Abstract

Purpose

To synthesize the diverse body of literature on sexual and gender minority youth (SGMY) and sexual health education.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search of the literature on SGMY and sexual health education, including SGMY perspectives on sexual health education, the acceptability or effectiveness of programs designed for SGMY, and SGMY-specific results of sexual health education programs delivered to general youth populations.

Results

A total of 32 articles were included. Sixteen qualitative studies with SGMY highlight key perspectives underscoring how youth gained inadequate knowledge from sexual health education experiences and received content that excluded their identities and behaviors. Thirteen studies examined the acceptability or effectiveness of sexual health interventions designed for SGMY from which key characteristics of inclusive sexual health education relating to development, content, and delivery emerged. One study found a sexual health education program delivered to a general population of youth was also acceptable for a subsample of sexual minority girls.

Conclusions

Future research on SGMY experiences should incorporate populations understudied, including younger adolescents, sexual minority girls and transgender persons. Further, the effectiveness of inclusive sexual health education in general population settings requires further study.

Introduction

Disparities in sexual and reproductive health (SRH) persist among sexual and gender minority populations, subgroups of whom are more likely to be infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), diagnosed with a sexually transmitted disease (STD), or involved in unintended pregnancy than their heterosexual and cisgender peers.1–4 Behaviors established in adolescence may place sexual and gender minority youth (SGMY) at higher risk of experiencing these adverse SRH outcomes. For example, data from the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System indicate that higher proportions of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender students ever had sex and engaged in sexual risk behaviors, such as not using a condom during last sexual intercourse, in comparison to heterosexual and cisgender students.5,6 A central driver for these health inequities may be gaps in SRH knowledge and skills for SGMY as a result of inadequate sexual health education.

Sexual health education is a systematic, evidence-informed approach designed to promote sexual health and prevent risk-related behaviors and experiences which are associated with HIV/STD and unintended pregnancy.7,8 Delivered in a variety of settings including schools, clinics, and community settings, sexual health education equips youth with functional health information and fosters skill development across structured, sequential learning experiences. Research, primarily among heterosexual populations, has shown that sexual health education can be associated with decreases in sexual risk behaviors.9,10 However, an outstanding question is whether existing sexual health education programs are meeting the needs of SGMY.

SGMY need medically accurate, developmentally appropriate, and culturally inclusive sexual health education that reflects their lived experiences and identities. However, results from the National School Climate Survey indicate that among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) students who received school-based sexual health education, approximately 79% reported no inclusion of LGB topics and 83% reported no inclusion of transgender/gender non-conforming topics.11 Further, the national landscape of school-based sexual health education is highly variable. As of October 2020, only 17 states and the District of Columbia articulate explicit views on sexual orientation as part of sexual health education, of which only 11 states and the District of Columbia require that discussions of sexual orientation be inclusive.12 Moreover, some state laws and policies explicitly prohibit health and sexuality education teachers from discussing SGM people or topics in a positive light – if at all.13 The impact of such exclusions can be far-reaching; for example, in states where SGMY-inclusive sexual health education is less common, students reported higher odds of experiencing victimization and adverse mental health outcomes.14

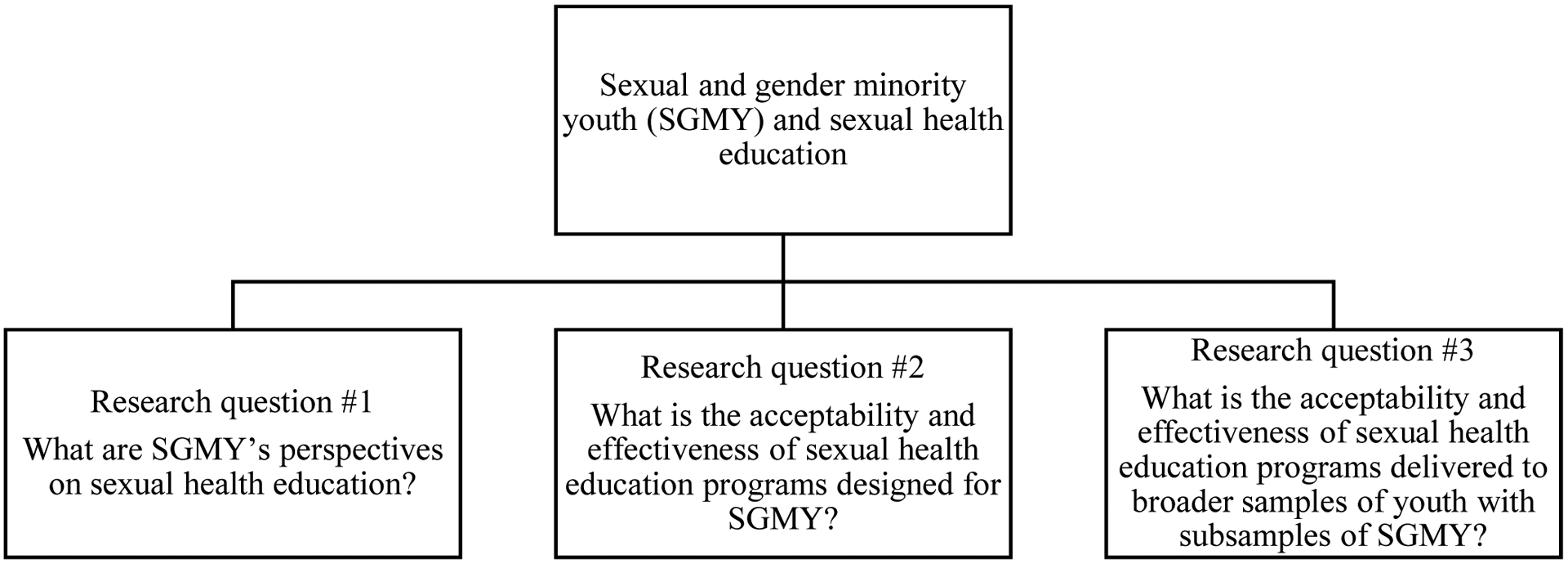

Several observational and experimental studies speak to the experiences of SGMY in relation to both school- and community- based sexual health education. We conducted a systematic search of this diverse body of literature and synthesized it to provide a state-of-the-field summary of sexual health education for SGMY. Specifically, we aim to answer the following research questions: (1) What are SGMY’s perspectives on sexual health education; (2) what is the acceptability and effectiveness of sexual health education programs designed for SGMY; (3) what is the acceptability and effectiveness of sexual health education programs delivered to broader samples of youth with subsamples of SGMY? Further, we extend the literature by critically reviewing the evidence, delineating directions for future research and practice, and identifying subpopulations and settings for prioritization.

