Abstract

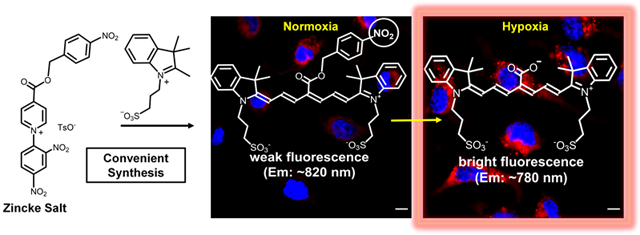

Continued advancement in bioresponsive fluorescence imaging requires new classes of activatable fluorescent probes that emit near-infrared fluorescence with wavelengths above 740 nm. Heptamethine cyanine dyes (Cy7) have suitable fluorescence properties but it is challenging to create activatable probes because Cy7 dyes have a propensity for self-aggregation and fluorescence quenching. A new synthetic strategy is employed to create a generalizable class of hydrophilic bioresponsive near-infrared fluorescent probes with appended sulfonates that provide excellent physiochemical properties. A prototype version is triggered by nitroreductase enzyme to undergo self-immolative cleavage with a large enhancement in fluorescence signal at 780 nm and the probe enables microscopic imaging of cell hypoxia with “turn on” fluorescence. Near-infrared fluorescence imaging of hypoxia is potentially useful in many different areas of biomedical research and clinical treatment.

Graphical Abstract

A new synthetic method produces a bioresponsive near-infrared molecular probe that undergoes “turn-on” fluorescence for microscopic imaging of hypoxia.

Introduction

Fluorescent near-infrared (NIR) dyes are very attractive for biological imaging and sensing because there is maximal penetration of the light through thick biological samples including the skin and tissue of living subjects, and also minimal scattering of the light which enhances image contrast.1 The design challenge is to convert a fluorescent NIR dye into a molecular probe that operates effectively in complex biological media. Basically, there are two major classes of fluorescent NIR molecular probes; those that are “always on” or those that are “bioresponsive”, that is, they “turn on” fluorescence after a chemical transformation is induced by the biological environment.2,3 This latter class of bioresponsive probes has the attractive attribute that strong fluorescence signal is observed only at a specific bioresponsive region of space or point in time, and the background signal beyond the bioresponsive region is very low, which ensures high image contrast.4,5 The potential benefit of this bioresponsive approach is driving ongoing research efforts to develop new classes of activatable NIR fluorescent probes.6

Cyanine heptamethine (Cy7) fluorophores are the most common dye platform for creating NIR fluorescent imaging and sensing probes with absorption/emission wavelengths above 740 nm.7 A range of different photophysical mechanisms have been used to create bioresponsive Cy7 fluorophores.7,8 Further advance towards clinical translation requires the field to produce next-generation Cy7 fluorescent probes with an optimized combination of photophysical, chemical and pharmacokinetic properties. In many cases, this means new and improved Cy7 fluorophore structures with appropriate water solubilizing groups that prevent undesired molecular association processes that degrade bioresponsive signaling such as self-aggregation and accumulation in off-target biological locations. In this regard, a large fraction of bioresponsive Cy7 probes are derived synthetically by substituting the C4’-Cl in precursor Cy7-Cl (Scheme 1) with a group that has a nucleophilic O or N atom.9 This synthetic chemistry works reasonably well with organic-soluble versions of Cy7-Cl, but it is rarely reported with water-soluble variants that have appended sulfonate and quaternary ammonium groups.10 The inability to easily prepare hydrophilic, bioresponsive Cy7 probes with substituted heptamethine chains, tunable pharmacokinetics and high “turn on” fluorescence is currently a significant impediment to further progress. A good illustration of this synthetic deficiency is the published literature on small molecule Cy7 probes that respond to the hypoxia-related enzyme nitroreductase (discussed further below).11 Very few reported examples are sulfonated Cy7 structures and they only exhibit modest levels of “turn on” fluorescence. 10,12,13

