Abstract

Syndrome of undifferentiated recurrent fever (SURF) is a heterogeneous group of autoinflammatory diseases (AID) characterized by self-limiting episodes of systemic inflammation without a confirmed molecular diagnosis, not fulfilling the criteria for periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis and adenopathy (PFAPA) syndrome. In this review, we focused on the studies enrolling patients suspected of AID and genotyped them with next generation sequencing technologies in order to describe the clinical manifestations and treatment response of published cohorts of patients with SURF. We also propose a preliminary set of indications for the clinical suspicion of SURF that could help in everyday clinical practice.

Keywords: autoinflammatory diseases, NGS, SURF, FMF, colchicine, anakinra

1. Introduction

Syndrome of undifferentiated recurrent fever (SURF) is a heterogeneous group of autoinflammatory diseases (AID) characterized by self-limiting episodes of systemic inflammation without a confirmed molecular diagnosis. First defined by Broderick et al., [1] SURF is increasingly diagnosed in patients with recurrent fever after exclusion of the main hereditary recurrent fevers (HRF) and periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis and adenopathy (PFAPA) syndrome [2]. Recent evidence suggests the presence of a multi-organ presentation in SURF and, in a relevant percentage of the patients, a complete or at least partial response to colchicine, usually not observed with the same high frequency in PFAPA syndrome [3]. It is possible that omics-based technologies will provide a relevant opportunity to analyse the functional characteristics of immune cells in SURF patients, highlighting the pathological relevance of possible novel genes and supporting the development of new diagnostic tests. On the other hand, the response to colchicine suggests a possible crucial role of cytoskeleton and related proteins, as observed in the other form of HRF responding to this drug, namely the familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) [4]. In this systematic literature review, we will (1) identify a subgroup of patients with SURF among cohorts of patients with suspected AID undergoing next generation sequencing (NGS); (2) describe the clinical manifestations and therapeutic responses of these patients; (3) propose a set of indications for the clinical suspicion of SURF, with the aim of supporting the diagnostic approach in everyday life.

2. Materials and Methods

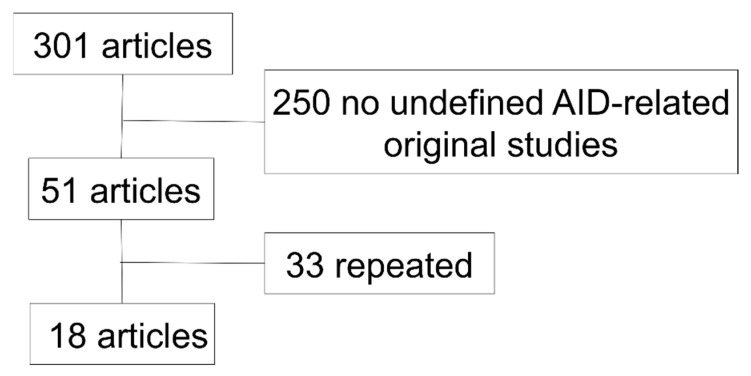

All the original English studies found in the PubMed database (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; accessed on 2 February 2020) with the queries: “periodic/recurrent fever/s” AND “NGS/Sanger”; “undefined/undifferentiated” AND “autoinflammatory”; “NGS/Sanger” AND “autoinflammatory”, were included in this review (Figure 1). Excel software was used for the analysis. A descriptive statistical analysis was performed using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables; median and range for numerical variables.

Figure 1.

Original English studies found in the PubMed database (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; accessed on 2 February 2020) with the queries: “periodic/recurrent fever/s” AND “NGS/Sanger”; “undefined/undifferentiated” AND “autoinflammatory”; “NGS/Sanger” AND “autoinflammatory”. AID, autoinflammatory diseases.

