Abstract

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the most common cause of visual impairment in developed countries. Inflammation serves a critical role in the pathogenesis of AMD. Gardenia jasminoides is found in several regions of China and is traditionally used as an organic yellow dye but has also been widely used as a therapeutic agent in numerous diseases, including inflammation, depression, hepatic and vascular disorders, which may reflect the variability of functional compounds that are present in Gardenia jasminoides extracts (GJE). To investigate the therapeutic potential of GJE for AMD, ARPE-19 cells were treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or LPS plus GJE. GJE significantly decreased LPS-induced expression of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α. In the in vivo study, GJE inhibited CuSO4-induced migration of primitive macrophages to the lateral line in zebrafish embryos. GJE also attenuated expression of cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α), NFKB activating protein (nkap) and TLR4 in ARPE-19 cells. The results of the present study demonstrated the anti-inflammatory potential of GJE in vitro and in vivo, and suggested GJE as a therapeutic candidate for AMD.

Keywords: age-related macular degeneration, inflammation, retinal pigment epithelial cells, zebrafish embryos, Gardenia jasminoides

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is recognized as a serious and rapidly growing worldwide public health concern and is the third leading cause of blindness after glaucoma and cataracts (1). The prevalence of AMD by 2040 is projected to significantly increase to ~288 million cases (2). Different factors may contribute toward AMD, including age, environmental factors and genetic susceptibility. Ageing may strengthen the problem of visual difficulty associated with AMD. Patients with AMD have extracellular deposits called drusen, which are accumulated within Bruch's membrane (BrM) located between retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and the choroid. AMD is classified according to age-related eye disease study based on the amount of drusen and it includes early AMD, intermediate AMD and late AMD (3). The late AMD is sub-divided into the dry non-neovascular type distinguished by the existence of drusen spreading in the central macula, and the wet neovascular type characterized by neovascularization within sub-RPE and sub-retinal space (4). The progression of neovascular AMD may be decreased by injecting anti-VEGF agents into the vitreous humour monthly (5). However, at present, there is no standard medical treatment for dry non-neovascular AMD. Development of novel therapeutic strategies is therefore urgently required.

Inflammation serves a vital role in the pathogenesis of AMD (6). A recent study has reported that plasma levels of interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF) R2 are significantly higher in patients with dry AMD than in healthy controls (7). Additionally, the IL-6 level is also associated with the progression of geographic atrophy (7). In wet AMD, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α levels in plasma are significantly high, compared with healthy controls (8). Patients with wet AMD also have an increased expression of inflammation-associated chemokines (CXCL7, 10, 14, 16 and 22) in the aqueous humor (9). NLRP3 inflammasome is upregulated in macular lesions of patients with dry and wet AMD (10). Analyses of plasma complement components have demonstrated systemic complement activation being associated with AMD (11-14). The RPE is responsible for the maintenance of photoreceptor function, and RPE dysfunction is the primary cause of AMD. Inflammation may be induced in the RPE under stress conditions (6). Recently, it was demonstrated that oxidative stress-induced inflammation in RPE cells, indicated by a significant increase in the secretion of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α and VEGF (15,16). The RPE is the main cause of drusen formation, and numerous constituents of drusen deposits are inflammation mediators (17). For example, oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) may activate inflammasome and increase secretion of proinflammatory cytokines in human RPE cells (18,19). 7-ketocholesterol (7KC) is another component of drusen, which also induces inflammation in human RPE cells by upregulating the expression of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α (20,21).

Gardenia jasminoides (G. Jasminoides, ‘Zhi Zi’ in Chinese) is an evergreen shrub with fragrant white flowers, which grows in numerous regions of China and is predominantly used as an organic yellow dye (22). The fruits of G. Jasminoides are rich in antioxidant and anti-inflammatory compounds and have been used as a dietary supplement in Chinese herbal medicine for many years to treat a variety of human diseases, including headache, fever, liver disease and hypertension (23). A total of 35 iridoid glycosides and 8 corcin and its derivatives have been identified in G. Jasminoides fruits. The functions of certain identified constituents have been characterized and demonstrated to have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic and anticancer activities (22,24).

We hypothesised that G. Jasminoides extract (GJE) may have therapeutic potential for AMD. The present study assessed the efficacy of GJE against inflammation in human RPE cells in vitro and in Zebrafish embryos. It was found that GJE decreased lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation in human RPE cells. It was also demonstrated that GJE inhibited LPS and CuSO4-induced inflammation in Zebrafish embryos.

Materials and methods

Preparation of G. Jasminoides extract

The dried fruits of G. Jasminoides were collected in October 2017 from a local farm in Yueyang, Hunan, P.R. China. The dried fruits were ground into powder, which was passed through a 40-mesh sieve. A total of 50 g powder was extracted with 500 ml 75% ethanol by microwave extraction at 60˚C for 30 min. The obtained extract solutions were filtered and evaporated under a reduced pressure at 40˚C to remove the solvents. The dried GJE was dissolved in methanol at 500 µg/ml and filtered through a 0.22 µm pore size member for further analysis.