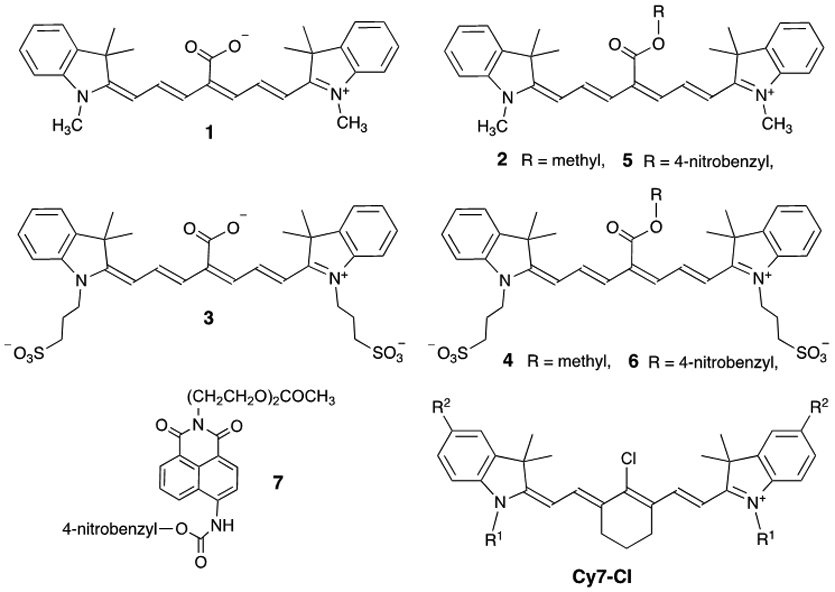

Scheme 1.

Chemical structures

Recently, Štacková and coworkers reported a potential way to overcome this synthetic limitation by developing a new method to make Cy7 dyes by ring opening of Zincke salts.5,14 We subsequently used this innovative synthetic chemistry to design a water-soluble Cy7 fluorophore for bioconjugation and fabrication of “always on” fluorescent NIR molecular probes.15,16 We now report that the Zincke salt synthetic methodology can be used to create a new class of water-soluble, sulfonated bioresponsive NIR Cy7 fluorescent probes with excellent physiochemical properties and very high “turn on” fluorescence. We demonstrate this advance in fluorescent NIR probe design by developing a prototype probe that is triggered by nitroreductase enzyme.

Results and discussion

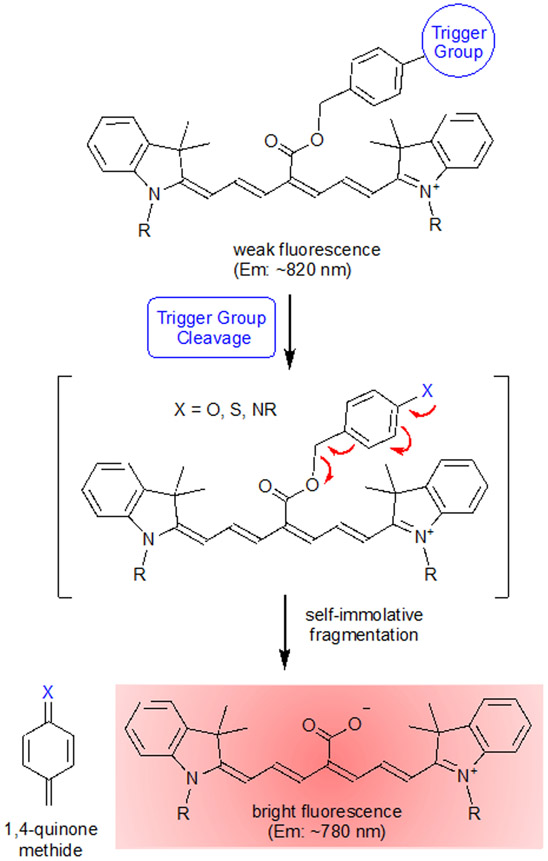

Štacková and coworkers evaluated a series of analogous Cy7 fluorophores with different functional groups located along the heptamethine chain.14 They found that in organic solvent the Cy7 fluorophore 1 with a C4’-carboxylic acid group was blue-shifted by 30 nm and 64 times brighter than its corresponding C4’-methyl ester derivative 2. Intrigued by this observation we prepared the water-soluble sulfonated derivative 3 with C4’-carboxylic acid and the corresponding sulfonated C4’-methyl ester version 4 and observed a very similar large difference in fluorescence brightness (Table 1). This type of functional group dependence is unusual; there are very few literature fluorophores that are weakly fluorescent as a carboxylic ester but highly fluorescent as the corresponding carboxylic acid and none that emit in the NIR.17,18,19,20,21 We reasoned that the fluorogenic effect could be combined with a self-immolative cleavage mechanism, such as a 1,6-elimination, to produce a new class of “turn-on” NIR fluorescent probes.22,23 The generic probe structure in Scheme 2 is comprised of a Cy7 fluorophore with a C4’-benzyl ester group that has an appended Trigger Group. Chemical activation of the Trigger Group by a stoichiometric or enzyme catalyzed reaction reveals an unstable phenol or aniline derivative that spontaneously fragments to produce the corresponding C4’-carboxylic acid with enhanced fluorescence. A by-product of the self-immolation process is a reactive 1,4-quinone methide derivative that is scavenged by water to generate a benzyl alcohol.

Table 1.

