Abstract

Tourette syndrome (TS) is a neurobehavioral disorder for which the neurological mechanism has not been elucidated. Voxel-based morphometry (VBM) studies have revealed abnormalities in gray matter volume (GMV) in patients with TS; however, consistent results have not been obtained. The current study attempted to provide a voxel wise meta-analysis of gray matter changes using seed-based d mapping (SDM). We identified ten relevant studies that investigated gray matter alterations in TS patients and performed a meta-analysis using the SDM method to quantitatively estimate regional gray matter abnormalities. Next, we examined the relationships between GMV abnormalities and demographic and clinical characteristics. Our results demonstrated that TS patients had smaller GMV in the bilateral inferior frontal gyri and greater GMV in the cerebellum, right striatum (putamen), and bilateral thalami (pulvinar nucleus) than healthy controls. A meta-regression analysis did not identify correlations between GMV changes and demographic or clinical variables. This meta-analysis confirmed significant and consistent GMV changes in several brain regions of TS patients, primarily in the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical network.

Subject terms: Neuroscience, Diseases

Introduction

Tourette syndrome (TS) is a neurological disorder characterized by primary motor and vocal tics, and it is frequently concomitant with obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), attention-deficit–hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), or other social and behavioral disturbances1–3. TS is classically identified in 5 individuals per 10004, tends to be inherited through families and often affects boys5 with a peak onset age of 3–8 years6. Previous studies have suggested that the severity of tics and comorbidities are age-related and may gradually achieve remission during adolescence7,8, and TS patients with comorbid disorders are at higher risk of suicide than pure TS patients9. The clinical symptoms of TS are complex and difficult to treat and thus pose major public health and economic burden. To date, the neurological basis of TS has not been determined.

In the past decade, neuroimaging technologies have been applied to studies of TS, among which voxel-based morphometry (VBM) is one of the most widely used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technologies. VBM is a comprehensive analysis technology for brain structure that can reflect the anatomical changes in the brain through quantitative calculation and analysis10,11. Although a previous VBM study12 did not find any brain morphological difference between treatment-naive boys with pure TS and healthy controls (HCs), other studies13–17 did find significant changes in TS patients. However, controversial changes have been reported by different studies. Reduced GMV was found in sensorimotor areas, the left superior temporal gyrus, left caudate nucleus, left postcentral gyrus, left hippocampal gyrus, bilateral anterior cingulate cortices and frontal areas (including the left frontal pole, bilateral inferior frontal gyri (IFG) and orbitofrontal, ventrolateral prefrontal cortices)15,17–21. Increased GMV has also been reported; for example, Garraux et al.14 found greater midbrain volumes in TS patients, and another study13 also found increased GMV in the posterior thalamus and hypothalamus. The inconsistency may be caused by differences in sample size and demographic and clinical characteristics or the effects of imaging techniques. These inconsistencies increase the difficulty of understanding the neurological mechanism of TS, and further exploration must be performed to reach a consensus. The meta-analysis method can provide a precise and robust summary after synthesizing the multitude of results from different studies in an unbiased way, and it may offer insights that are not immediately apparent from the individual studies22. Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis to integrate several previous studies with inconsistent results.

We hypothesized that some functional brain regions (such as the frontal cortex23,24, thalamus25,26, hippocampus27, basal ganglion, and midbrain28) of TS patients may be affected and thus show structural changes and that GMV abnormalities might be related to certain clinical factors. Therefore, we first performed a pooled meta-analysis of all the included VBM studies to determine the most prominent and consistent changes in gray matter in TS patients. Seed-based d mapping (SDM) software was used in this process because it can control the results of individual studies and all the information included in the study can be used in the same map29. We also analyzed the robustness and heterogeneity of the main findings. Next, a multivariate meta-regression analysis was performed to explore the potential relationship between the GMV changes and the clinical and demographic characteristics.

Methods

Selection of studies

A systematic search was performed for relevant studies published in the PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and Science Direct databases before July 31, 2020, according to the “Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses” (PRISMA) guidelines30. The key search words were ‘Tourette syndrome’ or ‘Gilles de la Tourette syndrome’ or ‘TS’ or ‘GTS’ plus ‘voxel-based morphometry’ or ‘VBM’ or ‘voxel-based’ or ‘voxel-wise’ plus ‘magnetic resonance imaging’ or ‘MRI’. Manual searches were also conducted in the reference lists of these studies.

The inclusion criteria of the studies were as follows: (i) original research published in peer-reviewed English journals; (ii) studies using VBM to analyze the changes in GMV of the whole brain; (iii) studies comparing the GMV between TS patients and HCs; and (iv) studies reporting whole-brain results in a stereotactic space (MNI or Talairach). Studies were excluded if they (i) were meta-analyses, case reports or reviews; (ii) failed to provide the three-dimensional coordinates in stereotactic space; or (iii) failed to include HC controls. If several publications were based on the same study, only the paper reporting the largest sample size was selected.

