Abstract

Solitary extramedullary plasmacytomas of the head and neck region are rare entities. Very few have been described in the parotid gland. They can clinically and radiologically mimic the rather common benign tumors of the parotid gland (pleomorphic adenoma and Wharthin's tumor), and subsequently the need careful consideration by the involving surgeon and pathologist is needed for a proper diagnosis. In the present study, a case of solitary extramedullary plasmacytoma in the left parotid gland of a 55-year-old patient with mixed connective tissue disease is reported, along with the relevant clinical, imaging, operative, and histopathological findings. Postoperative hematological investigation to confirm the singularity of the lesion was performed. Complementary treatment with radiotherapy was followed. Disease-free, 1 year follow up is also presented.

Keywords: Extramedullary, mixed connective tissue disease, parotid gland, plasmacytoma, radiotherapy

INTRODUCTION

Plasmacytomas are malignant tumors that consist of abnormal plasma cells of monoclonal origin. They may be solitary or diffuse, the second corresponding to multiple myeloma. Solitary plasmacytomas may be found as bone defects or uncommonly extramedullary. Solitary extramedullary plasmacytomas (SEP) have a frequency of <5% of all plasmacytomas, affecting mainly the upper respiratory tract. Rare locations of appearance are the gastrointestinal tract, skin, lymph nodes, adrenal glands.[1,2,3] The mean age of appearance is 55 years with a twice as high frequency in males.[4]

SEP of the parotid gland is a rare entity, with only a few described in the literature.[5] The first case of parotid plasmacytoma was described by Vainio-Mattila in 1960.[6] Since parotid tumors are rarely biopsied before excision, especially when there are clinical and radiological signs of nonmalignancy, SEP are diagnosed after the excision and during the histopathological examination.

The aim of this study is to report a case of solitary extramedullary plasmacytoma in a 50-year-old female patient and its diagnostic and therapeutic course.

CASE REPORT

A 50-year-old female patient was referred to the outpatient clinic of the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department in March 2019 with a slightly painful palpable mass in the left parotid area. Her symptoms began approximately a month earlier with slow enlargement of this mass and periods of pain in the area. Concerning the medical history, the patient has mixed connective tissue disease and receives hydroxychloroquine twice daily. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed, revealing a cystic formation with solid elements 2.3 cm × 1.2 cm in the left parotid tail and a high signal in T2 and low T1 sequence [Figure 1]. A possible diagnosis of a benign pleomorphic adenoma was set and surgery was scheduled. A subtotal parotidectomy was performed [Figure 2] maintaining the facial nerve intact by using a nerve stimulator. The postoperative course was uneventful. The excised specimen was sent for histopathological examination.

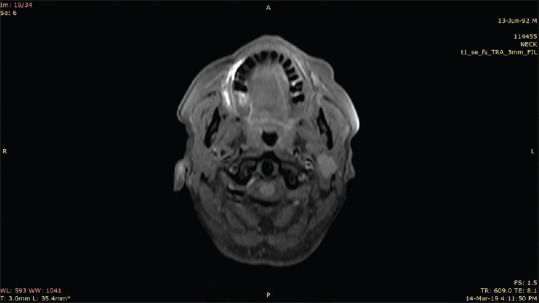

Figure 1.

A low signal tumor is distinguished in the left parotid gland (magnetic resonance imaging, T1 sequence)

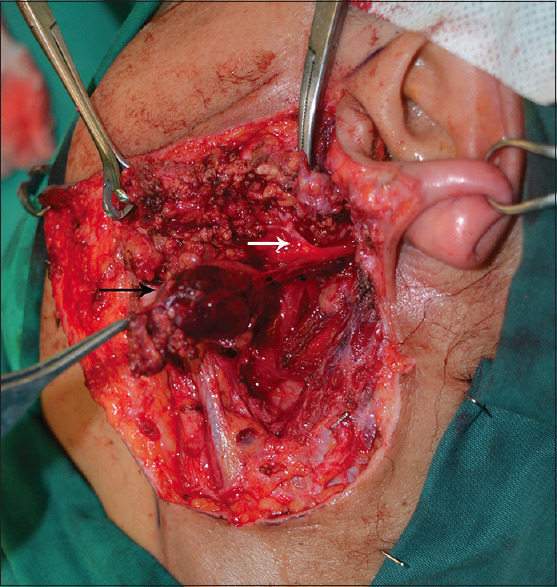

Figure 2.

