Abstract

Background

There is a common perception that smoking generally helps people to manage stress, and may be a form of 'self‐medication' in people with mental health conditions. However, there are biologically plausible reasons why smoking may worsen mental health through neuroadaptations arising from chronic smoking, leading to frequent nicotine withdrawal symptoms (e.g. anxiety, depression, irritability), in which case smoking cessation may help to improve rather than worsen mental health.

Objectives

To examine the association between tobacco smoking cessation and change in mental health.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group's Specialised Register, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, and the trial registries clinicaltrials.gov and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, from 14 April 2012 to 07 January 2020. These were updated searches of a previously‐conducted non‐Cochrane review where searches were conducted from database inception to 13 April 2012.

Selection criteria

We included controlled before‐after studies, including randomised controlled trials (RCTs) analysed by smoking status at follow‐up, and longitudinal cohort studies. In order to be eligible for inclusion studies had to recruit adults who smoked tobacco, and assess whether they quit or continued smoking during the study. They also had to measure a mental health outcome at baseline and at least six weeks later.

Data collection and analysis

We followed standard Cochrane methods for screening and data extraction. Our primary outcomes were change in depression symptoms, anxiety symptoms or mixed anxiety and depression symptoms between baseline and follow‐up. Secondary outcomes included change in symptoms of stress, psychological quality of life, positive affect, and social impact or social quality of life, as well as new incidence of depression, anxiety, or mixed anxiety and depression disorders.

We assessed the risk of bias for the primary outcomes using a modified ROBINS‐I tool. For change in mental health outcomes, we calculated the pooled standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for the difference in change in mental health from baseline to follow‐up between those who had quit smoking and those who had continued to smoke. For the incidence of psychological disorders, we calculated odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs. For all meta‐analyses we used a generic inverse variance random‐effects model and quantified statistical heterogeneity using I2. We conducted subgroup analyses to investigate any differences in associations between sub‐populations, i.e. unselected people with mental illness, people with physical chronic diseases.

We assessed the certainty of evidence for our primary outcomes (depression, anxiety, and mixed depression and anxiety) and our secondary social impact outcome using the eight GRADE considerations relevant to non‐randomised studies (risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, indirectness, publication bias, magnitude of the effect, the influence of all plausible residual confounding, the presence of a dose‐response gradient).

Main results

We included 102 studies representing over 169,500 participants. Sixty‐two of these were identified in the updated search for this review and 40 were included in the original version of the review. Sixty‐three studies provided data on change in mental health, 10 were included in meta‐analyses of incidence of mental health disorders, and 31 were synthesised narratively.

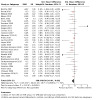

For all primary outcomes, smoking cessation was associated with an improvement in mental health symptoms compared with continuing to smoke: anxiety symptoms (SMD −0.28, 95% CI −0.43 to −0.13; 15 studies, 3141 participants; I2 = 69%; low‐certainty evidence); depression symptoms: (SMD −0.30, 95% CI −0.39 to −0.21; 34 studies, 7156 participants; I2 = 69%' very low‐certainty evidence); mixed anxiety and depression symptoms (SMD −0.31, 95% CI −0.40 to −0.22; 8 studies, 2829 participants; I2 = 0%; moderate certainty evidence). These findings were robust to preplanned sensitivity analyses, and subgroup analysis generally did not produce evidence of differences in the effect size among subpopulations or based on methodological characteristics. All studies were deemed to be at serious risk of bias due to possible time‐varying confounding, and three studies measuring depression symptoms were judged to be at critical risk of bias overall. There was also some evidence of funnel plot asymmetry. For these reasons, we rated our certainty in the estimates for anxiety as low, for depression as very low, and for mixed anxiety and depression as moderate.

For the secondary outcomes, smoking cessation was associated with an improvement in symptoms of stress (SMD −0.19, 95% CI −0.34 to −0.04; 4 studies, 1792 participants; I2 = 50%), positive affect (SMD 0.22, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.33; 13 studies, 4880 participants; I2 = 75%), and psychological quality of life (SMD 0.11, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.16; 19 studies, 18,034 participants; I2 = 42%). There was also evidence that smoking cessation was not associated with a reduction in social quality of life, with the confidence interval incorporating the possibility of a small improvement (SMD 0.03, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.06; 9 studies, 14,673 participants; I2 = 0%). The incidence of new mixed anxiety and depression was lower in people who stopped smoking compared with those who continued (OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.86; 3 studies, 8685 participants; I2 = 57%), as was the incidence of anxiety disorder (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.34 to 1.12; 2 studies, 2293 participants; I2 = 46%). We deemed it inappropriate to present a pooled estimate for the incidence of new cases of clinical depression, as there was high statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 87%).

Authors' conclusions

Taken together, these data provide evidence that mental health does not worsen as a result of quitting smoking, and very low‐ to moderate‐certainty evidence that smoking cessation is associated with small to moderate improvements in mental health. These improvements are seen in both unselected samples and in subpopulations, including people diagnosed with mental health conditions. Additional studies that use more advanced methods to overcome time‐varying confounding would strengthen the evidence in this area.

Keywords: Humans; Middle Aged; Affect; Anxiety; Anxiety/therapy; Confidence Intervals; Controlled Before-After Studies; Depression; Depression/therapy; Incidence; Mental Disorders; Mental Disorders/epidemiology; Mental Disorders/therapy; Mental Health; Quality of Life; Smoking; Smoking/adverse effects; Smoking/psychology; Smoking Cessation; Smoking Cessation/methods; Smoking Cessation/psychology; Social Interaction; Stress, Psychological; Stress, Psychological/therapy; Tobacco Use Cessation; Tobacco Use Cessation/methods; Tobacco Use Cessation/psychology

Plain language summary

Does stopping smoking improve mental health?

Smoking and mental health

Some health providers and people who smoke believe that smoking helps reduce stress and other mental health symptoms, like depression and anxiety. They worry that stopping smoking may make mental health symptoms worse. However, studies have shown that smoking may have a negative impact on people's mental health, and stopping smoking could reduce anxiety and depression.

Why we did this Cochrane Review

We wanted to find out how stopping smoking affects people's mental health. If stopping smoking improves mental health symptoms, rather than worsening them, then this may encourage more people to try to quit smoking and more health professionals to help their patients to quit. It may also discourage people from beginning to smoke tobacco in the first place.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that lasted for at least six weeks that included people who were smoking at the start of the studies. To be included, studies also had to measure whether people did or did not stop smoking and any changes in mental health during the study.

We were interested in how stopping smoking affected:

‐ symptoms of anxiety;

‐ symptoms of depression;

‐ symptoms of anxiety and depression together;

‐ symptoms of stress;

‐ overall well‐being;

‐ mental health problems;

‐ social well‐being, personal relationships, isolation and loneliness.

Search date: we included evidence published up to 7 January 2020.

What we found

We found 102 studies in more than 169,500 people: some studies did not clearly report how many people took part. The studies used a range of different assessment scales to measure people's mental health symptoms.

Most studies included people from the general population (53 studies); 23 studies included people with mental health conditions; other studies included people with physical or mental health conditions, or long‐lasting physical conditions, who had recently had surgery, or who were pregnant.

We combined and compared the results from 63 studies that measured changes in mental health symptoms, and from 10 studies that measured how many people developed a mental health disorder during the study.

What are the results of our review?

Compared with people who continued to smoke, people who stopped smoking showed greater reductions in:

‐ anxiety (evidence from 3141 people in 15 studies);

‐ depression (7156 people in 34 studies); and

‐ mixed anxiety and depression (2829 people in 8 studies).

Our confidence in our results was very low (for depression), low (for anxiety), and moderate (for mixed anxiety and depression). Our confidence was reduced because we found limitations in the ways the studies were designed and carried out.

Compared with people who continued to smoke, people who stopped smoking showed greater improvements in:

‐ symptoms of stress (evidence from 4 studies in 1792 people);

‐ positive feelings (13 studies in 4880 people); and

‐ mental well‐being (19 studies in 18,034 people).

There was also evidence that people who stopped smoking did not have a reduction in their social well‐being, and their social well‐being may have increased slightly (9 studies in 14,673 people).

