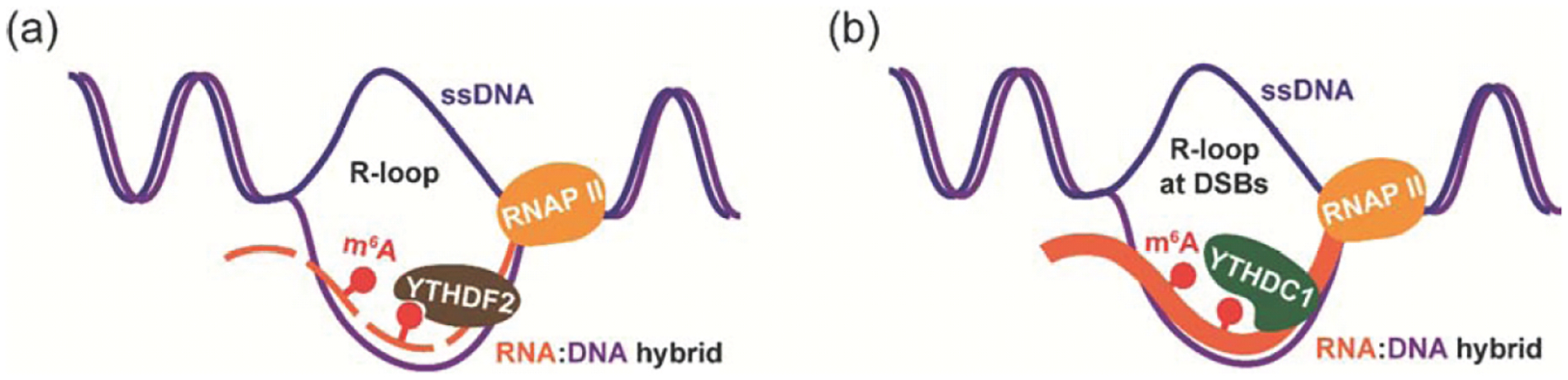

Divergent roles of RNA m6A in R-loop formation under different cellular contexts. (a) RNA m6A in RNA:DNA hybrids may be recognized by the reader YTHDF2, which facilitates the degradation of RNA in RNA:DNA hybrids and subsequently destabilizes RNA:DNA hybrids in hPSCs cells. (b) At DSBs, YTHDC1 is recruited to RNA m6A sites to protect the methylated RNA, leading to the accumulation of RNA:DNA hybrids in U2OS cells.

Transcriptional regulation by mRNA m6A

m6A can be deposited on mRNAs encoding histone modifiers and transcription factors to affect transcription regulation. In mouse embryonic neural stem cells (NSCs), Mettl14 knockout leads to genome-wide changes in specific histone modifications in an m6A-dependent manner. CBP and p300 transcripts, which encode acetyltransferases for the active transcription mark H3K27Ac are m6A methylated. Upon loss of m6A, these transcripts are stabilized and lead to increased H3K27Ac, which is associated with decreased proliferation and premature differentiation of NSCs [37•]. Likewise, in adult neural stem cells (aNSCs), METTL3 knockdown leads to reduced levels of both m6A and expression of EZH2 mRNA. EZH2 is a functional enzymatic component catalyzing the methylation of the repressive histone mark H3K27Me3. Overexpression of EZH2 could rescue the defects of neurogenesis and neuronal development induced by loss of Mettl3 [38]. In bacteria-induced inflammatory response, mRNA of KDM6B has been shown to be m6A-modified and undergo YTHDF2-mediated degradation. Loss of YTHDF2 stabilizes the KDM6B transcript to induce H3K27Me3 demethylation of proinflammatory cytokines thereby enhancing their transcription [39]. All three cases indicate mRNA m6A could further modulate gene expression through transcriptional regulation by histone modifications.

In acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) cells, METTL3 can associate with chromatin and localize to the transcriptional start site (TSS) of active genes. Promoter-bound METTL3 deposits m6A in the coding region of the associated mRNA to promote its translation. The transcripts encoding transcription factors SP1 and SP2 are two key substrates of METTL3. METTL3 depletion leads to significantly reduced protein expression of SP1 and SP2, indicating a potential activating role of mRNA m6A in SP1- and SP2-dependent transcription [40•]. In addition, in certain cancer cells, the m6A reader IGF2BP1 could increase the transcription factor SRF abundance by stabilizing its 3’UTR m6A, thereby promoting SRF-dependent transcriptional activity [41].

mRNA m6A has also been shown to play important roles in circadian rhythm maintenance [42] and cell cycle regulation [43]. Considering circadian rhythm could involve a negative feedback loop on gene expression through transcription repression [44], and cell cycle regulation is closely connected to histone mRNA metabolism, DNA replication, and transcription [45,46], one can speculate that m6A on mRNAs that encode clock proteins and cell cycle markers could also indirectly regulate transcription and result in prolonged effects.