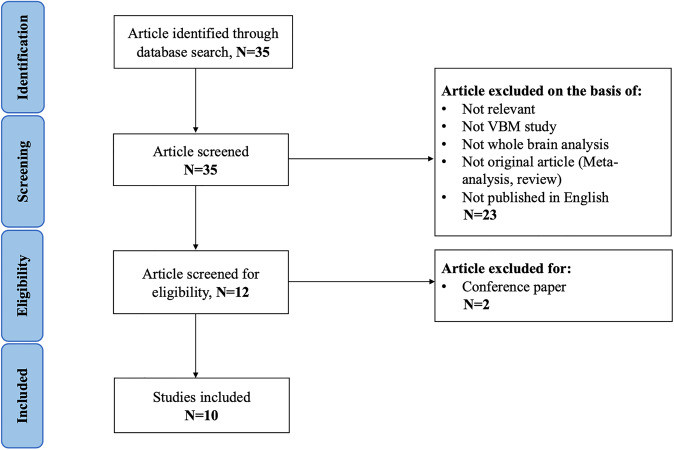

Two authors (X.Y.W. and S.M.Z.) searched the literature independently, checked all articles, and extracted and cross-checked the data. In case of a difference of opinion, they discussed the findings until a consensus was reached. The research screening process is shown in Fig. 1. According to the SDM method, we extracted the following data from the included studies: demographic and clinical characteristics (sample size, age, illness duration, onset age, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder self-assessment scale (ADHS-SR), Yale–Brown obsessive–compulsive scale (Y-BOCS)31, Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS)32, percentage of medicated patients and comorbidity), technical details (MRI scanner, software, smoothing, p value, and voxels) and three-dimensional coordinates.

Fig. 1. Search strategy used for the inclusion of the studies considered in the current meta-analysis.

Abbreviation: VBM voxel-based morphometry.

Voxel-wise meta-analysis: SDM

SDM is a statistical method for meta-analyses of brain activity or structural differences identified via neuroimaging techniques. SDM retains the useful features of original research and makes some improvements on the basis of some methods, such as activation likelihood estimation (ALE) and multi-level kernel density analysis (MKDA)33. We intended to conduct a pooled meta-analysis of all the included studies. Before we performed the meta-analysis, the peak coordinates and corresponding t-values were extracted from each study, and p values or z-values were converted to t-values online (http://www.sdmproject.com/utilities/?show=Statistics). Using SDM software (https://www.sdmproject.com/), we used the peak coordinates to recreate a map of the effect size. We performed all analyses based on the detailed analysis workflow described in the SDM tutorial (https://www.sdmproject.com/old/) as well as some publications34–36. First, positive and negative coordinates were reconstructed on the same map; thus, a signed differential map was obtained. Second, using effect sizes, reported peak coordinates were combined with statistical parametric maps for more accurate meta-analyses. Third, the heterogeneity, robustness and publication bias of the results were assessed (three analyses were used in our study). In SDM v4.31, a standard Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) map of the GMV differences was recreated for each included study using an anisotropic Gaussian kernel that assigns higher effect sizes to the voxels that are more closely correlated with peaks. These anisotropic kernels are introduced to optimize the recreation of effect size maps and provide greater robustness because they do not depend on a full width at half maximum37.

We assessed the robustness of the results using a jack-knife sensitivity analysis. It was performed to verify the reliability and stability of the findings through systematically repeated meta-analyses by excluding one study at a time. With the same threshold, inter-study heterogeneity analysis was conducted to find the heterogeneous brain regions with Q statistics using a random-effects model (Q maps can show the brain regions with significance inter-study heterogeneity). In addition, Egger’s test was used to assess publication bias by STATA software38. Meta-regression analyses were conducted using clinical variables including age, illness duration, ADHS-SR, Y-BOCS, YGTSS, and percentage of medicated patients, as regressors. In addition, we used MRIcron software (http://www.mricro.com/mricron/) to convert the final SDM results into images.

According to the recommendation of the developers of the SDM method, a threshold of p < 0.005 with a peak z > 1 and a cluster extent of more than 10 voxels were used for the meta-analyses (the default SDM thresholds)34. A conservative threshold of p < 0.0005 was adopted in the meta-regressions29,34.

Results

Included studies and sample characteristics

Based on the above strategy, a total of 35 studies were initially identified, and 10 of them met the inclusion criteria. These studies included 331 TS patients and 327 HCs. Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical data of all the included studies. Table 2 summarizes the technical details. Details of VBM preprocessing are summarized in Supplementary Table S1. None of the studies identified significant differences in age or sex between the TS group and the matched HC group. Supplementary Table S2 shows the results of GMV alterations from original studies while the original coordinates and respective effect sizes are reported in Supplementary Table S3.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects in the 10 voxel-based morphometry data sets included in the meta-analysis.

| Study | Number (male) | Age (years) | Duration | ADHS-SR* | Y-BOCS | YGTSS | Medication (%) | Comorbidity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TS | HC | TS | HC | (years) | ||||||

| Garraux et al.14 | 31 (25) | 31 (23) | 32.00 ± 10.50 | 32.00 ± 11.00 | NA | NA | NA | 31.60 | 29.00 | Yes |

| Ludolph et al.17 | 14 (14) | 15 (15) | 12.50 | 13.40 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 28.00 | Yes |

| Muller-Vahl et al.18 | 19 (19) | 20 (20) | 30.40 | 31.70 | NA | 26.88 | NA | 28.80 | Drug naive | No |

| Roessner et al.12 | 38 (38) | 38 (38) | 11.89 ± 1.33 | 12.19 ± 1.38 | 5.40 ± 2.00 | NA | NA | NA | Drug naive | No |

| Draganski et al.20 | 40 (30) | 40 (25) | 32.40 ± 11.00 | 34.40 ± 9.00 | 24.00 ± 11.60 | NA | NA | 28.70 ± 7.40 | 62.50 | Yes |

| Wittfoth et al.15 | 29 (29) | 24 (24) | 30.70 ± 9.00 | 30.60 ± 10.90 | NA | 7.20 | 10.50 | 35.70 ± 17.60 | Drug free | Yes |

| Liu et al.19 | 21 (20) | 20 (17) | 7.90 ± 1.95 | 8.05 ± 2.30 | 1.84 ± 0.56 | NA | NA | 41.71 ± 12.46 | Drug free | No |

| Ganos et al.21 | 14 (13) | 15 (13) | 30.60 ± 8.80 | 31.60 ± 8.90 | NA | 2.30 ± 2.40 | 0.90 ± 1.80 | 17.60 ± 6.60 | 21.40 | No |

| Debes et al.16 | 22 (20) | 21 (NA) | 14.20 ± 2.50 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Drug free | Yes |

| Greene et al.13 | 103 (81) | 103 (81) | 11.90 ± 2.10 | 11.90 ± 2.10 | NA | NA | 5.30 ± 6.80 | 18.10 ± 8.30 | 72.82 | Yes |

