Abstract

Aim

Cerebral ischemic injury is one of the debilitating diseases showing that inflammation plays an important role in worsening ischemic damage. Therefore, studying the effects of some potential anti-inflammatory compounds can be very important in the treatment of cerebral ischemic injury.

Methods

This study investigated anti-inflammatory effects of triblock copolymer nanomicelles loaded with curcumin (abbreviated as NC) in the brain of rats following transient cerebral ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury in stroke. After preparation of NC, their protective effects against bilateral common carotid artery occlusion (BCCAO) were explored by different techniques. Concentrations of free curcumin (C) and NC in liver, kidney, brain, and heart organs, as well as in plasma, were measured using a spectrofluorometer. Western blot analysis was then used to measure NF-κB-p65 protein expression levels. Also, ELISA assay was used to examine the level of cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α. Lipid peroxidation levels were assessed using MDA assay and H&E staining was used for histopathological examination of the hippocampus tissue sections.

Results

The results showed a higher level of NC compared to C in plasma and organs including the brain, heart, and kidneys. Significant upregulation of NF-κB, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α expressions compared to control was observed in rats after induction of I/R, which leads to an increase in inflammation. However, NC was able to downregulate significantly the level of these inflammatory cytokines compared to C. Also, the level of lipid peroxidation in pre-treated rats with 80mg/kg NC was significantly reduced.

Conclusion

Our findings in the current study demonstrate a therapeutic effect of NC in an animal model of cerebral ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury in stroke through the downregulation of NF-κB-p65 protein and inflammatory cytokines.

Keywords: ischemia-reperfusion injury, stroke, NF-ĸB, inflammation, curcumin, nanomicelle, rat

Introduction

Stroke is currently the second leading cause of death and long-term disability in developed countries and its trend is on the rise.1,2 About 85% of strokes are caused by ischemia, which results from thrombosis, embolism, and decreased systemic blood flow.3 Delayed improvement in blood flow due to the activation of the oxidative stress process causes greater damage than the initial damage, which leads to endothelial dysfunction, capillary obstruction, damage to tissue and oxygen supply, followed by blood–brain barrier disruption, and cerebral edema.4 At present, despite the significant information available in stroke prevention, there are fewer options for treatment, and the gold standard for the treatment of stroke is intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (IV r-TPA), which can restore brain function only up to about 4 to 5 hrs after stroke. Therefore, it can be used only in 2–4% of patients with stroke.5 It is very important to restore blood flow in I/R-affected areas of the brain by thrombolysis, which causes the clots to dissolve rapidly.6 Although this type of treatment reduces the apoptosis of neuronal cells, it induces inflammatory responses that lead to oxidative and inflammatory damage.7 Therefore, finding novel treatment strategies to reduce this type of oxidative and inflammatory damage in cerebral I/R conditions is very important.8

Therefore, the aim of the current study was to investigate the protective effects of NC on brain damage induced by cerebral I/R injury as well as its effects on the inflammatory response of the NF- ĸB pathway.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of C-Loaded Nanomicelles

PLA-PEG-PLA, PLA average Mn 1500, PEG average Mn 900, average Mn ~2000 was purchased from Sigma Co. (USA). The PLA-PEG-PLA polymers precipitated above 60 mg/mL; therefore, we prepared samples of 50 mg/mL, which is also above the critical micelle concentration (CMC). The preparation of C-loaded nanomicelles was done based on using the thin film hydration method.26 Briefly, stock solutions of PLA-PEG-PLA (50 mg/mL) and curcumin (10 mg/mL) in ethanol were prepared. These solutions were then transferred into vials and ethanol was subsequently evaporated employing a heat gun. Afterward, the vials were dried at 50 °C in a vacuum oven and the formed layers were rehydrated with distilled water and used for further characterization techniques. The obtained solutions were vortexed for 2 min, centrifuged (2500 rpm for 15 min), and the supernatant was utilized in further experiments.

Characterization of NCs

The diameter of nanomicelles was evaluated by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA). The size and zeta potential of nanomicelles and NC were determined using Zetasizer Nano ZS (model ZEN 3600; Malvern Instruments, Inc., Malvern, UK) at room temperature.

Analysis of Curcumin Loading

To measure encapsulation efficiency (EE) of C in nano micelles, the NC was resuspended in distilled water to have a final concentration of 10 mg/mL of a PLA-PEG-PLA and 2 mg/mL of curcumin. The solution was further centrifuged (2500 rpm for 15 min) and 50 µL of the final solution was added by 450 µL of ethanol and measured by UV–vis spectrophotometry at λmax of 420nm using the following equation:

|

(1) |

Curcumin Release in vitro

After NC preparation and centrifugation, the supernatants of rehydrated samples were transferred into dialysis bags (MINI Dialysis Units, 3.5 cut-off MWCO). The bags were then placed in a medium containing 2 mL of PBS (pH: 7.4). Then, 50 µL of the medium was removed and the same amount was replaced by PBS to ensure the sink condition. Finally, the C release from NC was quantified by UV-vis spectrophotometry at λmax of 420nm.

Experimental Protocols and Groups

Forty-eight adult male Wistar rats, weighing 200–220g (aged 4–5 weeks), were prepared by the neurology department, Wuhan University of Science and Technology, China. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee at Wuhan University. All animals were kept in standard laboratory conditions (temperature: 24°C±1°C, humidity: 55%±10%, lighting: 12‐h light/dark cycle), and they had access to food and water freely all the time during this study (Animal Welfare Regulations (USDA 1985; US Code, 42 USC § 289d)).

