Abstract

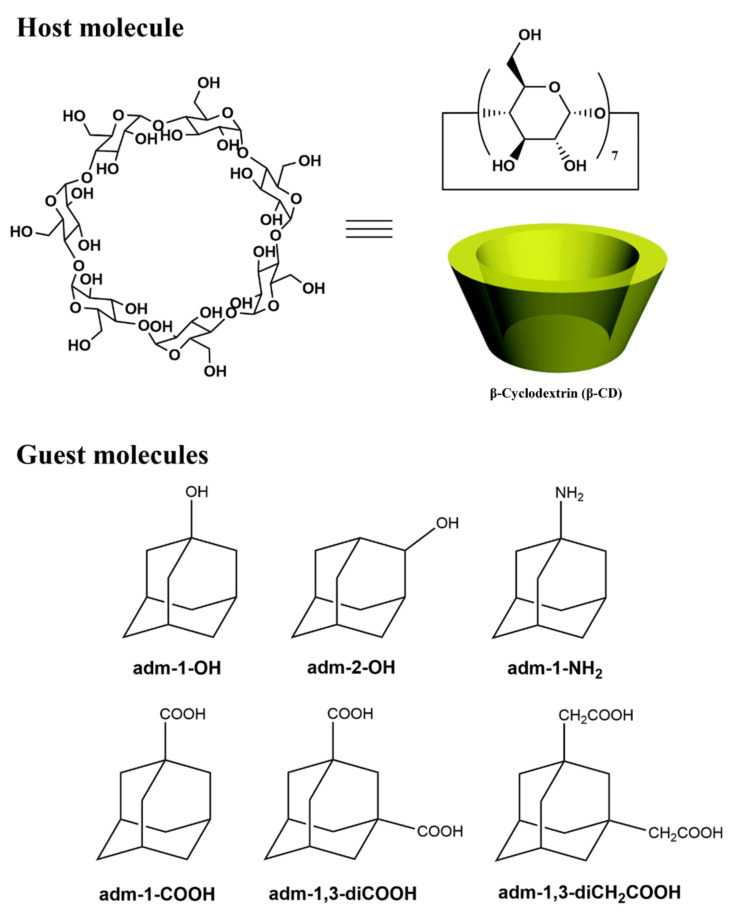

Understanding the host–guest chemistry of α-/β-/γ- cyclodextrins (CDs) and a wide range of organic species are fundamentally attractive, and are finding broad contemporary applications toward developing efficient drug delivery systems. With the widely used β-CD as the host, we herein demonstrate that its inclusion behaviors toward an array of six simple and bio-conjugatable adamantane derivatives, namely, 1-adamantanol (adm-1-OH), 2-adamantanol (adm-2-OH), adamantan-1-amine (adm-1-NH2), 1-adamantanecarboxylic acid (adm-1-COOH), 1,3-adamantanedicarboxylic acid (adm-1,3-diCOOH), and 2-[3-(carboxymethyl)-1-adamantyl]acetic acid (adm-1,3-diCH2COOH), offer inclusion adducts with diverse adamantane-to-CD ratios and spatial guest locations. In all six cases, β-CD crystallizes as a pair supported by face-to-face hydrogen bonding between hydroxyl groups on C2 and C3 and their adjacent equivalents, giving rise to a truncated-cone-shaped cavity to accommodate one, two, or three adamantane derivatives. These inclusion complexes can be terminated as (adm-1-OH)2⊂CD2 (1, 2:2), (adm-2-OH)3⊂CD2 (2, 3:2), (adm-1-NH2)3⊂CD2 (3, 3:2), (adm-1-COOH)2⊂CD2 (4, 2:2), (adm-1,3-diCOOH)⊂CD2 (5, 1:2), and (adm-1,3-diCH2COOH)⊂CD2 (6, 1:2). This work may shed light on the design of nanomedicine with hierarchical structures, mediated by delicate cyclodextrin-based hosts and adamantane-appended drugs as the guests.

Keywords: cyclodextrin, adamantane derivatives, bio-conjugation, host–guest interaction, crystal structure

1. Introduction

Cyclodextrins (CDs) are a class of semi-natural cyclic molecular entities featuring five or more α-D-glucopyranoside units in a ring linked by α-1,4-glycosidic bonds [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Among this rich class of cyclic oligosaccharides, α-/β-/γ- CDs are widely studied as hosts for a variety of organic molecular guests because of their suitable size, amphiphilic structures, and good availability. Compared to other synthetic host systems, e.g., crown ethers [7,8,9], calixarenes [10,11,12], cucurbiturils [9,13,14], and pillararenes [15,16,17], CDs are less toxic and/or exhibit good water solubility and biocompatibility [11,18]. Their facile covalent modification also renders them highly promising candidates as functional delivery systems [19,20,21,22].

Aside from the covalent functionalization, the capability of pristine CDs as hosts to encapsulate a large number of organic species forms the basis of many practical applications in the pharmaceutical formulation [19,20,23,24], cosmetics [25], environmental remediation [26,27,28], agriculture, and food industry [29]. This originates from the unique hydrophobic inner cavity and hydrophilic outer space of CDs, with the latter also critical for imparting solubility to the otherwise less soluble organic species via inclusion [1,30,31]. These encapsulated species can be subsequently released on-demand with external stimuli, such as competitive solvent association, light-/heat-triggered conformation switch, and chemical stimuli (e.g., redox reactions) [19,20,23,32,33,34,35].

Intrigued by these highly favorable traits of CDs, a huge body of work has been done toward the efficient hierarchical catch-release systems through facile host–guest hybridization to harness the beneficial properties of both CDs and the guests [23,31,32,36,37]. The most widely studied host and guest pair feature β-CD and adamantane derivatives mainly due to their wide availability and good size match [23,38,39].

We have a keen interest in developing β-/γ-cyclodextrin encapsulated antiangiogenic drugs (sorafenib and regorafenib) to boost their bioavailability [31,40], as well as sophisticated systems based on polyethylenimine (PEI)-tethered CDs and adamantane-appended guests toward efficient drug delivery systems [34,41,42]. For example, we have recently reported that, by associating cleavable cationic PEI-tethered β-CD and an array of adamantane-appended polyethylene glycols (PEGs) carrying folate for active tumor targeting, nanosized supramolecular vehicles can be formed for in vitro and in vivo siRNA-Bcl2 delivery toward efficient gene therapy [43].

The host–guest interactions between β-CD with simple adamantane derivatives carrying bio-conjugatable functionalities (–OH, –NH2, –COOH, etc.) at the small molecular level may in part mirror those at the macromolecular level in the drug delivery systems. Further exploitation of these interactions may also provide us insight into efficient drug delivery systems with desirable drug loading efficacy and material stability. It is however surprising to note that, though an extensive array of inclusion complexes of β-CD have been reported, there is only a paucity of X-ray single-crystal structure studies of adamantane encapsulated β-CD [39,44,45], and systematic structural characterization of host–guest assemblies based on β-CD and adamantane derivatives is absent.

