Abstract

The Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) caused the “COVID-19” disease that has been declared by WHO as a global emergency. The pandemic, which emerged in China and widespread all over the world, has no specific treatment till now. The reported antiviral activities of isoflavonoids encouraged us to find out its in silico anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity. In this work, molecular docking studies were carried out to investigate the interaction of fifty-nine isoflavonoids against hACE2 and viral Mpro. Several other in silico studies including physicochemical properties, ADMET and toxicity have been preceded. The results revealed that the examined isoflavonoids bound perfectly the hACE-2 with free binding energies ranging from −24.02 to −39.33 kcal mol−1, compared to the co-crystallized ligand (−21.39 kcal mol–1). Furthermore, such compounds bound the Mpro with unique binding modes showing free binding energies ranging from −32.19 to −50.79 kcal mol–1, comparing to the co-crystallized ligand (binding energy = −62.84 kcal mol–1). Compounds 33 and 56 showed the most acceptable affinities against hACE2. Compounds 30 and 53 showed the best docking results against Mpro. In silico ADMET studies suggest that most compounds possess drug-likeness properties.

Keywords: COVID-19, isoflavonoids, molecular docking, human ACE2, main protease

1. Introduction

In December 2019, an outbreak of severe pneumonia caused by the novel severe SARS-CoV-2 originated in Wuhan, China. The infection spread all over the world causing coronavirus disease (COVID-19) [1,2]. By October 2020, COVID-19 caused more than 33 million infections and more than 1 million deaths according to the WHO [3]. Unfortunately, till now there is no specific antiviral drug available for the treatment of COVID-19-infected people. However, some drugs such as remdesivir showed modest activity through decreasing the mortality rate and treatment time [4].

Mpro is an essential non-structural chymotrypsin-like cysteine proteases enzyme for the replication of coronavirus. It works on two large polyproteins (PP1a and PP1ab) releasing 16 essential non-structural proteins (NSPs 1-16) [5,6].

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE-2) is a crucial enzyme in the renin-angiotensin system. It is a significant target for antihypertensive drugs [7]. It is primarily expressed in renal tubular epithelium and vascular endothelium cells [8]. It was also reported to be expressed in lungs and GIT, tissues shown to harbor SARS-CoV [9,10]. The binding of SARS-CoV-2 to ACE-2 receptors was reported to play a pivotal role in the first binding step at the cellular membrane [11]. SARS-CoV-2 entry was mediated by its transmembrane spike glycoprotein [12]. ACE-2 was identified as the cellular receptor to which spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 binds [13]. Several reports confirmed that the SARS-CoV-2 infects human cells through ACE-2 receptor [11,14]. Furthermore, it was found that the overexpression of ACE-2 in a living cell facilitates virus entry [15].

Natural secondary metabolites are a major source of anti-infective drugs. These metabolites could be originated from plants [16,17], marine [18,19], or microbial sources [20,21,22], and found to belong to various types such as saponins [23,24], alkaloids [25], pyrones [26], isochromenes [27], diterpenes[28], flavonoids [29,30], and isoflavonoids [31].

The isoflavonoids are an important polyphenolic subclass of the flavonoids with a skeleton based on a 3-phenylchroman structure [32]. The antiviral power of several isoflavonoid secondary metabolites has been proven in several scientific reports before. Torvanol A is a sulfated isoflavonoid isolated from the fruits of Solanum torvum and exhibited antiviral activity against herpes simplex virus type 1 with an IC50 value of 9.6 μg mL−1 [33]. Genistein; the major isoflavonoid of soybean seeds inhibited HSV-1 (KOS and 29R strains), and HSV-2 (333 strain) replications with IC50 values of 14.02, 7.76 and 14.12, respectively. In addition, three isoflavone glycosides were obtained from some hypocotyls of soybean seeds and could completely inhibit HIV-induced cytopathic effects and virus-specific antigen expression just six days after infection at a concentration of 0.25 mg mL−1 [34]. Daidzein was reported to inhibit the influenza virus at an IC50 of 51.2 µM [35].

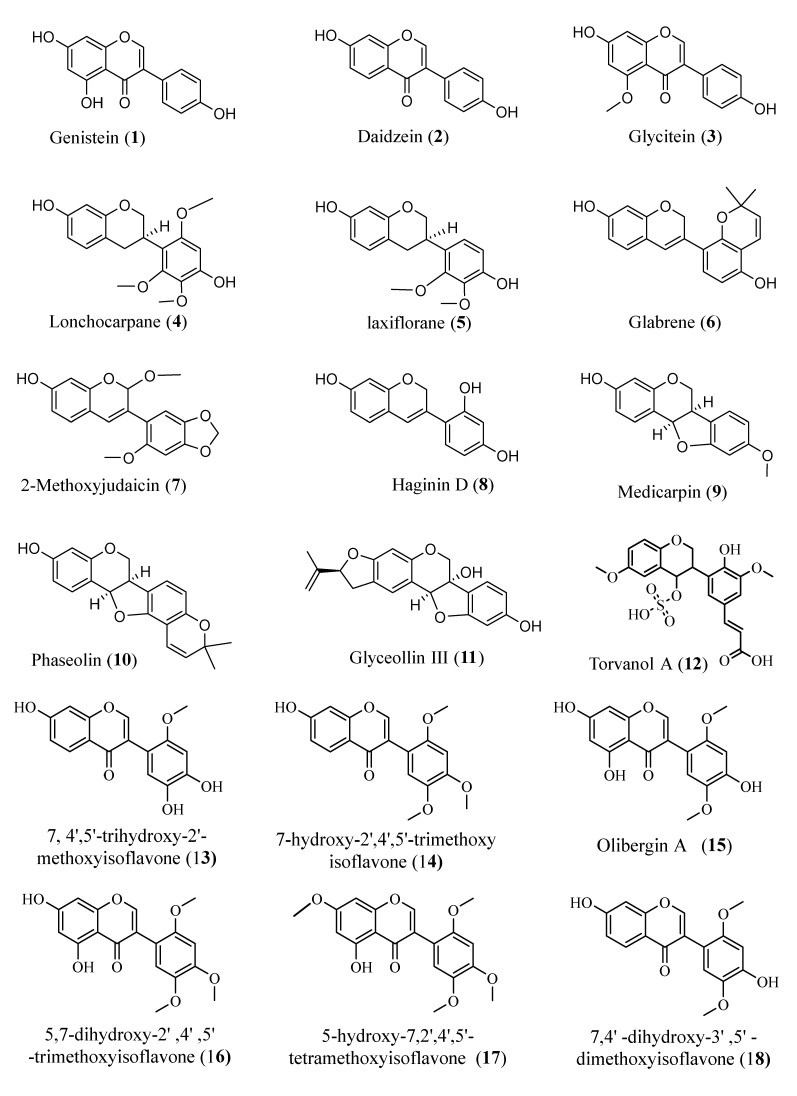

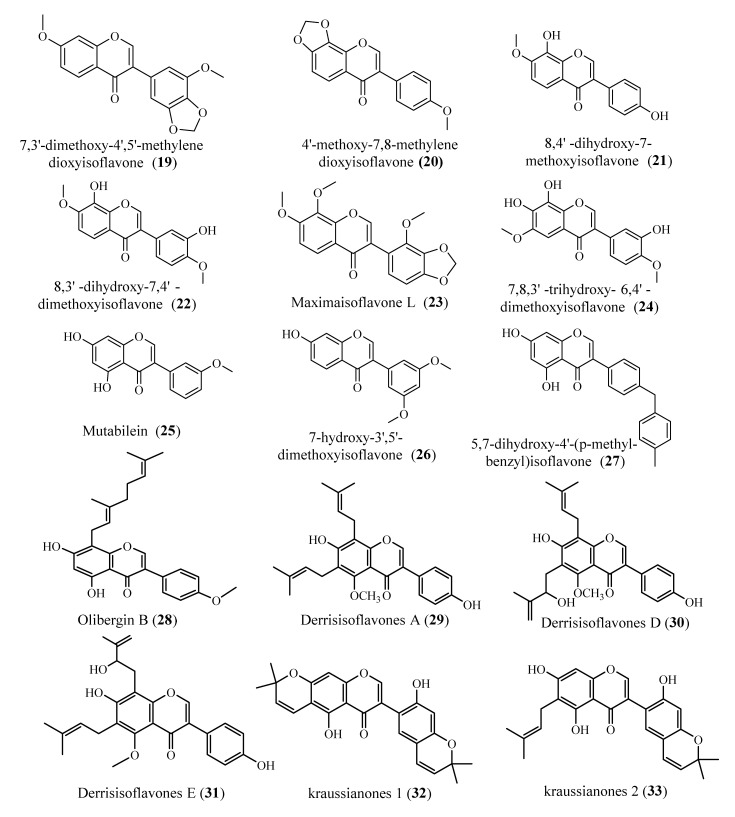

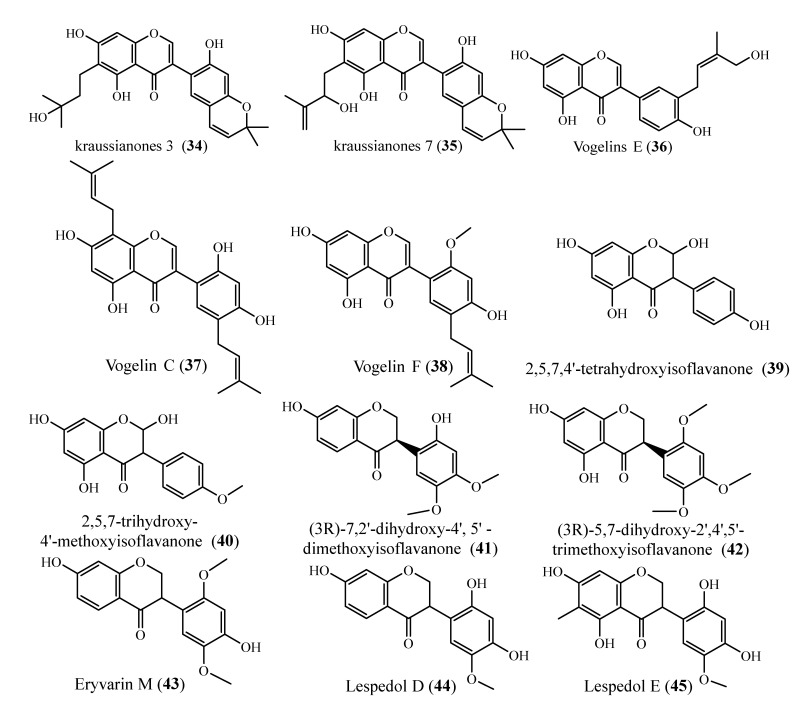

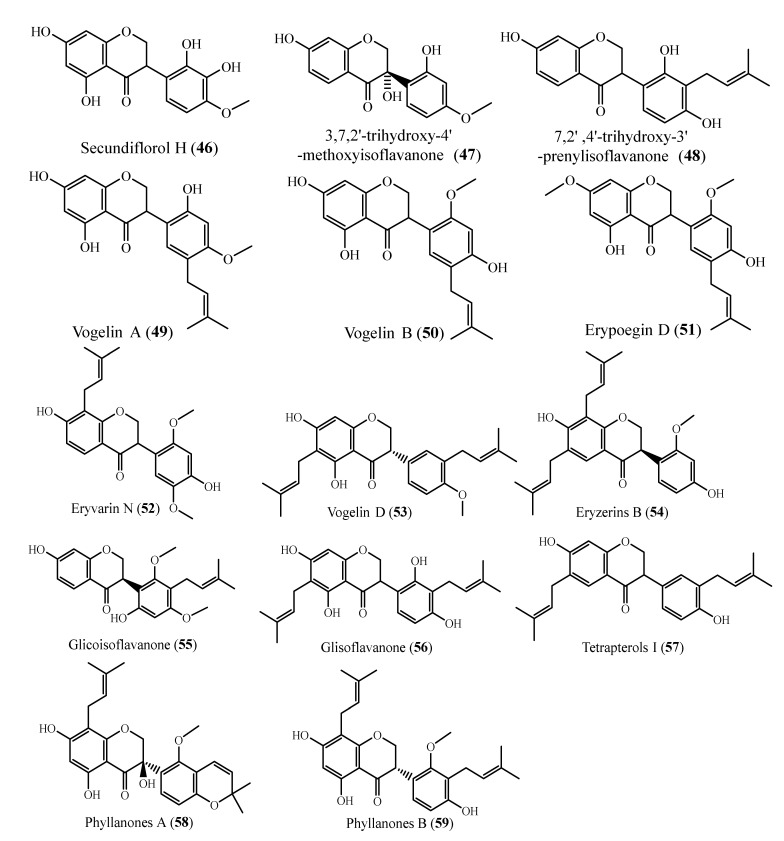

Furthermore, homoisoflavonoids showed great antiviral activity against the enteroviruses, Coxsackievirus B1, B3, B4, A9 and echovirus 30 [36]. Interestingly, a group of synthesized substituted homo-isoflavonoids exhibited promising inhibitory effects against human rhinovirus (HRV) 1B and 14 [37]. These findings inspired us to explore the potential of fifty-nine isoflavonoids (1–59) (Figure 1) as a possible treatment for COVID-19 through in silico examination of their potential to bind with ACE-2 and Mpro receptors.

