Abstract

KfrC proteins are encoded by the conjugative broad-host-range plasmids that also encode alpha-helical filament-forming KfrA proteins as exemplified by the RA3 plasmid from the IncU incompatibility group. The RA3 variants impaired in kfrA, kfrC, or both affected the host’s growth and demonstrated the altered stability in a species-specific manner. In a search for partners of the alpha-helical KfrC protein, the host’s membrane proteins and four RA3-encoded proteins were found, including the filamentous KfrA protein, segrosome protein KorB, and the T4SS proteins, the coupling protein VirD4 and ATPase VirB4. The C-terminal, 112-residue dimerization domain of KfrC was involved in the interactions with KorB, the master player of the active partition, and VirD4, a key component of the conjugative transfer process. In Pseudomonas putida, but not in Escherichia coli, the lack of KfrC decreased the stability but improved the transfer ability. We showed that KfrC and KfrA were involved in the plasmid maintenance and conjugative transfer and that KfrC may play a species-dependent role of a switch between vertical and horizontal modes of RA3 spreading.

Keywords: alpha-helical KfrC protein, broad-host-range RA3 plasmid, IncU (IncP-6) group, active partition, conjugative transfer

1. Introduction

The existence of a complex filamentous network called the cytoskeleton that spatially organizes the content of a cell has long been regarded as typical for eukaryotic cells. About 30 years ago, the bacterial cell division tubulin-like protein FtsZ, which was able to self-assemble into fibers, was discovered. It initiated the identification of various prokaryotic cytoskeletal proteins that are homologous to all three major types of filament-forming proteins comprising the eukaryotic cytoskeleton: actin (e.g., MreB, FtsA, MamK, and Alp), tubulin (e.g., FtsZ, TubZ, and PhuZ) and intermediate filament IF (e.g., crescentin) [1,2,3]. These proteins have been shown to fulfill pivotal cellular functions (reviewed in [4,5]) such as cell wall synthesis, maintenance of a cell’s shape, cell division, as well as DNA segregation and organization of intracellular components [6]. Besides the canonical cytoskeletal proteins, a variety of filament-forming proteins found in bacteria have no eukaryotic homologs, highlighting the complexity of the bacterial cytoskeleton. Among them are the Walker A Cytoskeletal ATPases (WACAs), a widely distributed subfamily of the P-loop NTPases that form ATP-dependent filaments involved in DNA segregation and cell division [7], and bactofilins performing a range of different cytoskeletal tasks [7,8]. Furthermore, there is a growing group of coiled-coil-rich proteins (CCRPs) that are putatively able to polymerize into filamentous structures in a nucleotide-independent manner mediated by the coiled-coils but lacking in typical features of eukaryotic IF proteins. They are considered as a component of the bacterial cytoskeleton or to play an auxiliary function, but, so far, they have not been investigated as extensively as the aforementioned proteins [5,9,10].

Prokaryotic cytoskeletal proteins have been found encoded not only chromosomally but also by phages [11,12] and the low-copy-number plasmids from different incompatibility groups in which they convey the function of plasmid DNA segregation [7]. Noticeably, the conjugative plasmids of the IncP, IncU, IncW, and PromA groups that are able to replicate, be stably maintained, and efficiently disseminate in a broad range of hosts encode the alpha-helical, coiled-coil-containing, DNA-binding proteins, designated KfrAs [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. It has been recently shown that the presence of KfrAs is widely spread in various species [18]. At least for the IncP and IncU homologues, it was shown that filament-forming KfrAs play an accessory function in the proper plasmid segregation [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. In the same two groups of the BHR conjugative plasmids, KfrAs are accompanied by presumably alpha-helical proteins, designated KfrCs, with which KfrAs interact [13,18,21]. The questions how they act and what exactly their auxiliary role is in plasmid segregation remain unanswered.

The object of our research, conjugative broad-host-range RA3 plasmid, an archetype of the IncU incompatibility group (designated IncP-6 in Pseudomonas spp), is a unit-copy replicon of 45.9 kb (GeneBank Accession no. DQ401103) that is able to transfer and be maintained in Alpha-, Beta- and Gammaproteobacteria [22]. The RA3 backbone genome contains the clusters of functionally related genes, designated the replication, the stability, and the conjugation modules.

The backbone functions are regulated by several autoregulators [23,24] and two global regulators, KorB and KorC, coordinating all plasmid functions (Figure 1A) [17,25]. An additional regulatory mechanism detected during analysis of the RA3 stability module expression is based on the transcriptional organization of this module and adjusts the particular gene transcript dosage to the various hosts (Figure 1B) [26]. Two important cis-acting sites, parS, the centromere-like site of the active partition system, and oriT, the origin of the conjugative transfer, are adjacent in the RA3 genome (Figure 1C) and may impose a steric hindrance between segrosome [24] and relaxosome complexes [27]. Within the stabilization module, upstream of the type Ia active partition system encoding KorB of the ParB family and IncC, the Walker-type ATPase of the ParA family, there are two structural genes for alpha-helical proteins KfrA and KfrC [22,28]. It has been shown recently that KfrA acts as a transcriptional autoregulator and is able to form long filamentous structures in the presence of plasmids carrying its cognate binding site [18,29]. Moreover, it forms a complex with KfrC and with both active partitioning proteins, KorB and IncC [18]. The highly unstable test plasmid that was stabilized by the presence of the RA3 stability module displayed the increased segregation rate in some hosts when deprived of the kfrA operon [26,29] and/or kfrC [18]. To better understand the functions the Kfr proteins play in the RA3 plasmid biology, the present study focused on the detailed analysis of the KfrC properties and on a wide-range search for KfrC partners among the plasmid RA3- and host-encoded proteins.

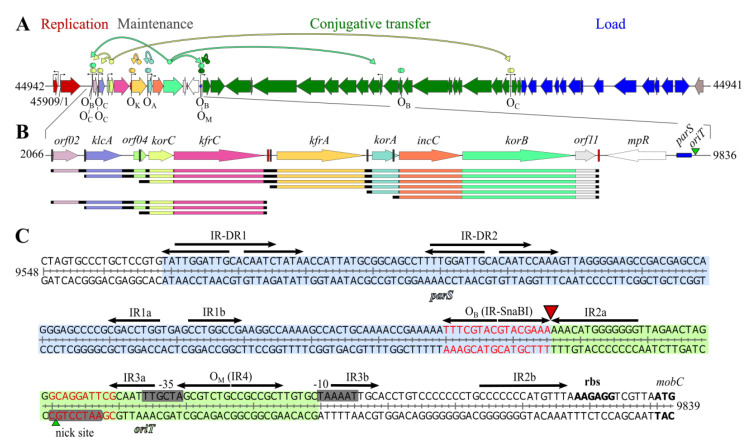

Figure 1.

Genetic organization of RA3 plasmid from IncU incompatibility group (GenBank: DQ401103.1). (A) Linear map of RA3 plasmid. The replication module is in red, stability module is multicolored (close-up in Panel B), the conjugative module in green, and integron in blue. ORFs are represented by thick arrows that point out the direction of transcription. Thin black arrows in the backbone fragment indicate the transcription start sites (TSS). The colored arrows connecting the regulatory genes with the action sites of their products demonstrate the regulatory circuits (OA-operator for KorA, OB for KorB, OC for KorC, OK for KfrA, and OM for MobC). (B) RA3 maintenance module with the identified variants of the transcripts for particular genes [26]. Black boxes indicate promoters and red boxes depict Rho-independent transcriptional terminator sites. A cis-acting site in partition, parS, marked as a blue rectangle, is located in the vicinity of the origin of conjugative transfer oriT, marked as a green triangle. (C) DNA sequence of RA3 parS/oriT region located at the border of the maintenance and conjugative transfer modules. Direct motifs (DR) and arms of inverted repeats (IR) are depicted by arrows. The centromere-like parS region encompassing the binding site OB (IR-SnaBI) for partitioning protein KorB preceded by IR-DRs is highlighted in blue [24]. The oriT region located between OB and including OM (operator for MobC) overlaps mobCp (grey boxes) and is highlighted in green. The conserved nick motif is circled in grey with a green triangle indicating a relaxase nicking site. The ribosome binding site (rbs) and start codon for MobC are in bold. The parS and oriT sequences deleted in RA3 mutants are denoted in red whereas the site of DNA insertion to separate parS and oriT motifs is pointed out by a red triangle.

Using this approach, we identified the conjugative coupling protein VirD4 as the KfrCRA3 partner and mapped their interaction domains. The interplay between the conjugative transfer and the active segregation processes was demonstrated. KfrC plays an important species-dependent role in the switch between the horizontal and vertical spreading of RA3.

2. Results

2.1. Role of KfrA and KfrC in the Stable Maintenance of RA3 Derivatives in Various Hosts

Previous studies on KfrARA3 and KfrCRA3 roles in the stability of the low-copy-number plasmid were conducted with the use of the test vector pESB36 based on the RK2 minireplicon [26]. The very unstable pESB36 was efficiently stabilized by the presence of the orf02-orf11 RA3 stability module in the E. coli strain as well as in the other tested hosts but to a various extent. Deletion of either kfrs from the module or even substitution of WT kfrA by the mutated allele kfrAL43A, producing KfrA unable to bind specifically to DNA, led to the high plasmid instability in E. coli [18] and in other hosts. It seemed important to follow the effects of kfrs deletions on maintaining of the whole RA3 plasmid, i.e., in the presence of the immanent replication system and the conjugative transfer module.

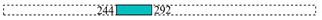

Deletion mutants of RA3, RA3ΔkfrA, RA3ΔkfrC, and RA3Δ(kfrC-kfrA), were constructed by replacing particular ORF(s) with the Kmr cassette [30]. For each RA3 deletion derivative, the growth rate and the stability functions were determined in the various hosts. The presence of WT RA3 decreased the growth rate by 25% and clearly increased the number of filamentous cells (> 4 µm) from 19% in DH5α to 37% in DH5α(RA3) given the average cell length elevated by 31% (Figure 2A,B). Deletion of the kfrC gene potentiated the effect of filamentation shifting the number of cells longer than 4 µm up to 70% and the average cell length about 75% in comparison to DH5α (from 3.23 µm to 5.66 µm). Hence, the presence of RA3 deprived of kfrC disturbs cell division, leading to the further filamentation and the longer generation time (Figure 2B). Notably, monitoring the plasmid retention during approximately 60 generations of growth without a selection demonstrated loss of neither of the four plasmids in the E. coli host (inset in Figure 2A).

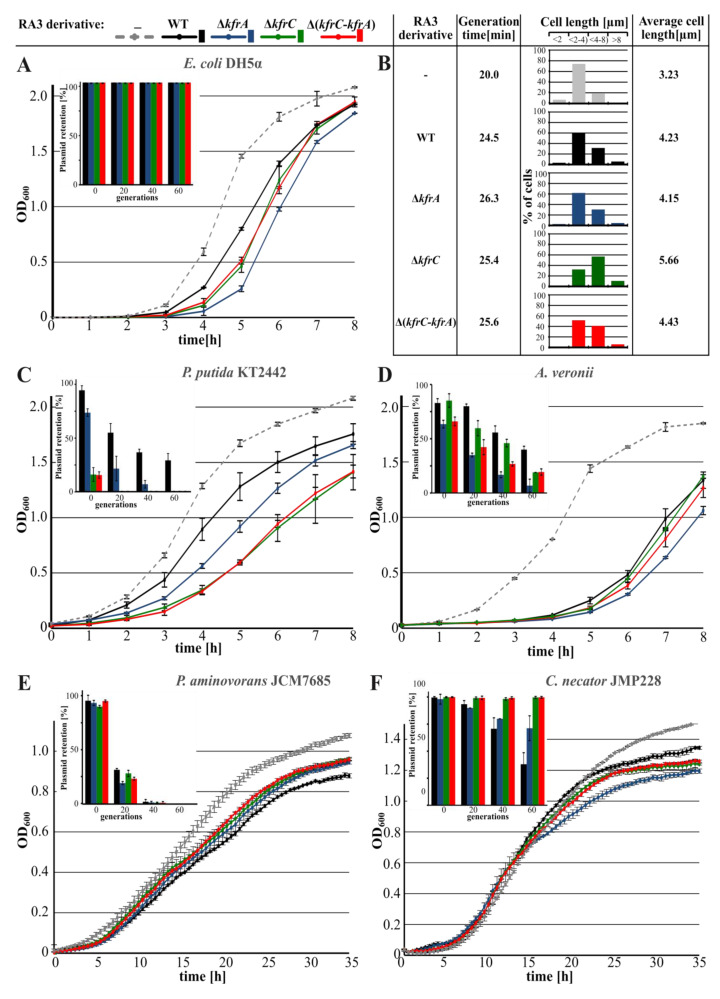

Figure 2.