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis

The HPLC separation was performed using a Waters WATO54275-C18 column (250x4.6 mm, 5 µm, Waters China, Ltd.) installed on a Waters 2695 HPLC instrument (Waters Corporation). The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% phosphoric acid (A) and acetonitrile (B) with a gradient elution: 0-15 min, 4-25% B; 15-20 min, 25-28% B; 20-40 min, 28-38% B; 40-41 min, 95% B; 41-51 min, 95-4% B. The flow rate was 1 ml/min, and the injection volume was 10 µl. The temperature of the column was set at 25˚C. Standard compounds, including geniposidic acid, deacetylasperulosidic acid, genipin-1-gentiobioside, geniposide, crocin I and II with >98% purity were purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd.

Cell viability

ARPE-19 cells (human retina pigment epithelium cells) were purchased from ATCC (ATCC® CRL-2302™) and cultured in 96-well plates at a density of 5x104 cells/well in DMEM/F-12 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at a final volume of 100 µl at 37˚C in 95% air and 5% CO2. A total of 24 h later, the cells were washed twice with 1X PBS and treated with LPS dissolved in water at different concentrations: 0, 1.0, 2.5, 5.0, 10.0 and 20 µg/ml, with or without GJE dissolved in methanol at concentrations of 5, 10, 25, 50 and 100 µg/ml for 24 h. Subsequently, the cells were washed with 1X PBS twice and treated with serum-free medium containing 0.5 µg/ml MTT (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) with the final volume of 50 µl per well for 2 h. Next, the MTT solution was removed from the plate, and 100 µl/well dimethyl sulfoxide was added. The concentration of formazan was evaluated using an EPOCH microplate reader at 570 nm. The percentage of live cells was calculated using the following formula: % of viable cells = (OD of treated cells/OD of control cells) x100.

Zebrafish embryo treatment

All the animal experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Ethics and Welfare Committee, Glasgow Caledonian University (Project License PPL 60/4169). Breeding was set up in the Animal Unit at Glasgow Caledonian University using adult wild-type and transgenic zebrafish (Tg:zlyz-EGFP) expressing EGFP in primitive macrophages to get fertilized embryos, which were maintained in E3 medium consisting of 5 mM NaCl, 0.17 mM KCl, 0.33 mM CaCl2 and 0.33 mM MgSO4 (25). CuSO4 has been used to induce acute inflammation, as previously described (26-28). A total of 24 transgenic zebrafish (Tg:zlyz-EGFP) embryos at 48 h post-fertilization (hpf) were treated with or without GJE (diluted in E3 medium, 5 µg/ml) for 24 h (i.e. until 72 hpf). Zebrafish embryos were further treated with CuSO4 (20 µM) for 1 h to induce the acute inflammation, by adopting the previously reported protocol (26,27). Following treatment, embryos were fixed at room temperature for 2 h in 4% paraformaldehyde, and macrophage migration to the lateral line was examined using fluorescent microscopy (magnification, x100). Additionally, the embryos were collected for further gene expression analysis. Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) have also been commonly used to induce inflammation in zebrafish (26-29), and this method was also used in the present study. Wild-type zebrafish embryos at 48 hpf were treated with GJE (5 µg/ml) only, or with GJE plus LPS (5 µg/ml) for 24 h. Following the treatment, embryos were collected and subjected to gene expression analysis.

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from treated and control cells or zebrafish embryos using TRIzol® (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KgaA), according to the manufacturer's protocols. High-capacity cDNA Reverse Transcriptase kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used for cDNA synthesis, according to the manufacturer's protocols. The RT-qPCR assay was used to quantify gene expression using 5X HOT FIREPol EvaGreen qPCR Mix Plus (ROX) kit (Solis Biodyne) with 12.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dNTPs, according to the manufacturer's protocols. Reactions were performed in triplicates with a total volume of 10 µl consisting of 5.5 µl nuclease-free water, 2 µl EvaGreen, 0.75 µl 10 µM forward and reverse primers and 2 µl cDNA (60-120 ng). For the control, all reagents were used except cDNA, which was replaced with an equal volume of nuclease-free water. The reaction was performed in the CFX96 Real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) under the following conditions: Denaturation at 95˚C for 2 min; and 40 cycles including denaturation at 95˚C for 15 sec, and annealing at 60˚C. The fluorescence signals were detected at the end of the 60˚C-step. The relative expression was calculated using the 2-∆∆Cq formula (30). Primers used for RT-qPCR are listed in Tables SI and SII.

ELISA

Following the exposure of ARPE-19 cells to GJE (5 µg/ml), LPS (5 µg/ml) or GJE (5 µg/ml) with LPS (5 µg/ml) for 24 h, the culture media were collected and centrifuged at 12,000 x g for 15 min at 4˚C. The IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α in the supernatants were measured using human Mini ELISA development kits for IL-1β (cat. no. 900-M95), IL-6 (cat. no. 900-M16) and TNF-α (cat. no. 900-M25) (PeproTech, Inc.).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n=6). Statistical analysis of the data was performed using GraphPad Prism software version 8 (GraphPad Software, Inc.) by one-way analysis of variance, followed by Dunnett's or Tukey's post hoc test. Linear regression analysis was performed based on the GraphPad Prism 9 Curve Fitting Guide (GraphPad Software, Inc.). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Analysis of compounds in GJE

