Abstract

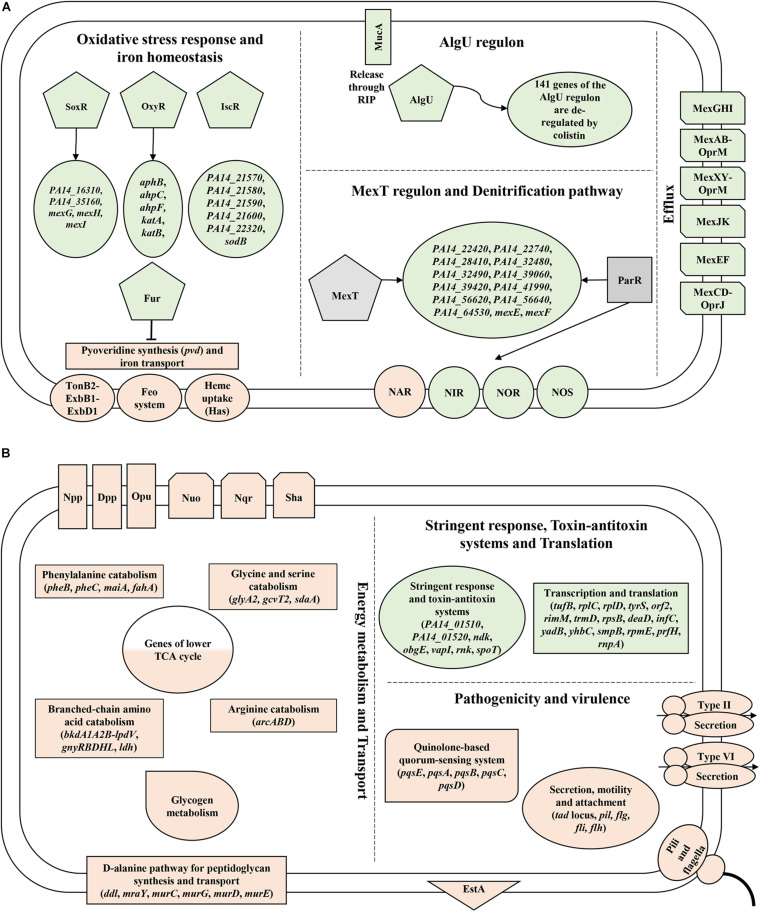

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Pae) is notorious for its high-level resistance toward clinically used antibiotics. In fact, Pae has rendered most antimicrobials ineffective, leaving polymyxins and aminoglycosides as last resort antibiotics. Although several resistance mechanisms of Pae are known toward these drugs, a profounder knowledge of hitherto unidentified factors and pathways appears crucial to develop novel strategies to increase their efficacy. Here, we have performed for the first time transcriptome analyses and ribosome profiling in parallel with strain PA14 grown in synthetic cystic fibrosis medium upon exposure to polymyxin E (colistin) and tobramycin. This approach did not only confirm known mechanisms involved in colistin and tobramycin susceptibility but revealed also as yet unknown functions/pathways. Colistin treatment resulted primarily in an anti-oxidative stress response and in the de-regulation of the MexT and AlgU regulons, whereas exposure to tobramycin led predominantly to a rewiring of the expression of multiple amino acid catabolic genes, lower tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle genes, type II and VI secretion system genes and genes involved in bacterial motility and attachment, which could potentially lead to a decrease in drug uptake. Moreover, we report that the adverse effects of tobramycin on translation are countered with enhanced expression of genes involved in stalled ribosome rescue, tRNA methylation and type II toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems.

Keywords: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, colistin, tobramycin, RNA-Seq, ribosome profiling, Ribo-seq

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Pae) is an opportunistic pathogen known to cause nosocomial infections that are particularly detrimental to immunocompromised individuals and to patients suffering from cystic fibrosis (CF) (Williams et al., 2010). On the one hand, the pathogenic potential of Pae is based on its metabolic versatility, permitting fast adaptation to changing environmental conditions. On the other hand Pae can form biofilms and produce multiple virulence factors (Kerr and Snelling, 2009; Gellatly and Hancock, 2013). Pae is characterized by high intrinsic resistance to a wide variety of antibiotics. It can further develop resistance by acquisition of genetic determinants through horizontal gene transfer, as well as by mutational processes affecting “resistance genes” that are collectively termed the resistome (Wright, 2007; Fajardo et al., 2008; Breidenstein et al., 2011; Jaillard et al., 2017). In this way, Pae has rendered most antibiotics ineffective, leaving polymyxins and aminoglycosides as last resort antibiotics.

Polymyxins are polycationic cyclic antimicrobial peptides. Owing to their positively charged 2,4-diaminobuteric acid (Dab) moieties they can electrostatically interact with the negatively charged lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of the outer membrane (OM) of Gram-negative bacteria, causing the displacement of LPS-stabilizing divalent cations, Ca2+ and Mg2+. This interaction is followed by insertion of the hydrophobic segments of the drug into the OM and its penetration via a self-promoted uptake mechanism. Cell death subsequently occurs by disintegration of the inner membrane (IM) and leakage of cellular components (El-Sayed Ahmed et al., 2020). Moreover, it has been reported that polymyxins can exert their toxic effects by causing phospholipid exchange between the OM and IM (Velkov et al., 2013), inhibition of respiratory enzymes of the NADH oxidase family (Deris et al., 2014), binding to bacterial DNA and disrupting its synthesis (Kong et al., 2011) and/or formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Sampson et al., 2012; Yu et al., 2017). Nevertheless, the mode of bactericidal action of polymyxins in Pae remains controversial. For instance, a recent study (O’Driscoll et al., 2018) indicated that polymyxin E (colistin) does not exert its antibacterial effect by puncturing the IM or by inhibiting DNA replication and transcription. In addition, the exact contribution of polymyxin induced ROS to lethality of Pae is largely inconclusive (Brochmann et al., 2014; Lima et al., 2019).

In contrast, the regulatory circuits underlying polymyxin resistance are well understood in Pae. An increased resistance is conveyed by reduction of the net negative charge of LPS, resulting in diminished polymyxin binding (Jeannot et al., 2017; Poirel et al., 2017). The cellular machinery for covalent modification of negatively charged lipid A of LPS with positively charged 4-amino-L-arabinose (Lara4N) is encoded by the arn (pmr) operon. This operon is activated by at least five two-component systems (TCS) including PhoP/PhoQ (Barrow and Kwon, 2009), PmrA/PmrB (McPhee et al., 2003), ParR/ParS (Fernández et al., 2010), ColR/ColS and CprR/CprS (Fernández et al., 2012; Gutu et al., 2013). In addition, the cprA gene product was found to be required for polymyxin resistance conferred by the PhoP/PhoQ, PmrA/PmrB, and CprR/CprS TCSs (Gutu et al., 2013). Furthermore, a number of other functions contributing to intrinsic polymyxin resistance have been identified, which mainly affect LPS biosynthesis-related functions (regulatory functions, metabolism, synthesis and transport) (Fernández et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2017; Sherry and Howden, 2018). Moreover, overproduction of spermidine and of the OM protein OprH have been shown to contribute as well to polymyxin susceptibility, as they can interact with divalent cation-binding sites of LPS, making them inaccessible for polymyxin binding (Young et al., 1992; Johnson et al., 2011). On the other hand, a reduced expression of oprD increased cell survival in the presence of polymyxins through an unknown mechanism (Mlynarcik and Kolar, 2019). Additionally, the MexXY-OprM and MexAB-OprM efflux pump systems can provide low to moderate polymyxin resistance and tolerance respectively (Pamp et al., 2008; Muller et al., 2011; Poole et al., 2015).

Aminoglycosides are positively charged antibiotics that initially interact with LPS of Gram-negative Bacteria. Aminoglycosides require an energized membrane for translocation into the cytoplasm. Once inside the cells, they bind to 16S rRNA at the A-site of the 30S ribosomal subunit, disrupting translation and causing the synthesis of aberrant polypeptides. These polypeptides can be inserted into the cell membrane, causing membrane damage, which leads to further intracellular accumulation of aminoglycosides. The established autocatalytic loop of membrane damage and their increased uptake results in stalling of ribosomes, and in complete inhibition of protein synthesis (Krause et al., 2016).

Covalent modifications of the negatively charged moieties of LPS, 16S rRNA methylation by RNA methyltransferases, ribosomal mutations and aminoglycoside modifying enzymes (AMEs) are exploited by Pae to counteract aminoglycosides (Poole, 2005; Garneau-Tsodikova and Labby, 2016; Krause et al., 2016; Valderrama-Carmona et al., 2019). The main efflux system responsible for the extrusion of aminoglycosides is MexXY-OprM (Poole, 2005). Its synthesis is controlled by PA5471, an anti-repressor of the mexXY operon repressor MexZ (Morita et al., 2006; Hay et al., 2013). Additional efflux systems include MexAB-OprM and an ortholog of the EmrE multidrug transporter of Escherichia coli (Poole, 2005; Nasie et al., 2012). Moreover, protein chaperones such as GroEL/ES, GrpE and HtpX, as well as the AmgR/AmgS TCS have been implicated in protecting the cells from polypeptides arising from drug induced mistranslation (Hinz et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2015).

A number of studies have confirmed the safety of colistin for treatment of acute pulmonary infections, while tobramycin was proven effective in suppressing chronic Pae airway infections in CF patients (Ramsey et al., 1999; Garnacho-Montero et al., 2003). However, in recent years a gradual decrease in baseline susceptibility of Pae to these last resort antibiotics was observed (Obritsch et al., 2004; Wi et al., 2017; Jain, 2018). As a refined understanding of the molecular regulatory circuits that contribute to resistance, tolerance and persister cell formation is key to develop new strategies/tools to combat Pae, we have employed RNA-seq and Ribo-seq in parallel to monitor gene expression responses of the clinical Pae isolate PA14 grown in synthetic cystic fibrosis sputum medium (SCFM) to inhibitory concentrations of colistin and tobramycin.

In addition to arn operon activation, which is known to result in reduced drug uptake, Pae responds to colistin by launching an anti-oxidative response, and by de-regulating genes belonging to the MexT and AlgU regulons. Concerning tobramycin, Pae seemingly goes through metabolic changes and envelope remodeling to prevent drug uptake, whereas its ramifications on translational processes are met with the stalled ribosome rescue response and the activation of type II toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

The clinical isolate Pae PA14 (Rahme et al., 1995) was used in all gene expression profiling experiments. Synthetic cystic fibrosis sputum medium (SCFM) was prepared as previously described (Palmer et al., 2007) with the modification specified in Tata et al. (2016). PA14 cells were grown aerobically in 500 ml SCFM at 37°C. At an OD600 of 1.7, the cultures were treated with inhibitory concentrations of colistin (8 μg/ml; Sigma) and tobramycin (64 μg/ml; Sigma), respectively, or water was added as a control. The cultures reached OD600 of 2 approximately 2 h after exposure to the antibiotics, as can be inferred from Supplementary Figure 1. 10 ml samples were withdrawn for RNA-seq analyses, while the remaining culture volume was used for the Ribo-seq experiments. The strain PA14ΔalgU was constructed as described in the Supplementary Text.