Figure 1.

Structures of the examined isoflavonoids.

2. Experimental

Drug-likeness properties were calculated using Lipinski’s rule of five, which suggested that the absorption of an orally administered compound is more likely to be better if the molecule satisfies at least three of the following rules: (i) H bond donors (OH, NH, and SH) ≤5; (ii) H bond acceptors (N, O, and S atoms) ≤10; (iii) molecular weight <500; (iv) logP <5. Compounds violating more than one of these rules could not have good oral bioavailability [38]. The pharmacokinetic properties (ADMET) of isoflavonoids and adherence with Lipinski’s rule of five were calculated using Discovery studio 4.0 software(Accelrys software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) [39].

The title molecules were investigated with the aid of docking studies using Discovery Studio 4.0 software (Accelrys software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) for their binding capabilities against ACE-2 and Mpro. The crystal structures of the target proteins were acquired from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 6LZG, resolution: 2.50 Å [40] and 6LU7, resolution: 2.16 Å [41] for ACE-2 and Mpro, respectively). the co-crystallized ligands 2-acetamido-2-deoxy-β-D-glucopyranose (NAG) and N-[(5-methylisoxazol-3-yl)carbonyl]alanyl-l-valyl-N~1~-((1R,2Z)-4-(benzyloxy)-4-oxo-1-{[(3R)-2-oxopyrrolidin-3-yl]methyl}but-2-enyl)-l-leucinamide (N3) were used as reference molecules against hACE-2 and Mpro, respectively.

At first, water molecules were removed from the complex. Using the valence monitor method, the incorrect valence atoms were corrected. The energy minimization was then accomplished through the application of force fields CHARMM and MMFF94 [42,43,44,45]. The binding sites were defined and prepared for docking processes. Structures of the tested isoflavonoids and the co-crystallized ligands were sketched using ChemBioDraw Ultra 14.0 (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) [46] and saved as MDL-SD files. Next, the MDL-SD files were opened, 3D structures were protonated, and energy was minimized by implementing force fields CHARMM and MMFF94, then adjusted for docking. CDOCKER protocol was used for docking studies using CHARMM-based molecular dynamics (MD) to dock the co-crystallized ligands into a receptor binding site [47,48]. In the docking studies, a total of 10 conformers were considered for each molecule. Finally, according to the minimum free energy of binding interaction, the most ideal pose was chosen.

The toxicity parameters for the examined compounds were calculated using Discovery studio 4.0 software (Accelrys software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Simeprevir was used as a reference drug. At first, the CHARMM force field was applied then the compounds were prepared and minimized according to the preparation of small molecule protocol. Then different parameters were calculated from the toxicity prediction (extensible) protocol.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Pharmacokinetic Profiling Study

3.1.1. Lipinski’s Rule of Five

In the present study, an in silico computational study of compounds (1–59) was performed to determine their physicochemical properties according to the directions of Lipinski’s rule of five [38] (Table 1).

Table 1.

physicochemical properties of the tested isoflavonoids.

| Comp. | Lipinski’s Rule of Five | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log P a | Molecular Wight | HBD b | HBA c | |

| 1 | 2.14 | 270.23 | 3 | 5 |

| 2 | 2.38 | 254.23 | 2 | 4 |

| 3 | 2.36 | 284.26 | 2 | 5 |

| 4 | 3.16 | 332.34 | 2 | 6 |

| 5 | 3.17 | 302.32 | 2 | 5 |

| 6 | 3.81 | 322.35 | 2 | 4 |

| 7 | 3.09 | 328.31 | 1 | 6 |

| 8 | 2.78 | 256.25 | 3 | 4 |

| 9 | 2.68 | 270.28 | 1 | 4 |

| 10 | 3.48 | 322.35 | 1 | 4 |

| 11 | 3.23 | 338.35 | 2 | 5 |

| 12 | −1.50 | 450.41 | 1 | 10 |

| 13 | 2.12 | 300.26 | 3 | 6 |

| 14 | 2.57 | 328.31 | 1 | 6 |

| 15 | 2.10 | 330.28 | 3 | 7 |

| 16 | 2.33 | 344.31 | 2 | 7 |

| 17 | 2.55 | 358.34 | 1 | 7 |

| 18 | 2.34 | 314.28 | 2 | 6 |

| 19 | 2.60 | 326.3 | 0 | 6 |

| 20 | 2.61 | 296.27 | 0 | 5 |

| 21 | 2.36 | 284.26 | 2 | 5 |

| 22 | 2.34 | 314.28 | 2 | 6 |

| 23 | 2.58 | 356.32 | 0 | 7 |

| 24 | 2.10 | 330.28 | 3 | 7 |

| 25 | 2.36 | 284.26 | 2 | 5 |

| 26 | 2.59 | 298.2 | 1 | 5 |

| 27 | 4.84 | 358.38 | 2 | 4 |

| 28 | 6.04 | 420.49 | 2 | 5 |

| 29 | 6.07 | 420.49 | 2 | 5 |

| 30 | 5.03 | 436.49 | 3 | 6 |

| 31 | 5.03 | 436.49 | 3 | 6 |

| 32 | 3.95 | 418.43 | 2 | 6 |

| 33 | 4.78 | 420.45 | 3 | 6 |

| 34 | 3.68 | 438.4 | 4 | 7 |

| 35 | 3.73 | 436.45 | 4 | 7 |

| 36 | 2.90 | 354.35 | 4 | 6 |

| 37 | 5.61 | 422.4 | 4 | 6 |

| 38 | 3.9 | 368.38 | 3 | 6 |

| 39 | 1.91 | 288.25 | 4 | 6 |

| 40 | 2.14 | 302.27 | 3 | 6 |

| 41 | 2.46 | 316.3 | 2 | 6 |

| 42 | 2.44 | 346.33 | 2 | 7 |

| 43 | 2.465 | 316.3 | 2 | 6 |

| 44 | 2.24 | 302.27 | 3 | 6 |

| 45 | 2.48 | 332.3 | 4 | 7 |

| 46 | 1.99 | 318.278 | 4 | 7 |

| 47 | 1.88 | 302.27 | 3 | 6 |

| 48 | 4.11 | 340.37 | 3 | 5 |

| 49 | 4.09 | 370.39 | 3 | 6 |

| 50 | 4.09 | 370.39 | 3 | 6 |

| 51 | 4.32 | 384.422 | 2 | 6 |

| 52 | 4.32 | 384.42 | 2 | 6 |

| 53 | 6.19 | 422.51 | 2 | 5 |

| 54 | 6.19 | 422.51 | 2 | 5 |

| 55 | 4.32 | 384.42 | 2 | 6 |

| 56 | 5.72 | 424.48 | 4 | 6 |

| 57 | 6.21 | 392.48 | 2 | 4 |

| 58 | 4.52 | 452.49 | 3 | 7 |

| 59 | 5.95 | 438.51 | 3 | 6 |

a Partition coefficient; b Hydrogen bond donors; c Hydrogen bond acceptors.

It was found that almost all the tested isoflavonoids followed Lipinski’s rule of five and hence display a drug-like molecular (DLM) nature. The Log P, molecular weight, number of H-bond donors and number of H-bond acceptors of all isoflavonoids are within the accepted values (less than 5, 500, 5 and 10, respectively). with exceptions of compounds (28, 29, 53, 54 and 57) that have log p values of 6.04, 6.07, 6.19, 6.19 and 6.21, respectively.

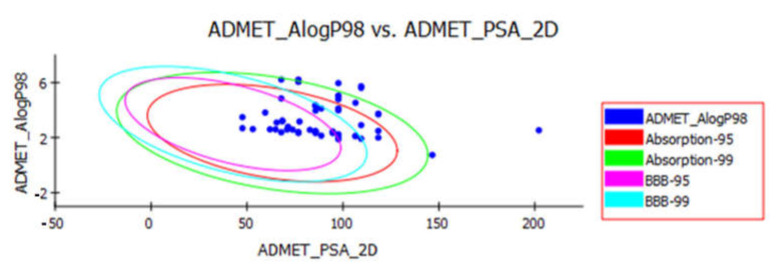

3.1.2. ADMET Studies

Discovery studio 4.0 software was used to predict ADMET descriptors (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and toxicity) for the selected isoflavonoids using remdesivir as a reference drug. The predicted ADMET parameters of the tested compounds were listed in Table 2. The BBB penetration levels of 6, 10 and 27 were expected to be high. On the other hand, the expected BBB penetration levels of all other isoflavonoids were ranging from medium to low. These results indicate that most of the tested compounds would be less likely to penetrate the CNS.

Table 2.

Predicted ADMET descriptors for the tested isoflavonoids and remdesivir.

| Compound | BBB Level a | Absorption Level b | PPB c | Solubility Level d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 5 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 8 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 9 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 10 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 11 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 12 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| 13 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 14 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 15 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 16 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 17 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 18 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 19 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 20 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 21 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 22 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 23 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 24 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 25 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 26 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 27 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 28 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 29 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| 30 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 31 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 32 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 33 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 34 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 35 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 36 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 37 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 38 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 39 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 40 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 41 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 42 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 43 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 44 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 45 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 46 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 47 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 48 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 49 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 50 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 51 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 52 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 53 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 54 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 55 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 56 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 57 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| 58 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 59 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Remdesivir | 4 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

a BBB level, blood brain barrier level, 0 = very high, 1 = high, 2 = medium, 3 = low, 4 = very low. b Absorption level, 0 = good, 1 = moderate, 2 = poor, 3 = very poor. c PBB, plasma protein binding, 0 means less than 90%, 1 means more than 90%, 2 means more than 95%. d solubility level, 0 = extremely low, 1 = very low, 2 = low, 3 = good, 4 = optimal.

The plasma protein binding model predicts the binding ability of a ligand with plasma proteins which affects its efficiency. The results revealed that compounds 1, 2, 5, 9, 10, 14, 15, 18, 19, 23–31, 37, 41, 42, 44, 45, 49, 52–54, 56, 57 and 59 were expected to bind plasma protein by more than 95%, while 3, 8, 13, 16, 17, 20–22, 33, 39, 40, 48, 50, 51, 55 and 58 showed a binding pattern of more than 90%. Contrastingly, compounds 4, 6, 7, 11, 12, 32, 34, 35, 38, 43, 46 and 47 were expected to bind the plasma protein less than 90%.

Moreover, all the tested isoflavonoids were predicted to have good absorption behavior better than that of remdesivir. Also, the solubility levels of most compounds were expected to be in the good range (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The expected ADMET study of the designed compounds and remdesivir.

3.2. Molecular Docking

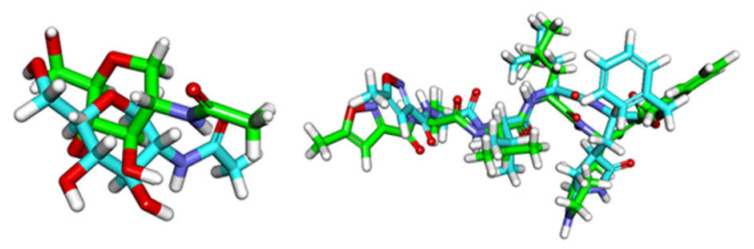

3.2.1. Validation Process

Validation of the docking procedures was achieved via re-docking of the co-crystallized ligands against the active pocket of hACE2 and Mpro. The calculated RMSD values between the re-docked poses and the co-crystallized ones were 2.4 and 2.8 Å. Such values of RMSD indicated the efficiency and validity of the docking processes (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Superimposition of the co-crystallized poses (green) and the docking pose (maroon) of the same ligands. (Left): hACE2 (RMSD = 2.4 Å), (right): Mpro (RMSD = 2.8 Å).

3.2.2. HACE2

Coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with its receptor hACE-2 (PDB: 6LZG) used as a target for the docking studies of selected isoflavonoids. The results demonstrated that all isoflavonoids bound strongly to hACE-2 with binding energies bitter than that of the co-crystallized ligand (NAG). This indicated that the affinity of the tested isoflavonoids toward hACE-2 is higher than that of the co-crystallized ligand (Table 3). Moreover, almost all the tested isoflavonoids exhibited binding modes similar to that of NAG.

Table 3.

