Abstract

Background

Resilience can be defined as the maintenance or quick recovery of mental health during or after periods of stressor exposure, which may result from a potentially traumatising event, challenging life circumstances, a critical life transition phase, or physical illness. Healthcare professionals, such as nurses, physicians, psychologists and social workers, are exposed to various work‐related stressors (e.g. patient care, time pressure, administration) and are at increased risk of developing mental disorders. This population may benefit from resilience‐promoting training programmes.

Objectives

To assess the effects of interventions to foster resilience in healthcare professionals, that is, healthcare staff delivering direct medical care (e.g. nurses, physicians, hospital personnel) and allied healthcare staff (e.g. social workers, psychologists).

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, 11 other databases and three trial registries from 1990 to June 2019. We checked reference lists and contacted researchers in the field. We updated this search in four key databases in June 2020, but we have not yet incorporated these results.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in adults aged 18 years and older who are employed as healthcare professionals, comparing any form of psychological intervention to foster resilience, hardiness or post‐traumatic growth versus no intervention, wait‐list, usual care, active or attention control. Primary outcomes were resilience, anxiety, depression, stress or stress perception and well‐being or quality of life. Secondary outcomes were resilience factors.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected studies, extracted data, assessed risks of bias, and rated the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach (at post‐test only).

Main results

We included 44 RCTs (high‐income countries: 36). Thirty‐nine studies solely focused on healthcare professionals (6892 participants), including both healthcare staff delivering direct medical care and allied healthcare staff. Four studies investigated mixed samples (1000 participants) with healthcare professionals and participants working outside of the healthcare sector, and one study evaluated training for emergency personnel in general population volunteers (82 participants). The included studies were mainly conducted in a hospital setting and included physicians, nurses and different hospital personnel (37/44 studies).

Participants mainly included women (68%) from young to middle adulthood (mean age range: 27 to 52.4 years). Most studies investigated group interventions (30 studies) of high training intensity (18 studies; > 12 hours/sessions), that were delivered face‐to‐face (29 studies). Of the included studies, 19 compared a resilience training based on combined theoretical foundation (e.g. mindfulness and cognitive‐behavioural therapy) versus unspecific comparators (e.g. wait‐list). The studies were funded by different sources (e.g. hospitals, universities), or a combination of different sources. Fifteen studies did not specify the source of their funding, and one study received no funding support.

Risk of bias was high or unclear for most studies in performance, detection, and attrition bias domains.

At post‐intervention, very‐low certainty evidence indicated that, compared to controls, healthcare professionals receiving resilience training may report higher levels of resilience (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.45, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.25 to 0.65; 12 studies, 690 participants), lower levels of depression (SMD −0.29, 95% CI −0.50 to −0.09; 14 studies, 788 participants), and lower levels of stress or stress perception (SMD −0.61, 95% CI −1.07 to −0.15; 17 studies, 997 participants). There was little or no evidence of any effect of resilience training on anxiety (SMD −0.06, 95% CI −0.35 to 0.23; 5 studies, 231 participants; very‐low certainty evidence) or well‐being or quality of life (SMD 0.14, 95% CI −0.01 to 0.30; 13 studies, 1494 participants; very‐low certainty evidence). Effect sizes were small except for resilience and stress reduction (moderate). Data on adverse effects were available for three studies, with none reporting any adverse effects occurring during the study (very‐low certainty evidence).

Authors' conclusions

For healthcare professionals, there is very‐low certainty evidence that, compared to control, resilience training may result in higher levels of resilience, lower levels of depression, stress or stress perception, and higher levels of certain resilience factors at post‐intervention.

The paucity of medium‐ or long‐term data, heterogeneous interventions and restricted geographical distribution limit the generalisability of our results. Conclusions should therefore be drawn cautiously. The findings suggest positive effects of resilience training for healthcare professionals, but the evidence is very uncertain. There is a clear need for high‐quality replications and improved study designs.

Plain language summary

Psychological interventions to foster resilience in healthcare professionals

Background The work of healthcare professionals (e.g. nurses, physicians, psychologists, social workers) can be very stressful. They often carry a lot of responsibility and are required to work under pressure. This can adversely affect their physical and mental health. Interventions to protect them against such stresses are known as resilience interventions. Previous systematic reviews suggest that resilience interventions can help workers cope with stress and protect them against adverse consequences for their physical and mental health.

Review question Do psychological interventions designed to foster resilience improve resilience, mental health and other factors associated with resilience in healthcare professionals?

Search dates The evidence is current to June 2019. The results of an updated search of four key databases in June 2020 have not yet been included in the review.

Study characteristics We found 44 randomised controlled trials (studies in which participants are assigned to either an intervention or a control group by a procedure similar to tossing a coin). The studies tested a range of resilience interventions in participants aged on average between 27 and 52.4 years.

Healthcare professionals were the focus of 39 studies, with a total of 6892 participants. Four studies included mixed samples (1000 participants) of healthcare professionals and non‐healthcare participants. One study of resilience training for emergency workers examined 82 volunteers.

Of the included studies, 19 compared a combined resilience intervention (e.g. mindfulness and cognitive‐behavioural therapy) versus unspecific comparators (e.g. a wait‐list control receiving the training after a waiting period). Most interventions (30/44) were performed in groups, with high training intensity of more than 12 hours or sessions (18/44), and were delivered face‐to‐face (i.e. with direct contact and face‐to‐face meetings between the intervention provider and the participants; 29/44).

The included studies were funded by different sources (e.g. hospitals, universities), or a combination of different sources. Fifteen studies did not specify the source of their funding, and one study received no funding support.

Certainty of the evidence A number of things reduce the certainty about whether or not resilience interventions are effective. These include limitations in the methods of the studies, different results across studies, the small number of participants in most studies, and the fact that the findings are limited to certain participants, interventions and comparators.

Key results For healthcare professionals, resilience training may improve resilience, and may reduce symptoms of depression and stress immediately after the end of treatment. Resilience interventions do not appear to reduce anxiety symptoms or improve well‐being. However, the evidence found in this review is limited and very uncertain. This means that, at present, we have very little confidence that resilience interventions make a difference to these outcomes. Further research is very likely to change the findings.

Very few studies reported on the longer‐term impact of resilience interventions. Studies used a variety of different outcome measures and intervention designs, making it difficult to draw general conclusions from the findings. Potential adverse events were only examined in three studies, showing no undesired effects. More research is needed of high methodological quality and with improved study designs.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Resilience interventions compared to control condition for healthcare professionals.

| Resilience interventions compared to control condition for healthcare professionals | ||||||

|

Patient or population: healthcare professionals including healthcare staff delivering direct medical care (e.g. nurses, physicians, hospital personnel) and allied healthcare staff (e.g. social workers, psychologists); aged 18 years and older, irrespective of health status Setting: Any healthcare sectors (e.g. psychiatric departments, intensive care unit, surgery, family medicine, internal medicine) Intervention: Any psychological resilience intervention focused on fostering resilience or the related concepts of hardiness or post‐traumatic growth by strengthening well‐evidenced resilience factors that are thought to be modifiable by training (see Appendix 3), irrespective of content, duration, setting or delivery mode Comparison: no intervention, wait‐list control, treatment as usual (TAU), active control, attention control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with resilience interventions | |||||

|

Resilience Measured by: investigators measured resilience using different instruments; higher scores mean higher resilience Timing of outcome assessment: post‐intervention |

See comment | The mean resilience score in the intervention groups was, on average, 0.45 standard deviations higher (0.25 higher to 0.65 higher) | ‐ | 690 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | SMD of 0.45 represents a moderate effect size (Cohen 1988b). |

|

Mental health and well‐being: anxiety Measured by: investigators measured anxiety using different instruments; lower scores mean lower anxiety Timing of outcome assessment: post‐intervention |

See comment | The mean anxiety score in the intervention groups was, on average, 0.06 standard deviations lower (0.35 lower to 0.23 higher) | ‐ | 231 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb | SMD of 0.06 represents a small effect size (Cohen 1988b). |

|

Mental health and well‐being: depression Measured by: investigators measured depression using different instruments; lower scores mean lower depression Timing of outcome assessment: post‐intervention |

See comment | The mean depression score in the intervention groups was, on average, 0.29 standard deviations lower (0.50 lower to 0.09 lower) | ‐ | 788 (14 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc | SMD of 0.29 represents a small effect size (Cohen 1988b). |

|

Mental health and well‐being: stress or stress perception

Measured by: investigators measured stress or stress perception using different instruments; lower scores mean lower stress or stress perception Timing of outcome assessment: post‐intervention |

