Abstract

Introduction

We report on service user participation in a population-based data linkage study designed to analyse the daily, weekly and yearly cycles of births in England and Wales, the outcomes for women and babies, and their implications for the NHS. Public Involvement and Engagement (PI&E) has a long history in maternity services, though PI&E in maternity data linkage studies is new in the United Kingdom. We have used the GRIPP2 short form, a tool designed for reporting public involvement in research.

Objectives

We aimed to involve and engage a wide range of maternity service users and their representatives to ensure that our use of patient-identifiable routinely collected maternity and birth records was acceptable and that our research analyses using linked data were relevant to their expressed safety and quality of care needs.

Methods

A three-tiered approach to PI&E was used. Having both PI&E co-investigators and PI&E members of the Study Advisory Group ensured service user involvement was part of the strategic development of the project. A larger constituency of maternity service users from England and Wales was engaged through four regional workshops.

Results

Two co-investigators with experience of PI&E in maternity research were involved as service user researchers from design stage to dissemination. Four PI&E study advisors contributed service user perspectives. Engagement workshops attracted around 100 attendees, recruited largely from Maternity Services Liaison Committees in England and Wales, and a community engagement group. They supported the use of patient-identifiable data, believing the study had potential to improve safety and quality of maternity services. They contributed their experiences and concerns which will assist with interpretation of the analyses.

Conclusion

Use of PI&E ‘knowledge intermediaries’ successfully bridged the gap between data intensive research and lived experience, but more inclusivity in involvement and engagement is required. Respecting the concerns and questions of service users provides social legitimacy and a relevance framework for researchers carrying out analyses.

Keywords: public involvement and engagement, data linkage, births, maternity care, maternity voices partnerships, maternity services liaison committees, knowledge intermediaries, service user researchers

Introduction

The Birth Timing study is a population-based retrospective birth cohort data linkage study designed to analyse the daily, weekly and yearly cycles of births in England and Wales, and their implications for the NHS [1]. It has involved linking identifiable routinely collected data from several data sets for births from 1st January 2005 to 31st December 2014. The data are identifiable in the sense that they include identifiers used for linkage. They were processed in a secure environment and at no stage were researchers able or permitted to identify individuals in files of seven million births.

England and Wales have common systems for civil registration of birth and notification of births by midwives and these are now linked routinely by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) following piloting in an earlier project [2]. The two nations have different systems for recording data about maternity care so the linked registration and notification data for births in England were further linked to the Maternity Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) while data about births in Wales were linked to the Patient Episode Database for Wales and the National Community Child Health Database [1]. The linked data were stored, processed and analysed in a secure environment provided by the ONS and were analysed to describe the timing of births in different birth settings. Further analyses were planned by time of day, day of the week and year of birth in terms of numbers of births and mortality and morbidity outcomes [1]. The study built on previous projects which piloted the data linkage in England [3] and in Wales [4]. This paper focuses on the service user participation in the phase of the project completed in 2017. At the time of writing, research outcomes were mainly descriptive; further analyses are under way after delays caused by data access problems [1].

The study aimed to produce analyses to inform policy makers, clinicians and commissioners on improving safety and ensuring quality 24-hour maternity and neonatal care, issues of great importance to women and families, and to investigate concerns that care might be less safe at night and at weekends than during ‘office hours’ [5]. Maternity care is required at all times of the day and night, and every day of the year. Some of the planned elements, such as ‘elective’ caesarean births and medical induction of labour, can be scheduled to particular daytime hours, but most labours begin spontaneously and many births occur at night. To make the study as accessible as possible to service users we referred to it using a two-word name, Birth Timing.

Background to public involvement and engagement in research

Definitions

The use of terminology and definitions in the literature on how researchers and the public interact varies between countries and over time. However, it is gradually becoming more consistent. ‘Involvement’ tends to be defined as people such as service users, carers and the wider public carrying out ‘shared research tasks’ such as research design, information for the public, analysis, writing up and communicating findings, alongside researchers [6]. ‘Engagement’ involves thinking about research, rather than doing research. It is a process in which researchers find ways to interact with the public, to ask people what matters to them and their communities and to share research knowledge, sometimes in imaginative ways, such as using art or social media [7, 8], with the goal of generating mutual benefit [9].

In the UK, NIHR INVOLVE defines public involvement in research as research being carried out ‘with’ or ‘by’ members of the public rather than ‘to’, ‘about’ or ‘for’ them [10] and explores ways to address equity and inclusion [11]. The term ‘knowledge intermediary’ is used for ‘people who ‘inhabit a professional space between academics and non-academics’ [12]. These are the definitions used in this paper.

There is sometimes reference to ‘service user researchers’, particularly in mental health studies [13] and disability research [14], although it seems that the term is not currently tightly defined. In the UK the phrase refers, for example, to people who ‘use psychiatric services and who also conduct research’ [15]. Service user researchers who have ‘lived experience’ can be regarded as possessing ‘insider knowledge’ and are usually keenly interested and empathetic [13]. While it has been suggested that the term is frequently used by ‘feminists, Black writers, and educationalists who have allied themselves with oppressed groups’ [14], a number of those who describe themselves this way have a doctorate and some are employed academics [13–15]. There is potentially a debate to be had as to whether it is necessary to be formally qualified or employed as a researcher to become a service user researcher. Notwithstanding this lack of clear definition, we use the term ‘service user researcher’ in this paper to describe project co-investigators with service user involvement experience.

Two further terms used in this paper relate both to service user involvement in research and in provision of health services: ‘co-production’ and ‘partnership working’. These are closely related concepts, co-production necessitates researchers or service providers collaborating actively and respectfully with citizens [16]. Similarly, partnership working implies a relationship that actively promotes mutual respect and aspires towards service users having an equal voice [17].

Historical background

Public and service user involvement in health research has been regularly documented since the 1990s, with the UK, USA, Canada and Australia contributing substantially to the literature [18, 19]. Involvement research in USA, Canada and Australia has tended to address the views and experiences of disempowered and marginalised groups, especially those from indigenous, Black and other minority ethnic communities [18, 20]. These studies have tended to be qualitative, participatory and of action research design, whereas in the UK the focus has been more health topic-based (e.g. mental health, cancer, children’s health) [18]. There is a longer history of community engagement in global health research, where there have been debates since the late 1950s about the relative merits and demerits of a top-down biomedical approach to health programmes and research compared with a broader, bottom-up approach, specifically addressing inequalities and the social determinants of health [7].

There is less in the literature about public involvement in quantitative research [18, 21] though studies show that ‘consumers’ and ‘service user advocates’ are able to contribute to and benefit from involvement in research priority setting [22] and scientific review of clinical research proposals [23, 24]. In this context, service user advocates are people with personal experience of a condition who have devoted time subsequently to developing wider knowledge and a network or ‘constituency’ [24] related to that experience. Government and professional endorsement of patient and citizen participation in research in UK, USA, Australia and Canada, and by international bodies, such as the Cochrane Collaboration [17] has led to reviews of types of public involvement activities [25], and practical strategies and guidance [11, 17] including a consensus statement on public involvement and engagement (PI&E) in data-intensive health research [26].

Public involvement – values, purpose and methods

In the UK, a recent systematic review [27], suggests that a wide diversity of values and intended purposes underpin public involvement in research [14]. The reviewers identified five categories of framework: power-focused; priority-setting; study-focused; report-focused; and partnership-focused; concluding that no single framework was appropriate for all purposes. They took a pragmatic view that, while involvement may mean very different things in different contexts, there is universal agreement that involvement is beneficial [27]. In quantitative research, where the impact of involvement is acknowledged as ‘highly context-specific’ and used to be based on the subjective reflections of the researchers and service users involved [21], addressing the absence of an impact measurement tool was seen as a priority [28]. It has subsequently been addressed through the development of involvement theory and practical reporting checklists [29]. Similar work has been undertaken in the US [30] and in Canada [31], to advance the rigour of engagement and involvement methods, reliability of reported outcomes and to facilitate future synthesis of evidence, although different terminology may be used [31]. An agreed principle of public involvement is to ensure that PI&E values and activities are woven through the whole study [26], although this can often be hampered by a lack of funding at the design stage [32]. Some institutions manage this by setting up a standing PI&E group [33], or building relationships with relevant charities or individual ‘knowledge intermediaries’ [12] to which they can turn [22, 34, 35].