TS Tourette syndrome, HC health control, ADHS-SR attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder self-assessment scale, Y-BOCS Yale–Brown obsessive–compulsive scale, YGTSS Yale Global Tic Severity Scale, NA not available.

Table 2.

Technique details of the VBM studies on TS included in the meta-analysis.

| Study | MRI scanner | Head coil | T1 sequence | Software | Smoothing (FWHM) | p Value | Voxels | Coordinates | Template | Voxels size (image acquisition) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garraux et al.14 | 3.0 T (GE) | A standard GE head coil | FSPGR | SPM2 | 8 mm | p < 0.050 (FDR) | NA | 3 | MNI | 1.3 × 0.97 × 0.97 mm3 |

| Ludolph et al.17 | 1.5 T (Siemens) | NA | NA | SPM2 | 6 mm | p < 0.001 (corrected) | NA | 4 | MNI | NA |

| Muller-Vahl et al.18 | 1.5 T (GE) | NA | SPGR | SPM2 | 8 mm | p < 0.050 (FWE) | NA | 14 | MNI | 0.97 × 0.97 × 1.5 mm3 |

| Roessner et al.12 | 3.0 T (Siemens) | 8-channel | MPRAGE | SPM5 | 8 mm | p < 0.050 (FWE) | NA | 0 | MNI | 1 × 1 × 1 mm3 |

| Draganski et al.20 | 1.5 T (Siemens) | a phased-array coil | MDEFT | SPM8 | 6 mm | p < 0.050 (FWE) | NA | 8 | MNI | 1 × 1 × 1 mm3 |

| Wittfoth et al.15 | 1.5 T (GE) | NA | SPGR | SPM8 | 8 mm | p < 0.001 (uncorrected) | NA | 1 | MNI | 0.97 × 0.97 × 1.5 mm3 |

| Liu et al.19 | 1.5 T (Philips) | NA | 3D-FFE | SPM8 | 6 mm | p < 0.001 (uncorrected) | NA | 3 | MNI | 1 × 1 × 1 mm3 |

| Ganos et al.21 | 3.0 T (Siemens) | 12-channel | MPRAGE | SPM8 | 8 mm | p < 0.001 (corrected) | NA | 2 | NA | 1 × 1 × 1 mm3 |

| Debes et al.16 | 3.0 T (Philips) | 8-channel | Turbo-GRE | FSL | 3 mm | p < 0.050 (corrected) | NA | 1 | MNI | 1 × 1 × 1 mm3 |

| Greene et al.13 | 3.0 T*6/1.5 T*2 (several) | several | MPRAGE | SPM12 | 6 mm | p < 0.001 (FDR) | NA | 9 | MNI | Several (1.0–1.25 mm3) |

VBM voxel-based morphometry, TS Tourette syndrome, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, GE general electric, FSPGR fast spoiled gradient recalled sequence, SPGR spoiled gradient recalled echo sequence, MPRAGE magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition of gradient echoes sequence, MDEFT modified driven equilibrium Fourier transform protocol, 3D-FFE three-dimensional-Fast Field Echo sequence, Turbo-GRE turbo gradient echo sequence, FWHM full-width at half-maximum, SPM statistical parametric mapping, FDR false discovery rate, FWE family-wise error correction, NA not available, MNI Montreal Neurological Institute Space.

Pooled meta-analysis of all the included studies

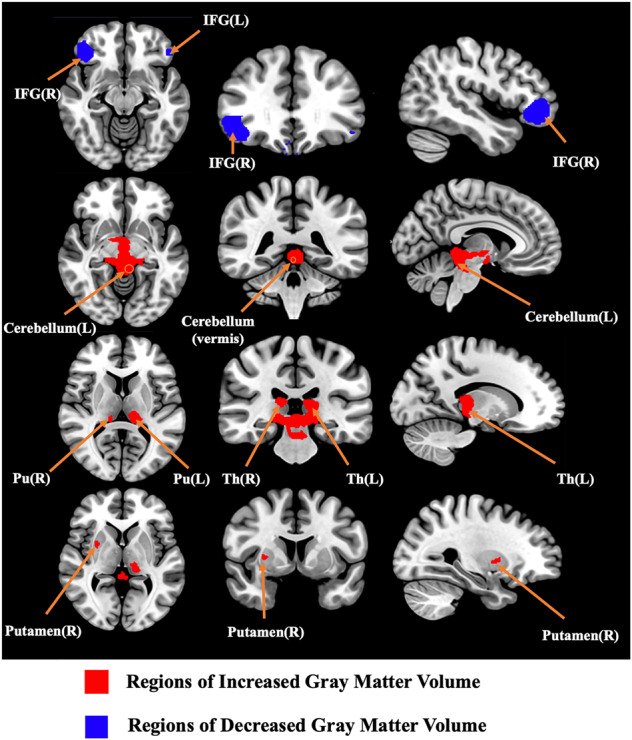

TS patients showed decreased GMV in the bilateral IFG. On the other hand, there were also some regions where GMV increased, i.e., the cerebellum, right striatum, and bilateral thalami (Table 3 and Fig. 2). Three-dimensional rendering images are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Table 3.