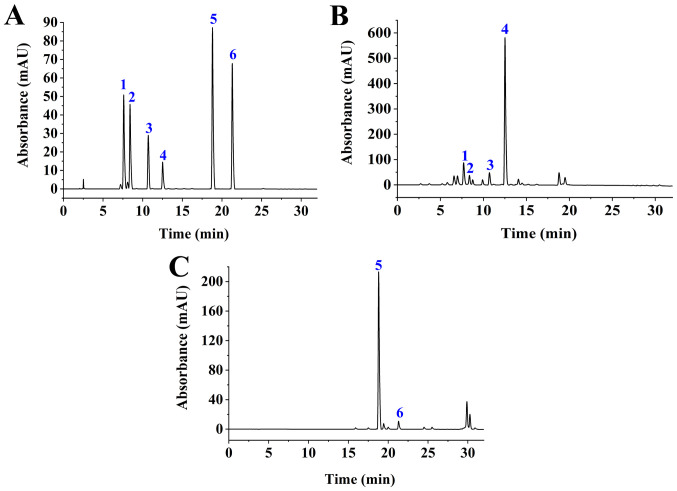

Following microwave-assisted extraction, GJE was subjected to HPLC analysis. Based on six standards, it was found that geniposide and Crocin-1 were the major compounds (Fig. 1), which is in agreement with the results of a recent report (31). The other four compounds, geniposidic acid, deacetylasperulosidic acid, genipin-1-gentiobioside and Crocin II, were also identified in GJE but at low levels. Retention times for geniposide and Crocin I was 12.85 min and 18.766 min, respectively. Linear regression analyses were performed on the concentration (X, µg/ml) and the peak area (Y) of geniposide or Crocin I at different concentrations. The regression equations for geniposide and Crocin I were y=19262073.0848 x-14747.0407 (Coefficient, 0.9999) and y=36463016.7557 x +278758.6821 (coefficient, 0.9992), respectively. The relative standard deviation for precision was 2.31% (geniposide) and 1.22% (Crocin I), for repeatability it was 1.59% (geniposide) and 2.11% (Crocin I), and for stability it was 1.39% (geniposide) and 1.58% (Crocin I). The average recoveries for geniposide and Crocin I were 99.62 and 94.94%, respectively. The contents of geniposide and Crocin I in G. Jasminoides fruits were 40.88 and 7.72 mg/g, respectively.

Figure 1.

HPLC analysis. (A) HPLC chromatogram of standard compounds: 1, geniposidic acid; 2, deacetylasperulosidic acid; 3, genipin-1-gentiobioside; 4, geniposide; 5, Crocin I; and 6 and Crocin II. (B) HPLC chromatogram of GJE component: 1, geniposidic acid; 2, deacetylasperulosidic acid; 3, genipin-1-gentiobioside; and 4, geniposide were identified with a detection wavelength of 238 nm. (C) HPLC chromatogram of GJE component: 5, Crocin I; and 6, Crocin II were identified at a detection wavelength of 440 nm. HPLC, High-performance liquid chromatography; GJE, Gardenia jasminoides extracts.

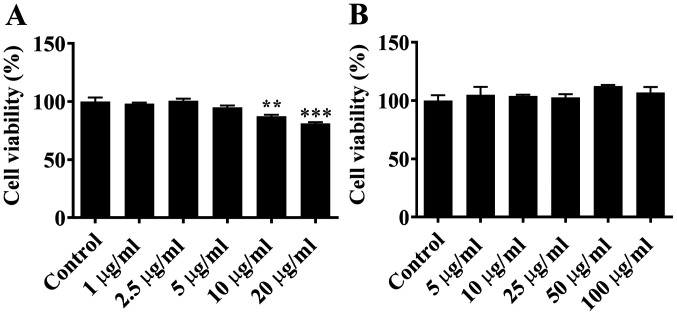

Effects of LPS and GJE on cell viability

ARPE-19 cells were treated with LPS at concentrations of 0, 1.0, 2.5, 5.0, 10.0 or 20.0 µg/ml for 24 h. MTT assay demonstrated that LPS at 1.0, 2.5 or 5.0 µg/ml had no significant effect on the viability of ARPE-19 cells compared with control cells. However, LPS at higher concentrations (10.0 or 20.0 µg/ml) was significantly toxic for ARPE-19 cells, and notably decreased cell viability (Fig. 2A). When ARPE-19 cells were treated with GJE at concentrations of 0, 5.0, 10.0, 25.0, 50.0 or 100.0 µg/ml, there was no significant difference in cell viability compared with untreated cells (Fig. 2B). Based on these data, LPS at 5.0 µg/ml and GJE at 5.0 µg/ml were selected for further experiments.

Figure 2.

Effects of LPS (A) and GJE (B) on cell viability. The specific concentration of LPS or GJE was used to treat ARPE-19 cells for 24 h, prior to MTT assay being used to measure cell viability, with untreated cells as a control. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean and analysed by one-way analysis of variance, followed by Dunnett's post-hoc test. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. LPS, lipopolysaccharides; GJE, Gardenia jasminoides extracts.