Photophysical properties of dyes 1-7 in methanola

| Dye | λabsmax (nm) | λemmax (nm) | ε (M−1cm−1) | Quantum Yield (%) |

Fluorescence Brightnessc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 749 | 774 | 242,000d | 13.2d | 31944 |

| 2 | 779 | 826 | 150,000d | 0.6d | 900 |

| 3 | 754 | 781 | 83,400 | 11.0b | 9132 |

| 4 | 785 | 824 | 51,860 | 0.16b | 84 |

| 5 | 782 | 814 | 153,350 | 0.23b | 347 |

| 6 | 792 | 821 | 51,510 | 0.16b | 83 |

All measurements at room temperature.

Relative to 1 in methanol, error is ± 10%.

Fluorescence brightness = ε × quantum yield, error is ± 15%.

Data from ref 5

Scheme 2.

Conceptual picture of bioresponsive NIR fluorescent Cy7 probe based on a self-immolation reaction (1,6-elimination). The reactive 1,4-quinone methide by-product is scavenged by water to generate a benzyl alcohol derivative.

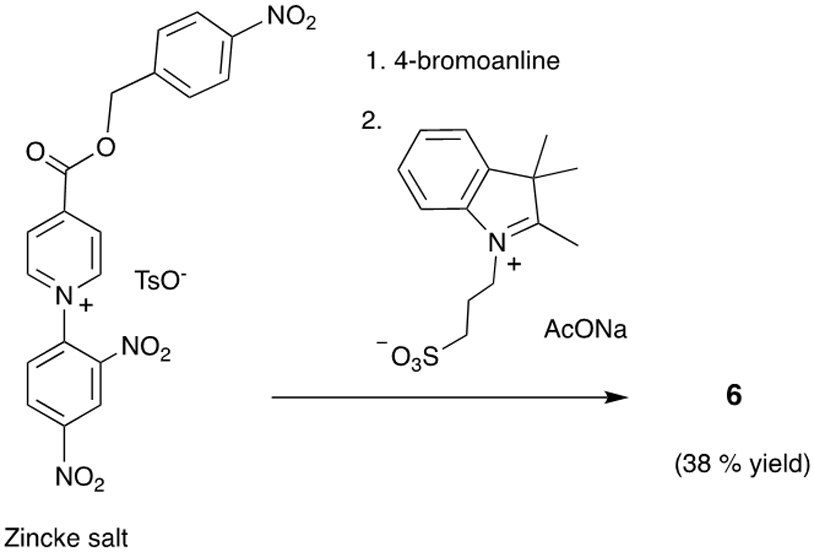

We tested this probe design hypothesis by developing two prototype NIR fluorescent probes that indicate the overexpression of nitroreductase enzyme associated with cell hypoxia. In short, cells and tissue respond to low oxygen conditions (hypoxia) by biosynthesizing reductase enzymes such as nitroreductase.24 Several fluorescent NIR probes with 4-nitrobenzyl groups are known to be triggered by nitroreductase to undergo self-immolative fragmentation and fluorescence enhancement.11 With this precedence in mind, we prepared the analogous Cy7 probes 5 and 6, each with a C4’-nitrobenzyl ester group. The synthesis of these two Cy7 dyes, by ring opening of Zincke salts, is described in the ESI. An important strategic advantage with this synthetic method is that the water-solubilizing groups (sulfonates in the case of 6) are introduced in one step after the Trigger Group (in this case, a 4-nitrobenzyl ester) has been installed on the polymethine chain.5 The key reaction is the catalyzed transimination process shown in Scheme 3, which occurs at room temperature and tolerates a wide range of functional groups. We anticipate that this synthetic sequence will be a convenient way to make a wide range of new water-soluble bioresponsive Cy7 probes with the general molecular design shown in Scheme 2.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of probe 6 via the Zincke salt allows the sulfonates to be introduced in one step after the 4-nitrobenzyl ester trigger group has been formally installed on the polymethine chain.