Involvement and engagement in maternity care and research

There has been a long history of women being active and vocal about their maternity care [36, 37]. Childbirth educators, community organisations and women’s groups have taken a grassroots interest in maternity research, carrying out their own studies [38–40] and using academic research that helps to explain women’s experiences [41] including in evidence to the House of Commons Health Committee’s ground-breaking Inquiry into Maternity Services in 1992 [42]. This resulted in the first government maternity policy aiming for women to have choice, control and continuity of care and carer [43]. The pioneers often challenged traditional beliefs, gave voice to gender-based experiences and highlighted ways that maternity care provision can affect psychosocial and physical outcomes [41, 42, 44–47]. In the UK, national organisations such as National Childbirth Trust (NCT) and the Association for Improvements in the Maternity Services (AIMS), and special interest agencies such as Birth Companions (founded to support pregnant women and new mothers in Holloway Prison and working for women facing multiple disadvantage) have taken an active interest in research as a means of demonstrating their legitimacy and influencing change in maternity services [48–50].

Much service user involvement in maternity research has had a critical, feminist, rights-based focus. Service users and researchers have expressed the need for services to be safe for women, providing holistic care which addresses physical, social and emotional needs [51] and, as well as avoiding trauma, to positively promote wellbeing [52]. Two notable service user-led studies, from Canada and the USA, have focused on women’s autonomy and role in decision making during maternity care [53] and focusing on the need to measure and address inequity, mistreatment and abuse during childbirth in different places of birth, with different care providers and for different socioeconomic and ethnic groups [54].

This kind of emancipatory or rights-focused [55] approach is sometimes referred to as a ‘democratic’ perspective and distinguished from a ‘consumerist’ perspective, which does not focus primarily on ‘oppression’ or on differences in status and power [14], but emphasises instead that ‘patient experience’ is an essential element of high quality healthcare [56]. Both perspectives have contributed towards bringing citizen participation into the mainstream of healthcare and research [14]. As part of this development, professional public involvement roles have emerged in the UK and guidance has proliferated on obtaining patient views and on ‘co-production’ [57] as a method of partnership working with an emphasis on supporting patients’ rights to be involved in decisions about their own care [58]. In maternity services in the UK, Maternity Services Liaison Committees were one of the early prototype models of public involvement. These have now evolved, in England, into service user-led Maternity Voices Partnerships, endorsed by government and seen as a mechanism for delivering partnership working between commissioners, service providers and service users [59].

Public engagement and involvement in data linkage research

Many data linkage studies on important public health topics have not involved partnership working with service users or the public [60–62], but this is gradually being addressed. In Wales [63] and in Scotland [64] involvement panels and discussion forums have been created to explore the views of people of different ethnicity, age and gender in whole population studies and, in London, The Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre created a patient and public involvement group to discuss use of mental health data with service users and carers [33]. However, to the best of our knowledge, PI&E in maternity data linkage research is new. The Centre for the Improvement of Population Health through E-records Research (CIPHER) in Wales, one of four such data linkage research centres of excellence in the UK, has described its development. First, the focus was on setting up the technical infrastructure, creating the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage (SAIL) Databank to connect and hold multiple datasets. Three years on, a 10-member ‘consumer panel’ was established with representation from many counties and health conditions, both genders and wide community involvement [63]. The Scottish Health and Ethnicity Linkage study set up ‘public panels’, involving people of 10 different ethnic backgrounds among 19 participants [64]. These studies suggest that there is considerable positive potential for PI&E in data linkage research. Engagement activities can perform a bridging role: connecting data analysts and the people whose data are being used; connecting the public with published evidence on public services and raising public awareness of the implications of research for citizens [26].

There are, however, complex ethical issues inherent in the use of public health data and it is important not to gloss over the conflicts and challenges in carrying out data linkage research and attempting to work with the public as equals [65]. On one hand, it can be argued that greater public awareness of the use of routinely collected health data would be beneficial as the ethical issues involved affect everyone [33], but it cannot be guaranteed that the public, in gaining awareness, will feel confident with data linkage research [65]. There has been public disquiet about issues of privacy, consent and security, with concerns that data could be exploited for commercial purposes [65]. Thus, social and moral legitimacy to process data is as important as the legal authority [66]. For example, public confidence about the use of NHS data in England was undermined by NHS England’s proposals for its ‘care.data’ system, with wider concerns about the possible sale of personally identifiable data to private companies [65,66]. This proposal provoked a public outcry [67] which resulted in NHS Digital, the organisation with responsibility for health data in England, restricting access to data for publicly funded research including the Birth Timing study. This sensitivity illustrates that the concept of a social licence to use personal health data appropriately is vital. Public involvement in data-intensive health research when led respectfully with commitment to partnership, and managed well, can be an important way of preventing public distrust [26, 68].

Public involvement and engagement in the Birth Timing study

The service user involvement in the Birth Timing study was planned in 2012 when PI&E in data linkage studies was in its infancy. The planned work was informed by beliefs that service users have a democratic right to influence research design; that research should be grounded in practical experience to ensure relevance; and that accountability to service users is important [69]. The PI&E was service user-led.

We have used the ‘GRIPP2 short form checklist tool’ for reporting [29]. The original GRIPP (Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public) checklist had been designed for reporting studies where involvement was the primary purpose of the study. It was revised, based on updated systematic review evidence and a three-round Delphi survey, to produce a checklist tool for reporting studies when involvement is a secondary purpose. For us, this included reporting on the aim of involvement and engagement in the study; describing the methods used; reporting the results of PI&E in the study, including both positive and negative outcomes; commenting on the extent to which PI&E influenced the study overall, describing positive and negative effects; and commenting critically on the study, reflecting on the things that went well and those that did not, so others can learn from the experience [29].

The aim of PI&E in the study was to involve and engage maternity services users and their representatives to ensure that our use of routinely collected maternity and birth records was acceptable and that our research analyses using linked data were relevant to the safety and quality of care needs they identified, particularly in relation to 24-hour care.

Methods

A three-tiered approach to PI&E was used. The first two tiers sought to ensure service user involvement was part of the strategic development of the project, while the third used an engagement approach to include a much larger constituency of users and community volunteers:

Experienced service user representatives collaborated on the project as co-investigators (the ‘PI&E co-investigators’). Their role was regarded as that of ‘service user researchers’ [1].

Additional maternity service user representatives were recruited to the Study Advisory Group.

Events were held with service user members of Maternity Services Liaison Committees (MSLCs). All were current or previous users of maternity services who worked with local antenatal and postnatal parents’ support groups, some as antenatal teachers, breastfeeding counsellors or doulas (trained birth companions who provide support) and were part of these multidisciplinary health forums.

MSLCs were first established in the UK in the 1980s to provide a multidisciplinary forum for professionals and service users in maternity services. Terms of reference stated that the chair should be a ‘lay person’ and one third of the membership should be parents or non-NHS professionals [70]. In England these are now called Maternity Voices Partnerships. MSLCs continue in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

While no formal framework was used, the PI&E plan drew on the experience of the PI&E co-investigators in using engagement and communication methodologies taught and used in the NCT charity, which include active listening, facilitation, small group work and gathering feedback [71–74], plus their extensive lived experience of expressing user voices and promoting PI&E in research [22, 34, 75–77].

