Abstract

Background:

Anxiety symptoms are common in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) and usually confer worse treatment outcomes. The long-term, open-label AtWoRC study in working patients with MDD treated with vortioxetine demonstrated a significant correlation between severity of anxiety symptoms and impaired work productivity. This analysis was undertaken to further explore clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes in patients with different levels of severity of anxiety symptoms at baseline.

Methods:

Post hoc analysis in 199 working patients with MDD treated with vortioxetine (10–20 mg/day), stratified by Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) score at baseline [mild/moderate anxiety (GAD-7 ⩽14), n = 83; severe anxiety (GAD-7 ⩾15), n = 116]. Associations were examined between GAD-7 and other outcome assessment scores at baseline. Observed mean changes from baseline to week 52 were compared between groups.

Results:

Patients with severe anxiety had significantly worse depressive and cognitive symptoms, functioning, and work productivity at baseline than those with mild/moderate anxiety, but similar cognitive performance. Statistically significant improvements from baseline were seen for all outcomes after 52 weeks of vortioxetine treatment, with no significant differences observed between the two groups after adjustment for baseline anxiety scores.

Conclusion:

Treatment with vortioxetine was associated with long-term improvement in clinical symptoms and measures of work productivity in patients with MDD in a real-world setting, irrespective of severity of anxiety symptoms at the start of treatment.

Keywords: anxiety, cognitive bias, cognitive symptoms, major depressive disorder, vortioxetine, work productivity

Introduction

Anxiety symptoms are common in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) and usually confer worse treatment outcomes. Up to 90% of patients with MDD also experience clinically significant symptoms of anxiety.1–6 Anxiety symptoms have been shown to contribute to poor response to treatment in patients with MDD, including lower rates of remission, increased risk of recurrence and greater functional impairment.4–10 Patients with MDD and pronounced anxiety symptoms typically also exhibit a higher degree of negativity, influencing their perception and judgment of reality, in what is known as cognitive bias.11–13 Increased suicidal ideation and rates of suicide have also been reported in MDD patients with high-level anxiety symptoms.8,14

Anxiety symptoms may also contribute to impairments in work productivity in patients with MDD.15 Patients with MDD experience a variety of impairments in work productivity, including having to take time off from work (absenteeism) and not being fully productive when at work (presenteeism).16 AtWoRC (Assessment in Work productivity and the Relationship with Cognitive symptoms) was an interventional, open-label study designed primarily to assess the association between cognitive symptoms and work productivity in working patients with MDD (defined as working ⩾20 h/week or enrolled full time in post-secondary studies or vocational training) who received vortioxetine in a real-word setting in Canada.17 Results showed a highly significant and predictive relationship between long-term improvements in cognitive symptoms and work productivity.18 A highly significant correlation between the severity of anxiety symptoms and impairment in work productivity was also observed.18

There is a scarcity of studies investigating work productivity and anxiety symptoms in working patients with MDD and, in particular, a lack of studies with long-term follow up. This post hoc analysis of the AtWoRC study was therefore undertaken to further explore clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes in patients with different levels of severity of anxiety symptoms at baseline, with particular focus on the correlation between anxiety severity and specific domains of workplace productivity and functioning.

Methods

Study design

AtWoRC was a 52-week, open-label, interventional study in gainfully employed patients with MDD treated with vortioxetine (10–20 mg/day flexible dosing) conducted in a real-world setting at 26 sites across Canada [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02332954]. Patients were treated with vortioxetine at the doses determined appropriate by the investigator and in accordance with the product monograph, meaning that the starting dose could be 5 mg/day. Adult patients (aged 18–65 years) with a current diagnosis of MDD [Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders (DSM-5™) criteria],19 who were in gainful employment (volunteer or paid work ⩾20 h/week), or enrolled full-time in post-secondary studies or vocational training received oral vortioxetine (10–20 mg/day) and were assessed at routine care visits over 52 weeks. Patients were stratified according to whether they were receiving vortioxetine as a first treatment for the current depressive episode or switching to vortioxetine due to inadequate response to a previous antidepressant.

Other inclusion criteria were: duration of current major depressive episode ⩽3 months; Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self-Report (QIDS-SR) score ⩾15; and presence of cognitive symptoms [20-item Perceived Deficits Questionnaire–Depression (PDQ-D-20) score ⩾30]. Patients with a Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST) score >69 at screening/baseline, diagnosis or history of mania or hypomania, schizophrenia or any other psychotic disorder (including MDD with psychotic features), personality disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, mental retardation, pervasive development disorder, organic mental disorders, or mental disorder due to a general medical condition (DSM-5 criteria) were excluded. Patients with previous exposure to vortioxetine or current depressive symptoms considered resistant to antidepressant treatment (failure to respond to at least two previous antidepressants administered at the maximum recommended dose for ⩾6 weeks) were also excluded. Patients with MDD and comorbid generalized anxiety disorder could potentially have been included. However, participating patients were not permitted to receive other pharmacotherapy for MDD or psychoactive medications during the study period.