RA3 deletion variants in various hosts. (A) Growth of E. coli DH5α strain transformed with various RA3 derivatives. The inset demonstrates the results of the stability experiment carried on in triplicates. Plasmid retention was analyzed during 60 generations of growth without selection, estimated every 20 generations as the % of antibiotic-resistant colonies. (B) Generation time of the DH5α transformants was calculated based on the colony forming units (c.f.u.) at different time points. Microscopic observations of DAPI-stained cells were the basis for the cell size profiling and calculation of the average cell length. (C) Growth and plasmid stability (inset) of the RA3 transconjugants of P. putida KT2442 strain. (D) Growth and plasmid stability (inset) of the RA3 transconjugants of A. veronii strain. (E) Growth and plasmid stability of the RA3 transconjugants of P. aminovorans JCM7685 strain. (F) Growth and plasmid stability of the RA3 transconjugants of C. necator JMP228 strain. Transformants and transconjugants were grown in L broth at the appropriate temperature and streptomycin concentration. Broken lines represent growth curves of the plasmid-less hosts grown without antibiotic. The presented results are representative of three experiments and show average from three biological repeats (cultures grown in parallel) with standard deviation.

WT RA3 and three deletion mutants were introduced via conjugation into two other strains of Gammaproteobacteria, Pseudomonas putida and Aeromonas veronii, and the representative strains of Alpha- and Betaproteobacteria, Paracoccus aminovorans and Cupriavidus necator, respectively. The growth of P. putida KT2442, similarly to DH5α, was retarded in the presence of RA3 plasmid (Figure 2C). While removal of KfrA increased generation time from 41 min to 44 min, the presence of RA3ΔkfrC and RA3Δ(kfrC-kfrA) extended generation time to 49 min. Here, the results were in-line with the decreased retention of RA3 derivatives. RA3ΔkfrA segregated slower than the other two variants, RA3ΔkfrC and RA3Δ(kfrC-kfrA), which were lost from the population after only 20 generations of growth without selection (inset in Figure 2C).

In A. veronii, only the presence of RA3ΔkfrA increased the generation time by 5% despite that all three deletion derivatives were less stable than WT RA3. Among them, RA3ΔkfrA segregated quicker than the two other mutants did (Figure 2D).

No clear difference in the growth rate and stability was observed between transformants carrying WT RA3 and its three derivatives in P. aminovorans of Alphaproteobacteria (Figure 2E).

In C. necator of Betaproteobacteria, seemingly no effect on growth rate was observed in transconjugants of all three derivatives in comparison to the WT RA3 transconjugant (Figure 2F). Stability experiments, however, demonstrated increased retention of the RA3 variants with deletions in the kfr genes in comparison to WT RA3 (inset in Figure 2F), suggesting the negative interference of Kfrs in the stable maintenance of RA3 in this host.

2.2. KfrCRA3 Structure

KfrC of RA3 (355 amino acids) is homologous (68% identity) in the first 240 residues to the N-terminal part of KfrC (448 amino acids) from RK2 (IncPα). Interestingly, this N-terminus of KfrCRK2 is deleted in the representatives of IncPβ, e.g., R751 (Figure 3A). Since the remaining part of KfrCRA3 (115 amino acids) has no homologs in the database, the kfrCRA3 gene was split accordingly into two fragments (encoding 1–249 and 244–355 amino acids) to find out their potential functions. The predicted model of KfrCRA3 by I-TASSER is shown in Figure 3B, with two domains differently colored. The N-terminal domain not only contains conserved 5-phosphoribosyl-1-pyrophosphate (PRPP) binding motif (V56-H173) (Figure 3A) but also has the characteristic fold of phosphoribosyltransferase (PRT)-type I domain (Pfam: PF00156).

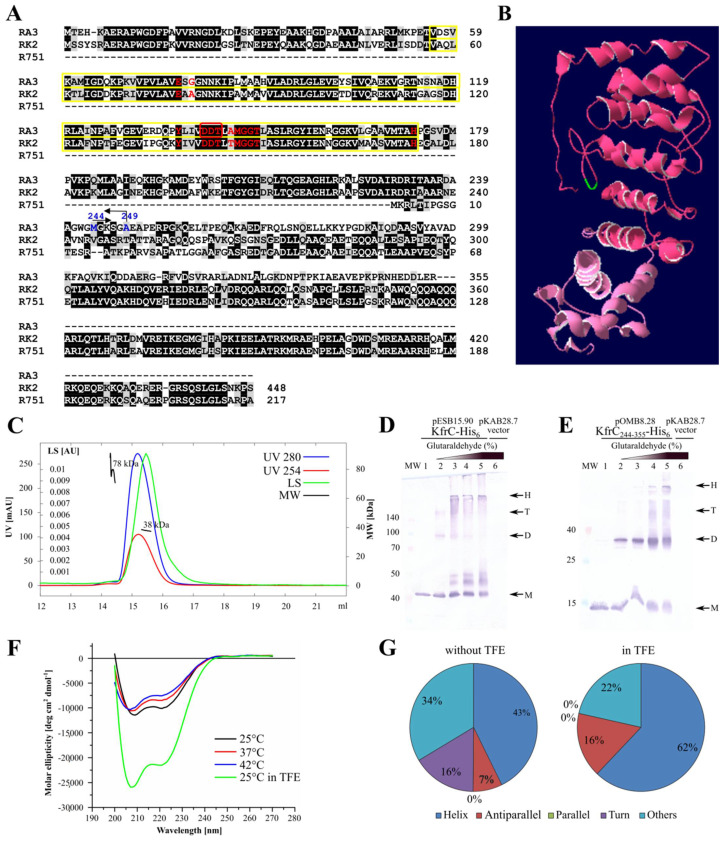

Figure 3.

KfrCRA3 structure analysis. (A) Alignment of the closest homologs of KfrCRA3 (IncU) [ABD64834.1], KfrCRK2 (IncP-1α) [CAJ85732.1], and KfrCR751 (IncP-1β) [AAC64416.1]. Identical residues are shadowed in black, similar in grey. Phosphoribosyltransferase (PRT)-type I domain (Pfam: PF00156) is encircled yellow, putative active sites indicated with red font. The KfrCRA3 residues substituted by alanine are encircled red. Residues in blue indicate the ends of the KfrCRA3 truncations. (B) Structural KfrCRA3 model predicted by I-TASSER [32]. N-terminal region is highlighted in dark pink, C-terminal region in light pink. The KfrCRA3 residues substituted by alanine are indicated in green. (C) SEC-MALS analysis. The column was equilibrated with 50 mM NaPi buffer (pH 7.5), 0.15 M NaCl and KfrC-His6 tagged protein was dissolved in the same buffer at the final concentration of 1 mg mL−1. The chromatograms display curves for the light scattering (LS) and UV readings at 280 nm and 254 nm, in green, blue, and red, respectively. The scale for the LS detector is shown on the left-hand axis. The black lines (MW) indicate the calculated mass of the eluted protein (scale on the left-hand axis). The predicted molecular mass of KfrC-His6 monomer is 40.11 kDa. (D,E) In vivo crosslinking of the tagged KfrC-His6 and KfrC244-355-His6 proteins. The cell extracts of BL21(DE3) transformants containing overproduced proteins were used in the crosslinking reactions with different concentrations of glutaraldehyde. The predicted molecular mass of KfrC244-355-His6 monomer is 14.48 kDa. Complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-His6 antibodies. Arrowheads indicate detected signals for monomers (M), dimers (D), tetramers (T), as well as the higher molecular aggregates (H). Lane MW—molecular weight marker [kDa], lanes 1–5—increasing concentrations of glutaraldehyde: 0%, 0.001%, 0.002%, 0.005%, and 0.01%, respectively. The extract of BL21(DE3) strain containing pKAB28.7 (T7p-his6) was used as a control with 0.01% glutaraldehyde (lane 6). (F) Far-UV circular dichroism spectra. The CD spectra were measured at various temperatures, and with the addition of TFE at a temperature of 25 °C. (G) The secondary structures estimated with the BestSel program [33] for KfrCRA3 with or without the addition of TFE at a temperature of 25 °C are presented.

The model of KfrCRA3 by I-TASSER predicted the high content of alpha-helices (Figure 3B). To verify it, the kfrC gene was cloned into pET28 derivative (pESB15.90) and the KfrC-His6 protein was purified by affinity chromatography. It was shown that C-terminally His6-tagged KfrC (pOMB9.29), when over-produced in E. coli, retained the properties of the intact KfrC (see the next section).

The purified KfrC demonstrated the dominance of the monomeric form (40 kDa) in solution as shown via SEC-MALS analysis (Figure 3C). The KfrC potential to dimerize was tested during in vitro experiments by the use of the cross-linking agent glutaraldehyde (GA). After cross-linking the extracts of induced BL21(DE3) pESB15.90 (kfrC-his6) or pOMB8.28 (kfrC244-355-his6), transformants were separated by PAGE and KfrC was visualized by Western blotting with anti-His tag antibodies. The extract from BL21(DE3) pKAB28.7 (empty vector) was also treated with 0.1% glutaraldehyde and used as a control (Figure 3D,E). The ability of KfrC to form dimers and the higher-order complexes was demonstrated. A similar spectrum of complexes was observed after cross-linking of KfrC244-355, pointing out this part of KfrC as the dimerization domain.

The secondary structure of KfrC was analyzed using the circular dichroism method (Figure 3F,G). It confirmed the alpha-helical structure of KfrC in the range of temperatures between 25 °C and 42 °C. Addition of TFE (2,2,2-trifluoroethanol) [31] promoted the stability of the molecules, increasing the estimated alpha-helix content from 43% to 62%.

2.3. Inhibition of Hosts’ Growth by the Abundance of Kfr Proteins

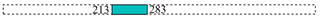

The WT kfrC gene and the 3′ kfrC fragment encoding KfrC244-355 were cloned into the high-copy-number expression vector pGBT30 and overproduced in the E. coli DH5α strain. Overexpression of the intact kfrC from pESB5.88 caused significant retardation of the host growth (Figure 4A) as overproduction of KfrC-His6 did (pOMB9.29). The abundance of the C-terminal fragment of KfrCRA3 (pOMB9.18) did not affect the bacteria growth whereas attempts to clone the kfrC1-249 under tacp into pGBT30 led to the various plasmid DNA rearrangements. Since the N-terminal part of KfrCRA3 was predicted to encode a putative phosphoribosyltransferase, it was decided to modify the postulated enzymatic center (DDT motif at positions 141–143, Figure 3A) by the triple alanine substitutions. The clone was stable and the variant designated KfrC * when overproduced (pOMB9.31) did not cause growth retardation of the E. coli DH5α transformant (Figure 4A). This suggests that the toxicity of KfrC might be related to its putative enzymatic activity.