In people who stopped smoking, new cases of mixed anxiety and depression were fewer than in those who continued to smoke (evidence from 3 studies in 8685 people). New cases of anxiety were also fewer (2 studies in 2293 people). We were unable to come to a decision about the numbers of new cases of depression, as the results from different studies were too variable.

Key messages

People who stop smoking are not likely to experience a worsening in their mood long‐term, whether they have a mental health condition or not. They may also experience improvements in their mental health, such as reductions in anxiety and depression symptoms.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Associations between quitting smoking and change in mental health symptoms.

| Associations between quitting smoking and change in mental health symptoms | ||||

| Patient or population: various, including general population, pregnant people, psychiatric populations (ADHD, alcohol use disorder, anxiety disorder, depression, psychosis, PTSD, various SMI) and populations with chronic health conditions (acute coronary syndrome, AIDS, AS, brain injury, cancer, CHD, COPD, HIV) Setting: Australia, Belgium, Canada, China, Japan, Netherlands, Portugal, South Korea, Spain, Turkey, UK, USA Intervention: Quitting tobacco smoking Comparison: Continuing to smoke tobacco | ||||

| Outcomes | Probable outcome with intervention | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

Change in anxiety

assessed with various anxiety symptom scales

follow‐up: range 6 weeks to 2 years Higher score indicates higher‐intensity anxiety symptoms |

The mean change in anxiety score was 0.28 SDs lower (95% CI: −0.43 to −0.13) in people who quit smoking compared to people who continued smoking | 3141 (15 observational studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b,c | According to Cohen 1988's interpretation of effect size 0.2 represents a small effect, 0.5 represents a moderate effect, and 0.8 represents a large effect. According to this rule of thumb, the effects found here are small to moderate. However, they are similar to the effects of antidepressant medications on anxiety disorder, which are deemed to be clinically meaningful (NCCMH 2011). |

|

Change in depression

assessed with various depression symptom scales

follow‐up: range 6 weeks to 6 years Higher score indicates higher‐intensity depression symptoms |

The mean change in depression score was 0.3 SDs lower (95% CI: −0.39 to −0.21) in people who quit smoking compared to people who continued smoking | 7156 (34 observational studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWd,e,f | |

|

Mixed anxiety and depression

assessed with various mixed anxiety and depression symptom scales

follow‐up: range 3 months to 6 years Higher scores indicates higher‐intensity mixed anxiety & depression symptoms |

The mean change in mixed anxiety and depression score was 0.31 SDs lower (95% CI: −0.40 to −0.22) in people who quit smoking compared to people who continued smoking | 2829 (8 observational studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | |

| ADHD: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; AIDS: acquired immune deficiency syndrome; AS: ankylosing spondylitis; CHD: coronary heart disease; CI: Confidence interval; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; PTSD: post‐traumatic stress disorder; SD: standard deviation; SMI: serious mental illness | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||

aDowngraded one level due to risk of bias: all studies were deemed to be at serious risk of bias. bDowngraded one level due to inconsistency: there was substantial heterogeneity between study effects (I2 = 69%) unaccounted for by subgroup and sensitivity analyses. Whilst some studies appeared to show evidence of a positive association with quitting smoking, others showed no clear evidence of benefit or harm. cPublication bias: although the funnel plot shows some evidence of asymmetry, statistical tests suggest this is unlikely to affect the pooled result. We therefore did not downgrade on the basis of publication bias. dDowngraded one level due to risk of bias: all studies were rated at serious or critical risk of bias. Removal of the three studies at critical risk of bias did not change the interpretation of the result. eDowngraded one level due to inconsistency: there was substantial statistical heterogeneity between study effects (I2 = 69%) unaccounted for by subgroup and sensitivity analyses. Whilst some studies appeared to show evidence of a positive association with quitting, others showed no clear evidence of benefit or harm, with only one study providing evidence of an increase in depression associated with quitting smoking. fPublication bias suspected, as the funnel plot indicates asymmetry, with a lack of smaller studies indicating an association between quitting and increased symptoms of depression. Egger's test also indicated potential publication bias.

Background

Description of the condition

Smoking is the world's leading cause of preventable illness and death (WHO 2011). One in every two people who smoke will die of a smoking‐related disease, unless they quit (Doll 2004; Pirie 2013). Although the prevalence of smoking has decreased markedly from the 1970s in high‐income countries; for example, in the UK it has fallen from 46% to approximately 14.9% in 2018 (ONS 2018; West 2019), prevalence remains higher in low‐ and middle‐income countries (GBD 2015 Tobacco Collaborators 2017). In addition, smoking prevalence amongst people with mental illness has declined only slightly and is currently around 32% in the UK (Richardson 2019; Szatkowski 2015; Taylor 2019a). People with mental illness who smoke are more heavily addicted, suffer from worse withdrawal (Hitsman 2013; Leventhal 2013; Leventhal 2014; RCP/RC PSYCH 2013), and are less responsive to standard treatments (Hitsman 2013; Taylor 2019a), even though they are motivated to quit (Haukkala 2000; Siru 2009). These inequalities contribute to a reduction in life expectancy of up to 17.5 years compared to the unselected population (Chang 2011; Chesney 2014).

Description of the intervention

Some people who smoke and healthcare providers believe that smoking can reduce stress and other symptoms related to mental illness, or that quitting smoking can exacerbate mental illness, and these beliefs maintain a culture of smoking (Cookson 2014; Sheals 2016). However, our previously‐published review (Taylor 2014) found an association between smoking cessation and improvements in mental health that were of a similar size to the effects reported in a systematic review of antidepressants for anxiety disorder (NCCMH 2011). We argued that this may be causal, and that smoking cessation could lead to improved mental health.

How the intervention might work

Chronic tobacco smoking is associated with neuroadaptations in nicotinic pathways in the brain. Neuroadaptations in these pathways are associated with the occurrence of withdrawal symptoms, such as depressed mood, agitation and anxiety. Withdrawal symptoms are alleviated by smoking and remain alleviated shortly after smoking, but symptoms return when blood levels of nicotine decline at around 20 minutes after smoking (Benowitz 1990; Benowitz 2010; Mansvelder 2002); this is known as the withdrawal cycle and is marked by fluctuations in a person's psychological state throughout the day (Benowitz 2010; Parrott 2003). People therefore mistake the ability of tobacco to alleviate tobacco withdrawal for an ability to alleviate mental health‐related symptoms. This misunderstanding has negative consequences in treating tobacco addiction in mental health populations, as many healthcare providers believe that by helping their patients to quit smoking, they will be harming their patients' mental health (Cookson 2014; Sheals 2016). Recent observational studies have used methods that support strong causal inference to indicate that smoking is associated with an increased risk of depression and schizophrenia (Wootton 2020), and that smoking cessation is associated with improved mental health outcomes (Taylor 2019a).

Why it is important to do this review

There is little convincing evidence that the smoking epidemic amongst people with mental illness is subsiding to the same level as that observed in the general population ‐ the gap in prevalence between people who smoke with and without mental illness is not closing (Richardson 2019; Taylor 2019a). Given evidence of therapeutic nihilism amongst healthcare professionals (Sheals 2016), strengthening, communicating and updating the evidence exploring the association between smoking and mental health is critically important to populations with mental illness. It could also encourage people without mental illness who smoke to quit, and discourage others from beginning to smoke tobacco.

Objectives

To examine the association between tobacco smoking cessation and change in mental health.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Controlled before‐after studies, including randomised controlled trials (RCTs) analysed by smoking status at follow‐up rather than comparing the randomised study arms, and longitudinal cohort studies.

Types of participants

We included studies of adults who smoked tobacco (using the definitions given in included studies and excluding people who exclusively used electronic cigarettes). There were no restrictions by population type or co‐morbid conditions.

Types of interventions

The 'intervention' was quitting smoking and the 'comparator' was continued smoking. We included any definition of quitting smoking, as defined by the included studies (e.g. self‐report, biovalidated, point prevalence, continuous). There was no minimum length of abstinence specified, but studies had to be at least six weeks long to be included in the review. Where more than one measure of successful quitting was used we used the most stringent definition to categorise participants into the 'intervention' and 'comparator' groups. We preferred Intention‐to‐treat categorisation over complete‐case categorisation, where people without a smoking status were assumed to be still smoking, as is common in the field (West 2005).