RNA-Seq

Total RNA was isolated from two biological replicates using the Trizol method (Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The samples were treated with DNase I (TURBOTM DNase, Thermo Scientific), followed by phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) extraction and ethanol precipitation. Ribosomal RNA was depleted with The Ribo-ZeroTM rRNA Removal Kit. The libraries were constructed using the NEBNext® UltraTM Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina®. Hundred bp single end sequence reads were generated using the Illumina HiSeq200 platform at the in house Next Generation Sequencing Facility (VBCF, Vienna, Austria1). Quality control assessment of the raw reads using FastqQC2 obviated further pre-processing. Sequencing adapter removal was performed with cutadap (Martin, 2011). Mapping of the samples against the PA14 reference genome (NCBI accession number NC_008463.1) was performed with Segemehl (Hoffmann et al., 2009) with default parameters. Reads mapping to rRNA or tRNA genes were discarded from all data and ignored for all follow-up analyses. The mapped sequencing data were prepared for visualization using the ViennaNGS tool box and visualized with the UCSC Genome Browser (Wolfinger et al., 2015). Reads per gene were counted using BEDTools (Quinlan and Hall, 2010) and the Refseq annotation of Pae (NC_002516.2). Differential gene expression analysis was performed with DESeq (Anders and Huber, 2010). All genes with a fold-change (FC) greater than ±2 and a multiple testing adjusted p-value below 0.05 were considered to be significantly modulated. The raw sequencing data were deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under accession number PRJEB41029.

Ribo-Seq

Ribosome profiling of elongating ribosomes (Ribo-seq; Ingolia et al., 2009) was performed with the same cultures as used for the RNA-seq analyses. Upon culture growth, the cells were treated for 10 min with chloramphenicol (300 μg/ml) to stop translation, and then harvested by centrifugation at 8,000 g for 15 min at 0°C. The cells were washed in 50 ml ice cold lysis buffer (10 mM MgOAc, 60 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM TRIS-HCl, pH 7.6) and again pelleted by centrifugation at 5000 g for 15 min at 4°C. The pellets were re-suspended in 1 ml ice cold lysis buffer containing 0.2% Triton X-100, 100 μg/ml chloramphenicol and 100 U/ml DNAse I, frozen in liquid nitrogen and cryogenically pulverized by repeated cycles of grinding in a pre-chilled mortar and freezing in a dry ice/ethanol bath. These lysates were centrifuged at 15,000 g for 30 min at 4°C to remove cellular debris. Hundred μl aliquots of the cleared lysates were treated with 4 μl of Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase, NEB) and 6 μl of the RiboLock RNase inhibitor (Thermo Scientific) for 1 h at 25°C with continuous shaking at 450 rpm. The lysates were then layered onto 10–40% linear sucrose density gradients in lysis buffer and centrifuged at 256,000 g for 3 h at 4°C. Five hundred μl gradient fractions were collected by continuously monitoring the absorbance at 260 nm. The RNA was extracted from fractions containing 70S ribosomes with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1), and precipitated with ethanol. The samples were then treated with DNase I (TURBOTM DNase, Thermo Scientific) and separated on a 15% polyacrylamide gel containing 8M urea. Ribosome protected mRNA fragments (ribosomal footprints) ranging in size of 20–40 nucleotides were removed and eluted from the polyacrylamide gel by overnight incubation in elution buffer (0.3 M NaOAc, 1 mM EDTA) at 4°C, which was followed by an additional round of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) extraction and ethanol precipitation. The quality of RNA samples was subsequently analyzed with a 2100 Bioanalyzer and an Aligned RNA 6000 Pico Kit (Aligned Technologies). The RNA was further processed into cDNA libraries with NEBNextTM Small RNA Library Prep Set for Illumina® and their quality was assessed with the 2100 Bioanalyzer and a High Sensitivity DNA Kit (Agilent Technologies). Pipin PrepTM was used to purify the 140–160 bp cDNA products which corresponded to adapter-ligated 20–40 nucleotide long ribosomal footprints. RNA sequencing and data processing was performed as described above. The raw sequencing data were deposited in the ENA under accession number PRJEB41027.

Results and Discussion

Quality Assessment and Data Analysis

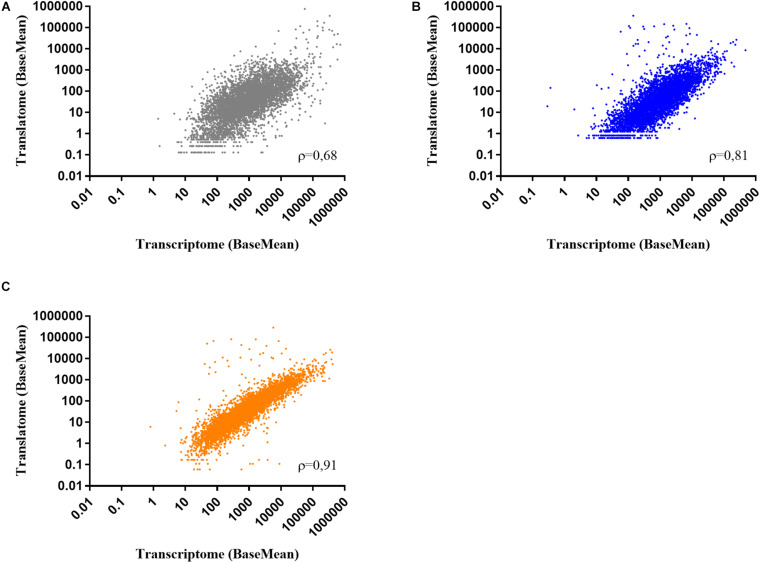

To determine the effect of colistin and tobramycin on gene expression, parallel RNA-seq and Ribo-seq experiments were performed with planktonically grown PA14. The cultures reached OD600 of 2 approximately 2 h after exposure to the antibiotics, as can be inferred from Supplementary Figure 1. As a control, total RNA and ribosome protected mRNA fragments (ribosomal footprints) were isolated from cultures grown without antibiotics. As the number of ribosomal footprint sequencing reads have been shown to correlate with those obtained from RNA-seq experiments (Ingolia et al., 2009), we first determined the representative gene expression correlations between RNA-seq and Ribo-seq. The number of RNA-seq and Ribo-seq sequencing reads were normalized (BaseMean), and the Spearman correlation value (ρ-value) between them was assessed for each condition (controls, colistin and tobramycin treatment). The correlation coefficient between the average Ribo-seq and RNA-seq BaseMean expression values was 0.68 for the control, 0.81 for colistin, and 0.91 for tobramycin treated samples, respectively (Figure 1). Similar ρ-values have been also reported by other studies (Blevins et al., 2018).

FIGURE 1.

Scatter plots showing the correlation between normalized RNA-seq and Ribo-seq sequencing reads (BaseMean) obtained from two biological replicates of (A) control, (B) colistin, and (C) tobramycin treated samples. ρ – Spearman correlation value.

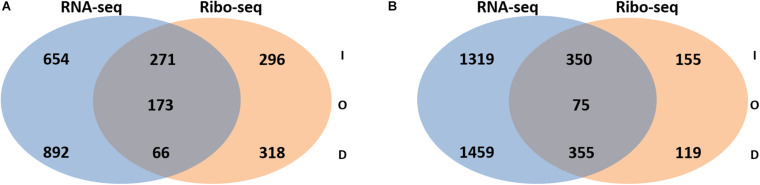

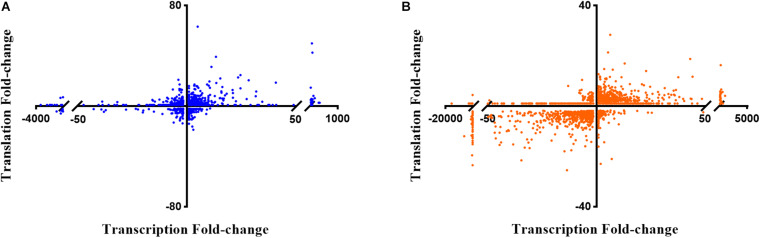

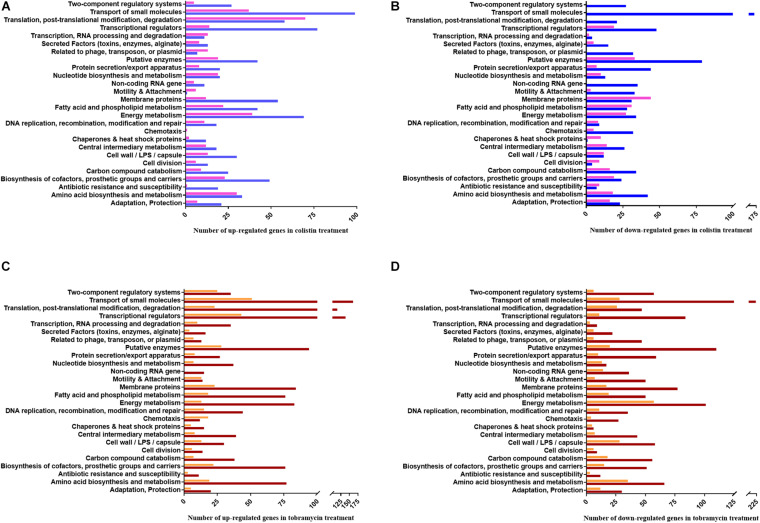

Next, the FC in transcript abundance between antibiotic treated and untreated samples was calculated. The following criteria were applied for differential gene expression analysis and interpretation: (i) only annotated genes deposited in the Pseudomonas genome database (Winsor et al., 2016) were considered for comparison; (ii) genes with a low expression level (less than 100 RNA-seq or 50 Ribo-seq reads) were disregarded; (iii) for all data sets a p-value (adjusted for multiple testing) of 0.05 was set as a threshold for significance and (iv) the change in FC had to exceed ± 2 for a given gene to be regarded as differentially expressed. When compared with the sequencing data acquired from the non-treated samples, 2056 and 3558 genes were found to be differentially abundant in RNA-seq after exposure to colistin and tobramycin, respectively, whereas that number in Ribo-seq amounted to 1124 and 1045 (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1). The scatter plots depicting the correlation between RNA-seq and Ribo-seq gene FC values are shown in Figure 3. Discrepancies in the number of de-regulated genes in RNA-seq when compared to Ribo-seq data have been reported before (Blevins et al., 2018), highlighting the importance of parallel application of these methods for assessment of gene expression. Interestingly, the vast majority of genes were significantly differentially expressed solely at the transcriptional or at the translational level by colistin and tobramycin. 1546 genes were de-regulated by colistin exclusively at the transcriptional level, whereas 614 genes were only affected at the translational level. In case of tobramycin 2778 genes showed FC values that exceeded ± 2 only in the RNA-seq data, while 274 genes were differentially expressed only in the Ribo-seq data. Moreover, 173 and 75 transcripts displayed opposite FC values in the two data sets after treatment with colistin and tobramycin, respectively (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1). These results showed that the differentially abundant transcripts observed with RNA-seq did not highly correlate with the outcome of the Ribo-seq analyses and vice versa. An explanation for this observation could be that the expression of these genes is post-transcriptionally regulated. In any case, the patterns of PseudoCAP functional class distribution of annotated transcripts with altered expression in response to colistin or tobramycin were similar for the transcriptome and translatome data (Figure 4).