3. Results

3.1. Studies Selection and Main Characteristics

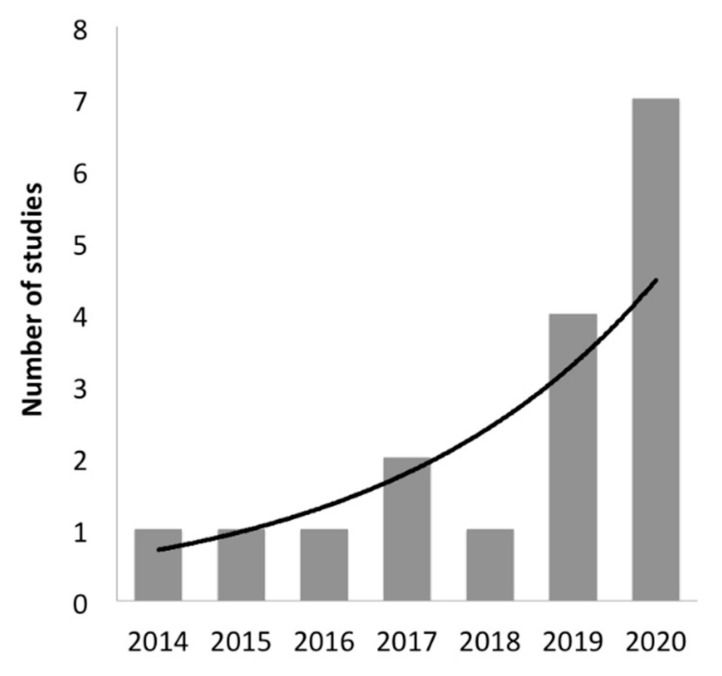

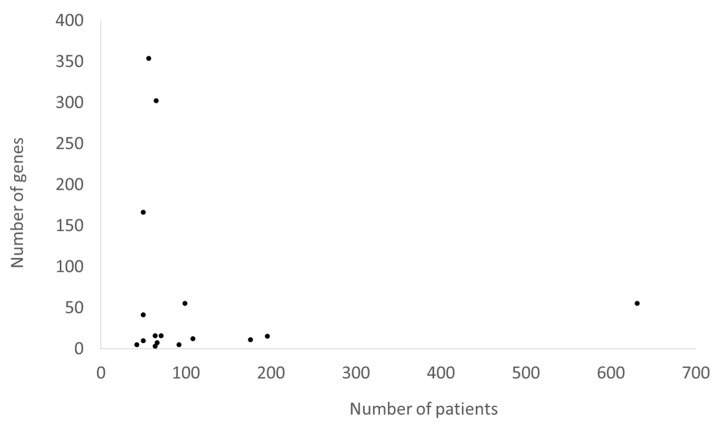

The main characteristics of the 18 studies regarding the performance of NGS analysis in patients suspected of AID are reported in Table 1. The number of these studies is increased overtime (Figure 2). Recurrent fever has been included in the enrolment criteria by 6/18 (33%) studies. A total of 2179 patients suspected of AID have been genotyped by NGS since 2014. Studies enrolling a large amount of patients usually did not perform an analysis of many genes and vice versa (Figure 3). However, the number of analysed genes in the NGS panels used in the available studies that only referred to AID did not exceed 55. Analysed genes of each study are reported in the Supplementary Table S1. The major enrolled ethnic groups of patients were Caucasian, Middle Eastern and Asian. The exclusion criteria of a previous diagnosis of PFAPA or clinical FMF was informed by the modified Marshall’s criteria and the Tel-Hashomer’s criteria, respectively.

Table 1.

Studies about the NGS analysis in patients suspected of AID.

| N° | Study | Date | Enrollment Criteria | Pts | Ethnicity | Genes | MAF | Predictive in Silico Tools | Variant Classification Tools | Sanger Confirmation | Variants | Variants for Pts, Median (Range) | Pts with Clearly Pathogenic Variants | Pts with Likely Pathogenic Variants | Pts with VUS | Pts with Likely Benign or Benign Variants | Pts without Variants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chandrakasan et al. [5] | 2014 | Periodic fever | 66 * | Caucasian (14), African (7), others (5)° | 7 | ND | ND | Infevers | Yes | 44 | 0.8 (0–4) * | 25 (42) | 0 (0) | 6 (10) | 0 (0) | 28 (48) |

| 2 | De Pieri et al. [6] | 2015 | Periodic fever with negative or indefinite genetic analysis; PFAPA syndrome with very early onset and/or poor response to steroids or tonsillectomy | 42 | Caucasian | 5 | Any | SIFT, PP2, MT, MutationAssesor, HSF, NNSplice | EMGQN | Yes | 38 | 0.9 (0–4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 24 (57) | 5 (12) | 13 (31) |

| 3 | Rusmini et al. [2] | 2016 | Systemic AID with at least one mutation in one AID-related gene by Sanger sequencing | 50 ** | Caucasian | 10 | <5% | SIFT, PP2 | ND | Yes | 254 | 5(ND) | 23 (68) | 7 (21) | 4 (12) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 4 | Nakayama et al. [7] | 2017 | Clinical diagnosis of AID | 108 | Asian | 12 | <1% | ND | ND | Yes | 27 | 0.25(ND) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 5 | Omoyinmi et al. [8] | 2017 | Undiagnosed inflammatory diseases with clinician suspicion of a genetic cause and negative conventional genetic tests | 50 | Mixed | 166 | <1% ^ | SIFT, PP2, MT | ACGS | Only VUS | 325 | 6.5 (1–16) | 6 (12) | 11 (22) | 31 (62) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) |

| 6 | Kostik et al. [9] | 2018 | Clinical suspicious of primary immunodeficiency with periodic fever | 65 | ND | 302 | <3% | SIFT, PP2, MT, CADD | ClinVar | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 7 | Karacan et al. [10] | 2019 | Symptoms suggestive of a systemic AID; exclusion of typical FMF | 196 | Middle Eastern | 15 | <1% | ND | ClinVar, Infevers, HGMD | ND | ND | ND | 14 (10) | 27 (14) | 97 (50) § | 97 (50) § | 58 (30) |

| 8 | Ozyilmaz et al. [11] | 2019 | Periodic fever | 64 | Middle Eastern | 3 | Any | ND | ClinVar | ND | 13 | 0.2 (0–1) | 4 (6) | 0 (0) | 3 (5) | 6 (9) | 51 (80) |

| 9 | Hua et al. [12] | 2019 | Chinese adults suspected of systemic AID | 92 | Asian | 5 | ND | ND | EMGQN, Infevers | ND | 49 | 0.5 (0–4) | 5 (5) | 0 (0) | 33 (36) | 0 (0) | 54 (59) |

| 10 | Boursier et al. [13] | 2019 | Suspected monogenic AID (except FMF, DADA2 and MKD after March 2018) | 631 | ND | 55 | ND | SIFT, PP2, MT, MES, HSF, NNSplice, SSF, | Infevers | ND | 176 | 0.3 (ND) | 44 (7) | 50 (8) | 63 (10) | 0 (0) | 474 (75) |

| 11 | Papa et al. [3] | 2020 | Pediatric onset systemic AID; exclusion of PFAPA syndrome and others etiologies; negative or not conclusive Sanger sequencing of suspected genes | 50 | Caucasian | 41 | <3% | SIFT, MT, FATHMM, MetaSVM, PROVEAN, CADD | ClinVar | Yes | 100 | 2 (0–6) | 3 (8) | 3 (8) | 25 (50) | 10 (20) | 9 (18) |

| 12 | Suspitsin et al. [14] | 2020 | Periodic fever | 56 | ND | 354 | ND | ND | ClinVar | Yes | ND | ND | 9 (16) § | 9 (16) § | 7 (13) | 40 (71) § | 40 (71) § |