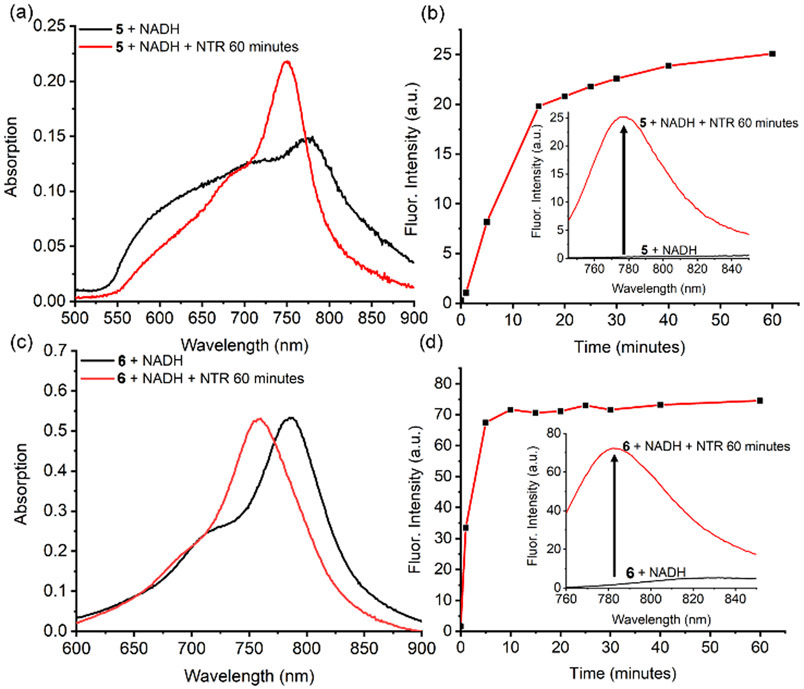

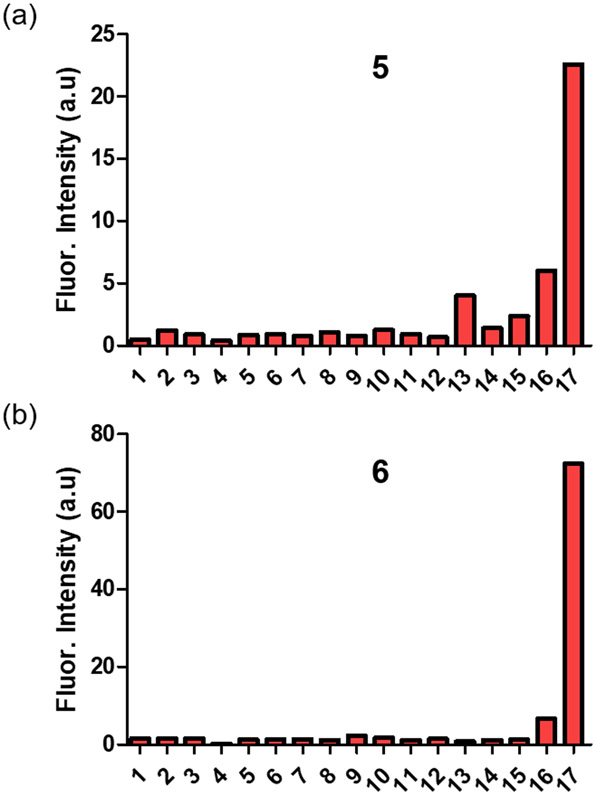

In Figure 1 and Figures S3-S9 are the absorption and emission spectra for separate solutions of the four compounds 1, 3, 5, and 6 and listed in Tables 1 and S1 are the spectral properties of all the Cy7 compounds in Scheme 1. As expected, the absorption bands for hydrophobic 1 and 5 in PBS are broad due to dye self-aggregation (confirmed by Dynamic Light Scattering, Figure S14). In contrast the absorption bands for sulfonated versions 3 and 6 in PBS are narrower indicating less self-aggregation. Cuvettes studies showed that treatment of separate samples of 5 and 6 with nitroreductase enzyme and the necessary cofactor NADH produced the expected changes in absorption and emission (Figure 1). That is, a 30 nm blue shifted absorption band appeared corresponding to the production of carboxylates 1 and 3 (probe cleavage confirmed by HPLC analysis, see Figure S17) along with a concomitant large increase in fluorescence emission at ~780 nm. The kinetic profiles in Figure 1 also indicate that the enzymatic cleavage of 6 was faster than the cleavage of 5. Presumably this kinetic difference is due to the probe aggregation state, with the enzyme able to gain faster access to the less aggregated probe 6.‡ A control experiment showed that the Cy7 derivatives 2 and 4, each with a C4’-methyl ester group does not respond to nitroreductase (Figure S20), consistent with enzyme catalyzed reduction of the nitro group as the chemical process that triggers the fluorescence response. Furthermore, there was no fluorescence enhancement of 5 or 6 when NADH, the necessary nitroreductase cofactor, was omitted from the sample, or when the known nitroreductase inhibitor, dicoumarol, was added to the sample (Figures S19). A series of cuvette experiments that mixed separate samples of 5 or 6 with various common intracellular analytes found that major fluorescence enhancement could only be triggered by nitroreductase enzyme (Figure 2).§ Three sets of experimental findings showed that C4’-ester group in 6 is not susceptible to cleavage by esterase enzyme: (1) There was no cleavage of 6 to produce 3 after incubation with porcine liver esterase (a broad specificity enzyme) for 24 hours (Figure S22). (2) Porcine liver esterase cleaves the known esterase substrate Calcein AM, whereas 6 is not an esterase substrate under the same conditions (Figure S23). (3) Probe 6 is not cleaved by the presence of porcine liver esterase, but a subsequent addition of nitroreductase to the sample produces a rapid and large increase in NIR fluorescence due to appearance of cleavage product 3 (Figure S24). This latter result suggests that cleavage of probe 6 by intracellular nitroreductase enzyme is substantially more efficient than any putative probe cleavage by intracellular esterase enzyme.

