Abstract

Neglected Tropical Diseases include a broad range of pathogens, hosts, and vectors, which represent evolving complex systems. Leishmaniasis, caused by different Leishmania species and transmitted to humans by sandflies, are among such diseases. Leishmania and other Trypanosomatidae display some peculiar features, which make them a complex system to study. Leishmaniasis chemotherapy is limited due to high toxicity of available drugs, long-term treatment protocols, and occurrence of drug resistant parasite strains. Systems biology studies the interactions and behavior of complex biological processes and may improve knowledge of Leishmania drug resistance. System-level studies to understand Leishmania biology have been challenging mainly because of its unusual molecular features. Networks integrating the biochemical and biological pathways involved in drug resistance have been reported in literature. Antioxidant defense enzymes have been identified as potential drug targets against leishmaniasis. These and other biomarkers might be studied from the perspective of systems biology and systems parasitology opening new frontiers for drug development and treatment of leishmaniasis and other diseases. Our main goals include: 1) Summarize current advances in Leishmania research focused on chemotherapy and drug resistance. 2) Share our viewpoint on the application of systems biology to Leishmania studies. 3) Provide insights and directions for future investigation.

Keywords: Leishmania, chemotherapy, drug resistance, systems biology, systems parasitology, molecular networks

Introduction

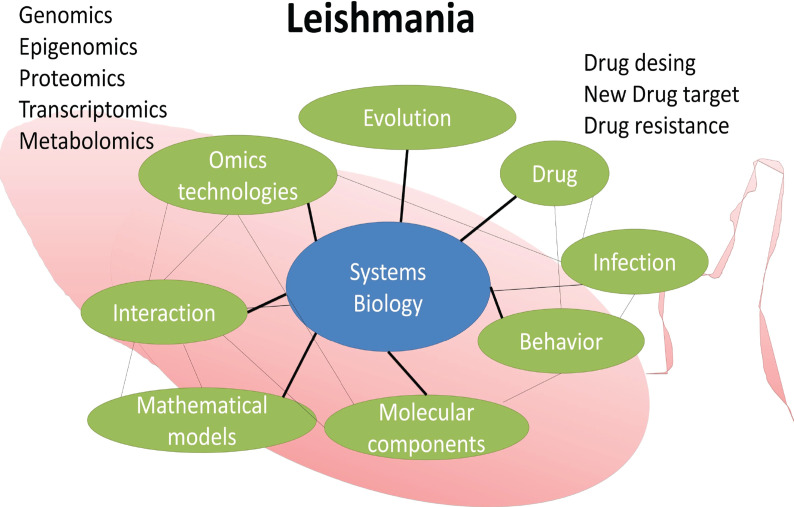

Leishmania is a complex biological system in itself. In the lack of an effective vaccine, human treatment relies on chemotherapy since the early 1920’s. Drug resistance of parasite strains adds a layer of complexity to this public health issue. Systems biology, which access interactions and behavior of complex biological processes, may improve knowledge of Leishmania drug resistance. Figure 1 shows the major components of Leishmania systems biology discussed in the present work.

Figure 1.

Leishmania systems biology. Some components of a systems biology study aiming at identifying molecular targets for drug design and development.

Here we present our perspective by providing a viewpoint on some specific areas of investigation as well as current advances and future directions. For this purpose, this article is organized into the following topics: Leishmania and leishmaniasis; Leishmaniasis treatment; Chemotherapy and antioxidant defense enzymes; Systems biology: concepts and applications; Leishmania systems biology; and Conclusions and future directions.

Leishmania and Leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis are among such diseases currently affecting 12 million people worldwide and presenting an incidence of 0.7-1.0 million new cases annually from nearly 100 endemic countries (WHO, 2021). Leishmaniasis are caused by over 21 different species of unicellular protozoan parasites of the genus Leishmania (Trypanosomatidae), which are transmitted to humans by infected female phlebotomine sandflies (Phlebotominae).

Some peculiar features are described for Leishmania and other Trypanosomatidae such as their kinetoplast, mitochondrial DNA editing (Simpson and Shaw, 1989; Ibrahim et al., 2008), glycosomes (Michels et al., 2006), polycistronic transcription (Martínez-Calvillo et al., 2003), trans-splicing (Boothroyd and Cross, 1982; Liang et al., 2003), GPI-anchored proteins (Mensa-Wilmot et al., 1999), and absence of promoter-mediated regulation of nuclear genes (Stefano et al., 2017). Leishmania species present a remarkable degree of conservation in gene content and architecture (synteny) according to their evolutionary divergence (Peacock, 2007; Lynn and McMaster, 2008; Real et al., 2013).

Leishmaniasis Treatment

There is no human vaccine available against Leishmania infection and control is based mainly on chemotherapy using a few drugs currently available. Leishmaniasis chemotherapy presents several issues, such as high drug toxicity, long treatment protocols, and the occurrence of drug resistant parasite strains.

It is important to highlight that drug resistance and therapeutic failure are not synonymous. Therapeutic failure encompasses factors related to the host (e.g. patient immune system and genetic factors), infectious agent (e.g., drug resistance, virulence, and pathogenic profiles of parasite species or strains), drugs (e.g. pharmacodynamics/pharmacokinetics), chemotherapeutic protocol, etc. (Ponte-Sucre et al., 2017).