The rats were randomly divided into 6 groups, as follows:

The control group received normal saline solution.

The stroke group received normal saline solution.

The stroke group received nanomicelles.

The stroke group received curcumin 80mg/kg (C80mg/kg) dissolved in drinking water.

The stroke group received triblock copolymer nanomicelles loaded with curcumin 80mg/kg (NC80mg/kg).

The stroke group received triblock copolymer nanomicelles loaded with curcumin 40mg/kg (NC40mg/kg).

Groups 3–6 were treated orally through gavage with nanomicelles, C and NC for 14 days; 24 h after the last gavage, the stroke was induced.

Plasma and Tissue Distribution of NC

After administration of the last dose of C or NC in the studied rats, blood samples were taken by heart puncture at 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 24, 48, and 72 h to measure the plasma concentrations of C and NC. After centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 min, plasma C and NC concentrations were determined by spectrofluorometry with excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 and 590nm, respectively.

Concentrations of C and NC in the liver, kidneys, brain, and heart were also measured. For this purpose, the rats were killed 24 h after the last dose of C and NC administration and the organs were isolated and washed with PBS and then lysed and homogenized. The tissue homogenate was treated with acidified isopropanol to extract C and NC and, after centrifugation, the supernatant was analyzed by spectrofluorometer.

BCCAO Induction

For inducing stroke by bilateral common carotid artery occlusion (BCCAO), rats were anesthetized by injection of ketamine (50mg/kg) and xylazine (2–8mg/kg) intraperitoneally (i.p). Then, the animals' tails and paws were fixed using adhesive tape. Sagittal incisions were made through the neck midline (1 cm length), then the bilateral common carotid arteries were revealed, and both carotid arteries were carefully separated from the respective vagal nerve. Avoiding any manipulation of the vagal nerve was crucial. A 5-0 silk suture loop was made around each common carotid artery. Both common carotid arteries were occluded for 30 min by tightening the silk sutures. Then, a 72-h reperfusion period was initiated. Afterward, the wounds were sutured. Finally, the rats were returned to their cages and brain sample collection based on ethical protocols and biochemical assays (ELISA kit-sigma Aldrich) were done after 72 h.

Western Blot Analysis

Brain tissue isolated from rats, after rinsing with a cold PBS buffer, was crushed and homogenized in a microtubule with 1 mL RIPA (radioimmunoprecipitation assay) buffer (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and in 1% protease inhibitor (Sigma) in a homogenizer device. After centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 15 min, the supernatant was collected and the protein concentration was determined using a BCA kit (Thermo, Pierce, USA). 60μg total protein was electrophoresed on 10% polyacrylamide gel at a constant voltage of 80V for 35 min and then 120V for 45 min. The electrophoresed proteins were then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) paper and incubated with NF-κB-p65 (Cell Signaling, USA) and beta-actin (β-actin) monoclonal antibodies at 4°C overnight. PBST solution containing 0.1% Tween-20 was used to wash the membrane and then HRP-Rabbit anti-rat secondary antibody (1:10,000) against the primary antibody was incubated on the shaker for 190 min and then washed again. Finally, by adding chemiluminescence ECL (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) to the PVDF paper, the presence of NF-κB-p65 protein in the samples was investigated. In addition to the samples, the negative control sample (without primary antibodies) was also electrophoresed with the same concentration of proteins. Western blot test results were analyzed using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The rats were killed under deep anesthesia, then their brains were removed and stored at −80°C for biochemical assays. The animals’ brains were homogenized in a buffer (TRIS HCL, SDS, DTT, NP40, and glycerol), and centrifuged for 5 min. ELISA kits (Siemens AG, Siemensdamm, Germany) were used to evaluate the levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 cytokine in the rat brain tissue samples.

MDA Assay

The Rao et al method was used to measure the amount of MDA27 by thiobarbituric acid (TBA). For this purpose, rat brain tissue samples were first centrifuged at 2000g for 5 min. Then, 100μL of the supernatant along with 900μL of distilled water was added to the test tube and 500μL of TBA reagent was placed in a boiling water bath for 60 min, after which the tubes were centrifuged again at 4000g for 10 min. Finally, the adsorption of the supernatant was read at 534nm using a spectrophotometer (UV1600).