We herein demonstrate that the hybridization of β-CD with simple bio-conjugatable adamantane derivatives, including 1-adamantanol (adm-1-OH), 2-adamantanol (adm-2-OH), adamantan-1-amine (adm-1-NH2), 1-adamantanecarboxylic acid (adm-1-COOH), 1,3-adamantanedicarboxylic acid (adm-1,3-diCOOH), an 2-[3-(carboxymethyl)-1-adamantyl]acetic acid (adm-1,3-diCH2COOH) (Chart 1), give rise to unanticipated adamantanamine-to-CD ratios ranging from 1:2 to 3:2 in the solid state, with diverse orientations of the functional groups to the β-CD host (while fully appreciating that the dimeric form of β-CD does not exist in some organic solvent, such as DMSO [46,47], and the number of guest species are not necessarily integrals, we use this datum format to show the possible location and orientation of the guest molecules). An array of six adamantane⊂CD hybrids are thus provided, comprising (adm-1-OH)2⊂CD2 (1, 2:2), (adm-2-OH)3⊂CD2 (2, 3:2), (adm-1-NH2)3⊂CD2 (3, 3:2), (adm-1-COOH)2⊂CD2 (4, 2:2), (adm-1,3-diCOOH)⊂CD2 (5, 1:2), and (adm-1,3-diCH2COOH)⊂CD2 (6, 1:2). In all these cases, β-CD crystallizes as a pair supported by face-to-face hydrogen bonding, between hydroxyl groups on C2 and C3 with their equivalents from adjacent glucopyranose units, giving rise to a truncated-cone-shaped cavity to accommodate adamantane derivatives to support one, two, or three adamantane-derivatives. We demonstrate that the size, geometry, and identity of functionalities, all contribute to the final structural outcome of these host–guest assemblies. This work may provide insight toward designing supramolecular delivery systems underpinned by CDs and adamantane derivatives.

Chart 1.

Chemical structures and cartoon illustration of β-CD and the adamantane derivatives.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. General

β-CD, 1-adamanol and 1-adamantanecarboxylic acid were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Shanghai, China), 1,3-adamantanedicarboxylic acid and 2-[3-(carboxymethyl)-1-adamantyl]acetic acid were purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry (Tokyo, Japan), 2-adamanol was purchased from Adama-Beta Reagent Company (Shanghai, China), adamantan-1-amine was obtained from Energy Chemical Industry Company (Shanghai, China). All of the other chemicals were obtained directly from commercial sources and used as received. The two-dimensional 1H-1H nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY) was recorded on a Bruker DRX-500 nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometer (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany), and chemical shifts (δ) referenced to the residual solvent peaks or internal standard TMS. The Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were measured on a Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS50 FT-IR spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Co., Waltham, MA, USA) as KBr disks (400–4000 cm−1). The TGA–DSC diagrams were performed on a TA DSC Q100 differential filtering calorimeter (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA) at the heating rate of 10 °C·min−1 under a nitrogen stream of 50 cm3·min−1.

2.2. Preparation of β-CD and Adamantane Inclusion Complexes

β-CD and an equivalent amount of adamantane derivatives were introduced to an EtOH–H2O mixture with different volume ratios (3:7 for 1; 2:8 for 2; 3:7 for 3; pure water for 4; 4:6 for 5; 4:6 for 6). The formed mixtures were stirred at 80 °C for 2–3 h and smoothly cooled to room temperature. The crystals of each inclusion complex were obtained after ca 8 h as colorless parallelogram platelet crystals, which are significantly different from those of the pristine β-CD (colorless square-platelet crystals). The crystals were filtered and dried in air for subsequent characterizations.

2.3. 1H-NMR and FT-IR Characterization Data for the Adamantane Inclusion Complexes

Characterization data for (adm-1-OH)2⊂CD2 (1):1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 5.72 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 7H), 5.66 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 7H), 4.82 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 7H), 4.45 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 7H), 4.28 (s, 1H), 3.69–3.55 (m, 28H), 3.35–3.28 (m, 14H), 2.04 (s, 3H), 1.58 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 6H), 1.54 (br, 6H). IR (KBr disk): 3411 (s), 2911 (m), 2850 (w), 1639 (w), 1454 (w), 1421 (w), 1381 (w), 1367 (w), 1337 (w), 1305 (w), 1246 (w), 1203 (w), 1158 (m), 1106 (m), 1084 (m), 1031 (s), 937 (w), 858 (w), 758 (w), 702 (w), 646 (w), 607 (w), 575 (w), 527 (w), 480 (w), 444 (w) cm–1.

Characterization data for (adm-2-OH)3⊂CD2 (2):1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 5.72 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 7H), 5.66 (s, 7H), 4.82 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 7H), 4.48 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 1H), 4.45 (s, 7H), 3.66–3.55 (m, 29H), 3.33–3.28 (m, 14H), 2.06 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 3H), 1.75–1.62 (m, 15H), 1.38 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 3H). IR (KBr disk): 3412 (s), 2902 (m), 2852 (w), 1639 (w), 1458 (w), 1421 (w), 1380 (w), 1367 (w), 1337 (w), 1306 (w), 1248 (w), 1208 (w), 1159 (m), 1105 (m), 1083 (m), 1058(s), 1031 (s), 939 (w), 858 (w), 760 (w), 701 (w), 601 (w), 578 (w), 530 (w), 479 (w), 445 (w) cm–1.

Characterization data for (adm-1-NH2)3⊂CD2 (3): 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 5.71 (s, 14H), 4.82 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 7H), 4.48 (s, 7H), 3.66–3.55 (m, 28H), 3.34–3.28 (m, 14H), 2.00 (s, 3H), 1.59–1.52 (dd, J1 = 21.5 Hz, J2 = 12.0 Hz, 6H), 1.50 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 6H). IR (KBr disk): 3381 (s), 2907 (m), 2849 (m), 1639 (w), 1452 (w), 1413 (w), 1366 (w), 1334 (w), 1303 (w), 1248 (w), 1202 (w), 1155 (m), 1105 (m), 1081 (m), 1030 (s), 1003 (s), 939 (w), 858 (w), 756 (w), 703 (w), 650 (w), 607 (w), 578 (w), 528 (w), 477 (w), 444 (w) cm–1.

Characterization data for (adm-1-COOH)2⊂CD2 (4): 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 11.92 (br, 1H), 5.72 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 7H), 5.67 (s, 7H), 4.82 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 7H), 4.44 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 7H), 3.68–3.56 (m, 28H), 3.33–3.28 (m, 14H), 1.97 (s, 3H), 1.79 (s, 6H), 1.66 (s, 6H). IR (KBr disk): 3381 (s), 2921 (s), 2953 (s), 1698 (m), 1644 (w), 1456 (w), 1414 (w), 1384 (w), 1371 (w), 1332 (w), 1300 (w), 1278 (w), 1245 (w), 1204 (w), 1155 (m), 1105 (m), 1080 (m), 1057 (s), 1030 (s), 1004 (s), 939 (m), 890 (w), 861 (w), 757 (w), 704 (w), 666 (w), 650 (w), 605 (w), 577 (w), 529 (w), 478 (w), 445 (w), 413 (w) cm–1.