Involvement

The PI&E co-investigators were recruited at the design stage, based on established links between them, the project’s Lead Researcher (AM) and the established childbirth organisations NCT and BirthChoiceUK [34, 78, 79]. They were recruited as partners throughout the project, to contribute to drafting the funding application, to lead the PI&E and to help direct the focus of the research. They are the first two authors of this paper.

The multidisciplinary Study Advisory Group advised the co-investigators on the overall conduct of the study, the study questions, analysis, outputs and dissemination of findings. Maternity service user members of the advisory group were recruited via an NCT network. This gave us access to people with valuable service user experience in NHS settings as members or chairs of MSLCs [80] or labour ward forums and in lay groups supporting women.

Applicants gave details of their location and local maternity service, their experience on an MSLC or other relevant body, their interest in this project and what they could bring to the advisory group, plus their availability and support needs. They were given an outline of the purpose and method of the study, the advisory group’s role and the proposed meeting timetable. The full research protocol was available on request. Standard-class travel and childcare expenses were offered. Being part of the advisory group was presented as a reciprocal opportunity with benefits for both our study and the applicants.

Engagement

The third tier of PI&E involved a larger group of service user representatives over four separate events. For three of these, MSLC members were invited to venues, easily accessible by public transport. Lunch was provided and travel bursaries offered.

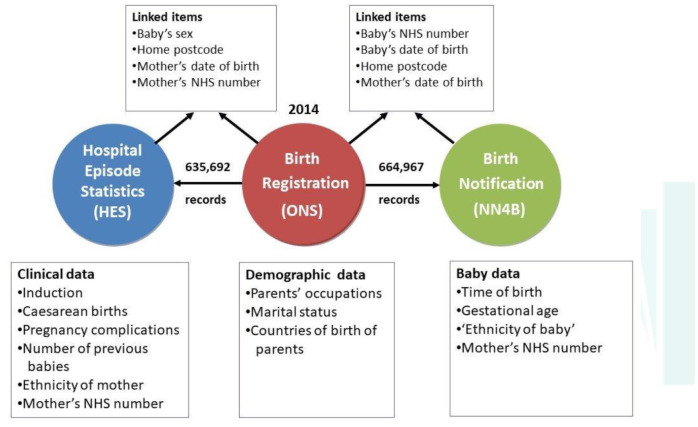

These events included a Birth Timing workshop with a short PowerPoint presentation on the study with a description of the data linkage (for example, Figure 1). This was followed by discussion in small groups on a series of questions and a plenary session to share some of the key points arising. Participants in each group were given flipchart paper and asked to nominate a note taker to record key points. MN circulated between groups and asked for clarity where points were ambiguous. MN collected and transcribed the sheets. From the outset, there was a plan to change the focus of the workshops as the study developed, starting with issues of data privacy and consent, moving on to women’s experiences of maternity care during the day, at night and weekends, and then to their views on proposed data analyses and results. At all stages there were opportunities for them to express and explore their own priority research questions [1].

Figure 1:

Overview of datasets for England used in the study, showing types of data held within each dataset and how they were linked

To provide a reciprocal benefit for attendees, three of the workshops were planned as part of NCT Information and Support days where attendees received training on running MSLCs, advocacy, using social media, policy updates and education on research methodology.

The fourth engagement event, with an ‘inner city’ group, was planned through City, University of London’s Maternal and Child Health Research parents’ advisory group. The group, which meets regularly, usually attracts 4-8 parents who are paid an honorarium. The intention was to engage women from Black, Asian and other ethnic communities and current service users without any NCT affiliation. The session included the aims and methods of the Birth Timing research with discussion framed around questions of data privacy and consent, the women’s experiences of maternity care and any concerns.

Dissemination

We planned to make the results accessible to the public by providing a summary of the research and links to the research outputs on the BirthChoiceUK website. NCT planned to disseminate the findings to parent representatives on MSLCs and publish for parents and NCT practitioners. At that time, NCT had around 100,000 members. Both NCT and BirthChoiceUK planned to use their social media presence on Facebook and Twitter to alert their followers to research outputs.

Results

Involvement

PI&E Co-investigators

The PI&E co-investigators had a range of skills which were distinct from the other members of the data linkage research team. Both were active in maternity networks and had considerable ‘user voice’ experience in addition to having used maternity services. They had trained in group facilitation and had experience in conveying maternity research to the public. MN, who was Head of Research at NCT, had left school at 16 and had two babies before the age of 20, before returning to education. She gained qualifications in sociology and health services research. Having led NCT research [81, 82] and developed evidence-based information, she was experienced in communicating this to women and listening to their perceptions and concerns. MS was employed on the study because of both her research and health advocacy experience. She had previously gained a PhD in science and had a diploma in antenatal teaching. She was co-creator of BirthChoiceUK, a successful and innovative public-facing website. Her expertise was in working with routine maternity data and presenting it to women in an accessible format to assist with birth choices.

Furthermore, a third co-investigator, a father of three, had a history of voluntary childbirth activism using his data processing and analysis skills. He was the second co-creator of the BirthChoiceUK website [83]. Thus, he was knowledgeable about maternity services from a male perspective.

In terms of impact, this range of skills and knowledge was useful at all stages of the project. Working as service user researchers, the PI&E co-investigators coordinated the engagement workshops where they delivered service user-focused presentations and facilitated interaction and discussion, collating responses and feedback. They reported back from the workshops to the project team meetings and to the advisory group. MS was a full member of the project team and attended project meetings throughout. Both PI&E co-investigators assisted in the design of the main research and contributed to data analysis and interpretation. Together they wrote the section on health policy context in the introduction for the final report as well as the chapter and appendix on PI&E, and were fully involved in reviewing and commenting on the whole report [1]. They had input into all articles and poster presentations resulting from the project and were particularly involved in a paper on onset of labour and mode of birth [84]. MS contributed the initial ideas for analysis of timing in relation to mode of birth, based on her long experience of analysing maternity data from the perspective of pregnant women, and MN contributed to the writing of the paper, using the idea of intrapartum (labour and birth) ‘care pathways’ as the basis for describing the analysis [84].

The researchers said they felt it was valuable to have the PI&E co-investigators as colleagues on the team. Comments included: ‘(We value) your maternity services knowledge and connections with childbearing women’ and ‘you ensured that the research stayed relevant to pregnant women’.

The Study Advisory Group

Four people were recruited as public involvement members of the Study Advisory Group from different regions of England. They were a leading member of the Association for Improvements in the Maternity Services, a recent service user, a public health professional with a young family, and an NCT breastfeeding counsellor. The breadth of geographical, organisational and special interest backgrounds provided a wide range of knowledge and perspectives which contributed to the strategic development of the project. None of those applying were men or were from a Black, Asian or other ethnic community. As members of the advisory group, they sat alongside clinicians, researchers and commissioners in meetings and they all posed questions and expressed views on priorities for the research from a women-focused perspective, using their experience representing maternity service users.

In terms of impact, one service user advisor emphasised that ‘My interest in the study stems from the timings of birth discussion that links into discussions about whether the NHS is consistent across the week. It is something that does cause anxiety and studies such as this one are very valuable’. She suggested extending the engagement to include a more diverse range of voices. This reinforced the need to carry out the inner city workshop, independent of NCT. Advisors reviewed and commented on project publications, including this one, with changes made as a result. Reciprocal benefits included providing one service user advisor with ‘huge insight into the rigour and scrutiny needed for larger scale research… and a lot more confidence to scrutinise and participate in research’.