Methods

Figure 1 illustrates the bodies of literature we aimed to capture. A number of studies have examined SGMY’s perspectives on sexual health education (domain #1), which we thematically synthesize to capture key perspectives. Further, we identify existing sexual health education programs delivered to SGMY exclusively and summarize the characteristics, acceptability, and effectiveness of these programs (domain #2). Finally, we identify and synthesize studies on sexual health programs that were delivered to broader samples of youth but present acceptability or effectiveness findings for subsamples of SGMY (domain #3).

Figure 1.

Research questions

Relevant articles for this study were identified via a systematic search of five databases: Medline, CINAHL, PsychInfo, Sociological Abstracts, and ERIC. We searched keywords relating to three domains: SGM identities (e.g., transgender, men who have sex with men [MSM], homosexual, same sex, lesbian), adolescents (e.g., young adult, teen, high school), and sexual health programming (e.g., sex education, HIV program). An experienced librarian developed the search strategy with input from co-authors (Supplemental File 1). In addition, the authors searched the reference lists of included studies to identify additional articles that described studies that met our inclusion criteria but were not initially captured in the database searches.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

To meet inclusion criteria, articles had to: (1) be published in a peer-reviewed English language journal between 2000 – 2017; (2) have a sample mean age between 10 and 24; (3) have a US sample, (4) present empirical data, and (5) present findings with data from SGMY. This final criterion included studies on SGM youths’ perspectives on sexual health education generally, and studies on the acceptability or effectiveness of a sexual health education program for a sample or subsample of SGMY. When studies did not report the mean age, the age distribution and inclusion criterion age range was examined. Exclusion criteria included: (1) theoretical papers, conference proceedings, and commentaries; and (2) studies exclusively focused on the program development process without examining the acceptability or effectiveness of the program. Both qualitative and quantitative studies were considered.

Abstract Screening and Data Extraction

Four coders with experience conducting systematic reviews reviewed each abstract for eligibility. All coders screened the abstracts of the same 100 articles as part of the norming process. Once all coders were familiar with the screening criteria, the remaining abstracts were distributed equally. Throughout the abstract screening process, if a coder was unsure about the eligibility of a specific article, the article was brought up for discussion with all coders until consensus was achieved.

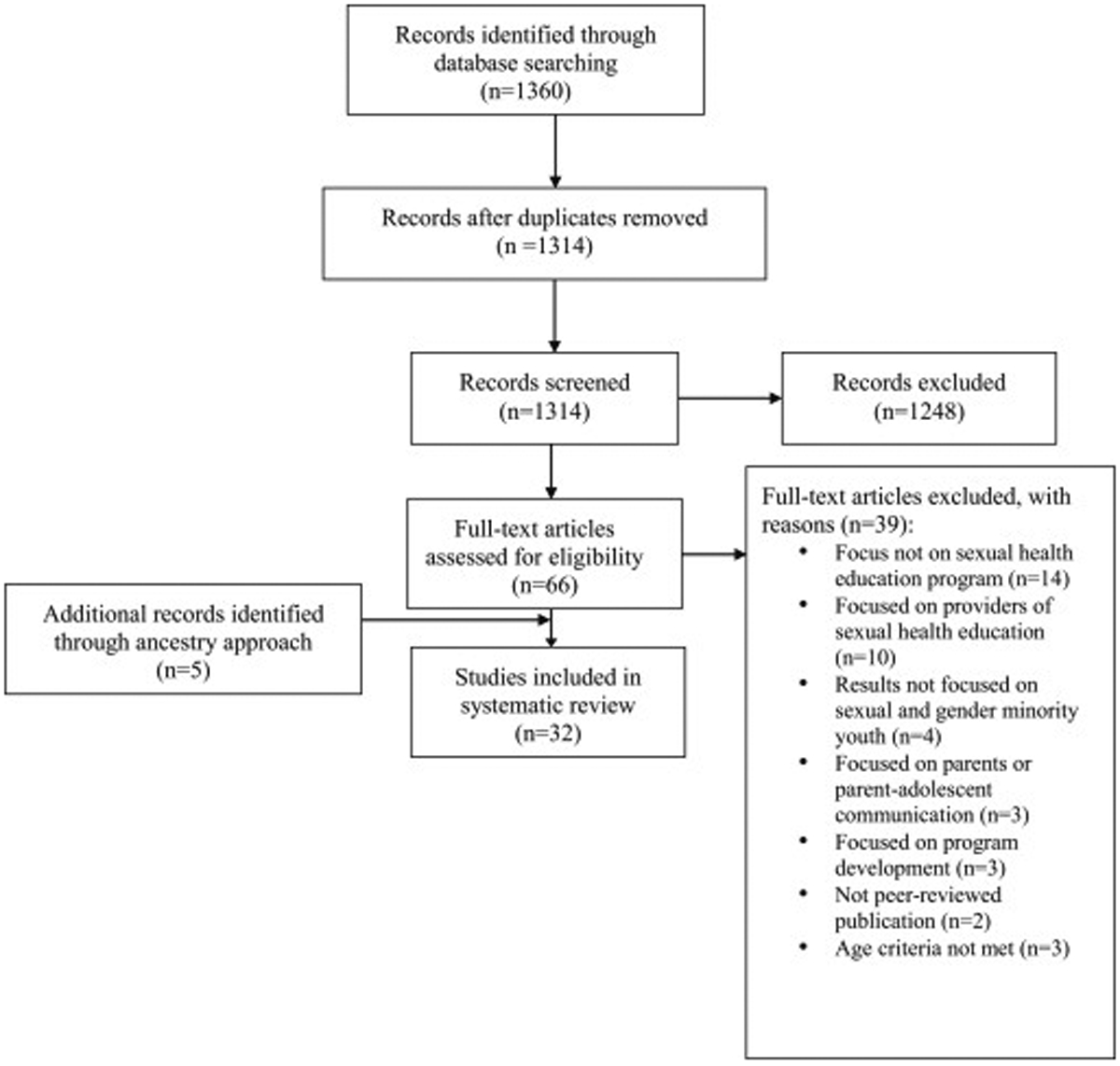

After abstract screening, six authors extracted relevant data from the full text of articles using a standardized abstraction form. The initial database search retrieved 1360 articles (Figure 2). After duplicates were removed, we screened 1314 records for eligibility. Sixty-six records met the criteria for full-text assessment. We identified an additional 5 articles for inclusion by reviewing reference lists. After full-text coding, a total of 32 articles met inclusion criteria, of which 16 examined SGMY’s perspectives on sexual health education, 13 examined the acceptability or effectiveness of sexual health programming designed for SGMY, 1 examined the effectiveness or acceptability of a sexual health education program delivered to a broader sample of youth with results presented for a subsample of SGMY, and 2 cross-sectional studies examining exposure to sexual health education for SGMY. Of the 13 studies examining the acceptability or effectiveness of sexual health programming designed for SGMY, 11 unique interventions were described.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram for inclusion and exclusion of articles