Transcriptional regulation by m6A on Pre-mRNA

It is not surprising that many mRNAs encoding key proteins in transcriptional regulation are m6A methylated, therefore m6A could affect transcription through tuning the levels of these proteins. In addition to the transcriptional regulation of the m6A on mature mRNA at the post-transcriptional level, m6A can also modulate transcription at the pre-mRNA stage.

m6A has been shown to affect the stability of R-loops, which affects transcription initiation, elongation, and termination. In human pluripotent stem cells, the presence of m6A is found on the RNA moiety in the formation of most RNA:DNA hybrids. In human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), the reader protein YTHDF2 can be recruited to these m6A sites where it subsequently facilitates the degradation of RNA:DNA hybrids. METTL3 depletion leads to the accumulation of m6A-methylated R-loops and elevated DNA double-strand breaks, implying a critical role for m6A processing in safeguarding genomic stability (Figure 1a) [47•]. In Hela cells, m6A has been shown to exist in a subset of R-loops. Instead of accelerating the removal of R-loops, m6A promotes R-loop formation to facilitate transcription termination. Therefore, METTL3 modulates transcription termination through m6A methylation of RNA involved in R-loop formation [48]. More recently, a study of DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair provided evidence that RNA m6A leads to the accumulation of RNA:DNA hybrids. In human sarcoma U2OS cells, methylated RNA by METTL3 is enriched at DSBs, which could be recognized and protected by YTHDC1. The accumulation of RNA:DNA hybrids at DSBs induced by the METTL3-m6A-YTHDC1 axis could further facilitate homologous recombination (HR)-mediated DSB repair (Figure 1b) [49•].

Emerging evidence suggests a connection between m6A and the transcriptional process [40,50–53], which is supported by the genetic analyses of m6A quantitative trait loci (QTLs) [54••]. m6A deposition has been shown to be affected by the progression rate of RNA polymerase II (RNAP II) [51], and m6A has also been proposed to regulate the occupancy and promoter-proximal pausing of RNAP II. m6A sites in pre-mRNA could promote the binding of an m6A reader hnRNPG to modulate RNAP II occupancy thereby affecting alternative splicing likely through RNAP II pausing [55•]. In Drosophila, MTC interacts with chromatin and binds to promoters to aid the release of RNAP II from the paused state. Knockdown of METTL3 or METTL14 hinders transcriptional elongation, while tethering METTL3 to a heterologous gene promoter is sufficient to increase RNAP II pause release, which reveals positive feedback of m6A on the transcription machinery [56]. It is known that METTL14 of MCT can recognize H3K36Me3, which co-transcriptionally facilitates the deposition of m6A on mRNA [53]. The model of the co-transcriptional interplay between m6A and histone modifications also reveals the transcriptional induction role of RNA m6A. m6A could co-transcriptionally direct KDM3B by the reader YTHDC1 to target chromatin to demethylate H3K9Me2. Since H3K9me2 generally leads to gene repression, the existence of RNA m6A promotes the demethylation of H3K9me2 and consequently promotes the overall transcriptional activity in gene bodies [57].

The m6A methylation on pre-mRNA can be reversible and may play roles in transcription and pre-mRNA processing as well as nuclear decay of certain RNA species to affect transcription outcome. A recent study also showed that the stability of DNA:RNA hybrid structures could be regulated by METTL8-mediated RNA 3-methylcytosine (m3C) methylation [58].

Transcriptional regulation by m6A on carRNAs

Phenotypes of cytoplasmic m6A reader knockout mice may not fully recapitulate the severe phenotypes of the writer KO mice in many development processes. These observations suggest critical nuclear regulation events mediated through RNA m6A methylation. Our research revealed that in mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) the knockout of the writer or a nuclear m6A reader led to substantial changes in the chromatin accessibility. We further found that carRNAs, including promoter-associated RNAs (paRNAs), enhancer RNAs (eRNAs), and repeat RNAs, undergo m6A methylation which regulates their levels and downstream transcription (Figure 2a) [59••].

Figure 2.