Engagement

The three MSLC engagement workshops (1-3), held over a period of two years at NCT Information and Support events in Birmingham, Wakefield and Bristol, were attended by 30-35 female participants on each occasion, totalling around 100. With funding from the Birth Timing study for the purpose of research engagement, the venue hire, refreshments, marketing and delegate liaison were managed by NCT. MN and MS, with NCT’s then Research Engagement Officer (RP), planned the events’ programmes and promoted the days using social media. There were presentations and discussions on topics including national maternity policy developments, latest MBRRACE findings [85], NICE guidance on intrapartum care for healthy women [86], and a mother’s experience of having a child with Down’s syndrome. Attendees’ interests, experiences and knowledge were widely varying. There was a focus on mutual learning and problem solving. For example, at the second event, an attendee of South Asian ethnicity shared her concern about improving services for women of colour and those who experience miscarriage. At the third event, a ‘speed dating’ session was held, during which people could pitch in advance to run a short session on a topic of their choosing. The other attendees moved from one small group ‘date’ to another, according to their interests. The Birth Timing workshops were scheduled for the afternoon, within these events.

The attendees came from urban and rural areas and included people with recent maternity experience. They all had community connections with other local parents, bringing relevant service user insights. The desire to network attracted people from many parts of England and from Wales. For example, the Wakefield event included local women and others from Blackpool, North Cumbria, Leeds, Norfolk, South London and Sussex. Women from Mid- and South Wales attended the Birmingham and Bristol events.

Workshops were also attended by the study’s Lead Researcher (AM) and some national maternity leaders, including the Chair of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) Women’s Network and the NHS England Head of Patient Experience for women, children and young people.

The inner city workshop (4) in London was attended by a small number of women from Eastern European families with young children. Unfortunately, some women cancelled due to ill-health and family commitments.

Birth Timing workshops

At workshops 1 and 4, data privacy and consent issues were addressed, to ensure social legitimacy of our use of women’s patient-identifiable maternity data and their babies’ birth records. Details were given of the ethics and other approvals for the study and the strict rules of confidentiality to which the researchers were required to adhere, including accessing sensitive NHS data in the secure environment of ONS’ Virtual Microdata Laboratory, now known as the Secure Research Service. Using small groups to increase participation, attendees discussed how comfortable they were with this use of their data. They reported back that they were happy that women’s data were used in the way planned and did not regard it a breach of confidentiality as it would not be possible to identify individuals among over five million babies. There was a widely held view amongst the participants that the research was ‘important especially if it helps improve outcomes’.

As a condition of approval for processing personally identifiable information without consent for the public good, the researchers were required to produce a poster about the study to be displayed in NHS clinics and waiting areas (See Supplementary Appendix 1). In workshop 1, attendees were asked to give feedback on a draft version. They gave ideas for improvement, including emphasising the overall size of the study, which was subsequently done, and inserting a Quick Response matrix barcode (QR code) to link to further information. Unfortunately, it was not possible to incorporate a QR code as the study did not have its own website.

To ensure that our research analyses and their interpretation were relevant and grounded in women’s experiences, workshop attendees were asked specific questions about their experiences and concerns, including their thoughts about ‘out of hours’ care, staffing levels and seniority, and their knowledge of the care received by women with more complex needs. Again, these were discussed in small groups to encourage maximum participation, with MN, RP and MS facilitating. Flipcharts were used during discussions and further notes were taken of their experiences and concerns, along with suggestions for analyses and further research (Table 1).

Table 1: Examples of maternity services concerns, benefits of ‘out of hours’ care, and b) research questions at the engagement workshops.

Key: Maternity Services Liaison Committee workshops, 1–3; Inner city workshop, 4. W/s no = Workshop number

| Table 1a) | |

|---|---|

| Maternity services – concerns | W/s no. |

| Staffing shortages: | |

| - limited choice of birth place in some areas, e.g. a midwifery unit closed / home birth suspended to move limited number of midwives to the obstetric unit | 1, 2, 4 |

| - low staffing levels, especially in the evenings, weekend, during the night / non-urgent cases have to wait | 1, 2, 4 |

| - quality of staffing at night: lack of specialist care or senior staff / staff tiredness at night | 4 |

| - special care baby unit nurses | 4 |

| Postnatal care: | |

| - lack of out of hours breastfeeding support | 1, 4 |

| - midwife shortages on postnatal ward | 1, 4 |

| - midwives so busy, women avoiding asking for help | 1, 2 |

| - partners being sent home at night | 1 |

| Black, Asian, other ethnic and migrant women: | |

| - more vulnerable when staffing is stretched | 2 |

| - lack of interpreters out of hours | 2 |

| - women with English as a second language are more vulnerable in labour / unfamiliar with some birth words | 4 |

| ‘Out of hours’ care – positives | |

| - The labour ward is quieter and more conducive to undisturbed labour and birth / more likely to get one-to-one care. | 1 |

| Table 1b) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Birth Timing analysis or other research needed | W/s no. | Researcher response |

| Are neonatal readmission rates / number of weeks of breastfeeding associated with time of birth (and possible variations in staff support for early breastfeeding)? | 1, 4 | Researchers will look at readmission rates, but do not have data on breastfeeding or staffing issues. |

| Is time of birth associated with poorer outcomes, e.g. emergency Caesareans at night? | 3, 4 | The next stage of the analysis will look at this. |

| Do staffing shortages affect outcomes and what are the right staffing models for best birth outcomes, in the light of so many births occurring during the evening and at night? | 3, 4 | Researchers raised this question in the final report but cannot answer questions on staffing using routinely collected data. |

| Do women from Black, Asian and other ethnic communities have different outcomes out of hours? | 2, 4 | The planned analysis will look at any ethnic differences in outcomes. |

| Are inductions of labour started at the best time of day? | 3 | The time of inductions is not recorded, however other research has considered this question [87]. |

| If light affects timing of spontaneous labour and birth in mammals, are there seasonal variations in the daytime/night-time patterns of spontaneous births? | 3 | Analyses will be done by season. |

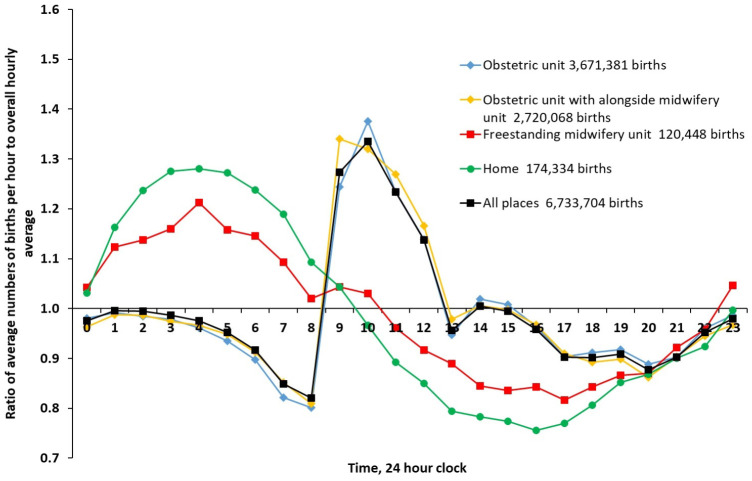

In later workshops, presentations included preliminary results about the daily, weekly and yearly patterns of birth. The women were intrigued by the patterns of births shown to them visually in the form of graphs and charts. One such graph showed patterns of birth in three out of four different birth settings known to be associated with different levels of intervention for ‘healthy women’ throughout the 24-hour cycle (Figure 2) [86]. These included hospital obstetric units, freestanding midwifery units and home. This generated discussion about the impact on the physiology and management of labour of planned settings for birth. It also created awareness of the difficulties that researchers had in producing the analyses for all four birth settings, because alongside midwifery units, the fourth birth setting [86], are not adequately differentiated from hospital obstetric units in the underlying data. This is important because intervention rates differ between freestanding and alongside midwifery units [86]. Women, policy makers and service providers need further information to inform their planning and decision-making in the context that, despite robust evidence of benefits, until quite recently in England ‘planned birth outside an obstetric unit remain(ed) uncommon’ [34], and access to freestanding midwifery units continues to fall.