| 13 | Sözeri et al. [15] | 2020 | Symptoms suggestive of a systemic AID; exclusion of FMF, PFAPA syndrome and other common etiologies; positive Eurofever score for MKD, TRAPS and CAPS | 71 | Caucasian, Middle Eastern | 16 | <1% | SIFT, PP2, MT, GERP | EMGQN, ClinVar, HGMD, Eurofever criteria | ND | 74 | 1 (0–3) | 35 (49) | 0 (0) | 36 (51) § | 36 (51) § | 36 (51) § |

| 14 | Hidaka et al. [16] | 2020 | Unexplained fever | 176 | Asian | 11 | <1% | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 29 (17) | 0 (0) | 53 (30) | 0 (0) | 94 (53) |

| 15 | Kosukcu et al. [17] | 2020 | Recurrent fever and high C-reactive protein along with clinical features of inflammation with a possible AID; infections excluded; negative analysis of 14 AID-related genes | 11 | Middle Eastern | WES | <1% | SIFT, PP2, MT, CADD, REVEL, VEST4 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 4 (36) § | 4 (36) § | 7 (64) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 16 | Wang et al. [18] | 2020 | Pediatric patients suspected of monogenic AID | 288 | Asian | 3/347/WES | <1% | SIFT, PP2, MT, CADD, UMD-Predictor | ClinVar, Infevers, HGMD | Yes | ND | ND | 79 (27) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 17 | Demir et al. [19] | 2020 | Symptoms suggestive of a systemic AID; exclusion of FMF, PFAPA syndrome, Blau syndrome, infantile sarcoidosis and other common etiologies; positive Eurofever score for MKD, TRAPS and CAPS | 64 | Caucasian, Middle Eastern | 16 | <1% | SIFT, PP2, MT, GERP | ClinVar, HGMD | Yes | ND | ND | 15 (23) | 21 (33) § | 21 (33) § | 28 (44) § | 28 (44) § |

| 18 | Rama et al. [20] | 2021 | Symptoms of AID (>3 attacks, elevated CRP, age of onset <30 years); exclusion of Armenian, Turkish, Sephardic and Arabic when mentioned and other causes of inflammation | 99 | ND | 55 | <1% | SIFT, PP2, MT, MES, HSF, NNSplice, GVGD, Grantham score | Infevers | Yes | ND | ND | 10 (10) § | 10 (10) § | 20 (20) | 69 (70) § | 69 (70) § |

* seven patients were not analyzed; Hispanic, Vietnamese, Asian-Indian, Puerto Rican-Filipino-Mixed European; ** 16 patients were not classified; ^ except for the PRF1 p.A91V, TNFRSF1A p.R92Q, and NLRP3 p.V198M variants; § classification was not specified. Results are shown as numbers (%) unless stated otherwise. ND, not declared; NGS, next generation sequencing; MAF, minor allele frequency; AID, autoinflammatory diseases; FMF, familial Mediterranean fever; PFAPA, periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis and adenopathy; MKD, mevalonate kinase deficiency; TRAPS, TNF receptor associated periodic syndrome; CAPS, cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome; ACGS, Association for Clinical Genetics Society; EMGQN, European Molecular Genetics Quality Network; HGMD, Human Gene Mutation Database; CRP, C-reactive protein; VUS, variant of unknown significance; SIFT, Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant; PP2, Polymorphism Phenotyping version 2; MT, Mutation Taster; HSF, human splicing finder; NNSplice, Splice Site Prediction by Neural Network; CADD, Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion software; GERP, Genomic Evolutionary Rate Profiling; MES, Manufacturing Execution System; SSF, Splice Site Finder; FATHMM, Functional Analysis Through Hidden Markov Models; MetaSVM, Meta-analytic Support Vector Machine; PROVEAN, Protein Variation Effect Analyzer; REVEL, Rare Exome Variant Ensemble Learner; UMD, Universal Mutation Database; GVGD, Grantham Variation and Grantham Deviation.

Figure 2.

Trend line of studies in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Correlation between the numbers of enrolled patients and analyzed genes of studies in Table 1 except the two using whole exome sequencing.