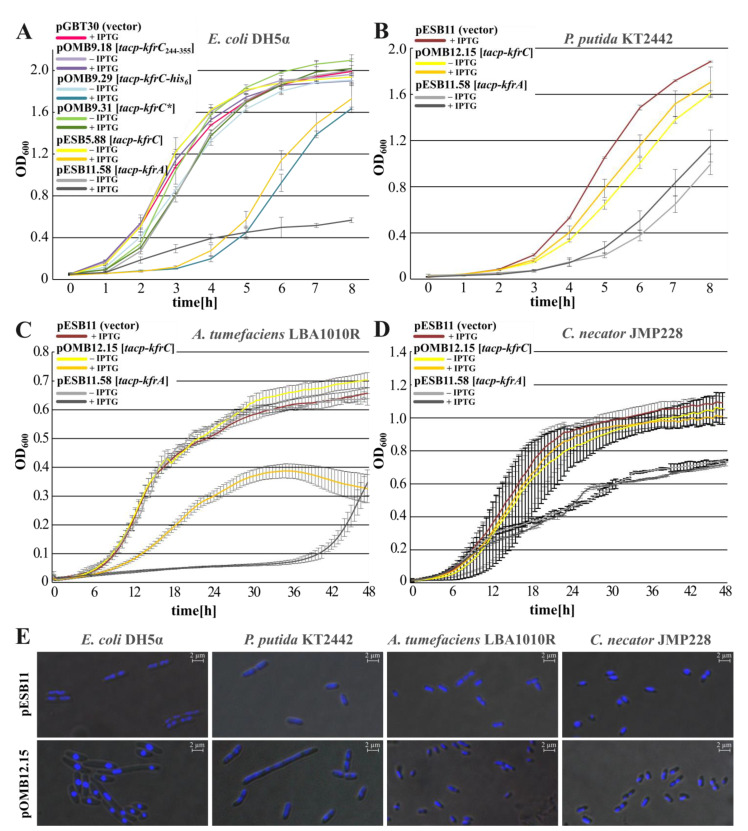

Figure 4.

Overproduction of Kfr proteins. Transformants and transconjugants were grown in the selective L broth with and without 0.5 mM IPTG at the appropriate temperature. The presented results are representative of three experiments and show the average from three biological repeats (cultures grown in parallel) with standard deviation. (A) Effects of KfrA and KfrC variants abundance in E. coli DH5α strain. (B) Effects of KfrA and KfrC abundance in P. putida KT2442, (C) in A. tumefaciens LBA1010R, and (D) in C. necator JMP228. (E) Microscopic observations of DAPI-stained transconjugants cells carrying either an empty vector pESB11 or pOMB12.15 overproducing KfrC. Images were intensified when required.

To analyze the KfrC overproduction effect in other RA3 hosts, the kfrC was re-cloned under control of tacp into mobilizable pESB11, the modified BHR vector to obtain pOMB12.15. The excess of KfrC on the host growth was tested in P. putida, another representative of Gammaproteobacteria, Agrobacterium tumefaciens, the representative of Alphaproteobacteria, and C. necator of Betaproteobacteria. The KfrC “toxicity” was clearly host-dependent. Strong growth inhibition was observed in A. tumefaciens (Figure 4C), the weaker inhibition in P. putida (Figure 4B), and no effect of KfrC overproduction was observed in C. necator (Figure 4D).

Microscopic observations of various hosts cells carrying pESB11 (vector) or pOMB12.15 (tacp-kfrC), grown in the presence of 0.5 mM IPTG, revealed strong condensation of the nucleoids in the presence of KfrC excess in P. putida and E. coli. Weaker condensation effects were observed in A. tumefaciens and C. necator (Figure 4E). The species-characteristic reactions on the excess of KfrC, e.g., growth retardation, nucleoids condensations, suggested variability of KfrC targets in these hosts. Since KfrC forms a complex with the KfrA [18], the effects of KfrA overproduction were also analyzed after mobilization of pESB11.58 (tacp-kfrA) to the various strains. The KfrA excess affected growth of all tested hosts much stronger than the excess of KfrC did (Figure 4A–D).

2.4. Mapping of the KfrC Domain of Self-Interactions and Interactions with KfrA and KorB

Previous BACTH analysis [18] showed that KfrC and KfrA strongly interacted with each other. The ability to form a complex between these two alpha-helical proteins was also confirmed by coimmunoprecipitation experiments. The domain of interactions between KfrA and KfrC was mapped to the long alpha-helical tail (KfrA54–355) with the fragment KfrA54–177 exhibiting much stronger association with KfrC than KfrA178–355 [18]. In this work, mapping of the KfrC domain of self-interactions and interactions with the previously identified partners, KfrA and KorB, was undertaken.

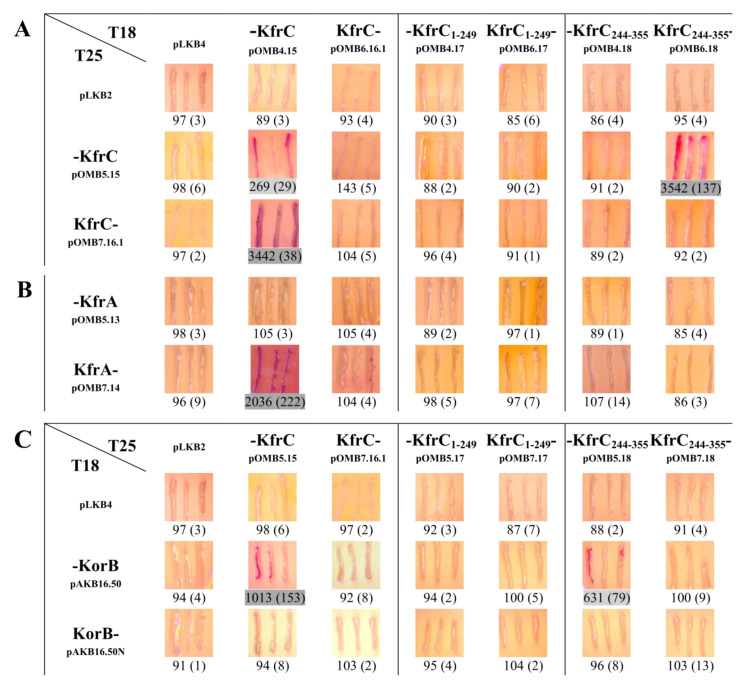

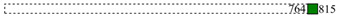

Two gene fragments (kfrC1–249, kfrC244–355) and the intact kfrC were cloned into the four vectors of BACTH [34] system facilitating translational fusions with the CyaA fragments from N- or C-termini. Re-constitution of the CyaA activity as a result of interactions between the hybrid proteins leads to the expression of sugar catabolic genes such as mal or lac operons. The ability to interact was tested on indicator MacConkey plates with maltose and activity of β-galactosidase was assayed in the liquid cultures of the E. coli BTH101 cyaA transformants. The KfrC dimerization domain was mapped to the C-terminal 112 amino acids KfrC244–355 (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Mapping of the KfrCRA3 domains using the BACTH system. Analysis of domains involved in the homodimerization (A) and heterodimerization with KfrA (B) and KorB (C). Double transformants of E. coli BTH101 with compatible plasmids encoding CyaA fragment T18 or T25 fused to the analyzed proteins from N- or C-terminus were tested on indicator MacConkey plates with maltose as a carbon source and by β-galactosidase assays in the liquid cultures. Dark (purple) streaks are indicative of interactions between the two hybrid proteins. Numbers below the images represent β-galactosidase units from at least three experiments with SD in brackets. Dark grey and light grey shadings indicate strong and weak interactions, respectively. Double transformants with one empty BACTH vector versus vector encoding the full-length protein were used as the controls (the first column).

Splitting KfrC into two parts abolished strong interactions between KfrA and KfrC proteins, suggesting that either the intact KfrC was required to form a complex with KfrA or the genetic manipulation impaired the interaction domain in KfrCRA3 (Figure 5B).

Previously, it was demonstrated that both components of the Kfr complex had the ability to interact with the RA3 segrosome proteins and KfrA interacted strongly with KorB (ParB homolog) and weakly with IncC (ParA homolog), whereas KfrC interacted only with KorB [18]. Here, we mapped the domain of interactions with KorB to the C-terminal dimerization part of KfrC, KfrC244–355 (Figure 5C).

2.5. Search for the KfrCRA3 Partners

A wide genomic approach was undertaken to search for putative partner proteins encoded in the E. coli and A. veronii genomes since Aeromonas spp are the most widely spread RA3 hosts in the aquatic environments [35]. The high-quality (>95% inserts) genomic libraries of these two organisms (producing “prey” polypeptides) were prepared in the high-copy-number BACTH vector pUT18C [34] (Figure S1). The “bait” proteins, CyaAT25-KfrC (pOMB5.15) or KfrC-CyaAT25 (pOMB7.16.1), were produced in the BTH101 transformants. Selection of the possible interactants was conducted by plating BTH101 double transformants on the minimal medium with maltose as a carbon source, antibiotics, X-gal, and IPTG added to follow simultaneously the expression of the lac operon. Plasmid DNA isolated from the chosen “positive” clones was used to transform BTH101 with the appropriate bait plasmid using the same medium. Two-step screening allowed us to diminish the pool of the “false positives”. Plasmid DNA isolated from the chosen clones was sequenced. The results of this search are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

KfrCRA3 interactants identified in E. coli DH5α and A. veronii library screenings.

| Library | DNA Coordinates (Peptide) * | Gene | Predicted Function ** | NCBI Accession Number | Number of Clones |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli DH5α | 792619 (209–332) | edd | phosphogluconate dehydratase | WP_001069467.1 | 1 |

| 1321046 (266–446) | fadL | long-chain fatty acid transporter | WP_001295701.1 | 1 | |

| 2535141 (76–228) | yhjJ | Zn-dependent peptidase | WP_001163141.1 | 1 | |

| 3019820 (475–614) | btuB | vitamin B12 transporter | WP_000591359.1 | 1 | |

| 3869607 (138–272) | cof | HMP-PP phosphatase | WP_001336137.1 | 1 | |

| 4142310 (494–648) | ybgQ | outer membrane usher protein | WP_001350492.1 | 1 | |

| 4242142 (25–171) | ompX | outer membrane protein OmpX | WP_001295296.1 | 1 | |

| Most similar Protein (BLASTP) | Number of Clones | ||||

| A. veronii | Protein Length (Peptide) § | Predicted Function ** | NCBI Accession Number | ||

| 354 (103–354) | 3-deoxy-7-phosphoheptulonate synthase | WP_113739212.1 | 1 | ||

| 403 (184–403) | EAL domain-containing protein | WP_064340963.1 | 1 | ||

| 385 (187–327) | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | WP_129504156.1 | 1 | ||

*—position in the E. coli DH5α genome of the first nucleotide fused to cyaA fragment; amino acid residues of the fused polypeptides are indicated in brackets; **—potential function based on the comparison of protein domains, §—length of the A. veronii protein most similar to the fusion protein fragment; amino acid residues of the fused polypeptides are indicated in brackets.

Screening of both libraries from E. coli and A. veronii identified mainly membrane-associated proteins and several enzymes engaged in the phosphometabolism. Since clones in the libraries encoded the fragments of the structural genes, it was necessary to validate the results by cloning complete ORFs into the BACTH system. The vast majority of the analyzed ORFs lost the ability to interact with KfrC in the plate tests, although there were a few that sustained this activity (Figure S2). Further studies are required to establish the functional connections between KfrC and these proteins.

Another approach was taken to identify the KfrC frontline partners, besides KfrA, among proteins encoded by the RA3 plasmid (Table 2). The genomic library of RA3 was prepared in the same high-copy-number pUT18C vector and screened in the same way as the bacterial genomic libraries. The identified partners were KfrC itself (3 clones), VirB4 (2 clones), and VirD4 (17 clones). Both VirB4 and VirD4 presumably have the ATPases activities and are components of the T4SS (Type IV secretion system) involved in the RA3 conjugation. During conjugation VirD4, the coupling protein (CP), is assumed to deliver the relaxosome complex of relaxase bound at oriT with the single-stranded plasmid DNA to a membrane-associated transferosome complex. VirB4 is a part of a transmembrane channel interacting directly with the CP and participating in the relaxosome secretion [36].

Table 2.

Screening of the RA3 library.

| Bait | Coordinates * | Prey | Number of Clones | Cloned Fragment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KfrC-T25 | 16,448 | VirD4 | 1 |

|

| 16,451 | 8 |

|

||

| 16,511 | 1 |

|

||

| 16,931 | 3 |

|

||

| 17,633 | 1 |

|

||

| T25-KfrC | 17,501 | VirD4 | 2 |

|

| 17,549 | 1 |

|

||

| 24,447 | VirB4 | 2 |

|

|

| 4307 | KfrC | 3 |

|

*—position of the first nucleotide of the fused fragment from the RA3 plasmid sequence.