Nevertheless, isolate’s drug resistance status is the first indication for therapeutic choice. Leishmania drug resistance threatens the prevention and treatment of infections. Literature shows that the mechanism of drug resistance in Leishmania involves different metabolic pathways including several molecular markers. However, little is known about the biochemical mechanisms underlying drug resistance in field isolates of this parasite. System biology approaches are very important to elucidate drug resistance mechanisms and identify new molecular markers and targets for drug development against leishmaniasis.

Pentavalent Antimonials

Pentavalent antimonials (e.g. sodium stibogluconate and meglumine antimoniate) have been used as the first-line treatment in many countries (Croft et al., 2006). Their mode of action is still not completely understood. It has been reported that antimony inhibits macromolecule biosynthesis in amastigotes, possibly via the inhibition of glycolysis and fatty acid oxidation (Berman et al., 1987), changing the thiol redox potential (Wyllie et al., 2004), DNA fragmentation, and apoptosis (Sereno et al., 2001; Sudhandiran and Shaha, 2003).

Treatment failure with pentavalent antimony (SbV) has been reported in Bihar (India), where more than 60% of patients with visceral leishmaniasis (VL) are unresponsive to this drug (Sundar, 2001). An epidemiological survey in this region suggested that arsenic-contaminated groundwater may also be associated with the treatment failure using SbV (Perry et al., 2015). Different antimony-resistance mechanisms have been described including decreased antimony cellular entry, decreased drug reduction/activation, increased antimony efflux, and sequestration of the metal-thiol conjugate into vesicular membranes of Leishmania (Croft et al., 2006).

Some of these mechanisms were described in both experimental and clinical resistance to SbV. Several ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters have been involved in SbV resistance. PGP/MRPA (ABCC3) was the first one described to be responsible for clinical resistance to SbV in L. donovani (Mittal et al., 2007; Mukherjee et al., 2007). Other mechanisms involved in SbV resistance in L. donovani include decreased drug uptake through inactivation of the aquaglyceroporin (AQP1) transporter (Mandal et al., 2010). AQP1 mutations are associated with a high level of antimony clinical resistance in L. donovani (Potvin et al., 2020).

Comparative proteomic and phosphoproteomic analyses of antimony trivalente (SbIII)-resistant (R) susceptible (S) L. braziliensis lines identified several potential candidates for biochemical or signaling networks associated with the antimony resistance in this parasite (Matrangolo et al., 2013; Moreira et al., 2015). Proteomic and genomic analyses of SbIII-resistant L. infantum mutants identified MRPA as a biomarker and suggested the involvement of chromosome number variations, specific gene amplifications, and SNPs as important features of antimony resistance (Brotherton et al., 2013). The transcriptomic profile showed that many pathways upregulated in L. infantum antimony-resistant lines are associated with protein phosphorylation, microtubule-based movement, protein ubiquitination, stress response, regulation of membrane lipid distribution, proteins involved in RNA metabolism, and other important metabolic pathways (Andrade et al., 2020). Together, these results show that the mechanism of antimony-resistance in Leishmania is complex and multifactorial, identifying several candidate genes that may be further evaluated as molecular targets for chemotherapy of leishmaniasis.

Several groups have used proteomic approaches for understanding the mechanisms of clinical resistance to antimony using SbV-resistant L. donovani isolates (Vergnes et al., 2007; Kumar et al., 2010; Biyani et al., 2011). These studies showed that the SbV-resistant L. donovani isolates have upregulated proteins of different metabolic pathways including glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, oxidative stress, and detoxification. Some of them include: ABC transporter, HSP-83, HSP-70, GPI protein transamidase, enolase, carboxypeptidase, among others.

Studies also demonstrated that the mechanism of antimony-resistance differs among the Leishmania species analyzed. A comparative proteomic analysis of SbIII-susceptible and resistant lines of L. braziliensis (LbWTS and LbSbR) and L. infantum (LiWTS and LiSbR) showed that 71.4% of protein spots with differential abundance identified were different between both species (Matrangolo et al., 2013). Only 28.6% of protein spots were common between them. Western blotting analysis confirmed the proteomic data results. For instance, the expression of pteridine reductase was higher in the LbSbR line compared to its susceptible counterpart LbWTS. However, the expression level of the PTR1 protein was similar between both L. infantum lines (Matrangolo et al., 2013). Functional analysis confirmed that pteridine reductase is associated with the antimony-resistance phenotype in L. braziliensis, but not in L. infantum (Moreira et al., 2016).

Amphotericin, Miltefosine, and Paromomycin

Amphotericin has shown efficacy for the VL treatment (Balasegaram et al., 2012). This is a polyene antibiotic that targets ergosterol, the major parasite membrane sterol. Liposomal amphotericin B shows lower toxicity compared to amphotericin B deoxycholate; however, it has a high cost. Amphotericin-resistant L. donovani lines selected in vitro displayed changes in drug-binding affinity to the plasma membrane as a result of a modified sterol composition (Mbongo et al., 1998). Treatment failure with amphotericin B has now been reported in India, where this drug has become the first-line option in areas where refractoriness to antimony is widespread (Purkait et al., 2012).