3.2. Genotype-Phenotype Assessment

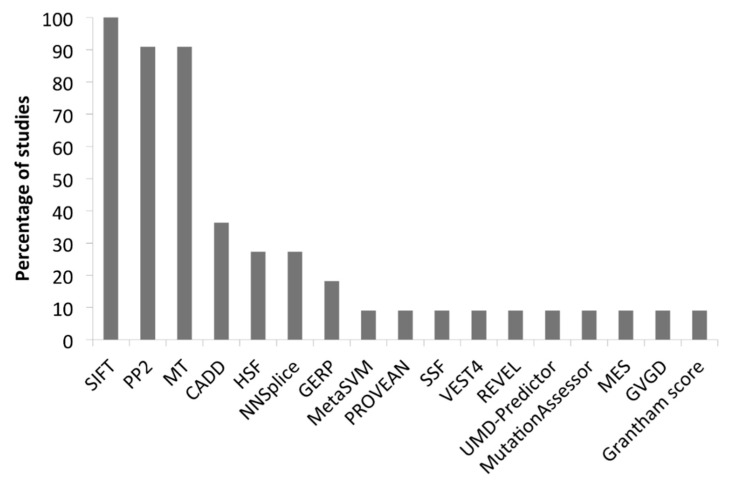

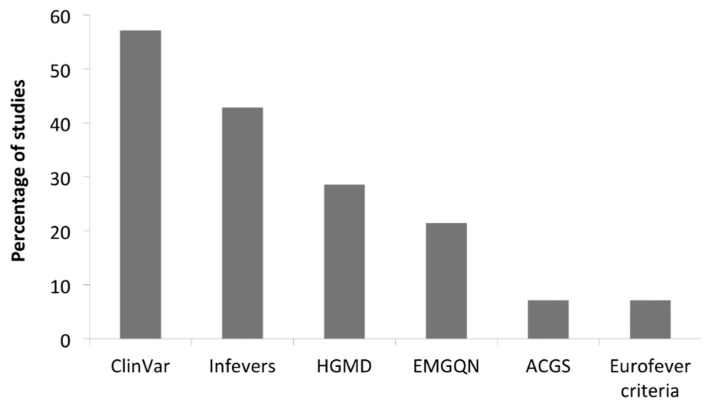

All the analysed studies are reported in Table 1. The assessment of the pathogenicity of each identified variant was obtained by using the minor allele frequency (MAF), predictive software, classification tools and Sanger sequencing confirmation analysis in 12/18 (67%), 11/18 (61%), 14/18 (78%) and 10/18 (56%) studies, respectively. Some studies considered also the pattern of inheritance and available family data. For assessing the MAF, the 1000 Genome Project (http://www.1000genomes.org accessed on 2 February 2021), the Exome Variant Server (http://esv.gs.washington.edu/ESV/ accessed on 2 February 2021), the Exome Aggregation Consortium database (http://exac.broadinstitute.org/ accessed on 2 February 2021) and the Genome Aggregation database (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/ accessed on 2 February 2021) were used. Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant (SIFT; https://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/ accessed on 2 February 2021) is the most frequently used predictive in silico software (Figure 4), followed by the Polymorphism Phenotyping version 2 (PP2; http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/index.shtml accessed on 2 February 2021) and Mutation Taster (MT; http://www.mutationtaster.org/ accessed on 2 February 2021). Since its first description in 2014, the Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion software (CADD; https://cadd.gs.washington.edu/ accessed on 2 February 2021) is routinely implemented. The most used variant classification tools are ClinVar and the AID-focused website Infevers (https://infevers.umai-montpellier.fr/web/index.php accessed on 2 February 2021) that reports the International Study Group for Systemic Autoinflammatory Diseases (INSAID) variant classification (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Predictive software of studies in Table 1. SIFT, Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant; PP2, Polymorphism Phenotyping version 2; MT, Mutation Taster; CADD, Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion software; HSF, human splicing finder; NNSplice, Splice Site Prediction by Neural Network; GERP, Genomic Evolutionary Rate Profiling; MetaSVM, Meta-analytic Support Vector Machine; PROVEAN, Protein Variation Effect Analyzer; SSF, Splice Site Finder; REVEL, Rare Exome Variant Ensemble Learner; UMD, Universal Mutation Database; MES, Manufacturing Execution System; GVGD, Grantham Variation and Grantham Deviation.

Figure 5.

Classification tools of studies in Table 1. HGMD, Human Gene Mutation Database; EMGQN, European Molecular Genetics Quality Network; ACGS, Association for Clinical Genetics Society.

3.3. Variants Characteristics

In total, more than 1100 variants were reported, ranging from 0.2 to 6.5 per patient. The median rate of detection of a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant in an undefined AID patient was 20%, ranging from 0% to 89%. Thus, the number of undefined AID patients persists as quite high even if the NGS or the whole exome sequencing (WES) approach has been used (73% in Wang et al.). No studies using a whole genome sequencing approach in undefined AID patients have been published to date.

3.4. Clinical Manifestations

As reported in the Methods, patients with suspected AID and undefined recurrent fevers that did not reach a molecular diagnosis after NGS analysis were considered as SURF. Detailed clinical descriptions of 486 SURF patients were available in 5/18 (28%) studies reported in Table 1 and in an additional four specific studies found in the PubMed database.

Clinical features of these patients are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of SURF patients published in the English literature.

| Study | Chandrakasan et al. [5] | Harrison et al. [24] | De Pauli et al. [22] | Ozyilmaz et al. [11] | Ter Haar et al. [21] | Garg et al. [23] | Papa et al. [3] | Hidaka et al. [16] | Demir et al. [19] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2014 | 2016 | 2018 | 2019 | 2019 | 2019 | 2020 | 2020 | 2020 |

| Patients | 25 | 11 | 23 | 9 | 180 | 22 | 34 | 133 | 49 |

| Ethnicity (patients) | Caucasian (14), African (7), others (5) | Caucasian (10), Jewish (1) | Caucasian (20), Middle Eastern (2), others (1) | Middle Eastern | Mixed | Caucasian (11), Asian (5), Jewish (1), African (1), others (4) | Caucasian | Asian | Caucasian, Middle Eastern |

| Age at enrollment, median (range), years | 2.5 (0–9) | ND | 4.3 (2–9) | 18 (1–47) | ND | ND | ND | 39.9 (22–57) | 5.9 (3–9) |

| Age at onset, median (range), years | 1.4 (0–5) | 35 (24–76) | 0 (0–2) | ND | 4.3 (1–12) ** | 0.61 (0–13.5) | ND | 33.4 (13–53) | 3 (1–6) |

| Adults onset | 0 (0) | 11 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 65 (35) ** | 0 (0) | ND | ND | ND |

| Gender, M:F | 16:9 | 5:6 | 5:18 | 5:4 | 51:49 ** | 8:14 | ND | 66:67 | 34:15 |

| Positive family history | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ND | 1 (11) | 24 (13) ** | 7 (32) | ND | ND | 12 (24) |

| Attacks/year, median (range) | 8 (4–12) | ND | ND | ND | 12 (5–14.5) | ND | 12 (7–24) | ND ^ | 10 (6–12) |

| Attacks duration, median (range), days | 4 (3–5) | ND | ND | ND | 4 (3–7) | ND | 5.9 (4.5–7.3) | ND ^ | 3 (2–4) |

| Clinical manifestations | 25 (100) | 11 (100) | 23 (100) | 9 (100) | 180 (100) | 22 (100) | 34 (100) | 133 (100) | 49 (100) |

| Fever | 25 (100) | 11 (100) | ND | 6 (67) | 180 (100) | 13 (59) | 34 (100) | 133 (100) | 49 (100) |

| Abdominal pain | 1 (4) | 2 (18) *** | 12 (52) | 8 (89) | 87 (48) | 4 (18) | 17 (50) | ND | 31 (63) |