Ethical approval was obtained from the necessary committees for each study site. All patients provided written informed consent to participate.

Study assessments

Patients were assessed at baseline and at 4, 8, 12, 26, 39, and 52 weeks following vortioxetine initiation. Severity of anxiety symptoms was assessed using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale.20 This questionnaire measures the severity of anxiety symptoms over the past 2 weeks. Each of the seven items is scored from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). The total score ranges from 0 to 21; scores of 5, 10, and 15 are taken as the lower cut-off points for mild, moderate, and severe anxiety, respectively, as previously determined.20

Overall severity of depression was assessed by patients using the QIDS-SR and by clinicians using the Clinical Global Impressions–Severity scale (CGI-S).21,22 Severity of cognitive symptoms was self-reported by patients using the PDQ-D-20.23 Objectively measured cognitive performance was assessed by the DSST.24 Global functioning was assessed by the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) and the 12-item World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS).25–27 For all scales except the DSST, higher scores indicate more severe impairment; for the DSST, higher scores indicate better cognitive performance.

Self-reported work productivity impairments were assessed using the Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ) and the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire.28–30 The WLQ assesses the proportion of time during the previous 2 weeks during which health problems interfered with the ability to work, as measured by 25 items divided across four subscales (time management, physical demands, mental-interpersonal demands, and output demands).28,29 Items are rated from 1 (all of the time) to 5 (none of the time), with subscale scores ranging from 0% (limited none of the time) to 100% (limited all of the time). The WLQ productivity loss score is derived from a weighted sum of the scores from the four WLQ subscales (known as the WLQ Index), which is then converted to generate a percentage productivity loss estimate relative to healthy controls (range 0–25%). The WPAI assesses the impact of a health problem and symptom severity on work productivity over the past 7 days in terms of absenteeism (percent work time missed), presenteeism (percent time impaired at work), and overall work productivity loss (percent overall work impairment).30

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were recorded based on patients’ responses to open-ended questions, and the rate of treatment discontinuation was calculated.

Statistical analysis

The population for the efficacy analysis comprised all patients who met the study inclusion criteria, received at least one dose of vortioxetine, had a valid baseline assessment, and attended at least one post-baseline visit (full analysis set). For analysis of vortioxetine dosage, if any patient had a missing end date for the last dose, the missing end date was imputed using the last visit date for that patient. All other analyses were conducted on observed cases; missing data were not replaced. All enrolled patients who received at least one dose of vortioxetine were included in the safety analysis (all treated patients).

Patients were stratified into two groups according to the severity of their anxiety symptoms at the start of vortioxetine treatment. Mild/moderate anxiety symptoms were defined as a GAD-7 score ⩽14, while severe anxiety symptoms were defined as a GAD-7 score ⩾15. Independent sample t tests were used to compare baseline mean assessment scores and observed mean changes from baseline to week 52 between groups. Paired t tests were used to test for significant improvement from baseline to weeks 12 and 52. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to evaluate baseline associations between GAD-7 scores and other clinical assessments. Adjusted mean changes from baseline to post-baseline visits were analyzed using mixed-effects model for repeated measures (MMRM), with fixed effects of baseline anxiety group, visit, baseline anxiety group-by-visit interaction, and baseline assessment values as covariates.

The MMRM analysis was undertaken using PROC MIXED in SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All other analyses were performed using R (version 3.6.1).31

Results

Study population

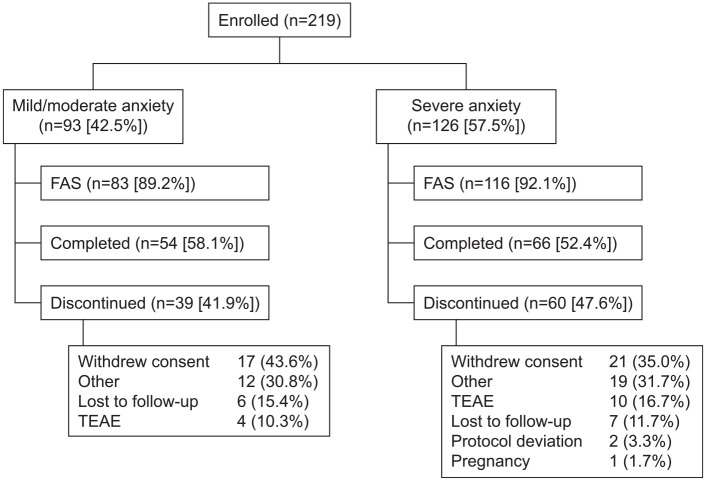

A total of 219 patients with MDD were enrolled and received at least one dose of vortioxetine; of these 219 patients, 199 attended at least one post-baseline assessment and were included in the efficacy analysis (83 with mild/moderate anxiety symptoms and 116 with severe anxiety). Mean [standard deviation (SD), range] GAD-7 score was 10.1 (3.5, 1–14) in patients with mild/moderate anxiety and 18.1 (2.1, 15–21) in those with severe anxiety. Patient disposition is summarized in Figure 1. In all, 39 patients (41.9%) with mild/moderate anxiety and 60 patients (47.6%) with severe anxiety discontinued the study. Withdrawal of consent was the most common reason for discontinuation in both groups (Figure 1). Baseline demographics and characteristics according to the level of anxiety symptoms at baseline are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Patient disposition.