Characterization data for (adm-1,3-diCOOH)⊂CD2 (5): 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 12.11 (br, 2H), 5.73 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 7H), 5.68 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 7H), 4.83 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 7H), 4.46 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 7H), 3.67–3.55 (m, 28H), 3.37–3.28 (m, 14H), 2.06 (s, 2H), 1.84 (s, 2H), 1.78–1.69 (dd, J1 = 30.5 Hz, J2 = 11.0 Hz, 8H), 1.61 (s, 2H). IR (KBr disk): 3414 (s), 2930 (s), 2857 (m), 1705 (m), 1643 (w), 1455 (w), 1415 (w), 1383 (w), 1373 (w), 1335 (w), 1299 (w), 1273 (w), 1247 (w), 1202 (w), 1157 (m), 1106 (m), 1080 (m), 1050 (s), 1029 (s), 1004 (s), 941 (m), 890 (w), 861 (w), 757 (w), 705 (w), 655 (w), 607 (w), 577 (w), 530 (w), 477 (w), 445 (w), 412 (w) cm–1.

Characterization data for (adm-1,3-diCH2COOH)⊂CD2 (6): 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 11.83 (br, 1H), 5.69 (br, 12H), 4.83 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 7H), 3.68–3.55 (m, 28H), 3.37–3.29 (m, 14H), 1.99 (s, 2H), 1.97 (s, 4H), 1.54–1.43 (m, 12H). IR (KBr disk): 3382 (s), 2907 (s), 2849 (m), 1701 (m), 1644 (w), 1448 (w), 1410 (w), 1366 (w), 1329 (w), 1295 (w), 1273 (w), 1247 (w), 1202 (w), 1158 (m), 1104 (m), 1081 (m), 1056 (s), 1031 (s), 1002 (s), 942 (m), 861 (w), 758 (w), 706 (w), 659 (w), 642 (w), 609 (w), 578 (w), 531 (w), 481 (w), 447 (w), 413 (w) cm–1.

2.4. X-ray Crystal Structure Determinations

Single crystals of 1 and 2 were analyzed on a Bruker D8 Venture diffractometer (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) using liquid Ga-Kα irradiation (λ = 1.34139 Å), while the crystal data for other inclusion complexes were respectively recorded on Rigaku R-AXIS-RAPID (3, 4, Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan), Agilent Xcalibur and Gemini (5, Agilent Technologies, Yarnton, UK), and Bruker Apex-II (6, Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) diffractometers with Mo-Kα (λ = 0.71073 Å) radiation. The appropriate absorption correction (multi-scan) was also applied [48,49,50]. All of the crystal structures were solved by direct methods and refined on F2 by full-matrix least-squares techniques with the SHELXTL-2016 program [50].

For 2, the occupancy factors for one adm-2-OH were fixed at 0.5 to obtain reasonable thermal factors. The other adm-2-OH lies on a special position of higher symmetry than the molecule can possess. It was then treated as a spatial disorder but applying PART –1 and PART 0 in the .ins file with the site occupation factors changed to 0.25 for the atoms. Similarly, for 3, the occupancy factors for the three adm-1-NH2 were fixed at 0.5 to obtain reasonable thermal factors. The other adm-1-NH2 lies in a special position of higher symmetry than the molecule can possess. It was then treated as a spatial disorder but applying PART –1 and PART 0 in the .ins file with the site occupation factors changed to 0.10 for the atoms. For 5, the encapsulated dicarboxylic acid displayed conformational disorder with their relative ratio of 0.49:0.51 refined for the disordered domains. For 1−6, the coordinates of the hydrogen atoms on the –OH groups were calculated by Calc-OH program in WinGX suite [51], their O–H distances were further restrained to O–H = 0.83 Å and thermal parameters constrained to Uiso(H) = 1.2 Ueq(O). For 1−5, a large amount of spatially delocalized electron density in the lattice was found which were ascribed to the presence of water solvates. The solvent contribution was then modeled using SQUEEZE in the Platon program suite [52]. Specifically for 6, a stable shape of adm-1,3-diCH2COOH cannot be modeled during the refinement probably due to the weak electron densities, and the adm-1,3-diCH2COOH guest is also treated as solvates and removed together with H2O using SQUEEZE (247e in total: 84e for adm-1,3-diCH2COOH and 163e for H2O) [53].

Crystallographic data have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC) as supplementary publication numbers 2053567–2053572. These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif or from the Supporting Information. A summary of the key crystallographic data are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Crystal data and refinement parameters for the 1–6.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formula Weight | 2574.41 | 2726.69 | 2723.73 | 2630.47 | 2494.20 | 2522.28 |

| Empirical formula | 2C42H70O35∙ 2C10H16O |

2C42H70O35∙ 3C10H16O |

2C42H70O35∙3C10 H17N |

2C42H70O35∙ 2C11H16O2 |

2C42H70O35∙ C12H16O4 |

2C42H70O35∙ C14H20O4 |

| Crystal system | triclinic | orthorhombic | orthorhombic | orthorhombic | triclinic | triclinic |

| Space group | P1 | C2221 | C2221 | C2221 | P1 | P1 |

| a (Å) | 15.3986(9) | 23.8095(5) | 19.2469(5) | 19.1225(4) | 15.2993(8) | 15.2868(3) |

| b (Å) | 15.4175(8) | 19.2806(4) | 23.9691(5) | 24.2639(6) | 15.4429(7) | 15.4435(3) |

| c (Å) | 17.9599(10) | 32.4542(9) | 32.5978(9) | 32.6433(8) | 18.0837(10) | 18.0918(4) |

| α (°) | 113.169(2) | 90 | 90 | 90.00 | 99.751(4) | 100.0500(10) |

| β (°) | 99.213(2) | 90 | 90 | 90.00 | 113.551(5) | 113.0330(10) |

| γ (°) | 103.219(2) | 90 | 90 | 90.00 | 102.813(4) | 102.4900(10) |

| V (Å3) | 3664.1(4) | 14,898.5(6) | 15,038.4(7) | 15,146.0(6) | 3656.6(4) | 3674.56(13) |

| Z | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| ρcalc (g cm–3) | 1.167 | 1.097 | 1.031 | 1.075 | 1.133 | 1.026 |

| F(000) | 1372 | 5235 | 4754 | 5212 | 1324 | 1204 |

| µ (cm–1) | 0.545 | 0.520 | 0.802 | 0.093 | 0.099 | 0.504 |

| Total reflections | 50,836 | 96,200 | 72,586 | 55,633 | 27,091 | 46,007 |

| Unique reflections | 26,218 | 14,176 | 13,298 | 13,052 | 21,115 | 27,008 |

| Observed reflections | 19,199 | 11,540 | 12,601 | 9831 | 16,593 | 25,912 |

| Rint | 0.0715 | 0.0782 | 0.0408 | 0.0361 | 0.0387 | 0.0400 |

| Variables | 1568 | 774 | 773 | 739 | 1676 | 1387 |

| R1 a | 0.1024 | 0.082400853 | 0.0801 | 0.0883 | 0.0758 | 0.0648 |

| wR2b | 0.2643 | 0.2371 | 0.2303 | 0.2630 | 0.2080 | 0.1891 |

| GOF c | 1.027 | 1.071 | 1.051 | 1.153 | 1.027 | 1.028 |

a R1 = Σ||Fo|− - |Fc||/Σ|Fo|, b wR2 = {Σ[ω(Fo2 - Fc2)2]/Σ[ω(Fo2)2]}1/2, and c GOF = {Σ[ω(Fo2 - Fc2)2]/(n - p)}1/2, where n is the number of reflections, and p the total number of parameters refined.