Types of outcome measures

Self‐report or clinician‐scored measures of mental health, as follows. We included continuous and new incidence (dichotomous) measures of mental health, or mental ill‐health.

Outcome categories in this review were developed by examining the questions for each scale, to determine what each scale measured. What the scales actually measure, as determined by examining the questions they ask, can differ from what the scale’s name indicates.For example, the assumption might be that the stress reaction subscale of the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ) measures stress, but the scale developers note that people who score highly on the scale describe themselves using a range of terms, such as, tense, nervous, sensitive, vulnerable, prone to worry and feeling anxious, and feeling miserable without reason (Tellegen 2008). These terms describe mixed anxiety and depression symptoms, and were grouped as such in this review.

Primary outcomes

Change in depression symptoms

Change in anxiety symptoms

Change in mixed anxiety and depression symptoms

Secondary outcomes

Change in symptoms of stress, psychological quality of life, and positive affect

Cumulative incidence of mental ill‐health, including dichotomous measures of depression, anxiety, stress, psychological quality of life, positive affect, mixed anxiety and depression occurring after study start

Social impact or social quality of life, including measures of social satisfaction, interpersonal relationships, isolation and loneliness. This outcome was included as we carried out patient and public involvement work to identify any outcomes of particular relevance to members of the public, which were not considered in the previous version of this review (Taylor 2014). Our work highlighted that people who smoke may be concerned that quitting could disrupt their social networks, and lead to feelings of loneliness. This may be of particular significance to people also experiencing mental ill‐health. Where studies reported more than one social impact outcome, we selected the outcome that most closely represented social impact on friendships. This is the element which was highlighted most notably in our patient and public involvement work.

Outcomes had to be measured at least six weeks following baseline in order for data to be included in the review. Where outcomes were measured at multiple time points within one study we took the measure with the longest follow‐up in each of the following categories (where possible):

between six weeks and six months follow‐up (inclusive of the upper and lower time point)

over six months follow‐up

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group's Specialised Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycINFO. The most recent searches of these databases for the previous non‐Cochrane version of this review were carried out on 13 April 2012 (Taylor 2014). The inclusion criteria specified in this Cochrane update of the review do not differ from those in the original review, so we included studies from the previous review in this update and conducted update searches from 14 April 2012 to 07 January 2020, to identify any new studies. See Appendix 1 for the MEDLINE search strategy.

Searching other resources

We searched the trial registries clinicaltrials.gov and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (who.int/clinical-trials-registry-platform).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Our aim was to maximise sensitivity by including studies in initial screens even if data directly relevant to our question were not presented in the abstract. The titles and abstracts of eligible titles were screened independently by two review authors (from GT, NL, AF, AL‐J, KS, RtWN) for inclusion. We resolved disagreements by discussion, and involved a third review author in discussions where necessary. We obtained the full‐texts of articles that were included at the title and abstract screening stage. Two review authors (from GT, NL, AF, AL‐J, KS, RtWN, AT, PA) independently screened each full‐text for inclusion, resolving disagreements by discussion and with a third review author where necessary. We recorded reasons for exclusion at the full‐text examination stage. We translated non‐English language studies and included them where appropriate.

Data extraction and management

Review authors piloted the data extraction form and made appropriate changes (GT, NL, AF, PA). One review author extracted 100% of study characteristics data for each study (from KS, CB, NK).These data were then checked by GT or CB.

Two review authors (from GT, NL, AF, AL‐J, KS, RtWN, AT, PA) independently extracted outcome and 'Risk of bias' data for each study. We compared data for each study and resolved any disagreements by discussion and by involving a third review author where necessary.

We extracted the following data from each study.

Study design

Analysis method

Outcome measure(s)

Length of follow‐up

N at baseline and follow‐up

Population type

Percentage (%) male

Mean age (standard deviation (SD))

Covariates adjusted for

Motivation to quit

Intervention(s) used (if relevant)

Risk of bias using ROBINS‐I (Sterne 2016)

Data to calculate standardised mean difference (SMD) in mental health outcomes: for each group ‐ mean at baseline and follow‐up, mean change from baseline to follow‐up, and difference in mean change from baseline to follow‐up, and variance

Data to calculate new incidence of mental ill‐health outcomes: for each group ‐ N participants in continued‐smoking group at follow‐up, N participants with outcome in continued‐smoking group at follow‐up, N participants in quitter group at follow‐up, N participants with outcome in quitter group at follow‐up. If effect estimates had been calculated and reported in study reports then we also extracted these

Sources of study funding and authors' declarations of interests

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risks of bias for each study that reported a primary outcome (continuously‐measured change in depression, anxiety or mixed anxiety and depression) using ROBINS‐I, which assesses studies based on risk of bias in the following domains: bias due to confounding; bias in selection of participants into the study; bias in classification of interventions; bias due to deviations from intended interventions; bias in measurement of outcomes; and bias in selection of the reported result (Sterne 2016). We modified the ROBINS‐I to ensure that it was appropriate to assess risk of bias for the association in question. The modified tool, and modifications with justifications, are available in Supplemental file 1 and Supplemental file 2 respectively.

The following relevant confounding variables were prespecified:

Time‐varying recreational drug and alcohol use, used individually or in combination, during the study period

Time‐varying psychoactive treatment use during the study period

Time‐varying significant life events during the study period (i.e. social changes, moving, divorce, having children, etc.)

The following psychoactive treatments that could have been different between people who quit and people who continued smoking, that could have impacted on mental health outcomes, were prespecified:

Psychological treatments that can improve mental health, i.e. cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for mood, mood management techniques, counselling for mood. Where treatments were provided that could be used for either smoking cessation or mood management we referred to the study protocol to ensure we did not misclassify smoking cessation treatments as mood treatments, e.g. 'CBT for smoking cessation'.

Pharmaceutical treatments, such as anti‐depressants (SSRIs, MAOIs or otherwise) and smoking cessation medicines that are also antidepressants (i.e. bupropion, nortriptyline, or otherwise).

Measures of treatment effect

For each study, for any outcome measured using continuous data, we calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD) (95% CI) in change in mental health from baseline to follow‐up, between those who had quit smoking and those who had continued to smoke. We calculated the SMD (95% CI) by extracting any of the following data, in order of preference:

adjusted or unadjusted mean difference (MD; difference in change from baseline to follow‐up) and measure of variation between exposure groups, with a preference for adjusted estimates;

mean change in mental health scores from baseline to follow‐up and measure of variance, by exposure group;

mean mental health scores and measures of variance at baseline and final follow‐up, by exposure group.

Where type 3) data were collected we then calculated the mean change and its variance for each exposure group (Follmann 1992); for data types 2) and 3) we calculated the SMD, using standard formulae outlined within the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2020). We also sought statistical support where appropriate.

For each study, for any outcome measured using dichotomous data (new incidence of mental ill‐health data), we calculated odds ratios (ORs) and the 95% CI. We calculated the ORs (95% CI) by extracting any of the following data, in order of preference:

adjusted or unadjusted ORs and a measure of variance;

other types of effect estimate that could be converted into ORs (i.e. risk ratios, hazard ratios);

we extracted data to calculate ORs for new incidence of mental ill‐health and its variance (N participants in continued‐smoking group at follow‐up, N participants with outcome in continued‐smoking group at follow‐up, N participants in quit group at follow‐up, N participants with outcome in quit group at follow‐up).

We then logged ORs using a standard formula before inputting them into meta‐analyses. We sought statistical support to help with the above calculations where appropriate.

Unit of analysis issues

None.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted corresponding authors of studies for additional data where it was evident that data had been analysed comparing our exposure groups of interest (people who quit smoking versus people who continued to smoke), but the data needed for analyses were not reported, for any of our outcomes. If we were unable to obtain the necessary data for meta‐analysis, we reported studies narratively.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We quantified statistical heterogeneity using I2, which describes the percentage (%) of between‐study variability due to variance between studies rather than chance. We considered an I2 value between 50% and 75% as substantial heterogeneity, and above 75% we assessed whether it was appropriate to report a pooled analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

We examined funnel plots for evidence of asymmetry and conducted Egger tests for evidence of small‐study bias where there were 10 or more studies contributing to any meta‐analysis. We used the Duval and Tweedie 'trim and fill' method to account for outcomes showing evidence of publication bias (Duval 2000). 'Trim and fill' adjusts the meta‐analysis to incorporate theoretically missing studies, and then estimates the pooled SMD incorporating imputed studies’ data. Using 'trim and fill' methods we imputed missing studies’ data, and compared pooled effect estimates between imputed and non‐imputed models.