Free binding energies of the selected isoflavonoids and the co-crystallized ligand (NAG) against hACE-2 and amino acid residues involved in H. bonds and hydrophobic interaction.

| Comp. | Binding Energy (kcal mol−1) | No. of H. Bonds | Involved Amino Acid Residues | Amino Acid Residues Involved in Hydrophobic inTeraction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −30.90 | 2 | Ser371, Asn343 | Phe374, Gly339, Ser371, Phe338, Phe342 |

| 2 | −27.84 | 1 | Ser371 | Phe338, Phe342, Gly339 |

| 3 | −28.13 | 1 | Ser371 | Phe374, Phe342, Phe338, Gly339 |

| 4 | −25.52 | 1 | Ser371 | Phe374, Phe342, Phe338, Gly339 |

| 5 | −24.12 | 1 | Ser371 | Phe374, Phe342, Phe338, Leu368, Gly339 |

| 6 | −26.14 | 1 | Ser371 | Phe342, Phe338, Phe374 |

| 7 | −25.95 | 1 | Ser371 | Phe342, Phe338, Phe374 |

| 8 | −27.41 | 2 | Ser371, Asn343 | Phe374, Phe342, Phe338 |

| 9 | −22.32 | 1 | Ser371 | Phe374, Phe342, Phe338 |

| 10 | −23.66 | 0 | 0 | Phe374, Phe342, Phe338, Ser371, Gly339 |

| 11 | −24.02 | 1 | Ser371 | Phe374, Phe342, Phe338 |

| 12 | −31.01 | 2 | Asp364 | Phe338, Ser371, Leu368, Cys336, Phe374, Val367 |

| 13 | −27.85 | 0 | 0 | Asn343, Ser371, Leu368, Cys336, Phe374, Val367 |

| 14 | −25.17 | 1 | Cys336 | Phe338, Ser371, Ser373, Leu368, Cys336, Phe374, Val367 |

| 15 | −27.52 | 1 | Cys336 | Phe374, Phe342, Ser371, Leu368, Cys336, Val367 |

| 16 | −27.42 | 1 | Cys336 | Ser371, Leu368, Cys336, Phe374, Val367, Gly339 |

| 17 | −25.02 | 1 | Trp436 | Phe374, Leu368, Val367, Phe342 |

| 18 | −23.37 | 1 | Cys336 | Phe338, Leu368, Cys336, Phe342, Val367, Asn343 |

| 19 | −30.52 | 1 | Gly339 | Phe374, Phe338, Ser371, Gly339, Cys336, Leu368, Val367 |

| 20 | −29.50 | 0 | 0 | Phe374, Phe338, Ser371, Cys336, Leu368, Val367 |

| 21 | −24.10 | 0 | 0 | Phe338, Ser371, Cys336, Leu368, Val367, Phe374 |

| 22 | −28.66 | 1 | Cys336 | Asn434, Phe338, Ser371, Cys336, Leu368, Val367 |

| 23 | −33.20 | 0 | 0 | Phe338, Ser371, Cys336, Leu368, Val367, Ser373 |

| 24 | −32.74 | 2 | Ser371, Cys336 | Phe374, Phe338, Gly339, Cys336, Ser371, Leu368, Phe432 |

| 25 | −24.43 | 1 | Ser373 | Gly339, Leu368, Phe338, Ser371, Cys336 |

| 26 | −27.27 | 1 | Ser373 | Asn343, Gly339, Leu368, Phe338, Ser371, Cys336 |

| 27 | −30.81 | 1 | Cys336 | Phe374, Phe338, Ser371, Cys336, Leu368, Val367, Phe342, Asn343 |

| 28 | −29.91 | 0 | 0 | Leu368, Val367, Phe342, Asn343, Cys336, Phe338, Ser371, |

| 29 | −32.76 | 2 | Ser371, Cys336 | Phe374, Phe338, Ser371, Val367, Cys336, Leu368, Ser373 |

| 30 | −29.12 | 2 | Asn343, Cys336 | Phe338, Ser371, Gly339, Cys336, Leu368, Ser373, Asn343 |

| 31 | −30.84 | 1 | Asn364 | Cys336, Leu368, Ser373, Asn343, Val362, Asn364 |

| 32 | −33.95 | 0 | 0 | Phe338, Val367, Cys336, Leu368, Ser373, Asn440, Asn364 |

| 33 | −36.35 | 1 | Ser371 | Phe374, Phe342, Ser371, Asn343, Cys336, Glu340, Ser373 |

| 34 | −39.33 | 1 | Asp364 | Phe338, Phe342, Asn343, Val367, Asp364, Cys336, Leu335, Leu386 |

| 35 | −34.48 | 3 | Cys336, Gly339, Glu340 | Phe374, Phe338, Val367, Cys336, Leu368, Ser373, Gly339, Glu340 |

| 36 | −34.80 | 2 | Cys336, Gly339 | Phe338, Leu335, Asn343, Ser373 |

| 37 | −34.37 | 2 | Ser371, Ser373 | Leu368, Ser371, Asn343, Ser373, Phe338, Phe342 |

| 38 | −30.09 | 2 | Cys336, Gly339 | Phe338, Leu335, Cys336, Gly339, Asn343, Ser373 |

| 39 | −25.26 | 1 | Ser371 | Phe374, Phe338, Ser371, Val367, Cys336, Leu368, Ser373 |

| 40 | −23.32 | 1 | Ser373 | Phe338, Val367, Cys336, Leu368, Ser373 |

| 41 | −29.16 | 1 | Cys336 | Cys336, Phe338, Val367, Leu368, Ser373 |

| 42 | −32.12 | 1 | Ser371 | Phe374, Val367, Cys336, Leu368, Ser373, Phe338, Ser371, |

| 43 | −27.79 | 1 | Ser371 | Phe374, Phe338, Ser371, Val367, Cys336, Leu368 |

| 44 | −27.53 | 1 | Ser373 | Phe338, Phe374, Val367, Cys336, Leu368, Ser373 |

| 45 | −31.39 | 1 | Cys336 | Cys336, Phe342, Val367, Leu368, Gly339, Asp364 |

| 46 | −30.09 | 2 | Cys336, Gly339 | Phe338, Leu335, Cys336, Gly339, Asn343, Ser373 |

| 47 | −25.11 | 0 | 0 | Phe338, Asn343, Cys336, Leu368, Ser373 |

| 48 | −34.79 | 1 | Cys336 | Cys336, Asn343, Phe338, Val367, Leu368, Ser373 |

| 49 | −31.79 | 1 | Cys336 | Phe338, Asn343, Cys336, Leu368, Val367 |

| 50 | –30.39 | 1 | Cys336 | Cys336, Phe338, Val367, Leu368, Ser373 |

| 51 | −30.81 | 1 | Ser371 | Phe342, Asn343, Phe374, Ser371, Leu368 |

| 52 | −29.33 | 1 | Gly339 | Phe338, Leu335, Cys336, Gly339, Val367, Asn343, Ser373 |

| 53 | −33.34 | 1 | Ser373 | Phe338, Phe374, Val367, Cys336, Leu368, Ser373 |

| 54 | −35.10 | 0 | 0 | Ser371, Ser373, Phe338, Leu335, Cys336 |

| 55 | −29.06 | 1 | Cys336 | Cys336, Phe342, Val367, Leu335, Ser371, Asn343 |

| 56 | −34.90 | 2 | Ser371, Cys336 | Phe374, Phe338, Ser371, Val367, Cys336, Leu368, Ser373 |

| 57 | −34.77 | 0 | 0 | Ser373, Phe338, Phe342, Cys336, Gly339 |

| 58 | −30.22 | 1 | Ser371 | Phe342, Asn343, Phe374, Ser371, Leu368 |

| 59 | −34.70 | 1 | Ser371 | Ser373, Asn343, Phe374, Ser371, Leu368, Val367, Leu335 |