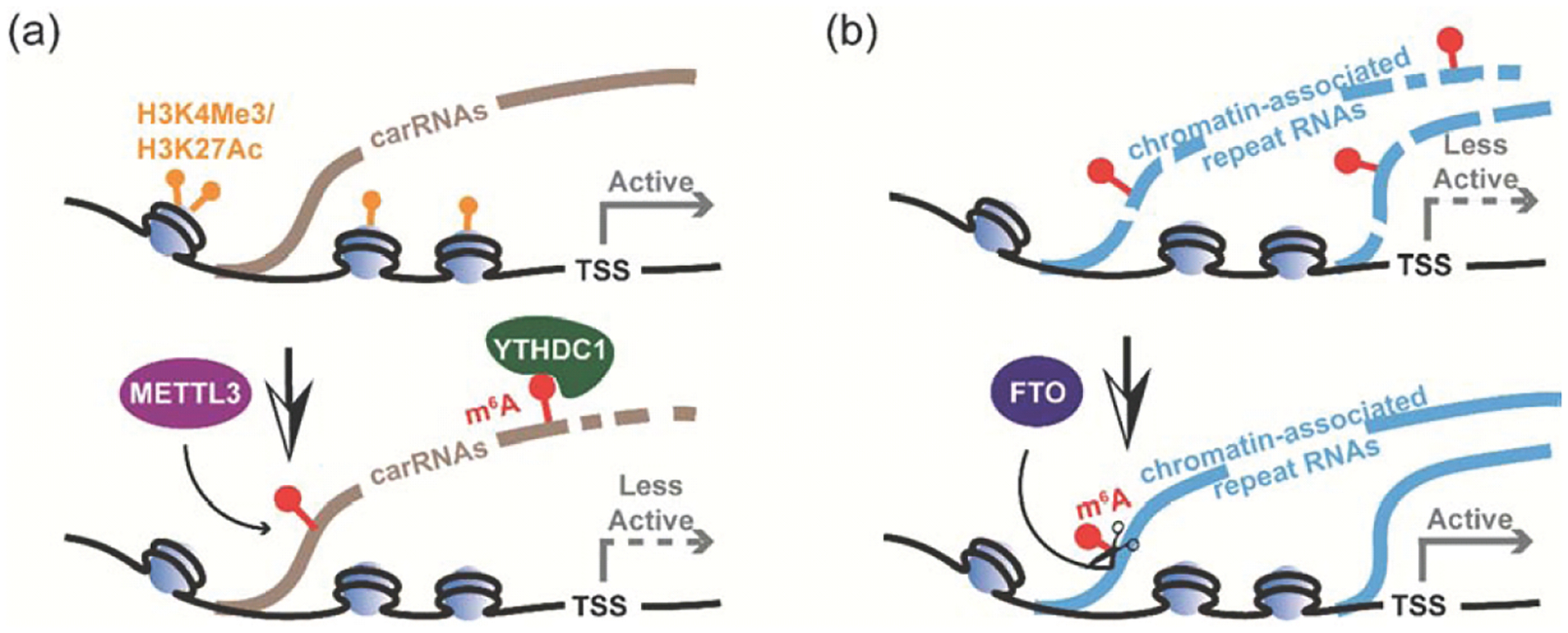

m6A destabilizes carRNAs and suppresses transcription. (a) m6A on carRNAs can be deposited by METTL3. At least a subset of m6A sites can be recognized by YTHDC1, resulting in the recruitment of the NEXT complex to promote the degradation of the methylated carRNAs, which ultimately leads to less active transcription. (b) FTO can demethylate m6A within repeat RNAs, especially LINE1 RNA, thereby affecting their abundance. Loss of FTO leads to more closed chromatin and reduced transcriptional activity in mESCs and mouse tissues.

In mESCs, knockout of Mettl3 or Ythdc1 increases global chromatin accessibility and activates nascent transcription. A portion of m6A on carRNAs is installed by METTL3 and negatively correlates with carRNA expression. YTHDC1 recognizes and recruits the nuclear exosome targeting (NEXT) complex to some of these m6A sites, which ultimately facilitates the degradation of at least a subset of methylated carRNAs, in particular repeat RNAs such as LINE1 RNA. Upon METTL3 depletion, m6A-methylated carRNAs display reduced m6A levels and increased abundance. Meanwhile, the downstream genes of these methylated carRNAs exhibit elevated transcription rates. Moreover, loss of m6A on carRNAs leads to enrichment of active histone markers and open chromatin at carRNA loci. Both transcription and chromatin state regulation can be recapitulated by site-specific m6A demethylation on target carRNAs, further validating the necessity of the m6A-dependent regulation. Note that in mESCs and endometrial cancer cells this chromatin regulation through carRNA m6A methylation dominates; however, in other cancer cells the mRNA m6A methylation on transcripts encoding histone modifiers and transcriptional factors can dominate. Cell context is important when dissecting the exact regulatory pathways.