See comment | The mean stress or stress perception score in the intervention groups was, on average, 0.61 standard deviations lower (1.07 lower to 0.15 lower) | ‐ | 997 (17 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowd | SMD of 0.61 represents a moderate effect size (Cohen 1988b). |

|

Mental health and well‐being: well‐being or quality of life Measured by: investigators measured well‐being or quality of life using different instruments; higher scores mean higher well‐being or quality of life Timing of outcome assessment: post‐intervention |

See comment | The mean well‐being or quality of life score in the intervention groups was, on average, 0.14 standard deviations higher (0.01 lower to 0.30 higher) | ‐ | 1494 (13 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowe | SMD of 0.14 represents a small effect size (Cohen 1988b). |

| Adverse events | There were no adverse events reported in association with study participation in three studies. | ‐ | 784 (3 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowf | ‐ | |

|

*The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; SD: standard deviation;SMD: standardised mean difference. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded two levels due to study limitations (unclear risk of selection and detection bias, high and unclear risk of attrition bias, high risk of performance bias), one level due to unexplained inconsistency (I2 = 41%), and one level due to indirectness (studies limited to certain participants (young and middle‐aged adults), interventions (e.g. group setting, face‐to‐face delivery, moderate and high intensity, mindfulness‐based training and combination) and comparators (no intervention, wait‐list)). bDowngraded two levels due to study limitations (unclear risk of selection and detection bias, unclear and high risk of performance bias, high risk of attrition bias), one level due to indirectness (studies limited to certain participants (middle‐aged adults)), and two levels due to imprecision (< 400 participants; 95% CI wide and inconsistent). cDowngraded two levels due to study limitations (unclear risk of selection and detection bias, unclear and high risk of performance bias, high risk of attrition bias), one level due to unexplained inconsistency (I2 = 42%), one level due to indirectness (studies limited to certain participants (middle‐aged adults), interventions (e.g. group setting, face‐to‐face delivery, moderate and high intensity, mindfulness‐based training and combination) and comparators (no intervention)), and one level due to imprecision (95% CI wide and inconsistent). dDowngraded two levels due to study limitations (unclear risk of selection and detection bias, high and unclear risk of attrition bias, high risk of performance bias), one level due to unexplained inconsistency (I2 = 90%), and one level due to indirectness (studies limited to certain participants (young and middle‐aged adults), interventions (e.g. group setting, face‐to‐face delivery, moderate and high intensity, mindfulness‐based training and combination) and comparators (no intervention, wait‐list)). eDowngraded two levels due to study limitations (unclear risk of selection and detection bias, unclear and high risk of attrition bias, high risk of performance bias), one level due to unexplained inconsistency (I2 = 31%), one level due to indirectness (studies limited to certain participants (young and middle‐aged adults), interventions (e.g. group setting, face‐to‐face delivery, moderate and high intensity, mindfulness‐based trainings and combination) and comparators (no intervention, wait‐list)), and one level due to imprecision (95% CI wide and inconsistent). fDowngraded two levels due to study limitations (unclear risk of selection and detection bias, high and unclear risk of attrition and other bias (no or unclear systematic and validated assessment of adverse events), high risk of performance bias), and one level due to indirectness (studies limited to certain interventions (e.g. combined setting, face‐to‐face delivery, high intensity, mindfulness‐based training)).

Background

For a description of abbreviations used in this review, please see Appendix 1.

Description of the condition

Since the introduction of Antonovsky’s salutogenesis as a basis for health promotion (Antonovsky 1979), and the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (WHO 1986), the concept of resilience has stimulated extensive research. Resilience describes the phenomenon in which an individual does not, or only temporarily experiences mental health problems despite being subjected to psychological or physical stressors of short (acute) or long (chronic) duration (Kalisch 2015; Kalisch 2017). By definition, resilience presupposes the exposure to substantial risk or adversity (Earvolino‐Ramirez 2007; Jackson 2007; Luthar 2000a; Masten 2001).

Stressor exposure in healthcare professionals and its consequences

Healthcare professionals are exposed to a large number of environmental and psychosocial stressors (Aiken 2001; Hannigan 2004; Jennings 2008; Kumar 2016; Lambert 2004). Substantial patient‐related stressors include, for example, physical or verbal aggression from patients or relatives or both, (daily) exposure to diseases, suffering, and death or even patient suicides (Jackson 2007; McAllister 2009; McCann 2013). Work‐related stressors may include time pressure, the responsibility of medical decision‐making, as well as social expectations of health professionals (Lateef 2011; McAllister 2009; McCann 2013). Healthcare staff moreover can be exposed to many organisational adversities such as interdisciplinary teamwork, inflexible hierarchies, staff downsizing, increasing administrative effort and technological changes such as new diagnostic tools (Jackson 2007; McAllister 2009; McCann 2013; Zander 2013). Especially in the nursing professions, high job demands are linked to low financial rewards.

Chronic stressor exposure has a potential impact on mental health. Some of the above‐mentioned factors were shown to be associated with employees' mental health problems in general (Gray 2019; Harvey 2017; Marchand 2015). For the healthcare sector in particular, for example, high workload (e.g. long working hours; Adriaenssens 2015; Anderson 2017; Van Ham 2006; Shanafelt 2009; Shanafelt 2016), demanding work situations (e.g. in emergency ward; Adriaenssens 2011; Adriaenssens 2015), workplace violence (Pekurinen 2017; Shi 2017), lack of recognition (Adriaenssens 2015; Van Ham 2006) and administrative burdens (Anderson 2017; Van Ham 2006) have been shown to be associated with burnout symptoms and mental health problems. Physicians and other employees in the healthcare industry have been shown to report debilitating sleep disorders (Kim 2018b; Schlafer 2014). Healthcare professionals are at increased risk of developing burnout symptoms (e.g. high emotional exhaustion; Aiken 2001; Hannigan 2004) and stress‐related mental disorders (Gracino 2016; Harvey 2009; Robertson 2010; Weinberg 2000; Wieclaw 2006), such as depression (Frank 1999; Gong 2014; Tomioka 2011) and post‐traumatic stress disorder (Jonsson 2003; Mealer 2009; Ong 2016). They also have higher rates of substance misuse (Horsfall 2014) and have been shown to report increased perceived stress (Leonelli 2017). Due to emotional stressors, such as working with traumatised patients, healthcare workers also commonly report compassion fatigue and secondary traumatic stress (Adams 2006). Furthermore, compared to other disciplines, higher suicide rates for healthcare staff (e.g. physicians) have been demonstrated (Horsfall 2014; Meltzer 2008). In the face of chronic stressors and the resulting impact on physical and mental health, healthcare workers have higher numbers of days absent due to illness (Moberly 2018; Michie 2003) and report reduced job satisfaction (Kuburović 2016; Lu 2016), which is often associated with job termination and understaffing, especially in the nursing sector. For example, based on a cross‐sectional observational study in 10 European countries, Heinen 2013 found that 5% to 17% of nurses from participating medical and surgical hospital wards intended to leave the profession. For new nursing‐school graduates, high first‐year turnover rates (i.e. the percentage of employees leaving in the first year after training) have been reported (35% to 61%; Pine 2007).

Overall, based on these findings, the concept of resilience has become increasingly important in healthcare professionals in recent years (Hart 2014; Jackson 2007; McAllister 2009; McCann 2013).

Definition of resilience

Three different approaches have been discussed for a definition of resilience (Hu 2015; Kalisch 2015). Trait resilience is defined as personal resources or static, positive personality characteristics that enhance individual adaptation (Block 1996; Nowack 1989; Wagnild 1993). This approach has largely been superceded by a view of resilience as an outcome rather than a static personality trait (Kalisch 2015; Mancini 2009); that is, mental health despite significant stress or trauma. According to this outcome‐oriented definition, resilience is partially determined by several resilience factors (Kalisch 2015). To date, a large range of genetic, psychological, social and environmental factors have been discussed that often overlap and may interact (Bengel 2012; Bonanno 2013; Carver 2010; Connor 2006; Earvolino‐Ramirez 2007; Feder 2011; Forgeard 2012; Haglund 2007; Iacoviello 2014; Kuiper 2012; Mancini 2009; Michael 2003; Ozbay 2007; Rutten 2013; Sapienza 2011; Sarkar 2014; Southwick 2005; Southwick 2012; Stewart 2011; Wu 2013; Zauszniewski 2010). Psychosocial resilience factors that are well‐evidenced according to the current state of knowledge and are thought to be modifiable include: meaning or purpose in life, a sense of coherence, positive emotions, hardiness, self‐esteem, active coping, self‐efficacy, optimism, social support, cognitive flexibility (including positive reappraisal and acceptance), and religiosity or spirituality or religious coping (see Appendix 2: level 1). Most recently, resilience has been conceptualised as a multidimensional and dynamic process (Johnston 2015; Kalisch 2015; Kent 2014; Mancini 2009; Norris 2009; Rutten 2013; Sapienza 2011; Southwick 2012). This resilient process is characterised either by a trajectory of undisturbed mental health during or after adversities, or by temporary dysfunctions followed by successful recovery (Kalisch 2015). In general, resilience is viewed as the outcome of an interaction between individuals and their environment (Cicchetti 2012; Rutten 2013), which may be influenced through personal (e.g. optimism) as well as environmental (e.g. social support) resources (Haglund 2007; Iacoviello 2014; Kalisch 2015; Southwick 2005; Wu 2013). As such, resilience is modifiable and can be improved by interventions (Bengel 2012; Connor 2006; Southwick 2011).