FAS, full analysis set; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and disease characteristics according to severity of anxiety symptoms at the start of vortioxetine treatment (full analysis set).

| Severity of anxiety symptoms at baseline | p value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mild/moderate (GAD-7 ⩽14) | Severe (GAD-7 ⩾15) | ||

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Patients, n | 83 | 116 | |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 41.3 ± 12.7 | 39.7 ± 12.5 | |

| Female, n (%) | 52 (62.7) | 86 (74.1) | |

| White, n (%) | 75 (90.4) | 113 (97.4) | |

| Time since first diagnosis of MDD (years), mean ± SD | 9.3 ± 10.3 | 7.6 ± 8.9 | |

| Vortioxetine dose (mg/day), mean ± SD | |||

| Baseline | 10.0 ± 0.00 | 9.9 ± 0.65 | |

| Week 12 | 15.4 ± 5.02 | 15.5 ± 5.15 | |

| Week 52 | 16.1 ± 4.95 | 14.2 ± 5.22 | |

| Clinical characteristics, mean ± SD score | |||

| CGI-S | 4.04 ± 0.45 | 4.17 ± 0.55 | 0.057 |

| DSST | 46.7 ± 12.0 | 46.4 ± 11.0 | 0.874 |

| PDQ-D-20 | 45.6 ± 10.7 | 52.6 ± 12.2 | <0.001 |

| QIDS-SR | 17.4 ± 2.2 | 19.1 ± 2.7 | <0.001 |

| SDS | 19.3 ± 5.5 | 22.3 ± 4.4 | <0.001 |

| WHODAS 2.0 | 18.4 ± 7.1 | 22.9 ± 7.0 | <0.001 |

| WLQ | |||

| % work productivity loss | 12.2 ± 4.2 | 14.3 ± 4.6 | 0.002 |

| Mental-interpersonal demands | 46.7 ± 18.9 | 56.6 ± 19.1 | <0.001 |

| Output demands | 48.1 ± 22.3 | 56.2 ± 24.5 | 0.017 |

| Physical demands | 25.5 ± 20.6 | 34.5 ± 22.0 | 0.005 |

| Time management | 53.8 ± 19.9 | 60.7 ± 23.4 | 0.027 |

| WPAI | |||

| % total work loss | 65.3 ± 24.3 | 70.0 ± 22.3 | 0.178 |

| Absenteeism | 18.9 ± 25.5 | 24.6 ± 30.4 | 0.162 |

| Presenteeism | 59.1 ± 23.1 | 63.2 ± 22.5 | 0.226 |

Testing differences in observed baseline scores (assuming unequal variance between anxiety symptom groups). Significant at p < 0.05 (bold).

CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions–Severity scale (score range 1–7); DSST, Digit Symbol Substitution Test (score range 0–100); GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (total score range 0–21); PDQ-D-20, 20-item Perceived Deficits Questionnaire-Depression (total score range 0–80); MDD, major depressive disorder; QIDS-SR, Quick Inventory of Depression Symptomatology–self report (total score range 0–27); SD, standard deviation; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale (total score range 0–30); WHODAS, World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (total score range 0–100); WLQ, Work Limitations Questionnaire (total score range 0–25%); WPAI, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (total score range 0–100%).

Patients with severe anxiety symptoms at baseline had significantly worse PDQ-D-20, QIDS-SR, SDS, and WHODAS scores than those with mild/moderate anxiety (all p < 0.001), while CGI-S and DSST scores were similar in the two groups (p = 0.057 and 0.874, respectively). At baseline, patients with severe anxiety also had significantly greater impairment in work productivity assessed using the WLQ than those with mild/moderate anxiety (p = 0.002); however, levels of impairment according to the WPAI were not statistically different between the two groups (p = 0.178). Baseline correlation coefficients supported strong and significant associations between anxiety symptoms and other patient-reported outcome measures (PDQ-D-20 and QIDS-SR), functioning (SDS and WHODAS), and work productivity (WLQ total and subscale scores and WPAI total and presenteeism scores), but weaker associations with the objective cognitive performance test (DSST) and WPAI absenteeism score (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pearson correlation coefficients between baseline GAD-7 score and other clinical and work functioning outcomes at the start of vortioxetine treatment (full analysis set).

| Outcome | Pearson correlation coefficient | Significance level |

|---|---|---|

| CGI-S | 0.174 | * |

| DSST | −0.023 | NS |

| PDQ-D-20 | 0.269 | *** |

| QIDS-SR | 0.403 | *** |

| SDS, total score | 0.414 | *** |

| WHODAS | 0.367 | *** |

| WLQ, % work productivity loss | 0.283 | *** |

| Mental–interpersonal demands | 0.329 | *** |

| Output demands | 0.215 | ** |

| Physical demands | 0.253 | *** |

| Time management | 0.180 | * |

| WPAI, % total work loss | 0.214 | ** |

| Absenteeism | 0.135 | NS |

| Presenteeism | 0.202 | ** |

p ⩽ 0.001; **p ⩽ 0.01; *p ⩽ 0.05. NS, not significant (p > 0.05).

CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions–Severity scale; DSST, Digit Symbol Substitution Test; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item; NS, not significant; PDQ-D-20, 20-item Perceived Deficits Questionnaire-Depression); QIDS-SR, Quick Inventory of Depression Symptomatology–Self Report; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale; WHODAS, World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0; WLQ, Work Limitations Questionnaire; WPAI, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment.

The mean ± standard deviation starting dose of vortioxetine was 9.9 ± 0.50 mg and did not differ according to the severity of anxiety (Table 1). At week 52, the mean daily dose of vortioxetine was 14.9 ± 5.81 mg (14.2 ± 5.22 mg and 16.1 ± 4.95 mg in patients with severe and mild/moderate anxiety at baseline, respectively).

Treatment outcomes

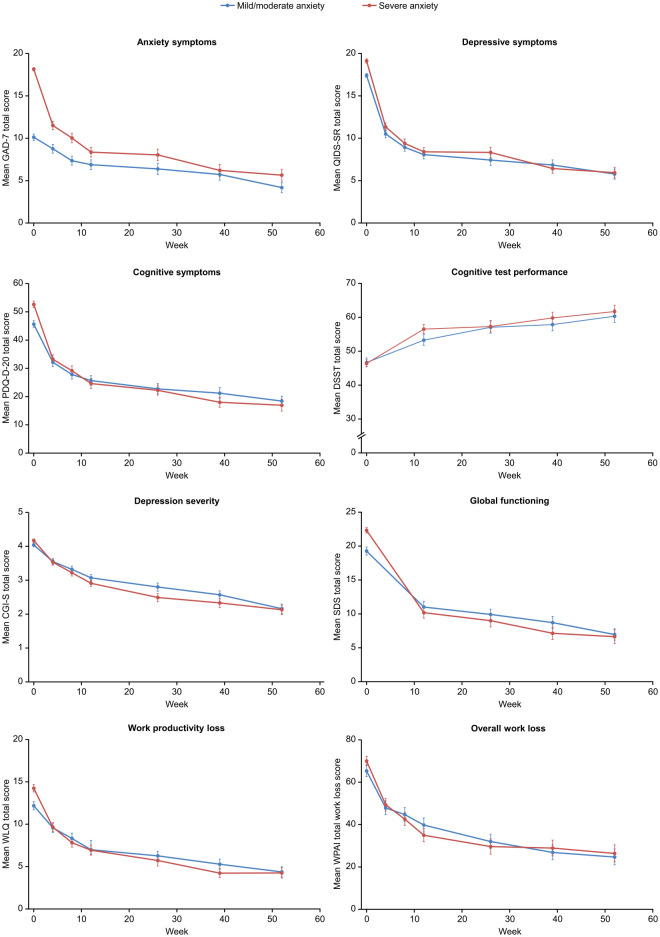

Marked reduction in the severity of anxiety symptoms was seen between baseline and week 4 in both patient groups, with a similar pattern of response observed across other patient-reported assessment measures (Figure 2). Clinically and statistically significant improvements from baseline were seen across all outcome assessments after 12 and 52 weeks of vortioxetine treatment, irrespective of the severity of anxiety symptoms at baseline [all p < 0.001, except for WLQ physical demands and WPAI absenteeism at 12 weeks in patients with mild/moderate anxiety (p = 0.39 and p < 0.05, respectively), and WPAI absenteeism at 12 and 52 weeks (p = 0.0013 and p = 0.02, respectively) in patients with severe anxiety] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Observed mean (standard error) symptom and work productivity scores over 52 weeks of vortioxetine treatment according to severity of anxiety symptoms at baseline (full analysis set). For all scales except the DSST, higher scores indicate more severe impairment; for the DSST, higher scores indicate better cognitive performance.

CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions–Severity scale (score range 1–7); DSST, Digit Symbol Substitution Test (score range 0–100); GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (total score range 0–21); PDQ-D-20, 20-item Perceived Deficits Questionnaire-Depression (total score range 0–80); QIDS-SR, Quick Inventory of Depression Symptomatology–Self Report (total score range 0–27); SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale (total score range 0–30); WLQ, Work Limitations Questionnaire (total score range 0–25%); WPAI, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (total score range 0–100%).

