Abstract

Objective

The mutation of the ‘telomerase reverse transcriptase gene promoter’ (TERTp) has been identified as an important factor for individual prognostication and tumorigenesis and will be implemented in upcoming glioma classifications. Uptake characteristics on dynamic 18F-FET PET have been shown to serve as additional imaging biomarker for prognosis. However, data on the correlation of TERTp-mutational status and amino acid uptake on dynamic 18F-FET PET are missing. Therefore, we aimed to analyze whether static and dynamic 18F-FET PET parameters are associated with the TERTp-mutational status in de-novo IDH-wildtype glioblastoma and whether a TERTp-mutation can be predicted by dynamic 18F-FET PET.

Methods

Patients with de-novo IDH-wildtype glioblastoma, WHO grade IV, available TERTp-mutational status and dynamic 18F-FET PET scan prior to any therapy were included. Here, established clinical parameters maximal and mean tumor-to-background-ratios (TBRmax/TBRmean), the biological-tumor-volume (BTV) and minimal-time-to-peak (TTPmin) on dynamic PET were analyzed and correlated with the TERTp-mutational status.

Results

One hundred IDH-wildtype glioblastoma patients were evaluated; 85/100 of the analyzed tumors showed a TERTp-mutation (C228T or C250T), 15/100 were classified as TERTp-wildtype. None of the static PET parameters was associated with the TERTp-mutational status (median TBRmax 3.41 vs. 3.32 (p=0.362), TBRmean 2.09 vs. 2.02 (p=0.349) and BTV 26.1 vs. 22.4 ml (p=0.377)). Also, the dynamic PET parameter TTPmin did not differ in both groups (12.5 vs. 12.5 min, p=0.411). Within the TERTp-mutant subgroups (i.e., C228T (n=23) & C250T (n=62)), the median TBRmax (3.33 vs. 3.69, p=0.095), TBRmean (2.08 vs. 2.09, p=0.352), BTV (25.4 vs. 30.0 ml, p=0.130) and TTPmin (12.5 vs. 12.5 min, p=0.190) were comparable, too.

Conclusion

Uptake characteristics on dynamic 18F-FET PET are not associated with the TERTp-mutational status in glioblastoma However, as both, dynamic 18F-FET PET parameters as well as the TERTp-mutation status are well-known prognostic biomarkers, future studies should investigate the complementary and independent prognostic value of both factors in order to further stratify patients into risk groups.

Keywords: amino acid PET, molecular genetics, glioblastoma, TERT (telomerase reverse transcriptase), FET PET

Introduction

According to the updated 2016 WHO classification of brain tumors, the molecular genetic profile plays a major role for the glioma characterization and highly affects the further clinical management and treatment strategies (1, 2). Beyond the current molecular genetic stratification using the isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)-mutational status and 1p/19q-codeletion, additional molecular genetic markers are increasingly identified and gradually gain access into clinical routine. In particular, mutations of the telomerase reverse transcriptase gene promoter (TERTp) were identified as important factor within the tumorigenesis and individual prognostication (3, 4), with inferior outcome in combination with an IDH-wildtype status (5, 6), which will be implemented in upcoming glioma classifications.

As recommended by the Response assessment in Neurooncology (RANO) working group in their clinical guidelines (7–9), molecular imaging using positron-emission-tomography (PET) with radiolabeled amino acids such as O-(2-18F-fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine (18F-FET) is increasingly used for the comprehensive evaluation and characterization of brain neoplasms beyond morphological standard imaging with MRI, e. g. for treatment planning (10–13), but also for noninvasive tumor characterization at initial diagnosis (14–20). Recent studies indicated that the IDH-mutational status is highly associated with 18F-FET PET uptake in brain tumors, especially with the ‘minimal time to peak’ (TTPmin) on dynamic 18F-FET PET, and has thus a high diagnostic power for the identification of IDH-wildtype gliomas (21). With regard to TERTp, no study has hitherto evaluated the association of amino acid uptake on PET and the TERTp-mutational status. Hence, we aimed to assess whether the uptake characteristics on static and dynamic 18F-FET PET are likewise associated with the TERTp-mutation status in a homogeneous group of de-novo, IDH-wildtype glioblastoma and whether PET can predict the TERTp-mutation status.

Methods and Materials

Patients

Patients with histologically confirmed, newly diagnosed IDH-wildtype glioblastoma WHO grade IV with available molecular genetic analyses of the TERT-promoter mutation status as well as a dynamic 18F-FET PET scan prior to stereotactic biopsy or surgical resection were identified. All patients have given written informed consent prior to the PET examination as part of the clinical routine. Ethical approval of the retrospective study protocol was given by the institutional review board of the LMU.