Interventions to foster resilience

Interventions to foster resilience have been developed for and conducted in a variety of clinical and non‐clinical populations using various formats, such as multimedia programmes or face‐to‐face settings, and have been delivered in a group or individual context (see Bengel 2012 and Southwick 2011 for an overview). To date, several training programmes that focus specifically on fostering resilience in healthcare professionals have also been tested (e.g. Mealer 2014; Sood 2011). However, the empirical evidence about the efficacy of these interventions is still unclear and requires further research.

Description of the intervention

There is little consensus so far about when to consider a programme as ‘resilience training’, or what components are needed for effective programmes (Leppin 2014). The diversity across resilience‐training programmes in their theoretical assumptions, the operationalisation of the construct, and the inclusion of core components reflect the current state of knowledge (Joyce 2018; Leppin 2014; Macedo 2014; Robertson 2015; Vanhove 2016), with leading guidelines still under discussion (compare Kalisch 2015; Robertson 2015).

Most training programmes, whether individual or group‐based, are implemented face‐to‐face. Alternative formats include online interventions or combinations of different formats. Resilience‐training programmes often use methods such as discussions, role plays, practical exercises and homework to reinforce training content. Moreover, they mostly contain a psycho‐educative element to provide information on the concept of resilience or specific training elements (e.g. cognitive restructuring).

In general, resilience interventions are based on different psychotherapeutic approaches: cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT; Abbott 2009); acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT; Ryan 2014); mindfulness‐based therapy (Geschwind 2011); attention and interpretation therapy (AIT; Sood 2014); problem‐solving therapy (Bekki 2013); and stress inoculation (Farchi 2010). A number of training programmes focus on fostering single or multiple psychosocial resilience factors, without being assignable to a certain approach. Few interventions base their work on a defined resilience model (Schachman 2004; Steinhardt 2008).

How the intervention might work

Depending on the underlying resilience concept, resilience interventions target different resources and skills. The theoretical foundations of training programmes and the hypotheses on how they might maintain or regain mental health are as diverse as their content. Currently, no empirically‐validated theoretical framework exists that outlines the mode of action of resilience interventions (Bengel 2012; Leppin 2014).

As resilience as an outcome is determined by several potentially modifiable resilience factors (see Description of the condition), resilience interventions might work by strengthening these factors (see Appendix 3 for examples of possible training methods). However, depending on the underlying theoretical foundation, there are different theories of change on how certain factors and hence resilience might be affected.

From the 'cognitive‐behavioural perspective', stress‐related mental dysfunctions (e.g. depression) are considered to be the result of dysfunctional thinking (Beck 2011; Benjamin 2011). When confronted with adversity, people show maladaptive behavioural responses or experience negative mood states, or both, due to irrational cognitions (Beck 1976; Ellis 1975). This is in line with other stress and resilience theories, assuming that not the stressor itself but its cognitive appraisal may lead to stress reactions (e.g. Kalisch 2015; Lazarus 1987). Modifying cognitive processes into more adaptive patterns of thought will therefore probably produce more adaptive responses to stress (Beck 1964). By challenging an individual’s maladaptive thoughts and by teaching coping strategies, CBT‐based resilience interventions might be beneficial in promoting the resilience factors of cognitive flexibility and active coping.

As one form of CBT, 'stress inoculation therapy’ is based on the assumption that exposing individuals to milder forms of stress can strengthen coping strategies and the individual’s confidence in using his/her coping repertoire (Meichenbaum 2007). Resilience‐training programmes grounded in stress inoculation therapy might therefore foster resilience by enhancing factors such as self‐efficacy.

Problem‐solving therapy is closely related to CBT and is based on problem‐solving theory. According to the ’problem‐solving’ model of stress and adaptation, effective problem‐solving can attenuate the negative effects of stress and adversity on well‐being by moderating or mediating the effects of stressors on emotional distress (Nezu 2013). Resilience interventions based on problem‐solving that enhance an individual’s positive problem orientation and resourceful problem‐solving might foster the participants’ psychological adaptation to stress by increasing the resilience factor of active coping.

According to 'acceptance and commitment therapy' (ACT) (Hayes 2004; Hayes 2006), psychopathology is primarily the consequence of psychological inflexibility (Hayes 2006), which is also relevant when an individual is confronted with stressors. By teaching acceptance and mindfulness skills (e.g. being in contact with the present moment), and also commitment and behaviour‐change skills (e.g. values, committed action), several resilience factors might be fostered in ACT‐based resilience interventions (e.g. cognitive flexibility, purpose in life). In particular, the acceptance of a full range of emotions taught in ACT might result in a better adjustment to stressful conditions.

In 'mindfulness‐based therapy' (e.g. mindfulness‐based stress reduction (MBSR; Stahl 2010); attention and interpretation therapy (AIT; Sood 2010)), mindfulness is characterised by the non‐judgmental awareness of the present moment and its accompanying mental phenomena (e.g. body sensations, thoughts, emotions). Since practitioners learn to accept whatever occurs in the present moment, they are thought to adapt more efficiently to stressors (Grossman 2004; Shapiro 2005). As being more aware of the 'here and now' possibly enhances the sensitivity for positive aspects in life, mindfulness‐based resilience interventions might also help participants to gain a brighter outlook for the future (i.e. optimism) or to experience positive emotions more regularly. Teaching mindfulness might also increase participants’ cognitive flexibility by learning to accept negative situations and emotions.

Independent of the underlying theory, resilience training might work differently depending on the respective 'delivery format' and 'intervention setting' (Robertson 2015; Vanhove 2016). For example, interventions implemented face‐to‐face could work better than online formats in increasing resilience, due to the more direct contact between trainers and participants (Vanhove 2016), which might also increase compliance. Resilience training in an individual setting could be more efficient than group‐based interventions as trainers might be better able to attend to participants’ individual needs and provide feedback more easily (Vanhove 2016). On the other hand, group‐based interventions could enhance the participants’ social resources. No previous review has examined the role of training duration on effect sizes of resilience interventions. As participants have the opportunity to apply the taught skills in daily life, high‐intensity resilience interventions that include weekly sessions over several weeks (e.g. combined with homework assignments or daily practice) could be more efficient than low‐intensity training (e.g. single session). Joyce 2018, who examined the role of the theoretical foundation of resilience interventions for the first time, found positive effect sizes on resilience for CBT‐based, mindfulness‐based and mixed interventions (e.g. CBT and mindfulness) compared to control. However, differences in the effects of resilience training based on other theoretical foundations have not been considered so far.

Why it is important to do this review

To date, a large number of systematic reviews and meta‐analyses have investigated various forms of intervention to foster healthcare professionals' mental health (see Appendix 4). Although some of these reviews also identified interventions to foster resilience (e.g. Lamothe 2016; Ruotsalainen 2015), the primary review question did not specifically refer to identifying such programmes.

A considerable number of systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of interventions to foster resilience (see Appendix 4) have synthesised the efficacy of resilience‐training programmes in clinical and non‐clinical adult populations (Bauer 2018; Joyce 2018; Leppin 2014; Macedo 2014; Massey 2019; Milne 2016; Pallavicini 2016; Pesantes 2015; Petriwskyj 2016; Reyes 2018; Robertson 2015; Skeffington 2013; Townshend 2016; Vanhove 2016; Van Kessel 2014; Wainwright 2019) or at least searched for 'resilience' and related constructs (Deady 2017; Tams 2016). Thus far, there are only three relevant meta‐analyses (Joyce 2018; Leppin 2014; Vanhove 2016). Overall, previous reviews agree in their conclusion that resilience interventions can generally improve resilience, mental health and (job) performance. Nevertheless, there are some methodological and quality differences between the reviews, which complicate statements about the efficacy of resilience training or result in a variety of effect sizes (see Appendix 4). These include, for example, heterogeneous eligibility criteria and definitions of resilience training, rather simple and limited search strategies, the lack of a review protocol or PROSPERO registration for most reviews, and different guidelines for the conduct and reporting of the review.