Miltefosine (hexadecylphosphocholine) is a phosphatidylcholine analogue initially developed as an antineoplastic drug shown to be very effective for the VL treatment in India (Sundar et al., 2002). This is the first and only drug administered orally against leishmaniasis. Miltefosine interferes in cell membrane composition by inhibiting phospholipid metabolism (Rakotomanga et al., 2007). The main mechanism of experimental resistance observed is associated with a significant reduction in miltefosine internalization (reduced uptake or increased efflux). Mutations or deletions in the miltefosine translocation process in L. donovani are associated with miltefosine resistance in both in vitro and in vivo assays (Perez-Victoria et al., 2006; Seifert et al., 2007). MT and/or Ros3 have also been associated with miltefosine-resistant phenotype in clinical isolates from leishmaniasis patients (Mondelaers et al., 2016; Srivastava et al., 2017).

Paromomycin is an aminoglycoside antibiotic that changes in the parasite protein synthesis, lipid metabolism, and mitochondrial activity (Maarouf et al., 1995; Maarouf et al., 1997). Clinical trials carried on in India indicated that paromomycin was effective in the VL treatment (Sundar et al., 2007). In contrast, a lower cure rate was not found in East Africa (Hailu et al., 2010). Paromomycin-resistant parasites selected in vitro showed a decreased drug accumulation (Bhandari et al., 2014). Differences in paromomycin susceptibility have been observed in different Leishmania species and clinical isolates (Prajapati et al., 2012).

Chemotherapy and Antioxidant Defense Enzymes

Trypanosomatidae antioxidant defense has been indicated as a potential target for chemotherapy based on their mechanism for trypanothione-dependent detoxification of peroxides, which differs from vertebrates. In this system, the thiol trypanothione maintains the reduced intracellular environment by the action of a trypanothione reductase (Turrens, 2004). Other enzymes participate in the enzymatic cascade.

Superoxide dismutase removes the excess of superoxide radicals by converting them to oxygen and hydrogen peroxide. Besides, tryparedoxin peroxidase and ascorbate peroxidase metabolize hydrogen peroxide into water molecules (Turrens, 2004). In order to investigate these enzymes in the antimony-resistance phenotype, L. braziliensis and L. infantum mutant lines overexpressing them were obtained (Andrade and Murta, 2014; Tessarollo et al., 2015; Moreira et al., 2018).

Results showed that the overexpression of iron superoxide dismutase-A (Tessarollo et al., 2015), tryparedoxin peroxidase (Andrade and Murta, 2014), or ascorbate peroxidase (Moreira et al., 2018) are involved in the SbIII-resistance phenotype in L. braziliensis. However, only iron superoxide dismutase-A plays a key function in maintaining the antimony resistance in the L. infantum line analyzed, while the other two enzymes are not directly associated with such phenotype. These results corroborate once again that the mechanism of antimony resistance differs among the Leishmania species.

Drug repositioning is an effective strategy to find new applications for existing drugs (Andrade-Neto et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2021). Thus, drugs and/or compounds that interact with different proteins involved in important metabolic pathways in Leishmania were searched. The ascorbate peroxidase sequence of Leishmania was used to seek possible drugs against this enzyme. This search returned the antibacterial agent Isoniazid, a synthetic derivative of isonicotinic acid used in tuberculosis treatment.

Results demonstrated that overexpression of ascorbate peroxidase confers resistance to Isoniazid (Moreira et al., 2018). Surprisingly, Isoniazid raised the antileishmanial effect of SbIII, mainly against L. braziliensis clones overexpressing ascorbate peroxidase. Such drug combination might be a good strategy to be considered in leishmaniasis chemotherapy.

Systems Biology: Concepts and Applications

The origin of systems biology is still under debate among scientists, with some claiming that it was first applied by Norbert Wiener and Erwin Schrödinger or Claude Bernard around 90 and 150 years ago, respectively (cf. Saks et al., 2009). Despite different viewpoints, some agree that systems biology was first coined in the 1960s, when theoretical biologists began creating computer-run mathematical models of biological systems (Noble, 1960).

In our view, systems biology is the study of the interactions and behavior of complex biological processes based on their molecular constituents. The applied analytical approach focuses on the quantitative measurement of biological processes, mathematical modeling, and reconstruction with the aim of bringing to light the transfer of information resulting from the integration of biological data (Kirschner, 2005, Noble and Bernard, 2008, Breitling, 2010).

Systems biology is interdisciplinary and includes a wide range of data from in vivo, in vitro, in situ, and in silico studies. Ideally, in silico studies would be integrated and validated by other data sources especially when applicable outcomes are aimed (Butcher et al., 2004; Dunn et al., 2010; Bora and Jha, 2019).

Currently, mathematical models have been extensively used to understand biological processes in life sciences, including but not restricted to the analysis of genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics of a broad range of taxa (Zhao and Li, 2017; Cheng and Leung, 2018; Djordjevic et al., 2019).

Considering the complex parasite biology, the study criteria are crucial for choosing the dataset to be analyzed, taking into account the number of samples, amount of noise, experimental design, etc. Together, these criteria interfere in the network construction and downstream analyzes. The statistical network inference method, type of interaction structure (scale-free, random, and small-world), and error measurement (global and local) are also relevant.

Because of the complexity of biological systems, it is important to understand the interactions among genotype, phenotype, and environment. Systems biology addresses such aspects by applying quantitative measurement, mathematical modeling, and interdisciplinary studies including ecology and evolutionary biology (Kirschner, 2005; Medina, 2005).

By using a system biology approach, a large number of non-linear molecular interactions can be explored, such as post-transcriptional or post-translational modifications, metabolic effects, and protein recruitment dynamics in different cellular compartments. The idea is to go beyond the simplistic model of gene role determination and its phenotypic effect (Likić et al., 2010).