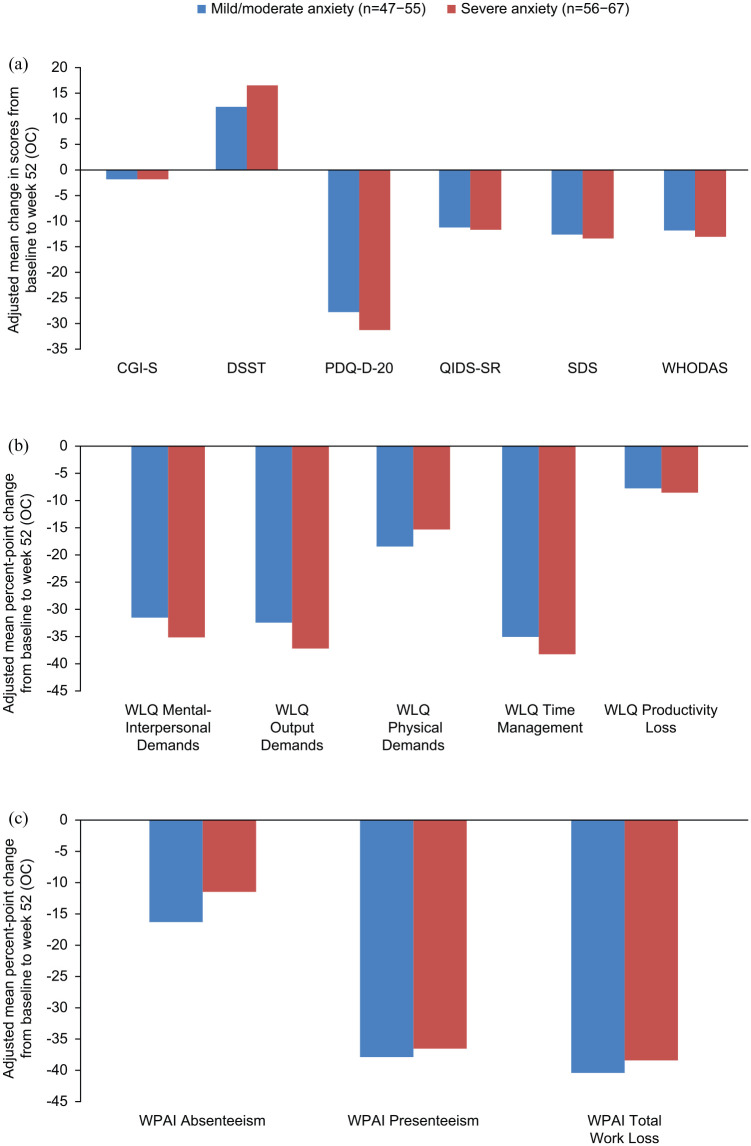

After adjustment for baseline scores, patients with mild/moderate and severe anxiety symptoms responded similarly well to 52 weeks of vortioxetine treatment, with no significant differences between patients with higher and lower levels of anxiety symptoms at baseline (Figure 3); however, different patterns of improvement were observed. Patients with severe anxiety symptoms at baseline showed numerically greater response on measures of mental functioning, such as WLQ mental demands, output demands, and time management scales, while those with mild/moderate anxiety showed numerically greater response on WLQ physical demands and WPAI absenteeism.

Figure 3.

Baseline-adjusted improvements in (a) clinical and functioning outcomes, (b) WLQ outcomes, and (c) WPAI outcomes after 52 weeks of vortioxetine treatment according to severity of anxiety symptoms at baseline (full analysis set). For all scales except the DSST, higher scores indicate more severe impairment; for the DSST, higher scores indicate better cognitive performance.

CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions–Severity scale (score range 1–7); DSST, Digit Symbol Substitution Test (score range 0–100); GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (total score range 0–21); OC, observed cases; PDQ-D-20, 20-item Perceived Deficits Questionnaire-Depression (total score range 0–80); QIDS-SR, Quick Inventory of Depression Symptomatology–Self Report (total score range 0–27); SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale (total score range 0–30); WHODAS, World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (total score range 0–100); WLQ, Work Limitations Questionnaire (total score range 0–25%); WPAI, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (total score range 0–100%).

Safety and tolerability

Treatment with vortioxetine was generally well tolerated. Nausea, anxiety, and dizziness were reported more frequently in patients with severe anxiety symptoms at baseline (Table 3). Four patients (4.3%) with mild/moderate anxiety and 10 (7.9%) with severe anxiety discontinued the study due to TEAEs (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Summary of TEAEs according to severity of anxiety symptoms at baseline (all treated patients).