2.5. Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) Measurements

The ITC experiments were performed on a VP–ITC (MicroCal, Inc., Northampton, MA, USA) under atmospheric pressure and at 25.0 °C in 5% DMSO-water solution (pH 7). The β-CD and adamantane derivatives in 4 and 5 were completely dissolved, giving the stability constants (K) and the corresponding thermodynamic parameters. Specifically, a solution of β-CD in a 0.250 mL syringe was sequentially injected with stirring at 300 rpm into a solution of adamantane derivatives in the sample cell (1.423 mL volume). The concentrations of β-CD and adamantane derivatives were used as 0.1 and 1 mM, respectively. All of the thermodynamic parameters reported in this work were obtained by using the “one set of binding sites” model [54,55].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis and Spectroscopic Characterization

The inclusion complexes of (adm-1-OH)2⊂CD2 (1), (adm-2-OH)3⊂CD2 (2), (adm-1-NH2)3⊂CD2 (3), (adm-1-COOH)2⊂CD2 (4), (adm-1,3-diCOOH)⊂CD2 (5), and (adm-1,3-diCH2COOH)⊂CD2 (6) can be readily prepared by heating equivalent β-CD and respective guest molecules in EtOH/H2O mixed solvent at 80 °C. The successful formation of inclusion complexes can be readily distinguished from the change of crystal shape from the square-platelet of pristine β-CD to parallelogram-shaped crystals, regardless of the crystal systems in which these inclusion complexes crystallize. The observation of crystal shape change also suggests that the conversion yield of the inclusion complexes are high but incomplete.

As depicted in Figures S1–S12 (Supplementary Material), a comparison of the 1H-NMR spectra between the inclusion complexes of 1–6 with that of the free β-CD indicates the successful incorporation of the adamantane-based guest molecules [56]. 1H-NMR also suggested the adamantane-to-β-CD ratios of approximately 1:1 for all these complexes (Supplementary Figures S1–S6). The stoichiometric inconsistency between the 1H-NMR results and that described from the X-ray single-crystal analysis (elaborated below) can be manifold. The crystallization process usually gives host–guest complexes with a statistical mixture of the guest molecules. The host-to-guest ratio of one single crystal thus does not represent that in the bulk sample. Besides, for the characterization of inclusion species, X-ray diffraction itself can also create bias during the experiment due to its scattering by the hosts, leading to a weaker electron density of the guest than it ought to be. Thus, though we observed nearly homogenous single crystals of parallelogram shape, these single crystals are estimated to contain significantly fewer adamantane-based guests due to the insufficient encapsulation.

Notably, although the 1H-NMR suggests 1:1 host–guest ratio for all these inclusion complexes in DMSO solution, only limited chemical shifts were also observed as demonstrated (Supplementary Figures S1–S12 and Tables S1–S12). This point to the dissociation of the guest molecules in DMSO solutions [46,47], likely due to the competitive inclusion by the DMSO solvate that is dominant.

The two-dimensional 1H-1H nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY) also indicates that there are only some weak interactions between the β-CD host and the adamantane derivatives, further suggest very limited guest inclusion (Supplementary Figures S13–S18). Nevertheless, from Supplementary Figures S13–S18, it is evident that the correlations between H6/H3 of adamantane backbone and interior protons of β-CD (H5) exist.

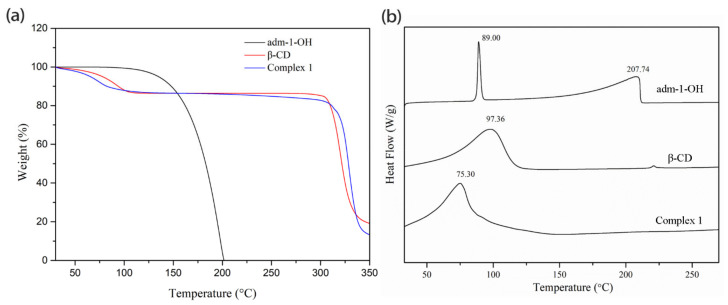

To investigate the thermal stabilities of these inclusion complexes, thermogravimetric and differential scanning calorimetry (TG-DSC) analyses were performed (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figures S19–S23). For 1–4, the disappearance of the melting peaks of the adamantane guests coincides with the peak alteration of β-CD, indicative of the successful insertion of the guest molecules inside the macrocyclic cavity [56,57,58]. For 5 and 6, the melting peak of the adamantane guests shifts to lower temperature and are also indicative of loss of the drug crystallinity and thus successful encapsulation. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA, Figure 1a and Figures S19–S23, Supplementary Material) for 1–6 indicated that these inclusion complexes dehydrated at around 100 °C, and plateaued until around 300 °C, upon which the decomposition of these species commences.

Figure 1.

(a) TG traces of adm-1-OH, β-CD and 1. (b) A comparison of the DSC-TGA curves of 1 and its subcomponents β-CD and adm-1-OH, showing the melting point alteration upon complex formation.