Figure 1.

(a, c) Absorption spectra of 5 or 6 (5 μM) in PBS (pH 7.4, 37 °C) supplemented with NADH (500 μM), before and 60 minutes after addition of nitroreductase (NTR, 1 μg/mL). (b, d) Fluorescence spectra of the same samples, along with the change over time of fluorescence intensity at 780 nm. For 5, λex = 733 nm, and for 6, λex = 750 nm.

Figure 2.

Relative fluorescence intensity of (a) 5 or (b) 6 (5 μM) alone (1), or after addition of Cys (2), Tyr (3), HOCl/OCl− (4), Trp (5), Ser (6), Glucose (7), Ascorbic acid (8), Na+ (9), GSH (10), DTT (11), H2O2 (12), NADH + Rat liver microsomes (5 μg/mL) (13), porcine liver esterase (0.05 μg/mL) (14), porcine liver esterase (1 μg/mL) (15), NADH + NTR (0.05 μg/mL) (16), NADH + NTR (1 μg/mL) (17), after 30 minutes in ultrapure water. For 5 λex = 733 nm. For 6 λex = 750 nm, λem = 782 nm. The concentration of all added analytes was 5 μM. T = 25 °C. Error bars are too small to be visualized.

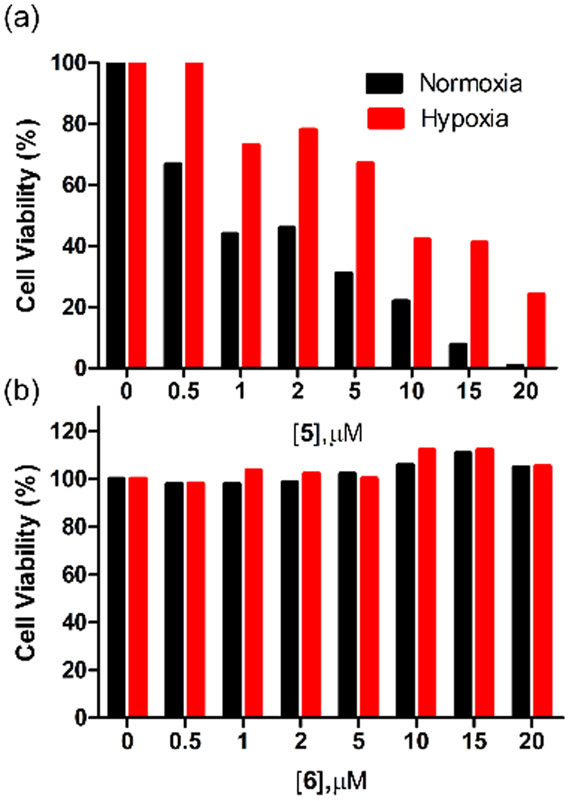

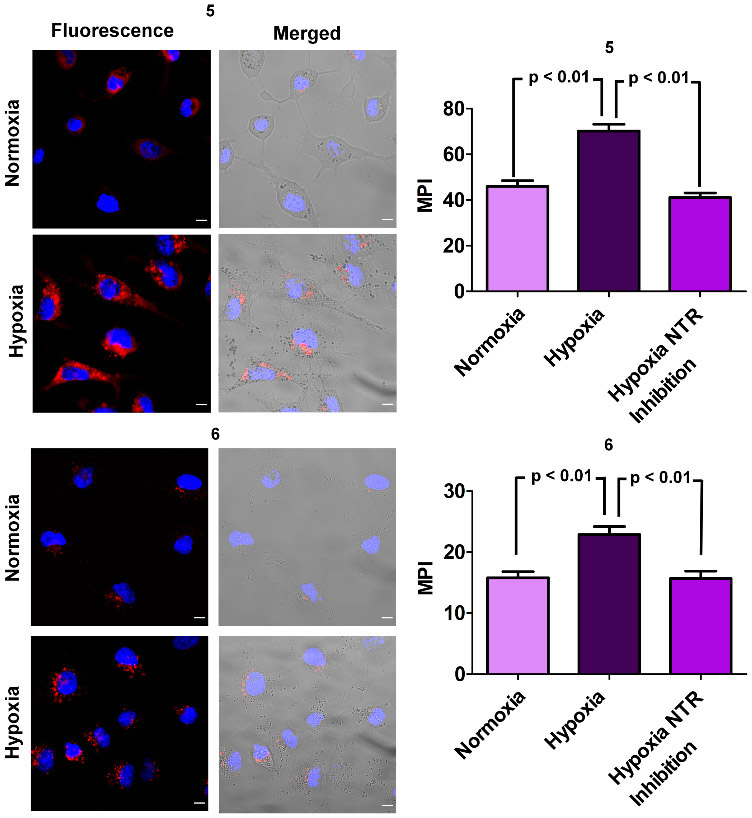

The capabilities of 5 and 6 as fluorescent NIR probes for cell hypoxia were tested in a cell culture model. In short, A549 cells (lung adenocarcinoma) were treated with an aliquot of fluorescent probe, and then maintained under normoxic (20% oxygen) or hypoxic (1 % oxygen) conditions for 12 hours. Independent protein expression measurements confirmed that the hypoxic condition raised the amount of intracellular nitroreductase by almost three-fold over 12 hours (Figure S25). Fluorescence microscopy experiments using the known and validated nitroreductase probe 7 (Figures S29 and S30) showed that the hypoxic cells produced about twice the fluorescence response.25 Separate experiments that treated normoxic and hypoxic cells with the Cy7 probes 5 and 6 also observed the same increased level of NIR fluorescence in the hypoxic cells (Figure 3). Pretreating the hypoxic cells with the nitroreductase inhibitor dicoumarol produced no difference in NIR fluorescence compared to normoxic cells (Figures 3 and S26), implicating increased intracellular nitroreductase as the reason for the enhanced fluorescence in hypoxic cells. Cell viability assays found that Cy7 probe 5 was quite toxic to the cells but the sulfonated analogue 6 produced no cell toxicity (Figure 4). Furthermore, the carboxylic products 1 and 3 were not cell toxic (Figure S31). We suspected that the hydrophobic and cationic 5 accumulates more in the cell mitochondria and supporting evidence for this hypothesis was gained from separate cell co-incubation studies that treated cells with fluorescent NIR probe and fluorescent mitotracker green. Fluorescence co-localization micrographs indicated substantially higher mitochondria accumulation in cells treated with probe 5 than cells treated with probe 6 (Figures S27 and S28). Thus, the greater cell toxicity of probe 5 correlates with increased mitochondria accumulation but presently we have no proof of causality.

Figure 3.