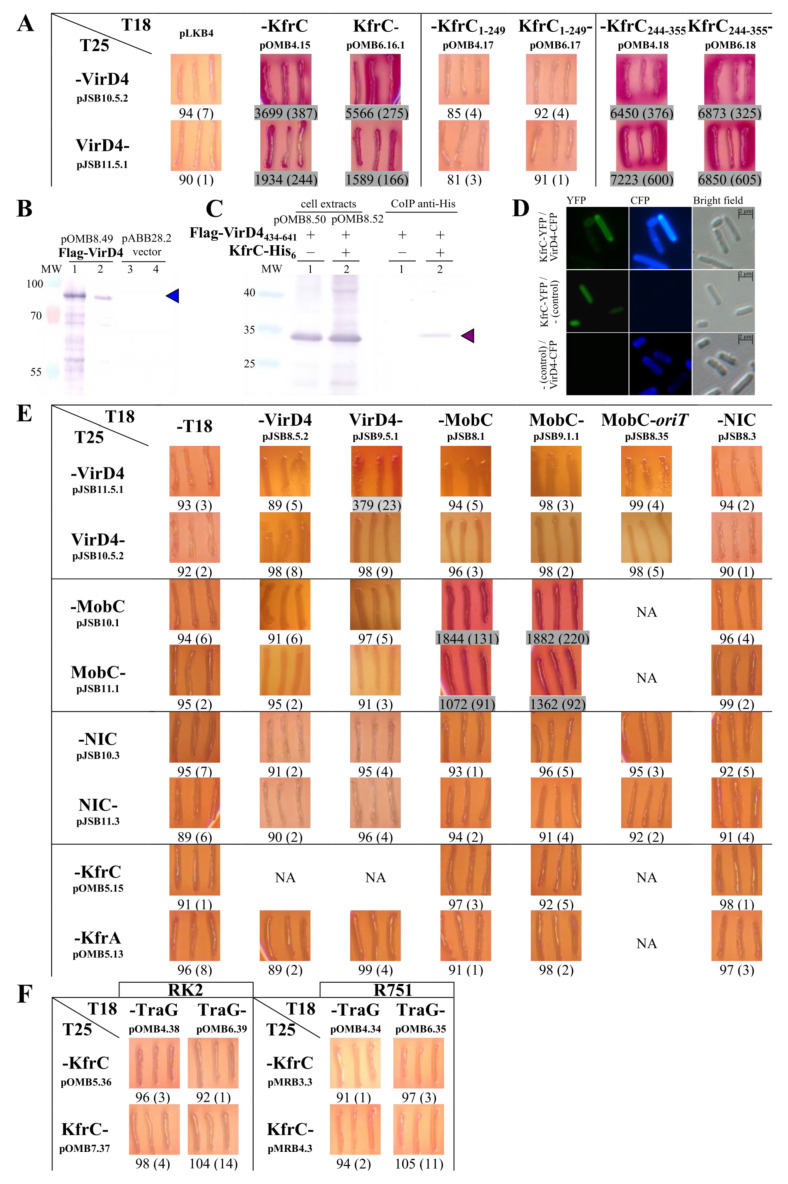

Fourteen of the 22 “positive” clones of the RA3 library contained variable-length C-termini of VirD4. It confirmed that the main interaction domain was inherent to the last 46 residues of VirD4 (Table 2). The three clones fished out with CyaAT25-KfrC demonstrated interactions with a central part of VirD4 (244–283 residues), which suggested the possibility of two VirD4 domains of interactions with KfrC. To verify the interactions of the full ORF, virD4 was cloned into the BACTH system and strong interactions between KfrC and VirD4 were demonstrated. It was also shown that the C-terminal part of KfrCRA3 is engaged in the interactions with VirD4 (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

KfrCRA3 interactions with the conjugative coupling protein VirD4 and with the relaxosome proteins. (A) Mapping of the VirD4RA3 interaction domain within KfrCRA3. The detailed description as in Figure 5. (B) Overproduction of FLAG-tagged VirD4RA3 (arrowhead) analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with anti-FLAG antibodies. Lane 1 and 2—the cell debris and the soluble fraction of E. coli BL21(DE3) (pOMB8.49) extract, respectively. Lane 3 and 4—the cell debris and the soluble fraction of E. coli BL21(DE3) (pABB28.2) extract, respectively. (C) Immunoprecipitation of complexes between KfrCRA3 and VirD4434–641. FLAG-VirD4434–641 was overproduced in BL21(DE3) either from pOMB8.50 (T7p-flag-virD4434–641) or together with KfrC-His6 from pOMB8.52 (T7p-flag-virD4434–641-kfrC-his6). After immunoprecipitation with anti-His antibodies, proteins were separated by PAGE and screened with anti-FLAG antibodies in the Western blot procedure. Initial cellular extracts (left), proteins immunoprecipitated with the use of anti-His antibodies (right). Arrowhead, FLAG-VirD4434–641 (26 kDa). Lane MW—molecular weight markers [kDa]. (D) Colocalization of KfrCRA3-YFP (pAKB2.70) and VirD4RA3-CFP (pOMB12.74) in E. coli DH5α cells assayed by the fluorescence microscopy. Images were taken with the use of the appropriate filters for the two proteins in question. Bright field images served as the controls. (E) Interactions between RA3 relaxosome proteins NIC and MobC, the coupling protein VirD4, and Kfr proteins. The detailed description as in Figure 5. NA, not assayed in this set of tests. (F) Interactions between homologs of KfrC and VirD4 (TraG) of IncP plasmids, RK2 (IncPα), and R751 (IncPβ). Reciprocal plasmid combinations with TraG fusion proteins produced from the low-copy-number pKT25 and KfrC from pUT18 derivatives gave the same negative results.

Attempts to demonstrate interactions between full-length FLAG-VirD4 and KfrC-His6 in the extracts of BL21(DE3) transformants by Co-IP were unsuccessful because VirD4 was found in the cell debris fraction after sonication (Figure 6B). Since the N-terminal part of VirD4 contains a putative transmembrane domain, it was decided to tag only the C-terminal part—VirD4434-641. The KfrC–VirD4 interactions were then confirmed by Co-IP between KfrC-His6 and FLAG-VirD4434–641 (Figure 6C). FLAG-VirD434–641 was detected in the precipitate obtained with the use of anti-His antibodies. Finally, it was decided to see whether putative partners colocalize in a cell. Both KfrC and VirD4 were fluorescently labelled as KfrC-YFP and VirD4-CFP. Proteins were produced from the compatible expression vectors, pAKB2.70 and pOMB12.74, respectively, and introduced to the E. coli DH5α strain separately or together (Figure 6D). KfrC-YFP gave a dispersed signal in the cells in the absence of the partner whereas VirD4-CFP formed bright foci at the poles in the majority of the cells in the presence and absence of KfrC. Notably, KfrC-YFP also formed foci close to the poles when VirD4-CFP was present in the cells, implicating that its polar positioning depended on VirD4.

As it was mentioned above (Figure 3A), the closest homolog of KfrCRA3 is KfrCRK2 of the IncPα plasmid [37]. However, the similarity concerns only the first 240 residues, which are lost from IncPβ representatives, e.g., KfrC of the R751 plasmid [38]. The 115-amino-acid polypeptide from the C-terminus of KfrCRA3 has no homologs in the database. If the acquirement of a new C-terminus by KfrCRA3 was the evolutionary way to accomplish a domain of interaction with VirD4, then both KfrC variants from IncPα and IncPβ plasmids (KfrR751 is homologous to the C-end of KfrCRK2 that is not present in KfrCRA3, Figure 3A) should be deprived of this ability. Hence, the kfrC genes of RK2 and R751 were cloned into the BACTH system along with the cognate coupling proteins TraGs, homologs of VirD4RA3, and analyzed for interactions (Figure 6F). No interactions have been detected among KfrC and TraG proteins of RK2 and R751.

2.6. The Interactions between the KfrCRA3 Partners Involved in Two Modes of Plasmid Spreading

Previously, it was established that partitioning proteins KorBRA3 and IncCRA3 dimerize and interact with each other [17] and that an alpha-helical, filamentous KfrA protein forms a complex with KfrC and interacts with KorB and IncC [18]. KfrC also heterodimerized with KorBRA3. Here, we showed interactions of KfrC with VirD4, the coupling protein in the conjugative transfer process, as well as with VirB4, an ATPase participating in the inner membrane part of the transferosome. Using the BACTH system, we analyzed the interactions between the RA3 relaxosome proteins, the VirD4 protein, and the Kfr proteins. The RA3 relaxosome consists of the NIC relaxase and oriT [27]. Additionally, it was shown that MobC acts as an auxiliary protein potentiating the NIC cleavage at oriT [27]. NIC also collaborated with the MobC in the autoregulation of the mobC-nic operon [23].

After cloning of the nic and the mobC into the the BACTH vectors, we demonstrated that VirD4 interacted with neither NIC nor MobC and only weakly self-associated (Figure 6E). MobC, the autorepressor and the auxiliary transfer protein [23], strongly dimerized, but MobC–NIC interactions and dimerization of NIC were not detected. The presence of oriT did not facilitate interactions between the relaxase and the coupling protein that was observed in other conjugation systems [39,40,41]. Besides the KfrC–VirD4 interactions (Figure 6A), no associations of KfrA or KfrC and the relaxosome proteins were shown (Figure 6E). Altogether, these results suggest that the BACTH system is not the perfect tool to look at the formation of multicomponent complexes, especially if some of them act as the flexible/dynamic linkers. The interactions between the RA3 relaxosome components ought to be analyzed via other methods.

2.7. The Interplay between the Active Partitioning and the Conjugative Transfer Processes

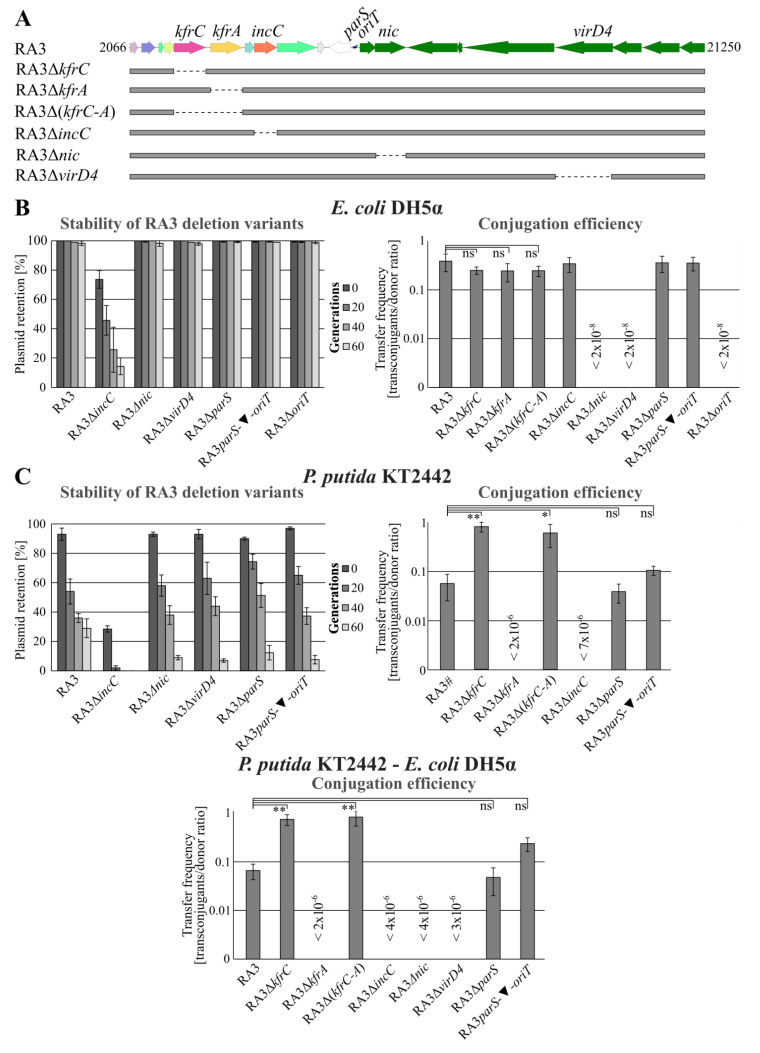

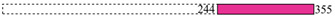

The discovered interactions of KfrC, probably when complexed with KfrA, with KorB of the segrosome and the coupling protein VirD4 (or transferosome) raised a hypothesis of an interplay between mutually exclusive processes of vertical and horizontal spreading. The eight RA3 variants deprived of kfrA, kfrC, kfrC-kfrA, incC, virD4, nic, and two cis-acting sites, parS or oriT (as presented in Figure 1C and Figure 7A), were constructed and used in the conjugation and stability experiments.