GJZ inhibits LPS-induced inflammation in ARPE-19 cells

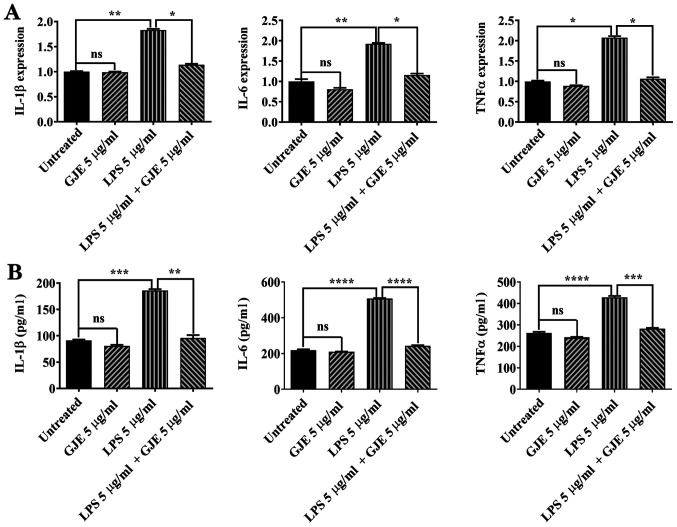

A total of 5 µg/ml LPS has been used to induce inflammation in AREP-19 cells (32,33). ARPE-19 cells were treated with GJE, LPS or GJE plus LPS for 24 h and the expression of proinflammatory cytokines was compared. LPS significantly increased the expression of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α in AREP-19 cells compared with control cells, while GJE treatment did not cause any changes in expression of these inflammatory mediators. Co-treatment with GJE resulted in markedly decreased expression of these three cytokine genes compared with cells treated with LPS alone (Fig. 3A). Next, ELISA was performed to detect cytokine secretion in control cells and treated cells. LPS exposure significantly increased cytokine secretion, while GJE-treated cells secreted cytokines similarly to control cells. These results suggested that treatment with GJE reversed LPS-induced cytokine secretion (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Effects of GJE on the expression of proinflammatory cytokines. (A) mRNA levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α in treated and untreated cells were measured by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. (B) Secreted IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α protein levels in media of untreated and treated cells were measured using ELISA. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean and analyzed using one-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. GJE, Gardenia jasminoides extracts; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

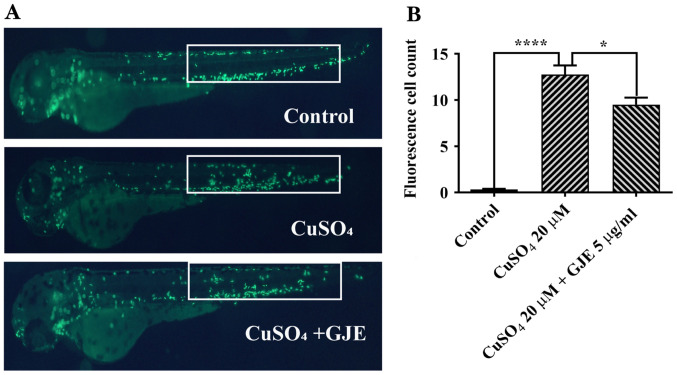

GJE attenuates microphage migration in zebrafish embryos

Previous reports have demonstrated that CuSO4 at 20 µM causes primitive macrophage migration to the lateral line in zebrafish embryos (26-28). It was also found that the number of migrated macrophages in treated cells was significantly higher than that in untreated controls. These results indicated that co-treatment significantly decreased macrophage migration (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

GJE inhibits CuSO4-induced primitive macrophage migration in transgenic zebrafish (Tg:zlyz-EGFP) embryos; magnification, x100. (A) Representative images of control and treated zebrafish embryos. (B) Macrophages in the regions of interest (white boxes) were quantified. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean and analysed using one-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. *P<0.05, ****P<0.0001. GJE, Gardenia jasminoides extracts; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; LPS, lipopolysaccharides.