| Nausea/Vomiting | ND | 2 (18) *** | ND | ND | 44 (24) | 5 (23) | 3 (9) | ND | 8 (16) |

| Diarrhea | 2 (8) | 2 (18) *** | ND | ND | 30 (17) | 3 (14) | 3 (9) | 40 (30) | 5 (10) |

| Rash/Erythema | 3 (12) | 9 (82) | ND | ND | 35 (20) | 12 (55) | 11 (32) | 10 (8) | 22 (45) |

| Genital ulcers | ND | 1 (9) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Oral ulcers | 1 (4) | 3 (27) | 12 (52) | ND | 53 (29) | ND | 13 (38) | ND | 14 (29) |

| Pharyngitis/Tonsillitis | 1 (4) | ND | 13 (57) | ND | 47 (18) | ND | 13 (38) | ND | 5 (10) |

| Eye manifestations | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 14 (64) | ND | ND | 11 (22) |

| Arthritis | 2 (8) | 5 (46) | ND | 1 (11) | 12 (7) | 12 (55) | 7 (21) | ND | 4 (8) |

| Arthralgia | ND | 8 (72) | ND | ND | 107 (59) | 10 (46) | 12 (35) | 57 (43) | 27 (55) |

| Myalgia | ND | 8 (72) | 15 (65) | ND | 80 (44) | 13 (59) | 9 (27) | 25 (19) | 23 (47) |

| Headache | 1 (4) | 5 (46) | ND | 1 (11) | 67 (37) | 1 (5) | 7 (20) | ND | 10 (20) |

| Morning headache | ND | ND | ND | ND | 22 (12) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Fatigue | ND | 11 (100) *** | ND | ND | 106 (59) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Malaise | ND | 11 (100) *** | ND | ND | 99 (55) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Lymphadenopathy | 1 (4) | 4 (36) | ND | ND | 76 (42) | 12 (55) | 6 (18) | ND | ND |

| Splenomegaly | ND | ND | ND | ND | 20 (11) | ND | 5 (15) *** | ND | 1 (2) |

| Hepatomegaly | ND | ND | ND | ND | 21 (12) | ND | 5 (15) *** | ND | ND |

| Chest pain | ND | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 21 (12) | 5 (23) | ND | 17 (13) | 4 (8) |

| Pericarditis | ND | 2 (18) | ND | ND | 10 (6) | ND | ND | ND | 1 (2) |

| Urethritis/cystitis | ND | ND | ND | ND | 6 (3) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Gonadal pain | ND | ND | ND | ND | 3 (2) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Neck stiffness | 1 (4) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Sinusitis | ND | 6 (55) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Febrile seizure | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 4 (8) |

| Pleuritis | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1 (2) |

| Proteinuria | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1 (2) |

| Amyloidosis | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1 (2) |

| Sensorineural hearing loss | ND | ND | ND | 0 (0) | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0 (0) |

| Patients with information about the response to treatment | 25 (100) | 11 (100) | ND | ND | ND | 22 (100) | 18 (53) | 133 (100) | 49 (100) |

| On demand NSAIDs | ND | ND | ND | ND | 80/105 (76%) | 3/22 (14%) | ND | ND | ND |

| On demand steroids | ND | 6/10 (60%) | 16/21 (76%) | ND | 85/104 (82%) | 11/22 (50%) | 17/18 (94%) | 29/133 (22%) | ND |

| Colchicine | 15/25 (60%) | 0/3 (0) | 6/13 (46%) | ND | 29/49 (59%) | ND | 14/18 (78%) | 44/133 (33%) | 31/49 (63%) |

| DMARDs | ND | 0/10 (0) | ND | ND | 7/10 (70%) | 13/22 (59%) | ND | ND | ND |

| Anakinra | ND | 10/11 (90%) | ND | ND | 8/13 (62%) | 16/22 (73%) | ND | ND | ND |

| Tonsillectomy/Adenoidectomy | ND | ND | 0/12 (0) | ND | 2/12 (17%) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

Hispanic, Vietnamese, Asian-Indian, Puerto Rican-Filipino-Mixed European; ** including seven patients with a chronic disease course; ^ 57.1% > 1 episodes/months and 54.9% ≤ 3 days; *** not specify. Results are shown as numbers (%) unless stated otherwise. ND, not declared; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; DMARDs, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs.

The larger cohorts of patients came from the international Eurofever registry, Japan and Middle East [16,19,21]. The median ages at the symptoms onset and patient enrollment are 13 (±13) and 25 (±18) years, respectively. In the four pediatric studies, the median diagnosis delay was 35 months (range 13–78) [5,19,22,23]. Males are 42% of the total. A positive family history ranged from 0% to 32%.

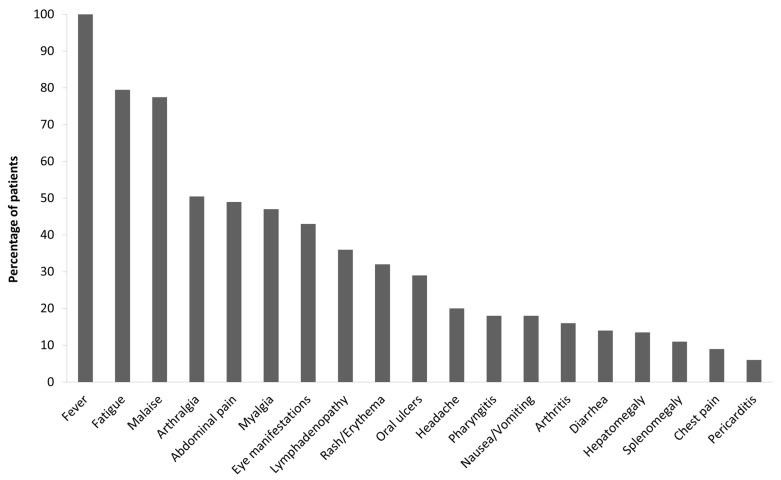

The median duration of inflammatory attacks was 4 ± 1 days with a monthly frequency (11 ± 2 attacks/years). The most frequently reported symptoms during fever attacks were fatigue and malaise (>70% of the patients; Figure 6). Arthralgia, abdominal pain, myalgia and eye manifestations were reported in >40% of the patients. Lymphadenopathy, rash/erythema and oral ulcers were less frequently reported (20–40% of the patients). Headache, pharyngitis, arthritis, nausea/vomiting, diarrhea and hepato/splenomegaly were reported in 10–20% of the patients, and chest pain and pericarditis in less than 10%. Sinusitis, urethritis/cystitis, genital ulcers, gonadal pain, neck stiffness, morning headache, febrile seizure, pleuritis, proteinuria, amyloidosis and sensorineural hearing loss were reported by only single studies.