The brain regions with altered gray matter volume in TS patients identified by the main meta-analyses.

| Region | Maximum | Cluster | Jackknife sensitivity analysis | Egger’s tests (p) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNI coordinates x, y, z | SDM z-score | p Value uncorrected | Number of voxels | Breakdown (no. of voxels) | |||

| Increased regions | |||||||

| Cerebellum, vermic lobule III | 2, −36, −12 | 2.363 | <0.000000001 | 192 |

Left cerebellum, hemispheric lobule III/IV/V, BA27 30 (98) Cerebellum, vermic lobule I/II/III/IV/V, BA 27 30 (91) Right cerebellum, hemispheric lobule III (3) |

9 of 10 | 0.030 |

| Left thalamus | −10, −28, 10 | 2.113 | 0.000051618 | 112 |

Left thalamus (96) Left thalamus, BA 27 (16) |

9 of 10 | 0.002 |

| Right striatum | 8, −6, −12 | 2.192 | 0.000020623 | 72 |

Right striatum (52) Right lenticular nucleus, putamen (20) |

10 of 10 | 0.005 |

| Right thalamus | 12, −28, 14 | 1.992 | 0.000129044 | 54 |

Right thalamus (48) Right thalamus, BA 27 (6) |

9 of 10 | 0.002 |

| Decreased regions | |||||||

| Right inferior frontal gyrus | 42, 36, −4 | −1.507 | 0.000129044 | 635 |

Right inferior frontal gyrus, orbital part (468) Right inferior frontal gyrus, triangular part (107) Right middle frontal gyrus (60) |

9 of 10 | 0.457 |

| Right supramarginal gyrus | 60, −14,24 | −1.348 | 0.000696719 | 134 |

Right supramarginal gyrus, BA 42 43 48 (50) Right rolandic operculum, BA 22 42 48 (84) |

8 of 10 | 0.477 |

| Right postcentral gyrus | 52, 12, −12 | −1.192 | 0.000696719 | 129 |

Right postcentral gyrus, BA 3 43 48 (126) Right postcentral gyrus (3) |

8 of 10 | 0.279 |

| Left inferior frontal gyrus | −52, 28, −8 | −1.082 | 0.004154444 | 90 |

Left inferior frontal gyrus, orbital part (57) Left inferior frontal gyrus, triangular part (33) |

7 of 10 | 0.676 |

| Left rolandic operculum, BA 48 | −56, −6, 12 | −1.267 | 0.001491487 | 81 |

Left rolandic operculum, BA 48 (79) Left rolandic operculum (2) |

8 of 10 | 0.249 |

| Left superior temporal gyrus | −52, −14, 12 | −1.207 | 0.001852751 | 56 | Left superior temporal gyrus, BA22 42 48 (56) | 8 of 10 | 0.218 |

TS Tourette syndrome, BA Brodmann area, MNI Montreal Neurological Institute Space, SDM seed-based d mapping, BA Brodmann area.

Fig. 2. Regions showing gray matter volume alterations in TS patients compared with healthy controls.

Abbreviation: TS Tourette syndrome, L left, R right, IFG inferior frontal gyrus, Pu the pulvinar nucleus, Th thalamus.

Reliability analysis

When the whole-brain jackknife sensitivity analysis was performed, the main findings remained largely unchanged. The detailed data are shown in Table 3. We performed a visual inspection of the heterogeneity analysis according to the AES-SDM tutorial. It revealed that no significant inter-study heterogeneity occurred in the regions reported in the results (p > 0.005). The published bias results are summarized in Table 3.

Meta-regression analysis

We performed a simple linear regression analysis using SDM software to examine the potential impact of relevant clinical variables on GMV changes. Mean age, YGTSS, and percentage of medicated patients showed no relationship with the GMV changes. Due to the limited datasets included in this study, we failed to conduct the meta-regression analysis for illness duration, ADHS-SR, and Y-BOCS.

Discussion

Our study pooled 10 VBM studies with 331 TS patients and 327 controls to define GMV differences between TS patients and HCs. We observed the following gray matter alterations: (1) TS patients showed decreased GMV in the bilateral IFG; (2) TS patients showed increased GMV in the cerebellum, right striatum, and bilateral thalami; and (3) clinical or demographic characteristics were not correlated with GMV alterations based on the meta-regression analysis. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis performed to investigate whether consistent GMV alterations occur in TS patients using SDM.

Previous research methods, such as the region-of-interest approach, often focus on selected regions and exclude exploration of other brain regions that may be involved. Based on VBM, we can detect effects that do not fit traditional anatomic boundaries, such as a blob that is mostly located in the right IFG and partly in the right middle frontal cortex (Table 3). SDM is a widely applied method for neuropsychiatric studies39–42. Compared with ALE and MKDA, SDM is an optimal voxel-based meta-analytic method that adopts and combines the positive features of these two methods29,34. A novelty of this method is that both positive and negative coordinates are reconstructed in the same map to obtain a signed differential map, which represents an important feature to prevent the occurrence of both positive (increased volume or activation) and negative (decreased volume or activation) results of a particular voxel29. SDM can analyze the robustness of the results, which will ensure that the final results are the most replicable and robust. Furthermore, this method is capable of weighting and controlling results for multiple moderators including demographics, clinical information, and imaging factors. Another function of SDM is to conduct meta-analysis group comparisons to detect whether the computed effect sizes differ significantly between subgroups37. However, the number of included studies in our study was limited and could not meet the minimum requirement for subgroup analyses (ten studies)42. Some brain regions in the results may have potential publication bias and need verification in future studies. First, we performed a comprehensive literature search. Second, there is a tendency to publish studies with positive rather than negative results. In fact, when the number of studies is small (less than 20), the sensitivity of Egger’s tests for publication bias is generally low43.

