Abstract

Background

Depression has been implicated as a poor predictor of outcomes after total joint arthroplasty (TJA) of the lower extremity in some studies. We aimed to determine whether depression as a comorbidity affects the TJA outcomes and whether pain reduction associated with successful TJA alters depressive symptoms.

Methods

A search of PUBMED was performed using keywords “depression”, “arthroplasty”, “depressive disorder”, and “outcomes.” All English studies published over the last ten years were considered for inclusion. Quantitative and qualitative analysis was then performed on the data.

Results

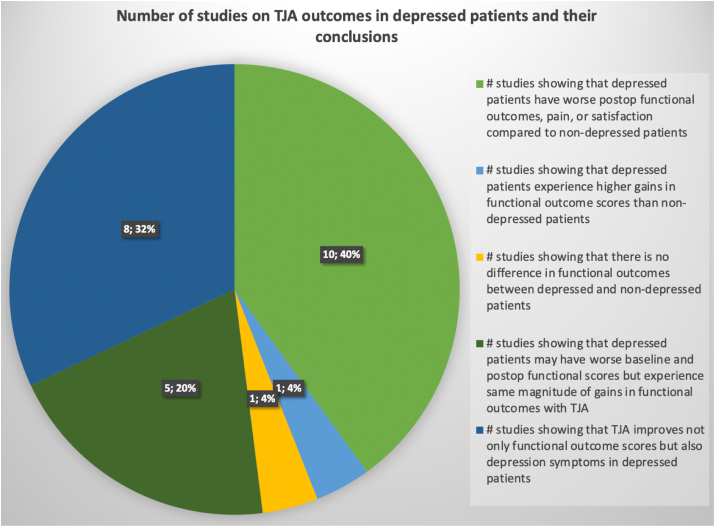

Thirty articles met inclusion criteria (16 retrospective, 14 prospective). Three showed that depressed patients were at higher risk for readmission. Two reported that depressed patients had higher likelihood of non-home discharge after TJA compared to non-depressed patients. Four noted that depressed patients incur higher hospitalization costs than non-depressed patients. Ten suggest depression is a predictor of poor patient-reported outcome measures, pain, and satisfaction after TJA. Five suggested the gains depressed patients experience in functional outcome scores after TJA are similar to gains experienced by patients without depression. Another eight suggested that TJA improves not only function and pain but also depressive symptoms in patients with depression.

Conclusion

The results of this review show that depression increases the risk of persistent pain, dissatisfaction, and complications after TJA. Additionally, depressed patients may incur higher costs than non-depressed patients undergoing TJA and may have worse preoperative and postoperative patient reported outcome measures (PROMs). However, the gains in function that depressed patients experience after TJA are equivalent to gains experienced by non-depressed patients and depressed patients may experience improvement in their depressive symptoms after TJA. Patient selection for TJA is critical and counseling regarding increased risk for complications is crucial in depressed patients undergoing TJA.

Keywords: Knee arthroplasty, Knee replacement, Depression, Anxiety, Mood disorder, Outcomes, Hip arthroplasty, Hip replacement, Depressive symptoms, PROMs, Satisfaction, Psychosocial factors

1. Introduction

Total joint arthroplasty (TJA) effectively alleviates hip and knee pain while improving physical function and is one of the most reliable surgeries in orthopaedics.1,2 While outcomes are largely good and patients are consistently satisfied with their decision to undergo joint replacement surgery, there is still a minority of patients who remain dissatisfied with their outcomes, especially after a total knee arthroplasty (TKA).3,4 There are several factors that have been investigated in relation to poor patient-reported outcomes after total hip arthroplasty (THA) or TKA and these include patient-centric, technical, and implant-specific factors.4, 5, 6

One of the patient-specific factors that has recently been associated with poorer outcomes after TJA is depression7. Brander et al. in their prospective study, found that preoperative depression was associated with poor functional outcome scores following TKA at 5-year follow-up.7 Similarly, Singh et al. found that depression was associated with pain, functional limitation, and persistent use of pain medications after revision THA at 5-year follow-up.8 These initial studies prompted further investigation of the relationship between depression and TJA outcomes.

More recent literature suggests that depressed patients may also be at higher risk for complications after TJA and incur greater costs for surgery.9,10 These results may make the orthopaedic surgeon more hesitant to offer TJA to patients with mental health disorders. There has not been a systematic analysis performed so far that summarizes the current evidence to answer the following questions: 1) Do patients with depression have increased risks compared to non-depressed TJA patients? 2) Do depressed patients benefit from TJAs in a manner similar to non-depressed patients? The purpose of this systematic review is to answer the above questions by analyzing the published evidence to date.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy

A complete search of the literature was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.11 The electronic PUBMED database was searched using varying combinations of the following keywords: “depression”, “depressive”, “arthroplasty”, “outcomes”, and “joint replacement”. The literature search was restricted to studies published between January 1, 2010 and October 8, 2020.

2.2. Study selection

The following inclusion criteria were used for study selection: (a) The study design had to be Level of Evidence I, II, or III as defined by Centre for Evidence Based Medicine12; (b) the study looks at outcomes following intervention of interest—total hip or total knee arthroplasty; (c) the study assesses the relationship between depression and arthroplasty outcomes; and (d) study participants were 18 years or older.

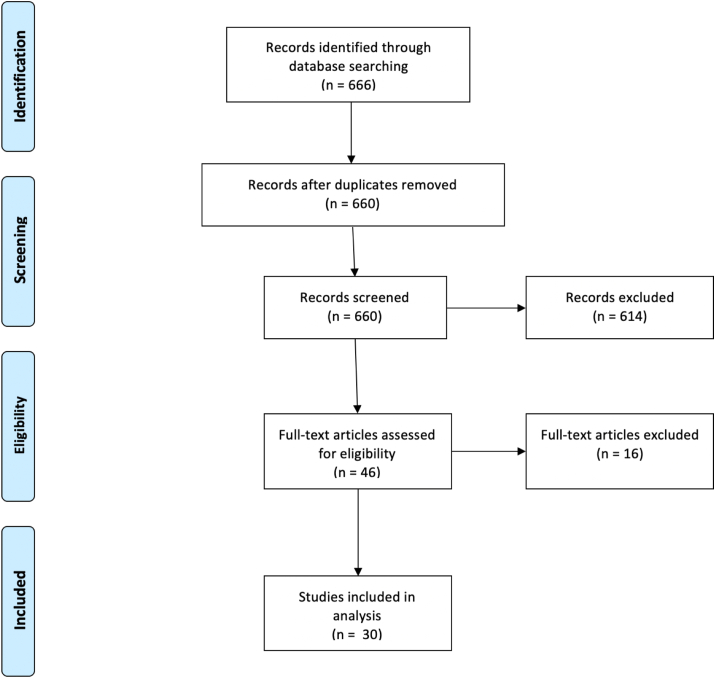

The following exclusion criteria were applied to screen studies: (a) case reports, case series, expert opinions, or other studies with level IV evidence or lower; (b) prior systematic reviews; (c) studies published in languages other than English; (d) studies involving non-human subjects, cadavers, or pediatric patients; (e) basic science or biomechanical studies; (f) studies on unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) or hemiarthroplasty (HA); (g) studies where depressed patients were not analyzed separately but instead were analyzed in aggregate with patients suffering from other psychiatric illnesses. The study selection algorithm and search results are provided in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

2.3. Data extraction & analysis

Data was independently collected by two reviewers (SPV and JFK) and recorded in an excel sheet for analysis. The data extracted included the study design (level of evidence), year of publication, question answered by the study, and the key findings of the study. The two reviewers (SPV and JFK) independently analyzed the collected data. Furthermore, a risk of bias assessment was performed by the same two reviewers (SPV and JFK) for each study prior to inclusion of the study.