| NAG | −21.39 | 1 | Ser371. | Phe374, Phe342, Phe338 |

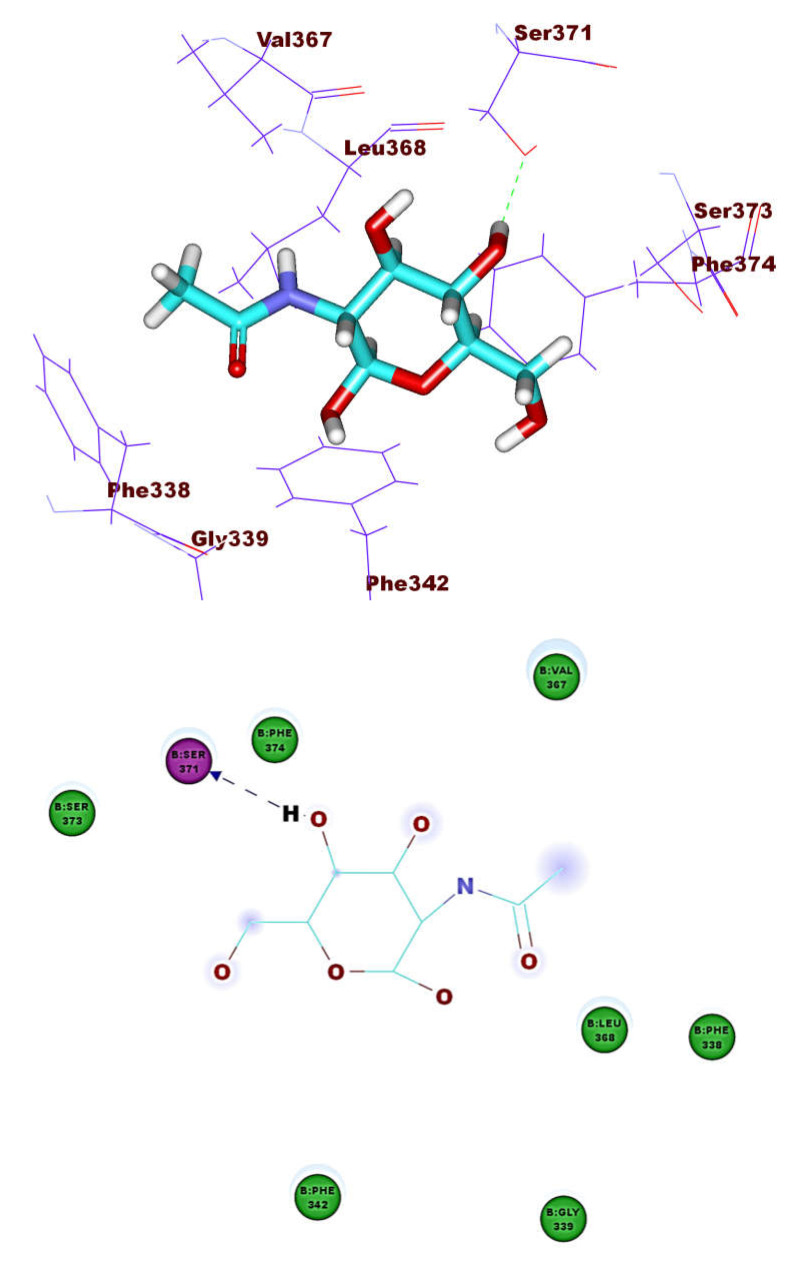

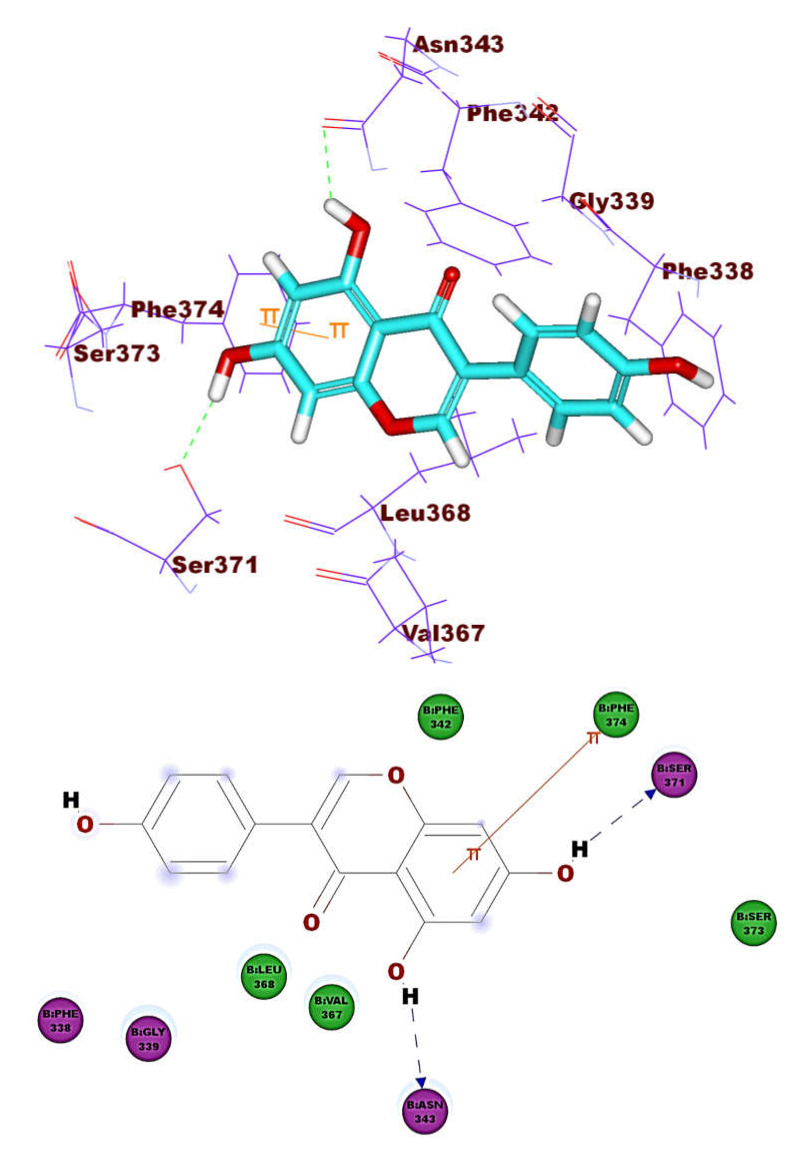

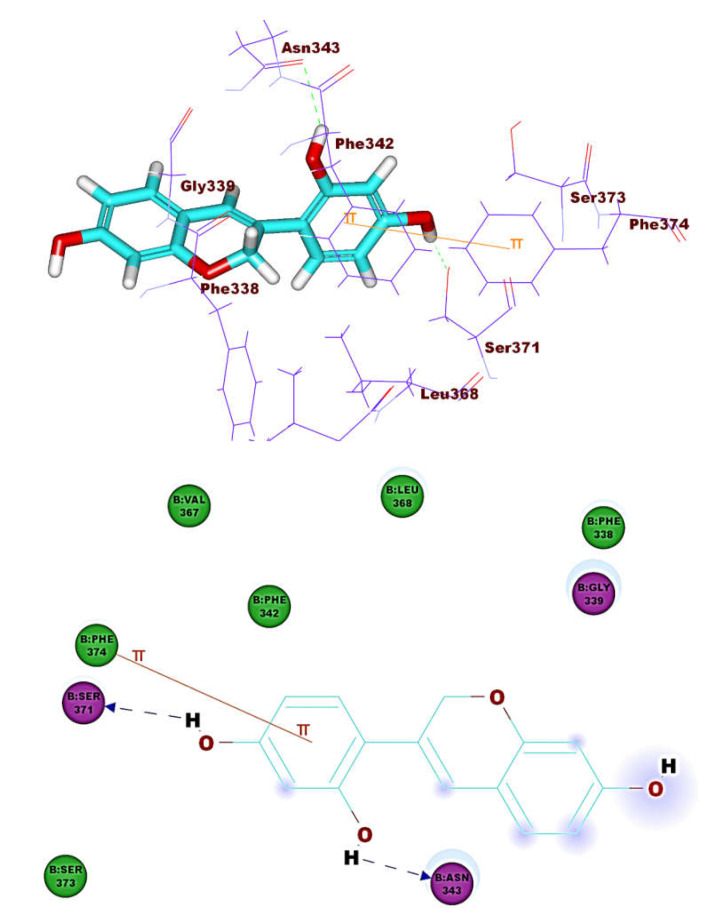

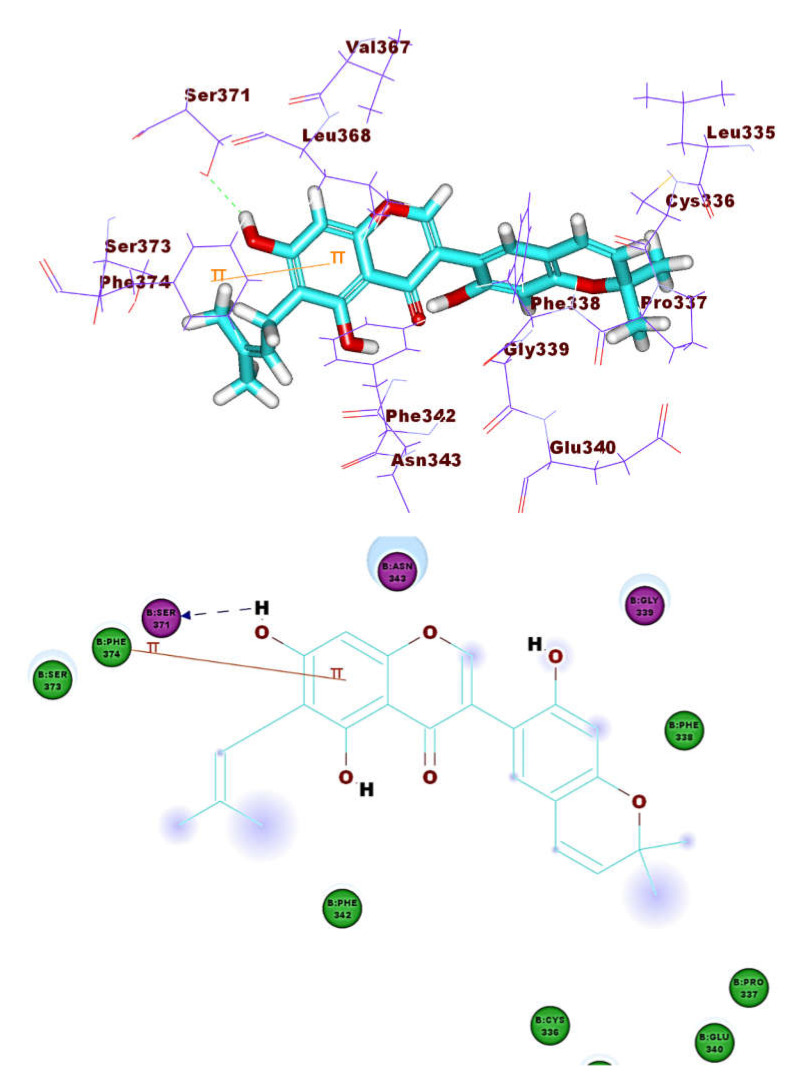

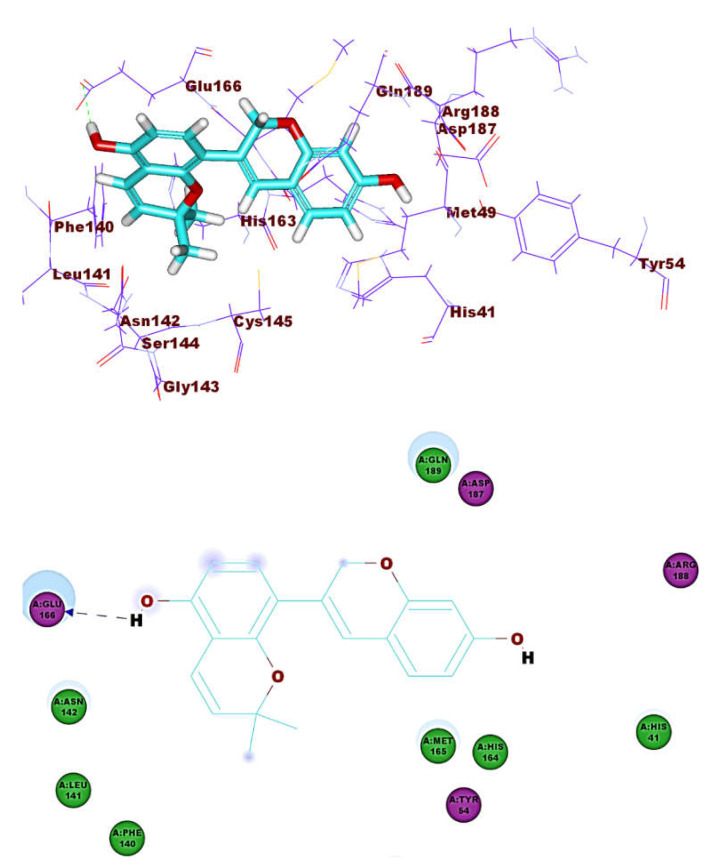

The binding pattern of co-crystallized ligand (NAG) demonstrated single hydrogen bonding interaction with Ser371 residue (Figure 4). NAG showed binding energies of −21.39 kcal mol−1. It was found that most of the tested isoflavonoids exhibited binding modes similar to the reference molecule. Compounds 1 (−30.90 kcal mol–1) and 8 (−27.41 kcal mol−1) demonstrated an additional hydrogen bond with Asn343 residue (Figure 5 and Figure 6). This extra hydrogen bond may account for the relatively high binding affinity of both compounds. Furthermore, compounds 33 (Figure 7) and 56 (Figure 8) were found to have good binding energy values of −36.35 and −34.90 kcal mol−1, respectively. Compound 33 formed a binding mode like that of the reference ligand as it formed one hydrogen bond with Ser371 and seven hydrophobic interactions with Phe374, Phe342, Ser371, Asn343, Cys336, Glu340, and Ser373. Interestingly, compound 56 formed two hydrogen bonds with Ser371 and Cys336 in addition to seven hydrophobic interactions with Phe374, Phe338, Ser371, Val367, Cys336, Leu368, and Ser373.

Figure 4.

The co-crystallized ligand (NAG) docked into ACE-2, forming one H. bond with Ser371.

Figure 5.

Compound 1 docked into ACE-2, forming two H. bonds with Ser371 and Asn343.

Figure 6.

Comound 8 docked into ACE-2, forming two H. bonds with Ser371 and Asn343.

Figure 7.

Compound 33 docked into ACE-2, forming one H. bond with Ser371.

Figure 8.

Compound 56 docked into ACE-2, forming two H. bonds with Ser371 and Cys336.

Such results indicate the significance of the tested isoflavonoids as potential inhibitors for hACE-2. Consequently, such compounds may inhibit the entrance of coronavirus into human cells.

3.2.3. Main Protease (Mpro)

The docking results of isoflavonoids into the active site of coronavirus Mpro (PDB: 6LU7) were listed in Table 4. The results showed that all tested isoflavonoids can bind to Mpro with one or more hydrogen bonds. At the same time, the tested compounds bound to the receptor with free binding energies ranging from −32.19 to −50.79 kcal mol−1, compared to the co-crystallized (binding energy = −62.84 kcal mol−1).

Table 4.

Free binding energies of studied isoflavonoids and ligand to coronavirus Mpro and amino acid residues involved in H. bonds and hydrophobic interaction.

| Comp. | Binding Energy (kcal mol−1) | No. of H. Bonds | Involved Amino Acid Residues |

Amino Acid Residues Involved in Hydrophobic Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −37.38 | 1 | Glu166 | Phe140, Leu141, Gln189, His41, Tyr54, Glu166 |

| 2 | −35.91 | 1 | Phe140 | Phe140, Leu141, Gln189, His41, Tyr54, Glu166 |

| 3 | −36.08 | 1 | Glu166 | Phe140, Leu141, Gln189, His41, Tyr54, Glu166 |

| 4 | −37.99 | 1 | Glu166 | Phe140, Leu141, Gln189, His41, Tyr54, Glu166 |

| 5 | −38.45 | 2 | Thr190, Leu141 | Phe140, Leu141, Gln189, His41, Tyr54, Glu166 |

| 6 | −41.41 | 1 | Glu166 | Phe140, Leu141, Asn142, His163, Tyr54, Glu166 |

| 7 | −40.11 | 1 | Glu166 | Phe140, His172, Glu166, His163, His164, Gln189 |

| 8 | −42.73 | 3 | Glu166, Cys145, His163 | Phe140, Leu141, Glu166, His163, His164, Gln189 |

| 9 | −33.98 | 1 | Phe140. | Phe140, Leu141, Gln189, His41, Tyr54, Glu166 |

| 10 | −35.25 | 2 | Glu166, Phe140. | Phe140, Leu141, Gln189, His41, Tyr54, Glu166 |

| 11 | −32.19 | 1 | Glu 166 | Phe140, Leu141, Gln189, His41, Tyr54, Glu166 |

| 12 | −41.55 | 3 | Gln192, His41, Arg188 | Glu166, Met 165, Gln192, His41, His164, His172 |

| 13 | −40.51 | 1 | Glu 166 | Met 165, Cys145, His41, Asn142, Glu166 |

| 14 | −39.89 | 1 | Glu 166 | His163, Met 165, Cys145, His41, Glu189, Glu166 |

| 15 | −37.34 | 1 | Glu166 | Phe140, Met 165, Asp187, His41, Glu189, Glu166 |

| 16 | −39.05 | 6 | Glu166, Cys145, Thr26 | Glu166, Cys145, Thr26, His41, Met 165, Glu189, Leu27 |