FIGURE 2.

Venn diagram showing the number of transcripts with increased (I), decreased (D) or opposite (O) abundance in RNA-seq and Ribo-seq data obtained after (A) colistin treatment and (B) tobramycin treatment. For significance, only transcripts with a fold-change ≥ 2 or ≤ –2 and a multiple testing adjusted p-value ≤ 0.05 were considered. The corresponding transcripts and ribosomal footprints with increased, decreased and opposite abundance are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

FIGURE 3.

Scatter plots showing the correlation between gene expression fold-changes in RNA-seq and Ribo-seq data obtained after (A) colistin treatment and (B) tobramycin treatment. The X-axis corresponds to the RNA-seq data, or transcriptome, and the Y-axis to the Ribo-seq data, or translatome.

FIGURE 4.

PseudoCAP functional class distribution of annotated genes with altered expression in response to colistin or tobramycin. (A) Up-regulated and (B) down-regulated genes in colistin treated samples. Blue and pink bars indicate the number of de-regulated genes based on the RNA-seq and Ribo-seq data, respectively. (C) Up-regulated and (D) down-regulated genes in tobramycin treated samples. Brown and orange bars indicate the number of de-regulated genes based on the RNA-seq and Ribo-seq data, respectively.

Known Gene Expression Responses to Colistin and Tobramycin

To validate our data, we first scrutinized an assortment of genes known to be involved in maintenance of intrinsic and/or adaptive resistance of Pae toward colistin and tobramycin. In the case of colistin, we assessed the expression levels of the oprD, pmrA, and pmrB transcripts and of genes involved in the synthesis (i) and modification of LPS (such as the arn operon, pagL, lpxO2, lpxC, and galU), (ii) of spermidine (PA14_63110 – PA14_63120), (iii) of the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase family protein CprA (PA14_43311) and (iv) of the MexXY (PA14_38395-AmrB) and MexAB-OprM efflux pumps. As anticipated, the above mentioned genes were up-regulated upon colistin treatment, with the exception of oprD whose expression was down-regulated (Supplementary Table 2).

In the case of tobramycin, the abundance of genes known to be involved in (i) drug modification (aph), (ii) target binding inhibition (rsmE), (iii) extrusion (mexXY operon anti-repressor PA14_72210), (iv) maintenance of the cell membrane (groEL/ES, grpE, and htpX) as well as the genes encoding the AmgR/AmgS (OmpR/EnvZ) TCS were scrutinized. The transcription and/or translation of all the above mentioned genes was enhanced upon tobramycin treatment (Supplementary Table 2).

At a glance, energy metabolism-, translation-, and transcription- functional classes of genes were up-regulated after colistin exposure. On the other hand, colistin appears to negatively affect the abundance of mRNAs encoding functions involved in transport of small molecules, motility and attachment. Moreover, it translationally impaired expression of membrane protein genes (Figure 4).

The functional classes representing the majority of predominantly positively affected genes by tobramycin are related to transcriptional regulators, RNA processing and translation, whereas the most down-regulated gene functions are involved in energy metabolism, carbon compound catabolism and cell wall/LPS/capsule synthesis. Interestingly, motility and attachment genes were prominently down-regulated by tobramycin at the transcriptional level, whereas amino acid biosynthesis and metabolism genes were apparently more negatively affected at the translational level (Figure 4).

To find additional players and pathways involved in colistin and/or tobramycin resistance in Pae, we next took a closer look at all genes which displayed a ±10 FC in transcript abundance in antibiotic treated samples in the RNA-seq and/or Ribo-seq data sets (Supplementary Table 1).

Colistin Induces Oxidative Stress Response Genes

The accepted mode of action of polymyxins, i.e., causing a lesion in the IM, has been challenged by the finding that even supra-bactericidal colistin concentrations induced minor loss of intracellular components (O’Driscoll et al., 2018). However, polymyxins are also known to elicit oxidative damage in Bacteria through the production of ROS, such as superoxide O2–, hydrogenperoxide H2O2 and hydroxy radicals ⋅OH (El-Sayed Ahmed et al., 2020). Both O2– and H2O2 can injure proteins that possess iron–sulfur ([Fe–S]) clusters as cofactors. The maintenance of [Fe–S] proteins is of importance as they are required for many biological processes, including protein biosynthesis, respiration, central metabolism, photosynthesis, nitrogen fixation, DNA repair, RNA modification and gene regulation (Roche et al., 2013; Kimura and Suzuki, 2015). Polymyxin induced oxidative damage has been reported for Gram-negative and Gram-positive species, including Acinetobacter boumannii (Sampson et al., 2012), Pae (Brochmann et al., 2014; Lima et al., 2019), Bacillus subtilis, and the natural producer Paenibacillus polymyxa (Yu et al., 2019). Studies performed on the Gram-positive P. polymyxa provided a detailed explanation of how polymyxins might lead to ROS production. It has been hypothesized that colistin stimulates the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle through an increase in the production of isocitrate (icdA), α-ketoglutaric (sucB), and malate (mdh) dehydrogenases, which in turn leads to increased NADH production and enhanced respiration rates (Yu et al., 2019). Accordingly, the concentration of O2– surges intracellularly, where it can be converted to H2O2 by the superoxide dismutase (SOD). The sodA (Mn-SOD) and sodB (Fe-SOD) genes were up-regulated in P. polymyxa in the presence of colistin (Yu et al., 2017), while inactivation of sodB in the Gram-negative bacterium A. boumannii augmented its susceptibility to the same drug (Heindorf et al., 2014). Moreover, the involvement of sodC (CuZn-SOD) and catalase encoding katA genes in polymyxin resistance was observed in A. boumannii and Staphylococcus aureus, respectively (Antonic et al., 2013; Pournaras et al., 2014).

In our study, exposure of Pae to inhibitory concentration of colistin resulted in an up-regulation of genes involved in the oxidative stress response (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). These genes include aphF (Ochsner et al., 2000b), iscR (PA14_14710) (Romsang et al., 2014), the PA14_21570-PA14_21580-PA14_21590-PA14_21600 operon (Farrant et al., 2020), and PA14_22320 (Salunkhe et al., 2005). Next, we assessed whether additional genes required for alleviation of ROS were differentially expressed upon colistin treatment, but were initially not accounted for due to the set ±10 FC threshold. The catalase encoding katA and katB genes (Brown et al., 1995; Ma et al., 1999), as well as the gene encoding their regulator OxyR (Wei et al., 2012) were up-regulated at both the transcriptional and translational level (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). However, the alkyl hydroperoxide reductase gene ahpB (Ochsner et al., 2000b) and the superoxide dismutase gene sodB (Hassett et al., 1993, 1995) were only found to be up-regulated in the RNA-seq data (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Moreover, the soxR gene and the majority of genes regulated by the redox-responsive SoxR regulator (mexG, mexH, mexI, PA14_16310, and PA14_35160) (Palma et al., 2005) displayed an increased transcript and ribosomal footprint abundance (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Gene expression response of PA14 grown in the presence of colistin versus untreated control.

| Gene name | Gene ID | Gene product | RNA-seq | Ribo-seq |

| FC1 | FC | |||

| Oxidative stress response genes | ||||

| ahpF | PA14_01720 | Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase | 52.542 | 4.99 |

| katA | PA14_09150 | Catalase | 8.45 | 4.75 |

| mexI | PA14_09520 | RND efflux transporter | 2.31 | 2.5 |

| mexH | PA14_09530 | RND efflux membrane fusion protein | 3.36 | ND3 |

| mexG | PA14_09540 | Hypothetical protein | 4.7 | 4 |

| PA14_14710 | PA14_14710 | Rrf2 family protein | 9.31 | 17.2 |

| PA14_16310 | PA14_16310 | MFS permease | 22.54 | 3.98 |

| PA14_21570 | PA14_21570 | Hypothetical protein | 12.84 | 8.05 |

| PA14_21580 | PA14_21580 | Hypothetical protein | 15.15 | 6.37 |

| PA14_21590 | PA14_21590 | Hypothetical protein | 10.72 | 9 |

| PA14_21600 | PA14_21600 | Hypothetical protein | 9.95 | 6.61 |

| PA14_22320 | PA14_22320 | Hypothetical protein | 10.1 | 3.97 |

| PA14_35160 | PA14_35160 | Hypothetical protein | 4.89 | 2.74 |

| soxR | PA14_35170 | Redox-sensing activator of soxS | 3.86 | 3.02 |

| PA14_53300 | PA14_53300 | Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase AhpB | 106.45 | ND |

| sodB | PA14_56780 | Cation-transporting P-type ATPase | 9.57 | ND |

| katB | PA14_61040 | Superoxide dismutase | 9.26 | 2.91 |

| oxyR | PA14_70560 | LysR family transcriptional regulator | 2.43 | 2.72 |

| Iron homeostasis genes | ||||

| exbB1 | PA14_02500 | Transport protein ExbB | –2.93 | X4 |

| exbD1 | PA14_02510 | Transport protein ExbD | –10.34 | X |

| pchA | PA14_09210 | Salicylate biosynthesis isochorismate synthase | –3.35 | 17.28 |