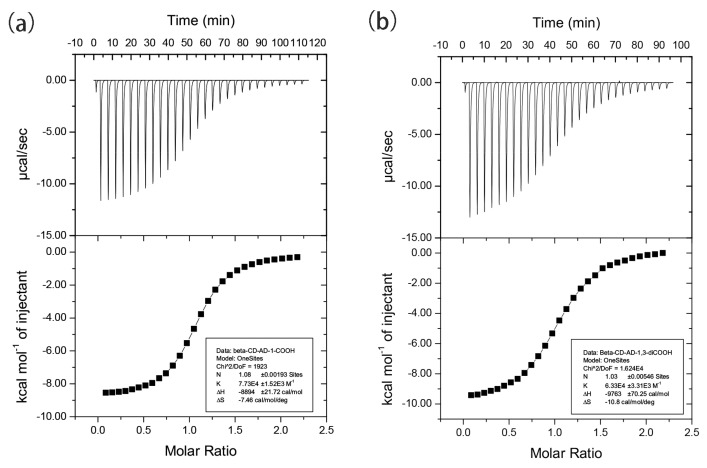

3.2. Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) Analysis of 4 and 5

To assess the thermodynamics of complexation, ITC was performed using a DMSO-water (5:95) solution at 25 °C. A one-step binding model was applied to generate an apparent binding constant (K) for the 1:1 inclusion complex for adm-1-COOH (4) and adm-1,3-diCOOH) (5) with β-CD, with a large ΔH value of −8894 cal·mol−1 and −9763 cal·mol−1, and relatively small ΔS value of −7.46 cal mol−1·°C−1 and −10.8 cal·mol−1·°C−1. Respective K values of 7.7 × 104 M−1 and 6.3 × 104 M−1 were accordingly derived (Figure 2). These results indicate that the interactions between 4 and 5 with β-CD tend to be enthalpically driven [59]. These K values observed herein are comparable to or higher than those inclusion complexes based on adamantanecarboxylate (deprotonated form of adm-1-COOH) with β-CD, γ-CD and α-CD (2 × 104 M−1, 3 × 103 M−1, and 1.4 × 102 M−1, respectively) [4,60]. The association constant of adm-1-COOH with β-CD varies at different pHs, giving K value of 3.0 × 105 M−1, 4.0 × 104 M−1, and 1.8 × 104 M−1 at pH 4.05, 7.2, and 8.5, respectively, were also reported [3]. Unfortunately, the satisfying ITC data acquisition for 1, 2, 3, and 6 fails due to the low water solubility of these guest molecules.

Figure 2.

(a) The ITC isotherm for the titration of β-CD (1.0 mM) into a solution of adm-1-COOH (0.1 mM), in 5% DMSO-water solution at 25 °C. (b) The ITC isotherm for the titration of β-CD (1.0 mM) into a solution of adm-1,3-diCOOH (0.1 mM), in 5% DMSO-water solution at 25 °C.

3.3. Single-Crystal Structure Analysis of 1–6

There are several typical space groups, such as P1, C2, P21, or C2221 [61,62,63], and different crystal packing modes, including channel (CH), screw channel (SC), intermediate (IM), and chessboard (CB) for β-CD-based inclusion compounds [64,65]. According to this classification, the β-CD-based dimers crystallize in the C2, P21, and C2221 space groups are always stacked in the CH, SC, and CB modes. In contrast, those crystallize in the P1 space group stack either in the CH mode if their cell dimensions are all about 15.5 Å, or in the IM mode if one of the cell dimensions is more than 17 Å and the two others being about 15.5 Å. Complexes 1–6 well-fit into these categories, as listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

A list of the packing modes of 1–6.

| Guest | Guest:β-CD | Space Group | Packing Mode | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | adm-1-OH | 2:2 | P1 | CH |

| 2 | adm-2-OH | 3:2 | C2221 | CB |

| 3 | adm-1-NH2 | 3:2 | C2221 | CB |

| 4 | adm-1-COOH | 2:2 | C2221 | CB |

| 5 | adm-1,3-diCOOH | 1:2 | P1 | CH |

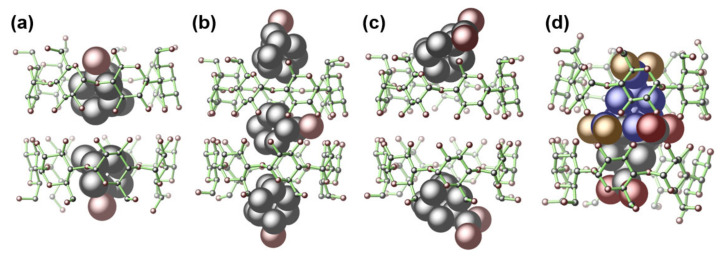

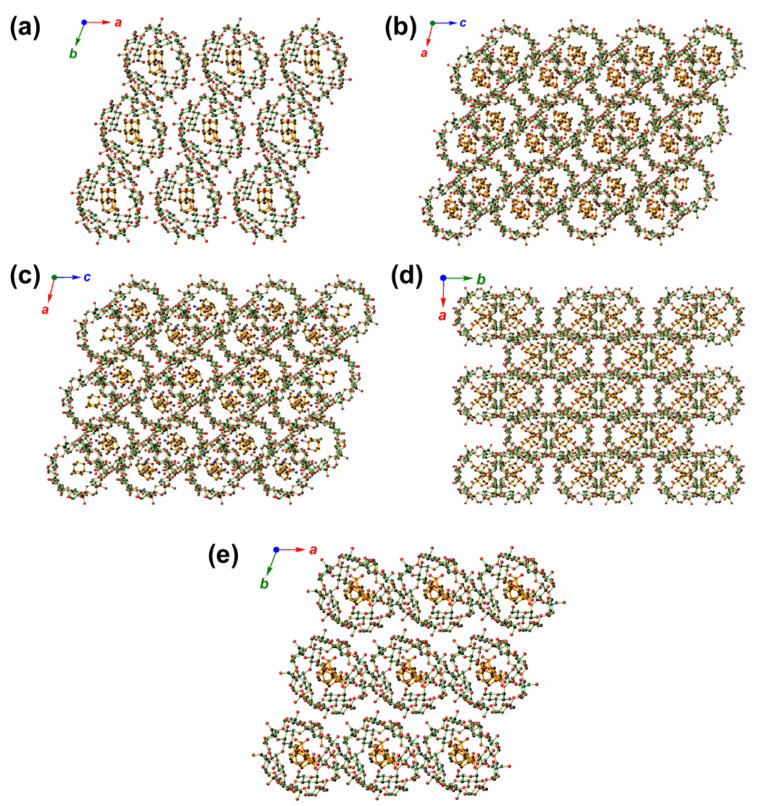

As depicted in Figure 3, in the structures of 1, 2, 4, and 5, the β-CD host exclusively forms a pair via the hydrogen bonding interactions between the –OH groups on C2/C3 with their equivalents (symmetry codes: x, y, z for 1; x, –y – 1, –z – 2 for 2; –x + 1, y, –z + 3/2 for 3; x + 1/2, y + 1/2, z for 4; x, y, z for 5; x, y, z for 6) to give a truncated-cone-like cavity. Such dimeric form dominates the host–guest complexes of β-CD with very limited exceptions [66,67,68,69,70]. As shown in Figure 3a, a pair of adm-1-OH in the cavity of 1 features a back-to-back conformation. Complexes 2, 3, and 4 share similar cell parameters (Table 1), guest inclusion patterns (Figure 3b,c and Supplementary Figure S24), as well as the crystal packing diagrams (Figure 4b–d). The β-CD pairs in 2/3 host three bulky adm-2-OH/adm-1-NH2 guests, of which two are associated with the β-CD pairs on the surface, while the third one is deeply buried inside of the cavity supported by the β-CD pair, and adopted two symmetry-related orientations (symmetry codes: x, –y – 1, –z – 2 for 2; –x + 1, y, –z + 3/2 for 3). Notably, all these guest molecules are ordered (except the sandwiched guest in 2 and 3) within the cavity, probably induced by the asymmetric micro-environment of the cavity [71,72,73].

Figure 3.

The X-ray crystal structures of 1 (a), 2 (b), 4 (c), and 5 (d) showing different adamantane-to-β-CD ratios and diverse guest orientations in the inclusion complexes. The guests are presented as a space-filling model. The hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. Color codes: O (brown-red), C (black). For 5, the two disordered parts of adm-1,3-diCOOH are represented by blue (for C) and brown (for O), as well as gray (for black) and brown-red (for O).