With respect to healthcare professionals (see Appendix 4), 11 systematic reviews (Cleary 2018; Concilio 2019; Delgado 2017; Elliott 2012; Foster 2019; Fox 2018; Gillman 2015; Gilmartin 2017; Robertson 2016; Rogers 2016; Wright 2017) and one meta‐analysis (Lavin Venegas 2019) have synthesised evidence on the efficacy of resilience‐training programmes in this target group, with two other reviews also searching for 'resilience' (Hunter 2016; Pezaro 2017). The 14 publications either investigated healthcare staff in general, in primary or in dementia care (Cleary 2018); specific groups of healthcare workers (e.g. physicians, Fox 2018); or combinations of healthcare professionals and healthcare students (Gilmartin 2017). Overall, they found mixed results for the efficacy of resilience‐training programmes. On the one hand, they found some benefits to healthcare professionals; for example, in improving resilience or mental health outcomes (e.g. anxiety, perceived stress; Cleary 2018; Gilmartin 2017; Pezaro 2017; Rogers 2016; Wright 2017). On the other hand, as pointed out by many authors of previous publications (Fox 2018; Lavin Venegas 2019), the reviews' conclusions are also restricted by current limitations of resilience intervention research (e.g. heterogeneous definitions of resilience, low methodological rigour of studies). Comparable to reviews in other populations, the publications also suffer from methodological weaknesses that limit the robustness of their findings (see Appendix 4). Most importantly, the number of RCTs included in previous reviews is rather limited (0 to 9 RCTs among 5 to 33 included studies in the 14 reviews), and the search period covered by the reviews is up to June 2018 (Foster 2019), thus precluding any conclusions about the efficacy of resilience interventions in healthcare professionals that have been developed since then.

In our review, which seeks to address the methodological weaknesses of previous reviews, we were particularly interested in psychological resilience interventions offered to this target group. The interventions had to be scientifically founded, that is, they had to address one or more of the resilience factors stated above that are known to be associated with resilience in adults according to the current state of research (compare Appendix 2: levels 1a to 1c). They also had to state the intention of promoting resilience or a related construct (hardiness, post‐traumatic growth). Lastly, the trained population had to fulfil the condition of potential stress or trauma exposure (the concept implicated for resilience); that is, being employed as a healthcare professional (see Description of the condition), in order to clearly distinguish genuine resilience interventions from other interventions focused on fostering associated constructs such as mental health (Windle 2011a).

Resilience as a concept of prevention is highly current, and there is increasing interest worldwide in promoting mental health and preventing disease (WHO 1986; WHO 2004). Due to chronic stressor exposure in health professions, and the potential negative consequences for the employees’ health, patient care and economic consequences (see Description of the condition), healthcare workers are viewed as one of the most important target groups for resilience interventions (McCann 2013). This review therefore aims to provide further and more detailed evidence about which interventions are most likely to foster resilience and prevent stress‐related mental health problems in healthcare professionals. The evidence base for this review might contribute to improving existing interventions and to facilitating the future development of training programmes. In this way, researchers, practitioners and policy‐makers could benefit from our work.

Objectives

To assess the effects of interventions to foster resilience in healthcare professionals, that is, healthcare staff delivering direct medical care (e.g. nurses, physicians, hospital personnel) and allied healthcare staff (e.g. social workers, psychologists) (see Differences between protocol and review).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cluster‐RCTs.

Types of participants

Adults aged 18 years and older, who are employed as healthcare professionals, i.e. healthcare staff delivering direct medical care such as physicians, nurses, hospital personnel, and allied healthcare staff working in health professions, as distinct from medical care (e.g. psychologists, social workers, counsellors, physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, medical assistants, medical technicians) (see Differences between protocol and review).

Participants were included irrespective of health status.

At the time of the intervention, individuals had to be exposed to potential risk or stressors, which was ensured by focusing on healthcare staff in this review (see Description of the condition; Differences between protocol and review).

We included studies involving mixed samples (e.g. ambulance personnel and firefighters) in the review. These studies were also considered in meta‐analysis (see Data synthesis) if data for healthcare professionals were reported separately or could be obtained by contacting the study authors.

Types of interventions

Any psychological resilience intervention, irrespective of content, duration, setting or delivery mode.

For the purpose of this review, we define psychological resilience interventions as follows: interventions focused on fostering resilience or the related concepts of hardiness or post‐traumatic growth by strengthening well‐evidenced resilience factors that are thought to be modifiable by training (see above and Appendix 2; level 1). In order to use highly objective inclusion criteria, we considered only interventions that explicitly defined the objective of fostering resilience, hardiness, or post‐traumatic growth by using one or more of these terms in the publication (see Differences between protocol and review).

Studies of pharmacological (e.g. treatment with antidepressants) and physical (e.g. exercise) interventions, as well as relaxation techniques (e.g. progressive muscle relaxation), were only considered if these interventions were part of psychological resilience training. We did not include studies that merely examined the efficacy of disorder‐specific psychotherapy (e.g. CBT for depression).

The comparators we considered in this review include no intervention, wait‐list control, treatment as usual (TAU), active control, and attention control. We use the term ‘attention control’ for alternative treatments that mimicked the amount of time and attention received (e.g. by trainer) in the treatment group. We also considered active controls to involve an alternative treatment (no TAU; for example, treatment developed specifically for the study), but that did not control for the amount of time and attention in the intervention group and was not attention control in a narrow sense.

Types of outcome measures

Due to the different ways in which resilience has been operationalised in previous research, resilience as an intervention outcome could not always be guaranteed in studies. We therefore also defined assessments of psychological adaptation (e.g. mental health) as primary outcomes.

Secondary outcomes included a range of psychological factors associated with resilience, according to the current state of knowledge, and were selected based on conceptual clarity and measurability (level 1a and 1b; see Appendix 2).

Measures for the assessment of psychological resilience and psychological adaptation, as well as resilience factors, are specified on the basis of previous reviews of resilience interventions (Leppin 2014; Macedo 2014; Robertson 2015; Vanhove 2016) and reviews of resilience measurements (Pangallo 2015; Windle 2011b); see Helmreich 2017 and Appendix 5, Appendix 6, Appendix 7 in this review, respectively.

We considered self‐rated and observer‐ or clinician‐rated measures, as well as study outcomes, at all time points. The absence of the primary or secondary outcomes described above was not an exclusion criterion for this review.

Primary outcomes

Resilience*, measured by improvements in specific resilience scales (Bengel 2012; Earvolino‐Ramirez 2007; Pangallo 2015; Windle 2011b), such as the Resilience Scale for Adults (Friborg 2003).

-

Mental health and well‐being, subsumed into the categories below, and measured by improvements in the respective assessment scales, such as the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS‐21; Lovibond 1995). See Appendix 6 for further examples.

Anxiety*

Depression*

Stress or stress perception*

Well‐being or quality of life* (e.g. well‐being, life satisfaction, (health‐related) quality of life, vitality, vigour)

Adverse events*

Secondary outcomes

Resilience factors (Bengel 2012; Haglund 2007; Iacoviello 2014; Southwick 2005; Southwick 2012; Wu 2013), whenever they were available as outcomes, assessed by an increase in the respective instruments (e.g. Life Orientation Test ‐ Revised (LOT‐R); Scheier 1994). For further examples see Appendix 7.

Social support

Optimism

Self‐efficacy

Active coping

Self‐esteem

Hardiness (although hardiness is often used as a synonym for resilience in the literature, we conceptualised it as a resilience factor in this review. See Appendix 2)

Positive emotions

We extracted and report data on secondary outcomes whenever they were assessed. If possible, we calculated and reported effect sizes.

Where data were available, we used outcomes marked by an asterisk (*) to generate the ‘Summary of findings’ table. In case of insufficient information, we provide a narrative description of the evidence.

Search methods for identification of studies

We ran the first searches for this review in October 2016, based on the MEDLINE search strategy in the protocol (Helmreich 2017) before changing the inclusion criteria of the review to focus on healthcare professionals (see Differences between protocol and review). For the top‐up searches in June 2019, we added a new section to the original search strategy, using search terms to limit the search to healthcare sector workers and students.

Electronic searches

We searched the electronic sources listed below.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 6) in the Cochrane Library, which includes the Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Specialised Register (searched 26 June 2019).

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 21 June 2019).

Embase Ovid (1974 to 2019 Week 25).

PsycINFO Ovid (1806 to June Week 3 2019).

CINAHL EBSCOhost (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1981 to 24 June 2019).

PSYNDEX EBSCOhost (1977 to 24 June 2019).

Web of Science Core Collection Clarivate (Science Citation Index; Social Science Citation Index; Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Social Science & Humanities; Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Science; 1970 to 26 June 2019).

International Bibliography of the Social Sciences ProQuest (IBSS; 1951 to 25 June 2019).

Applied Social Sciences Index & Abstracts ProQuest (ASSIA; 1987 to 24 June 2019).

ProQuest Dissertations & Theses (PQDT; 1743 to 24 June 2019).

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR; 2019, Issue 6) in the Cochrane Library (searched 26 June 2019).