| pchB | PA14_09220 | Isochorismate-pyruvate lyase | –3.09 | 13.26 |

| pchC | PA14_09230 | Pyochelin biosynthetic protein PchC | –2.35 | 6.34 |

| pchD | PA14_09240 | Pyochelin biosynthesis protein PchD | –6.01 | ND |

| pchR | PA14_09260 | Transcriptional regulator PchR | ND | 4.48 |

| pchE | PA14_09270 | Dihydroaeruginoic acid synthetase | ND | 6.47 |

| pchF | PA14_09280 | Pyochelin synthetase | –2.56 | 11.04 |

| pchG | PA14_09290 | Pyochelin biosynthetic protein PchG | –2.25 | 13.01 |

| pchH | PA14_09300 | ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | –3.52 | 9.05 |

| pchI | PA14_09320 | ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | –2.91 | 13.46 |

| fptA | PA14_09340 | Fe(III)-pyochelin outer membrane receptor | –4.70 | 7.57 |

| PA14_20000 | PA14_20000 | Transmembrane sensor | –11.29 | X |

| hasR | PA14_20010 | Heme uptake outer membrane receptor HasR | –32.17 | X |

| hasAp | PA14_20020 | Heme acquisition protein HasAp | –1282.44 | X |

| hasD | PA14_20030 | Transport protein HasD | –38.16 | X |

| hasE | PA14_20040 | Metalloprotease secretion protein | –56.02 | X |

| hasF | PA14_20050 | Outer membrane protein | –27.96 | X |

| pvdS | PA14_33260 | Extracytoplasmic-function sigma-70 factor | –12.48 | X |

| pvdG | PA14_33270 | Protein PvdG | –5.48 | X |

| pvdL | PA14_33280 | Peptide synthase | –15.82 | X |

| PA14_33420 | PA14_33420 | Hydrolase | –1.98 | X |

| PA14_33610 | PA14_33610 | Peptide synthase | –14.69 | X |

| pvdJ | PA14_33630 | Protein PvdJ | –31.99 | X |

| pvdD | PA14_33650 | Pyoverdine synthetase D | –16.41 | X |

| fpvA | PA14_33680 | Ferripyoverdine receptor | –5.16 | X |

| pvdE | PA14_33690 | Pyoverdine biosynthesis protein PvdE | –4.05 | X |

| pvdF | PA14_33700 | Pyoverdine synthetase F | –2.71 | X |

| pvdO | PA14_33710 | Protein PvdO | –10.04 | X |

| pvdN | PA14_33720 | Protein PvdN | –6.41 | X |

| PA14_33730 | PA14_33730 | Dipeptidase | –3.91 | X |

| opmQ | PA14_33750 | Outer membrane protein | –4.9 | X |

| PA14_33760 | PA14_33760 | ABC transporter ATP-binding protein/permease | –3.12 | X |

| PA14_33780 | PA14_33780 | Transmembrane sensor | –1.89 | X |

| pvdA | PA14_33810 | L-ornithine N5-oxygenase | –10.84 | X |

| pvdQ | PA14_33820 | Penicillin acylase-related protein | –8.57 | X |

| feoC | PA14_56670 | Hypothetical protein | –9.56 | X |

| feoB | PA14_56680 | Ferrous iron transport protein B | –38.95 | X |

| feoA | PA14_56690 | Ferrous iron transport protein A | –68.23 | X |

| MexT regulon genes | ||||

| PA14_22420 | PA14_22420 | Hypothetical protein | 10.58 | 14.6 |

| PA14_22740 | PA14_22740 | Hypothetical protein | 20.99 | 12.81 |

| PA14_28410 | PA14_28410 | Hypothetical protein | 21.19 | 10.47 |

| mexF | PA14_32390 | RND multidrug efflux transporter MexF | 2.28 | 4.37 |

| mexE | PA14_32400 | RND multidrug efflux membrane fusion protein MexE | 9.8 | 4.98 |

| PA14_32480 | PA14_32480 | Hypothetical protein | 3.72 | 4.726 |

| PA14_32490 | PA14_32490 | Hypothetical protein | 5.96 | 5.49 |

| PA14_39060 | PA14_39060 | Hypothetical protein | 28.44 | 20.56 |

| PA14_39420 | PA14_39420 | Hypothetical protein | 18.31 | 9.99 |

| PA14_41990 | PA14_41990 | Hypothetical protein | 2.26 | 10.38 |

| PA14_56620 | PA14_56620 | Hypothetical protein | 31.66 | 7.99 |

| PA14_56640 | PA14_56640 | MFS transporter | 27.52 | 5.7 |

| PA14_64530 | PA14_64530 | Hypothetical protein | 195.2 | 6.35 |

| Anaerobic respiratory chain genes | ||||

| nirN | PA14_06650 | c-type cytochrome | 70.18 | ND |

| nirE | PA14_06660 | Uroporphyrin-III c-methyltransferase | 69.22 | 2.2 |

| nirJ | PA14_06670 | Heme d1 biosynthesis protein NirJ | 41.09 | ND |

| nirH | PA14_06680 | Hypothetical protein | 39.43 | ND |

| nirG | PA14_06690 | Transcriptional regulator | 49.08 | ND |

| nirL | PA14_06700 | Heme d1 biosynthesis protein NirL | 37.8 | ND |

| PA14_06710 | PA14_06710 | Transcriptional regulator | 29.29 | ND |

| nirF | PA14_06720 | Heme d1 biosynthesis protein NirF | 21.94 | ND |

| nirC | PA14_06730 | c-type cytochrome | 62.8 | ND |

| nirM | PA14_06740 | Cytochrome c-551 | 67.09 | ND |

| nirS | PA14_06750 | Nitrite reductase | 24.69 | ND |

| nirQ | PA14_06770 | Regulatory protein NirQ | 11.98 | ND |

| nirO | PA14_06790 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit | 39.7 | ND |

| PA14_06800 | PA14_06800 | Hypothetical protein | 119.94 | 5.39 |

| norC | PA14_06810 | Nitric-oxide reductase subunit C | 87.15 | 3.2 |

| norB | PA14_06830 | Nitric-oxide reductase subunit B | 134.06 | 3.35 |

| norD | PA14_06840 | Dinitrification protein NorD | 328.15 | 2.77 |

| narK1 | PA14_13750 | Nitrite extrusion protein 1 | –59.67 | X |

| narK2 | PA14_13770 | Nitrite extrusion protein 2 | –22.48 | X |

| narG | PA14_13780 | Respiratory nitrate reductase alpha subunit | –2.33 | X |

| nosL | PA14_20150 | NosL protein | 56.67 | 3.16 |

| nosY | PA14_20170 | NosY protein | 94.96 | 3.06 |

| nosF | PA14_20180 | NosF protein | 93.83 | 3.93 |

| nosD | PA14_20190 | Copper ABC transporter periplasmic substrate-binding protein | 34.68 | 3.5 |

| nosZ | PA14_20200 | Nitrous-oxide reductase | 61.22 | ND |

| nosR | PA14_20230 | Regulatory protein NosR | 73 | ND |

| anr | PA14_44490 | Transcriptional regulator Anr | –2.36 | –2.32 |

| Efflux pump genes | ||||

| mexJ | PA14_16800 | Efflux transmembrane protein | 15.43 | 22.07 |

| mexK | PA14_16820 | Efflux transmembrane protein | 6.19 | 12.07 |

| oprJ | PA14_60820 | Outer membrane protein OprJ | 6.19 | X |

| mexD | PA14_60830 | Multidrug efflux RND transporter MexD | 4.32 | 7.02 |

| mexC | PA14_60850 | Multidrug efflux RND membrane fusion protein | 5.32 | 14.65 |

| Genes known to be up-regulated by polymyxins or in polymyxin | ||||

| resistant Pae strains | ||||

| PA14_24360 | PA14_24360 | Hypothetical protein | 13.58 | 18.41 |

| PA14_34170 | PA14_34170 | Hypothetical protein | 95.8 | 49.9 |

| PA14_41280 | PA14_41280 | Beta-lactamase | 111.9 | 42.62 |

| PA14_41290 | PA14_41290 | Hypothetical protein | 144.84 | X |

| PA14_63220 | PA14_63220 | Hypothetical protein | 13.35 | 39.33 |

1FC, fold-change, p-value ≤ 0.05. 2Genes with FC ≤ –10 or ≥10 are represented in bold. 3ND, not differentially expressed, –2 ≤ FC ≤ 2 and/or p-value ≥ 0.05. 4X, not efficiently translated in the control and antibiotic treated samples, Ribo-seq BaseMean ≤ 50.

The toxicity of ROS-generating agents is magnified by ferrous ions (Fe2+) through the Fenton reaction (Kohanski et al., 2007; Yeom et al., 2010), wherein H2O2 is oxidized by Fe2+ to generate OH radicals. These can inactivate enzymes and cause DNA and membrane damage, leading to growth arrest and ultimately to cell death (Yeom et al., 2010). Thus, Bacteria generally establish a tight control on expression of iron homeostasis genes. For instance, in P. polymyxa the levels of the transcriptional regulator Fur, which represses iron acquisition genes, are increased upon colistin treatment (Yu et al., 2017). Fe2+ can be directly taken up from environment or it can be generated through reduction of free intracellular ferric (Fe3+) ions bound to siderophores such as pyoveridine (PVD) or pyochelin (PCH), to iron-sulfur ([Fe–S]) cluster proteins or to heme (Ochsner et al., 2000a; Ratledge and Dover, 2000; Wandersman and Delepelaire, 2004; Cartron et al., 2006). Therefore, we also scrutinized the levels of transcripts encoding genes for iron acquisition and storage upon exposure to colistin. As judged from the RNA-seq data, the genes required for PVD biosynthesis and transport (Lamont and Martin, 2003), for heme uptake (has locus; Ochsner et al., 2000a), the Feo system of Fe2+ uptake and the TonB2-ExbB1-ExbD1 complex (Zhao and Poole, 2000), which serves as an energy coupler for active iron transport across the outer membrane, were down-regulated (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). In addition, the majority of these genes was apparently not efficiently translated in neither the control nor in the colistin treated samples (≤50 Ribo-seq reads). Visual inspection of their sequencing profiles in the UCSC Genome Browser (Wolfinger et al., 2015) revealed a very low ribosomal coverage (Supplementary Figure 2), which might be caused by the applied iron rich culturing conditions. For example, siderophore synthesis in Pseudomonas sp. is fully inhibited at >4–10 μM iron (Meyer, 1978; Dumas et al., 2013), a concentration far below of what was used in our experimental setup (100 μM FeSO4). Counterintuitively, the genes for pyochelin synthesis and uptake are apparently translated in the presence of colistin (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). As pyochelin has a weaker affinity for iron when compared with pyoveridine (Dumas et al., 2013), ongoing synthesis could be necessary to meet sufficient metabolic requirements for iron.