Figure 7.

Role of KfrCRA3 in the plasmid stable maintenance and the efficiency of the conjugative transfer in E. coli and P. putida hosts. (A) Schematic presentation of RA3 variants used in these experiments. Other tested RA3 variants, RA3ΔparS, RA3ΔoriT, and RA3 parS oriT insertional mutant, are depicted in Figure 1C. (B) Retention of RA3 variants in E. coli DH5α strain and their conjugative transfer frequencies between E. coli strains. Segregation experiments were conducted for 60 generations without selection. Quantitative conjugation was done on the nitrocellulose filters and the transfer frequency was indicated on the semilogarithmic scale as the number of transconjugants per donor cell. Data represent mean ± SD from three biological replicates. The differences in the frequency of the conjugative transfer between RA3 variants are not statistically significant (ns) (p-value > 0.05 in Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance). (C) Retention of RA3 variants in P. putida KT2442 strain and their conjugative transfer frequency in the intra- and the interspecies spreading. RA3# plasmid contains Kmr cassette within integron. Introduction of RA3 conjugation-deficient variants to P. putida was done with the use of the helper strain E. coli DH5α carrying pJSB1.24 with the RA3 conjugative transfer module and korC gene. Data represent mean ± SD from three biological replicates. The statistically significant differences between WT RA3 and its variants with p-value ≤ 0.005 or < 0.05 (based on Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test of multiple comparisons) are indicated by two or one asterisk, respectively.

The additional RA3 construct had an insertion of a 1 kb fragment separating parS and oriT motifs (parS-▼-oriT) to see whether close proximity of these motifs in the RA3 genome interferes with the binding of the segrosome and relaxosome complexes (Figure 1C).

All nine derivatives together with WT RA3 (control), were introduced into the E. coli DH5α strain and tested for stability and frequency of conjugative transfer into the DH5α Rifr recipient. Stability assays showed that all tested deletion mutants except ΔincC were stably maintained in E. coli for 60 generations (Figure 7B and Figure 2A for kfr deletion mutants). Unexpectedly, the deletion of the parS region (seemingly the important cis-acting site in the active partition process [24]) did not influence the RA3 stability in E. coli. The presence of two additional KorB binding sites in the RA3 genome offers a plausible explanation of this result. Among nine RA3 deletion variants, only mutants virD4, nic, and ΔoriT mutants were significantly impaired in the conjugative transfer between the E. coli strains. Hence, no interference between conjugative transfer processes and stability functions was noticed in this host.

Different results were obtained during the analyses of the set of RA3 mutants in the P. putida KT2442 strain (Figure 7C and Figure 2C, inset). WT RA3 was less stably maintained in the P. putida host than in E. coli being retained after 60 generations of growth without selection only in 30% of cells. Lack of any of Kfrs strongly destabilized RA3 and led to the loss of plasmid in 80% to 100% of cells after 20 generations. Lack of incC also caused a loss of the RA3 deletion derivative after 20 generations. The most spectacular results were observed when the RA3 variants were tested in the conjugation experiments. In the absence of KfrA, the RA3 conjugation frequency between P. putida strains decreased by more than six orders of magnitude whereas the lack of KfrC alone or both Kfrs had an opposite effect, increasing the conjugation frequency by approximately 10-fold. Separation of parS and oriT via kanamycin cassette led to a statistically insignificant increase in the conjugation frequency. Finally, deletion of incC had a detrimental effect not only on plasmid stability but also the frequency of the horizontal transfer and/or plasmid establishment. Similar results were obtained during interspecies conjugation between P. putida strains used as donors and the E. coli DH5α strain as a recipient (bottom diagram in Figure 7C).

3. Discussion

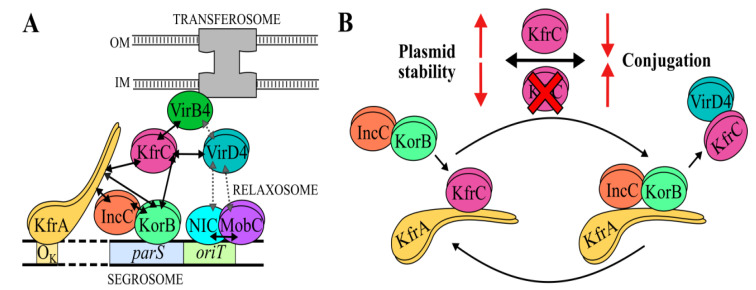

Studies on the alpha-helical KfrA protein [16] have suggested its role in the stability of IncP plasmids, together with KfrC, is encoded in the same operon [13]. It was shown that the KfrA of R751 interacted with KfrC using a linker, KfrB [13]. In the RA3 plasmid of the IncU group, KfrC could interact directly not only with KfrA but also with KorB (Figure 8A), one of the components of the active partition system [18]. It was shown that KfrARA3 had the ability to form filaments [29] and interacted with both components of the partition apparatus, KorB and IncC. Hence, the accessory role of a scaffold built of Kfr complexes in the segregation of plasmid molecules to the progeny cells in a species-dependent manner was envisaged [18].

Figure 8.

Interactions between the Kfr proteins, segrosome, relaxoxosome, and transferosome in RA3. (A) Model of the complexes built at parS-oriT region of RA3. (B) KfrC acts as a switch between the horizontal and the vertical spreading of RA3 plasmid. The established protein–protein interactions (this work, [17,18]) are indicated by solid arrows. Putative interactions are depicted by the broken-line arrows.

The studies on kfrA and kfrC conducted on the stability module cloned into a highly unstable heterologous replicon [18,26] proved an important role of both proteins in the stable maintenance of the test plasmid in the E. coli, P. putida, A. tumefaciens, and C. necator strains. It was also shown that the KfrA DNA binding activity was vital to support plasmid stability [18]. Here, we decided to look at the effects of the deletions of kfrC, kfrA operon, or both (ΔkfrC-kfrA) in the RA3 background. In E. coli, the presence of any of these three derivatives led to the growth retardation, a slight increase in the generation time, and, in the case of RA3ΔkfrC, to the formation of filamentous cells. Despite these changes, all three variants were very stably maintained for at least 60 generations of growth without selection in clear contrast to the results of the test plasmid pESB36.44 (ΔkfrA) based on the heterologous RK2 minireplicon [18,26]. It demonstrated that in E. coli, in the context of the whole RA3 genome, the Kfr proteins did not play vital roles in the segregation of RA3. The very active conjugation system or easily adaptable RA3 replication system may compensate for the difference the lack of Kfr proteins imposes on the plasmid retention. In other tested hosts, e.g., P. putida, A. veronii, or C. necator, the effects of Kfr deficiencies were much stronger not only on the growth rate but also on the stable maintenance and clearly were species-specific (Figure 2).

KfrC belongs to the alpha-helical proteins with two-domain structures. The N-terminal part with phosphoribosyltransferase (PRT)-type I domain (Pfam: PF00156) is responsible for its “toxicity” when in excess. The results of screening of E. coli and A. veronii genomic libraries strongly suggested that KfrCRA3 was part of the phosphometabolomes of the hosts. The metabolic role of KfrC in various hosts is under investigation. This initial libraries’ screening also revealed the interactions between KfrCRA3 and the various membrane-bound proteins, implicating at least temporal positioning of KfrC close to a cellular membrane. Its polar cell localization in the presence of VirD4 was demonstrated (Figure 6D).

The KfrCRA3 C-terminal domain of 112 residues seems to be multifaceted. Its involvement in the dimerization, in the interactions with the partition protein KorB, and the coupling protein VirD4 opens new possibilities of the KfrC role in the RA3 plasmid biology (Figure 8A).

The RA3 deletion derivatives in kfr genes were not only less stable than WT RA3 in P. putida but also demonstrated the altered conjugation frequency between P. putida strains and P.-putida- E. coli strains. The effect was very strong when KT2442 RA3(ΔkfrA) was used as a donor. The conjugation frequency was more than six orders of magnitude lower than for WT RA3. Significantly, the removal of kfrC or kfrA-kfrC stimulated 10-fold the transfer frequency of the analyzed RA3 derivatives in comparison to the WT RA3 (Figure 7C), implicating a negative role of KfrC in the conjugative transfer efficiency and a requirement for KfrA only when KfrC was present. The insignificant variation in the number of transconjugants of RA3 with the parS and oriT sites separated by a 1 kb insertion suggested that the closeness of these two important cis-acting sites in the WT RA3 did not affect the transfer initiation process despite the fact that they had to accommodate next to each other two large protein complexes, segrosome and relaxosome.

Our previous studies on the RA3 relaxosome demonstrated an auxiliary role of the MobC protein. The MobC binding to OM in the mobCp had not only an autoregulatory role in the mobC-nic expression but it increased the nicking activity of NIC more than 1000-fold and in turn stimulated the transfer [23]. Reciprocally, the interaction of NIC with its binding site (IR3, Figure 1C) enhanced the MobC repressor action of mobCp [27]. The BACTH studies concerning intermolecular interactions within the RA3 relaxosome demonstrated neither NIC interactions with MobC nor with VirD4 (Figure 6E). The MobC dimerized efficiently but did not associate with VirD4 as it was observed for the auxiliary proteins in other conjugative systems [39,40,41]. Other experimental approaches are needed to elucidate the structure of the RA3 relaxosome. Hence, lack of the observed interactions between Kfr and relaxosome proteins does not exclude the possibility of their occurrence in the cells.

In this study, a new VirD4RA3 partner was found, the KfrC protein that somehow linked the conjugation with the active partition process not only by interactions with VirD4 but also VirB4 ATPase (Figure 8A), an important energy supplier for the transferosome [36]. VirD4s have multidomain structures [39] with (i) an N-terminal transmembrane domain responsible for the spatial positioning and interactions with the transferosome inner membrane complex (IMC), (ii) a cytoplasm facing the middle part with the ATPase domain (energy supplier), and (iii) a seven-helix motif called the all-α domain (AAD) responsible for recruiting and docking a relaxase with the covalently bound transfer DNA. The variable-length (iv) cytosolic C-terminal domains are typically enriched in the acidic residues [42,43] and are assumed to evolve to expand a range of protein effectors being transferred by T4SS as well as to control presentation of effectors to the system [39]. Notably, according to the BACTH library screening, there are two fragments of VirD4RA3 interacting with KfrCRA3: the internal hydrophobic polypeptide VirD4244–283 and the C-terminal 47 residues. Finding that VirD4 of RA3 was capable of interactions with KfrCRA3, whereas TraGs, VirD4 homologs of IncP plasmids, did not interact with the cognate KfrCs, correlated with VirD4RA3 having an extended highly acidic C-terminus in comparison to the IncP homologs (Figure S3). On the other hand, KfrCRA3 also differs from the IncP homologs in its C-terminal part of the 115-residue polypeptide that exhibits the high content of the polar residues (45%). This fragment, unique for KfrCRA3, (Figure 3A) was shown to be involved in the dimerization and binding of both KorB and VirD4.

Previously, we showed that the conjugative transfer process of RA3 was subjected to complex multilayered control mechanisms. The three conjugative transfer operons were strongly repressed by the global and the local repressors at least in E. coli. The mobC-nic operon is autoregulated by MobC and NIC [27]. The longest operon orf33-traC3, encoding most of the transferosome components, is regulated by the global regulator KorC in cooperation with the so far unidentified product of the transfer module [25]. The cross-talk between stability and conjugative functions is also potentiated by the fact that in this long transcriptional unit there is the internal promoter, orf23p, negatively controlled by the second global regulator, active partition protein KorB, bound at the distant OB [17]. Divergently oriented, orf34p of the tricistronic operon orf34-orf36, is very efficiently repressed by KorC. Here, we showed that at the top of this transcriptional regulation there are protein–protein interactions, KfrC–VirD4, that decrease the efficiency of the conjugative transfer process. Our transcriptional studies conducted in different hosts showed that the highest level of gene expression in the stability module was detected for the partition operon incC-korB-orf11 with the korC-kfrC operon being the second in line [26]. Constitutive expression of the korC-kfrC operon at the significant level may determine their importance in the control of the conjugative transfer besides its important role in the plasmid partition process.