We also conducted a subgroup analysis in which we compared effect estimates between studies in which mental health was the primary outcome and those in which it was not, to assess if there was evidence of publication bias (i.e. if mental health was a secondary outcome, was it more likely to be reported if it resulted in a clearly positive or negative effect).

Data synthesis

For continuous outcomes, we pooled SMDs (95% CI) across individual studies using a generic inverse variance random‐effects model. An SMD of greater than zero indicated that quitting smoking was associated with worse mental health at follow‐up for the anxiety, depression, mixed anxiety and depression, and stress outcomes, whereas an SMD of less than zero indicated that quitting smoking was associated with worse mental health at follow‐up for the positive affect, psychological quality of life, and social impact outcomes.

For dichotomous outcomes, we pooled log OR (95% CI) across individual studies using a generic inverse variance random‐effects model. An OR of greater than one indicated that people who quit smoking experienced a greater risk of mental ill‐health at follow‐up.

We conducted meta‐analyses of the SMD and OR for each outcome separately (i.e. depression, anxiety, stress, etc.) using RevMan 2014.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted the following subgroup analyses:

Adjustment for covariates: we compared effect estimates from studies that present adjusted and unadjusted estimates;

Motivation to quit: we classified studies according to whether they selected participants for inclusion based on motivation to quit. Participants in RCTs were classed as motivated to quit, assuming that participants enrolled in a trial to help them stop smoking, unless otherwise specified. They were compared with any other studies that followed a group of people who smoked, where most were unlikely to want to quit in the near future;

Study design: we compared estimates between secondary analyses of RCTs, cohort studies, and one study where participants were randomised to quit smoking or to continue smoking and paid to do so;

Population comparison: we examined whether there was evidence of a difference in effect size between studies in different clinical populations, e.g. unselected samples, pregnant women, or participants who were postoperative, had a chronic physical condition, a psychiatric condition, or chronic psychiatric or physical conditions;

Length of follow‐up: we examined whether there was evidence of a difference in effect estimate between studies that assessed change in mental health between six‐week and six‐month follow‐up or at more than six‐months follow‐up. Effects may differ because people who achieve a difficult life goal, such as quitting smoking, may have a temporary improvement in mental health because of their achievement. However, should the effect persist long‐term, this supports the hypothesis that smoking itself is harmful to mental health and it is ceasing smoking and not the celebration of that achievement that improves mood.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted the following sensitivity analyses:

Loss to follow‐up: we removed studies in which different numbers of participants were analysed at baseline and follow‐up;

Ascertainment of smoking status: we removed studies that did not biochemically validate follow‐up smoking status;

Psychotherapeutic/psychoactive component within cessation intervention: we removed studies that offered an evidence‐based psychotherapeutic or psychoactive (i.e. psychotherapy or antidepressants) component within the smoking cessation intervention;

Risk of bias: We removed studies judged to be at critical risk of bias.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We created a 'Summary of findings' table, using GRADEpro GDT software, reporting the pooled effect estimates for our primary outcomes (depression, anxiety, and mixed depression and anxiety) and our secondary social impact outcome. We assessed these outcomes according to the eight GRADE considerations relevant to non‐randomised studies (Schünemann 2013; i.e. risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, indirectness, publication bias, magnitude of the effect, the influence of all plausible residual confounding, the presence of a dose‐response gradient) to assess the certainty of the body of evidence for these outcomes, and to draw conclusions about the certainty of the evidence within the text of the review.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

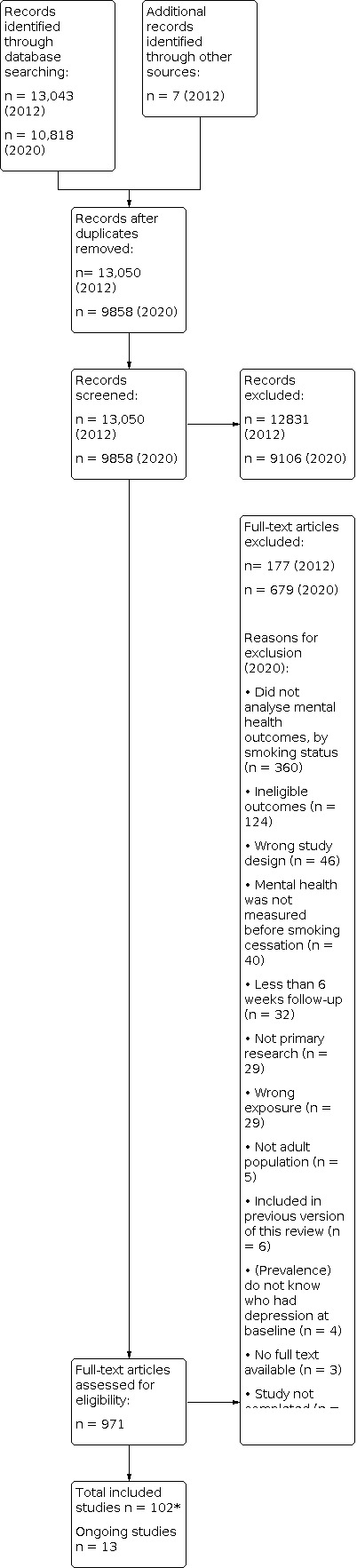

Results of the search

In this update of the review our searches identified 10,818 records. After removal of duplicates, we screened the titles and abstracts of 9858, of which 9106 were irrelevant. We assessed 752 full‐text studies for inclusion, of which we dropped 677, with reasons.

In the 2014 version of the review (searches conducted from inception to 30 April 2012) we identified 13,050 records. We screened the titles and abstracts of these records, of which 12,831 were irrelevant. We assessed 219 full‐texts for inclusion, of which we dropped 177, with reasons. We re‐examined 11 full‐text records that we had excluded from the previous version of this review for presenting dichotomous outcomes, and assessed if they were eligible for the current review.

Examples of studies that were excluded, with reasons for exclusion, are available in Characteristics of excluded studies. See Figure 1 for a flow diagram.

1.

Study Flow Diagram 2020

(*40 of these studies were identified through the 2012 literature searches)

Included studies

As a result of both the 2014 review and the 2020 screening we include 102 studies in this review (40 that were included in the 2014 version, and 62 from the 2020 searches). We include 63 studies in our meta‐analyses of continuous measures of change in mental health, 10 were included in our meta‐analyses of incidence of clinical mental health disorders, and 31 were included in the narrative synthesis (two studies were included in the meta‐analysis and narrative review because they reported data suitable for meta‐analysis for one outcome, and data only suitable for narrative synthesis for another outcome: Mathew 2013; McFall 2006).

Forty‐five of the included studies were cohort studies, 56 were secondary analyses of randomised controlled trials analysed as observational cohorts, and one was a randomised trial in which participants were randomised to quit or to continue smoking (Dawkins 2009).

Participants

This review includes over 169,500 participants, with 42,000 included in meta‐analyses. It is not possible to give exact numbers, because some studies did not report the total number of participants that were included in their analyses.

The median age across studies was 45.2 years, and the median percentage of men was 51%. Participants smoked a median of 20.3 cigarettes a day at baseline and had a median score of 5.4 on the Fagerström test for nicotine dependence, indicating medium dependence levels.

Studies enrolled people from a range of populations: people with a chronic physical or psychiatric condition (2 studies) or both, people with a chronic physical condition (16 studies), post‐surgical patients (3 studies), pregnant women (4 studies), people with psychiatric conditions (23 studies), and the unselected population (57 studies). Three studies provided data on both the general population and on people with psychiatric conditions (Hammett 2019; Heffner 2019; Vermeulen 2019).

Intervention/exposure

The way abstinence was measured varied across studies. In 33 studies, abstinence was defined as a period of prolonged abstinence, typically defined from a point at or soon after the quit date. In all the other studies, apart from six where the definition was unclear (three studies included in meta‐analyses, and three summarised narratively), abstinence was defined as point prevalence (not smoking for a period, such as 24 hours or seven days, prior to the assessment, or at the time of the assessment only). In 66 studies, abstinence was biologically verified, usually through measuring participants' exhaled carbon monoxide or cotinine concentration.