In most Gram-negative Bacteria the ferric uptake regulator Fur complexed with Fe2+ is responsible for preventing the synthesis of PVD and PCH in iron replete conditions (Ochsner and Vasil, 1996; Vasil and Ochsner, 1999). Analogously to P. polymixa, fur was slightly up-regulated in both the RNA-seq and Ribo-seq data (Supplementary Table 1). Therefore, an explanation for the apparent translation of the PCH genes remains elusive.

An additional link between colistin resistance and iron homeostasis can be found in the increased synthesis of PA14_04180 (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1), a putative periplasmic protein with a bacterial oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide-binding (OB-fold) domain, which can bind cationic ligands (Ginalski et al., 2004). Gene PA14_04180 was found to be regulated by the calcium responsive TCS CarS/CarR and the ferrous iron responsive BqsS/BqsR TCS (Kreamer et al., 2012; Guragain et al., 2016). The BqsS/BqsR system contributes to cationic stress tolerance as it is regulating the expression of several genes with known or predicted functions in polyamine biosynthesis/transport or polymyxin resistance in Pae (i.e., arnB, oprH, and PA14_63110) (Kreamer et al., 2015). Moreover, a periplasmic OB-fold protein OmdA, similar to PA14_04180, is controlled by the PmrA/PmrB TCS and was found to confer resistance to polymyxin B (Pilonieta et al., 2009).

In contrast to P. polymyxa (Yu et al., 2019), we did not notice an up-regulation of TCA cycle genes or drastic changes in expression of the NADH oxidase family genes (Supplementary Table 1). Alternatively, it has been hypothesized that O2– production could be induced in Gram-negative Bacteria during transit of polymyxin molecules through the cell envelope (Kohanski et al., 2007; El-Sayed Ahmed et al., 2020) and via inhibition of type II NADH-quinone oxidoreductases (NDH-2) (Deris et al., 2014).

Denitrification Pathway Genes Are De-Regulated in the Presence of Colistin

The transcripts encoding for enzymes required for the denitrification pathway (Schreiber et al., 2007), which include the nitrite reductase encoding nir-operon, the nitric oxide reductase encoding nor-operon and the nitrous dioxide reductase encoding nos-operon, were highly abundant relative to their representation in cells growing in the absence of colistin. Similar trends in expression were observed in the Ribo-seq data set, albeit not to the same degree (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Surprisingly, the master regulator of the denitrification pathway ANR and the genes of the nar-operon, which encode nitrate reductase, a complex that catalyzes the first step of denitrification, were down-regulated after colistin treatment (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). It is possible that the ParR/ParS TCS positively regulates several genes involved in anaerobic respiration (nirC, norC, norB, nosZ, and nosL) (Fernández et al., 2010), however the reasons for activating the anaerobic respiratory chain in presence of colistin remain to be elucidated.

Colistin Induced Up-Regulation of the MexT Regulon

Colistin caused a significant up-regulation of the PA14 genes PA14_22420, PA14_22740, PA14_28410, mexF, mexE, PA14_32480, PA14_32490, PA14_39060, PA14_39420, PA14_41990, PA14_56620, PA14_56640, and PA14_64530 (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1), all of which belong to the MexT regulon (Tian et al., 2009a; Hill et al., 2019). MexT is a transcriptional regulator of the LysR family known to control the expression of pathogenicity, virulence and antibiotic resistance determinants in Pae (Köhler et al., 1997a,b, 1999; Tian et al., 2009a; Huang et al., 2019). MexT regulates gene expression either directly through binding to the promoter region of distinct target genes, or indirectly through the activation of the MexEF-OprN efflux pump (Tian et al., 2009a,b; Olivares et al., 2012). Furthermore, MexT is a redox-responsive transcriptional activator implicated in diamide stress tolerance, in defense against the innate immune system-derived oxidant hypochlorous acid and against nitrosative stress (Fetar et al., 2011; Fargier et al., 2012; Farrant et al., 2020). Thus, the observed activation of MexT regulated genes might be a result of a defense mechanism being triggered against oxidative stress that arises as a consequence of colistin activity. As mentioned above, the denitrification pathway (nir, nor, and nos genes) was up-regulated in the presence of colistin (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1), hence it is tempting to speculate whether this antibiotic can additionally inflict nitrosative stress to Pae. Moreover, Wang et al. (2013) showed that the deletion of parR and parS in Pae strain PAO1 negatively impacts the transcript abundance of genes belonging to the MexT regulon, without affecting the expression levels of mexT.

Colistin Impacts the AlgU Regulon

Schulz et al. (2015) predicted that the primary regulon of the alternative sigma factor σ22 (AlgU or AlgT) in PA14 comprises 341 genes, while their mRNA profiling approach uncovered 222 genes that were down-regulated in an algU deletion- and up-regulated in an algU overexpressing strain, or vice versa. Our RNA-seq and Ribo-seq data sets show that colistin caused a change in expression at the transcriptional and/or the translational level of 141 out of those 222 AlgU-dependent genes (Supplementary Table 3). Envelope stress inducing agents cause proteolytic degradation of the AlgU anti-sigma factor MucA through regulated intramembrane proteolysis (RIP), which leads to the release of AlgU from the IM, and ultimately to the activation of the AlgU regulon (Wood et al., 2006; Damron and Goldberg, 2012). It is possible that the genes controlled by AlgU play a significant role in colistin susceptibility in Pae, as polymyxins have long been implicated in triggering envelope stress in Gram-negative Bacteria. As the transcription of algU itself was only slightly increased (2.65- fold) upon exposure to colistin (Supplementary Table 1), the regulation of the AlgU activity through RIP might explain the observed alterations in expression of the AlgU regulon. In view of our studies, we compared the susceptibility toward colistin of PA14 with an isogenic in frame algU deletion mutant. When compared with the PA14 WT strain, the minimal inhibitory concentration of colistin for PA14ΔalgU was approximately fourfold reduced (Supplementary Figure 3), showing that the AlgU-dependent response counteracts the deleterious effects of colistin. In line with our observations, Murray et al. (2015) reported that a transposon insertion in algU affects the fitness of Pae in the presence of polymyxin B.

Colistin Affects Multiple Efflux-Pump Genes

Besides the aforementioned MexXY-OprM, MexAB-OprM, MexEF-OprN, and MexGHI-OpmD efflux pumps, a strong colistin-dependent induction of the mexCD-oprJ and mexJK operons was observed (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Expression of mexCD-oprJ was shown to be enhanced by polymyxin B in an AlgU-dependent manner (Fraud et al., 2008), whereas the MexJK efflux system has so far not been linked to polymyxin susceptibility.

Tobramycin Down-Regulates Amino Acid Catabolism and Lower Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle Genes

The insertional inactivation of the genes encoding the Nuo and Nqr dehydrogenases was shown to increase tobramycin resistance of Pae (Schurek et al., 2008; Kindrachuk et al., 2011). It was hypothesized that their inactivation causes a reduction in the proton motive force and energy production, hence limiting the active uptake of tobramycin. The nuo and nqr genes were among the most down-regulated genes in the RNA-seq and Ribo-seq data after tobramycin treatment (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1).

TABLE 2.

Gene expression response of PA14 grown in the presence of tobramycin versus untreated control.

| Gene name | Gene ID | Gene product | RNA-seq | Ribo-seq |

| FC1 | FC | |||

| Energy metabolism and tricarboxylic acid cycle cycle | ||||

| PA14_06800 | PA14_06800 | Hypothetical protein | 18.422 | X3 |

| ldh | PA14_19870 | Leucine dehydrogenase | –13.38 | –2.23 |

| PA14_19900 | PA14_19900 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component subunit alpha | –104.77 | –4.45 |

| pdhB | PA14_19910 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component. beta chain | –94.26 | –2.53 |

| PA14_19920 | PA14_19920 | Branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase subunit E2 | –78.9 | X |

| nqrA | PA14_25280 | Na(+)-translocating NADH-quinone reductase subunit A | 6.06 | ND4 |

| nqrB | PA14_25305 | Na(+)-translocating NADH-quinone reductase subunit B | ND | –4.6 |

| nqrC | PA14_25320 | Na(+)-translocating NADH-quinone reductase subunit C | –2.08 | –2.66 |

| nqrD | PA14_25330 | Na(+)-translocating NADH-quinone reductase subunit D | –5.14 | –3.25 |

| nqrE | PA14_25340 | Na(+)-translocating NADH-quinone reductase subunit E | –7.06 | –2.51 |

| nqrF | PA14_25350 | Na(+)-translocating NADH-quinone reductase subunit F | –9.6 | ND |

| nuoN | PA14_29850 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit N | –20.61 | –13.71 |

| nuoM | PA14_29860 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit M | –24.8 | –3.99 |

| nuoL | PA14_29880 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit L | –25.56 | –3.4 |

| nuoK | PA14_29890 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit K | –8 | –6.97 |

| nuoJ | PA14_29900 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit J | –5.16 | –15.98 |

| nuoI | PA14_29920 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit I | –9.55 | –13.6 |

| nuoH | PA14_29930 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit H | –10 | –4.88 |

| nuoG | PA14_29940 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit G | –46.39 | –8.11 |

| nuoF | PA14_29970 | NADH dehydrogenase I subunit F | –13.36 | –8.16 |

| nuoE | PA14_29980 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit E | –13.55 | –5.35 |

| icd | PA14_30190 | Iisocitrate dehydrogenase | –3.09 | ND |

| sucD | PA14_43940 | Succinyl-CoA synthetase subunit alpha | –9.39 | –3.27 |

| sucC | PA14_43950 | Succinyl-CoA synthetase subunit beta | –3.73 | ND |

| lpdG | PA14_43970 | Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase | –16.47 | –5.26 |

| sucB | PA14_44000 | Dihydrolipoamide succinyltransferase | –10.98 | –9.15 |

| sucA | PA14_44010 | 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase E1 | –4.27 | –4.12 |

| PA14_53970 | PA14_53970 | Aconitate hydratase | –18.05 | –8.09 |

| Phenylalanine/Tyrosine catabolism | ||||

| fahA | PA14_38530 | Fumarylacetoacetase | –30.98 | –2.32 |

| maiA | PA14_38550 | Maleylacetoacetate isomerase | –48.44 | –3.57 |

| phhB | PA14_53000 | Pterin-4-alpha-carbinolamine dehydratase | –14.76 | –2.47 |

| phhC | PA14_53010 | Aromatic amino acid aminotransferase | –13.94 | –2.78 |

| Arginine catabolism | ||||

| arcD | PA14_68300 | Arginine/ornithine antiporter | –49.29 | 2.29 |

| arcA | PA14_68330 | Arginine deiminase | –77.18 | –2.12 |

| arcB | PA14_68340 | Ornithine carbamoyltransferase | –137.35 | –4.19 |

| Leucin/Valine/Isoleucin degradation and biosynthesis | ||||

| lpdV | PA14_35490 | Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase | –104.5 | –6.56 |