Intraoperative photograph of the tumor (black arrow). The facial nerve was preserved (white arrow)

The histopathological examination revealed a neoplasm consisting of monoclonal plasma cells expressing kappa immunoglobulin light chains. The cells are medium sized, uniform, with eosinophilic cytoplasm and eccentric nuclei. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed diffuse proliferation of plasma cells with minimal pleomorphism (small number of large nuclei and bi-or multinucleated cells). Immunohistochemistry revealed the following: CD138+, CD38+, CD10+, MUM-1+, CD56-/+, CK8/18-, CK19-, CK7-, CK5/6-, p63-, SMA-, Calponin-, GFAP-, S100-, Cycin-D1-, CD20-, CD30-, CD3-, Ki-67 7%–8%. Figure 3 summarizes the prominent findings of the histopathology report. The diagnosis of an extramedullary plasmacytoma of the parotid gland was set and the patient was referred to the Hematology Department to assess whether this plasmacytoma was solitary or a manifestation of a systemic disease (multiple myeloma) and receive the appropriate treatment.

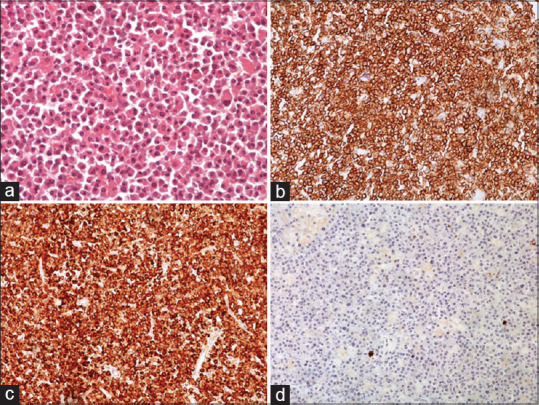

Figure 3.

Histopathology. (a). Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed diffuse proliferation of plasma cells with minimal pleomorphism, small number of large nulei and bi- or multinucleated cells. (H&E, ×200) (b). CD38+ (c). Immunohistochemical staining revealed kappa immunoglobulin light chains restriction. (d). Negative staining for lambda immunoglobulin light chains

Further investigation was performed by the Hematology Department. A bone marrow biopsy did not reveal infiltration by monoclonal plasma cells. Serum protein electrophoresis did not reveal a monoclonal protein (albumin 58,5%, alpha1 4,3%, alpha2 8%, beta1 6,8%, beta2 5,4%, gamma 17%). A 24 h total urine protein was negative for light chains. Serum quantitative immunoglobins and beta-2 microglobulin were at normal levels (beta-2 microglobulin 2,28 mg/dl, IgA 300 mg/dl, IgG 1270 mg/dl, IgM 130 mg/dl). Total skeleton X-rays revealed no osteolytic lesions. A positron emission tomography (PET) computed tomography scan was performed to exclude distant foci of the disease which indeed did not show any other affected area or diffuse disease. Considering these, a definitive diagnosis of a solitary extramedullary plasmacytoma was set.

The patient was scheduled for radiotherapy in the left parotid area. She received a total of 4000cGy in 20 fractions of 200cGy with good tolerance. One month later, post-radiation neuropathic pain appeared in the left parotid area and appropriate treatment was prescribed. The patient remains disease-free and is on regular follow-up by the Hematology Department as well as our Department. One year afterward, an MRI was performed with no signs of local disease [Figure 4].

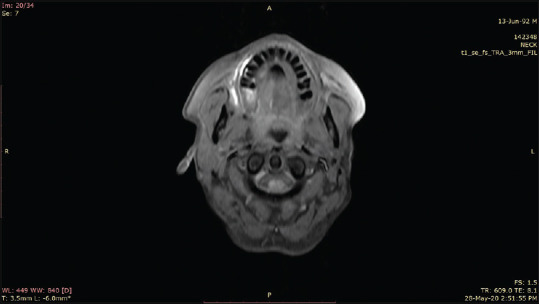

Figure 4.

Postoperative magnetic resonance imaging, one year after the parotidectomy. No signs of disease can be described (T1 sequence)

DISCUSSION

Solitary plasmacytoma is a type of localized malignant tumor consisting of monoclonal B-cells with the capsular formation or local infiltration of the tissues. The literature describes the incidence of this malignancy as of 3/100.000 population. Solitary plasmacytomas may occur in bone or soft tissue, with the latter being less common.[7]

The most important step after the initial histopathologic diagnosis of the extramedullary plasmacytoma is excluding multiple myeloma. This requires a bone marrow biopsy, serum protein electrophoresis, a 24 h urine collection for protein calculation, serum quantitative immunoglobins, and skeleton X-rays. If any of these appear with a pathological value, then a diagnosis of systemic disease is more likely. PET scan is a favorable option to exclude the possibility of other plasmacytoma affected areas.[8]

The cyclin-D1 expression is known to have an unfavorable prognosis in patients with plasmacytomas, but in our case, this marker was negative.[9]

Radiotherapy is a treatment of choice for nonexcisable SEP of the oropharynx, which is the most common area where a SEP can develop. Guidelines of the UK Myeloma Forum suggest 40 Gy in 20 fractions or 50 Gy in 25, depending on the size of the plasmacytoma. There are even suggestions for higher dosages for better local control of the disease and higher survival rates.[10] Radiotherapy after excision of the SEP in the parotid gland is not standard practice, yet, some authors recommend it to prevent local relapse. From the published cases in the literature, almost half of the cases with SEP in the parotid gland received radiotherapy after excision, and 3 of them received only radiotherapy without surgery first.[5] It is not known whether all these cases have a long-term follow-up to record the possibility of a relapse. In this case, postsurgical radiotherapy was decided. The patient received 40 Gy in 20 fractions, as the aforementioned guidelines suggest. Xerostomia is a rather common postradiotherapy outcome and it should always be considered in the follow-up visits.