GJE reduces inflammation in zebrafish embryos

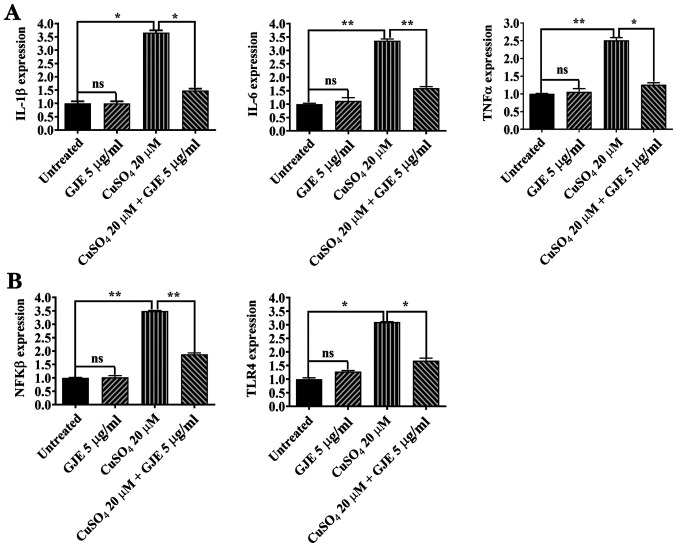

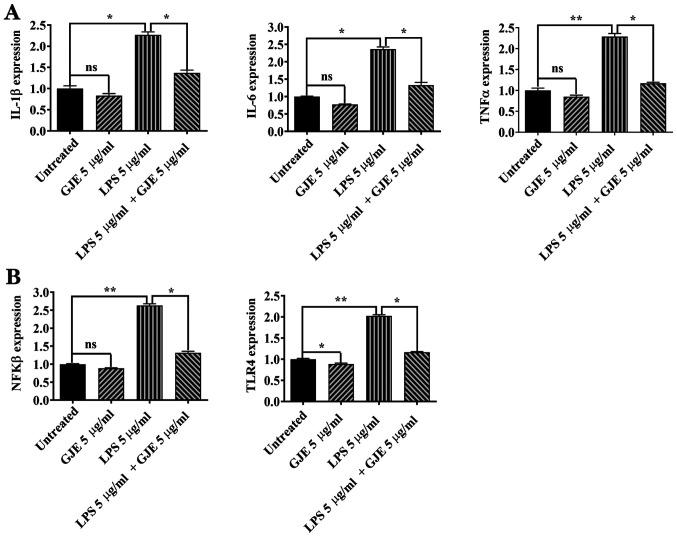

The present study measured the expression of proinflammatory cytokines in control and treated zebrafish embryos using RT-qPCR. CuSO4 treatment resulted in significantly increased expression of IL-1β, IL6 and TNFα cytokines compared with that of controls, while GJE did not cause any alteration in expression of these cytokines. The embryos co-exposed to the two compounds had a significantly decreased expression of cytokines compared with embryos exposed to CuSO4 alone (Fig. 5A). The effects of LPS or LPS plus GJE were investigated in zebrafish embryos. Similar to the in vitro results in ARPE-19 cells, LPS significantly increased the expression of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα, while GJE treatment counteracted LPS-induced effects on the expression of the three genes (Fig. 6A).

Figure 5.

Effects of GJE on inflammation via the TLR4 signaling pathway in CuSO4-treated zebrafish embryos. (A) mRNA levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α in treated and untreated embryos were measured by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. (B) Expression levels of of NFKβ and TLR4 in untreated or treated embryos were measured by qRT-PCR. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean and analyzed using one-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. GJE, Gardenia jasminoides extracts; TLR4, toll-like receptor 4; ns, no significance; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; LPS, lipopolysaccharides.

Figure 6.

Effects of GJE on inflammation via the TLR4 signaling pathway in LPS-treated zebrafish embryos. GJE decreased LPS-induced expression of proinflammatory cytokine genes (A), attenuated LPS-induced expression of NFKβ activating protein and decreased LPS-induced TLR4 expression (B). Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean and analyzed using one-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. GJE, Gardenia jasminoides extracts; TLR4, toll-like receptor 4; ns, no significance; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; LPS, lipopolysaccharides.

The NFkB signaling pathway serves a central role in regulating inflammation (34). Therefore, the present study investigated the NFKB activating protein (nkap) expression by RT-qPCR. The results of the present study suggested that CuSO4 and LPS markedly enhanced nkap expression compared with that of control zebrafish embryos. Additionally, co-treatment with GJE resulted in significantly decreased expression of nkap compared with the embryos exposed to CuSO4 or LPS alone (Figs. 5B and 6B). Finally, activation of the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling pathway induces the nuclear translocation of NF-κB and leads to upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines (35). The present study found higher expression of tlr4b in CuSO4 or LPS-treated embryos that were significantly counteracted by co-treatment with GJE (Figs. 5B and 6B).

Discussion

Inhibition of inflammatory agents represents an effective therapeutic strategy to treat AMD (36). There are numerous natural products, which are rich in anti-inflammatory compounds. In GJE, six predominant compounds, including geniposidic acid, deacetylasperulosidic acid, genipin-1-gentiobioside, geniposide, Crocin I and II, were identified and the anti-inflammatory potential of GJE was confirmed in vitro and in vivo. The attenuated expression of proinflammatory cytokines is associated with GJE-evoked inhibition of the TLR4-mediated signal pathway, given that expression of TLR4 and NKAP were revealed to be downregulated.

Numerous active compounds have been identified in G. Jasminoides, including iridoids, iridoid glycosides, terpenoids and phenolic acids (36). While geniposide and Crocin I were the predominant compounds in GJE, geniposidic acid, deacetylasperulosidic acid, genipin-1-gentiobioside and Crocin II were also detected at a low level in GJE (Fig. 1). The anti-inflammatory characteristics of the whole GJE and its individual active components have been widely studied (22,37). An early study reported the anti-inflammatory capacity of ethanol-based extracts of G. Jasminoides in inhibiting carrageenan-induced rat paw oedema and acetic acid-induced vascular permeability (38). Hwang et al (39) reported that GJE decreased vascular inflammation in TNF-α treated human umbilical vein endothelial cells via preventing NF-kB p65 nuclear translocation, downregulating adhesion molecule expression and decreasing monocyte-endothelial cell interaction (39). GJE was also reported to decrease LPS-induced production of IL-1β, IL-6 and nitric oxide in microglial BV2 cells through inactivation of the MAPK signalling pathway (40). Geniposide, the main functional compound of G. Jasminoides, has shown strong anti-inflammatory activity in vitro and in vivo. For example, it significantly decreased the production of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α, decreased expression and translocation of NF-κB p65, and inhibited the MAPK signalling pathway in rat primary microglia exposed to oxygen-glucose deprivation (41). Geniposide also showed similar protective effects in LPS-exposed macrophages and in mice challenged with LPS (42). Crocin, another active compound identified in G. Jasminoides, also showed anti-inflammatory activity by decreasing the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and decreasing nitric oxide production (43,44).

