Abstract

Eventhough the lateral sinus floor elevation is a well‐documented procedure, many factors can increase its difficulty. The presence an osteoma can be very challenging and must be managed with caution taking in consideration the lesions's size and extension.

Keywords: lateral approach, osteoma, sinus floors elevation

1. INTRODUCTION

Maxillary sinus grafting is a well‐known procedure that has been used for a long time with high predictability in order to correct vertical bone defects in the posterior region of the maxilla. While the crestal approach is indicated in moderate vertical defects, the lateral approach is used when facing severe maxillary atrophy with a residual ridge height inferior to 6 mm.

Some benign tumors can develop inside of the paranasal cavities such as osteomas. They present as a slow‐growing, usually asymptomatic lesions, characterized by proliferation of compact or cancellous bone. They commonly occur in the frontal sinus, followed by the ethmoid and maxillary sinus. It is rarely encountered in the sphenoid sinus.

The presence of a sinus osteoma can be a challenge if a sinus floor elevation procedure must be performed. To our knowledge, this is the first case report of a maxillary sinus grafting in presence of a sinus osteoma.

Maxillary sinus grafting was first described by Dr Hilt Tatum who modified the Caldwell‐Luc technique in the 1970s, and it has been recognized as a procedure with high predictability to date. 1

Many factors can influence the difficulty and complexity of this intervention and must be thoroughly assessed before a lateral sinus augmentation, such as the presence of a bony septum, the location of the alveolar antral artery, the thickness of the Schneiderian membrane, and more rarely the presence of a sinus osteoma.

Craniofacial osteomas may appear on any bone of the cranium or face or within a paranasal sinus. Osteomas within the paranasal sinus are relatively rare; they are found in 0.01%‐0.43% of patients, of which the frontal sinus is involved in 96%, the ethmoid in 2%, and the maxillary in 2% of cases. The sphenoid sinus is rarely affected. 2 , 3

In case of a maxillary sinus osteoma, the lesion usually appears on the lateral wall of the sinus. 3

The current paper will present and discuss the management of a unitary posterior edentulism (tooth 16) with a severe vertical defect and the presence of an osteoma on the lateral wall of the sinus regarding the edentulous site.

2. CASE PRESENTATION

A 26‐year‐old male patient was referred to the Outpatient and Implantology department of the university dental clinic of Monastir. He was nonsmoker, and the medical history did not reveal any significant systemic diseases.

The chief complaint was the replacement of the right upper first molar (tooth 16) which was extracted 5 years ago due to dental decay.

Clinically, no horizontal defect was objectified, the present prosthetic space and keratinized tissue were sufficient. A panoramic radiograph (OPG) and a Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) were prescribed and showed a severe vertical defect with a residual ridge height of 2 mm.

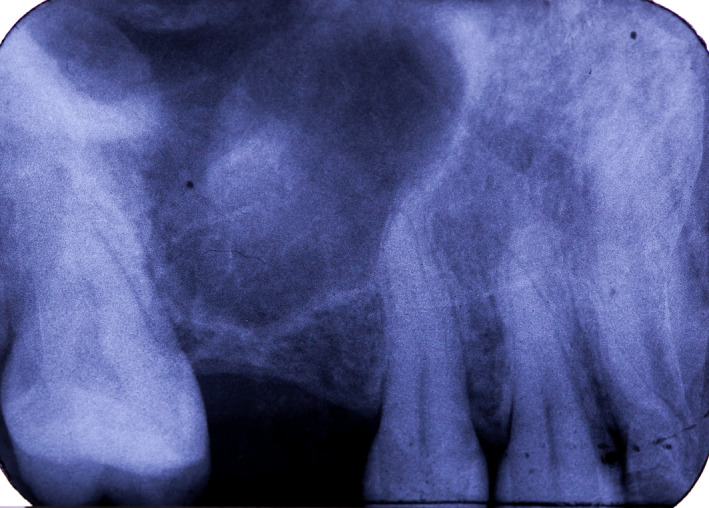

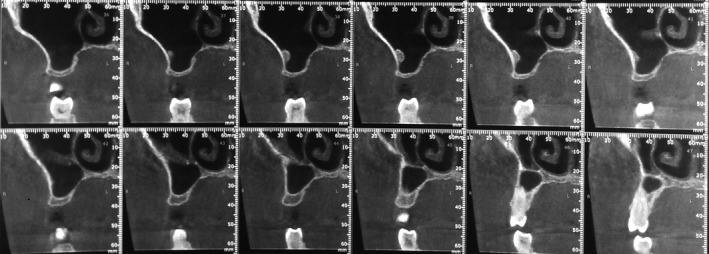

Moreover, on the inner side of the lateral wall of the maxillary sinus, an osteoma was fortuitously discovered. It had a corono‐apical long axis of 8 mm and a mesiodistal width of 5 mm. (Figure 1, Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Preoperative retroalveolar radiography

FIGURE 2.