Figure 6.

Clinical manifestations of SURF patients reported by at least two studies of Table 2. SURF, syndrome of undifferentiated recurrent fever.

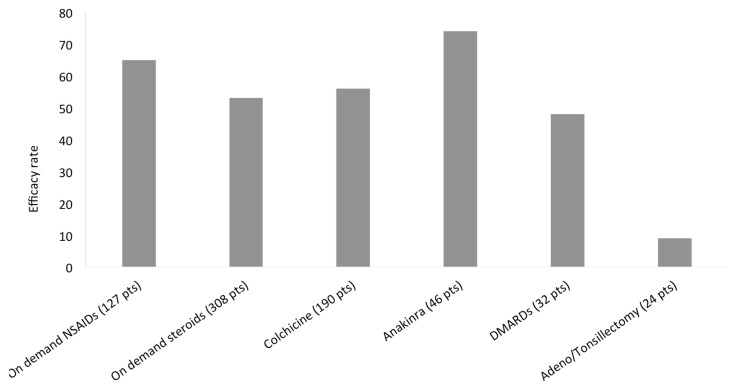

3.5. Treatment Response

The effect of treatment was considered with different methods among the various studies and, herein, any judgement of an evident amelioration of the clinical manifestations after a given treatment. Only a few studies reported a difference between a partial and complete response, and not all authors carefully described the differences between these types of treatment response. Furthermore, on demand or continuous treatment was not always specified. Taking into account these general considerations, the efficacy rate of treatments used in SURF patients is shown in Figure 7. The most frequent treatments were steroids on demand (308 patients) with at least a partial efficacy described in >50% of patients, followed by continuous colchicine treatment (190 patients) and on demand non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (127 patients) with a similar efficacy rate (56% and 65%, respectively). Anti-interleukin (IL)-1 treatment (mainly anakinra) was the most effective and frequently used biologic therapy, administered to 46 patients with an efficacy rate of 74%. DMARDs were less frequently used and less effective: 32 patients were treated with different drugs (methotrexate, ciclosporin, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil) with an efficacy rate of 48%. Adenoidectomy and tonsillectomy were performed in only 24 patients with a very low efficacy rate (9%).

Figure 7.

Treatment efficacy in SURF patients. SURF, syndrome of undifferentiated recurrent fever; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; DMARDs, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug.

4. Discussion

In the present analysis, we systematically reviewed the papers enrolling patients with suspected AID who were extensively genotyped by NGS technology in order to define the clinical manifestations and response to treatment in patients with recurrence of undefined inflammatory attacks, not fulfilling any PFAPA criteria [25,26] and identified under the new term of SURF.

Inflammation is the first sign of immune system activation against pathogens and damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPS) in living organisms. In the case of the occurrence of inborn errors of immunity, the so-called horror autoinflammaticus may develop [27]. In the first conditions reported, the most characteristic clinical feature associated with AID was the recurrence of self-resolving fever attacks, namely HFR. However, a subclinical inflammation in affected patients may be associated with long term or life-threatening complications, such as amyloidosis, with an evident impact on quality of life and life expectation. An early diagnosis and a proper treatment may prevent a severe outcome.

Despite the fact that recurrence was implicit in the definition of the original group of HRF (FMF, MKD, TRAPS), the pathogenic mechanisms correlated with the alternation between flares of inflammation and periods of complete wellbeing still represent a dilemma. The existence is hypothesized of an unbalanced up-regulation of the inflammatory response to common hits, followed by a negative feedback able to down-modulate the primary cause of the immune system hyperactivation. This virtuous cycle prevents an early exitus in people with minor defects in the innate immune system that can cause milder AID phenotypes and allows these mutations to be inherited across future generations. The molecular definition of numerous monogenic AID during the last 20 years dramatically increased our knowledge of the pathways and proteins involved in the innate immune system [28]. However, the large amount of patients displaying undefined recurrent fevers even after NGS suggests a need for further discoveries in the field.

In this review, we define a subset of undefined AID patients with recurrent inflammatory attacks and systemic manifestations not fulfilling the typical features of PFAPA syndrome, that represents an homogeneous subgroup of patients with recurrent fevers characterized by the classical triad of pharyngitis, cervical lymph nodes enlargement and aphthosis [25]. Fever is the physiological reaction to an increased concentration of inflammatory cytokines in the blood during an inflammatory response. This systemic inflammation often requires systemic drugs, such as specific cytokine blockers or other therapies able to prevent the unbalanced inflammatory response.

Among these drugs, colchicine is an ancient and well known agent. Colchicine acts as a cytoskeleton stabilizer with an evident efficacy in some HRF, namely FMF [29]. A similar effect has been shown in the present review in the majority of SURF patients treated with this drug [9]. The clinical definition of SURF as a well-defined and homogeneous clinical entity may be useful to further investigate the molecular basis of the role of the cytoskeleton in the activation and regulation of the inflammatory response. Furthermore, future studies may delineate novel treatments able to control the clinical manifestations of SURF.