In the present study, G. Jasminoides components demonstrated a protective effect against retinal damage. Crocin and genipin (a metabolite of geniposide) protect ARPE-19 cells from H2O2-caused oxidative damage by decreasing the production of reactive oxygen species and inhibiting Caspase 3-mediated apoptosis via the NRF2 signalling pathway (45,46). Crocin may decrease H2O2-induced RGC-5 ganglion cell death by inhibiting oxidative stress and apoptosis, and reversing NF-κB activation (47). Crocin may also increase the survival of rat ganglion cells following ischemia/reperfusion injury and protect photoreceptors from blue-light damage in cultured bovine and primate retinas (48-50). Recently, a clinical trial showed that Crocin (15 mg/day for three months) resulted in a decrease in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) and in central macula thickness, and result in an improvement of the best-corrected visual acuity in patients with diabetic maculopathy (51). Crocetin, another active compound identified in G. Jasminoides, protected ganglion cells against H2O2-induced oxidative damage and prevent photoreceptor degeneration from light-induced damage (52). Crocetins also inhibit retinal damage from ischemia/reperfusion injury or from N-methyl-D-aspartate-induced toxicity via blocking Caspase and NFkB pathways (53,54). Recently, Nitta et al (55) reported that crocetin prevented retinal edema in a laser-induced retinal vein occlusion mouse model via downregulating the expression of MMP-9 and TNF-α. Given the multifaceted anti-inflammatory impact of GJE treatment in vitro and in vivo reported in the present study, it is likely that the combination of active compounds may evoke more profound effects than any single-compound treatment. The optimum dose of these compounds may be even more effective and require further investigation.

The results of the present study were based on an in vitro RPE model and zebrafish embryo inflammation models, which may not be directly relevant to an in vivo AMD study. Further studies will be required to investigate the anti-inflammatory role of GJE in preclinical AMD models to further verify the results of the current study. In addition, it is valuable to gain more insights into the molecular mechanisms of GJE's protection in vivo.

In summary, the results of the present study demonstrated the anti-inflammatory role of GJE in RPE cells and in zebrafish embryos. Given that it is a natural product with a long history in Traditional Chinese Medicine, GJE appears to have therapeutic potential for treating patients with AMD and could be easily translated to the clinics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

Funding: The present study was funded by the Department of Education, Hunan, China (grant no. 19A045); the Hunan Province ‘Help Our Motherland Through Elite Intellectual Resources from Overseas’ program to ZZ (grant no. 60802); and a Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 2020JJ4641) to JC. The study was partially supported by the Rosetrees Trust (grant nos. M160, M160-F1 and M160-F2), National Eye Research Centre (grant no. SAC037) and the Lotus Scholarship Program of Hunan Province (2019) to XS.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