In 33 studies, the length of participants' abstinence was unclear. In most cases this is where point prevalence abstinence was used as a definition, and so we could not tell when their time of abstinence began, i.e. participants were simply asked whether they were smoking or not at a follow‐up point. If people replied that they were not smoking at the follow‐up point it was not always clear when they had made their original quit attempt, and this has the potential to vary across participants within a study. However, the implications of this vary by study type. For RCTs, it would be reasonable to assume that, for most people, abstinence began on the study quit date, but for cohort studies the period of abstinence could have happened at any time from baseline to follow‐up. In the remaining studies length of abstinence was clearer: in 18 studies, with follow‐up at least six weeks after baseline, participants were assessed as abstinent for between one and three months of the follow‐up period; in 48 studies six‐ or 12‐month abstinence was assessed, and in three studies the maximum potential length of abstinence was over one year, with a maximum of 10 years (Sanchez‐Villegas 2008).

In 39 studies, participants were reported to be receiving a 'mood management' intervention (e.g. a psychological or medicinal treatment that could viably improve mental health), either externally to the study or as part of the study. Examples of these were antidepressants (Anthenelli 2013;Qi Zhang 2014; Sanchez‐Villegas 2008); behavioural mood‐management counselling (Blalock 2008; Krebs 2018; Qi Zhang 2014); or counselling on the emotional aspects of addiction (Segan 2011). In 73 studies, participants were motivated to quit, as defined by the study's selection criteria.

Outcomes

Forty‐two studies provided data for more than one of our prespecified outcomes. The median length of follow‐up was six months. Collectively the included studies reported on seven different measures of mental health: anxiety, depression, mixed anxiety and depression, positive affect, psychological quality of life, stress and social quality of life. Studies that reported social quality of life measured this using scales assessing the quality of social relationships. Where studies reported more than one social quality‐of‐life outcome, we selected the outcome which represented quality of friendships. We did this as the person involved in our patient and public involvement exercise was concerned about the impact of smoking cessation on their friendships. We chose between social quality‐of‐life scales in only one study (Leventhal 2014).

Full details of each included study can be found in Characteristics of included studies.

Ongoing studies

We identified 13 ongoing studies, which we will include in future updates. Full details of these studies can be found in Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Excluded studies

The primary reasons for excluding records were that the study

did not analyse mental health outcomes, by smoking status as an exposure;

did not collect mental health outcomes;

the outcomes were not eligible for this review (e.g. outcomes were cognitive in nature);

the study design was not eligible (e.g. qualitative study or cross‐sectional design); or

mental health was not measured before smoking cessation.

Other reasons are available in the PRISMA flow chart, and a list of sample excluded records is available in Excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

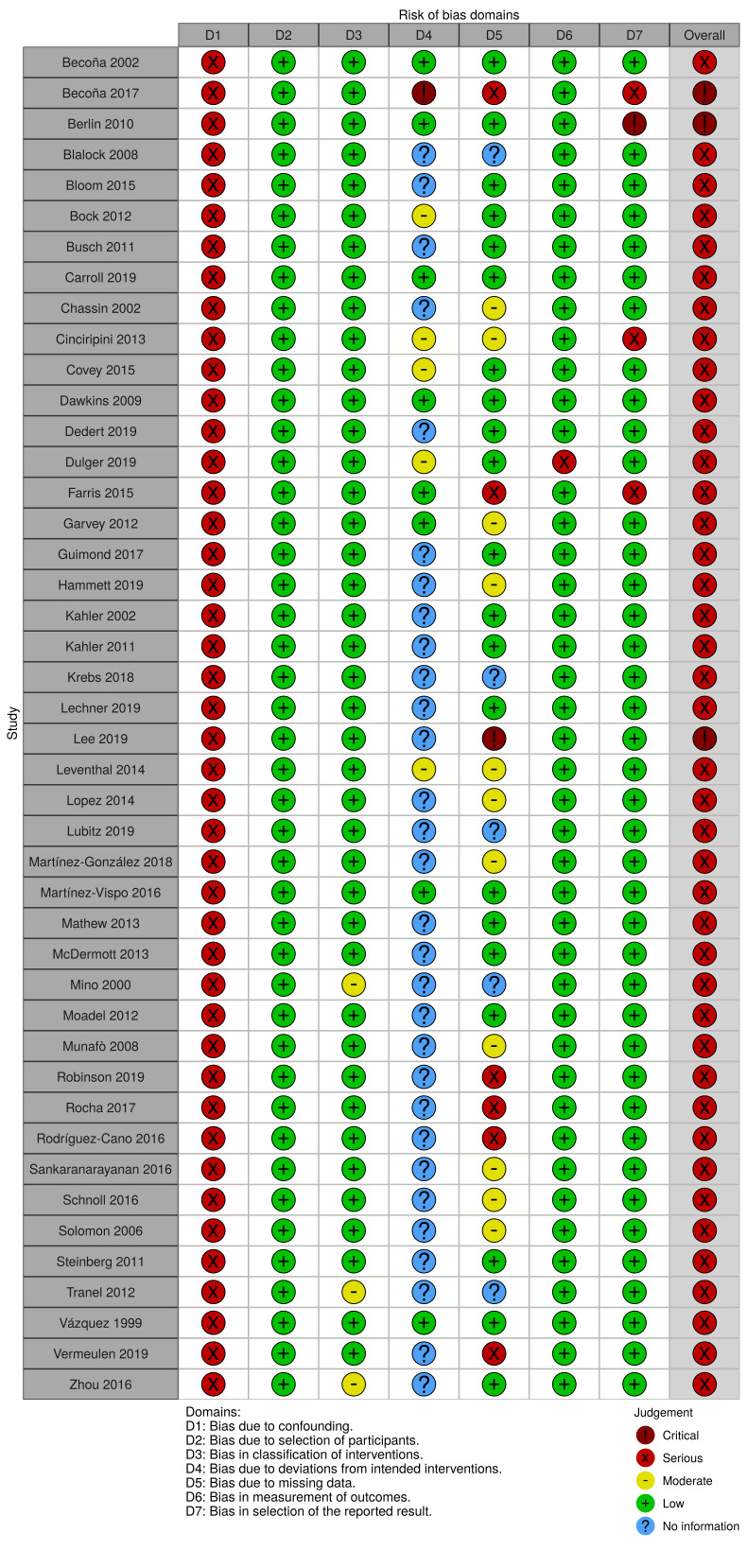

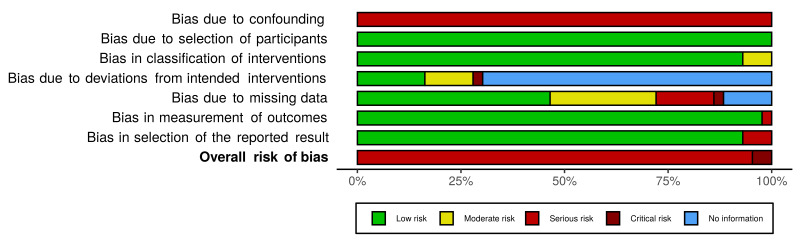

See Supplemental file 3; Supplemental file 4; Supplemental file 5; Figure 2; Figure 3 (figures generated using robvis; McGuiness 2020)

2.

Risk‐of‐bias: “traffic light” plot of the domain‐level judgements for each individual result according to the ROBINS‐I tool

3.

Risk‐of‐bias: Weighted bar plot of the distribution of risk‐of‐bias judgements within each bias domain according to the ROBINS‐I tool

We assessed risks of bias for each of the studies contributing to the meta‐analysis for the three primary outcomes (anxiety, depression, mixed anxiety and depression). We used a modified version of the ROBINS‐I tool to do so and assessed the domains highlighted below.

Bias due to confounding

We judged all studies across all three primary outcomes to be at serious risk of bias due to confounding. In all cases this was because the authors did not use methods that adequately controlled for all the potential time‐varying confounding, i.e. changes in recreational drug and alcohol use, change in psychoactive medication use and significant life events during the study period. This was because changes in each of these factors were not measured in the first instance, rather than that they were measured and then not adjusted for in analyses. An example of potential time‐varying confounding that was not accounted for in the studies is as follows: a person who experienced a stressful life event, such as divorce, during the course of the study would be both less likely to quit smoking (and therefore more likely to appear in the continuing‐smokers group), and more likely to experience worsened mental health. In this instance the difference in change between this person who continues smoking and someone else who quits would not be entirely explained by the change or lack of change in their smoking behaviour.