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE; 2015, Issue 4) in the Cochrane Library (final issue; searched 27 October 2016)

Epistemonikos (epistemonikos.org; all available years).

ERIC EBSCOhost (Education Resources Information Center Institute of Education Sciences; 1966 to 26 June 2019).

Current Controlled Trials (controlled-trials.com; 1 January 1990 to 24 June 2019).

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov; 1 January 1990 to 24 June 2019).

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP; who.int/trialsearch; 1 January 1990 to 24 June 2019).

The search strategies for each database are reported in Appendix 8 (up to 2016) and for the revised inclusion criteria Appendix 9 (2016 onwards). We used the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy to identify RCTs in Medline (Lefebvre 2019). We adapted the search terms and syntax for other databases. The searches were not restricted by language, publication status or publication format. Our search was limited to the period January 1990 onwards. We applied this restriction to account for the fact that the resilience concept and its operationalisation have developed significantly over the past decades (Fletcher 2013; Hu 2015; Kalisch 2015; Pangallo 2015). Because of the lack of homogeneity for the period 1990 to 2014 (Robertson 2015), it is likely that using a broader time frame would have made it even more difficult to detect resilience‐training studies with similar resilience concepts and assessments. Moreover, it appeared plausible to concentrate on the period 1990 to the present, since the idea of resilience as an outcome and as a modifiable process has only emerged in recent years, and paved the way for the development of resilience‐promoting interventions (Bengel 2009; Southwick 2011). The idea of fostering resilience by specific training was therefore relatively new (Leppin 2014). This can also be seen in the review by Macedo 2014, who searched for studies on resilience interventions every year until 2013 but only found RCTs published after 1990.

As resilience‐training programmes should be adapted to scientific findings on a regular basis, and with the current research focusing on the detection of general resilience mechanisms (Kalisch 2015; Luthar 2000a), the last five years seemed especially important in synthesising the evidence on newly‐developed resilience training.

We performed a further scoping search of four key databases (CENTRAL, CINAHL EBSCOhost, PsycINFO Ovid, ClinicalTrials.gov) in June 2020 prior to the publication of this review. The results are awaiting classification and will be incorporated into the review at the next update.

Searching other resources

In addition to the electronic search, we inspected the reference lists of all included RCTs and relevant reviews, and contacted researchers in the field as well as the authors of selected studies, to check if there are any unpublished or ongoing studies. If data were missing or unclear, we contacted the study author.

Data collection and analysis

In successive sections, we report only the methods we used in this review. Preplanned but unused methods are reported in Table 2.

1. Unused methods table.

| Section | Proposed methods | Reason for non‐use |

| Measures of treatment effect | Dichotomous data We planned to analyse dichotomous outcomes by calculating the risk ratio (RR) of a successful outcome (i.e. improvement in relevant variables) for each trial. We would have expressed uncertainty in each result using 95% confidence intervals (CIs). | We only identified two studies with dichotomous data for depression (West 2014; West 2015). Both studies also provided continuous primary outcome data relevant for this review (burnout) and could be combined in meta‐analysis with other studies reporting continuous outcomes. |

| Unit of analysis issues | Cluster‐randomised trials In cluster‐randomised trials, if the clustering had been ignored and the unit of analysis had been different from the unit of allocation (‘unit‐of‐analysis error’) (Whiting‐O'Keefe 1984), P values might have been artificially small and resulted in false‐positive conclusions (Higgins 2019b). Had we found such cases, we would have accounted for clustering in the data and followed the recommendations given in the literature (Higgins 2019b; White 2005). For those cluster‐randomised trials that did not report correct standard errors, we would have tried to recover correct standard errors by applying the usual formula for the variance inflation factor 1 + (M ‐ 1) ICC, where M is the average cluster size and ICC the intra‐cluster correlation coefficient (Higgins 2019b). Had it not been possible to extract ICC values from the study, we would have used the average ICC of all cluster‐randomised trials in our review that investigated the same primary outcome scale in a similar setting. Had this not been available, we would have used the average ICC of all other cluster‐randomised trials in our review. If no such studies had been available, we would have used ICC = 0.05 as a conservative guess for the primary analysis, and added a sensitivity analysis using ICC = 0.10. We planned to conduct sensitivity analyses based on the unit of randomisation as well as the ICC estimate in cluster‐randomised trials (see Sensitivity analysis). | No cluster‐RCT was included in this review. |

| Multiple treatment groups Had multiple groups in a study been relevant, we would have accounted for the correlation between the effect sizes from multi‐arm studies in a pair‐wise meta‐analysis (Higgins 2019b). We would have treated each comparison between a control group and a treatment group as an independent study. We would have multiplied the standard errors of the effect estimates by an adjustment factor to account for correlation between effect estimates. In doing so, we would have acknowledged heterogeneity between different treatment groups. | For studies with multiple treatment groups, we considered only one intervention group to be relevant for the review and meta‐analyses, on the basis of the independent judgement of two review authors. Thus, in a pair‐wise meta‐analysis we did not have to account for the correlation between the effect sizes for multi‐arm studies. | |

| If there had been an adequate evidence base, we would have considered performing a network meta‐analysis (see Data synthesis). | The evidence base was not sufficient to conduct a network meta‐analysis. | |

| Dealing with missing data | If standard deviations could neither be recovered from reported results nor obtained from the authors, we would have considered single imputation by pooling within‐treatment standard deviations from all other studies, provided that fewer than five studies had missing standard deviations. If more than five studies had missing standard deviations, we would have performed multiple imputation on the basis of the hierarchical model fitted to the non‐missing standard deviations. | We found no studies using the same scale that had missing standard deviations. In addition, missing standard deviations could always be recovered from alternative statistical values or could be obtained from the study authors. |

| Data synthesis | Had a study reported more than one resilience scale, we would have used the scale with better psychometric qualities (as specified in Appendix 3 in Helmreich 2017), to calculate effect sizes. | All studies measuring resilience only used one resilience scale. |

| If a study had provided data from two instruments used equally often in the included RCTs, two review authors (AK, IH) would have identified the appropriate measure through discussion (compare Stoffers‐Winterling 2012). | This did not occur in this review. | |

| Network meta‐analyses (NMAs) would have been merely exploratory and would only have been conducted if the review results had a sufficient and adequate evidence base. Network meta‐analyses offer the possibility of comparing multiple treatments simultaneously (Caldwell 2005). They combine both direct (head‐to‐head) and indirect evidence (Caldwell 2005; Mills 2012), by using direct comparisons of interventions within RCTs, as well as indirect comparisons across trials on the basis of a common reference group (e.g. an identical control group) (Li 2011). As yet, a network meta‐analysis on resilience‐training programmes does not exist. According to Mills 2012, Linde 2016 and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Chaimani 2019), there are three important conditions for the conduct of NMAs: transitivity, homogeneity, consistency. Had an NMA been possible (i.e. the three conditions are fulfilled), we would have conducted an analysis, with expert statistical support as suggested by Cochrane (Chaimani 2019), using a frequentist approach in R (Rücker 2015; Viechtbauer 2010). For sensitivity analyses, the same models would have been fitted by the restricted maximum likelihood method (Piepho 2012; Piepho 2014; Rücker 2015). We would have considered categorising resilience training into seven groups, based on the underlying training concept: (1) cognitive behavioural therapy; (2) acceptance and commitment therapy; (3) mindfulness‐based therapy; (4) attention and interpretation therapy; (5) problem‐solving therapy; (6) stress inoculation therapy; and (7) multimodal resilience training. We might have included additional groups after the full literature search had been conducted. Reference groups that could have been included in the NMA were attention control, wait‐list, treatment as usual or no intervention. We planned to investigate inconsistency and flow of evidence in accordance with recommendations in the literature (e.g. Dias 2008; Chaimani 2019; König 2013; Krahn 2013; Krahn 2014; Lu 2006; Lumley 2002; Rücker 2015; Salanti 2008; White 2012b). |

The evidence base was not sufficient to support a network meta‐analysis. | |

| Summary of findings | Depending on the assessment of heterogeneity and possible effect modifiers (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity), we would have created several ‘Summary of findings’ tables; for example, for the clinical status of study populations or the comparator group. | We identified no consistent effect modifiers over the primary outcomes in subgroup analyses and therefore created no separate ‘Summary of findings’ tables. |

| Sensitivity analysis | If cluster‐randomised trials had been included, we would have performed sensitivity analyses based on the ICC estimate in cluster‐randomised trials that had not adjusted for clustering, by excluding cluster‐RCTs where standard errors were not corrected or corrected only on the basis of an externally‐estimated ICC. In an additional sensitivity analysis, we would have replaced all externally‐estimated ICCs that were less than 0.10, by 0.10. Finally, we would have conducted a sensitivity analysis for the unit of randomisation, by limiting the analysis to individually‐randomised trials. | No cluster‐RCT was included in this review. |

| ICC: Intra‐cluster correlation coefficient; RCT(s): randomised controlled trial(s) | ||

This table provides details of analyses that had been planned and described in the protocol (Helmreich 2017), including revisions made at review stage, but were not applied, as they were not required or not feasible.