We found that the GMV of TS patients decreased in bilateral IFG, which was thought to be responsible for the inability of TS patients to control their behavior15. The IFG has been suggested as the main brain region involved in response inhibition44–48, which occurs throughout its connection with the motor system46,49. Neuronal dysfunction of the IFG may lead to motor impulsivity, which is closely related to the core symptom of TS patients, i.e., involuntary tics12,50–54. In addition, OCD and ADHD patients often share tics and obsessive-like behaviors, which are characterized by repetitive, unconscious, involuntary and stereotyped movements55,56. Studies have reported decreased GMV in the left IFG of OCD patients57–59 and in the right IFG of ADHD patients60. Structural and functional MRI studies suggest that deficiency of the right inferior frontal lobe is the basis of impaired response inhibition61,62. Reduction of the GMV in the IFG in these comorbidities may also result in deficiency of response inhibition or failure to control behavior and may consequently lead to tics15,63. Moreover, the left IFG may constitute a common potential neurological correlation between TS and OCD/ADHD15.

This meta-analysis revealed increased GMV in the right striatum (including the putamen) of TS patients. The striatum is the primary input nucleus in the basal ganglia. Neural information from the sensory, motor, and marginal cortical inputs are selected by the striatum to perform neurological functions such as motor control, habit formation, and some social behaviors64–67. Much attention has been given to the dopaminergic system and the γ-amino butyric acid (GABA)-ergic system of the striatum in TS patients68. The dopaminergic system is dysfunctional in TS patients27,69–71, which has been attributed to the impaired putamen in Lerner’s study72. An early study has shown that TS is associated with increased striatal dopaminergic innervation73. Hyperactivity of the dopamine system enhances striatal activity such as habit formation, initiation, and execution18,65, and thus promotes the formation of tics habits through the reinforcement of the learning process74. It has also been suggested that changes in GMV in the striatum are the morphological evidence of dopaminergic hyperfunction17. The striatum is also a part of the neural circuit that produces and controls movements through GABA54,71,75–77, an important inhibitory neurotransmitter. Tics are often considered an involuntary movement that can be suppressed. In the striatum, a decrease in GABAA receptor binding and a decrease in GABAergic inhibitory neurons78 result in dysfunction of the GABAergic system75,79,80 and may lead to tics and obsessive-like behaviors in TS patients67,81. Future studies with different methodologies are expected to clarify how neurotransmitter changes may lead to volumetric abnormalities. Furthermore, the putamen, which is thought to be involved in habit learning and motor control82, showed increased GMV. Several functional studies have demonstrated increased activity of the putamen72,83 and a positive correlation with the severity of tics83. The increased activity of the putamen is a reflection of the increased signal properties caused by the change in neuronal volume17.

The thalamus is involved in cognitive and motor motivational pathways19,84 and multisensory integration13. We found that the GMV increased in the thalamus, and the blob for the effect reported in the thalamus appeared to lie mainly in the pulvinar nucleus (Fig. 2), which was consistent with a previous study85. One hypothesis to explain this phenomenon is based on the theory of compensatory mechanisms16,85,86, which suggested that thalamic GMV increases as an adaptive change to attenuate and control tics because the extended network formed by the expanded thalamus can increase the executive control of motor circuits in TS patients85. Another possible explanation is the dysfunction of motor circuity in TS patients. Overactivity of the output pathway of the basal ganglia may remove the inhibition of thalamocortical projections and result in overactivity of the motor nuclei of the thalamus85. Overactivity over an extended period of time may eventually result in activity-dependent hypertrophy in the thalamus85.

We found increased GMV in the anterior cerebellum, including the vermis and the left hemispheric lobule, which may suggest that the cerebellum is involved in the pathogenesis of TS. The cerebellum plays a role in motor control and some cognitive functions87. Activation of the cerebellar hemispheres and vermis during tic release has been observed in a functional study72, suggesting that the cerebellum may play an important role in tics of TS. The relationship between structural and functional changes needs to be validated by more studies with larger sample size and a longitudinal design.

As mentioned above, GM volumetric abnormalities in the IFG, putamen, thalamus, and other parts were found, most of which belonged to the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical (CSTC) network53 and they interacted with one another. Dysfunction of the CSTC network has been widely recognized by neuropathological studies as well as structural and functional neuroimaging research68,88–90. It is generally believed that the striatum (especially the putamen and caudate nuclei) can inhibit the basal ganglia output nucleus through increased striatal activity when receiving the excitatory input from the cerebral cortex. Next, the inhibition of the thalamus is released, and the cortex is stimulated to generate tics89. The cerebellum, as a node outside of the classical CSTC network, is involved in the so-called “basal ganglia-cerebellar-thalamo-cortical system”88. Previous studies have suggested that the cerebellum, similar to the basal ganglia, integrates inputs from the cerebral cortex such as the prefrontal cortex, which then generates output to the anterior motor cortex, the primary motor cortex, and even the same areas of the input cortex, through the thalamus91. It was further found that the subthalamic nucleus in the basal ganglia had projections to the cerebellar cortex and integrated functions of the basal ganglia and the cerebellum91. Basal ganglia-cerebellar-cortical interactions play an important role in the generation of tics88. These brain regions may serve as new targets for further study to develop effective treatments. Some studies have shown that the application of deep brain stimulation to the CSTC nodes or the connections between the nodes may help to alleviate tics92–94. The cerebellum outside the classical network can also be a target for intractable TS95.