| 17 | −40.60 | 1 | Gly143 | Glu166, Cys145, Thr26, His4, Met 165, Gln189, Gln192 |

| 18 | −35.58 | 0 | 0 | Glu166, Phe140, Gly143, Asp187, Met 165, Gln189 |

| 19 | −37.26 | 0 | 0 | Glu166, Phe140, Cys145, Asp142, Met 165, Gln189 |

| 20 | −34.97 | 1 | Glu 166 | Phe140, Gln189, His41, Ser144, Tyr54, Glu166 |

| 21 | −38.42 | 1 | Phe140 | Phe140, Leu141, Gln189, His41, Met165, Leu140, Glu166 |

| 22 | −40.14 | 1 | Phe140 | Phe140, Leu141, Gln189, His164, Met165, Leu140, Glu166 |

| 23 | −40.24 | 0 | 0 | Glu166, Phe140, Leu141, Gln189, His41, Met165, Leu140 |

| 24 | −38.90 | 2 | Phe140, Glu166 | Glu166, Phe140, Leu141, Gln189, His164, Met165, Leu140, Cys145 |

| 25 | −34.43 | 2 | Phe140, Glu166 | Glu166, Phe140, His41, Gln189, His164, Met165, Cys145 |

| 26 | −36.39 | 1 | Phe140 | Glu166, Phe140, His41, Gln189, His164, Met165 |

| 27 | −38.58 | 3 | Gly143, Cys145, Thr26 | Glu166, Gly143, Gln189, Cys145, Thr26, Met165 |

| 28 | −47.62 | 1 | His41 | Glu166, Phe140, His41, Gln189, His164, Met165, Cys145, Leu141 |

| 29 | −49.64 | 3 | Glu166, Tyr54, Asp187 | Phe140, Gln189, His172, Met165, Tyr54, Asp187, Leu167, Glu166 |

| 30 | −48.39 | 3 | Glu166, Tyr54, Asp187 | His41, Gln189, His163, Met165, Tyr54, Asp187, Leu167, Glu166 |

| 31 | −48.32 | 1 | Glu 166 | Phe140, Gln189, His41, Met165, Tyr54, Glu166 |

| 32 | −38.31 | 1 | Cys145 | Gln189, His41, Met165, Cys145, Glu166 |

| 33 | −43.52 | 2 | Gln189, Gly143 | Met165, Gln189, Gly143, Glu166 |

| 34 | −45.48 | 2 | Glu166, Cys145 | Glu166, Phe140, His41, Gln189, His164, Met165, Cys145 |

| 35 | −41.38 | 1 | Gly143 | Glu166, Gly143, Leu107, Gln192, His164, Met165, Cys145 |

| 36 | −42.29 | 4 | His164, Cys145, Ser144, Leu141 | Gln189, His172, Met165, Glu166 His164, Cys145, Ser144, Leu141 |

| 37 | −48.13 | 4 | Met165, Thr190, His41, Cys145 | Glu166, Met165, Thr190, His41, Cys145, Gln189 |

| 38 | −43.30 | 1 | Glu 166 | Gln189, His163, Met165, Ser144, Glu166, Leu167 |

| 39 | −38.05 | 4 | Glu166, Cys145 | Glu166, Cys145, Met165, Asn142 |

| 40 | −36.12 | 2 | Glu166, His163 | Glu166, His163, Phe140, Met165 |

| 41 | −38.22 | 3 | Gln189, Asp187, Tyr54 | Gln189, Met165, His163, Glu166 |

| 42 | −37.17 | 1 | Glu166 | Glu166, Leu141, Gln189, Gly143 |

| 43 | −35.41 | 1 | Asp187 | Glu166, Leu141, Met165, Ser144 |

| 44 | −36.62 | 1 | Glu166 | Gln189, Met165, His172, Glu166, His163 |

| 45 | −40.48 | 4 | Ser144, Cys145, Thr26, Gly143 | Cys145, Thr26, His163, Met165, Asn142 |

| 46 | −40.84 | 1 | His163 | Glu166, His163, Phe140, Met165 |

| 47 | −35.39 | 1 | Glu166 | Glu166, Asn142, His164, Met165 |

| 48 | −40.40 | 1 | His163 | Glu166, Leu141, Met165, Gln189 |

| 49 | −43.83 | 4 | Glu166, Cys145, His41 | Glu166, Cys145, His41, Met165, Asn142, Leu141 |

| 50 | −43.91 | 1 | Glu166 | Glu166, Leu141, Met165, Gln189 |

| 51 | −46.15 | 2 | Glu166 | Glu166, Ser144, Gln189, His41 |

| 52 | −41.20 | 1 | Glu166 | Glu166, Leu141, Met165, Gln189, Asn142 |

| 53 | −46.90 | 2 | Glu166, Phe140 | Glu166, Gln189, Leu141, Met165, His172, Phe140 |

| 54 | −50.79 | 1 | Glu166 | Glu166, Gln189, Leu141, Met165, His172 |

| 55 | −40.56 | 1 | Thr26 | Asn142, Glu166, Asn142, Leu141 |

| 56 | −48.29 | 3 | Glu166, His41 | Glu166, His41, Met165, Asn142, His164 |

| 57 | −49.89 | 2 | Gly143, Arg188 | Glu166, Gln189, Leu141, Met165, His163 |

| 58 | −42.63 | 2 | Glu166, Leu141 | Glu166, Gln189, Leu141, Met165, His172 |

| 59 | −48.11 | 2 | Gly143, Leu141 | Glu166, Gln189, Met165, |

| N3 (Co-crystallized ligand) | −62.84 | 4 | Gln189, Tyr54, Asp142, Asp187. | Phe140, Glu166, His172, Thr190, Gln189, Tyr54, Asp142, Asp187. |