2.4. Quality appraisal and risk of bias assessment

Two reviewers (SPV and JFK) analyzed the methodological quality of each study using specific criteria set forth by US Preventive Services Task Force for development of a more evidence-based approach to setting clinical practice guidelines.13 Both the reviewers (SPV and JFK) also performed a risk of bias assessment for each study using the following criteria: (1) Was the selection of patients for inclusion in the study unbiased? (2) Was there systematic exclusion of any single group? (3) Was there significant attrition rate of study participants? (4) Was there a clear description of methodology and techniques in the study? (5) Was there unbiased and accurate assessment of outcomes and complications in the study? (6) Were potential confounding variables and risk factors identified and examined using acceptable statistical techniques? (7) Was the duration of follow-up reasonable for investigated outcomes? (8) Was the population included in the study described adequately? (9) Was the included participant group similar to the population at large that is affected by the condition studied? (10) Were the inclusion and exclusion criteria clearly defined? (11) Was the funding source and role of funder clearly defined in the study? (12) Were there any conflicts of interest identified or easily apparent12,14? Only studies meeting at least ten of the twelve quality criteria above were included for analysis.

Sources of funding

None of the authors received any funding in the development of this manuscript.

3. Results

3.1. Study characteristics

There were 30 studies that met the inclusion criteria. There were 14 studies consisting of Level II evidence and 16 studies consisting of Level III evidence. The aims of the study, methodology, level of evidence, and key findings of each included study are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study question and conclusions.

| Author | Study Design | Level of Evidence | Study Question | Study Methods | Study Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ali et al.15 | Prospective observational study | II | Is there a correlation between preoperative psychological factors and postoperative satisfaction after TKA? | 186 patients who underwent primary TKA filled out Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Visual Analog Pain Scale (VAS) (0–100), and Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) preoperatively and 4 years postoperatively. | 15% of the included patients reported that they were dissatisfied or uncertain with the result of their TKA. Patients with preoperative anxiety or depression had 6 times higher risk of being dissatisfied after TKA compared to those patients without (P < 0.001). |

| Bierke et al.16 | Prospective observational study | II | What is the influence of pain catastrophizing, anxiety and depression symptoms, and somatization dysfunction on the outcome of TKA at mid-term follow-up? | 150 patients were asked to fill out preoperative questionnaire assessing mental parameters such as pain catastrophizing (Pain Catastrophizing Scale), anxiety (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory) (STAI), depressive symptoms and somatization dysfunction (Patient Health Questionnaire). They were then assessed on postoperative pain on numerical rating scale (NRS). | At 5-year follow-up, patients with depressive symptoms and somatization dysfunction had significantly higher pain level both at rest and while walking (P < 0.001) compared to patients without these symptoms. |

| Bistolfi17 | Prospective observational study | II | How does depression influence pain perception after total knee arthroplasty at short term follow-up? | 67 patients who underwent primary TKA were evaluated preoperatively for depression using the Hamilton depression rating scale (HDRS) and pain using NRS. Postoperative outcomes were measured using Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) knee score. | Patients who scored in the mild depression range on the HDRS scale were found to be more likely to report more pain (P < 0.001) and have lower HSS score at 1 year postoperatively (P < 0.001) compared to those who scored in the normal range on the HDRS scale. |

| Blackburn et al.18 | Prospective observational study | II | Is there an association between anxiety/depression and knee pain/function after TKA? | 40 patients undergoing primary TKA completed Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale and Oxford Knee Scores (OKS) preoperatively and postoperatively at 3 months and 6 months. | There was significant improvement in HAD scores postoperatively at 3 months and 6 months. Severity of preoperative anxiety and depression was associated with higher levels of knee disability preoperatively (P = 0.009) and the improved level of anxiety and depression postop was associated with reduction in knee disability at 3 months (P = 0.003) and 6 months (P = 0.006). |

| Duivenvoorden et al.19 | Retrospective database study | III | What is the relationship between preoperative anxiety and depression on patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) after THA and TKA? | 149 THA and 133 TKA patients were asked to fill out HAD scale, KOOS, or Hip disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS) preoperatively and postop 3 months and 12 months after TJA. | The prevalence of anxiety decreased significantly from 27.9% to 10.8% at 12 months postoperatively in hip patients (P < 0.0001), and from 20.3% to 14.8% in knee patients (P < 0.05). Depressive symptoms decreased significantly from 33.6% to 12.1% at 12 months postoperatively in hip patients (P < 0.0001), and from 22.7% to 11.7% in knee patients (P < 0.0001). However, in both THA and TKA patients, preoperative depressive symptoms predicted smaller changes in HOOS or KOOS subscales and patients were less satisfied 12 months postoperatively. |

| Etcheson et al.20 | Prospective observational study | II | What is the pain perception and opioid consumption among patients with and without major depressive disorder (MDD) who underwent THA or TKA? | 48 patients with MDD underwent THA and 68 patients with MDD underwent TKA. Opioid consumption and pain levels of these patients were compared to 45 patients without MDD who underwent THA and 61 patients without MDD who underwent TKA. | Patients with MDD who underwent THA or TKA rated higher pain intensity than those without MDD but this was not statistically significant. Patients with MDD who underwent TJA consumed significantly more opioids than those without MDD who underwent TJA (P < 0.05). The length of stay was similar between the two groups. |

| Fehring et al.21 | Retrospective database study | III | Is depression a modifiable risk factor that needs to be corrected prior to TJA? | Patients scheduled for TKA or THA were routinely complete the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) preoperatively and 1 year postoperatively. This data was retrospectively analyzed. | 65 of 282 patients in the study period scored greater than 10 on PHQ-9, indicating moderate depressive symptoms. Of these patients, 88% improved to <10 postop (P = 0.0012). 10 patients had severe depressive symptoms preoperatively and 9 of them improved to <10 postop (P = 0.10). There were no significant differences in postoperative HOOS and KOOS scores in depressed vs nondepressed patients. Depression does not need to be treated to a certain threshold prior to TJA based on the results of this study. |