In the meta-regression analysis, we did not find significant associations between clinical variables and GMV changes. The negative results may be due to differences in age, disease duration, medication status and comorbidities among the TS patients included in the study. For example, tics in adults do not fluctuate as much as in children and adolescents, and such differences may also influence the scoring of disease severity. However, the mean age and YGTSS were still of particular interest to us, and the prospective assessment of these variables will still be useful for future research.

Limitations

Our research has several limitations. First, compared with other meta-analyses, our study is based on the published coordinates of the original study instead of the raw data, which may lead to a bias in the results. Differences in the original studies may have had some effects, such as the use of MNI templates in children, incomplete clinical information, and different scanner parameters for data acquisition and postprocessing. Collecting original data and making efforts to minimize the differences of data from different sources of examining facilities may help to control the bias. Second, since the number of included studies in our study did not meet the minimum requirement of subgroup analyses42, we were unable to test the effects of age (pediatric vs. adult) or sex. Finally, only ten original studies were included; therefore, the results of the meta-regression would be affected. We expect that studies in the future will better verify our conclusions.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis confirmed GMV changes in the IFG, striatum, thalamus, and cerebellum in TS patients, most of which are key nodes of the CSTC network. These findings provide new insights into the possible treatment targets of TS patients. However, they need to be confirmed by more studies, and the mechanism of GMV changes as well as the relationship between GMV changes and clinical symptoms need to be further clarified.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant nos. 81621003 and 82027808), the Sichuan Provincial Foundation of Science and Technology (Grant nos. 2019YFS0428 and 2018SZ0175), and the Foundation of the National Research Center of Geriatrics (Grant no. Z2018A07).

Author contributions

Q. Y. conceived the project, X. W., S. Z., W. W., X. S., X. Y., and Q. T. obtained the data. X. W. and S. Z. wrote the main paper. All authors critically reviewed the paper. Q. Y. and Q. G. revised the paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Xinyue Wan, Simin Zhang

Contributor Information

Qiang Yue, Email: scu_yq@163.com.

Qiyong Gong, Email: qiyonggong@hmrrc.org.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41398-021-01394-8.

References

- 1.Robertson MM. A personal 35 year perspective on Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: prevalence, phenomenology, comorbidities, and coexistent psychopathologies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:68–87. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muth CC. Tics and Tourette syndrome. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2017;317:1592. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keri S, Szlobodnyik C, Benedek G, Janka Z, Gadoros J. Probabilistic classification learning in Tourette syndrome. Neuropsychologia. 2002;40:1356–1362. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3932(01)00210-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greydanus DE, Tullio J. Tourette’s disorder in children and adolescents. Transl. Pediatr. 2020;9:S94–S103. doi: 10.21037/tp.2019.09.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serajee FJ, Mahbubul Huq AH. Advances in Tourette syndrome: diagnoses and treatment. Pediatr. Clin. North. Am. 2015;62:687–701. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roth J. The colorful spectrum of Tourette syndrome and its medical, surgical and behavioral therapies. Parkinsonism. Relat. Disord. 2018;46(Suppl 1):S75–S79. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groth C, Mol Debes N, Rask CU, Lange T, Skov L. Course of Tourette syndrome and comorbidities in a large prospective clinical study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2017;56:304–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hallett M. Tourette Syndrome: update. Brain Dev. 2015;37:651–655. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartmann A, Worbe Y, Black KJ. Tourette syndrome research highlights from 2017. F1000Research. 2018;7:1122. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.15558.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.May A, Gaser C. Magnetic resonance-based morphometry: a window into structural plasticity of the brain. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2006;19:407–411. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000236622.91495.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitwell JL. Voxel-based morphometry: an automated technique for assessing structural changes in the brain. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:9661–9664. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2160-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roessner V, et al. No brain structure abnormalities in boys with Tourette’s syndrome: a voxel-based morphometry study. Mov. Disord. 2009;24:2398–2403. doi: 10.1002/mds.22847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greene DJ, Williams Iii AC, Koller JM, Schlaggar BL, Black KJ. Brain structure in pediatric Tourette syndrome. Mol. Psychiatry. 2017;22:972–980. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garraux G, et al. Increased midbrain gray matter in Tourette’s syndrome. Ann. Neurol. 2006;59:381–385. doi: 10.1002/ana.20765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wittfoth M, et al. Lateral frontal cortex volume reduction in Tourette syndrome revealed by VBM. BMC Neurosci. 2012;13:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-13-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Debes N, et al. Longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) analysis of the developmental changes of tourette syndrome reveal reduced diffusion in the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical pathways. J. Child Neurol. 2015;30:1315–1326. doi: 10.1177/0883073814560629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ludolph AG, et al. Grey-matter abnormalities in boys with Tourette syndrome: magnetic resonance imaging study using optimised voxel-based morphometry. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2006;188:484–485. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.008813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muller-Vahl KR, et al. Prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortex abnormalities in Tourette Syndrome: evidence from voxel-based morphometry and magnetization transfer imaging. BMC Neurosci. 2009;10:47. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-10-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, et al. Structural abnormalities in early Tourette syndrome children: a combined voxel-based morphometry and tract-based spatial statistics study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e76105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Draganski B, et al. Multispectral brain morphometry in Tourette syndrome persisting into adulthood. Brain. 2010;133:3661–3675. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ganos C, et al. Prefrontal cortex volume reductions and tic inhibition are unrelated in uncomplicated GTS adults. J. Psychosom. Res. 2014;76:84–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quah, S. R. & Cockerham, W. C. International Encyclopedia of Public Health (Academic Press, Elsevier, 2017).