CBCT oblique coronal sections showing the vertical defect and the sinus osteoma

This benign tumor was completely asymptomatic, but it was located in the site of the missing tooth and would certainly interfere with the lateral window design required in the intended bone augmentation procedure.

Sinus graft with the lateral approach and delayed implant placement was decided. The patient was informed, and consent was obtained.

After an initial mouth rinse with chlorhexidine digluconate 0.2%, local anesthesia was carried using mepivacaïne 2% with epinephrine 1:100 000 (médicaïne® 2%, Médis).

A crestal incision in the edentulous site, completed with an intrasulcular incision regarding tooth 17 and a releasing incision distal to tooth 15, enabled the reflection of a full‐thickness triangular flap with a sufficient visual access to the surgical site.

The excision of the lateral window, along with the part of the osteoma that impeded on it, was performed using piezoelectric instruments (Mectron®) in order to minimize the risk of perforation of the Schneiderian membrane (Figure 3A). The remaining part of the osteoma was kept in place.

FIGURE 3.

A, Osteotomy using the piezoelectric tip. B, Sinus membrane elevation. C, Insertion of the first resorbable membrane. D, Xenograft condensation into the sinus. E, Flap repositioning and sutures. F, Postoperative retroalveolar radiography. G, Delayed implant placement

The sinus membrane was elevated, and a first resorbable membrane was placed beneath it to reinforce it and prevent a possible leak of the bone particles into the antrum (Figure 3B,C).

A xenograft (Apatos—OsteoBiol®/Tecnoss) was condensed to fill the antral cavity (Figure 3D). The site was then covered with a second resorbable membrane, and the flap was repositioned and sutured. (Figure 3E).

A postoperative retroalveolar radiography was immediately taken (Figure 3F). An association of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (1 g every 8 hours for 10 days) was prescribed postoperatively. Sutures were removed after 10 days, and implant placement was programmed in 6 months. (Figure 3G).

3. DISCUSSION

Lateral sinus floor elevation is one of the most widely used augmentation procedures. It enables implant placement in the posterior region of an atrophic maxilla, where the bone is generally reduced as a result of two phenomenons: alveolar ridge resorption due to increased osteoclastic activity following tooth loss and sinus extension due to its pneumatization. 4

While sinus floor elevation by the transalveolar approach is indicated in moderate vertical defects (≥7 mm), the lateral approach is used when facing severe maxillary atrophy (ridge height <6 mm). A minimal residual height of 4 mm indicates immediate implant placement; otherwise, the bone quantity would be insufficient to obtain primary stability, and implant surgery must be delayed (Table 1). 5

TABLE 1.

Jensen's classification following the Sinus Consensus Conference (1996) 5

| Residual ridge height | Case management |

|---|---|

| ≥10 mm (Class A) | Implant placement |

| 7‐9 mm (Class B) | Crestal sinus floor elevation with immediate implant |

| 4‐6 mm (Class C) | Lateral sinus floor elevation with immediate or delayed implant |

| 1‐3 mm (Class D) | Lateral sinus floor elevation with delayed implant |

According to Scarano et al, the flap design when performing the lateral approach plays a significant role in reducing postoperative pain and swelling. In fact, a modified triangular flap with a distal releasing incision proved more efficient than the trapezoidal one. 6

In our case, a triangular flap with a mesial releasing incision was performed. The infraorbital foramen was thoroughly assessed on the preoperative CBCT to avoid injuring the infraorbital artery which could jeopardize the flap's blood supply.

In order to assess the complexity of the lateral sinus floor elevation technique, Tiziano et al 7 suggested a difficulty score based on anatomical and patient‐related factors. Many of these factors were found in our case such as the presence of a medio‐lateral septum and the presence of adjacent teeth since there was only one tooth missing.