For all included articles, we extracted information regarding study background (e.g., location, study design, sampling strategy), demographic characteristics of the sample (e.g., sexual orientation, gender identity, age, race/ethnicity), and a summary of qualitative and/or quantitative findings. For studies examining SGMY’s perspectives on sexual health education generally, two authors independently extracted key qualitative findings for each study. For studies examining the acceptability or effectiveness of sexual health programming delivered to SGMY exclusively or to general populations of youth, information regarding the development, content, and delivery of the program were extracted, as well as acceptability and effectiveness findings.

We organized results by the three research questions illustrated in Figure 1. When presenting findings in the results, we opted to use the language that the studies themselves used to describe populations of interest (e.g., LGBTQ, SGMY). Study background information for all included studies is summarized in Supplemental File 2. We conducted a thematic analysis of qualitative studies on SGMY’s perspectives on sexual health education using an iterative process of coding the text and creating descriptive and analytical themes to identify key perspectives.15 Using a similar process, we summarized information regarding the development, content, and delivery of sexual health programs delivered to SGMY exclusively or general populations of youth. Finally, we synthesized acceptability and effectiveness findings across these sexual health education programs.

Results

1. What are SGMY’s perspectives on sexual health education?

Study characteristics

Sixteen qualitative studies examined SGMY’s perspectives on sexual health education that took place in various contexts including schools, community organizations, and the House and Ball community (i.e., a kinship system to provide support for young men who have sex with men (YMSM) and transgender persons.)16 The majority of these studies utilized forms of non-probability sampling to recruit participants, including convenience sampling through online advertisements, venue-based recruitment at LGBT service organizations, gay straight alliances (GSAs), House and Ball communities, and universities. Two studies recruited participants from ongoing cohort studies with LGBT youth.17,18 In terms of sample composition, four studies were conducted exclusively with sexual minority males.18–21 Ten studies included both sexual and gender minority youth in their sample.17,22–30 Of these ten studies, 7 studies specified the breakdown of their sample composition in terms of sexual orientation and gender identity and had a minority of gender minority participants17,23,24,26,27,29,30 and three had a sample that was majority sexual minority males.26,29,30 Finally, one study was with LGB young adults31 and another was with leaders of House and Ball communities.32 Five studies specified that they included youth under the age of 1823–26,30 and one study’s sample was primarily “high school aged.”27 Many studies had samples that were majority white (≥50%).20,21,23,24,29,31 One study of YMSM who were recently diagnosed with HIV included a predominately African American sample.19 Some studies restricted eligibility to specific races/ethnicities, including African American youth.28 The full list of themes derived from this literature can be found in Box 1, of which 13 of 16 identified studies directly contributed findings to these themes.

Box 1. Summary of findings on sexual and gender minority youths’ perspectives on sexual health education.

PERSPECTIVES

Sexual health education received at schools excluded information related to SGM identities, including discussions of sexual orientation, sexuality, or gender identity18,21,23,27–29,31

Sexual health education excluded information related to the full spectrum of sexual behaviors18,19,21,23,29

Sexual health education was largely abstinence based23,29,31

Youth felt they did not gain relevant knowledge from sexual health education to protect themselves when engaging in sexual activity18,19,21,24,25,29,31

Youth felt alienated, scared, or uncomfortable during sexual health education18,19,21,23,24,31

Youth wanted instructors teaching sexual health education to be more relatable29,30

Sexual health education relied on “danger discourses” focusing exclusively on STDs, pregnancy, and risk18,21,29,31

When SGM identities were discussed in sexual health education, they were primarily discussed in the context of risk21,23–25,28,29

Sexual health education was often provided after youth had already become sexually active19,28,30,31

Youth wanted sexual health education to include more content on a range of topics, including relationships, dating, psychosocial factors, communication, coercion, questioning one’s sexuality, anatomy17,18,23,25,28–30,32

Youth stressed the importance of keeping sexual health education programming and services confidential30,32

Youth wanted LGBT mentors or role models in sexual health education17,19,30

Many studies suggested content focused exclusively on penis-in-vagina (PIV) sex or heterosexual sex while excluding other sexual acts.18,19,21,23,29 One study with YMSM found that even when sexual behaviors beyond PIV sex were mentioned, such as anal sex, they were typically discussed in the context of heterosexual couples.18 In addition to excluding information on sexual behaviors, information relating to SGM identities, such as discussions of sexual orientation and gender identity, were also excluded.18,21,23,27–29,31 However, two studies found that students were taught basic terminology regarding sexual orientation and gender identity,23,27 such as the definition of “gay”.

Youth reported that their sexual health education provided insufficient knowledge to protect themselves when engaging in sexual activity.18,19,21,24,25,29,31 Knowledge gaps related to STD transmission, pregnancy risk, safe sex practices, condom use, and other barrier protection methods were identified. These gaps varied by subpopulations of SGMY. For example, one study suggested that lesbians and women who primarily had sex with women were not aware of STD and pregnancy risks.24 A number of studies found that SGMY felt alienated, uncomfortable, or scared during sexual health education.18,19,21,23,24,31 Some youth specifically attributed their feelings of isolation and alienation to the lack of content inclusive of their identities and experiences in sexual health education.19,23,24 Some youth described being scared due to a hostile environment where questioning and discussion about SGM topics was not seen as a feasible option.18 In one study of queer youth, youth reported that the sexual health education they received exacerbated their depression and suicidal tendencies.21

Multiple studies indicated that SGMY believed that sexual health education relied on “danger discourses” focusing on risk related to pregnancy and STDs.18,21,29,31 For example, one study of LGB youth indicated their school-based sexual health education was abstinence-based and relied on intimidation tactics, such as a “slideshow of diseases.”31 In addition to a broader focus on risk, multiple studies suggested that if and when SGM identities or same-sex behaviors were discussed, they were primarily discussed in the context of risk.21,23–25,28,29 Specifically, sexual orientation or same-sex sexual behaviors were mentioned in relation to HIV.23–25,28

2. What is the acceptability and effectiveness of sexual health education programs designed for SGMY?

Study characteristics.