Reversible m6A methylation on repeat RNAs and caRNAs

FTO demethylates m6A on chromatin-associated RNAs (caRNA) that include pre-mRNA and carRNAs in mESCs [60••]. As the first RNA m6A demethylase, FTO has been shown to impact a range of biological processes. It plays vital roles during mammalian development; the Fto−/− mice display intriguing phenotypes, including a notable proportion of embryo and postnatal lethality as well as postnatal growth retardation [61–64]. However, the physiologically relevant substrate(s) of FTO which contribute to these phenotypes has not yet been identified.

Our recent study found that FTO demethylates m6A within repeat RNAs, especially LINE1 RNA, which affects their abundance and consequently regulates chromatin state in mESCs, mNSCs, and mouse tissues (Figure 2b). A time-course inhibition of FTO in mESCs further establishes the causal relationship between m6A demethylation on LINE1 RNA and chromatin state regulation. Moreover, the FTO-mediated m6A demethylation of LINE1 RNA plays important roles in regulating mESC differentiation and proliferation. The dysregulated differentiation and proliferation of mESCs caused by Fto KO can be recapitulated by knocking down of LINE1 RNA, and can be partially rescued in Fto KO cells by targeted delivery of dCAS13b-wtFTO to LINE1 RNA to mediate LINE1-specific m6A demethylation. Our further analysis reveals LINE1 RNA as a general substrate of FTO across normal mouse and human tissues, indicating LINE1 RNA demethylation is likely a prevalent process in mammals. Depletion of FTO leads to ovary and oocyte defects with a dramatic reduction of LINE1 RNA abundance in GV oocytes. In GV oocytes, Fto KO also leads to more closed chromatin, suggesting a critical role of this process during oocyte development as an in vivo model.

Reversible m6A on carRNAs serves as a switch that can globally tune chromatin state and directly modulate transcription of hundreds to thousands of genes in mESCs. The discovery of quite prevalent reversible carRNA methylation in transcriptional regulation adds another layer of chemical modifications on bio-macromolecules to chromatin regulation in addition to DNA and histone modifications. Reversible carRNA methylation may have broad implications in the development and normal function of mammalian tissues and in human diseases.

Concluding remarks

During a decade of the rapid growth of post-transcriptional gene regulation by reversible RNA modifications (in particular RNA m6A), extensive efforts have been made to profile the m6A methylome, identify the m6A effectors, and investigate biological functions of m6A particularly on mRNA. These studies reveal effects on transcription through modulating m6A on transcripts that encode regulatory proteins. Moving forward, studies of critical roles of m6A on carRNAs provide numerous opportunities for both basic studies of gene expression regulation as well as their potential involvement in human diseases.

There are still many questions that remain to be answered. We currently do not know all nuclear m6A effectors, how these effectors interact with transcriptional factors, chromatin remodelers, histone modifiers, and DNA methylation systems, and the pathways in which these effectors and RNA m6A methylation integrate into the transcriptional regulation network. There is very likely involvement of methyltransferases other than METTL3 and METTL14. METTL3 and METTL14 may have methylation independent roles as suggested previously [65,66]. They could function as transcription factors and may serve as scaffold proteins to establish certain chromatin conformation or chromatin states. There are clearly other proteins involved in the decay of m6A methylated eRNAs and paRNAs besides YTHDC1. While promoting decay of some carRNAs YTHDC1 also plays a role in other nuclear processes dependent on RNA m6A methylation. Its post-translational modification status could be a key factor in its biological function and this can be very much cell context-dependent. YTHDC1 is prone to granule formation and is known to form the YTH nuclear body [67]. YTHDC1 in the granule and outside of the granule may perform very different functions.

It is interesting that repeat RNAs are quite heavily methylated. One can speculate that the initial methylation is a way to control activation of retrotransposon RNAs, leading to their decay during evolution. Additional regulatory functions might have evolved later on. It is not known how reversible methylation on repeat RNAs affects development and normal tissue function in general? We also do not know how cellular signaling regulates carRNA methylation and its overall impacts on transcription. We have shown that different cellular contexts would lead to opposite outcomes and we do not currently know what determines the dominant effects and effectors. Lastly, do other RNA modifications also exist on carRNAs or RNA:DNA hybrids and contribute to transcriptional regulation?

The m6A methylation of nuclear RNA is involved in R-loop formation and DNA damage repair response. This could present therapeutic opportunity in cancer cells with a defect in the DNA damage response. Could tuning of carRNA methylation synergize with existing therapies that target epigenetic pathways? Lastly, could some of the RNA modification information be inheritable, either through maternal effector proteins or through inheritable chromatin state that was set up by nuclear RNA methylation? These are all intriguing questions in the future.