The presence of an osteoma is not found in the literature to be a difficulty‐increasing factor. This is probably due to their low frequency in general and more specifically in sinuses requiring a floor elevation procedure.

In our case, the management of the osteoma consisted of a partial excision of the segment impeding on the lateral window. The remaining part will be monitored with periodic radiographs in order to assess its growth rate. The total excision was not indicated since the benign tumor was completely asymptomatic.

According to the meta‐analysis of Jordi et al, the use of rotating burs resulted in a significantly higher risk of membrane perforations during the osteotomy compared to the piezoelectric instruments. The average incidence of perforation during lateral maxillary sinus augmentation drops from 24% for rotating instruments to 8% for piezosurgery. 8 , 9

Medium‐sized osteomas might have required a total excision in the same time as the sinus floor elevation in order to avoid further growth. A two‐stage option can be planned in case of large tumors, starting with the removal of the osteoma followed by the sinus augmentation after a healing period. In this case, an endoscopic approach would be recommended, 10 since the Caldwell‐Luc technique usually makes the sinus floor elevation highly complex because scar tissue is much more difficult to manipulate than the physiological one. 11

4. CONCLUSION

Even though lateral sinus floor elevation is a well‐documented procedure, its complexity is greatly influenced by anatomical and patient‐related factors. A thorough clinical examination completed with a radiographic assessment with CBCT or CT reconstructions is mandatory before the intervention. To our knowledge, this is the first published case of a sinus graft in the presence of a lateral wall osteoma. The management of such obstacles is decided on a case‐by‐case basis after evaluation of the benefit/risk ratio.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

MM: ensured patient follow‐up and manuscript redaction. MT: involved in surgery performance and manuscript revision. AH and RS: involved in manuscript drafting. FK, MSK, and FBA: involved in manuscript revision.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

This manuscript is the authors' own original work, which has not been previously published or considered for publication elsewhere. The paper properly credits the meaningful contributions of co‐authors and co‐researchers. All authors have been personally and actively involved in substantial work leading to the paper and will take public responsibility for its content.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Published with written consent of the patient.

Mlouka M, Tlili M, Hamrouni A, et al. Lateral maxillary sinus floor elevation in the presence of a sinus osteoma: A case report. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9:e04124. 10.1002/ccr3.4124

REFERENCES

- 1. Tatum H Jr. Maxillary and sinus implant reconstructions. Dent Clin North Am. 1986;30:207‐229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Viswanatha B. Maxillary sinus osteoma: two cases and review of the literature. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2012;2012(32):202‐205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zouloumis L, Lazaridis N, Maria P, Epivatianos A. Osteoma of the ethmoidal sinus: a rare case of recurrence. Br J oral maxillofac Surg. 2005;43:520‐522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kopecká D, Šimůnek A, Brázda T, Somanathan RV. Potřeba laterálního sinus liftu při ošetřování dorzálního úseku horní čelisti dentálními implantáty. Čes Stomat. 2006;106(2):56‐58. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jensen OT, Shulman LB, Block MS, Iacono VJ. Report of the sinus consensus conference of 1996. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1998;13(Suppl):11‐13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Scarano A, Lorusso F, Arcangelo M, et al. Lateral sinus floor elevation performed with trapezoidal and modified triangular flap designs: a randomized pilot study of post‐operative pain using thermal infrared imaging. J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;2018(15):1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Testori T, Tavelli L, Yu S‐H, et al. Maxillary sinus elevation difficulty score with lateral wall technique. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2020;35(3):631‐638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wallace SS, Mazor Z, Froum SJ, Cho SC, Tarnow DP. Schneiderian membrane perforation rate during sinus elevation using piezosurgery: clinical results of 100 consecutive cases. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2007;27(5):413‐419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jordi C, Mukaddam K, Lambrecht JT, Kühl S. Membrane perforation rate in lateral maxillary sinus floor augmentation using conventional rotating instruments and piezoelectric device—a meta‐analysis. Int J Implant Dent. 2018;4(1):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Romano A, Dell’Aversana Orabona G, Pansini A, et al. Endoscopic approach for paranasal sinuses osteomas: our experience and review of literature. Oral Maxillofac Surg Cases. 2019;5(2):100094. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Šimůnek A, Kopecká D, Brázda T, Somanathan RV. Is lateral sinus lift an effective and safe technique? Contemplations after the performance of one thousand surgeries. Implantologie J. 2007;5:1–5. [Google Scholar]