Histological Confirmation, Tumor Grading and Molecular Genetic Analysis

Stereotactic biopsy procedures and microsurgical resections were performed at the Department of Neurosurgery, LMU Munich, Germany. As part of the clinical routine, histopathological and molecular genetic evaluations were performed at the Institute of Neuropathology, LMU Munich, Germany, and were initially classified according to the 2007 WHO classification of brain tumors (22) and were re-classified according to the updated 2016 WHO classification (1). The IDH-mutation status and TERT-promoter methylation were analyzed in clinical routine according to standard protocols (23–25). For further specification regarding the histopathological workup see also (26, 27).

18F-FET PET Image Acquisitionand Data Analysis

18F-FET PET scans were performed at the Department of Nuclear Medicine, LMU. Data of the dynamic 18F-FET PET scans were acquired using an ECAT Exact HR+ scanner (Siemens). After a 15-min transmission scan with a 68Ge rotating rod source, approximately 180 MBq of 18F-FET were injected. Dynamic emission recording was accomplished after tracer injection up to 40 min post injection in 3-D mode consisting of 16 frames (7 x 10 s; 3 x 30 s; 1 x 2 min; 3 x 5 min; 2 x 10 min). Two-dimensional filtered back-projection, reconstruction algorithms using a 5 mm Hann Filter were used for image reconstruction and corrected for photon attenuation and model-based scatter. The mean background activity (BG) was assessed using 6 large crescent-shaped regions of interests (ROI) in the frontal lobe of the healthy contralateral hemisphere fused to a volume of interest (VOI), in which the mean BG was derived (28). The biological tumor volume (BTV) was estimated by a semiautomatic threshold-based delineation of a volume of interest (VOI) using a standardized uptake value (SUV) threshold of 1.6 x BG, as previously described as optimal threshold (29). The maximal SUV (SUVmax) and mean SUV (SUVmean) as derived within the BTV were then divided by the BG resulting in mean and maximal tumor-to-background ratio (TBRmean/TBRmax). Data on dynamic PET was evaluated using the software PET Display Dynamic implemented in the Hermes workstation: in early summation images (10-30 min p.i.), a 90% isocontour region of interest was created to extract the time-activity-curves (TACs) on a slice-by-slice manner. Then, the time to peak (TTP) was assessed on each slice of the tumor and the shortest TTP in at least 2 consecutive slices was defined as minimal TTP (TTPmin), see also (30, 31).

Statistics

SPSS for Windows (version 23.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics are displayed as median (range). Normal distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk-test. The unpaired Wilcoxon-test was used for independent and not-normally distributed continuous parameters. Receiver operating curves (ROC) analyses were used to assess the diagnostic power of continuous parameters, the ‘Area under the curve’ (AUC) served as quantitative measure for the diagnostic power. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed p-value <0.05.

Results

Patients

One-hundred patients with de-novo, IDH-wildtype glioblastoma, WHO grade IV were included (62/100 (62.0%) male, 38/100 (38.0%) female). The median age was 62.0 (range, 30.1-82.7) years. Tissue samples for histological and molecular genetic analyses were obtained by stereotactic biopsy in 74/100 (74.0%) and by surgical resection in 26/100 (26.0%) cases. Overall, 15/100 (15%) did not comprise a TERTp-mutation and were classified as TERTp-wildtype. Of the remaining 85/100 (85%) patients with TERTp-mutation, 62/85 (72.9%) showed a C228T-mutation and 23/85 (27.1%) showed a C250T-mutation.

Overall 18F-FET-Uptake Characteristics

All included gliomas were 18F-FET-positive providing a median TBRmax of 3.37 (2.06-7.07), a median TBRmean of 2.06 (range, 1.70-2.92) and a median BTV of 25.8 (range, 3.8-133.3) ml. In the dynamic analysis, median TTPmin was 12.5 (range, 3.0-35.0) minutes with a small proportion of late TTPmin ≥ 25 minutes in 13/100 (13.0%) cases only.

18F-FET-Uptake Characteristics Comparing TERTp-Mutant and TERTp-Wildtype Glioblastomas and Predictability of TERTp Mutational Status