Highlights.

m6A on chromatin-associated regulatory RNAs (carRNAs) regulates chromatin state and transcription.

m6A on repeats RNA can be demethylated by FTO to affect transcription.

mRNA m6A regulates transcription by controlling transcripts encoding histone modifiers and transcriptional factors.

Pre-mRNA m6A affects transcriptional regulation through divergent co-transcriptional RNA processing.

Acknowledgments

C.H. receives support from NIH (HG008935 and ES030546). C.H. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. We apologize to colleagues whose work could not be cited due to space constraints.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

C.H. is a scientific founder and a scientific advisory board member of Accent Therapeutics. Inc. and a shareholder of Epican Genentech.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.He C: Grand challenge commentary: RNA epigenetics? Nat Chem Biol 2010, 6:863–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fu Y, Dominissini D, Rechavi G, He C: Gene expression regulation mediated through reversible m6A RNA methylation. Nat Rev Genet 2014, 15:293–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3••.Shi H, Wei J, He C: Where, When, and How: Context-Dependent Functions of RNA Methylation Writers, Readers, and Erasers. Mol Cell 2019, 74:640–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper summarizes the context-dependent roles of m6A-dependent RNA regulation.

- 4.Liu J, Yue Y, Han D, Wang X, Fu Y, Zhang L, Jia G, Yu M, Lu Z, Deng X, et al. : A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat Chem Biol 2014, 10:93–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang P, Doxtader KA, Nam Y: Structural Basis for Cooperative Function of Mettl3 and Mettl14 Methyltransferases. Mol Cell 2016, 63:306–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang X, Feng J, Xue Y, Guan Z, Zhang D, Liu Z, Gong Z, Wang Q, Huang J, Tang C, et al. : Structural basis of N6-adenosine methylation by the METTL3-METTL14 complex. Nature 2016, 534:575–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yue Y, Liu J, Cui X, Cao J, Luo G, Zhang Z, Cheng T, Gao M, Shu X, Ma H, et al. : VIRMA mediates preferential m6A mRNA methylation in 3’UTR and near stop codon and associates with alternative polyadenylation. Cell Discov 2018, 4:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wen J, Lv R, Ma H, Shen H, He C, Wang J, Jiao F, Liu H, Yang P, Tan L, et al. : Zc3h13 Regulates Nuclear RNA m6A Methylation and Mouse Embryonic Stem Cell Self-Renewal. Mol Cell 2018, 69:1028–1038 e1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patil DP, Chen CK, Pickering BF, Chow A, Jackson C, Guttman M, Jaffrey SR: m6A RNA methylation promotes XIST-mediated transcriptional repression. Nature 2016, 537:369–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendel M, Chen KM, Homolka D, Gos P, Pandey RR, McCarthy AA, Pillai RS: Methylation of Structured RNA by the m6A Writer METTL16 Is Essential for Mouse Embryonic Development. Mol Cell 2018, 71:986–1000 e1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pendleton KE, Chen B, Liu K, Hunter OV, Xie Y, Tu BP, Conrad NK: The U6 snRNA m6A Methyltransferase METTL16 Regulates SAM Synthetase Intron Retention. Cell 2017, 169:824–835 e814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Tran N, Ernst FGM, Hawley BR, Zorbas C, Ulryck N, Hackert P, Bohnsack KE, Bohnsack MT, Jaffrey SR, Graille M, et al. : The human 18S rRNA m6A methyltransferase METTL5 is stabilized by TRMT112. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47:7719–7733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma H, Wang X, Cai J, Dai Q, Natchiar SK, Lv R, Chen K, Lu Z, Chen H, Shi YG, et al. : N(6-)Methyladenosine methyltransferase ZCCHC4 mediates ribosomal RNA methylation. Nat Chem Biol 2019, 15:88–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei J, Liu F, Lu Z, Fei Q, Ai Y, He PC, Shi H, Cui X, Su R, Klungland A, et al. : Differential m6A, m6Am, and m1A Demethylation Mediated by FTO in the Cell Nucleus and Cytoplasm. Mol Cell 2018, 71:973–985 e975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jia G, Fu Y, Zhao X, Dai Q, Zheng G, Yang Y, Yi C, Lindahl T, Pan T, Yang YG, et al. : N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol 2011, 7:885–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng G, Dahl JA, Niu Y, Fedorcsak P, Huang CM, Li CJ, Vagbo CB, Shi Y, Wang WL, Song SH, et al. : ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell 2013, 49:18–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dominissini D, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Schwartz S, Salmon-Divon M, Ungar L, Osenberg S, Cesarkas K, Jacob-Hirsch J, Amariglio N, Kupiec M, et al. : Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature 2012, 485:201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X, Zhao BS, Roundtree IA, Lu Z, Han D, Ma H, Weng X, Chen K, Shi H, He C: N6-methyladenosine Modulates Messenger RNA Translation Efficiency. Cell 2015, 161:1388–1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Lu Z, Gomez A, Hon GC, Yue Y, Han D, Fu Y, Parisien M, Dai Q, Jia G, et al. : N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature 2014, 505:117–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edupuganti RR, Geiger S, Lindeboom RGH, Shi H, Hsu PJ, Lu Z, Wang SY, Baltissen MPA, Jansen P, Rossa M, et al. : N6-methyladenosine (m6A) recruits and repels proteins to regulate mRNA homeostasis. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2017, 24:870–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu N, Dai Q, Zheng G, He C, Parisien M, Pan T: N6-methyladenosine-dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA-protein interactions. Nature 2015, 518:560–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi H, Wang X, Lu Z, Zhao BS, Ma H, Hsu PJ, Liu C, He C: YTHDF3 facilitates translation and decay of N6-methyladenosine-modified RNA. Cell Res 2017, 27:315–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roundtree IA, Luo GZ, Zhang Z, Wang X, Zhou T, Cui Y, Sha J, Huang X, Guerrero L, Xie P, et al. : YTHDC1 mediates nuclear export of N6-methyladenosine methylated mRNAs. Elife 2017, 6:e31311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shima H, Matsumoto M, Ishigami Y, Ebina M, Muto A, Sato Y, Kumagai S, Ochiai K, Suzuki T, Igarashi K: S-Adenosylmethionine Synthesis Is Regulated by Selective N6-Adenosine Methylation and mRNA Degradation Involving METTL16 and YTHDC1. Cell Rep 2017, 21:3354–3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsu PJ, Zhu Y, Ma H, Guo Y, Shi X, Liu Y, Qi M, Lu Z, Shi H, Wang J, et al. : Ythdc2 is an N6-methyladenosine binding protein that regulates mammalian spermatogenesis. Cell Res 2017, 27:1115–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao W, Adhikari S, Dahal U, Chen YS, Hao YJ, Sun BF, Sun HY, Li A, Ping XL, Lai WY, et al. : Nuclear m6A Reader YTHDC1 Regulates mRNA Splicing. Mol Cell 2016, 61:507–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang H, Weng H, Sun W, Qin X, Shi H, Wu H, Zhao BS, Mesquita A, Liu C, Yuan CL, et al. : Recognition of RNA N6-methyladenosine by IGF2BP proteins enhances mRNA stability and translation. Nat Cell Biol 2018, 20:285–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alarcon CR, Goodarzi H, Lee H, Liu X, Tavazoie S, Tavazoie SF: HNRNPA2B1 Is a Mediator of m6A-Dependent Nuclear RNA Processing Events. Cell 2015, 162:1299–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu N, Zhou KI, Parisien M, Dai Q, Diatchenko L, Pan T: N6-methyladenosine alters RNA structure to regulate binding of a low-complexity protein. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, 45:6051–6063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu B, Su S, Patil DP, Liu H, Gan J, Jaffrey SR, Ma J: Molecular basis for the specific and multivariant recognitions of RNA substrates by human hnRNP A2/B1. Nat Commun 2018, 9:420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edens BM, Vissers C, Su J, Arumugam S, Xu Z, Shi H, Miller N, Rojas Ringeling F, Ming GL, He C, et al. : FMRP Modulates Neural Differentiation through m6A-Dependent mRNA Nuclear Export. Cell Rep 2019, 28:845–854 e845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang F, Kang Y, Wang M, Li Y, Xu T, Yang W, Song H, Wu H, Shu Q, Jin P: Fragile X mental retardation protein modulates the stability of its m6A-marked messenger RNA targets. Hum Mol Genet 2018, 27:3936–3950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu R, Li A, Sun B, Sun JG, Zhang J, Zhang T, Chen Y, Xiao Y, Gao Y, Zhang Q, et al. : A novel m6A reader Prrc2a controls oligodendroglial specification and myelination. Cell Res 2019, 29:23–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roundtree IA, Evans ME, Pan T, He C: Dynamic RNA Modifications in Gene Expression Regulation. Cell 2017, 169:1187–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35••.Frye M, Harada BT, Behm M, He C: RNA modifications modulate gene expression during development. Science 2018, 361:1346–1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper summarizes the impacts of dynamic RNA modifications on mammalian development and human diseases.