Leishmania Systems Biology

Efforts of drug repositioning and development of new drugs require systems biology approaches to understand the genetic basis of diseases including leishmaniasis. An essential aspect of systems biology in drug discovery is the identification of potential drug targets considering the presence of multiple genes and proteins involved (Kunkel, 2006; Chavali et al., 2008; Sharma et al., 2017). In parasites, this might be understood from signaling pathways in which essential proteins participate (Sharma et al., 2017). In addition to derive novel biological hypotheses about molecular interactions involved in drug resistance, such networks may provide information to support functional prediction of genes and proteins. Currently, a huge number of protein coding genes from sequencing projects are annotated with hypothetical, predicted, or unknown functions.

The so-called omics technologies have been the driving force behind systems biology (Silva et al., 2012; Moreira et al., 2015). These technologies include genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and among others applied to the study of a broad range of taxa including Leishmania ( Figure 1 ). This multidirectional and interdisciplinary integration will certainly provide experimental outcomes with impact in public health.

The divide-and-conquer approach, in which a big problem is recursively breaking down into sub-problems of the same or related type simple enough to be solved, is a robust strategy to be implemented. Among the numerous fields (sub-problems) in which systems biology would play a crucial role, we highlight the issue of drug resistance in Leishmania treatment (Ponte-Sucre et al., 2017).

The inference of gene regulatory networks is just a “blueprint” in the discovery of new interactions among biological entities of the drug resistance in Leishmania and other taxa. Here we provide an overview of some components of a systems biology study aiming at identifying molecular targets for drug design and development in Leishmania ( Figure 1 ).

The genome-scale metabolic model of L. donovani supported functional annotation for hypothetical or erroneously annotated genes by comparing results with experimental data (Rezende et al., 2012; Sharma et al., 2017). In addition to annotation, authors have predicted molecular networks for Leishmania and other Trypanosomatidae (Rezende et al., 2012; Vasconcelos et al., 2018).

System biology studies of pathway modeling may be able to identify pathways associated with mechanisms of drug resistance in Leishmania (Brito et al., 2017; Ponte-Sucre et al., 2017). Results of in vitro approaches for the identification of genes or proteins associated with drug resistance should be integrated with in silico studies and used for validation of the omics strategies (Kunkel, 2006). Combined drug and vaccine therapy can successfully treat leishmaniasis patients, but there are still several side effects and a high cost involved (Ghorbani and Farhoudi, 2017).

In the case of the pentavalent antimonials, a network integrating biochemical and biological pathways is reported (Ponte-Sucre et al., 2017). For instance, the ABC transport pathway is involved in drug efflux and therefore with drug resistance (Coelho and Cotrim, 2013). Aquaglyceroporin overexpression or deletion is also associated with resistance (Marquis et al., 2005). Gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase may protect against oxidative stress and SbV (Mukherjee et al., 2009). Reduction of SbV to SbIII is involved in drug activity and internalization as well as glycolysis inhibition of fatty acid oxidation (Berman et al., 1987; Roychoudhury and Ali, 2008). Trypanothione and glutathione regulate the intracellular thiol redox balance and participate in the chemical and oxidative stress defense (Croft et al., 2006; Singh, 2006; Maltezou, 2010). Tryparedoxin peroxidase from a complex redox cascade and its overexpression is linked to resistance (Wyllie et al., 2008; Andrade and Murta, 2014). Zinc finger domains are associated with drug resistance due to the ability of SbIII to compete with ZnII and the modulation of the pharmacological action of antimonials (Frézard et al., 2012).

One possible approach is the integration of public available RNAseq data depicting the resistance phenomena in gene regulatory networks (Andrade et al., 2020). Such approach has demonstrated how genes interact with each other and how changes in their expression levels may result, for example, in different immunological responses promoting distinct disease outcomes including leishmaniasis (Mol et al., 2018).

The resulting association among specific transcriptional states of all genes involved in drug resistance will represent a key tool for the study and modeling of this complex biological process. Altogether, these studies have the potential to lead the identification of better drug targets and markers for pathogenesis.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Computational modeling of the molecular components of drug resistance in Leishmania through the biophysicochemical monitoring of genes and proteins involved in the processes is important. Integrating metabolic and signaling pathways is crucial to reveal the correlations among molecular functions and physiological processes shedding light on a broad understanding of the drug resistance phenomena.

We believe that in a near future, neither the understanding of Trypanosomatidae biology nor their drug resistance phenomena will be conceivable without studying molecular networks. In this context, protein-protein interactions and gene regulatory networks represent a practical embodiment of systems biology.