Thirteen studies examined the acceptability or effectiveness of sexual health programming designed for SGMY. These studies represent a total of 11 unique interventions, as two sets of studies reported on the same sexual health program (Project Life Skills and Keep it Up!).33–36 Four studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs),36–39 five were pre-post studies with no comparison group,33–35,40,41 two used serial cross sectional surveys,42,43 one used only a post survey,44 and one was a process evaluation with acceptability findings.45 For RCTs, the follow-up time ranged from one month37 to three months.36,38,39

The target population for these interventions was predominately sexual minority males,35–40,42–45 with a few of these focused on subpopulations of sexual minority males, such as one study on rural MSM40 and two studies on black MSM.42,43 Additionally, two studies presented data on the same intervention targeting transgender women33,34 and one intervention targeted LGBT youth broadly.41 Eight studies included youth under the age of 18 in their eligibility criteria.33,34,37–39,41,42,44

Description of interventions

Details regarding the development, content, and delivery of these inclusive sexual health programs are delineated in Box 2. In most cases, individuals who shared characteristics (e.g. race, sexual identity, gender) with the target population participated in program development process,33,34,37,39,42,43,45 through a variety of mechanisms including involvement in formative research to inform an intervention and youth advisory boards. Additionally, some studies adapted content from existing interventions for their target population. For example, the Many Men, Many Voices intervention, targeting black MSM, was adapted to be relevant to YMSM from multiple racial/ethnic backgrounds.45

Box 2. Characteristics of Inclusive Sexual Health Education.

Program development

Program content

Tailored based on demographic profile, values, or risk profile of participants35–37,39–41,44,45

Sexual orientation and gender identity topics (e.g., definitions, coming out)33,34,39,41,43,45

Examples of LGBT individuals/couples or histories/events33–38,40,41

Relationships (e.g., unhealthy vs. healthy relationships)33–36,39–41

Pro-social skills (e.g., communication, negotiation of safe sex)33–36,38,40–43

Risk reduction approaches (e.g., condom use, serosorting)33–36,38–43,45

Coping with minority stress (e.g., discrimination)33,34,38,43,45

Information on a spectrum of sexual behaviors (e.g., oral and anal sex)33,34,39,41

Linkage to medical services (e.g., providing a list of providers for HIV/STD testing)33,34,37,41,42,45

A range of partnerships (e.g., new partners, causal partners, etc.)33–36,40

Information on other relevant aspects of life (e.g., housing, employment)33,34,43

Program delivery

Interventions covered a wide spectrum of topics, including but not limited to information about HIV/STD,33–43,45 HIV/STD testing or treatment,33–37,39,41,42 risk reduction approaches,33–36,38–43,45 and pro-social skills (e.g., healthy communication).33–36,38,40–43 Several interventions included examples of LGBT individuals in program content.33–38,40,41 For example, Project Life Skills, an intervention for transgender women, included a session on transgender pride and profiles of accomplished transgender women.33,34 Furthermore, some interventions specifically attempted to link youth to medical services often by facilitating connections to providers.33,34,37,41,42,45 In addition to didactic components, interventions included interactive strategies including role-playing scenarios, quizzes and games, videos, and audio content.33–45

Several interventions were facilitated by individuals with similar sociodemographic characteristics as the target population.33,34,38,42,43 For example, the Promoting Ovahness Through Safe Sex Education (POSSE) intervention, which primarily targeted black YMSM, had trainers who identified as black, gay men.42

Effectiveness

Effectiveness and acceptability findings are shown in Table 1. Of the 13 identified studies, 12 reported findings about the effectiveness of the intervention. A range of outcomes were examined including those related to behavior (e.g., condom use, HIV/STD testing), knowledge (e.g., HIV related knowledge), skills (e.g., communication skills), and self-efficacy (e.g., self-efficacy for safer sex). Ten studies examined behavioral outcomes, such as number of sexual partners, condom use, and engaging in sex under the influence of alcohol or other substances.33–40,42,43

Table 1.

Acceptability and effectiveness of sexual health programming for sexual and gender minority youth (SGMY)

| Study | Population | Intervention structure | Effectiveness and Acceptability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain #2: Sexual health education delivered to SGMY exclusively | |||

| Bauermeister et al., (2015)37 Baseline n = 130 Follow-up n (at 1 month) = 104 |

Target: YMSM | Intervention: Tailored Get Connected! content Control: Non-tailored, attention control Follow-up: 1 month |

Effectiveness Intended effects:

|

| Bowen et al., (2008)40 Baseline n = 425 Follow-up n (at post-test 3) = 294 |

Target: Rural MSM | Intervention: Wyoming Rural AIDS Prevention Project (WRAPP) Control: N/A Follow-up: average 19 days to complete entire intervention |

Effectiveness Intended effects:

|

| Cotten & Garofalo (2016)33 Baseline n = 51 Follow-up n (at 3 months) = 43 |

Target: Young transgender women | Intervention: Project Life Skills Control: N/A Follow-up: 3 months |

Effectiveness Intended effects:

|

| Garofalo et al., (2012)34 Baseline n = 51 Follow-up n (at 3 months) = 43 |

Target: Young transgender women | Intervention: Life Skills Control: N/A Follow-up: 3 months |

Effectiveness Intended effects:

|

| Greene et al., (2016)35 Baseline n = 343 Follow-up n = 200 (at 12-weeks) |

Target: YMSM | Intervention: Keep It Up! 1.5 (KIU!) Control: N/A Follow-up: 12-week |

Effectiveness Intended effects:

|

| Hidalgo et al., (2015)38 Baseline n = 101 Any follow-up n = 75 |

Target: YMSM | Intervention: Male Youth Pursuing Empowerment, Education, and Prevention around Sexuality (MyPEEPS) Control: non-interactive, time-matched, lecture-based program Follow-up: 6 and 12-weeks |