Selection of studies

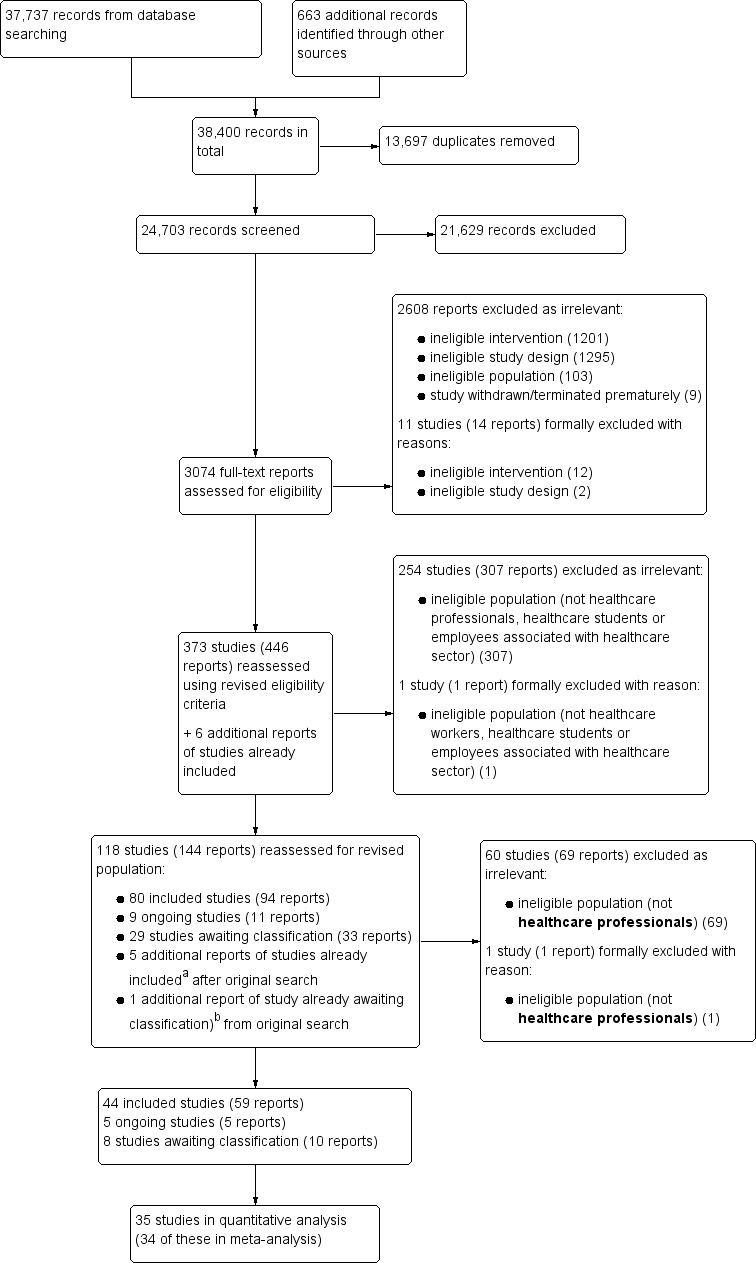

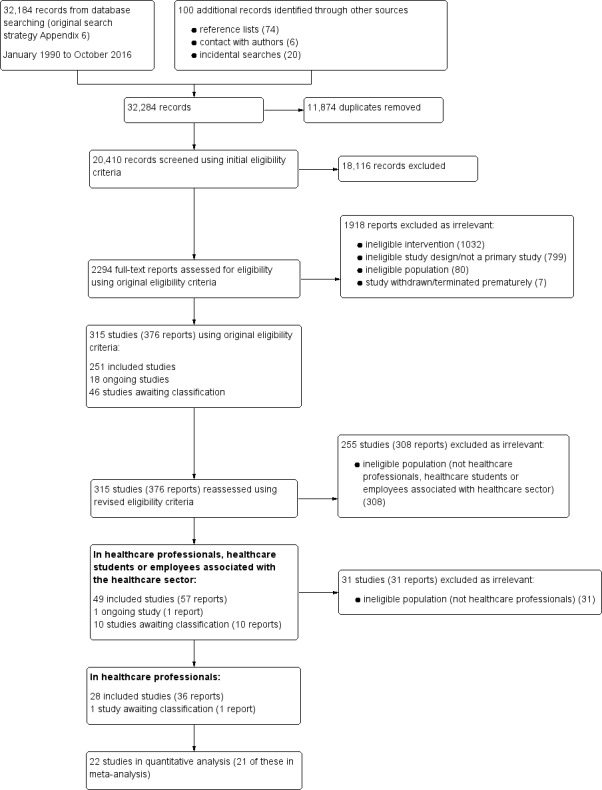

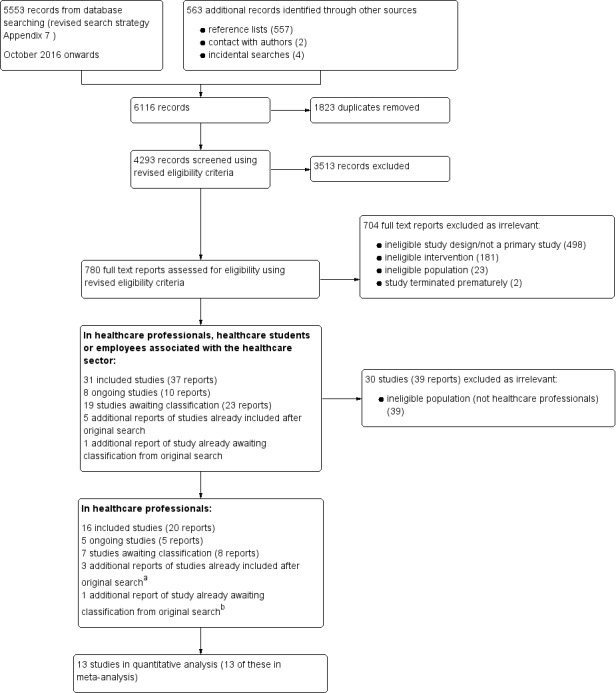

Two review authors (AK, IH) independently screened titles and abstracts in order to determine eligible studies. Clearly irrelevant papers were excluded immediately. At full text level, two review authors (AK, IH), working independently, checked eligibility in duplicate. We calculated inter‐rater reliability at both stages (title and abstract screening and full text screening), resolving any disagreements in study selection by discussion. Where we could not reach a consensus, a third review author (AC or KL) arbitrated. If necessary, we contacted the study authors to seek additional information. We recorded all decisions in a PRISMA flow diagram (Moher 2009).

We assessed the feasibility of the selection criteria a priori, by screening 500 studies in order to attain acceptable inter‐rater reliability (see Differences between protocol and review). There was a good agreement between the review authors (kappa = 0.72), and thus no need to refine or clarify the criteria. For scientific reasons, however, we adapted the eligibility criteria during review development (see Differences between protocol and review).

Data extraction and management

We developed a data extraction sheet (see Appendix 10), based on Cochrane guidelines (Li 2019), and tested it on 10 randomly‐selected included studies. This initial test resulted in sufficient agreement between the review authors. For each included study, two review authors (AK, IH) independently extracted the data in duplicate. The extraction sheet contained the following aspects:

source and eligibility;

study methods (e.g. design);

allocation process;

participant characteristics;

interventions and comparators;

outcomes and assessment instruments (means and standard deviations in any standardised scale);

results;

miscellaneous aspects.

We resolved any disagreements in data collection by discussion. Where we could not reach a consensus, a third review author (AC or KL) arbitrated. If necessary, we contacted the study authors to seek additional information.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (AK, IH) independently assessed the risks of bias of the included studies. We checked the risk of bias for each study using the criteria presented in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, hereafter referred to as the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011b), and set out in Appendix 11. We resolved any disagreements by discussion or by consulting a third review author (AC or KL). In accordance with Cochrane’s tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011a), we critically assessed the following domains:

sequence generation and allocation concealment (selection bias);

blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias);

blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias);

incomplete outcome data (attrition bias); and

selective outcome reporting (reporting bias).

We also considered the baseline comparability between study conditions as part of selection bias (random‐sequence generation), which is not defined in the Cochrane Handbook. In the first part of the assessment, we describe what was reported to have happened in the study for each domain, before assigning a judgement about the risk of bias (low, high or unclear) for the entry.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

We did not need to use our preplanned methods for analysing dichotomous outcomes (Helmreich 2017), as only two studies reported dichotomous data and both studies also provided continuous data that we were able to combine in a meta‐analysis.