Bias in selection of participants into the study

We judged all studies across all three primary outcomes to be at low risk of bias for this domain. This is because the selection of participants into studies (or into the analyses) was not based on participant characteristics observed after participants made an attempt to quit smoking.

Bias in the classification of follow‐up smoking status

We rated all 15 studies contributing to the primary anxiety analysis at low risk of bias due to the classification of follow‐up smoking status. In all cases the differentiation between continued smoking and smoking cessation was clearly defined using a definition commonly used in the field.

We judged 32 of the studies that contributed to the primary depression analysis to be at low risk of bias for this domain; however we rated two studies (Tranel 2012; Zhou 2016) at moderate risk, as they did not clearly define abstinence.

Of the eight studies contributing to the primary mixed anxiety and depression outcome, we judged all but one study to be at low risk. Mino 2000 did not report the definition of cessation used and so was rated at moderate risk of bias for this domain.

Bias due to deviations from quitting smoking (i.e. relapsing) or through access to psychoactive treatments

For the anxiety outcome, we judged three of the studies contributing to the analysis to be at low risk of bias due to deviations from the 'intervention' (Becoña 2002; Dawkins 2009; Farris 2015). The ways that these studies were protected against this type of bias were by excluding potential participants who were receiving psychotherapy or psychoactive drugs, or had a psychiatric diagnosis; by not providing a psychoactive intervention as part of the study; or by adjusting for the imbalance in psychoactive treatment between the exposure and comparator groups in the analyses. We rated a further three studies at moderate risk of bias. In Bock 2012 there were some deviations from the intended intervention, but their impact on the outcome was expected to be slight. Participants were randomly allocated to either cognitive behavioural therapy for smoking cessation, Vinyasa yoga, or a general health and wellness programme. The authors reported that the yoga programme improved negative affect, and enhanced smoking cessation rates at eight‐week follow‐up, but that the effect on smoking cessation did not persist to the later follow‐up points. Covey 2015 did not use an analysis method that appropriately addressed the issue of relapsing, and in Dulger 2019 bupropion hydrochloride (an antidepressant and smoking cessation treatment) was provided to 42.6% of participants. The remaining nine studies did not provide enough information to answer the signalling questions in order to make an informed judgement for this domain, and so were categorised as 'No information'. In most cases this was because psychoactive treatments used by participants external to the study were not reported or were not reported split by exposure group.

Twenty‐five of the studies did not provide sufficient information to judge this domain for the depression outcome. We rated a further five studies at low risk of bias as they excluded people receiving psychotherapy or psychoactive drugs and did not provide a psychoactive intervention as part of the study, or they adjusted for any between‐group imbalance in psychoactive treatments through their analyses. We judged three studies to be at moderate risk of bias due to deviations from the 'intervention', as some of the participants received psychoactive interventions that were likely to be minimally associated with quitting smoking (Bock 2012; Dulger 2019), or the analysis did not appropriately account for relapse (Covey 2015). We rated one study at critical risk as some of the participants received behavioural activation therapy as part of the study, and this intervention increased quit rates (Becoña 2017).

For the mixed anxiety and depression outcome, five studies did not provide sufficient information to judge whether there was bias due to deviations from the 'intervention', and so we categorised them as 'No information'. We rated one study at low risk, as psychoactive treatments were not offered as part of the study and participants likely to need psychoactive treatment were excluded from the study (Carroll 2019). We deemed another two studies to be at moderate risk as some of the study participants received bupropion treatment and this was not adjusted for in the analyses (Cinciripini 2013; Leventhal 2014).

Bias due to missing data

For the anxiety outcome, we judged eight of the 15 studies to be at low risk of bias due to missing data, as outcome data was available for more than 70% of recruited participants, and participants were not excluded from the analysis due to missing smoking status or outcome data. We judged four of the studies to be at moderate risk of bias because more than 30% of participants were excluded from the analysis or participants were excluded from the analysis due to a lack of smoking cessation data, or both (Hammett 2019; Martínez‐González 2018; Schnoll 2016; Solomon 2006). We judged two studies to be at serious risk for this domain, as there was some evidence that the reasons for missing data may have differed between exposure groups (Farris 2015; Rocha 2017). The remaining study did not have enough information about missing data to make an informed judgement, and so was categorised as 'No information'.

For the depression outcome, we rated 17 studies to be at low risk, eight studies at moderate risk and four studies at serious risk for the same reasons as described above for the anxiety outcome. In addition, we deemed one study to be at critical risk of bias due to missing data, as less than 70% of the participants were included in the analysis of final follow‐up data and the proportions of missing data varied substantially by smoking status (Lee 2019). Another four studies did not provide enough information on smoking status to answer the signalling questions and assess bias due to missing data, and so were categorised as 'No information'.

For the mixed anxiety and depression outcome we rated two studies at low risk of bias, three studies at moderate risk, and three studies at serious risk for the reasons described for the anxiety outcome above. Two studies did not provide enough information to make a judgement, and so were categorised as 'No information' for this domain.

Bias in measurement of outcomes

We judged all studies across all three primary outcomes to be at low risk of bias for this domain. Bias is likely to be minimised as most studies did not set out to assess the impact of smoking cessation on mental health as a primary outcome, and participants and outcome assessors would not have known the hypothesis of this review. In addition, participants would have had to remember how they responded to questionnaires at baseline in order to provide a biased response to the follow‐up assessment, and the likelihood that there would be any systematic differences or errors in outcome assessment dependent on smoking status is unlikely.

Bias in selection of the reported result

We deemed most studies to be at low risk of bias across all of the primary outcomes for this domain. There was little evidence that the effect estimates were likely to be elected on the basis of results from multiple outcome measurements, multiple analyses of the association in question, or different subgroups. However, there were some exceptions to this. For the anxiety outcome we rated one of the included studies at serious risk of bias (Farris 2015), because although the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS) scale was used, which measures both anxiety and depression (subscales), the study only reported on anxious arousal at particular time points. For the depression outcome we judged a further two studies to be at serious risk of bias in selection of the reported result and one study was judged to be at critical risk. Becoña 2017 and Dulger 2019 both showed evidence of multiple tests of depression outcomes without reporting on all of these, and Berlin 2010 did the same, with further evidence that results appeared more likely to be reported if they showed a significant effect. Finally, we judged one of the studies measuring mixed anxiety and depression to be at serious risk of bias, as data from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES‐D) were not fully reported; results were reported for the unadjusted but not for the adjusted models (Cinciripini 2013).

Overall risk of bias assessment

As all studies were deemed to be at serious risk of bias due to confounding, we rated all included studies that contributed to the primary analyses at least at serious risk of bias overall. Although we rated most studies at serious risk, we judged a small number of studies to be at critical risk. All three studies contributed to the depression outcome (Becoña 2017; Berlin 2010; Lee 2019).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Anxiety

Fifteen studies reported sufficient continuous data to calculate the pooled SMD for change in anxiety symptoms from baseline to follow‐up. Data from 798 people who quit smoking and 2343 people who continued smoking provided evidence that quitting smoking was associated with a decrease in anxiety symptoms from baseline to final follow‐up compared with continuing to smoke (SMD −0.28, 95% CI −0.43 to −0.13; 3141 participants; Analysis 1.1; Figure 4). However, we detected substantial statistical heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 69%).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Change in anxiety, Outcome 1: Main continuous data analysis

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Main analysis: Difference in change (from baseline to longest follow‐up) between people who quit and people who continued smoking, outcome: 1.1 Primary outcome: Anxiety.