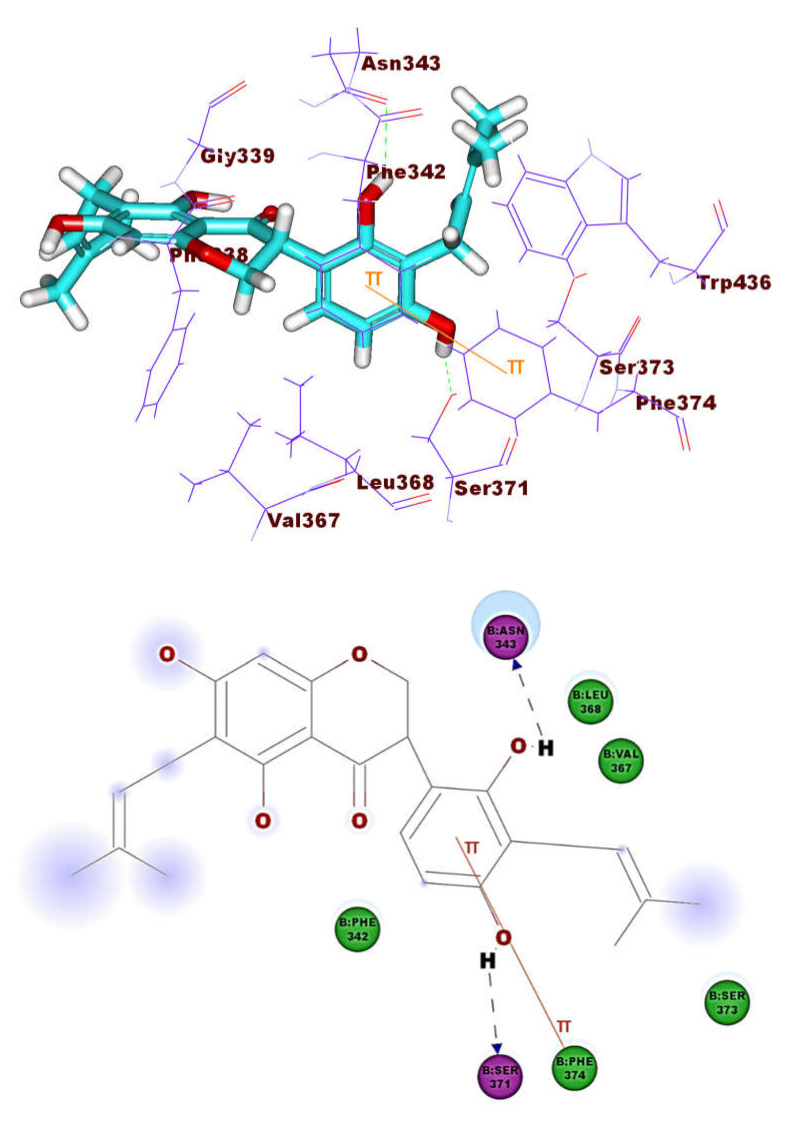

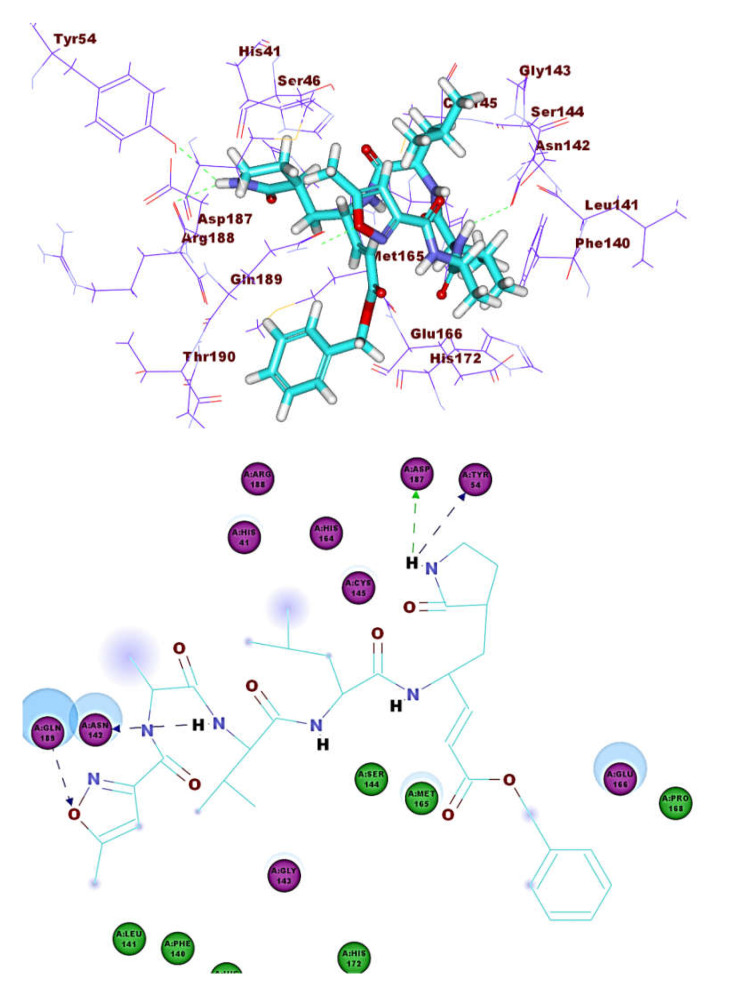

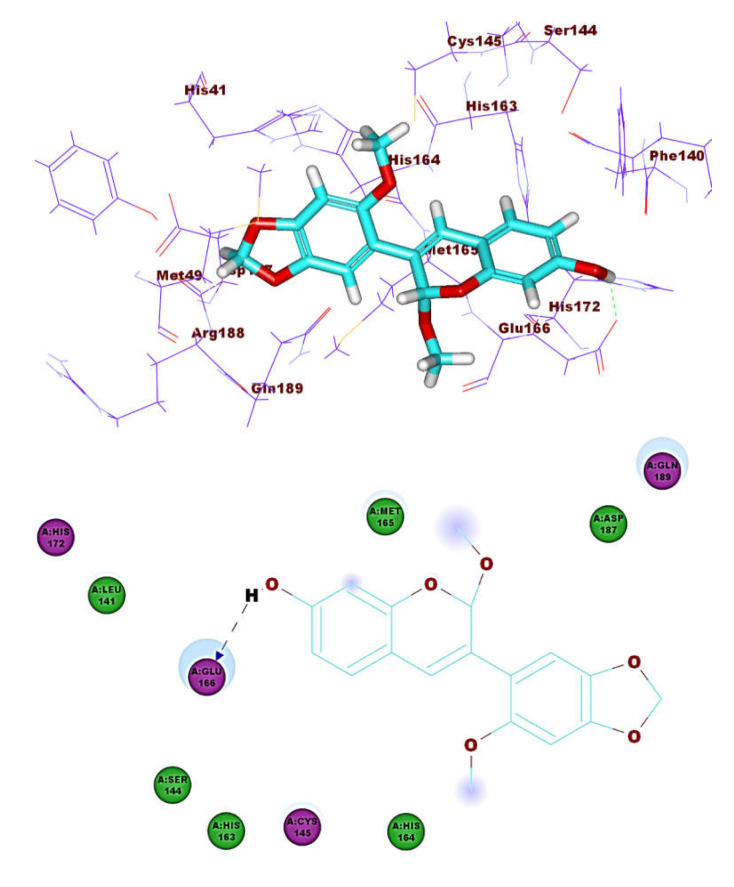

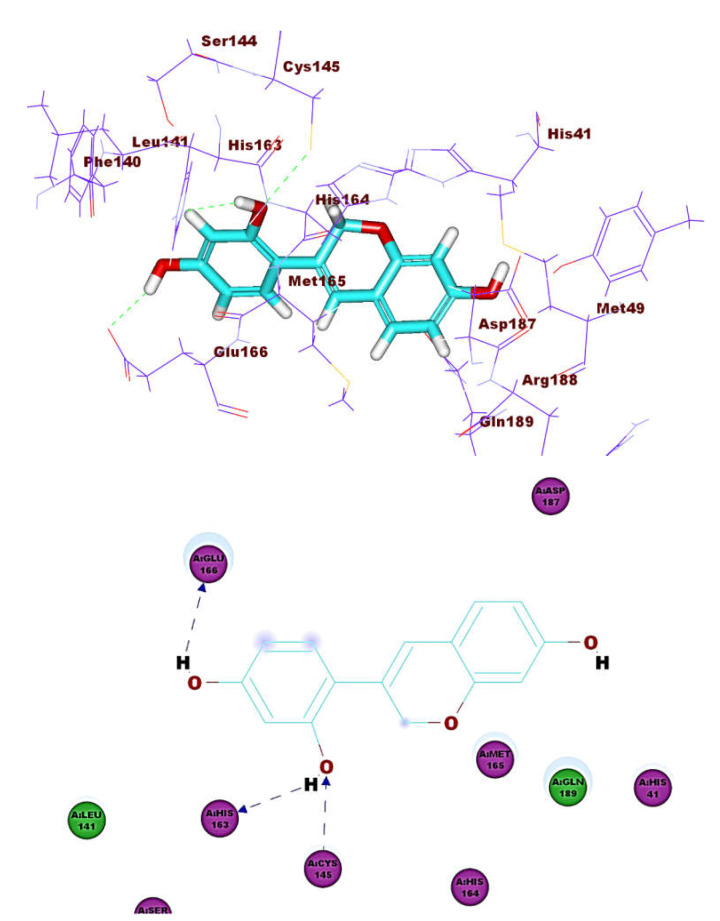

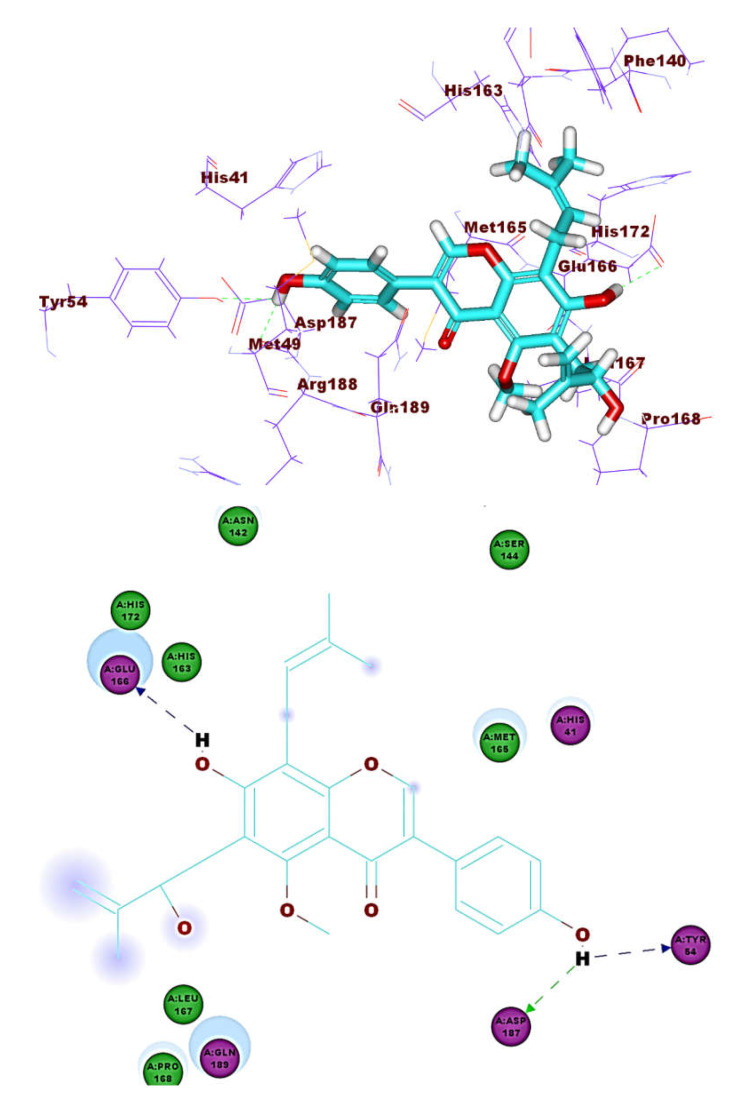

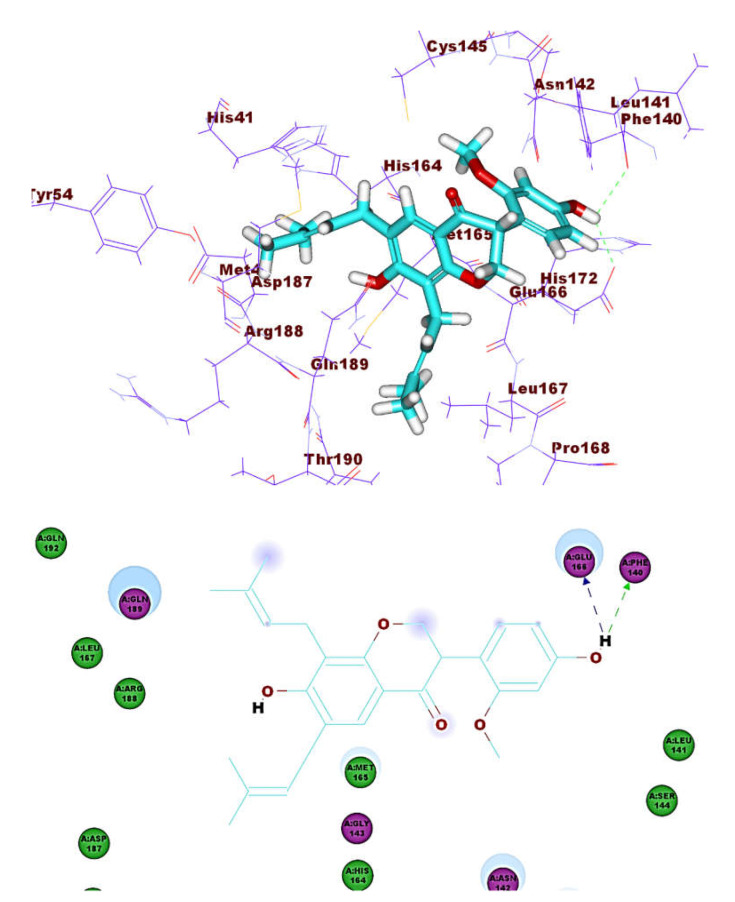

These results revealed that the affinities of the presented isoflavonoids against Mpro are lower than that of N3. Despite that, the binding energies are still considerable, and their binding modes are great which making these isoflavonoids seem to be biologically active ligands to some extent. Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14 illustrate the binding patterns of N3, compound 6 (binding energy = −41.41 kcal mol−1), compound 7 (binding energy = −40.11 kcal mol−1), compound 8 (binding energy = −42.73 kcal mol−1), compound 30 (binding energy = −48.39 kcal mol−1), and compound 53 (binding energy = −46.90 kcal mol−1), respectively.

Figure 9.

The co-crystallized ligand (N3) docked into Mpro, forming four H. bonds with Gln189, Tyr 54, Asp 142, Asp187.

Figure 10.

Compound 6 docked into Mpro, forming one H. bond with Glu166.

Figure 11.

Compound 7 docked into Mpro, forming one H. bond with Glu166.

Figure 12.

Compound 8 docked into Mpro, forming three H. bonds with Glu166, Cys145 and His163.

Figure 13.

Compound 30 docked into Mpro, forming three H. bonds with Glu166, Cys145 and His163.

Figure 14.

Compound 53 docked into Mpro, forming two H. bonds with Glu166, Phe140.

Compound 30 formed a binding mode like that of the reference ligand as it formed three hydrogen bonds with Glu166, Tyr54, and Asp187. Furthermore, it formed eight hydrophobic interactions with His41, Gln189, His163, Met165, Tyr54, Asp187, Leu167, and Glu166. For compound 53, it formed two hydrogen bonds with Glu166, Phe140. Besides, it formed six hydrophobic interactions with Glu166, Gln189, Leu141, Met165, His172, and Phe140.

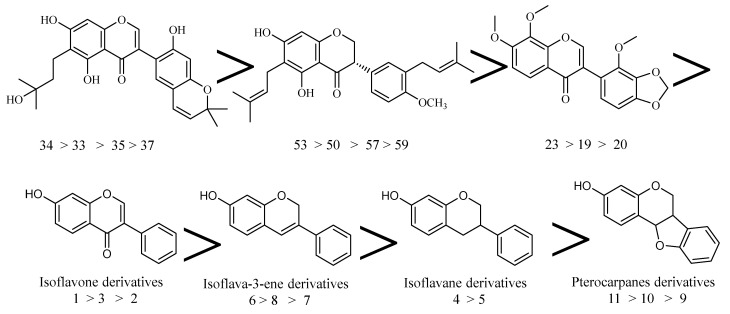

3.2.4. Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR)

Based on the binding affinities of the tested compounds against hACE-2, we can obtain valuable SAR. Generally, the tested compounds showed decreased affinity against hACE-2 in descending order of isoflavone derivatives (compounds 34, 33, 35 and 37) > isoflavane derivatives (compounds 50, 53, 57 and 59) > isoflavone derivatives (compounds 19, 20 and 23) > isoflavone derivatives (compounds 1–3) > isoflava-3-ene derivatives (compounds 6–8) > isoflavane derivatives (compounds 4 & 5) > pterocarpanes derivatives (compounds 9–11) (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Schematic diagram showing the different affinities of isoflavonoids against hACE-2.

For isoflavone derivatives (compounds 34, 33, 35 and 37), it was found that compound 34 incorporating 3-hydroxy-3-methylbutyl moiety at 6-position was more active that compound 33 incorporating 3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl moiety at the same position. The latter was more active than compound 35 incorporating 2-hydroxy-3-methylbut-3-en-1-yl moiety at the same position. Compound 37 incorporating 3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl moiety at 8-position was less active than the corresponding members.

With regard to isoflavane derivatives (compounds 50, 53, 57 and 59), it was found that 3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl moiety is critical for binding affinity. compound 50 incorporating this moiety at 3- and 6-positions of 4-chromanone nucleus was more active than compound 53 incorporating this moiety at 5-position of phenyl ring. The latter was more active than compound 57 incorporating 3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl moiety at both 6-position position of 4-chromanone nucleus and 3-position of phenyl ring. Compound 59 incorporating 3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl moiety at both 8-position position of 4-chromanone nucleus and 3-position of phenyl ring was less active than the corresponding members.

Regarding isoflavone derivatives (compounds 19, 20, and 23), it was found that the presence of 1,3-dioxole moiety can affect the affinity depending on it position. compound 19 incorporating 1,3-dioxole moiety at 3,4-positions of phenyl ring was more active than compound 20 incorporating this moiety at 7,8-position of 4H-chromen-4-one nucleus. The latter was more active than compound 23 incorporating 1,3-dioxole moiety at 4,5-position position of phenyl ring.

Then, we investigated the effect of substitutions at isoflavone derivatives on the binding affinity. It was found that the substitutions at 5-position with hydroxyl (compound 1) and methoxy (compound 3) group, increase the binding of isoflavones against hACE-2, with an increased affinity of hydroxyl derivative.

Regarding the effect of substitutions at isoflava-3-ene, it was found that the derivative with additional pyran ring (compound 6) was more active than the corresponding member with free OH group at position-1 of phenyl ring (compound 8) which was more potent than compound 7 incorporating a dioxolan ring.

Observing binding affinities of isoflavane derivatives. It was found that compound 4 incorporating an additional methoxy group at 6 position of phenyl ring showed better binding affinity against hACE-2 than the unsubstituted derivative (compound 5). Such a result may be attributed to the electron donating effect of the methoxy group.