Effectiveness Intended effects: Compared to the active control at overall follow-up, participants

|

| Hosek et al., (2013)45 n = 58 |

Target: YMSM | Intervention: Project PrEPare Control: N/A Follow-up: N/A |

Effectiveness N/A Acceptability

|

| Hosek et al., (2015)42 Overall n = 406 |

Target: Black YMSM in the House Ball Community | Intervention: Promoting Ovahness through Safer Sex Education (POSSE) Control: N/A Follow-up: 3, 6, 9, and 12 months (serial cross-sectional) |

Effectiveness Intended effects:

None Null effects:

|

| Jones et al., (2008)43 Overall n = 1190 |

Target: Black MSM | Intervention: Peer-delivered HIV education Control: N/A Follow-up: 3 equally spaced cross-sectional surveys after baseline (serial cross-sectional) |

Effectiveness Intended effects:

N/A |

| Mustanski et al., (2013)36 Baseline n = 102 Follow-up n (at 12 weeks) = 90 |

Target: YMSM | Intervention: Keep it Up! (KIU!) Control condition: online didactic HIV knowledge condition Follow-up: 6 week and 12 weeks |

Effectiveness Intended effects:

|

| Mustanski et al., (2015)41 Baseline n = 276 Follow-up n (completed post-test) = 202 |

Target: LGBT youth | Intervention: Queer Sex Ed (QSE) Control: N/A Follow-up: 2 weeks |

Effectiveness Intended effects:

|

| Ybarra et al., (2014)44 Overall n = 75 |

Target: GBQ adolescent males | Intervention: Focus groups about GBQ sexual health related topics Control: N/A Follow-up: NA (cross-sectional) |

Effectiveness Intended effects: Sexually experienced participants

|

| Ybarra et al., (2017)39 Baseline n = 302 Follow-up n (90-days postintervention) = 283 |

Target: Adolescent gay, bisexual, and queer men | Intervention: GUY2Guy Control: attention-matched healthy lifestyle control Follow-up: End of intervention (36 days from baseline), 90 days |

Effectiveness Intended effects:

N/A |

| Domain #3: Sexual health education delivered to broader samples of youth with subsamples of SGMY | |||

| Widman et al., (2017)46 n = 107 (intervention condition only) |

Target: adolescent girls, results stratified by sexual orientation | Intervention: Health Education and Relationship Training (HEART) Control: N/A Follow-up: NA (cross-sectional) |

Effectiveness N/A Acceptability

|

Young men who have sex with men (YMSM), men who have sex with men (MSM), gay, bisexual, queer (GBQ), receptive anal intercourse (RAI), unprotected receptive anal intercourse (URAI), insertive anal intercourse (IAS), IAI (insertive anal intercourse), unprotected insertive anal intercourse (UIAI), condomless vaginal or anal intercourse (CVAI), opinion leaders (OL), condomless anal intercourse (CAI), condomless anal sex (CAS), unprotected anal intercourse (UAI), unprotected anal sex (UAS), sexually transmitted infection (STI), sexually transmitted disease (STD), HIV (human immunodeficiency virus), acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender)

Ten studies, including 4 RCTs and 6 quasi-experimental or non-experimental studies, specifically examined condom use outcomes. Of the studies examining condom use, among the RCTs, 2 out of 4 studies found the intervention had an intended effect on at least one condom use related outcome, including unprotected sex under the influence of alcohol/drugs38 and total unprotected anal sex acts.36 In contrast, Guy2Guy, an intervention for adolescent gay, bisexual, and queer men, reported a null effect on condomless sex acts.39 Similarly, Get Connected!, an HIV/STI testing intervention for young men who have sex with men, had a null effect on the number of unprotected receptive and insertive anal intercourse partners.37 Of the 6 studies using quasi-experimental and non-experimental study designs examining condom use outcomes, 5 reported at least one intended effect on condom use, including decreases in number of unprotected receptive anal intercourse encounters with causal sex partners,34 condom errors and failure,35 and condomless anal intercourse with unknown HIV status male partners,42 frequency of anal sex per number of sex partners,40 and an increase in condom use for receptive anal sex.43 In a feasibility trial of Project Life Skills, an HIV prevention curriculum for young transgender women, the number of unprotected receptive anal sex encounters decreased but was not statistically significant.33

Several studies examined knowledge-related outcomes. One RCT examined HIV knowledge as an outcome and reported a null effect in HIV knowledge, although both arms increased in HIV knoweldge.36 Of the three studies using quasi-experimental and non-experimental study designs examining HIV knowledge related outcomes, all reported an increase in knowledge.35,40,41

Acceptability

Of the thirteen intervention studies, eleven reported findings about the acceptability of the intervention. Across studies, acceptability was operationalized differently, considering sub-constructs such as willingness to recommend the intervention and participants’ perceptions of specific intervention components. Overall, all eleven studies reported that the interventions were either highly or moderately acceptable to youth. Across studies, some factors reducing the acceptability of interventions included the length of specific modules and the intervention overall, technology issues, having to travel significant distance to attend the intervention, and the pacing and repetition of content. Some factors contributing to the acceptability of interventions included the interactivity of content, booster activities, inclusion of realistic scenarios, and relational aspects (e.g., meeting new people). One study examined acceptability findings by sexual experience.44 Ybarra et al.44 found that focus groups of both sexually experienced and inexperienced gay, bisexual, and queer adolescent male participants rated the program as acceptable.

3. What is the acceptability and effectiveness of sexual health education programs delivered to broader samples of youth with subsamples of SGMY?

Only one study examined the effectiveness or acceptability of a sexual health education program delivered to a broader sample of youth with results presented for a subsample of SGMY. The Health Education and Relationship Training (HEART) intervention was delivered to adolescent girls and the intervention was highly acceptable, as 95% liked and learned from the program.46 The majority of acceptability results did not vary by sexual orientation.46

Two secondary analyses examining exposure to sexual health education for SGMY were identified. One study using data from the 1995 Massachusetts Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) found that gay, lesbian, and bisexual (GLB) students who were exposed to instructor-reported, gay-sensitive HIV instruction reported fewer sexual partners, less recent sex, and less substance use before sex than did GLB students in schools without gay-sensitive HIV instruction.47 Additionally, a study of YMSM found that those who received sex education courses were less likely to report non-concordant unprotected anal intercourse and a new HIV/STD diagnosis, with some variation depending on if the sex education was received in middle or high school.48

Discussion

SGMY are at risk for compromised sexual and reproductive health. In recent years, scholars and advocates have acknowledged that SGMY have been invisible in adolescent sexual health education, and have called for U.S. adolescent sexual and reproductive health education to be inclusive of sexual and gender minorities.49 Through a systematic literature search we identified 32 published articles addressing our three research questions (Figure 1). Our findings highlight the breadth of research concerning sexual health education for SGMY. Taken together, a number of key research and programmatic priorities emerged to advance sexual health education programming to meet the needs of SGMY.