- 36.Wei J, He C: Site-specific m6A editing. Nat Chem Biol 2019, 15:848–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37•.Wang Y, Li Y, Yue M, Wang J, Kumar S, Wechsler-Reya RJ, Zhang Z, Ogawa Y, Kellis M, Duester G, et al. : N6-methyladenosine RNA modification regulates embryonic neural stem cell self-renewal through histone modifications. Nat Neurosci 2018, 21:195–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper reported the first case that mRNA m6A regulates the abundance of transcripts encoding histone modifiers and consequently affects the level of histone modifications.

- 38.Chen J, Zhang YC, Huang C, Shen H, Sun B, Cheng X, Zhang YJ, Yang YG, Shu Q, Yang Y, et al. : m6A Regulates Neurogenesis and Neuronal Development by Modulating Histone Methyltransferase Ezh2. Genom Proteom Bioinf 2019, 17:154–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu C, Chen W, He J, Jin S, Liu Y, Yi Y, Gao Z, Yang J, Yang J, Cui J, et al. : Interplay of m6A and H3K27 trimethylation restrains inflammation during bacterial infection. Sci Adv 2020, 6:eaba0647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40•.Barbieri I, Tzelepis K, Pandolfini L, Shi J, Millan-Zambrano G, Robson SC, Aspris D, Migliori V, Bannister AJ, Han N, et al. : Promoter-bound METTL3 maintains myeloid leukaemia by m6A-dependent translation control. Nature 2017, 552:126–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper reported METTL3 as a regulator of certain transcription factors through a chromatin-based pathway.

- 41.Muller S, Glass M, Singh AK, Haase J, Bley N, Fuchs T, Lederer M, Dahl A, Huang H, Chen J, et al. : IGF2BP1 promotes SRF-dependent transcription in cancer in a m6A- and miRNA-dependent manner. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47:375–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fustin JM, Doi M, Yamaguchi Y, Hida H, Nishimura S, Yoshida M, Isagawa T, Morioka MS, Kakeya H, Manabe I, et al. : RNA-methylation-dependent RNA processing controls the speed of the circadian clock. Cell 2013, 155:793–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoon KJ, Ringeling FR, Vissers C, Jacob F, Pokrass M, Jimenez-Cyrus D, Su Y, Kim NS, Zhu Y, Zheng L, et al. : Temporal Control of Mammalian Cortical Neurogenesis by m6A Methylation. Cell 2017, 171:877–889 e817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takahashi JS: Transcriptional architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Nat Rev Genet 2017, 18:164–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marzluff WF, Koreski KP: Birth and Death of Histone mRNAs. Trends Genet 2017, 33:745–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bertoli C, Skotheim JM, de Bruin RA: Control of cell cycle transcription during G1 and S phases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2013, 14:518–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47•.Abakir A, Giles TC, Cristini A, Foster JM, Dai N, Starczak M, Rubio-Roldan A, Li M, Eleftheriou M, Crutchley J, et al. : N6-methyladenosine regulates the stability of RNA:DNA hybrids in human cells. Nat Genet 2020, 52:48–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper reported how the METTL3-m6A-YTHDF2 axis facilitates the removal of RNA:DNA hybrids in hPSCs.

- 48.Yang X, Liu QL, Xu W, Zhang YC, Yang Y, Ju LF, Chen J, Chen YS, Li K, Ren J, et al. : m6A promotes R-loop formation to facilitate transcription termination. Cell Res 2019, 29:1035–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49•.Zhang C, Chen L, Peng D, Jiang A, He Y, Zeng Y, Xie C, Zhou H, Luo X, Liu H, et al. : METTL3 and N6-Methyladenosine Promote Homologous Recombination-Mediated Repair of DSBs by Modulating DNA-RNA Hybrid Accumulation. Mol Cell 2020, 79:425–442 e427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper reported how the METTL3-m6A-YTHDC1 axis induces the accumulation of the RNA:DNA hybrids at DSBs in U2OS cells.