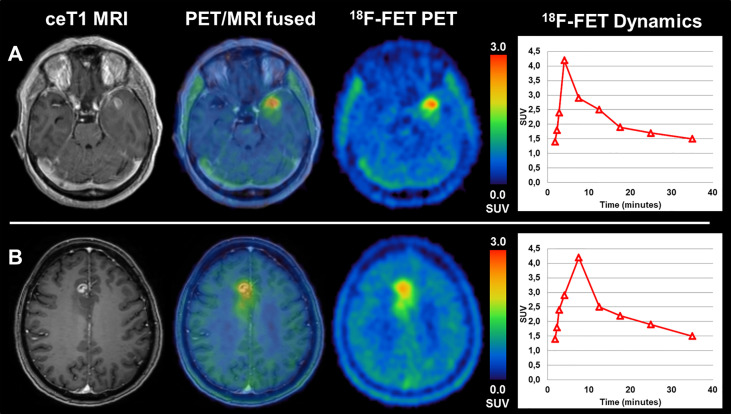

Comparing glioblastomas with TERTp-mutation (n=85) and those without (n=15) revealed no statistically significant difference in terms of median TBRmax (3.41 (range, 2.06-7.07) vs. 3.32 (range, 2.32-4.67), p=0.362), TBRmean (2.09 (range, 1.70-2.92) vs. 2.02 (range, 1.79-2.56), p=0.349) and BTV (26.1 (range, 3.8-133.3) ml vs. 22.4 (range, 3.9-75.7) ml, p=0.377). Not only the evaluated static PET parameters, but also the dynamic parameter TTPmin did not differ between those two groups (12.5 (range, 3.0-35.0) min vs. 12.5 (range, 7.5-25.0) min, p=0.411). By consequence, the ROC-analysis to assess the diagnostic power of 18F-FET PET for the prediction of the TERTp mutational status did not reveal reliable thresholds for the differentiation between TERTp-mutant and TERTp-wildtype glioblastomas. Analyzing the static parameters TBRmax, TBRmean and BTV, the AUC ranged between 0.572 and 0.576 only. Also, for the dynamic parameter TTPmin the AUC reached only 0.562 at a best cut-off at 7.5 min. Further specifications can be found in Table 1 and Table 2 . Patient examples can be found on Figure 1 .

Table 1.

Influence of TERT-mutation on 18F-FET-uptake characteristics [median (range)].

| Overall (n=100) | TERT-mutation (n=85) | TERT-wildtype (n=15) | Level of significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBRmax | 3.37 (2.06-7.07) | 3.41 (2.06-7.07) | 3.32 (2.32-4.67) | p=0.362 |

| TBRmean | 2.06 (1.70-2.92) | 2.09 (1.70-2.92) | 2.02 (1.79-2.56) | p=0.349 |

| BTV | 25.8 (3.8-133.3) ml | 26.1 (3.8-133.3) ml | 22.4 (3.9-75.7) ml | p=0.377 |

| TTPmin | 12.5 (3.0-35.0) min | 12.5 (3.0-35.0) min | 12.5 (7.5-25.0) min | p=0.411 |

Table 2.

Diagnostic power of 18F-FET PET for detection TERTp mutation.

| Parameter | Best cut-off value | Area under the curve | Level of significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| TBRmax | 3.60 | 0.574 | p=0.323 |

| TBRmean | 2.21 | 0.576 | p=0.297 |

| BTV | 24.1 ml | 0.572 | p=0.359 |

| TTPmin | 7.5 min | 0.562 | p=0.391 |

Figure 1.

(A) a patient with TERTp-mutant glioblastoma (TBRmax 4,1; TBRmean 2,3; BTV 15,4 ml, TTPmin 5 min) shows comparable, only slightly diverging imaging features as (B), a patient with TERTp-wildtype glioblastoma (TBRmax 2,9; TBRmean 1,9; BTV 12,3 ml, TTPmin 10 min).

18F-FET-Uptake Characteristics Comparing TERT-Mutation Subtypes (C228T vs. C250T)

Comparing the two subtypes of TERT-promoter mutation C228T (n=62) & C250T (n=23), there was also no statistically significant difference in terms of median TBRmax (3.33 (range, 2.06-5.51) vs. 3.69 (range, 2.37-7.07), p=0.095), TBRmean (2.08 (range, 1.70-2.56) vs. 2.09 (range, 1.79-2.92), p=0.352) or BTV (25.4 (range, 3.8-133.3) ml vs. 30.0 (range, 5.7-102.1) ml, p=0.130). On dynamic PET analyses, the median TTPmin was also statistically comparable between those two mutation subtypes (12.5 (range, 7.5-35.0) min vs. 12.5 (range, 3.0-35.0) min, p=0.190). For further specifications, please see Table 3 .

Table 3.