Our model implicates that KfrC may improve the plasmid segregation by bringing the segrosome complex to the filamentous KfrA scaffold due to its ability to bind KorB and KfrA. KorB may outcompete KfrC for the KfrA binding since both proteins interact preferentially with the KfrA54–177 region [18]. The release of KfrC from the KfrA filamentous network allows it to interact with VirD4 and, in effect, to interfere with the efficient transfer of relaxosome to the transferosome at least in the P. putida cells. Significantly, the C-terminal dimerization domain of KfrC is involved in the interactions not only with KorB (segrosome) but also with VirD4, so it may provide a spatiotemporal switch between two processes responsible for the various modes of RA3 spreading, vertical and horizontal (Figure 8B). The strength of KorB–KfrC–VirD4 interactions may also be species-specific due to additional factors involved.

The interplay of two aspects of a plasmid physiology, stable maintenance and the conjugative expansion, was brought to the attention of researchers via the analysis of an atypical plasmid stabilization system, stbABC, of the conjugative BHR plasmid R388 of the IncW incompatibility group [44]. Deletion of the stbA encoding a DNA binding protein led to the plasmid instability and the increased transfer frequency. Oppositely, the deletion of an ATPase encoding stbB did not affect the plasmid maintenance, but it abolished conjugative transfer. It was postulated that the defects in both plasmid maintenance and transfer were a consequence of changes in the positioning of the stb plasmid mutants in the cells [44].

The correlation between the active partition and the conjugative transfer processes was also postulated for the low-copy-number conjugative R1 plasmid of the IncFII incompatibility group [45]. R1 is a narrow-host-range plasmid with the type II active partitioning system [7]. It was shown that ParM, an actin-like ATPase, interacted with TraD, a homolog of VirD4 (the coupling protein), TraC (an ATPase, a homolog of VirB4), and TraI (the relaxase). TraI also interacted with the second component of the partition system, ParR, a DNA binding protein. Importantly ParM and TraI mutually increased their enzymatic activities of NTPase and relaxase, respectively. Thus, in the case of R1, the functional collaboration of Par components with the relaxosome/transferosome complex appeared optimal for its vertical and lateral modes of dissemination.

These examples and our work indicate the importance of the integration of plasmid maintenance function with the conjugation process, although it may differ in the mechanisms, e.g., cooperation and coordination as observed for R1 and R388 or the partial exclusion as in the RA3 system. The requirements for adaptation to an environment and a host range may drive these evolutionary changes.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

The E. coli strains used were: DH5α [F−(ϕ80dlacZΔM15) recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 relA1 deoR Δ(lacZYA-argF)U196], BL21(DE3) [F− ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3)] (Novagen), BTH101 [F− cya-99 araD139 galE15 galK16 rpsL1 (Smr) hsdR2 mcrA1 mcrB1] [34], BW25113 [lacIq rrnBT14 ΔlacZWJ16 hsdR514 ΔaraBA-DAH33 ΔrhaBADLD78] [30], and S17-1 [recA pro hsdR RP4-2-Tc::Mu-Km::Tn7] [46]. The rifampin-resistant mutants of A. tumefaciens LBA1010R [47] and P. aminovorans JCM7685 [48] were kindly provided by D. Bartosik, University of Warsaw, Poland, C. necator JMP228 was kindly provided by K. Smalla, Julius Kühn-Institut, Federal Research Institute for Cultivated Plants, Germany, and P. putida KT2442 was kindly provided by C.M. Thomas, University of Birmingham, United Kingdom. The spontaneous Rifr mutant of A. veronii (kindly provided by M. Gniadkowski as an environmental A. hydrophila strain) was isolated in the laboratory.

Bacteria were generally grown in L broth [49] or on L agar (L broth with 1.5% w/v agar) at 37 °C or at 28 °C (A. tumefaciens, C. necator, P. aminovorans, P. putida, and E. coli BTH101). MacConkey agar base (BD Difco) or M9 medium supplemented with 1% maltose were used in the bacterial adenylate cyclase-based two-hybrid system (BACTH) and in the library screening, respectively [50]. If needed, media were supplemented with X-gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) (40 µg mL−1) for blue/white screening, IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) for tacp induction or appropriate antibiotic(s): chloramphenicol (10 µg mL−1 for E. coli, 50 µg mL−1 for A. tumefaciens, 150 µg mL−1 for C. necator), kanamycin (50 µg mL−1 for E. coli, 20 µg mL−1 for P. aminovorans and P. putida), tetracycline (50 μg mL−1 for P. putida, 10 μg mL−1 for other strains), or penicillin (sodium salt) (150 μg mL−1 in liquid media and 300 μg mL−1 for agar plates), rifampin (100 µg mL−1).

4.2. Plasmid DNA Isolation, Analysis, DNA Amplification, and Manipulation

Plasmid DNA was isolated and manipulated using standard methods [50] or kits using manufacturers’ instructions. All new plasmid constructs were verified by DNA sequencing at the Laboratory of DNA Sequencing and Oligonucleotide Synthesis, Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics Polish Academy of Science. The list of plasmids used and constructed in this study is presented in Table 3. Oligonucleotides are listed in Table 4.

Table 3.

Plasmids used in this study.

| Plasmids Provided by Others | |

|---|---|

| Designation | Relevant Features or Description |

| pABB19 | oriMB1, Apr, transcriptional terminator Tpro/Tlyz P1 [51] |

| pABB28.2 | pET28a with his-tag replaced by flag-tag [52] |

| pAKB2.55 | pGBT30 with kfrC without a stop codon (IBB) a |

| pAKB2.70 | pGBT30 with kfrCRA3-yfp (IBB) a |

| pAKB7.5 | oriMB1, Kmr, parS-oriTRA3 (RA3 coordinates 9397–9854 nt) [24] |

| pAKB16.50 | pLKB4 cyaT18-korBRA3 [17] |

| pAKB16.50N | pKGB4 korBRA3-cyaT18 [17] |

| pAMB8 | pBBR1MCS-3 modified in tetM to remove EcoRI site (IBB) a |

| pBBR1MCS | IncA/C, Cmr, BHR cloning vector [53] |

| pBBR1MCS-2 | IncA/C, Kmr BHR cloning vector [54] |

| pBGS18 | oriMB1, Kmr, cloning vector [55] |

| pESB5.58 | pGBT30 with tacp-kfrA [18] |

| pET28a | oriMB1, Kmr, T7p, lacO, His6-tag, T7 tag (Novagen) |

| pET28mod | pET28a derivative, T7 tag removed [56] |

| pGBT30 | oriVMB1, Apr, lacIq, tacp expression vector [57] |

| pJSB8.5.2 | pLKB4 cyaT18-virD4 (IBB) a |

| pJSB9.5.1 | pKGB4 virD4-cyaT18 (IBB) a |

| pJSB10.5.2 | pLKB2 cyaT25-virD4 (IBB) a |

| pJSB11.5.1 | pKGB5 virD4-cyaT25 (IBB) a |

| pKAB20 | pUC19 derivative with flag-mcsb-his6; allows in-frame attachment of flag to 5′ and/or his6 to the 3′ of a gene [58] |

| pKAB28 | pET28mod with deletion of his6-tag and EcoRI site adjacent to RBS [57] |

| pKAB28.7 | pET28mod derivative with his6- mcsb [58] |

| pKD13 | template plasmid for gene disruption [30] |

| pKD46 | oriR101, araBp-gam-bet-exo, repA101(ts), Apr, lambda Red recombinase expression plasmid [30] |

| pKGB4 | oriColE1, pUT18 with modified mcs, lacp- mcsb -cyaT18, Apr (IBB) a |

| pKGB5 | orip15, pKNT25 with modified mcs, lacp- mcsb -cyaT25, Kmr (IBB) a |

| pKT25-zip | pKT25 derivative encoding CyaT25 in translational fusion with leucine zipper of GCN4 [34] |

| pLKB2 | orip15, pKT25 with modified mcs, lacp-cyaT25- mcsb, Kmr [59] |

| pLKB4 | oriColE1, pUT18C with modified mcs, lacp-cyaT18- mcsb, Apr [59] |

| pMRA1.3 | pLKB4 with cyaT18-kfrCR751 (IBB) a |

| pMRB2.3 | pKGB4 with kfrCR751-cyaT18 (IBB) a |

| pMRB3.3 | pLKB2 with cyaT25-kfrCR751 (IBB) a |

| pMRB4.3 | pKGB5 with kfrCR751-cyaT25 (IBB) a |

| pOMB3.104 | pUC18 derivative with parS P1 prophage (IBB) a |

| pOMB4.13 | pLKB4 with cyaAT18-kfrA [18] |

| pOMB4.15 | pLKB4 with cyaAT18-kfrC [18] |

| pOMB5.13 | pLKB2 with cyaAT25-kfA [18] |

| pOMB5.15 | pLKB2 with cyaAT25-kfrC [18] |

| pOMB6.14 | pKGB4 with kfrA-cyaAT18 [18] |

| pOMB6.16.1 | pKGB4 with kfrC-cyaAT18 [18] |

| pOMB7.14 | pKGB5 with kfrA-cyaAT25 [18] |

| pOMB7.16.1 | pKGB5 with kfrC-cyaAT25 [18] |

| pOMB9.80 | pGBT30 with kfrARA3-cfp (IBB) a |

| pUC18 | oriMB1, Apr, cloning vector [60] |

| pUT18C-zip | pUT18C derivative encoding CyaT18 in translational fusion with leucine zipper of GCN4 [34] |

| R751TcR | IncPβ (IncP-1β) c, Tcr-derivative of R751 [38] |

| RA3 | IncU (IncP-6) c, Cmr, Smr, Sur (F. Hayes) |

| RK2 | IncPα (IncP-1α) c, Apr, Kmr, Tcr (C.M. Thomas) |

| Plasmids Constructed during This Work | |

| Designation | Relevant Features or Description |

| pESB5.88 | pGBT30 with tacp-kfrC; annealed oligonucleotides 28 and 29 inserted between Xba-SalI of pAKB2.55 |

| pESB5.90 | pGBT30 with tacp-kfrC without a stop codon; annealed oligonucleotides 6 and 7 inserted between Xba-SalI of pAKB2.55 |

| pESB10 | pBBR1MCS-2 lacIq tacp with transcriptional terminator T1/T2rrnB; PCR product obtained with primers 36 and 37 on E. coli genomic DNA inserted as XhoI-KpnI fragment between SalI-KpnI sites |

| pESB11 | pOMB12.0 derivative with transcriptional terminator T1/T2rrnB; PCR fragment obtained with primers 36 and 37 on E. coli genomic DNA inserted between XhoI-KpnI sites |

| pESB11.58 | pESB11 with tacp-kfrA; EcoRI-SalI fragment from pESB5.58 inserted between EcoRI-XhoI sites |

| pESB15 | pET28a with annealed oligonucleotides 30 and 31 inserted between NcoI and BamHI sites |

| pESB15.90 | pESB15 with kfrC-his6; EcoRI-HindIII fragment from pESB5.90 |

| pJSB1.4 | pBGS18 with the mobCp-mobC-nic; PCR fragment obtained with primers 26 and 5 on RA3 template inserted between EcoR-SalI sites (RA3 coordinates 9437–11355 nt) |

| pJSB1.5.2 | pBGS18 with virD4; PCR fragment obtained with primers 44 and 45 on RA3 template cloned between the BamHI-KpnI sites (RA3 coordinates 18230–16305 nt) |

| pJSB1.8 | pBGS18 with TraRA3; pJSB1.4 with SmaI-SalI fragment of RA3 plasmid (RA3 coordinates 10733–22925 nt) |

| pJSB1.24 | pBGS18 with TraRA3-korCp-korC; PCR fragment korCp-korC obtained with primers 2 and 3 (RA3 coordinates 3093–3705) inserted into pJSB1.8 |

| pJSB8.1 | pLKB4 with cyaT18-mobC; PCR fragment obtained with primers 22 and 23, cloned between the EcoRI-HincII sites (RA3 coordinates 9837–10455 nt) |

| pJSB8.3 | pLKB4 with cyaT18-nic; PCR fragment obtained with primers 25 and 26 cloned between the EcoRI-HincII sites (RA3 coordinates 10360–11355 nt) |