Figure 4.

The crystal packing diagrams of 1 ((a); along c direction), 2 ((b); along b direction), 3 ((c); along b direction), 4 ((d); along c direction), and 5 ((e); along c direction), showing similarities and differences in their packing patterns. Color codes: O (red), N (blue), and C (gray).

The slight size increase from adm-2-OH (in 2)/adm-1-NH2 (in 3) to adm-1-COOH [74,75] resulted in a 2:2 inclusion crystal of 4. With an identical β-CD-adamantane ratio to that of 1 with deeply buried adm-1-OH guests, the two adm-1-COOH guest in 4 are flanked on the two sides of the β-CD pair, leading to the generation of space with the potential to host additional guest with suitable size. It is notable that though 2, 3, and 4 crystallize in the same space group of C2221 and feature the CH mode, the packing diagrams of 4 exhibits a different fashion as compared to those of 2 and 3 (Figure 4b–d, and Supplementary Materials, Figure S25).

From Table 1, it is notable that 1, 5, and 6 share nearly identical cell parameters and their molecular arrangement within the cells are also expected to resemble each other. Though with different β-CD-to-adamantane ratios, 1 and 5 share similar structural features in that all the adamantane derivatives are deeply buried inside of the cavity formed by β-CD (Figure 3a,d), and their structure packings (CH type) also resemble each other (Figure 4a,e). Compared to 1, the β-CD pair in 5 is only able to host one adm-1,3-diCOOH molecule due to the bulky size of the latter, the disordered adm-1,3-diCOOH guest nevertheless exhibits preferential back-to-back orientations in a nearly 1:1 ratio (0.49:0.51).

4. Conclusions

The guest inclusion behaviors of β-CD toward a series of simple adamantane derivatives carrying –OH, –NH2, –COOH, and –CH2COOH functionalities have been scrutinized. Our work suggests that the identity of functional groups (adm-1-OH in 1 versus adm-1-NH2 in 3), geometry (adm-1-OH in 1 versus adm-2-OH in 2), and size (adm-1,3-diCOOH in 5 and adm-1,3-diCH2COOH in 6) collectively define the adamantane-to-β-CD ratios and the spatial locations of these guest molecules. Though these limited structural studies are far away from serving as an accurate predictor for the structural outcome in other scenarios, the structural features described herein may offer us some insight into the design of cyclodextrin-based host–guest assemblies; for example, to achieve the regioselectivity in the post-synthetic functionalization of the encapsulated adamantane derivatives, via the stealth of one functionality, while exposing the other for further modification. Given the broad and continuous interest in using β-CD and adamantane hybrid for designing efficient drug delivery systems for biomedical applications, and that –OH, –NH2, and –COOH are ideal functionalities to perform bio-conjugate chemistry under mild conditions, our work herein may provide insight and cautions for those working on supramolecular delivery systems utilizing cyclodextrin and adamantane hybrids.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jiyong Liu, Linshen Chen, and Lin He from the Analysis Center of the Department of Chemistry, Zhejiang University, for their technical assistance.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online: Figures S1–S12: The 1H-NMR spectra for 1–6; Figures S13–S18: 2D NOESY spectra for 1–6; Figures S19–S14: TG traces and DSC curves for 2–6. Figure S24: The X-ray crystal structure of 3. Figure S25: The crystal packing diagram of 6; Tables S1–S12: The summarized data and remark of chemical shifts of β-cyclodextrin or adamantane derivatives before/after forming complexes 1–6.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.H. and G.T.; methodology, J.-W.W. and K.-X.Y.; investigation, J.-W.W., K.-X.Y., X.-Y.J., and H.B.; data curation, X.H., K.-X.Y., W.-H.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-W.W. and K.-X.Y.; writing—review and editing, G.T., X.H., and W.-H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant numbers 51873185, 21871203. This research did not receive any other specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