Influence of TERT-mutation subtypes on 18F-FET-uptake characteristics [median (range)].

| TERT-mutation overall (n = 85) | C228T (n = 62) | C250T (n = 23) | Level of significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBRmax | 3.41 (2.06-7.07) | 3.33 (2.06-5.51) | 3.69 (2.37-7.07) | p=0.095 |

| TBRmean | 2.09 (1.70-2.92) | 2.08 (1.70-2.56) | 2.09 (1.79-2.92) | p=0.352 |

| BTV | 26.1 (3.8-133.3) ml | 25.4 (3.8-133.3) ml | 30.0 (5.7-102.1) ml | p=0.130 |

| TTPmin | 12.5 (3.0-35.0) min | 12.5 (7.5-35.0) min | 12.5 (3.0-35.0) min | p=0.190 |

Discussion

This is the first study evaluating the association of amino acid uptake by means of 18F-FET PET and the TERTp-mutational status in glioma patients. As the TERTp-mutational status has shown additional prognostic value in IDH-wildtype gliomas/glioblastomas (5, 6, 32, 33), a non-invasive tool for the prediction of a TERTp-mutation would be helpful for the clinical management of glioma patients. In our large cohort with homogeneous histological and molecular genetic profile (i.e. WHO grade IV glioblastoma, IDH-wildtype only), we observed a high proportion of patients with TERTp mutation of 85%, which is in line with the proportion of patients with TERTp mutation in the current literature (4). Moreover, within the group of TERTp mutant glioblastomas, the C228T-mutation was present more frequently (72.9%) than the C250T-mutation (27.1%), which is also in line with the distribution within IDH-wildtype glioblastomas as described in the current literature (6, 34).

Comparing the TERTp-mutational status with the static PET parameters in terms of uptake intensity (TBRmax and TBRmean) and tumor extent (BTV), we observed a high overlap between TERTp-mutant and TERTp-wildtype tumors so that no cutoff could be found to differentiate between those groups. Moreover, TTPmin on dynamic PET was also indifferent between TERTp-mutant and TERTp-wildtype glioblastomas. Taken together, both groups presented with comparable imaging findings and could not be distinguished on 18F-FET PET. This leads to the assumption that dynamic 18F-FET PET cannot predict the TERTp-mutational status in IDH-wildtype glioblastoma. Taking a closer look at the IDH-mutational status, however, recent studies indicated that the IDH-mutational status can be identified non-invasively by dynamic 18F-FET PET with a relatively high diagnostic accuracy. In particular, the prognostically poor IDH-wildtype status can be predicted by a short TTPmin on dynamic 18F-FET PET (21).

When analyzing the TERTp-mutation subtypes (i.e. C228T & C250T), expectedly, no difference in terms of uptake-intensity (TBRmax & TBRmean) and tumor extent (i.e. BTV) on PET could be observed; also, TTPmin on dynamic PET was indifferent between C228T & C250T mutations. This finding, however, is not surprising, as these two mutations of hot spot promoter regions (C228T and C250T) are basically responsible for the same molecular mechanism (32, 33).

In general, one could speculate that the pathophysiological changes that are accompanied with TERTp mutations and their influence on cell regulation might also affect the cellular metabolism in terms of amino acid metabolism. Moreover, one could argue that both static and dynamic 18F-FET PET parameters were described to be of prognostic value in the further disease course of glioma patients; as the same is true for TERTp mutations, a certain intercorrelation does not seem unlikely. On a molecular level, the TERT as a catalytic subunit of the telomerase enzyme complex is critically involved in telomere maintenance and lengthening. Abnormal upregulation and activity of TERT as a consequence of TERTp-mutations are considered one of the mechanisms of cellular immortality in cancer cells during division, particularly in gliomas (35–37). With regard to PET imaging, the activity and/or expression of the large neutral amino acid transporter (LAT) at the tumor cells and at the brain capillary endothelial cells (38) is considered a key factor responsible for the intracellular uptake of amino acids in gliomas (39). The very exact mechanisms and the histopathological or even molecular genetic correlate resulting in diverging uptake dynamics of 18F-FET are not fully clarified yet and may be influenced by further factors such as vascularization. Our study findings suggest that the presence or, vice versa, the absence of TERTp-mutation in glioblastoma and the accompanying features on a cellular basis, although prognostically relevant, do neither result in an altered level of amino acid metabolism nor in changes of uptake dynamics on 18F-FET PET.

Notably, there is an occurrence of TERTp-mutations in different tumor types as well, also in molecular subgroups with superior prognosis compared to IDH-wildtype gliomas, e. g. in IDH-mutant gliomas. Interestingly, among IDH-mutant gliomas, IDH-mutant gliomas with TERTp-mutation comprise a superior clinical outcome compared to IDH-mutant glioma without TERTp-mutation, also with emphasis on the particular histological features (5). Therefore, the presence of TERTp-mutations in brain tumors per se is not necessarily linked to a more aggressive course in general. Particularly, in the group of oligodendroglial tumors (i.e. gliomas with both IDH-mutation and 1p/19q-codeletion), basically every tumor presents with TERTp-mutation. This molecular genetic subgroup is associated with favorable outcome compared to e.g. IDH-wildtype gliomas (32, 40), despite a basically general presence of TERTp mutations. These phenomena also warrant further investigation of PET-based imaging characteristics in the subgroup of IDH-mutant gliomas. First preliminary data using radiomic features on MRI could show certain moderate diagnostic power for the detection of TERTp mutations particularly in low-grade/IDH-mutant gliomas (41, 42).