Biomarkers involved in drug resistance might be studied into more details from the systems biology perspective. Altogether, these studies could contribute to a better understanding of parasite biology and drug resistance mechanisms. Moreover, this approach will improve the knowledge of systems parasitology and open new frontiers in the identification of new molecular targets for drug development and treatment of leishmaniasis and other diseases.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

LN: designed and coordinated this work. JR, SM, and LN: wrote and revised the manuscript. EH and JH: collected data, wrote, revised the manuscript, and developed the artwork (figure). All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the FIOCRUZ Innovation Promotion Program (INOVA FIOCRUZ; JR: VPPIS-001-FIO-18-12, VPPIS-001-FIO-18-8, VPPIS-005-FIO-20-2-36, and VPPCB-005-FIO-20-2-42. SMFM: VPPCB-007-FIO-18-2-94), Institut Pasteur/FIOCRUZ (SM: no grant number), Minas Gerais Research Funding Foundation (FAPEMIG; SM: CBB-PPM 00610/15), and National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq; JR: 310104/2018-1. SMFM: 304158/2019-4). Graduate student fellowships were provided by the Higher Education Improvement Coordination (CAPES; EH: 88887.502799/2020-00) and FIOCRUZ Vice-Presidency of Education, Information and Communication (FIOCRUZ/VPEIC; JH: no process number).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ) and the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG) for providing an environment for scientific excellence and commitment to public health. The authors wish to thank the Program for Technological Development of Health Products (PDTIS/FIOCRUZ) for providing different facilities. We also thank the Graduate Program in Health Science (IRR/FIOCRUZ) and Graduate Program in Genetics (UFMG) for their support and commitment with Science education. Our special thanks to colleagues and students for their permanent support and inspiration to face many challenges. Two anonymous reviewers have contributed significantly to the revision and improvement of this manuscript.