| pJSB8.5.2 | pLKB4 with cyaT18-virD4; fragment BamHI-KpnI from pJSB1.5.2 cloned into pLKB4 |

| pJSB8.35 | pLKB4 with cyaT18-mobC-oriTRA3; SmaI-HincII fragment of pAKB7.5 carrying parS-oriT cloned into PvuII site of pJSB8.1 |

| pJSB9.1.1 | pKGB4 with mobC-cyaT18; PCR fragment obtained with primers 22 and 24 cloned between EcoRI-SacI sites, (RA3 coordinates 9837–10364 nt) |

| pJSB9.5.1 | pKGB4 with virD4-cyaT18; PCR fragment obtained with primers 44 and 46 cloned between BamHI-SacI sites (RA3 coordinates 18230–16308 nt) |

| pJSB10.1 | pLKB2 with cyaT25-mobC; PCR fragment EcoRI-HincII obtained with primers 22 and 23, cloned between the EcoRI-SmaI sites (RA3 coordinates 9837–10455 nt) |

| pJSB10.3 | pLKB2 with cyaT25-nic; PCR fragment EcoRI-HincII obtained with primers 25 and 26 cloned between EcoRI-SmaI sites (RA3 coordinates10360–11355 nt) |

| pJSB10.5.2 | pLKB2 with cyaT25-virD4; PCR fragment obtained with primers 44 and 45 cloned between BamHI-KpnI sites (RA3 coordinates18230–16305 nt) |

| pJSB11.1 | pKGB5 with mobC-cyaT25; PCR fragment obtained with primers 22 and 24 cloned between EcoRI-SacI sites (RA3 coordinates 9837–10364 nt) |

| pJSB11.3 | pKGB5 with nic-cyaT25; PCR fragment obtained with primers 25 and 27 cloned between EcoRI-SacI sites (RA3 coordinates 10360–11352 nt) |

| pJSB11.5.1 | pKGB5 with virD4-cyaT25; PCR fragment obtained with primers 44 and 46 cloned between BamHI-SacI sites (RA3 coordinates 18230–16308 nt) |

| pOMB1.17 | pBGS18 with kfrC1–249; PCR product amplified on RA3 template with primers 8 and 9 inserted between EcoRI-SalI sites (RA3 coordinates: 3692–4438) |

| pOMB1.18 | pBGS18 with kfrC244–355; PCR product amplified on RA3 template with primers 10 and 11 inserted between EcoRI-SalI sites (RA3 coordinates: 4421–4756) |

| pOMB1.42 | pBGS18 with virD4434–641; EcoRI-BamHI fragment from pOMB4.42 |

| pOMB1.51 | pBGS18 with virD4434–641 kfrC; PCR product amplified on RA3 template with primers 14 and 18 inserted as BglII-SalI fragment between BamHI-SalI sites of pOMB1.42 (RA3 coordinates: 3686–4756) |

| pOMB1.74 | pBGS18 virD4-cfp; BamHI-HindIII fragment from pOMB9.80 with overhangs filled in using Klenow fragment of PolI inserted within EcoICRI site of pJSB1.5.2 |

| pOMB2.0 | pKAB20 derivative with Ecl136II restriction site inserted between MunI and HindIII sites (annealed oligonucleotides 33 and 34) |

| pOMB2.0.28 | pUC19 with kfrC244–355-his6; EcoRI-SmaI fragment from pOMB1.18 inserted in EcoRI-Ecl136II sites of pOMB2.0 |

| pOMB2.49 | pUC19 with flag-virD4; PCR product amplified on RA3 template with primers 4 and 49 inserted between MunI-HindIII sites of pKAB20 (RA3 coordinates: 18230–16305) |

| pOMB2.50 | pUC19 with flag-vird4434–641; EcoRI-SalI fragment from pOMB1.42 inserted between MunI-SalI sites of pKAB20 |

| pOMB2.52 | pUC19 with flag-virD4434–641 kfrC-his6; EcoRI-SalI fragment from pOMB1.51 inserted between MunI-XhoI sites of pKAB20 |

| pOMB2.74 | pUC19 virD4-cfp; PCR product amplified on pOMB1.74 template with primers 1 and 49 inserted as MunI-SmaI sites of pOMB2.0 |

| pOMB4.0 | pLKB4 derivative with I-SceI restriction site inserted into KpnI site (annealed oligonucleotides 20 and 21) |

| pOMB4.17 | pLKB4 with cyaT18-kfrC1–249; EcoRI-SmaI fragment from pOMB1.17 |

| pOMB4.18 | pLKB4 with cyaT18-kfrC244–355; EcoRI-SmaI fragment from pOMB1.18 |

| pOMB4.34 | pLKB4 with cyaT18-traGR751; PCR product amplified on R751 template with primers 38 and 39 inserted as EcoRI-KpnI fragment (R751 coordinates: 48800–46887) |

| pOMB4.36 | pLKB4 with cyaT18-kfrCRK2; PCR product amplified on RK2 template with primers 15 and 16 inserted as EcoRI-KpnI fragment (RK2 coordinates: 54424–53079) |

| pOMB4.38 | pLKB4 with cyaT18-traGRK2; PCR product amplified on RK2 template with primers 40 and 41 inserted as EcoRI-KpnI fragment (RK2 coordinates: 48495–46588) |

| pOMB4.42 | pLKB4 with cyaT18-virD4434–641; PCR product amplified on RA3 template with primers 47 and 48 inserted between EcoRI-BamHI sites (RA3 coordinates: 16931–16305) |

| pOMB5.17 | pLKB2 with cyaT25-kfrC1–249; EcoRI-SmaI fragment from pOMB1.17 |

| pOMB5.18 | pLKB2 with cyaT25-kfrC244–355; EcoRI-SmaI fragment from pOMB1.18 |

| pOMB5.34 | pLKB2 with cyaT25-traGR751; EcoRI-KpnI fragment from pOMB4.34 |

| pOMB5.36 | pLKB2 with cyaT25-kfrCRK2; EcoRI-KpnI fragment from pOMB4.36 |

| pOMB5.38 | pLKB2 with cyaT25-traGRK2; EcoRI-KpnI fragment from pOMB4.38 |

| pOMB6.17 | pKGB4 with kfrC1–249-cyaT18; EcoRI-SmaI fragment from pOMB1.17 |

| pOMB6.18 | pKGB4 with kfrC244–355-cyaT18; EcoRI-SmaI fragment from pOMB1.18 |

| pOMB6.35 | pKGB4 with traGR751-cyaT18; PCR product amplified on R751 template with primers 38 and 43 inserted as EcoRI-SmaI fragment (R751 coordinates: 48800–46890) |

| pOMB6.37 | pKGB4 with kfrCRK2-cyaT18; PCR product amplified on RK2 template with primers 15 and 17 inserted as EcoRI-SmaI fragment (RK2 coordinates: 54424–53082) |

| pOMB6.39 | pKGB4 with traGRK2-cyaT18; PCR product amplified on RK2 template with primers 40 and 42 inserted as EcoRI-SmaI fragment (RK2 coordinates: 48495–46591) |

| pOMB7.17 | pKGB5 with kfrC1–249-cyaT25; EcoRI-SmaI fragment from pOMB1.17 |

| pOMB7.18 | pKGB5 with kfrC244–355-cyaT25; EcoRI-SmaI fragment from pOMB1.18 |

| pOMB7.35 | pKGB5 with traGR751-cyaT25; EcoRI-SmaI fragment from pOMB6.35 |

| pOMB7.37 | pKGB5 with kfrCRK2-cyaT25; EcoRI-SmaI fragment from pOMB6.37 |

| pOMB7.39 | pKGB5 with traGRK2-cyaT25; EcoRI-SmaI fragment from pOMB6.39 |

| pOMB8.28 | pET28mod with kfrC244–355-his6; pKAB28 derivative with EcoRI-SalI fragment from pOMB2.0.28 |

| pOMB8.49 | pET28mod with flag-virD4; MunI-HindIII fragment from pOMB2.49 inserted between EcoRI-HindIII sites of pKAB28 |

| pOMB8.50 | pET28mod with flag-virD4434–641; pKAB28 derivative with EcoRI-SalI fragment from pOMB2.50 |

| pOMB8.52 | pET28mod with flag-virD4434–641 kfrC-his6; pKAB28 derivative with EcoRI-SalI fragment from pOMB2.52 |

| pOMB9.18 | pGBT30 with tacp-kfrC244–355; EcoRI-SalI fragment from pOMB1.18 |

| pOMB9.29 | pGBT30 with tacp-kfrC-his6; PCR product amplified on the pESB15.90 template with primers 19 and 35 inserted between XbaI-SalI sites of pESB5.88 |

| pOMB9.31 | pGBT30 with tacp-kfrC*; two-stage PCR was used for KfrC site-directed mutagenesis, described in detail in Metods, PCR final product was inserted between XbaI-SalI sites |

| pOMB12.0 | pOMB12.30 derivative with transcriptional terminator Tpro/Tlyz P1; PCR product amplified on pABB19 as a template with primers 50 and 51 inserted as EcoRI-SalI fragment between EcoRI-XhoI sites |

| pOMB12.15 | pESB11 with tacp-kfrC; EcoRI-SalI fragment from pESB5.88 inserted between EcoRI-XhoI sites |

| pOMB12.30 | pBBR1MCS-3 lacIq tacp; pAMB8 derivative with EcoRI-PstI fragment from pGBT30 |

| pOMB12.74 | pBBR1MCS-2 virD4-cfp; pESB10 derivative with MunI-SmaI fragment from pOMB2.74 inserted between EcoRI-SmaI sites |

| RA3ΔincC | incC gene replaced by Kmr cassette amplified on pKD13 template with primers 52 and 53 (coordinates of deletion: 6356–7080) |

| RA3Δnic | nic gene replaced by Kmr cassette amplified on pKD13 template with primers 54 and 55 (coordinates of deletion: 10380–11352) |

| RA3ΔvirD4 | virD4 replaced by Kmr cassette amplified on pKD13 template with primers 56 and 57 (coordinates of deletion: 18195–16314) |

| RA3ΔparS | parS site replaced by Kmr cassette amplified on pKD13 template with primers 58 and 59 (coordinates of deletion: 9707–9722) |

| RA3ΔoriT | oriT site replaced by Kmr cassette amplified on pKD13 template with primers 60 and 61 (coordinates of deletion: 9747–9756) |

| RA3parS▼oriT | Kmr cassette amplified on pKD13 template with primers 59 and 62 and inserted between parS and oriT sites (coordinates of insertion: 9722/9723) |

| RA3ΔkfrA | kfrA replaced by Kmr cassette amplified on pKD13 template with primers 63 and 64 (coordinates of deletion: 4892–5935) |

| RA3ΔkfrC | kfrC replaced by Kmr cassette amplified on pKD13 template with primers 65 and 66 (coordinates of deletion: 3695–4738) |

| RA3Δ(kfrC-A) | kfrC-kfrA replaced by Kmr cassette amplified on pKD13 template with primers 65 and 64 (coordinates of deletion: 3695–5935) |

| RA3# | parSP1-Kmr cassette inserted within integron at position 38,663 of RA3 genome |

a—Institute of Biochemistry & Biophysics collection; b—mcs, multiple-cloning site modified; c—in brackets plasmid incompatibility groups in Pseudomonas spp.

Table 4.