We carried out sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of this main effect. Removal of the three studies that did not biochemically confirm abstinence, the 10 studies that did not use a continuous measure of smoking abstinence, and the three studies where there was evidence that participants were receiving an evidence‐based psychoactive or psychotherapeutic component as part of an intervention did not account for the statistical heterogeneity or meaningfully change the estimate, such that it would change interpretation (Analysis 1.2; Analysis 1.3; Analysis 1.4). All studies included in this analysis (Analysis 1.1) analysed the same number of participants at baseline and at follow‐up, and all were judged to be at serious risk of bias; it was therefore not necessary to carry out our planned sensitivity analyses removing the studies at critical risk of bias and those that analysed a different number of participants at baseline compared to follow‐up.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Change in anxiety, Outcome 2: Sensitivity analysis: no biochemical validation

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Change in anxiety, Outcome 3: Sensitivity analysis: point prevalence or no abstinence definition

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Change in anxiety, Outcome 4: Sensitivity analysis: psychoactive/psychological treatment used

We examined whether we were able to account for the statistical heterogeneity through subgroup analyses. Five studies that measured this outcome continuously enrolled people with a chronic physical condition, five studies enrolled people from the unselected population, one study enrolled post‐surgical participants, one study enrolled pregnant women and three studies enrolled people with psychiatric conditions. There was no evidence that the effect size differed across these different clinical populations (I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.5). Looking further at participant characteristics, 10 studies selected participants because they were motivated to quit smoking, and five studies did not select participants based on their motivation to quit. Again, there was no evidence of subgroup differences between these groups (I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.6). We also conducted subgroup analyses exploring methodological issues. Six studies presented adjusted effect estimates and 11 studies presented unadjusted effect estimates. However, there was no evidence that effect estimates when controlled for confounding differed from those calculated without adjustment (I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.7). One study provided both an adjusted and an unadjusted estimate (McDermott 2013), and they were very similar (Table 2). We also split studies according to whether they were longitudinal cohort or non‐randomised intervention studies, a randomised experiment comparing people allocated to quit or to continue smoking (only one study was categorised as the latter; Dawkins 2009), or a secondary observational analysis of an RCT. There was no evidence of subgroup differences between these differing study designs (I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.8). Eleven studies assessed anxiety at final follow‐up between six weeks and six months, and four studies measured final follow‐up at more than six months. There was no evidence for subgroup differences based on length of follow‐up (I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.9). Finally, nine studies reported that their original main aim was to report on the change in anxiety (classed as a primary outcome), and thus the decision to publish and the likelihood of successful publication may have been contingent on the strength or significance of this finding. The main aim of the other six studies was to report on other outcomes, meaning the changes in anxiety were secondary outcomes. There was no evidence for differences in the result of the studies based on the studies' aims (I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.10).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Change in anxiety, Outcome 5: Subgroups: comparing clinical populations

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Change in anxiety, Outcome 6: Subgroups: motivation to quit

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Change in anxiety, Outcome 7: Subgroups: comparing adjusted & unadjusted estimates

1. Comparison between unadjusted and adjusted SMDs and 95% CIs for the association between smoking cessation compared to continued smoking and mental health from studies in which both were presented.

| Study | Outcome | Covariates adjusted for | Unadjusted SMD (95% CI) | Adjusted SMD (95% CI) |

| Becoña 2017 | Depression | Treatment group allocation, age, sex, baseline marital status, baseline education level, baseline working status, baseline FTND score, baseline number of years smoking | −1.61 (−2.34 to −0.88) |

−1.62 (−2.36 to −0.88) |

| Blalock 2008 | Depression | Baseline carbon monoxide expiration, baseline nicotine withdrawal score, treatment group allocation | −0.54 (−1.42 to 0.34) |

−0.58 (−1.01 to −0.15) |

| McDermott 2013 | Anxiety | Baseline STAI score, age, baseline nicotine dependence level, baseline cigarette consumption, and treatment group allocation | −0.62 (−0.88 to −0.36) |

−0.74 (−1.00 to −0.48) |

| Taylor 2015 | Psychological quality of life | Baseline FTND score, treatment group allocation, age started smoking, baseline report of calming effects from smoking, baseline report of unpleasant symptoms from smoking, baseline length of time to last cessation attempt, baseline experience from last cigarette, baseline longest period without smoking, baseline SF‐36 mental health score | 1.37 (0.41 to 2.33) |

1.13 (0.13 to 2.13) |

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Change in anxiety, Outcome 8: Subgroups: comparing study designs

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Change in anxiety, Outcome 9: Subgroups: length of longest follow‐up

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Change in anxiety, Outcome 10: Subgroups: primary versus secondary outcome

Two studies (Levy 2018; Shahab 2014) reported sufficient data to calculate the odds ratios for the association between abstinence and the cumulative incidence of anxiety at follow‐up. We pooled data from 165 people who quit, and 2128 people who continued smoking, which suggested that quitting smoking was associated with a reduced incidence of anxiety at final follow‐up compared with continuing to smoke (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.34 to 1.12; 2293 participants; I2 = 46%; Analysis 1.11). However, there was imprecision, with CIs incorporating the potential for both a reduced and an increased incidence of anxiety.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Change in anxiety, Outcome 11: New incidence of anxiety

We were unable to include eight studies reporting change in anxiety symptoms in our meta‐analysis and summarised them narratively (see Supplemental file 6). These studies included a total of 7613 participants. Four studies reported an improvement in anxiety symptoms in people who quit that was greater than any change which occurred in the people who continued smoking. In four studies it was not possible to discern the direction of effect.

Depression

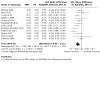

Thirty‐four studies reported sufficient data to calculate the pooled SMD for change in depression symptoms from baseline to follow‐up. We pooled data from 1863 people who quit, and 5293 people who continued smoking, which resulted in evidence that quitting smoking was associated with a decrease in depression symptoms from baseline to final follow‐up when compared to continuing to smoke (SMD −0.30, 95% CI −0.39 to −0.21; 7156 participants; Analysis 2.1; Figure 5). There was substantial statistical heterogeneity detected between studies (I2 = 69%).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Change in depression, Outcome 1: Main continuous data analysis

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 Change in depression, outcome: 2.1 Main continuous data analysis.

Our sensitivity analyses removing the two studies judged to be at critical risk of bias (as opposed to serious risk), removing the eight studies that did not biochemically confirm abstinence, removing the 22 studies that did not measure smoking cessation using continuous abstinence measures, removing the 13 studies that included participants who were in receipt of an evidence‐based psychoactive or psychotherapeutic treatment, and removing the five studies that reported mean depression scores at baseline on more people than were present at follow‐up did not result in any meaningful change in the pooled effect estimates nor diminish heterogeneity substantially (Analysis 2.2; Analysis 2.3; Analysis 2.4; Analysis 2.5; Analysis 2.6).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Change in depression, Outcome 2: Sensitivity analysis: risk of bias

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Change in depression, Outcome 3: Sensitivity analysis: no biochemical validation

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Change in depression, Outcome 4: Sensitivity analysis: point prevalence or no abstinence definition

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Change in depression, Outcome 5: Sensitivity analysis: psychoactive/psychological treatment used

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Change in depression, Outcome 6: Sensitivity analysis: differing Ns analysed

We assessed whether there was evidence that the strength of association differed based on clinical context (people with a chronic physical condition; post‐surgical participants; pregnant women; people with psychiatric conditions; the unselected population). There was weak evidence that the effect size differed across these different clinical populations (I2 = 58.5%). However, in all cases, point estimates suggested that quitters experienced a decrease in depression symptoms. For people with psychiatric conditions, pregnant women and post‐surgical participants the estimates were smaller, and for the latter two groups these were also imprecise, suggesting the possibility of either a decrease, no change, or an increase in depression symptoms associated with successfully quitting smoking (Analysis 2.7). We also investigated whether effect estimates differed by the motivation of participants to quit smoking. Twenty‐five studies selected participants because they were motivated to quit smoking, whereas nine studies did not select participants based on motivation to quit. There was no clear evidence of meaningful subgroup differences (I2 = 27.9%; Analysis 2.8).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Change in depression, Outcome 7: Subgroups: comparing clinical populations

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Change in depression, Outcome 8: Subgroups: motivation to quit

Ten studies presented adjusted effect estimates and 24 studies presented unadjusted effect estimates. A subgroup analysis provided no clear evidence that effect estimates differed between studies that had and had not adjusted for confounders (I2 = 0%; Analysis 2.9). Two of these studies (Becoña 2017; Blalock 2008) provided both adjusted and unadjusted estimates of the effects of smoking cessation on depression, and the within‐study comparisons of effects also indicated that adjustment did not result in any meaningful difference in the results (Table 2).