References

- Andrade J. M., Gonçalves L. O., Liarte D. B., Lima D. A., Guimarães F. G., de Melo Resende D., et al. (2020). Comparative Transcriptomic Analysis of Antimony Resistant and Susceptible Leishmania Infantum Lines. Parasites Vectors. 13, 600. 10.1186/s13071-020-04486-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade J. M., Murta S. M. F. (2014). Functional Analysis of Cytosolic Tryparedoxin Peroxidase in Antimony-Resistant and -Susceptible Leishmania Braziliensis and Leishmania Infantum Lines. Parasites Vectors. 7:406. 10.1186/1756-3305-7-406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade-Neto V. V., Cunha-Junior E. F., Faioes V. S. (2018). Leishmaniasis Treatment: Update of Possibilities for Drug Repurposing. Front. In Biosci. 23, 967–996. 10.2741/4629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasegaram M., Ritmeijer K., Lima M. A., Burza S., Ortiz Genovese G., Milani B., et al. (2012). Liposomal Amphotericin B as a Treatment for Human Leishmaniasis. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs 17, 493–510. 10.1517/14728214.2012.748036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman J. D., Gallalee J. V., Best J. M. (1987). Sodium Stibogluconate (Pentostam) Inhibition of Glucose Catabolism Via the Glycolytic Pathway, and Fatty Acid Beta-Oxidation in Leishmania Mexicana Amastigotes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 36, 197–201. 10.1016/0006-2952(87)90689-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari V., Sundar S., Dujardin J. C., Salotra P. (2014). Elucidation of Cellular Mechanisms Involved in Experimental Paromomycin Resistance in Leishmania Donovani . Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 2580–2585. 10.1128/AAC.01574-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biyani N., Singh A. K., Mandal S., Chawla B., Madhubala R. (2011). Differential Expression of Proteins in Antimony-Susceptible and -Resistant Isolates of Leishmania Donovani. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 179, 91–99. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2011.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothroyd J. C., Cross G. A. (1982). Transcripts Coding for Variant Surface Glycoproteins of Trypanosoma Brucei Have a Short, Identical Exon At Their 5’ End. Gene 20, 281–289. 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90046-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora N., Jha A. N. (2019). An Integrative Approach Using Systems Biology, Mutational Analysis With Molecular Dynamics Simulation to Challenge the Functionality of a Target Protein. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 93, 1050–1060. 10.1111/cbdd.13502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitling R. (2010). What is systems biology? Front Physiol. 21, 9. 10.3389/fphys.2010.00009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito N. C., Rabello A., Cota G. F. (2017). Efficacy of Pentavalent Antimoniate Intralesional Infiltration Therapy for Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: A Systematic Review. PloS One 12 (9):184777. 10.1371/journal.pone.0184777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotherton M.-C., Bourassa S., Leprohon P., Légaré D., Poirier G. G., Droit A., et al. (2013). Proteomic and Genomic Analyses of Antimony Resistant Leishmania Infantum Mutant. PloS One 8 (11), 81899. 10.1371/journal.pone.0081899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher E. C., Berg E. L., Kunkel E. J. (2004). Systems Biology in Drug Discovery. Nat. Biotechnol. 22 (10), 1253–1259. 10.1038/nbt1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavali A. K., Whittemore J. D., Eddy J. A., Williams K. T., Papin J. A. (2008). Systems Analysis of Metabolism in the Pathogenic Trypanosomatid Leishmania Major . Mol. Syst. Biol. 4, 177. 10.1038/msb.2008.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L., Leung K. S. (2018). Quantification of non-Coding RNA Target Localization Diversity and its Application in Cancers. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 130–138. 10.1093/jmcb/mjy006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho A. C., Cotrim P. C. (2013). The Role of ABC Transporters in Drug-Resistant Leishmania. In: Ponte-Sucre A., Diaz E., Padrón-Nieves M. (eds) Drug Resistance in Leishmania Parasites. Viena: Springer. 237–258. 10.1007/978-3-7091-1125-3_12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Croft S. L., Sundar S., Fairlamb A. H. (2006). Drug Resistance in Leishmaniasis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19, 111–126. 10.1128/CMR.19.1.111-126.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djordjevic M., Rodic A., Graovac S. (2019). From Biophysics to ‘Omics and Systems Biology. Eur. Biophys. J. 48, 413–424. 10.1007/s00249-019-01366-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn D. A., Apanovitch D., Follettie M., He T., Ryan T. (2010). Taking a Systems Approach to the Identification of Novel Therapeutic Targets and Biomarkers. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 11 (7), 721–734. 10.2174/138920110792927739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frézard F., Silva H., Pimenta A. M., Farrell N., Demicheli C. (2012). Greater Binding Affinity of Trivalent Antimony to a CCCH Zinc Finger Domain Compared to a CCHC Domain of Kinetoplastid Proteins. Metallomics 4, 433–440. 10.1039/c2mt00176d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani M., Farhoudi R. (2017). Leishmaniasis in Humans: Drug or Vaccine Therapy? Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 22 (12), 25–40. 10.2147/DDDT.S146521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hailu A., Musa A., Wasunna M., Balasegaram M., Yifru S., Mengistu G., et al. (2010). Geographical Variation in the Response of Visceral Leishmaniasis to Paromomycin in East Africa: A Multicentre, Open-Label, Randomized Trial. PloS Neglect. Trop. Dis. 4, 709. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim M. E., Mahdi M. A., Bereir R. E., Giha R. S., Wasunna C. (2008). Evolutionary Conservation of RNA Editing in the Genus Leishmania. Infect. Genet. Evol. 8, 378–380. 10.1016/j.meegid.2007.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner M. W. (2005). The Meaning of Systems Biology. Cell 121, 503–504. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Sisodia B., Misra P., Sundar S., Shasany A. K., Dube A. (2010). Proteome Mapping of Overexpressed Membrane-Enriched and Cytosolic Proteins in Sodium Antimony Gluconate (SAG) Resistant Clinical Isolate of Leishmania Donovani. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 70, 609–617. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03716.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel E. (2006). Systems Biology in Drug Discovery. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 37, 37. 10.1109/IEMBS.2006.259390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X. H., Haritan A., Uliel S., Michaeli S. (2003). Trans and Cis Splicing in Trypanosomatids: Mechanism, Factors, and Regulation. Eukaryot. Cell. 2, 830–840. 10.1128/ec.2.5.830-840.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likić V. A., McConville M. J., Lithgow T., Bacic A. (2010). Systems Biology: The Next Frontier for Bioinformatics. Adv. Bioinf. 2010, 268925. 10.1155/2010/268925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn M. A., McMaster W. R. (2008). Leishmania: Conserved Evolution–Diverse Diseases. Trends Parasitol. 24 (3), 103–105. 10.1016/j.pt.2007.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maarouf M., De Kouchkovsky Y., Brown S., Petit P. X., Robert-Gero M. (1997). In Vivo Interference of Paromomycin With Mitochondrial Activity of Leishmania. Exp. Cell Res. 232, 339–348. 10.1006/excr.1997.3500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maarouf M., Lawrence F., Croft S. L., Robert-Gero M. (1995). Ribosomes of Leishmania are a Target for the Aminoglycosides. Parasitol. Res. 81, 421–425. 10.1007/BF00931504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltezou H. C. (2010). Drug Resistance in Visceral Leishmaniasis. J. BioMed. Biotechnol. 2010, 617521. 