CCDC 2053567–2053572 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Crini G. Review: A History of Cyclodextrins. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:10940–10975. doi: 10.1021/cr500081p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saenger W., Jacob J., Gessler K., Steiner T., Hoffmann D., Sanbe H., Koizumi K., Smith S.M., Takaha T. Structures of the common cyclodextrins and their larger analoguesbeyond the doughnut. Chem. Rev. 1998;98:1787–1802. doi: 10.1021/cr9700181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eftink M.R., Andy M.L., Bystrom K., Perlmutter H.D., Kristol D.S. Cyclodextrin inclusion complexes: Studies of the variation in the size of alicyclic guests. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:6765–6772. doi: 10.1021/ja00199a041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cromwell W.C., Bystrom K., Eftink M.R. Cyclodextrin-adamantanecarboxylate inclusion complexes: Studies of the variation in cavity size. J. Phys. Chem. 1985;89:326–332. doi: 10.1021/j100248a029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krois D., Brinker U.H. Induced Circular Dichroism and UV−Vis Absorption Spectroscopy of Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complexes: Structural Elucidation of Supramolecular Azi-adamantane (Spiro[adamantane-2,3‘-diazirine]) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:11627–11632. doi: 10.1021/ja982299f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gelb R.I., Schwartz L.M. Complexation of adamantane-ammonium substrates by beta-cyclodextrin and itsO-methylated derivatives. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem. 1989;7:537–543. doi: 10.1007/BF01080464. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dasgupta S., Wu J. Formation of [2]rotaxanes by encircling [20], [21] and [22]crown ethers onto the dibenzylammonium dumbbell. Chem. Sci. 2011;3:425–432. doi: 10.1039/C1SC00613D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park H.J., Suh M.P. Enhanced isosteric heat of H2 adsorption by inclusion of crown ethers in a porous metal–organic framework. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:3400–3402. doi: 10.1039/c2cc17005a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao M., Liang Z., Zhang B., Wang Q., Lee J., Li F., Wang Q., Ma D., Ling D. Supramolecular Container-Mediated Surface Engineering Approach for Regulating the Biological Targeting Effect of Nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2020;20:7941–7947. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c02701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frank N., Dallmann A., Braun-Cula B., Herwig C., Limberg C. Mercaptothiacalixarenes steer 24 copper(I) centers to form a hollow-sphere structure featuring Cu2S2 motifs with exceptionally short Cu⋅⋅⋅Cu distances. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:6735–6739. doi: 10.1002/anie.201915882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim H.J., Lee M.H., Mutihac L., Vicens J., Kim J.S. Host–guest sensing by calixarenes on the surfaces. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:1173–1190. doi: 10.1039/C1CS15169J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dai F.-R., Wang Z. Modular Assembly of Metal–Organic Supercontainers Incorporating Sulfonylcalixarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:8002–8005. doi: 10.1021/ja300095j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xian S., Webber M.J. Temperature-responsive supramolecular hydrogels. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2020;8:9197–9211. doi: 10.1039/D0TB01814G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu W., Feng H., Zhao W., Huang C., Redshaw C., Tao Z., Xiao X. Amino acid recognition by a fluorescent chemosensor based on cucurbit[8]uril and acridine hydrochloride. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2020;1135:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2020.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu H., Li Q., Gao Z., Wang H., Shi B., Wu Y., Shangguan L., Hong X., Wang F., Huang F. Pillararene Host–Guest Complexation Induced Chirality Amplification: A New Way to Detect Cryptochiral Compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:10868–10872. doi: 10.1002/anie.202001680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joseph R., Naugolny A., Feldman M., Herzog I.M., Fridman M., Cohen Y. Cationic Pillararenes Potently Inhibit Biofilm Formation without Affecting Bacterial Growth and Viability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:754–757. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b11834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou Y., Jie K., Zhao R., Li E., Huang F. Highly Selective Removal of Trace Isomers by Nonporous Adaptive Pillararene Crystals for Chlorobutane Purification. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:6957–6961. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c02684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou J., Yu G., Huang F. Supramolecular chemotherapy based on host–guest molecular recognition: A novel strategy in the battle against cancer with a bright future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017;46:7021–7053. doi: 10.1039/C6CS00898D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y., Liu Y., Liu Y. Cyclodextrin-Based Multistimuli-Responsive Supramolecular Assemblies and Their Biological Functions. Adv. Mater. 2020;32:e1806158. doi: 10.1002/adma.201806158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tian B., Hua S., Liu J. Cyclodextrin-based delivery systems for chemotherapeutic anticancer drugs: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020;232:115805. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo J., Li D., Tao H., Li G., Liu R., Dou Y., Jin T., Li L., Huang J., Hu H., et al. Cyclodextrin-Derived Intrinsically Bioactive Nanoparticles for Treatment of Acute and Chronic Inflammatory Diseases. Adv. Mater. 2019;31:e1904607. doi: 10.1002/adma.201904607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mavridis I.M., Yannakopoulou K. Porphyrinoid–Cyclodextrin Assemblies in Biomedical Research: An Update. J. Med. Chem. 2019;63:3391–3424. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mejia-Ariza R., Graña-Suárez L., Verboom W., Huskens J. Cyclodextrin-based supramolecular nanoparticles for biomedical applications. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2017;5:36–52. doi: 10.1039/C6TB02776H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van de Manakker F., Vermonden T., van Nostrum C.F., Hennink W.E. Cyclodextrin-Based Polymeric Materials: Synthesis, Properties, and Pharmaceutical/Biomedical Applications. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:3157–3175. doi: 10.1021/bm901065f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Numanoğlu U., Şen T., Tarimci N., Kartal M., Koo O.M.Y., Önyüksel H. Use of cyclodextrins as a cosmetic delivery system for fragrance materials: Linalool and benzyl acetate. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2007;8:34–42. doi: 10.1208/pt0804085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sikder T., Rahman M., Jakariya M., Hosokawa T., Kurasaki M., Saito T. Remediation of water pollution with native cyclodextrins and modified cyclodextrins: A comparative overview and perspectives. Chem. Eng. J. 2019;355:920–941. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2018.08.218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alsbaiee A., Smith B.J., Xiao L., Ling Y., Helbling D.E., Dichtel W.R. Rapid removal of organic micropollutants from water by a porous β-cyclodextrin polymer. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016;529:190–194. doi: 10.1038/nature16185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiao L., Ling Y., Alsbaiee A., Li C., Helbling D.E., Dichtel W.R. β-Cyclodextrin Polymer Network Sequesters Perfluorooctanoic Acid at Environmentally Relevant Concentrations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:7689–7692. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b02381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santana I., Wu H., Hu P., Giraldo J.P. Targeted delivery of nanomaterials with chemical cargoes in plants enabled by a biorecognition motif. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15731-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Connors K.A. The Stability of Cyclodextrin Complexes in Solution. Chem. Rev. 1997;97:1325–1358. doi: 10.1021/cr960371r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phan C., Zheng Z., Wang J., Wang Q., Hu X., Tang G., Bai H. Enhanced antitumour effect for hepatocellular carcinoma in the advanced stage using a cyclodextrin-sorafenib-chaperoned inclusion complex. Biomater. Sci. 2019;7:4758–4768. doi: 10.1039/C9BM01190K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y.-M., Zhang N.-Y., Xiao K., Yu Q., Liu Y. Photo-controlled reversible microtubule assembly mediated by paclitax-el-modified cyclodextrin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:8649–8653. doi: 10.1002/anie.201804620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stricker L., Fritz E.-C., Peterlechner M., Doltsinis N.L., Ravoo B.J. Arylazopyrazoles as Light-Responsive Molecular Switches in Cyclodextrin-Based Supramolecular Systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:4547–4554. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b00484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu Q.-D., Tang G.-P., Chu P.K. Cyclodextrin-Based Host–Guest Supramolecular Nanoparticles for Delivery: From Design to Applications. Accounts Chem. Res. 2014;47:2017–2025. doi: 10.1021/ar500055s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen H., Liu X., Dou Y., He B., Liu L., Wei Z., Li J., Wang C., Mao C., Zhang J., et al. A pH-responsive cyclodextrin-based hybrid nanosystem as a nonviral vector for gene delivery. Biomater. 2013;34:4159–4172. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang J., Ma P.X. Cyclodextrin-based supramolecular systems for drug delivery: Recent progress and future perspective. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013;65:1215–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liao R., Lv P., Wang Q., Zheng J., Feng B., Yang B. Cyclodextrin-based biological stimuli-responsive carriers for smart and precision medicine. Biomater. Sci. 2017;5:1736–1745. doi: 10.1039/C7BM00443E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vícha R., Rouchal M., Kozubková Z., Kuřitka I., Marek R., Branná P., Čmelík R. Novel adamantane-bearing anilines and properties of their supramolecular complexes with β-cyclodextrin. Supramol. Chem. 2011;23:663–677. doi: 10.1080/10610278.2011.593628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Enright G.D., Udachin K.A., Ripmeester J.A. Complex packing motifs templated by a pseudo-spherical guest: The structure of β-cyclodextrin–adamantaneinclusion compounds. CrystEngComm. 2010;12:1450–1453. doi: 10.1039/B920581K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu X., Sun M., Li Y., Tang G. Evaluation of molecular chaperone drug function: Regorafenib and β-cyclodextrins. Colloids Surf. B. 2017;153:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu Q., Wang K., Sun X., Li Y., Fu Q., Liang T., Tang G. A redox-sensitive, oligopeptide-guided, self-assembling, and effi-ciency-enhanced (ROSE) system for functional delivery of microRNA therapeutics for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomaterials. 2016;104:192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hu Q.-D., Fan H., Ping Y., Liang W.-Q., Tang G.-P., Li J. Cationic supramolecular nanoparticles for co-delivery of gene and anticancer drug. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:5572–5574. doi: 10.1039/C1CC10721F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wen Y., Bai H., Zhu J., Song X., Tang G., Li J. A supramolecular platform for controlling and optimizing molecular architectures of siRNA targeted delivery vehicles. Sci. Adv. 2020;6:eabc2148. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abc2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harata K. Crystallographic analysis of the thermal motion of the inclusion complex of cyclomaltoheptaose (β-cyclodextrin) with hexamethylenetetramine. Carbohydr. Res. 2003;338:353–359. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6215(02)00444-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rüdiger V., Eliseev A., Simova S., Schneider H.-J., Blandamer M.J., Cullis P.M., Meyer A.J. Conformational, calorimetric and NMR spectroscopic studies on inclusion complexes of cyclodextrins with substituted phenyl and adamantane derivatives. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2. 1996:2119–2123. doi: 10.1039/P29960002119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schneider H.-J., Hacket F., Rüdiger V., Ikeda H. NMR Studies of Cyclodextrins and Cyclodextrin Complexes. Chem. Rev. 1998;98:1755–1786. doi: 10.1021/cr970019t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ejchart A., Koźmiński W. Cyclodextrins and Their Complexes. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co; Weinheim, Germany: 2006. NMR of Cyclodextrins and Their Complexes; pp. 231–254. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Higashi, T. ABSCOR. Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan. ABSCOR. Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan 1995