Diverse studies examined SGMY perspectives on sexual health education. Collectively, these studies indicate that SGMY lacked relevant content in their sexual health education, including information on same-sex sexual behaviors, sexual orientation, and gender identity. In addition to exclusions, SGMY described instances when their identities and their sexual behaviors were pathologized,21,23–25,28,29 often in the case of linking HIV to sexual orientation or same-sex sexual behaviors. Perhaps due to these exclusions and negative representations, SGMY reported feelings of alienation and mental health challenges in relation to their sexual health education experiences.18,19,21,23,24,31 Although we did not identify any studies explicitly linking inclusion/exclusion of SGM topics with student-level mental health, a recent study offers preliminary evidence that states where more schools teach LGBT-inclusive sex education, youth have lower odds of adverse mental health outcomes.14 Consistent with studies of broader samples,50 SGMY also reported negative perceptions of abstinence-based education. Finally, several studies with SGMY highlighted a need for sexual health education to be more comprehensive and cover a broader set of topics, including communication and healthy relationships.

There were a surprising number of tested sexual health education interventions designed for SGMY, most of which had intended effects on sexuality-related behavior, knowledge, or self-efficacy. The majority of these were designed for sexual minority males and focused primarily on HIV prevention, and none of these interventions were school-based. It is promising that several sexual health education interventions for SGMY included content on a broader set of topics, including healthy relationships, communication, and social skills, aligned with what SGMY stated they desired. This is in accordance with National Sex Education Standards which stress the importance of teaching youth about consent and characteristics of healthy and unhealthy relationships.51 Given the heightened prevalence of intimate partner violence found among sexual and gender minority populations,52 efforts to make sexual health education more inclusive may also require integration of dating violence prevention. However, comprehensive sexuality education programs including content on the full range of sexual and reproductive health topics were sparse. For example, despite calls for integrating STD/HIV prevention messaging with unintended pregnancy prevention,53 few interventions included content on contraception and pregnancy prevention, perhaps due to the primary population of focus being sexual minority males. Nonetheless, sexual minority girls are at a heightened risk of experiencing teen pregnancies54 and are often unaware of STD and pregnancy risks.24

Through synthesizing sexual health education interventions developed for SGMY, key components of inclusivity pertinent to program development, content, and delivery emerged. Many interventions were developed with the input and participation of SGMY themselves and, thus, as we would expect, there seemed to be a narrowing of the gap between what youth desired and what youth received. Indeed, the shortcomings youth identified in qualitative studies of their sexual health education experiences were addressed in many of these interventions designed for SGMY through intentional inclusion of a breadth of topics, including but not limited to healthy communication and relationships, health services, and specific approaches to risk reduction. Specifically in relation to delivery, the importance of having relatable individuals (i.e., in relation to sexual orientation, gender identity, age, race/ethnicity, etc.) deliver program content repeatedly emerged as critical. Although there has been mixed evidence regarding the effectiveness of peer-led sexual health education,55 an important shortcoming of this body of research is the definition of peer itself, which has consistently only focused on age whereas other identities, such as sexual orientation and gender identity, may be more salient for SGMY.

Across these domains of literature, some key gaps emerged. The majority of studies focused on sexual minority males and high-school aged youth or young adults, leaving a paucity of studies with younger adolescents, sexual minority girls, and gender minority youth. Another notable gap is the lack of focus on transgender health. There were two studies on the HIV prevention intervention Project Life Skills for transgender women. However, most interventions either explicitly required being cisgender as an inclusion criteria, had a minority of transgender participants, or did not present demographic data in relation to gender identity, underscoring the lack of sexual health education interventions for transgender youth. While it is reassuring that the inclusive sexual health programs we identified covered a broader set of topics, there were very few examples of understanding the experiences of SGMY in the context of universal or general population sexual health education efforts. In fact, we only identified one sexual health education intervention that was delivered to a general population of youth in a school setting and presented results for SGMY. Although this specific intervention, Health Education and Relationship Training (HEART), was found to be acceptable to both sexual minority and majority girls,46 a seemingly unexplored area of research is the acceptability and effectiveness for SGMY of specific sexual health education programs delivered to all youth in schools. Given that schools are one of the main sources of sexual health information for youth,56 incorporating and testing efforts to make sexual health education inclusive in more universal settings, such as schools, is an important next step. Doing so will require a larger examination of the barriers and facilitators to incorporating inclusive sexual health education in schools. Implementation studies are needed in order to improve schools’ uptake of the identified programs which have been delivered in community and online settings to date. In addition to identifying implementation barriers specific to schools, addressing broader structural challenges to conducting research with SGMY is imperative. One structural barrier which has received recent attention is the requirement by institutional review boards (IRBs) for parental permission from adolescents to participate in HIV prevention programs,57 despite potential risks to youth who may not have disclosed their sexual identity to their parents, as well as research indicating that sexual minority youth whose parents are unaware of their sexual orientation may refuse to participate in research if parental permission is required.58

Our review is subject to limitations. Although we used a systematic approach, our search was not exhaustive and relevant articles may not have been captured. In particular, it is possible that by relying on SGM-related search terms we may not have captured relevant studies where the primary focus was general populations of youth and there was a secondary focus on SGMY. Due to significant heterogeneity in intervention content, study design, and outcomes examined, we were unable to meta-analyze the results from the sexual health education interventions. Three studies did not sufficiently describe the age of their sample to obtain the mean or exact age distribution but other details in their study descriptions suggest they recruited mainly youth and were thus included in this review.22,27,32 Finally, it is worth noting that a number of biomedical interventions with a specific focus on raising awareness and use of a specific health service (e.g., HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)) were not in the scope of this review, which focused on sexual health education more broadly.