Representative epifluorescence images of A549 cells that were treated for 12 hours with either 5 or 6 (5.0 μM) under conditions of normoxia (20 % O2) or hypoxia (1% O2). Length scale bar = 20 μm. Red fluorescence is the NIR probe and blue fluorescence is cell nucleus stained with Hoechst dye. The bar graphs show quantification of intracellular NIR fluorescence intensities as mean pixel intensity (MPI) and include a comparison with probe-treated hypoxic cell populations that were pre-treated with the nitroreductase (NTR) inhibitor dicoumarol.

Figure 4.

Cell viability assay of A549 cells treated for 12 hours with (a) 5 or (b) 6 at 37 °C, under conditions of hypoxia (1 % O2) or normoxia (20 % O2). Error bars are too small to be visualized.

To demonstrate the feasibility of 5 and 6 as fluorescent NIR probes for future in vivo imaging studies we conducted phantom imaging experiments using a standard animal imaging station and found that nitroreductase-activated increases in NIR fluorescence intensity were easily observed as high contrast images (Figure S18). Moreover, constant NIR irradiation of separate solutions containing the probe cleavage products 1 or 3, showed comparatively high photostability compared to the clinically approved heptamethine cyanine dye ICG (Figure S32), further supporting the feasibility for in vivo imaging.

Conclusions

The combination of good water solubility, low propensity for self-aggregation, resistance to esterase action, non-toxicity, and large nitroreductase-triggered enhancement of NIR fluorescence makes sulfonated Cy7 fluorophore 6 a very attractive choice for further study as a “turn on” fluorescent NIR probe for imaging hypoxia in living subjects. From a broader perspective, the general self-immolation mechanism in Scheme 2 can undoubtedly be expanded beyond 1,6-elimination processes to include different types of intramolecular cyclizations that do not create reactive quinone methide by-products.22,23,26 Collectively, these bond fragmentation processes can be triggered by a wide range of stoichiometric chemical reactions and enzyme catalyzed cleavage processes,1,7,27 thus enabling selective NIR fluorescence sensing and imaging of chemical and enzymatic activity in complex biological media. Furthermore, it should be possible to substitute the indolinene units at each end of the Cy7 fluorophore with additional π-extended units that extend the absorption/emission wavelengths beyond 1000 nm and thus create bioresponsive probes for the NIR II region.6 Typically, these π-extended units will increase molecular hydrophobicity but this potential drawback can be countered by the presence of sulfonate groups as exemplified by structure 6. In this regard, it is worth emphasizing the major synthetic advantage gained by preparing sulfonated bioresponsive Cy7 probes by the strategy employed in this study; i.e., using Zincke salt methodology to introduce the sulfonates in one step after the Trigger Group (Scheme 3).5 This synthetic innovation provides convenient access to the desired water-soluble bioresponsive NIR probes with the non-toxicity and favorable physiochemical and pharmacokinetic properties that are necessary for eventual clinical translation. Studies that explore these opportunities are underway and the results will be reported in due course.