Moreover, a vast body of literature exists dealing with radiomics, deep learning and machine learning with special emphasis on (18F-FET) PET and hybrid imaging in neuro-oncology (43–49), not just for the differentiation of treatment-related changes from real progression (44, 50, 51), but also for the predication of prognostically relevant mutations such as the IDH-mutation (52). Hence, it needs to be evaluated, if further PET-based analyses with the extraction of radiomic features may add value to the conventional image analysis in order to non-invasively identify the TERTp-mutational status. Interestingly, the predictability of key mutations using standard and advanced PET quantification also seems to vary depending on the used radioligands (53–57).

Particularly, as dynamic 18F-FET PET was previously reported to show a high prognostic value in gliomas in addition to the clinically most important molecular genetic biomarkers according to the 2016 WHO classification [IDH-mutation and 1p/19q-codeletion status (14, 26)], it would be interesting to evaluate whether the additional prognostic value of PET remains even after further subgroup stratification according to the TERTp mutation status. In order to test this hypothesis, further studies with a larger number of patients (particularly in the relatively small TERTp-wildtype subgroup) are needed to perform multivariate analyses.

Limitations arise from the retrospective study design. Moreover, as mentioned above, the absolute number of tumors without TERTp mutations is relatively low (i.e. n=15 vs. n=85), however, this proportion is in line with the previously reported distribution of TERTp mutations in glioblastoma. In the current manuscript, only filtered-back projection (FBP) reconstructions were used due to the applied scanner; quantification of PET parameters could potentially be diverging using other reconstruction algorithms such as ordered subset expectation maximization (OSEM).

Conclusion

The prognostically relevant TERTp-mutational status in IDH-wildtype glioblastoma is not associated with uptake characteristics on dynamic 18F-FET PET. As both, dynamic 18F-FET PET parameters as well as the TERTp-mutation status are well-known prognostic biomarkers, but show no association in our analysis, it seems highly interesting to evaluate in larger studies if both factors are independent predictors of patients’ survival and can thereby further stratify patients into risk groups.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics committee, LMU Munich. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MU and NA. Methodology, MU, VR, KR, BS, LM, LB, MB, VW, and WK. Formal analysis, MU, VR, KR, and NA. Resources, all authors. Writing—original draft preparation, MU and NA. Writing—review and editing, all authors. Visualization, MU and NA. Supervision, NA, MN, JH, JT, and PB. Project administration, MU and NA. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

NA is a member of the Neuroimaging Committee of the EANM.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Parts of this paper originate from the doctoral thesis of KR. This work was supported by the Collaborative Research Centre SFB-824 of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) and by the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung.