- 23.Jackson SR, et al. Compensatory neural reorganization in Tourette syndrome. Curr. Biol. 2011;21:580–585. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoon DY, Gause CD, Leckman JF, Singer HS. Frontal dopaminergic abnormality in Tourette syndrome: a postmortem analysis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2007;255:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.01.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neuner I, et al. Imaging the where and when of tic generation and resting state networks in adult Tourette patients. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014;8:362. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossi PJ, et al. Scheduled, intermittent stimulation of the thalamus reduces tics in Tourette syndrome. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2016;29:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singer HS. Motor control, habits, complex motor stereotypies, and Tourette syndrome. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2013;1304:22–31. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yin HH. Action, time and the basal ganglia. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2014;369:20120473. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radua J, Mataix-Cols D. Voxel-wise meta-analysis of grey matter changes in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2009;195:393–402. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.055046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open Med. 2009;3:e123–e130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goodman WK, et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1989;46:1006–1011. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leckman JF, et al. The Yale Global Tic Severity Scale: initial testing of a clinician-rated scale of tic severity. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 1989;28:566–573. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198907000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu X, et al. Meta-analytic investigations of common and distinct grey matter alterations in youths and adults with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017;78:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Radua J, et al. A new meta-analytic method for neuroimaging studies that combines reported peak coordinates and statistical parametric maps. Eur. Psychiatry. 2012;27:605–611. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muller VI, et al. Ten simple rules for neuroimaging meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018;84:151–161. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Radua J, Mataix-Cols D. Meta-analytic methods for neuroimaging data explained. Biol. Mood Anxiety Disord. 2012;2:6. doi: 10.1186/2045-5380-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Radua J, et al. Anisotropic kernels for coordinate-based meta-analyses of neuroimaging studies. Front. Psychiatry. 2014;5:13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br. Med. J. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Via E, Radua J, Cardoner N, Happé F, Mataix-Cols D. Meta-analysis of gray matter abnormalities in autism spectrum disorder: should Asperger disorder be subsumed under a broader umbrella of autistic spectrum disorder? Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2011;68:409–418. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wise T, et al. Common and distinct patterns of grey-matter volume alteration in major depression and bipolar disorder: evidence from voxel-based meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry. 2017;22:1455–1463. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lim L, Radua J, Rubia K. Gray matter abnormalities in childhood maltreatment: a voxel-wise meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2014;171:854–863. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carlisi CO, et al. Comparative multimodal meta-analysis of structural and functional brain abnormalities in autism spectrum disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2017;82:83–102. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sterne JA, Egger M, Smith GD. Systematic reviews in health care: investigating and dealing with publication and other biases in meta-analysis. BMJ. 2001;323:101–105. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7304.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chambers CD, et al. Dissociable mechanisms of cognitive control in prefrontal and premotor cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 2007;98:3638–3647. doi: 10.1152/jn.00685.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chikazoe J, et al. Functional dissociation in right inferior frontal cortex during performance of go/no-go task. Cereb. Cortex. 2009;19:146–152. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aron AR, Fletcher PC, Bullmore ET, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW. Stop-signal inhibition disrupted by damage to right inferior frontal gyrus in humans. Nat. Neurosci. 2003;6:115–116. doi: 10.1038/nn1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aron AR, Robbins TW, Poldrack RA. Inhibition and the right inferior frontal cortex: one decade on. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2014;18:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swick D, Ashley V, Turken AU. Left inferior frontal gyrus is critical for response inhibition. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9:102. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liakakis G, Nickel J, Seitz RJ. Diversity of the inferior frontal gyrus-a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Behav. Brain Res. 2011;225:341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garavan H, Ross TJ, Stein EA. Right hemispheric dominance of inhibitory control: an event-related functional MRI study. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:8301–8306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peterson BS, et al. A functional magnetic resonance imaging study of tic suppression in Tourette syndrome. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1998;55:326–333. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.4.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Orth M. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. J. Psychosom. Res. 2009;67:591–598. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Worbe Y, Lehericy S, Hartmann A. Neuroimaging of tic genesis: present status and future perspectives. Mov. Disord. 2015;30:1179–1183. doi: 10.1002/mds.26333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ganos C. Tics and Tourette’s: update on pathophysiology and tic control. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2016;29:513–518. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roth RM, Baribeau J, Milovan DL, O’Connor K. Speed and accuracy on tests of executive function in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Brain Cogn. 2004;54:263–265. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2004.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Delalande L, et al. Complex and subtle structural changes in prefrontal cortex induced by inhibitory control training from childhood to adolescence. Dev. Sci. 2020;23:e12898. doi: 10.1111/desc.12898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Wit SJ, et al. Multicenter voxel-based morphometry mega-analysis of structural brain scans in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2014;171:340–349. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13040574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hou J, et al. Morphologic and functional connectivity alterations of corticostriatal and default mode network in treatment-naive patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e83931. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoo SY, et al. Voxel-based morphometry study of gray matter abnormalities in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2008;23:24–30. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2008.23.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pironti VA, et al. Neuroanatomical abnormalities and cognitive impairments are shared by adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and their unaffected first-degree relatives. Biol. Psychiatry. 