This literature review has a number of limitations. First, the variability of the inclusion criteria used in the different analysed studies is associated with a relevant heterogeneity of the studied populations. Notably, in some studies, the exclusion of non-autoinflammatory syndrome was not formally specified. Finally, the not-homogeneous distribution of genes included in the different NGS panels cannot exclude that some patients could harbour mutations of some genes related to AID not covered by the panel used for that study. It is worth noting, however, that in all the analysed studies, the NGS panel included at least the four genes most frequently associated with HRF, namely MEFV, MVK, TNFRSF1A and NLRP3.

In conclusion, we reviewed the literature data regarding an emerging group of patients with recurrent fevers distinct from HRF and PFAPA syndrome, now defined as SURF. According to the analysis of the literature, a set of the clinical variables that could help to distinguish SURF from PFAPA and HRF can be empirically proposed (Table 3). A proper statistical analysis comparing a homogeneous group of SURF patients with patients with HRF and PFAPA will allow the creation of evidence-based classification criteria for SURF, with the final aim of favoring the harmonization of future studies in the fascinating field of AID still without a precise clinical and molecular characterization.

Table 3.

Proposed empirical indications for the clinical suspicion of SURF.

| Mandatory features |

|---|

| Recurrent fever with elevated inflammatory markers 1 |

| Negative criteria for PFAPA 2 |

| Negative genotype for HRF 3 |

| Additional supporting features |

| Monthly attacks |

| Attacks duration of 3–5 days |

| Fatigue/malaise |

| Arthralgia/myalgia |

| Abdominal pain |

| Eye manifestations 4 |

| Continuous colchicine/anti-IL1 response 5 |

1 at least 3 similar episodes of fever of unknown origin in 6 months; 2 according to the modified Marshall’s and/or Eurofever criteria. 3 not conclusive NGS and/or Sanger sequencing of at least the most commonly associated genes (MEFV, MVK, TNFRSF1A, NLRP3). 4 periorbital edema and/or corneal erythema. 5 amelioration of symptoms and/or acute phase reactants. PFAPA, periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis and adenopathy; HRF, hereditary recurrent fever; IL, interleukin.

5. Footnote

The data in this study are derived from a personal interpretation of published data.

Acknowledgments

Several authors of this publication are members of the European Reference Network for Rare Immunodeficiency, Autoinflammatory and Autoimmune Diseases -Project ID No 739543.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm10091963/s1, Table S1: Analysed genes in the studies of the Table 1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.P. and M.G.; methodology, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, R.P.; validation, writing—review and editing, F.P., S.V., D.S., R.C. and M.G.; visualization, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition, M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Italian Ministry of Health.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not required.