References

- 1. Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, Von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol (2016) 131:803–20. 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weller M, van den Bent M, Tonn JC, Stupp R, Preusser M, Cohen-Jonathan-Moyal E, et al. European Association for Neuro-Oncology (EANO) Guideline on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Adult Astrocytic and Oligodendroglial Gliomas. Lancet Oncol (2017) 18:e315–29. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30194-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nonoguchi N, Ohta T, Oh J-E, Kim Y-H, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H. TERT Promoter Mutations in Primary and Secondary Glioblastomas. Acta Neuropathol (2013) 126:931–7. 10.1007/s00401-013-1163-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Simon M, Hosen I, Gousias K, Rachakonda S, Heidenreich B, Gessi M, et al. TERT Promoter Mutations: a Novel Independent Prognostic Factor in Primary Glioblastomas. Neuro-oncology (2014) 17:45–52. 10.1093/neuonc/nou158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eckel-Passow JE, Lachance DH, Molinaro AM, Walsh KM, Decker PA, Sicotte H, et al. Glioma Groups Based on 1p/19q, IDH, and TERT Promoter Mutations in Tumors. New Engl J Med (2015) 372:2499–508. 10.1056/NEJMoa1407279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Labussière M, Boisselier B, Mokhtari K, Di Stefano A-L, Rahimian A, Rossetto M, et al. Combined Analysis of TERT, EGFR, and IDH Status Defines Distinct Prognostic Glioblastoma Classes. Neurology (2014) 83:1200–6. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Albert NL, Weller M, Suchorska B, Galldiks N, Soffietti R, Kim MM, et al. Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology Working Group and European Association for Neuro-Oncology Recommendations for the Clinical use of PET Imaging in Gliomas. Neuro-oncology 2016:now058. 10.1093/neuonc/now058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Galldiks N, Langen K-J, Albert NL, Chamberlain M, Soffietti R, Kim MM, et al. PET Imaging in Patients With Brain Metastasis—Report of the RANO/PET Group. Neuro-oncology (2019). 10.1093/neuonc/noz003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Law I, Albert NL, Arbizu J, Boellaard R, Drzezga A, Galldiks N, et al. Joint EANM/EANO/RANO Practice Guidelines/SNMMI Procedure Standards For Imaging Of Gliomas Using PET With Radiolabelled Amino Acids and [18 F] FDG: Version 1.0. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging (2019) 46:540–57. 10.1007/s00259-018-4207-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Niyazi M, Geisler J, Siefert A, Schwarz SB, Ganswindt U, Garny S, et al. FET-PET for Malignant Glioma Treatment Planning. Radiother Oncol (2011) 99:44–8. 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Piroth MD, Pinkawa M, Holy R, Stoffels G, Demirel C, Attieh C, et al. Integrated-Boost IMRT or 3-D-CRT Using FET-PET Based Auto-Contoured Target Volume Delineation for Glioblastoma Multiforme–a Dosimetric Comparison. Radiat Oncol (2009) 4:57. 10.1186/1748-717X-4-57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fleischmann DF, Unterrainer M, Schön R, Corradini S, Maihöfer C, Bartenstein P, et al. Margin Reduction in Radiotherapy for Glioblastoma Through 18F-Fluoroethyltyrosine PET?–A Recurrence Pattern Analysis. Radiother Oncol (2020) 145:49–55. 10.1016/j.radonc.2019.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Unterrainer M, Eze C, Ilhan H, Marschner S, Roengvoraphoj O, Schmidt-Hegemann N, et al. Recent Advances of PET Imaging in Clinical Radiation Oncology. Radiat Oncol (2020) 15:1–15. 10.1186/s13014-020-01519-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bauer EK, Stoffels G, Blau T, Reifenberger G, Felsberg J, Werner JM, et al. Prediction of Survival in Patients With IDH-Wildtype Astrocytic Gliomas Using Dynamic O-(2-[18F]-Fluoroethyl)-l-Tyrosine PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging (2020) 47:1486–95. 10.1007/s00259-020-04695-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ceccon G, Lazaridis L, Stoffels G, Rapp M, Weber M, Blau T, et al. Use of FET PET in Glioblastoma Patients Undergoing Neurooncological Treatment Including Tumour-Treating Fields: Initial Experience. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging (2018) 45:1626–35. 10.1007/s00259-018-3992-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Galldiks N, Dunkl V, Ceccon G, Tscherpel C, Stoffels G, Law I, et al. Early Treatment Response Evaluation Using FET PET Compared to MRI in Glioblastoma Patients at First Progression Treated With Bevacizumab Plus Lomustine. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging (2018) 45:2377–86. 10.1007/s00259-018-4082-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Galldiks N, Unterrainer M, Judov N, Stoffels G, Rapp M, Lohmann P, et al. Photopenic Defects on O-(2-[18F]-fluoroethyl)-L-Tyrosine PET: Clinical Relevance in Glioma Patients. Neuro-oncology (2019) 21:1331–8. 10.1093/neuonc/noz083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Romagna A, Unterrainer M, Schmid-Tannwald C, Brendel M, Tonn J-C, Nachbichler SB, et al. Suspected Recurrence of Brain Metastases After Focused High Dose Radiotherapy: can [18 F] FET-PET Overcome Diagnostic Uncertainties? Radiat Oncol (2016) 11:139. 