| Filardo et al.22 | Retrospective analysis of routinely collected registry data | III | What is the relationship between kinesiophobia and outcome after TKA? Are the outcomes driven by anxiety and depression? | 200 patients who underwent TKA were evaluated for kinesiophobia using the Tampa scale and they were evaluated for depression and anxiety the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and STAI respectively. Their postoperative outcomes were assess using NRS for pain and clinical outcomes using the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) score at 12 months. | While age, body mass index (BMI), education level, number of painful joints, and years of symptoms did not affect outcomes, depressive symptoms and kinesiophobia were synergistically correlated with negative outcome on WOMAC scale (P < 0.0005) at 12-month follow up. This study suggests that kinesiophobia is an independent risk factor for negative outcome after TKA but also has a synergistic effect with depression. |

| Gold et al.23 | Prospective observational study | II | What is the relationship between depression and risk of readmission after TJA? | Retrospective data from California Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project database were analyzed for odds of 90-day readmission after hospital discharge for primary TKA or THA. 132,422 TKA patients and 65,071 THA patients were included for analysis. | Overall 90-day readmission rates were 8% for both THA and TKA. The odds of readmission were 21–24% higher for depressed patients (odds ratio for TKA: 1.21, odds ratio for THA: 1.24, P < 0.001 for both) compared to non-depressed patients. |

| Gold et al.24 | Retrospective cohort study | III | What is the relationship between mental health disorder (substance use, alcohol use, or depression) and postoperative complications after TKA? | A total of 11,403 TKA patients were identified in the database and 2073 of them (18%) had mental health disorders. Univariate and multivariate regression analysis was performed to determine if there was an association between mental health disorders and complications. | Patients with depression were more likely to experience mechanical failure of implants (2.3% vs 1.1% P < 0.001). Patients with depression and substance use disorder were found to have four-fold increased risk for prosthetic joint infection (PJI) compared to substance use disorder alone (P < 0.001). |

| Halawi et al.25 | Retrospective analysis of routinely collected data | III | What is the association between depression and patient reported outcomes after TKA or THA? | 469 patients who had undergone elective primary TJA completed the Short Form-12 (SF-12) for assessment of mental health and WOMAC scores at 4 and 12 months postoperatively were analyzed. | Patients with depression but good baseline mental health achieved gains in PROMs similar to those of normal controls (P > 0.05). There was no difference in WOMAC gains between the group with no depression and good mental health and the group with depression and good mental health at 4 and 12 months. The group with no depression and poor mental health had the highest WOMAC gains (p < 0.001). Compared with the group with no depression and poor mental health, the WOMAC gains in the group with depression and poor mental health were significantly lower at 12 months (p = 0.007). |

| Halawi et al.26 | Retrospective analysis of routinely collected registry data | III | Are there any differences in outcomes after TJA between treated and untreated depressed patients? | 749 patients who under TKA or THA were asked to self-report a history of depression at the time of surgery. The primary outcomes were measured using SF-12, WOMAC, and University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) activity rating scale 12 months postoperatively. | Compared to patients who reported being treated for depression, those with untreated depression had lower baseline SF-12 mental health scores but there were no differences in PROMs at 12 months postoperatively. Depression treatment did not affect patients' perception of activity limitation. |

| Hassett et al.27 | Retrospective analysis of routinely collected registry data | III | Are there changes in depressive and anxiety symptoms after lower extremity TJA? | 1448 patients who underwent primary TJA were evaluated for pain intensity using the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), functional status using WOMAC, and depressive and anxiety symptoms using HAD scale preoperatively and 6 months postoperatively. | Improvement in pain and physical function from baseline to 6 months postoperatively was associated with improvement in depressive and anxiety symptoms (P < 0.001). Greater decreases in overall body pain were associated with lower depression scores at 6 months (P < 0.001). Even though THA patients reported significantly higher overall body pain scores than TKA patients preoperatively, TKA patients reported significantly higher overall body pain scores than THA patients 6 months postoperatively (P < 0.001). |

| Hirschmann et al.28 | Prospective observational study | II | Do preoperative psychological factors affect subjective and objective outcomes after TKA at short term follow-up? | 104 patients undergoing primary TKA were investigated for depression and anxiety using BDI and STAI respectively. The Knee Society Clinical Rating System (KSS) and WOMAC scores were measured preoperatively and postop 12 months after surgery. | More depressed patients showed higher pre and postoperative WOMAC pain scores (P < 0.05) but there was no difference in change in scores compared to non-depressed patients. |

| Jones et al.29 | Prospective observational study | II | Do anxiety and depression levels of patients undergoing TKA affect their outcomes in the mid and long term? | 104 patients undergoing TKA were asked to fill out HAD scale to record psychological status and OKS and KSS to record functional outcomes after surgery at 1 year and 7 years postop. | 44% of the included patients had abnormal anxiety or depression score. Mean anxiety and depression scores improved at 6 weeks and 1 year postoperatively (P < 0.001). They deteriorated at 7 years postoperatively but not to baseline level prior to surgery (P < 0.001). Similarly, KSS and OKS improved at 6 weeks and 1 year postoperatively and slightly deteriorate at 7 years postop but not to baseline levels. This study showed that TKA positively influences all outcome measures rather than recovery being negatively influenced by preoperative states. |

| Kohring et al.30 | Prospective observational study | II | Is there a difference in patient reported outcome measures between nondepressed, medically treated depressed, and untreated depressed patients undergoing TJA? | A retrospective review of 271 TJA patients was performed from 2014 to 2016. Patient reported outcome measurement information system (PROMIS) scores were measured for patients preoperatively and postoperatively at 1 year. | Untreated depressed patients experienced smaller gains in physical function scores compared to nondepressed patients (P = 0.020). Furthermore, untreated depressed patients experienced smaller gains in physical function compared to treated depressed patients (P = 0.015). This study concluded that medical treatment of depressed patients may lead to outcomes equivalent to nondepressed patients after TJA. |

| Namba et al.31 | Retrospective cohort study | III | What preoperative factors increase the risk of increased opioid consumption after TKA? | A retrospective review of 23,726 patients who underwent TKA was conducted. Multivariate regression analysis was performed to determine risk factors for greater opioid use. | Depression, in addition to other factors, was associated with higher number of opioid prescriptions (Odds ratio: 1.20, P-value < 0.001) at 6–9 months postoperatively. |

| Pan et al.32 | Retrospective cohort study | III | What is the relationship between psychiatric disorders and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing primary TKA? | National Inpatient Sample (NIS) data was used to analyze 7,153,750 who underwent TKA in the US between 2002 and 2014. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to determine whether psychological comorbidities were independent risk factors for postoperative complications and pain. | Patients with depression had higher cost compared to patients without ($45,883.02 vs $44,573.65, P < 0.001). Patients with depression had a shorter hospital stay than nondepressed patients (3.42 vs 3.41, P < 0.001). Depression patients had higher odds ratios (ORs) for acute renal failure, anemia, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, and stroke but lower ORs for cardiac and central nervous system complications and inpatient mortality compared to nondepressed patients (P < 0.05 for all). |