Figure 2:

Variations in singleton births by time of day in NHS maternity units (obstetric units, alongside midwifery units, freestanding midwifery units) and at home, England and Wales, 2005-14. Obstetric units with alongside midwifery units have combined data.

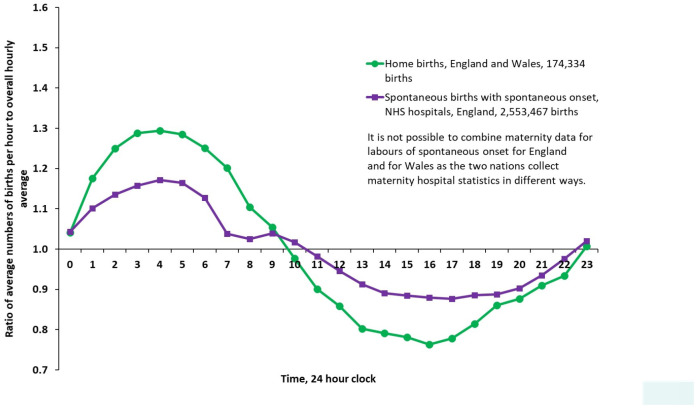

Participants were introduced to the wave-like pattern of times of entirely spontaneous births (Figure 3). These are births in which labour begins spontaneously without induction of labour or surgery and concludes without a caesarean or the medical assistance of forceps or ventouse. They looked at the times when these more natural births occur, with the numbers peaking at night and being lower during the day and questioned why these patterns of entirely spontaneous births differed between home and hospital. They discussed how the impact of environment and culture on the normal physiology of labour may have ‘flattened the curve’.

Figure 3:

Variations in singleton births by time of day, spontaneous births with spontaneous onset in NHS maternity units in England (all three settings combined) and births at home in England and Wales, 2005–14.

At every workshop, there was animated discussion. Participants joined in enthusiastically and knowledgeably with personal experiences and observations, suggesting what they would like to see in future research. They felt able to openly share their concerns and anxieties in the space we had created for this. A feedback questionnaire was distributed at workshop 1. Women reported that they had had a useful and worthwhile day. They found the content of the Birth Timing presentation and the additional training interesting, but they valued the opportunity to network with peers most of all. At the inner city workshop, despite small numbers, there was rich discussion about the maternity experiences of migrant families.

The women’s interest in our work and the questions they raised were written up and presented both to the project team and to the advisory group [1]. The women’s observations, experiences and concerns about ‘out of hours’ care confirmed the importance of analysing, interpreting and describing the study’s results on the outcomes for women and babies according to time of day, week or year of birth and, in particular, comparative data for different places of birth [86].

An unforeseen benefit of the PI&E activity in the study involved the attendance of the Head of Patient Experience for NHS England at the engagement events. She was later approached about the need for more structured support for service user involvement in maternity services. Having heard first-hand about the activities and concerns of parent representatives on MSLCs across the country, she funded NCT to carry out further support, training and mapping of MSLCs in England. She said, ‘seeing the impact of organisations such as NCT in bringing users of services together, who then articulated clearly and repeatedly what was needed, was a critical influencing factor in the commissioning of on-going work.’ (Personal communication, 5 Aug 2020). Thus our creation of broader involvement events in which to place the project’s research engagement work had an impact for service user involvement in maternity services, reported elsewhere [88], as well as for maternity research.

Another benefit of this kind was the creation by an MSLC Chair, following one of the workshops, of a Facebook group to provide ongoing support and sharing of maternity services information from a user perspective. This person had found social media a great way to make the MSLC widely known locally and to gather the experiences and views of mothers and fathers, though parent-led on-line surveys. This development revolutionised the ability for MSLC leaders to keep in touch, provide mutual support and problem-solve collaboratively. It has grown, become formalised and secured funding [89].

Dissemination

Involvement from the PI&E co-investigators continued into the reporting phase. As well as drafting and editing sections of the final report and commenting on papers, they made a summary of the results available on the BirthChoiceUK website and published three reports about the study online through NCT.

Feedback from service users informed our plans for dissemination in terms of messages and target audiences:

Service users were clear that commissioners and healthcare professionals would benefit from understanding the impact of an institutional setting on the timing of birth compared with being at home, and should consider critically issues such as levels of lighting, degree of privacy and sense of intimacy in different settings.

Women felt their confidence and agency were sometimes undermined by negative stories and confrontational messaging in the traditional broadcast and print media, which focused on risks and harms. They did not know which news they could trust and were enthusiastic about having access to research direct from source. They wanted key messages delivered directly, for example research summaries via videos featuring researchers, rather than through the lens of the press, to provide a better balance of messages.

Discussion

Many of the methodological principles of PI&E, such as ‘being ongoing’ and authentic [26] ran throughout the study, evident from funding application and design to analysis, writing up and dissemination. Our use of a three-tier approach was novel. The use of service user researchers as knowledge intermediaries [12], who occupied a position between the project team and recent maternity services users, allowed us to bridge the gap between research and lived experience, which ensured the relevance and social legitimacy of the study.

Extent to which PI&E influenced the study

The PI&E co-investigators, with long-standing service user involvement in the maternity services and research, were able to directly influence the study through their participation in team meetings and active discussion of the analyses and results with the researchers from a service user perspective. Their communication and group facilitation skills aided public engagement and are very different from the traditional skill sets of epidemiologists and data analysts [90].

Through connecting the data researchers with the maternity service users, they were able to act as knowledge intermediaries. Their specialised knowledge of maternity evidence, policy and practice ensured that the project stayed relevant to current issues in maternity care provision and workforce issues. They had complementary skills: MS’s data skills, developed by creating an interface between pregnant women and maternity statistics, enabled her to bridge effectively between the highly technical aspects of the study and lived experience [26]; MN’s long experience of work in policy, research and user engagement was relevant in leading the workshops and in communicating the findings to the research team.

Our public involvement advisory group members also acted as knowledge intermediaries advising on the strategic direction of the project. Within the group of research professionals discussing technical data linkage issues, they could draw on relevant multidisciplinary committee experience, their own knowledge of maternity services and the experiences of women and families with whom they came into contact which added a different perspective to the discussions. Although subtle and difficult to measure, the presence and contributions of service users have an influence on the processes and language of the wider team. Further, comparative research to investigate processes of service involvement influence would be useful.

Like the service user advocates (defined above) [24], the women we engaged from MSLCs around England and Wales were advocates who had two-way connections between women in their area and their local maternity services. Staffing levels were referred to many times by service users, and though the study is not able to analyse staffing levels, it is widely understood that there can be different levels of staffing, of staff seniority and access to interpreters at different times, such as at night and at the weekend, so the women’s perspectives were noted for future research and to provide context for the on-going Birth Timing analysis. A planned focus of the research was timing of births in different places, and associated characteristics and outcomes. During feedback and discussion in the workshops, the attendees emphasised that understanding how place of birth affects the timing of birth was of interest and importance for them. Their contributions confirmed that the planned analyses were relevant and validated the research team’s use of patient-identifiable data, providing legitimacy to the study. Their suggestions on safety are likely to impact the next phase of the study.