| bkdB | PA14_35500 | Branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase subunit E2 | –91.67 | –5.51 |

| bkdA2 | PA14_35520 | 2-oxoisovalerate dehydrogenase subunit beta | –104.31 | –4.84 |

| bkdA1 | PA14_35530 | 2-oxoisovalerate dehydrogenase subunit alpha | –5.23 | X |

| gnyR | PA14_38430 | Regulatory gene of gnyRDBHAL cluster. GnyR | –12.88 | ND |

| gnyD | PA14_38440 | Citronelloyl-CoA dehydrogenase. GnyD | –30.42 | –2.32 |

| gnyB | PA14_38460 | Acyl-CoA carboxyltransferase subunit beta | –27.71 | X |

| gnyH | PA14_38470 | Gamma-carboxygeranoyl-CoA hydratase | –33.85 | –3.73 |

| gnyA | PA14_38480 | Alpha subunit of geranoyl-CoA carboxylase. GnyA | –26.11 | X |

| ilvA2 | PA14_47100 | Threonine dehydratase | 24.7 | 7.68 |

| Peptidoglycan biosynthesis | ||||

| ddl | PA14_57320 | D-alanine–D-alanine ligase | –151.66 | –8.63 |

| murC | PA14_57330 | UDP-N-acetylmuramate–L-alanine ligase | –78.75 | –9.99 |

| murG | PA14_57340 | UDPdiphospho-muramoylpentapeptide beta-N-acetylglucosaminyl transferase | –44.2 | –8.27 |

| murD | PA14_57370 | UDP-N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanyl-D-glutamate synthetase | –46.8 | –10.56 |

| mraY | PA14_57380 | Phospho-N-acetylmuramoyl-pentapeptide-transferase | –13.67 | –2.18 |

| murF | PA14_57390 | UDP-N-acetylmuramoylalanyl-D-glutamyl-2.6-diaminopimelate–D-alanyl-D-alanine ligase | –11.12 | X |

| murE | PA14_57410 | UDP-N-acetylmuramoylalanyl-D-glutamate–2. 6-diaminopimelate ligase | –55.53 | –9.29 |

| rmlC | PA14_68210 | dTDP-4-dehydrorhamnose 3.5-epimerase | –12.92 | –3.34 |

| Glycogen metabolism | ||||

| glgA | PA14_36570 | Glycogen synthase | –3.09 | –5.06 |

| PA14_36580 | PA14_36580 | Glycosyl hydrolase | –19.03 | –11.25 |

| PA14_36590 | PA14_36590 | 4-alpha-glucanotransferase | –34.5 | –21.54 |

| PA14_36605 | PA14_36605 | Maltooligosyl trehalose synthase | –27.97 | –10.78 |

| PA14_36620 | PA14_36620 | Hypothetical protein | –44.57 | –10.58 |

| PA14_36630 | PA14_36630 | Glycosyl hydrolase | –25.56 | –6.53 |

| glgB | PA14_36710 | Glycogen branching protein | –38.34 | –15.21 |

| PA14_36730 | PA14_36730 | Trehalose synthase | –30.78 | –16.68 |

| PA14_36740 | PA14_36740 | Hypothetical protein | –4.77 | –5.04 |

| glgP | PA14_36840 | Glycogen phosphorylase | –5.98 | –2.93 |

| PA14_36850 | PA14_36850 | Hypothetical protein | –2.26 | –2.9 |

| Pathogenicity and virulence | ||||

| tssL1 | PA14_00925 | Hypothetical protein | –17.71 | X |

| tssk1 | PA14_00940 | Hypothetical protein | –6.38 | –4.32 |

| tssJ1 | PA14_00960 | Lipoprotein | –12.26 | –3.67 |

| PA14_00960 | PA14_00970 | Hypothetical protein | –33.07 | –2.84 |

| pilJ | PA14_05360 | Twitching motility protein PilJ | –2.63 | ND |

| pilK | PA14_05380 | Methyltransferase PilK | –2.59 | ND |

| chpA | PA14_05390 | ChpA | –11.54 | –4.98 |

| PA14_05400 | PA14_05400 | Methylesterase | –20.38 | –3.72 |

| PA14_34000 | PA14_34000 | HsiH3 | –23.95 | –5.54 |

| stk1 | PA14_42880 | Stk1 | –2.19 | X |

| stp1 | PA14_42890 | Stp1 | –5.56 | –3.6 |

| PA14_42900 | PA14_42900 | IcmF2 | –3.59 | –2.57 |

| PA14_42910 | PA14_42910 | DotU2 | –11.99 | –3.08 |

| PA14_42920 | PA14_42920 | HsiJ2 | –7.75 | –3.42 |

| PA14_42940 | PA14_42940 | Lip2.2 | –20.14 | –3.56 |

| PA14_42950 | PA14_42950 | Fha2 | –25.63 | –5.86 |

| PA14_42960 | PA14_42960 | Lip2.2 | –77.39 | X |

| PA14_42970 | PA14_42970 | Sfa2 | –13.89 | –6.03 |

| PA14_42980 | PA14_42980 | ClpV2 | –10.86 | –5.68 |

| PA14_42990 | PA14_42990 | HsiH2 | –10.56 | –4.18 |

| PA14_43000 | PA14_43000 | HsiG2 | –14.05 | –3.6 |

| PA14_43020 | PA14_43020 | Hypothetical protein | –10.04 | –3.57 |

| PA14_43030 | PA14_43030 | HsiC2 | –4.85 | X |

| flhB | PA14_45720 | Flagellar biosynthesis protein FlhB | –5.62 | X |

| fliR | PA14_45740 | Flagellar biosynthesis protein FliR | –8.13 | X |

| fliQ | PA14_45760 | Flagellar biosynthesis protein FliQ | –10.6 | X |

| fliP | PA14_45770 | Flagellar biosynthesis protein FliP | –6.41 | X |

| fliN | PA14_45790 | Flagellar motor switch protein | –2.05 | X |

| flgK | PA14_50360 | Flagellar hook-associated protein FlgK | –75.19 | –3.47 |

| flgJ | PA14_50380 | Flagellar rod assembly protein/muramidase FlgJ | –9.17 | –4.58 |

| flgI | PA14_50410 | Flagellar basal body P-ring protein | –6.22 | X |

| flgH | PA14_50420 | Flagellar basal body L-ring protein | –3.99 | X |

| flgG | PA14_50430 | Flagellar basal body rod protein FlgG | ND | 2.13 |

| flgF | PA14_50440 | Flagellar basal body rod protein FlgF | ND | 3.54 |

| pqsE | PA14_51380 | Quinolone signal response protein | –80.7 | –2.98 |

| pqsD | PA14_51390 | 3-oxoacyl-ACP synthase | –90.01 | –5.86 |

| pqsC | PA14_51410 | PqsC | –44.86 | –4.06 |

| pqsB | PA14_51420 | PqsB | –20.71 | –2.34 |

| pqsA | PA14_51430 | PqsA | –3.73 | X |

| PA14_55780 | PA14_55780 | Phosphate transporter | –46.70 | X |

| PA14_55790 | PA14_55790 | Two-component sensor | –15.49 | –2.70 |

| PA14_55800 | PA14_55800 | Hypothetical protein | –2.21 | X |

| PA14_55810 | PA14_55810 | Hypothetical protein | –2.73 | –2.00 |

| PA14_55820 | PA14_55820 | Two-component response regulator | –25.16 | X |

| PA14_55840 | PA14_55840 | Hypothetical protein | –84.76 | X |

| PA14_55850 | PA14_55850 | Hypothetical protein | –68.52 | X |

| PA14_55860 | PA14_55860 | Pilus assembly protein | –98.84 | X |

| PA14_55880 | PA14_55880 | Hypothetical protein | –105.85 | X |

| cpaF2 | PA14_55890 | Hypothetical protein | –111.85 | X |

| PA14_55900 | PA14_55900 | Type II secretion system protein | –36.82 | –9.16 |

| PA14_55920 | PA14_55920 | Hypothetical protein | –15.84 | –2.00 |

| PA14_55930 | PA14_55930 | Type II secretion system protein | –2.75 | ND |

| PA14_55940 | PA14_55940 | Pilus assembly protein | –8.25 | –7.96 |

| pilC | PA14_58760 | Type 4 fimbrial biogenesis protein pilC | –2.41 | ND |

| pilD | PA14_58770 | Type 4 prepilin peptidase PilD | –11.48 | ND |

| coaE | PA14_58780 | Dephospho-CoA kinase | ND | 2.48 |

| fimU | PA14_60280 | Type 4 fimbrial biogenesis protein FimU | –2.46 | ND |

| pilW | PA14_60290 | Type 4 fimbrial biogenesis protein PilW | –11.99 | X |

| pilX | PA14_60300 | Type 4 fimbrial biogenesis protein PilX | –9.12 | X |

| pilY1 | PA14_60310 | Type 4 fimbrial biogenesis protein PilY1 | –4.06 | ND |

| pilE | PA14_60320 | Type 4 fimbrial biogenesis protein PilE | –3.43 | –2.53 |

| PA14_65520 | PA14_65520 | Hypothetical protein | –21.34 | –3.44 |

| PA14_65540 | PA14_65540 | Hypothetical protein | –4.26 | X |

| estA | PA14_67510 | Esterase EstA | –11.29 | –2.17 |

| ABC transporters and Sha antiporter | ||||

| opuCA | PA14_13580 | ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | –28.83 | –7.05 |

| opuCB | PA14_13590 | ABC transporter permease | –6 | –4.83 |

| opuCD | PA14_13600 | ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | –4.73 | –4.41 |

| nppA2 | PA14_41130 | ABC transporter substrate-binding protein NppA2 | –1.97 | X |

| nppB | PA14_41140 | Peptidyl nucleoside antibiotic ABC transporter permease NppB | –10.23 | X |

| nppC | PA14_41150 | Peptidyl nucleoside antibiotic ABC transporter permease NppC | –30.15 | –3.71 |

| nppD | PA14_41160 | Peptidyl nucleoside antibiotic ABC transporter ATP-binding protein NppD | –22.25 | –4.98 |