Continuous data

Because the included resilience‐training studies used different measurement scales to assess resilience and related constructs (see Table 3, Table 4), we used the standardised mean difference (SMD) effect sizes (Cohen's d) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for continuous data in the pair‐wise meta‐analyses. We calculated effect sizes on the basis of means, standard deviations and sample sizes for each study condition. Where data were not provided, we computed Cohen's d from alternative statistics (e.g. t test, change scores). We assessed the magnitude of effect for continuous outcomes using the criteria for interpreting SMDs suggested in the Cochrane Handbook: a value of 0.2 indicates a small effect; a moderate effect is represented by 0.5; and 0.8 indicates a large effect (Schünemann 2019a).

2. Primary outcomes: scales used.

| Outcomes | Number of studies | Studies and instruments |

| Resilience | 21 |

|

| Anxiety | 12 |

|

| Depression | 24 |

|

| Stress or stress perception | 22 |

|

| Well‐being or quality of life | 20 |

|

aFor depression, we preferred depression scales over burnout scales if both forms of measure were reported. bIn two trials (West 2014; West 2015) we preferred continuous measures of burnout over dichotomous measures of depression, as they offered the possibility of being combined with other trials reporting continuous outcomes in meta‐analyses. cThe authors reportd that they would measure resilience with the emotional exhaustion subscale of the MBI. However, as this measure aims to assess burnout, we grouped the study under 'Depression' in this table. dFor trials reporting both general measures of well‐being or quality of life and work‐related assessments (e.g. job satisfaction, work‐related vitality), we preferred general measures.

3. Secondary outcomes: scales used.

| Outcomes | Number of studies | Studies and instruments |

| Social support (perceived) | 3 |

|

| Optimism | 3 |

|

| Self‐efficacy | 11 |

|

| Active coping | 5 |

|

| Self‐esteem | 1 |

|

| Hardiness | 1 |

|

| Positive emotions | 3 |

|

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

As allocation of individuals to different conditions in resilience intervention studies partly occurs by groups (e.g. work sites, hospitals), we intended to include cluster‐randomised trials along with individually‐randomised trials. Since we identified no cluster‐randomised trial, we have only included individually‐randomised trials in meta‐analyses.

Repeated observations on participants

If there were longitudinal designs with repeated observations of participants, we defined several outcomes based on different periods of follow‐up and conducted separate analyses, as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2019a). One analysis included all studies with measurement at the end of intervention (post‐test), other analyses were based on the period of follow‐up (short‐term: three months or less; medium‐term: more than three to six months; and long‐term: more than six months). We rated assessments as post‐intervention if performed within one week after the intervention. We counted assessments at more than one week after the intervention as short‐term follow‐up.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

If selected studies contained two or more intervention groups, two review authors (AK, IH) determined which group was relevant to the review and the particular meta‐analysis, based on the inclusion criteria for interventions (see Types of interventions). For all studies that included several intervention groups, we considered only one intervention group relevant for the review (see Types of interventions).

Dealing with missing data

In the case of studies where there were missing data, such as missing standard deviations (SDs), or where healthcare professionals had been combined with other participants, we contacted the study authors to inquire if the missing data or subgroup (summary outcome) data were available. Following the recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2019a), we computed missing SDs of continuous outcomes on the basis of other statistical information (e.g. t values, P values).

To obtain missing summary outcome data for studies solely conducted in healthcare professionals, we contacted the study authors (at least twice) to request the respective data (i.e. means, SDs and sample sizes for the relevant study conditions or alternative information to calculate the SMDs; see Measures of treatment effect).

In the case of missing outcome data due to attrition, we did not ask for individual‐level missing data and performed no re‐analysis using imputation methods. We rated studies with high levels of missing data (≥ 10%), that used no imputation methods at high risk of attrition bias (see Assessment of risk of bias in included studies). If the study authors had reported a complete‐case analysis as well as imputed data, we used the summary outcome data based on the imputed data set (e.g. baseline observation carried forward (BOCF) or ideally expectation maximization or multiple imputation).

We describe in detail those studies in which authors provided additional data not originally reported (e.g. number of participants analysed) in the Characteristics of included studies tables. We recorded missing data and attrition levels for each included study in the ‘Risk of bias’ tables (beneath the Characteristics of included studies tables). We also conducted a sensitivity analysis to examine the consequences of excluding studies with high levels of missing data (≥ 10% missing data in the respective outcome) on the results and subsequent conclusions of the review (see Sensitivity analysis).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed the presence of clinical heterogeneity by comparing the study and study population characteristics across all eligible studies (e.g. by generating descriptive statistics). In accordance with the Cochrane Handbook (Deeks 2019), we explored if studies were sufficiently homogeneous in participant characteristics, interventions and outcomes.

We assessed methodological diversity by inspecting the included studies for variability in study design and risks of bias (e.g. method of randomisation). In accordance with previous reviews, which already described great heterogeneity in resilience intervention studies (Joyce 2018; Leppin 2014; Macedo 2014; Robertson 2015; Vanhove 2016), we discussed similarities and differences between included studies in terms of these study characteristics in the Results and Discussion sections.

To assess statistical heterogeneity between included studies within each pair‐wise meta‐analysis (i.e. heterogeneity in observed treatment effects that exceeds sampling error alone), we relied on forest plots, Chi2 test, the tau2 statistic and the I2 statistic, as suggested by Deeks 2019. We also considered G2 to take small‐study effects into account (Rücker 2011). G2 indicates the proportion of unexplained variance, after having allowed for possible small‐study effects. No statistical heterogeneity is indicated by a G2 near zero. Significant statistical heterogeneity is indicated by a P value on the Chi2 test lower than 0.10. Since resilience‐training studies are often conducted with relatively small sample sizes (e.g. Loprinzi 2011; Sood 2014), we acknowledge that the Chi2 test has only limited power in such cases. Tau2 also provides an estimate of the between‐study variance in a random‐effects meta‐analysis. The I2 is a descriptive statistic, which equally reflects the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance. In accordance with guidelines (Deeks 2019), we supposed non‐important heterogeneity for I2 values of 0% to 40%, moderate heterogeneity for I2 values of 30% to 60%, substantial heterogeneity for I2 values of 50% to 90%, and considerable heterogeneity for I2 values between 75% and 100%. We also calculated the 95% prediction intervals from random‐effects meta‐analyses (see Data synthesis; pooled analyses with more than two studies) to present the extent of between‐study variation (Deeks 2019).

Where we observed heterogeneity (e.g. I2 greater than 50%, with consideration of the direction of effects and strength of evidence for heterogeneity (P value)), we conducted several subgroup analyses to investigate potential explanations (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