| TEAEs occurring in >5% of patients in either group, n (%) | Severity of anxiety symptoms at baseline | |

|---|---|---|

| Mild/moderate (GAD-7 ⩽ 14) (n = 93) | Severe (GAD-7 ⩾ 15) (n = 126) | |

| Nausea | 20 (21.5) | 44 (34.9) |

| Headache | 11 (11.8) | 15 (11.9) |

| Insomnia | 9 (9.7) | 11 (8.7) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 7 (7.5) | 8 (6.3) |

| Constipation | 6 (6.5) | 4 (3.2) |

| Anxiety | 4 (4.3) | 10 (7.9) |

| Dizziness | 3 (3.2) | 10 (7.9) |

GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first analysis to explore clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes according to the level of anxiety symptoms in working patients with MDD initiating or switching antidepressant treatment. Greater severity of patient-reported anxiety symptoms at the start of vortioxetine treatment was found to be associated with more severe subjective cognitive symptoms, overall depression severity, and functional impairment, as well as greater impairment in work productivity assessed using the WLQ. Weaker associations with anxiety symptom severity were observed for DSST and CGI-S scores, and all WPAI outcomes. These findings are in keeping with the results of previous analysis of the AtWoRC study, which showed significant correlations between change in GAD-7 total score and other outcome assessments over the 52-week study period.18

The weaker association observed between anxiety symptom severity and objective cognitive performance assessed by the DSST is not unexpected. We have previously shown subjectively rated cognitive symptoms to be a stronger predictor of subsequent functioning outcomes than objective cognitive performance in this study population.18 Other groups have also reported discrepancies between self-reported cognitive symptoms and objective tests of cognitive symptoms in patients with MDD.32–36 The weaker association seen between patient-reported anxiety symptoms and clinician-rated CGI-S score compared with patient-reported measures of depression severity may reflect potential rater bias, for example, it is possible that clinicians assume that patients with MDD who are able to work may have less severe disease.

The observed differences between associations with WLQ and WPAI scores may reflect differences in how work productivity is assessed by these two questionnaires. The WPAI provides a generic and high-level patient-reported assessment of work productivity, including both absenteeism and presenteeism, whereas the WLQ provides a more in-depth assessment of specific mental and physical aspects of productivity in the workplace setting. The lack of baseline differences in WPAI scores between patients with different levels of anxiety symptoms may be due to the objective nature of the questions in this instrument (i.e., percent work time missed in the last week). Such objective questions may be expected to be less influenced by a negative cognitive bias and therefore more likely to be independent of anxiety symptom severity compared with questions that ask the patient if they are feeling impaired in doing specific work-related tasks as in the WLQ.

Marked reduction in the severity of anxiety symptoms was seen during the first 4 weeks of treatment in both patient groups, with a similar pattern of rapid response observed across other patient-reported assessment measures. AtWoRC was an open-label study and therefore patients were aware that they were receiving active treatment; this anticipation may have contributed to the observed rapid improvements. However, early improvements in anxiety symptoms from baseline have also been reported in previous double-blind studies of vortioxetine in patients with MDD and high levels of anxiety,37,38 and in patients with anxiety disorders.39,40

Significant improvements in all outcome measures were observed after 12 and 52 weeks of vortioxetine treatment in patients with severe anxiety symptoms at the start of treatment, as well as in those with mild/moderate anxiety. Other studies have also shown vortioxetine to be effective for the treatment of MDD in patients with high levels of concomitant anxiety symptoms at the start of treatment.38,41 Despite the weaker association between anxiety symptom severity and objective cognitive performance at baseline, patients with a high level of anxiety symptoms showed numerically greater improvements in both adjusted mean PDQ-D-20 and DSST scores from baseline to week 52 than those with mild or moderate levels of anxiety at the start of treatment.

It could be speculated that the difference in improvement seen between the two groups of working patients with different levels of anxiety symptoms may be due to cognitive bias, which is well documented in patients with mood and anxiety disorders.11–13 Self-assessed cognitive symptoms might be expected to be affected heavily by negative cognitive bias, which, in turn, would be expected to be more pronounced in highly anxious patients with MDD. As symptoms of depression and anxiety improve with treatment, cognitive bias would also be expected to be reduced, resulting in corresponding improvements in self-reported cognitive symptoms, as evidenced by the greater improvement in PDQ-D-20 score in highly anxious patients compared with less anxious patients in the present study. Although objective assessment of cognitive performance might be expected to be independent of cognitive bias, attention and working memory – domains responsible for cognitive performance – may also be impacted by cognitive bias in depression.11,12 As such, treatment-induced reductions in cognitive bias in highly anxious patients may also remove impediments to cognitive performance, resulting in the numerically greater improvements in DSST scores seen in patients with severe anxiety at baseline in the current study.

Of note, patients with more severe anxiety responded more robustly on measures of mental functioning related to presenteeism, suggesting that physical demands and absenteeism may be harder to treat in more anxious patients with MDD. Cognitive bias has been shown to be associated with hyperfunction in the prefrontal cortex.42 It is therefore reasonable to assume that, as anxiety symptoms improve, cognitive bias and the patient’s perspective and evaluation of work productivity will also improve, particularly in domains measuring mental aspects of work productivity or presenteeism. Conversely, physical demands and absenteeism would be expected to be less affected by cognitive bias and, therefore, improvement in cognitive bias with treatment would have less impact on these domains of work productivity. Consequently, it is possible that high levels of anxiety symptoms may make it harder for patients with MDD to physically return to work, preventing reintegration into the workforce.