10.1186/s13014-016-0713-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Unterrainer M, Schweisthal F, Suchorska B, Wenter V, Schmid-Tannwald C, Fendler WP, et al. Serial 18F-FET PET Imaging of Primarily 18F-FET–Negative Glioma: Does it Make Sense? J Nucl Med (2016) 57:1177–82. 10.2967/jnumed.115.171033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Verger A, Stoffels G, Bauer EK, Lohmann P, Blau T, Fink GR, et al. Static and Dynamic 18F–FET PET for the Characterization of Gliomas Defined by IDH and 1p/19q Status. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging (2018) 45:443–51. 10.1007/s00259-017-3846-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vettermann F, Suchorska B, Unterrainer M, Nelwan D, Forbrig R, Ruf V, et al. Non-Invasive Prediction of IDH-Wildtype Genotype in Gliomas Using Dynamic 18 F-FET PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging (2019) 46:2581–9. 10.1007/s00259-019-04477-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, et al. The 2007 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. Acta Neuropathol (2007) 114:97–109. 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thon N, Eigenbrod S, Kreth S, Lutz J, Tonn JC, Kretzschmar H, et al. IDH1 Mutations in Grade II Astrocytomas are Associated With Unfavorable Progression-Free Survival and Prolonged Postrecurrence Survival. Cancer (2012) 118:452–60. 10.1002/cncr.26298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thon N, Eigenbrod S, Grasbon-Frodl EM, Ruiter M, Mehrkens JH, Kreth S, et al. Novel Molecular Stereotactic Biopsy Procedures Reveal Intratumoral Homogeneity of Loss of Heterozygosity of 1p/19q and TP53 Mutations in World Health Organization Grade II Gliomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol (2009) 68:1219–28. 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181bee1f1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Biczok A, Kraus T, Suchorska B, Terpolilli NA, Thorsteinsdottir J, Giese A, et al. TERT Promoter Mutation is Associated With Worse Prognosis in WHO Grade II and III Meningiomas. J Neuro-oncol (2018) 139:671–8. 10.1007/s11060-018-2912-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Suchorska B, Giese A, Biczok A, Unterrainer M, Weller M, Drexler M, et al. Identification of Time-to-Peak on Dynamic 18F-FET-PET as a Prognostic Marker Specifically in IDH1/2 Mutant Diffuse Astrocytoma. Neuro-Oncology (2017). 10.1093/neuonc/nox153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jansen NL, Suchorska B, Wenter V, Eigenbrod S, Schmid-Tannwald C, Zwergal A, et al. Dynamic 18F-FET PET in Newly Diagnosed Astrocytic Low-Grade Glioma Identifies High-Risk Patients. J Nucl Med (2014) 55:198–203. 10.2967/jnumed.113.122333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Unterrainer M, Vettermann F, Brendel M, Holzgreve A, Lifschitz M, Zähringer M, et al. Towards Standardization of 18 F-FET PET Imaging: do we Need a Consistent Method of Background Activity Assessment? EJNMMI Res (2017) 7:48. 10.1186/s13550-017-0295-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pauleit D, Floeth F, Hamacher K, Riemenschneider MJ, Reifenberger G, Muller HW, et al. O-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-L-Tyrosine PET Combined with MRI Improves the Diagnostic Assessment of Cerebral Gliomas. Brain (2005) 128:678–87. 10.1093/brain/awh399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jansen NL, Suchorska B, Wenter V, Schmid-Tannwald C, Todica A, Eigenbrod S, et al. Prognostic Significance of Dynamic 18F-FET PET in Newly Diagnosed Astrocytic High-Grade Glioma. J Nucl Med (2015) 56:9–15. 10.2967/jnumed.114.144675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jansen NL, Graute V, Armbruster L, Suchorska B, Lutz J, Eigenbrod S, et al. MRI-Suspected Low-Grade Glioma: is There a Need to Perform Dynamic FET PET? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging (2012) 39:1021–9. 10.1007/s00259-012-2109-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Labussiere M, Di Stefano A, Gleize V, Boisselier B, Giry M, Mangesius S, et al. TERT Promoter Mutations in Gliomas, Genetic Associations and Clinico-Pathological Correlations. Br J Cancer (2014) 111:2024–32. 10.1038/bjc.2014.538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Patel B, Taiwo R, Kim AH, Dunn GP. TERT, a Promoter of CNS Malignancies. Neuro-Oncol Adv (2020) 2:vdaa025. 10.1093/noajnl/vdaa025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lee Y, Koh J, Kim S-I, Won JK, Park C-K, Choi SH, et al. The Frequency and Prognostic Effect of TERT Promoter Mutation in Diffuse Gliomas. Acta Neuropathol Commun (2017) 5:62. 10.1186/s40478-017-0465-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Horn S, Figl A, Rachakonda PS, Fischer C, Sucker A, Gast A, et al. TERT Promoter Mutations in Familial and Sporadic Melanoma. Science (2013) 339:959–61. 10.1126/science.1230062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Huang FW, Hodis E, Xu MJ, Kryukov GV, Chin L, Garraway LA. Highly Recurrent TERT Promoter Mutations in Human Melanoma. Science (2013) 339:957–9. 10.1126/science.1229259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vinagre J, Almeida A, Pópulo H, Batista R, Lyra J, Pinto V, et al. Frequency of TERT Promoter Mutations in Human Cancers. Nat Commun (2013) 4:1–6. 