Nonetheless, we provide a state-of-the-field summary of sexual health education efforts for SGMY. The nearly two decades of research we synthesize has laid the foundation for future programmatic and research efforts to make sexual health education more inclusive. The need for inclusivity is well-established; however, how to provide inclusivity is less understood. Importantly, the call for inclusive sexual health education is not a call for education in addition to what is available, but rather an adjustment of already existing programs and strategies to be inclusive of and relevant for all youth. For example, the National HIV/AIDS Strategy, which aims to reduce new HIV infections, recommends age-appropriate HIV and STI prevention education for youth.59 Moving forward, ensuring that such education efforts are intentional in their inclusivity of SGMY is crucial.

Future research should aim to rigorously test the acceptability and effectiveness of inclusive sexual health education programming, elucidating its key elements in relation to development, content, and delivery. Understanding the effectiveness of such programs in general population settings (e.g., schools) is imperative for clarifying that inclusivity is beneficial for all youth. To that end, incorporating SGMY populations that have been underrepresented in existing research—sexual minority girls, transgender youth, and younger adolescents—will allow for a more nuanced understanding of whether these programs are truly inclusive of all youth. Although the body of research regarding sexual minority males’ experiences with sexual health education is robust, there may be a need for more formative work with aforementioned unrepresented populations to understand their experiences with sexual health education. Finally, coupling outcome evaluations with thorough examinations of the implementation process, including understanding barriers and facilitation to implementation of programs, is essential for program scale-up.

Supplementary Material

Implications and Contribution.

This review synthesizes the diverse body of literature on sexual and gender minority youth and sexual health education. Future research should aim to include underrepresented populations (younger adolescents, sexual minority girls, and transgender persons) and test the effectiveness of inclusive sexual education in general population settings (e.g., schools).

Acknowledgments

Findings from this study were presented at the 2018 Society for Research on Adolescence biennial meeting. The authors would like to thank Paula Jayne for her formative research, which informed this review. This research was supported by grant P2CHD042849 and T32HD007081 awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. This research was also supported in part by the National Institute of Mental Health through a grant awarded to Allen B. Mallory grant number F31MH115608.

Abbreviations:

- YMSM

Young men who have sex with men

- MSM

men who have sex with men

- GBQ

gay, bisexual, queer

- RAI

receptive anal intercourse

- URAI

unprotected receptive anal intercourse

- IAS

insertive anal intercourse

- IAI

insertive anal intercourse

- UIAI

unprotected insertive anal intercourse

- CVAI

condomless vaginal or anal intercourse

- OL

opinion leaders

- CAI

condomless anal intercourse

- CAS

condomless anal sex

- UAI

unprotected anal intercourse

- UAS

unprotected anal sex

- STI

sexually transmitted infection

- STD

sexually transmitted disease

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- AIDS

acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- LGBT

lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention nor the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Baral SD, Poteat T, Strömdahl S, Wirtz AL, Guadamuz TE, Beyrer C. Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(3):214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saewyc EM. Adolescent pregnancy among lesbian, gay, and bisexual teens. In: International handbook of adolescent pregnancy. Springer; 2014:159–169. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2018 (Updated); vol 31. 2020; https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2018-updated-vol-31.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2020.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2018. 2019; https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/STDSurveillance2018-full-report.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2020.

- 5.Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2017. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Surveill Summ. 2018;67(8):1–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johns MM, Lowry R, Andrzejewski J, et al. Transgender Identity and Experiences of Violence Victimization, Substance Use, Suicide Risk, and Sexual Risk Behaviors Among High School Students—19 States and Large Urban School Districts, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(3):67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirby DB, Laris B, Rolleri LA. Sex and HIV education programs: their impact on sexual behaviors of young people throughout the world. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(3):206–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Developing a Scope and Sequence for Sexual Health Education. 2016; https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/hecat/pdf/scope_and_sequence.pdf. Accessed May 23, 2019.

- 9.Chin HB, Sipe TA, Elder R, et al. The effectiveness of group-based comprehensive risk-reduction and abstinence education interventions to prevent or reduce the risk of adolescent pregnancy, human immunodeficiency virus, and sexually transmitted infections: two systematic reviews for the Guide to Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(3):272–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirby D The impact of abstinence and comprehensive sex and STD/HIV education programs on adolescent sexual behavior. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2008;5(3):18. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Zongrone AD, Clark CM, Truong NL. The 2017 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth in Our Nation’s Schools. ERIC; 2018.

- 12.Guttmacher Institute. Sex and HIV Education. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/sex-and-hiv-education. Accessed August 2, 2020.