Involvement in dissemination had considerable impact, reaching parents, parent educators (NCT practitioners) and academic audiences. Within NCT, one account focused on service user involvement in the Birth Timing study [91], to raise awareness of involvement in research at an organisational and public level and to promote it to the next generation of intermediaries and evidence-based activists [48]. A second was for NCT practitioners focusing on the study findings, and a third, a succinct summary of bullet points, was for the NCT members’ journal intended for pregnant women and new parents. Although the workshop attendees had been enthusiastic about having access to research direct from source, there was no funding for the audio-visual summaries they requested. This idea is being built into the dissemination plan for the next phase of the study. This publication itself will further disseminate these analyses and help to inform those who plan services and women making decisions about their place of birth.

The PI&E work had an impact which reached beyond the data linkage study itself. In addition to the extra funding to support MSLCs in England, MSLCs were re-branded in England as Maternity Voices Partnerships, following the workshop, and NHS England endorsed and promoted using them as a co-production forum [80]. MVPs are now active in all areas of England and NHS England has sponsored a mentoring programme for MVP chairs. As well as MVP leaders connecting via Facebook, an MVP group for parents from Black, Asian and other minority ethnic communities has been created. These developments all started with the events and discussion instigated and orchestrated by the Birth Timing project. In this regard, from a rights-based perspective, the inclusion of PI&E within this project has enabled service user voices to further influence maternity care in a wider context.

Strengths and weaknesses

Many aspects of the strategy for involvement and engagement were successful, as demonstrated by the extent to which PI&E confirmed and reinforced the planned focus of the study, the benefits felt by those taking part and the wider impact on service user involvement in maternity services.

A particular strength was the three-tiered approach of PI&E, led by service user researchers and with active engagement at each tier of participation. This ensured that the project researchers were made aware of the concerns of recent maternity service users about the safety and quality of maternity care, particularly ‘out of hours’ and at weekends and in different settings for birth. They could also be reassured that their use of sensitive health data was viewed as responsible.

Reciprocity was a central driver in the PI&E planning, both in recruiting lay people to become advisory group members and when planning engagement events [92]. This seems to have been a successful strategy, appreciated by the attendees. Benefits for the advisory group members included adding this study appointment to their portfolio of interests or continuing academic or professional development. Workshop attendees were offered an opportunity to network with others involved in improving the quality of their local maternity services, which they valued highly.

Many of the research questions that the women identified as important to them could not be addressed by the Birth Timing data linkage study. They were wide ranging and focused on issues including staffing, postnatal care and breastfeeding support. Of great importance were the potential additional challenges, and possibly poorer outcomes, for more disadvantaged women and those who need translation services, especially during the night and at the weekend. They were also interested in causality and in optimal models of care. So while they valued the questions the study was addressing, they wanted research to go beyond what the current analysis using routinely collected data could encompass.

These ideas have the potential to influence future funding decisions and research programmes using other research methodologies. But, during this phase of this study, to a considerable degree, the researchers were preoccupied with securing approvals to access the data, undertaking technical linkage procedures [1], and data quality and assurance issues [93]. Service users had concerns and interests that only partially overlapped with those of researchers. So, while all of the authors value the principle of co-production, in the real world of data linkage research there are tensions between competing demands and different worldviews [65]. On reflection, it was ambitious to combine setting up the complex data linkage infrastructure and testing alongside the PI&E work, which involves quite different skills and priorities. We are interested that others have taken a sequential approach [63].

Inclusivity in PI&E

It would have enhanced the PI&E in the study to have engaged additional younger women and more women from different cultural backgrounds, such as vulnerable and disadvantaged communities [94]. Inequalities in power relationships within and beyond healthcare [95] and poorer outcomes, particularly for Black women, but also for Asian and other ethnic communities and migrant women should be addressed [85]. Organisations and doula groups focusing specifically on the needs of women of colour [96, 97] and advocating for women and families facing multiple social disadvantage [50] are increasingly accessible as social media open up instant communications and networking. For examples hashtags like #fivexmore and #blackmumsmatter are connecting those campaigning to raise awareness of disparities in maternal outcomes for Black women.

It is difficult to comprehend that just six years ago in 2014, very few of the individuals with whom we engaged were connecting using Facebook or Twitter. Now, community groups, charities, individual advocates and social entrepreneurs can all be reached readily. They need to be invited to research engagement and involvement events, with appropriate funding. In future, engagement recruitment strategies should ensure inclusivity and should routinely collect demographic information to ensure diverse engagement is taking place [98].

Further work

Because the study was delayed by data access restrictions, further analyses are continuing with new funding [1]. These will be able to build on the PI&E input described here to add women’s lived experiences of care to the design of analyses and interpretation of results. There will also be further opportunity for service users to contribute to the analysis plan and reporting. RP will lead the PI&E making use of social media and online meeting facilities as Covid-19 has made non-essential travel and face-to-face meetings impossible during spring and summer of 2020 and not practical for the foreseeable future.

A current pressing need is attention to the factors and processes contributing towards greater adverse outcomes for Black women in the UK [85] which must be addressed by research, policy makers and by the NHS.

There is a growing body of literature on service user involvement in research, but further work is needed to describe and theorise the models and methods, and to explore the roles of those service users working professionally in research.

Recommendations

Based on our positive experience in a data linkage study, we would recommend the following for future PI&E:

Researchers – Involve knowledge intermediaries and/or service user researchers in your project from the start and co-design the project with them as co-investigators and members of the project executive team.

Funders/Researchers/PI&E leads – Plan for diversity of engagement and involvement from the outset; invest adequate budget, time and activities to develop relationships and trust. Make social media central to the PI&E plan to reach specific groups for engagement, including Instagram [99], and collect data on the socio-economic characteristics of attendees.

Researchers/PI&E leads – Recognise the value of inviting wider stakeholders to some of the engagement meetings, including national policy leads, relevant charities and all project steering group members, so that they can be directly immersed in what matters most to the population on which their work is focused.

Funders/Researchers – Establish mechanisms for capturing feedback from service users which is beyond the scope of individual projects and feed it systematically into PI&E intelligence repositories to inform future funding rounds.

Funders – Consider making PI&E funds available specifically at the time they are needed: a) for co-design and funding application preparation; b) for innovative dissemination activities, once the study results have been reported so that current stakeholders can take a leading role. In times of fast-changing social media and online platforms, this would help to ensure continued and renewed engagement and commitment.

Funders – Budgets for all PI&E co-applicants need to be sufficient to enable equal involvement in the project team, or the values and principles of PI&E and co-production [11] are undermined.

Conclusion

Our maternity data linkage study provides a positive case study of the process of PI&E plus ideas of how it might be developed. We undertook the PI&E work in order to identify and respond to the concerns and priorities of pregnant women and families. The three-tier model, with knowledge intermediaries as co-investigators and advisors plus extensive engagement, worked well. The PI&E has been insufficiently inclusive of Black, Asian and minority ethnic communities, however, which is especially important in light of poorer outcomes [85], and this should be addressed. The PI&E impact has already been considerable in maternity services. Contextual information along with data analysis and dissemination suggestions made by women will inform the next stage of the study.

Author contributions

MN produced the first draft of the paper and Table 1 and led the revisions. MS edited the paper, contributed to revising the paper and produced Figure 1. RP contributed key literature and theoretical ideas on PI&E purpose and reporting. AM contributed to revising the paper and produced Figures 2 and 3. All authors approved the final version.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all those who contributed to the project and, in particular, the public engagement and involvement contributors. Kate Bedding, service user representative, Liverpool; Helen Castledine, MSLC representative/public health, Epsom; Debbie Chippington Derrick, Association for Improvements in the Maternity Services (AIMS); and Eleanor Molloy, NCT breastfeeding counsellor, Coventry; were members of the study advisory group and three have commented thoughtfully on this paper. We would like to thank all of those who attended the engagement meetings in Birmingham, Wakefield, Bristol and London, including those who travelled from Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales, and the organisations that participated: NCT, BirthChoiceUK, AIMS, RCOG Women’s Network. We are grateful to Kath Evans, then of NHS England, for all her support, to Ellinor Olander, City, University of London, for organising the inner city parents’ meeting, Yvonne Gailey, NCT, for helping to organise the other engagement events, and Lynn Balmforth, information specialist, for assistance with referencing. We are indebted to all the research staff on the project. Thank you Nirupa Dattani, Rod Gibson, Gill Harper and Mario Cortina-Borja.