| Perez-Prieto et al.33 | Retrospective analysis of registry data | III | What is the quality of life, function, pain, and satisfaction in patients with and without depression undergoing TKA surgery at short term follow-up? | 716 patients were enrolled into depressed (200) and nondepressed (516) cohorts. Patient outcomes were measures using Short Form-36 (SF-36), KSS, WOMAC, and VAS scores preoperatively and 1 year postop. | Depressed patients had poorer baseline scores on almost every scale and had lower function scores (KSS, WOMAC) at 1 year postop compared to non-depressed patients (P = 0.001). Depressed patients had higher VAS scores at 1 year postop compared to nondepressed patients (P = 0.002). 86.8% of depressed patients had lower scores on the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) 1 year after surgery, suggesting that they “had recovered” from their depression (P < 0.001). |

| Petrovic et al.34 | Prospective cohort study | II | What are the risk factors for development of postoperative pain following THA? | 90 patients with complaints of postoperative pain following cemented THA were divided into two groups based on postop pain: patients scoring >5 on NRS, patients scoring less than 5 on NRS (control). Hamilton scale for anxiety and depression were used for psychological evaluation. | Factors associated with development of postoperative pain were depressive symptoms (OR 7.33, P = 0.030), in addition to anxiety (OR 6.01, P = 0.009), preoperative severe pain (OR 2.64, P < 0.001), female gender (OR 4.91, P < 0.001) and type D personality (OR 2.81, P = 0.030). |

| Rasouli et al.35 | Retrospective case control study | III | What is the impact of concomitant psychiatric disorders on hospitalization charges and complications in patients undergoing TJA? | TJA database was queried for patients who underwent THA or TKA in 2009. Records of patients with clinical diagnosis of depression or anxiety were analyzed for hospital charges, length of stay and complications. | There were 128 TKA patients and 62 THA patients who had preoperative clinical diagnosis of anxiety or depression. Rate of complications was higher in patients with preoperative anxiety or depression compared to controls (29% vs 15.5%, P < 0.001). These complications included postoperative anemia, infection, hematoma, wound dehiscence, and device-related issues. There was no difference in length of stay between the two groups. Hospitalization charges were higher in depressed TKA patients vs nondepressed TKA patients ($55,670 vs $52,270, P < 0.001) but there was no difference in charges for THA patients with or without depression. |

| Riddle et al.36 | Retrospective analysis of routinely collected database data | III | Are specific psychological disorders or pain-related beliefs associated with poor outcome after TKA? | 140 patients undergoing TKA were asked to complete PHQ-8 for evaluation of depression severity and Generalized Anxiety and Pain Disorder modules from PRIME-MD. Patients also completed Tampa scale for kinesiophobia, Arthritis Self-efficacy Scale, Pain Catastrophizing Scale, WOMAC pain and function questionnaires preoperatively and 6 months postoperatively. | Pain catastrophizing was the only consistent predictor of poor WOMAC pain outcome (P = 0.005). Psychological disorders such as depression and anxiety were not associated consistently with poor WOMAC pain and no psychological predictors were associated with poor WOMAC function. |

| Riediger et al.37 | Prospective observational study | II | What is the relationship between depression, somatization, and pain beliefs on outcomes after THA? | 79 patents who were scheduled for elective THA were asked to fill out HAD scale, pain beliefs questionnaire (PBQ), Screening of Somatoform Disorders (SOMS-2), SF-36, and WOMAC preoperatively and 8 weeks postoperatively. | Depressed patients had lower WOMAC preoperatively (30 vs 45, P < 0.05) and postoperatively (72 vs 85, P < 0.05) compared to nondepressed patients but the change in WOMAC scores was similar between the two groups. |

| Schwartz et al.38 | Prospective observational study | II | Does psychotherapy prior to surgery have an effect on outcomes after THA in depressed patients? | Retrospective review was performed of 3 patient cohorts who underwent THA: no depression (158,427), depression and psychotherapy (1919), and depression without psychotherapy (10,912). Outcomes were analyzed to assess resource utilization, surgical and medical complications, narcotic use, and 1 and 3-year revision rates. | Depressed patients who did not receive psychotherapy were more likely to be discharged to inpatient rehab facility (IPR) (OR 1.28, P < 0.001), require 2 or more narcotic prescriptions (OR 1.2, P = 0.004), have continued narcotic requirements 1 year after surgery (OR 1.23, P < 0.001), undergo revision at 1 year (OR 1.74, P = 0.006) and 3 years (OR 1.92, P = 0.021) compared to depressed patients who received psychotherapy. When compared to nondepressed patients, patients with depression (whether or not they received psychotherapy) had greater odds of presenting to ED, nonhome discharge. Depressed patients without psychotherapy had higher odds of readmission at 30 days and 90 days and prolonged length of stay compared to nondepressed patients (P < 0.05). This was not true for depressed patients with psychotherapy. |

| Stundner et al.39 | Retrospective cohort study | III | What is the relationship between depression/anxiety and postoperative outcomes after TJA? | National Inpatient Sample data was used to analyze 1,212,493 patients who underwent TJA between 2000 and 2008. Multiple regression analysis was performed to determine if depression or anxiety were risk factors for certain outcome measures. | Patients with depression had higher hospital charges ($14,438 vs $13,981, P < 0.001), greater length of stay (4.03 vs 3.93, P < 0.001), and higher rates of non-routine discharge (P < 0.0001) compared to patients without depression. The depressed group preoperatively had lower odds of in-hospital mortality compared to nondepressed group (OR 0.53, P = 0.0147). The risk of developing a major complication was also lower in patients with depression compared to those without (OR 0.95, P = 0.0738). |

| Tarakji et al.40 | Retrospective analysis of registry data | III | Does arthroplasty improve patients' depressive symptoms by relieving pain? | 146 patients who underwent primary TKA or THA were retrospectively analyzed. They were grouped into depressed and nondepressed groups based on their preoperative mental component summary (MCS), with MCS < 42 defining depression. Their outcomes were evaluated using the SF-36 results at 3 months and 1 year postoperatively. | The MCS scores for depressed group improved from their level, with mean change of 10.76 (P < 0.001). Proportion of depressed group with MCS <42 decreased from 100% to 33.3% 1 year after surgery. In contrast, the change in MCS score for nondepressed group was not significant. The depressed group had significantly lower physical function subscale and role physical subscale scores on SF-36 compared to nondepressed group (P < 0.001) but the magnitude of change in scores after surgery remained the same between the two groups. |

| Torres-Claramunt et al.41 | Retrospective cohort study | III | Do depressed patients feel more pain in the immediate postoperative period after TKA compared to non-depressed patients? | 803 patients undergoing primary TKA were asked to complete Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) preoperatively and they were divided into depressed (GDS > 5) or nondepressed (GDS < 5) groups. The patients completed KSS, VAS, WOMAC, SF-36 forms preoperatively and 1 year after surgery. | 48 patients out of 803 included were depressed. Depressed patients scored worse in functional outcome scores preoperatively and 1 year after surgery (P = 0.00) but the improvement obtained was similar between the two groups with the exception of mental domain of SF-36. Depressed patients obtained more improvement in the mental domain of SF-36 than nondepressed patients (P < 0.001). |