The proportion of patients who discontinued the study was similar in the two anxiety groups, with withdrawal of consent the most common reason for study discontinuation in both groups. Treatment with vortioxetine was generally well tolerated, with a tolerability profile in keeping with that reported in recent meta-analyses.38,43 However, nausea, anxiety, and dizziness were more frequently reported in patients with severe anxiety at baseline than in those with mild/moderate anxiety.

Strengths of this analysis include the unique study population of gainfully employed patients with MDD treated with vortioxetine in a real-world setting, and that both clinician-assessed and patient-reported outcome measures were used to assess depression severity and impact. Categorization of patients into two groups based on severity of anxiety symptoms could be considered a potential limitation of the current analysis and a regression analysis with the total GAD-7 scores could perhaps strengthen the results. However, the cut-off levels used to determine severity of anxiety in this study (mild/moderate anxiety symptoms, GAD-7 score ⩽14; severe anxiety symptoms, GAD-7 score ⩾15) were based on the thresholds for mild, moderate, and severe levels of anxiety determined during validation of the GAD-7 scale (5, 10, and 15 points, respectively).20 Furthermore, in routine practice settings, outpatients with MDD are likely to be characterized based on the presence or absence of severe anxiety symptoms, rather than on quantified anxiety scores. Other potential limitations are the post hoc nature of the current analysis and the relatively small sample sizes in the two subgroups.

Conclusion

Our findings in working patients with MDD and different levels of anxiety symptoms highlight that treatment with vortioxetine conferred robust and long-term benefits across clinical symptom and work productivity domains in a real-world setting, irrespective of the patient’s level of anxiety symptoms at the start of treatment. In addition, the observed patterns of improvement across domains of workplace productivity in patients with varying degrees of anxiety symptoms may generate hypotheses for further studies on the occupational impairments experienced by working patients with MDD.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank JSS Medical Research, the contract research organization mandated to manage the AtWoRC study, and the following principal investigators at the participating study sites: Sunny Johnson, Pratap Chokka, Paul Latimer, Brian Ramjattan, Mark Johnston, Michael O’Mahony, Sean Peterson, William O’Mahony, Murray Awde, Michael Csanadi, Ranjith Chandrasena, Preston Zuliani, Peter Turner, Richard Tytus, Jeannette Janzen, Guy Chouinard, Giuseppe Mazza, Denis Beaulieu, Valérie Tourjman, François Blouin, Marie-Chantal Ménard, Benicio Frey, Hani Iskandar, Arun Nayar, Jasmin Belle-Isle, and Ethel Bellavance. Medical writing assistance was provided by Jennifer Coward, Anthemis Consulting Ltd, Bollington, UK.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: P.C. has received research grants and honoraria for serving on advisory boards and for speaking engagements from Allergan, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Shire, Purdue, and Janssen. H.G. was an employee of Lundbeck Singapore Pte Ltd, Singapore at the time of this analysis. J.B. and G.C. are employees of Lundbeck Canada Inc. A.E. is an employee of H. Lundbeck A/S.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The AtWoRC study was funded by Lundbeck Canada Inc. Medical writing assistance was funded by H. Lundbeck A/S.

ORCID iD: Pratap Chokka  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1043-8554

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1043-8554

Contributor Information

Pratap Chokka, Grey Nuns Community Hospital, 1100 Youville Drive West, Edmonton, Alberta T6L 5X8, Canada.

Holly Ge, Lundbeck Singapore Pte Ltd, Singapore.

Joanna Bougie, Lundbeck Canada Inc., Montreal, Canada.

Anders Ettrup, H. Lundbeck A/S, Valby, Denmark.

Guerline Clerzius, Lundbeck Canada Inc., Montreal, Canada.