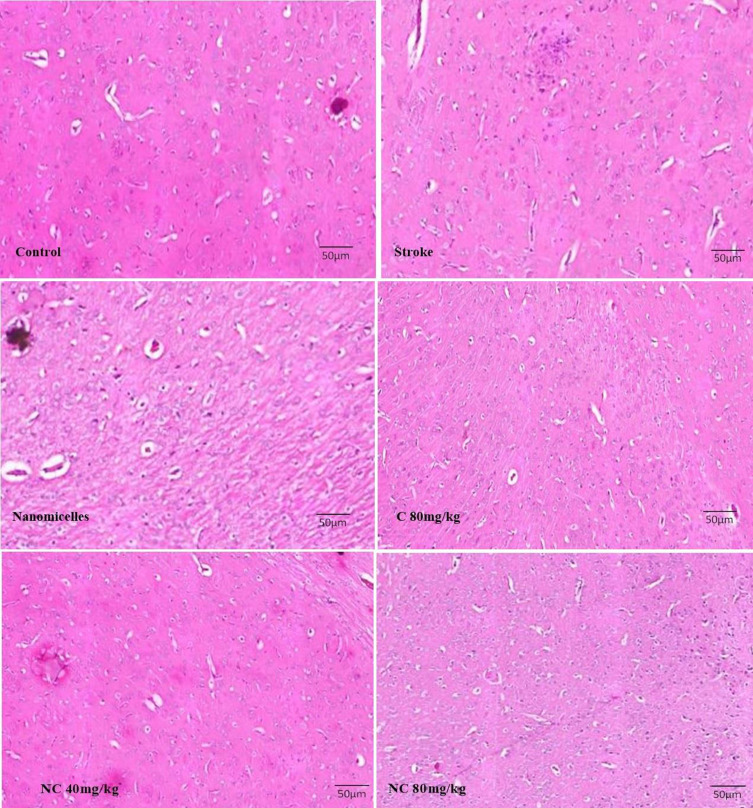

Histopathological Assay

After separation, rat hippocampus tissue was fixed in 10% formaldehyde solution for 24 h and then embedded in paraffin and cut into 5µ sections by a microtome. Sections from the CA1 and DG areas of the hippocampus were taken to examine for possible changes in brain tissue. Five tissue sections for each group were randomly examined. The sections were stained with H&E and then examined by a light microscope (Nikon, USA) with ×400 magnification.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was carried out using GraphPad Prism 7 software. The normal distribution of data was confirmed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Then, all data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Tukey post hoc test. Data were presented as Mean ± SEM. A probability level of p <0.05 was considered to be a significant difference.

Results

Characterization of Nanomicelles

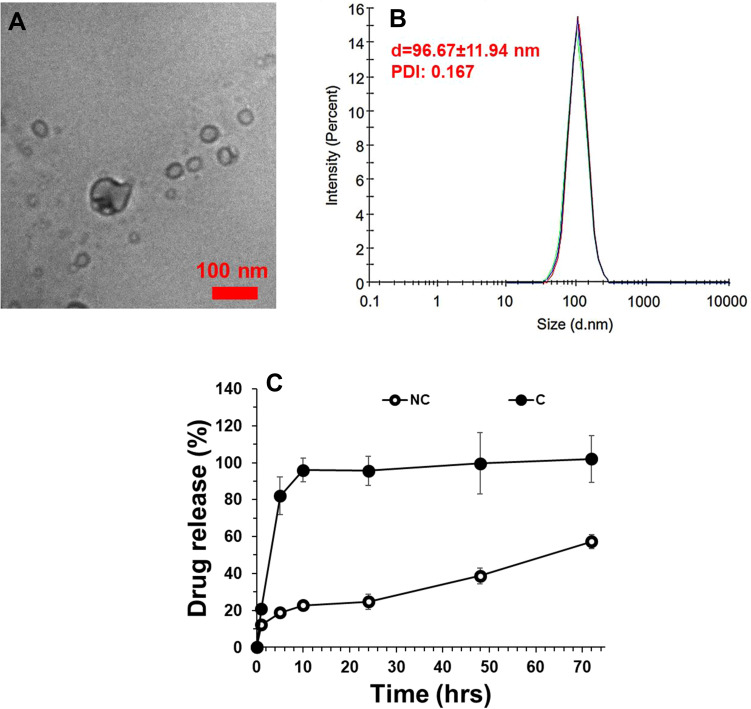

The calculated DL and EE were shown to be 41.2% and 91.5%, respectively. The final concentration of C loading in nanomicelles in the dried-powder was shown to be 2.09 µg/mg. The characterization of prepared NC was done by TEM and DLS techniques. As shown in Figure 1A, TEM analysis showed that prepared NC had a size of around 10nm. They were also well-dispersed and had a homogenous distribution in the sample (Figure 1A). DLS study was also done to determine the hydrodynamic radius and colloidal stability of prepared nanomicelles in the absence and presence of C. It was shown that the nanomicelles had a hydrodynamic radius of 96.67±11.94 nm (PDI: 0.167) with good colloidal solubility (Figure 1B). It was also observed that the loading of C into the nanomicelles and preparation of NC did not change its hydrodynamic radius (data not shown). The zeta potential of C, nanomicelles, and NC was evaluated to be around −13, 54 mV, −12.67 mV, and −23.52 mV, indicating also the potential colloidal stability of NC. A drug release assay was done to evaluate the amount of C released into the PBS medium over time (72 h). As shown in Figure 1C, it was indicated that C was gradually released from nanomicelles over 72 h at pH 7.4. Indeed, the release of C from nanomicelles showed slower release behavior than free C. Thus, the PLA-PEG-PLA triblock copolymer nanomicelles could improve the sustained release of C as a potential drug delivery system.

Figure 1.

Characterizations of prepared PLA-PEG-PLA triblock copolymer NC by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) at room temperature (A) and DLS at a constant angle of 90 degrees and temperature of 25°C (B). Drug release assay of C from NCs at pH 7.4 (C) (n=6).