Oligonucleotides used in this study.

| No | Designation | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | CFPSmSaP | gccccggGGTCGACTTACTTGTACAGCTCG |

| 2 | CkorCD | cgacatgtTTATGTTCGGTCATGGTTTC |

| 3 | CkorCG | gcgcatgcCTTAAAGGAGGTGCATAGGT |

| 4 | FLAGVirDR | ccaagcttTTATGCCGCTTCAGCCAAGC |

| 5 | kasmob1 | cggaattcacatgtTTCTCGTTGGAGGGTGATCA |

| 6 | KFRCBSD | tcgacaagcttCCGCT |

| 7 | KFRCBSG | CTAGAGCGGaagcttg |

| 8 | kfrCFL | gcaagctttggaattCATGACCGAACATAAGGCCGA |

| 9 | kfrCIR | cggtcgacttacccgggAGCTCCGCTTTTGCCCATTC |

| 10 | kfrCIIF | cggaattcATGGGCAAAAGCGGAGCTGA |

| 11 | kfrCIIR | cggtcgacTTAcccgggCCGCTCTAGATCGTCTTCAT |

| 12 | kfrCmutF | TGTCGcgGccgCGCTGGCGATGGGCG |

| 13 | kfrCmutR | CCAGCGcggCcgCGACAATCAGATAAGGCTGGTCA |

| 14 | kfrCrbsF | cggaattcagatctaaggagGAAACCATGACCGAACATAA |

| 15 | KfrCRK2N | gcgaattcaTGAGCAGCTACAGCAGAG |

| 16 | KfrCRK2R | gcggtaccTTAGCTGGGCTTGTTTGAC |

| 17 | KfrCRKst | cgcccgggGCTGGGCTTGTTTGACAGG |

| 18 | KfrCstop | cggtcgacCCGCTCTAGATCGTCTTCAT |

| 19 | KfrCXbaF | cgTCTAGAGCGGAAGCTTGCGG |

| 20 | LinkSceF | tagggataacagggtaatgtac |

| 21 | LinkSceR | attaccctgttatccctagtac |

| 22 | mobC1 | cggaattcATGGCAAAGAGCTATCGGATCG |

| 23 | mobC2 | cggtcGACTCGCTTAACTCGGCCTTTCA |

| 24 | mobCT | gcgagctccTTCATCGATCCCCCACTTG |

| 25 | nic1 | cggaattcATGAATAAGGGCTATGACACTCTAGCCGGG |

| 26 | nic2 | cggtcgacTTATCTCTCGTCTTCGTCCC |

| 27 | Nic2k | gcgagctcgTCTCTCGTCTTCGTCCCTCTCTGATTTTGC |

| 28 | OKFRCD2 | tcgacggtaccagcggcttcaCCGCT |

| 29 | OKFRCG2 | CTAGAGCGGtgaagccgctggtaccg |

| 30 | OPETD | GATCGTGCAGC |

| 31 | OPETG | CATGGCTGCAC |

| 32 | pGBT30R | CTCTTCCGCATAAACGCTTC |

| 33 | podst4F | aattggggctcc |

| 34 | podst4R | agctggagctcc |

| 35 | T7TERR | gcgtcgacCAAAAAACCCCTCAAGACCC |

| 36 | TerpKKKF | cgcggtaccctcgagcccgggATCAGAACGCAGAAGCGGTC |

| 37 | TerpKKR | cgcggtaccagtactGGCTTGTAGATATGACGACAG |

| 38 | TraGEcoF | gcgaattcATGAAGATCAAGATGAACAAC |

| 39 | TraGKpnR | gcggtacCTCATATCGTGATGCCCTCCC |

| 40 | TraGRK2F | gcgaattcATGAAGAACCGAAACAACGCC |

| 41 | TraGRK2R | gcggtacCTCATATCGTGATCCCCTCC |

| 42 | TraGRKst | cgcccgggTATCGTGATCCCCTCCCCTTC |

| 43 | TraGSmaR | cgcccgggTATCGTGATGCCCTCCC |

| 44 | virD4Gm | gcggattcATGACCCAGAATTCAAACGGACAC |

| 45 | virD4Kpn | cgggtaCCTTATGCCGCTTCAGCCAAGCCATT |

| 46 | virD4N | cggagctcCTGCCGCTTCAGCCAAGCCATTAA |

| 47 | VirDfr2F | gcgaattcTTGCGTGAAACATATGGG |

| 48 | VirDfrBR | gcggaTCCTTATGCCGCTTCAGCCAAG |

| 49 | VirDMunF | cgcaattgATGACCCAGAATTCAAACG |

| 50 | TProLyzF | gcgaattctacgtactcgagagatctACATGTGGTACCAACCACC |

| 51 | TProLyzR | gcgtcgacCCATGGATAATAGTTAACGAG |

| 52 | delincF | CGAGGATGAGGCATATAAACAGGCTAATAAACCAAAGGGTTGAGCATATGATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC |

| 53 | delincR | CCGCTGAGGTCTGCCCCTTTACCACTCATTCAGCCACCCCCATTTTTTCATGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTCG |

| 54 | delnicF | TCGCCGGTTTGCTTCAACGCAACTTAAACAAGTGGGGGATCGATGAATAAATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC |

| 55 | delnicR | GAACGCTAAATACCTGAAAACAAAAACCGGCCAACAGGCCGGTTTTTTTATGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTCG |

| 56 | delvirF | TAACGGAGATTTACTATGACCCAGAATTCAAACGGACACAAATGGCGTAAATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC |

| 57 | delvirR | TATGTTTTTTCCTGTGCAATATTTGCCATTTCAATTATTCCTTATGCCGCTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTCG |

| 58 | delparF | CGACCTGGTGAGCCTGGCCGAAGGCCAAAAGCCACTGCAAAACCGAAAAAATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC |

| 59 | delparR | AGACGCTAGCAAATTGCGAATCCTGCCCTAGTTCTAACCCCCCCATGTTTTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTCG |

| 60 | deloriF | AACCGAAAAATTTCGTACGTACGAAAAAACATGGGGGGGTTAGAACTAGGATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC |

| 61 | deloriR | GGGGGACAGGTGCAATTTTAGCACAAGCGGCGGCAGACGCTAGCAAATTGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTCG |

| 62 | oriparF | GCCGAAGGCCAAAAGCCACTGCAAAACCGAAAAATTTCGTACGTACGAAAATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC |

| 63 | delkfrAF | ATGTATTGTATTAAAATACAATACATACAATACAGGGAGCCGAAGCCATGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTCG |

| 64 | delkfrAR | CACTTTATCTGTTTACGTCAATAGATAGGGGTTACTCTTTGGTGTCGGCTGCATGGGAATTAGCCATGG |

| 65 | delkfrCF | CCTGGCAGGTTTCGGGGCTATATGGGACGCTGACCGGGATTGAAACCATGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTCG |

| 66 | delkfrCR | AATGGCCGGGGTCGGTGACAGGGTAGCGGCTTCACCGCTCTAGATCGTCTTCATGGGAATTAGCCATGG |

| 67 | Kmpar1F | GGTGCAAAGACGCCGTGGAAGCGTGTGAGGTTGACTCGCGGCTTAGGTACATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC |

| 68 | Kmpar2R | TGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTCG |

| 69 | Kmpar3F | cgaacgagctccagcctacaCTTGCATGCCTGCAGGGTAC |

| 70 | Kmpar4R | CCCATGTGATCTTCGAGCCGCTGGACTTCATCGCCAAACTCGCTGCGTTGGGTACCCTGCCGGGGTTCTC |

Start and stop codons are marked in bold, the introduced restriction sites or overhangs are underlined, nucleotides not complementary to the template are shown in small letters, an additional Shine–Dalgarno sequence is underlined, and oligonucleotides used for mutagenesis [30] sequence corresponding to RA3 is in italics.

4.2.1. Construction of KfrC Alanine Substitution Mutant

To introduce mutations into the putative active site of kfrC, a two-step PCR was used. The pairs of primers 8/13 and 12/32 (Table 4) were designed to introduce nucleotide substitutions in a particular region accompanied by the introduction of a NotI restriction site to facilitate screening. In the first step, two products were amplified on a pESB5.88 template with primers 8 and 13 or 12 and 32, which after purification served as a template in the second PCR reaction with primers 8 and 32. The final PCR product was inserted between EcoRI-SalI sites of pGBT30 to give pOMB9.31 (tacp-kfrC*).

4.2.2. Construction of the translational fusions of FLAG with VirD434–641 via N-terminus and KfrC with His6-tag via C-terminus

The kfrC gene without a stop codon was amplified with primers 14/18 and cloned downstream of virD4434–641 in pOMB1.42. The EcoRI-SalI fragment with both genes was re-cloned into pKAB20 and digested using MunI and XhoI restriction enzymes to create translational fusions of FLAG-VirD4434–641 and KfrC-His6, respectively. Finally, the EcoRI-SalI fragment carrying flag-virD4434–641 kfrC-his6 was re-cloned into pKAB28 (pET28mod derivative) to obtain pOMB8.52.

4.2.3. Construction of RA3# Derivative with parSP1-Kmr Cassette

Kmr cassette amplified on a pKD13 template with primers 67 and 68 and parSP1 prophage amplified on a pOMB3.104 template with primers 69 and 70 were used as a template in the second PCR reaction with primers 67 and 70. The final PCR product was inserted within integron at position 38,663 of the RA3 genome with the use of the Datsenko and Wanner method [30].

4.3. Bacterial Transformation and Conjugation

Bacterial transformation was done using the standard methods [50]. Electroporation was carried out using 2-mm gap cuvettes at 25 μF, 200 Ω, 2.5 kV in a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser.

The E. coli DH5α transformants with RA3 variants or the helper strain E. coli S17-1 harboring pESB11 or pOMB12.15 (tacp-kfrC) were used as the donors in the conjugations with the chosen Rifr strains of A. tumefaciens, P. aminovorans, A. veronii, C. necator, or P. putida as described previously [18,26]. Briefly, aliquots of 100 µL of stationary phase cultures of the donor and recipient strains, rinsed previously with L broth, were mixed on an L agar plate and incubated overnight at 28 °C. Bacteria were washed off the plate and serial dilutions were plated on an appropriate solid medium selective for transconjugants. The frequency of the conjugative transfer of RA3 or its derivatives between E. coli strains or P. putida strains was analyzed using a modification of this method. Suspensions of donor and recipient cells were mixed on the sterile nitrocellulose filters and incubated on L agar plate at 37 °C or 28 °C. Filters were immersed into 0.2 mL of L broth, vortexed, and serial dilutions plated on L-agar with antibiotics selective for transconjugants. After 24–48 h of incubation at 28 °C or 37 °C, obtained colonies were counted. Suspension of the donor cells was treated in the same manner but incubated separately on the filter to serve as a reference. Conjugation frequency was expressed as the number of transconjugant colonies per donor colonies formed. The reported values are the average of at least three different experiments.

4.4. Bacterial Adenylate Cyclase Two-Hybrid (BACTH) System

Possible interactions between proteins were analyzed in vivo using the BACTH system [34] as described previously [26]. Genes encoding proteins of interest were cloned into the BACTH vectors to create translational fusions with CyaAT18 (pKGB4, pLKB4 plasmids) or CyaAT25 (pKGB5, pLKB2) fragments via N- or C-terminus, respectively. Pairs of the compatible plasmids were cotransformed into E. coli BTH101 cyaA and transformants were selected on L agar supplemented with kanamycin, penicillin, and 0.15 mM IPTG. Bacteria were incubated for approximately 48 h and randomly chosen transformants were re-streaked on the selective MacConkey medium with 1% maltose as a carbon source. Reconstitution of the CyaA activity due to the interactions between analyzed proteins led to the activation of sugar catabolism operons in E. coli, e.g., mal and lac, manifested by forming purple colonies on maltose containing solid medium and an increase of β-galactosidase activity in the extracts from the liquid cultures. The β-galactosidase activity was assayed using the standard method [61]. One unit of β-galactosidase is defined as the amount of enzyme needed to convert 1 μmol of o-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (ONPG) to o-nitrophenol and D-galactose in 1 min under standard conditions.

4.5. Genome-Wide Library Construction of E. coli, A. veronii, and RA3 Plasmid Using BACTH System

For genomic DNA extraction of E. coli DH5α and A. veronii, the modified method of Chen and Kuo was used [62]. For plasmid RA3, the large-scale isolation Plasmid Giga Kit (QIAGEN) was used and the additional step of electroelution of the plasmid DNA from the agarose pad into the dialysis bags was applied [63] that separated the plasmid DNA from genomic DNA contamination. Obtained DNA was fragmented and cloned into the pOMB4.0 vector as described in detail in the supplemental material. The quality of the obtained genomic library was evaluated by determination of its size, the percentage of the genome coverage, and the percentage of the plasmids that have an insert. The probability of having a particular fragment inserted in the right orientation and in frame with the cyaT18 fragment was calculated using the formula below [64].

| p = 1 − (1 − i/6G) N |

i—the mean insert size [bp]

G—the genome size [bp]