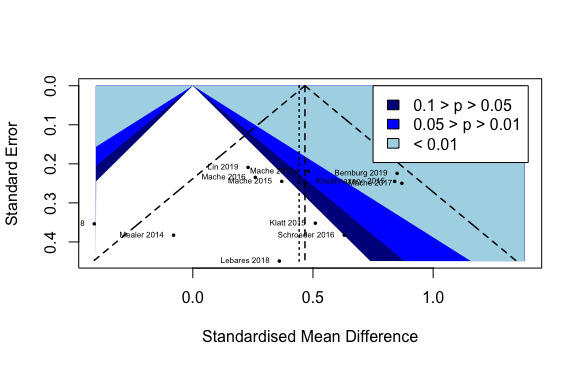

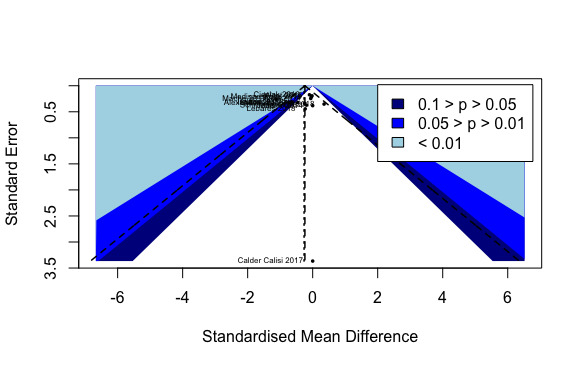

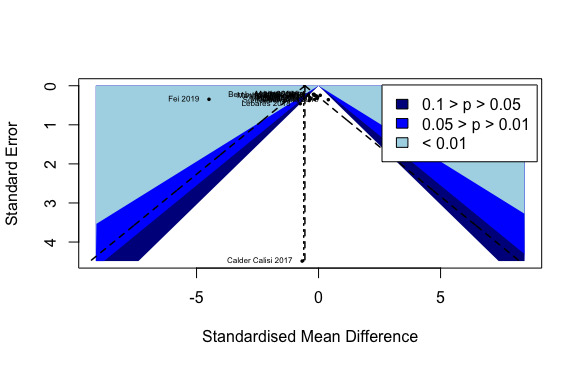

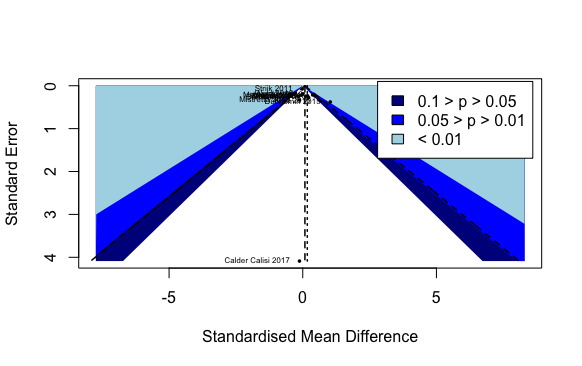

Assessment of reporting biases

We only performed analyses for reporting bias if there were at least 10 studies for an outcome. We assessed potential publication bias by inspecting (contour‐enhanced) funnel plots (plotting the effect estimates of trials against their standard errors on reversed scales) (Page 2019; Peters 2008). We considered the fact that funnel plot asymmetry does not necessarily reflect publication bias, but can stem from a number of reasons (Page 2019). To differentiate between real asymmetry and chance, we followed the recommendations in Page 2019, and also used Egger’s test (regression test; Egger 1997) to check for funnel plot asymmetry.

Data synthesis

We synthesised the results, in narrative and tabular form, by describing the resilience interventions, their theoretical concept (when possible), as well as the populations and outcomes studied (see Results). We performed the statistical analyses either in Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5; Review Manager 2014) or R (R 2019; libraries used: meta (Balduzzi 2019), metafor (Viechtbauer 2010) and metasens (Schwarzer 2019)), when appropriate.

We combined outcome measures of included studies through pair‐wise meta‐analyses (any resilience training versus control), in order to determine summary (pooled) intervention effects of resilience‐training programmes in healthcare professionals. The decision to summarise numerical results of RCTs in pair‐wise meta‐analyses depended on the number of studies found (at least two studies for a specific outcome and time point) as well as the homogeneity of the included studies by population (for age, sex), resilience interventions (i.e. comparable content and modalities), comparisons, outcomes measured (i.e. same prespecified outcome albeit with different assessment tools), and the methodological quality (risk of bias) of selected studies. We conducted meta‐analyses if intervention studies did not differ excessively in their content, if outcomes (measures) were not too diverse, and if there were no individual studies predominantly at high risk of bias.

For summary statistics for continuous data, we reported SMDs using an inverse‐variance random‐effects model. We used random‐effects pair‐wise meta‐analyses since we anticipated a certain degree of heterogeneity between studies, as indicated by the results of previous reviews (Joyce 2018; Leppin 2014; Macedo 2014; Robertson 2015; Vanhove 2016), and given the nature of the interventions. We calculated the 95% prediction intervals from random‐effects meta‐analyses (see Assessment of heterogeneity). As part of our sensitivity analyses, we also performed fixed‐effect analyses (see Sensitivity analysis). We analysed separately continuous data reported as means and standard deviations in some studies and outcomes where standardised mean differences and the respective standard error were obtained from different data (e.g. independent t test). We subsequently combined these values using the generic invariance method in Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014).

We also included studies with mixed samples (i.e. healthcare professionals and non‐healthcare professionals) in meta‐analyses if the subgroup data for healthcare professionals were reported separately or could be obtained from the study authors. If subgroup data were not available, we provide a narrative report of the findings of these studies in a separate section (see Effects of interventions > Studies with mixed samples) for each outcome.

All studies measuring resilience used only one resilience scale. If a study reported more than one instrument for mental health and well‐being outcomes or for a specific resilience factor, we used the measure most often used among the included studies for effect size calculation. For the outcome of depression, we preferred depression scales over burnout scales if both measures were reported. For studies reporting both general measures of well‐being or quality of life and work‐related assessments (e.g. job satisfaction, work‐related vitality), we preferred general measures.

Once we had produced a summary of the evidence to date, and only if a pair‐wise meta‐analysis (any resilience training versus control) was possible, we checked whether the data were also suitable for a network meta‐analysis (NMA). There was not enough evidence to perform a NMA.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

As we detected substantial heterogeneity for several outcomes (see Effects of interventions), we examined the characteristics of studies that may be associated with this diversity (Deeks 2019). The selection of potential effect modifiers is based on experience with previous reviews (Joyce 2018; Leppin 2014; Robertson 2015; Vanhove 2016). Where we could extract the necessary data, we performed the following subgroup analyses, classifying the RCTs as follows.

Setting of resilience interventions (group setting vs individual setting vs combined setting vs setting not specified).

Delivery format of resilience interventions (face‐to‐face vs online or mobile‐based vs telephone vs bibliotherapy vs laboratory vs multimodal delivery vs delivery not specified).

Intensity of resilience interventions (low intensity vs moderate intensity vs high intensity). Low‐intensity training includes interventions with a total duration of up to five hours or up to three sessions, respectively, if no duration in hours or minutes was indicated. Moderate intensity refers to training programmes including more than five hours to 12 hours, or more than three to 12 or fewer sessions. We categorised resilience interventions with more than 12 hours or more than 12 sessions, respectively, as high‐intensity training.

Theoretical foundation of resilience‐training programmes (CBT vs stress inoculation vs problem‐solving training vs ACT vs mindfulness‐based therapy vs AIT vs coaching vs positive psychology vs combination vs unspecific resilience training). 'Combination' refers to resilience interventions that were based on two or more explicit theoretical foundations, such as CBT and ACT or CBT and mindfulness. Unspecific training programmes include resilience interventions fostering one or several resilience factors but without specifying any explicit theoretical foundation, or where the underlying framework could not be assigned to a specific theoretical foundation.

Comparator group in intervention studies (attention control vs active control vs wait‐list control vs TAU vs no intervention vs control group not further specified). Attention control groups refer to an alternative treatment that mimicked the amount of time and attention received (e.g. by the trainer) in the intervention group. In this review, we use the term ‘active control’ for alternative treatment (no standard care; for example, treatment developed specifically for the treatment study) but that did not control for the amount of time and attention in the intervention group, and was not attention control in a narrow sense.

We calculated pooled effect sizes for each subgroup. Subgroup analyses were restricted to primary outcomes with at least 10 studies included in a meta‐analysis (Deeks 2019). Except for training intensity (post hoc addition), we prespecified all subgroup analyses in the protocol (Helmreich 2017). For delivery format, theoretical foundation and comparator, we added some subgroups based on the evidence we found.

Sensitivity analysis

We also restricted sensitivity analyses to primary outcomes with at least 10 trials in the meta‐analysis.

We performed sensitivity analyses:

based on the underlying concept of resilience, by limiting pooled analyses to scales assessing resilience as a state‐like outcome;

excluding studies at high risk of attrition and reporting bias (see Risk of bias in included studies), respectively; we conducted subgroup analyses to test if studies judged at low and unclear risk of bias could be pooled in analysis;

limiting the analyses to registered studies, as intended (Helmreich 2017), with registration identified depending on whether we found a trial registration or whether the authors claimed to have registered a study (see Characteristics of included studies);

limiting the analyses to those studies with low levels of missing data (less than 10% in the relevant primary outcome);

restricting the analyses to studies with less than 10% missing primary outcome data and where missing data had been imputed or accounted for by fitting a model for longitudinal data;

using a fixed‐effect pair‐wise meta‐analyses, to test the robustness of the findings.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

In this review, we used the software developed by the GRADE Working Group: GRADEpro: Guideline Development Tool (GRADEpro GDT) to create a 'Summary of findings' table for the comparison: resilience interventions versus control conditions for healthcare professionals.

We included all primary outcomes at post‐test in the 'Summary of findings' table. For each outcome, we assessed the certainty of the body of evidence using the GRADE approach proposed by the GRADE working group (Schünemann 2013; Schünemann 2019b), across the following five GRADE considerations:

limitations in the design and implementation of available studies (i.e. unclear or high risk of bias of studies contributing to the respective outcome; Guyatt 2011a);

indirectness of evidence (i.e. included studies limited to certain participants, intervention types, or comparators; Guyatt 2011b);

unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results (i.e. heterogeneity based on variation of effect estimates, CIs, the statistical test of heterogeneity and I2, but the subgroup analyses fail to identify a plausible explanation; Guyatt 2011c);

imprecision of results (i.e. small number of participants included in an outcome and wide CIs; Guyatt 2011d); and

high probability of publication bias (i.e. high risk of selective outcome reporting bias for studies contributing to the outcome based on funnel plot asymmetry, Egger's test, different results of published vs unpublished studies, and whether the evidence consisted of many small studies with potential conflicts of interest) (Guyatt 2011e).