10.1038/ncomms3185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Boado RJ, Li JY, Nagaya M, Zhang C, Pardridge WM. Selective Expression of the Large Neutral Amino Acid Transporter at the Blood–Brain Barrier. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1999) 96:12079–84. 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Habermeier A, Graf J, Sandhöfer BF, Boissel JP, Roesch F, Closs E. System l Amino Acid Transporter LAT1 Accumulates O-(2-fluoroethyl)-l-Tyrosine (FET). Amino Acids (2015) 47:335–44. 10.1007/s00726-014-1863-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wesseling P, van den Bent M, Perry A. Oligodendroglioma: Pathology, Molecular Mechanisms and Markers. Acta Neuropathol (2015) 129:809–27. 10.1007/s00401-015-1424-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Arita H, Kinoshita M, Kawaguchi A, Takahashi M, Narita Y, Terakawa Y, et al. Lesion Location Implemented Magnetic Resonance Imaging Radiomics for Predicting IDH and TERT Promoter Mutations in grade II/III Gliomas. Sci Rep (2018) 8:1–10. 10.1038/s41598-018-30273-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ivanidze J, Lum M, Pisapia D, Magge R, Ramakrishna R, Kovanlikaya I, et al. MRI Features Associated with TERT Promoter Mutation Status in Glioblastoma. J Neuroimaging (2019) 29:357–63. 10.1111/jon.12596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gutsche R, Scheins J, Kocher M, Bousabarah K, Fink GR, Shah NJ, et al. Evaluation of FET PET Radiomics Feature Repeatability in Glioma Patients. Cancers (2021) 13:647. 10.3390/cancers13040647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kebir S, Schmidt T, Weber M, Lazaridis L, Galldiks N, Langen K-J, et al. A Preliminary Study on Machine Learning-Based Evaluation of Static and Dynamic FET-PET for the Detection of Pseudoprogression in Patients with IDH-Wildtype Glioblastoma. Cancers (2020) 12:3080. 10.3390/cancers12113080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li XT, Huang RY. Standardization of Imaging Methods for Machine Learning in Neuro-Oncology. Neuro-oncol Adv (2020) 2:iv49–55. 10.1093/noajnl/vdaa054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lohmann P, Galldiks N, Kocher M, Heinzel A, Filss CP, Stegmayr C, et al. Radiomics in Neuro-Oncology: Basics, Workflow, and Applications. Methods (2021) 188:112–21. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2020.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lohmann P, Kocher M, Ruge MI, Visser-Vandewalle V, Shah NJ, Fink GR, et al. PET/MRI Radiomics in Patients With Brain Metastases. Front Neurol (2020) 11. 10.3389/fneur.2020.00001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lohmann P, Meißner A-K, Kocher M, Bauer EK, Werner J-M, Fink GR, et al. Feature-Based PET/MRI Radiomics in Patients With Brain Tumors. Neuro-Oncol Adv (2021) 2:iv15–21. 10.1093/noajnl/vdaa118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wiestler B, Menze B. Deep Learning for Medical Image Analysis: a Brief Introduction. Neuro-Oncol Adv (2020) 2:iv35–41. 10.1093/noajnl/vdaa092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lohmann P, Elahmadawy MA, Gutsche R, Werner J-M, Bauer EK, Ceccon G, et al. FET PET Radiomics for Differentiating Pseudoprogression from Early Tumor Progression in Glioma Patients Post-Chemoradiation. Cancers (2020) 12:3835. 10.3390/cancers12123835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lohmann P, Kocher M, Ceccon G, Bauer EK, Stoffels G, Viswanathan S, et al. Combined FET PET/MRI Radiomics Differentiates Radiation Injury From Recurrent Brain Metastasis. NeuroImage: Clin (2018) 20:537–42. 10.1016/j.nicl.2018.08.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lohmann P, Lerche C, Bauer EK, Steger J, Stoffels G, Blau T, et al. Predicting IDH Genotype in Gliomas Using FET PET Radiomics. Sci Rep (2018) 8:13328. 10.1038/s41598-018-31806-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bumes E, Wirtz F-P, Fellner C, Grosse J, Hellwig D, Oefner PJ, et al. Non-Invasive Prediction of IDH Mutation in Patients with Glioma WHO II/III/IV Based on F-18-FET PET-Guided In Vivo 1H-Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy and Machine Learning. Cancers (2020) 12:3406. 10.3390/cancers12113406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cimini A, Chiaravalloti A, Ricci M, Villani V, Vanni G, Schillaci O. MGMT Promoter Methylation and IDH1 Mutations Do Not Affect [18F]FDOPA Uptake in Primary Brain Tumors. Int J Mol Sci (2020) 21:7598. 10.3390/ijms21207598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Li L, Mu W, Wang Y, Liu Z, Liu Z, Wang Y, et al. A Non-Invasive Radiomic Method Using 18F-FDG PET Predicts Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Genotype and Prognosis in Patients With Glioma. Front Oncol (2019) 9. 10.3389/fonc.2019.01183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Matsui Y, Maruyama T, Nitta M, Saito T, Tsuzuki S, Tamura M, et al. Prediction of Lower-Grade Glioma Molecular Subtypes Using Deep Learning. J Neuro-Oncol (2020) 146:321–7. 10.1007/s11060-019-03376-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhou W, Zhou Z, Wen J, Xie F, Zhu Y, Zhang Z, et al. A Nomogram Modeling 11C-MET PET/CT and Clinical Features in Glioma Helps Predict IDH Mutation. Front Oncol (2020) 10. 10.3389/fonc.2020.01200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon reasonable request.