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Change in depression, Outcome 9: Subgroups: comparing adjusted & unadjusted estimates

We also found no evidence that effect estimates varied based on study design (longitudinal cohort, non‐randomised intervention study, randomised experimental study, or secondary analyses of RCTs; I2 = 5.4%; Analysis 2.10), length of final follow‐up (between six weeks and six months versus greater than six months; I2 = 0%; Analysis 2.11), or the main aim of the study (to report on change in depression versus to report on other outcomes with depression as a secondary outcome; I2 = 0%; Analysis 2.12).

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Change in depression, Outcome 10: Subgroups: comparing study designs

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Change in depression, Outcome 11: Subgroups: length of longest follow‐up

2.12. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Change in depression, Outcome 12: Subgroups: primary versus secondary outcome

Seven additional included studies reported data on the incidence of depression between baseline and follow‐up in sufficient detail to calculate the pooled odds ratio. We analysed data from 19,521 people who quit, and 89,221 people who continued smoking. The result was subject to substantial unexplained statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 87%; Analysis 2.13), and we therefore deemed it inappropriate to present the pooled result. Two studies favoured a beneficial effect of smoking cessation on incidence of depression, two a harmful effect, and three were close to the null.

2.13. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Change in depression, Outcome 13: New incidence of depression

We were unable to include 16 studies with 15,285 participants reporting change in depression symptoms in our meta‐analysis, so we summarised them narratively (see Supplemental file 7). Six studies reported a larger improvement in depression symptoms in people who quit compared to people who continued to smoke, in four studies the association was equivocal, in one study there was an improvement in people who continued to smoke compared with people who quit, and in the remaining five studies it was not possible to discern the direction of effect.

Mixed anxiety and depression

Eight studies reported sufficient data to calculate the pooled SMD for the change in mixed anxiety and depression measures between baseline and follow‐up. We analysed data from 793 people who quit and 2036 people who continued smoking. Results suggested that quitting smoking was associated with a decrease in mixed anxiety and depression symptoms compared with continued smoking (SMD −0.31, 95% CI −0.40 to −0.22; 2829 participants; I2 = 0%; Analysis 3.1). None of our sensitivity analyses investigating the effects of removing studies that did not biochemically validate abstinence, that measured point prevalence abstinence only, that included participants who were receiving psychoactive or psychological treatment, or that analysed different numbers of participants at baseline and follow‐up, found any meaningful difference in the effect estimates (Analysis 3.2; Analysis 3.3; Analysis 3.4; Analysis 3.5)

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Change in mixed anxiety and depression, Outcome 1: Main continuous data analysis

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Change in mixed anxiety and depression, Outcome 2: Sensitivity analysis: no biochemical validation

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Change in mixed anxiety and depression, Outcome 3: Sensitivity analysis: point prevalence or no abstinence definition

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Change in mixed anxiety and depression, Outcome 4: Sensitivity analysis: psychoactive/psychological treatment used

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Change in mixed anxiety and depression, Outcome 5: Sensitivity analysis: differing Ns analysed

We also carried out subgroup analyses to examine whether prespecified factors contributed to the variation in effects across studies. There was no evidence of subgroup differences by population type (Analysis 3.6), or between people motivated to quit smoking versus participants not selected on motivation (Analysis 3.7). A further three subgroup analyses investigated methodological factors; there was no evidence of subgroup differences when studies were split based on study type (Analysis 3.8), maximum length of follow‐up (Analysis 3.9), or whether mixed anxiety and depression was investigated as a primary outcome or a secondary outcome (Analysis 3.10).

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Change in mixed anxiety and depression, Outcome 6: Subgroups: comparing clinical populations

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Change in mixed anxiety and depression, Outcome 7: Subgroups: motivation to quit

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Change in mixed anxiety and depression, Outcome 8: Subgroups: comparing study designs

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Change in mixed anxiety and depression, Outcome 9: Subgroups: length of longest follow‐up

3.10. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Change in mixed anxiety and depression, Outcome 10: Subgroups: primary versus secondary outcome

Three additional studies (Cavazos‐Rehg 2014; Chen 2015; Giordano 2011) reported sufficient data to calculate the odds ratio for the association between smoking cessation and incidence of mixed anxiety and depression at follow‐up. These studies included data from 1752 people who quit and 6933 people who continued smoking. There was evidence that quitting smoking was associated with a reduced incidence of mixed anxiety and depression at final follow‐up when compared to continuing to smoke (OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.86; 8685 participants; Analysis 3.11); there was moderate statistical heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 57%).

3.11. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Change in mixed anxiety and depression, Outcome 11: New incidence of mixed anxiety and depression

We were unable to include two studies with 130 participants reporting change in mixed anxiety and depression symptoms in our meta‐analysis, so we summarised these narratively (see Supplemental file 8). For both studies, the association was equivocal, with no evidence of a difference in mixed anxiety and depression symptoms between quitters and continuing smokers.

Stress

Four studies reported sufficient data to calculate the SMD for change in stress from baseline to follow‐up, pooling data from 651 people who quit, and 1141 people who continued smoking. Evidence suggests that quitting smoking was associated with decreased stress symptoms from baseline to final follow‐up when compared with continuing to smoke (SMD −0.19, 95% CI −0.34 to −0.04; 1792 participants; Analysis 4.1). Moderate statistical heterogeneity was detected (I2 = 50%).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Change in stress, Outcome 1: Main continuous data analysis

We carried out the following sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of the result: removal of two studies that did not biochemically confirm abstinence (Analysis 4.2); removal of two studies that did not measure abstinence using a continuous measure (Analysis 4.3), removal of one study that based baseline analyses on larger numbers than follow‐up analyses (Analysis 4.4). None of these analyses provided evidence for any meaningful change in the effect estimates. No studies recruited participants that were clearly receiving psychoactive or psychotherapeutic treatment. One study included in this analysis (Taylor 2015) provided both an adjusted and unadjusted estimate of the effect of smoking cessation on stress. Adjustment did not meaningfully change the effect estimate (Table 2).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Change in stress, Outcome 2: Sensitivity analysis: no biochemical validation

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Change in stress, Outcome 3: Sensitivity analysis: point prevalence or no abstinence definition

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Change in stress, Outcome 4: Sensitivity analysis: differing Ns analysed

Subgroup analyses examined whether prespecified factors contributed to the variation in effects across studies. There was no evidence of subgroup differences between the association in people with a chronic physical condition and the general population (Analysis 4.5), or between people motivated to quit smoking and studies that did not select participants based on their motivation (Analysis 4.6). A further two subgroup analyses investigated methodological factors; there was no evidence of subgroup differences when studies were split based on study type (longitudinal cohort studies or non‐randomised intervention studies versus secondary analyses of RCTs; Analysis 4.7) or based on the maximum length of follow‐up (between six weeks and six months follow‐up versus more than six months follow‐up; Analysis 4.8). The primary aim of all four studies that measured stress was to report on the change in stress symptoms, so the prespecified subgroup analysis comparing stress as a primary versus secondary outcome was not appropriate.

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Change in stress, Outcome 5: Subgroups: comparing clinical populations

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Change in stress, Outcome 6: Subgroups: motivation to quit

4.7. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Change in stress, Outcome 7: Subgroups: comparing study designs

4.8. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Change in stress, Outcome 8: Subgroups: length of longest follow‐up

We were unable to include four studies with 1554 participants, reporting change in stress in our meta‐analysis, so we summarise them narratively (see Supplemental file 9). Three studies reported a larger improvement in stress in people who quit compared with people who continued smoking, and in the remaining study it was not possible to discern the direction of effect.

Positive affect

Thirteen studies reported sufficient data to calculate the SMD change in positive affect from baseline to follow‐up. We pooled data from 1965 people who quit, and 2915 people who continued smoking. Quitting smoking was associated with an increase in positive affect from baseline to final follow‐up when compared with continuing to smoke (SMD 0.22, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.33; 4880 participants; Analysis 5.1; Figure 6). There was substantial statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 75%), but all point estimates favoured quitting smoking, apart from one, which was only slightly in favour of continuing to smoke.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Change in positive affect, Outcome 1: Main continuous data analysis

6.

Funnel plot of comparison: 5 Change in positive affect, outcome: 5.1 Main continuous data analysis.