| Vakharia et al.42 | Prospective cohort study | II | Do depressed patients undergoing primary TKA have longer inpatient length of stay (LOS), higher readmission rates, medical complications, and higher costs compared to nondepressed patients? | 23,061 depressed patients were matched to 115,015 nondepressed patients. Primary outcomes such a LOS, 90-day readmission rates, medical complications, and costs were analyzed for the two groups. | Patients with depressive disorders had longer LOS (6.2 days vs 3.1 days, P < 0.0001), higher odds of readmission (15.5% vs 12.1%, P < 0.001), medical complications (5% s 1.6%, P < 0.0001), higher day of surgery costs ($12,356.59 vs $10,487.71, P < 0.0001), and 90-day costs ($23,386.17 vs $22,201.43, P < 0.0001) compared to nondepressed patients. |

| Visser et al.43 | Retrospective analysis of routine collected database data | III | What is the impact of major depressive disorder on functional outcomes after TKA? | 260 patients undergoing TKA were asked to complete SF-36, WOMAC, KSS, PHQ preoperatively and 12 months postoperatively. Multiple regression was performed to see if there was any correlation between depressive symptoms and outcomes. | Both depressed and nondepressed patients had similar improvement in functional scores at 1 year postoperatively from baseline. Depression was associated with poorer preoperative and postoperative KSS and WOMAC scores (P < 0.05). |

| Prospective cohort study | II |

3.2. Length of stay and readmission rates in depressed patients

The evidence regarding length of stay in depressed patients is inconclusive. Stundner et al. showed that depressed patients had greater length of stay compared to non-depressed patients (4.03 vs 3.93, P < 0.001).39 These results were corroborated by Vakharia et al. who also reported greater length of stay for depressed patients (6.2 days vs 3.1 days, P < 0.0001).43 Schwartz et al. reported higher odds of length of stay longer than 3 days for depressed patients compared to non-depressed patients (OR 1.13, P < 0.001).38 In contrast, Pan et al. in their analysis of 7,153,750 patients who underwent TKA, found that length of stay was slightly shorter for depressed patients compared to non-depressed patients (3.42 vs 3.41, P < 0.001).32 Similarly, Rasouli et al. reported that there was no difference in length of stay between depressed and non-depressed patients in their retrospective study of 190 patients who underwent primary TJA.35

There were three studies that investigated the readmission rate of depressed and non-depressed patients undergoing TJA. Gold et al. in their retrospective analysis of 132,422 TKA patients and 65,071 THA patients, found that 90-day readmission rates were significantly higher for depressed patients compared to non-depressed patients (odds ratio (OR) for TKA: 1.21, OR for THA: 1.24, P < 0.001 for both).23 Vakharia et al. corroborated these results in their retrospective cohort study of 23,061 depressed patients and 115,015 controls who underwent TKA.42 They found that depressed patients had higher odds of readmission within 90 days of TKA (15.5% vs 12.1%, P < 0.001).42 Schwartz et al. also reported similar findings in their retrospective cohort study of 171,258 patients who underwent THA, with higher odds of 30-day (OR 1.26, P < 0.001) and 90-day (OR 1.26, P < 0.001) readmission in depressed patients compared to non-depressed patients.38

Two studies reported that depressed patients had higher likelihood of non-home discharge after TJA compared to non-depressed patients. Schwartz et al. reported that patients with depression had greater odds of being discharged to inpatient rehab facility instead of home (OR 1.28, P < 0.001).38 Similarly, Stundner et al. reported that patients with depression had lower odds of routine discharge compared to non-depressed patients (OR 0.78, P < 0.0001).39

3.3. Postoperative complications in depressed patients

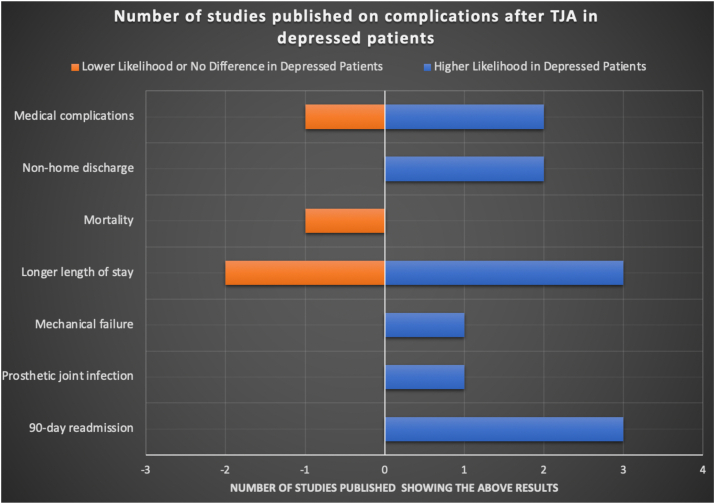

The evidence indicates that depressed patients may be at slightly higher risk for complications following TJA compared to non-depressed patients. Gold et al. reported that patients with depression were more likely to experience mechanical failure of implants (2.3% vs 1.1% P < 0.001).24 In addition, they also reported that patients with depression and substance use disorder were 4 times more likely to acquire prosthetic joint infection than patients with substance use disorder alone (P < 0.001).24 Rasouli et al. found that patients with preoperative anxiety or depression had a higher rate of complications such as postoperative anemia, infection, hematoma, wound dehiscence, and device-related issues compared to controls (29% vs 15.5%, P < 0.001).35 Vakharia et al. also reported a higher rate of medical complications after TJA for depressed patients compared to non-depressed patients (15.5% vs 12.1%, P < 0.001).42 However, this increased risk for complications does not seem to translate to higher mortality rate. Stundner et al. reported that the depressed cohort who underwent TJA had lower odds of in-hospital mortality compared to non-depressed cohort (OR 0.53, P = 0.0147).39 These results are summarized in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Complication profile of depressed patients compared to non-depressed patients undergoing TJA.

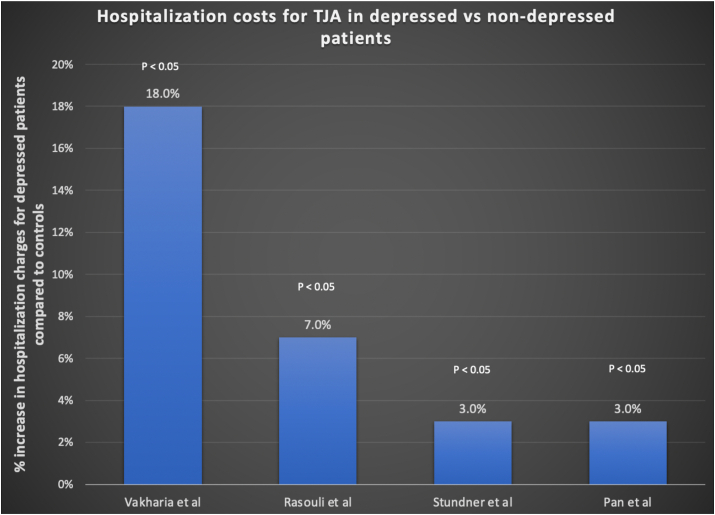

3.4. TJA costs in depressed patients

In line with the findings of related to increased readmission and complication rates, the evidence regarding hospitalization charges suggests that depressed patients incur higher hospitalization costs than non-depressed patients. Pan et al. reported that patients with depression who underwent primary TKA in the United States incurred significantly higher hospitalization costs than those without depression ($45,883 vs $ 44,573, P < 0.001).32 Rasouli et al. also reported that hospitalization charges were higher in depressed patients who underwent TKA compared to non-depressed patients ($55,670 vs $52,270, P < 0.001) but there was no difference in charges for THA patients with or without depression.35 Stundner et al. assess both THA and TKA patients and reported that patients with depression had higher hospital charges ($14,438 vs $13,981, P < 0.001) compared to non-depressed patients.39 Vakharia showed that depressed patients who underwent TKA not only incurred higher day of surgery costs ($12,356.59 vs $10,487.71, P < 0.0001) but also 90-day costs ($23,386.17 vs $22,201.43, P < 0.0001) compared to non-depressed patients.42 These results are summarized in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Average hospitalization costs for TJA for depressed versus non-depressed patients.