XS and ZZ designed the experiments. JC, GMT, XZ, WT, FL, ML and CZ performed the experiments. JC, GMT and XZ analyzed the data. XS and ZZ wrote the manuscript. XS and ZZ confirmed the authenticity of the raw data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All the animal experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Ethics and Welfare Committee, Glasgow Caledonian University (Project License PPL 60/4169).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Mantel I. Age-related macular degeneration-a challenge for public health care. Ther Umsch. 2016;73:79–83. doi: 10.1024/0040-5930/a000760. (In German) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong WL, Su X, Li X, Cheung CM, Klein R, Cheng CY, Wong TY. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e106–e116. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1417–1436. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.10.1417. Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jager RD, Mieler WF, Miller JW. Age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2606–2617. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0801537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuan A, Kaiser PK. Emerging therapies for the treatment of neovascular age related macular degeneration. Semin Ophthalmol. 2011;26:149–155. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2011.570846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Datta S, Cano M, Ebrahimi K, Wang L, Handa JT. The impact of oxidative stress and inflammation on RPE degeneration in non-neovascular AMD. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2017;60:201–218. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krogh Nielsen M, Subhi Y, Molbech CR, Falk MK, Nissen MH, Sørensen TL. Systemic levels of interleukin-6 correlate with progression rate of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60:202–208. doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-25878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Subhi Y, Krogh Nielsen M, Molbech CR, Oishi A, Singh A, Nissen MH, Sørensen TL. Plasma markers of chronic low-grade inflammation in polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy and neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol. 2019;97:99–106. doi: 10.1111/aos.13886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu F, Ding X, Yang Y, Li J, Tang M, Yuan M, Hu A, Zhan Z, Li Z, Lu L. Aqueous humor cytokine profiling in patients with wet AMD. Mol Vis. 2016;22:352–361. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y, Hanus JW, Abu-Asab MS, Shen D, Ogilvy A, Ou J, Chu XK, Shi G, Li W, Wang S, Chan CC. NLRP3 upregulation in retinal pigment epithelium in age-related macular degeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(73) doi: 10.3390/ijms17010073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sivaprasad S, Adewoyin T, Bailey TA, Dandekar SS, Jenkins S, Webster AR, Chong NV. Estimation of systemic complement C3 activity in age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:515–519. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.4.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scholl HP, Charbel Issa P, Walier M, Janzer S, Pollok-Kopp B, Börncke F, Fritsche LG, Chong NV, Fimmers R, Wienker T, et al. Systemic complement activation in age-related macular degeneration. PLoS One. 2008;3(e2593) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reynolds R, Hartnett ME, Atkinson JP, Giclas PC, Rosner B, Seddon JM. Plasma complement components and activation fragments: Associations with age-related macular degeneration genotypes and phenotypes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:5818–5827. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Machalińska A, Dziedziejko V, Mozolewska-Piotrowska K, Karczewicz D, Wiszniewska B, Machaliński B. Elevated plasma levels of C3a complement compound in the exudative form of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmic Res. 2009;42:54–59. doi: 10.1159/000219686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alhasani RH, Biswas L, Tohari AM, Zhou X, Reilly J, He JF, Shu X. Gypenosides protect retinal pigment epithelium cells from oxidative stress. Food Chem Toxicol. 2018;112:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2017.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tohari AM, Alhasani RH, Biswas L, Patnaik SR, Reilly J, Zeng Z, Shu X. Vitamin D attenuates oxidative damage and inflammation in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Antioxidants (Basel) 2019;8(341) doi: 10.3390/antiox8090341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kauppinen A, Paterno JJ, Blasiak J, Salminen A, Kaarniranta K. Inflammation and its role in age-related macular degeneration. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:1765–1786. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2147-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biswas L, Zhou X, Dhillon B, Graham A, Shu X. Retinal pigment epithelium cholesterol efflux mediated by the 18 kDa translocator protein, TSPO, a potential target for treating age-related macular degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26:4327–4339. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gnanaguru G, Choi AR, Amarnani D, D'Amore PA. Oxidized lipoprotein uptake through the CD36 receptor activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:4704–4712. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-18663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larrayoz IM, Huang JD, Lee JW, Pascual I, Rodríguez IR. 7-Ketocholesterol-induced inflammation: Involvement of multiple kinase signaling pathways via NFκB but independently of reactive oxygen species formation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:4942–4955. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang C, Xie L, Gu Q, Qiu Q, Wu X, Yin L. 7-Ketocholesterol disturbs RPE cells phagocytosis of the outer segment of photoreceptor and induces inflammation through ERK signaling pathway. Exp Eye Res. 2019;189(107849) doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2019.107849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen L, Li M, Yang Z, Tao W, Wang P, Tian X, Li X, Wang W. Gardenia jasminoides Ellis: Ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry, and pharmacological and industrial applications of an important traditional Chinese medicine. J Ethnopharmacol. 2020;257(112829) doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.112829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. National Commission of Pharmacopoeia: Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China, Vol. 1. China Medical Science and Technology Press, Beijing, pp231, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song X, Zhang W, Wang T, Jiang H, Zhang Z, Fu Y, Yang Z, Cao Y, Zhang N. Geniposide plays an anti-inflammatory role via regulating TLR4 and downstream signaling pathways in lipopolysaccharide-induced mastitis in mice. Inflammation. 2014;37:1588–1598. doi: 10.1007/s10753-014-9885-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y, Bai XT, Zhu KY, Jin Y, Deng M, Le HY, Fu YF, Chen Y, Zhu J, Look AT, et al. In vivo interstitial migration of primitive macrophages mediated by JNK-matrix metalloproteinase 13 signaling in response to acute injury. J Immunol. 2008;181:2155–2164. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li JJ, Zhang Y, Han LW, Tian QP, He QX, Wang XM, Sun C, Han J, Liu KC. Tenacissoside H exerts an anti-inflammatory effect by regulating the NF-κB and p38 pathways in zebrafish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2018;83:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2018.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y, Wang C, Jia ZL, Ma RJ, Wang XF, Chen WY, Liu KC. Isoniazid promotes the anti-inflammatory response in zebrafish associated with regulation of the PPARγ/NF-κB/AP-1 pathway. Chem Biol Interact. 