| fabI | PA14_41170 | NADH-dependent enoyl-ACP reductase | –21.89 | –5.27 |

| phaG | PA14_50680 | ShaA | –44.11 | –3.99 |

| phaF | PA14_50690 | ShaB | –29.33 | –3.77 |

| phaE | PA14_50700 | ShaC | –12.23 | –2.9 |

| phaD | PA14_50710 | ShaD | –7.08 | –5.88 |

| phaC | PA14_50720 | ShaE | –8.48 | –7.78 |

| dppC | PA14_58450 | Dipeptide ABC transporter permease DppC | –13.03 | –3.55 |

| dppD | PA14_58470 | Dipeptide ABC transporter ATP-binding protein DppD | –34.43 | –10.45 |

| dppF | PA14_58490 | Dipeptide ABC transporter ATP-binding protein DppF | –21.5 | –4.19 |

| Transcription and translation | ||||

| tufB | PA14_08680 | Elongation factor Tu | 92.01 | 3.09 |

| rplC | PA14_08850 | 50S ribosomal protein L3 | 27.97 | ND |

| rplD | PA14_08860 | 50S ribosomal protein L4 | 23.35 | 2.05 |

| tyrS | PA14_10420 | Tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase | 37.72 | 11.48 |

| orf2 | PA14_12350 | (dimethylallyl)adenosine tRNA methylthiotransferase | 23.15 | 2.17 |

| rimM | PA14_15980 | 16S rRNA-processing protein RimM | 55.59 | 5.82 |

| trmD | PA14_15990 | tRNA (guanine-N(1)-)-methyltransferase | 52.24 | 4.74 |

| rpsB | PA14_17060 | 30S ribosomal protein S2 | 106.77 | 2.27 |

| deaD | PA14_27370 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase | 122.76 | 2.02 |

| infC | PA14_28660 | Translation initiation factor IF-3 | 12.93 | 2.59 |

| yadB | PA14_62510 | Glutamyl-Q tRNA(Asp) synthetase | 34.45 | 4.5 |

| yhbC | PA14_62780 | Hypothetical protein | 14.37 | ND |

| smpB | PA14_63060 | SsrA-binding protein | 12.7 | 2.36 |

| rpmE | PA14_66710 | 50S ribosomal protein L31 | 316.32 | ND |

| prfH | PA14_72200 | Peptide chain release factor-like protein | 491.76 | 5.65 |

| rnpA | PA14_73420 | Ribonuclease P | 164.46 | 16.33 |

| Stringent response and toxin-antitoxin systems | ||||

| PA14_01510 | PA14_01510 | Hypothetical protein | 25.78 | 4.87 |

| PA14_01520 | PA14_01520 | Hypothetical protein | 28.84 | 4.71 |

| ndk | PA14_14820 | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase | 6.47 | ND |

| obgE | PA14_60445 | GTPase ObgE | 15.46 | 2.42 |

| vapI | PA14_61840 | Antitoxin HigA | 9.67 | 5.8 |

| rnk | PA14_69630 | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase regulator | 11.23 | 2.08 |

| spoT | PA14_70470 | Guanosine-3′.5′-bis(diphosphate) 3′-pyrophosphohydrolase | 9.2 | 3.64 |

1FC, fold-change, p-value ≤ 0.05. 2Genes with FC ≤ –10 or ≥10 are represented in bold. 3X, not efficiently translated in the control and antibiotic treated samples, Ribo-seq BaseMean ≤ 50. 4ND, not differentially expressed, –2 ≤ FC ≤ 2 and/or p-value ≥ 0.05.

The catalytic activities of the isocitrate dehydrogenase Idh, the dihydrolipoamide succinyltransferase SucB and the aconitate hydratase PA14_53970 result in an increased NADH content and promote cellular respiration (Kohanski et al., 2007; Meylan et al., 2017). Upon tobramycin treatment, a down-regulation was observed for these genes of the lower part of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (idh, sucB, and PA14_53970) (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1). The diminished synthesis of enzymes of the lower part of TCA cycle upon tobramycin treatment is in agreement with a recent study, which suggested that Pae can bypass the decarboxylation steps of the cycle to reduce the NADH content, thus decreasing energy production. Growth of Pae on glyoxylate as a sole carbon source leads to the activation of this bypass, and consequently an increase in tobramycin resistance (Meylan et al., 2017).

Amino acid catabolism promotes the production of intermediate metabolites like fumarate, pyruvate, acetyl-CoA and α-ketoglutarate that fuel the TCA cycle, and thus could promote aminoglycosides uptake. Indeed, Pae responds to tobramycin by down-regulating genes encoding enzymes required for glycine and serine (glyA2, gcvT2, sdaA), phenylalanine (pheB, pheC, maiA, fahA), arginine (arcABD) and branched-chain amino acid (bkdA1A2B-lpdV, gnyRBDHL and ldh) catabolism (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1).

Moreover, we also noted that the utilization pathways of D-alanine for peptidoglycan synthesis and transport (ddl, mraY murC, murG, murD, murE) and for glycogen metabolism (PA14_36570, PA14_36580, PA14_36590, PA14_36605, PA14_36620, PA14_36630, glgB, PA14_36730) were down-regulated after exposure to tobramycin (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1).

Tobramycin Affects the Expression of Functions Involved in Pathogenicity, Virulence and Transport

The comparative transcriptome and translatome analyses of PA14 treated with tobramycin uncovered a significantly reduced abundance of several virulence and pathogenicity related genes (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1). The genes encoding the type II (xcp locus) and type VI (tss, hsi, and hcp-1 locus) secretion systems, the quinolone-based quorum-sensing system (pqs genes) as well as the esterase (estA) were down-regulated in the RNA-seq and Ribo-seq data sets. Additionally, genes encoding for functions required for motility, attachment, pilus and fimbrial assembly (PA14_55780-PA14_55940 including tad locus, pil, flg, fli, and flh genes) were primarily down-regulated at the transcriptional level. Pae may prevent tobramycin uptake through the down-regulation of genes of different secretion systems, as they are believed to be the entry gates for several structurally unrelated antimicrobial agents (Tzeng et al., 2005; Mulcahy et al., 2006). Although insertional inactivation of pilZ and fimV have been confirmed to confer low-level tobramycin resistance, it seems interesting to assess the contribution of other motility and attachment genes to aminoglycoside permeability, such as those of the tad locus (Schurek et al., 2008).

The genes encoding ABC transporters such as the dipeptide permease Dpp, involved in the uptake of kasugamycin in E. coli (Shiver et al., 2016), the permease Npp, which plays a role in the translocation of the uridyl peptide antibiotic pacidamycin in Pae (Luckett et al., 2012; Pletzer et al., 2015) and the ATP-binding protein OpuC, showed a tobramycin-dependent down-regulation in both, the RNA-seq and Ribo-seq data. Moreover, the Na+/H+ antiporter pha (sha) operon important for the homeostasis of monovalent cations (Kosono et al., 2005) was also strongly down-regulated after exposure to tobramycin (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1). The Na+/H+ Sha antiporter shows similarity to the membrane subunits of the respiratory Nuo complex and could therefore be of interest for further analysis with regard to its potential impact on the proton motive force and thus aminoglycoside uptake (Mathiesen and Hägerhäll, 2003).

Tobramycin Impacts the Abundance of Genes Involved in Translation

Tobramycin promotes mistranslation, stop codon read-through and ribosome stalling (Aboa et al., 2002; Thompson et al., 2002; Harms et al., 2003; Vioque and Cruz, 2003). A number of genes related to translation were strongly up-regulated in the RNA-seq and Ribo-seq data, including the genes encoding translation initiation factor 3 (infC), ribosomal proteins (rpsB, rplC, rplD), a putative ribosomal maturation factor (yhbC), elongation factor EF-Tu (tufB) and ribonuclease P (rnpA) (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1).

tRNA modifications can play an important role in the modulation of antibiotic resistance by regulating translational processes (Chopra and Reader, 2015). The genes encoding the tRNA methyltransferases TrmD, Orf2, and RimM were significantly up-regulated by tobramycin (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1). TrmD is involved in the m1G37 methylation of proline tRNA (Gamper H.B. et al., 2015; Gamper H. et al., 2015), and recent studies in E. coli and S. enterica revealed that the translation of several membrane-associated proteins is controlled by m1G37 methylation at proline codons near the start of their respective open reading frames. TmrD deficient strains exhibit a decrease in membrane protein content resulting in a higher susceptibility to aminoglycosides (Masuda et al., 2019).

Trans-translation is a process adopted by the cell to rescue stalled ribosomes that requires the specialized tmRNA SsrA and the small accessory protein SmpB (Withey and Friedman, 2003; Haebel et al., 2004). Pathogenic bacteria lacking this system display an enhanced sensitivity toward aminoglycosides (de la Cruz and Vioque, 2001; Aboa et al., 2002; Morita et al., 2006). In this study, several genes encoding effectors of stalled ribosome rescue (PA14_72200, tmRNA ssrA and smpB encoding an accessory protein) were up-regulated after tobramycin exposure (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1).

Furthermore, the gene encoding ObgE, a conserved ribosomal associated GTPase with unknown function (Verstraeten et al., 2015), was up-regulated upon tobramycin treatment (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1). Verstraeten et al. (2015) showed that over-expression of obgE confers tobramycin and ofloxacin tolerance to Pae and E. coli. They further reported that in E. coli Obg-mediated tolerance requires activation of the type I hokB-sokB TA system. Although a hokB ortholog is not present in Pae, we found multiple genes associated with type II TA systems including HigA (VapI) and ParE-ParD (PA14_01510-PA14_01520) that are up-regulated in the presence of tobramycin (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1).

Comparison With Previous Transcriptome Studies

When compared with previous Pae transcriptome studies performed in the presence of polymyxins and tobramycin (Cummins et al., 2009; Fernández et al., 2010; Kindrachuk et al., 2011; Murray et al., 2015; Han et al., 2019; Ben Jeddou et al., 2020) this study revealed a larger number of de-regulated genes. Despite some variances, overlaps concerning de-regulated genes exist. The arn operon, the speD2-speE2 (PA14_63110- PA14_63120) genes, the mexAB-oprN, the mexC, the mexXY (PA14_38395 and amrB), the galU, the cprA (PA14_43311) and the genes of unknown function PA2358 (PA14_34170), PA1797 (PA14_41280), PA14_41290 and PA4782 (PA14_63220) were also previously found to be de-regulated in response to polymyxins or in Pae strains harboring mutations that impact polymyxin resistance (Cummins et al., 2009; Fernández et al., 2010; Murray et al., 2015; Han et al., 2019; Ben Jeddou et al., 2020) (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Kindrachuk et al. (2011) reported that bacteriostatic and bactericidal concentrations of tobramycin stimulate the expression of several heat shock genes and genes encoding transcriptional regulators, whereas genes involved in energy metabolism (i.e., nuo, nqr, and suc genes), motility and attachment (i.e., pil and flg genes) were down-regulated. Our RNA-seq and Ribo-seq results closely mirror these previous findings (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 1).