Data Availability Statement

All the data of the present review derive from a personal interpretation of published data.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declared no conflict of interest for this study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Broderick L., Hoffman H.M. Pediatric Recurrent Fever and Autoinflammation from the Perspective of an Allergist/Immunologist. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020;146:960–966.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rusmini M., Federici S., Caroli F., Grossi A., Baldi M., Obici L., Insalaco A., Tommasini A., Caorsi R., Gallo E., et al. Next-Generation Sequencing and Its Initial Applications for Molecular Diagnosis of Systemic Auto-Inflammatory Diseases. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2016;75:1550–1557. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papa R., Rusmini M., Volpi S., Caorsi R., Picco P., Grossi A., Caroli F., Bovis F., Musso V., Obici L., et al. Next Generation Sequencing Panel in Undifferentiated Autoinflammatory Diseases Identifies Patients with Colchicine-Responder Recurrent Fevers. Rheumatology. 2020;59:344–360. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orange D.E., Yao V., Sawicka K., Fak J., Frank M.O., Parveen S., Blachere N.E., Hale C., Zhang F., Raychaudhuri S., et al. RNA Identification of PRIME Cells Predicting Rheumatoid Arthritis Flares. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:218–228. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandrakasan S., Chiwane S., Adams M., Fathalla B.M. Clinical and Genetic Profile of Children with Periodic Fever Syndromes from a Single Medical Center in South East Michigan. J. Clin. Immunol. 2014;34:104–113. doi: 10.1007/s10875-013-9960-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Pieri C., Vuch J., De Martino E., Bianco A.M., Ronfani L., Athanasakis E., Bortot B., Crovella S., Taddio A., Severini G.M., et al. Genetic Profiling of Autoinflammatory Disorders in Patients with Periodic Fever: A Prospective Study. Pediatr. Rheumatol. Online J. 2015;13:11. doi: 10.1186/s12969-015-0006-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakayama M., Oda H., Nakagawa K., Yasumi T., Kawai T., Izawa K., Nishikomori R., Heike T., Ohara O. Accurate Clinical Genetic Testing for Autoinflammatory Diseases Using the Next-Generation Sequencing Platform MiSeq. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2017;9:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrep.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Omoyinmi E., Standing A., Keylock A., Price-Kuehne F., Melo Gomes S., Rowczenio D., Nanthapisal S., Cullup T., Nyanhete R., Ashton E., et al. Clinical Impact of a Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing Gene Panel for Autoinflammation and Vasculitis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0181874. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kostik M.M., Suspitsin E.N., Guseva M.N., Levina A.S., Kazantseva A.Y., Sokolenko A.P., Imyanitov E.N. Multigene Sequencing Reveals Heterogeneity of NLRP12-Related Autoinflammatory Disorders. Rheumatol. Int. 2018;38:887–893. doi: 10.1007/s00296-018-4002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karacan İ., Balamir A., Uğurlu S., Aydın A.K., Everest E., Zor S., Önen M.Ö., Daşdemir S., Özkaya O., Sözeri B., et al. Diagnostic Utility of a Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing Gene Panel in the Clinical Suspicion of Systemic Autoinflammatory Diseases: A Multi-Center Study. Rheumatol. Int. 2019;39:911–919. doi: 10.1007/s00296-019-04252-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ozyilmaz B., Kirbiyik O., Koc A., Ozdemir T.R., Kaya Ozer O., Kutbay Y.B., Erdogan K.M., Saka Guvenc M., Ozturk C. Molecular Genetic Evaluation of NLRP3, MVK and TNFRSF1A Associated Periodic Fever Syndromes. Int. J. Immunogenet. 2019;46:232–240. doi: 10.1111/iji.12431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hua Y., Wu D., Shen M., Yu K., Zhang W., Zeng X. Phenotypes and Genotypes of Chinese Adult Patients with Systemic Autoinflammatory Diseases. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2019;49:446–452. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2019.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boursier G., Rittore C., Georgin-Lavialle S., Belot A., Galeotti C., Hachulla E., Hentgen V., Rossi-Semerano L., Sarrabay G., Touitou I. Positive Impact of Expert Reference Center Validation on Performance of Next-Generation Sequencing for Genetic Diagnosis of Autoinflammatory Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2019;8:1729. doi: 10.3390/jcm8101729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suspitsin E.N., Guseva M.N., Kostik M.M., Sokolenko A.P., Skripchenko N.V., Levina A.S., Goleva O.V., Dubko M.F., Tumakova A.V., Makhova M.A., et al. Next Generation Sequencing Analysis of Consecutive Russian Patients with Clinical Suspicion of Inborn Errors of Immunity. Clin. Genet. 2020;98:231–239. doi: 10.1111/cge.13789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sözeri B., Demir F., Sönmez H.E., Karadağ Ş.G., Demirkol Y.K., Doğan Ö.A., Doğanay H.L., Ayaz N.A. Comparison of the Clinical Diagnostic Criteria and the Results of the Next-Generation Sequence Gene Panel in Patients with Monogenic Systemic Autoinflammatory Diseases. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05492-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hidaka Y., Fujimoto K., Matsuo N., Koga T., Kaieda S., Yamasaki S., Nakashima M., Migita K., Nakayama M., Ohara O., et al. Clinical Phenotypes and Genetic Analyses for Diagnosis of Systemic Autoinflammatory Diseases in Adult Patients with Unexplained Fever. Mod. Rheumatol. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1080/14397595.2020.1784542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kosukcu C., Taskiran E.Z., Batu E.D., Sag E., Bilginer Y., Alikasifoglu M., Ozen S. Whole Exome Sequencing in Unclassified Autoinflammatory Diseases: More Monogenic Diseases in the Pipeline? Rheumatology. 2020 doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang W., Yu Z., Gou L., Zhong L., Li J., Ma M., Wang C., Zhou Y., Ru Y., Sun Z., et al. Single-Center Overview of Pediatric Monogenic Autoinflammatory Diseases in the Past Decade: A Summary and Beyond. Front. Immunol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.565099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Demir F., Doğan Ö.A., Demirkol Y.K., Tekkuş K.E., Canbek S., Karadağ Ş.G., Sönmez H.E., Ayaz N.A., Doğanay H.L., Sözeri B. Genetic Panel Screening in Patients with Clinically Unclassified Systemic Autoinflammatory Diseases. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020;39:3733–3745. doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rama M., Mura T., Kone-Paut I., Boursier G., Aouinti S., Touitou I., Sarrabay G. Is Gene Panel Sequencing More Efficient than Clinical-Based Gene Sequencing to Diagnose Autoinflammatory Diseases? A Randomized Study. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2021;203:105–114. doi: 10.1111/cei.13511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ter Haar N.M., Eijkelboom C., Cantarini L., Papa R., Brogan P.A., Kone-Paut I., Modesto C., Hofer M., Iagaru N., Fingerhutová S., et al. Eurofever registry and the Pediatric Rheumatology International Trial Organization (PRINTO). Clinical Characteristics and Genetic Analyses of 187 Patients with Undefined Autoinflammatory Diseases. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2019;78:1405–1411. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Pauli S., Lega S., Pastore S., Grasso D.L., Bianco A.M.R., Severini G.M., Tommasini A., Taddio A. Neither Hereditary Periodic Fever nor Periodic Fever, Aphthae, Pharingitis, Adenitis: Undifferentiated Periodic Fever in a Tertiary Pediatric Center. World J. Clin. Pediatr. 2018;7:49–55. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v7.i1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garg S., Wynne K., Omoyinmi E., Eleftheriou D., Brogan P. Efficacy and Safety of Anakinra for Undifferentiated Autoinflammatory Diseases in Children: A Retrospective Case Review. Rheumatol. Adv. Pract. 2019;3:rkz004. doi: 10.1093/rap/rkz004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harrison S.R., McGonagle D., Nizam S., Jarrett S., van der Hilst J., McDermott M.F., Savic S. Anakinra as a Diagnostic Challenge and Treatment Option for Systemic Autoinflammatory Disorders of Undefined Etiology. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e86336. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.86336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas K.T., Feder H.M., Lawton A.R., Edwards K.M. Periodic Fever Syndrome in Children. J. Pediatr. 1999;135:15–21. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(99)70321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gattorno M., Hofer M., Federici S., Vanoni F., Bovis F., Aksentijevich I., Anton J., Arostegui J.I., Barron K., Ben-Cherit E., et al. Eurofever Registry and the Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation (PRINTO). Classification Criteria for Autoinflammatory Recurrent Fevers. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2019;78:1025–1032. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masters S.L., Simon A., Aksentijevich I., Kastner D.L. Horror Autoinflammaticus: The Molecular Pathophysiology of Autoinflammatory Disease (*) Ann. Rev. Immunol. 2009;27:621–668. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papa R., Picco P., Gattorno M. The Expanding Pathways of Autoinflammation: A Lesson from the First 100 Genes Related to Autoinflammatory Manifestations. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 2020;120:1–44. doi: 10.1016/bs.apcsb.2019.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Papa R., Penco F., Volpi S., Gattorno M. Actin Remodeling Defects Leading to Autoinflammation and Immune Dysregulation. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:604206. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.604206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data of the present review derive from a personal interpretation of published data.