2020;316(108928) doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2019.108928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou H, Cao H, Zheng Y, Lu Z, Chen Y, Liu D, Yang H, Quan J, Huo C, Liu J, Yu L. Liang-Ge-San, a classic traditional Chinese medicine formula, attenuates acute inflammation in zebrafish and RAW 264.7 cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2020;249(112427) doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.112427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y, Takagi N, Yuan B, Zhou Y, Si N, Wang H, Yang J, Wei X, Zhao H, Bian B. The protection of indolealkylamines from LPS-induced inflammation in zebrafish. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019;243(112122) doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.112122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shan MQ, Wang TJ, Jiang YL, Yu S, Yan H, Zhang L, Wu QN, Geng T, Huang WZ, Wang ZZ, Xiao W. Comparative analysis of sixteen active compounds and antioxidant and anti-influenza properties of Gardenia jasminoides fruits at different times and application to the determination of the appropriate harvest period with hierarchical cluster analysis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019;233:169–178. doi: 10.3390/antiox8010013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ozal SA, Turkekul K, Gurlu V, Guclu H, Erdogan S. Esculetin protects human retinal pigment epithelial cells from lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation and cell death. Curr Eye Res. 2018;43:1169–1176. doi: 10.1080/02713683.2018.1481517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tao L, Qiu Y, Fu X, Lin R, Lei C, Wang J, Lei B. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 activator diminazene aceturate prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation by inhibiting MAPK and NF-κB pathways in human retinal pigment epithelium. J Neuroinflammation. 2016;13(35) doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0489-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duan X, Gao S, Li J, Wu L, Zhang Y, Li W, Zhao L, Chen J, Yang S, Sun G, Li B. Acute arsenic exposure induces inflammatory responses and CD4+ T cell subpopulations differentiation in spleen and thymus with the involvement of MAPK, NF-κB, and Nrf2. Mol Immunol. 2017;81:160–172. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vaure C, Liu Y. A comparative review of toll-like receptor 4 expression and functionality in different animal species. Front Immunol. 2014;5(316) doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang L, Schmidt S, Larsen PP, Meyer JH, Roush WR, Latz E, Holz FG, Krohne TU. Efficacy of novel selective NLRP3 inhibitors in human and murine retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Mol Med (Berl) 2019;97:523–532. doi: 10.1007/s00109-019-01753-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Su Q, Yao J, Sheng C. Geniposide attenuates LPS-induced injury via up-regulation of miR-145 in H9c2 cells. Inflammation. 2018;41:1229–1237. doi: 10.1007/s10753-018-0769-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koo HJ, Lim KH, Jung HJ, Park EH. Anti-inflammatory evaluation of gardenia extract, geniposide and genipin. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;103:496–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hwang SM, Lee YJ, Yoon JJ, Lee SM, Kang DG, Lee HS. Gardenia jasminoides inhibits tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced vascular inflammation in endothelial cells. Phytother Res. 2010;24 (Suppl 2):S214–S219. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin WH, Kuo HH, Ho LH, Tseng ML, Siao AC, Hung CT, Jeng KC, Hou CW. Gardenia jasminoides extracts and gallic acid inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation by suppression of JNK2/1 signaling pathways in BV-2 cells. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2015;18:555–562. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang J, Hou J, Zhang P, Li D, Zhang C, Liu J. Geniposide reduces inflammatory responses of oxygen-glucose deprived rat microglial cells via inhibition of the TLR4 signaling pathway. Neurochem Res. 2012;37:2235–2248. doi: 10.1007/s11064-012-0852-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fu Y, Liu B, Liu J, Liu Z, Liang D, Li F, Li D, Cao Y, Zhang X, Zhang N, Yang Z. Geniposide, from Gardenia jasminoides Ellis, inhibits the inflammatory response in the primary mouse macrophages and mouse models. Int Immunopharmacol. 2012;14:792–798. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nam KN, Park YM, Jung HJ, Lee JY, Min BD, Park SU, Jung WS, Cho KH, Park JH, Kang I, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of crocin and crocetin in rat brain microglial cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;648:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yorgun MA, Rashid K, Aslanidis A, Bresgen C, Dannhausen K, Langmann T. Crocin, a plant-derived carotenoid, modulates microglial reactivity. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2017;12:245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrep.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kassumeh S, Wertheimer CM, Ohlmann A, Priglinger SG, Wolf A. Cytoprotective effect of crocin and trans-resveratrol on photodamaged primary human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2019;(1120672119895967) doi: 10.1177/1120672119895967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao H, Wang R, Ye M, Zhang L. Genipin protects against H2O2-induced oxidative damage in retinal pigment epithelial cells by promoting Nrf2 signaling. Int J Mol Med. 2019;43:936–944. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.4027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lv B, Chen T, Xu Z, Huo F, Wei Y, Yang X. Crocin protects retinal ganglion cells against H2O2-induced damage through the mitochondrial pathway and activation of NF-κB. Int J Mol Med. 2016;37:225–232. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen L, Qi Y, Yang X. Neuroprotective effects of crocin against oxidative stress induced by ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat retina. Ophthalmic Res. 2015;54:157–168. doi: 10.1159/000439026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qi Y, Chen L, Zhang L, Liu WB, Chen XY, Yang XG. Crocin prevents retinal ischaemia/reperfusion injury-induced apoptosis in retinal ganglion cells through the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway. Exp Eye Res. 2013;107:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laabich A, Vissvesvaran GP, Lieu KL, Murata K, McGinn TE, Manmoto CC, Sinclair JR, Karliga I, Leung DW, Fawzi A, Kubota R. Protective effect of crocin against blue light- and white light-mediated photoreceptor cell death in bovine and primate retinal primary cell culture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:3156–3163. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sepahi S, Mohajeri SA, Hosseini SM, Khodaverdi E, Shoeibi N, Namdari M, Tabassi SAS. Effects of crocin on diabetic maculopathy: A placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;190:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamauchi M, Tsuruma K, Imai S, Nakanishi T, Umigai N, Shimazawa M, Hara H. Crocetin prevents retinal degeneration induced by oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stresses via inhibition of caspase activity. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;650:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.09.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ohno Y, Nakanishi T, Umigai N, Tsuruma K, Shimazawa M, Hara H. Oral administration of crocetin prevents inner retinal damage induced by N-methyl-D-aspartate in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;690:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ishizuka F, Shimazawa M, Umigai N, Ogishima H, Nakamura S, Tsuruma K, Hara H. Crocetin, a carotenoid derivative, inhibits retinal ischemic damage in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;703:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nitta K, Nishinaka A, Hida Y, Nakamura S, Shimazawa M, Hara H. Oral and ocular administration of crocetin prevents retinal edema in a murine retinal vein occlusion model. Mol Vis. 2019;25:859–868. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.