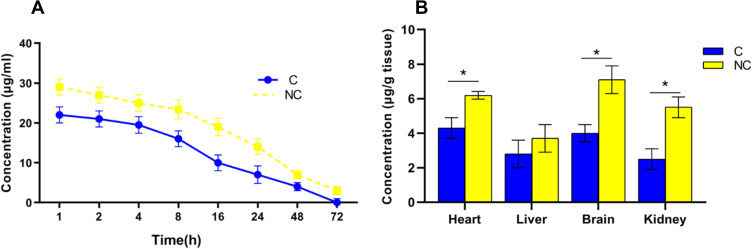

Plasma Concentration and Tissue Distribution of NC in vivo

In the rats that received NC and C orally for 14 days, the plasma concentration of NC was higher than free C and remained high for up to 24 h after the last administration. However, after 72 h, complete clearance of C from rat plasma was observed (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

(A)Plasma concentrations–time curve of C and NC; (B) Tissue distribution of C and NC (*p < 0.05) after 14 days' administration of C or NC by gavage (n=6). *Indicates significant differences at probability level of p <0.05.

In the rats that received NC and C orally for 14 days, differences in NC and C content were observed in different organs such as the heart, liver, brain, and kidneys. NC content in the brain was higher than C and NC uptake in organs such as the heart, brain, and kidneys was significantly different from C uptake (p <0.05). However, no difference in NC and C uptake was observed in the liver. It appears that the nanomicelle formulation of C leads to the high absorption of C in the organs of the brain, kidneys, and heart (Figure 2B).

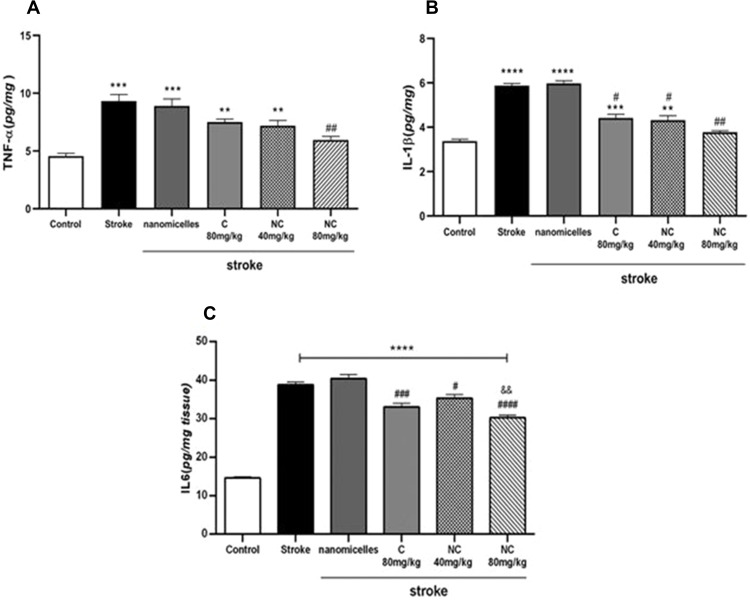

Effects of NC on Inflammatory Cytokines in Ischemic Brains

The results showed a nearly twofold upregulation of TNF-α protein level in I/R rats compared to controls, indicating an increase of inflammation in brain tissue of rats with cerebral I/R injury in stroke. However, NC in a dose-dependent manner was able to downregulate the TNF-α level, indicating the anti-inflammatory effects of NC in cerebral I/R conditions. In the present study, 80mg/kg NC had the highest effect on downregulation of TNF-α level and this effect was greater compared to 80mg/kg free C (Figure 3A). After induction of cerebral ischemia in rats, the IL-1β content increased in the stroke group compared to controls; however, as shown in Figure 3B, NC and C were able to reduce IL-1β levels. The IL-1β inhibitory effect of C and NC was compared and the results showed a concentration-dependent IL-1β inhibition effect by NC. It seems that NC at a dose of 80mg/kg was able to significantly reduce the level of IL-1β, which indicates the anti-inflammatory effects of 80mg/kg NC in conditions of cerebral I/R damage.

Figure 3.

Changes in TNF-α (A), IL-1β (B), and IL-6 (C) levels in cerebral ischemia rats administered with NC and C by gavage for 14 days before induction of BCCAO (n =6). ****p <0.0001, ***p <0.001, **p <0.01. $$P<0.01. # and ##showed significant differences at p< 0.05 and p <0.01 probability level, respectively between the pre-treated stroke rats group with 80 mg/kg nanomicelle curcumin compared with the stroke group.

A sharp increase in IL-6 level was observed in the ischemia brain tissue of rats, indicating a severe inflammatory response to cerebral I/R injury in stroke. Also, the IL-6 inhibitory effect of NC and C was compared and the results showed a dose-dependent inhibitory effect of NC on downregulation of IL-6 level so that the 80mg/kg resulted in the lowest IL-6 content in the brain of cerebral ischemic rats. Therefore, NC formulation plays an important role in downregulating IL-6 level and shows that this formulation can reduce inflammation caused by stroke (Figure 3C).