- 49.Bruker. APEX2, SAINT and SADABS. Bruker ACS Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA. 2014

- 50.Sheldrick G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Cryst. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2015;71:3–8. doi: 10.1107/S2053229614024218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Farrugia L.J. WinGXandORTEP for Windows: An update. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2012;45:849–854. doi: 10.1107/S0021889812029111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spek A.L. Single-crystal structure validation with the programPLATON. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2003;36:7–13. doi: 10.1107/S0021889802022112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spek A.L. PLATON SQUEEZE: A tool for the calculation of the disordered solvent contribution to the calculated structure factors. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2015;71:9–18. doi: 10.1107/S2053229614024929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Y.-M., Xu X., Yu Q., Liu Y.-H., Zhang Y.-H., Chen L.-X., Liu Y. Reversing the Cytotoxicity of Bile Acids by Supramolecular Encapsulation. J. Med. Chem. 2017;60:3266–3274. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bouchemal K., Mazzaferro S. How to conduct and interpret ITC experiments accurately for cyclodextrin–guest interactions. Drug Discov. Today. 2012;17:623–629. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mura P. Analytical techniques for characterization of cyclodextrin complexes in aqueous solution: A review. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2014;101:238–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2014.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mura P. Analytical techniques for characterization of cyclodextrin complexes in the solid state: A review. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2015;113:226–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2015.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mura P., Maestrelli F., Cirri M., Furlanetto S., Pinzauti S. Differential scanning calorimetry as an analytical tool in the study of drug-cyclodextrin interactions. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2003;73:635–646. doi: 10.1023/A:1025494500283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Loftsson T., Brewster M.E. Pharmaceutical Applications of Cyclodextrins. 1. Drug Solubilization and Stabilization. J. Pharm. Sci. 1996;85:1017–1025. doi: 10.1021/js950534b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Harries D., Rau A.D.C., Parsegian V.A. Solutes Probe Hydration in Specific Association of Cyclodextrin and Adamantane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2184–2190. doi: 10.1021/ja045541t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brett T.J., Alexander J.M., Stezowski J.J. Chemical insight from crystallographic disorder-structural studies of supramolecular photochemical systems. Part 2. The β-cyclodextrin–4,7-dimethylcoumarin inclusion complex: A new β-cyclodextrin dimer packing type, unanticipated photoproduct formation, and an examination of guest influence on β-CD dimer packing. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2. 2000;2:1095–1103. doi: 10.1039/a906041c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Harata K. Cyclodextrins and their complexes. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co; Weinheim, Germany: 2006. Crystallographic study of cyclodextrins and their inclusion complexes; pp. 147–198. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Caira M.R. Structural Aspects of Crystalline Derivatized Cyclodextrins and Their Inclusion Complexes. Curr. Org. Chem. 2011;15:815–830. doi: 10.2174/138527211794518862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Caira M.R. Polymorphism and isostructurality of cyclodextrins and their inclusion complexes. Acta Crystallogr. A. 2006;62:s76. doi: 10.1107/S0108767306098485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mentzafos D., Mavridis I.M., Le Bas G., Tsoucaris G. Structure of the 4-tert-butylbenzyl alcohol–β-cyclodextrin complex. Common features in the geometry of β-cyclodextrin dimeric complexes. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Sci. Cryst. Eng. Mater. 1991;47:746–757. doi: 10.1107/S010876819100366X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lindner K., Saenger W. β-Cyclodextrin dodecahydrate: Crowding of water molecules within a hydrophobic cavity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1978;17:694–695. doi: 10.1002/anie.197806941. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ohira A., Sakata M., Taniguchi I., Hirayama C., Kunitake M. Comparison of nanotube structures constructed from α-, β-, and γ-cyclodextrins by potential-controlled adsorption. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:5057–5065. doi: 10.1021/ja021351b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yee E.M., Hook J.M., Bhadbhade M.M., Vittorio O., Kuchel R.P., Brandl M.B., Tilley R.D., Black D.S., Kumar N., Eugene Y.M. Preparation, characterization and in vitro biological evaluation of (1:2) phenoxodiol-β-cyclodextrin complex. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017;165:444–454. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.02.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li G., McGown L.B. Molecular nanotube aggregates of β- and γ-cyclodextrins linked by diphenylhexatrienes. Science. 1994;264:249–251. doi: 10.1126/science.264.5156.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aree T. Inclusion complex of β-cyclodextrin with coffee chlorogenic acid: New insights from a combined crystallographic and theoretical study. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2019;75:15–21. doi: 10.1107/S2053229618016741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen J., Chao M.-Y., Liu Y., Xu B.-W., Zhang W.-H., Young D.J. An N,N′-diethylformamide solvent-induced conversion cascade within a metal–organic framework single crystal. Chem. Commun. 2020;56:5877–5880. doi: 10.1039/D0CC02420A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chao M.-Y., Chen J., Hao Z.-M., Tang X.-Y., Ding L., Zhang W.-H., Young D.J., Lang J.-P. A Single-Crystal to Single-Crystal Conversion Scheme for a Two-Dimensional Metal–Organic Framework Bearing Linear Cd3 Secondary Building Units. Cryst. Growth Des. 2019;19:724–729. doi: 10.1021/acs.cgd.8b01311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang Z.-X., Ding N.-N., Zhang W.-H., Chen J.-X., Young D.J., Hor T.S.A. Stitching 2D Polymeric Layers into Flexible Interpenetrated Metal-Organic Frameworks within Single Crystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:4628–4632. doi: 10.1002/anie.201311131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hamilton J.A., Steinrauf L.K., Van Etten R.L. Interrelated space groups observed for complexes of cycloheptaamylose with small organic molecules. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Crystallogr. Cryst. Chem. 1968;24:1560–1562. doi: 10.1107/S0567740868004632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hamilton J.A., Sabesan M.N. Structure of a complex of cycloheptaamylose with 1-adamantanecarboxylic acid. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Crystallogr. Cryst. Chem. 1982;38:3063–3069. doi: 10.1107/S0567740882010838. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

CCDC 2053567–2053572 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033.