3.5. Effect of depression on TJA outcomes

Depression has a variable impact on TJA outcomes. Ten studies included in this review suggest that depression is a predictor of patient dissatisfaction, persistent pain and narcotic use, and poor patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) after TJA. Ali et al. in their prospective study of 186 patients who underwent TKA, reported that patients with preoperative anxiety or depression had 6 times higher risk of being dissatisfied after TKA compared to patients without anxiety or depression (P < 0.001).15 With regard to pain, Bierke et al. in their prospective study of 150 patients who underwent TKA, reported that patients with depressive symptoms and somatization dysfunction had significantly higher pain level both at rest and while walking compared to patients without these symptoms at 5 years post-op (P < 0.001). These results were corroborated by Bistolfi et al. and Petrovic et al. who reported that depressed patients undergoing TJA were more likely to report persistent pain postoperatively.17,34 This increased pain level may translate to increased opioid consumption. Etcheson et al. in their retrospective study of 116 TJA patients, reported that patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) consumed significantly more opioids than those without MDD (P < 0.05).20 Similarly, Namba et al. reported in a retrospective analysis of 23,726 patients who underwent TKA that depression was associated with higher number of opioid prescriptions at 6–9 months postoperatively (OR: 1.20, P-value < 0.001).31 Schwartz et al. found that depressed patients had higher odds of requiring narcotic prescriptions at 1 year after surgery in their retrospective study (OR 1.23, P < 0.001).38

Depression may be a predictor of worse PROMs postoperatively. Filardo et al. in their prospective study of 200 patients who underwent TKA, found that depressive symptoms and kinesiophobia were synergistically correlated with negative outcome on Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) score at 12-month follow up (P < 0.0005).22 Similarly, Perez-Prieto et al. found that depressed patients had poorer baseline Knee Society Score (KSS) and WOMAC score and 1-year postoperative scores compared to non-depressed patients (P = 0.001).33 Furthermore, they reported that depressed patients had higher Visual Analog Scale (VAS) pain scores at 1 year postoperative compared to nondepressed patients (P = 0.002).33 Kohring et al. also showed that untreated depressed patients experienced smaller gains in physical function scores compared to nondepressed patients in their retrospective study of 271 TJA patients (P = 0.020).30

Five studies included in this review suggest that while depressed patients may have poorer preop and postoperative PROMs, the gains they experience in functional outcome scores after TJA are similar to gains experienced by patients without depression. Halawi et al. conducted a retrospective analysis of 469 patients who had undergone elective primary TJA and found that patients who had good baseline mental health but were diagnosed with depression achieved gains in PROMs similar to those of normal controls (P > 0.05).44 Similarly, Hirschmann et al. and Riediger et al. found that even though depressed patients had worse WOMAC scores preoperatively and postoperatively compared to non-depressed patients (P < 0.05 for both studies), the change in WOMAC scores was similar between the two groups.28,37 Tarakji et al. also showed that while the depressed cohort had lower physical function subscale scores on the Short Form-36 (SF-36) postoperatively compared to non-depressed group (P < 0.001), the magnitude of change in scores after surgery was the same for the two groups of patients after TJA.40 Visser et al. in their prospective study of 260 patients who underwent TJA, reported that both depressed and non-depressed patients had similar improvement in functional outcome scores (SF-36, WOMAC, KSS) at 1 year post-op from baseline.43

One study suggested that there is no difference in functional outcome scores between depressed and non-depressed patients. Riddle et al. in their prospective study of 140 patients who underwent TKA, reported that pain catastrophizing was the only consistent predictor of poor WOMAC pain outcome post-op (P = 0.005).36 Psychological disorders such as depression and anxiety were not associated consistently with poor WOMAC pain and no psychological predictors were associated with poor WOMAC function.36

One study showed that depressed patients may experience more gains than non-depressed patients after TJA. Torres-Claramunt et al. conducted a prospective study of 803 patients undergoing primary TKA and reported that depressed patients scored worse in functional outcome scores preop and 1 year after surgery (P = 0.00) but the improvement obtained was similar between the two groups with the exception of mental domain of SF-36.41 Depressed patients obtained more improvement in the mental domain of SF-36 than nondepressed patients (P < 0.001).41

3.6. Effect of TJA on depression symptoms

Evidence conclusively shows that TJA improves depressive symptoms and anxiety in patients with depression or anxiety. Blackburn et al. conducted a prospective study of 40 patients undergoing primary TKA and reported that there was significant improvement in Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scores postoperatively at 3 months and 6 months after TKA.18 Severity of preoperative anxiety and depression was associated with higher levels of knee disability preop (P = 0.009) and the improved level of anxiety and depression postoperatively was strongly correlated with reduction in knee disability at 3 months (P = 0.003) and 6 months (P = 0.006).18 Hassett et al. corroborated these findings in their prospective study of 1448 TJA patients when they reported that improvement in physical function and pain, as measured by WOMAC and Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) respectively, from baseline to 6 months postoperatively was associated with improvement in depressive and anxiety symptoms (P < 0.001).27 Furthermore, they found that greater decreases in overall body pain was associated with lower depression scores at 6 months (P < 0.001).27 Jones et al. conducted a prospective study of 104 patients undergoing TKA and found that 44% of the included patients had abnormal anxiety or depression score preoperatively.29 Mean anxiety and depression scores improved at 6 weeks and 1 year postoperatively (P < 0.001) and deteriorated at 7 years postoperatively but not to baseline preoperative level.29 Torres-Claramunt et al. showed that depressed patients obtained more improvement in the mental domain of SF-36 than non-depressed patients (P < 0.001) in their prospective study of 803 TKA patients.41

Studies show that prevalence of depression may also decrease with TJA. Duivenvoorden et al. conducted a prospective study of 149 THA and 133 TKA patients and found that depressive symptoms decreased significantly from 33.6% to 12.1% at 12 months postoperatively in hip patients (P < 0.0001), and from 22.7% to 11.7% in knee patients (P < 0.0001).19 Similarly, Perez-Prieto et al. in their prospective study found that of the 200 patients who were enrolled into the depressed cohort, 86.8% showed resolution of depressive symptoms 1 year after TKA (P < 0.001).33 Tarakji et al. also found that the proportion of depressed patients with mental component summary (MCS) score less than 42 decreased from 100% of the depressed cohort preop to 33.3% of the depressed cohort (P < 0.05) 1 year after TJA while the change in MCS score after TJA for the non-depressed cohort was not significant.40 Fehring et al. performed a retrospective analysis of patients who underwent TJA and found that 65 of 282 patients scored greater than 10 on patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) preop, indicating moderate depressive symptoms.21 Of these patients, 88% improved to <10 postoperative (P = 0.0012), indicating improvement in depressive symptoms.21 Ten patients had severe depressive symptoms preop and 9 of them improved to <10 postoperative (P = 0.10), again indicating resolution of depressive symptoms after TJA.21 These results are summarized in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Effect of depression on TJA outcomes and vice versa.