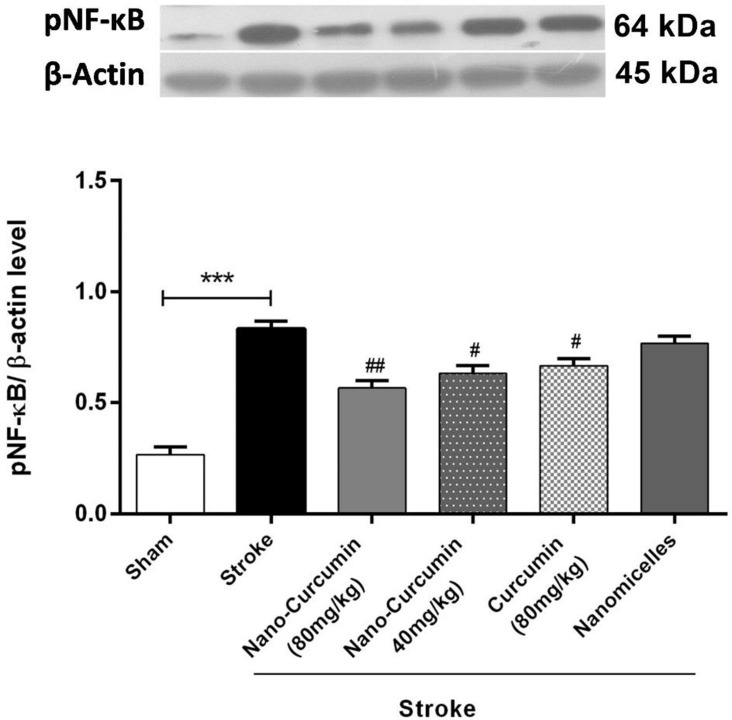

Anti-Inflammatory Effects of NC May Be Mediated Through pNF-ĸB Protein Downregulation

Western blotting was used to evaluate whether the anti-inflammatory effects of NC are related to NF-ĸB antagonizing. An upregulation in NF-ĸB protein expression was seen in rats with cerebral I/R injury in stroke. However, the inhibitory effect of NC on the expression of this protein was evident and downregulation in the expression of NF-ĸB protein was observed in pre-treated rats with NC at the dose of 80mg/kg, and this effect was more severe than in pre-treated rats with free C (Figure 4). Thus, the anti-inflammatory effects of the NC formulation may be due to the reduced expression of the NF-ĸB protein.

Figure 4.

Changes in NF-ĸB expression levels in rats treated with NC and C (n=6). ***p <0.001. ## and # showed significant differences at p <0.01 and p <0. 05 probability levels, respectively, between the pre-treated stroke rats’ group with NC and 80 mg/kg C compared with the stroke group (n=6).

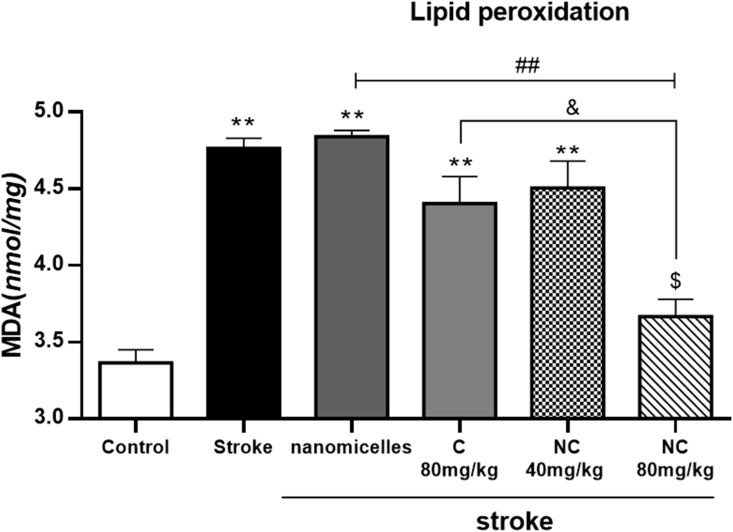

Effects of NC on Lipid Peroxidation in Ischemic Brains

Lipid peroxidation was significantly increased in rats with cerebral ischemia, indicating severe damage to brain cell membranes. However, NC 80mg/kg decreased MDA production significantly, indicating the inhibitory effects of NC on lipid peroxidation (Figure 5). It appears that the nanomicelle formulation of C has a strong lipid peroxidation inhibition effect compared to free ones.

Figure 5.

Malondialdehyde (MDA) production in cerebral ischemia rats treated with NC and C (n = 6). **p <0. 01 = significant difference compared with the control group; ##p <0. 01 = significant difference compared with stroke group; &p <0. 05 = significant difference between the pretreatment groups with 80mg/kg NC compared with 80 mg/kg C;. $p <0. 05 = significant differences between the pre-treatment groups with 80mg/kg NC compared to the group receiving 40mg/kg NC (n=6).

Results of Histopathological Study of the Brain

Pathological examination of the brain in rats with cerebral ischemia showed that neuronal damage and vasculature in the cerebral cortex tissue have occurred to a large extent and pyknotic and necrotic neurons were also seen. However, neuronal damage and degeneration occurred less frequently in the brains of rats pre-treated with NC as well as free C. Decreased neuronal degradation was more evident in rats pre-treated with 80mg/kg NC, indicating the protective effects of C in cerebral ischemia (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Light microscope images taken from the cross-sections of the hippocampal CA1 region (magnification 400x) (n=5).

Discussion

The present study showed a positive effect of triblock copolymer nanomicelles loaded with curcumin on reducing cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury due to anti-inflammatory effects, and these effects were due to the downregulation of cytokine levels involved in the inflammatory signal transduction pathway including Il-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and NF-ĸB. Reduction of lipid peroxidation was also observed with the administration of NC, which indicates a reduction in damage to neuronal cell membranes.

Curcumin is a compound with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties.28 However, its bioavailability and limited distribution in tissues29 have made its clinical application very limited.