Concerning the activity of different pterocarpan derivatives, it was noted that compound 11, which contained an additional tetrahydrofuran ring attached to the chromene ring, showed better binding affinity inside the hACE-2 than compounds 9 and 10, which contained free OH groups at the chromene ring.

3.3. Toxicity Studies

Toxicity prediction was carried out based on the validated and constructed models in Discovery studio 4.0 software [49,50] as follows. (i) FDA rodent carcinogenicity test which computes the probability of a compound to be a carcinogen. (ii) Carcinogenic potency TD50 which predicts the tumorigenic dose rate 50 (TD50) of a drug in a rodent chronic exposure toxicity test of carcinogenic potency [51]. (iii) Rat maximum tolerated dose (MTD) [52,53]. (iv) Rat oral LD50 which predicts the rat oral acute median lethal dose (LD50) of a chemical [54]. (v) Rat chronic LOAEL which predicts the rat chronic lowest observed adverse effect level (LOAEL) value [55,56]. (vi) Ocular irritancy predicts whether a particular compound is likely to be an ocular irritant and how severe the irritation is in the Draize test [57]. (vii) Skin irritancy predicts whether a particular compound is likely to be a skin irritant and how severe it is in a rabbit skin irritancy test [57].

As shown in Table 5, most compounds showed in silico low toxicity against the tested models. FDA rodent carcinogenicity model indicated that most of the tested compounds are non-carcinogens. Only compounds 6, 9, and 10 were predicted to be carcinogens so that, these compounds do not have the likeness to be used as drugs.

Table 5.

Toxicity properties of isoflavonoids (1–59) and semiprever.

| Comp. | FDA Rodent Carcinogenicity | Carcinogenic Potency TD50 (Rat) a |

Rat MTD (Feed) b |

Rat Oral LD50 c | Rat Chronic LOAEL d | Ocular Irritancy | Skin Irritancy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Non-Carcinogen | 60.47 | 0.516 | 1.40 | 0.107 | Irritant | None |

| 2 | Non-Carcinogen | 67.14 | 0.334 | 1.41 | 0.089 | Irritant | None |

| 3 | Non-Carcinogen | 10.43 | 0.225 | 0.81 | 0.068 | Irritant | None |

| 4 | Non-Carcinogen | 5.69 | 0.231 | 0.17 | 0.072 | Irritant | None |

| 5 | Non-Carcinogen | 5.73 | 0.234 | 0.17 | 0.071 | Irritant | None |

| 6 | Carcinogen | 35.33 | 0.239 | 0.77 | 0.024 | Irritant | None |

| 7 | Non-Carcinogen | 6.23 | 0.096 | 0.48 | 0.019 | Irritant | None |

| 8 | Non-Carcinogen | 33.45 | 0.529 | 1.06 | 0.074 | Irritant | Mild |

| 9 | Carcinogen | 4.43 | 0.122 | 0.14 | 0.027 | Irritant | Mild |

| 10 | Carcinogen | 28.52 | 0.126 | 0.16 | 0.011 | Irritant | None |

| 11 | Non-Carcinogen | 7.51 | 0.192 | 0.55 | 0.015 | Irritant | None |

| 12 | Non-Carcinogen | 193.96 | 0.078 | 0.10 | 0.004 | Mild | None |

| 13 | Non-Carcinogen | 5.27 | 0.255 | 1.07 | 0.865 | Mild | None |

| 14 | Non-Carcinogen | 9.10 | 0.164 | 1.13 | 0.325 | Mild | None |

| 15 | Non-Carcinogen | 7.32 | 0.288 | 2.03 | 0.147 | Mild | None |

| 16 | Non-Carcinogen | 7.91 | 0.230 | 1.67 | 0.155 | Mild | None |

| 17 | Non-Carcinogen | 8.98 | 0.184 | 1.18 | 0.152 | None | None |

| 18 | Non-Carcinogen | 8.40 | 0.205 | 1.69 | 0.309 | Mild | None |

| 19 | Non-Carcinogen | 0.77 | 0.069 | 0.39 | 0.130 | None | Mild |

| 20 | Non-Carcinogen | 0.59 | 0.061 | 0.20 | 0.145 | None | Mild |

| 21 | Non-Carcinogen | 6.40 | 0.181 | 1.44 | 0.229 | Mild | None |

| 22 | Non-Carcinogen | 5.73 | 0.205 | 2.36 | 0.390 | Mild | None |

| 23 | Non-Carcinogen | 0.44 | 0.077 | 0.42 | 0.282 | Mild | Mild |

| 24 | Non-Carcinogen | 6.88 | 0.288 | 4.66 | 0.863 | Mild | None |

| 25 | Non-Carcinogen | 19.50 | 0.181 | 0.97 | 0.191 | None | None |

| 26 | Non-Carcinogen | 10.75 | 0.145 | 1.01 | 0.281 | Mild | None |

| 27 | Non-Carcinogen | 29.81 | 0.184 | 1.74 | 0.054 | Mild | None |

| 28 | Non-Carcinogen | 19.03 | 0.199 | 0.77 | 0.035 | None | None |

| 29 | Non-Carcinogen | 25.03 | 0.080 | 0.35 | 0.055 | Severe | None |

| 30 | Non-Carcinogen | 2.33 | 0.097 | 0.45 | 0.039 | Severe | None |

| 31 | Non-Carcinogen | 2.33 | 0.097 | 0.45 | 0.039 | Severe | None |

| 32 | Non-Carcinogen | 20.46 | 0.128 | 0.26 | 0.074 | Mild | None |

| 33 | Non-Carcinogen | 73.66 | 0.197 | 0.29 | 0.013 | Mild | Mild |

| 34 | Non-Carcinogen | 25.44 | 0.526 | 0.92 | 0.018 | Severe | None |

| 35 | Non-Carcinogen | 6.87 | 0.236 | 0.37 | 0.013 | Mild | None |

| 36 | Non-Carcinogen | 322.42 | 0.764 | 0.84 | 0.029 | Severe | None |

| 37 | Non-Carcinogen | 165.35 | 0.303 | 1.39 | 0.008 | Mild | None |

| 38 | Non-Carcinogen | 19.21 | 0.153 | 0.46 | 0.024 | Mild | None |

| 39 | Non-Carcinogen | 35.43 | 0.576 | 0.70 | 0.012 | Severe | None |

| 40 | Non-Carcinogen | 4.926 | 0.216 | 0.44 | 0.015 | Mild | None |

| 41 | Non-Carcinogen | 6.31 | 0.381 | 0.98 | 0.075 | Severe | None |

| 42 | Non-Carcinogen | 5.95 | 0.428 | 0.71 | 0.026 | Mild | None |

| 43 | Non-Carcinogen | 6.31 | 0.381 | 0.91 | 0.044 | Mild | None |

| 44 | Non-Carcinogen | 5.81 | 0.475 | 1.12 | 0.041 | Mild | None |

| 45 | Non-Carcinogen | 5.28 | 0.402 | 0.76 | 0.037 | Mild | None |

| 46 | Non-Carcinogen | 3.25 | 0.668 | 1.10 | 0.174 | Mild | None |

| 47 | Non-Carcinogen | 4.02 | 0.395 | 0.65 | 0.084 | None | None |

| 48 | Non-Carcinogen | 126.90 | 0.545 | 0.39 | 0.009 | Severe | None |

| 49 | Non-Carcinogen | 14.44 | 0.284 | 0.32 | 0.024 | Mild | None |

| 50 | Non-Carcinogen | 14.44 | 0.284 | 0.20 | 0.008 | Mild | None |

| 51 | Non-Carcinogen | 16.34 | 0.226 | 0.14 | 0.008 | Mild | None |

| 52 | Non-Carcinogen | 21.43 | 0.226 | 0.46 | 0.010 | Mild | None |

| 53 | Non-Carcinogen | 18.79 | 0.150 | 0.34 | 0.008 | Mild | None |

| 54 | Non-Carcinogen | 18.79 | 0.150 | 0.26 | 0.007 | Mild | None |

| 55 | Non-Carcinogen | 14.61 | 0.226 | 0.32 | 0.053 | Severe | None |

| 56 | Non-Carcinogen | 116.75 | 0.562 | 0.42 | 0.006 | Severe | None |

| 57 | Non-Carcinogen | 177.62 | 0.291 | 0.36 | 0.004 | Severe | None |

| 58 | Non-Carcinogen | 5.28 | 0.156 | 0.18 | 0.016 | Mild | None |

| 59 | Non-Carcinogen | 15.21 | 0.208 | 0.35 | 0.014 | Mild | None |

| Simeprevir | Non-Carcinogen | 0.28 | 0.003 | 0.21 | 0.002 | Irritant | None |

a TD 50, tumorigenic dose rate 50, Unit: mg kg−1 body weight/day; b MTD, maximum tolerated dose, Unit: g kg−1 body weight; c LD50, median lethal dose, Unit: g kg−1 body weight; d LOAEL, lowest observed adverse effect level, Unit: g kg−1 body weight.

For the carcinogenic potency TD50 rat model, the examined compounds showed TD50 values ranging from 0.44 to 322.42 mg Kg−1 body weight/day which are higher than simeprevir (0.280 mg Kg−1 body weight/day).

Regarding the rat MTD model, the compounds showed MTD with a range of 0.061 to 0.764 g kg−1 body weight higher than simeprevir (0.003 g kg−1 body weight).

Concerning the rat oral LD50 model, the tested compounds showed oral LD50 values ranging from 0.10 to 4.66 mg Kg−1 body weight/day), while simeprevir exhibited an oral LD50 value of 0.21 mg Kg–1 body weight/day. About the rat chronic LOAEL model, the compounds showed LOAEL values ranging from 0.004 to 0.865 g kg−1 body weight. These values are higher than simeprevir (0.002 g kg−1 body weight). Moreover, most of the compounds were predicted to be irritant against the ocular irritancy model. On the other hand, the tested compounds were predicted to be mild or non-irritant against the skin irritancy model.

4. Conclusions

There is an urgent global need to find a cure for COVID-19. The present work is an attempt to find some natural compounds with potential activity against COVID-19. Accordingly, docking studies were carried out for fifty-nine isoflavonoid derivatives against two essential targets (hACE-2 and Mpro). The obtained results showed that the tested isoflavonoids can strongly bind the hACE-2 and Mpro with great binding modes. Based on in silico studies, SARs were established. SAR studies afforded an insight into the pharmacophoric groups which may serve as a guide for the design of new potential anti-COVID-19 agents. Generally, the tested compounds showed decreased affinity against hACE-2 in descending order of isoflavone derivatives (compounds 33–35 and 37) > isoflavane derivatives (compounds 50, 53, 57 and 59) > isoflavone derivatives (compounds 19, 20 and 23) > isoflavone derivatives (compounds 1–3) > isoflava-3-ene derivatives (compounds 6–8) > isoflavane derivatives (compounds 4 and 5) > pterocarpan derivatives (compounds 9–11) Finally, compounds 33 and 56 showed the most acceptable affinity against hACE2; compounds 30 and 53 showed the best docking results against Mpro. In addition, these compounds showed good physicochemical and cytotoxicity profiles. Moreover, in silico investigation of physicochemical properties, ADMET and toxicity studies revealed good properties and general low toxicity. Consequently, this study strongly suggests in vitro and in vivo studies for the most active isoflavonoids against COVID-19.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowlege Faculty of Pharmacy (Boys), Al-Azhar Universuty, Cairo, Egypt for computer supply.