- 13.GLSEN. Laws that Prohibit the “Promotion of Homosexuality”: Impacts and Implications. New York: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Proulx CN, Coulter RW, Egan JE, Matthews DD, Mair C. Associations of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning–Inclusive Sex Education With Mental Health Outcomes and School-Based Victimization in US High School Students. J Adolesc Health. 2019;64(5):608–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sterling T, Stanley R, Thompson D, et al. HIV-related tuberculosis in a transgender network-Baltimore, Maryland, and New York City area, 1998–2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49(15):317–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greene GJ, Fisher KA, Kuper L, Andrews R, Mustanski B. “Is this normal? Is this not normal? There is no set example”: Sexual health intervention preferences of LGBT youth in romantic relationships. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2015;12(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kubicek K, Beyer WJ, Weiss G, Iverson E, Kipke MD. In the dark: young men’s stories of sexual initiation in the absence of relevant sexual health information. Health Educ Behav. 2010;37(2):243–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flores D, Blake BJ, Sowell RL. “Get them while they’re young”: Reflections of young gay men newly diagnosed with HIV infection. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2011;22(5):376–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mutchler MG. Making space for safer sex. AIDS Educ Prev. 2000;12(1):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher CM. Queer Youth Experiences with Abstinence-Only-until-Marriage Sexuality Education: “I Can’t Get Married so where Does that Leave Me?”. J LGBT Youth. 2009;6(1):61–79. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arnold EA, Bailey MM. Constructing home and family: How the ballroom community supports African American GLBTQ youth in the face of HIV/AIDS. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2009;21(2–3):171–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gowen L, Winges-Yanez N. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning youths’ perspectives of inclusive school-based sexuality education. J Sex Res. 2014;51(7):788–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinke J, Root-Bowman M, Estabrook S, Levine DS, Kantor LM. Meeting the needs of sexual and gender minority youth: Formative research on potential digital health interventions. J Adolesc Health. 2017:541–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linville D More than Bodies: Protecting the Health and Safety of LGBTQ Youth. Policy Futures Educ. 2011;9(3):416–430. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brockenbrough E Becoming queerly responsive: Culturally responsive pedagogy for Black and Latino urban queer youth. Urban Educ. 2016;51(2):170–196. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snapp SD, Burdge H, Licona AC, Moody RL, Russell ST. Students’ perspectives on LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum. Equity & Excellence in Education. 2015;48(2):249–265. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rose ID, Friedman DB. Schools: A missed opportunity to inform African American sexual and gender minority youth about sexual health education and services. J Sch Nurs. 2017;33(2):109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pingel ES, Thomas L, Harmell C, Bauermeister JA. Creating comprehensive, youth centered, culturally appropriate sex education: What do young gay, bisexual, and questioning men want? Sex Res Soc Policy. 2013;10(4):293–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seal DW, Kelly J, Bloom F, Stevenson L, Coley B, Broyles L. HIV prevention with young men who have sex with men: What young men themselves say is needed. AIDS Care. 2000;12(1):5–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Estes ML. “If there’s one benefit, you’re not going to get pregnant”: The sexual miseducation of gay, lesbian, and bisexual individuals. Sex Roles. 2017;77(9–10):615–627. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holloway IW, Traube DE, Kubicek K, Supan J, Weiss G, Kipke MD. HIV prevention service utilization in the Los Angeles House and Ball communities: past experiences and recommendations for the future. AIDS Educ Prev. 2012;24(5):431–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cotten C, Garofalo R. Project life skills: Developing the content of a multidimensional HIV-prevention curriculum for young transgender women aged 16 to 24. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv. 2016;15(1):99–113. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garofalo R, Johnson AK, Kuhns LM, Cotten C, Joseph H, Margolis A. Life skills: evaluation of a theory-driven behavioral HIV prevention intervention for young transgender women. Journal of Urban Health. 2012;89(3):419–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greene GJ, Madkins K, Andrews K, Dispenza J, Mustanski B. Implementation and Evaluation of the Keep It Up! Online HIV Prevention Intervention in a Community-Based Setting. AIDS Educ Prev. 2016;28(3):231–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mustanski B, Garofalo R, Monahan C, Gratzer B, Andrews R. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of an online HIV prevention program for diverse young men who have sex with men: the keep it up! intervention. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(9):2999–3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bauermeister JA, Pingel ES, Jadwin-Cakmak L, et al. Acceptability and preliminary efficacy of a tailored online HIV/STI testing intervention for young men who have sex with men: the Get Connected! program. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(10):1860–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hidalgo MA, Kuhns LM, Hotton AL, Johnson AK, Mustanski B, Garofalo R. The MyPEEPS randomized controlled trial: A pilot of preliminary efficacy, feasibility, and acceptability of a group-level, HIV risk reduction intervention for young men who have sex with men. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44(2):475–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ybarra ML, Prescott TL, Phillips Ii GL, Bull SS, Parsons JT, Mustanski B. Pilot RCT Results of an mHealth HIV Prevention Program for Sexual Minority Male Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bowen AM, Williams ML, Daniel CM, Clayton S. Internet based HIV prevention research targeting rural MSM: feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy. J Behav Med. 2008;31(6):463–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mustanski B, Greene GJ, Ryan D, Whitton SW. Feasibility, acceptability, and initial efficacy of an online sexual health promotion program for LGBT youth: The Queer Sex Ed intervention. J Sex Res. 2015;52(2):220–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hosek SG, Lemos D, Hotton AL, et al. An HIV intervention tailored for black young men who have sex with men in the House Ball Community. AIDS Care. 2015;27(3):355–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones KT, Gray P, Whiteside YO, et al. Evaluation of an HIV prevention intervention adapted for Black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(6):1043–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ybarra ML, DuBois L, Parsons JT, Prescott TL, Mustanski B. Online focus groups as an HIV prevention program for gay, bisexual, and queer adolescent males. AIDS Educ Prev. 2014;26(6):554–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hosek SG, Green KR, Siberry G, et al. Integrating Behavioral HIV Interventions Into Biomedical Prevention Trials With Youth: Lessons From Chicago’s Project PrEPare…Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv. 2013;12(3–4):333–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Widman L, Golin CE, Kamke K, Massey J, Prinstein MJ. Feasibility and acceptability of a web-based HIV/STD prevention program for adolescent girls targeting sexual communication skills. Health Educ Res. 2017;32(4):343–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blake SM, Ledsky R, Lehman T, Goodenow C, Sawyer R, Hack T. Preventing sexual risk behaviors among gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents: The benefits of gay-sensitive HIV instruction in schools. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(6):940–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Glick SN, Golden MR. Early male partnership patterns, social support, and sexual risk behavior among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(8):1466–1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schalet AT, Santelli JS, Russell ST, et al. Invited Commentary: Broadening the Evidence for Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health and Education in the United States. J Youth Adolesc. 2014;43(10):1595–1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Santelli JS, Kantor LM, Grilo SA, et al. Abstinence-only-until-marriage: An updated review of US policies and programs and their impact. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61(3):273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Future of Sex Education Initiative. National Sex Education Standards: Core Content and Skills, K-12 (Second Edition). 2020; https://siecus.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/NSES-2020-2.pdf. Accessed July 14, 2020.

- 52.Decker M, Littleton HL, Edwards KM. An updated review of the literature on LGBTQ+ intimate partner violence. Current sexual health reports. 2018;10(4):265–272. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steiner RJ, Liddon N, Swartzendruber AL, Pazol K, Sales JM. Moving the message beyond the methods: toward integration of unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection/HIV prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(3):440–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Charlton BM, Corliss HL, Missmer SA, Rosario M, Spiegelman D, Austin SB. Sexual orientation differences in teen pregnancy and hormonal contraceptive use: an examination across 2 generations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(3):204–e201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim CR, Free C. Recent evaluations of the peer-led approach in adolescent sexual health education: A systematic review. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2008;40(3):144–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Donaldson AA, Lindberg LD, Ellen JM, Marcell AV. Receipt of sexual health information from parents, teachers, and healthcare providers by sexually experienced US adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(2):235–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mustanski B, Fisher CB. HIV rates are increasing in gay/bisexual teens: IRB barriers to research must be resolved to bend the curve. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(2):249–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mustanski B Ethical and regulatory issues with conducting sexuality research with LGBT adolescents: A call to action for a scientifically informed approach. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;40(4):673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.The White House Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States. 2020; https://files.hiv.gov/s3fs-public/nhas-update.pdf. Accessed March 18, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.