The fine morphology of triblock copolymers can be exploited to provide the stimulated release of drugs/small molecules from polymer nanostructures (22). In the present study, well-defined amphiphilic triblock PLA-PEG-PLA copolymers were synthesized. It can be deduced that triblock PLA-PEG-PLA copolymers of polymers resulted in the synthesis of a nanomicelle with spherical-shaped morphology, high biocompatibility, and bioavailability, and sustained drug release. Indeed, the application of PEG and PLA-based copolymers results in unique drug release properties as well as controllable biodegradability, excellent biocompatibility. The presence of PEG on the surface of nanomicelles, in addition to facilitation of water adsorption into the inner part of the matrix and corresponding release of encapsulated drug, results in excellent biocompatibility and inhibits the immune system response and fast elimination of nanomicelles. Also, PLA, as the inner part of the micelle, prevents the permeation of destructive substances of the drug into the micelles.

In the present study, it was shown that the NC form increases C distribution in plasma and tissues including the brain, kidneys, and heart. It was also shown that NC improves C absorption. Studies have shown that solubility, permeability to plasma membranes and intestinal mucosa, and the efflux transporter are important factors that affect the absorption process. It seems that reducing the particle size to the nano scale can increase its adsorption and transfer.30,31 Therefore, the increase in plasma NC concentration compared to C can be attributed to the increased NC uptake in the intestine. Also, as NC plasma concentration decreased, the NC content in tissues increased and it was shown that the distribution of NC in tissues is higher than C. It has been shown that C can be metabolized in the kidney by the β-glucuronidase and sulfatase enzymes.32,33 Therefore, complete clearance from plasma 72 h after the last dose of NC and C in the present study indicates complete urinary C and NC excretion.

Other studies have reported that C inhibited lipid peroxidation,34 NF-ĸB expression,35 TNF-α production, and pro-inflammatory interleukins,36 which is in line with the current research findings. Cerebral ischemia through oxidative stress and inflammation leads to tissue damage,37 and due to the known antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of C, it may reduce the rate of tissue damage. Therefore, the reduction in tissue damage due to cerebral I/R in rats receiving NC may be due to the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of C. In the present study, downregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as Il-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α was observed in rats with cerebral I/R injury in stroke, which is consistent with the findings of other studies.38,39 However, the results showed that the nanomicelles' formulation of C in a dose-dependent manner has the ability to downregulate the expression of these pro-inflammatory cytokines. The inflammatory response after cerebral ischemia has been shown to have severe effects on neurons40 and oxidative stress in cerebral ischemia is associated with an inflammatory response.41 As noted, ischemic brain injury is associated with the accumulation of free radicals that cause severe expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and worsen oxidative conditions in the brain.42 Among these, one of the most important proteins involved in regulating the inflammatory response is NF-ĸB. The role of this protein in the inflammatory response to ischemic brain injury has been reported43 and it has also been noted that NF-ĸB regulates the expression of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6.44,45 In the present study, an upregulation in NF-ĸB protein expression and levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 were observed after cerebral I/R injury in stroke. However, the expression of all these factors involved in downregulation of inflammation in the brains of rats pre-treated with NC indicates a severe reduction in inflammation due to anti-inflammation effects of NC. TNF-α plays an important role in inflammatory diseases by stimulating the production of NF-ĸB and worsening cerebral I/R injury in stroke46 and can increase damage to the blood−brain barrier and cause cerebral edema through vascular permeability augmentation, and increase glutamic acid accumulation.47 In the present study, the results of the ELISA assay showed downregulation of TNF-α level pre-treated rats by NC. Therefore, it can be concluded that the neuroprotection of NC is regulated by altering the expression of the NF-ĸB/TNF-α signaling pathway and thus shows its anti-inflammatory effects.

Oxidative damage in cerebral ischemia has been reported by researchers48,49 and it has been stated that the accumulation of free radicals leads to lipid peroxidation.50 MDA is a toxic compound resulting from the peroxidation of plasma membrane lipids that have been used as a sensitive marker for cell damage.51 In the present study, levels of MDA were significantly elevated in rats with cerebral I/R injury in stroke, but NC in a dose-dependent manner was able to reduce MDA production and prevent its toxicity. Therefore, the reduction of oxidative stress may be part of the protective mechanism of NC in rats with cerebral I/R injury in stroke.

One of the strengths of the present study is the demonstration of the protective effects of NC on cerebral I/R injury. Also, the mechanism of protective effects of NC on cerebral I/R injury was studied. However, the current study had some limitations. The dose-dependent effects of NC on cerebral I/R injury require further studies. The present study was performed in vivo, therefore it seems that, in the future, it is necessary to evaluate the effect of NC on patients with stroke in clinical conditions. More research is needed in this area.