10.1155/2010/617521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal S., Maharjan M., Singh S., Chatterjee M., Madhubala R. (2010). Assessing Aquaglyceroporin Gene Status and Expression Profile in Antimony-Susceptible and -Resistant Clinical Isolates of Leishmania Donovani From India. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65 (3), 496–507. 10.1093/jac/dkp468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquis N., Gourbal B., Rosen B. P., Mukhopadhyay R., Ouellette M. (2005). Modulation in Aquaglyceroporin AQP1 Gene Transcript Levels in Drug-Resistant Leishmania. Mol. Microbiol. 57, 1690–1699. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Calvillo S., Yan S., Nguyen D., Fox M., Stuar T. K., Myle R. P. J. (2003). Transcription of Leishmania Major Friedlin Chromosome 1 Initiates in Both Directions Within a Single Region. Mol. Cell. 11, 1291–1299. 10.1016/s1097-2765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matrangolo F. S., Liarte D. B., Andrade L. C., de Melo M. F., Andrade J. M., Ferreira R. F., et al. (2013). Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Antimony-Resistant and -Susceptible Leishmania Braziliensis and Leishmania Infantum Chagasi Lines. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 190, 63–75. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2013.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbongo N., Loiseau P. M., Billion M. A., Robert-Gero M. (1998). Mechanism of Amphotericin B Resistance in Leishmania Donovani Promastigotes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42, 352–357. 10.1128/AAC.42.2.352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina M. (2005). Genomes, Phylogeny, and Evolutionary Systems Biology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 3 (102), 6630–6635. 10.1073/pnas.0501984102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensa-Wilmot K., Garg N., McGwire B. S., Lu H. G., Zhong L., Armah D. A., et al. (1999). Roles of Free GPIs in Amastigotes of Leishmania. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 99, 103–116. 10.1016/s0166-6851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michels P. A., Bringaud F., Herman M., Hannaert V. (2006). Metabolic Functions of Glycosomes in Trypanosomatids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1763 (12), 1463–1477. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal M. K., Rai S., Ashutosh, Ravinder, Gupta S., Sundar S., et al. (2007). Characterization of Natural Antimony Resistance in Leishmania Donovani Isolates. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 76 (4), 681–688. 10.4269/ajtmh.2007.76.681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mol M., Kosey D., Boppana R., Singh S. (2018). Transcription Factor Target Gene Network Governs the Logical Abstraction Analysis of the Synthetic Circuit in Leishmaniasis. Sci. Rep. 8, 3464. 10.1038/s41598-018-21840-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondelaers A., Sanchez-Cañete M. P., Hendrickx S., Eberhardt E., Garcia-Hernandez R., Lachaud L., et al. (2016). Genomic and Molecular Characterization of Miltefosine Resistance in Leishmania Infantum Strains With Either Natural or Acquired Resistance Through Experimental Selection of Intracellular Amastigotes. PloS One 11 (4):154101. 10.1371/journal.pone.0154101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira D. S., Ferreira R. F., Murta S. M. F. (2016). Molecular Characterization and Functional Analysis of Pteridine Reductase in Wild-Type and Antimony-Resistant Leishmania Lines. Exp. Parasitol. 160, 60–66. 10.1016/j.exppara.2015.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira D. S., Pescher P., Laurent C., Lenormand P., Späth G. F., Murta S. M. (2015). Phosphoproteomic Analysis of Wild-Type and Antimony-Resistant Leishmania Braziliensis Lines by 2D-DIGE Technology. Proteomics 15 (17), 2999–3019. 10.1002/pmic.201400611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira D. S., Xavier M. V., Murta S. M. F. (2018). Ascorbate Peroxidase Overexpression Protects Leishmania Braziliensis Against Trivalent Antimony Effects. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 113:180377. 10.1590/0074-02760180377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A., Padmanabhan P. K., Singh S., Roy G., Girard I., Chatterjee M., et al. (2007). Role of ABC Transporter MRPA, Gamma-Glutamylcysteine Synthetase and Ornithine Decarboxylase in Natural Antimony-Resistant Isolates of Leishmania Donovani. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 59, 204–211. 10.1093/jac/dkl494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A., Roy G., Guimond C., Ouellette M. (2009). The γ-Glutamylcysteine Synthetase Gene of Leishmania is Essential and Involved in Response to Oxidants. Mol. Microbiol. 74, 914–927. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble D., Bernard C. (2008). Claude Bernard, the First Systems Biologist, and the Future of Physiology. Exp. Physiol. 93, 16–26. 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.038695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock C. S. (2007). Comparative Genomic Analysis of Three Leishmania Species That Cause Diverse Human Disease. Nat. Genet. 39, 839–847. 10.1038/ng2053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Victoria F. J., Sanchez-Canete M. P., Castanys S., Gamarro F. (2006). Phospholipid Translocation and Miltefosine Potency Require Both L. Donovani Miltefosine Transporter and the New Protein LdRos3 in Leishmania Parasites. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 23766–23775. 10.1074/jbc.M605214200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry M. R., Prajapati V. K., Menten J., Raab A., Feldmann J., Chakraborti D., et al. (2015). Arsenic Exposure and Outcomes of Antimonial Treatment in Visceral Leishmaniasis Patients in Bihar, India: A Retrospective Cohort Study. PloS Negl. Trop. Dis. 9 (3):3518. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponte-Sucre A., Gamarro F., Dujardin J. C., Barrett M. P., López-Vélez R., García-Hernández R., et al. (2017). Drug Resistance and Treatment Failure in Leishmaniasis: A 21st Century Challenge. PloS Negl. Trop. Dis. 14 (11), 12. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potvin J. E., Leprohon P., Queffeulou M., Sundar S., Ouellette M. (2020). Mutations in an Aquaglyceroporin as a Proven Marker of Antimony Clinical Resistance in the Parasite Leishmania Donovani. Clin. Infect. Dis. 22:1236. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prajapati V. K., Mehrotra S., Gautam S., Rai M., Sundar S. (2012). In Vitro Antileishmanial Drug Susceptibility of Clinical Isolates From Patients With Indian Visceral Leishmaniasis – Status of Newly Introduced Drugs. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 87, 655–657. 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purkait B., Kumar A., Nandi N., Sardar A. H., Das S., Kumar S., et al. (2012). Mechanism of Amphotericin B Resistance in Clinical Isolates of Leishmania Donovani. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 1031–1041. 10.1128/AAC.00030-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakotomanga M., Blanc S., Gaudin K., Chaminade P., Loiseau P. M. (2007). Miltefosine Affects Lipid Metabolism in Leishmania Donovani Promastigotes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 1425–1430. 10.1128/AAC.01123-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Real F., Vidal R. O., Carazzolle M. F., Mondego J. M. C., Costa G. G. L., Herai R. H. (2013). The Genome Sequence of Leishmania (Leishmania) Amazonensis: Functional Annotation and Extended Analysis of Gene Models. DNA Res. 20, 567–581. 10.1093/dnares/dst031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezende A. M., Folador E. L., Resende D., de M., Ruiz J. C. (2012). Computational Prediction of Protein-Protein Interactions in Leishmania Predicted Proteomes. PloS One 7, 12. 10.1371/journal.pone.0051304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roychoudhury J., Ali N. (2008). Sodium Stibogluconate: Therapeutic Use in the Management of Leishmaniasis. Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. 45, 16–22. ISSN: 0301-1208. [Google Scholar]