- 50.Aguilo F, Zhang F, Sancho A, Fidalgo M, Di Cecilia S, Vashisht A, Lee DF, Chen CH, Rengasamy M, Andino B, et al. : Coordination of m6A mRNA Methylation and Gene Transcription by ZFP217 Regulates Pluripotency and Reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell 2015, 17:689–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Slobodin B, Han R, Calderone V, Vrielink J, Loayza-Puch F, Elkon R, Agami R: Transcription Impacts the Efficiency of mRNA Translation via Co-transcriptional N6-adenosine Methylation. Cell 2017, 169:326–337 e312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bertero A, Brown S, Madrigal P, Osnato A, Ortmann D, Yiangou L, Kadiwala J, Hubner NC, de Los Mozos IR, Sadee C, et al. : The SMAD2/3 interactome reveals that TGFbeta controls m6A mRNA methylation in pluripotency. Nature 2018, 555:256–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang H, Weng H, Zhou K, Wu T, Zhao BS, Sun M, Chen Z, Deng X, Xiao G, Auer F, et al. : Histone H3 trimethylation at lysine 36 guides m6A RNA modification co-transcriptionally. Nature 2019, 567:414–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54••.Zhang Z, Luo K, Zou Z, Qiu M, Tian J, Sieh L, Shi H, Zou Y, Wang G, Morrison J, et al. : Genetic analyses support the contribution of mRNA N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification to human disease heritability. Nat Genet 2020, 52:939–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper provided a unique view of the connection between RNA m6A and the trancriptional processing through the genetic analyses of m6A QTLs.

- 55•.Zhou KI, Shi H, Lyu R, Wylder AC, Matuszek Z, Pan JN, He C, Parisien M, Pan T: Regulation of Co-transcriptional Pre-mRNA Splicing by m6A through the Low-Complexity Protein hnRNPG. Mol Cell 2019, 76:70–81 e79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper reported the first case that m6A on pre-mRNA can modulate RNAP II occupancy and alternative splicing.

- 56.Akhtar J, Renaud Y, Albrecht S, Ghavi-Helm Y, Roignant J-Y, Silies M, Junion G: m6A RNA methylation regulates promoter proximal pausing of RNA Polymerase II. bioRxiv 2020: 03.05.978163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li Y, Xia L, Tan K, Ye X, Zuo Z, Li M, Xiao R, Wang Z, Liu X, Deng M, et al. : N6-Methyladenosine co-transcriptionally directs the demethylation of histone H3K9me2. Nat Genet 2020, 52:870–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang L-H, Zhang X-Y, Hu T, Chen X-Y, Li J-J, Raida M, Sun N, Luo Y, Gao X: The SUMOylated METTL8 Induces R-loop and Tumorigenesis via m3C. iScience 2020, 23:100968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59••.Liu J, Dou X, Chen C, Chen C, Liu C, Xu MM, Zhao S, Shen B, Gao Y, Han D, et al. : N (6)-methyladenosine of chromosome-associated regulatory RNA regulates chromatin state and transcription. Science 2020, 367:580–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper reported the first case that m6A on carRNAs can globally tune chromatin state and transcription.

- 60••.Wei J, Yu X, Yang L, Cui X-L, Liu J, Gao B, He PC, Zhang L-S, Liu X, Chen J, et al. : FTO mediates LINE1 m6A demethylation and chromatin regulation in mESCs and mouse tissues. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper reported the first case of chromatin state and transcriptional regulation by m6A demethylation on repeat RNAs and LINE1 RNA in mESCs, mammalian tissues, and during development.

- 61.van der Hoeven F, Schimmang T, Volkmann A, Mattei MG, Kyewski B, Ruther U: Programmed cell death is affected in the novel mouse mutant Fused toes (Ft). Development 1994, 120:2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gao X, Shin YH, Li M, Wang F, Tong Q, Zhang P: The fat mass and obesity associated gene FTO functions in the brain to regulate postnatal growth in mice. PLoS One 2010, 5:e14005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fischer J, Koch L, Emmerling C, Vierkotten J, Peters T, Bruning JC, Ruther U: Inactivation of the Fto gene protects from obesity. Nature 2009, 458:894–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang Q, Riddle RC, Yang Q, Rosen CR, Guttridge DC, Dirckx N, Faugere MC, Farber CR, Clemens TL: The RNA demethylase FTO is required for maintenance of bone mass and functions to protect osteoblasts from genotoxic damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116:17980–17989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Choe J, Lin S, Zhang W, Liu Q, Wang L, Ramirez-Moya J, Du P, Kim W, Tang S, Sliz P, et al. : mRNA circularization by METTL3-eIF3h enhances translation and promotes oncogenesis. Nature 2018, 561:556–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin S, Choe J, Du P, Triboulet R, Gregory RI: The m6A Methyltransferase METTL3 Promotes Translation in Human Cancer Cells. Mol Cell 2016, 62:335–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rafalska I, Zhang Z, Benderska N, Wolff H, Hartmann AM, Brack-Werner R, Stamm S: The intranuclear localization and function of YT521-B is regulated by tyrosine phosphorylation. Hum Mol Genet 2004, 13:1535–1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]