Experimental

Synthesis and compound characterization

All synthetic procedures and compound characterization are provided in the ESI.

Enzyme Cuvette Studies

Separate stock solutions of molecular probes 5, 6, and 7 were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). A stock solution of nitroreductase (NTR from Escherichia coli, purchased from Sigma Aldrich) was prepared in cold ultrapure water and preserved at −20 °C. A stock solution of NADH was also prepared in cold ultrapure water when needed and stored at −20°C. An aliquot of molecular probe (5 μM) was added to a cuvette containing 1X PBS Buffer, followed by the addition of NADH (500 μM) and NTR (1 μg/mL). The final mixture had a total volume of 1 mL and solutions were mixed by inversion for 5 seconds before monitoring changes in absorbance and fluorescence spectra. Enzyme inhibition studies used dicoumarol (DC) (0.25 mM), a known competitive inhibitor of NTR. The order of addition was molecular probe (5 μM), DC (0.25 mM), NADH (500 μM) and NTR (1 μg/mL).

Cell Microscopy Studies

Cell Culture Conditions:

A549 (ATCC® CCL-185™) human lung adenocarcinoma cells were obtained and cultured and maintained in F12K Media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin streptomycin. Culture was done at 37 °C, air supplemented with 5 % CO2.

Sample Preparation and Microscopic Imaging:

A549 cells were plated onto an 8-well chambered coverglass (Lab-Tek, Nunc) and grown to 80% confluency (48 hours). The medium was then removed, and the cells were washed with PBS twice. Separate cell samples were incubated with 5 μM of molecular probe in warm F12K media at 37 °C for 12 hours in a chamber that maintained hypoxic (1% O2) or normoxic (20% O2) atmosphere (also containing 5% CO2). After incubating the cells with probes, the media was removed, and cells were washed three times with PBS. Cells were then stained with Hoechst dye (3 μM) for 10 min, and finally washed three times with PBS and imaged under Opti-mem Media using a Zeiss Axiovert 100 TV epifluorescence microscope (63 X) equipped with a DAPI filter (ex: 445/40, em: 494/20) to image the nucleus and ICG filter (ex: 769/41, em: 832/37) to image NIR fluorescence. All experiments were repeated three times and micrographs of 6 separate viewing fields were obtained during each trial and analyzed using image J software. For each micrograph, a background subtraction with a rolling ball radius of 20 pixels was applied. Next, a triangle threshold was employed and used to calculate the average mean pixel intensity (MPI) where overall averages and SEM were calculated and plotted in GraphPad Prism. p values were calculated using t tests with ANOVA.

Intracellular Nitroreductase Inhibition Studies:

A549 cells were plated onto an 8-well chambered coverglass and grown to 80% confluency (48 hours). The medium was then removed, and the cells were washed with PBS twice. Separate cell samples were incubated with 0.1 mM dicoumarol (DC) for 30 minutes in media. The media was then removed, and cells were washed three times with PBS. Cells were treated with an aliquot of 5 or 6 (5 μM) in warm F12K media and then incubated at 37 °C for 12 hours under hypoxic atmosphere (1% O2). After incubating cells with probes, the media was removed, and cells were washed three times with PBS. Cells were then stained with Hoechst dye (3 μM) for 10 min, and finally washed three times with PBS and imaged under Opti-mem Media. The ICG filter set was used to image the NIR fluorescence and DAPI filter was used to image the nucleus. All experiments were repeated three times and images of 6 separate viewing fields were obtained during each trial.

Colocalization Assay of Cells:

A549 cells were plated onto an 8-well chambered coverglass and grown to 80% confluency (48 hours). The media was then removed, and the cells were washed with PBS twice. Cells were treated with an aliquot of 5, or 6 (5 μM) in warm F12K media and then incubated at 37 °C for 12 hours under hypoxic (1% O2) atmosphere. Then, the media was removed and cells were washed three times with PBS. Mitotracker Green (100 nm) was added to each well and cells were incubated at 37 °C for 15 minutes under hypoxic (1% O2) atmosphere. Cells were then washed three times with PBS and subsequently stained with Hoechst dye (3 μM) for 10 min, and finally washed three times with PBS and imaged under Opti-mem Media. The ICG filter set was used to image the NIR fluorescence of 5 or 6 and FITC filter set was used to image the Mitotracker Green. Pearson’s correlation coefficients and Mander’s coefficients (M1 and M2) were calculated using the JACoP plugin in image J (Figure S27-S28). M1 is the ratio of the total intensity of pixels from 5 or 6 which overlaps with the total intensity of the mitotracker. M2 is the opposite which shows total overlap of the mitotracker with 5 or 6. All experiments were repeated three times and images of 6 separate viewing fields were obtained during each trial.