- Saks V., Monge C., Guzun R. (2009). Philosophical Basis and Some Historical Aspects of Systems Biology: From Hegel to Noble Applications for Bioenergetic Research. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 10, 1161–1192. 10.3390/ijms10031161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert K., Perez-Victoria F. J., Stettler M., Sanchez-Canete M. P., Castanys S., Gamarro F., et al. (2007). Inactivation of the Miltefosine Transporter, LdMT, Causes Miltefosine Resistance That is Conferred to the Amastigote Stage of Leishmania Donovani and Persists In Vivo. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 30, 229–235. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sereno D., Holzmuller P., Mangot I., Cuny G., Ouaissi A., Lemesre J.-L. (2001). Antimonial-Mediated DNA Fragmentation in Leishmania Infantum Amastigotes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 2064–2069. 10.1128/AAC.45.7.2064-2069.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M., Shaikh N., Yadav S., Singh S., Garg P. (2017). A Systematic Reconstruction and Constraint-based Analysis of Leishmania Donovani Metabolic Network: Identification of Potential Antileishmanial Drug Targets. Mol. BioSys. 13 (5), 955–969. 10.1039/c6mb00823b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva L. L., Marcet-Houben M., Nahum L. A. (2012). The Schistosoma Mansoni Phylome: Using Evolutionary Genomics to Gain Insight Into a Parasite’s Biology. BMC Genomics 13, 617. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva J. A. S., Tunes L. G., Coimbra R. S. (2021). Unveiling Six Potent and Highly Selective Antileishmanial Agents Via the Open Source Compound Collection ‘Pathogen Box’ Against Antimony-Sensitive and -Resistant Leishmania Braziliensis. Biomed Pharmacother. 133, 111049. 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.111049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson L., Shaw J. (1989). RNA Editing and the Mitochondrial Cryptogenes of Kinetoplastid Protozoa. Cell 57, 355–366. 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90911-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N. (2006). Drug Resistance Mechanisms in Clinical Isolates of Leishmania Donovani. Indian J. Med. Res. 123, 411–422. 10.1016/j.cyto.2020.155300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S., Mishra J., Gupta A. K., Singh A., Shankar P., Singh S. (2017). Laboratory Confirmed Miltefosine Resistant Cases of Visceral Leishmaniasis From India. Parasit. Vectors 10 (1), 49. 10.1186/s13071-017-1969-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefano A., Iantorno S. A., Durrant C., Khan A., Sanders M. J., Beverley S. M., et al. (2017). Gene Expression in Leishmania is Regulated Predominantly by Gene Dosage. mBio 12, 01393–01317. 10.1128/mBio.01393-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhandiran G., Shaha C. (2003). Antimonial-Induced Increase in Intracellular Ca2+ Through non-Selective Cation Channels in the Host and the Parasite is Responsible for Apoptosis of Intracellular Leishmania Donovani Amastigotes. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25120–25132. 10.1074/jbc.M301975200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundar S. (2001). Drug Resistance in Indian Visceral Leishmaniasis. Trop. Med. Int. Health 6, 849–854. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00778.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundar S., Jha T. K., Thakur C. P., Engel J., Sindermann H., Fischer C., et al. (2002). Oral Miltefosine for Indian Visceral Leishmaniasis. New Engl. J. Med. 347, 1739–1746. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundar S., Jha T. K., Thakur C. P., Sinha P. K., Bhattacharya S. K. (2007). Injectable Paromomycin for Visceral Leishmaniasis in India. New Engl. J. Med. 356, 2571–2581. 10.1056/NEJMoa066536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessarollo N. G., Andrade J. M., Moreira D. S., Murta S. M. (2015). Functional Analysis of Iron Superoxide Dismutase-a in Wild-Type and Antimony-Resistant Leishmania Braziliensis and Leishmania Infantum Lines. Parasitol. Int. 64, 125–129. 10.1016/j.parint.2014.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrens J. F. (2004). Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Defenses: A Target for the Treatment of Diseases Caused by Parasitic Protozoa. Mol. Aspects Med. 25, 211–220. 10.1016/j.mam.2004.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos C. R. S., Campos T. L., Rezende A. M. (2018). Building Protein-Protein Interaction Networks for Leishmania Species Through Protein Structural Information. BMC Bioinf. 6 (19), 85. 10.1186/s12859-018-2105-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergnes B., Gourbal B., Girard I., Sundar S., Drummelsmith J., Ouellette M. (2007). A Proteomics Screen Implicates HSP83 and a Small Kinetoplastid Calpain-Related Protein in Drug Resistance in Leishmania Donovani Clinical Field Isolates by Modulating Drug-Induced Programmed Cell Death. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 6, 88–101. 10.1074/mcp.M600319-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. World Health Organization (2021) Leishmaniasis Overview. Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/leishmaniasis#tab=tab (Accessed 31 March 2021).

- Wyllie S., Cunningham M. L., Fairlamb A. H. (2004). Dual Action of Antimonial Drugs on Thiol Redox Metabolism in the Human Pathogen Leishmania Donovani. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 39925–39932. 10.1074/jbc.M405635200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyllie S., Vickers T. J., Fairlamb A. H. (2008). Roles of Trypanothione S-transferase and Tryparedoxin Peroxidase in Resistance to Antimonials. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52, 1359–1365. 10.1128/AAC.01563-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X.-M., Li S. (2017). HISP: A Hybrid Intelligent Approach for Identifying Directed Signaling Pathways. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 453–462. 10.1093/jmcb/mjx054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.