Statement of conflicts of interest

None disclosed, apart from sources of salaries.

Ethics and other approvals

Ethics approval 05/Q0603/108 and subsequent substantial amendments were granted by East London and City Local Research Ethics Committee 1 and its successors.

Permission to use confidential patient information without consent under Section 60 of the Health and Social Care Act 2001 was initially granted by the Patient Information Advisory Group PIAG 2-10(g)/2005. Renewals and amendments under Regulation 5 of the Health Service (Control of Patient Information) Regulations 2002 were granted by its successor bodies, the National Information Governance Board and the Secretary of State for Health and the Health Research Authority following advice from CAG.

A second permission CAG 9-08(b)2014 to use confidential patient information without consent under Regulation 5 of the Health Service (Control of Patient Information) Regulations 2002 to create a research database held at the Office for National Statistics for analyses relating to inequalities in the outcome of pregnancy and to inform maternity service users about the outcome of midwifery, obstetric and neonatal care was granted by Secretary of State for Health and the Health Research Authority following advice from CAG.

Permission to access data from the Office for National Statistics in the VML, now known as the Secure Research Service, was granted by ONS’s Microdata Release Panel. All members of the research team successfully applied for ONS Approved Researcher Status. The following disclaimer applies to Figures 2 and 3 which contains statistical data from ONS which is Crown Copyright. The use of the ONS statistical data in this work does not imply the endorsement of the ONS in relation to the interpretation or analysis of the statistical data. This work uses research datasets which may not exactly reproduce National Statistics aggregates.

Permission to link and analyse data held by the Health and Social Care Information Centre, now NHS Digital, was granted under Data Sharing Agreement NIC-273840-N0N0N.

Supplementary appendice

Supplementary Appendix 1: poster about the study which was displayed in NHS clinics and waiting areas.

Funding Statement

Births and their outcome: analysing the daily, weekly and yearly cycle and their implications for the NHS’ was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (https://www.nihr.ac.uk/https://www.nihr.ac.uk/). HS&DR Programme, project number HS&DR 12/136/93 through a grant to City, University of London, in collaboration with University College London and NCT. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Mary Newburn, is now at King’s College London, supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration South London (NIHR ARC South London) at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

References

- 1.Macfarlane A, Dattani N, Gibson R, Harper G, Martin P, Scanlon M, et al. Births and their outcomes by time, day and year: a retrospective birth cohort data linkage study [Internet]. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2019 [cited 2020 May 10]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541376/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hilder L, Moser K, Dattani N, Macfarlane A. Pilot linkage of NHS Numbers for Babies data with birth registrations. Health Stat Q. 2007;33:25-33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dattani N, Datta-Nemdharry P, Macfarlane A. Linking maternity data for England, 2005-06: methods and data quality. Health Stat Q [Internet]. 2011;49:53-79. Available from: 10.1057/hsq.2011.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Datta-Nemdharry P, Dattani N, Macfarlane AJ. Linking maternity data for Wales, 2005-07: methods and data quality. Health Stat Q [Internet]. England: Palgrave Macmillan; 2012 [cited 2020 May 25];54:1-24. Available from: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/6944/ [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wise J. The weekend effect-how strong is the evidence? BMJ [Internet]. 2016;353:i2781. Available from: 10.1136/bmj.i2781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliver S, Liabo K, Stewart R, Rees R. Public involvement in research: making sense of the diversity. J Health Serv Res Policy [Internet]. 2015;20:45-51. Available from: 10.1177/1355819614551848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson E. A resource guide for community engagement and involvement in global health research. [Internet]. National Institute for Health Research/ The Institute of Development Studies NIHR; 2019. Available from: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/researchers/manage-your-funding/NIHR-Community-Engagement-Involvement-Resource-Guide-2019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8.NIHR School for Public Health Research. A strategy for public involvement and engagement 2018 – 2022. [Internet]. National Institute for Health Research; 2019. Available from: https://sphr.nihr.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/NIHR-SPHR-PIE-Strategy_V1.0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9.NCCPE. The engaged university: A Manifesto for Public Engagement. [Internet]. Bristol: National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement; 2019. Available from: https://www.publicengagement.ac.uk/sites/default/files/publication/nccpe_manifesto_for_public_engagement_2019_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10.INVOLVE. What is public involvement in research? [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 5]. Available from: https://www.invo.org.uk/find-out-more/what-is-public-involvement-in-research-2/