The transcriptional repression of iron homeostasis- (i.e., has, pvd, pch, fpt, fpv) and sulfonate utilization genes (ssu) (Tralau et al., 2007) and an up-regulation of the denitrification pathway genes (nir, nor, nos) upon exposure to polymyxin B has been reported for PA14 grown in Mueller–Hinton broth (Ben Jeddou et al., 2020). However, this study did not reveal a positive effect on expression of oxidative stress response genes by polymyxin B. On the other hand, transcription of PA14_24360, ahpF, and ahpB was seemingly induced when PA14 was exposed to synthetic antimicrobial peptide dendrimers (Ben Jeddou et al., 2020).

Conclusion

In this study, SCFM was used for culturing Pae, a medium that approximates the environment in the lungs of CF patients (Palmer et al., 2007). To the best of our knowledge, no other gene profiling study has offered a more comprehensive view of Pae’s cellular responses to colistin and tobramycin, and especially under these culturing conditions.

Although the potential of colistin to instigate ROS production in Pae is known, this study revealed for the first time its impact on the expression of distinct oxidative stress response genes. Moreover, the study disclosed a colistin-dependent de-regulation of the AlgU regulon and an up-regulation of the MexT regulon taking on a previously undescribed roles in defense against polymyxin antibiotics (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Depiction of novel functions/pathways revealed in this study that are de-regulated upon (A) colistin and (B) tobramycin treatment. Major genes/pathways that are down-regulated and up-regulated based on the RNA-seq and/or Ribo-seq data are highlighted in rose and green, respectively. Positive- and negative regulation of gene expression is denoted by arrows and blocked lines, respectively. RIP - regulated intramembrane proteolysis.

The transcriptome and translatome studies further indicated that the expression of multiple amino acid catabolism genes, lower TCA cycle genes, type II and VI secretion system genes and genes involved in motility and attachment are rewired in response to tobramycin, presumably to reduce drug uptake. Moreover, we discussed that the adverse effects of tobramycin on translation are countered through the expression of functions involved in stalled ribosome rescue, tRNA methylation and type II TA systems. These findings might aid toward the optimization of strategies to increase the efficacy of these last resort drugs against Pae (Figure 5).

Moreover; our results implicate a number of hypothetical genes of unknown function in colistin and tobramycin resistance (Supplementary Table 1). Deciphering their roles could be the basis for future research to elucidate additional mechanisms of action and resistance to colistin and tobramycin.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/ Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

ACS, BL, ES, and UB conceived and designed the experiments. ACS and BL performed the experiments. ACS, BL, FA, MW, and UB analyzed the data. ACS, BL, and UB wrote the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Petra Pusic and Marlena Rozner for their help with the RNA-seq and Ribo-seq experiments.

Funding. The work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (www.fwf.ac.at/en) through project P33617-B (UB and ES). ACS and BL were supported through the FWF funded doctoral program RNA-Biology W-1207.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2021.626715/full#supplementary-material

Activity of (A) 8 μg/ml colistin and (B) 64 μg/ml tobramycin on growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. The arrows represent the points at which antibiotics were added to growing cultures (OD600 of 1.7). Error bars indicate standard deviations obtained from two biological replicates.

Superimposition of the (A) tonB2-exbB1-exbD1, (B) feo, (C) has, and (D) pvd genes with the ribosome profiling data. In pink – open reading frames (ORF) of corresponding genes located on the negative strand of PA14 genomic DNA; in orange – ORFs of corresponding genes located on the positive strand of PA14 genomic DNA; in light green – mapped ribosomal footprints obtained from control samples, in dark green – mapped ribosomal footprints obtained from colistin treated samples.

Increased susceptibility of PA14ΔalgU toward colistin. (A) The microdilution assay was performed in duplicate with strains PA14 and PA14ΔalgU, aerobically grown in SCFM medium to an OD600 of ∼2.0. Then, 0.5 ml of the culture was mixed with 1.5 ml of SCFM medium, containing serial dilutions of colistin (concentration 4–64 μg/ml). The cultures were shaken at 37°C for 20 h and the pictures were taken. The minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs; marked by red edging) correspond to the lowest concentration of colistin that visibly impeded growth. Control, no colistin added. (B) Graphical representation of the results shown in (A). The outcome of the duplicate assay was identical.

RNA-seq and Ribo-seq differential gene expression analysis of Pae treated with colistin or tobramycin versus untreated control.

Changes in transcript and ribosomal footprint abundance of genes which contribute to polymyxin and aminoglycoside resistance/susceptibility in Pae after exposure to colistin and tobramycin.

Changes in transcript and ribosomal footprint abundance of genes belonging to the AlgU regulon in Pae (Schulz et al., 2015) in the presence of 8 μg/ml colistin.

References

- Aboa T., Ueda K., Sunohara T., Ogawa K., Aiba H. (2002). SsrA-mediated protein tagging in the presence of miscoding drugs and its physiological role in Escherichia coli. Genes Cells 7 629–638. 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00549.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S., Huber W. (2010). Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 11:R106. 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonic V., Stojadinovic A., Zhang B., Izadjoo M. J., Alavi M. (2013). Pseudomonas aeruginosa induces pigment production and enhances virulence in a white phenotypic variant of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Drug Resist. 6 175–186. 10.2147/IDR.S49039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrow K., Kwon D. H. (2009). Alterations in two-component regulatory systems of phoPQ and pmrAB are associated with polymyxin B resistance in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53 5150–5154. 10.1128/AAC.00893-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Jeddou F., Falconnet L., Luscher A., Siriwardena T., Reymond J. L., Van Delden C., et al. (2020). Adaptive and mutational responses to peptide dendrimer antimicrobials in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 64 e02040–19. 10.1128/AAC.02040-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins W. R., Tavella T., Moro S. G., Blasco-Moreno B., Closa-Mosquera A., Diez J., et al. (2018). Using ribosome profiling to quantify differences in protein expression: a case study in Saccharomyces cerevisiae oxidative stress conditions. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 501478. 10.1101/501478 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breidenstein E. B. M., de la Fuente-Núñez C., Hancock R. E. W. (2011). Pseudomonas aeruginosa: all roads lead to resistance. Trends Microbiol. 19 419–426. 10.1016/j.tim.2011.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brochmann R. P., Toft A., Ciofu O., Briales A., Kolpen M., Hempel C., et al. (2014). Bactericidal effect of colistin on planktonic Pseudomonas aeruginosa is independent of hydroxyl radical formation. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 43 140–147. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. M., Howell M. L., Vasil M. L., Anderson A. J., Hassett D. J. (1995). Cloning and characterization of the katB gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encoding a hydrogen peroxide-inducible catalase: purification of KatB, cellular localization, and demonstration that it is essential for optimal resistance to hydrogen p. J. Bacteriol. 177 6536–6544. 10.1128/jb.177.22.6536-6544.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartron M. L., Maddocks S., Gillingham P., Craven C. J., Andrews S. C. (2006). Feo - Transport of ferrous iron into bacteria. BioMetals 19 143–157. 10.1007/s10534-006-0003-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra S., Reader J. (2015). tRNAs as antibiotic targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16 321–349. 10.3390/ijms16010321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins J., Reen F. J., Baysse C., Mooij M. J., O’Gara F. (2009). Subinhibitory concentrations of the cationic antimicrobial peptide colistin induce the pseudomonas quinolone signal in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 155 2826–2837. 10.1099/mic.0.025643-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damron F. H., Goldberg J. B. (2012). Proteolytic regulation of alginate overproduction in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 84 595–607. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08049.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cruz J., Vioque A. (2001). Increased sensitivity to protein synthesis inhibitors in cells lacking tmRNA. RNA 7 1708–1716. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deris Z. Z., Akter J., Sivanesan S., Roberts K. D., Thompson P. E., Nation R. L., et al. (2014). A secondary mode of action of polymyxins against Gram-negative bacteria involves the inhibition of NADH-quinone oxidoreductase activity. J. Antibiot. 67 147–151. 10.1038/ja.2013.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas Z., Ross-Gillespie A., Kümmerli R. (2013). Switching between apparently redundant iron-uptake mechanisms benefits bacteria in changeable environments. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 280 20131055. 10.1098/rspb.2013.1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed Ahmed M. A. E.-G., Zhong L.-L., Shen C., Yang Y., Doi Y., Tian G.-B. (2020). Colistin and its Role in the Era of Antibiotic Resistance: an extended review (2000-2019). Emerg. Microbes Infect. 9 868-885. 10.1080/22221751.2020.1754133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fajardo A., Martínez-Martín N., Mercadillo M., Galán J. C., Ghysels B., Matthijs S., et al. (2008). The Neglected Intrinsic Resistome of Bacterial Pathogens. PLoS One 3:e1619. 10.1371/journal.pone.0001619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fargier E., Mac Aogáin M., Mooij M. J., Woods D. F., Morrissey J. P., Dobson A. D. W., et al. (2012). MexT Functions as a Redox-Responsive Regulator Modulating Disulfide Stress Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 194 3502–3511. 10.1128/JB.06632-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrant K. V., Spiga L., Davies J. C., Williams H. D. (2020). Response of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the innate immune system-derived oxidants hypochlorous acid and hypothiocyanous acid. bioRxiv. [Preprint]. 10.1101/2020.01.09.900639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández L., Álvarez-Ortega C., Wiegand I., Olivares J., Kocíncová D., Lam J. S., et al. (2013). Characterization of the polymyxin B resistome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57 110–119. 10.1128/AAC.01583-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández L., Gooderham W. J., Bains M., McPhee J. B., Wiegand I., Hancock R. E. W. (2010). Adaptive resistance to the “last hope” antibiotics polymyxin B and colistin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is mediated by the novel two-component regulatory system ParR-ParS. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54 3372–3382. 10.1128/AAC.00242-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández L., Jenssen H., Bains M., Wiegand I., Gooderham W. J., Hancock R. E. W. (2012). The two-component system CprRS senses cationic peptides and triggers adaptive resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa independently of ParRS. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56 6212–6222. 10.1128/AAC.01530-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetar H., Gilmour C., Klinoski R., Daigle D. M., Dean C. R., Poole K. (2011). mexEF-oprN multidrug efflux operon of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: regulation by the MexT activator in response to nitrosative stress and chloramphenicol. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55 508–514. 10.1128/AAC.00830-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraud S., Campigotto A. J., Chen Z., Poole K. (2008). MexCD-OprJ multidrug efflux system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: involvement in chlorhexidine resistance and induction by membrane-damaging agents dependent upon the AlgU stress response sigma factor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52 4478–4482. 10.1128/AAC.01072-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]