Conclusion

According to the results obtained in this study, it can be concluded that NC can play a neuroprotective role in rats with cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in stroke through its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. The molecular mechanism of these effects was attributed to the downregulation of expression of the NF-ĸB signaling pathway. Therefore, NC can be considered a promising and potential agent for the treatment of cerebral ischemia in the future.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by General Project of Health Commission of Hubei Province (NO.WJ2021M030), and Health Research Project of Metallurgical Safety and Health Branch of Chinese Society of Metals (NO. JKWS02013)

Ethical Approval

All the experiments were conducted following the guidelines of the Wuhan University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Katan M, Luft A. Global burden of stroke. Paper presented at: Seminars in neurology; 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poustchi F, Amani H, Ahmadian Z, et al. Combination therapy of killing diseases by injectable hydrogels: from concept to medical applications. Adv Healthcare Mater. 2021;10(3):2001571. doi: 10.1002/adhm.202001571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khoshnam SE, Winlow W, Farzaneh M, Farbood Y, Moghaddam HF. Pathogenic mechanisms following ischemic stroke. Neurol Sci. 2017;38(7):1167–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeynalov E, Jones SM, Elliott JP, Borlongan CV. Therapeutic time window for conivaptan treatment against stroke-evoked brain edema and blood-brain barrier disruption in mice. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0183985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toyoda K, Koga M, Naganuma M, et al. Routine use of intravenous low-dose recombinant tissue plasminogen activator in Japanese patients: general outcomes and prognostic factors from the SAMURAI register. Stroke. 2009;40(11):3591–3595. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.562991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lorenzano S, Vestri A, Bovi P, et al. Thrombolysis in elderly stroke patients in Italy (TESPI) trial and updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Stroke. 2019:1747493019884525. doi: 10.1177/1747493019884525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eltzschig HK, Collard CD. Vascular ischaemia and reperfusion injury. Br Med Bull. 2004;70(1):71–86. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldh025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amani H, Shahbazi M-A, D’Amico C, Fontana F, Abbaszadeh S, Santos HA. Microneedles for painless transdermal immunotherapeutic applications. J Control Release. 2021;330:185–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang C, Lu H-F, Chen Y-H, Chen J-C, Chou W-H, Huang H-C. Curcumin, demethoxycurcumin, and bisdemethoxycurcumin induced caspase-dependent and–independent apoptosis via Smad or Akt signaling pathways in HOS cells. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020;20(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12906-020-2857-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashraf K. A comprehensive review on curcuma longa linn.: phytochemical, pharmacological, and molecular study. Int J Green Pharm. 2018;11(4). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdollahi E, Momtazi AA, Johnston TP, Sahebkar A. Therapeutic effects of curcumin in inflammatory and immune‐mediated diseases: a nature‐made jack‐of‐all‐trades? J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(2):830–848. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang G, Yu R, Qiu H, et al. Beneficial effects of emodin and curcumin supplementation on antioxidant defence response, inflammatory response and intestinal barrier of Pengze crucian carp (Carassius auratus var. Pengze). Aquac Nutr. 2020;26(6):1958–1969. doi: 10.1111/anu.13137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abu-Baih RH, Bayoumi A, Ibrahim A, Ewees MG, Abdelraheim SR. Natural polyphenols target the TGF-β/caspase-3 signaling pathway in CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in rats. J Adv Biomed Pharm Sci. 2019;2(4):129–134. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu J, W-h X, Sun W, Sun Y, Guo Z-L, Yu X-L. Curcumin alleviates the functional gastrointestinal disorders of mice in vivo. J Med Food. 2017;20(12):1176–1183. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2017.3964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhat A, Mahalakshmi AM, Ray B, et al. Benefits of curcumin in brain disorders. BioFactors. 2019;45(5):666–689. doi: 10.1002/biof.1533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bavarsad K, Riahi MM, Saadat S, Barreto G, Atkin SL, Sahebkar A. Protective effects of curcumin against ischemia-reperfusion injury in the liver. Pharmacol Res. 2019;141:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang L, Chen C, Zhang X, et al. Neuroprotective effect of curcumin against cerebral ischemia-reperfusion via mediating autophagy and inflammation. J Mol Neurosci. 2018;64(1):129–139. doi: 10.1007/s12031-017-1006-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai Y-M, Chien C-F, Lin L-C, Tsai T-H. Curcumin and its nano-formulation: the kinetics of tissue distribution and blood–brain barrier penetration. Int J Pharm. 2011;416(1):331–338. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.06.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anand P, Kunnumakkara AB, Newman RA, Aggarwal BB. Bioavailability of curcumin: problems and promises. Mol Pharm. 2007;4(6):807–818. doi: 10.1021/mp700113r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shoba G, Joy D, Joseph T, Rajendran MMR, Srinivas P. Influence of piperine on the pharmacokinetics of curcumin in animals and human volunteers. Planta Med. 1998;64:353–356. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cen L, Hutzen B, Ball S, et al. New structural analogues of curcumin exhibit potent growth suppressive activity in human colorectal carcinoma cells. BMC Cancer. 2009;9(1):99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li L, Braiteh FS, Kurzrock R. Liposome‐encapsulated curcumin: in vitro and in vivo effects on proliferation, apoptosis, signaling, and angiogenesis. Cancer. 2005;104(6):1322–1331. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maiti K, Mukherjee K, Gantait A, Saha BP, Mukherjee PK. Curcumin–phospholipid complex: preparation, therapeutic evaluation and pharmacokinetic study in rats. Int J Pharm. 2007;330(1–2):155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rafiee Z, Nejatian M, Daeihamed M, Jafari SM. Application of different nanocarriers for encapsulation of curcumin. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2019;59(21):3468–3497. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2018.1495174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fan Z, Li J, Liu J, Jiao H, Liu B. Anti-inflammation and joint lubrication dual effects of a novel hyaluronic acid/curcumin nanomicelle improve the efficacy of rheumatoid arthritis therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10(28):23595–23604. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b06236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ashok B, Arleth L, Hjelm RP, Rubinstein I, Önyüksel H. In vitro characterization of PEGylated phospholipid micelles for improved drug solubilization: effects of PEG chain length and PC incorporation. J Pharm Sci. 2004;93(10):2476–2487. doi: 10.1002/jps.20150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rao B, Soufir J, Martin M, David G. Lipid peroxidation in human spermatozoa as relatd to midpiece abnormalities and motility. Gamete Res. 1989;24(2):127–134. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1120240202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hussain Z, Thu HE, Amjad MW, Hussain F, Ahmed TA, Khan S. Exploring recent developments to improve antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial efficacy of curcumin: a review of new trends and future perspectives. Mater Sci Eng C. 2017;77:1316–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.03.226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kunnumakkara AB, Harsha C, Banik K, et al. Is curcumin bioavailability a problem in humans: lessons from clinical trials. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2019;15(9):705–733. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2019.1650914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Z, Jiang H, Xu C, Gu L. A review: using nanoparticles to enhance absorption and bioavailability of phenolic phytochemicals. Food Hydrocoll. 2015;43:153–164. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2014.05.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Onoue S, Yamada S, Chan H-K. Nanodrugs: pharmacokinetics and safety. Int J Nanomedicine. 2014;9:1025. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S38378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luis PB, Kunihiro AG, Funk JL, Schneider C. Incomplete hydrolysis of curcumin conjugates by β‐glucuronidase: detection of complex conjugates in plasma. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2020;64(6):1901037. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201901037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vareed SK, Kakarala M, Ruffin MT, et al. Pharmacokinetics of curcumin conjugate metabolites in healthy human subjects. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomarkers. 2008;17(6):1411–1417. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim J-H, Jin S, Kwon HJ, Kim BW. Curcumin blocks naproxen-induced gastric antral ulcerations through inhibition of lipid peroxidation and activation of enzymatic scavengers in rats. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;26(8):1392–1397. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1602.02028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu Y, Liu L. Curcumin alleviates macrophage activation and lung inflammation induced by influenza virus infection through inhibiting the NF‐κB signaling pathway. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2017;11(5):457–463. doi: 10.1111/irv.12459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang L, Li N, Lin D, Zang Y. Curcumin protects against hepatic ischemia/reperfusion induced injury through inhibiting TLR4/NF-κB pathway. Oncotarget. 2017;8(39):65414. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo M, Lu H, Qin J, et al. Biochanin A provides neuroprotection against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by Nrf2-mediated inhibition of oxidative stress and inflammation signaling pathway in rats. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:8975. doi: 10.12659/MSM.918665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wytrykowska A, Prosba-Mackiewicz M, Nyka WM. IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 levels in gingival fluid and serum of patients with ischemic stroke. J Oral Sci. 2016;58(4):509–513. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.16-0278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Q, Liu Y, Chen L. Effects of PPARγ agonist decreasing the IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α content in rats on focal cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Biomed Res. 2017;28(21). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sieber MW, Jaenisch N, Brehm M, et al. Attenuated inflammatory response in triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) knock-out mice following stroke. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e52982. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bai S, Hu Z, Yang Y, et al. Anti‐inflammatory and neuroprotective effects of triptolide via the NF‐κ B signaling pathway in a rat MCAO model. Anat Rec. 2016;299(2):256–266. doi: 10.1002/ar.23293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu H, Wei X, Kong L, et al. NOD2 is involved in the inflammatory response after cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury and triggers NADPH oxidase 2-derived reactive oxygen species. Int J Biol Sci. 2015;11(5):525. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.10927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee DH, Lee CS. Flavonoid myricetin inhibits TNF-α-stimulated production of inflammatory mediators by suppressing the Akt, mTOR and NF-κB pathways in human keratinocytes. Eur J Pharmacol. 2016;784:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maddahi A, Edvinsson L. Cerebral ischemia induces microvascular pro-inflammatory cytokine expression via the MEK/ERK pathway. J Neuroinflammation. 2010;7(1):14. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yasuda Y, Shimoda T, Uno K, et al. Temporal and sequential changes of glial cells and cytokine expression during neuronal degeneration after transient global ischemia in rats. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shih R-H, Wang C-Y, Yang C-M. NF-kappaB signaling pathways in neurological inflammation: a mini review. Front Mol Neurosci. 2015;8:77. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2015.00077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maddahi A, Kruse LS, Chen Q-W, Edvinsson L. The role of tumor necrosis factor-α and TNF-α receptors in cerebral arteries following cerebral ischemia in rat. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8(1):107. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aşcı S, Demirci S, Aşcı H, Doğuç DK, Onaran İ. Neuroprotective effects of pregabalin on cerebral ischemia and reperfusion. Balkan Med J. 2016;33(2):221. doi: 10.5152/balkanmedj.2015.15742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahmed MA, El Morsy EM, Ahmed AA. Pomegranate extract protects against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury and preserves brain DNA integrity in rats. Life Sci. 2014;110(2):61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cai J-W, Wu H-X, Jin G-R, Xiang H-B, Lin L. Effect of shuanggenqinnao jianji on SOD MDA of Hippocampus and serum in vascular dementia rats. Chin Arch Tradit Chin Med. 2007;6. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Janero DR. Malondialdehyde and thiobarbituric acid-reactivity as diagnostic indices of lipid peroxidation and peroxidative tissue injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 1990;9(6):515–540. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90131-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]