2014;76:639–647. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sowell ER, et al. Cortical abnormalities in children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 2003;362:1699–1707. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14842-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Casey BJ, et al. Implication of right frontostriatal circuitry in response inhibition and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 1997;36:374–383. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Johannes S, et al. Altered inhibition of motor responses in Tourette Syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2001;104:36–43. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2001.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pappas SS, Leventhal DK, Albin RL, Dauer WT. Mouse models of neurodevelopmental disease of the basal ganglia and associated circuits. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2014;109:97–169. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-397920-9.00001-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kuo HY, Liu FC. Synaptic wiring of corticostriatal circuits in basal ganglia: insights into the pathogenesis of neuropsychiatric disorders. eNeuro. 2019;6:0076–19. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0076-19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rapanelli M, Frick LR, Pittenger C. The role of interneurons in autism and Tourette syndrome. Trends Neurosci. 2017;40:397–407. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Israelashvili M, Bar-Gad I. Corticostriatal divergent function in determining the temporal and spatial properties of motor tics. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:16340–16351. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2770-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Albin RL, Mink JW. Recent advances in Tourette syndrome research. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Robertson MM, et al. Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2017;3:16097. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Singer HS, Butler IJ, Tune LE, Seifert WE, Jr., Coyle JT. Dopaminergic dsyfunction in Tourette syndrome. Ann. Neurol. 1982;12:361–366. doi: 10.1002/ana.410120408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bronfeld M, Yael D, Belelovsky K, Bar-Gad I. Motor tics evoked by striatal disinhibition in the rat. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2013;7:50. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2013.00050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lerner A, et al. Neuroimaging of neuronal circuits involved in tic generation in patients with Tourette syndrome. Neurology. 2007;68:1979–1987. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000264417.18604.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Albin RL, et al. Increased ventral striatal monoaminergic innervation in Tourette syndrome. Neurology. 2003;61:310–315. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000076181.39162.FC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Maia TV, Conceicao VA. Dopaminergic disturbances in Tourette syndrome: An Integrative Account. Biol. Psychiatry. 2018;84:332–344. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.02.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lerner A, et al. Widespread abnormality of the gamma-aminobutyric acid-ergic system in Tourette syndrome. Brain. 2012;135:1926–1936. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bronfeld M, Bar-Gad I. Tic disorders: what happens in the basal ganglia? Neuroscientist. 2013;19:101–108. doi: 10.1177/1073858412444466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jackson GM, Draper A, Dyke K, Pepes SE, Jackson SR. Inhibition, disinhibition, and the control of action in Tourette Syndrome. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2015;19:655–665. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rae CL, Critchley HD, Seth AK. A Bayesian account of the sensory-motor interactions underlying symptoms of Tourette syndrome. Front. Psychiatry. 2019;10:29. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vinner E, Israelashvili M, Bar-Gad I. Prolonged striatal disinhibition as a chronic animal model of tic disorders. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2017;292:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Worbe Y, et al. Towards a primate model of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: anatomo-behavioural correlation of disorders induced by striatal dysfunction. Cortex. 2013;49:1126–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xu M, et al. Targeted ablation of cholinergic interneurons in the dorsolateral striatum produces behavioral manifestations of Tourette syndrome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:893–898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419533112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tricomi E, Balleine BW, O’Doherty JP. A specific role for posterior dorsolateral striatum in human habit learning. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:2225–2232. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06796.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang Z, et al. The neural circuits that generate tics in Tourette’s syndrome. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2011;168:1326–1337. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.09111692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gilbert DL, et al. Altered mesolimbocortical and thalamic dopamine in Tourette syndrome. Neurology. 2006;67:1695–1697. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000242733.18534.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Miller AM, et al. Enlargement of thalamic nuclei in Tourette syndrome. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2010;67:955–964. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Baym CL, Corbett BA, Wright SB, Bunge SA. Neural correlates of tic severity and cognitive control in children with Tourette syndrome. Brain. 2008;131:165–179. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wolf U, Rapoport MJ, Schweizer TA. Evaluating the affective component of the cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2009;21:245–253. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2009.21.3.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Caligiore D, Mannella F, Arbib MA, Baldassarre G. Dysfunctions of the basal ganglia-cerebellar-thalamo-cortical system produce motor tics in Tourette syndrome. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017;13:e1005395. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mink JW. Basal ganglia dysfunction in Tourette’s syndrome: a new hypothesis. Pediatr. Neurol. 2001;25:190–198. doi: 10.1016/S0887-8994(01)00262-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ganos C, Rothwell J, Haggard P. Voluntary inhibitory motor control over involuntary tic movements. Mov. Disord. 2018;33:937–946. doi: 10.1002/mds.27346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bostan AC, Strick PL. The cerebellum and basal ganglia are interconnected. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2010;20:261–270. doi: 10.1007/s11065-010-9143-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schleyken S, et al. Deep brain stimulation and sensorimotor gating in tourette syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020;129:272–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Andrade P, et al. Modulation of fibers to motor cortex during thalamic DBS in Tourette patients correlates with Tic reduction. Brain Sci. 2020;10:302. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10050302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Neudorfer C, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the H fields of forel alleviates tics in Tourette syndrome. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017;11:308. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.McCairn KW, Iriki A, Isoda M. Global dysrhythmia of cerebro-basal ganglia-cerebellar networks underlies motor tics following striatal disinhibition. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:697–708. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4018-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.