- 11.Cowan K. INVOLVE: a practical guide to being inclusive in public involvement in health research: lessons from the Reaching Out programme. [Internet]. Southampton (UK): INVOLVE; 2020 [cited 2020 May 12]. Available from: https://bit.ly/INVOLVEtips [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meagher L, Lyall C. The invisible made visible: using impact evaluations to illuminate and inform the role of knowledge intermediaries. Evid Policy J Res Debate Pract [Internet]. 2013;9:409-418. Available from: 10.1332/174426413X14818994998468 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heron J, Gilbert N, Dolman C, Shah S, Beare I, Dearden S, et al. Information and support needs during recovery from postpartum psychosis. Arch Womens Ment Health [Internet]. 2012;15:155-165. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-012-0267-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beresford P. User Involvement in Research and Evaluation: Liberation or Regulation? Soc Policy Soc [Internet]. Cambridge University Press; 2002 [cited 2020 Aug 14];1:95–105. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746402000222 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rose D, Leese M, Oliver D, Sidhu R, Bennewith O, Priebe S, et al. A comparison of participant information elicited by service user and non-service user researchers. Psychiatr Serv Wash DC [Internet]. 2011;62:210-213. Available from: 10.1176/ps.62.2.pss6202_0210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Realpe A., Wallace L. What is co-production? London: The Health Foundation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoddinott P, Pollock A, O’Cathain A, Boyer I, Taylor J, MacDonald C, et al. How to incorporate patient and public perspectives into the design and conduct of research. F1000Research [Internet]. 2018;7:752. Available from: 10.12688/f1000research.15162.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boote J, Wong R, Booth A. ‘Talking the talk or walking the walk?’ A bibliometric review of the literature on public involvement in health research published between 1995 and 2009. Health Expect Int J Public Particip Health Care Health Policy [Internet]. 2015;18:44–57. Available from: 10.1111/hex.12007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jinks C, Carter P, Rhodes C, Beech R, Dziedzic K, Hughes R, et al. Sustaining patient and public involvement in research: A case study of a research centre. J Care Serv Manag [Internet]. 2013;7:146-154. Available from: 10.1179/1750168715Y.0000000003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung P, Grogan CM Mosley JE. Residents’ perceptions of effective community representation in local health decision-making. Soc Sci Med 1982 [Internet]. 2012;74:1652-1659. Available from: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staley K. Exploring impact: public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research. [Internet]. Eastleigh: INVOLVE; 2009 p. 15. Available from: https://www.invo.org.uk/posttypepublication/exploring-impact-public-involvement-in-nhs-public-health-and-social-care-research/ [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johanson R, Rigby C, Newburn M, Stewart M, Jones P. Suggestions in maternal and child health for the National Technology Assessment Programme: a consideration of consumer and professional priorities. J R Soc Promot Health [Internet]. 2002;122:50-54. Available from: 10.1177/146642400212200115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andejeski Y, Breslau ES, Hart E, Lythcott N, Alexander L, Rich I, et al. Benefits and drawbacks of including consumer reviewers in the scientific merit review of breast cancer research. J Womens Health Gend Based Med [Internet]. 2002;11:119-136. Available from: 10.1089/152460902753645263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andejeski Y, Bisceglio IT, Dickersin K, Johnson JE, Robinson SI, Smith HS, et al. Quantitative impact of including consumers in the scientific review of breast cancer research proposals. J Womens Health Gend Based Med [Internet]. 2002;11:379-388. Available from: 10.1089/152460902317586010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lander J, Hainz T, Hirschberg I, Strech D. Current practice of public involvement activities in biomedical research and innovation: a systematic qualitative review. PloS One [Internet]. 2014;9:e113274. Available from: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aitken M, Tully MP, Porteous C, Denegri S, Cunningham-Burley S, Banner N, et al. Consensus Statement on Public Involvement and Engagement with Data-Intensive Health Research. Int J Popul Data Sci [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 May 5];4. Available from: 10.23889/ijpds.v4i1.586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenhalgh T, Hinton L, Finlay T, Macfarlane A, Fahy N, Clyde B, et al. Frameworks for supporting patient and public involvement in research: Systematic review and co-design pilot. Health Expect [Internet]. 2019;22:785-801. Available from: 10.1111/hex.12888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Staniszewska S, Adebajo A, Barber R, Beresford P, Brady L-M, Brett J, et al. Developing the evidence base of patient and public involvement in health and social care research: the case for measuring impact. Int J Consum Stud [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2020 May 5];35:628–32. Available from: 10.1111/j.1470-6431.2011.01020.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, Seers K, Mockford C, Goodlad S, et al. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. Res Involv Engagem [Internet]. 2017;3:13. Available from: 10.1186/s40900-017-0062-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shippee ND, Domecq Garces JP, Prutsky Lopez GJ, Wang Z, Elraiyah TA, Nabhan M, et al. Patient and service user engagement in research: a systematic review and synthesized framework. Health Expect Int J Public Particip Health Care Health Policy [Internet]. 2015;18:1151-1166. Available from: 10.1111/hex.12090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Banner D, Bains M, Carroll S, Kandola DK, Rolfe DE, Wong C, et al. Patient and public engagement in integrated knowledge translation research: are we there yet? Res Involv Engagem [Internet]. 2019;5:8. Available from: 10.1186/s40900-019-0139-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Staniszewska S, Jones N, Newburn M, Marshall S. User involvement in the development of a research bid: barriers, enablers and impacts. Health Expect Int J Public Particip Health Care Health Policy [Internet]. 2007;10:173-183. Available from: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2007.00436.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jewell A, Pritchard M, Barrett K, Green P, Markham S, McKenzie S, et al. The Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) data linkage service user and carer advisory group: creating and sustaining a successful patient and public involvement group to guide research in a complex area. Res Involv Engagem [Internet]. 2019;5:20. Available from: 10.1186/s40900-019-0152-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.>Birthplace in England Collaborative Group, Brocklehurst P, Hardy P, Hollowell J, Linsell L, Macfarlane A, et al. Perinatal and maternal outcomes by planned place of birth for healthy women with low risk pregnancies: the Birthplace in England national prospective cohort study. BMJ [Internet]. 2011;343:d7400. Available from: 10.1136/bmj.d7400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brett J, Staniszewska S, Newburn M, Jones N, Taylor L. A systematic mapping review of effective interventions for communicating with, supporting and providing information to parents of preterm infants. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2011;1:e000023. Available from: 10.1136/bmjopen-2010-000023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boston Women’s Book Collective. Our bodies, ourselves. New York: Simon and Schuster; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bastian H. Speaking up for ourselves. The evolution of consumer advocacy in health care. Int J Technol Assess Health Care [Internet]. 1998;14:3-23. Available from: 10.1017/s0266462300010485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kitzinger S. Good birth guide. Croom Helm; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kitzinger S. The experience of childbirth. London: Gollancz; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simkin P. The experience of maternity in a woman’s life. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs JOGNN [Internet]. 1996;25:247-252. Available from: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1996.tb02432.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Green JM, Coupland VA, Kitzinger JV. Expectations, experiences, and psychological outcomes of childbirth: a prospective study of 825 women. Birth Berkeley Calif [Internet]. 1990;17:15-24. Available from: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1990.tb00004.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.House of Commons Health Committee, (Chairman Winterton N). Maternity services. Vol II, appendices to the minutes of evidence. Second report, session 1991-92. HC 29-II. London: HMSO; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Department of Health. Changing childbirth: Report of the Expert Maternity Group. London: H.M.S.O.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oakley A. From here to maternity: becoming a mother. Harmondsworth: Penguin; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shapiro MC, Najman JM, Chang A, Keeping JD, Morrison J, Western JS. Information control and the exercise of power in the obstetrical encounter. Soc Sci Med 1982 [Internet]. 1983;17:139–46. Available from: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90247-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Campbell R., Macfarlane A. Where to be born? The debate and the evidence. 2nd ed. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Green JM, Kitzinger JV, Coupland VA. Stereotypes of childbearing women: a look at some evidence. Midwifery [Internet]. 1990;6:125-132. Available from: 10.1016/s0266-6138(05)80169-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Akrich M, Leane M, Roberts C, Arriscado Nunes J. Practising childbirth activism: A politics of evidence. BioSocieties [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2020 May 20];9:129–52. Available from: 10.1057/biosoc.2014.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Newburn M. Women changing maternity services. A look at service user involvement in the UK. MIDIRS Midwifery Dig. 2017;27:5-10. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cardwell V, Wainwright L. Making Better Births a reality for women with multiple disadvantages. [Internet]. London: Revolving Doors Agency; 2018 [cited 2020 May 5]. Available from: http://www.revolving-doors.org.uk/file/2333/download?token=P2z9dlAR [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jackson MK, Schmied V, Dahlen HG. Birthing outside the system: the motivation behind the choice to freebirth or have a homebirth with risk factors in Australia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet]. 2020;20:254. Available from: 10.1186/s12884-020-02944-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith V, Daly D, Lundgren I, Eri T, Begley C, Gross MM, et al. Protocol for the development of a salutogenic intrapartum core outcome set (SIPCOS). BMC Med Res Methodol [Internet]. 2017;17:61. Available from: 10.1186/s12874-017-0341-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vedam S, Stoll K, Martin K, Rubashkin N, Partridge S, Thordarson D, et al. The Mother’s Autonomy in Decision Making (MADM) scale: Patient-led development and psychometric testing of a new instrument to evaluate experience of maternity care. PloS One [Internet]. 2017;12:e0171804. Available from: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vedam S, Stoll K, Taiwo TK, Rubashkin N, Cheyney M, Strauss N, et al. The Giving Voice to Mothers study: inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2019;16:77. Available from: 10.1186/s12978-019-0729-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beresford P. Developing the theoretical basis for service user/survivor-led research and equal involvement in research. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci [Internet]. Cambridge University Press; 2005 [cited 2020 May 28];14:4–9. Available from: 10.1017/S1121189X0000186X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Darzi, Department of Health. High Quality Care For All: NHS Next Stage Review final report CM 7432 [Internet]. Norwich: TSO; 2008. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228836/7432.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 57.NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. The patient experience book: a collection of the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement’s guidance and support. [Internet]. Coventry: NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement; 2013 [cited 2020 May 25]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/improvement-hub/wp-content/uploads/sites/44/2017/11/Patient-Experience-Guidance-and-Support.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 58.Coulter A., Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality: no decision about me, without me. [Internet]. London: The King’s Fund; 2011. Available from: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/making-shared-decision-making-reality [Google Scholar]

- 59.Newburn M. Maternity Voices Partnerships – the new MSLC. Pract Midwife. 2016;19:8-15. [Google Scholar]