3.7. Does depression need to Be treated prior to TJA?

Three studies assessed whether depression needs to be treated to a certain threshold prior to TJA. There is inconclusive evidence to suggest that treating depression preoperatively will lead to improved outcomes after TJA. Halawi et al. performed a retrospective analysis of 749 patients who underwent TKA or THA and found that compared to patients who reported being treated for depression preop, patients with untreated depression had lower preop SF-12 mental health scores but experienced the same improvements in PROMs at 12 months postoperatively after TJA.26 They concluded that depression treatment did not affect patients’ perception of activity limitation after TJA.

In contrast, Kohring et al. in their retrospective review of 271 TJA patients, reported that untreated depressed patients experienced smaller gains in physical function scores compared to nondepressed patients undergoing TJA (P = 0.020).30 Furthermore, they reported that untreated depressed patients experienced smaller gains in physical function compared to treated depressed patients (P = 0.015).30 They concluded that medical treatment of depressed patients preoperatively may lead to outcomes equivalent to those of nondepressed patients. Schwartz et al. also showed that treating depressed patients with psychotherapy preop may improve their postoperative outcomes after TJA.38 In their retrospective review of 171,258 TJA patients, depressed patients who did not receive psychotherapy were more likely to be discharged to inpatient rehab facility (IPR) (OR 1.28, P < 0.001), require 2 or more narcotic prescriptions (OR 1.2, P = 0.004), have continued narcotic requirements 1 year after surgery (OR 1.23, P < 0.001), undergo revision at 1 year (OR 1.74, P = 0.006) and 3 years (OR 1.92, P = 0.021) compared to depressed patients who received psychotherapy.38

4. Discussion

There are several important findings in this systematic review. First, the results showed that depression increases the risk of persistent pain, dissatisfaction, and complications after TJA. Second, depressed patients may incur higher costs than non-depressed patients undergoing TJA. Third, depressed patients may have worse preop and postoperative PROMs, but the gains they experience in subjective outcome measures after TJA are equivalent to gains experienced by non-depressed patients. Fourth, depressed patients may experience improvement in their depressive symptoms after TJA. Fifth, there is insufficient evidence to suggest that treating depression preoperatively will affect postoperative outcomes after TJA.

Identifying the depressed patient prior to TJA surgery is advisable. Based upon the results of this review, depression is a comorbidity which may have substantial impact on the complications, outcomes, and costs associated with TJA. Counseling these patients in the preoperative period may help them to participate more fully in the shared decision-making process and potentially reduce the risks of adverse outcomes associated with depression. Depressed patients should be informed that while they may have an increased risk for continued pain and dissatisfaction following TJA, they can expect to experience similar improvement in their function compared to patients who do not have depression. Brief discussions such as these can go a long way towards helping set realistic expectations for patients regarding postoperative outcomes. Setting realistic expectations is crucial to the patients’ perceived success of their total joint replacement because recent studies have shown that expectation fulfillment is directly linked to patient satisfaction.45,46 While the literature does not specifically address whether depression itself is a modifiable risk factor, based on this review, it seems reasonable that awareness of the effect of depression on TJA by provider and patient alike may have a beneficial effect on the entire episode of care.

One of the limitations of this review is the heterogeneity of the outcomes measured in the included studies, which prevented us from performing robust statistical analysis of outcomes in depressed patients undergoing TJA. Another limitation of this review is that it only included studies that analyzed depressed patients as a separate group and their outcomes after TJA. It did not include studies in which depressed patients were analyzed as part of a group consisting of patients with other psychiatric illnesses as well. While this was done purposely to isolate the effects of depression on TJA and decrease confounding from other psychosocial factors, this strategy also led to the exclusion of studies that evaluated patients with psychiatric illnesses (including depression) in general. This may have led to the omission of important results pertaining to depressed patients.

Despite the above limitations, one of the strengths of this review is that it consists of studies with higher level of evidence (II and III) and provides a comprehensive review of evidence published to date. The results of this review suggest that TJA is not contraindicated in depressed patients and that this vulnerable patient population may even perceive improvement in their depressive symptoms after TJA. One of the factors worth investigating further in future studies is the effect of depression on long-term outcomes after TJA. The duration of follow-up in all but one of the included studies was short to mid-term. Thus, longer term studies are needed to assess TJA outcomes in this patient population.

5. Conclusion

The results of this review show that depression increases the risk of persistent pain, dissatisfaction, and complications after TJA. Additionally, depressed patients may incur higher costs than non-depressed patients undergoing TJA and may have worse preoperative and postoperative PROMs. However, the gains in function that depressed patients experience after TJA are equivalent to gains experienced by non-depressed patients and depressed patients may experience improvement in their depressive symptoms after TJA. Patient selection for TJA is critical and counseling regarding increased risk for complications is crucial in depressed patients undergoing TJA.