References

- 1. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003; 289: 3095–3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kessler RC, Sampson NA, Berglund P, et al. Anxious and non-anxious major depressive disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2015; 24: 210–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yang W, Zhang G, Jia Q, et al. Prevalence and clinical profiles of comorbid anxiety in first episode and drug naïve patients with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 2019; 257: 200–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wiethoff K, Bauer M, Baghai TC, et al. Prevalence and treatment outcome in anxious versus nonanxious depression: results from the German Algorithm Project. J Clin Psychiatry 2010; 71: 1047–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wu Z, Chen J, Yuan C, et al. Difference in remission in a Chinese population with anxious versus nonanxious treatment-resistant depression: a report of OPERATION study. J Affect Disord 2013; 150: 834–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fava M, Rush AJ, Alpert JE, et al. Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165: 342–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jakubovski E, Bloch MH. Prognostic subgroups for citalopram response in the STAR*D trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2014: 75: 738–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lin C-H, Wang F-C, Lin S-C, et al. A comparison of inpatients with anxious depression to those with nonanxious depression. Psychiatry Res 2014; 220: 855–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Saveanu R, Etkin A, Duchemin AM, et al. The international Study to Predict Optimized Treatment in Depression (iSPOT-D): outcomes from the acute phase of antidepressant treatment. J Psychiatr Res 2015; 61: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gaspersz R, Nawijn L, Lamers F, et al. Patients with anxious depression: overview of prevalence, pathophysiology and impact on course and treatment outcome. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2018; 31: 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Disner SG, Beevers CG, Haigh EAP, et al. Neural mechanisms of the cognitive model of depression. Nat Rev Neurosci 2011; 12: 467–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Beck AT, Bredemeier K. A unified model of depression: integrating clinical, cognitive, biological, and evolutionary perspectives. Clin Psychol Sci 2016; 4: 596–619. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gold AK, Montana RE, Sylvia LG, et al. Cognitive remediation and bias modification strategies in mood and anxiety disorders. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep 2016; 3: 340–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Seo HJ, Jung YE, Kim TS, et al. Distinctive clinical characteristics and suicidal tendencies of patients with anxious depression. J Nerv Ment Dis 2011; 199: 42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Birnbaum HG, Kessler RC, Kelley D, et al. Employer burden of mild, moderate, and severe major depressive disorder: mental health services utilization and costs, and work performance. Depress Anxiety 2010; 27: 78–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hendriks SM, Spijker J, Licht CM, et al. Long-term work disability and absenteeism in anxiety and depressive disorders. J Affect Disord 2015; 178: 121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chokka P, Bougie J, Rampakakis E, et al. Assessment in Work productivity and the Relationship with Cognitive symptoms (AtWoRC): primary analysis from a Canadian open-label study of vortioxetine in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD). CNS Spectr 2019; 24: 338–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chokka P, Bougie J, Proulx J, et al. Long-term functioning outcomes are predicted by cognitive symptoms in working patients with major depressive disorder treated with vortioxetine: results from the AtWoRC study. CNS Spectr 2019; 24: 616–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166: 1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, et al. The 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 54: 573–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guy W. (ed.). ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Public Health Service Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lam RW, Lamy FX, Danchenko N, et al. Psychometric validation of the Perceived Deficits Questionnaire-Depression (PDQ-D) instrument in US and UK respondents with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2018; 14: 2861–2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wechsler D. Wechsler adult intelligence scale—revised. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Raj BA. The measurement of disability. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1996; 11(Suppl. 3): 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sheehan KH, Sheehan DV. Assessing treatment effects in clinical trials with the discan metric of the Sheehan disability scale. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2008; 23: 70–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ustün TB, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, et al. Developing the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. Bull World Health Org 2010; 88: 815–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lerner D, Amick BC, III, Rogers WH, et al. The work limitations questionnaire. Med Care 2001; 39: 72–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lerner D, Amick BC, III, Lee JC, et al. Relationship of employee-reported work limitations to work productivity. Med Care 2003; 41: 649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Duke EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics 1993; 4: 353–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, https://www.R-project.org/ (2018, accessed February 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lam RW, Iverson GL, Evans VC, et al. The effects of desvenlafaxine on neurocognitive and work functioning in employed outpatients with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 2016; 203: 55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cha DS, Carmona NE, Subramaniapillai M, et al. Cognitive impairment as measured by the THINC-integrated tool (THINC-it): association with psychosocial function in major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 2017; 222: 14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Srisurapanont M, Suttajit S, Eurviriyanukul K, et al. Discrepancy between objective and subjective cognition in adults with major depressive disorder. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 3901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fava M, Mahableshwarkar AR, Jacobson W, et al. What is the overlap between subjective and objective cognitive impairments in MDD? Ann Clin Psychiatry 2018; 30: 176–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schwert C, Stohrer M, Aschenbrenner S, et al. Biased neurocognitive self-perception in depressive and in healthy persons. J Affect Disord 2018; 232: 96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Alvarez E, Perez V, Dragheim M, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, active reference study of Lu AA21004 in patients with major depressive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2012; 15: 589–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Baldwin DS, Florea I, Jacobsen PL, et al. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of vortioxetine in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) and high levels of anxiety symptoms. J Affect Disord 2016; 206: 140–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bidzan L, Mahableshwarkar AR, Jacobsen P, et al. Vortioxetine (Lu AA21004) in generalized anxiety disorder: results of an 8-week, multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2012; 22: 847–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liebowitz MR, Careri J, Blatt K, et al. Vortioxetine versus placebo in major depressive disorder comorbid with social anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety 2017; 34: 1164–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vieta E, Loft H, Florea I. Effectiveness of long-term vortioxetine treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2017; 27: 877–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Browning M, Holmes EA, Murphy SE, et al. Lateral prefrontal cortex mediates the cognitive modification of attentional bias. Biol Psychiatry 2010; 67: 919–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Baldwin DS, Chrones L, Florea I, et al. The safety and tolerability of vortioxetine: analysis of data from randomized placebo-controlled trials and open-label extension studies. J Psychopharmacol 2016; 30: 242–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]