Since there is evidence that SEP may locally relapse, even after postoperative radiotherapy, a meticulous follow-up is needed for a prolonged period. 20%–30% of the patients initially diagnosed with SEP will eventually develop multiple myeloma and almost half of them will develop bone plasmacytomas, and this is important for the involved clinicians to consider.[11] Compared to bone plasmacytoma, it has a better prognosis, since it is known that 70% of patients with bone plasmacytomas will eventually develop multiple myeloma.[7]

Another theory that supports SEPs' better prognosis and states that they are clinically and pathologically different from bone plasmacytomas is based on the fact that in SEP the plasma cells are dominant with centrocyte-like and monocytoid B cells in smaller amounts. Due to this pathological image, they could be characterized similarly to marginal zone cell lymphomas, thus, differentiating from bone plasmacytomas and its diffuse variant, multiple myelomas.[12]

There is a case report of the rapid progression of a SEP to a nonHodgkin B-cell lymphoma after surgical excision and radiotherapy, in a patient with CREST syndrome. The authors state that the combination of a SEP with a systemic connective tissue disorder is probably an indication of a generalized immunological defect.[9] In our patient, the underlying medical condition of mixed connective tissue disease suggests the same hypothesis. As of the authors' knowledge, this is the second reported case of SEP on a patient with a connective tissue disease.

In conclusion, SEP of the parotid gland is a rare entity, and since it can clinically and radiologically mimic the rather common benign tumors of the parotid gland (pleomorphic adenoma and Wharthin's tumor), careful consideration by the involving surgeon and pathologist is needed for a proper diagnosis. Patients' referral to a hematologist for the necessary workup to exclude systemic disease, and plan the appropriate treatment and follow-up is fundamental.

Informed consent

Signed informed consent was waived by the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery.

Declaration statement

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient has given her consent for her images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that name and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Swerdlow SH, E Campo NL, Harris ES, Jaffe SA, Pileri H, Stein, et al. 4th Edition. Vol. 2. France: IARC Publications; 2012. “IARC Publications Website - WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues.” WHO/IARC Classification of Tumours. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scholl P, Jafek BW. Extramedullary plasmacytoma of the parotid gland. Ear Nose Throat J. 1986;65:564–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Townend PJ, Kraus G, Coyle L, Nevell D, Engelsman A, Sidhu SB. Bilateral extramedullary adrenal plasmacytoma: Case report and review of the literature. Int J Endocr Oncol. 2017;4:67–73. doi: 10.2217/ije-2016-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bachar G, Goldstein D, Brown D, Tsang R, Lockwood G, Perez-Ordonez B, et al. Solitary extramedullary plasmacytoma of the head and neck--long-term outcome analysis of 68 cases. Head Neck. 2008;30:1012–9. doi: 10.1002/hed.20821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzalez-Perez LM, Infante-Cossio P, Borrero-Martin JJ. Primary extraosseous plasmacytoma of the parotid gland: A case report and literature review. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;7:751–4. doi: 10.3892/mco.2017.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vainio-Mattila J. Plasmacytoma of the parotid gland. Arch Otolaryngol. 1965;82:635–7. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1965.00760010637016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodríguez-Caballero B, Sanchez-Santolino S, García-Montesinos-Perea B, Garcia-Reija MF, Gómez-Román J, Saiz-Bustillo R. Mandibular solitary plasmocytoma of the jaw: A case report. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2011;16:e647–50. doi: 10.4317/medoral.16952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alabed YZ, Rakheja R, Laufer J. Solitary extramedullary plasmacytoma of the parotid gland imaged with 18F-FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2014;39:549–50. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3182a75c95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gouveris H, Hansen T, Franke K. Solitary extramedullary plasmacytoma and granulomatous sialadenitis of the parotid gland preceding a B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Mund-Kiefer-und Gesichtschirurgie. 2006;10:122–5. doi: 10.1007/s10006-006-0673-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vosmik M, Cermanova M, Odrazka K, Maisnar V, Zouhar M, Kordac P, et al. Solitary extramedullary plasmacytoma in the oropharynx: Advantages of intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2007;7:434–7. doi: 10.3816/CLM.2007.n.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hari CK, Roblin DG. Solitary plasmacytoma of the parotid gland. Int J Clin Pract. 2000;54:197–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hussong JW, Perkins SL, Schnitzer B, Hargreaves H, Frizzera G. Extramedullary plasmacytoma. A form of marginal zone cell lymphoma? Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;111:111–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/111.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]