Ethics committee approval

This systematic review of the literature did not require the approval of The Biomedical Institutional Review Board of The Ohio State University.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors received no funding for this study and report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Archibeck M.J., Berger R.A., Jacobs J.J. Second-generation cementless total hip arthroplasty: eight to eleven-year results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(11):1666–1673. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rhee S.J., Kim H.J., Lee C.R., Kim C.W., Gwak H.C., Kim J.H. A comparison of long-term outcomes of computer-navigated and conventional total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101(20):1875–1885. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.19.00257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gunaratne R., Pratt D.N., Banda J., Fick D.P., Khan R.J.K., Robertson B.W. Patient dissatisfaction following total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review of the literature. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(12):3854–3860. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryan S., Goldsmith L.J., Davis J.C. Revisiting patient satisfaction following total knee arthroplasty: a longitudinal observational study. BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2018;19(1):109. doi: 10.1186/s12891-018-2340-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schiffner E., Wild M., Regenbrecht B. Neutral or natural? Functional impact of the coronal alignment in total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg. 2019;32(8):820–824. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1669788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smeekes C., Ongkiehong B., van der Wal B., Wolterbeek R., Henseler J.F., Nelissen R. Large fixed-size metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty: higher serum metal ion levels in patients with pain. Int Orthop. 2015;39(4):631–638. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2605-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brander V., Gondek S., Martin E., Stulberg S.D. The John Insall award: pain and depression influence outcome 5 years after knee replacement surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;464:21–26. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e318126c032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh J.A., Lewallen D. Age, gender, obesity, and depression are associated with patient-related pain and function outcome after revision total hip arthroplasty. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28(12):1419–1430. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1267-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahn A., Snyder D.J., Keswani A. The cost of poor mental health in total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.06.083. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guerini F., Morghen S., Lucchi E., Bellelli G., Trabucchi M. Behav Neurol. 2010;23(3):117–121. doi: 10.3233/BEN-2010-0274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burns P.B., Rohrich R.J., Chung K.C. The levels of evidence and their role in evidence-based medicine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(1):305–310. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318219c171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris R.P., Helfand M., Woolf S.H. Current methods of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: a review of the process. Am J Prev Med. 2020;58(3):316–331. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.01.001. REPRINT OF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vajapey S.P., Blackwell R.E., Maki A.J., Miller T.L. Treatment of extensor tendon disruption after total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(6):1279–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ali A., Lindstrand A., Sundberg M., Flivik G. Preoperative anxiety and depression correlate with dissatisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: a prospective longitudinal cohort study of 186 patients, with 4-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(3):767–770. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bierke S., Häner M., Karpinski K., Hees T., Petersen W. Midterm effect of mental factors on pain, function, and patient satisfaction 5 Years after uncomplicated total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(1):105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bistolfi A., Bettoni E., Aprato A. The presence and influence of mild depressive symptoms on post-operative pain perception following primary total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(9):2792–2800. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3737-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blackburn J., Qureshi A., Amirfeyz R., Bannister G. Does preoperative anxiety and depression predict satisfaction after total knee replacement? Knee. 2012;19(5):522–524. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duivenvoorden T., Vissers M.M., Verhaar J.A.N. Anxiety and depressive symptoms before and after total hip and knee arthroplasty: a prospective multicentre study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21(12):1834–1840. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Etcheson J.I., Gwam C.U., George N.E., Virani S., Mont M.A., Delanois R.E. Patients with major depressive disorder experience increased perception of pain and opioid consumption following total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(4):997–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fehring T.K., Odum S.M., Curtin B.M., Mason J.B., Fehring K.A., Springer B.D. Should depression Be treated before lower extremity arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(10):3143–3146. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Filardo G., Merli G., Roffi A. Kinesiophobia and depression affect total knee arthroplasty outcome in a multivariate analysis of psychological and physical factors on 200 patients. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(11):3417–3423. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-4201-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gold H.T., Slover J.D., Joo L., Bosco J., Iorio R., Oh C. Association of depression with 90-day hospital readmission after total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(11):2385–2388. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gold P.A., Garbarino L.J., Anis H.K. The cumulative effect of substance abuse disorders and depression on postoperative complications after primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(6):S151–S157. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halawi M.J., Cote M.P., Singh H. The effect of depression on patient-reported outcomes after total joint arthroplasty is modulated by baseline mental health. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(20):1735–1741. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.01677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halawi M.J., Gronbeck C., Savoy L., Cote M.P., Lieberman J.R. Depression treatment is not associated with improved patient-reported outcomes following total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:28–31. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hassett A.L., Marshall E., Bailey A.M. Changes in anxiety and depression are mediated by changes in pain severity in patients undergoing lower-extremity total joint arthroplasty. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(1):14–18. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirschmann M.T., Testa E., Amsler F., Friederich N.F. The unhappy total knee arthroplasty (TKA) patient: higher WOMAC and lower KSS in depressed patients prior and after TKA. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(10):2405–2411. doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2409-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones A.R., Al-Naseer S., Bodger O., James E.T.R., Davies A.P. Does pre-operative anxiety and/or depression affect patient outcome after primary knee replacement arthroplasty? Knee. 2018;25(6):1238–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohring J.M., Erickson J.A., Anderson M.B., Gililland J.M., Peters C.L., Pelt C.E. Treated versus untreated depression in total joint arthroplasty impacts outcomes. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(7):S81–S85. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Namba R.S., Singh A., Paxton E.W., Inacio M.C.S. Patient factors associated with prolonged postoperative opioid use after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(7):2449–2454. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.03.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pan X., Wang J., Lin Z., Dai W., Shi Z. Depression and anxiety are risk factors for postoperative pain-related symptoms and complications in patients undergoing primary total knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(10):2337–2346. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pérez-Prieto D., Gil-González S., Pelfort X., Leal-Blanquet J., Puig-Verdié L., Hinarejos P. Influence of depression on total knee arthroplasty outcomes. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(1):44–47. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petrovic N.M., Milovanovic D.R., Ignjatovic Ristic D., Riznic N., Ristic B., Stepanovic Z. Factors associated with severe postoperative pain in patients with total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turcica. 2014;48:615–622. doi: 10.3944/AOTT.2014.14.0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rasouli M.R., Menendez M.E., Sayadipour A., Purtill J.J., Parvizi J. Direct cost and complications associated with total joint arthroplasty in patients with preoperative anxiety and depression. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(2):533–536. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riddle D.L., Wade J.B., Jiranek W.A., Kong X. Preoperative pain catastrophizing predicts pain outcome after knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:798–806. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0963-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riediger W., Doering S., Krismer M. Depression and somatisation influence the outcome of total hip replacement. Int Orthop. 2010;34:13–18. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0688-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwartz A.M., Wilson J.M., Farley K.X., Roberson J.R., Guild G.N., Bradbury T.L. Modifiability of depression's impact on early revision, narcotic usage, and outcomes after total hip arthroplasty: the impact of psychotherapy. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:2904–2910. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stundner O., Kirksey M., Chiu Y.L. Demographics and perioperative outcome in patients with depression and anxiety undergoing total joint arthroplasty: a population-based study. Psychosomatics. 2013;54:149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tarakji B.A., Wynkoop A.T., Srivastava A.K., O'Connor E.G., Atkinson T.S. Improvement in depression and physical health following total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:2423–2427. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torres-Claramunt R., Hinarejos P., Amestoy J. Depressed patients feel more pain in the short term after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25:3411–3416. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-4418-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vakharia R.M., Ehiorobo J.O., Sodhi N., Swiggett S.J., Mont M.A., Roche M.W. Effects of depressive disorders on patients undergoing primary total knee arthroplasty: a matched-control analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:1247–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Visser M.A., Howard K.J., Ellis H.B. The influence of major depressive disorder at both the preoperative and postoperative evaluations for total knee arthroplasty outcomes. Pain Med. 2019;20:826–833. doi: 10.1093/pm/pny107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Halawi M.J., Jongbloed W., Baron S., Savoy L., Williams V.J., Cote M.P. Patient dissatisfaction after primary total joint arthroplasty: the patient perspective. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:1093–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bourne R.B., Chesworth B.M., Davis A.M., Mahomed N.N., Charron K.D.J. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:57–63. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1119-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deakin A.H., Smith M.A., Wallace D.T., Smith E.J., Sarungi M. Fulfilment of preoperative expectations and postoperative patient satisfaction after total knee replacement. A prospective analysis of 200 patients. Knee. 2019;26(6):1403–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2019.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]