Cell Viability Measurements:

A549 cells were seeded in 96 well plates at a density of 5 x 103 cells/well and grown to 80% confluency for 48 hours at 5% CO2 atmosphere. The media was then removed, and different concentrations of each molecular probe were added to the cells (N = 3). Cells were then incubated with probes under normoxic (20% O2) or hypoxic (1% O2) atmosphere (still containing 5% CO2) for 12 hours at 37°C. Then, the media containing the molecular probe was removed and fresh medium containing 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) was added to cells for an additional 4 hour incubation (hypoxia: 1% O2 and Normoxia: 20% O2). After 4 hours, SDS-HCl was added to wells to dissolve MTT crystals and the cells were incubated overnight at 37°C. The absorbance at 570 nm was then measured and a plot of the cell viability was obtained under each condition. All experiments were repeated three times.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for funding support from the US NIH (R35GM136212 and T32GM075762).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Synthesis and characterization, supplementary figures and references. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

The Michaelis-Menten constants for nitroreductase catalysed cleavage of 6 were determined to be Km = 17 μM and and Vmax = 0.18 μMs−1. See Figure S21 for data and Table S2 for a comparison with related literature NIR fluorescent nitroreductase probes. It was not possible to determine the Michaelis-Menten constants for cleavage of 5 because of extensive concentration-dependent probe self-aggregation.

Inspection of Figure 2 shows that the fluorescence of probe 5 is enhanced slightly by the presence of rat liver microsomes which is attributed to dequenching of the lipophilic probe due to interaction with the microsomal membrane. This effect is not observed with more hydrophilic probe 6.

Notes and references

- (1).Li Y; Zhou Y; Yue X; Dai Z Adv. Healthc. Mater 2020, 9, 2001327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).van Duijnhoven SMJ; Robillard MS; Langereis S; Grüll H Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2015, 10, 282–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Luby BM; Charron DM; MacLaughlin CM; Zheng G Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 2017, 113, 97–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Singh K; Rotaru AM; Beharry AA ACS Chem. Biol 2018, 13, 1785–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Štacková L; Štacko P; Klán PJ Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 7155–7162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Chen C; Tian R; Zeng Y; Chu C; Liu G Bioconjug. Chem 2020, 31, 276–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Sun W; Guo S; Hu C; Fan J; Peng X Chem. Rev 2016, 116, 7768–7817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Mo S; Zhang X; Hameed S; Zhou Y; Dai Z Theranostics 2020, 10, 2130–2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Exner RM; Cortezon-Tamarit F; Pascu SI Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 29, 2–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Okuda K; Youssif BGM; Sakai R; Ueno T; Sakai T; Kadonosono T; Okabe Y; Salem OIAR; Hayallah AM; Hussein MA; Kizaka-Kondoh S; Nagasawa H Heterocycles 2020, 101, 559–579. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Qi YL; Guo L; Chen LL; Li H; Yang YS; Jiang AQ; Zhu HL Coord. Chem. Rev 2020, 421, 213460. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Youssif BGM; Okuda K; Kadonosono T; Salem OIAR; Hayallah AAM; Hussein MA; Kizaka-Kondoh S; Nagasawa H Chem. Pharm. Bull 2012, 60, 402–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Okuda K; Okabe Y; Kadonosono T; Ueno T; Youssif BGM; Kizaka-Kondoh S; Nagasawa H Bioconjug. Chem 2012, 23, 324–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Štacková L; Muchová E; Russo M; Slavíček P; Štacko P; Klán PJ Org. Chem 2020, 85 (15), 9776–9790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Li D-H; Schreiber CL; Smith BD Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 12154–12161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Schreiber CL; Li D-H; Smith BD Anal. Chem 2021, 10.1021/acs.analchem.1c00276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Liu Z; Song F; Shi W; Gurzadyan G; Yin H; Song B; Liang R; Peng X ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 15426–15435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Kim T Il; Kim H; Choi Y; Kim Y Sensors Actuators, B Chem. 2017, 249, 229–234. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Zhou J; Xu S; Yu Z; Ye X; Dong X; Zhao W Dye. Pigment 2019, 170, 107656. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Liu G; Hu J; Liu S Chem. Eur. J 2018, 24, 16484–16505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Kim S; Kim H; Choi Y; Kim Y Chem. Eur. J 2015, 21, 9645–9649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Yan J; Lee S; Zhang A; Yoon J Chem. Soc. Rev 2018, 47, 6900–6916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Gnaim S; Shabat D Acc. Chem. Res 2019, 52, 2806–2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Liu J; Bu W; Shi J Chem. Rev 2017, 117, 6160–6224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Cui L; Zhong Y; Zhu W; Xu Y; Du Q; Wang X; Qian X; Xiao Y Org. Lett 2011, 13, 928–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Deng Z; Hu J; Liu S Macromol. Rapid Commun 2020, 41, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Bruemmer KJ; Crossley SWM; Chang CJ Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 13734–13762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.