Author Contributions

M.S.A.: docking studies, A.E.A.: Data curation and Writing the original draft, M.S.T.: Writing original draft, E.B.E.: Resources, I.H.E.: ADMET and toxicity studies, A.M.M.: Writing-review & editing. I.H.E. and A.M.M.: Designed the idea and supervised the work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding and The APC was funded by AlMaarefa University, Ad Diriyah, Riyadh 13713, Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sample Availability

Samples of the compounds are not available from the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zumla A., Chan J.F., Azhar E.I., Hui D.S., Yuen K.Y. Coronaviruses - drug discovery and therapeutic options. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016;15:327–347. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2015.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Su S., Wong G., Shi W., Liu J., Lai A.C.K., Zhou J., Liu W., Bi Y., Gao G.F. Epidemiology, Genetic Recombination, and Pathogenesis of Coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24:490–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. [(accessed on 2 October 2020)]; Available online: https://covid19.who.int/

- 4.Dolin R., Hirsch M.S. Remdesivir—An Important First Step. Massachusetts Medical Society; Waltham, MA, USA: 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang L., Lin D., Sun X., Curth U., Drosten C., Sauerhering L., Becker S., Rox K., Hilgenfeld R. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved α-ketoamide inhibitors. Science. 2020;368:409–412. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prajapat M., Sarma P., Shekhar N., Avti P., Sinha S., Kaur H., Kumar S., Bhattacharyya A., Kumar H., Bansal S. Drug targets for corona virus: A systematic review. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2020;52:56. doi: 10.4103/ijp.IJP_115_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riordan J.F. Angiotensin-I-converting enzyme and its relatives. Genome Biol. 2003;4:1–5. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-8-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ichihara K.I., Fukubayashi Y. Preparation of fatty acid methyl esters for gas-liquid chromatography. J. Lipid Res. 2010;51:635–640. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D001065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ksiazek T.G., Erdman D., Goldsmith C.S., Zaki S.R., Peret T., Emery S., Tong S., Urbani C., Comer J.A., Lim W. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. New Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1953–1966. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harmer D., Gilbert M., Borman R., Clark K.L. Quantitative mRNA expression profiling of ACE 2, a novel homologue of angiotensin converting enzyme. Febs Lett. 2002;532:107–110. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03640-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan R., Zhang Y., Li Y., Xia L., Guo Y., Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science. 2020;367:1444–1448. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tortorici M.A., Veesler D. Advances in Virus Research. Volume 105. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2019. Structural insights into coronavirus entry; pp. 93–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang J., Petitjean S.J., Koehler M., Zhang Q., Dumitru A.C., Chen W., Derclaye S., Vincent S.P., Soumillion P., Alsteens D. Molecular interaction and inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 binding to the ACE2 receptor. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18319-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H., Penninger J.M., Li Y., Zhong N., Slutsky A.S. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a SARS-CoV-2 receptor: Molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic target. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:586–590. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05985-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jia H.P., Look D.C., Shi L., Hickey M., Pewe L., Netland J., Farzan M., Wohlford-Lenane C., Perlman S., McCray P.B. ACE2 receptor expression and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection depend on differentiation of human airway epithelia. J. Virol. 2005;79:14614–14621. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14614-14621.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Metwaly A.M., Lianlian Z., Luqi H., Deqiang D. Black ginseng and its saponins: Preparation, phytochemistry and pharmacological effects. Molecules. 2019;24:1856. doi: 10.3390/molecules24101856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y.-M., Ran X.-K., Riaz M., Yu M., Cai Q., Dou D.-Q., Metwaly A.M., Kang T.-G., Cai D.-C. Chemical Constituents of Stems and Leaves of Tagetespatula L. and Its Fingerprint. Molecules. 2019;24:3911. doi: 10.3390/molecules24213911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sperstad S.V., Haug T., Blencke H.-M., Styrvold O.B., Li C., Stensvåg K. Antimicrobial peptides from marine invertebrates: Challenges and perspectives in marine antimicrobial peptide discovery. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011;29:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Demerdash A., Metwaly A.M., Hassan A., El-Aziz A., Mohamed T., Elkaeed E.B., Eissa I.H., Arafa R.K., Stockand J.D. Comprehensive Virtual Screening of the Antiviral Potentialities of Marine Polycyclic Guanidine Alkaloids against SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19) Biomolecules. 2021;11:460. doi: 10.3390/biom11030460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Metwaly A.M., Wanas A.S., Radwan M.M., Ross S.A., ElSohly M.A. New α-Pyrone derivatives from the endophytic fungus Embellisia sp. Med. Chem. Res. 2017;26:1796–1800. doi: 10.1007/s00044-017-1889-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Metwaly A., Kadry H., El-Hela A., Elsalam A., Ross S. New antimalarial benzopyran derivatives from the endophytic fungus Alternaria phragmospora. Planta Med. 2014;80:PC11. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1382393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metwaly A. Comparative biological evaluation of four endophytic fungi isolated from nigella sativa seeds. Al-Azhar J. Pharm. Sci. 2019;59:123–136. doi: 10.21608/ajps.2019.64111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yassin A.M., El-Deeb N.M., Metwaly A.M., El Fawal G.F., Radwan M.M., Hafez E.E. Induction of apoptosis in human cancer cells through extrinsic and intrinsic pathways by Balanites aegyptiaca furostanol saponins and saponin-coated silvernanoparticles. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2017;182:1675–1693. doi: 10.1007/s12010-017-2426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharaf M.H., El-Sherbiny G.M., Moghannem S.A., Abdelmonem M., Elsehemy I.A., Metwaly A.M., Kalaba M.H. New combination approaches to combat methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Sci. Rep. 2021;11:1–16. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-82550-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Metwaly A.M., Ghoneim M.M., Musa A. Two new antileishmanial diketopiperazine alkaloids from the endophytic fungus Trichosporum sp. Derpharmachemica. 2015;7:322–327. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Metwaly A.M., Fronczek F.R., Ma G., Kadry H.A., Atef A., Mohammad A.-E.I., Cutler S.J., Ross S.A. Antileukemic α-pyrone derivatives from the endophytic fungus Alternaria phragmospora. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014;55:3478–3481. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.04.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Metwaly A.M., Kadry H.A., Atef A., Mohammad A.-E.I., Ma G., Cutler S.J., Ross S.A. Nigrosphaerin A a new isochromene derivative from the endophytic fungus Nigrospora sphaerica. Phytochem. Lett. 2014;7:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.phytol.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhanzhaxina A., Suleimen Y., Metwaly A.M., Eissa I.H., Elkaeed E.B., Suleimen R., Ishmuratova M., Akatan K., Luyten W. In Vitro and In Silico Cytotoxic and Antibacterial Activities of a Diterpene from Cousinia alata Schrenk. J. Chem. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/5542455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghoneim M.M., Afifi W.M., Ibrahim M., Elagawany M., Khayat M.T., Aboutaleb M.H., Metwaly A.M. Biological evaluation and molecular docking study of metabolites from Salvadora Persica L. Growing in Egypt. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2019;15:232. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hegazy M.M., Metwaly A.M., Mostafa A.E., Radwan M.M., Mehany A.B.M., Ahmed E., Enany S., Magdeldin S., Afifi W.M., ElSohly M.A. Biological and chemical evaluation of some African plants belonging to Kalanchoe species: Antitrypanosomal, cytotoxic, antitopoisomerase I activities and chemical profiling using ultra-performance liquid chromatography/quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometer. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2021;17:6. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orazbekov Y., Datkhayev U., Omyrzakov M., Metwaly A., Makhatov B., Jacob M., Ramazanova B., Sakipova Z., Azembayev A., Orazbekuly K. Antifungal prenylated isoflavonoids from Maclura aurantiaca. Planta Med. 2015;81:PE10. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1556218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dewick P.M. The Flavonoids: Advances in Research since 1980, Harborne, J.B., Ed. Springer US; Boston, MA, USA: 1988. Isoflavonoids; pp. 125–209. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arthan D., Svasti J., Kittakoop P., Pittayakhachonwut D., Tanticharoen M., Thebtaranonth Y. Antiviral isoflavonoid sulfate and steroidal glycosides from the fruits of Solanum torvum. Phytochemistry. 2002;59:459–463. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(01)00417-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okubo K., Kudou S., Uchida T., Yoshiki Y., Yoshikoshi M., Tonomura M. Food Phytochemicals for Cancer Prevention I. Volume 546. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC, USA: 1993. Soybean Saponin and Isoflavonoids; pp. 330–339. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horio Y., Sogabe R., Shichiri M., Ishida N., Morimoto R., Ohshima A., Isegawa Y. Induction of a 5-lipoxygenase product by daidzein is involved in the regulation of influenza virus replication. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2020;66:36–42. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.19-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tait S., Salvati A.L., Desideri N., Fiore L. Antiviral activity of substituted homoisoflavonoids on enteroviruses. Antivir. Res. 2006;72:252–255. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Desideri N., Olivieri S., Stein M., Sgro R., Orsi N., Conti C. Synthesis and anti-picornavirus activity of homo-isoflavonoids. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 1997;8:545–555. doi: 10.1177/095632029700800609. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lipinski C.A., Lombardo F., Dominy B.W., Feeney P.J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1997;23:3–25. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(96)00423-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.BIOVIA . Discovery Studio Visualizer. BIOVIA; San Diego, CA, USA: 2012. [(accessed on 22 March 2021)]. Available online: https://discover.3ds.com/discovery-studio-visualizer-download. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bank. [(accessed on 2 January 2021)];2020 Available online: https://www.rcsb.org/structure/6LZG.

- 41.Bank. [(accessed on 2 January 2020)];2020 Available online: https://www.rcsb.org/structure/6LU7.

- 42.Ibrahim M.K., Eissa I.H., Abdallah A.E., Metwaly A.M., Radwan M., ElSohly M. Design, synthesis, molecular modeling and anti-hyperglycemic evaluation of novel quinoxaline derivatives as potential PPARγ and SUR agonists. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2017;25:1496–1513. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2017.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.El-Helby A.G.A., Ayyad R.R., Sakr H.M., Abdelrahim A.S., El-Adl K., Sherbiny F.S., Eissa I.H., Khalifa M.M. Design, synthesis, molecular modeling and biological evaluation of novel 2, 3-dihydrophthalazine-1, 4-dione derivatives as potential anticonvulsant agents. J. Mol. Struct. 2017;1130:333–351. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2016.10.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ibrahim M.K., Eissa I.H., Alesawy M.S., Metwaly A.M., Radwan M.M., ElSohly M.A. Design, synthesis, molecular modeling and anti-hyperglycemic evaluation of quinazolin-4 (3H)-one derivatives as potential PPARγ and SUR agonists. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2017;25:4723–4744. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2017.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eissa I.H., Metwaly A.M., Belal A., Mehany A.B., Ayyad R.R., El-Adl K., Mahdy H.A., Taghour M.S., El-Gamal K.M., El-Sawah M.E. Discovery and antiproliferative evaluation of new quinoxalines as potential DNA intercalators and topoisomerase II inhibitors. Arch. Der Pharm. 2019;352:1900123. doi: 10.1002/ardp.201900123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.PerkinElmer . ChemBioDraw Ultra 14.0. PerkinElmer; Waltham, MA, USA: 2012. [(accessed on 2 May 2015)]. Available online: https://shopinformatics.perkinelmer.com/search. [Google Scholar]

- 47.El-Gamal K.M., El-Morsy A.M., Saad A.M., Eissa I.H., Alswah M. Synthesis, docking, QSAR, ADMET and antimicrobial evaluation of new quinoline-3-carbonitrile derivatives as potential DNA-gyrase inhibitors. J. Mol. Struct. 2018;1166:15–33. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2018.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.El-Zahabi M.A., Elbendary E.R., Bamanie F.H., Radwan M.F., Ghareib S.A., Eissa I.H. Design, synthesis, molecular modeling and anti-hyperglycemic evaluation of phthalimide-sulfonylurea hybrids as PPARγ and SUR agonists. Bioorganic Chem. 2019;91:103115. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xia X., Maliski E.G., Gallant P., Rogers D. Classification of kinase inhibitors using a Bayesian model. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:4463–4470. doi: 10.1021/jm0303195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.BIOVIA QSAR, ADMET and Predictive Toxicology. [(accessed on 15 May 2020)]; Available online: https://www.3dsbiovia.com/products/collaborative-science/biovia-discovery-studio/qsar-admet-and-predictive-toxicology.html.

- 51.Venkatapathy R., Wang N.C.Y., Martin T.M., Harten P.F., Young D. Structure–Activity Relationships for Carcinogenic Potential. Gen. Appl. Syst. Toxicol. 2009 doi: 10.1002/9780470744307.gat079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goodrnan G., Wilson R. Comparison of the dependence of the TD50 on maximum tolerated dose for mutagens and nonmutagens. Risk Anal. 1992;12:525–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1992.tb00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Council N.R. Issues in Risk Assessment. National Academies Press (US); Cambridge, MA, USA: 1993. Correlation Between Carcinogenic Potency and the Maximum Tolerated Dose: Implications for Risk Assessment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gonella Diaza R., Manganelli S., Esposito A., Roncaglioni A., Manganaro A., Benfenati E. Comparison of in silico tools for evaluating rat oral acute toxicity. Sar Qsar Environ. Res. 2015;26:1–27. doi: 10.1080/1062936X.2014.977819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pizzo F., Benfenati E. In Silico Methods for Predicting Drug Toxicity. Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 2016. In silico models for repeated-dose toxicity (RDT): Prediction of the no observed adverse effect level (NOAEL) and lowest observed adverse effect level (LOAEL) for drugs; pp. 163–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Venkatapathy R., Moudgal C.J., Bruce R.M. Assessment of the oral rat chronic lowest observed adverse effect level model in TOPKAT, a QSAR software package for toxicity prediction. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2004;44:1623–1629. doi: 10.1021/ci049903s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wilhelmus K.R. The Draize eye test. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2001;45:493–515. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6257(01)00211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.